Submitted:

24 February 2025

Posted:

25 February 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

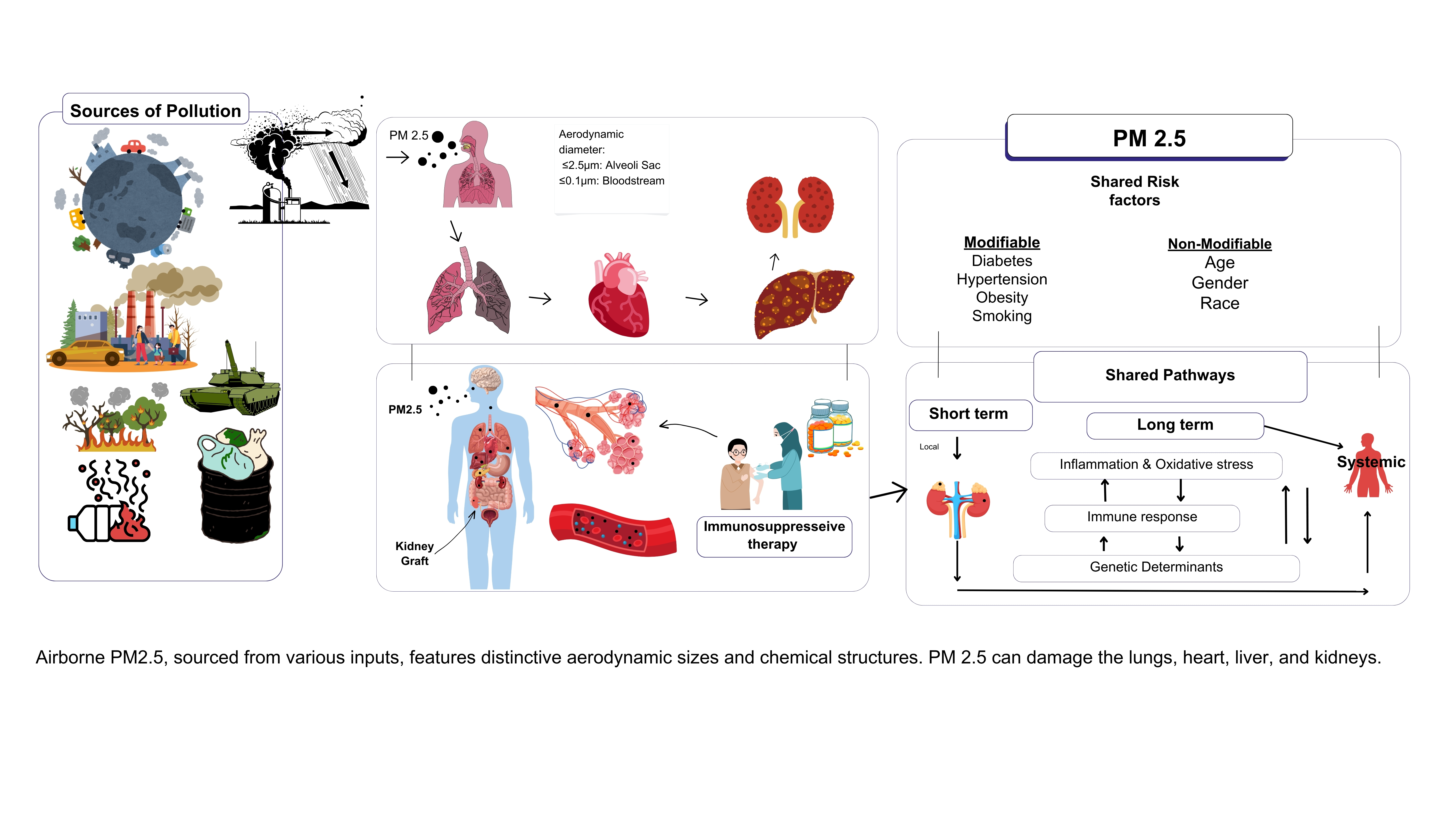

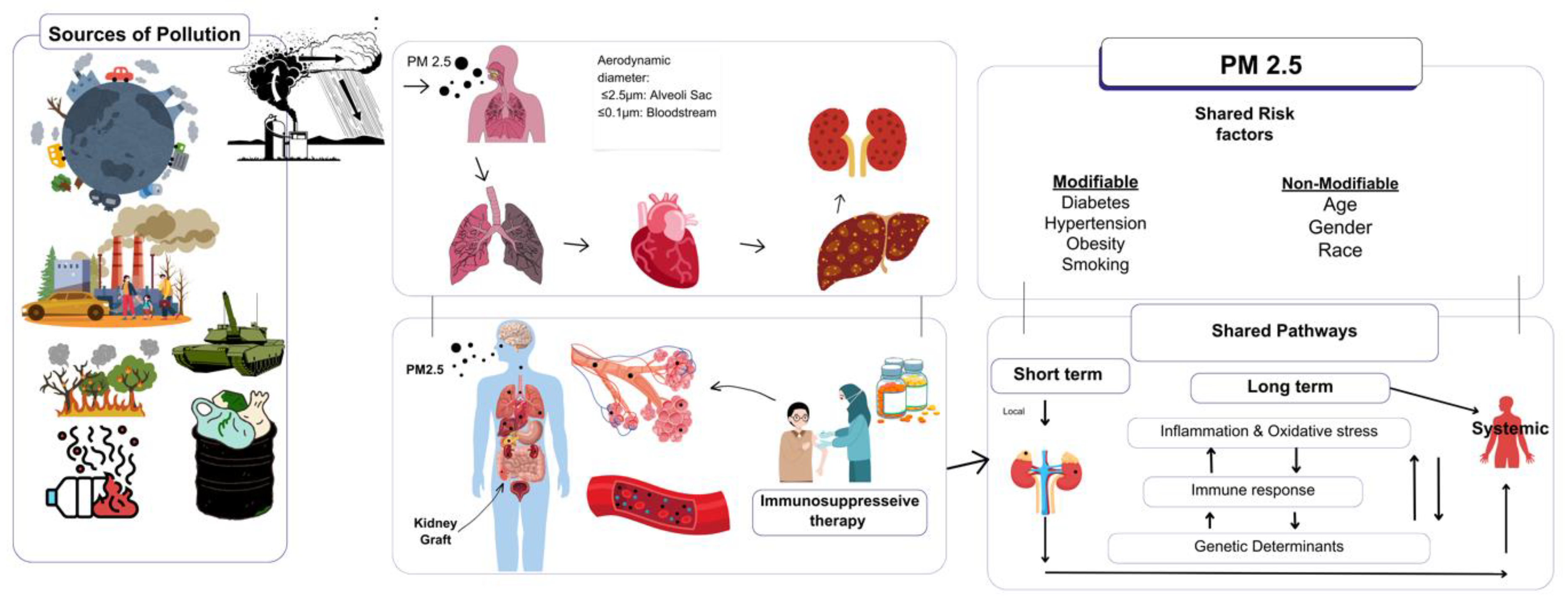

1. (PM2.5): A Critical Health Threat

2. PM2.5 and Immune Modulation in Transplant Recipients

2.1. Organ-Specific Effects of PM2.5 on Transplant Recipients

2.1.1. Respiratory Complications in Transplant Recipients

2.1.2. Cardiovascular Complications in Transplant Recipients

2.1.3. Hepatic Complications in Transplant Recipients

2.1.4. Renal Complications in Transplant Recipients

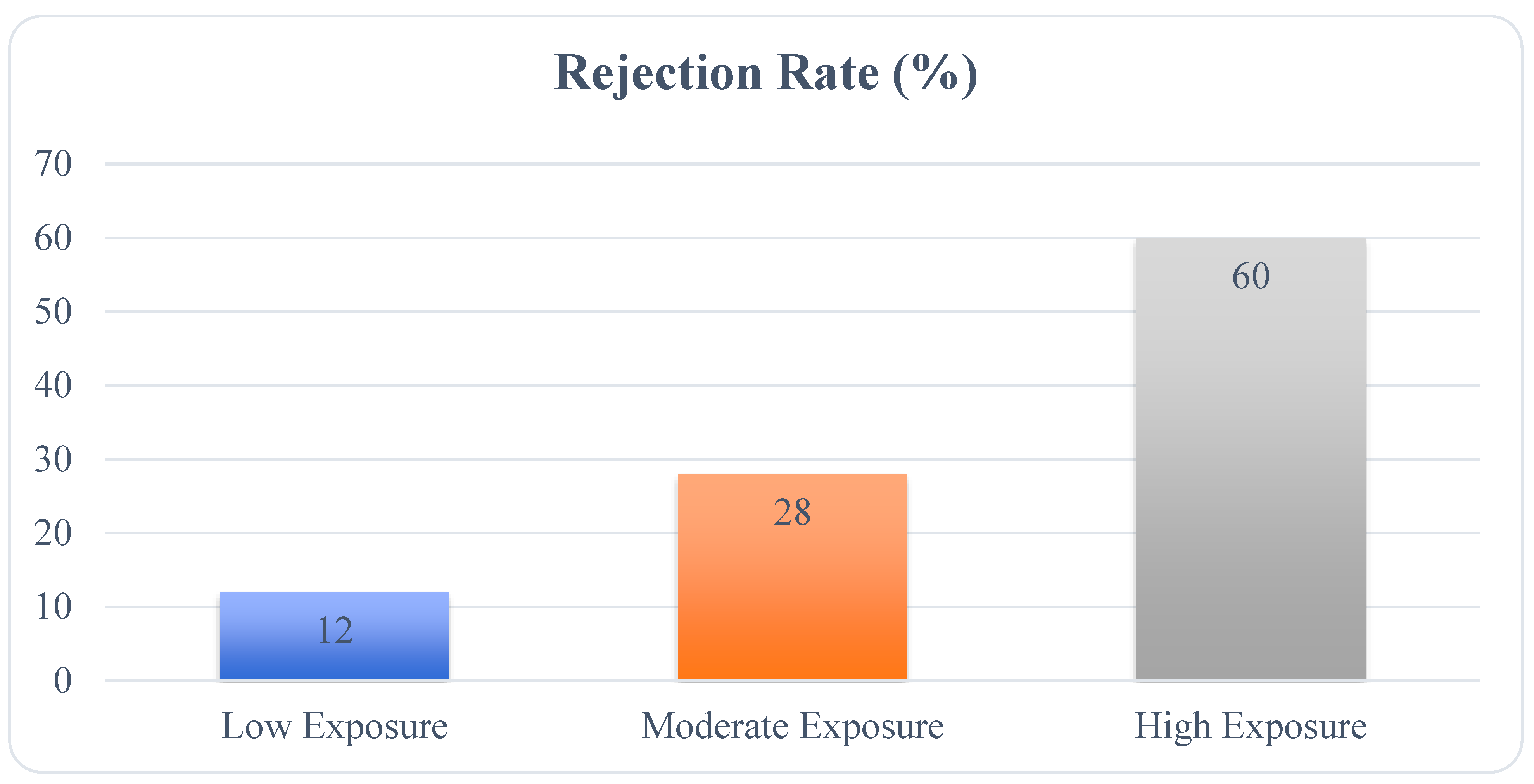

2.1.5. Long-Term Graft Survival and Environmental Exposures

2.1.6. Shared Pathophysiological Effects Across Organs

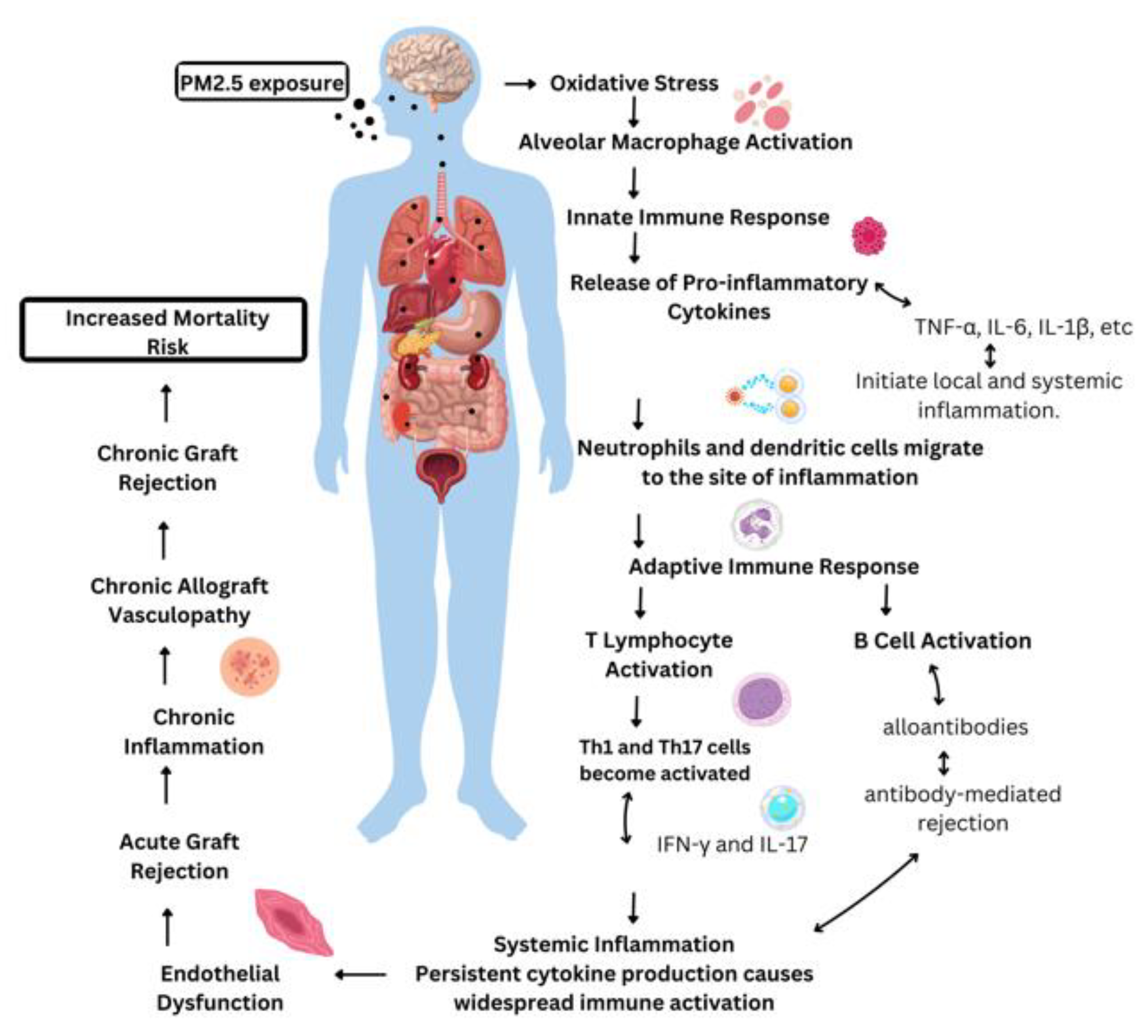

3. The impact of PM2.5 on transplant immunity

3.1. Innate Immune System and PM2.5 in Transplantation

3.1.1. Alloantigen Recognition and Immune Activation

3.1.2. Cytokine Storm and Inflammation

3.1.3. T-Cell Activation and Graft Rejection

3.2. Adaptive Immune System and PM2.5 in Transplantation

3.2.1. Macrophage Activation and Tissue Damage

3.2.2. Dendritic Cell Activation and Antigen Presentation

3.2.3. Regulatory T-Cell Dysfunction

4. PM2.5 and Chronic Inflammatory Processes in Transplantation

4.1. Oxidative Stress and Endothelial Dysfunction

4.2. Fibrosis and Chronic Graft Dysfunction

5. Clinical Implications and Recommendations

6. Conclusion

Authors Contribution

Acknowledgment

Declaration

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

| PM2.5 | Particulate Matter 2.5 |

| O₃ | Ozone |

| CO | Carbon monoxide |

| SO₂ | Sulfur oxides |

| NO₂ | Nitrogen oxides |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| CAV | Cardiac allograft vasculopathy |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| TLRs | Toll-like receptors |

| PAMPs | Pathogen-associated molecular patterns |

| DAMPs | Damage-associated molecular patterns |

| APCs | Antigen-presenting cells |

| CTLs | Cytotoxic T lymphocytes |

References

- Baklanov, A.; Molina, L.T.; Gauss, M. Megacities, air quality and climate. Atmospheric Environment 2016, 126, 235–249. [Google Scholar]

- Supphapipat, K.; Leurcharusmee, P.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. Impact of air pollution on postoperative outcomes following organ transplantation: Evidence from clinical investigations. Clinical Transplantation 2024, 38, e15180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dehom, S.; Knutsen, S.; Shavlik, D.; Bahjri, K.; Ali, H.; Pompe, L.; Spencer-Hwang, R. Long-term exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2. 5) and cardiovascular disease mortality among renal transplant recipients. OBM Transplantation 2019, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Perico, N.; Casiraghi, F.; Cortinovis, M.; Remuzzi, G. A Modern View of Transplant Immunology and Immunosuppression. In Contemporary Lung Transplantation; Springer: 2024; pp. 81-110.

- Xu, J.; Hu, W.; Liang, D.; Gao, P. Photochemical impacts on the toxicity of PM2.5. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology 2022, 52, 130–156. [Google Scholar]

- Thangavel, P.; Park, D.; Lee, Y.-C. Recent insights into particulate matter (PM2. 5)-mediated toxicity in humans: an overview. International journal of environmental research and public health 2022, 19, 7511. [Google Scholar]

- Nozza, E.; Valentini, S.; Melzi, G.; Vecchi, R.; Corsini, E. Advances on the immunotoxicity of outdoor particulate matter: A focus on physical and chemical properties and respiratory defence mechanisms. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 780, 146391. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, X.; Zhong, J.; Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S. Effect of particulate matter air pollution on cardiovascular oxidative stress pathways. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2018, 28, 797–818. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, F.J.; Fussell, J.C. Role of oxidative stress in cardiovascular disease outcomes following exposure to ambient air pollution. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2017, 110, 345–367. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Hu, B.; Liu, Y.; Xu, J.; Yang, G.; Xu, D.; Chen, C. Beyond PM2. 5: The role of ultrafine particles on adverse health effects of air pollution. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects 2016, 1860, 2844–2855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Garcidueñas, L.; Hernández-Luna, J.; Aiello-Mora, M.; Brito-Aguilar, R.; Evelson, P.A.; Villarreal-Ríos, R.; Torres-Jardón, R.; Ayala, A.; Mukherjee, P.S. APOE peripheral and brain impact: APOE4 carriers accelerate their Alzheimer continuum and have a high risk of suicide in PM2. 5 polluted cities. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 927. [Google Scholar]

- Gangwar, R.S.; Bevan, G.H.; Palanivel, R.; Das, L.; Rajagopalan, S. Oxidative stress pathways of air pollution mediated toxicity: Recent insights. Redox biology 2020, 34, 101545. [Google Scholar]

- Dhir, A.; Suphathamwit, A. Transplant patients. In Anesthesia and Perioperative Care of the High-Risk Patient, Third Edition; Cambridge University Press: 2014; pp. 444-461.

- Perico, N.; Casiraghi, F.; Cortinovis, M.; Remuzzi, G. A Modern View of Transplant Immunology and Immunosuppression. In Contemporary Lung Transplantation; Springer: 2024; pp. 1-30.

- Arias-Pérez, R.D.; Taborda, N.A.; Gómez, D.M.; Narvaez, J.F.; Porras, J.; Hernandez, J.C. Inflammatory effects of particulate matter air pollution. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2020, 27, 42390–42404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hill, G.R.; Betts, B.C.; Tkachev, V.; Kean, L.S.; Blazar, B.R. Current concepts and advances in graft-versus-host disease immunology. Annual review of immunology 2021, 39, 19–49. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Jones, M.R.; Ahn, J.B.; Garonzik-Wang, J.M.; Segev, D.L.; McAdams-DeMarco, M. Ambient air pollution and posttransplant outcomes among kidney transplant recipients. American Journal of Transplantation 2021, 21, 3333–3345. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Chiu, Y.-F.; Kao, C.-C.; Chuang, C.-N.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lai, C.-H.; Kuo, M.-L. Fine particulate matter manipulates immune response to exacerbate microbial pathogenesis in the respiratory tract. European Respiratory Review 2024, 33. [Google Scholar]

- Zaręba, Ł.; Piszczatowska, K.; Dżaman, K.; Soroczynska, K.; Motamedi, P.; Szczepański, M.J.; Ludwig, N. The relationship between fine particle matter (PM2. 5) exposure and upper respiratory tract diseases. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2024, 14, 98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Elalouf, A.; Yaniv-Rosenfeld, A.; Maoz, H. Immune response against bacterial infection in organ transplant recipients. Transplant Immunology 2024, 102102. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, U.D.; Preiksaitis, J.K.; Practice, A.I.D.C.o. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders, Epstein-Barr virus infection, and disease in solid organ transplantation: Guidelines from the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clinical transplantation 2019, 33, e13652. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, E.A. Autoimmune diseases and their environmental triggers; McFarland: 2015.

- Mpakosi, A.; Cholevas, V.; Tzouvelekis, I.; Passos, I.; Kaliouli-Antonopoulou, C.; Mironidou-Tzouveleki, M. Autoimmune diseases following environmental disasters: a narrative review of the literature. In Proceedings of the Healthcare; 2024; p. 1767. [Google Scholar]

- Ibironke, O. Air Pollution Particulate Matter Effects on Adaptive Human Antimycobacterial Immunity. Rutgers The State University of New Jersey, School of Graduate Studies, 2019.

- Slepicka, P.F.; Yazdanifar, M.; Bertaina, A. Harnessing mechanisms of immune tolerance to improve outcomes in solid organ transplantation: a review. Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12, 688460. [Google Scholar]

- Han, F.; Yang, X.; Xu, D.; Wang, Q.; Xu, D. Association between outdoor PM2. 5 and prevalence of COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Postgraduate Medical Journal 2019, 95, 612–618. [Google Scholar]

- Amubieya, O.; Weigt, S.; Shino, M.Y.; Jackson, N.J.; Belperio, J.; Ong, M.K.; Norris, K. Ambient air pollution exposure and outcomes in patients receiving lung transplant. JAMA Network Open 2024, 7, e2437148–e2437148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dizdar, O.S. Pneumonia after kidney transplant: incidence, risk factors, and mortality. 2014.

- Giannella, M.; Muñoz, P.; Alarcón, J.; Mularoni, A.; Grossi, P.; Bouza, E.; Group, P.S. Pneumonia in solid organ transplant recipients: a prospective multicenter study. Transplant Infectious Disease 2014, 16, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompilio, A.; Di Bonaventura, G. Ambient air pollution and respiratory bacterial infections, a troubling association: epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, and future challenges. Critical Reviews in Microbiology 2020, 46, 600–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippmann, M. Toxicological and epidemiological studies of cardiovascular effects of ambient air fine particulate matter (PM2. 5) and its chemical components: coherence and public health implications. Critical reviews in toxicology 2014, 44, 299–347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Di Maira, T.; Little, E.C.; Berenguer, M. Immunosuppression in liver transplant. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 2020, 46, 101681. [Google Scholar]

- Pope, C.A.; Bhatnagar, A. Does air pollution increase risk of mortality after cardiac transplantation? 2019, 74, 3036-3038.

- Dhanasekaran, R. Management of immunosuppression in liver transplantation. Clinics in liver disease 2017, 21, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Eckel, S.P.; Liu, L.; Lurmann, F.W.; Cockburn, M.G.; Gilliland, F.D. Particulate matter air pollution and liver cancer survival. International journal of cancer 2017, 141, 744–749. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Li, C.; Tang, X. The impact of PM2. 5 on the host defense of respiratory system. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2020, 8, 91. [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz, M.A.; Martikainen, M.-V.; Rönkkö, T.J.; Komppula, M.; Jalava, P.I.; Roponen, M. Urban air PM modifies differently immune defense responses against bacterial and viral infections in vitro. Environmental Research 2021, 192, 110244. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, S.; Qu, J.; Xu, N.; Xu, B. PM2. 5 inhalation aggravates inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Environmental Disease 2019, 4, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, C.; Tan, J.; Zhong, S.; Lai, L.; Chen, G.; Zhao, J.; Yi, C.; Wang, L.; Zhou, L.; Tang, T. Nrf2 mitigates prolonged PM2. 5 exposure-triggered liver inflammation by positively regulating SIKE activity: Protection by Juglanin. Redox biology 2020, 36, 101645. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, W.; Chen, L.; Wang, M.; Li, R.; Qin, S.; Song, X.; Ji, Y. Diesel exhaust PM2. 5 greatly deteriorates fibrosis process in pre-existing pulmonary fibrosis via ferroptosis. Environment international 2023, 171, 107706. [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi, P.; Floridi, L.; Boraschi, D.; Cuadrado, A.; Manda, G.; Levic, S.; D'Acquisto, F.; Hamilton, A.; Athersuch, T.J.; Selley, L. Oxidative stress and inflammation induced by environmental and psychological stressors: a biomarker perspective. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2018, 28, 852–872. [Google Scholar]

- Ravindranath, M.H.; El Hilali, F.; Filippone, E.J. The impact of inflammation on the immune responses to transplantation: tolerance or rejection? Frontiers in Immunology 2021, 12, 667834. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.-H.; Merzkani, M.; Murad, H.; Wang, M.; Bowe, B.; Lentine, K.L.; Al-Aly, Z.; Alhamad, T. Association of ambient fine particulate matter air pollution with kidney transplant outcomes. JAMA network Open 2021, 4, e2128190–e2128190. [Google Scholar]

- Salvadori, M.; Rosso, G.; Bertoni, E. Update on ischemia-reperfusion injury in kidney transplantation: Pathogenesis and treatment. World journal of transplantation 2015, 5, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Franzin, R.; Stasi, A.; Fiorentino, M.; Stallone, G.; Cantaluppi, V.; Gesualdo, L.; Castellano, G. Inflammaging and complement system: a link between acute kidney injury and chronic graft damage. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11, 734. [Google Scholar]

- Marroquin, C.E. Patient selection for kidney transplant. Surgical Clinics 2019, 99, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Yang, J.; Fang, X.; Lin, W.; Yang, Y. Membranous nephropathy: pathogenesis and treatments. MedComm 2024, 5, e614. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, J.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, H.; Chin, H.J.; Park, J.Y.; Jung, J.; Song, J.; Kwak, N.; Ryu, J.; Kim, S. Air quality and kidney health: Assessing the effects of PM10, PM2. 5, CO, and NO2 on renal function in primary glomerulonephritis. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 2024, 281, 116593. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, D.; Liu, Z. Fine particulate matter (PM2. 5) and chronic kidney disease. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology Volume 254 2021, 183-215.

- An, Y.; Liu, Z.-H. Air pollution and kidney diseases: PM2. 5 as an emerging culprit. Nephrology and Public Health Worldwide 2021, 199, 274–284. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Cao, F.; Xiao, J.-P.; Fang, X.-Y.; Wang, X.-R.; Ding, L.-H.; Wang, D.-G.; Pan, H.-F. Emerging role of air pollution in chronic kidney disease. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28, 52610–52624. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Neuberger, J.M.; Bechstein, W.O.; Kuypers, D.R.; Burra, P.; Citterio, F.; De Geest, S.; Duvoux, C.; Jardine, A.G.; Kamar, N.; Krämer, B.K. Practical recommendations for long-term management of modifiable risks in kidney and liver transplant recipients: a guidance report and clinical checklist by the consensus on managing modifiable risk in transplantation (COMMIT) group. Transplantation 2017, 101, S1–S56. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Lan, P. Activation of immune signals during organ transplantation. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2023, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Phillips, B.L.; Callaghan, C. The immunology of organ transplantation. Surgery (Oxford) 2017, 35, 333–340. [Google Scholar]

- Peruzzi, L.; Cocchi, E. Transplant Immunobiology. In Pediatric Solid Organ Transplantation: A Practical Handbook; Springer: 2023; pp. 19-44.

- Fu, H.; Liu, X.; Li, W.; Zu, Y.; Zhou, F.; Shou, Q.; Ding, Z. PM2. 5 exposure induces inflammatory response in macrophages via the TLR4/COX-2/NF-κB pathway. Inflammation 2020, 43, 1948–1958. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, M.D.; Nedjai, B.; Hurst, T.; Pennington, D.J. Cytokines and chemokines: At the crossroads of cell signalling and inflammatory disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research 2014, 1843, 2563–2582. [Google Scholar]

- de Morales, J.M.G.R.; Puig, L.; Daudén, E.; Cañete, J.D.; Pablos, J.L.; Martín, A.O.; Juanatey, C.G.; Adán, A.; Montalbán, X.; Borruel, N. Critical role of interleukin (IL)-17 in inflammatory and immune disorders: An updated review of the evidence focusing in controversies. Autoimmunity reviews 2020, 19, 102429. [Google Scholar]

- Veldhoen, M. Interleukin 17 is a chief orchestrator of immunity. Nature immunology 2017, 18, 612–621. [Google Scholar]

- Ponticelli, C.; Campise, M.R. The inflammatory state is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and graft fibrosis in kidney transplantation. Kidney International 2021, 100, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Steen, E.H.; Wang, X.; Balaji, S.; Butte, M.J.; Bollyky, P.L.; Keswani, S.G. The role of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-10 in tissue fibrosis. Advances in wound care 2020, 9, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, J.; Paster, J.; Benichou, G. Allorecognition by T lymphocytes and allograft rejection. Frontiers in immunology 2016, 7, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duneton, C.; Winterberg, P.D.; Ford, M.L. Activation and regulation of alloreactive T cell immunity in solid organ transplantation. Nature Reviews Nephrology 2022, 18, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Divito, S.J.; Zeng, Q.; Yatim, K.M.; Hughes, A.D.; Rojas-Canales, D.M.; Nakao, A.; Shufesky, W.J.; Williams, A.L. Graft-infiltrating host dendritic cells play a key role in organ transplant rejection. Nature communications 2016, 7, 12623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, L.; Gong, C.; Ying, L.; Fu, W.; Liu, S.; Dai, J.; Fu, Z. PM 2.5 affects establishment of immune tolerance in newborn mice by reducing PD-L1 expression. Journal of biosciences 2019, 44, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Qiao, G.; Liu, H.; Zhao, H.; Bai, J.; Zhang, H. Epigenetic regulation is involved in traffic-related PM2. 5 aggravating allergic airway inflammation in rats. Clinical Immunology 2022, 234, 108914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venosa, A. Senescence in pulmonary fibrosis: between aging and exposure. Frontiers in medicine 2020, 7, 606462. [Google Scholar]

- Vannella, K.M.; Wynn, T.A. Mechanisms of organ injury and repair by macrophages. Annual review of physiology 2017, 79, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, Y.; Manabe, I. Macrophages in inflammation, repair and regeneration. International immunology 2018, 30, 511–528. [Google Scholar]

- Yunna, C.; Mengru, H.; Lei, W.; Weidong, C. Macrophage M1/M2 polarization. European journal of pharmacology 2020, 877, 173090. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, M.M.; Liu, J.C.; Trujillo-de Santiago, G.; Cha, B.-H.; Vishwakarma, A.; Ghaemmaghami, A.M.; Khademhosseini, A. Delivery strategies to control inflammatory response: Modulating M1–M2 polarization in tissue engineering applications. Journal of Controlled Release 2016, 240, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajagopalan, S.; Al-Kindi, S.G.; Brook, R.D. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2018, 72, 2054–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanwar, V.; Gorr, M.W.; Velten, M.; Eichenseer, C.M.; Long III, V.P.; Bonilla, I.M.; Shettigar, V.; Ziolo, M.T.; Davis, J.P.; Baine, S.H. In utero particulate matter exposure produces heart failure, electrical remodeling, and epigenetic changes at adulthood. Journal of the American heart association 2017, 6, e005796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochando, J.; Ordikhani, F.; Jordan, S.; Boros, P.; Thomson, A.W. Tolerogenic dendritic cells in organ transplantation. Transplant International 2020, 33, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Shi, B. Tolerogenic dendritic cells and their applications in transplantation. Cellular & molecular immunology 2015, 12, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, Q.; Lakkis, F.G. Dendritic cells and innate immunity in kidney transplantation. Kidney international 2015, 87, 712–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya-Guzmán, M.J.; de Solminihac, J.; Padilla, C.; Rojas, C.; Pinto, C.; Himmel, T.; Pino-Lagos, K. Extracellular vesicles from immune cells: A biomedical perspective. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 13775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Lu, J. Macrophages in transplant rejection. Transplant Immunology 2022, 71, 101536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, F.T.; Memon, S.; Jin, P.; Imanguli, M.M.; Wang, H.; Rehman, N.; Yan, X.-Y.; Rose, J.; Mays, J.W.; Dhamala, S. Upregulation of IFN-inducible and damage-response pathways in chronic graft-versus-host disease. The Journal of Immunology 2016, 197, 3490–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safinia, N.; Scotta, C.; Vaikunthanathan, T.; Lechler, R.I.; Lombardi, G. Regulatory T cells: serious contenders in the promise for immunological tolerance in transplantation. Frontiers in immunology 2015, 6, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-F.; Lo, Y.-C.; Cheng, C.-H.; Furtmüller, G.J.; Oh, B.; Andrade-Oliveira, V.; Thomas, A.G.; Bowman, C.E.; Slusher, B.S.; Wolfgang, M.J. Preventing allograft rejection by targeting immune metabolism. Cell reports 2015, 13, 760–770. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Q.; Vincenti, F. Transplant trials with Tregs: perils and promises. The Journal of clinical investigation 2017, 127, 2505–2512. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.-L.; He, Y.-R.; Liu, Y.-J.; He, H.-Y.; Gu, Z.-Y.; Liu, Y.-M.; Liu, W.-J.; Luo, Z.; Ju, M.-J. The immunomodulation role of Th17 and Treg in renal transplantation. Frontiers in immunology 2023, 14, 1113560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tejchman, K.; Kotfis, K.; Sieńko, J. Biomarkers and mechanisms of oxidative stress—last 20 years of research with an emphasis on kidney damage and renal transplantation. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 8010. [Google Scholar]

- Matyas, C.; Haskó, G.; Liaudet, L.; Trojnar, E.; Pacher, P. Interplay of cardiovascular mediators, oxidative stress and inflammation in liver disease and its complications. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2021, 18, 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Lai, W.; Nie, H.; Shi, Y.; Zhu, L.; Yang, L.; Tian, L.; Li, K.; Bian, L.; Xi, Z. PM2. 5 triggers autophagic degradation of Caveolin-1 via endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS) to enhance the TGF-β1/Smad3 axis promoting pulmonary fibrosis. Environment international 2023, 181, 108290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.-X.; Ge, C.-X.; Qin, Y.-T.; Gu, T.-T.; Lou, D.-S.; Li, Q.; Hu, L.-F.; Feng, J.; Huang, P.; Tan, J. Prolonged PM2. 5 exposure elevates risk of oxidative stress-driven nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by triggering increase of dyslipidemia. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2019, 130, 542–556. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Li, Z.; Liao, Z.; Gao, S.; Hua, L.; Ye, X.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Wang, N.; Zhou, D. PM2. 5 induced pulmonary fibrosis in vivo and in vitro. Ecotoxicology and environmental safety 2019, 171, 112–121. [Google Scholar]

- Angelico, R.; Sensi, B.; Manzia, T.M.; Tisone, G.; Grassi, G.; Signorello, A.; Milana, M.; Lenci, I.; Baiocchi, L. Chronic rejection after liver transplantation: Opening the Pandora’s box. World journal of gastroenterology 2021, 27, 7771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, D.; Shi, H.; Liu, N.; Wang, C.; Tian, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z. PM2. 5 and water-soluble components induce airway fibrosis through TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling pathway in asthmatic rats. Molecular Immunology 2021, 137, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Pryor, J.T.; Cowley, L.O.; Simonds, S.E. The physiological effects of air pollution: particulate matter, physiology and disease. Frontiers in Public Health 2022, 10, 882569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, J. Function of PM2. 5 in the pathogenesis of lung cancer and chronic airway inflammatory diseases. Oncology letters 2018, 15, 7506–7514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marín-Palma, D.; Fernandez, G.J.; Ruiz-Saenz, J.; Taborda, N.A.; Rugeles, M.T.; Hernandez, J.C. Particulate matter impairs immune system function by up-regulating inflammatory pathways and decreasing pathogen response gene expression. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 12773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boor, P.; Floege, J. Renal allograft fibrosis: biology and therapeutic targets. American journal of transplantation 2015, 15, 863–886. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bhattarai, G.; Shrestha, S.K.; Sim, H.-J.; Lee, J.-C.; Kook, S.-H. Effects of fine particulate matter on bone marrow-conserved hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells: a systematic review. Experimental & Molecular Medicine 2024, 56, 118–128. [Google Scholar]

- Rajagopalan, S.; Brauer, M.; Bhatnagar, A.; Bhatt, D.L.; Brook, J.R.; Huang, W.; Münzel, T.; Newby, D.; Siegel, J.; Brook, R.D. Personal-level protective actions against particulate matter air pollution exposure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 142, e411–e431. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, S.; Fatima, S.; Asad, F.; Nazir, M.M.; Batool, S.; Ashraf, A. Combating Lead (Pb) Contamination: Integrating Biomonitoring, Advanced Detection, and Remediation for Environmental and Public Health. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution 2025, 236, 8. [Google Scholar]

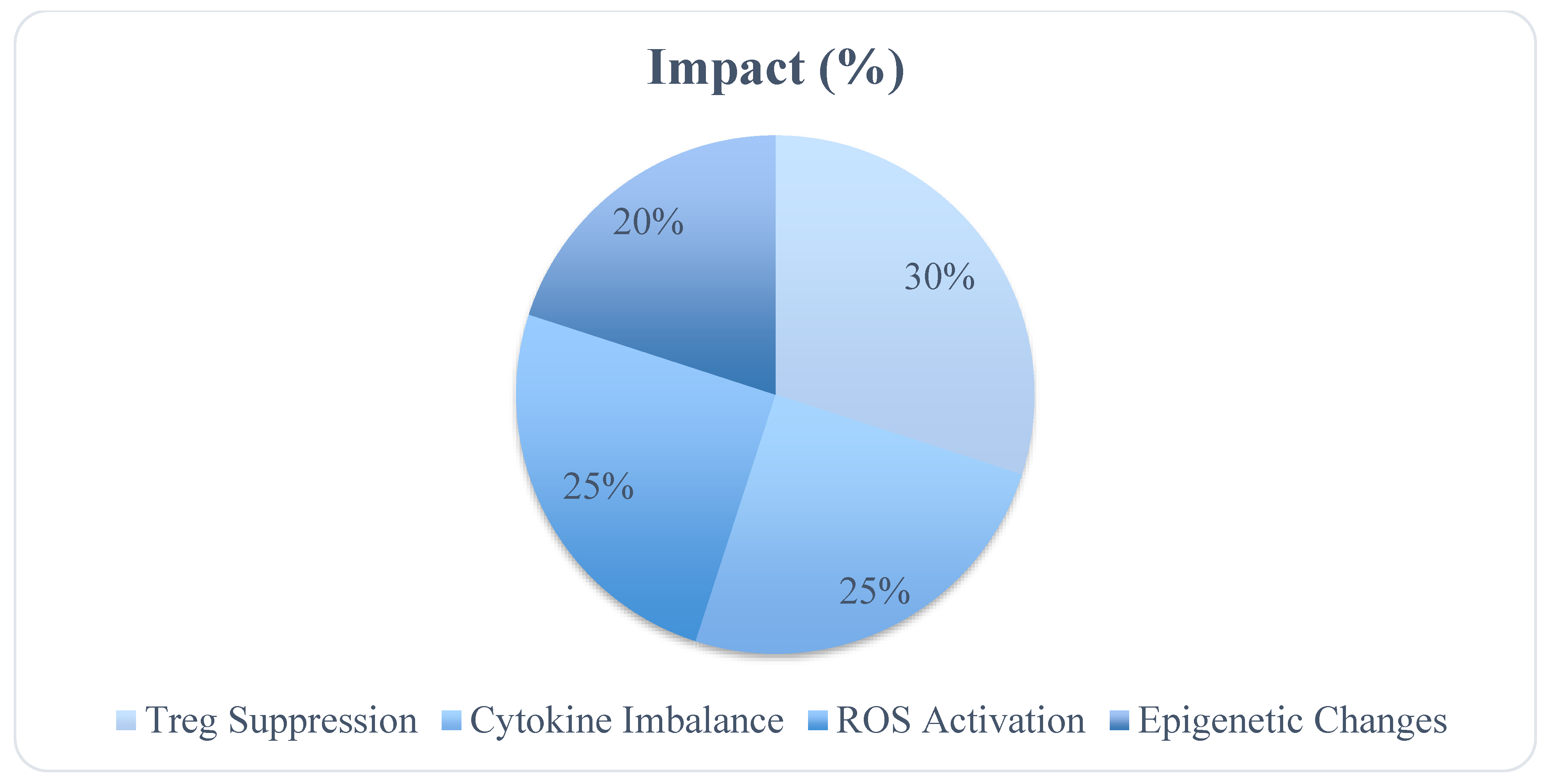

| Immune Component | Effect of PM2.5 |

|---|---|

| Regulatory T Cells (Tregs) | Suppressed, reducing immune tolerance |

| Pro-inflammatory Cytokines | Elevated TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β |

| Oxidative Stress Markers | Increased ROS production leading to DNA damage |

| Epigenetic Changes | Histone modifications affecting immune gene expression |

| Mechanism | Description | Key Molecule(s) | Impact on Immune System |

|---|---|---|---|

| PM2.5-induced Treg Dysfunction | Disruption of regulatory T cell function | TGF-β, FoxP3 | Reduced immune tolerance |

| Dendritic Cell Dysfunction | Impaired antigen presentation and activation of T-cells | IL-10, IL-12 | Altered immune response |

| Oxidative Stress | Elevated reactive oxygen species (ROS) impairs immune function | ROS, NF-κB | Chronic inflammation |

| Cytokine Imbalance | Overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines | TNF-α, IL-6 | Immune dysregulation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).