Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

21 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to identify grape genotypes resistant to powdery mildew to reduce pesticide use in vineyards. A total of 70 hybrid genotypes from Narince x Regent and Narince Kishmish Vatkana crosses, along with four grape varieties (Narince, Regent, Kishmish Vatkana, and Isabella), were evaluated for their susceptibility to powdery mildew. Inoculations were carried out under controlled greenhouse and laboratory conditions between 2021 and 2022. The study assessed the severity of infection by measuring mycelium and sporulation density on the leaves. Results showed significant variation in susceptibility, with genotypes exhibiting differences in infection severity, ranging from resistant (Regent) to highly susceptible (Narince). Genotypes NRG-7, NRG-146, NRG-174, NRG-195, NRG-196, NRG-197, and NRG-200, as well as cultivars Regent, Kishmish Vatkana, and Isabella, showed resistance to the disease, while Narince was highly sensitive. These resistant genotypes have potential for use in organic farming, offering an opportunity to reduce fungicide applications and enhance sustainable viticulture practices.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plantal Material

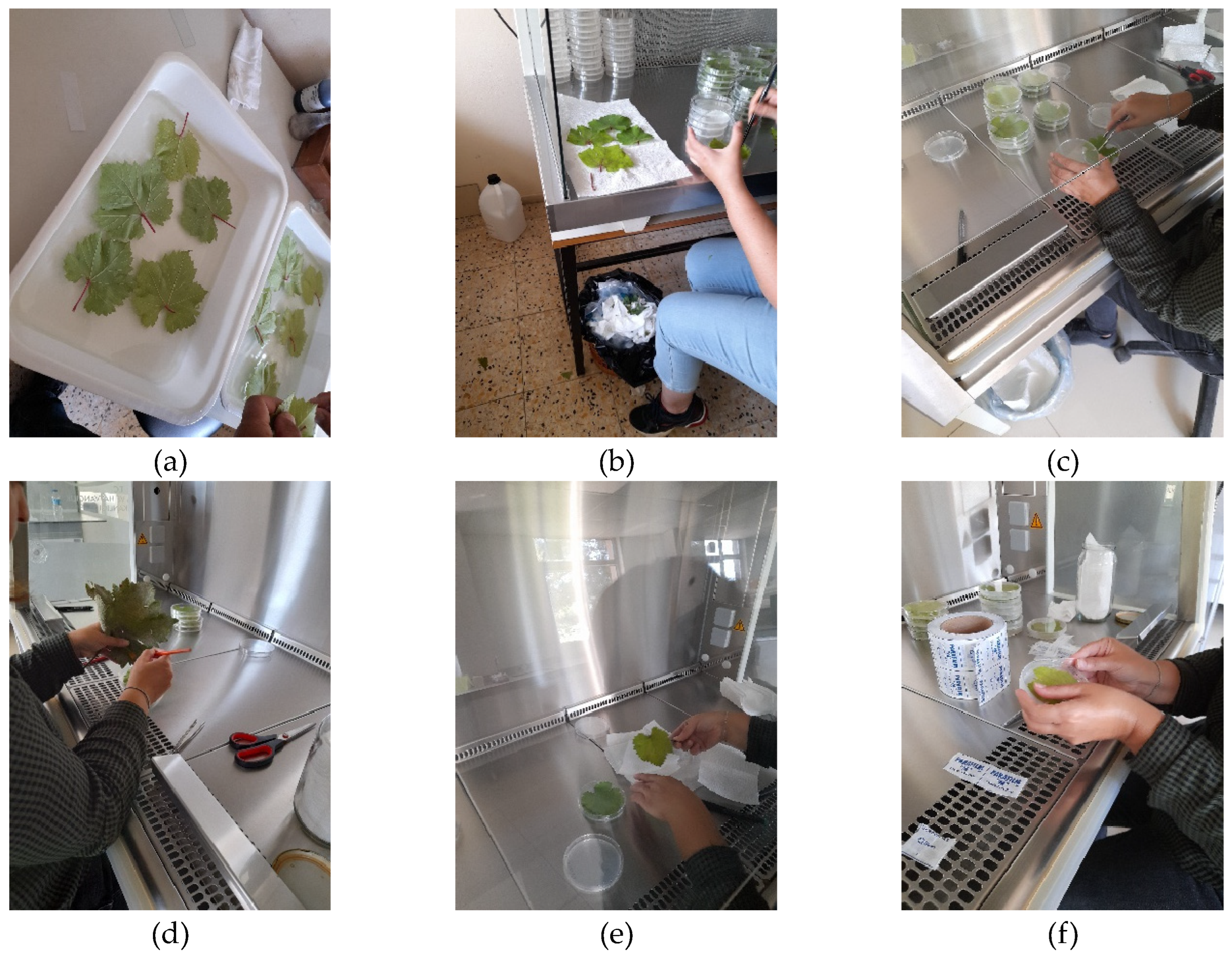

2.2. Inoculation, Counting and Evaluation of Powdery Mildew

2.3. The Calculation of Disease Severity

number of leaves x The highest scale value) x 100

2.4. The Inoculation, Counting and Evaluation of Powdery Mildew Under Laboratory Conditions

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Scale Values and Disease Severity in Genotypes in Terms of Powdery Mildew Infection

3.2. The Mycelium and Sporulation Densities of the Genotypes Were Determined Under Laboratory Conditions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lu, J., Liu, C. Grapevine breeding in China. In Grapevine breeding programs for the wine industry. Woodhead Publishing. 2015, pp. 273-310. [CrossRef]

- Stafne, E. T., Sleezer, S. M., & Clark, J. R. Grapevine breeding in the southern United States. In Grapevine breeding programs for the wine industry. Woodhead Publishing. 2015, 379-410. [CrossRef]

- Gadoury, D. M., Cadle-Davidson, L. A. N. C. E., Wilcox, W. F., Dry, I. B., Seem, R. C., & Milgroom, M. G. Grapevine powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator): a fascinating system for the study of the biology, ecology and epidemiology of an obligate biotroph. Molecular plant pathology. 2012, 13, 1, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, W. F., Gubler, W. D., & Uyemoto, J. K. (Eds.). Back Matter. In Compendium of Grape Diseases, Disorders, and Pests, Second Edition. The American Phytopathological Society. 2012, 199-232.

- Galet, P. Grape Varieties and Rootstock Varieties. Oenopluromedia, Chaintré, France. 1988.

- Alleweldt, G., & Possingham, J. V. Progress in grapevine breeding. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 1988, 75, 669-673. [CrossRef]

- Eibach, R., & Töpfer, R. Progress in grapevine breeding. In X International Conference on Grapevine Breeding and Genetics 1046. 2010, 197-209. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A. G. Grapevine breeding in France–A historical perspective. In Grapevine breeding programs for the wine industry. Woodhead Publishing. 2015, 65-76. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Liu, Y., He, P., Chen, J., Lamikanra, O., Lu, J. Evaluation of foliar resistance to Uncinula necator in Chinese wild Vitis species. Vitis. 1995. 34, 3, 159- 164.

- Population Reference Bureau. World Population Data Sheet. (http://www.prb.org/pdf17/2017_World_Population.pdf. 2017.

- Sezen K, Demir I, Demirbag, Z. Investigations on bacteria as a potential biological control agent of summer chafer, Amphimallon solstitiale L. (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Journal of Microbiology. 2005, 43, 5, 463-468.

- Altıkat, A., Turan, T., Torun, F. E., & Bingul, Z. Pesticide use in Turkey and its effects on the environment. Journal of Atatürk University Faculty of Agriculture. 2009, 40, 2, 87-92.

- Karacal, İ., & Tüfenkci, Ş. New Approaches in Plant Nutrition and Fertiliser-Environment Relationship. 2010.

- Eibach, R., & Töpfer, R. Traditional grapevine breeding techniques. In Grapevine breeding programs for the wine industry. Woodhead Publishing. 2015, 3-22. [CrossRef]

- Di Gaspero, G., & Foria, S. Molecular grapevine breeding techniques. In Grapevine breeding programs for the wine industry. Woodhead Publishing. 2015, 23-37. [CrossRef]

- Pavloušek, P. Grapevine breeding in Central and Eastern Europe. In Grapevine breeding programs for the wine industry. Woodhead Publishing. 2015, 211-244. [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, A. Development of new grape varieties tolerant to powdery mildew for vine leaf production (Doctoral Dissertation), Tokat Gaziosmanpaşa University, Tokat, Institute of Science and Technology, Department of Horticulture, Division of Vineyard Cultivation and Breeding, Tokat. 2023.

- Cangi, R., Adınır, M., Yagcı, A., Topçu, N., & Sucu, S. Economic Analysis of Different Production Models in Vineyards Producing Brine Leaves. Journal of the Institute of Science and Technology. 2011, 1, 2, 77-84.

- Anonymous. (https://www.mgm.gov.tr/ dataevaluationprovincesandprovinces statistics.aspx?k=undefined&m=TOKAT). 2022.

- VIVC. Vitis International Variety Cataloque VIVC https://www.vivc.de/ 2020.

- Kozma, P., Kiss, E., Hoffmann, S., Galbács, Z.S., Dula, T. Using the powdery mildew resistant Muscadinia rotundifolia and Vitis vinifera ’Kishmish vatkana’ for breeding new cultivars. IX Int. Conf. Grape Genet. Breed. 2006, 827, 559-56. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, S., G. Di Gaspero, L. Kovács, S. Howard, E., Z. Galbacs, R. Testolin, P. Kozma. Resistance to Erysiphe necator in the grapevine ‘Kishmish Vatkana’ is controlled by a single locus through restriction of hyphal growth. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2008, 116, 3, 427-438. [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, Z., Atak, A., Akkurt, M. Determination of downy and powdery mildew resistance of some Vitis spp. Ciência e Técnica Vitivinícola. 2019, 34, 1, 15-24. [CrossRef]

- Atak, A., Akkurt. M., Polat. Z., Çelik. H., Kahraman, K.A., Akgul, D.S., Ozer, N., Soylemezoglu, G., Şire, G.G., Eibach, R. Susceptibility to downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola) and powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator) of different Vitis cultivars and genotypes. Ciência Téc. Vitiv. 2017, 32, 1, 23-32. [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z. Methods in Plant Pathology. Agricultural Press, Beijing, P. R. China. 1979.

- Townsend, G. R. Methods for estimating losses caused by diseases in fungicide experiments. Plant Disease Reporter. 1943, 27, 340-343.

- Blanc, S. Cartographie génétique et analyse de la résistance au mildiou et à l’oïdium de la vigne chez Muscadinia rotundifolia (Doctoral dissertation, Université de Strasbourg). 2012.

- Schnee, S., Viret. O., Gindro, K. Role of stilbenes in the resistance of grapevine to powdery mildew. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology. 2008, 72, 4-6, 128-133. [CrossRef]

- Miclot, A. S., Wiedemann-Merdinoglu, S., Duchêne, E., Merdinoglu, D., Mestre, P. A standardised method for the quantitative analysis of resistance to grapevine powdery mildew. European journal of plant pathology. 2012, 133, 2, 483-495. [CrossRef]

- Doster, M. A., & Schnathorst, W. C. Comparative susceptibility of various grapevine cultivars to the powdery mildew fungus Uncinula necator. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 1985, 36, 2, 101-104. [CrossRef]

- Eibach, R. Investigations on the inheritance of resistance features to mildew diseases. In VII International Symposium on Grapevine Genetics and Breeding 528, 1998, 461-466. [CrossRef]

- Pavloušek, P. Evaluation of resistance to powdery mildew in grapevine genetic resources. Journal of Central European Agriculture. 2007, 8, 1, 105-114.

- Khiavi, H., Shikhlinski, H., Ahari, A., & Heydari, A. Evaluation of different grape varieties for resistance to powdery mildew caused by Uncinula necator. Journal of plant protection research. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Gaforio, L., Garcia-Munoz, S., Cabello, F., & Munoz-Organero, G. Evaluation of susceptibility to powdery mildew (Erysiphe necator) in Vitis vinifera varieties. Vitis. 2011, 50, 3, 123-126.

- Fayyaz, L., Tenscher, A., Viet Nguyen, A., Qazi, H., & Walker, M. A. Vitis species from the southwestern United States vary in their susceptibility to powdery mildew. Plant Disease. 2021, 105, 9, 2418-2425. [CrossRef]

- Khiavi, H. K., Abbas Davoodi, A. Resistance evaluation of some commercial Vitis vinifera varieties to powdery mildew Erysiphe necator Schwein. in two regions of Iran. J. Crop Prot. 2016, 5, 2, 229-237. [CrossRef]

- Vojtovic, K.A., Naidenova, I.N., Kropis, E. Immunité des arbres fruitiers et de la Vigne. Zaschita rastenii ot vreditelei i boleznei. 1965, 10, 10, 21-23.

- Pospisilova, D. Sensibilité des cépages de Vitis vinifera á l’Oidium de la Vigne (Uncinula necator Schw. Burr.). Proc. IIe Symp. Int. Sur l’Amer. De la Vigne, Bordeaux, 14-18 Juin 1977. INRA. 1978, 251-257.

- Salotti, I., Bove, F., & Rossi, V. Field evaluation of grapevines resistant to downy and powdery mildews. In BIO Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences. 2022, 50, 02003. [CrossRef]

- Schwab, A. L., Knott, R., Schottdorf, W. Results from new fungus-tolerant grapevine varieties for organic viticulture. In Proceedings 6th International Congress on Organic Viticulture. Stiftung Ökologie & Landbau, Bad Dürkheim. 2000, 225-227.

- Eibach, R., & Töpfer, R. Success in resistance breeding:” Regent” and its steps into the market. In VIII International Conference on Grape Genetics and Breeding 603. 2002, 687-691. [CrossRef]

- Coleman, C., Copetti, D., Cipriani, G., Hoffmann, S., Kozma, P., Kovács, L., ... & Di Gaspero, G. The powdery mildew resistance gene REN1 co-segregates with an NBS-LRR gene cluster in two Central Asian grapevines. BMC genetics. 2009, 10, 1, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Riaz, S., Boursiquot, J.M., Dangl, G.S., Lacombe. T., et al. Identification of mildew resistance in wild and cultivated Central Asian grape germplasm. BMC Plant Biol. 2013, 13, 149. [CrossRef]

- Ozer, N., Atak, A., Söylemezoglu, G., Çelik, H., Akgül, D. S., Akkurt, M., ... & Polat, Z. The collection of grape varieties and types resistant to powdery mildew and mildew diseases, the determination of resistance to diseases by different methods, and the determination of genotypes that can be used as parents in resistance breeding studies. TUBITAK TOVAG Project, Project No: 1130641. 2017.

- Jones, J.D.G.; Dangl, J.L. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006, 444, 323-329. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.R., Han, Y.T., Zhao, F.L., Li, Y.J., Cheng, Y., Ding, Q., Wang, Y.J., Wen, Y.Q. 2016. Identification and utilization of a new Erysiphe necator isolate NAFU1 to quickly evaluate powdery mildew resistance in wild Chinese grapevine species using detached leaves. Plant Physiol. Biochem, 98: 12-24. [CrossRef]

- He, P., Shan, L., Lin, N.C., Martin, G.B., Kemmerling, B., Nürnberger, T., Sheen, J. Specific bacterial suppressors of MAMP signaling upstream of MAPKKK in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Cell. 2006, 125, 563-575. [CrossRef]

| The scale value | The infection rate (%) |

|---|---|

| 0 | absent |

| 1 | - 5.0 |

| 2 | 5.1–15.3 |

| 3 | 15.1–30.4 |

| 4 | 30.1–45.5 |

| 5 | 45.1- 65.6 |

| 6 | 65.1- 85.7 |

| 7 | 85.0–100.0 |

| The year 2021 | The year 2022 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | The scale value | The severity of the disease | SI (%) | SI | The scale value | The severity of the disease | SI (%) | SI | |

| NRG-002 | 7 | 80.00 | 50-100 | HS | 7 | 62.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-004 | 2 | 6,29 | 5.1-25 | R | 5 | 31.43 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-005 | 7 | 68.00 | 50-100 | HS | 7 | 64.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-007 | 3 | 8.57 | 5.1-25 | R | 4 | 18.29 | 5.1-25 | R | |

| NRG-009 | 4 | 14.86 | 5.1-25 | R | 5 | 35.71 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-012 | 6 | 44.57 | 25.1-50 | S | 7 | 62.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-013 | 7 | 84.00 | 50-100 | HS | 7 | 64.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-025 | 6 | 53.14 | 50-100 | HS | 5 | 22.86 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-028 | 5 | 28.57 | 25.1-50 | S | 5 | 35.71 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-033 | 7 | 100.00 | 50-100 | HS | 7 | 72.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-060 | 4 | 20.57 | 5.1-25 | R | 7 | 68.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-061 | 7 | 64.00 | 50-100 | HS | 7 | 66.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-062 | 3 | 10.29 | 5.1-25 | R | 7 | 68.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-063 | 3 | 12.00 | 5.1-25 | R | 7 | 84.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-064 | 3 | 10.29 | 5.1-25 | R | 7 | 48.00 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-065 | 4 | 12.57 | 5.1-25 | R | 7 | 56.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-066 | 2 | 4.57 | 0.1-5 | HR | 5 | 25.71 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-067 | 4 | 17.14 | 5.1-25 | R | 7 | 68.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-068 | 4 | 20.57 | 5.1-25 | R | 7 | 76.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-075 | 7 | 46.00 | 25.1-50 | S | 7 | 64.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-080 | 2 | 2.29 | 0.1-5 | HR | 7 | 70.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-085 | 7 | 68.00 | 50-100 | HS | 7 | 74.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-088 | 3 | 11.14 | 5.1-25 | R | 7 | 74.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-089 | 2 | 4.57 | 0.1-5 | HR | 7 | 39.43 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-092 | 3 | 6.86 | 5.1-25 | R | 5 | 32.86 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-093 | 4 | 14.86 | 5.1-25 | R | 7 | 60.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-094 | 4 | 28.57 | 25.1-50 | S | 5 | 27.14 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-098 | 3 | 12.00 | 5.1-25 | R | 5 | 30.00 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-102 | 7 | 92.00 | 50-100 | HS | 7 | 72.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-104 | 5 | 32.86 | 25.1-50 | S | 7 | 60.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-109 | 6 | 41.14 | 25.1-50 | S | 7 | 56.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-110 | 4 | 13.71 | 5.1-25 | R | 5 | 25.71 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-115 | 3 | 9.43 | 5.1-25 | R | 5 | 25.71 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-120 | 4 | 28.57 | 25.1-50 | S | 7 | 64.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-128 | 3 | 15.43 | 5.1-25 | R | 6 | 48.00 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-137 | 5 | 37.14 | 25.1-50 | S | 6 | 36.00 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-146 | 2 | 5.71 | 5.1-25 | R | 5 | 24.29 | 5.1-25 | R | |

| NRG-147 | 4 | 41.14 | 25.1-50 | S | 5 | 27.14 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-161 | 4 | 18.29 | 5.1-25 | R | 5 | 32.86 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-162 | 2 | 6.86 | 5.1-25 | R | 5 | 40.00 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-164 | 4 | 16.00 | 5.1-25 | R | 7 | 64.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-165 | 3 | 5.14 | 5.1-25 | R | 6 | 54.86 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-167 | 3 | 12.86 | 5.1-25 | R | 6 | 49.71 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-170 | 3 | 19.71 | 5.1-25 | R | 7 | 70.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-174 | 3 | 12.86 | 5.1-25 | R | 4 | 18.29 | 5.1-25 | R | |

| NRG-175 | 1 | 2.29 | 0.1-5 | HR | 5 | 38.57 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-176 | 3 | 7.71 | 5.1-25 | R | 7 | 64.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-177 | 3 | 20.57 | 5.1-25 | R | 7 | 68.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-178 | 5 | 34.29 | 25.1-50 | S | 7 | 68.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-179 | 4 | 18.29 | 5.1-25 | R | 5 | 25.71 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-181 | 2 | 3.43 | 0.1-5 | HR | 7 | 46.00 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-182 | 6 | 60.00 | 50-100 | HS | 7 | 72.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-183 | 1 | 3.71 | 0.1-5 | HR | 5 | 24.29 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-193 | 4 | 27.43 | 25.1-50 | S | 5 | 24.29 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-195 | 2 | 5.14 | 5.1-25 | R | 4 | 17.14 | 5.1-25 | R | |

| NRG-196 | 3 | 13.71 | 5.1-25 | R | 4 | 16.00 | 5.1-25 | R | |

| NRG-197 | 2 | 9.14 | 5.1-25 | R | 4 | 18.29 | 5.1-25 | R | |

| NRG-198 | 2 | 6.29 | 5.1-25 | R | 6 | 37.71 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-199 | 1 | 2.29 | 0.1-5 | HR | 5 | 25.71 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-200 | 1 | 0.86 | 0.1-5 | HR | 5 | 22.86 | 5.1-25 | R | |

| NRG-201 | 1 | 2.29 | 0.1-5 | HR | 5 | 27.14 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-211 | 5 | 28.57 | 25.1-50 | S | 7 | 66.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-213 | 3 | 12.00 | 5.1-25 | R | 7 | 64.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-217 | 6 | 48 | 25.1-50 | S | 6 | 48.00 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NRG-218 | 5 | 30 | 25.1-50 | S | 7 | 70.00 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NRG-219 | 2 | 4 | 0.1-5 | HR | 6 | 44.57 | 25.1-50 | S | |

| NKV-004 | 7 | 50 | 50-100 | HS | 7 | 64 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NKV-010 | 7 | 60 | 50-100 | HS | 7 | 72 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NKV-016 | 7 | 76 | 50-100 | HS | 7 | 100 | 50-100 | HS | |

| NKV-017 | 7 | 66 | 50-100 | HS | 7 | 80 | 50-100 | HS | |

| Narince | 7 | 100 | 50-100 | HS | 6.6 | 76.3 | 50-100 | HS | |

| Regent | 3 | 9.7 | 5.1-25 | R | 2.6 | 8.7 | 5.1-25 | R | |

| K.Vatkana | 3 | 9.7 | 5.1-25 | R | 2.6 | 11 | 5.1-25 | R | |

| Isabella | 2,6 | 6 | 5.1-25 | R | 2 | 5.8 | 5.1-25 | R | |

| Genotype | The density of mycelium and sporulation | Genotype | The density of mycelium and sporulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| NRG-002 | 4.6 d-g | NRG-170 | 4.2 e-g |

| NRG-004 | 3.8 f-h | NRG-174 | 5.4 b-e |

| NRG-005 | 1.8 j | NRG-176 | 3.8 f-h |

| NRG-007 | 3.8 f-h | NRG-177 | 4.2 e-g |

| NRG-012 | 2.2 ıj | NRG-179 | 3.8 f-h |

| NRG-013 | 2.6 h-j | NRG-181 | 6.2 a-c |

| NRG-028 | 5.4 b-e | NRG-183 | 5.8 b-d |

| NRG-033 | 1.8 j | NRG-193 | 5.8 b-d |

| NRG-061 | 3.8 f-h | NRG-194 | 5.0 c-f |

| NRG-064 | 4.6 d-g | NRG-195 | 5.8 b-d |

| NRG-066 | 5.0 c-f | NRG-196 | 5.0 c-f |

| NRG-075 | 3.4 g-ı | NRG-197 | 4.6 d-g |

| NRG-089 | 4.2 e-g | NRG-198 | 3.8 f-h |

| NRG-092 | 6.6 ab | NRG-199 | 4.2 e-g |

| NRG-095 | 1.8 j | NRG-200 | 4.2 e-g |

| NRG-098 | 4.2 e-g | NRG-201 | 5.8 b-d |

| NRG-102 | 4.2 e-g | NRG-217 | 4.2 e-g |

| NRG-104 | 4.2 e-g | NRG-219 | 5.0 c-f |

| NRG-110 | 3.8 f-h | NKV-004 | 2.6 h-j |

| NRG-115 | 4.6 d-g | NKV-010 | 2.2 ıj |

| NRG-137 | 4.6 d-g | NKV-016 | 1.8 j |

| NRG-146 | 4.6 d-g | NKV-017 | 1.8 j |

| NRG-147 | 3.8 f-h | Narince | 1.8 j |

| NRG-161 | 5.8 b-d | Regent | 6.8 ab |

| Isabella | 7.4 a | K. Vatkana | 6.6 ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).