Submitted:

20 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phage Isolation and Biological Features of R34L1 and R34L2

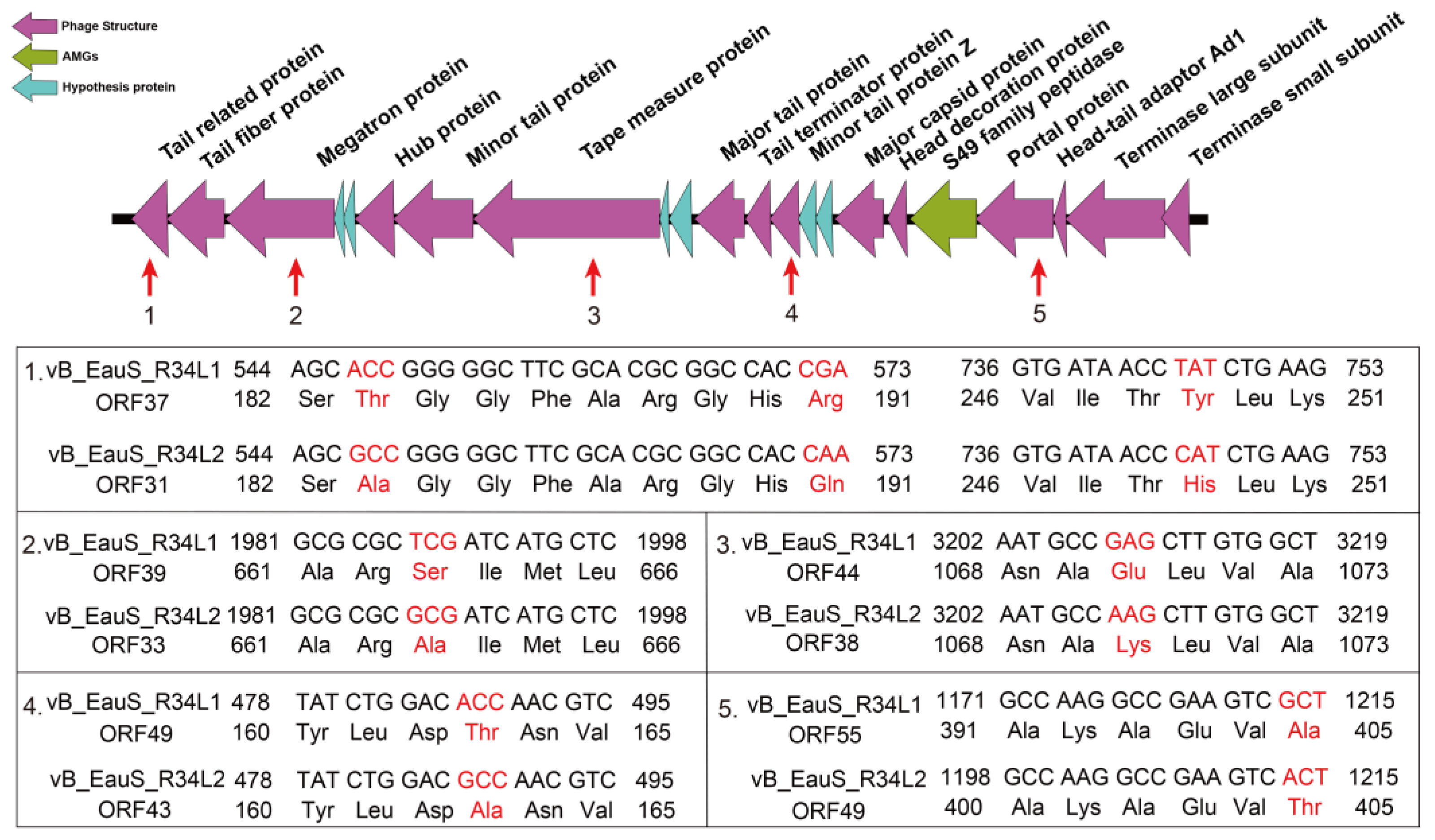

2.2. Genomic Features of R34L1 and R34L2

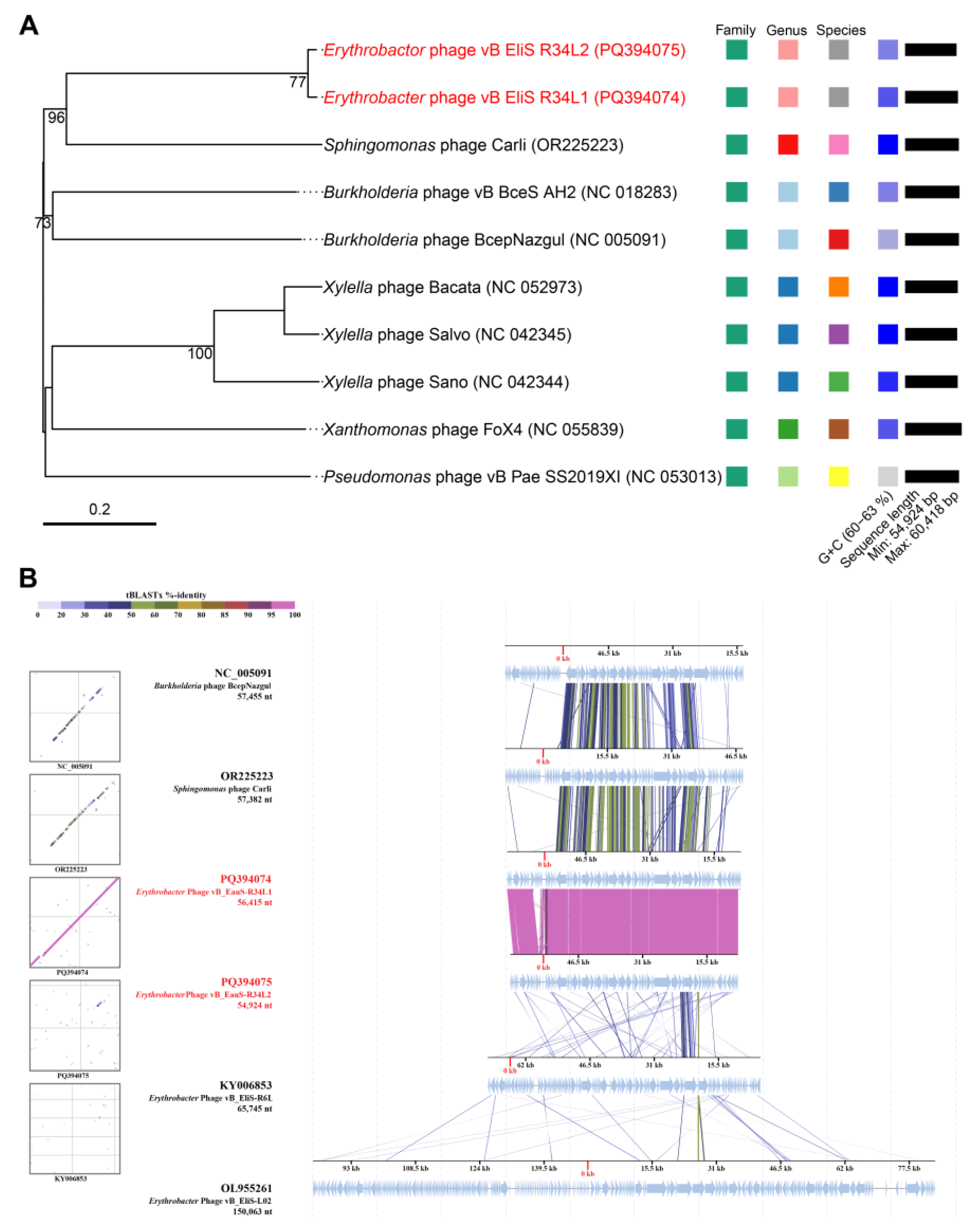

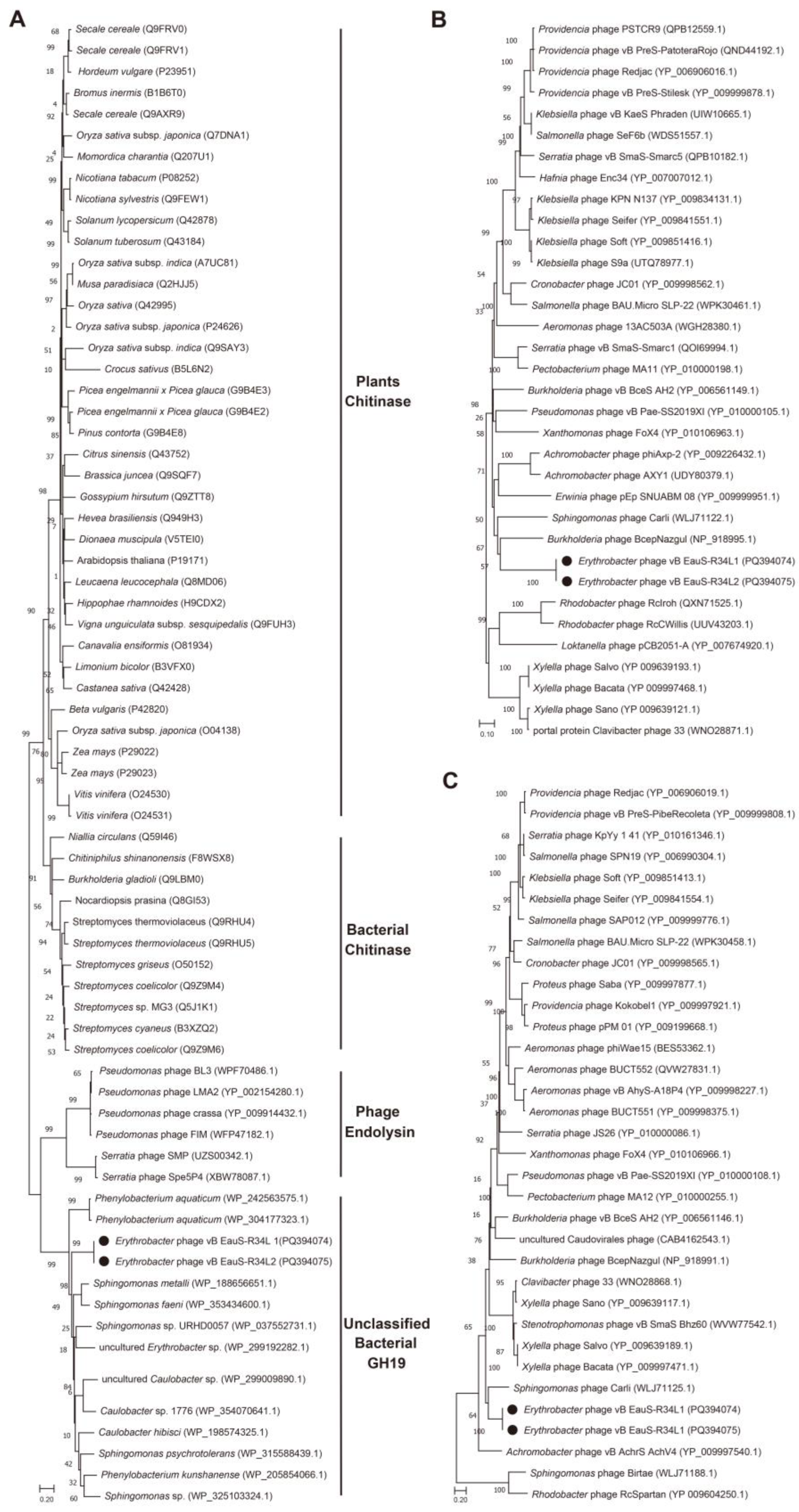

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis and Comparative Genomic Analyses

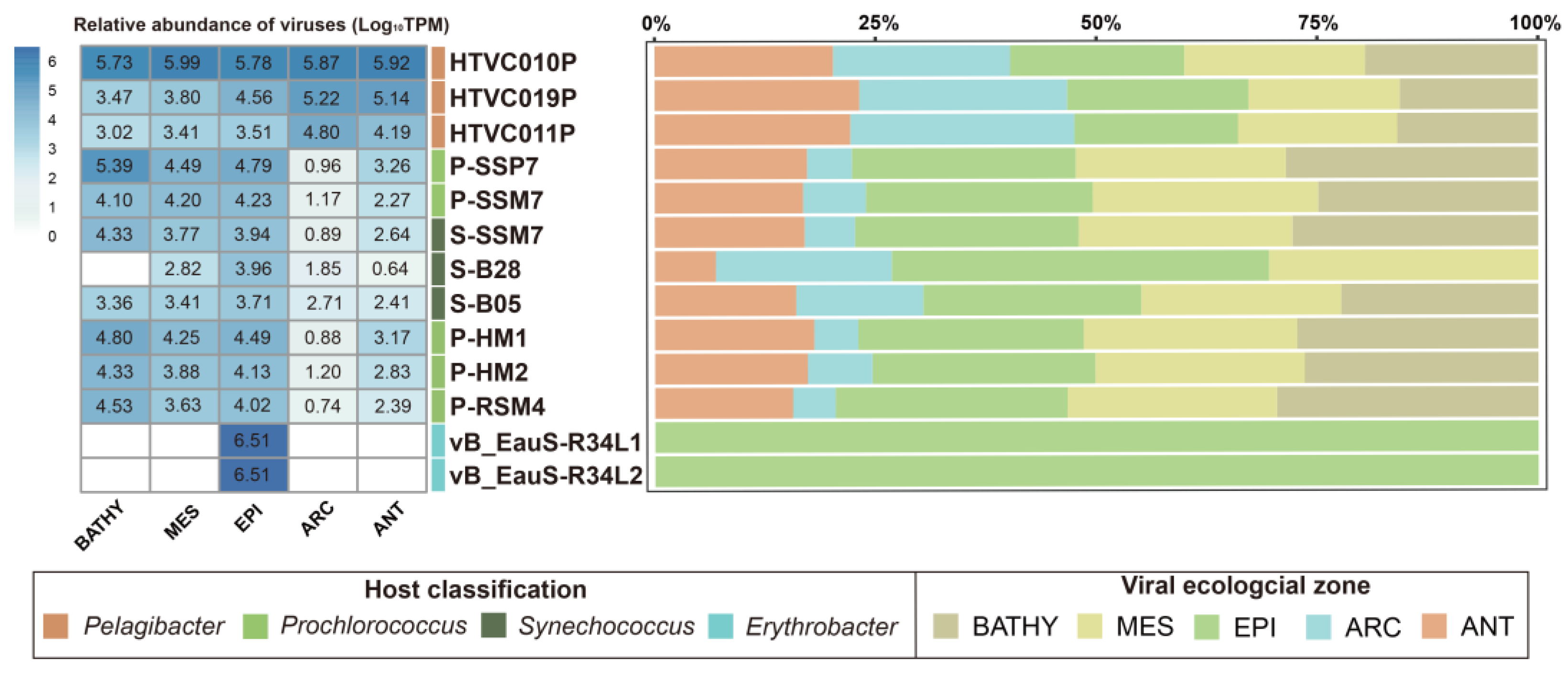

2.4. Marine Ecological Distribution of R34L1 and R34L2

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Isolation and Propagation of Phages

4.2. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

4.3. Chloroform Sensitivity

4.4. Host Range Test

4.5. One-step Growth Curve

4.6. Stability Characterization

4.7. Phage DNA Extraction, Genome Sequencing and Bioinformatics

4.8. Phylogenetic Analysis

4.9. Recruitment of Reads to Metagenomic Data

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kolber, Z.S.; Plumley, F.G.; Lang, A.S.; Beatty, J.T.; Blankenship, R.E.; VanDover, C.L.; Vetriani, C.; Koblizek, M.; Rathgeber, C.; Falkowski, P.G. Contribution of aerobic photoheterotrophic bacteria to the carbon cycle in the ocean. Science 2001, 292, 2492–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiler, A. Evidence for the ubiquity of mixotrophic bacteria in the upper ocean: implications and consequences. Appl Environ Microbiol 2006, 72, 7431–7437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Hong, N.; Liu, R.; Chen, F.; Wang, P. Distinct distribution pattern of abundance and diversity of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in the global ocean. Environ Microbiol 2007, 9, 3091–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Qiang, L.; Zou, L.; Zhang, Y. The research of typical microbial functional group reveals a new oceanic carbon sequestration mechanism—A case of innovative method promoting scientific discovery. Sci China Earth Sci 2016, 59, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiba, T.; Simidu, U. Erythrobacter longus gen. Nov., sp. nov., an aerobic bacterium which contains bacteriochlorophyll a. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1982, 32, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurkov, V.; Stackebrandt, E.; Holmes, A.; Fuerst, J.A.; Hugenholtz, P.; Golecki, J.; Gad'on, N.; Gorlenko, V.M.; Kompantseva, E.I.; Drews, G. Phylogenetic positions of novel aerobic, bacteriochlorophyll a-containing bacteria and description of Roseococcus thiosulfatophilus gen. nov., sp. nov., Erythromicrobium ramosum gen. nov., sp. nov., and Erythrobacter litoralis sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 1994, 44, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lai, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, W.; Xu, H.; Zheng, T. Erythrobacter luteus sp. nov., isolated from mangrove sediment. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2015, 65, 2472–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.W.; Yang, J.E.; Choi, Y.J. Isolation and characterization of a yellow xanthophyll pigment-producing marine bacterium, Erythrobacter sp. SDW2 strain, in coastal seawater. Marine Drugs 2022, 20, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Shao, Z. Erythrobacter atlanticus sp. nov., a bacterium from ocean sediment able to degrade polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2015, 65, 3714–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Lin, W.; Liu, Y.; Chen, C.; Jiao, N. A Comparison of 14 Erythrobacter genomes provides insights into the genomic divergence and scattered distribution of phototrophs. Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RoLing, W.F.; Milner, M.G.; Jones, D.M.; Lee, K.; Daniel, F.; Swannell, R.J.; Head, I.M. Robust hydrocarbon degradation and dynamics of bacterial communities during nutrient-enhanced oil spill bioremediation. Appl Environ Microb 2002, 68, 5537–5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafa, Y.S.; Alrumman, S.A.; Otaif, K.A.; Alamri, S.A.; Mostafa, M.S.; Sahlabji, T. Production and characterization of bioplastic by polyhydroxybutyrate accumulating Erythrobacter aquimaris isolated from mangrove rhizosphere. Molecules 2020, 25, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koblížek, M.; Béjà, O.; Bidigare, R.R.; Christensen, S.; Benitez-Nelson, B.; Vetriani, C.; Kolber, M.K.; Falkowski, P.G.; Kolber, Z.S. Isolation and characterization of Erythrobacter sp. strains from the upper ocean. Arch Microbiol 2003, 180, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Mao, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y.-N. Erythrobacter westpacificensis sp. nov., a marine bacterium isolated from the Western Pacific. Curr Microbiol 2013, 66, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Wu, Y.; Sun, C.; Wang, H.; Cheng, H.; Meng, F.; Wang, C.; Xu, X. Erythrobacter zhengii sp. nov., a bacterium isolated from deep-sea sediment. Int J Syst Evol 2019, 69, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinbauer, M.G. Ecology of prokaryotic viruses. FEMS microbiol rev 2004, 28, 127–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suttle, C.A. Marine viruses—major players in the global ecosystem. Nat rev microbiol 2007, 5, 801–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, N.; Robinson, C.; Azam, F.; Thomas, H.; Baltar, F.; Dang, H.; Hardman-Mountford, N.J.; Johnson, M.; Kirchman, D.L.; Koch, B.P. Mechanisms of microbial carbon sequestration in the ocean—future research directions. Biogeosciences 2014, 11, 5285–5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lu, L.; Yu, C. Isolation and characterization of a roseophage representing a novel genus in the N4-like Rhodovirinae subfamily distributed in estuarine waters. bioRxiv 2024, 2024–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Chen, F. Bacteriophages that infect marine roseobacters: genomics and ecology. Environ microbiol 2019, 21, 1885–1895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, F.; Jiao, N. Complete genome sequence of a marine roseophage provides evidence into the evolution of gene transfer agents in alphaproteobacteria. Virol J 2011, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suttle, C.A. Viruses in the sea. Nature 2005, 437, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, L.M.; Fuhrman, J.A. Viral mortality of marine bacteria and cyanobacteria. Nature 1990, 343, 60–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Xia, Q.; Du, S.; Zhang, Z.; Qin, F.; Zhao, Y. Genomic characterization and distribution pattern of a novel marine OM43 phage. Front Microbiol 2021, 12, 651326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Cai, L.; Jiao, N.; Zhang, R. Isolation and characterization of the first phage infecting ecologically important marine bacteria Erythrobacter. Virol J 2017, 14, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budinoff, C.R. Diversity and activity of roseobacters and roseophage, Doctor, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, May 2012.

- Li, X.; Guo, R.; Zou, X.; Yao, Y.; Lu, L. The first cbk-like phage infecting Erythrobacter, representing a novel siphoviral genus. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 861793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espejo, R.T.; Canelo, E.S. Properties of bacteriophage PM2: a lipid-containing bacterial virus. Virology 1968, 34, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Zhang, S.; Long, L.; Huang, S. Characterization and complete genome sequences of three N4-like roseobacter phages isolated from the South China Sea. Curr microbiol 2016, 73, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, K.; Jiao, N.; Chen, F. Genome sequences of two novel phages infecting marine roseobacters. Environ Microbiol 2009, 11, 2055–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Ma, R.; Chen, H.; Yang, Y.; Jiao, N.; Zhang, R. A newly isolated roseophage represents a distinct member of Siphoviridae family. Virol J 2019, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, T.M.; Chan, P.P. tRNAscan-SE On-line: integrating search and context for analysis of transfer RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, W54–W57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, P.P.; Lowe, T.M. tRNAscan-SE: searching for tRNA genes in genomic sequences. In Gene prediction. Methods in Molecular Biology; Kollmar, M. Eds, Ed.; Humana: New York, USA, 2019; Volume 1962, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.; Kropinski, A.M.; Adriaenssens, E.M. A roadmap for genome-based phage taxonomy. Viruses 2021, 13, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liang, Y.; Zheng, K.; Wang, Z.; Dong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ren, L.; Wang, H.; Han, Y.; McMinn, A. Characterization and genomic analysis of phage vB_ValR_NF, representing a new viral family prevalent in the Ulva prolifera blooms. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1161265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zheng, K.; Wang, M.; Ma, K.; Ren, L.; Guo, R.; Ma, L.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, Y. Shewanella phage encoding a putative anti-CRISPR-like gene represents a novel potential viral family. Microbiol Spectr 2024, 12, e03367–e03323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Ren, L.; Liang, Y.; Zheng, K.; Guo, R.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Han, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shao, H. Psychrobacter phage encoding an antibiotics resistance gene represents a novel caudoviral family. Microbiol Spectr 2023, 11, e05335–e05322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focardi, A.; Ostrowski, M.; Goossen, K.; Brown, M.V.; Paulsen, I. Investigating the diversity of marine bacteriophage in contrasting water masses associated with the East Australian Current (EAC) system. Viruses 2020, 12, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, E.; Aylward, F.O.; Mende, D.R.; DeLong, E.F. Bacteriophage distributions and temporal variability in the ocean’s interior. MBio 2017, 8, e01903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.L.; Charity, O.J.; Adriaenssens, E.M. Ecological and functional roles of bacteriophages in contrasting environments: marine, terrestrial and human gut. Curr Opin in Microbiol 2022, 70, 102229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Gaitero, M.; Seoane-Blanco, M.; van Raaij, M.J. Structure and function of bacteriophages. In Bacteriophages; Harper, D.R., Abedon, S.T., Burrowes, B.H., McConville, M.L., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 19–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marceau, A.H. Functions of single-strand DNA-binding proteins in DNA replication, recombination, and repair. In Single-Stranded DNA Binding Proteins: Methods and Protocols; Keck, J., Ed.; Humana: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2012; Volume 922, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipps, G.; Weinzierl, A.O.; von Scheven, G.; Buchen, C.; Cramer, P. Structure of a bifunctional DNA primase-polymerase. Nat struct mol biol 2004, 11, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Li, M.; Wang, T.; Wu, H.; Zhou, H.; Xu, C.; Yu, F.; Liu, X.; He, J. Crystal structure and biochemical studies of the bifunctional DNA primase-polymerase from phage NrS-1. Biochem Bioph Res Co 2019, 510, 573–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struck, A.W.; Thompson, M.L.; Wong, L.S.; Micklefield, J. S-adenosyl-methionine-dependent methyltransferases: highly versatile enzymes in biocatalysis, biosynthesis and other biotechnological applications. ChemBioChem 2012, 13, 2642–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Went, S.C.; Picton, D.M.; Morgan, R.D.; Nelson, A.; Brady, A.; Mariano, G.; Dryden, D.T.; Smith, D.L.; Wenner, N.; Hinton, J.C. Structure and rational engineering of the PglX methyltransferase and specificity factor for BREX phage defence. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 7236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaev, A.; Drobiazko, A.; Sierro, N.; Gordeeva, J.; Yosef, I.; Qimron, U.; Ivanov, N.V.; Severinov, K. Phage T7 DNA mimic protein Ocr is a potent inhibitor of BREX defence. Nucleic Acids Res 2020, 48, 5397–5406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raleigh, E.A.; Brooks, J.E. Restriction modification systems: where they are and what they do. In Bacterial genomes: physical structure and analysis; de Bruijn, F.J., Lupski, J.R., Weinstock, G.M., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maindola, P.; Raina, R.; Goyal, P.; Atmakuri, K.; Ojha, A.; Gupta, S.; Christie, P.J.; Iyer, L.M.; Aravind, L.; Arockiasamy, A. Multiple enzymatic activities of ParB/Srx superfamily mediate sexual conflict among conjugative plasmids. Nat commun 2014, 5, 5322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio-Valeriano, M.; Altegoer, F.; Steinchen, W.; Urban, S.; Liu, Y.; Bange, G.; Thanbichler, M. ParB-type DNA segregation proteins are CTP-dependent molecular switches. Cell 2019, 179, 1512–1524.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanner, N.K.; Cordin, O.; Banroques, J.; Doère, M.; Linder, P. The Q motif: a newly identified motif in DEAD box helicases may regulate ATP binding and hydrolysis. Mol cell 2003, 11, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuteja, N.; Tuteja, R. Prokaryotic and eukaryotic DNA helicases: essential molecular motor proteins for cellular machinery. Eur J Biochem 2004, 271, 1835–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennell, S.; Déclais, A.-C.; Li, J.; Haire, L.F.; Berg, W.; Saldanha, J.W.; Taylor, I.A.; Rouse, J.; Lilley, D.M.; Smerdon, S.J. FAN1 activity on asymmetric repair intermediates is mediated by an atypical monomeric virus-type replication-repair nuclease domain. Cell Rep 2014, 8, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, Y.; Mazaheri Nezhad Fard, R.; Seifi, A.; Mahfouzi, S.; Saboor Yaraghi, A.A. Genome Analysis of the Enterococcus faecium Entfac.YE Prophage. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol 2022, 14, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, M.; Buchholz, P.C.; Lotti, M.; Pleiss, J. The GH19 Engineering Database: Sequence diversity, substrate scope, and evolution in glycoside hydrolase family 19. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0256817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Rello, A. Diversity, specificity and molecular evolution of the lytic arsenal of Pseudomonas phages: in silico perspective. Environ Microbiol 2019, 21, 4136–4150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantarel, B.L.; Coutinho, P.M.; Rancurel, C.; Bernard, T.; Lombard, V.; Henrissat, B. The Carbohydrate-Active EnZymes database (CAZy): an expert resource for glycogenomics. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37, D233–D238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, J.G.; Hatfull, G.F.; Hendrix, R.W. Imbroglios of viral taxonomy: genetic exchange and failings of phenetic approaches. J Bacteriol 2002, 184, 4891–4905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, B.L.; U’Ren, J.M. Viral metabolic reprogramming in marine ecosystems. Curr Opin Microbiol 2016, 31, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, L.R.; Zeng, Q.; Kelly, L.; Huang, K.H.; Singer, A.U.; Stubbe, J.; Chisholm, S.W. Phage auxiliary metabolic genes and the redirection of cyanobacterial host carbon metabolism. PNAS 2011, 108, E757–E764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.S.; Haakonsen, D.L.; Zeng, W.; Schumacher, M.A.; Laub, M.T. A bacterial chromosome structuring protein binds overtwisted DNA to stimulate type II topoisomerases and enable DNA replication. Cell 2018, 175, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarry, M.J.; Harmel, C.; Taylor, J.A.; Marczynski, G.T.; Schmeing, T.M. Structures of GapR reveal a central channel which could accommodate B-DNA. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 16679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-J.; Leung, P.M.; Bay, S.K.; Hugenholtz, P.; Kessler, A.J.; Shelley, G.; Waite, D.W.; Cook, P.L.; Greening, C. Metabolic flexibility allows generalist bacteria to become dominant in a frequently disturbed ecosystem. BioRxiv 2020, 2020–02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, A.J.; Elling, F.J.; Castelle, C.J.; Zhu, Q.; Elvert, M.; Birarda, G.; Holman, H.-Y.N.; Lane, K.R.; Ladd, B.; Ryan, M.C. Lipid analysis of CO2-rich subsurface aquifers suggests an autotrophy-based deep biosphere with lysolipids enriched in CPR bacteria. The ISME J 2020, 14, 1547–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, E.G.; Schwartzman, J.A. Metagenome-assembled genomes of Macrocystis-associated bacteria. Microbiol Resour Ann 2024, 13, e00715–e00724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehl, K.; Lemire, S.; Yang, A.C.; Ando, H.; Mimee, M.; Torres, M.D.T.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C.; Lu, T.K. Engineering phage host-range and suppressing bacterial resistance through phage tail fiber mutagenesis. Cell 2019, 179, 459–469.e459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nobrega, F.L.; Vlot, M.; De Jonge, P.A.; Dreesens, L.L.; Beaumont, H.J.; Lavigne, R.; Dutilh, B.E.; Brouns, S.J. Targeting mechanisms of tailed bacteriophages. Nat Rev Microbiol 2018, 16, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jonge, P.A.; Nobrega, F.L.; Brouns, S.J.; Dutilh, B.E. Molecular and evolutionary determinants of bacteriophage host range. Trends Microbiol 2019, 27, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, X.; Wang, J. Structural mechanism of bacteriophage lambda tail’s interaction with the bacterial receptor. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, S.; Dover, J.A.; Parent, K.N.; Doore, S.M. Host range expansion of Shigella phage Sf6 evolves through point mutations in the tailspike. J Virol 2022, 96, e00929–e00922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurkov, V.V.; Krieger, S.; Stackebrandt, E.; Beatty, J.T. Citromicrobium bathyomarinum, a novel aerobic bacterium isolated from deep-sea hydrothermal vent plume waters that contains photosynthetic pigment-protein complexes. J Bacteriol 1999, 181, 4517–4525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajunen, M.; Kiljunen, S.; Skurnik, M. Bacteriophage phiYeO3-12, specific for Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O:3, is related to coliphages T3 and T7. J Bacteriol 2000, 182, 5114–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Q.; Chen, Q.; Xu, Y.; Suttle, C.A.; Jiao, N. A virus infecting marine photoheterotrophic alphaproteobacteria (Citromicrobium spp.) defines a new lineage of ssDNA viruses. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, F.A.; Fauquet, C.M.; Bishop, D.H.; Ghabrial, S.A.; Jarvis, A.W.; Martelli, G.P.; Mayo, M.A.; Summers, M.D. Virus taxonomy: classification and nomenclature of viruses, 6th eds; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.T.; Chang, S.Y.; Yen, M.R.; Yang, T.C.; Tseng, Y.H. Characterization of extended-host-range pseudo-T-even bacteriophage Kpp95 isolated on Klebsiella pneumoniae. Appl Environ Microbiol 2007, 73, 2532–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cai, L.; Ma, R.; Xu, Y.; Tong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Jiao, N.; Zhang, R. A novel roseosiphophage isolated from the oligotrophic South China Sea. Viruses 2017, 9, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besemer, J.; Lomsadze, A.; Borodovsky, M. GeneMarkS: a self-training method for prediction of gene starts in microbial genomes. Implications for finding sequence motifs in regulatory regions. Nucleic Acids Res 2001, 29, 2607–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delcher, A.L.; Bratke, K.A.; Powers, E.C.; Salzberg, S.L. Identifying bacterial genes and endosymbiont DNA with Glimmer. Bioinformatics 2007, 23, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Kuronishi, M.; Uehara, H.; Ogata, H.; Goto, S. ViPTree: the viral proteomic tree server. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2379–2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.R.; Stothard, P. The CGView Server: a comparative genomics tool for circular genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 2008, 36, W181–W184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohwer, F.; Edwards, R. The Phage Proteomic Tree: a genome-based taxonomy for phage. J Bacteriol 2002, 184, 4529–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Ouk Kim, Y.; Park, S.-C.; Chun, J. OrthoANI: an improved algorithm and software for calculating average nucleotide identity. Int J Syst Evol Micr 2016, 66, 1100–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraru, C.; Varsani, A.; Kropinski, A.M. VIRIDIC—A novel tool to calculate the intergenomic similarities of prokaryote-infecting viruses. Viruses 2020, 12, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Göker, M. VICTOR: genome-based phylogeny and classification of prokaryotic viruses. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3396–3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier-Kolthoff, J.P.; Auch, A.F.; Klenk, H.-P.; Göker, M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC bioinformatics 2013, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Madden, T.L.; Schäffer, A.A.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Miller, W.; Lipman, D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 1997, 25, 3389–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, A.C.; Zayed, A.A.; Conceição-Neto, N.; Temperton, B.; Bolduc, B.; Alberti, A.; Ardyna, M.; Arkhipova, K.; Carmichael, M.; Cruaud, C. Marine DNA viral macro-and microdiversity from pole to pole. Cell 2019, 177, 1109–1123.e1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3094–3100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vera Alvarez, R.; Pongor, L.S.; Mariño-Ramírez, L.; Landsman, D. TPMCalculator: one-step software to quantify mRNA abundance of genomic features. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 1960–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, F.; Han, F.; Ge, C.; Mao, W.; Chen, L.; Hu, H.; Chen, G.; Lang, Q.; Fang, C. OmicStudio: A composable bioinformatics cloud platform with real-time feedback that can generate high-quality graphs for publication. Imeta 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Phage name | Genome size (bp) | G+C% | ORFs | tRNA | Accession no. | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| vB_EauS-R34L1 | 56,415 | 61.60 | 78 | 0 | PQ394074 | This study |

| vB_EauS-R34L2 | 54,924 | 61.19 | 72 | 0 | PQ394075 | This study |

| vB_EliS-R6L | 65,675 | 66.52 | 108 | 0 | KY006853 | [25] |

| vB_ElisS-L02 | 150,063 | 59.43 | 61 | 29 | OL955261 | [27] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).