Submitted:

20 February 2025

Posted:

21 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

With portable electronics and new-energy vehicles booming, the demand for high-performance energy storage devices has skyrocketed. Supercapacitor separators are thus vital. Traditional ones such as polyolefins and non-woven fabrics have limitations, while cellulose and its derivatives, with low cost, good hydrophilicity, and strong chemical stability, are potential alternatives. This study used regenerated cellulose Lyocell fibers. Through fiber treatment, refining, and in situ deposition, a composite regenerated cellulose separator (NFRC-Ba) with nano-barium sulfate was made. Its physical, ionic, and charge–discharge properties were tested. The results show that NFRC-Ba excels in terms of mechanical strength, porosity, hydrophilicity, and thermal stability. Compared with the commercial NKK30AC-100 separator, it has better ionic conductivity, better ion-transport ability, a higher specific capacitance, better capacitance retention, and good cycle durability. It also performs stably from -40°C to 100°C. With a simple and low-cost preparation process, NFRC-Ba could be a commercial separator for advanced supercapacitors.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

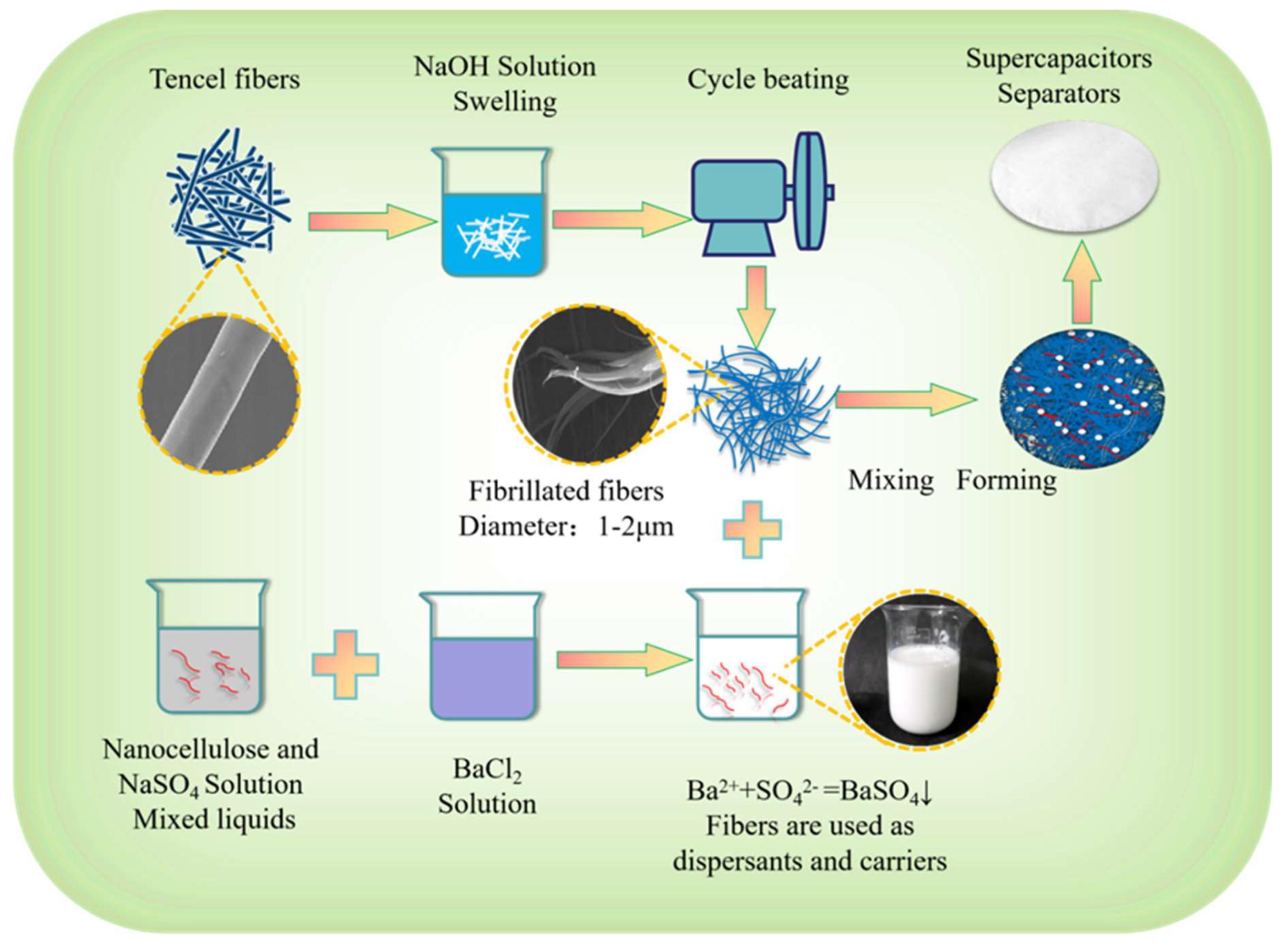

2.2. Preparation of Composite Regenerated Cellulose Separator

- Immerse Lyocell fibers (CLY) in a 1 wt% sodium hydroxide solution for 2 hours to enable the fibers to fully absorb the solution and swell, thereby weakening the hydrogen bond binding NFRC-Ba between the fibers. Subsequently, prepare the treated CLY into a fiber slurry with a concentration of 10 wt% and feed it into a refiner for a meticulous refining treatment of 80,000 revolutions. Through this operation, the fibers can be fully fibrillated, ultimately separating into nanofibrillated Lyocell fibers (MCLY) with diameters ranging from 1 to 2 μm.

- Carefully prepare a 1 mol/L sodium sulfate solution and a 1 mol/L barium chloride solution. Add the sodium sulfate solution to the 3 wt% NFC mixture at a ratio of 5:5. Then, use an ultrasonic disperser to ensure that the NFC is fully dispersed in the liquid. After that, mix the two solutions uniformly according to a molar ratio of sulfate ions (SO42-) to barium ions (Ba2+) of 1:1, so as to carry out in situ nano-barium sulfate precipitation within the NFC system and successfully prepare an NFC-BA mixture.

- Thoroughly mix MCLY and NFC-Ba at a precise ratio of 7:3 and then prepare a homogeneous liquid with a fiber concentration of 0.3 wt%. Utilize a special papermaking machine to produce a composite regenerated cellulose separator paper (NFNFRC-Ba) with a basis weight of 13 g/m². Meanwhile, use only MCLY as the raw material to prepare a cellulose separator paper (FNFRC-Ba) with the same basis weight of 13 g/m² as the control sample. The detailed preparation process of the composite regenerated cellulose separator paper (NFNFRC-Ba ) is shown in Figure 1.

3. Results

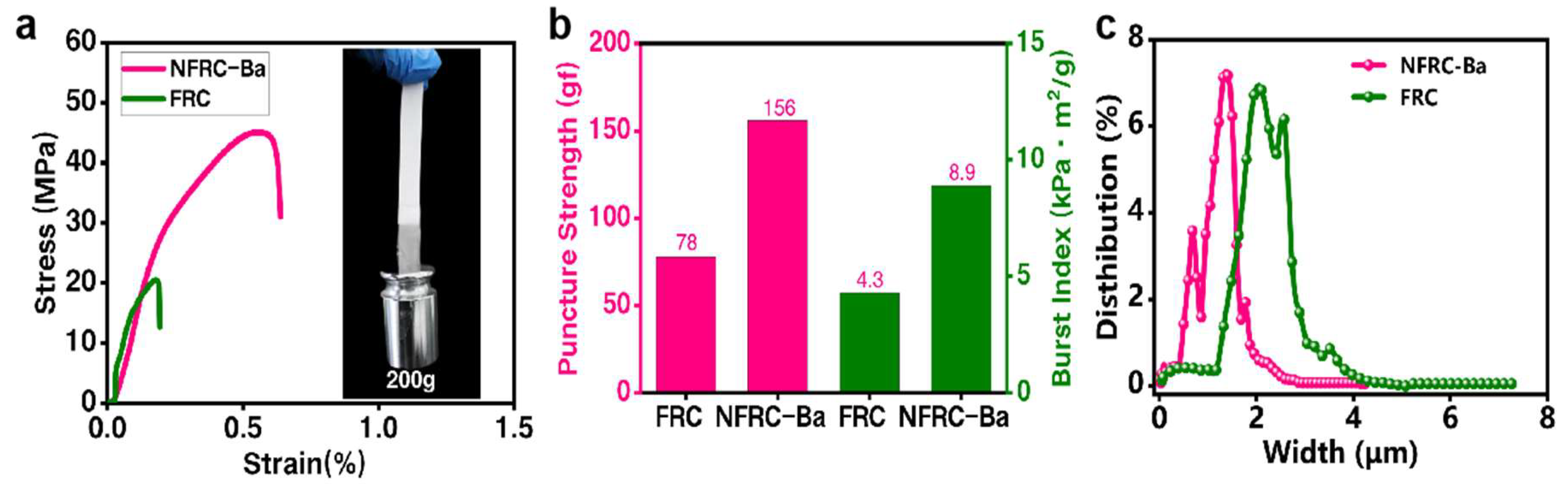

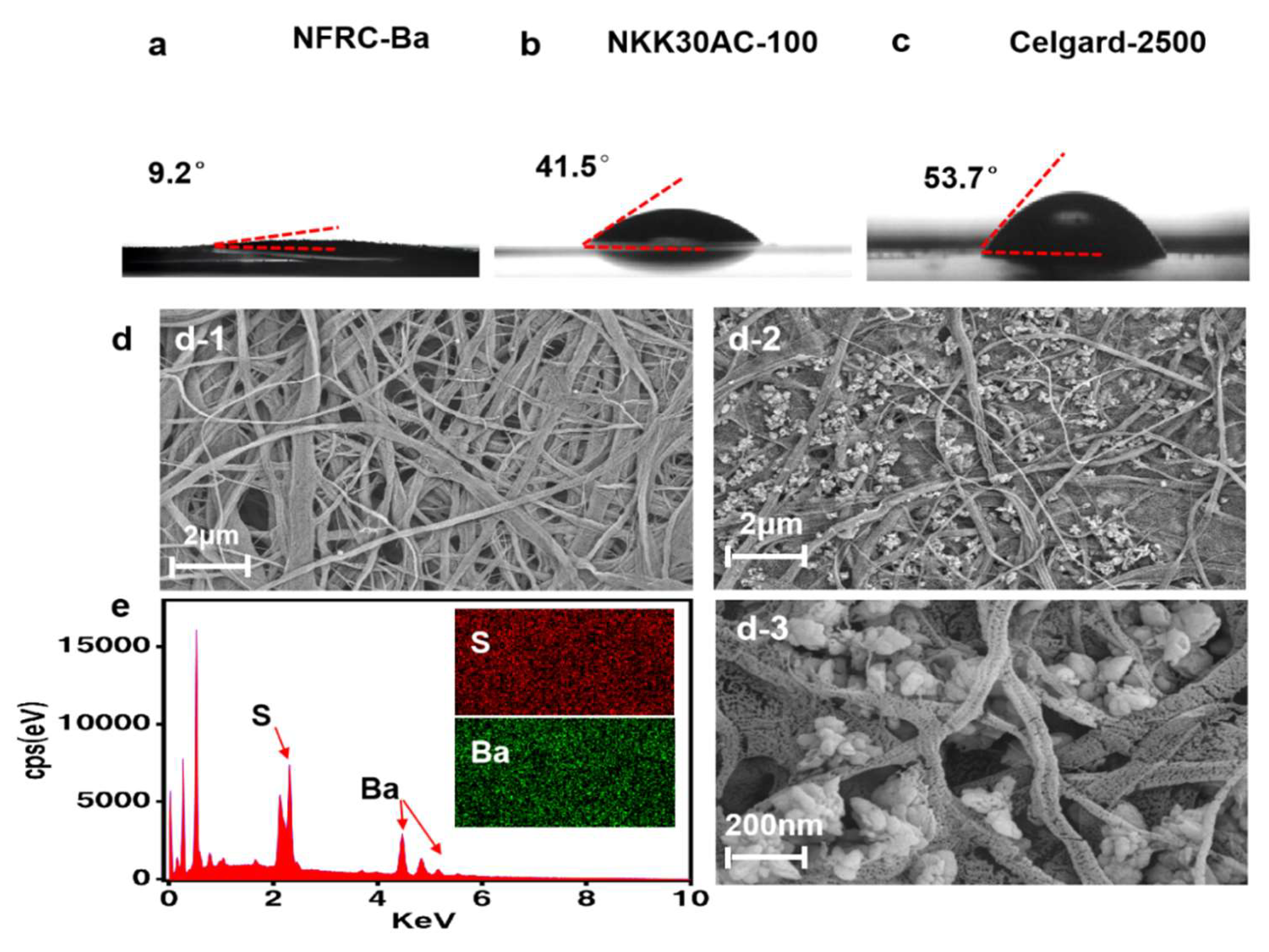

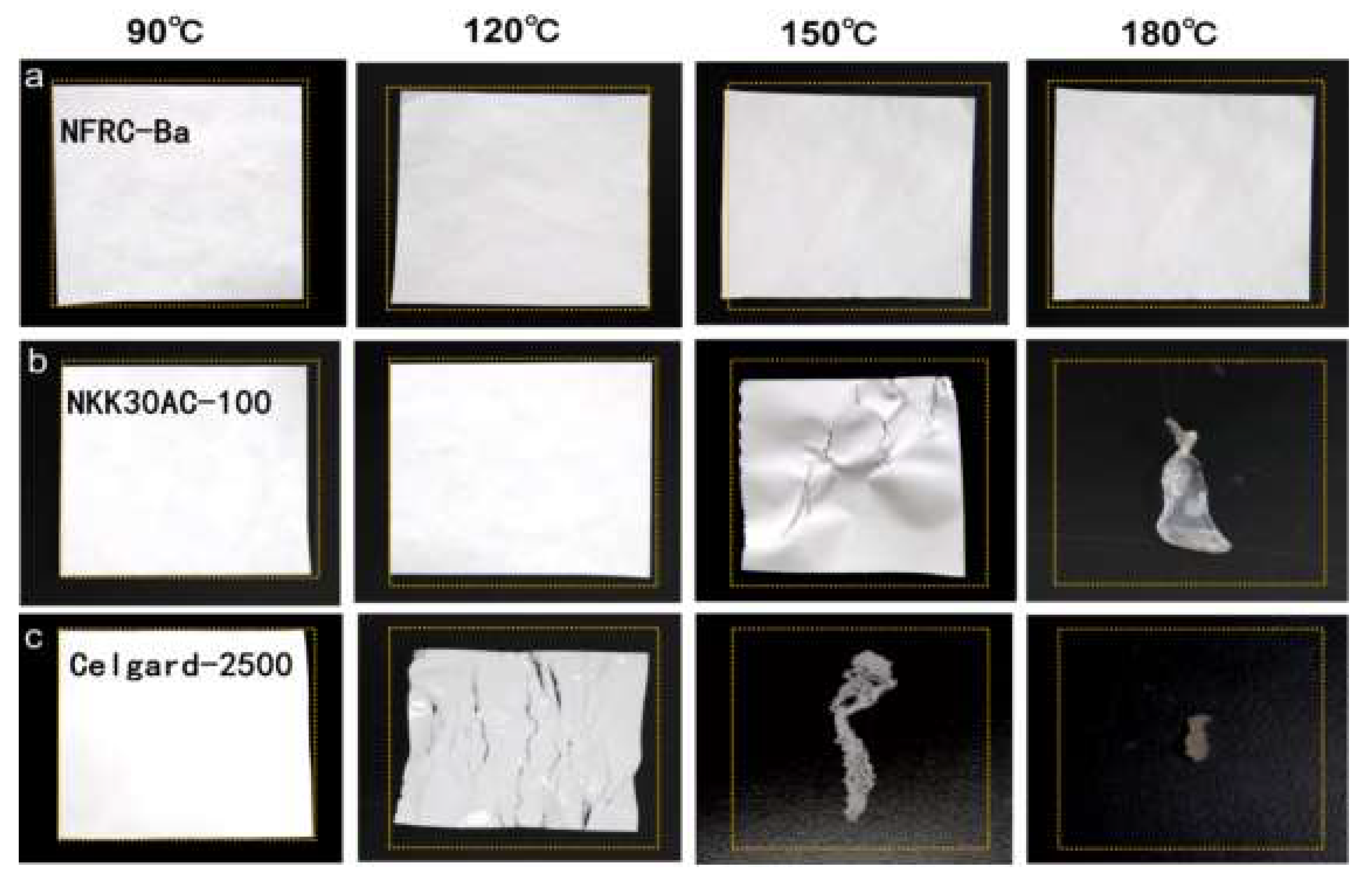

3.1. Physical Properties of the NFRC-Ba

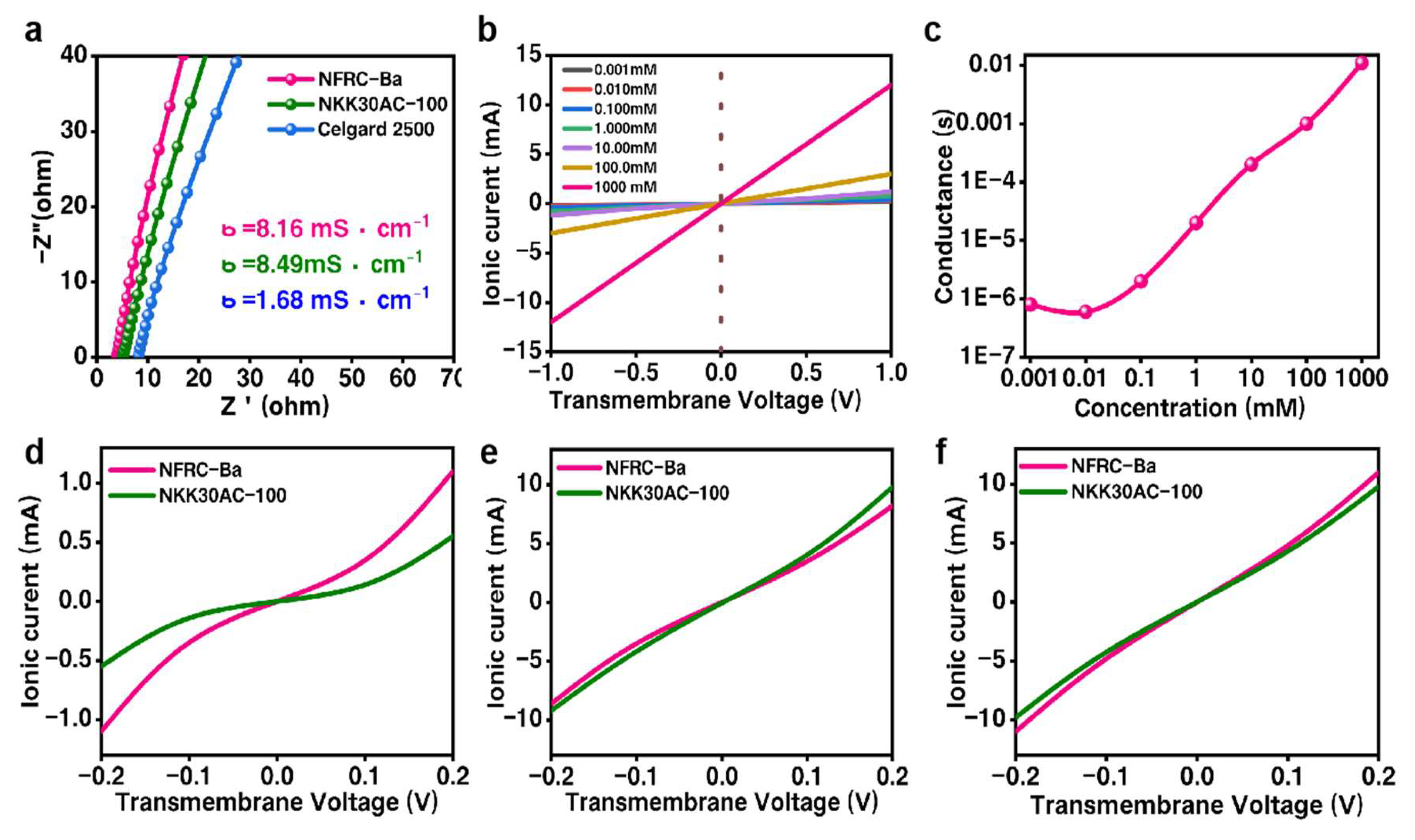

3.2. Ionic Property of the NFRC-Ba Separator

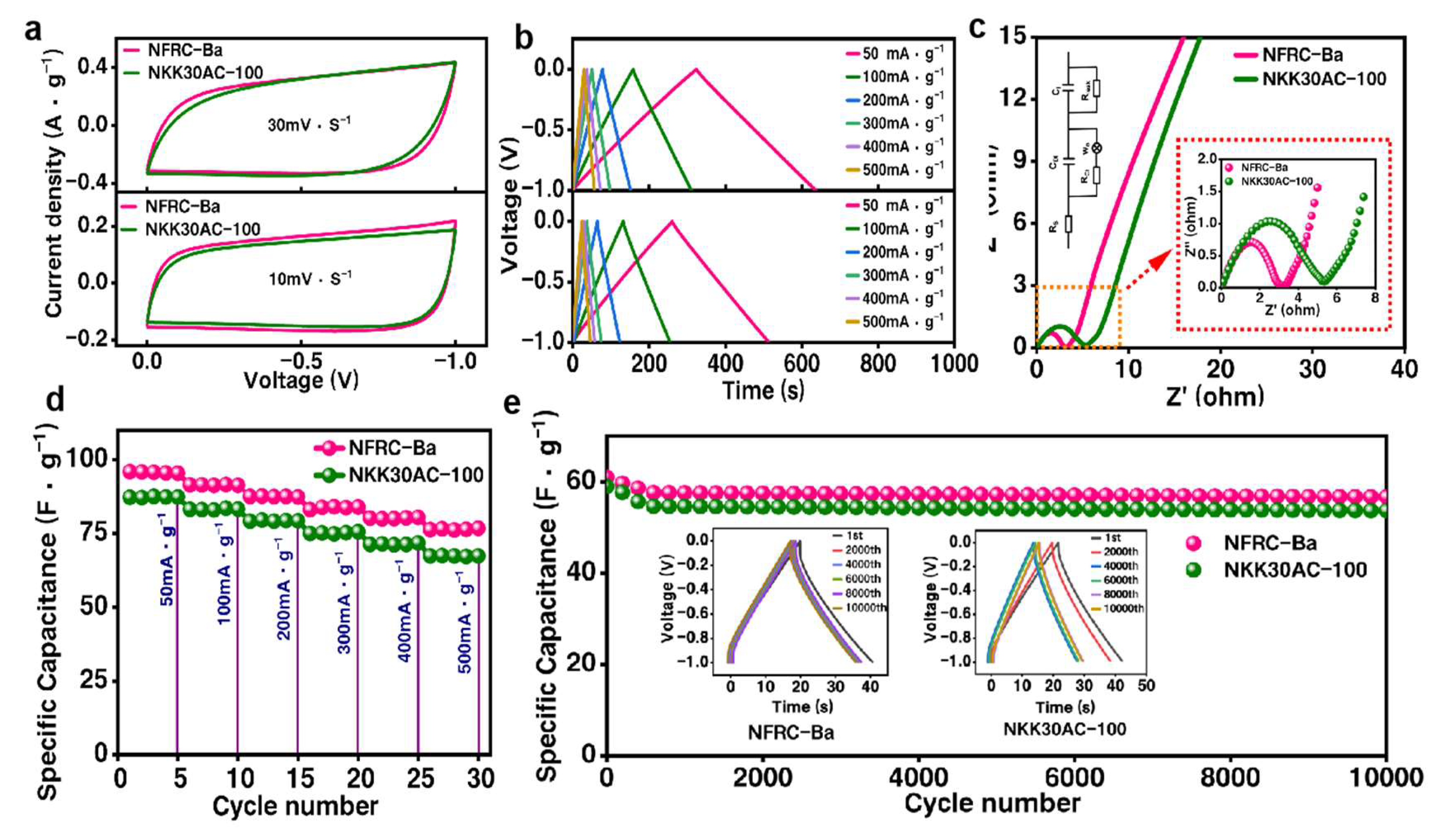

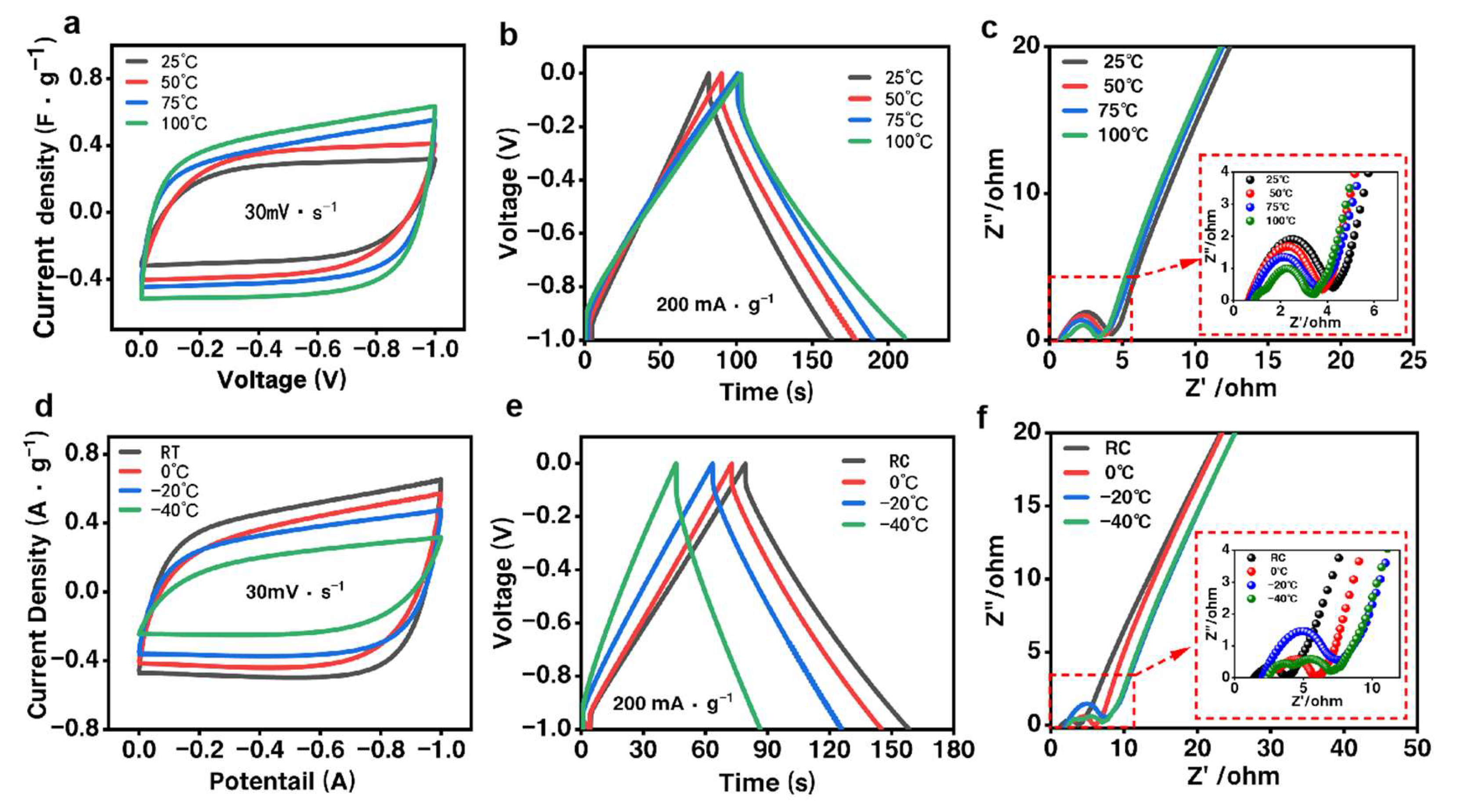

3.3. Charge–Discharge Performance of the NFRC-Ba Separator

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kwade, A.; Haselrieder, W.; Leithoff, R.; Modlinger, A.; Dietrich, F.; Droeder, K. Current status and challenges for automotive battery production technologies. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, Z.P.; Banham, D.; Ye, S.; Hintennach, A.; Lu, J.; Fowler, M.; Chen, Z. Batteries and fuel cells for emerging electric vehicle markets. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, P.; Gogotsi, Y. Materials for electrochemical capacitors. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 845–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Chand, P. Supercapacitor and electrochemical techniques: A brief review. Results Chem. 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saher, S.; Johnston, S.; Esther-Kelvin, R.; Pringle, J.M.; MacFarlane, D.R.; Matuszek, K. Trimodal thermal energy storage material for renewable energy applications. Nature 2024, 636, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Lin, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, K.; Hu, H.; Dai, S. Electrode Materials, Structural Design, and Storage Mechanisms in Hybrid Supercapacitors. Molecules 2023, 28, 6432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; He, J.; Duan, C.; Wang, G.; Liang, B. Recent advance in electrochemically activated supercapacitors: Activation mechanisms, electrode materials and prospects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrascosa, A.; Sánchez, J.S.; Morán-Aguilar, M.G.; Gabriel, G.; Vilaseca, F. Advanced Flexible Wearable Electronics from Hybrid Nanocomposites Based on Cellulose Nanofibers, PEDOT:PSS and Reduced Graphene Oxide. Polymers 2024, 16, 3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; He, R.; Li, M.; Chee, M.O.L.; Dong, P.; Lu, J. Functionalized separator for next-generation batteries. Mater. Today 2020, 41, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagadec, M.F.; Zahn, R.; Wood, V. Characterization and performance evaluation of lithium-ion battery separators. Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Bliznakov, S.; Bonville, L.; Oljaca, M.; Maric, R. A Review of Nonaqueous Electrolytes, Binders, and Separators for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2022, 5, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Fu, W.; Jhulki, S.; Chen, L.; Narla, A.; Sun, Z.; Wang, F.; Magasinski, A.; Yushin, G. Heat-resistant Al2O3 nanowire-polyetherimide separator for safer and faster lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 142, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Fu, W.; Jhulki, S.; Chen, L.; Narla, A.; Sun, Z.; Wang, F.; Magasinski, A.; Yushin, G. Heat-resistant Al2O3 nanowire-polyetherimide separator for safer and faster lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 142, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Yuan, B.; Guang, Z.; Chen, D.; Li, Q.; Dong, L.; Ji, Y.; Dong, Y.; Han, J.; He, W. Recent progress in thin separators for upgraded lithium ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 41, 805–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-H.; Wang, P.; Gao, Z.; Li, X.; Cui, W.; Li, R.; Ramakrishna, S.; Zhang, J.; Long, Y.-Z. Review on electrospinning anode and separators for lithium ion batteries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Ning, D.; Zhou, D.; Gao, J.; Ni, J.; Zhang, G.; Gao, R.; Wu, W.; Wang, J.; Li, Y. Construction of flexible asymmetric composite polymer electrolytes for high-voltage lithium metal batteries with superior performance. Nano Energy 2024, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Chen, B.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, C.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Dong, Q.; Xue, G.; Chen, D.; et al. Polyfluorinated crosslinker-based solid polymer electrolytes for long-cycling 4.5 V lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Xu, C.; Wang, J.; Fan, Z.; Xu, L.; He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ding, B.; Zhang, X. Non-Flammable fluorinated gel polymer electrolyte for safe lithium metal batteries in harsh environments. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2024, 683, 984–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hu, H.; Yang, J.; He, Z.; Zhu, G.; Wen, C. The Application of Porous Carbon Derived from Furfural Residue as the Electrode Material in Supercapacitors. Polymers 2024, 16, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wu, D.; Wu, J.; Dong, L.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, X. Flexible, High-Wettability and Fire-Resistant Separators Based on Hydroxyapatite Nanowires for Advanced Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chu, F.; Li, D.; Si, M.; Liu, M.; Wu, F. In Situ Polymerized Fluorine-Free Ether Gel Polymer Electrolyte with Stable Interface for High-Voltage Lithium Metal Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Bae, J. Recent Advancements in Fabrication, Separation, and Purification of Hierarchically Porous Polymer Membranes and Their Applications in Next-Generation Electrochemical Energy Storage Devices. Polymers 2024, 16, 3269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Tian, T.; Shen, B.; Peng, Y.; Song, Y.; Jiang, B.; Lu, L.; Yao, H.; Yu, S. Sustainable Separators for High-Performance Lithium Ion Batteries Enabled by Chemical Modifications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, J. Highly Stable Lithium–Sulfur Batteries Based on Laponite Nanosheet-Coated Celgard Separators. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Han, Q.; Su, M.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, H. Vapor-induced phase inversion of poly (m-phenylene isophthalamide) modified polyethylene separator for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 429, 132429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schadeck, U.; Kyrgyzbaev, K.; Zettl, H.; Gerdes, T.; Moos, R. Flexible, Heat-Resistant, and Flame-Retardant Glass Fiber Nonwoven/Glass Platelet Composite Separator for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energies 2018, 11, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsia, T.-N.; Lu, H.-C.; Hsueh, Y.-C.; Kumar, S.R.; Yen, C.-S.; Yang, C.-C.; Lue, S.J. Superdry poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) coating on a lithium anode as a protective layer and separator for a high-performance lithium-oxygen battery. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 626, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zhang, D.; Gu, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, X.; Qin, J.; Wu, Z. Manipulating Crystallographic Orientation of Zinc Deposition for Dendrite-free Zinc Ion Batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2101299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Arifeen, W.U.; Choi, J.; Yoo, K.; Ko, T. Surface-modified electrospun polyacrylonitrile nano-membrane for a lithium-ion battery separator based on phase separation mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 398, 125646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; He, Q.; Li, Z.; Meng, J.; Hong, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, X.; Mai, L. A robust electrospun separator modified with in situ grown metal-organic frameworks for lithium-sulfur batteries. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, N.; Aziz, K.; Javed, M.S.; Tariq, R.; Kanwal, N.; Raza, W.; Sarfraz, M.; Khan, S.; Ismail, M.A.; Akkinepally, B.; et al. Advancements in separator design for supercapacitor technology: A review of characteristics, manufacturing processes, limitations, and emerging trends. J. Energy Storage 2025, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Tang, Q.; Wu, J.; Lin, Y.; Fan, L.; Huang, M.; Lin, J.; Li, Y.; Yu, F. Using eggshell membrane as a separator in supercapacitor. J. Power Sources 2012, 206, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, L.; Griggs, J.A.; Janorkar, A.V.; Xu, X.; Chandran, R.; Mei, H.; Nobles, K.P.; Yang, S.; Alberto, L.; Duan, Y. Preparation and optimization of an eggshell membrane-based biomaterial for GTR applications. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; He, J.; Gao, Z.; Li, X. Converting eggs to flexible, all-solid supercapacitors. Nano Energy 2019, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S.; Kim, B.; Kim, C.; Tamwattana, O.; Park, H.; Kim, J.; Lee, D.; Kang, K. Permselective metal–organic framework gel membrane enables long-life cycling of rechargeable organic batteries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 16, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yu, H.; Lee, S.-Y.; Wei, T.; Li, J.; Fan, Z. Nanocellulose: a promising nanomaterial for advanced electrochemical energy storage. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 2837–2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doobary, S.; Apostolopoulou-Kalkavoura, V.; Mathew, A.P.; Olofsson, B. Nanocellulose: New horizons in organic chemistry and beyond. Chem 2024, 10, 3279–3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shafai, N.M.; Ibrahim, M.M.; Abdelfatah, M.; Ramadan, M.S.; El-Mehasseb, I.M. Synthesis, characterization, and cytotoxicity of self-assembly of hybrid nanocomposite modified membrane of carboxymethyl cellulose/graphene oxide for photocatalytic antifouling, energy storage, and supercapacitors application. Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, R.; Rebelo, R.C.; Coelho, J.F.J.; Serra, A.C. Novel thermally regenerated flexible cellulose-based films. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2024, 82, 1813–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yin, H.; Liu, F.; Abdiryim, T.; Xu, F.; You, J.; Chen, J.; Jing, X.; Li, Y.; Su, M.; et al. Stretchable, self-healing, adhesive and anti-freezing ionic conductive cellulose-based hydrogels for flexible supercapacitors and sensors. Cellulose 2024, 31, 11015–11033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Yang, J.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Hu, J. Characterization of cellulose-nanofiber-modified fibrillated lyocell fiber separator. BioResources 2022, 17, 4689–4704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Yang, G.; Edgar, K.J.; Zhang, H.; Shao, H. Effect of lyocell fiber cross-sectional shape on structure and properties of lyocell/PLA composites. J. Polym. Eng. 2022, 42, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiwen, W.; Jian, H.; Jin, L. Preparation Ultra-fine Fibrillated Lyocell Fiber and Its Application in Battery Separator. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2011, 6, 4999–5004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, J.; Chen, L.; Long, J.; Hu, J.; Meng, L. Effect of fibrillated fiber morphology on properties of paper-based separators for lithium-ion battery applications. J. Power Sources 2020, 482, 228899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Yang, X.; Tang, Y. Nanocellulose-based electrodes and separator toward sustainable and flexible all-solid-state supercapacitor. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 228, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; M. N., P.; Zhai, J.-G.; Song, J.-I. High-throughput extraction of cellulose nanofibers from Imperata cylindrica grass for advanced bio composites. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 284, 138111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, B.d.F.; Santana, L.R.; Oliveira, R.M.; Filho, A.V.; Carreno, N.L.V.; Wolke, S.I.; da Silva, R.; Fajardo, A.R.; Dias, A.R.G.; Zavareze, E.d.R. Cellulose, cellulose nanofibers, and cellulose acetate from Butia fruits (Butia odorata): Chemical, morphological, structural, and thermal properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 281, 136151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Jiang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, S.; Huang, L. Cellulose nanofiber-based hybrid hydrogel electrode with superhydrophilicity enabling flexible high energy density supercapacitor and multifunctional sensors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 134003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Liu, X.-T.; Tao, S.-Q.; Yao, C.-L. Cellulose nanofiber/MXene (Ti3C2Tx)/liquid metal film as a highly performance and flexible electrode material for supercapacitors. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 130119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Ji, X.; Yang, G.; He, M. A morphology control engineered strategy of Ti3C2T /sulfated cellulose nanofibril composite film towards high-performance flexible supercapacitor electrode. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 243, 124828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Duan, Y.; Zhao, H.; Liu, K.; Liu, Y.; Wu, M.; Lu, P. Preparation of Bio-Based Foams with a Uniform Pore Structure by Nanocellulose/Nisin/Waterborne-Polyurethane-Stabilized Pickering Emulsion. Polymers 2022, 14, 5159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wang, H.; Xu, Z.; Wang, K.; Ge, M.; Gan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Chen, S. Thermal-Responsive and Fire-Resistant Materials for High-Safety Lithium-Ion Batteries. Small 2021, 17, 2103679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, D.; Zhang, L.; Xu, D.-M.; Qiao, F.; Yao, X.; Lin, H.; Liu, W.; Pang, L.-X.; Hussain, F.; Darwish, M.A.; et al. Novel Method to Achieve Temperature-Stable Microwave Dielectric Ceramics: A Case in the Fergusonite-Structured NdNbO4 System. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 19129–19136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.; Chen, Z.; Bai, S.; Zhang, Y. Highly reversible Zn anode enabled by porous BaSO4 coating with wide band gap and high dielectric constant. J. Power Sources 2023, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Wu, J.; Yu, H.-P.; Xie, S.; Li, D.; Wang, Z.; Li, H. Reversible Li plating regulation on graphite anode through a barium sulfate nanofibers-based dielectric separator for fast charging and high-safety lithium-ion battery. J. Energy Chem. 2024, 101, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.S.; Yan, Q.; Holoubek, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, H.; Patterson, N.; Petrova, V.; Liu, H.; Liu, P. Draining Over Blocking: Nano-Composite Janus Separators for Mitigating Internal Shorting of Lithium Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e1906836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Kong, Q.; Zhang, C.; Pang, S.; Yue, L.; Wang, X.; Yao, J.; Cui, G. Renewable and Superior Thermal-Resistant Cellulose-Based Composite Nonwoven as Lithium-Ion Battery Separator. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 5, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Min, Y. Electrospun polyimide nanofiber-based separators containing carboxyl groups for lithium-ion batteries. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Wen, K.; Chen, D.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Feng, C.; Han, Y.; Han, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, C.; et al. Composite Separators for Robust High Rate Lithium Ion Batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2101420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Cai, Q.; Dong, A.; Yang, D.; Zhao, D. Hierarchically Porous Silica Membrane as Separator for High-Performance Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2021, 34, 2107957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Zhou, X.; Li, T.; Zhao, W.; Zhou, D.; Yang, D.; Wu, T.; Xu, Y. Regulating Built-in Polar States via Atomic Self-Hybridization for Fast Ion Diffusion Kinetics in Potassium Ion Batteries†. Chin. J. Chem. 2024, 42, 2589–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, S.; Wu, F.; Chen, H.; Chen, W.W.; Zhao, W.; Kang, K.; Guo, R.; Sun, Y.; Zhai, L.; et al. Hubbard Gap Closure-Induced Dual-Redox Li-Storage Mechanism as the Origin of Anomalously High Capacity and Fast Ion Diffusivity in MOFs-Like Polyoxometalates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2024, 64, e202416735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Turcheniuk, K.; Fu, W.; Yang, Y.; Liu, M.; Yushin, G. Scalable, safe, high-rate supercapacitor separators based on the Al2O3 nanowire Polyvinyl butyral nonwoven membranes. Nano Energy 2020, 71, 104627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahn, R.; Lagadec, M.F.; Hess, M.; Wood, V. Improving Ionic Conductivity and Lithium-Ion Transference Number in Lithium-Ion Battery Separators. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 32637–32642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Lan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, X.; Zhao, L.; Wu, X.; Gao, H. Mechanisms by Which Exogenous Substances Enhance Plant Salt Tolerance through the Modulation of Ion Membrane Transport and Reactive Oxygen Species Metabolism. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Chen, H.-H.; Chu, C.-W.; Yeh, L.-H. Massively Enhanced Charge Selectivity, Ion Transport, and Osmotic Energy Conversion by Antiswelling Nanoconfined Hydrogels. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 11756–11762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gojgić, J.; Petrović, M.; Jugović, B.; Jokić, B.; Grgur, B.; Gvozdenović, M. Electrochemical and Electrical Performances of High Energy Storage Polyaniline Electrode with Supercapattery Behavior. Polymers 2022, 14, 5365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.G.; Jeong, J.J.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.-S. Ion-Conducting Robust Cross-Linked Organic/Inorganic Polymer Composite as Effective Binder for Electrode of Electrochemical Capacitor. Polymers 2022, 14, 5174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).