1. Introduction

Digital Twins provide technicians and engineers with contextualized real-time data and allow them to interpret that information intuitively. As DTs are becoming more and more prevalent in the industry [

1], the adoption of mixed reality applications is inevitable since merging these new technologies through the creation of new processes, tools, and techniques will enhance biopharmaceutical production in the future [

2]. Mixed Reality is the blending of the physical and digital worlds to create new environments and visualizations where physical and digital objects co-exist and interact in real-time [

3]. Communications, exchanges between people and machines, and even between industrial products themselves, are made possible by digital technologies. The manufacturing of the future invests in cutting-edge technologies such as DT and MR in order to enhance its operations and the performance of its personnel [

2]. For an industrial partner, DT and MR have the potential to deliver novel preventative maintenance options. This paper is a preliminary contribution to the development of the solution. It is envisaged that this technology can help prevent unplanned downtime by troubleshooting issues before they are allowed to escalate, assist preventative maintenance provide users with a very real insight into the performance of the system and help plan for improvements in those systems and processes. One of the key advantages is that they make it possible for businesses to identify issues earlier and deal with them more proactively. Virtual models can be used to get a detailed understanding of a product’s usage patterns, points of degradation, workload capacity, and fault occurrence. Furthermore, by having a better understanding of the product’s features and failure mechanisms, component design can be improved.

2. Elastomer Change Out (ECO) - Application Case

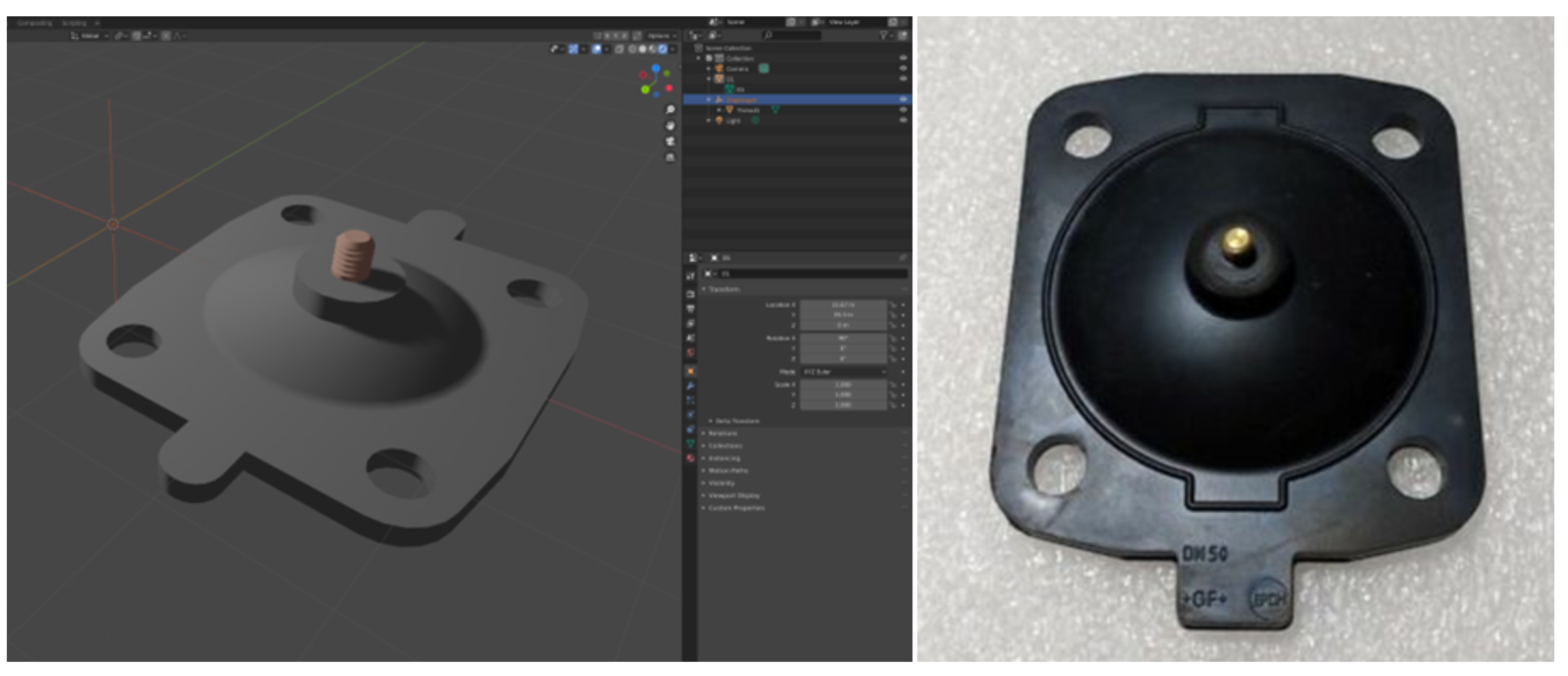

The problem context in question is the maintenance and replacement of elastomer diaphragms which are rubber-like materials that are useful as they are flexible, and elastic and can ensure tight seals between hard metal surfaces (See

Figure 1). Elastomers prevent leaks and separate fluids that should never come into contact. Over time, and with high exposure to harsh temperatures, chemicals and pressure cycles, these diaphragms are subjected to degradation, elastomers can become brittle and deformed and can ultimately fail. Elastomer Change-Outs (ECO) performed by service technicians is a set of processes to prolong the lifespan of diaphragms in diaphragm valves and gaskets in manufacturing/ manufacturing supply pipework. These crucial components need to be exchanged well before there is a risk of failure [

4], as the consequences could lead to contaminated products or a dangerous breach of a system’s health and safety requirements. Many Biopharma plants have large-scale installations of valves (5000+). Each one needs to be serviced, maintained and documented correctly to avoid problems. The cost of failure is high, but the cost of exchange is also high [

5]. It is estimated that 50% of maintenance activity is consumed by soft parts change-out [

6]. There is also plant downtime, therefore there is a clear need for cost-saving measures, where it has been identified that DT and MR technologies could be leveraged to address some of these challenges. The current accepted and common approach for elastomer change out is temporal-based (i.e. there is a fixed frequency – perhaps annually or biannually – for scheduled maintenance to replace the component). Although this scheduled approach is acceptable, it does not take into account the conditions the elastomer has been subjected to. For example, in conditions where the valve components have been lightly used, they may be exchanged even though continued use would be acceptable. Therefore, this could lead to unnecessary downtime of the biopharma plant, inferred costs and potentially reduced production. At the opposite end of the spectrum, severe or more frequent use could risk failure of the elastomer before its fixed time has been reached. This fixed frequency/temporal-based approach needs to be challenged to improve operational effectiveness (reduce ECO service costs/times, reduce operations downtime, reduce risk of failure, and reduce waste or resources such as the exchange of elastomers). It is proposed that predictive (condition-based) and preventative (time-based) maintenance task management, could reduce inefficiencies in current ECO service approaches. Through characterizing and modelling the elastomer degradation condition over time when exposed to various temperatures, chemicals, and pressure cycles, the elastomer can be analyzed to accurately predict its life cycle. This synthesized data can be streamed and presented through the immersive MRDT to assist technicians in intuitively visualising live operation information and making decisions in relation to maintenance activities. Additionally, the convergence of DT and MR technologies aims to demonstrate how predictive and preventative maintenance information services could be provided in a way which offers richer mobility, visualization and interactivity to service technicians. The increasing relevance of immersive technology bridges the gap between DT data and on-site maintenance by adding a data localization layer; generating the DT where the actual physical asset is located. Implementation of MR applications supports all the core aspects of Maintenance 4.0 [

7].

3. Digital Twins

In literature, DTs have varying definitions depending on levels of integration, their focused area and the technologies used [

8]. Despite this gradient of interpretation, it is unanimously agreed that DT technology is a key enabler for digital transformation [

9] and is positioned to enhance current operations in the industry. According to General Electric, “A Digital Twin is a digital model of an industrial asset—like a jet engine or a wind turbine. They are built by continuously collecting data off physical and virtual sensors on the asset and analyzing the data to gain unique insights about performance and operation that drive business value and outcomes.” [

10] The first DT in action was Apollo 13 despite the fact that it happened decades before the term “digital twin” was coined and widely accepted [

11]. A number of key components that qualify the lunar module as a DT are: must relate to the physical asset, have constant connectivity, adaptable to changes, can consist of multiple interacting models, and be responsive. The impact of using the simulator DT averted a disaster, saved lives, and now paves the way for modern DTs as we see them emerging today. The majority of contemporary digital twins involve a remote physical object that is linked to the digital model via an ongoing data stream. In reaction to changes in the real-world item, the computer models are updated using this link [

12]. In addition to this connectivity between the physical and the digital, is the integration of machine learning (ML) algorithms and artificial intelligence (AI) along with big data analytics that can be employed to enable forecasted models and predictive capabilities [

13].

3.1. Digital Model and Digital Shadows

According to Shao et al., the distinctions between a digital model (DM), digital shadow (DS), and digital twin depend on how much data is integrated between the digital and physical versions. In short, the majority of offline simulation models are categorized as digital models; simulation models that use near real-time sensor data as inputs are referred to as digital shadows; and simulation models that use near real-time sensor data as inputs and control the physical counterparts by updating control parameters are referred to as digital twins [

14]. Additionally, as further elaborated by Krtizinger et al., the state of an existing physical object is fed into the DS model in a one-way data flow. The digital object changes when the physical object changes, but not the other way around. In contrast, DTs have completely integrated data flows in both directions between physical and digital objects [

8]. Furthermore, they concluded that due to the variety of focused areas within different disciplines, the term Digital Twin is synonymously used with Digital Model and Digital Shadow. Due to the temporal evolution of the term ‘Digital Twin’ and its various interpretations that have been developed in recent years, and considering the proposed system’s lower levels of integration, liberty has been taken to adapt a category of the term DT for this application which is the basic and the more commonly known definition of “a realistic digital model of an object’s physical state, representing its interaction with the environment in the real world” [

10]. Particularly in the context of applications in the field of manufacturing technology, there is currently a lack of thorough understanding of the terms Digital Twin and Digital Shadow [

15].

4. The Internet of Things

Since the advent of this interconnectivity of sensor-enabled ‘things’, significant strides have been made in various areas in relation to speed and bandwidth, control systems, security, cloud services, and data visualizations in mobile and desktop applications. It certainly has transcended beyond the ‘hobbyist’ level to commercial and industrial domains. The industry equivalent IoT known as Industrial Internet-of-Things (IIoT) is currently paving the way to the more integrated framework of Industry 4.0 [

16] merging Operation Technology(OT) and information technology(IT). While facing many challenges in its implementation, particularly in manufacturing, reference designs and novel architectures are being used more frequently in various fields to instruct engineers on how their systems should interact and be structured [

16]. Technologies such as cloud and edge computing through enabling mobile networks such as 5G, reliability of data transfer and storage, further facilitate the digital transformation of numerous business companies and organizations [

17]. Intra-machine communications through secure and robust frameworks and protocols present greater opportunities through data analytics(DA) ML and AI for turning raw data into insightful information. PLCs in industrial process production and manufacturing have been the tried and tested, core component of operations, particularly alluding to ladder logic, structured text, function blocks, instruction lists and sequential function charts [

18]. With more and more IoT-enabling features being added to modern PLCs, real-time connectivity over the internet and advanced monitoring are becoming an integral part of process control and automated operations allowing manufacturers to standardize processes across plants and the ability to scale [

18]. Advancements in IIoT protocols such as MQTT(Message Queuing Telemetry Transport) [

19] and OPC-UA(Open Platform Communications Unified Architecture) [

20] are also bringing the industry closer to a more unified and highly-scalable infrastructure enabling digital twins of devices, processes, and plants to take production to the next level.

5. Extended Reality

Since the 1960s when the idea of a digital twin was first conceived, there has been interest in employing computer-mediated reality to enhance human perception [

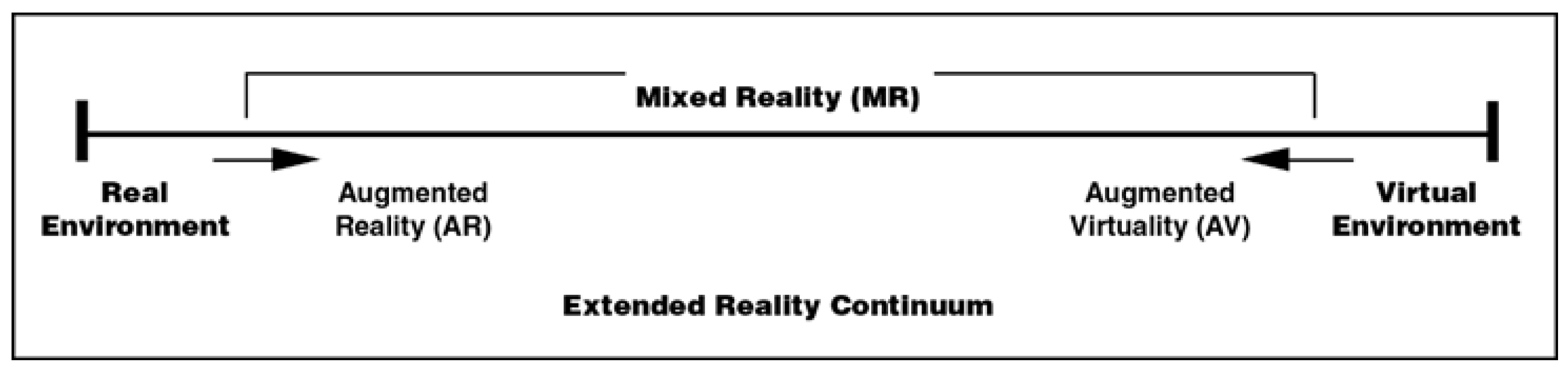

21]. The Extended Reality (XR), as it is becoming widely known, refers to the model proposed by Milgram and Kishino, which is depicted in

Figure 2 and describes a continuum and a gradual transition [

3].

Users can interact with the virtual objects as if they were actual objects, taking MR systems one step beyond AR. The virtual objects are not merely superimposed upon the real world. To experience MR, a headset with an integrated computer, translucent glass, and a sensor is required [

22]. However, the emerging Passthrough API of the Oculus headset enables MR development. Passthrough offers a real-time and perceptually pleasing 3D depiction of the outside world. Developers can incorporate the passthrough visualisation into their virtual experiences thanks to the Passthrough API [

23]. Numerous studies have demonstrated how XR technology can be used to enhance a range of manufacturing-related tasks at all stages, from design through operation and service [

7,

24,

25]. There is a five-step framework proposed by Gong et al. to develop XR applications which will promote adoption of this technology by ensuring proper user-centric design at the core of the development process [

26]. Due to the complex nature of manufacturing and process production, XR applications developed to date focused on supporting one manufacturing activity which highlighted mixed results with some performing worse than initially envisaged [

27,

28]. With various hardware platforms increasingly becoming more powerful and with each improvement addressing issues based on feedback from previous systems, more research opportunities are envisaged to be undertaken.

6. System Architecture and Framework

Various IoT architectures enable the transmission of sensor data to a user interface through various methods and communication protocols. This is dependent on each domain and the use cases define the rationale for a DT deployment [

29]. Regardless of this variety, the general framework is composed of three core elements: the physical component, the virtual component, and the connectivity between the two [

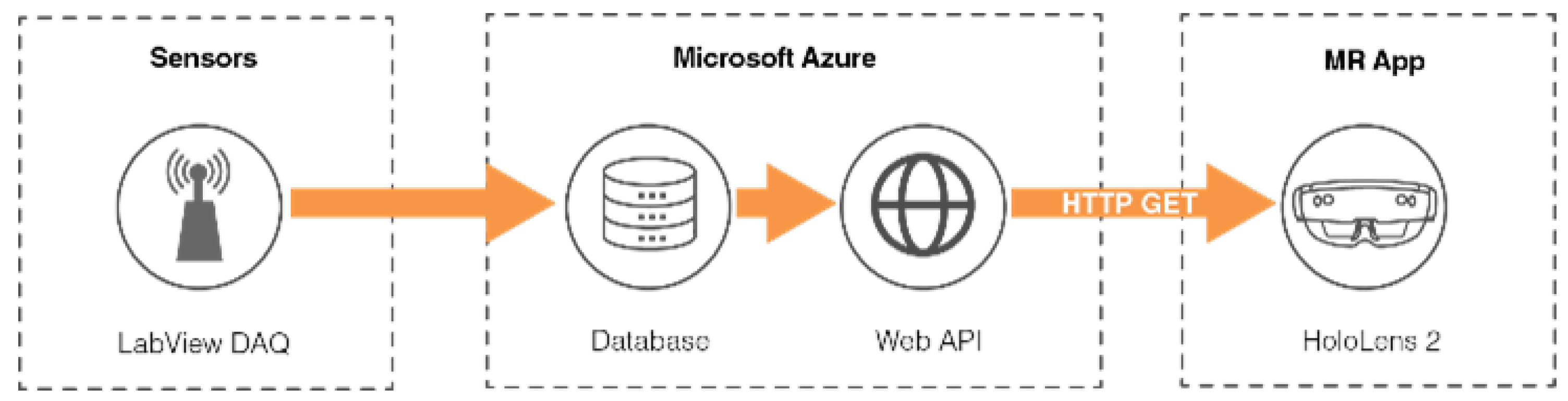

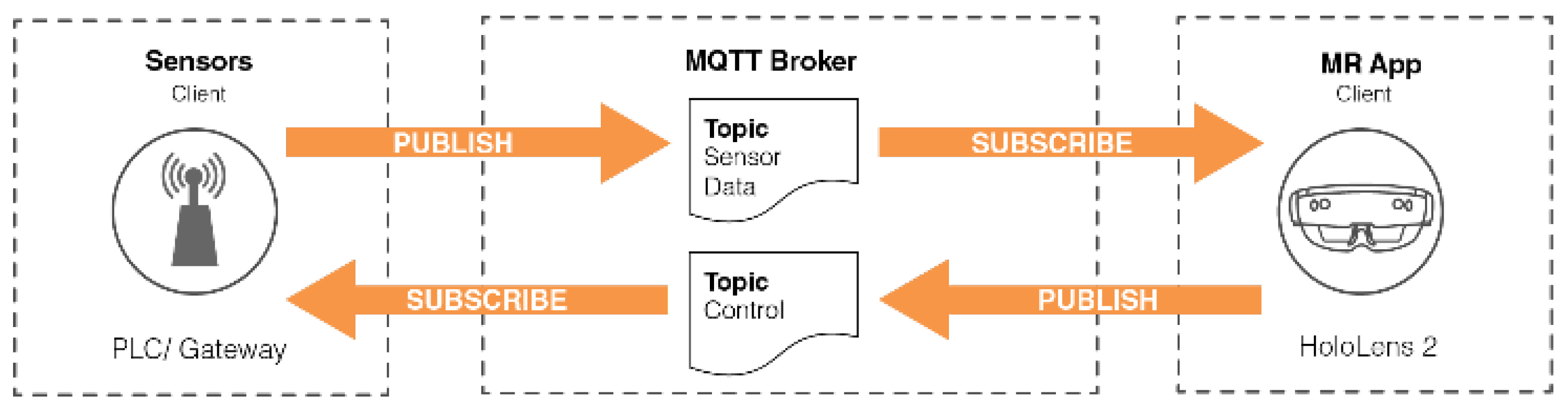

30]. This section outlines two dataflows used in this study. One uses HTTP web request and MQTT client/broker and publish/subscribe models. See

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

6.1. HTTP (Request/Response - REST API)

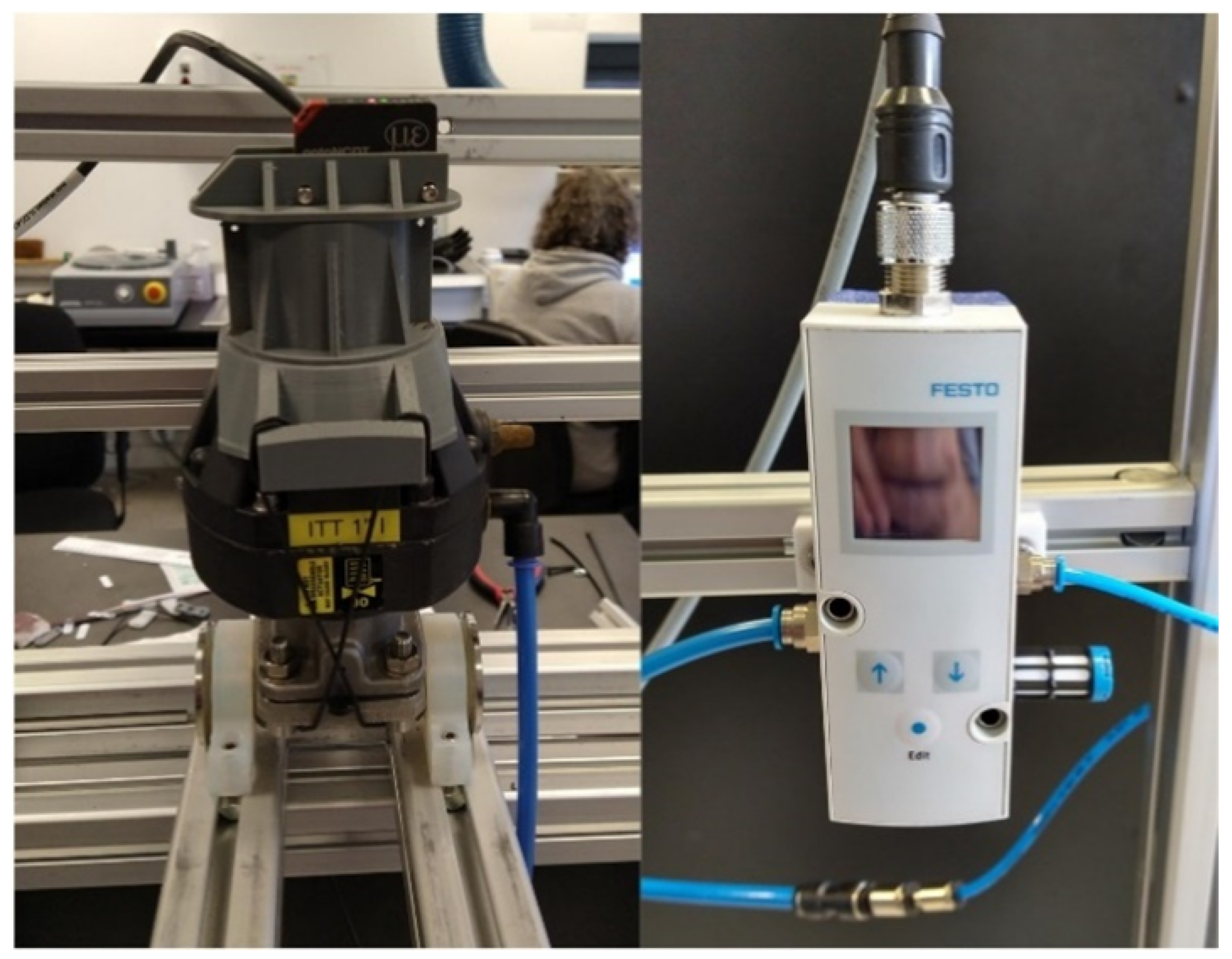

HTTP is a reliable request-response protocol in a client-server model that stands on top of a TCP/IP connection [

31]. Sensor data using LabView data acquisition (DAQ) [

32] measured and logged key parameters; temperature, pressure, and distance (See

Figure 5). These values are exported into a SQL database which is represented via REST API as a JSON endpoint taking the latest stored entry values. These values are parsed by the client application using HTTP GET web request which can be queried and displayed in the holographic interface. String values are parsed to enable data manipulation (i.e. integers to plot graphs, do basic calculations, etc.). The API endpoint can also be adjusted to take the latest hundred entries to plot a historical time-series graph. Other information that is available to be queried includes the asset ID, asset location, specifications, last service dates and technician notes all of which are presented in an intuitive holographic interface. Within the game engine Unity 3D [

33], the development platform used to build the application, methods to communicate with web servers are used in the scripting of the various game objects within the scene. Unity WebRequest handles the flow of HTTP communication with web servers and includes static utility functions that return instances configured for common cases such as GET, POST, PUT, and DELETE [

33].

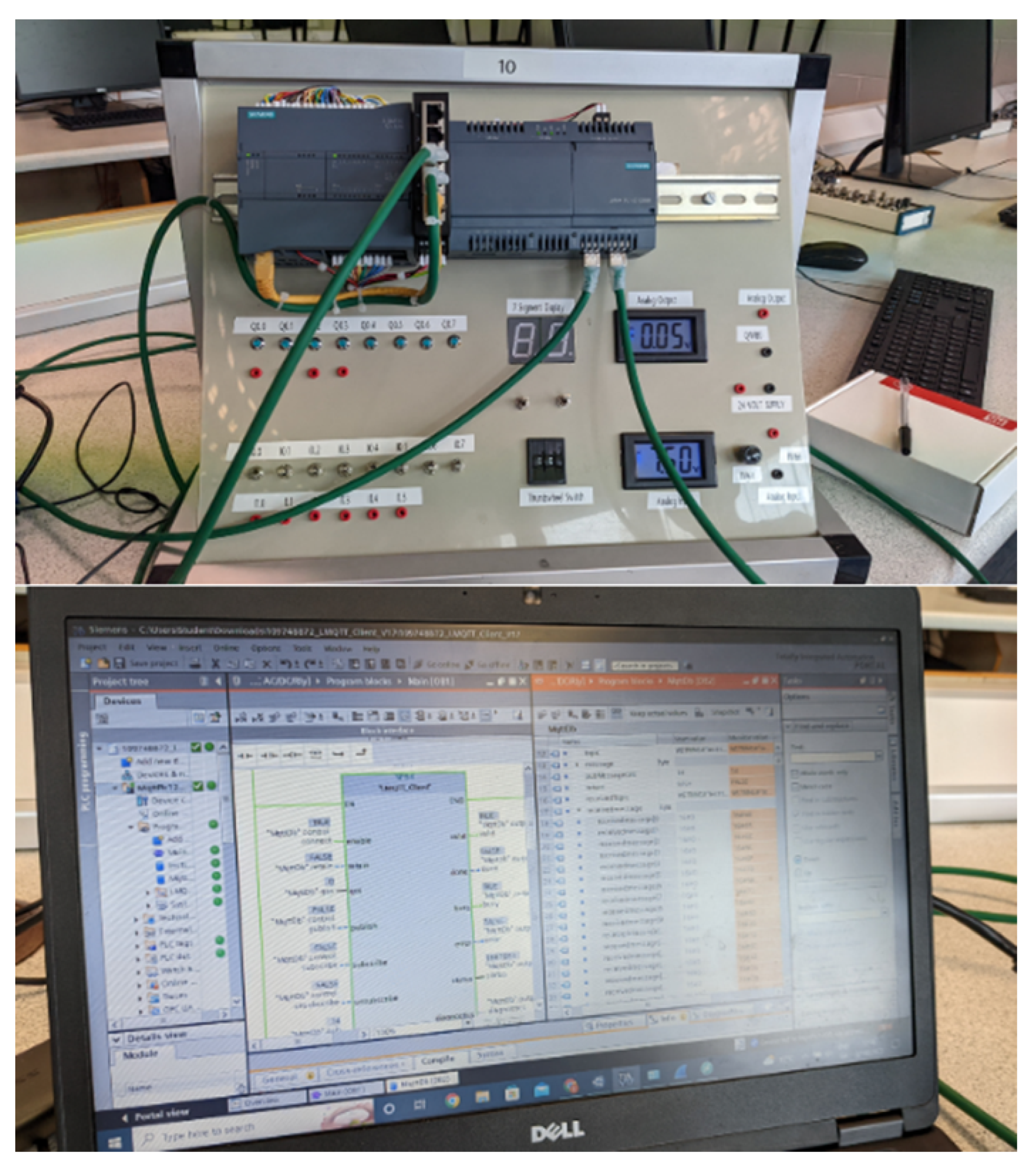

6.2. MQTT (Publish/Subscribe)

The lightweight IIoT communications protocol, MQTT was used in conjunction with a PLC (Siemens Simatic S7-1200 [

34]) and its corresponding gateway (Simatic IOT2000 [

34]) via 4G to enable data transfer to the MQTT broker (HiveMQ [

35]). To simulate real-time sensor readings, an analog sensor (potentiometer) is interfaced by the PLC which essentially enables telemetry readings (See

Figure 6). The secure MQTT-enabled PLC through the use of the protocol library (LMQTT) over TLS (MQTTs) was configured to achieve the publish/subscribe model with the external broker. Topics created allow various clients to publish data as well as subscribe to it, making for a direct interface with telemetry data. The sensor values transmitted are in string format which are then parsed on the client side to integer type for data manipulation. The payload in this particular case is a single stream to a topic. However, it must be noted that the data stream from sensor to visualization will require stringent security measures at each node to ensure the safe merging of OT and IT data. This is achieved by using certificate authentication with SSL protocol as well as an identity and password-enabled connection [

36]. An advantage of using MQTT over other protocols such as OPC-UA is the flexibility and unifying nature of the publish/subscribe architecture over the more convoluted client-server model of OPC-UA. This ‘single source of truth’ and this unified namespace structure with the MQTT broker at its core along with it being a lightweight protocol and ease of integration arguably tips the scale in favour of MQTT as the protocol of choice [

37]. On the client application side, an MQTT client, M2MQTT allows connection to any MQTT broker [

38]. The real-time string values are parsed into integers which are plotted on a dynamic time-series graph. The ability to publish messages from the MR app back to a separate topic in the MQTT broker can enable PLC control as a client subscribed to it, qualifying bi-directional communication between the physical and virtual.

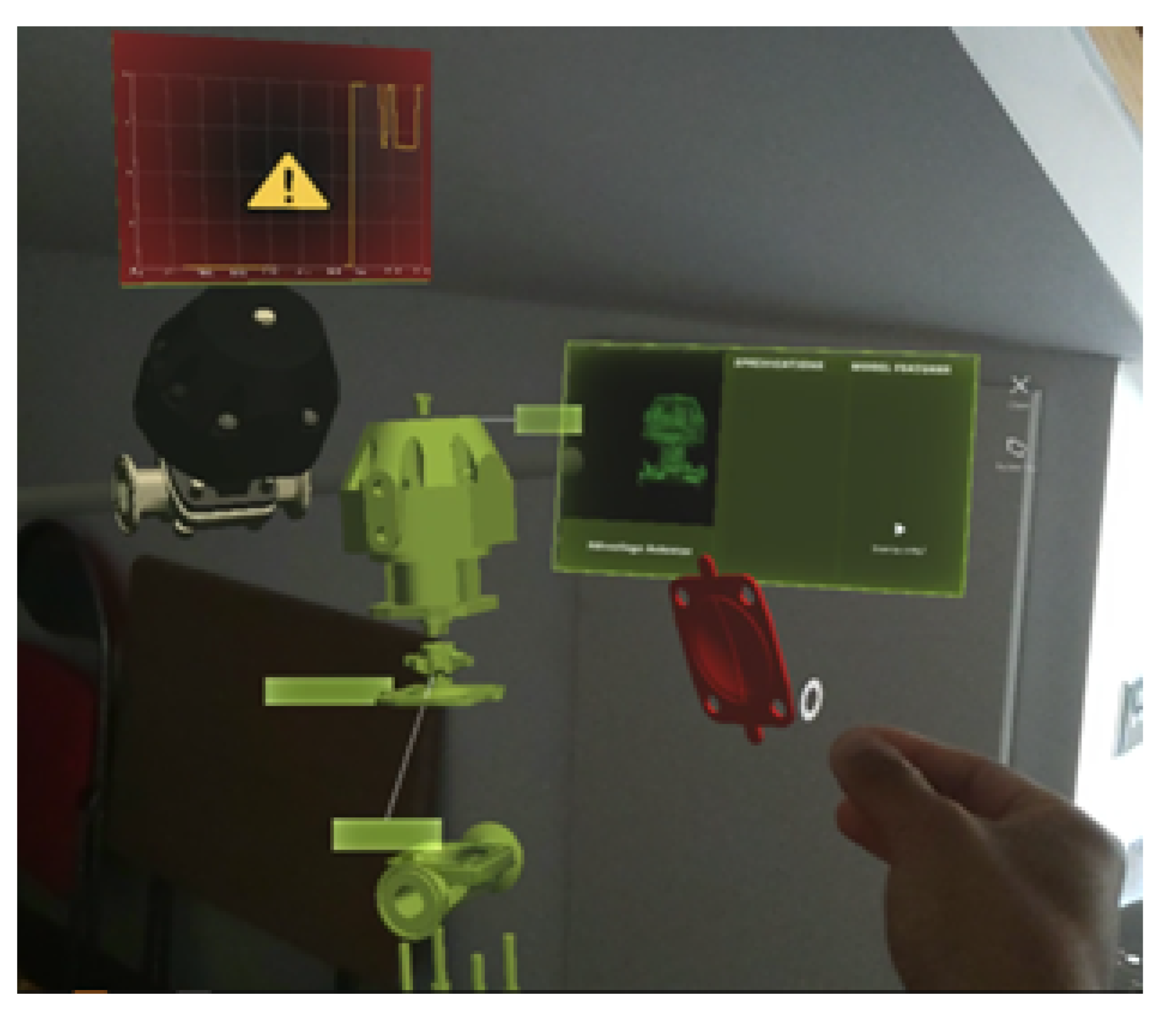

6.3. Mixed Reality Application Development

The MR application is developed using Unity 3D (version 2019.4.31f1) which is a flexible development platform that can use scripting to interact with various game objects within the scene environment. The design of which must be thoroughly considered when adding certain immersive features such as voiceovers, sound effects, visual animations, object manipulation, etc. For this use case, the user is presented with the virtual twin of the diaphragm actuator with all relevant information accessible by means of individual window panels which include texts, graphs and numerical values. The key component that needs to be replaced is the elastomer diaphragm which is enclosed within the metal casing. The virtual twin displays an exploded assembly of the valve actuator containing the elastomer diaphragm which is given interactable mixed-reality properties allowing the user to manipulate it. This was achieved using Microsoft’s Mixed Reality Toolkit (MRTK) [

39] which is a cross-platform toolkit that accelerates cross-platform MR app development for Virtual Reality and Augmented Reality applications. This toolkit allows for a faster and more efficient iterative design process of the “Design, Test, Polish, Repeat” pipeline that opens up a large amount of flexibility while keeping the base of the application solid and stable. This near or direct interaction with the virtual twin uses the HoloLens 2’s ability to support articulated hand-tracking input coupled with sufficient visual cues, allows for a user-intuitive experience. For far interactions, the hand ray enables for hovering and grabbing objects that are further away which allows the user to remain stationary. Traditionally, in the 2D abstract world, the UI button is used for triggering an event; however, with the more immersive, three-dimensional, mixed reality world, any interactable object can be used to trigger events. The menus that are called up have interactive elements (close buttons, follow buttons). Text-heavy panels such as the Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) document, have a scroll function and buttons to navigate within one window. Incorporating other formats such as audio and video to further supplement the information being presented. The font used is also high-resolution, legible and can be enlarged if needed. Other features include a 3D section view through use of transparent shaders for the assembly to allow users to inspect the interior along with corresponding visual effects or information to simulate the current state of the diaphragm. For example, enabling it to blink red when reaching a critical point, the data of which is derived from real-time data transmitted values (see

Figure 7). Various tooltips of the device component parts offered useful annotation. The digital assets, particularly the valve assembly 3D model are generated using SolidWorks [

40] for high-resolution, high-fidelity mesh that is then compressed (polygon size reduction) before importing it into the game engine. This is to alleviate the performance strain on the headset’s processor. The intended user experience design was centred around how to best assist the user in carrying out the ECO service. Features include various embedded video tutorials, specification documents, graphs and a register form for logging notes. The idea being that all the necessary information can be made available as immersive, holographic elements.

7. Results and Discussion

The MRDT application demonstrator developed for the use case of maintenance and replacement of elastomer diaphragms is presented in this paper. This section outlines some key observations on using two IoT protocols for the data stream. The publish/subscribe model enables visibility of real-time telemetry which can be used to plot graphical charts and other visualization forms such as color gradient shaders on a game object material. This dynamic data stream is useful in seeing the state of the critical part and the parameters monitored. MQTT is lightweight with minimal payload and latency making it an ideal protocol to use due to its event-driven nature which also qualifies the virtual twin as a DS as it is fed real-time data representative of its physical counterpart. The ability to publish messages back to the broker and consequently back to the PLC enables control and therefore a legitimate bi-directional communication which qualifies this as a DT as it can affect the process and thus affect the state of the device. The noticeable impact on performance, however, is on the graphical representation of the plotted values, particularly on a dynamic chart which affected the frame rates. There were some noticeable frame drops from 60fps to around 40fps. There are two primary processors responsible for the work to render the MR scene: the CPU and GPU. Upon testing the areas where the application is computationally intensive, the CPU thread, responsible for the app logic and processing input is observed to have some impact on the drop of frame rates. The script enabling the MQTT interface to the broker (M2MQTT) [

38] is constantly running in the background which contributes to performance bottlenecks. The graphical resources on the HoloLens 2 are significantly more limited than desktop PCs and therefore, efficient resource allocation and management is key to designing MR applications.

The use of web request (HTTP) in this application is more performance-friendly due to the single instance per web request to the server, This seems to be ideal for displaying unique information through parsing a JSON payload from a REST API endpoint. All relevant information can be queried and displayed which is unique to a specific valve component for a fuller, more detailed overview such as part dimensions, material properties, model features, last maintenance work carried out, etc. The latest entry stored in the database still represents the most up-to-date state of the physical component through sensor data transmission. However, this means making a request manually by activating a button for a response. A graphical static chart can be plotted taking the last hundred entries to view a historical profile for example. It is evident from this that a combination of the two can work quite effectively as the user can benefit from both dynamic and static data transmissions.

7.1. Benefits and Limitations

Although the adoption of mixed reality technologies is still at its infancy in its application in Industry 4.0 [

41], there is certainly a place where it could overhaul many existing systems to enable them to be more integrated than ever before. The immersive heads-up display (HUD) significantly alters the user experience, especially with contextual data overlay transmitted near real-time. Replacing the conventional methods and maintenance operations such as paper-based workflows is hypothesized to increase the efficiency as the application interfaces directly to cloud services and databases. There are massive potential opportunities for utilizing this technology, particularly with monitoring assets on the factory floor. Being able to see the current state of the asset, coupled with values from forecasting models is a powerful feature that improves the visibility of meaningful data. However, initial training may be required on hand gestures, hologram interactions, and familiarizing the technician with the headset. As digital information gets closer and closer to physical systems, there may potentially be an enhancement in control, analytics, and streamlined decision-making. This result can only be accurately measured by fully implementing the technology which is quantified by tangible performance metrics such as productivity, cost reduction, process efficiency, accuracy, and streamlined workflows. Regulations and standards surrounding this will surely follow as the technology adoption is gaining momentum.

This MRDT application demonstrated on the prototype level, that a full data stream from sensor to visualization can be achieved using typical IoT protocols to present sensor data. However, there were some issues encountered. On the technical side, the interoperability of various devices and communication protocols used is dependent on connectivity which is influenced by the environment on the sensor level. Low-latency and low-bandwidth network environments will mean implementing the appropriate IoT communication protocol for telemetry data to be effective and meaningful. Due to the higher resolution monitoring requirement of the diaphragm component, the sensors themselves and the sensor network will need to be installed in an unintrusive way of the process which consequently will require extra maintenance; ensuring that the monitoring equipment layer is maintained along with the process equipment for the digital twin representation to remain accurate. On the user experience aspect, although the effect of motion sickness pertaining to the use of the HoloLens is minimal [

42], there is a need for prior familiarization with the object interaction. The holographic buttons, while clearly labelled and the UI is generally intuitive with visual and audio feedback, interaction proves difficult and frustrating due to the mismatch in visual depth planes which impacts the interactivity of the holographic elements. Significant familiarization of the headset will improve hand-eye coordination as well as muscle memory over time. A number of first-time HoloLens 2 users noticeably struggled with object interactions compared to some who had prior experience with the headset. Proper usability testing will mean a thorough gathering of requirements to design the custom application to service engineers of the biopharma plant and to systematically grade it. However, this was not the primary focus of this initial exploration. There is also a noticeable discomfort experienced from the device overheating when wearing the HoloLens 2 for extended periods of time as similarly noted in other papers [

43,

44]. A further refinement of the whole UI will need to be revised and fully researched under UX design methodologies which will ultimately be an ad-hoc design to suit the process line environment which could entail tight spaces where reaching out to interact with holograms will not be suitable for example. Using Unity 3D as the game engine of choice for its flexible object-oriented programming (C#) allows for essentially any game object to become a trigger and executor of any function. However, careful attention will need to be paid to every 3D model brought into the scene environment. Due to the limited graphical and computational capabilities of the HoloLens 2, each polygon and face count matters for efficient and smooth runtimes. The number of elements available at any given time affects the performance (less than 60 frames per second) and can result in an uncomfortable experience. The models used were further compressed and converted to FBX files to maintain uniform fidelity across the environment scene.

8. Conclusion and Future Work

The project’s objective was to implement immersive, MR technologies for consuming digital twin data. The physical rig of the diaphragm actuator kitted with sensors provided key parameters represented in its digital twin. Using the HoloLens 2 as a potentially considered on-site technician’s tool and its ‘paper-less’ approach in conducting maintenance operations (e.g. ECO service) is envisaged to have significant workflow improvements over conventional methods. Through this preliminary work, we demonstrated the utility of this MR application and its potential role in the biopharma production context which naturally extends to other branches of manufacturing and other production and process sectors.

The user-centric design approach is paramount for this technology to be widely adopted. With regards to future work and development, some notable features identified would further expand the information display for the on-site technician which include:

Register inputs - technicians on-site take records of various changes via a paper-based form and later log back into the database.

Full onboarding system - to thoroughly guide the technician with regards to UI navigation as well as technical operation of the service.

Forecasted model - inputs can feed into the DT and can generate predicted outputs in conjunction with the current data with a particular focus on the rate of degradation of the diaphragm.

Visual markers - each physical system component on-site should be able to be detected by the MR app either via a visual marker (e.g. QR code) or through advanced computer vision to trigger corresponding augmented reality digital assets.

Location mapping and tracking - A pathfinding algorithm will require extensive programming and tailored unique to a specific plant/floor layout.

Full usability study - it is acknowledged that there are onboarding issues with regard to interacting with holograms (i.e. specific hand gestures, etc.) as well as the use of unconventional user interface that will need to be thoroughly designed and addressed before it can be effectively used in any plant. A proper detailed human survey with technicians on the floor will yield valuable insight into the potential applicability of immersive visualizations through MRDT technology.

Upon developing the overall system architecture, accounting for the resources, managing data streams and employing cloud computing services, it is concluded that the application can be potentially scaled up. The development process and workflow demanded the researchers and developers to explore deeper into what is required in a mixed reality application and a better understanding of the overall integrated system to achieve a seamless data stream communication. It must be noted, however, that no substantial research has been done on any significant scale on usability difficulties in the context of mixed reality within the biopharma sector. Additionally, MR applications such as one developed here might be a useful tool for assessing immersive analytics more broadly.

Author Contributions

The work presented in this article is the result of a collaboration of all authors. Conceptualisation, AdJ and KOM; methodology, AdJ; software, AdJ; investigation, AdJ and KOM; resources, RB, RW and EG; writing—original draft preparation, AdJ; writing—review and editing, KOM; visualization, AdJ; project administration, KOM; funding acquisition, KOM All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the CONFIRM Centre for Smart Manufacturing under the Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) Research Centers Program Grant 16/RC/3918 and Enterprise Ireland’s Capital Call Funding program. [CE-2019-0050] in part funding the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of our industry collaborator, SCRI-IS Technologies Ltd.

References

- Park, K.T.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.J.; Noh, S.D. Digital twin-based cyber physical production system architectural framework for personalized production. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2020, 106, 1787–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabah, S.; Assila, A.; Khouri, E.; Maier, F.; Ababsa, F.; Maier, P.; Mérienne, F. Towards improving the future of manufacturing through digital twin and augmented reality technologies. Procedia Manufacturing 2018, 17, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milgram, P.; Kishino, F. A taxonomy of mixed reality visual displays. IEICE TRANSACTIONS on Information and Systems 1994, 77, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, G.; Mulryan, G.; Liggan, P. Lean maintenance–A risk-based approach. Pharmaceutical Engineering 2010, 30, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Maintaining Hygienic Diaphragm Valves.

- Jones, S. The Future of Valves and Diaphragms Supply. BioPharm international 2013, 26, 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Nee, A.Y.C.; Ong, S.K.; Chryssolouris, G.; Mourtzis, D. Augmented reality applications in design and manufacturing. CIRP Annals 2012, 61, 657–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritzinger, W.; Karner, M.; Traar, G.; Henjes, J.; Sihn, W. Digital Twin in manufacturing: A categorical literature review and classification. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, D.P.F.; Vakilzadian, H.; Hou, W. Intelligent Manufacturing with Digital Twin. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Electro Information Technology (EIT); 2021; pp. 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digital Transformation of Business Models - ProQuest.

- Ferguson, S. Apollo 13: The First Digital Twin, 2020.

- Fuller, A.; Fan, Z.; Day, C.; Barlow, C. Digital Twin: Enabling Technologies, Challenges and Open Research. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 108952–108971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, M.M.; Shah, S.A.; Shukla, D.; Bentafat, E.; Bakiras, S. The Role of AI, Machine Learning, and Big Data in Digital Twinning: A Systematic Literature Review, Challenges, and Opportunities. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 32030–32052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G.; Jain, S.; Laroque, C.; Lee, L.H.; Lendermann, P.; Rose, O. Digital Twin for Smart Manufacturing: The Simulation Aspect. In Proceedings of the 2019 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC); 2019; pp. 2085–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergs, T.; Gierlings, S.; Auerbach, T.; Klink, A.; Schraknepper, D.; Augspurger, T. The Concept of Digital Twin and Digital Shadow in Manufacturing. Procedia CIRP 2021, 101, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, E.Y.; Antonino, P.O.; Schnicke, F.; Capilla, R.; Kuhn, T.; Liggesmeyer, P. Industry 4.0 reference architectures: State of the art and future trends. Computers & Industrial Engineering 2021, 156, 107241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM. IBM 5G and Edge Computing, 2020.

- Jones, C.T. Programmable Logic Controllers: The Complete Guide to the Technology; Brilliant-Training, 1998. Google-Books-ID: AuMzoz90j10C.

- December 9, M.Y.U.; May 11, .|.P.; 2017. Getting to know MQTT.

- Almeida, C. What is OPC?

- Sutherland, I.E. A head-mounted three dimensional display. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the December 9-11, 1968, fall joint computer conference, part I, 1968, pp. 757–764.

- Mourtzis, D.; Angelopoulos, J.; Panopoulos, N. Operator 5.0: A Survey on Enabling Technologies and a Framework for Digital Manufacturing Based on Extended Reality. Journal of Machine Engineering 2022, 22, 43–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passthrough API Overview | Oculus Developers.

- Phoon, S.Y.; Yap, H.J.; Taha, Z.; Pai, Y.S. Interactive solution approach for loop layout problem using virtual reality technology. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2017, 89, 2375–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, C.; Xu, X. Visualisation of the Digital Twin data in manufacturing by using Augmented Reality. Procedia CIRP 2019, 81, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Fast-Berglund. ; Johansson, B. A Framework for Extended Reality System Development in Manufacturing. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 24796–24813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, G.; Patron, C. Integrating Augmented Reality in the Assembly Domain - Fundamentals, Benefits and Applications. CIRP Annals 2003, 52, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyrou, O.; Hurst, W.; Verdouw, C. Virtual Reality-Based Digital Twins: A Case Study on Pharmaceutical Cannabis. Big Data and Cognitive Computing 2023, 7, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirk, D.; Lanni, J.; Chauhan, N. Digital Twins: Details Of Implementation: Part 2. ASHRAE Journal 2020, 62, 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Campos-Ferreira, A.E.; Lozoya-Santos, J.d.J.; Vargas-Martínez, A.; Mendoza, R.; Morales-Menéndez, R. Digital twin applications: A review. Mem. Del Congr. Nac. Control Autom 2019, 2, 606–611. [Google Scholar]

- An overview of HTTP - HTTP | MDN.

- What is Swagger.

- Technologies, U. Unity Real-Time Development Platform | 3D, 2D VR & AR Engine.

- SIMATIC S7-1200 | SIMATIC Controllers | Siemens Global.

- The Free Public MQTT Broker by HiveMQ - Check out our MQTT Demo.

- IBM Documentation, 2022.

- Manditereza, K. The Key Differences Between OPC UA And MQTT Sparkplug.

- M2Mqtt & GnatMQ.

- polar kev. MRTK2-Unity Developer Documentation - MRTK 2.

- 3D CAD Design Software | SOLIDWORKS.

- Mourtzis, D.; Angelopoulos, J.; Panopoulos, N. Challenges and Opportunities for Integrating Augmented Reality and Computational Fluid Dynamics Modeling under the Framework of Industry 4.0. Procedia CIRP 2022, 106, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vovk, A.; Wild, F.; Guest, W.; Kuula, T. Simulator Sickness in Augmented Reality Training Using the Microsoft HoloLens. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, New York, NY, USA, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, V.; Moroz, O.; Ding, A.Y. The Virtual Factory: Hologram-Enabled Control and Monitoring of Industrial IoT Devices. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Virtual Reality (AIVR); 2018; pp. 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Bonete, M.J.; Jensen, M.; Katona, G. A practical guide to developing virtual and augmented reality exercises for teaching structural biology. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education 2019, 47, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).