Submitted:

21 February 2025

Posted:

21 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs)

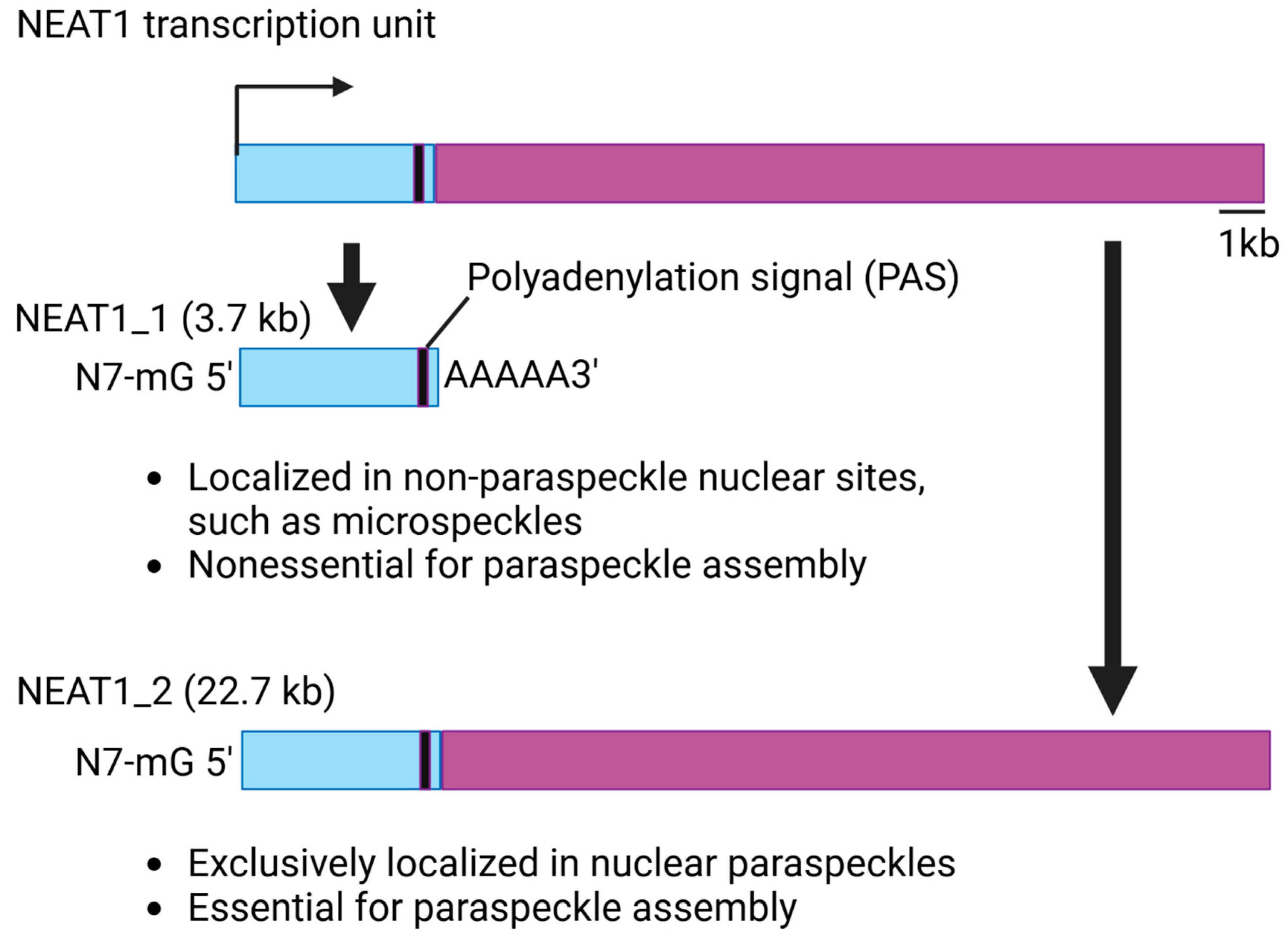

1.2. Structure and Function of NEAT1

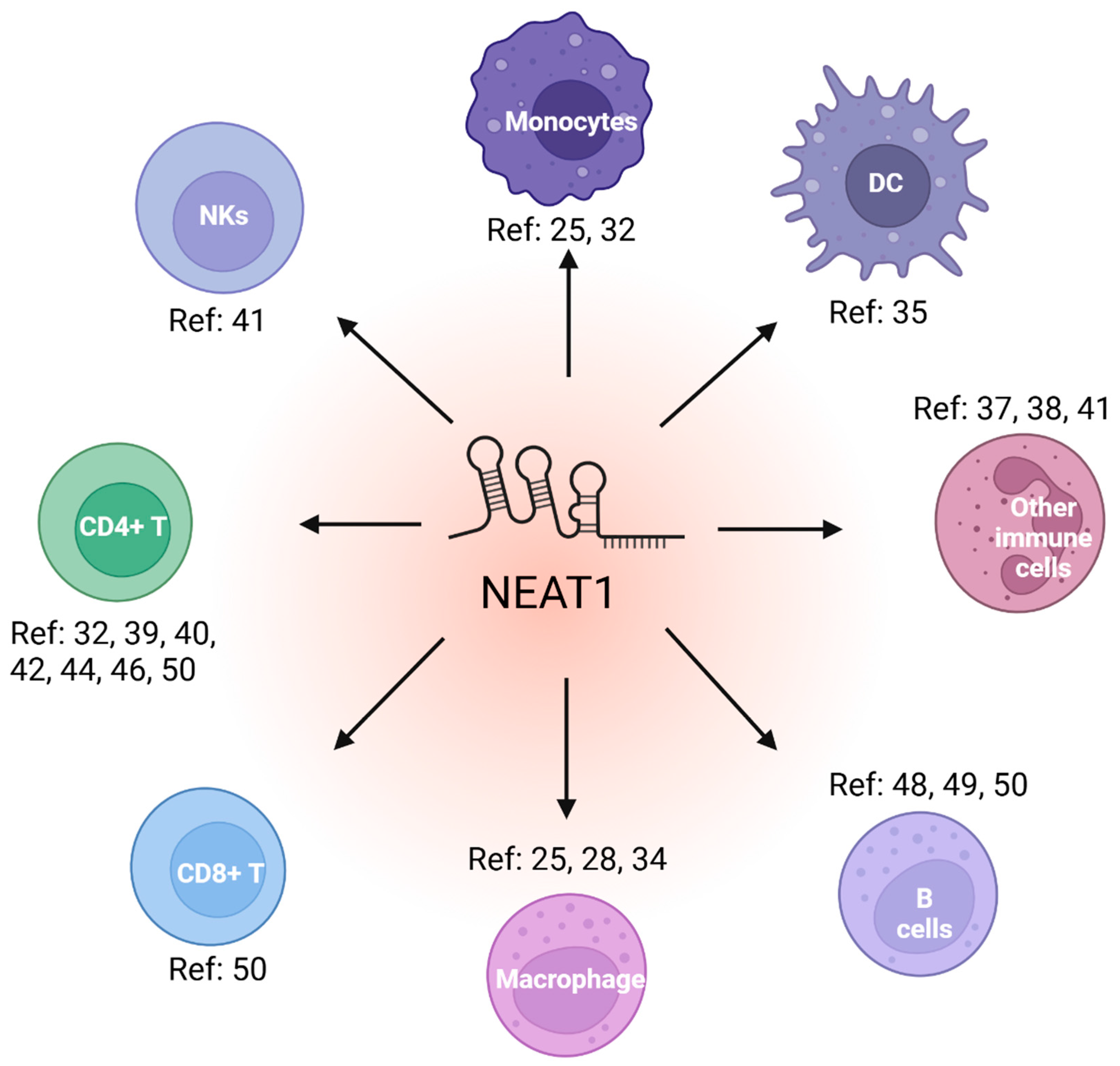

2. NEAT1 in immune cell function

2.1. NEAT1 regulates innate immune cell

2.2. NEAT1 regulates adaptive immune cell function

2.3. NEAT1 as a biomarker and therapeutic target in immune-related diseases

3. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Yi, Q.; et al. CircRNA and lncRNA-encoded peptide in diseases, an update review. Mol. Cancer 23, 214 (2024).

- Zhang, Y. LncRNA-encoded peptides in cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 17, 66 (2024).

- Tian, H.; Tang, L.; Yang, Z.; Xiang, Y.; Min, Q.; Yin, M.; You, H.; Xiao, Z.; Shen, J. Current understanding of functional peptides encoded by lncRNA in cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2024, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponting, C.P.; Oliver, P.L.; Reik, W. Evolution and Functions of Long Noncoding RNAs. <bold>2009</bold>, <italic>136</italic>. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.M.; Chang, H.Y. Long Noncoding RNAs in Cancer Pathways. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Tu, C.; Liu, Y. Role of lncRNAs in aging and age-related diseases. Aging Med. 2018, 1, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Sachdeva, M.; Xu, E.; Robinson, T.J.; Luo, L.; Ma, Y.; Williams, N.T.; Lopez, O.; Cervia, L.D.; Yuan, F.; et al. The Long Noncoding RNANEAT1Promotes Sarcoma Metastasis by Regulating RNA Splicing Pathways. Mol. Cancer Res. 2020, 18, 1534–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, J.J.; Chang, H.Y. Unique features of long non-coding RNA biogenesis and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2016, 17, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, L.; Feng, C.; Qin, Y.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, L. LncBook 2.0: integrating human long non-coding RNAs with multi-omics annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 51, D186–D191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Zhou, P.; Kwon, E.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; Weng, Z.; Zhou, C. Flnc: Machine Learning Improves the Identification of Novel Long Noncoding RNAs from Stand-Alone RNA-Seq Data. Non-Coding RNA 2022, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarropoulos, I.; Marin, R.; Cardoso-Moreira, M.; Kaessmann, H. Developmental dynamics of lncRNAs across mammalian organs and species. Nature 2019, 571, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Castillo, M. , M Elsayed, A., López-Berestein, G., Amero, P. & Rodríguez-Aguayo, C. An overview of the immune modulatory properties of long non-coding RNAs and their potential use as therapeutic targets in cancer. Noncoding RNA 9, 70 (2023).

- Statello, L.; Guo, C.-J.; Chen, L.-L.; Huarte, M. Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atianand, M.K.; Caffrey, D.R.; Fitzgerald, K.A. Immunobiology of Long Noncoding RNAs. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 35, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-L.; Carmichael, G.G. Altered Nuclear Retention of mRNAs Containing Inverted Repeats in Human Embryonic Stem Cells: Functional Role of a Nuclear Noncoding RNA. 2009, 35, 467–478. [CrossRef]

- Clemson, C.M.; Hutchinson, J.N.; Sara, S.A.; Ensminger, A.W.; Fox, A.H.; Chess, A.; Lawrence, J.B. An Architectural Role for a Nuclear Noncoding RNA: NEAT1 RNA Is Essential for the Structure of Paraspeckles. 2009, 33, 717–726. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, Y. T. F. , Ideue, T., Sano, M., Mituyama, T. & Hirose, T. MENepsilon/beta noncoding RNAs are essential for structural integrity of nuclear paraspeckles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 2525–2530 (2009).

- Naganuma, T.; Nakagawa, S.; Tanigawa, A.; Sasaki, Y.F.; Goshima, N.; Hirose, T. Alternative 3′-end processing of long noncoding RNA initiates construction of nuclear paraspeckles. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 4020–4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Harvey, A.R.; Hodgetts, S.I.; Fox, A.H. Functional dissection of NEAT1 using genome editing reveals substantial localization of the NEAT1_1 isoform outside paraspeckles. RNA 2017, 23, 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, T.; Souquere, S.; Chujo, T.; Kobelke, S.; Chong, Y.S.; Fox, A.H.; Bond, C.S.; Nakagawa, S.; Pierron, G.; Hirose, T. Functional Domains of NEAT1 Architectural lncRNA Induce Paraspeckle Assembly through Phase Separation. Mol. Cell 2018, 70, 1038–1053.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, K.; Imamachi, N.; Akizuki, G.; Kumakura, M.; Kawaguchi, A.; Nagata, K.; Kato, A.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Sato, H.; Yoneda, M.; et al. Long Noncoding RNA NEAT1-Dependent SFPQ Relocation from Promoter Region to Paraspeckle Mediates IL8 Expression upon Immune Stimuli. Mol. Cell 2014, 53, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naveed, A.; et al. NEAT1 polyA-modulating antisense oligonucleotides reveal opposing functions for both long non-coding RNA isoforms in neuroblastoma. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 78, 2213–2230 (2021).

- Isobe, M.; Toya, H.; Mito, M.; Chiba, T.; Asahara, H.; Hirose, T.; Nakagawa, S. Forced isoform switching of Neat1_1 to Neat1_2 leads to the loss of Neat1_1 and the hyperformation of paraspeckles but does not affect the development and growth of mice. RNA 2019, 26, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, A. et al. PolyA-modulating antisense oligonucleotides reveal opposing functions for long non-coding RNA NEAT1 isoforms in neuroblastoma. bioRxiv (2020). [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, M.; Ma, Y.; Ye, W.; Si, Y.; Zheng, X.; Liu, H.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; et al. LncRNA NEAT1 Potentiates SREBP2 Activity to Promote Inflammatory Macrophage Activation and Limit Hantaan Virus Propagation. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 849020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Han, P.; Ye, W.; Chen, H.; Zheng, X.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, L.; Yu, L.; Wu, X.; Xu, Z.; et al. The Long Noncoding RNA NEAT1 Exerts Antihantaviral Effects by Acting as Positive Feedback for RIG-I Signaling. J. Virol. 2017, 91, e02250–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morchikh, M.; Cribier, A.; Raffel, R.; Amraoui, S.; Cau, J.; Severac, D.; Dubois, E.; Schwartz, O.; Bennasser, Y.; Benkirane, M. HEXIM1 and NEAT1 Long Non-coding RNA Form a Multi-subunit Complex that Regulates DNA-Mediated Innate Immune Response. Mol. Cell 2017, 67, 387–399.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Cao, L.; Zhou, R.; Yang, X.; Wu, M. The lncRNA Neat1 promotes activation of inflammasomes in macrophages. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Dong, L.; Liu, Y.-M.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, C.; Liu, K.; Liu, L.; Song, Y.-H.; Sun, M.; Xiang, X.-C.; et al. Nickle-cobalt alloy nanocrystals inhibit activation of inflammasomes. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2023, 10, nwad179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, K.; Satoh, T.; Sugihara, F.; Sato, Y.; Okamoto, T.; Mitsui, Y.; Yoshio, S.; Li, S.; Nojima, S.; Motooka, D.; et al. Dysregulated Expression of the Nuclear Exosome Targeting Complex Component Rbm7 in Nonhematopoietic Cells Licenses the Development of Fibrosis. Immunity 2020, 52, 542–556.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Tang, A.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhao, L.; Xiao, Z.; Shen, S. Inhibition of lncRNA NEAT1 suppresses the inflammatory response in IBD by modulating the intestinal epithelial barrier and by exosome-mediated polarization of macrophages. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2018, 42, 2903–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gast, M.; Rauch, B.H.; Haghikia, A.; Nakagawa, S.; Haas, J.; Stroux, A.; Schmidt, D.; Schumann, P.; Weiss, S.; Jensen, L.; et al. Long noncoding RNA NEAT1 modulates immune cell functions and is suppressed in early onset myocardial infarction patients. Cardiovasc. Res. 2019, 115, 1886–1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Y.; et al. Toll-like receptors, long non-coding RNA NEAT1, and RIG-I expression are associated with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients in the active phase. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 33, e22886 (2019).

- Azam, S.; Armijo, K.S.; Weindel, C.G.; Chapman, M.J.; Devigne, A.; Nakagawa, S.; Hirose, T.; Carpenter, S.; Watson, R.O.; Patrick, K.L. The early macrophage response to pathogens requires dynamic regulation of the nuclear paraspeckle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2024, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zheng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Li, S.; Chen, L.; Jin, X.; Hou, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, Q.; Li, J.; et al. Knockdown of NEAT1 induces tolerogenic phenotype in dendritic cells by inhibiting activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. Theranostics 2019, 9, 3425–3442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, C.; Peng, X.; Xie, T.; Lu, X.; Liu, F.; Wu, H.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Cheng, L.; Wu, N. Detection of the long noncoding RNAs nuclear-enriched autosomal transcript 1 (NEAT1) and metastasis associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 in the peripheral blood of HIV-1-infected patients. HIV Med. 2015, 17, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imam, H.; Bano, A.S.; Patel, P.; Holla, P.; Jameel, S. The lncRNA NRON modulates HIV-1 replication in a NFAT-dependent manner and is differentially regulated by early and late viral proteins. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, srep08639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, C.-Y.; Yedavalli, V.S.R.K.; Jeang, K.-T. NEAT1 Long Noncoding RNA and Paraspeckle Bodies Modulate HIV-1 Posttranscriptional Expression. mBio 2013, 4, e00596–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hu, P.-W.; Couturier, J.; Lewis, D.E.; Rice, A.P. HIV-1 replication in CD4+ T cells exploits the down-regulation of antiviral NEAT1 long non-coding RNAs following T cell activation. Virology 2018, 522, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shui, X.; et al. Knockdown of lncRNA NEAT1 inhibits Th17/CD4+ T cell differentiation through reducing the STAT3 protein level. J. Cell. Physiol. 234, 22477–22484 (2019).

- Chen, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, S. Silence of long noncoding RNA NEAT1 exerts suppressive effects on immunity during sepsis by promoting microRNA-125-dependent MCEMP1 downregulation. IUBMB Life 2019, 71, 956–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Lin, X.; Chen, M. LncRNA NEAT1 correlates with Th17 cells and proinflammatory cytokines, also reflects stenosis degree and cholesterol level in coronary heart disease patients. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e23975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Zhao, S.; Huang, W.; Huang, L.; Huang, M.; Luo, X.; Chang, S. Aberrant expressions of circulating lncRNA NEAT1 and microRNA-125a are linked with Th2 cells and symptom severity in pediatric allergic rhinitis. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, X. , Liu, H. & Li, T. Lncrna NEAT1 regulates Th1/Th2 in pediatric asthma by targeting MicroRNA-217/GATA3. Iran. J. Public Health 52, 106–117 (2023).

- Liu, X.; et al. The promotion of humoral immune responses in humans via SOCS1-mediated Th2-bias following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Vaccines (Basel) 11, 1730 (2023).

- Huang, S.; Dong, D.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Geng, J.; Zhao, Y. Long non-coding RNA nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 promotes activation of T helper 2 cells via inhibiting STAT6 ubiquitination. Hum. Cell 2021, 34, 800–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Smet, M. D.; et al. Understanding uveitis: the impact of research on visual outcomes. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 30, 452–470 (2011).

- Chen, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, K.; Ma, B.; Li, X.; Wei, R.; Nian, H. LncRNA Neat1 targets NonO and miR-128-3p to promote antigen-specific Th17 cell responses and autoimmune inflammation. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Wang, X.-S.; Yao, Y.; Si, Y.-M.; Wang, X.-Z.; Jia, M.-N.; Zhou, D.-B.; Yu, J.; Cao, X.-X.; Li, J. Single-cell transcriptome analysis reveals stem cell-like subsets in the progression of Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Exp. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, P.; Mehta, P.; Soni, J.; Tardalkar, K.; Joshi, M.; Pandey, R. Cell-specific housekeeping role of lncRNAs in COVID-19-infected and recovered patients. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2024, 6, lqae023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P. , Duan, S. & Fu, A. Long noncoding RNA NEAT1 correlates with higher disease risk, worse disease condition, decreased miR-124 and miR-125a and predicts poor recurrence-free survival of acute ischemic stroke. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 34, e23056 (2020).

- Shen, J.; Pan, L.; Chen, W.; Wu, Y. Long non-coding RNAs MALAT1, NEAT1 and DSCR4 can be serum biomarkers in predicting urosepsis occurrence and reflect disease severity. Exp. Ther. Med. 2024, 28, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Huang, C.; Luo, Y.; He, F.; Zhang, R. Circulating lncRNA NEAT1 correlates with increased risk, elevated severity and unfavorable prognosis in sepsis patients. 2018, 36, 1659–1663. [CrossRef]

- Wen, M.; Cai, G.; Ye, J.; Liu, X.; Ding, H.; Zeng, H. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals the alteration of peripheral blood mononuclear cells driven by sepsis. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 125–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.R.; Abdelaleem, O.O.; Ahmed, F.A.; Abdelaziz, A.A.; Hussein, H.A.; Eid, H.M.; Kamal, M.; Ezzat, M.A.; Ali, M.A. Expression of lncRNAs NEAT1 and lnc-DC in Serum From Patients With Behçet’s Disease Can Be Used as Predictors of Disease. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 8, 797689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; et al. Association of long non-coding RNAs NEAT1, and MALAT1 expression and pathogenesis of Behçet’s disease among Egyptian patients. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 29, 103344 (2022).

- Hamdy, S.M.; Ali, M.S.; El-Hmid, R.G.A.; Abdelghaffar, N.K.; Abdelaleem, O.O. Role of Long non Coding RNAs, NEAT1 and Lnc-DC Expression in Pediatric Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura. Rep. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2023, 11, 635–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghpour, S.; Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Mazdeh, M.; Nicknafs, F.; Nazer, N.; Sayad, A.; Taheri, M. Over-Expression of Immune-Related lncRNAs in Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathies. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 71, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.-R.; Huang, C.-C.; Tu, S.-J.; Wang, G.-J.; Lai, P.-C.; Lee, Y.-T.; Yen, J.-C.; Chang, Y.-S.; Chang, J.-G. Dysregulation of Immune Cell Subpopulations in Atypical Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y. et al. NEAT1 involves Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) progression via regulation of glycolysis and P-tau. bioRxiv (2019). [CrossRef]

- Ballonová, L.; Souček, P.; Slanina, P.; Réblová, K.; Zapletal, O.; Vlková, M.; Hakl, R.; Bíly, V.; Grombiříková, H.; Svobodová, E.; et al. Myeloid lineage cells evince distinct steady-state level of certain gene groups in dependence on hereditary angioedema severity. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1123914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, O.J.; Lei, W.; Zhu, G.; Ren, Z.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, C.; Zhang, H.; Cai, J.; Luo, Z.; Gao, L.; et al. Multidimensional single-cell analysis of human peripheral blood reveals characteristic features of the immune system landscape in aging and frailty. Nat. Aging 2022, 2, 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hou, W.; Chen, F.; Mo, Y.-Y.; Zhang, Z. Landscape of tumoral ecosystem for enhanced anti-PD-1 immunotherapy by gut Akkermansia muciniphila. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 114306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.; Wang, C.; Vagts, C.; Raguveer, V.; Finn, P.W.; Perkins, D.L. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) NEAT1 and MALAT1 are differentially expressed in severe COVID-19 patients: An integrated single-cell analysis. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0261242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, A.C.; Adamoski, D.; Genelhould, G.; Zhen, F.; Yamaguto, G.E.; Araujo-Souza, P.S.; Nogueira, M.B.; Raboni, S.M.; Bonatto, A.C.; Gradia, D.F.; et al. NEAT1 and MALAT1 are highly expressed in saliva and nasopharyngeal swab samples of COVID-19 patients. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 2021, 36, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahni, Z.; et al. Long non-coding RNAs ANRIL, THRIL, and NEAT1 as potential circulating biomarkers of SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease severity. Virus Res. 336, 199214 (2023).

- Ali, M. A.; et al. Peripheral lncRNA NEAT-1, miR374b-5p, and IL6 panel to guide in COVID-19 patients’ diagnosis and prognosis. PLoS One 19, e0313042 (2024).

- Ni, X.; Su, Q.; Xia, W.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, K.; Su, Z.; Li, G. Knockdown lncRNA NEAT1 regulates the activation of microglia and reduces AKT signaling and neuronal apoptosis after cerebral ischemic reperfusion. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Jiang, C.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Zhao, L.; Yun, H.; Xu, W.; Fan, W.; Liu, Q.; Dong, H. Serum-derived exosomes containing NEAT1 promote the occurrence of rheumatoid arthritis through regulation of miR-144-3p/ROCK2 axis. Ther. Adv. Chronic Dis. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Shi, H.; Yu, C.; Fu, J.; Chen, C.; Wu, S.; Zhan, T.; Wang, B.; Zheng, L. LncRNA Neat1 positively regulates MAPK signaling and is involved in the pathogenesis of Sjögren's syndrome. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2020, 88, 106992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.; Ou, W.; Wei, B.; Fan, H.; Wei, C.; Fang, D.; Li, G.; Liu, W.; Liu, J.; Jin, L.; et al. Transcriptome-Wide Analysis to Identify the Inflammatory Role of lncRNA Neat1 in Experimental Ischemic Stroke. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, ume 14, 2667–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; et al. Construction of lncRNA-mediated ceRNA network for investigating immune pathogenesis of ischemic stroke. Mol. Neurobiol. 58, 4758–4769 (2021).

- Montero, J.J.; Trozzo, R.; Sugden, M.; Öllinger, R.; Belka, A.; Zhigalova, E.; Waetzig, P.; Engleitner, T.; Schmidt-Supprian, M.; Saur, D.; et al. Genome-scale pan-cancer interrogation of lncRNA dependencies using CasRx. Nat. Methods 2024, 21, 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wessels, H.-H.; Méndez-Mancilla, A.; Guo, X.; Legut, M.; Daniloski, Z.; Sanjana, N.E. Massively parallel Cas13 screens reveal principles for guide RNA design. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disease type | NEAT1 expression | Mechanisms | References (Ref) |

| Hantaan virus (HTNV) | Upregulated | NEAT1 activates inflammatory macrophages through Srebp2 | Ref: [25] |

| Influenza | Upregulated | NEAT1 induces transcription of IL8 | Ref: [21] |

| Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) | N/A | NEAT1 activates the innate immune response through HDP-RNP complex | Ref: [27] |

| Peritonitis and pneumonia | N/A | NEAT1 activates NLRP3, NLRC4 and AIM2 inflammasomes | Ref: [28] |

| Fibrosis | N/A | NEAT1 represses fibrosis through interacting with Rbm7 | Ref: [30] |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) | N/A | Knockdown of NEAT1 promotes macrophage M2 | Ref: [31] |

| Atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction (MI) | Downregulated | NEAT1 regulate the generation of tolerogenic DCs and CD4+ T cell balance | Ref: [32,35] |

| Hepatitis B virus (HBV) | Downregulated | N/A | Ref: [33] |

| Human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) | Upregulated | N/A | Ref: [36,37,38,39] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) | Upregulated | NEAT1 promotes CD4+ T cells differentiating into Th17 cells | Ref: [40,69] |

| Sepsis | Upregulated | NEAT1 induces MCEMP1 by sponging miR-125 | Ref: [41,52,53,54] |

| Coronary heart disease (CHD) | Upregulated | NEAT1 promotes CD4+ T cells differentiating into Th17 cells | Ref: [42] |

| Allergic rhinitis (AR) | Upregulated | NEAT1 regulates Th1/Th2 balance | Ref: [43] |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) | Upregulated | NEAT1 promotes Th2 cell activation through STAT6 | Ref: [46] |

| Asthma | Upregulated | NEAT1 promotes Th2 cell activation | Ref: [44] |

| Autoimmune uveitis (AU) | Upregulated | NEAT1 promotes CD4+ T cells differentiating into Th17 cells | Ref: [47,48] |

| Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia (WM) | Upregulated | N/A | Ref: [49] |

| SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) | Upregulated | N/A | Ref: [50,64,65,66,67] |

| Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) | Upregulated | N/A | Ref: [51,71,72] |

| Behҫet’s disease (BD) | Upregulated | N/A | Ref: [55,56] |

| Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) | Upregulated | N/A | Ref: [57] |

| acute/chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathies (AIDP/CIDP) | Upregulated | N/A | Ref: [58] |

| Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome (aHUS) | Upregulated | N/A | Ref: [59] |

| Alzheimer’s disease (AD) | Upregulated | N/A | Ref: [60] |

| Hereditary angioedema (HAE) | Upregulated | N/A | Ref: [61] |

| Ischaemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury | Upregulated | N/A | Ref: [68] |

| Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) | Upregulated | N/A | Ref: [70] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).