1. Introduction

Transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS) is a noninvasive electric stimulation technique believed to affect brain functioning by neuromodulation of intrinsic rhythmic activity [

1,

2]. TACS-induced neural entrainment would promote synchronization of phasic neural oscillations at specific frequencies, with effects on cognitive performance and brain function [

3]. Recent times have indeed seen a growing interest in employing tACS in the field of cognitive neuroscience both in health and disease. In particular, a growing number of studies in recent years have employed tACS both to demonstrate the causal relationship between neural oscillations and working memory (WM) performance, and to improve WM functioning in a clinical setting and in the elderly population with WM deficits [

4,

5].

Visuospatial working memory (VSWM) is defined as the capacity to maintain and manipulate visuospatial information across a brief delay. Research on the cognitive neuroscience of VSWM has revealed a network of brain regions involved in VSWM maintenance and manipulation including dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), parietal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex and frontal eye fields. Particularly relevant were studies evaluating the influence on DLPFC activity of VSWM memory retention load employing the spatial capacity delayed response task (SCDRT; [

6,

7]).

1.1. WM and Neural Oscillations

Oscillatory activity is thought to crucially support the maintenance of information in WM, with distinct functional roles for theta (θ: 4-7 Hz), alpha (α: 8-12 Hz), and gamma (γ: 30-80 Hz) frequencies: Specifically, γ-band oscillations would be involved in the maintenance of WM information, α-band activity would reflect active inhibition of task-irrelevant information, whereas θ-band oscillations would underlie the organization of sequentially ordered WM items [

8]. It has also been proposed that coordination and maintenance of representational objects in visual WM requires intra-areal synchrony between α, β and γ frequency bands in the fronto-parietal areas and in the visual areas [

9].

With regards to VSWM, studies have reported associations of oscillatory patterns to spatial short-term memory, in particular, mental rotation, especially in the γ-band [

10,

11], but also in the beta band (β: 13–29 Hz) [

12]. Of relevance was a review concluding that, in working memory tasks, γ and β bands address different processing stages. The γ frequency would be prevalent during the presentation of the item to be held in memory, while the β band would be prominent during the maintenance period [

13].

In fact, it has been proposed that the bottom-up or perceptually driven processes are mediated by local γ frequency, whereas top-down processes would involve long-distant oscillations in the β, α and θ bands [

14]. The γ frequency band has also been linked to perceptual binding, that is, the process whereby the sensory stimuli are combined together in order to create a meaningful and unitary percept. Finally, a recent high-density resting state EEG study by our research group found that functional connectivity in the γ band in nodes of the left DAN (superior frontal-intraparietal network) predicted performance of typically developing children and adolescents on the Rey–Osterrieth complex figure test (ROCFT), that is used to assess visuospatial memory and visuoconstructive abilities [

15].

1.2. Neuromodulation and WM

Several studies employing transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) have investigated the effects on brain regions specifically associated with WM. In a study applying anodal tDCS over the left DLPFC either during (

online stimulation) or before (

offline stimulation) execution of a n-back task, a significant improvement in digit span performance was found only for the

online active treatment, with no evidence of effect for

offline stimulation [

16].

A meta-analysis exploring the effects of tDCS and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) on DLPFC in n-back tasks in healthy and neuropsychiatric cohorts found an overall improvement in reaction times (RTs) for tDCS and rTMS, and accuracy for rTMS [

17]. A second meta-analysis compared the effects of tDCS, tACS and rTMS on mental rotation ability as a component of VSWM. Results showed a beneficial effect of anodal tDCS and tACS on mental rotation performance, and no effect of cathodal tDCS [

18]. A third meta-analysis assessed the effects of stimulation with anodal tDCS in a healthy and neuropsychiatric population, measuring RTs and accuracy in WM tasks (n-back, Sternberg task and digit span). Results revealed significant improvements in WM performance (RTs and accuracy) in healthy cohorts, but only for

offline stimulation and not for online treatment. In contrast, the reverse was true for neuropsychiatric groups, where

online stimulation was effective and

offline treatment was not [

19]. Similarly, a further recent meta-analysis indicated greater improvements in cognitive function after completion of tACS (

offline effects) than during tACS stimulation (

online effects) [

20]. Also relevant to mention here is evidence that γ-tACS (but not tDCS) improves WM performance at higher loads, with greater WM gains as retention load increased in a n-back task [

21].

Despite the numerous studies using a single session, little research has addressed the benefits of repeated sessions of tACS on WM performance. A study reported no effects on WM in a single session of γ-tACS on bilateral DLPFC in healthy volunteers and major depression patients. The authors concluded that a single stimulation session may not be sufficient to yield WM gains and future studies should in fact evaluate the effects of repeated stimulation sessions [

22].

A recent study tested the efficacy of repetitive tACS stimulation over four days to boost performance in a verbal memory task of in elderly healthy participants. A significant effect on WM (immediate recall) was present on days 3 and 4 of active θ-tACS over left parietal cortex, suggesting that repeated sessions are indeed required to obtain a soli performance improvement in WM tasks. Notably, the WM gains were still present at a follow-up session after one month [

23].

1.3. Aims

To our knowledge no studies have been published evaluating the effects of repetitive tACS (r-tACS) on VSWM. Based on evidence that the γ frequency band is particularly implicated in various aspects of VSWM, among which the short-term maintenance of visual and visuospatial information [

8,

9], given the role of DLPFC as main hub in the cortical network involved in VSWM maintenance and manipulation ([

6,

7], and the resting EEG evidence that γ-band connectivity in the left DAN predicts visuospatial performance in the ROCFT [

15], we selected the γ-band (40 Hz) as tACS stimulation frequency and the left DLPFC as target region of interest (ROI) for stimulation. We also opted for employing the SCDRT as well-validated task to study VSWM performance and the related DLPFC activity as a function of retention load [

6,

7], given evidence that γ -tACS improves WM performance at higher loads in a n-back task [

21]. Based on recent proof that r-tACS boosted verbal WM performance (immediate recall) starting from stimulation day 3, with long-term gains up to month [

23], we opted to evaluate the short and long-term efficacy of a three day active r-tACS intervention protocol. Given the inconsistencies about the efficacy of online vs. offline stimulation on cognitive performance, we decided to test both online and offline effects within each session.

Main aim of the present study was therefore to evaluate the short-term efficacy of repeated γ-tACS over the left DLPFC to improve VSWM performance in healthy young adults as a function of stimulation protocol (active vs. passive sham), session of stimulation (day 1 to 3), session block (before, during and after tACS) and WM retention load (1 to 7 stimuli). Second aim of the study was to evaluate possible long-term effects of active repetitive γ-tACS by evaluating VSWM gains with a follow-up session after two weeks.

1.4. Hypotheses

A first experimental prediction was that the active r-tACS intervention would significantly improve VSWM performance (accuracy and/or response speed) relative to the passive sham tACS treatment by a progressive boosting of VSWM over the three stimulation sessions, as reported by a recent verbal WM study [

23].

A second experimental prediction was that the active r-tACS induced VSWM performance improvement relative to the sham intervention would be significantly greater in the post-stimulation block (

offline effect) relative to the stimulation block (

online effect), consistently with recent literature [

19,

20].

A third experimental hypothesis was that the active r-tACS-induced performance gains would concern at a greater extent higher retention loads (i.e., 5 and 7 dots) compared to lower retention loads (1 and 3 dots), in keeping with earlier findings of greater γ -tACS effects as the retention load increases in the n-back task [

21].

A final experimental prediction concerned the possible maintenance of active r-tACS-induced VSWM performance gains at the two-week follow-up session, as suggested by evidence of long-term benefits up to a month [

23].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

A total of 35 young adult healthy participants (27 women, 5 left-handed, mean age 23.2 ± 4.94 ys) took part in the study. They were recruited among students of psychology master classes, in exchange for course credits. In an online screening session, they completed a socio-demographic and medical history questionnaire. Inclusion criteria were normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and the admission to no current or past history of neurologic or psychiatric disorders, a learning disability or current use of psychoactive medications.

In a randomized single blind protocol, participants were assigned to one of two groups: Active intervention (N=18) and Sham treatment (N=17). Characteristics of the two groups are shown in

Table 1 below. The study included three sessions of Active or Sham stimulation at 24 hours from each other, at the same time of the day. Each session was composed of three blocks during which participants performed the behavioral task: Before stimulation, during stimulation [to test

online effects], and after stimulation [to test

offline effects]). Each block lasted 20 minutes, and was separated by a short resting pause (about 1 minute). Finally, in order to investigate long-term effects, a follow-up session was conducted after about 2 weeks. A single block of the behavioral task, lasting 20 minutes, was administered without stimulation.

2.2. Experimental Task

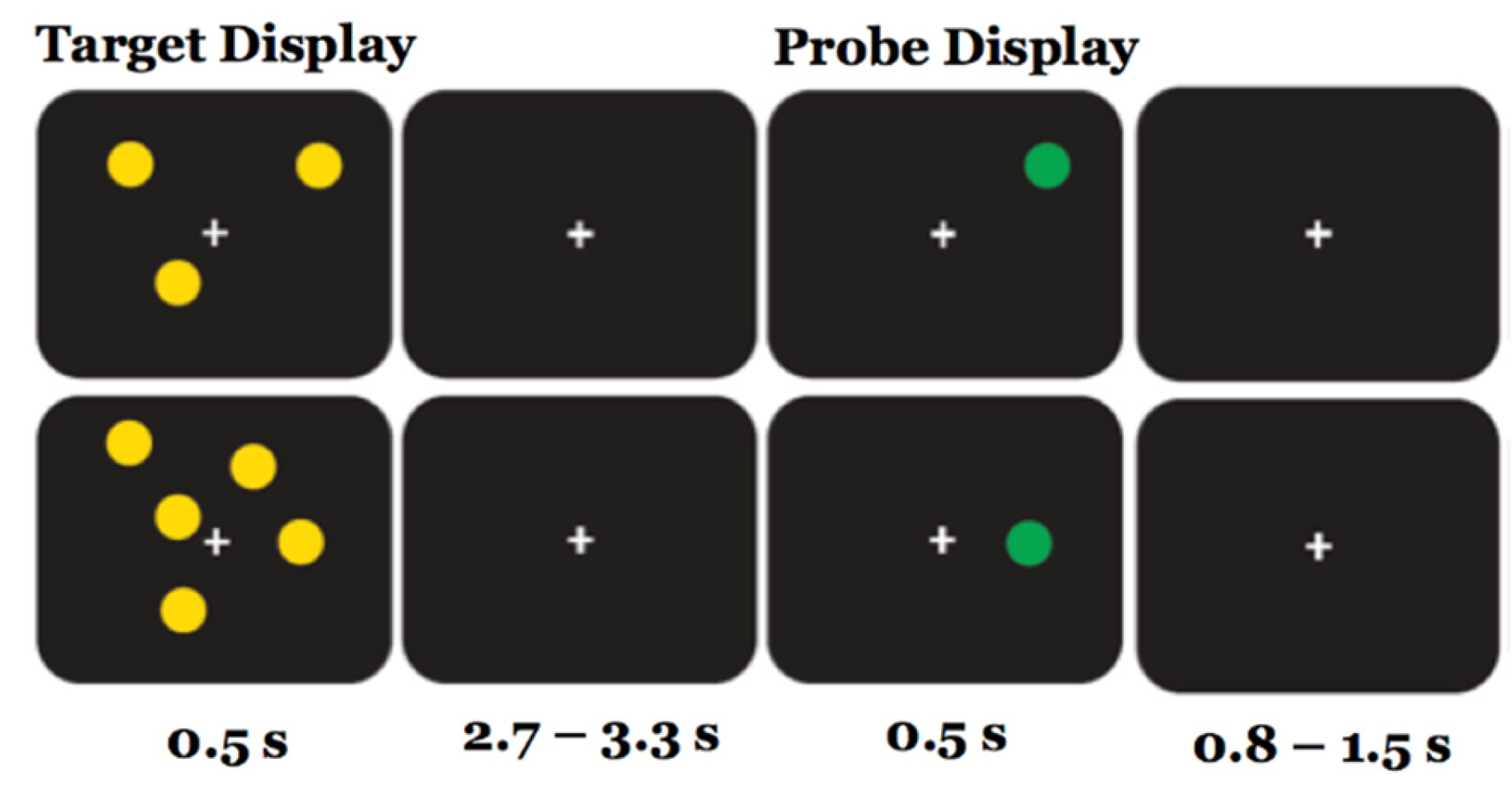

Participants sat in a sound attenuated room facing a computer screen at a distance of 60 cm from their eyes. In the spatial capacity delayed response task (SCDRT, [

6,

7]) each trial started with the presentation of the target display, consisting of an array of 1, 3, 5, or 7 yellow circles positioned pseudorandomly around a central fixation cross, for the duration of 0.5 sec. After a delay interval of 2.7 to 3.3 sec (average 3 sec), during which they saw only the fixation cross, the probe display appeared, consisting of a single green circle lasting 0.5 sec. Participants were asked to determine if the probe circle was or not in the same spatial location as one of the preceding target circles, by pressing one of two buttons on the computer keyboard (M or Z). Half of the trials contained a probe in the same spatial location (true positives), and half in a different spatial location (true negatives). Each trial ended with an inter-trial interval of 0.8 to 1.3 sec, during which the fixation cross was presented alone. A time limit of 1.5 sec was set for the choice RT decision. The total duration of each trial was about 5 sec.

Each of the 3 sessions was preceded by a short practice phase to familiarize with the task, during which a visual feedback for correct or wrong response was provided after each trial. For each session, the three experimental blocks (pre, during and post intervention) included 200 trials, divided in two sub-blocks of 100, separated by a short resting pause for a total duration of about 20 minutes. There were 50 trials for each target capacity load (1, 3, 5 and 7 dots); half were same location, half different location trials. In each block, target capacity load (1, 3, 5 and 7) and same/different response were randomized, with a limitation of a maximum of three successive presentations of the same target retention load or same/different response probe. RTs and accuracy of each response were recorded for each target retention time and same/different probe response (Figure 1).

2.3. HD-tACS

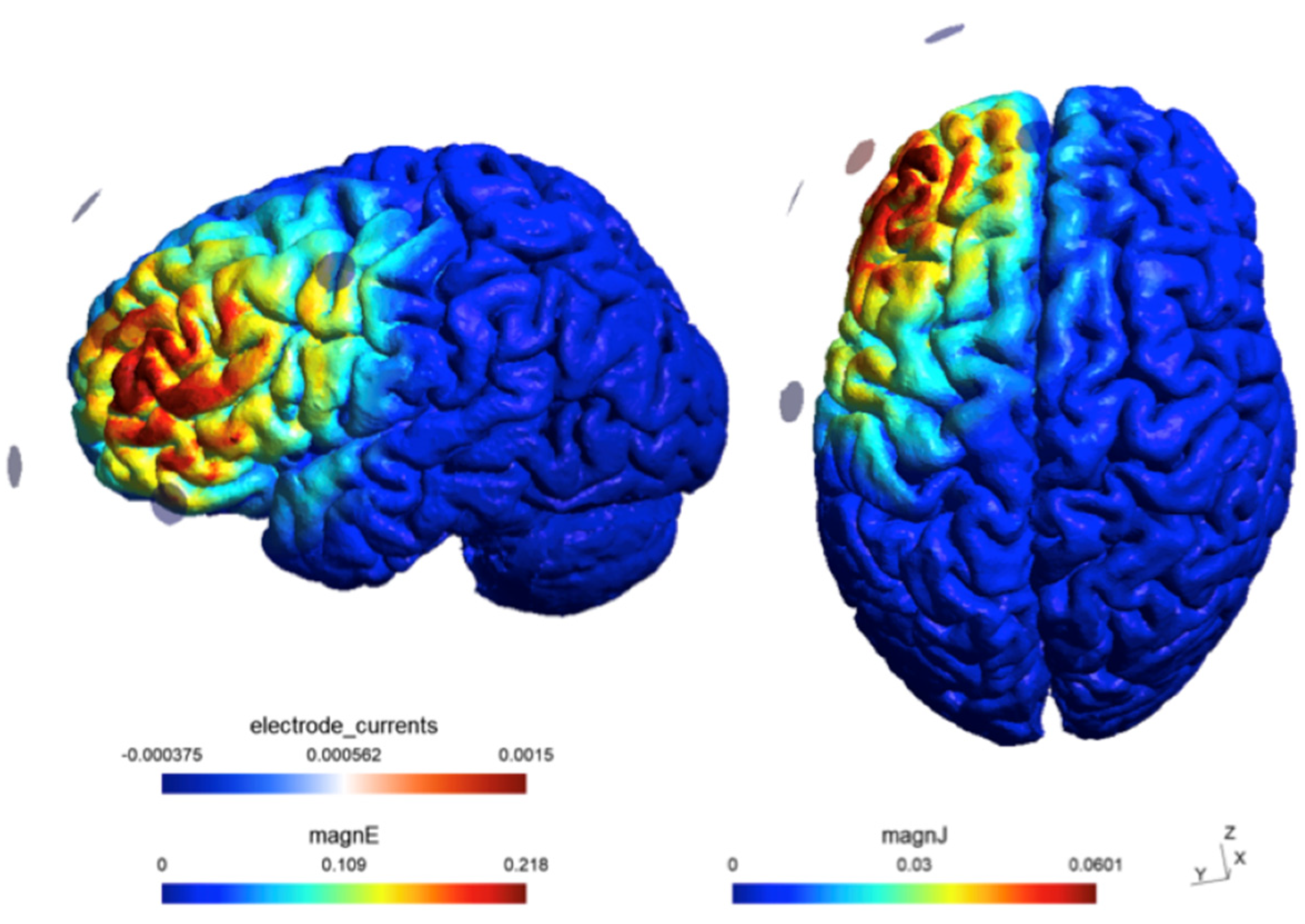

The alternating current was non-invasively delivered using a five-channel high-definition (HD) transcranial electrical current stimulator (Soterix Medical, Woodbridge, USA). An elastic cap was embedded with plastic holders containing five 12-mm-diameter Ag/AgCl ring electrodes, filled with conductive gel. The electrodes were placed in a 4×1 ring montage, with the central stimulating anode electrode over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), at site F3 of the 10-20 system, corresponding to MNI coordinates -36, 49, 32, Brodmann Area 9 [

24], and the return cathode electrodes placed about 5 cm away and approximately equidistant from the neighboring two cathode electrodes (sites F7, Fp1, Fz and C3 of the 10-20 system). A bipolar sinusoidal alternating current was applied at 40 Hz (γ range) at 1.5 mA intensity for 20 minutes. All participants tolerated the intervention well, and no adverse events were reported.

The experiment was sham-controlled. The passive sham protocol followed the same procedure as the active neuromodulation but, critically, the stimulation lasted only 30 seconds, ramping up and down at the beginning and end of the 20-minute period, reproducing the warming and poking sensations participants commonly report and then habituate to during active neuromodulation.

Figure 2 depicts the results of a simulation (SimNIBS 4.1 software) modelling the electrical field generated by the γ-tACS and the returning estimates of the electrical field strength (0.18562 V/m) and the current density at the targeted ROI (0.051045 A/m2).

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Two participants were excluded from further analysis due to technical issues during data collection. Trials with response times faster than 200 ms and slower then 1500 msec were excluded from further analysis. Trials without response and sub-blocks with less than 70% of responses were excluded (0.018% of experimental trials). We also checked that all participants in the experimental sessions had a mean accuracy of ≥ 80% in the easiest experimental condition (1 dot). Two participants (one per group) were excluded since they showed < 80% mean accuracy in two experimental sessions. The final sample was formed by 33 participants (17 Active and 16 Sham). Finally, one participant from the Active group was excluded from the analysis of the long-term effects of the stimulation since it provided less than 70% responses in both sub-blocks of the follow-up session.

Two series of statistical analyses on accuracy and RTs were performed to investigate: a) The short-term effects of Active tACS, that were analyzed by comparing the performance in the 3 experimental blocks of session one to three; b) The long-term effects of Active tACS, which included the first experimental block (pre-stimulation) for session 1 to 3 as well as the follow-up session. Response accuracy as a dichotomous variable was analyzed using generalized linear mixed models with binomial distribution and logit link. We set nAGQ = 0 to reduce the computational burden. RTs of correct responses were log-transformed and analyzed using linear mixed-effects models (Gaussian distribution). The mixed-effects models were fitted using respectively the lmer and glmer functions of the lme4 package [

25]. For each dependent variable, model selection was performed using the buildmer function from the “buildmer” package [

26]: This function identifies the ‘maximal converging model’, which is the model containing either all effects specified by the user, or a subset of those effects that still allow the model to converge, ordered such that the most information-rich effects are included. Then, it performs a backward stepwise elimination process to select the predictors to be included in the final model. The stepwise elimination was based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) as an index of goodness of fit of the model. The AIC gives information on the models’ relative evidence (i.e., likelihood) and penalizes redundancy, therefore the model with the lowest AIC is to be preferred [

27,

28].

For the analysis of the short-term effects of stimulation, the starting model included the main effects of Session (3 levels: 1st, 2nd, and 3rd session), Block (3 levels: 1st, 2nd, and 3rd block), WM Load (4 levels: 1, 3, 5, and 7 dots), and Group (2 levels: Active, Sham). The 2-way and 3-way interactions between Session, Block, WM Load and Group were included in the starting model. For the analysis of the long-term effects of the stimulation, the starting model included the main effects of Session (4 levels: 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and follow-up session), WM Load, and Group. The 2-way interactions and the 3-way interaction between Session, WM Load, and Group were included in the starting model. All the tested models included participant as random intercept to account for the participant-specific variability and the correlation of the observations within participants. Model outliers were identified using the outlierTest function of the car package [

29] and removed (max 1 observation per model). Sum coding was used as contrasts coding in order to estimate main effects [

30]. Post-hoc comparisons were performed using the contrast function of the emmeans package [

31]. P-values were adjusted using Bonferroni correction [

32].

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics for accuracy according to Group, Session and Block are reported in

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for RTs (msec) according to Group, Session and Block are reported in

Table 3.

3.1.1. Short-Term Effects of the Stimulation

Accuracy

The best fitting model for response accuracy was: Accuracy ~ 1 + WM Load+ Block + Session + WM Load*Block + Block*Session + (1 | Participant)

Test statistics for the best fitting model for response accuracy are reported in

Table 4.

The best fitting model for response accuracy did not include the main effect of Group or related interaction terms.

Reaction Times (RTs)

The best fitting model for response times was: LogRTs ~ 1 + WM Load + Session + Block + Group + Session*Block + Session*Group + WM Load *Block + WM Load * Session + Block*Group + Session*Block*Group + (1 | Participant)

Test statistics for the best fitting model for response times are reported in

Table 5.

3.2. Mixed models results

Based on our experimental hypotheses, we focused on the interaction effects involving the variable Group, namely SessionXGroup, BlockXGroup and BlockXSessionXGroup.

3.2.1. Session X Group interaction

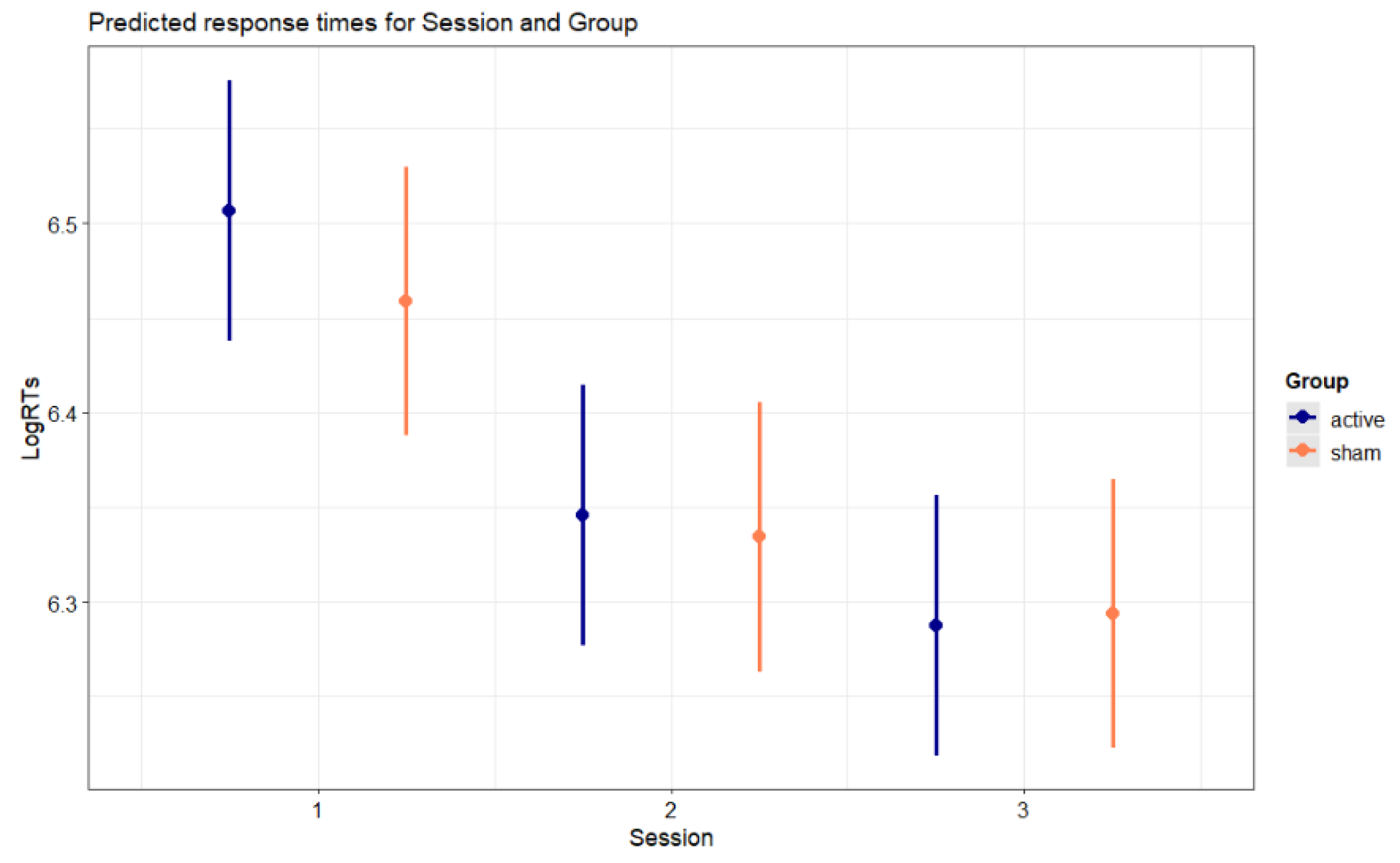

Figure 3 illustrates the predicted response times for the interaction Session X Group (

p < .001). Both groups displayed faster RTs in the second session compared to the first session (

active: b = -0.161, SE = 0.004, z-ratio= -41.439,

p < .001;

sham: b = -0.125, SE = 0.004, z-ratio = -31.254,

p < .001), and in the third session compared to the second session (

active: b = -0.059, SE = 0.004, z-ratio = -15.295, p < .001;

sham: b = -0.041, SE = 0.004, z-ratio = -10.347, p < .001). Contrasts between active and sham groups did not attain significance. The Session X Group interaction was explained by a greater reduction of RTs from the first session to the second session (b = 0.036, SE = 0.006, z-ratio = 6.434, p < .001), as well from the second session to the third session (b = 0.018, SE = 0.006, z-ratio = 3.282, p = .001), in the active group compared to the sham group.

3.2.2. Block X Group Interaction

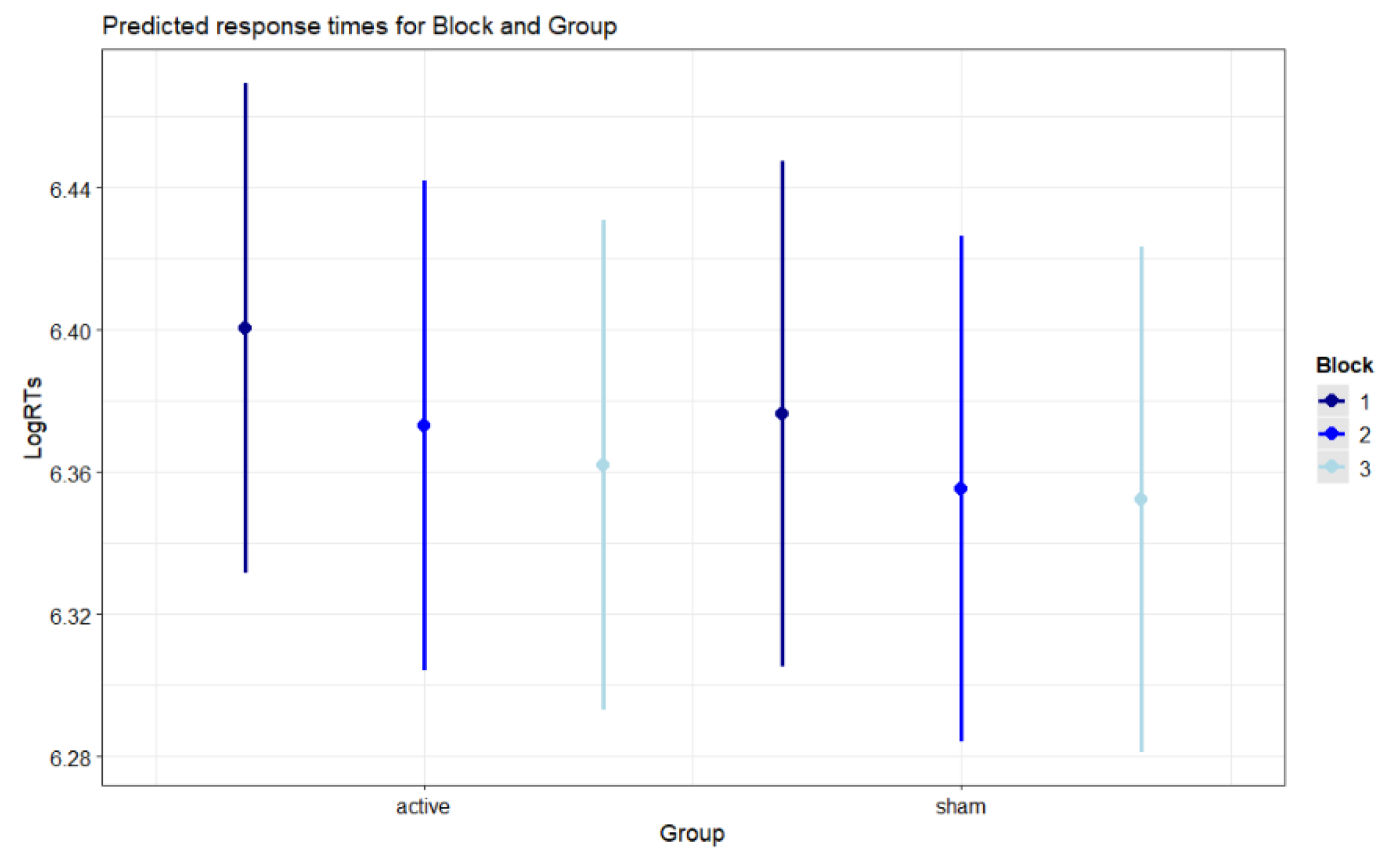

Figure 4 illustrates the predicted response times for the interaction Block X Group (

p = .035). The significant Block X Group interaction was explained by the fact that, independent of session, the active group displayed significantly faster RTs in the third block (post-stimulation or

offline condition) compared to the second block (stimulation or

online condition) (b = -0.012, SE = 0.004, z-ratio = -2.956,

p = .022), while the sham group showed no differences between third and second block (b = -0.004, SE = 0.004, z-ratio = -0.876,

p = 1). No comparison between active and sham groups reached statistical significance.

3.2.3. Block X Session X Group Interaction

The interaction Block X Session X Group improved model fitting but did not reach statistical significance, albeit it marginally approached significance (

p = 0.068). Given the evidence that r-tACS improves WM performance over the course of four repetitions

[23] and that tACS effects on cognitive performance appear to be stronger for

offline relative to

online stimulation [

19,

20] we went on, on a exploratory basis, performing pairwise contrasts in order to explore specific differences in the estimated marginal means of Block, Session and Group. Such contrasts are reported in the

Supplementary Materials (section 6.2).

3.3. Long-term effects of the stimulation

3.3.1. Accuracy

The best fitting model for response accuracy was: Accuracy ~ 1 + WM Load + Session + (1 | Participant)

Test statistics for the best fitting model are reported in

Table 6.

The best fitting model for response accuracy did not include the main effect of Group or related interaction terms.

3.3.2. Reaction Times (RTs)

The best fitting model for response times was: LogRTs ~ 1 + Session + WM Load + Group + Session*Group + Session* WM Load + (1 | Participant)

Test statistics for the best fitting model for response times are reported in

Table 7.

Based on our experimental hypotheses, we focused on the interaction effects involving the variable Group, namely SessionXGroup, BlockXGroup and BlockXSessionXGroup.

3.4. Session X Group interaction

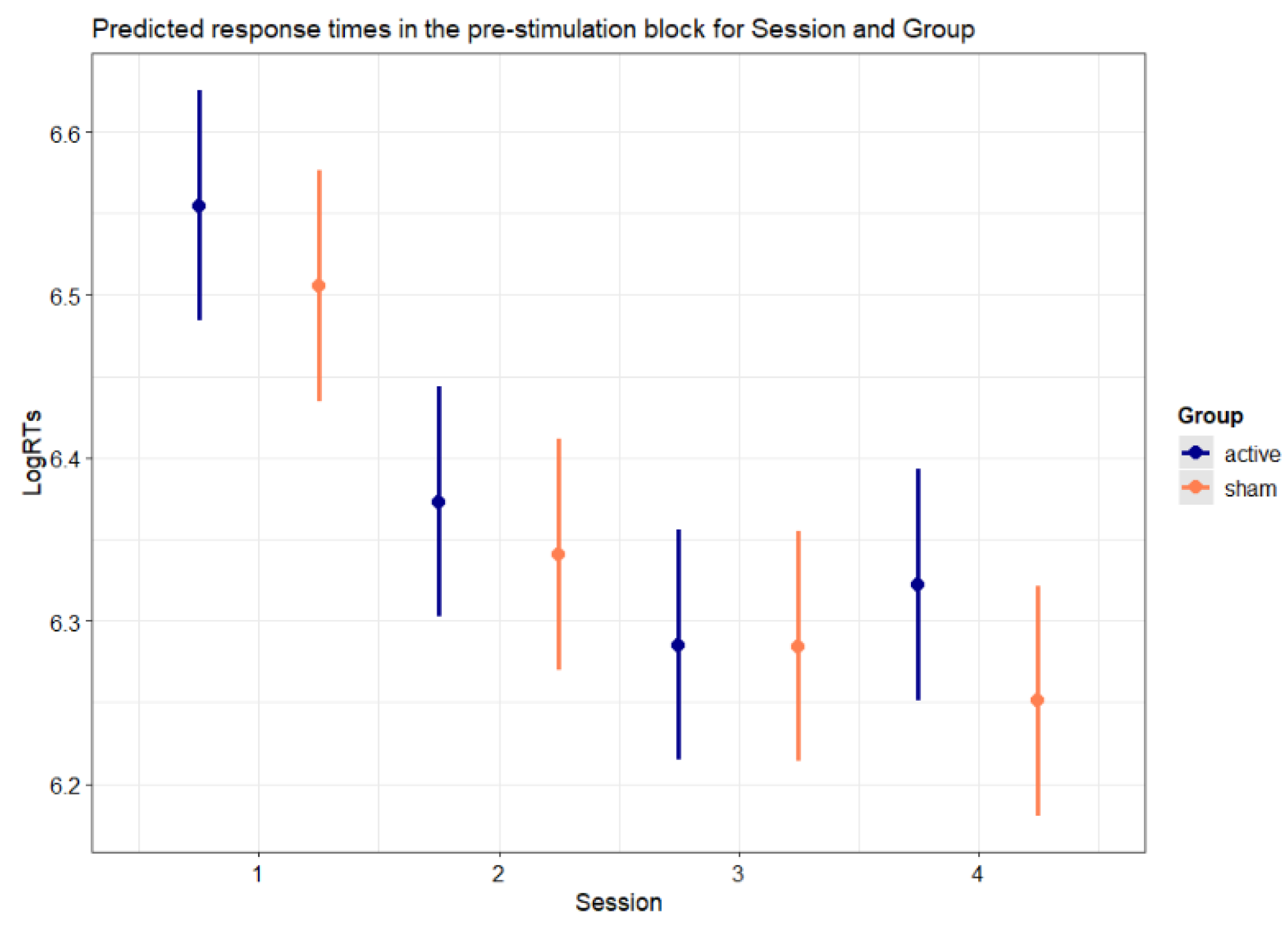

Figure 5 illustrates the predicted response times for the interaction between Session and Group (p < .001).

Both groups showed faster RTs in the pre-stimulation block of the second session compared to the pre-stimulation block of the first session (active: b = -0.182, SE = 0.007, z-ratio = -27.312, p < .001; sham: b = -0.165, SE = 0.007, z-ratio = -24.904, p < .001), and in the pre-stimulation block of the third session compared to the pre-stimulation block of the second session (active: b = -0.089, SE = 0.007, z-ratio = -13.484, p < .001; sham: b = -0.057, SE = 0.007, z-ratio = -8.630, p < .001). The interaction between Session and Group was explained by the greater reduction of RTs in the pre-stimulation block between the second session and the third session in the active group compared to the sham group (b = 0.032, SE = 0.009, z-ratio = 3.405, p = .004), In contrast, such modulation of RTs with Active stimulation was not present between the first session and the second session (b = 0.017, SE = 0.009, z-ratio = 1.820, p = .413). Furthermore, and critically, while the sham group showed faster RTs in the follow-up session compared to the pre-stimulation block of the third session (b = − 0.034, SE = 0.007, z-ratio = -5.136, p < .001), the active group showed increased response times in the follow-up session compared to the pre-stimulation block of the third session (b = 0.037, SE = 0.007, z-ratio = 5.617, p < .001). As a further confirmation that the response speed gains due to the active treatment did not propagate to the follow-up session, the active group did not differ from the sham group in the reduction of RTs comparing the pre-stimulation block of the first session to the follow-up session (b = -0.022, SE = 0.009, z-ratio = -2.330, p = .119).

4. Discussion

This randomized single blind placebo controlled study was carried out to test the short-term and long-term efficacy of repetitive γ-tACS over the left DLPFC to improve VSWM performance in healthy young adults in the spatial capacity delayed response task (SCDRT). The design allowed to assess the influence of stimulation protocol (active vs. passive sham), session of stimulation (day 1 to 3), session block (before stimulation, during stimulation and after stimulation) and VSWM retention load (1 to 7 stimuli).

We present novel evidence for a selective improvement in VSWM performance over the course of three repetition sessions in young adults through entrainment of gamma rhythms in the left DLPFC in the active stimulation group. The behavioral effects concerned response speed but not accuracy. Such VSWM performance gains in the active stimulation group appeared no longer evident long-term, at a follow-up session after two weeks.

4.1. Short-Term Effects of γ-tACS Repetition (24 Hours)

Our first experimental hypothesis, that Active r-tACS intervention would significantly improve VSWM performance relative to the Sham treatment by a progressive boosting of VSWM over the three days of stimulation, was upheld. The first mixed model analysis on RTs showed that response speeding was significantly greater for the Active tACS than the Sham stimulation, above and beyond effects of practice or other spurious effects of expectation, with significant gains on day 2 and day 3. This effect was present regardless of experimental block (before, during or after stimulation).

The second mixed model analysis, restricted to the baseline pre-stimulation condition (Block 1) of each session, confirmed the greater gains on RTs speed over consecutive sessions for the Active intervention. The effect was in this case significant for day three, while it did not approach significance for day 2. Combining the results from both analyses, it appears safe to conclude that Active γ-tACS produced significant and incremental VSWM gains lasting at least until the following stimulation session (24 hours), starting from day 2.

To our knowledge, only one recent study explored the effects of r-tACS (four sessions) on WM performance, reporting WM benefits on day 3 and day 4. However, the task involved audio verbal WM, stimulation locus was over the parietal region, and the effective stimulation frequency was in the θ range (4-7 Hz) and not in the γ range. Furthermore, the study involved an aging population (65-88 ys old) [

23].

In the literature, repeated sessions of α (8-12 Hz) HD-tACS yielded significant effects also in other domains, such as the study of the effects of anxiety. Four sessions of α HD-tACS over parieto-occipital scalp were effective in reducing anxiety symptoms and related EEG functional connectivity correlates both at 30 min and after 24 hours [

33].

It has been proposed that WM benefits of tDCS of the left DLPFC in a n-back task may be explained by a mechanism of long-term potentiation (LTP): A short episode of synaptic activation in the stimulated area inducing a persistent increase in synaptic transmission through neuronal plasticity due to the synthesis of genic products [

16]. The same mechanism of brain plasticity has been advocated to explain the long-term effects of repetitive and highly focused tACS targeting memory-specific cortical regions and the proper oscillatory band [

23].

In conclusion, this is the first study demonstrating significant VSWM gains employing the SCDRT with incremental effects over three days of γ HD-tACS over the left DLPFC in healthy young adults, and corroborating the efficacy of repeated sessions of stimulation to boost cognitive performance.

4.2. Short-Term Effects of Online vs. Offline γ-tACS (30 Min)

Our second experimental hypothesis that active r-tACS would benefit VSWM performance significantly more in the post-stimulation block (offline effect) rather than during stimulation (online effect) was also supported. Across the three days of intervention, active γ tACS relative to the sham tACS improved RT performance significantly in the post-stimulation block (block 3) relative to the stimulation block (block 2). This is in line with the results of previous meta-analyses employing both tDCS and tACS in healthy cohorts reporting similar advantages of offline over online stimulation to improve WM performance. The present study extends this finding also to VSWM assessed by the SCDRT.

The

offline stimulation effect can be more easily accounted for by the causal mechanism of tACS-induced neural entrainment promoting synchronization of phasic neural oscillations at specific frequencies, if we could assume that it would take some time to build up the effect, which would then manifest at a greater extent in the

offline period (30 min from stimulation) than the

online period. This mechanism could explain similar short-lived gains of tACS (30 min) reported in the literature [

33], and not call into cause LTP and brain plasticity.

4.3. Short-Term Effects of WM Load

Our third hypothesis that active r-tACS-induced VSWM performance gains would concern at a greater extent higher retention loads (i.e., 5 and 7 dots) compared to lower retention loads (1 and 3 dots) was not upheld. There was no hint that response speed or accuracy in the SCDRT were significantly affected by VSWM retention load. This result contradicts findings of a study reporting greater gains in WM in a n-back task with γ -tACS of the left DLPFC as the retention load increased in healthy participants from 2-back to 3-back [

21]. We can only speculate that differences in task difficulty or performance level may explain at least in part this discrepancy. In the present study accuracy was very high (>85% on average), and there is evidence that the effects of neurostimulation may be more pronounced in participants with lower relative to higher cognitive performance [

23].

4.4. Long-Term Effects of γ tACS

Our final experimental hypothesis that active r-tACS-induced VSWM performance gains would persist long-term, at the two-week follow-up session, was also not supported. The benefits of γ tACS on VSWM response speed over the sham treatment present at session 2 and 3, were no longer evident in the follow-up session, after two weeks. This result seems in contrast with the effectiveness of long-term stimulation (up to a month) reported in another WM study employing four repeated sessions in elderly healthy participants [

23]. It is possible that a long-term VSWM effect would need additional stimulation sessions to be appreciable, at least in young healthy cohorts, providing some rationale for using an increased number of repeated sessions to achieve cognitive or clinical benefits.

4.5. Caveats and Future Directions

The study included two relatively small samples of healthy young participants drawn from a rather homogeneous well-educated university student community. The accuracy was very high (>85%) so that a possible effect of r-tACS on people with lower cognitive performance, or the effect of age, could not be addressed [

23]. A larger sample size may allow to assess the influence of factors like levels of cognitive performance, age, or gender.

Future studies may utilize additional stimulation sessions, which could yield more consistent long-term cognitive performance or clinical benefits. Such studies may include older healthy cohorts and evaluate the impact of factors such as trait anxiety or trait depression. Importantly, the potential for clinical efficacy could be validated in patients with neuropsychiatric disorders with various levels of WM dysfunction, such as clinical depression, anxiety or mild cognitive impairment.

5. Conclusions

All the above limitations notwithstanding, this is to our knowledge the first study to report VSWM benefits of repetitive HD γ-tACS of the left DLPFC in healthy young adults, and finding short-term effects of repetition over three repeated sessions as well as effects of offline vs. online stimulation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R. and M.L.; methodology, A.C. and M.L.; software, A.C.; formal analysis, M.R. and M.S.; investigation, M.R. and M.S.; resources, S.C.; data curation, M.R. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R., M.S. and M.L.; writing—review and editing, M.R., M.S., A.C., S.C. and M.L.; visualization, M.R. and M.S.; supervision, S.C. and M.L.; project administration, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved on February 10th 2023 by the Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology at the University of Padua (Protocol number: 5212) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study and signed in the presence of the investigators.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in the study are stored and kept in archived form by the supervisor of the study (M.L.). Data may be available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy reasons.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Margherita Pagini for assistance in data collection and Dr. Pietro Scatturin for his kind technical support for the tACS equipment.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Beliaeva, V.; Savvateev, I.; Zerbi, V.; et al. Toward integrative approaches to study the causal role of neural oscillations via transcranial electrical stimulation. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 2243.

- Polanía, R.; Nitsche M.A.; Ruff C.C. Studying and modifying brain function with non-invasive brain stimulation. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21 174–187.

- Liu, A.; Vöröslakos, M.; Kronberg, G.; Henin, S.; Krause, M.R.; et al. Immediate neurophysiological effects of transcranial electrical stimulation. Nat Commun, 2018, 9(1): 5092. [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.; Nguyen, J.A.; Reinhart, R.M.G. Synchronizing Brain Rhythms to Improve Cognition. Annu Rev Med 2021, 72:29-43. [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, R.M.G.; Nguyen, J.A. Working memory revived in older adults by synchronizing rhythmic brain circuits. Nat Neurosci 2019, 22, 820–827.

- Glahn, D.C.; Kim, J.; Cohen, M.S.; Poutanen, V.P.; Therman, S.; et al. Maintenance and manipulation in spatial working memory: dissociations in the prefrontal cortex. Neuroimage, 2002, 17: 201-213. [CrossRef]

- Cannon, T.D.; Glahn, D.C.; Kim, J.; Van Erp, T.G.M.; Karlsgodt, K.; et al. Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex Activity During Maintenance and Manipulation of Information in Working Memory in Patients With Schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005, 62:1071-1080. [CrossRef]

- Roux, F.; Uhlhaas, P.J. Working memory and neural oscillations: α-γ versus θ-γ codes for distinct WM information? Trends Cogn Sci 2014, 18(1):16-25. [CrossRef]

- Palva, J.M.; Monto, S.; Kulashekhar, S.; Palva, S. Neuronal synchrony reveals working memory networks and predicts individual memory capacity. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 2010, 107(16), 7580–7585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, J.; Petsche, H.; Feldmann, U.; Rescher, B. EEG Gamma-Band Phase Synchronization between Posterior and Frontal Cortex during Mental Rotation in Humans. Neurosci Lett 2001, 311, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruber, T.; Müller, M.M.; Keil, A.; Elbert, T. Selective Visual-Spatial Attention Alters Induced Gamma Band Responses in the Human EEG. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1999, 110, 2074–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Guo, X.; Lv, Y.; Sun, J.; Tong, S. Mental Rotation Process for Mirrored and Identical Stimuli: A Beta-Band ERD Study. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2014: 4948-51. [CrossRef]

- Tallon-Baudry, C. Tallon-Baudry, C. Oscillatory Synchrony and Human Visual Cognition. J. Physiol.-Paris 2003, 97, 355–363. [CrossRef]

- von Stein, A.; Sarnthein, J. Different Frequencies for Different Scales of Cortical Integration: From Local Gamma to Long Range Alpha/Theta Synchronization. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2000, 38, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coccaro, A.; Di Bono, M. G.; Maffei, A.; Orefice, C.; Lievore, R.; et al. Resting state dynamic reconfiguration of spatial attention cortical networks and visuospatial functioning in non-verbal learning disability (NVLD): A HD-EEG Investigation. Brain Sci 2023, 13, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, S.C.; Hoy, K.E.; Enticott, P.G.; Daskalakis, Z.J.; Fitzgerald, P.B. Improving working memory: the effect of combining cognitive activity and anodal transcranial direct current stimulation to the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Brain Stimul 2011, 4, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunoni, A.R.; Vanderhasselt, M.A. Working memory improvement with non-invasive brain stimulation of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Cogn 2014, 86:1-9. [CrossRef]

- Veldema, J. ; Gharabaghi A, Jansen P. (2021). Non-invasive brain stimulation in modulation of mental rotation ability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Neurosci, 7493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A.T.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; Hoy, K.E. Effects of Anodal Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on Working Memory: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Findings From Healthy and Neuropsychiatric Population. Brain Stimul 2016, 9(2), 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, S.; Fayzullina, R.; Bullard, B.M.; Levina, V.; Reinhart, R. M. A meta-analysis suggests that tACS improves cognition in healthy, aging, and psychiatric populations. Science translat med, 2023 15(697), eabo2044. [CrossRef]

- Hoy, K.E.; Bailey, N.; Arnold, S.; Windsor, K.; John, J.; et al. The effect of γ-tACS on working memory performance in healthy controls. Brain Cogn 2015 101, 51–56. [CrossRef]

- Palm, U.; Baumgartner, C.; Hoffmann, L.; Padberg. F., Hasan, A.; et al. Single session gamma transcranial alternating stimulation does not modulate working memory in depressed patients and healthy controls. Neurophysiol Clin 2022, 52(2):128-136. [CrossRef]

- Grover, S.; Wen, W.; Viswanathan, V.; Gill, C.T.; Reinhart, R.M.G. Long-lasting, dissociable improvements in working memory and long-term memory in older adults with repetitive neuromodulation. Nat Neurosci 2022, 25, 1237–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okamoto, M.; Dan, H.; Sakamoto, K.; Takeo, K.; Shimizu, K.; et al. Three-dimensional probabilistic anatomical cranio-cerebral correlation via the international 10-20 system oriented for transcranial functional brain mapping. Neuroimage 2014 21(1):99-111. [CrossRef]

- Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B., Walker, S., Christensen, R. H. B., et al. Package “lme4.” Convergence 2015 12(1), 2.

- Voeten, C. C. Voeten, C. C. Buildmer: Stepwise Elimination and Term Reordering for Mixed-Effects Regression. R package version 2.4. 2024. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=buildmer.

- Akaike, H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Information Theory, Petrov, B. N., Caski, F. Eds.; Akademiai Kiado: Budapest, Hungary, 1973; pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Bozdogan, H. (1987). Model selection and Akaike’s information criterion (AIC): The general theory and its analytical extensions. Psychometrika 1987, 52, 345-370.

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S. An R Companion to Applied Regression, 3rd ed., Sage, 2018.

- Brehm, L.; Alday, P.M. Contrast coding choices in a decade of mixed models. J Mem Lang 2022, 125, 104334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R.V.; Bolker, B.; Buerkner, P.; Gine-Vázquez, I.; Herve, M.; et al. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means (Online). 2023. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/emmeans/index.html.

- Bonferroni, C. Teoria statistica delle classi e calcolo delle probabilità. Pubblicazioni Del R Istituto Superiore Di Scienze Economiche e Commerciali Di Firenze, 1936, 8, 3–62.

- Clancy, K. J.; Baisley, S.K.; Albizu, A.; Kartvelishvili, N.; Ding, M.; Li, W. Lasting connectivity increase and anxiety reduction via transcranial alternating current stimulation. Soc Cognit Affect Neurosci 2018, 13(12), 1305–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).