1. Introduction

Human population will rise to 9.6 billion from 7.2 billion by 2050 [

1]. This is a 33 increase in population, but as the standard of living improves worldwide, demand for ranch products will expand by around 70 over the same time [

2]. In the meantime, overall world cultivated land area has remained constant since 1991 [

3]. Indicating heightened productivity and sweats towards intensification. Livestock Effects are a significant agrarian product for transnational food security since they supply 17 of global kilocalorie input and 33 of global protein input [

4]. The livestock assiduity supports the livelihoods of the world's one billion poorest people and provides employment for nearly 1.1 billion individualities [

5]. There's an adding need for livestock products, and its quick increase in developing nations has been labelled as the" livestock revolution" [

6]. Global meat product is prognosticated to double from 258 to 455 million tonnes by 2050, while milk product is prognosticated to rise from 664 million tonnes in 2006 to 1077 million tonnes [

7]. Climate change, competition for water and land, and food security are likely to have a negative impact on livestock product at a time when it's utmost demanded [

6]. Climate change encyclopaedically is substantially due to the emigration of hothouse feasts (GHGs) that lead to atmospheric warming [

8]. The livestock assiduity contributes 14.5 to total GHG emigrations [

9], and thus could add land declination, water and air pollution, and loss of biodiversity [

10]. coincidently, climate change will impact livestock product through natural resource competition, quality and volume of feeds, livestock complaint, heat stress and loss of biodiversity while the demand for livestock products is projected to rise by 100 by medial of the 21st century [

11]. Hence, the issue lies in achieving a balance between productivity, domestic food security, and environmental conservation [

12].

Understanding how climate change and agrarian product interact is getting more and more important, and this is driving a lot of exploration [

13]. exploration on how climate change affects livestock product is still scarce [

14]. This essay examines how the livestock assiduity contributes to climate change as well as how it affects food security and livestock product. The objectives are to 1. Examine how Bihar's livestock husbandry is affected by climate change; 2. Determine Climate-flexible Livestock husbandry ways; 3. Assess Research and inventions in Technology; 4. Emphasis on Sustainable husbandry styles; and 5. Calculate the Implicit Benefits of Climate Resilience

2. Impact of Climate Change on Livestock Production

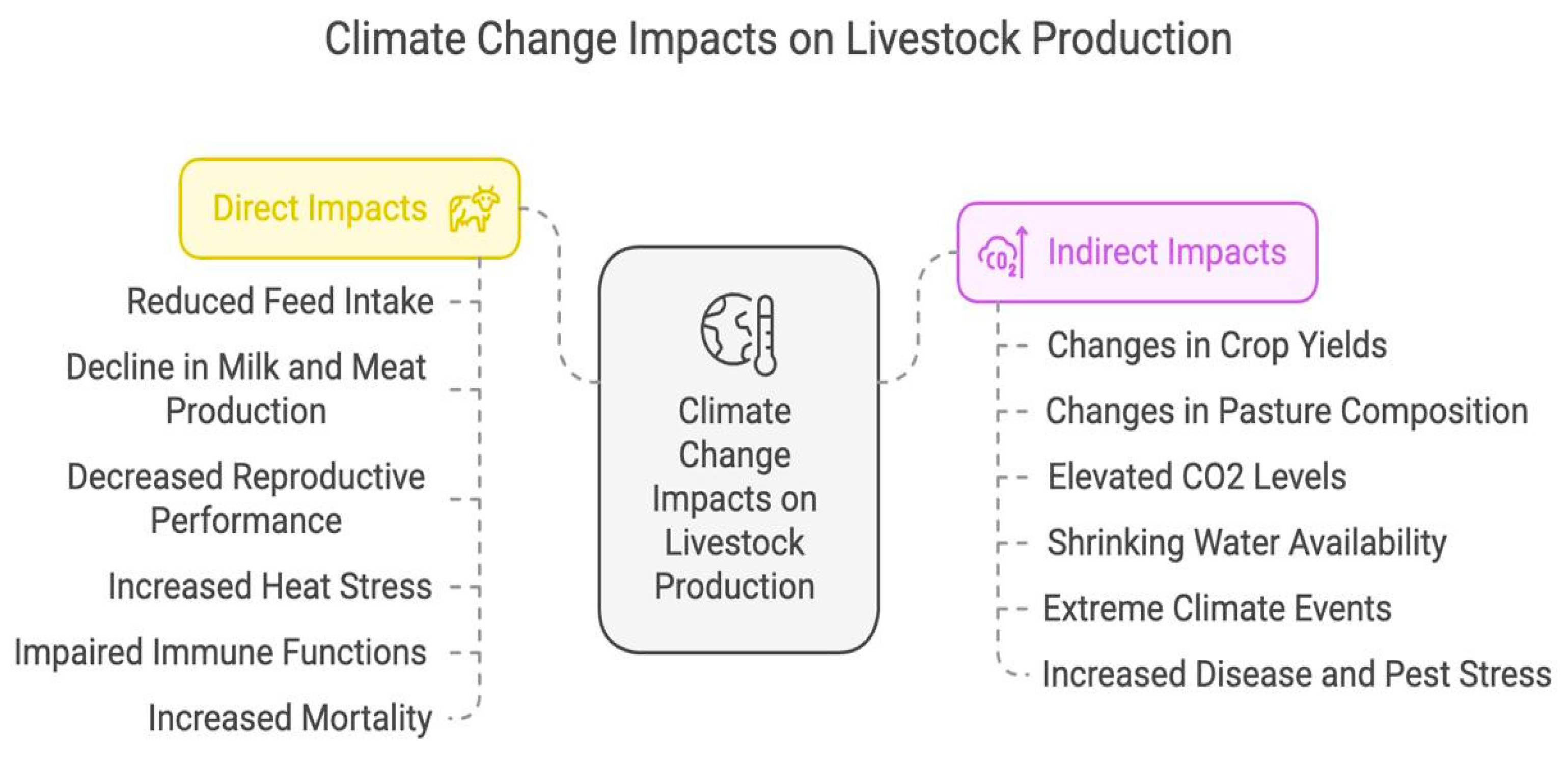

Advanced temperatures, further shifting rush, and more frequent axes are all signs of a changing climate. Growing situations of carbon dioxide (CO2) are the cause of this. It has been discovered that these variations affect the product of livestock and affiliated feed. We will go with Collier [

15] and generally classify the Effects as either direct or circular the term" direct Effects" describes how the climate and CO2 affect the product, metabolism, vulnerable system, and thermoregulation of livestock. circular Effects affect from how the climate affects pest/ pathogen populations, water vacuity, and feed product. A terse overview of the Effects can be set up in

Figure 1. The effects are also explained in further detail below.

2.1. Direct Effects

The primary climatic factor impacting livestock product is the temperature. Air movement, moisture, and temperature all play a part in this [

16]. The thermal comfort zone is the term used to describe the relationship that characterizes the optimal conditions of these. creatures perform at their stylish and use the least quantum of energy in this zone [

17]. Above this point, product processes come less effective and more energy is demanded to maintain thermoregulation [

18]. When the ambient temperature fluctuates beyond the thermal comfort zone, creatures experience thermal stress. adaptation is the term used to describe a livestock's phenotypic response to a specific source of stress [

19]. Compared to cold stress, heat stress is more dangerous and has a bigger impact [

20]. also, it's largely likely that climate change is raising temperatures, which in turn is causing further heat stress and lower cold wave stress. As a result, when agitating thermal stress, heat stress has taken center stage. Livestock have been shown to suffer from heat stress. Heat stress is allowed to bring the US livestock assiduity between

$ 1.7 and

$ 2.4 billion annually [

21]. When creatures are unfit to expel enough heat to maintain homeothermy, heat stress results [

22]. It has been discovered that this results in elevated body temperatures as well as elevated palpitation, heart rate, and respiration [

23]. In return, this can lead to dropped feed input, milk yield, and reduplication effectiveness, and to differences in Humanity and vulnerable function. These Effects are outlined in further detail below with a focus on livestock performance rather than on underpinning biology.

2.1.1. Feed Intake

High ambient temperatures can beget a variety of responses, including dropped feed input. Reduced reflection, gut motility, and appetite are all symptoms of increased heat stress in ruminants [

24]. The feed input of lactating dairy cows decreases as the outside temperature rises above 25 – 26 °C, and the declines more snappily above 30 °C [

25]. Other ruminants are more vulnerable to heat stress than scapegoats. still, when the outside temperature rises above their thermal comfort zone by further than 10 °C, they reduce the quantum of feed they freely consume [

26].

When temperatures rise from 20 to 35 °C, swillers under heat stress show elevated body temperatures and a 10.9 drop in feed input [

27]. These Effects last after the swillers have been subordinated to heat stress. thus, it's hypothecated that feeding beforehand in the morning may help dropped feed input [

28]. also, flesh creatures that are exposed to high temperatures show dropped feed input. It has been discovered that catcalls from the post-hatch period to 6 weeks of age reduce their feed input by 9.5 when the ambient temperature rises from 21.1 to 32.2 °C [

29]. Both diurnal weight gain and feed conversion effectiveness are lowered when feed input is reduced [

30]. More astronomically, reduced feed input brought on by heat stress results in lower product of milk, meat, and eggs across all livestock types, which further reduces sectoral losses.

2.1.2. Livestock Product Milk and Others

According to studies, the dairy assiduity gests advanced profitable losses from heat stress than the other livestock diligence in the United States [

21]. Dairy cows under heat stress consume lower dry matter from their feed, which accounts for about 35 of the drops in milk product [

31]. Again, the most productive types of dairy cows are more susceptible to heat stress because they're larger and release further metabolic heat than lower- producing types [

32]. Accordingly, as metabolic heat product from heat stress rises, milk product falls [

25]. surroundings that are hot and sticky have an impact on milk composition in addition to milk product. According to Gorniak [

33] and Ravagnolo et al., [

34] lactating cows begin to witness heat stress when the temperature- moisture indicator reaches 72. After this, the quantum of protein and fat in their milk decreases as the indicator rises. Dairy scapegoats [

35] and buffaloes [

36] have also been set up to parade analogous changes in milk composition, although these studies have been limited. Heat stress has been shown to have an impact on meat product for all of the main marketable livestock species [

37]. Ruminants under heat stress have lower bodies, lower corpse weights, thinner fat, and lower- quality meat [

38]. It has been discovered that small ruminants like lamb and scapegoats are more suited to hot, sticky climates [

39]. still, because they're raised with further exposure to rough radiant shells and fed high- energy diets, pasture cattle have been set up to be more susceptible [

37]. As with ruminants, swillers that are exposed to high temperatures show dropped corpse weight and meat quality [

40]. In comparison to thermoneutral creatures, they've also been set up to show a lower average diurnal gain of 9.8 in high ambient temperatures [

41].

2.1.3. Reproduction

Both relations' capability to reproduce is impacted by heat stress. Heat stress increases the threat of anoestrous and embryonic death in ladies while dwindling the estrous period and fertility. Males witness diminishments in the quantum of rich sperm, testicular volume, and semen quality. There have been reports of notable seasonal variations in both relations' reproductive performance [

42]. Despite the fact that heat stress also affects flesh reduplication, catcalls may perform else than mammals. Compared to womanish cookers, manly cookers are said to be more susceptible to heat- related gravidity [

43]. Environmental stress may affect hatchability, lower thraldom quality, and delay the ovulation process in layers [

44].

2.1.4. Disease and Parasite Stress

Climate change has an impact on livestock health due to a variety of factors, similar as species, strain, position, complaint characteristics, and livestock vulnerability [

45]. creatures' primary defense against environmental stressors and other dangerous cuts is their vulnerable system [

46]. Heat stress can vitiate humoral and cell- intermediated vulnerable responses [

47]. Because of this, hot rainfall can make livestock more susceptible to ails and increase the frequence of some conditions (like mastitis), adding the threat of morbidity and death [

48]. likewise, heat stress may impact livestock health via fresh functional pathways. For case, if growing swillers are exposed to violent heat for many hours, they may sustain intestinal injuries [

49]. Under heat stress, changes in intestinal microbiota have also been observed in cookers and laying hens [

50]. Coincidently, rising temperatures and changed rush patterns could quicken the spread of spongers and infections. Since it's generally bandied in relation to livestock health, the impact of pathogens and spongers on livestock is covered in this section indeed though it's generally allowed of as a circular effect. This would introduce new conditions and have an impact on the cornucopia and distribution of vector- borne pests [

45]. These could raise the threat of morbidity and Humanity as well as the corresponding fiscal loss [

51]. Because of the nature of the complaint and changes brought about by climate change, the impact of climate change on livestock complaint is more delicate to estimate and read than other impacts. In developing nations, this kind of impact assessment is indeed more delicate [

45].

2.1.5. Mortality

One major effect of heat stress that has a large fiscal cost is Humanity. fresh heat stress raises Humanity rates, according to exploration on dairy cows and swillers [

52]. It has been demonstrated that hot and sticky rainfall poses a lesser trouble to cows and swillers' lives than hot but dry rainfall, with temperatures above 37.7 °C and moisture situations above 50 being particularly dangerous [

53]. Compared to mammals, flesh generally has advanced and further shifting body temperatures, and they're more susceptible to temperature increases. Up to 27 °C ambient temperature or a body temperature of 41 °C, cravens can operate typically; still, a 4 °C increase in body temperature would be fatal to them [

54].

2.2. Indirect Effects

Grain/ oilseed crop products and recons make up the maturity of livestock feed. Climate has an impact on the product of those Effects as well as water inventories, including soil humidity and irrigation. As a result, climate change has a circular impact, primarily on the water and feed force. There's a vast quantum of literature on how crop product is affected by climate change; we are not trying to cover all of the specifics of this field of study then [

55]. When it comes to producing livestock simply, crops and forages force the feedstocks that the creatures eat. In this sense, the force of livestock feed is impacted by climate change; still, the extent of this impact on livestock product, although constantly bandied, has not been assessed singly. In the rest of this section, we address the broad outlines of this discussion.

2.2.1. Forage Quality

Weight gain, productivity, and reduplication all depend on acceptable nutrition, and probe is a vital part of ruminant diets. It takes balance to give creatures with the right feed because livestock species have different nutritive requirements and probe quality varies extensively within and between probe crops. Insipidity, nutritive value, voluntary input, and the impact of anti-quality factors have been the main motifs of the maturity of probe- quality studies [

56]. further energy is handed per unit of dry matter (DM) consumed by recons with advanced insipidity. Minerals like calcium (Ca), phosphorus (P), magnesium (Mg), and potassium (K) are among the nutrients generally reported by probe analysis, along with neutral soap fibre (NDF), acid soap fibre (ADF), and crude protein (CP) [

57]. Climate can have an impact on quality by causing changes in the attention of nitrogen and water-answerable carbohydrates due to dry conditions and rising temperatures [

58]. Advanced CO2 situations can also lead to an increase in non-structural carbohydrates, which can ameliorate the quality of forage [

59]. Quality could also decline, however, as rising temperatures can beget factory apkins to contain further lignin, which lowers insipidity [

60].

2.2.2. Water

Worldwide, there's a deficit of water, and the extent of this deficit is determined by the rate of force to demand. With 69 of fresh water recessions, husbandry is the single biggest stoner of water worldwide [

61]. Water failure will presumably come a more significant limitation on product husbandry as Human populations, inflows, and the demand for livestock products rise. Water is used in the livestock assiduity for product processing, feed crop civilization, and livestock consumption [

45]. It's responsible for roughly 41 of all consumptive water use and 22 of all evapotranspiration (ET) from agrarian land worldwide [

62]. Water vacuity and consumption in livestock product are anticipated to change as a result of climate change [

63]. Water consumption by creatures and irrigation water use per land area are anticipated to rise as temperatures rise. Another issue is ocean position rise- convinced water salinization [

64]. In order to address the issue of water failure, more effective product systems are demanded as competition for water between livestock, crops, and non-agricultural uses increase over the coming many decades [

65].

2.2.3. Extreme Climate Events and Seasonal Variation

Climate change may have fresh Effects on livestock product by changing the seasonal pattern and variability of crop yield and resource vacuity. creatures will witness further heat stress as heat swells do more constantly and last longer [

52]. According to Knee et al., [

66] there are notable seasonal variations in the quantum of glycogen in cattle muscle. They also discovered that superior beef quality in the spring is associated with nutrient-rich and generous ranges, while poorer ranges are associated with lower beef quality in the summer. likewise, differences in the seasonal patterns of probe vacuity may present new difficulties for livestock and grazing operation [

67]. Probe volume is hovered by an adding threat of extreme failure, and adaption measures are demanded to deal with similar extreme circumstances [

68]. likewise, variations in the timing of snowmelt impact feed inventories by changing the patterns of water vacuity throughout the time [

69].

3. Climatic Factors Affecting Livestock

Solar radiation, temperature, and moisture are the main environmental factors that beget heat stress in creatures. Again, solar radiation is affected by loss of the ozone subcaste and photoperiod. still, downfall and wind speed lessen these effects [

70]. The two main factors that beget heat stress are temperature and relative moisture, which are constantly combined to produce a thermal heat indicator (THI) [

71]. The following are some of the climate factors that impact livestock.

3.1. Extreme Temperature and Heat Stress

Variations in temperature that fall outside of the ideal range for creatures can have a serious impact on their physiological processes. creatures are homeotherms, meaning their body temperature stays constant. creatures' physiology is disturbed by exposure to extreme temperatures, particularly violent heat, which has an impact on both reduplication and productivity. Global warming is one of the growing worries about the slow rise in temperatures.

3.2. Humidity

The stress position rises when high temperatures and moisture are combined. creatures use evaporative cooling to fight heat stress because moisture prevents them from sweating and panting. This is why creatures' stress situations are measured by combining temperature and moisture.

3.3. Drought and Nutritional Scarcities

Livestock are significantly impacted by failure and salutary scarcities brought on by climate change because they limit probe growth and drop water vacuity. Water failure reduces grassland, makes growers use expensive or crummy feed backups, and causes dehumidification, heat stress, and dropped livestock productivity. creatures with poor nutrition have slower growth rates, weaker vulnerable systems, and poorer reproductive capabilities. likewise, patient failure can harm land, lowering its eventuality for unborn grazing and performing in overgrazing.

3.4. Environmental Impurity

Climate change- aggravated environmental pollution has a major effect on livestock by deteriorating vital coffers that are necessary for their productivity and well- being. Livestock conditions, respiratory problems, and poisonous exposure are caused by pollution from artificial waste, agrarian runoff, and air adulterants. also, this impurity lowers the probe's nutritive value and exposes creatures to dangerous chemicals that may make up in their bodies. creatures suffer from compromised vulnerable systems, reduced reproductive effectiveness, and heightened vulnerability to illness as a result [

72].

3.5. Heat Waves and Global Warming

While some climate changes, like global warming, are formerly underway, numerous others are gradational and may not manifest their Effects for hundreds or thousands of times [

73]. It's generally known that the primary cause of this temperature increase is Human exertion- convinced hothouse gas emigrations. It's intriguing to note that the warming over land is lesser and that the Effects vary throughout the world. Increased frequence of hot days, reduced snow and ice face cover, and rising ocean situations are just a many of the observable and quantifiable Effects of global warming [

74]. Until some significant action is taken, these Effects will have a significant and long- continuing impact on the agrarian sector, which includes livestock. The lack of mindfulness among the general public, including those who enjoy livestock, regarding global warming and its Effects on productivity is concerning. Despite the fact that the consequences of global warming are formerly apparent and will only worsen in the future, Human exertion can still lessen them.

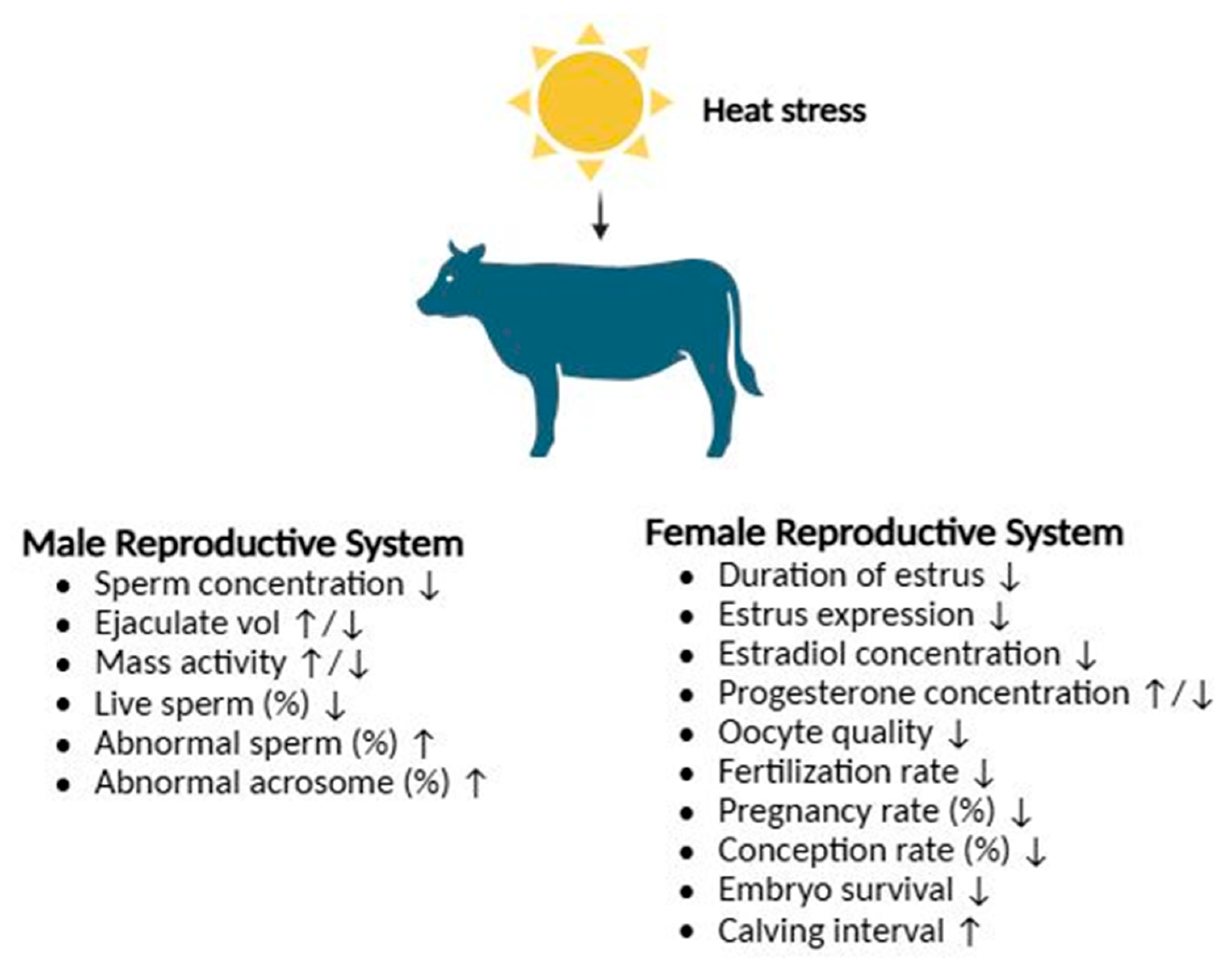

3.6. Reproductive Physiology Affected by Climate Change

When creatures are exposed to hot, muggy conditions and are unfit to acclimate well, heat stress results. Lower feed input, milk product, and other physiological responses to control body temperature are overfilled. Heat stress has a more profound and long- continuing effect on reduplication because it alters the hypothalamic- hypophyseal- gonadal (HPG) axis [

75]. As a result, for weeks or months following the launch of stress, the creatures' fertility may be impacted.

Figure 2 shows how heat stress affects both manly and womanish creatures' reproductive systems overall. Heat stress decreases the named follicle's degree of dominance in ladies and lowers the granulosa and theca's steroidogenic exertion. cells, causing the blood's position of estradiol to drop. Tube progesterone situations can rise or fall depending on the livestock's metabolic condition and the type of heat stress (acute or habitual) [

76]. The quality of oocytes and embryos declines as a result of these endocrine changes, which also alter the ovulatory medium and reduce follicular exertion. also, the uterine terrain is changed, which lowers the liability of embryo implantation.

4. Case Studies Climate flexible Livestock husbandry in Bihar

Here are some case studies pressing the Impacts of climate flexible livestock husbandry in Bihar.

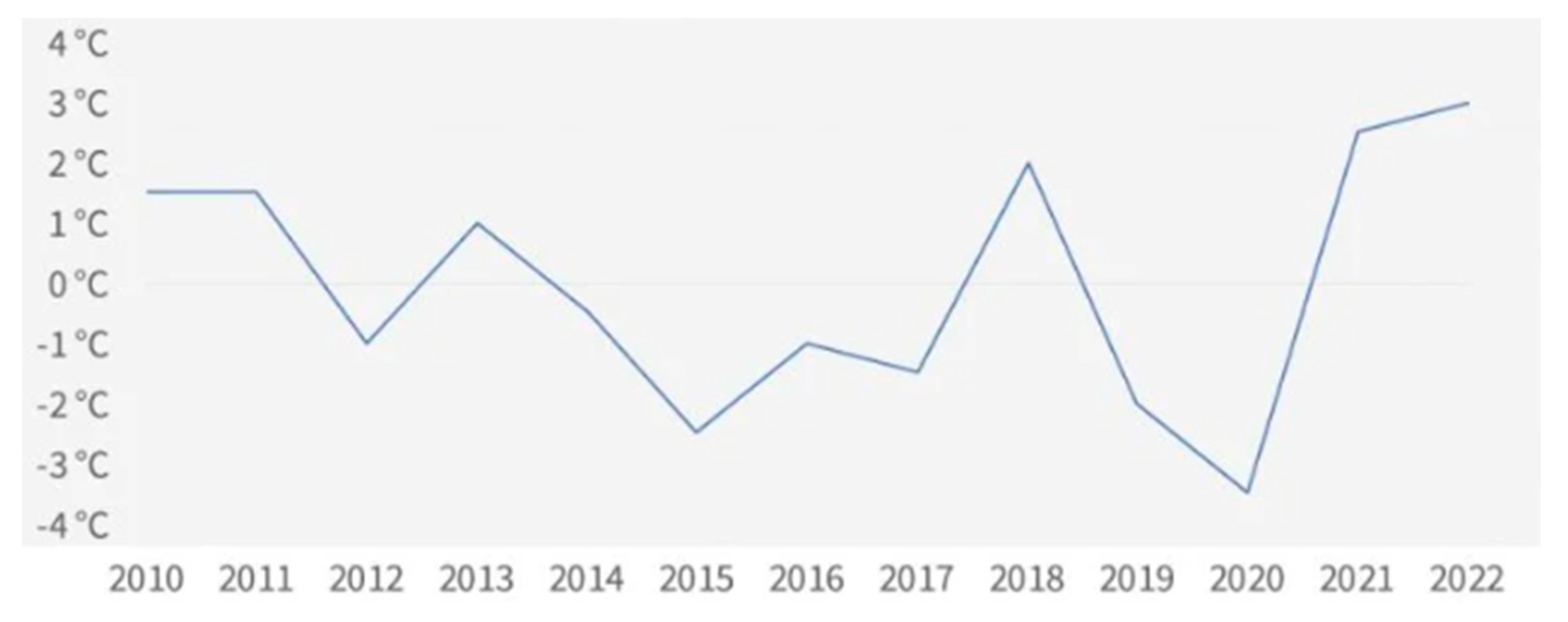

Case Study- 1: Growers in the Buxar quarter of Bihar find it delicate to acclimate to and deal with the shifting climate. growers' capability to acclimatize is undermined by notable periodic variations in temperature and downfall. The creation and facilitation of growers' adaption to climate change could be greatly backed by planter directors’ associations (FPOs), but they bear better impulses and backing." The largest threat in the future will be irregular water vacuity. The piedmont zone and swash lowlands are at threat from corrosion and sedimentation when the water force is advanced, while the highland face is at threat from salinization, desertification, and aquifer drying up when the water force is lower. The main issue will be a decline in food product. Between Varanasi and Patna, on the Ganges River's south bank, is the Buxar quarter. Unseasonal downfall and famines pose serious pitfalls to the quarter's agrarian affair. And these troubles are adding snappily. We're unfit to attribute these rainfall variations to anything other than the Effects of climate change. The ramifications for the Gangetic Plain in the preceding decades are extremely concerning if these are the first suggestions. We're doubtful of what to do because the rainfall is so changeable. We get no rain when we anticipate it, and also all of an unforeseen, we get so important that it washes down all of our crops. We're helpless, and this is only getting worse. After a poor crop, we're unfit to pay for the necessary fungicides and toxin. We've no choice but to buy these on credit.

A planter in Buxar who grows wheat and rice. The quarter's spring temperatures are rising, and the differences are widening.

Six of the former 13 times have seen a positive divagation in the diurnal mean temperature during the spring season (see

Figure 3).

The diurnal mean positive divagation has been lesser over the last two times than it has been in the history.

The quarter has endured severe heat swells in March for the last two times, which has caused the growing wheat to shrivel and, accordingly, dropped crop yields.

And second, compliances of the data from Buxar quarter in Tajpur village areas. The substantially growers facing the adverse impact of climate change in livestock husbandry. Due to the observation of one planter, whose name is Dhaneshwar Singh. He said that in the summer of last time, 2024, one buffalo maleficent, its body got so hot that it failed due to heat. He also said that it's injury by climate change.

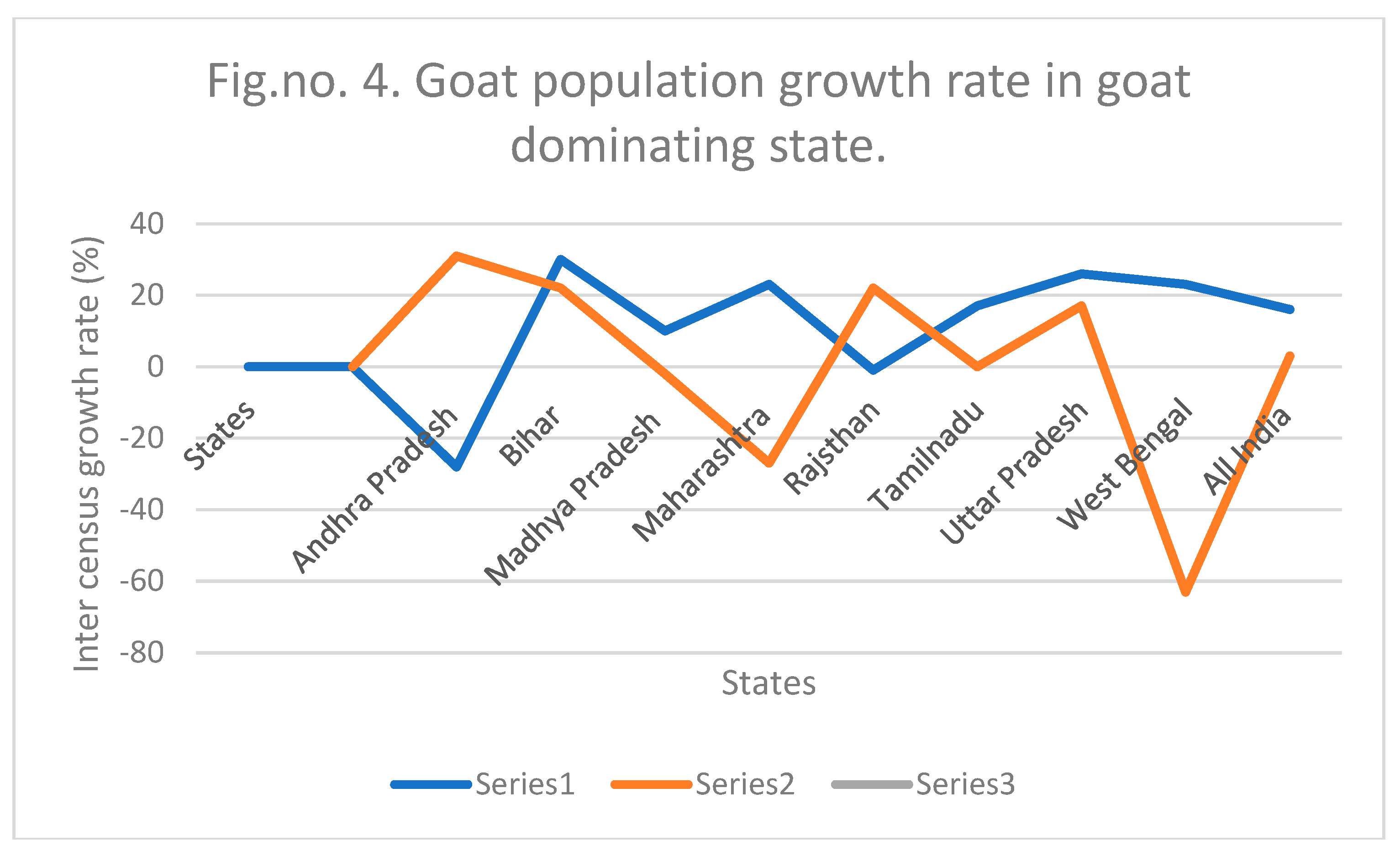

Case Study- 2: Goat husbandry under changing climate in Banka quarter, Bihar. There are 135.17 million scapegoats in India, making up 26.40 of all livestock and a 3.82 drop from the last tale conducted in 2007. The scapegoat population declined by 15.66 in civic areas and 3.18 in pastoral bones. According to the 2012 tale, there were 12.15 million scapegoats in Bihar, counting for 8.99 of India's total population and ranking third after Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh. It ranks second (19.54) in terms of scapegoat population growth, behind Assam (42.81). Between 2003 and 2012, the total number of womanish scapegoats in Bihar increased from 6.66 million to 8.63 million, a 28.38 increase [

87]. The comparatively advanced number of scapegoats indicates that further pastoral residers are interested in scapegoat husbandry, cube feeding, and increase reliance as a supplementary source of income and the high- yielding scapegoat strain that exists in Bihar.

In Bihar's Banka quarter, scapegoat husbandry is veritably common, and growers are exercising scientific operation ways and new technologies to combat climate stress in scapegoat product. Goat feeding practices may be altered as a result of changes in climate, similar as downfall, temperature, moisture, etc. Cube feeding rather than grazing or browsing, along with semi-unsustainable operation ways, will really reduce the overall fiscal loss to growers. sprat Humanity will also drop with effective health operation and prompt treatment.

5. Strategies for Mitigating Climate Stress

To lessen climate change, there are top- down (profitable-wide programs) and bottom- up (specific mitigation strategies) technologies available. and both have the capacity to neutralize or indeed reduce anticipated increases in global emigrations. The idea that certain agrarian practices could significantly increase soil carbon sinks at a low cost while also producing biomass feedstock for energy use is" medium" extensively accepted. Every sector can make a donation. perfecting crop and grazing land operation to increase soil carbon storehouse and perfecting livestock and ordure operation to reduce methane emigrations are exemplifications of mitigation strategies. Raising public mindfulness of the connections between the use of cattle products, health Effects, and environmental counteraccusations is commodity that environmental associations laboriously support. still, data shows that there's a strong demand for meat and milk products up to a consumption position of about 60 kg of meat and 100 kg of milk annually. Plainness of income. This implies that reducing consumption in developing countries would be gruelling because growing inflows generally lead to an increase in demand for these products. Encouraging manufacturers to come more environmentally conscious yields the stylish openings. There are significant benefits for growers, particularly youthful growers who are educating others about the possibility of further sustainable product styles. Using inheritable selection styles to boost the product capacity of specific domestic livestock species and types is a crucial future ideal for the product of livestock worldwide. thus, it's likely that the maturity of livestock produced in the future will come from private granges employing a request- acquainted approach. Large amounts of decoration livestock feed, similar as concentrates and fodder, will be demanded for this. Offering request- acquainted growers’ impulses to increase productivity and product quality, as well as granting them access to loans with longer grace ages and lower interest rates, will also quicken the growth of livestock affair [

78]. Livestock directors can directly apply a number of mitigation strategies, similar as operation ways, salutary strategies, hormone administration, supported reproductive technologies (ART), choosing heat-tolerant types, lowering hothouse gas emigrations from livestock sources, etc. Below is a brief discussion of these.

5.1. Housing Management

creatures under heat stress can always be less affected by better operation. It's important to take preventives to shield the creatures from the sun. How to use a chalet and casing system rightly. soddening the creatures or giving them a marshland can help them. After making physical changes, several studies have shown an increase in product and reduplication [

79].

5.2. Nutritive Strategies

It's among the most practical and snappily espoused strategies for reducing climate- related stressors. It consists of supplementation with vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and other nutrients in addition to a healthy diet. Minerals that increase a livestock's reproductive effectiveness include phosphorus, calcium, selenium, zinc, bobby, manganese, cobalt, iodine, potassium, and others [

80]. Vitamin A, vitamin E, and trace minerals like bobby, zinc, and selenium supplements enhance the health and impunity of the mammary glands, especially when they're under heat stress. The emphasis should be on giving the creatures more concentrated feed because there's a drop in feed input during heat stress. Other strategies to lower the creatures' metabolic heat product include feeding them proteins and fats that have been ruminantly protected [

81]. also, it's advised that the creatures be given unlimited access to water.

5.3. Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ART) and Hormonal Interventions

nutritive strategies the reproductive system's hormonal equilibrium is upset by heat stress. Hormonal remedy is salutary in numerous of the circumstances. GnRH, progesterone, PGF2, and other hormones can be used meetly to beget estrus in anestrus- producing creatures. The creatures may be conceived by timed artificial copulation (TAI) after estrus induction. The sov- synch protocol, co-synch protocol, mongrel- synch protocol, CIRD (Controlled Internal medicine Releasing), PRID (Progesterone Releasing Intravaginal Device), and other programs are applicable for hormonal treatment [

82]. Domestic creatures can have better reproductive success with supported reproductive technologies like timed artificial copulation (TAI), superovulation (SOV), ovum pick- up (OPU), in vitro embryo product (IVEP), and timed embryo transfer (TET).

5.4. Selection of Heat-Tolerant Breeds

Dairy creatures that have been widely bred for lesser milk product are now more vulnerable to environmental pressures. Native creatures are more flexible to heat stress than crosses or fantastic types. They've large body face areas, light- coloured fleeces, and an advanced capacity for sweating. It's thus advised that the proportion of fantastic blood be grounded on the climate zone and that the native milch types, similar as Gir, Sahiwal, Red Sindhi, and Tharparkar, be given lesser significance. Another way to get around this problem is to choose the creatures using inheritable labels.

5.5. Reduction of Livestock Greenhouse Gas Emigrations

The livestock assiduity is responsible for nearly 16.5 of the world's hothouse gas emigrations. 27 of its carbon dioxides. 44 methane and 29 nitrous oxides. They're all the result of colourful rudiments related to the product of livestock- grounded foods [

83]. According to a 2019 report by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), methane product from the livestock assiduity exceeded that of the petroleum and natural gas diligence combined. It makes the significance of lowering hothouse gas emigrations from this assiduity abundantly apparent. Some conduct that can be taken to lower hothouse gas emigrations from domestic creatures include adding reflection time, inheritable selection, and the addition of feed supplements (algae, bromoform, polyphenolic substances, essential canvases, flavonoids, etc.) [

84].

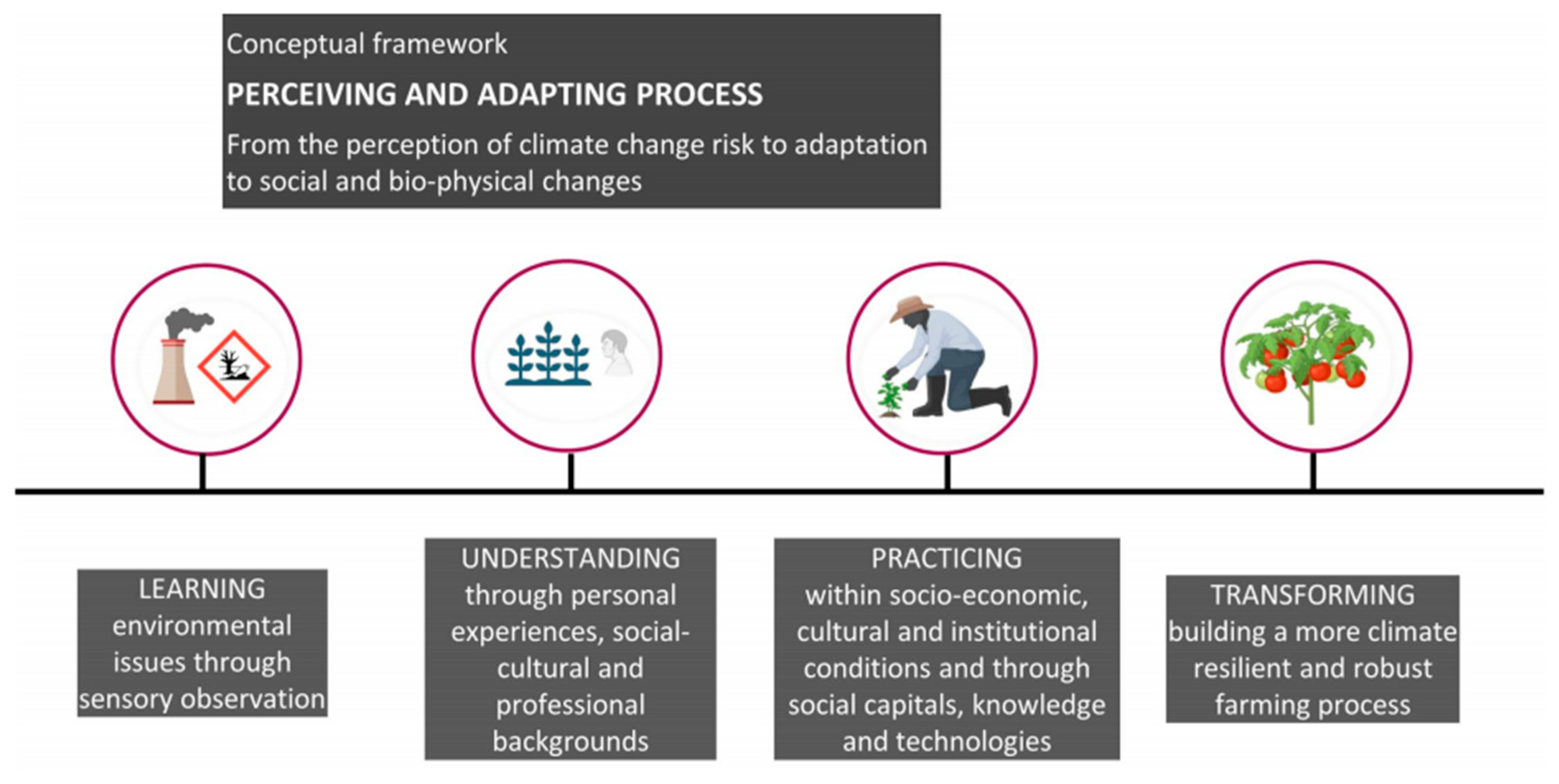

5.6. Climate Change Perceptions

Understanding people's shoes and being suitable to extend original adaption enterprise into other areas are both necessary for an effective response to climate change. global regulations.

" Knowledge shapes perception, and perception shapes knowledge." The original climate and rainfall vaticinations have a significant impact on tilling operations in the husbandry and livestock sectors. nevertheless, there's a lot of query girding growers' choices regarding ranch operation in light of climate change.

Figure 5.

The cognitive process is a theoretical frame for how people perceive and acclimate [

85].

Figure 5.

The cognitive process is a theoretical frame for how people perceive and acclimate [

85].

They've a unique perspective on the world and base their opinions on it, which constantly leads to poisoned maladaptation. thus, it's critical to comprehend the cognitive processes linked to comprehensions of climate change in order to combat this issue. The following are the phases into which this cognitive process is separated [

85].

i. The planter learns about the original environmental conditions through immediate observation in the first phase.

ii. The planter reaches the alternate stage once they comprehend the social, artistic, professional, and profitable environment of the region. They gain this knowledge by immediate experience in their line of work.

iii. During the third stage, the planter operates in a particular institutional, social, artistic, and socioeconomic environment.

Knowledge in wisdom, technology, and society acquired through institutional and particular connections improves this stage.

iv. The last stage is reached when decision- making procedures are effectively changed to come more robust and flexible to climate change.

The planter's capability to acclimatize and change is demonstrated in the final two phases, while the first two phases are devoted to adaption. So," perceiving to learn and to acclimatize" and" learning to perceive and to acclimatize" are essential factors of the climate change adaption process in order to achieve a sustainable ideal.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Effects of climate change, especially rising temperatures, heat stress, water failure, and changeable rainfall patterns, present serious challenges for Bihar's livestock husbandry assiduity. These issues have an impact on feed input, reduplication, and overall product effectiveness, as well as livestock productivity, health, and food security. still, some of the negative Effects of climate change can be lessened by enforcing climate- flexible strategies, similar as better casing operation, salutary adaptations, breeding heat-tolerant creatures, and water-effective practices. likewise, growers in Bihar ca not only acclimatize to but also prosper in the changing climate with the support of contemporary technologies and exploration, as well as the creation of sustainable and adaptive practices. The development of a further climate- flexible livestock assiduity will bear the backing of planter patron associations (FPOs), governmental regulations, and bettered original adaption ways. espousing these tactics will help Bihar maintain the sustainability and viability of its livestock husbandry sector, guarding unborn generations' livelihoods and food security. For livestock husbandry in Bihar to have a sustainable future and overcome the obstacles presented by climate change, further exploration, creativity, and cooperation at the original and public situations are essential.

References

- Nations, U. (2013). World population projected to reach 9.6 billion by 2050'. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Online.

- Pretty, J. , Sutherland, W. J., Ashby, J., Auburn, J., Baulcombe, D., Bell, M.,... & Pilgrim, S. (2010). The top 100 questions of importance to the future of global agriculture. International journal of agricultural sustainability, 8(4), 219-236. [CrossRef]

- O'Mara, F. P. (2012). The role of grasslands in food security and climate change. Annals of botany, 110(6), 1263-1270. [CrossRef]

- Rosegrant, M. W. , Fernández, M. A. R. I. A., Sinha, A. N. U. S. H. R. E. E., Alder, J. A. C. K. I. E., Ahammad, H., Fraiture, C. D.,... & Yana-Shapiro, H. (2009). Looking into the future for agriculture and AKST.

- Hurst, P. , Termine, P., & Karl, M. (2005). Agricultural workers and their contribution to sustainable agriculture and rural development.

- Thornton, P. K. (2010). Livestock production: recent trends, future prospects. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 365(1554), 2853-2867.

- Alexandratos, N. , & Bruinsma, J. (2012). World agriculture towards 2030/2050: the 2012 revision.

- Solomon, S. (Ed.). (2007). Climate change 2007-the physical science basis: Working group I contribution to the fourth assessment report of the IPCC (Vol. 4). Cambridge university press.

- Gerber, P. J., Steinfeld, H., Henderson, B., Mottet, A., Opio, C., Dijkman, J., ... & Tempio, G. (2013). Tackling climate change through livestock: a global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities (pp. xxi+-115).

- Bellarby, J., Tirado, R., Leip, A., Weiss, F., Lesschen, J. P., & Smith, P. (2013). Livestock greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation potential in Europe. Global change biology, 19(1), 3-18.

- Garnett, T. (2009). Livestock-related greenhouse gas emissions: impacts and options for policy makers. Environmental science & policy, 12(4), 491-503.

- Wright, I. A., Tarawali, S., Blümmel, M., Gerard, B., Teufel, N., & Herrero, M. (2012). Integrating crops and livestock in subtropical agricultural systems. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 92(5), 1010-1015.

- Aydinalp, C., & Cresser, M. S. (2008). The effects of global climate change on agriculture. American-Eurasian Journal of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences, 3(5), 672-676.

- Field, C. B., & Barros, V. R. (Eds.). (2014). Climate change 2014–Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability: Regional aspects. Cambridge University Press.

- Collier, R. J., Baumgard, L. H., Zimbelman, R. B., & Xiao, Y. (2019). Heat stress: physiology of acclimation and adaptation. Animal Frontiers, 9(1), 12-19.

- Ames, D. (1980). Thermal environment affects production efficiency of livestock. BioScience, 30(7), 457-460.

- Nardone, A., Ronchi, B., Lacetera, N., & Bernabucci, U. (2006). Climatic effects on productive traits in livestock. Veterinary Research Communications, 30, 75.

- Bianca, W. (1976). The signifiance of meteorology in animal production. International Journal of biometeorology, 20, 139-156.

- Nardone, A., Ronchi, B., Lacetera, N., Ranieri, M. S., & Bernabucci, U. (2010). Effects of climate changes on animal production and sustainability of livestock systems. Livestock Science, 130(1-3), 57-69.

- Collier, R. J., Beede, D. K., Thatcher, W. W., Israel, L. A., & Wilcox, C. J. (1982). Influences of environment and its modification on dairy animal health and production. Journal of dairy science, 65(11), 2213-2227.

- St-Pierre, N. R., Cobanov, B., & Schnitkey, G. (2003). Economic losses from heat stress by US livestock industries. Journal of dairy science, 86, E52-E77.

- Daramola, J. O., Abioja, M. O., & Onagbesan, O. M. (2012). Heat stress impact on livestock production. Environmental stress and amelioration in livestock production, 53-73.

- Rashamol, V.P.; Sejian, V.; Bagath, M.; Krishnan, G.; Archana, P.R.; Bhatta, R. Physiological Adaptability of Livestock to Heat Stress: An Updated Review. Periodikos. 2018. Available online: http://www.jabbnet.com/journal/jabbnet/article/doi/10.31893/2318-1265jabb.v6n3p62-71.

- Yadav, B., Singh, G., Verma, A. K., Dutta, N., & Sejian, V. (2013). Impact of heat stress on rumen functions. Veterinary World, 6(12), 992.

- Kadzere, C. T., Murphy, M. R., Silanikove, N., & Maltz, E. (2002). Heat stress in lactating dairy cows: a review. Livestock production science, 77(1), 59-91.

- Lu, C. D. (1989). Effects of heat stress on goat production. Small Ruminant Research, 2(2), 151-162.

- Lopez, J., Jesse, G. W., Becker, B. A., & Ellersieck, M. R. (1991). Effects of temperature on the performance of finishing swine: I. Effects of a hot, diurnal temperature on average daily gain, feed intake, and feed efficiency. Journal of Animal Science, 69(5), 1843-1849.

- Cervantes, M., Antoine, D., Valle, J. A., Vásquez, N., Camacho, R. L., Bernal, H., & Morales, A. (2018). Effect of feed intake level on the body temperature of pigs exposed to heat stress conditions. Journal of Thermal Biology, 76, 1-7.

- Syafwan, S., Kwakkel, R. P., & Verstegen, M. W. A. (2011). Heat stress and feeding strategies in meat-type chickens. World's Poultry Science Journal, 67(4), 653-674.

- Parkhurst, C., & Mountney, G. J. (2012). Poultry meat and egg production. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Rhoads, M. L., Rhoads, R. P., VanBaale, M. J., Collier, R. J., Sanders, S. R., Weber, W. J., ... & Baumgard, L. H. (2009). Effects of heat stress and plane of nutrition on lactating Holstein cows: I. Production, metabolism, and aspects of circulating somatotropin. Journal of dairy science, 92(5), 1986-1997. [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Downing, M. M., Nejadhashemi, A. P., Harrigan, T., & Woznicki, S. A. (2017). Climate change and livestock: Impacts, adaptation, and mitigation. Climate risk management, 16, 145-163.

- Gorniak, T., Meyer, U., Südekum, K. H., & Dänicke, S. (2014). Impact of mild heat stress on dry matter intake, milk yield and milk composition in mid-lactation Holstein dairy cows in a temperate climate. Archives of animal nutrition, 68(5), 358-369.

- Ravagnolo, O., Misztal, I., & Hoogenboom, G. (2000). Genetic component of heat stress in dairy cattle, development of heat index function. Journal of dairy science, 83(9), 2120-2125.

- Salama, A. A., Contreras-Jodar, A., Love, S., Mehaba, N., Such, X., & Caja, G. (2020). Milk yield, milk composition, and milk metabolomics of dairy goats intramammary-challenged with lipopolysaccharide under heat stress conditions. Scientific reports, 10(1), 5055.

- Seerapu, S. R., Kancharana, A. R., Chappidi, V. S., & Bandi, E. R. (2015). Effect of microclimate alteration on milk production and composition in Murrah buffaloes. Veterinary world, 8(12), 1444.

- Gonzalez-Rivas, P. A., Chauhan, S. S., Ha, M., Fegan, N., Dunshea, F. R., & Warner, R. D. (2020). Effects of heat stress on animal physiology, metabolism, and meat quality: A review. Meat science, 162, 108025.

- Nardone, A., Ronchi, B., Lacetera, N., & Bernabucci, U. (2006). Climatic effects on productive traits in livestock. Veterinary Research Communications, 30, 75.

- Berihulay, H., Abied, A., He, X., Jiang, L., & Ma, Y. (2019). Adaptation mechanisms of small ruminants to environmental heat stress. Animals, 9(3), 75.

- Pearce, S. C., Gabler, N. K., Ross, J. W., Escobar, J., Patience, J. F., Rhoads, R. P., & Baumgard, L. H. (2013). The effects of heat stress and plane of nutrition on metabolism in growing pigs. Journal of animal science, 91(5), 2108-2118.

- da Fonseca de Oliveira, A. C., Vanelli, K., Sotomaior, C. S., Weber, S. H., & Costa, L. B. (2019). Impacts on performance of growing-finishing pigs under heat stress conditions: a meta-analysis. Veterinary research communications, 43, 37-43.

- Ross, J. W., Hale, B. J., Seibert, J. T., Romoser, M. R., Adur, M. K., Keating, A. F., & Baumgard, L. H. (2017). Physiological mechanisms through which heat stress compromises reproduction in pigs. Molecular reproduction and development, 84(9), 934-945.

- Nawab, A., Ibtisham, F., Li, G., Kieser, B., Wu, J., Liu, W., ... & An, L. (2018). Heat stress in poultry production: Mitigation strategies to overcome the future challenges facing the global poultry industry. Journal of thermal biology, 78, 131-139.

- Ayo, J. O., Obidi, J. A., & Rekwot, P. I. (2011). Effects of heat stress on the well-being, fertility, and hatchability of chickens in the Northern Guinea Savannah Zone of Nigeria: A review. International Scholarly Research Notices, 2011(1), 838606.

- Thornton, P. K., van de Steeg, J., Notenbaert, A., & Herrero, M. (2009). The impacts of climate change on livestock and livestock systems in developing countries: A review of what we know and what we need to know. Agricultural systems, 101(3), 113-127.

- Thompson-Crispi, K. A., & Mallard, B. A. (2012). Type 1 and type 2 immune response profiles of commercial dairy cows in 4 regions across Canada. Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research, 76(2), 120-128.

- Bagath, M., Krishnan, G., Devaraj, C., Rashamol, V. P., Pragna, P., Lees, A. M., & Sejian, V. (2019). The impact of heat stress on the immune system in dairy cattle: A review. Research in veterinary science, 126, 94-102. [CrossRef]

- Chirico, J., Jonsson, P., Kjellberg, S., & Thomas, G. (1997). Summer mastitis experimentally induced by Hydrotaea irritans exposed to bacteria. Medical and veterinary entomology, 11(2), 187-192.

- Pearce, S. C., Sanz-Fernandez, M. V., Hollis, J. H., Baumgard, L. H., & Gabler, N. K. (2014). Short-term exposure to heat stress attenuates appetite and intestinal integrity in growing pigs. Journal of animal science, 92(12), 5444-5454.

- Wang, X. J., Feng, J. H., Zhang, M. H., Li, X. M., Ma, D. D., & Chang, S. S. (2018). Effects of high ambient temperature on the community structure and composition of ileal microbiome of broilers. Poultry Science, 97(6), 2153-2158.

- Grace, D.; Bett, B.K.; Lindahl, J.F.; Robinson, T.P. Climate and Livestock Disease: Assessing the Vulnerability of Agricultural Systems to Livestock Pests under Climate Change Scenarios. 2015. Available online: https://cgspace.cgiar.org/handle/10568/66595.

- Vitali, A., Felici, A., Esposito, S. I. L. V. I. A., Bernabucci, U., Bertocchi, L., Maresca, C., ... & Lacetera, N. (2015). The effect of heat waves on dairy cow Humanity. Journal of dairy science, 98(7), 4572-4579.

- Jeffrey, F.; Keown, R.J.G. How to Reduce Heat Stress in Dairy Cattle. University of Missouri Extension. Available online: https://extension.missouri.edu/publications/g3620 (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Saeed, M.; Abbas, G.; Alagawany, M.; Kamboh, A.A.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Khafaga, A.F.; Chao, S. Heat stress management in poultry farms: A comprehensive overview. J. Therm. Biol. 2019, 84, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla, P. R. , Skeg, J., Buendia, E. C., Masson-Delmotte, V., Pörtner, H. O., Roberts, D. C.,... & Malley, J. (2019). Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems.

- Ball, D.M.; Collins, M.; Lacefield, G.; Martin, N.; Mertens, D.; Olson, K.; Putnam, D.; Undersander, D.; Wolf, M. Understanding Forage Quality. American Farm Bureau Federation Publication. 2001. Available online: http://pss.uvm.edu/pdpforage/Materials/ForageQuality/Understanding_Forage_Quality_Ball.pdf.

- Collins, M.; Nelson, C.J.; Moore, K.J.; Barnes, R.F. Forages, Volume 1: An Introduction to Grassland Agriculture; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; 432p.

- Hopkins, A.; Prado, A.D. Implications of climate change for grassland in Europe: Impacts, adaptations and mitigation options: A review. Grass Forage Sci. 2007, 62, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, B.; Andueza, D.; Niderkorn, V.; Lüscher, A.; Porqueddu, C.; Picon-Cochard, C. A meta-analysis of climate change effects on forage quality in grasslands: Specificities of mountain and Mediterranean areas. Grass Forage Sci. 2015, 70, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polley, H.W.; Briske, D.D.; Morgan, J.A.; Wolter, K.; Bailey, D.W.; Brown, J.R. Climate change and North American rangelands: Trends, projections, and implications. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 66, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. AQUASTAT Website. 2016. Available online: https://www.fao.org/aquastat/en/overview/methodology/water-use (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Heinke, J.; Lannerstad, M.; Gerten, D.; Havlík, P.; Herrero, M.; Notenbaert, A.M.O.; Hoff, H.; Müller, C. Water Use in Global Livestock Production—Opportunities and Constraints for Increasing Water Productivity. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR026995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Downing, M. M., Nejadhashemi, A. P., Harrigan, T., & Woznicki, S. A. (2017). Climate change and livestock: Impacts, adaptation, and mitigation. Climate risk management, 16, 145-163.

- Watson, R. T., Zinyowera, M. C., & Moss, R. H. (Eds.). (1998). The regional impacts of climate change: an assessment of vulnerability. Cambridge University Press.

- Reynolds, C., Crompton, L., & Mills, J. (2010). Livestock and climate change impacts in the developing world. Outlook on Agriculture, 39(4), 245-248.

- Knee, B. W., Cummins, L. J., Walker, P., & Warner, R. (2004). Seasonal variation in muscle glycogen in beef steers. Australian Journal of Experimental Agriculture, 44(8), 729-734. 8.

- Hidosa, D., & Guyo, M. (2017). Climate change effects on livestock feed resources: A review. J. Fish. Livest. Prod, 5, 259.

- Bai, Y.; Deng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, Y. Does climate adaptation of vulnerable households to extreme events benefit livestock production? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 210, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, I.L.; Knapp, A.K. Shifting seasonal patterns of water availability: Ecosystem responses to an unappreciated dimension of climate change. N. Phytol. 2021, 233, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohmanova J, Misztal I and Cole JB, 2007. Temperaturehumidity indices as indicators of milk production losses due to heat stress. J Dairy Sci, 90(4): 1947-1956. [CrossRef]

- Dikmen S and Hansen PJ, 2009. Is the temperature-humidity index the best indicator of heat stress in lactating dairy cows in a subtropical environment? J Dairy Sci, 92(1): 109-116. [CrossRef]

- Nkuruma E, 2023. The Effects of environmental contaminants on animal health and reproduction. J Anim Health, 3(1): 1-12.

- IPCC, 2024. Climate Change Widespread, Rapid, and Intensifying. Available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/2021/08/09/ar6-wg1-20210809-pr/.

- Pasqui M and DiGiuseppe E, 2019. Climate change, future warming, and adaptation in Europe. Anim Front, 9(1): 6-11. [CrossRef]

- Roth Z, 2017. Effect of heat stress on reproduction in dairy cows: insights into the cellular and molecular responses of the oocyte. Annu Rev Anim Biosci, 5(1): 151-170. [CrossRef]

- Khodaei-Motlagh M, Shahneh AZ, Masoumi R and Derensis F, 2011. Alterations in reproductive hormones during heat stress in dairy cattle. Afr J Biotechnol, 10(29): 5552-5558.

- P. Pal1, F. Josan, P. Biswal, and S. Perveen, Indian J Anim Health (2024), 63(2)- Special Issue: 82- 93. [CrossRef]

- Getu A, 2015. The effects of climate change on livestock production, current situation and future consideration. Int J Agric Sci, 5(3): 494-499.

- Singh SV, Hooda OK, Narwade B, Baliyan B and Upadhyay RC, 2014. Effect of cooling system on feed and water intake, body weight gain and physiological responses of Murrah buffaloes during summer conditions. Ind J Dairy Sci, 67(5): 426-431.

- Bindari YR, Shrestha S, Shrestha N and Gaire TN, 2013. Effects of nutrition on reproduction- A review. Adv Appl Sci Res, 4(1): 421-429.

- Conte G, Ciampolini R, Cassandro M, Lasagna E, Calamari L et al., 2018. Feeding and nutrition management of heatstressed dairy ruminants. Ital J Anim Sci, 17(3): 604-620. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan G, Bagath M, Pragna P, Vidya MK, Aleena J et al., 2017. Mitigation of the Heat Stress Impact in Livestock Reproduction. In book: Theriogenology, pp 64-86. [CrossRef]

- Molinaro A, 2022. Animal Agriculture’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions Explained. Compassion in World Farming Morrell JM, 2020. Heat stress and bull fertility. Theriogenology, 153: 62-67. [CrossRef]

- Bace. ninaite . D, Dz ermeikaite . K and Antanaitis R, 2022. Global warming and dairy cattle: How to control and reduce methane emission. Animals, 12(19): 2687.

- Nguyen TPL, Seddaiu G, Virdis SGP, Tidore C, Pasqui M et al., 2016b. Perceiving to learn or learning to perceive? Understanding farmers’ perceptions and adaptation to climate uncertainties. Agric Sys, 143: 205-216. [CrossRef]

- Partha Ghosh, TVS Ravi Kumar and Graham Wright (2023), The impact of climate change on farmers in Bihar and how farmer producer organizations can help them adapt https://www.microsave.net/2023/01/27/the-impact-of-climate-change-on-farmers-in-bihar-and-how-farmer-producer-organizations-can-help-them-adapt/?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Dharmendra Kumar, Rajesh Kumar and Kumari Sharda (2028), Goat husbandry under changing climate scenario in Banka district, Bihar, Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry; SP1: 2329-2333.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).