1. Introduction

Nanotechnology is a modern interdisciplinary field that uses many different techniques and tools from various disciplines, such as chemistry, medicine, biology, and engineering. By nanotechnology, we refer to research and development at the atomic, molecular and macromolecular level, which leads to the modification and study of structures and devices where the size ranges from 1-100 nm on the nanometer scale.

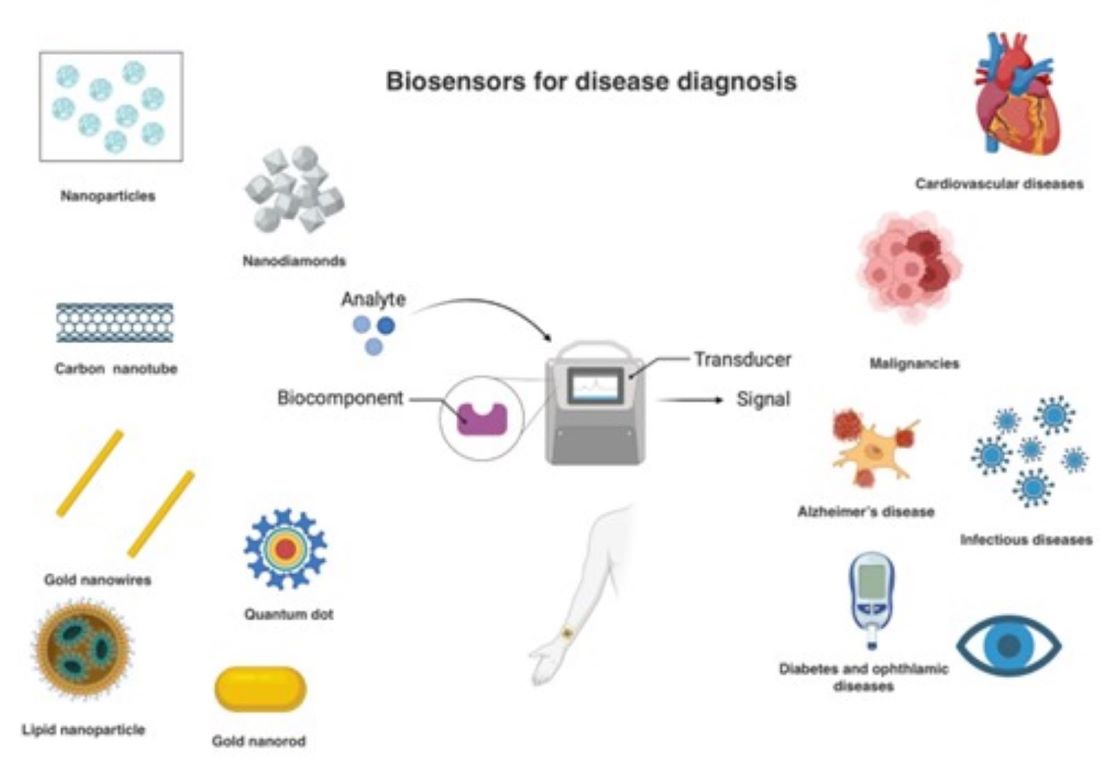

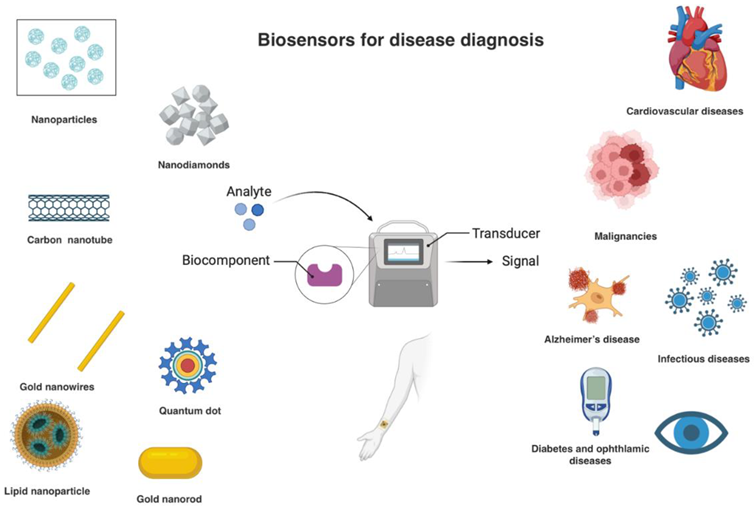

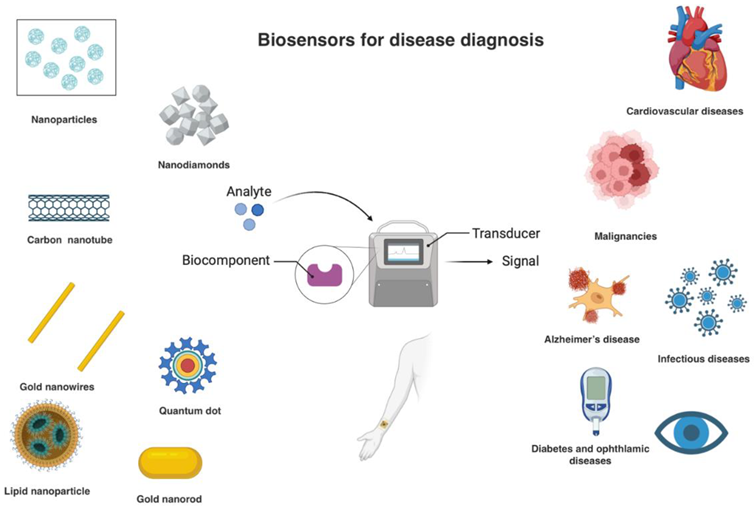

As far as biosensors are concerned, they are devices that combine biological recognition elements with a physical transducer, and have emerged as powerful tools for detecting and quantifying biomolecules. Their main parts are a biocatalyst that can detect a biological element, a transducer which converts the reaction of the biocatalyst and the biological element into a detectable parameter-signal and an electronic system that analyzes the detection [

1]. By integrating nanomaterials into these devices, nanobiosensors offer enhanced stability, sensitivity, selectivity, and rapid response times, enabling early and accurate disease diagnosis [

2].

This review explores the recent advancements in nanotechnology-based biosensors, focusing on their way of use and the wide range of diseases in the diagnosis of which they are applied. By understanding the fundamental principles and latest developments in this field, we finally aim to highlight the significant impact of nanobiosensors on future healthcare practices.

Figure 1.

Illustration of different components of nanobiosensors [

2].

Figure 1.

Illustration of different components of nanobiosensors [

2].

2. Nanomaterials Employed in Nano-Biosensors

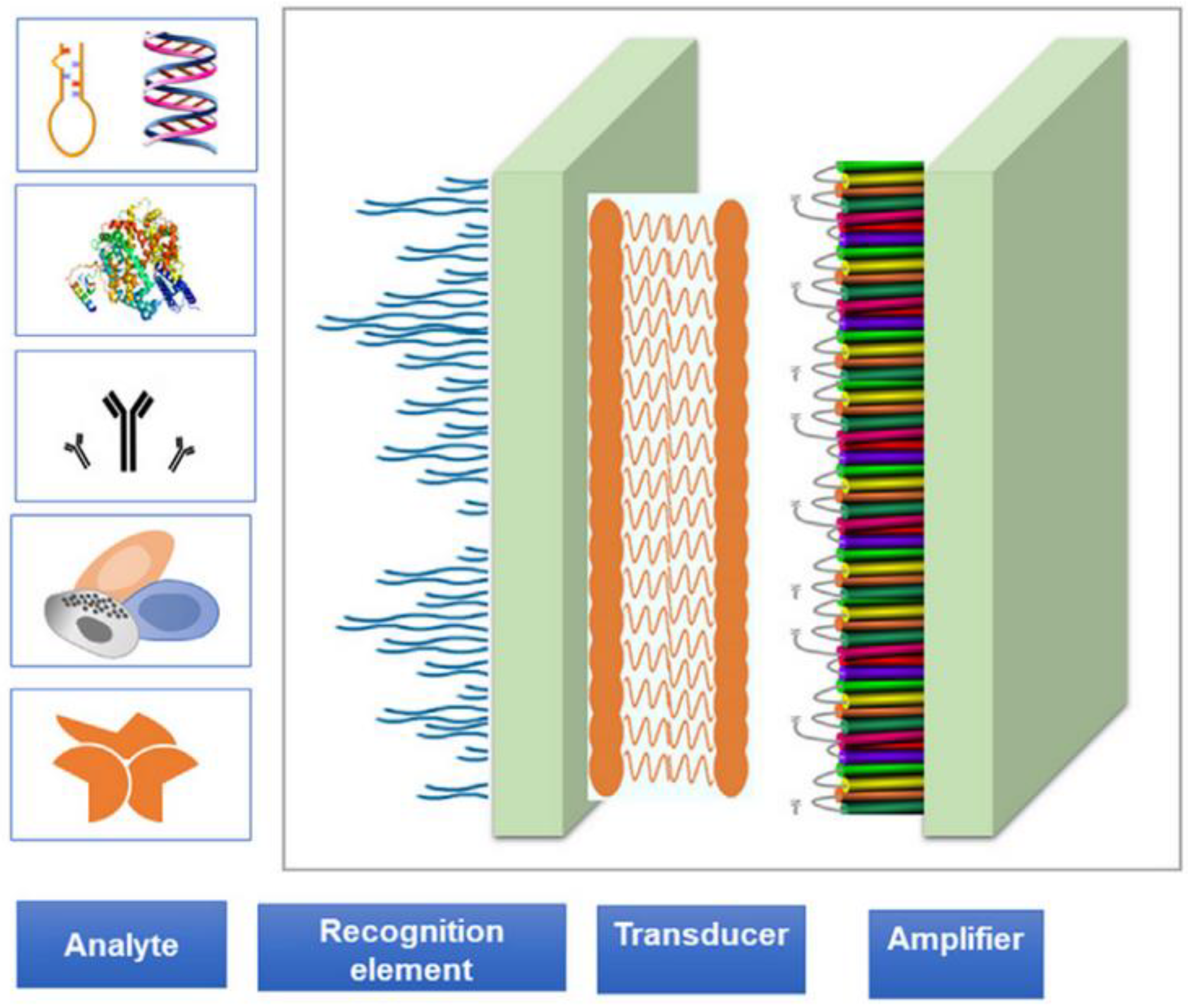

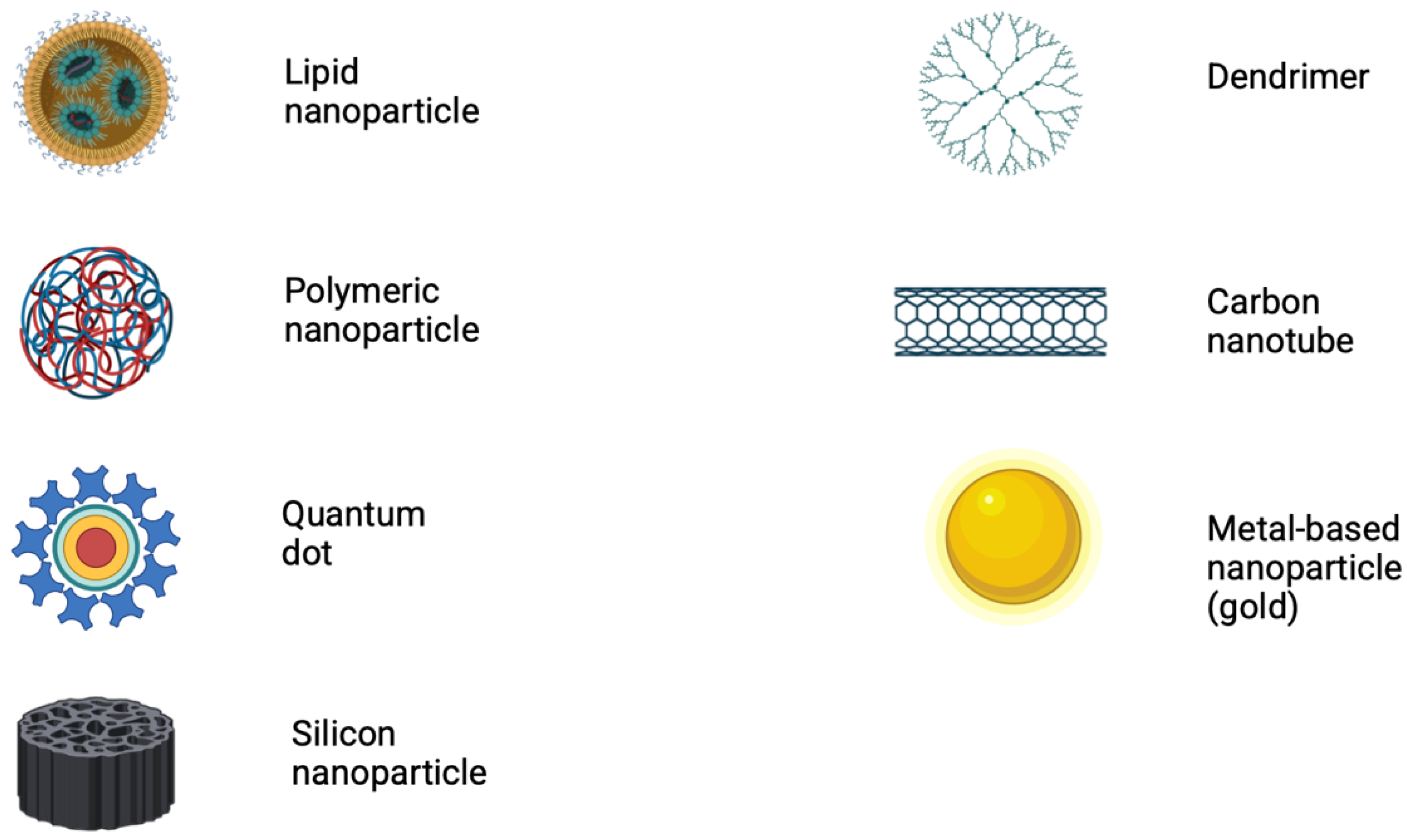

Nanotechnology-based biosensors have been designed using a number of nanomaterials, each providing the sensor with unique properties and benefits.

Figure 2 depicts the most commonly used nanomaterials in the manufacturing of biosensors for disease diagnosis.

Liposomes are microscopic phospholipid spherical vesicles surrounded by single or multiple lipid bilayers and are between 50 and 1000 nm in size [

2,

3]. They are formed by self-assembly from amphiphilic phospholipids and cholesterol in an aqueous medium . They are a category of nanoscale particles that can function as pharmaceutical carriers because they can change their properties depending on the process followed during their formation, their surface charge, and their size. They can also modify their surface by attaching PEG chains to the lipid bilayer, thus enhancing stability and prolonging their life span during blood circulation. Modified liposomes can also transport DNA molecules and proteins, and therefore exhibit a perfect pharmacokinetic profile. Finally, they are biocompatible and can trap hydrophilic compounds in the core and hydrophobic molecules in the lipid membrane [

4].

- ii.

Polymeric nanoparticles

Polymeric nanoparticles are colloidal systems with a diameter of less than 1 μm. They are divided into nanocapsules and nanospheres, depending on their composition [

2,

4,

5]. They are formed from biocompatible polymers where a micelle is then formed in an aqueous environment. There is a liquid core consisting of oil or water, in nanocapsules a bubbly structure is created, while in nanospheres they are matrix particles with a fixed mass [

3,

5,

6]. Both can encapsulate hydrophilic or hydrophobic small drug molecules and proteins. Also, the drug can be trapped, dissolved, or adsorbed to the nanoparticles depending on the mechanisms available. Specifically, in nanocapsules, the drug is encapsulated in the cavity of the liquid core, while in nanospheres it is encapsulated in the polymer matrix [

2].

- iii.

Quantum dots

Quantum dots (QDs) are dimensionless particles on the nanoscale, with a size of a few nanometres [

7]. Because of their small size, they are subject to the laws of quantum physics, which gives them unique electronic and optical properties, including tunable light emission, high signal brightness, and photostability. The electronic characteristics of dots are determined by their size and shape, which means that we can control the color of a dot by changing its size. Some of the advantages they have are due to their low signal intensity and photosensitivity. They consist of a semiconducting core resulting from compounds e.g. CdTe and CdSe, and a semiconducting broadband shell e.g. ZnS, which increases their surface area and enhances their quantum efficiency [

2,

3,

5]. On the other hand, some drawbacks hinder the application of the dots for in vivo research, such as the heavy metal ion toxicity of lead, arsenic, or cadmium-containing dots [

7,

8].

- iv.

Silicon nanoparticles

Another type of quantum dots are silicon nanoparticles, which have unique properties when they are less than 10 nm in size. Like quantum dots, these are in an advantageous position, because they exhibit a wide range of emission in the visible spectrum and high quantum yields. Also, because they are environmentally friendly and non-toxic, they are used as fluorescent detectors for bioimaging [

2,

3,

7,

8]. In addition, studies have shown that for in vivo applications they degrade in silicic acid and are excreted through urine [

2,

5,

6,

8]. Finally, they are considered safer than quantum dots which contain cadmium [

2,

3,

5].

- v.

Dendrimers

They are branched macromolecules made of natural or synthetic materials. They consist of a central core, a series of internal junctions, and a branched outer surface . The wide range of combinations of constituents gives dendrimers great uniformity and a defined shape, size, density, and branching length. They are also water-soluble and biocompatible and do not require biodegradation for their removal from the bloodstream via the kidneys [

4,

5,

7]. Their properties are controlled by the functional groups attached to their outer surface, through covalent bonding or electrostatic interactions. Specifically, chemical molecules, drugs, or detection and imaging agents can be attached to them, which alters their function, transforming them from simple sensors into specialized drug carriers. Thanks to the internal cavities in their structure, they can also encapsulate therapeutic agents in the inner core through chemical hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interaction [

2].

- vi.

Carbon nanoparticles

They are cylindrical carbon-based structures. These structures are designed in such a way that they resemble a sheet of graphite rolled into a cylinder [

5]. However, they are hexagonal networks of carbon atoms with a diameter of one nanometer and a length of 1-100 nm [

2,

9]. There are two categories, the monolayer and the multilayer [

3,

5]. C60 fullerenes are, also, carbon structures. They are hollow spherical structures based on carbon. Monostructures and fullerenes have a diameter of 1-2 nm, while polystructures range from a few nanometres to tens of nanometres depending on the structure. They can also vary in size from 1 μm to a few micrometers [

2,

9]. Fullerenes and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are manufactured by combustion or melting processes. The characterization of concentric shapes is based on their strength and stability. The nanotubes enter the cell through endocytosis, or the cell membrane [

2,

5].

- vii.

Metal-based nanoparticles

Magnetic nanoparticles are particulate materials smaller than 100 nm in size that are directed by a magnetic field [

2]. Various metals have been used for their synthesis, with gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) being of great importance in the field of biomedicine. They are considered chemically stable and suitable for in vivo applications, unlike most toxic nanoparticles e.g. cadmium [

3]. They are easily controllable because of their size and shape. The color of AuNPs changes according to their shape, and any change in their morphology alters the color [

8,

9,

10,

11]. There are also iron oxide nanoparticles, such as magnetite, maghemite and hematite. These particles can be prepared by the alkaline co-immersion of iron ions in water in the presence of a hydrophilic polymer, e.g. PEG. Finally, on the basis of the co-immersion process, crystals with a small diameter of 3-5 nm, hexagonal shape and polyethylene glycol molecules are formed [

6,

8,

9].

3. Types of Nanotechnology-Based Biosensors for Disease Diagnosis

The addition of nanomaterials (NMs) to biosensors endowed them with unique properties as a result of NMs’ high surface-to-volume ratio and the quantum confinement effects. Moreover, the sensing mechanisms are inextricably linked with the kind of the used nanomaterial and the analyte of the interest. The types of nanobiosensors for disease diagnosis based on the transduction process followed are described below:

- i.

Electrochemical Nanobiosensors

The main body of this type is an electroactive surface area, enhanced with NMs, such as metal nanoparticles, graphene or CNTs, onto which a specific biological probe is immobilized [

12,

13]. When this area interacts with the sample-target (e.g., a specific protein, RNA or DNA molecule etc.), it triggers a biochemical reaction, often involving electron transfer, that generates an electrical signal (current, voltage, or impedance). Depending on the signal measurement technique, the biosensors can be categorized into amperometric (for current changes), impedimetric (for electrical resistance changes), conductometric (for changes in solution conductivity), and potentiometric (for voltage differences). The intensity of the signal is correlated to the concentration of the target analyte [

13,

14].

- ii.

Optical Nanobiosensors

Optical nanobiosensors can visualize their interaction with the analyte and detect multiple substances using various light-based techniques, including absorption, luminescence, Raman spectroscopy, Surface Plasmon Resonance and refractive index changes. For this purpose, NMs (eg. AuNPs, AgNPs, graphene, QDs) are functionalized with biorecognition elements, such as antibodies, aptamers, or enzymes, that specifically bind to the target biomarker. NMs here act as a transducer and convert the biomolecular recognition event into a measurable optical signal, thanks to their optical properties. The produced signal is finally detected from a suitable optical detection system, such as a spectrometer, a photodetector, or a surface plasmon resonance imaging system [

2,

14].

- iii.

Piezoelectric Nanobiosensors

Generally, piezoelectric biosensors convert mass, pressure, force or strain changes into an electrical signal with the use of the piezoelectric effect. They usually consist of a suitable piezoelectric substrate, such as quartz crystal, between two metallic electrodes onto which the bioreceptor is immobilized. In case of piezoelectric nanobiosensors though, these electrodes are enhanced with NMs such as gold NPs for signal amplification or graphene/carbon nanotubes for high sensitivity. The mechanical stresses applied on the piezoelectric material, as a result of the interaction between the receptor and the analyte, provides an electric potential, a signal [

14,

15].

- iv.

Magnetic Nanobiosensors

Magnetic nanobiosensors’ operating principle is based on the forming of a magnetic nanoparticle (MNP), like iron oxide or ferrite nanoparticles, and a biomarker complex. More specifically, MNPs are functionalized with biorecognition elements (antibodies or DNA/RNA probes) in order for the target analyte to be able to bind to the sensor. The presence of the desirable complex can be detected with several techniques, including magnetoresistance, magnetic particle spectroscopy, and nuclear magnetic resonance, since the MNPs can change their magnetic properties such as their magnetic moment, relaxation time, or resonance frequency, when they interact with analytes [

15,

16].

- v.

Thermal or Calorimetric Nanobiosensors

Thermal or Calorimetric nanobiosensors exploit the high thermal conductivity of certain nanomaterials, such as graphene, gold nanoparticles, and carbon nanotubes, to facilitate the efficient transduction of heat generated or absorbed during a biorecognition event. Specifically, these nanomaterials serve as a platform for immobilizing biorecognition elements that interact with target molecules. The ensuing biochemical reaction produces a quantifiable thermal or calorimetric response, which is then measured by the sensor. The detection and the quantification of the analytes concentration are accomplished through the monitoring of temperature changes or heat flow [

15].

The optimal nanobiosensor for a specific disease diagnosis depends on the target analyte and the required level of sensitivity and selectivity. Even a combination of nanomaterials and sensing mechanisms can provide the desirable result.

4. Nanobiosensors for Disease Diagnosis

4.1. Cardiovascular Disease

One of the major applications of nanotechnology-based biosensors in the field of cardiovascular diseases includes the detection of biomarkers, such as cardiac troponin I and brain-natriuretic peptide for the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction and heart failure, respectively. Even though all types of biosensors have been used, reports suggest that electrochemical biosensors have the lowest detection threshold in both cases, with diagnostic yield increasing based on the nanomaterial used. QDs seem to retain superior results in comparison to other materials [

17,

18]. Other uses of nanobiosensors include identifying high-risk features in atherosclerotic plaques, when integrated in intravascular imaging modalities, such as intravascular ultrasound and optic coherence tomography [

19]. Nanomaterials have also been incorporated in non-invasive imaging techniques, such as magnetic resonance, ultrasound and nuclear scintigraphy for coronary artery disease diagnosis [

20]. Undoubtedly, the future in the diagnosis of many cardiovascular diseases, such as heart rhythm disorders and hypertension lies in wearables and cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIED). Up to this time point, the use of nanomaterials in wearables is still at a primitive stage, although CNTs, graphene and metal-based nanomaterials have been used in optical and electrochemical biosensors, in order to monitor physiologic parameters, such as heart rate and blood pressure [

21]. Jayathilaka et al. have also demonstrated the efficacy of piezoelectric strain sensors with graphene oxide worn as skin patches for radial and carotid pulses measurement and monitoring, as well as capacitive pressure sensors for heart rate detection. The potential of this technology extends to nanomaterial/nanofiber designed clothing for the monitoring of physiological parameters [

22]. Future research should be directed towards developing nanomaterial-based CIED for the diagnosis of arrhythmias and acute decompensations of heart failure [

23].

4.2. Cancer

Nanotechnology-based biosensors may aid in the timely diagnosis of some of the most common malignancies, such as breast, prostate and lung, by identifying related biomarkers and thus leading to earlier management. Most frequently, electrochemical and optical sensors are utilized owing to their superior sensitivity. As research in the field shifts towards personalization, the development of cost-effective, reliable and safe biosensors is expected to rise [

24]. Some of the most commonly employed nanomaterials and biosensing methods in the detection of biomarkers for various types of cancer are presented in

Table 1.

Recent advances include the integration of Raman sprectroscopy techniques in sensors, in order to lower the detection threshold of cancer biomarkers and improve diagnostic accuracy [

25,

26]. Incorporating ROS and nanoenzyme assays to biosensors has also shown improved detectability results. An example of such an electrochemiluminescent (ECL) biosensor is provided by Li et al. for the detection of neuron-specific enolase (NSE), a tumor marker for small cell lung carcinoma. Investigators also propose that the addition of gold nanoparticles to the structure further contributes to the stability of this sensing platform [

27]. Functional peptides seem also promising when used in combination with electrochemical and optical biosensors. These can be utilized in EC biosensors as bio-recognition elements, in the form of single or multifunctional peptide ligands or as enzyme substrates to identify enzyme-based cancer biomarkers, such as protein kinase. In the case of optical biosensors, functional peptides have proven valueable in conjunction with fluorescent, ECL, SERS, SPR and colorimetry techniques [

28]. Furthermore, as novel genomic, proteomic and metabolomic biomarkers are explored in areas such as breast cancer, nanotechnology-based biosensors able to detect those markers are currently under research. Nanomaterials considered include graphene oxide, metal and silica nanoparticles [

29]. Finally, a breakthrough in the development of point-of-care, sensitive and specific biosensing systems for cancer could be the advancement of microfluidic devices. These relatively low-cost systems have the ability of being combined with electrochemical or optical biosensing techniques to enhance detection threshold and of recognizing more than a single biomarker in one use and thus, hold immense potential as screening tools for breast cancer [

29].

Table 1.

Nanobiosensors used for the detection of common cancer biomarkers.

Table 1.

Nanobiosensors used for the detection of common cancer biomarkers.

| Biomarker |

Cancer |

Nanomaterial |

Method |

Reference |

| HER 2 |

Breast |

Metal NPs, QDs, CNTs, graphene |

EC, optical, piezoelectric |

[30] |

| CA 15.3 |

Breast |

Metal NPs |

EC |

[29] |

| SCC-Ag |

Ovarian |

CNTs |

EC |

[31] |

| CA 125 |

Ovarian |

Metal nanocomposite (NC), QDs, Magnetic NPs |

Optical, EC |

[32] |

| HE4 |

Ovarian |

Metal NC |

EC |

[33] |

| PSA |

Prostate |

Graphene, metal NPs, QDs, conducting polymers (CPs) |

EC, magnetic, fluorescence |

[34,35,36,37] |

| CEA |

Colorectal, pancreatic, lung |

Graphene, CPs, QDss |

EC |

[38] |

| AFP |

Hepatocellular |

Graphene, metal NPs, CPs |

EC |

[39] |

| NSE |

Lung |

Metal NWs, QDs, Graphene |

EC |

[40] |

| CYFRA-21-1 |

Oral, Lung |

Metal NPs, QDs |

|

[41] |

| FLT3-ITD Mutations |

Acute myeloid leukemia |

Metal NRs |

EC |

[42] |

| EGFR III |

Glioma |

QDs |

EC |

[24] |

| Anti-apoptotic protein |

Colorectal |

Graphene |

Optical |

[43] |

| PDGF-B, thrombin |

Gastric |

Metal-NPs |

Optical-SERS,SPR |

[25] |

4.3. Infectious Diseases

Nanosensors, which integrate nanomaterials with biosensing technologies, have revolutionized analytical and diagnostic fields, particularly in the detection and diagnosis of infectious diseases [

44,

45]. The unique properties of nanomaterials enable the development of highly sensitive and efficient sensors, offering a range of benefits such as enhanced sensitivity, selectivity, speed, robustness, and reduced sample consumption.

Table 2 describes some of the major signal types used in infectious disease detection.

Table 2.

Nanobiosensors with Different Modalities for the Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases.

Table 2.

Nanobiosensors with Different Modalities for the Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases.

| Virus/Bacterial |

Nanoparticles |

Detection Methods |

Reference |

| Hepatitis—C virus (HCV) |

AuNPs |

Colorimetric |

[46] |

| SARS-CoV-2 |

AuNPs |

Colorimetric |

[47] |

| MERS-CoV |

AgNPs |

Colorimetric |

[48] |

| AuNPs |

Electrochemiluminescence |

[49] |

| Genetic material (Bacteria or Virus) |

Magnetic NPs |

PCR |

[50] |

| Infuenza Virus |

AgNPs |

PCR |

[51] |

| AuNPs |

Thermometric |

[52] |

| E. coli |

AuNPs |

Colorimetric |

[63] |

| HBV |

AuNPs |

Colorimetric |

[53] |

| QD |

Fluorimetric |

[54] |

| EBOV |

MNPs |

EC |

[55] |

| AgNPs |

Colorimetric |

[56] |

| HIV |

MNPs |

Fluorimetric |

[57] |

| AuNPs |

SERS |

[58] |

| silica nanoparticles, AuNPs |

Electrochemiluminometry |

[59] |

| HPV |

graphene, Au nanorod |

EC |

[60] |

| AgNPs |

Colorimetric |

[61] |

| MTB (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) |

AgNPs |

Colorimetric |

[64] |

| Salmonella |

Gold-coated magnetic nanoparticle |

Colorimetric |

[62] |

In the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic and other viral outbreaks, developing advanced detection technologies is crucial due to the rapid spread of viruses and the vaccine's response. Nanotechnology holds significant potential in this area [

47]. Nanoparticles (NPs) offer unique advantages due to their high surface-to-volume ratio, quantum and size effects, and increased adsorption and reactivity compared to bulk materials. NPs can also be customized in size and shape, allowing for surface modifications with various biological species. These properties enhance biosensing capabilities, leading to improved detection limits, sensitivity, selectivity, and faster responses to analytes. Coronaviruses are a type of enveloped virus with spike proteins covering their outer surface. They have a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA genome that is about 32 kb in length and functions as mRNA during the synthesis of replicase polyproteins. Belonging to the Nidovirales family, these viruses have a roughly spherical shape with a diameter of approximately 125 nm. Coronaviruses are frequently found in respiratory tract fluids, and SARS-CoV-2 has also been detected in human blood, saliva, and stool samples.

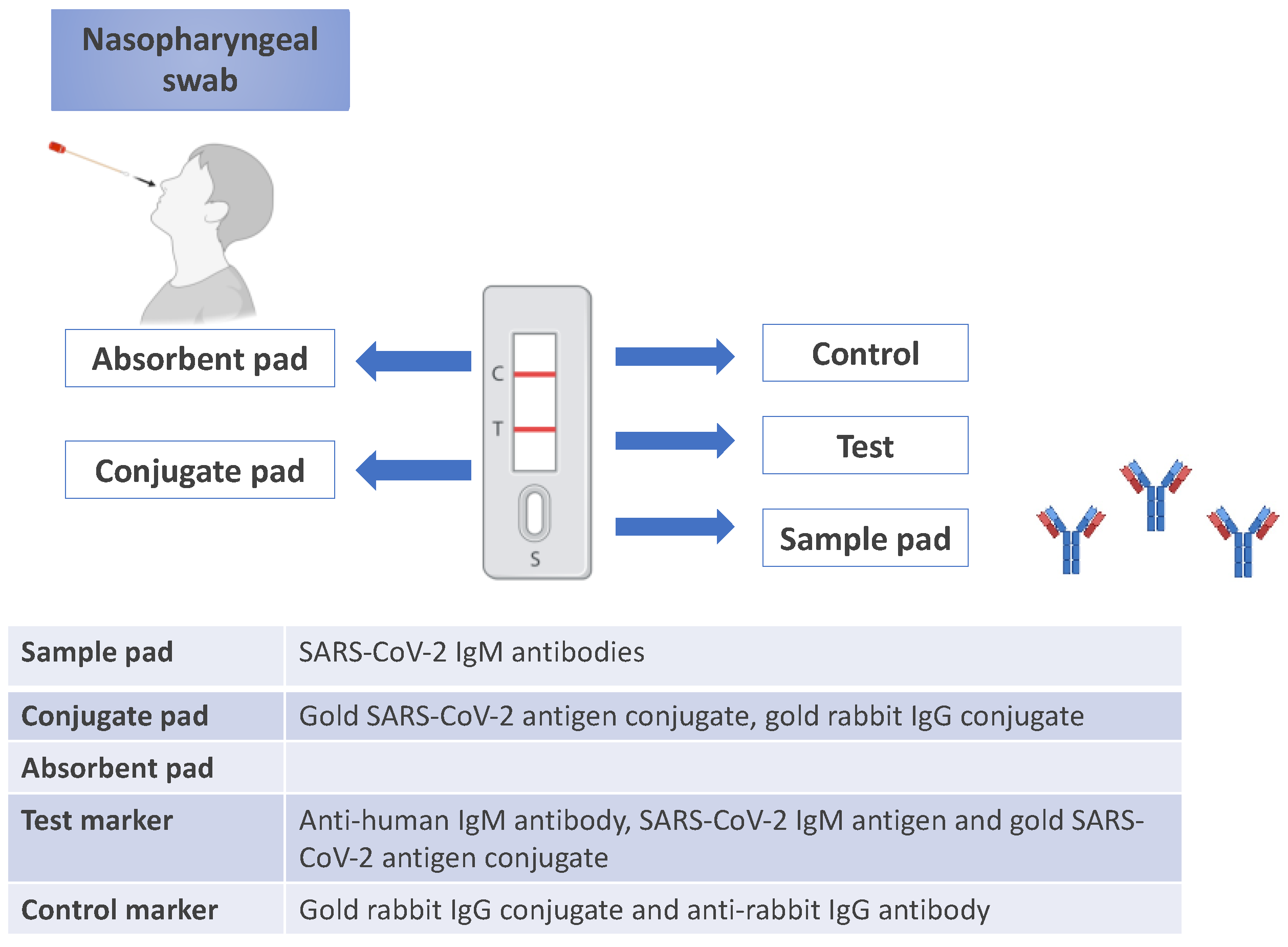

Lateral flow immunochromatographic assays are commonly used in point-of-care (POC) testing due to their affordability, rapid results, and ease of use in both laboratory and personal healthcare settings. These test strips are well-suited for mass production and commercial applications. A positive result typically appears as a red or pink line on the strip, which occurs when human antibodies, viral antigens, and gold nanoparticle complexes interact at the M or G line. In contrast, other antibodies do not produce a visible color change.

A specific lateral flow assay test strip was designed for COVID-19 detection. This test employed anti-human IgG and IgM antibodies along with a recombinant antigen that acted as the SARS-CoV-2 receptor. Gold nanoparticles were combined with the recombinant antigen and processed through incubation, centrifugation, and re-suspension to form AuNP-COVID-19 antigen conjugates. The control line contained an anti-rabbit IgG antibody, while the conjugate pad was treated with both AuNP-COVID-19 antigen and AuNP-rabbit IgG conjugates. Anti-human IgG and IgM antibodies were immobilized at the G and M test lines, respectively. This test strip allowed for the simultaneous detection of IgM and IgG within 15 minutes.

These strips are effective due to the biocompatibility, chemical versatility, large surface-to-volume ratio, size-dependent optical properties, and ease of surface modification of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs). Even at very low concentrations, such as 1 ng/mL for COVID-19 antigen or 1000 virus particles/mL for SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, AuNPs enable rapid detection visible to the naked eye [

45]. An example of a point-of-care lateral flow assay for SARS-CoV-2 IgM antibody testing -indicative of recent infection- is shown in Figure 4.

Nanoparticles (NPs) offer unique advantages due to their high surface-to-volume ratio, quantum and size effects, and increased adsorption and reactivity compared to bulk materials. NPs can also be customized in size and shape, allowing for surface modifications with various biological species. These properties enhance biosensing capabilities, leading to improved detection limits, sensitivity, selectivity, and faster responses to analytes.

AuNPs-based flow strips are widely used for detecting various toxins, viruses, and bacteria, including COVID-19 antigens and antibodies. These strips are effective due to the biocompatibility, chemical versatility, large surface-to-volume ratio, size-dependent optical properties, and ease of surface modification of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs). Even at very low concentrations, such as 1 ng/mL for COVID-19 antigen or 1000 virus particles/mL for SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, AuNPs enable rapid detection visible to the naked eye [

45]. An example of a point-of-care lateral flow assay for SARS-CoV-2 IgM antibody testing -indicative of recent infection- is shown in

Figure 3.

4.4. Neurological Diseases

Nanotechnology-based biosensors can be a great asset in the timely and precise diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases, thus halting the progression and permanent brain tissue damage.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is marked by the aggregation of beta-amyloid (β-A) peptides, specifically β-A1–42, which aggregate to form neurotoxic plaques in the brain. Electrochemical nano-biosensors, utilizing AuNPs and CNTs, offer a promising approach to AD diagnosis by detecting β-A in biological fluids. These biosensors rely on methods like cyclic voltammetry (CV), electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and squarewave voltammetry (SWV) to measure changes in the sensor surface, as β-A binds or aggregates. Their sensitivity to β-A peptide presence and concentration allows for early detection and ongoing monitoring of AD pathology [65].

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a result of protein misfolding, especially α-synuclein, which is accumulated in brain cells and can be detected on other body tissues as well, thus possibly serving as a biomarker for the disease. Electrochemical biosensors designed with graphene nanosheets, nanospherical porous organic polymers have been developed to recognize this significant protein in the pathophysiology of the disorder [66]. In addition, optical biosensors utilizing LSPR techniques also enable identification of a-synuclein via a mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUA)-capped gold nanorod (GNR)-coated and chitosan (CH)-immobilized fiber optic probe [67]. In addition, graphene oxide (EGO) and gold nanowires have been used in EC biosensors to target miRNAs, another potential biomarker for PD [68]. Finally, dopamine -as a significant neurotransmitter that is frequently associated with neurodegenerative diseases, including AD, PD and Huntington’s disease- can be detected using electrochemical biosensors with gold nanoparticles, via a fast and reliable method [69].

4.5. Other Diseases

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), a hormonal disorder characterized by insulin resistance and excess androgen production, also benefits from electrochemical nano-biosensors. These sensors detect biomarkers such as testosterone, insulin-like growth factor 1 and sex hormone-binding globulin, which are essential indicators of hormonal imbalance in PCOS. By incorporating materials like AuNPs, multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) and graphene, these biosensors enhance electron transfer rates and lower detection limits, making them valuable tools for more accurate and sensitive PCOS diagnosis [70].

For food allergies, nano-biosensors provide an effective detection of allergens, which is critical for safety in food processing and allergy management. Electrochemical biosensors, especially voltametric and impedance based, measure allergenic proteins or specific Immunoglobulin E antibodies associated with food allergies. The use of nanomaterials such as graphene, magnetic and AuNPs enhances the biosensor's sensitivity and binding affinity, enabling the detection of low concentrations of allergenic proteins, including Ara h1 (peanuts), gliadin (gluten) and ovalbumin (egg proteins). Some optical biosensors with gold nanoparticles even offer visual detection, by changing color upon allergen presence, making these tools both accessible and practical for quick, on-site testing [71].

Ophthalmic diseases, including glaucoma, dry eye disease and age-related macular degeneration, can also be diagnosed with nano-biosensors. These devices detect biomarkers in tear fluid and measure intraocular pressure. Nanomaterials like QDs, AuNPs and bioactive glass nanoparticles (BGNs) provide high biocompatibility and optical sensitivity for reliable measurements in ocular applications. Additionally, extracellular vehicles (EVs), such as exosomes, are incorporated for their ability to carry disease-specific biomarkers, facilitating precise diagnosis of eye-related conditions [72].

Diabetes diagnosis and monitoring benefit from nano-biosensors, specifically electrochemical glucose sensors that detect glucose levels in biological fluids. By employing glucose oxidase and other enzyme-based reactions, these sensors generate measurable electrochemical signals indicative of blood glucose levels. Alternatives to enzymatic approaches, such as Co₃O₄/N-doped CNTs, enable glucose oxidation directly, expanding the potential for continuous and non-invasive glucose monitoring. Nanomaterials, like CNTs, GQDs and magnetic nanoparticles, improve sensor stability and sensitivity, making these biosensors indispensable for managing diabetes and preventing complications [73].

For Down Syndrome (DS), carboxylated graphene oxide-based (GO-based) SPR aptasensors enable the sensitive detection of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), a crucial biomarker for DS risk assessment. The GO surface enhances the nanomaterial-based sensor’s stability and selectivity, allowing it to detect hCG at minimal concentrations in maternal serum, for early and non-invasive DS screening in prenatal diagnostics [74].

Additionally, electrochemical nano-biosensors have emerged as effective tools for the early detection of biomarkers, such as neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin and cystatin C, that signal kidney damage prior to changes in traditional indicators, such as serum creatinine. The integration of graphene-based nanomaterials and gold-modified electrodes significantly enhances the sensors’ performance [75].

6. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Nanotechnology-based biosensors represent a revolutionary advancement in disease diagnostics, offering increased sensitivity, specificity and rapid time response. These innovative tools have the potential to surpass conventional diagnostic methods, enabling earlier detection, and improve disease management, ranging from cancer and cardiovascular conditions to infectious and neurological disorders. The integration of nanomaterials, such as QDs, CNTs and AuNPs, enhances the functionality of nanobiosensors, laying the foundations for portable and point-of-care diagnostics. Despite these advantages, challenges remain. Among the most pressing are concerns regarding the toxicity of NPs and the potential long-term impacts on human health. Therefore, the clinical adoption of nanobiosensors must be facilitated by sufficient large-scale trials to validate their stability, safety and reproducibility. Looking ahead, research should focus on utilizing and developing biocompatible and environmentally friendly nanomaterials, optimizing their integration with biosensing platforms. Coupled with advances in artificial intelligence and nanotechnology, nanobiosensors are set to transform global healthcare, by delivering accessible, reliable and sustainable diagnostic solutions.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, ES and E.P.E; methodology, A.-E.K., M.C, D.Z, E.O, and E.C; writing—original draft preparation, A.-E.K., D.Z, E.O, E.C and M.C; and writing—review and editing, E.P.E., E.S.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

This review was conducted in the Frame of Master Program entitled “Nanomedicine” for the academic year 2024–2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sanjay Kisan Metkar and Koyeli Girigoswami,” Diagnostic Biosensors in Medicine- a Review”, Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology, vol.17, p. 271-283, January 2019. [CrossRef]

- Song, F. X., Xu, X., Ding, H., Yu, L., Huang, H., Hao, J., Wu, C., Liang, R., & Zhang, S. (2023). Recent Progress in Nanomaterial-Based Biosensors and Theranostic Nanomedicine for Bladder Cancer. In Biosensors (Vol. 13, Issue 1). MDPI. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Zhao, Z., Haque, F., & Guo, P. (2018). Engineering of protein nanopores for sequencing, chemical or protein sensing and disease diagnosis. In Current Opinion in Biotechnology (Vol. 51, pp. 80–89). Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- X. Ma and S. J. Sim, “Single plasmonic nanostructures for biomedical diagnosis,” Journal of Materials Chemistry B, vol. 8, no. 29. Royal Society of Chemistry, pp. 6197–6216, Aug. 07, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Sreejith, J. Ajayan, J. M. Radhika, N. v. Uma Reddy, and M. Manikandan, “Recent advances in nano biosensors: An overview,” Measurement: Journal of the International Measurement Confederation, vol. 236. Elsevier B.V., Aug. 15, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Popescu, M. Oana, M. Fufă, and A. M. Grumezescu, “Metal-based nanosystems for diagnosis,” Rom J Morphol Embryol, vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 635–649, 2015, [Online]. Available: http://www.rjme.ro/.

- Tufani, A. Qureshi, and J. H. Niazi, “Iron oxide nanoparticles based magnetic luminescent quantum dots (MQDs) synthesis and biomedical/biological applications: A review,” Materials Science and Engineering C, vol. 118. Elsevier Ltd, Jan. 01, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Aykaç et al., “An Overview on Recent Progress of Metal Oxide/Graphene/CNTs-Based Nanobiosensors,” Nanoscale Research Letters, vol. 16, no. 1. Springer, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Ramesh, R. Janani, C. Deepa, and L. Rajeshkumar, “Nanotechnology-Enabled Biosensors: A Review of Fundamentals, Design Principles, Materials, and Applications,” Biosensors, vol. 13, no. 1. MDPI, Jan. 01, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Darwish, W. Abd-Elaziem, A. Elsheikh, and A. A. Zayed, “Advancements in nanomaterials for nanosensors: a comprehensive review,” Nanoscale Advances, vol. 6, no. 16. Royal Society of Chemistry, pp. 4015–4046, May 24, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Qureshi, W. W. W. Hsiao, L. Hussain, H. Aman, T. N. Le, and M. Rafique, “Recent Development of Fluorescent Nanodiamonds for Optical Biosensing and Disease Diagnosis,” Biosensors, vol. 12, no. 12. MDPI, Dec. 01, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Fereshteh Rahdan et al., “MicroRNA electrochemical biosensors for pancreatic cancer”,Clinica Chimica Acta, vol.548, 1 August 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jules L. Hammond et al., “Electrochemical biosensors and nanobiosensors”, Essays in Biochemistry, vol. 60 (1), 30 June 2016, p. 69-80. [CrossRef]

- Lino et al., “Biosensors as diagnostic tools in clinical applications”, Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Reviews on Cancer, vol. 1877 (3), May 2022. [CrossRef]

- Anchal Pradhan et al., “Biosensors as Nano-Analytical Tools for COVID-19 Detection”, Sensors, vol. 21(23), 7823, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kai Wu et al., “Magnetic-Nanosensor-Based Virus and Pathogen Detection Strategies before and during COVID-19”, ACS Applied Nano Materials, vol.3,p. 9560-9580, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Tabish, H. Hayat, A. Abbas, and R. J. Narayan, “Graphene Quantum Dots-Based Electrochemical Biosensing Platform for Early Detection of Acute Myocardial Infarction.,” Biosensors, vol. 12, no. 2, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Gachpazan et al., “A review of biosensors for the detection of B-type natriuretic peptide as an important cardiovascular biomarker.,” Anal. Bioanal. Chem., vol. 413, no. 24, pp. 5949–5967, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, F. Centurion, R. Chen, and Z. Gu, “Intravascular Imaging of Atherosclerosis by Using Engineered Nanoparticles.,” Biosensors, vol. 13, no. 3, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Q. Hu, Z. Fang, J. Ge, and H. Li, “Nanotechnology for cardiovascular diseases.,” Innov. (Cambridge, vol. 3, no. 2, p. 100214, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Yang, Z. Ye, Y. Ren, M. Farhat, and P.-Y. Chen, “Recent Advances in Nanomaterials Used for Wearable Electronics,” Micromachines, vol. 14, no. 3. 2023.

- W. A. D. M. Jayathilaka et al., “Significance of Nanomaterials in Wearables: A Review on Wearable Actuators and Sensors.,” Adv. Mater., vol. 31, no. 7, p. e1805921, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. Tang, J. Yang, Y. Wang, and R. Deng, “Recent Advances in Cardiovascular Disease Biosensors and Monitoring Technologies.,” ACS sensors, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 956–973, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Shandilya, A. Bhargava, N. Bunkar, R. Tiwari, I. Y. Goryacheva, and P. K. Mishra, “Nanobiosensors: Point-of-care approaches for cancer diagnostics,” Biosens. Bioelectron., vol. 130, pp. 147–165, 2019. [CrossRef]

- cP. Shao et al., “Aptamer-Based Functionalized SERS Biosensor for Rapid and Ultrasensitive Detection of Gastric Cancer-Related Biomarkers.,” Int. J. Nanomedicine, vol. 18, pp. 7523–7532, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Foroozandeh, M. Abdouss, H. SalarAmoli, M. Pourmadadi, and F. Yazdian, “An electrochemical aptasensor based on g-C3N4/Fe3O4/PANI nanocomposite applying cancer antigen_125 biomarkers detection,” Process Biochem., vol. 127, pp. 82–91, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Li et al., “CePO4/CeO2 heterostructure and enzymatic action of D-Fe2O3 co-amplify luminol-based electrochemiluminescence immunosensor for NSE detection,” Biosens. Bioelectron., vol. 214, p. 114516, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Cao et al., “Application of functional peptides in the electrochemical and optical biosensing of cancer biomarkers,” Chem. Commun., vol. 59, no. 23, pp. 3383–3398, 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Ranjan et al., “Biosensor-based diagnostic approaches for various cellular biomarkers of breast cancer: A comprehensive review.,” Anal. Biochem., p. 113996, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Chupradit et al., “Recent advances in biosensor devices for HER-2 cancer biomarker detection,” Anal. Methods, vol. 14, no. 13, pp. 1301–1310, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Liang, Q. Qu, Y. Chang, S. C. B. Gopinath, and X. T. Liu, “Diagnosing ovarian cancer by identifying SCC-antigen on a multiwalled carbon nanotube-modified dielectrode sensor,” Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem., vol. 66, no. 6, pp. 939–944, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Elhami et al., “Sensitive and Cost-Effective Tools in the Detection of Ovarian Cancer Biomarkers.,” Anal. Sci. Adv., vol. 5, no. 9–10, p. e202400029, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Hu, Z. Mu, F. Gong, M. Qing, Y. Yuan, and L. Bai, “A signal-on electrochemical aptasensor for sensitive detection of human epididymis protein 4 based on functionalized metal–organic framework/ketjen black nanocomposite,” J. Mater. Sci., vol. 58, pp. 1–13, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Pothipor et al., “Highly sensitive biosensor based on graphene–poly (3-aminobenzoic acid) modified electrodes and porous-hollowed-silver-gold nanoparticle labelling for prostate cancer detection,” Sensors Actuators B Chem., vol. 296, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Jia et al., “DNA precisely regulated Au nanorods/Ag2S quantum dots satellite structure for ultrasensitive detection of prostate cancer biomarker,” Sensors Actuators B Chem., vol. 347, p. 130585, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Mohammadi and Z. Mohammadi, “Functionalized NiFe2O4/mesopore silica anchored to guanidine nanocomposite as a catalyst for synthesis of 4H-chromenes under ultrasonic irradiation,” J. Compos. Compd., vol. 3, no. 7, pp. 84–90, 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Kavosi, A. Navaee, and A. Salimi, “Amplified fluorescence resonance energy transfer sensing of prostate specific antigen based on aggregation of CdTe QDs/antibody and aptamer decorated of AuNPs-PAMAM dendrimer,” J. Lumin., vol. 204, pp. 368–374, 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Sharifianjazi et al., “Biosensors and nanotechnology for cancer diagnosis (lung and bronchus, breast, prostate, and colon): a systematic review.,” Biomed. Mater., vol. 17, no. 1, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J.-H. Zhang, M. Liu, F. Zhou, H.-L. Yan, and Y.-G. Zhou, “Homogeneous Electrochemical Immunoassay Using an Aggregation-Collision Strategy for Alpha-Fetoprotein Detection.,” Anal. Chem., vol. 95, no. 5, pp. 3045–3053, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Thenrajan and J. Wilson, “Biosensors for cancer theranostics,” Biosens. Bioelectron. X, vol. 12, p. 100232, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Kumar et al., “Effect of Brownian motion on reduced agglomeration of nanostructured metal oxide towards development of efficient cancer biosensor,” Biosens. Bioelectron., vol. 102, pp. 247–255, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Thevendran et al., “Reverse Electrochemical Sensing of FLT3-ITD Mutations in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Using Gold Sputtered ZnO-Nanorod Configured DNA Biosensors,” Biosensors, vol. 12, no. 3. 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Ratajczak, B. E. Krazinski, A. E. Kowalczyk, B. Dworakowska, S. Jakiela, and M. Stobiecka, “Optical Biosensing System for the Detection of Survivin mRNA in Colorectal Cancer Cells Using a Graphene Oxide Carrier-Bound Oligonucleotide Molecular Beacon.,” Nanomater. (Basel, Switzerland), vol. 8, no. 7, Jul. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Jinqi Deng, Shuai Zhao,Yuan Liu, Chao Liu, and Jiashu Sun ‘’Nanosensors for Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases’’ ,2019. [CrossRef]

- K . Yadav , Rahul Deo Yadav , Heena Tabassum ,” Recent Developments in Nanotechnology-Based Biosensors for the Diagnosis of Coronavirus’’ ,Sarita Malti Arya3 2023. [CrossRef]

- Shawky SM, Bald D, Azzazy HM” Direct detection of unamplifed hepatitis C virus RNA using unmodifed gold nanoparticles’’. Clin Biochem 43(13–14):1163–1168, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Pramanik A, Gao Y, Patibandla S, Mitra D, McCandless MG, Fassero LA et al “The rapid diagnosis and efective inhibition of coronavirus using spike antibody attached gold nanoparticles”. Nanoscale Advances 3(6):1588–15,2021. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed SR, Nagy É, Neethirajan S” Self-assembled star-shaped chiroplasmonic gold nanoparticles for an ultrasensitive chiro-immunosensor for viruses.” RSC Adv 7(65):40849–40857, 2017 . [CrossRef]

- Teengam P, Siangproh W, Tuantranont A, Vilaivan T, Chailapakul O, Henry CS “Multiplex paper-based colorimetric DNA sensor using pyrrolidinyl peptide nucleic acid-induced AgNPs aggregation for detecting MERS-CoV, MTB, and HPV oligonucleotides’’. Anal Chem 89(10):5428–543,2017. [CrossRef]

- Bromberg L, Raduyk S, Hatton TA “Functional magnetic nanoparticles for biodefense and biological threat monitoring and surveillance”. Anal Chem 81(14):5637–5645,2009 . [CrossRef]

- Shanmukh S, Jones L, Driskell J, Zhao Y, Dluhy R, Tripp RA “Rapid and sensitive detection of respiratory virus molecular signatures using a silver nanorod array SERS substrate”. Nano Lett 6(11):2630–2636,2006. [CrossRef]

- Bui, M.-P. N.; Ahmed, S.; Abbas, A. “Single-Digit Pathogen and Attomolar Detection with the Naked Eye Using Liposome-Amplified Plasmonic Immunoassay”. Nano Lett.6239−6246.6239−6246,2015. [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.-P.; Ma, W.; Long, Y.-T. “Alcohol Dehydrogenase-Catalyzed Gold Nanoparticle Seed-Mediated Growth Allows Reliable Detection of Disease Biomarkers with the Naked Eye’’. Anal. Chem.,2015. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Biondi, M. J.; Feld, J. J.; Chan, W. C. W. “Clinical Validation of Quantum Dot Barcode Diagnostic Technology”. ACS Nano , 10, 4742−4753,2016. [CrossRef]

- Ciftci, S.; Canovas, R.; Neumann, F.; Paulraj, T.; Nilsson, M.; Crespo, G. A.; Madaboosi, N. “The sweet detection of rolling circle amplification: Glucose-based electrochemical genosensor for the detection of viral nucleic acid’’. Biosens. Bioelectron. 151, 112002,2020. [CrossRef]

- Kurdekar, A. D.; Avinash Chunduri, L. A.; Manohar, C. S.; Haleyurgirisetty, M. K.; Hewlett, I. K.; Venkataramaniah, K. “Streptavidin-conjugated gold nanoclusters as ultrasensitive fluorescent sensors for early diagnosis of HIV infection”. Sci. Adv.4, eaar6280,2018. [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Cheng, Z.; Yu, J.; Choo, P.; Chen, L.; Choo, J. “A SERS-based lateral flow assay biosensor for highly sensitive detection of HIV-1 DNA”. Biosens. Bioelectron.78, 530−537, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Huang, J.; Yu, B.; Liu, Y.; You, T. ANovel ‘’Electrochemiluminescence Immunosensor for the Analysis of HIV-1 p24 Antigen Based on P-RGO@Au@Ru-SiO2 Composite”. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 24438−24445 ,2015. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Bai, W.; Dong, C.; Guo, R.; Liu, Z.” An ultrasensitive electrochemical DNA biosensor based on graphene/Au nanorod/polythionine for human papillomavirus DNA detection”. Biosens.Bioelectron. 68, 442−446,2015. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qin, Z.; Boulware, D. R.; Pritt, B. S.; Sloan, L. M.; Gonzalez, I. J.; Bell, D.; Rees-Channer, R. R.; Chiodini, P.; Chan, W. ́C. W.; Bischof, J. C. “Thermal Contrast Amplification Reader Yielding 8-Fold Analytical Improvement for Disease Detection with Lateral Flow Assays”. Anal. Chem.88, 11774−11782, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, M.; Srivastava, N.; Mishra, P.; Malhotra, B.D.” Prospects of nanomaterials-enabled biosensors for COVID-19 detection”.Sci. Total Environ., 754, 142363,2020. [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, F.N.; Curreli, M.; Olson, C.A.; Liao, H.-I.; Sun, R.; Roberts, R.W.; Cote, R.J.; Thompson, M.E.; Zhou, C.“ Importance ofControlling Nanotube Density for Highly Sensitive and Reliable Biosensors Functional in Physiological Conditions”. ACS Nano, 4,6914–6922,2010. [CrossRef]

- Naumih M. Noah and Peter M. Ndangili . “Current Trends of Nanobiosensors for Point-of-Care Diagnostics”,2019. [CrossRef]

- Baptista P PE, Eaton P, Doria G, Miranda A, Gomes I, Quaresma P, Franco R “Gold nanoparticles for the development of clinical diagnosis methods”. Anal Bioanal Chem 391:943–50,2008. [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, R. D. Jayant, S. Tiwari, A. Vashist, and M. Nair, “Nano-biosensors to detect beta-amyloid for Alzheimer’s disease management,” Biosensors and Bioelectronics, vol. 80, pp. 273–287, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- G. Pilvenyte et al., “Molecularly imprinted polymers for the recognition of biomarkers of certain neurodegenerative diseases,” J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal., vol. 228, p. 115343, 2023.

- B. B. Apaydın, T. Çamoğlu, Z. C. Canbek Özdil, D. Gezen-Ak, D. Ege, and M. Gülsoy, “Chitosan-enhanced sensitivity of mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUA)- capped gold nanorod based localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) biosensor for detection of alpha-synuclein oligomer biomarker in parkinson’s disease.,” Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem., vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 150–163, Feb. 2025.

- Z. Aghili, N. Nasirizadeh, A. Divsalar, S. Shoeibi, and P. Yaghmaei, “A highly sensitive miR-195 nanobiosensor for early detection of Parkinson’s disease.,” Artif. cells, nanomedicine, Biotechnol., vol. 46, no. sup1, pp. 32–40, 2018.

- L. N. Rizalputri et al., “Facile and controllable synthesis of monodisperse gold nanoparticle bipyramid for electrochemical dopamine sensor,” Nanotechnology, vol. 34, no. 5, p. 55502, 2023.

- N. Chauhan, S. Pareek, W. Rosario, R. Rawal, and U. Jain, “An insight into the state of nanotechnology-based electrochemical biosensors for PCOS detection,” Analytical Biochemistry, vol. 687, p. 115412, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Neethirajan, X. Weng, A. Tah, J. O. Cordero, and K. V. Ragavan, “Nano-biosensor platforms for detecting food allergens – New trends,” Sensing and Bio-Sensing Research, vol. 18, pp. 13–30, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ma et al., “Nanomaterials in the diagnosis and treatment of ophthalmic diseases,” Nano Today, vol. 54, p. 102117, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. Khosravi Ardakani, M. Gerami, M. Chashmpoosh, N. Omidifar, and A. Gholami, “Recent Progress in Nanobiosensors for Precise Detection of Blood Glucose Level,” Biochemistry Research International, vol. 2022, p. 2964705, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Nan Fu Chiu, Ying Hao Wang, and Chen Yu Chen, “Clinical Application for Screening Down’s Syndrome by Using Carboxylated Graphene Oxide-Based Surface Plasmon Resonance Aptasensors,” International journal of nanomedicine, vol. Volume 15, pp. 8131–8149, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yi Zhao, Mingju Pu, Yanan Wang, Liangmin Yu, Xinyu Song, and Zhiyu He, “Application of nanotechnology in acute kidney injury: From diagnosis to therapeutic implications,” Journal of Controlled Release, vol. 336, pp. 233–251, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).