1. Introduction

In recent years, the study of shadow images has gained prominence due to astronomical observations of black holes. Notably, the optical appearances of the M87* and SgrA* systems obtained by the Event Horizon Collaboration in 2019 [74] and 2022[

2] have been significant. There are still some conjectures about their true nature—whether they are black holes, wormholes, or other compact objects. While waiting for further observations, theoretical studies on related topics have proliferated to identify these systems. For instance, there are many works on calculating shadows and weak/strong gravitational lensing effects for wormholes[

2,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17], boson stars [

18,

19,

20], and naked singularities [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. A widely recognized view is that these objects are black holes, although there are many black hole candidates from various theories. Thus, studies of black hole shadow images are very important.

Former investigations on black hole shadows can be traced back to Bardeen in 1972, who demonstrated that the shadow shape of a Kerr black hole is not a circle [

26]. Luminet was the first to establish the optical appearance of Schwarzschild black holes surrounded by a shining and rotating accretion disk using numerical methods[

27]. Gralla et al. examined the shadow images of Schwarzschild black holes illuminated by a geometrically and optically thin accretion disk using ray-tracing methods in Ref.[

28]. A comprehensive review on calculating shadow images is provided in Ref.[

29]. Furthermore, recent works on the shadow images and optical appearances of various black holes can be found in Ref.[

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. All these works indicate that as a major topic in gravity, it has garnered widespread attention in the scientific community.

On the other hand, an abundance of astronomical data suggests that General Relativity (GR) has its boundaries, particularly in explaining phenomena such as Dark Energy and the inflationary period of the cosmos. As a result, the reliability of GR is likely to face questions in exceptional circumstances. It is widely recognized that GR is predominantly a low-energy theory. These observations prompt us to investigate alternative gravitational theories [

53,

54]. A focal point of interest lies in the derivation of an effective four-dimensional theory, offering insights into quantum corrections that modify Einstein’s theory of gravity. These corrections encompasses the Gauss-Bonnet term [

55,

56,

57] and nonlinear electromagnetic corrections [

58,

59]. In fact, the nonlinear electrodynamics plays an important role in these strong field regimes, where the intensity of electromagnetic fields can become comparable to the strength of gravitational fields [

60,

61,

62]. During the primordial stages of the universe, for instance, when energy densities were exceptionally high, the gravitational-electromagnetic interplay was pronounced. Nonlinear electrodynamics could be also instrumental in simulating the behavior of these fields throughout cosmic evolution [

63].

In this work, we focus on a string-inspired theory that involves classical Euler-Heisenberg electrodynamics coupled to a non-trivial dilaton field. Very recently, Bakopoulos et al. present an exact spherically symmetric string-inspired Euler-Heisenberg black hole solution [

64]. Later, A. Vachher et al. examine and compare the gravitational lensing, in the strong field limit, for this magnetically charged black holes [

65]. In addition, testing gravitational theories by the shadow images is one of the most interesting directions. Black hole system, as a strong gravity regime, is a useful tool to test the General Relativity and other theories. A well-studied theory is the GR coupled to the Euler-Heisenberg theory.

Throughout this paper, we adopt the Planck units and the convention.

2. The Theory and the Solution

We’d like to introduce the String-inspired Euler-Heisenberg theory briefly. The action of this theory reads as [

64]

where

R is Ricci scalar,

is the usual Faraday scalar, and

with usual field strength

. Moreover, parameters

and

denote the coupling constants between the scalar field

and non-linear Euler-Heisenberg electrodynamic terms with dimensions (length)

2. Then, the field equations from Eq.(

1) are given by

In this paper, we assume that the scalar function

takes the following form [

64]

Considering static and spherical symmetry metric ansatz

in which

and

are functions of

r and

the unit 2 sphere and substituting the ansatz into the field equations (

2)()(), we can obtain the black hole solution

where the Maxwell four-vector takes the form

and

stands for the magnetic charge carried by the black hole.

Considering scalar free scenario

, and

, the black hole solution reads as

which is the Einstein-Euler-Heisenberg black hole obtained in Ref.[

66].

We set

, there are two kinds of black holes, namely the single horizon with

and the double horizons with

. In this work, we focus on the single horizon black holes, in which the so-called doppelgänge Black Holes arise. Throughout this paper, we fix

without loss of generality. The metric functions

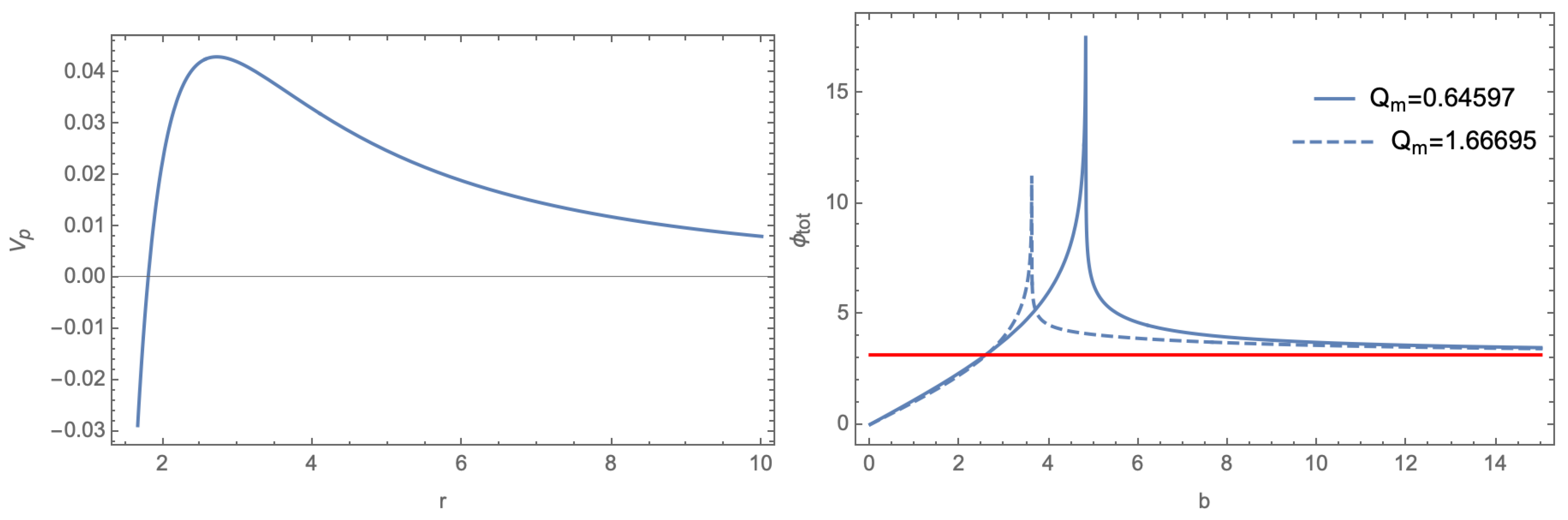

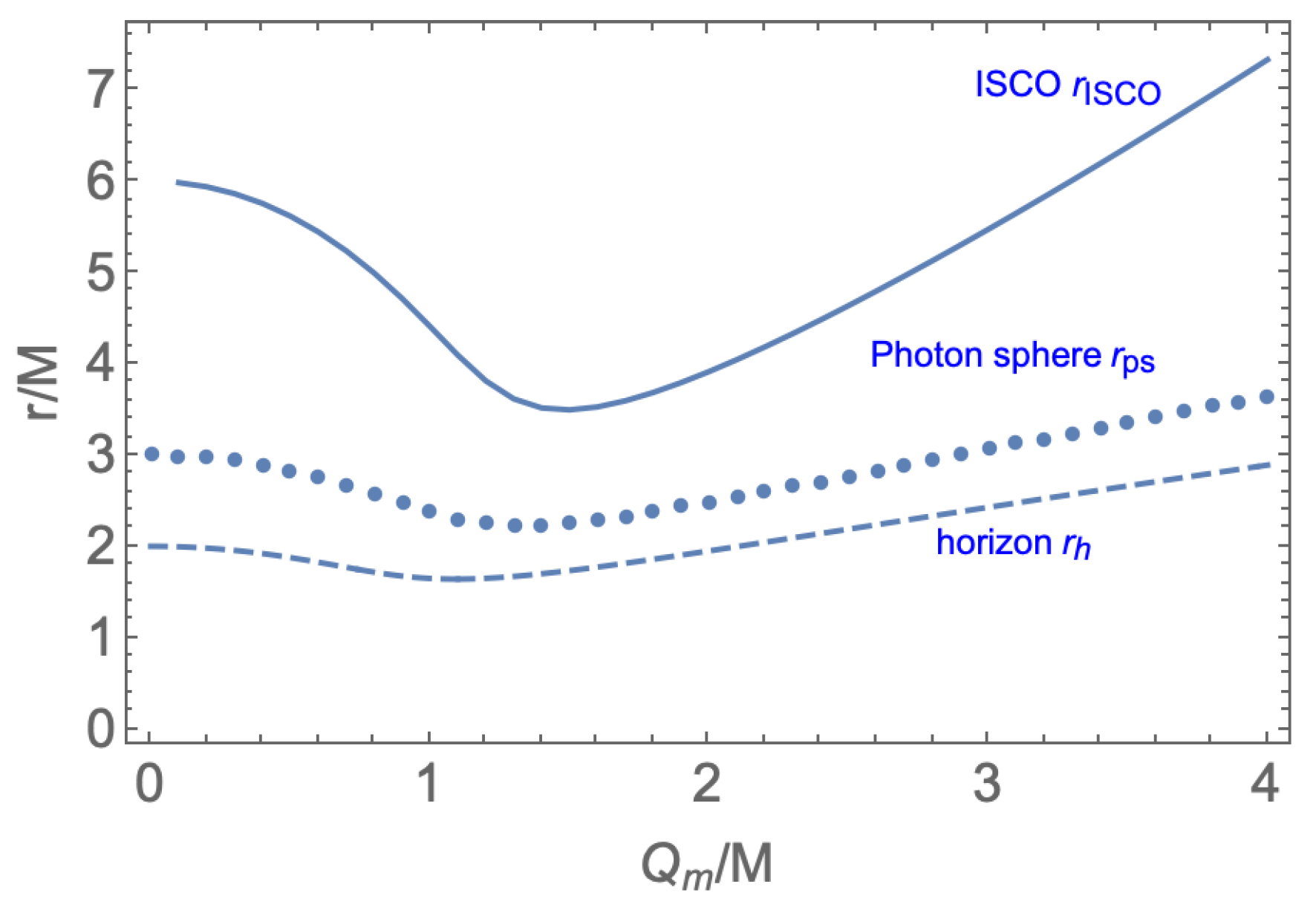

are shown in

Figure 1, we found that there are two kinds of behaviors of the

while the

are alway monotonically increase. For the black holes in the normal Maxwell theory, namely the RN black holes, the metric functions

is monotonically increasing to be 1 in the asymptotic flat region. Interestingly, for the large

black holes in the string-inspired Euler-Heisenberg theory, the

is no longer monotonic. We’ll see it affects the shadow images.

3. Geodesics

The free particles moving in a spacetime described by (

6), there are two conserved quantities, namely the energy

and the angular momentum

. The dot depicts the derivative with respect to the affine parameter. Take the advantage of the spherical symmetry, we focus on the equatorial plane, then

.

It’s straightforward to derive the first-order equation by the geodesic equation [

15],

where

and

the impact parameter, and the effective potential for massive particles (time-like geodesics)

while for photons (null geodesics)

Analysis the effective potentials yield the important orbits, such as the innermost stable circular orbit (ISCO) and photon sphere, around the black holes. Let’s discuss it case by case as follows.

3.1. Time-like Geodesics and ISCO

As a black hole spacetime, it usually admits an special orbit to massive particles, where the particles with the specific angular momentum

can do circular motion in the innermost orbit stably. Such orbit goes by the name of the innermost stable circular orbit (ISCO). In mathematics, the ISCO is an orbit satisfied

One can solve an alternative equation [

40]

to obtain the ISCO.

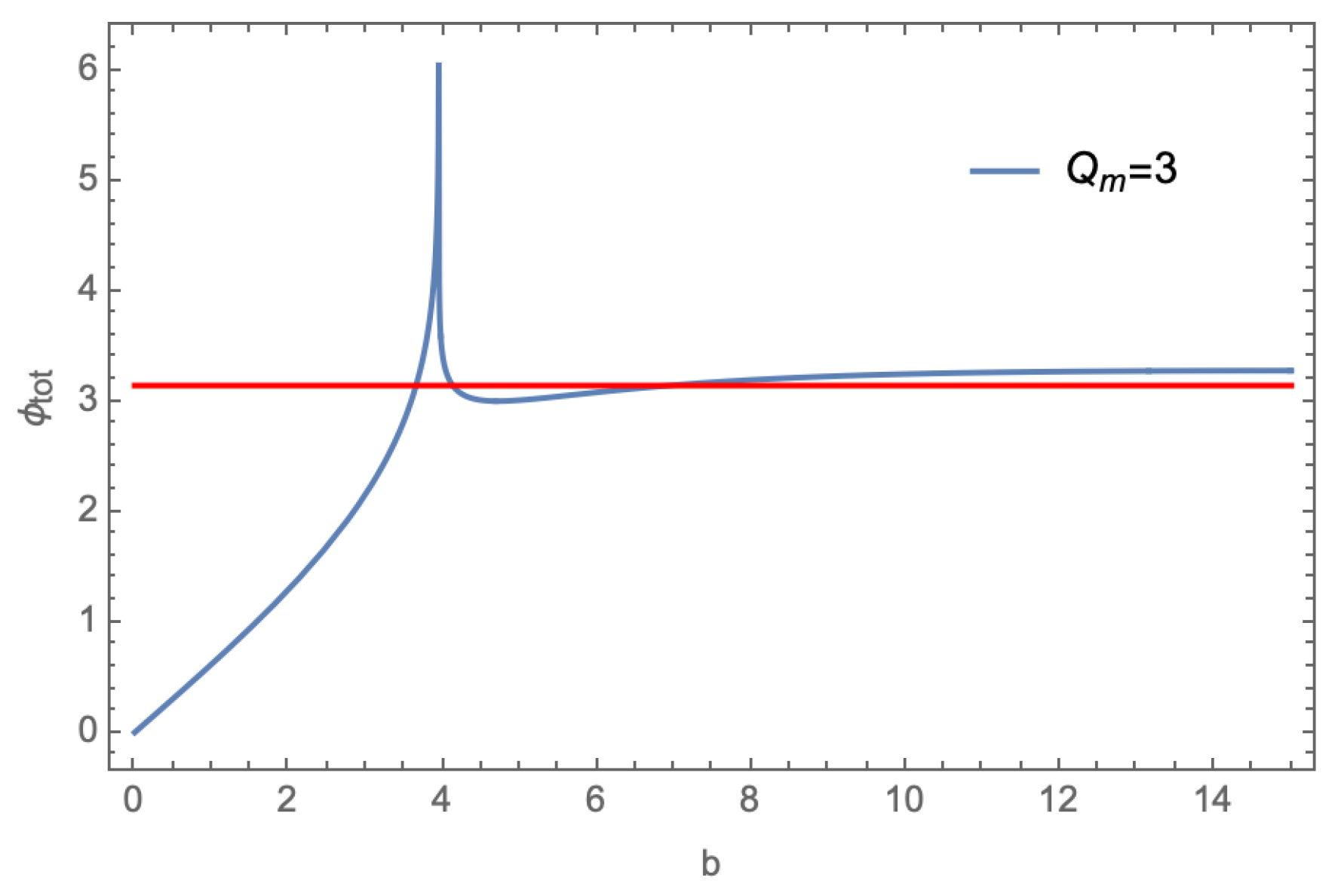

The analytical form of the ISCO is complicated and we present it as functions of

in

Figure 2. It shows that the radii of ISCO are not monotonically increasing or decreasing with

increased. For the small

black holes, the radius of ISCO increase when the magnetic charge

decreased and reduce to a maximum

when

vanished. Note that it coincide with ISCO of Schwarzschild black hole. For the large

black holes, the behavior is exactly the opposite to the small

case: the radius of ISCO increase along with

increased. Furthermore, black holes with the same mass and horizon radii but possess different

share not the same radii of ISCO. Hence one can distinguish them by the size of ISCOs. Moreover, the different size of ISCOs also affects the black hole shadows.

3.2. Null Geodesics and Photon Sphere

The effective potential (

12) has a maximum

located at

. This is what we called the “photon sphere" of a black hole. The critical impact parameter

. According to (

10), it implies that the photons with

have no turning point and will fall into the black hole horizon. An typical example of the effective potential for photons is presented in the left figure of Figure

12.

The photon sphere is very important in the optical appearances of black holes. We present the location of photon sphere with increasing

in

Figure 2. Similar to the case of ISCO above, the behaviors of the photon sphere to the small and large

are different, and the two doppelgänge black holes share two different photon spheres.

The total deflection angle is obtaining by integrating (

10) directly, we show the results in the right figure of Figure

12 and

Figure 4. In the thin disk model

1, setting

, one can see the three special bright regions[

28]:

Direct emission: created by the photons with . The photons intersect with the thin disk once;

Lensing ring: created by the photons with . The photons intersect with the thin disk twice;

Photon ring: created by the photons with . The photons intersect with the thin disk more than twice;

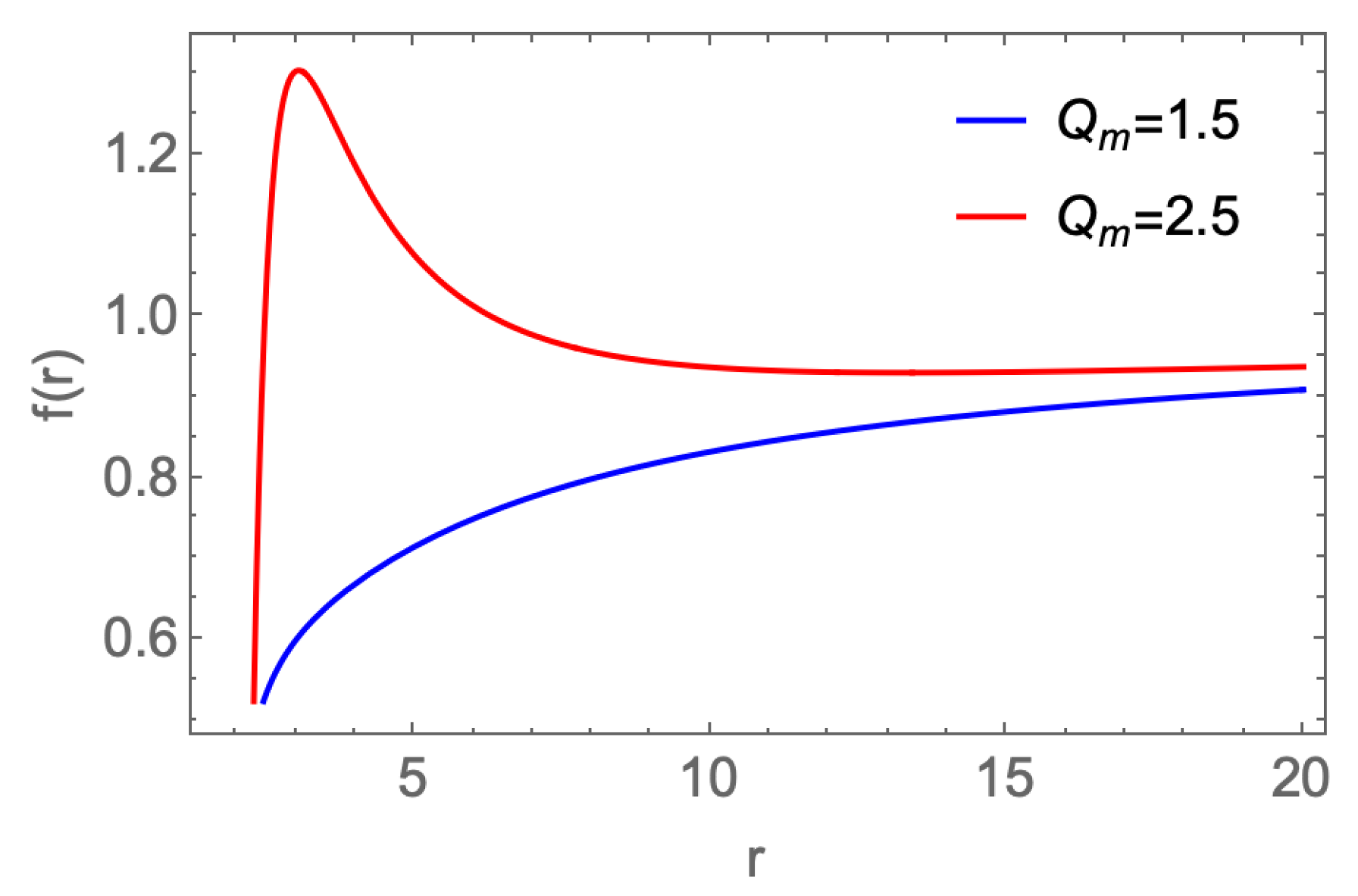

In the right figure of

Figure 3, it shows that the doppelgänge black holes have different direct emissions, photon rings and lensing rings. In

Figure 4, we found a novel phenomenon on the deflection angle curve: the deflection angle is not monotonic decreasing when

. This only arise in the large

case due to the non-monotonic behavior of the metric function

(see

Figure 1).

Figure 3.

Left figure: An typical shape of with . Right figure: The total deflection angle of a pair of the doppelgänge black holes. They possess the same horizon radii and black hole masses.

Figure 3.

Left figure: An typical shape of with . Right figure: The total deflection angle of a pair of the doppelgänge black holes. They possess the same horizon radii and black hole masses.

Figure 4.

The total deflection angle with .

Figure 4.

The total deflection angle with .

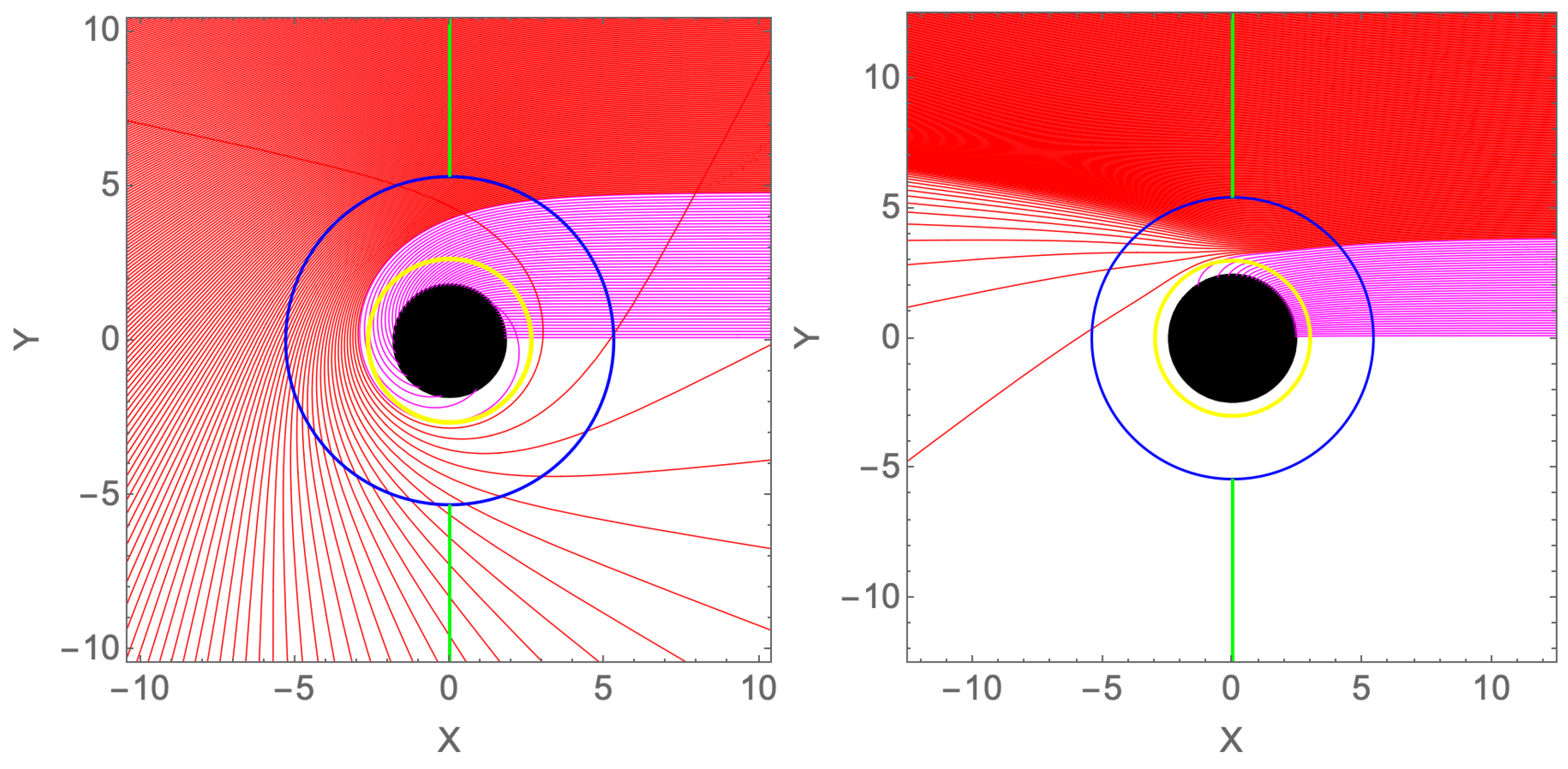

The first-order equation (

10) can be solved numerically. We plot two typical figures of the geodesics in

Figure 5. The up one in

Figure 5 is the black holes corresponding to the right figure of Figure

12, where the deflection angle is monotonic decreasing when

. The down one in

Figure 5 corresponding the black holes in

Figure 4, where the repulsive effect happens in

is showed.

4. Shadow Images

Depends on the forms of accretion, it usually has two kinds of optical appearances to black holes. The fist one is the thin disk model, where the accretion disk extends from the ISCO and its intensity is monotonically decreasing. The second model is considering a spherical accretion enclosed the black hole, and it can be static or free falling to the black hole.

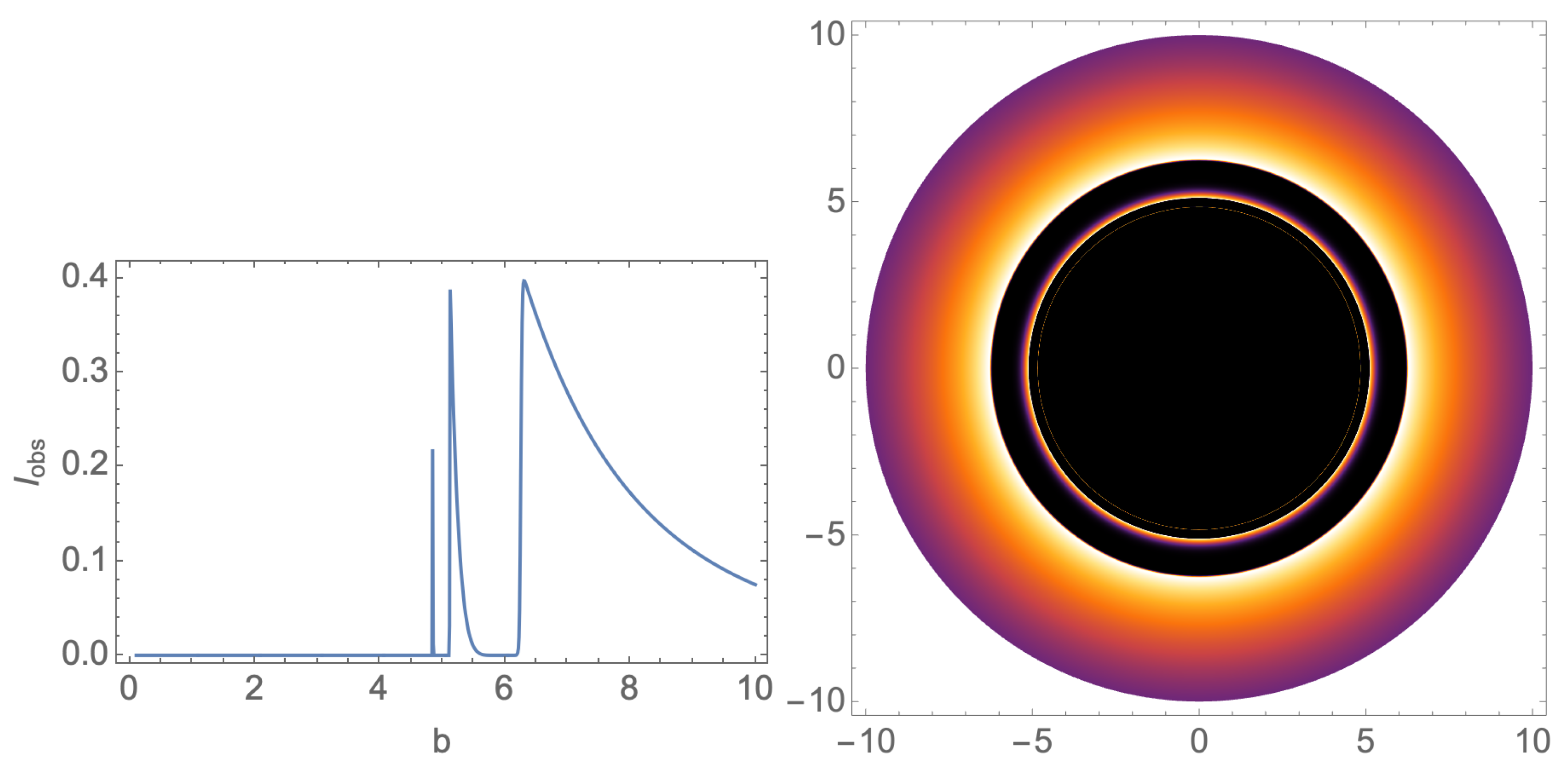

4.1. Thin Disk Model

We consider an optically and geometrically thin disk extends from the ISCO as the light source. The shadow images are affected by intensity function on the disk. Based on the astrophysics scenarios[

19], we adopt the following models for the emitted intensity,

where

is a normalization factor. The ray-tracing method [

39,

41] is used in constructing the shadow images, where the observed intensity can be derived as

where

is the transfer function that indicates the radii of the

nth intersection with the accretion disk.

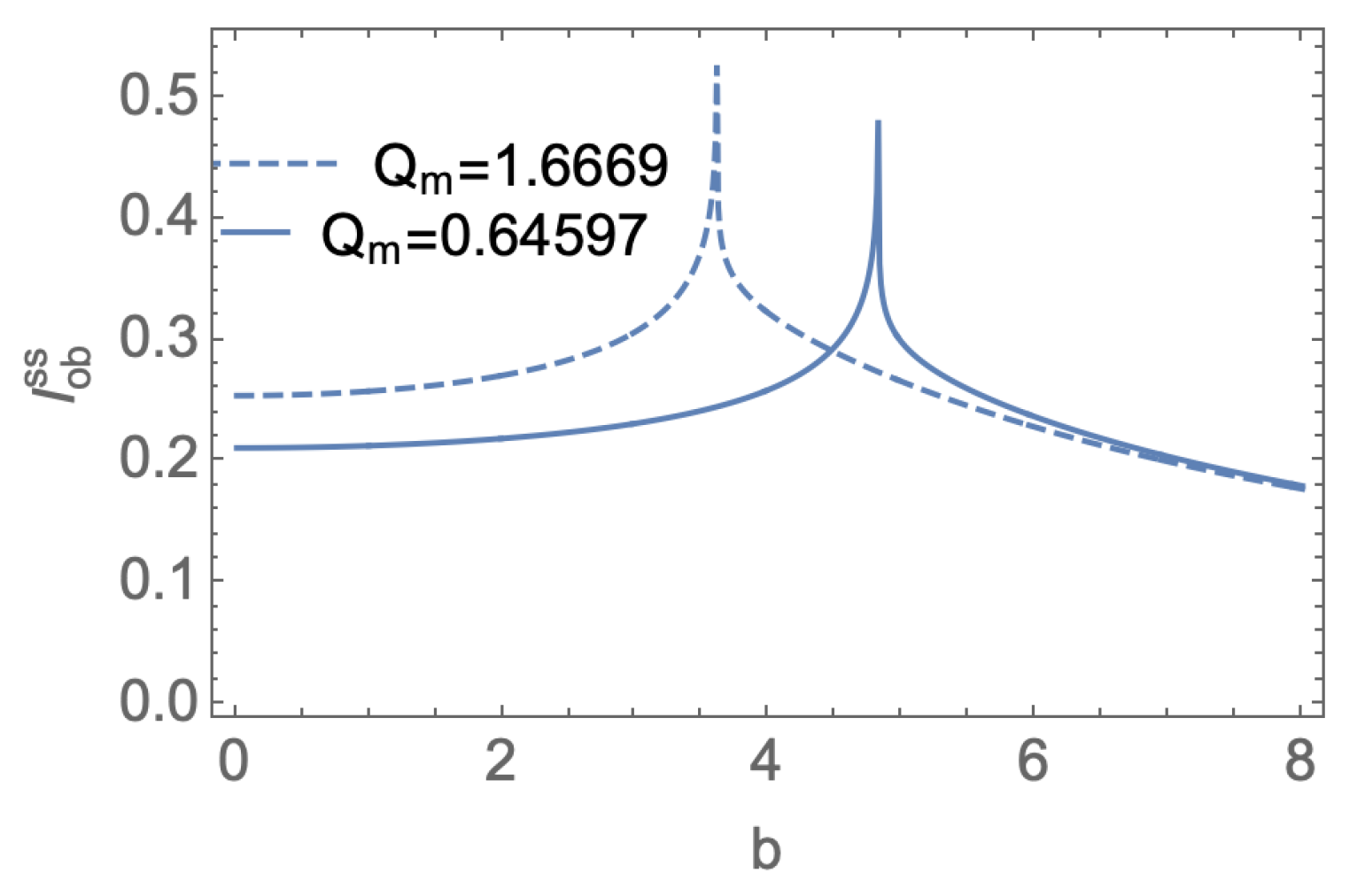

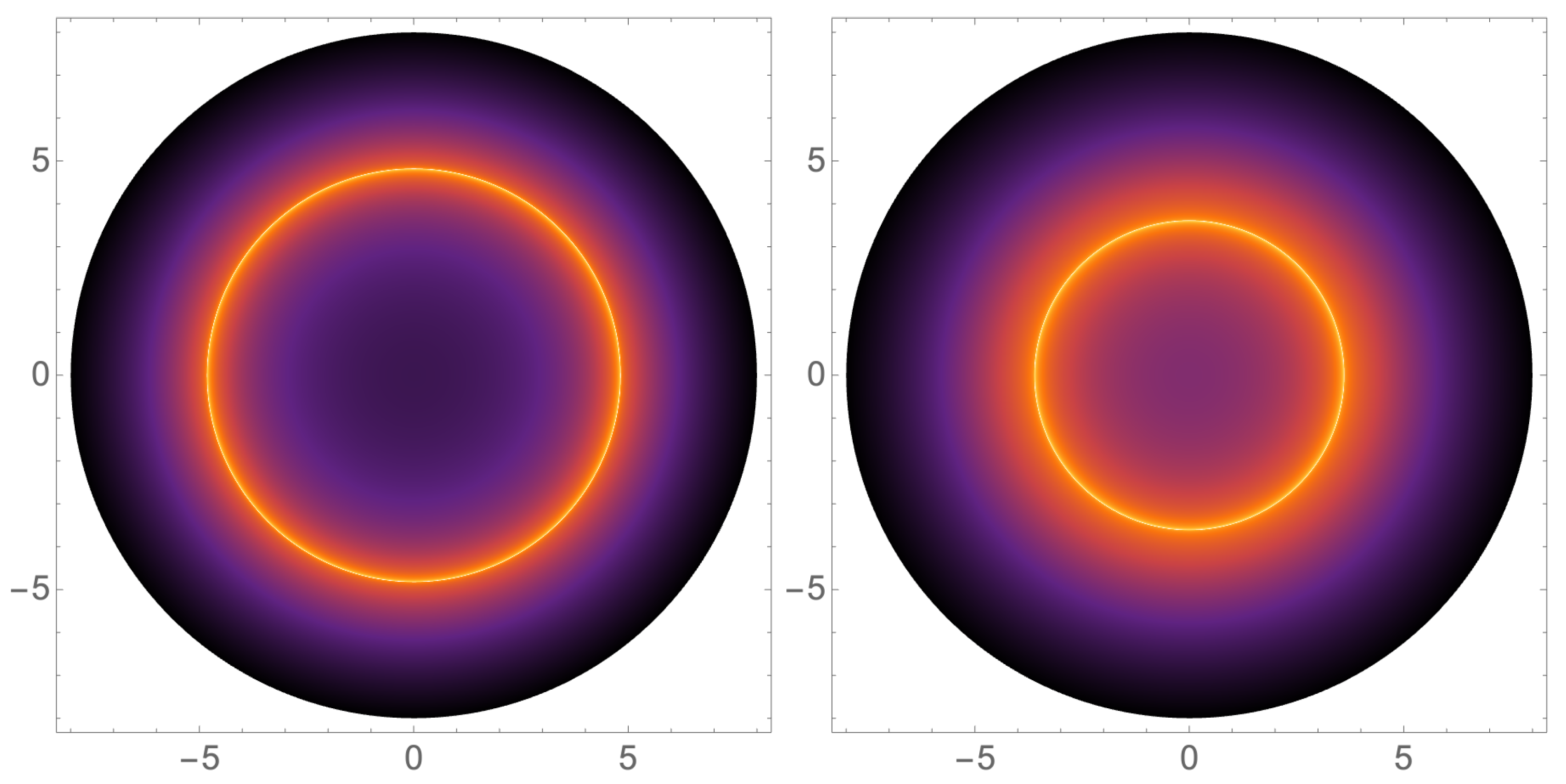

The numeric results of the observed intensity and the corresponding shadow images to the doppelgänge black holes are shown in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7. It shows that the doppelgänge black holes can be distinguished from the shadow images illuminated by the thin accretion disk model. This is mainly due to the different radii of their photon spheres and ISCOs, even for such black holes share the same horizon radii and mass.

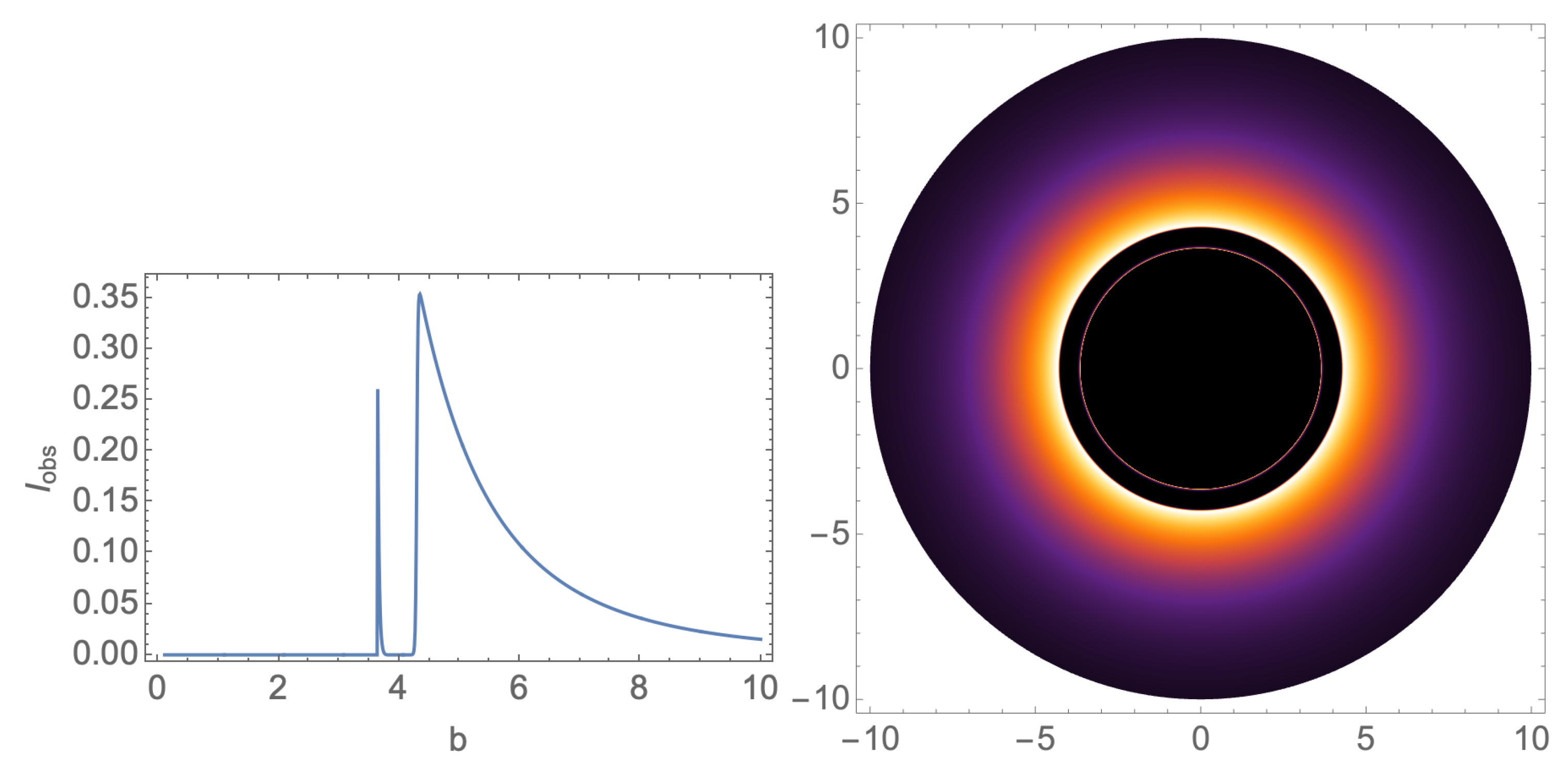

As we discuss above, the metric function

are no longer monotonic increased in the large

case. In

Figure 8, we present the results related to a large

case. We see, because of the unusual behavior of the metric function, there is no clear bright ring inside the shadow.

4.2. Static Spherical Accretion Model

Another possible accretion model in astrophysics is the spherical accretion flow model. As a ideal model, it usually consider the accretion distributed outside the black hole horizon with spherically.

To begin with, we consider the static accretion model. The observed specific intensity of photon with a frequency

to an distant observer is given by [

42,

67]

where

is the intrinsic photon frequency,

the red-shift factor, the infinitesimal proper length is denoted by

and

is the emissivity per unit volume in the rest frame of the emitter. Then total observed intensity is a sum up of all the possible specific intensity,

Furthermore, we consider the radiation is monochromatic with fixed a frequency

, which means

Finally, the observed intensity (

18) reduces to

To the doppelgänge black holes, they give rise to different

. We show an example in

Figure 9, and the related images are shown in

Figure 10

The large black holes do not reveal novel features in the static model, hence we don’t show them here. However, the more realistic case is that the matter falls into the horizon, namely the the infalling spherical accretion flow model. Then the large black holes are quite different from the small one.

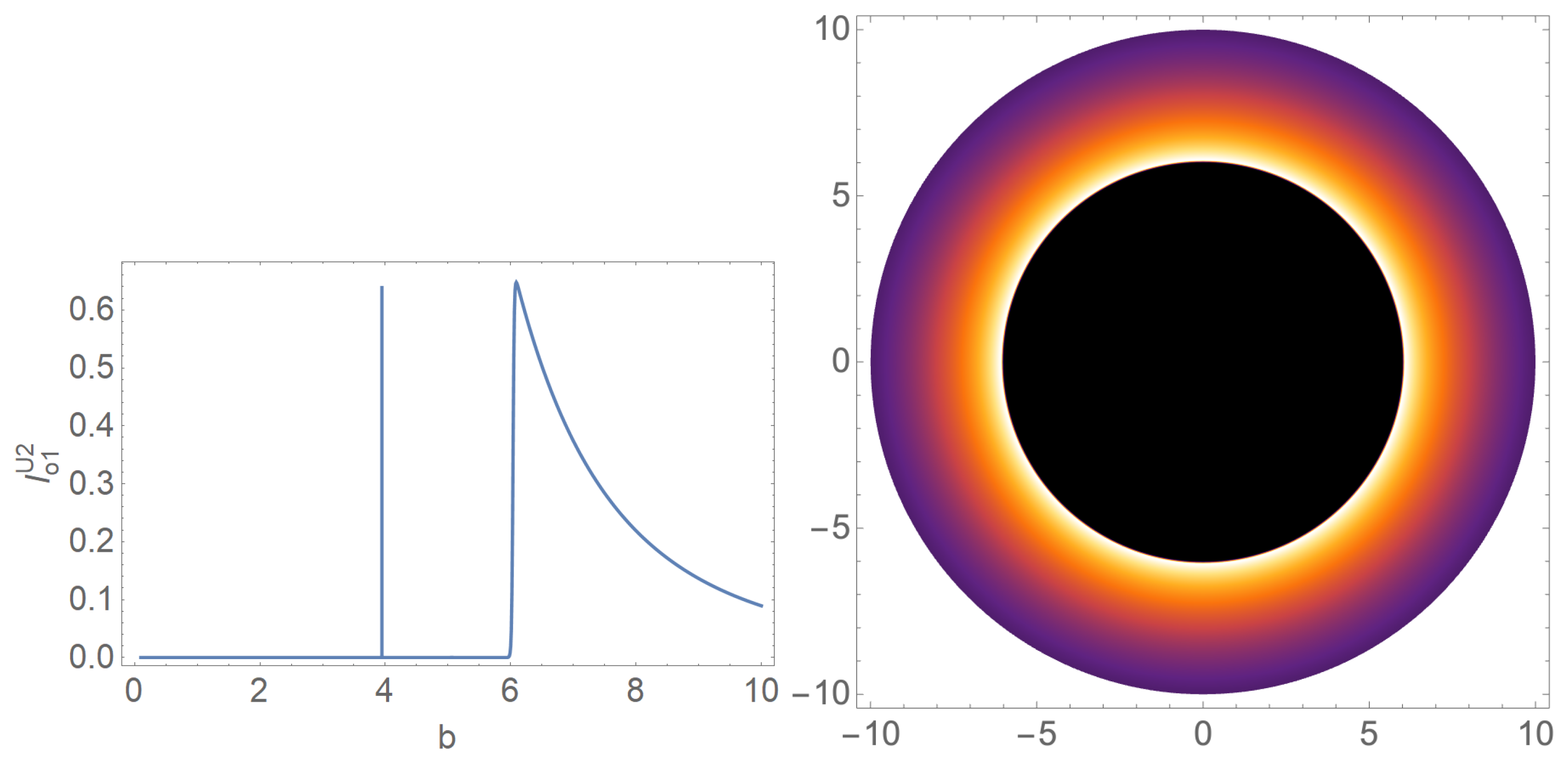

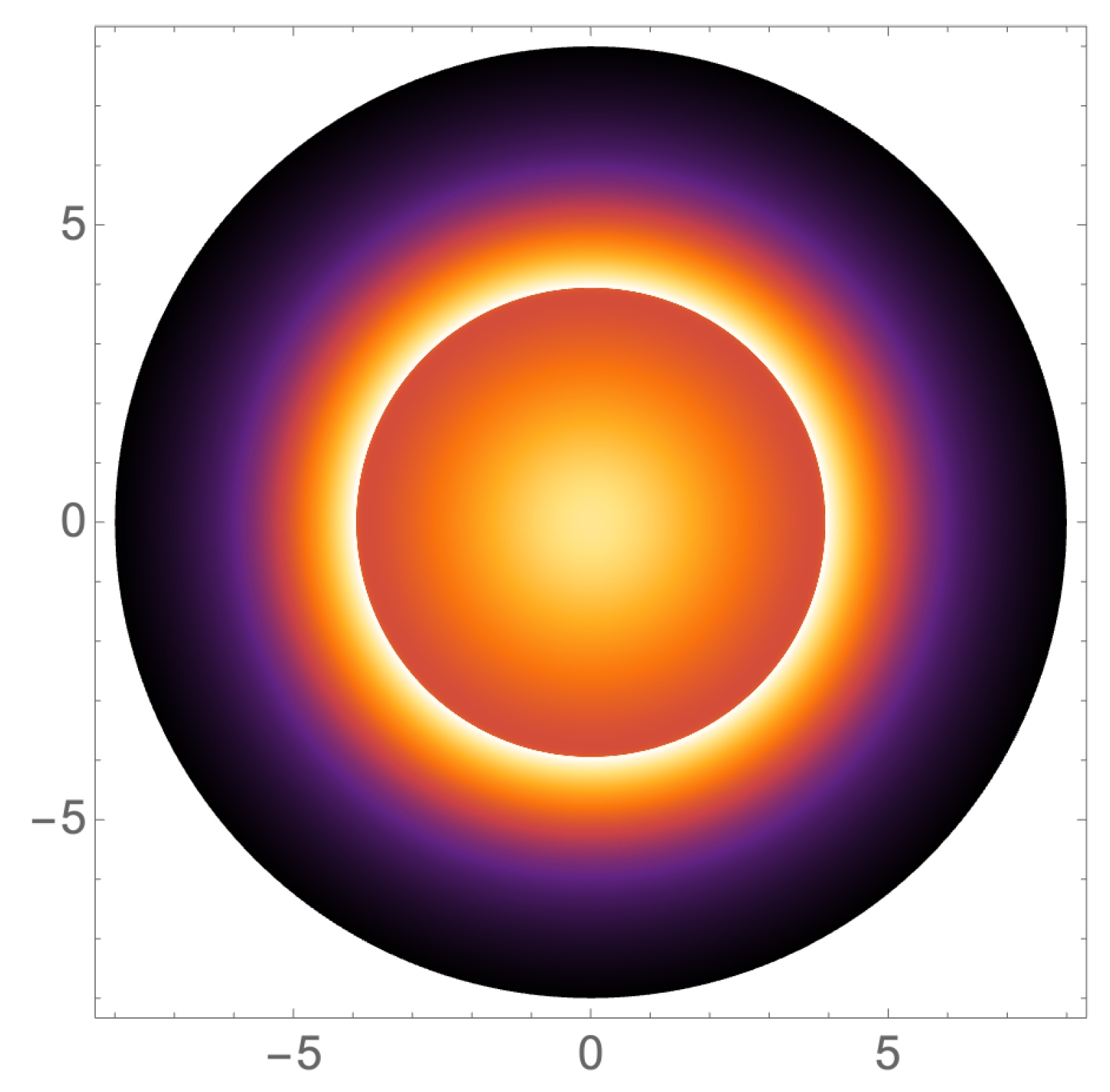

4.3. Infalling Spherical Accretion Flow Model

The (

18) is hold for infalling accretion case. But the red-shift factor depends the velocity of the accretion flow, namely,

where

are the four-velocities of the photons, the stationary distant observers and the infaling accretion flow, respectively. It is straightforward to obtain all the non-vanished components of all the four-velocities are

and

. Finally, the observed intensity of the infalling accretion flow model is given by

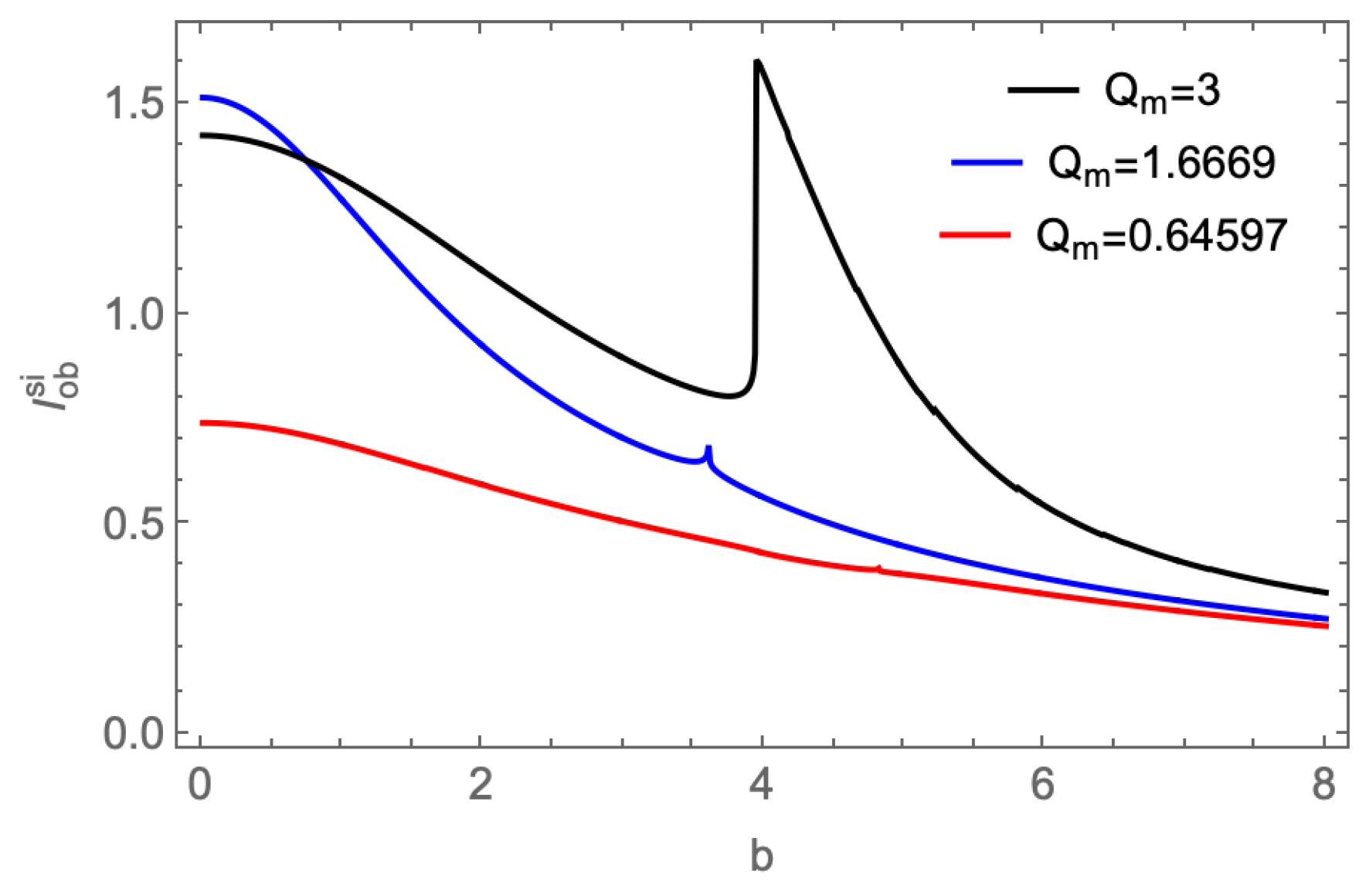

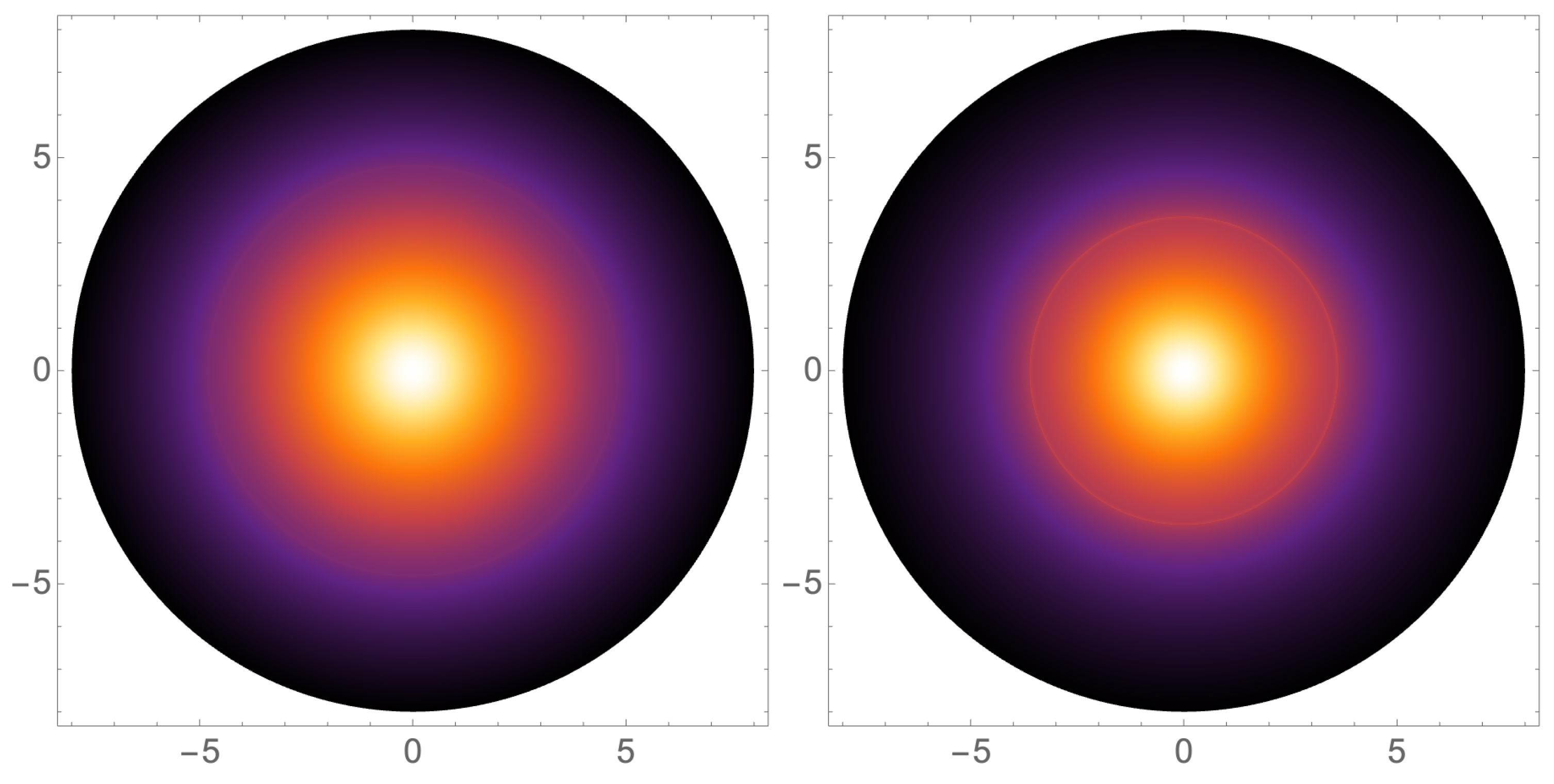

Three examples of the

corresponding to the doppelgänge black holes and large

black hole are shown in

Figure 11. It it clear that the we could also distinguish the doppelgänge black holes in this model. Furthermore, the

of the large

black hole shows a distinct peak. We present the shadow images related to these cases in

Figure 12.

5. Conclusion and Outlook

The phenomenon of having doppelgänge black holes in the string-inspired Euler-Heisenberg theory is quite attractive. In Ref.[

64], the authors pointed out that a pair of the doppelgänge black holes could share different thermodynamics. In our work, we have investigated the optical appearances of such black holes in detail. The analysis of time-like and null geodesics is examined. We found even for the black holes have the same mass and horizon radii, the ISCOs and photon spheres are intrinsically different. It follows that the shadow images cast by the doppelgänge black holes could be also different. We have studied three types of accretion models, including the thin disk, static and infalling spherical flow accretions, to establish the shadow images. Our results reveal that one can easily identify the doppelgänge black holes by their optical appearances. It would be really helpful for future observations.

On the other hand, we found the black holes with large magnetic charge in this theory play an intriguing property. Unlike the RN solution, the metric function is non-monotonic with r. This fact leads the total deflection angle to be unusual. The repulsive effect arises in the vicinity of the photon sphere, which gives rise to an unclear bright ring inside the shadow. This would be a novel feature and can be detected in future observations.

For future works, one of the interesting directions is to explore the rotating doppelgänge black holes. It is a question that will the rotation affect the difference between the rotating doppelgänge black holes? Furthermore, astronomical black holes usually contain rotation, thus the results on the rotating doppelgänge black holes would be more realistic.

One would ask, are there doppelgänge black hole solutions apart from the string-inspired Euler-Heisenberg theory? Ignoring the no-hair conjecture, the answer could be “No". Then it is valuable to check the shadow properties of doppelgänge black holes in other theories. The results could be useful to clarify the gravitational theories.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.H. and M.Y.L.; Methodology, H.H and D.C.Z.and M.Y. L.; Software, H.H. and M.Y.L.; Formal analysis, H.H., M.Y.L. and D.C.Z.; Investigation, H.H., M.Y.L. and Y.X.; Data curation, H.H.; Writing-original draft, H.H.; Writing-review and editing, D.C.Z.; Visualization, Y.X.; Project administration, H.H. and M.Y. L.; Funding acquisition, H.H., D.C.Z. and M.Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant Nos. 12205123,12305064,12365009) and Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant Nos. 20232BAB211029, 20224BAB211020,20232BAB201039).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- K. Akiyama et al. [Event Horizon Telescope], “First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. I. The Shadow of the Supermassive Black Hole,” Astrophys. J. Lett. 875, L1 (2019).

- K. Akiyama et al. [Event Horizon Telescope], “First Sagittarius A* Event Horizon Telescope Results. I. The Shadow of the Supermassive Black Hole in the Center of the Milky Way,” Astrophys. J. Lett. 930, L12 (2022).

- L. H. Liu, M. Zhu, W. Luo, Y. F. Cai and Y. Wang, “Microlensing effect of a charged spherically symmetric wormhole,” Phys. Rev. D 107, no.2, 024022 (2023) doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.107.024022 [arXiv:2207.05406 [gr-qc]].

- K. Gao, L. H. Liu and M. Zhu, “Microlensing effects of wormholes associated to blackhole spacetimes,” Phys. Dark Univ. 41, 101254 (2023). [CrossRef]

- J. M. Tejeiro S. and E. A. Larranaga R., “Gravitational lensing by wormholes,” Rom. J. Phys. 57, 736-747 (2012) [arXiv:gr-qc/0505054 [gr-qc]].

- K. K. Nandi, Y. Z. Zhang and A. V. Zakharov, “Gravitational lensing by wormholes,” Phys. Rev. D 74, 024020 (2006) doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.74.024020 [arXiv:gr-qc/0602062 [gr-qc]].

- N. Tsukamoto, T. Harada and K. Yajima, “Can we distinguish between black holes and wormholes by their Einstein ring systems?,” Phys. Rev. D 86, 104062 (2012). arXiv:1207.0047. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Bronnikov and K. A. Baleevskikh, “On gravitational lensing by symmetric and asymmetric wormholes,” Grav. Cosmol. 25, no.1, 44-49 (2019). arXiv:1812.05704. [CrossRef]

- F. Abe, “Gravitational Microlensing by the Ellis Wormhole,” Astrophys. J. 725, 787-793 (2010). arXiv:1009.6084. [CrossRef]

- J. Schee and Z. Stuchlík, “Appearance of Keplerian discs orbiting on both sides of reflection-symmetric wormholes,” JCAP 01, no.01, 054 (2022). arXiv:2111.00750. [CrossRef]

- M. Guerrero, G. J. Olmo and D. Rubiera-Garcia, “Double shadows of reflection-asymmetric wormholes supported by positive energy thin-shells,” JCAP 04, 066 (2021). arXiv:2102.00840. [CrossRef]

- F. Rahaman, K. N. Singh, R. Shaikh, T. Manna and S. Aktar, “Shadows of Lorentzian traversable wormholes,” Class. Quant. Grav. 38, no.21, 215007 (2021). arXiv:2108.09930. [CrossRef]

- J. Peng, M. Guo and X. H. Feng, “Observational signature and additional photon rings of an asymmetric thin-shell wormhole,” Phys. Rev. D 104, no.12, 124010 (2021). arXiv:2102.05488. [CrossRef]

- V. Delijski, G. Gyulchev, P. Nedkova and S. Yazadjiev, “Polarized image of equatorial emission in horizonless spacetimes: Traversable wormholes,” Phys. Rev. D 106, no.10, 104024 (2022). arXiv:2206.09455. [CrossRef]

- H. Huang, J. Kunz, J. Yang and C. Zhang, “Light ring behind wormhole throat: Geodesics, images, and shadows,” Phys. Rev. D 107, no.10, 104060 (2023). arXiv:2303.11885. [CrossRef]

- V. A. Ishkaeva and S. V. Sushkov, “Image of an accreting general Ellis-Bronnikov wormhole,” Phys. Rev. D 108, no.8, 084054 (2023). arXiv:2308.02268. [CrossRef]

- M. Bouhmadi-López, C. Y. Chen, X. Y. Chew, Y. C. Ong and D. h. Yeom, “Traversable wormhole in Einstein 3-form theory with self-interacting potential,” JCAP 10, 059 (2021). arXiv:2108.07302. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Rosa, P. Garcia, F. H. Vincent and V. Cardoso, “Observational signatures of hot spots orbiting horizonless objects,” Phys. Rev. D 106, no.4, 044031 (2022). arXiv:2205.11541. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Rosa and D. Rubiera-Garcia, “Shadows of boson and Proca stars with thin accretion disks,” Phys. Rev. D 106, no.8, 084004 (2022). arXiv:2204.12949. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Rosa, C. F. B. Macedo and D. Rubiera-Garcia, “Imaging compact boson stars with hot spots and thin accretion disks,” Phys. Rev. D 108, no.4, 044021 (2023). arXiv:2303.17296. [CrossRef]

- R. Shaikh, P. Kocherlakota, R. Narayan and P. S. Joshi, “Shadows of spherically symmetric black holes and naked singularities,” Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 482, no.1, 52-64 (2019). arXiv:1802.08060. [CrossRef]

- V. Deliyski, G. Gyulchev, P. Nedkova and S. Yazadjiev, “Polarized image of equatorial emission in horizonless spacetimes: Naked singularities,” Phys. Rev. D 108, no.10, 104049 (2023). arXiv:2303.14756. [CrossRef]

- V. Deliyski, G. Gyulchev, P. Nedkova and S. Yazadjiev, “Observing naked singularities by the present and next-generation Event Horizon Telescope,”. arXiv:2401.14092.

- H. Huang, J. Kunz and D. Mitra, “Shadow images of compact objects in beyond Horndeski theory,” JCAP 05, 007 (2024). arXiv:2401.15249. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Virbhadra, D. Narasimha and S. M. Chitre, “Role of the scalar field in gravitational lensing,” Astron. Astrophys. 337, 1-8 (1998). arXiv:astro-ph/9801174.

- J. M. Bardeen, “Timelike and null geodesics in the Kerr metric,” Proceedings, Ecole d’Eté de Physique Théorique: Les Astres Occlus : Les Houches, France, August, 1972, 215-240, 215-240 (1973).

- J. P. Luminet, “Image of a spherical black hole with thin accretion disk,” Astron. Astrophys. 75, 228-235 (1979).

- S. E. Gralla, D. E. Holz and R. M. Wald, “Black Hole Shadows, Photon Rings, and Lensing Rings,” Phys. Rev. D 100, no.2, 024018 (2019).

- V. Perlick and O. Y. Tsupko, “Calculating black hole shadows: Review of analytical studies,” Phys. Rept. 947, 1-39 (2022). arXiv:2105.07101. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Virbhadra, “Relativistic images of Schwarzschild black hole lensing,” Phys. Rev. D 79, 083004 (2009). arXiv:0810.2109. [CrossRef]

- C. Bambi, “A code to compute the emission of thin accretion disks in non-Kerr space-times and test the nature of black hole candidates,” Astrophys. J. 761, 174 (2012). arXiv:1210.5679. [CrossRef]

- P. V. P. Cunha, C. A. R. Herdeiro, E. Radu and H. F. Runarsson, “Shadows of Kerr black holes with scalar hair,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, no.21, 211102 (2015). arXiv:1509.00021. [CrossRef]

- C. Bambi, K. Freese, S. Vagnozzi and L. Visinelli, “Testing the rotational nature of the supermassive object M87* from the circularity and size of its first image,” Phys. Rev. D 100, no.4, 044057 (2019). arXiv:1904.12983. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, Y. Hou, M. Guo and B. Chen, “Imaging thick accretion disks and jets surrounding black holes,” JCAP 05, 032 (2024). arXiv:2401.14794. [CrossRef]

- J. Peng, M. Guo and X. H. Feng, “Influence of quantum correction on black hole shadows, photon rings, and lensing rings,” Chin. Phys. C 45, no.8, 085103 (2021). arXiv:2008.00657. [CrossRef]

- M. Guo and P. C. Li, “Innermost stable circular orbit and shadow of the 4D Einstein–Gauss–Bonnet black hole,” Eur. Phys. J. C 80, no.6, 588 (2020). arXiv:2003.02523. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Konoplya and A. F. Zinhailo, “Quasinormal modes, stability and shadows of a black hole in the 4D Einstein–Gauss–Bonnet gravity,” Eur. Phys. J. C 80, no.11, 1049 (2020). arXiv:2003.01188. [CrossRef]

- G. Gyulchev, P. Nedkova, T. Vetsov and S. Yazadjiev, “Image of the thin accretion disk around compact objects in the Einstein–Gauss–Bonnet gravity,” Eur. Phys. J. C 81, no.10, 885 (2021). arXiv:2106.14697. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhang, Y. Ma and J. Yang, “Black hole image encoding quantum gravity information,” Phys. Rev. D 108, no.10, 104004 (2023). arXiv:2302.02800. [CrossRef]

- X. J. Gao, T. T. Sui, X. X. Zeng, Y. S. An and Y. P. Hu, “Investigating shadow images and rings of the charged Horndeski black hole illuminated by various thin accretions,” Eur. Phys. J. C 83, 1052 (2023). arXiv:2311.11780. [CrossRef]

- H. Falcke, F. Melia and E. Agol, “Viewing the shadow of the black hole at the galactic center,” Astrophys. J. Lett. 528, L13 (2000). arXiv:astro-ph/9912263. [CrossRef]

- M. Jaroszynski and A. Kurpiewski, “Optics near kerr black holes: spectra of advection dominated accretion flows,” Astron. Astrophys. 326, 419 (1997) [arXiv:astro-ph/9705044 [astro-ph]].

- A. Uniyal, R. C. Pantig and A. Övgün, “Probing a non-linear electrodynamics black hole with thin accretion disk, shadow, and deflection angle with M87* and Sgr A* from EHT,” Phys. Dark Univ. 40, 101178 (2023). arXiv:2205.11072. [CrossRef]

- A. Uniyal, S. Chakrabarti, R. C. Pantig and A. Övgün, “Nonlinearly charged black holes: Shadow and thin-accretion disk,” New Astron. 111, 102249 (2024). arXiv:2303.07174. [CrossRef]

- S. Zare, L. M. Nieto, X. H. Feng, S. H. Dong and H. Hassanabadi, “Shadows, rings and optical appearance of a magnetically charged regular black hole illuminated by various accretion disks,”. arXiv:2406.07300.

- A. Chowdhuri and A. Bhattacharyya, “Shadow analysis for rotating black holes in the presence of plasma for an expanding universe,” Phys. Rev. D 104, no.6, 064039 (2021). arXiv:2012.12914. [CrossRef]

- S. Vagnozzi, R. Roy, Y. D. Tsai, L. Visinelli, M. Afrin, A. Allahyari, P. Bambhaniya, D. Dey, S. G. Ghosh and P. S. Joshi, et al. “Horizon-scale tests of gravity theories and fundamental physics from the Event Horizon Telescope image of Sagittarius A,” Class. Quant. Grav. 40, no.16, 165007 (2023). arXiv:2205.07787. [CrossRef]

- S. b. Chen and J. l. Jing, “Strong field gravitational lensing in the deformed Hořava-Lifshitz black hole,” Phys. Rev. D 80, 024036 (2009). arXiv:0905.2055. [CrossRef]

- S. W. Wei and Y. X. Liu, “Observing the shadow of Einstein-Maxwell-Dilaton-Axion black hole,” JCAP 11, 063 (2013). arXiv:1311.4251. [CrossRef]

- X. X. Zeng, M. I. Aslam and R. Saleem, “The optical appearance of charged four-dimensional Gauss–Bonnet black hole with strings cloud and non-commutative geometry surrounded by various accretions profiles,” Eur. Phys. J. C 83, no.2, 129 (2023). arXiv:2208.06246. [CrossRef]

- X. X. Zeng, K. J. He and G. P. Li, “Effects of dark matter on shadows and rings of Brane-World black holes illuminated by various accretions,” Sci. China Phys. Mech. Astron. 65, no.9, 290411 (2022). arXiv:2111.05090. [CrossRef]

- X. X. Zeng, G. P. Li and K. J. He, “The shadows and observational appearance of a noncommutative black hole surrounded by various profiles of accretions,” Nucl. Phys. B 974, 115639 (2022). arXiv:2106.14478. [CrossRef]

- D. G. Boulware and S. Deser, “String Generated Gravity Models,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 55 (1985), 2656.

- T. Clifton, P. G. Ferreira, A. Padilla and C. Skordis, “Modified Gravity and Cosmology,” Phys. Rept. 513 (2012), 1-189. arXiv:1106.2476.

- D. J. Gross and J. H. Sloan, “The Quartic Effective Action for the Heterotic String,” Nucl. Phys. B 291 (1987), 41-89.

- L. J. Dixon, V. Kaplunovsky and J. Louis, “On Effective Field Theories Describing (2,2) Vacua of the Heterotic String,” Nucl. Phys. B 329 (1990), 27-82.

- P. Kanti, N. E. Mavromatos, J. Rizos, K. Tamvakis and E. Winstanley, “Dilatonic black holes in higher curvature string gravity,” Phys. Rev. D 54 (1996), 5049-5058. arXiv:hep-th/9511071.

- J. T. Liu and P. Szepietowski, “Higher derivative corrections to R-charged AdS(5) black holes and field redefinitions,” Phys. Rev. D 79 (2009), 084042. arXiv:0806.1026.

- D. Anninos and G. Pastras, “Thermodynamics of the Maxwell-Gauss-Bonnet anti-de Sitter Black Hole with Higher Derivative Gauge Corrections,” JHEP 07 (2009), 030. arXiv:0807.3478.

- D. P. Sorokin, “Introductory Notes on Non-linear Electrodynamics and its Applications,” Fortsch. Phys. 70 (2022) no.7-8, 2200092. arXiv:2112.12118.

- P. Sarkar and P. K. Das, “Emergent cosmology in models of nonlinear electrodynamics,” New Astron. 101 (2023), 102003. arXiv:2203.10877.

- A. Allahyari, M. Khodadi, S. Vagnozzi and D. F. Mota, “Magnetically charged black holes from non-linear electrodynamics and the Event Horizon Telescope,” JCAP 02, 003 (2020). arXiv:1912.08231. [CrossRef]

- A. Övgün, G. Leon, J. Magaña and K. Jusufi, “Falsifying cosmological models based on a non-linear electrodynamics,” Eur. Phys. J. C 78 (2018) no.6, 462. arXiv:1709.09794.

- A. Bakopoulos, T. Karakasis, N. E. Mavromatos, T. Nakas and E. Papantonopoulos, “Exact black holes in string-inspired Euler-Heisenberg theory,”. arXiv:2402.12459.

- A. Vachher, S. U. Islam and S. G. Ghosh, “Testing Strong Gravitational Lensing Effects of Supermassive Black Holes with String-Inspired Metric, EHT Constraints and Parameter Estimation,”. arXiv:2405.06501.

- H. Yajima and T. Tamaki, “Black hole solutions in Euler-Heisenberg theory,” Phys. Rev. D 63, 064007 (2001). arXiv:gr-qc/0005016. [CrossRef]

- C. Bambi, “Can the supermassive objects at the centers of galaxies be traversable wormholes? The first test of strong gravity for mm/sub-mm very long baseline interferometry facilities,” Phys. Rev. D 87, 107501 (2013). arXiv:1304.5691. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).