1. Introduction

In recent years, the climate lost regularity in cycles and became changeable to new states [

1]. The climate changes occupied big areas with totally or partially damaging ecosystems [

2]. Human societies must deal the climate problem with the slightest responsibility in order to protect the earth from negative changes [

3].

Over the past two years, the heat dome has swept away, causing high temperatures and low humidity, accompanied by a lack of rainfall in the north of the Earth during the summers of 2022 and 2023, sparking forest fires in Canada, America, Britain, and on both sides of the Mediterranean in Spain, France, Italy, Greece, Turkey, Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. In Greenland, glaciers are melting rapidly. Summer continues for more weeks, autumn shortens, and winter progresses slowly and ends early, paving the way for spring to return quickly. The melting of ice and the separation of huge areas of it in Antarctica. The hurricanesanes increased, approaching 300 km/h, and became more ferocious and violent. There are many examples that cannot be enumerated here of the dire consequences that the Earth is currently witnessing in terms of climate change over the past two years. The suffering of human societies has increased around the world in the face of extreme climate. Difficult challenges have emerged, particularly water availability, due to disturbances in rainfall and the impact of extreme temperatures on agriculture. The environment became unhealthy due to human manipulation [

4].

In this context, researchers from all over the world have rushed to study the climate changes in each region and their repercussions on the social and economic systems of human societies in developed and developing countries [

5,

6,

7,

8]. They made good efforts and distinguished contributions. They invented more effective devices to measure the weather in order to obtain accurate data about climate phenomena. They then established mathematical models describing various climate phenomena. Hence, they developed statistical, numerical and analytical methods in treating weather data and linked them to human activities to understand the repercussions of climate change [

9,

10,

11].

In developing statistical, numerical, and analytical studies of various weather phenomena, there was, on the other hand, a new theory that began to become famous. Almost thirty years ago, the new theory about information systems was suggested as the quantum information theory. Its primary purpose was to build and operate a quantum computer. This theory developed in a parallel way and far from the issue of climate change in the world. With the spread of the issue of climate change, we were keen to develop techniques to understand the climate, so we sought the quantum information theory as a new mathematical method in studying weather data in addition to other methods currently used. The purpose here is to provide a new perspective in the study of climate variables and the interaction between them. There are quantum measures that are suitable for studying the climate.

In this manuscript we will investigate the Vancouver weather dynamics in the time domain from 2009 to 2019 by the aid of quantum mechanical measurements. The manuscript is arranged as follows; in section two we introduce the framework of the measurement technique and the preparing of the data to be suitable for it and we deduce the density matrix of the quantum system. In section three, we obtain the time evolution of the classical information, the quantum information, the decoherent information, Shannon entropy and von Neumann entropy monthly. Also, we recorded the maximum values of each case. In section four, we end with the conclusion.

2. The Mathematical Model

The novelty of this framework is configured to set up the quantum machine learning (QML) as the

dimensional feature space

F, of the dataset

in a viewpoit of the quantum information theory. Thus, we aim to formulate the dataset

in the quantum view. In the classical information system, the dataset

is provided as

matrix where

n and

d refers to the number of rows and number of columns respectively where

is the numerical value in the dataset

and

. Therefore, the

dimensional feature space

F, is represented geometrically by the Hilbert space in the quantum framework where each feature represents a specific phenomenon provided in the standard basis vector. Consequently, the

dimensional feature space

F, is configured by standard bases

where each column of

is represented by the standard basis and each row of

is formed by an arbitrary non-normalized vector

Hence, an arbitrary non-normalized vector

can be formed in terms of the standard bases

as:

Hence, the vector

is normalized if it is taken in the form

as follows:

where

such that

A given dataset

, is defined on the set of real numbers

or the set of complex numbers

according to domains of

’s elements. Indeed, the dataset

, cannot be treated in the quantum mechanics, since it is not a square matrix. In this respect, the new quantum state

is defined to describe

, provided by the square matrix. The quantum state

is the normailzed square matrix of order

and is introduced as:

which expressed in terms of standard bases

as follows:

where

The state

has three important facts. Firstly, it is always a mixed state. Hence, it has always a noise. Diagonal elements

represent the classical information denoted by

.

is the information that can be directly observed, stored, and processed using traditional digital technologies.

is investigated by:

Non-diagonal elements

are the joint information of ket basis

and bra basis

which describes the quantum information. These elements disappear in the classical information but exist in the quantum information theory. Hence, the quantum information theory forms a new type of the information which does not exist classically.

is fundamentally different from

which is due to the unique properties of quantum systems, such as superposition.

is checked by:

Clearly, two informaation terms CI and QI, yield the trace of

which is written as:

Hence, the new term is also defined as

and is known as the linear entropy or purity. Here this term is named the decoherent information and denoted by

.

refers to the private information type that is not directly accessible or measurable with matrix elements like

and

is detected by the relationship as:

If

is the pure state, then the sum of

and

is equal to one and

does not exist. Thus, Equation (

7) becomes as follows:

If

is the mixed state, then the sum of

and

is less than one and there is a gap which forms the inequality in Equations (

7) and (

9). Therefore, a new term achieves the equality in the preceded inequality.

describes a gap between one and the sum of

and

with using Equation (

8) in what follows:

The information has distinct realms, each with its own unique characteristics, and through which we can understand systems. The quantum information system can be divided into three different categories; , , and . According to the quantum informative view, the dataset , is manipulated by the formation of over the dimensional feature space F. Consequently, the quantum machine learning is defined here successfully.

To study the noise and the ambiguity of the information system, the entropy is used here to handle this mission. Indeed, the entropy is valid to measure the noise with a high accuracy. Shannon entropy is used to determine the noise of the classical information and is introduced as [

12]:

where

and depends on the diagonal terms of

always exists for all cases of

von Neumann entropy is a precise and widely-used quantum measure due to its strong theoretical foundations and it is also known as nonlinear entropy. It is a quantum analogues of the classical Shannon entropy and is introduced as [

13]:

where

is the eigenvalue of the quantum state

. von Neumann entropy can be applied to any quantum state, whether pure or mixed, and is not limited to particular systems or states. This makes it a versatile and widely applicable quantum measure. Consequently,

if

is a pure state and

if

is a mixed state. Hence,

measures the noise of the decoherent information.

3. Quantum Weather Model

In this setting, we propose this novel technique to investigate the weather dynamics in Canada as a good exercise. Climate changes in Canada are in the spotlight here. Canada characterizes a wide range of both of geological and meteorological regions. It has a cold continental climate with winters lasting for six months and heavy snow falls, covering vast areas. In addition, the rainfall falls with great annular rates over all provinces and territories. Temperatures vary in the summer from a region to a region [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Thus, no one can study totally the climate in Canada. Therefore, the study is focused on a local region like Vancouver city. Some of basic information is provided about the geography and the climate of Vancouver city. Vancouver is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia province. It lies between Burrard Inlet to the north and the Fraser River to the south. The Strait of Georgia, to the west, is shielded from the Pacific Ocean by Vancouver Island. It is one of Canada’s warmest cities in the winter. Vancouver’s climate is temperate by Canadian standards and is marine west coast. In the summer, it is dry [

18].

Vancouver weather dataset is investigated by the weather dataset as an example for the QML. The dataset is formed of ten weather variables and 4017 records from on January 2009 to 31

th December 2019 [

19]. Here, names of weather variables are the maximum temperature (K), the minimum temperature (K), the dew point (K) where K is Keliven, the cloudcover (%), the humidity (%), the precipitation (mm), the total Snow (cm), the pressure (bar), the wind direction degree, and the wind speed (km/h) respectively.

In this setting, consider the quantum ten-dimensional feature space of bases and to represent the weather model with this novel technique. Weather vraiables are formulated in the quantum ten-dimensional feature space as the maximum temperature , the minimum temperature , the dew point , the cloudcover , the humidity , the precipitation , the total Snow , the pressure , the wind speed and the wind speed where the wind speed and the wind direction are solved into the wind speed and the wind speed respectively.

Thus, an arbitrary instance pure weather state

gives the numerical data of the

row in the weather dataset

and can be written as:

where

’s are real values. The daily quantum weather state is symbolized as

where

d is the day order in the month,

m is the month order, and

y is the year. If the date is 03/01/2009, then the corresponding daily quantum weather state of the same date is written as

Consequently with using Equations (

1) and (

13), the quantum daily weather state

can be described by a numerical data in terms of ten bases as follows:

where the state

gives the data record in Vancouver weather dataset.

It is obvious that the daily quantum weather state is unbalance because of all data have distinct units. Therefore, it necessary that all data is reformed in dimensionless data in order to be balanced. To achieve this aim, the maximum reference of each column is calculated from

to

in the Vancouver weather dataset on the data in

Table 1. In the maximum reference (Max- Ref) approach, the daily quantum weather state

can be reformed in dimensionless data where each value of a weather variable is divided by the corresponding maximum reference value of the same weather variable as in

Table 1, in what follows:

where Equation (

15) is non-normalized. In subsequent by Equation (

2), the state

becomes normalized as:

Actually, the daily quantum weather state is pure normalized. Each numerical value of dimensionaless weather variable is affected by other values of all variables using the normailzation constant. All same computations are established over all instance weather states in this statistics to obtain normalized quantum pure daily weather states. According to the statistics, we have 4017 normalized daily quantum pure weather states from to .

How to construct the state

over an arbitrary date interval from the

row to the

row, the first step, the weather dataset

is modified into a new formalism which each column is divided by the corresponding maximum reference according to

Table 1. Thus, the new dimensionless weather dataset

is built. The second step, the state

from the

row to the

row is computed by Equation (

3) as:

This statistics is partitioned according to months. Thus, there are 132 covariance matrices

...,

and

which correspond to

, and

, respectively. The monthly quantum state

is determined from

to

, by Equation (

17):

and the corresponding matrix of

is computed as:

Elements of the state expresses for the classical information which appear in diagonal elements and the quantum information which appear in non-diagonal elements. In fact, each element matrix is influenced by all weather dimensionaless variables because of the term Vancouver ether dataset is checked later by quantum informative measurements (the classical information, the quantum information, the decoherent information, Shannon entropy and von Neumann entropy).

4. Discussion and Results

In order to study the climate, one needs to visualize the time evolution of the climate variables and we can get a comprehensive understanding of each one of them. This allows us to detect extremes, trends, and the overall climate characteristics.

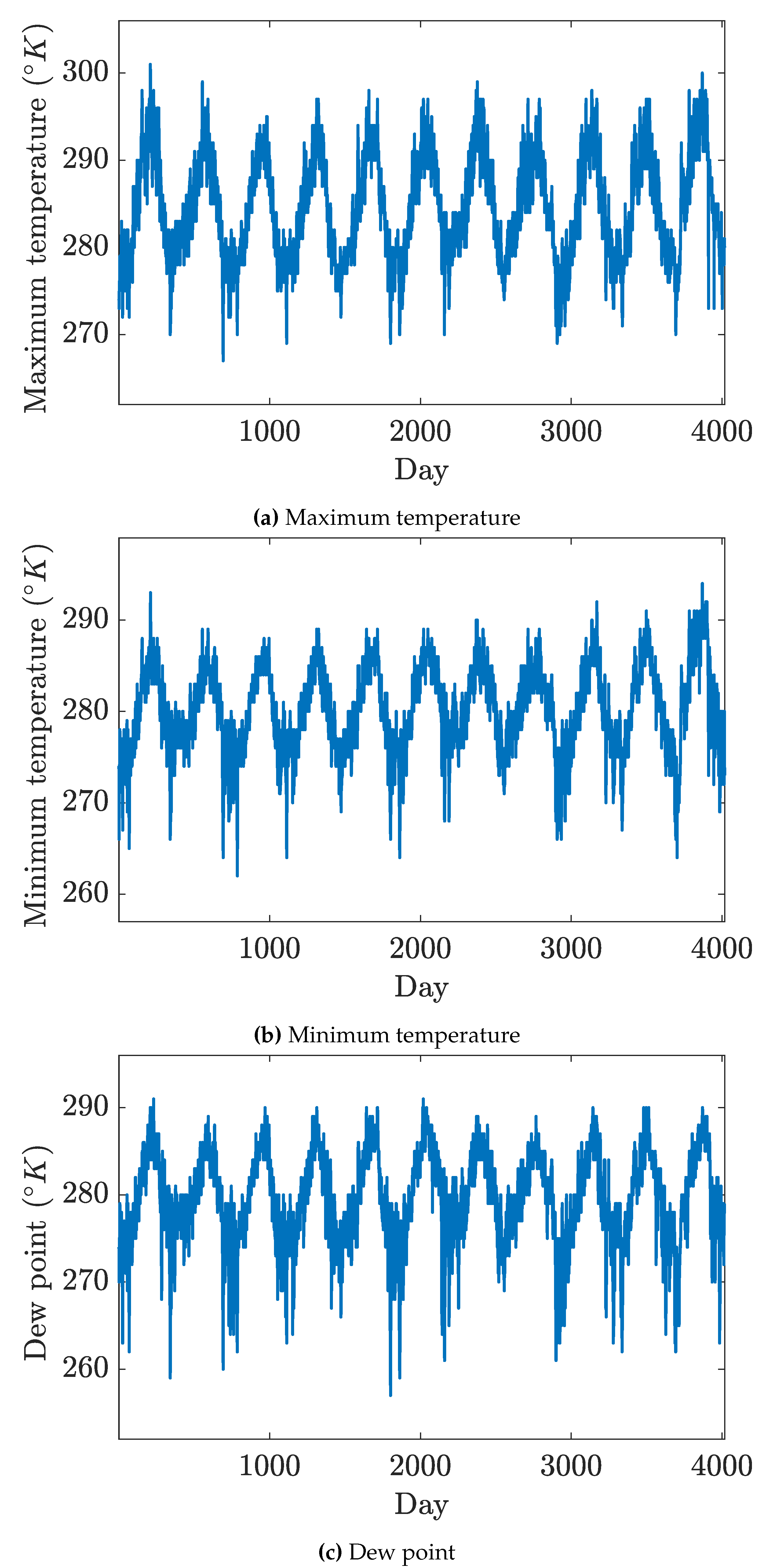

Figure 1, shows the time evolution of each climate variable.

Figure 1 and

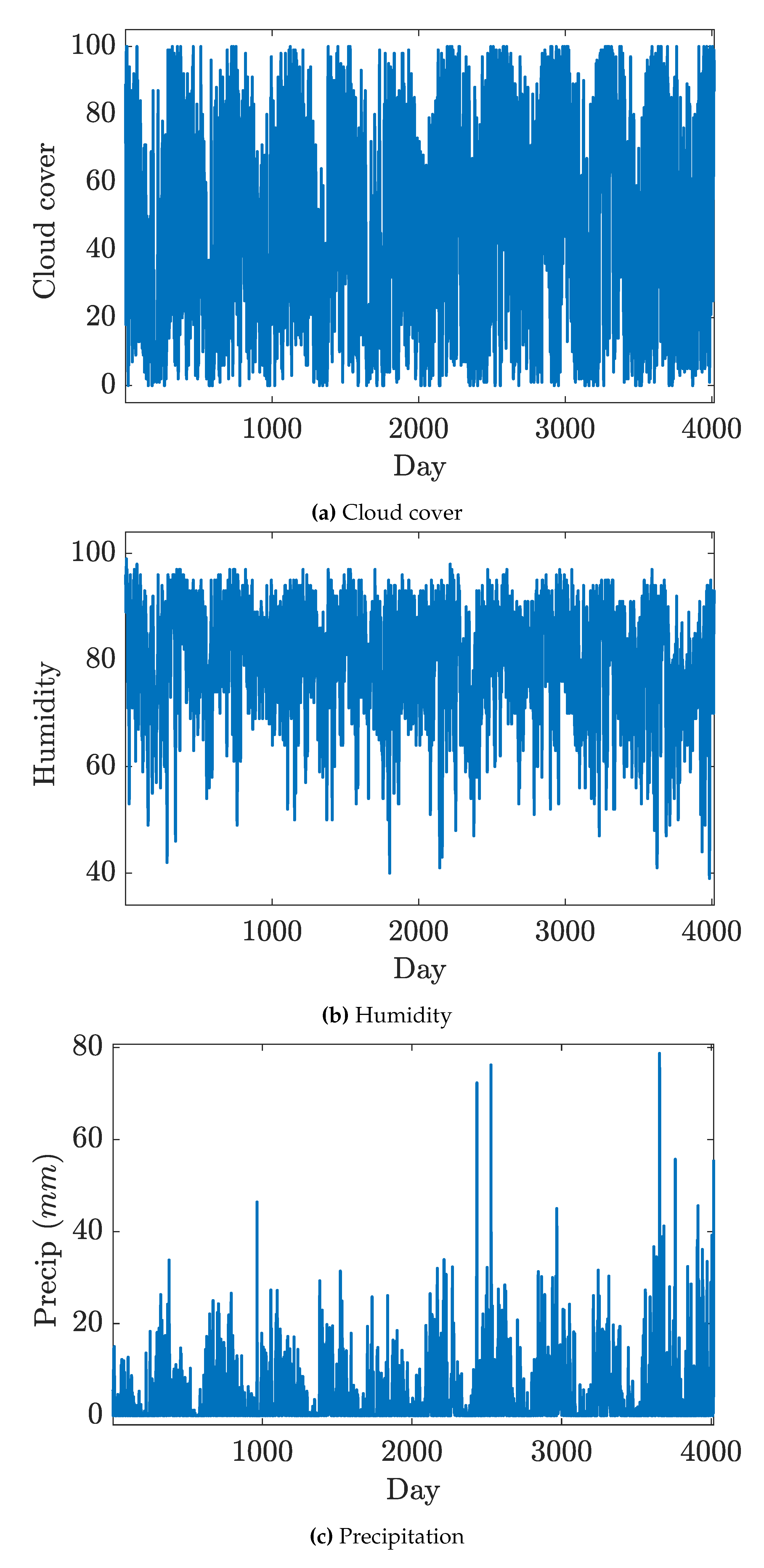

Figure 1, presents the evolution of the maximum temperature, minimum temperature, and dew point in Keliven. It is clear that we have a cyclic evolution yearly, whereas the maximum of each cycle is reached in the half of each year and the minimum is recorded at the beginning and the end of each year. Indeed, the cloud cover and humidity percentage have no cyclic evolution as shown in

Figure 2,

Figure 2. If we look insight, we can detect a trend of increase in the maximum precipitation values with an extreme values in 2015 as shown in

Figure 2.

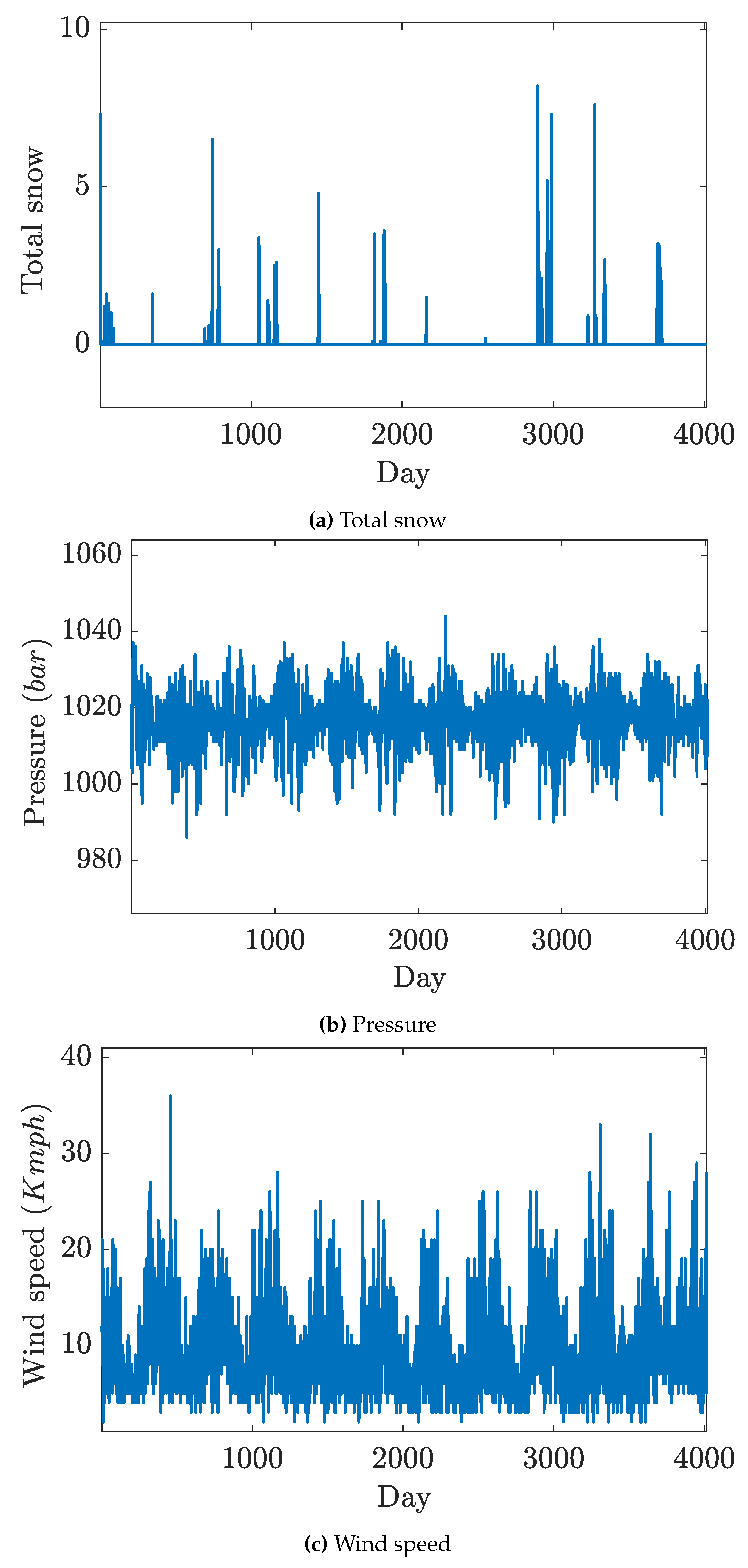

Figure 3 presents a roughly oscillation without any cyclic evolution whereas the mean values are approximately constant. Snow is a discrete time phenomena happening per year, so as in

Figure 3, total snow is recorded in between sequential two years. Indeed the total snow has its extreme in 2016 and 2017. In

Figure 3, wind speed has a cyclic evolution with fluctuations in each year. Also, the minimum value are approximately stationary with respect to the variation in the maximum values.

In this analysis of a time evolution in the feature space, the classical information CI, the quantum information QI, the decoherent information DI, Shannon entropy and von Neumann entropy are plotted against the months as the time units from Jan/2009 into Dec/2021. Information has distinct realms, each with its own unique characteristics, and through which we can understand systems.

The classical information, the quantum information, the decoherent information, Shannon entropy and von Neumann entropy are computed for monthly mixed states by Equations (

5), (

6), (

8), (

11), (

12), (

17), (

18), (

19), and all numerical values are mentioned in tables.

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 refer to the classical information, the quantum information, the decoherent information, Shannon entropy and von Neumann entropy rerspcetively. Each table includes 132 numerical values refers to years from 2009 to 2019 vertically and to months horizontally from January to December.

In

Table 2, values of CI provide the effect individually of each weather variable of a range

In

Table 3, values of QI describe the mutual interaction of pair of two variables of a range

. Obviously, QI values enlarge comparison with values of CI. Therefore, the effect of QI is greater than the effect of CI in this system. In

Table 4, DI values are small relative to QI and CI and has a range

. In

Table 5,

values describe the classical noise of CI and is ranged by

in

Table 6,

values describe the noise of DI of a range

. It noted that

values weaken relative to

values.

In order to predict quantum informative measures for proceeding years, the time evolution of quantum informative measures can be categorized by oscillating forms for the monthly evolution. We can adopt the time series function like Fourier series as a fitted function to express for quantum informative measures of the time

t which takes the form:

where the time unit is the month and varies from 1 to 156 to express for years from 2009 to 2021. Also,

are real parameters which are detemined by the fitting curve method. The fitting curve method is applied from 2009 to 2017 where

and we compare predicated results with computational values in

Table 2,

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6 from 2018 and 2019, where

. Hence, we predict values for each quantum informative measure for 2020 and

where

Parameters of Equation (

20) are determined In

Table 7 for

,

,

,

and

.

Table 8 presents a comprehensive analysis of the statistical parameters for predicted data CI, QI, DI,

, and

based on data from 2009 to 2019. The parameters evaluated include maximum error

, average error

minimum error

standard deviation

and Pearson correlation

Among the models, CI demonstrates the lowest errors, with

and

, indicating more consistent predictions with minimal deviation. Conversely, Shannon entopy shows the highest errors, with

and

. The minimum error values across all models are in the range of

with CI having the lowest at

and Shannon entropy the highest at

. The standard deviation, which reflects the spread of prediction errors, is lowest for CI at 0.0036 and highest for S_Pred at 0.0092, reinforcing the observation that CI offers more stable predictions. In terms of performance accuracy, CI scores the highest with

P at 0.8619, indicating superior reliability, while QI has the lowest accuracy at 0.4705. Overall, the table suggests that CI outperforms the other models in terms of error minimization and prediction accuracy, making it the most reliable among the five models analyzed.

In

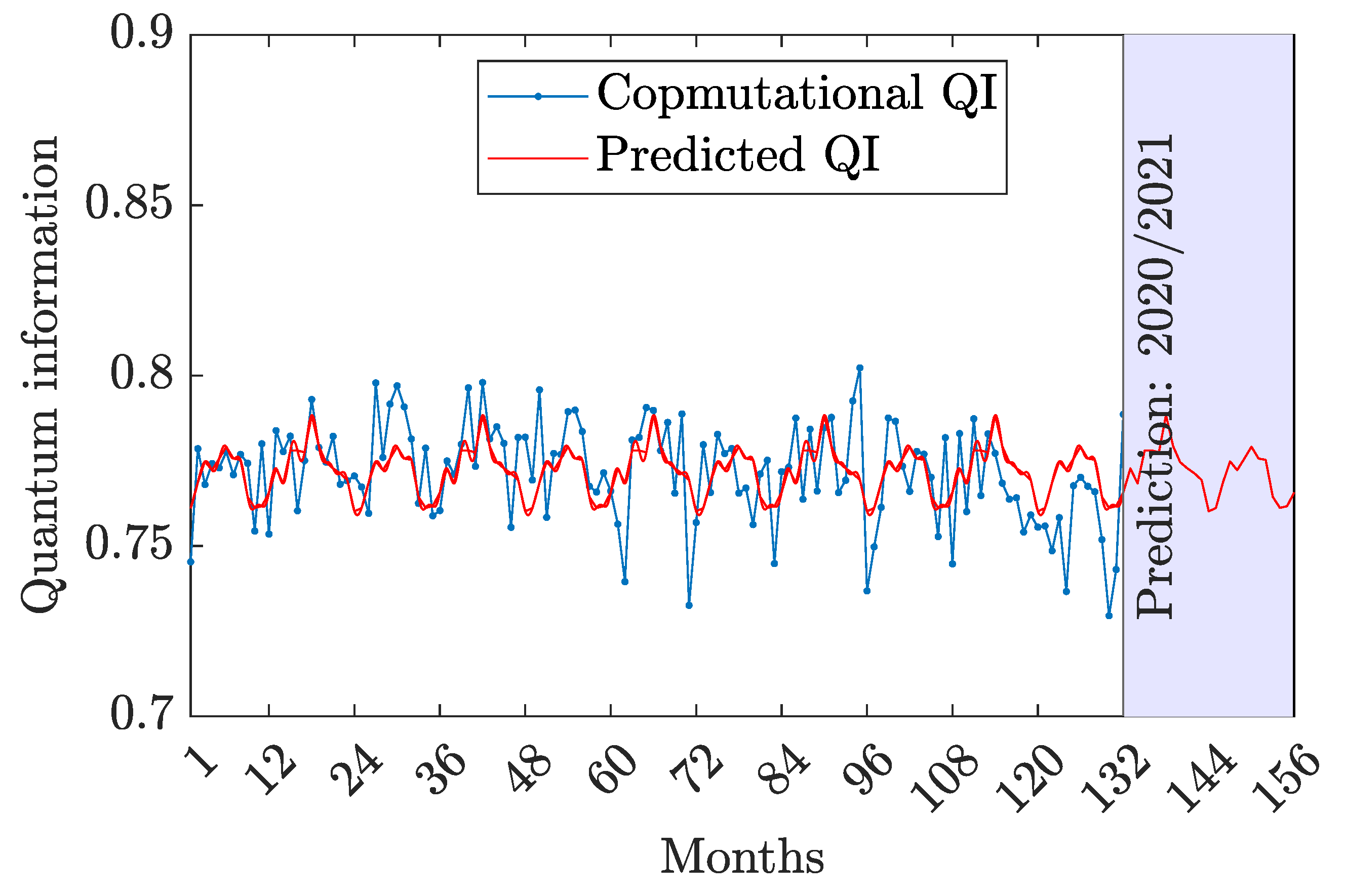

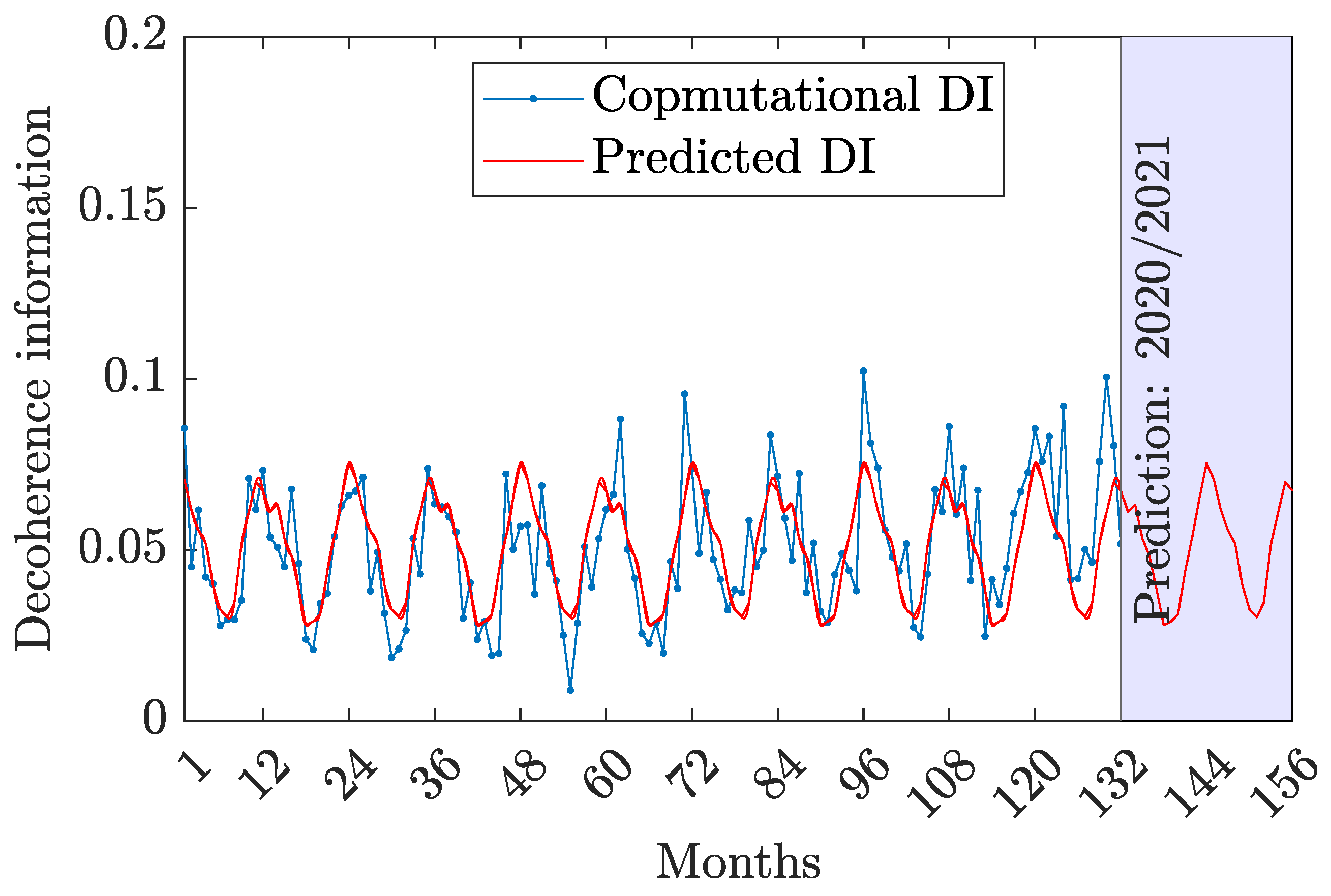

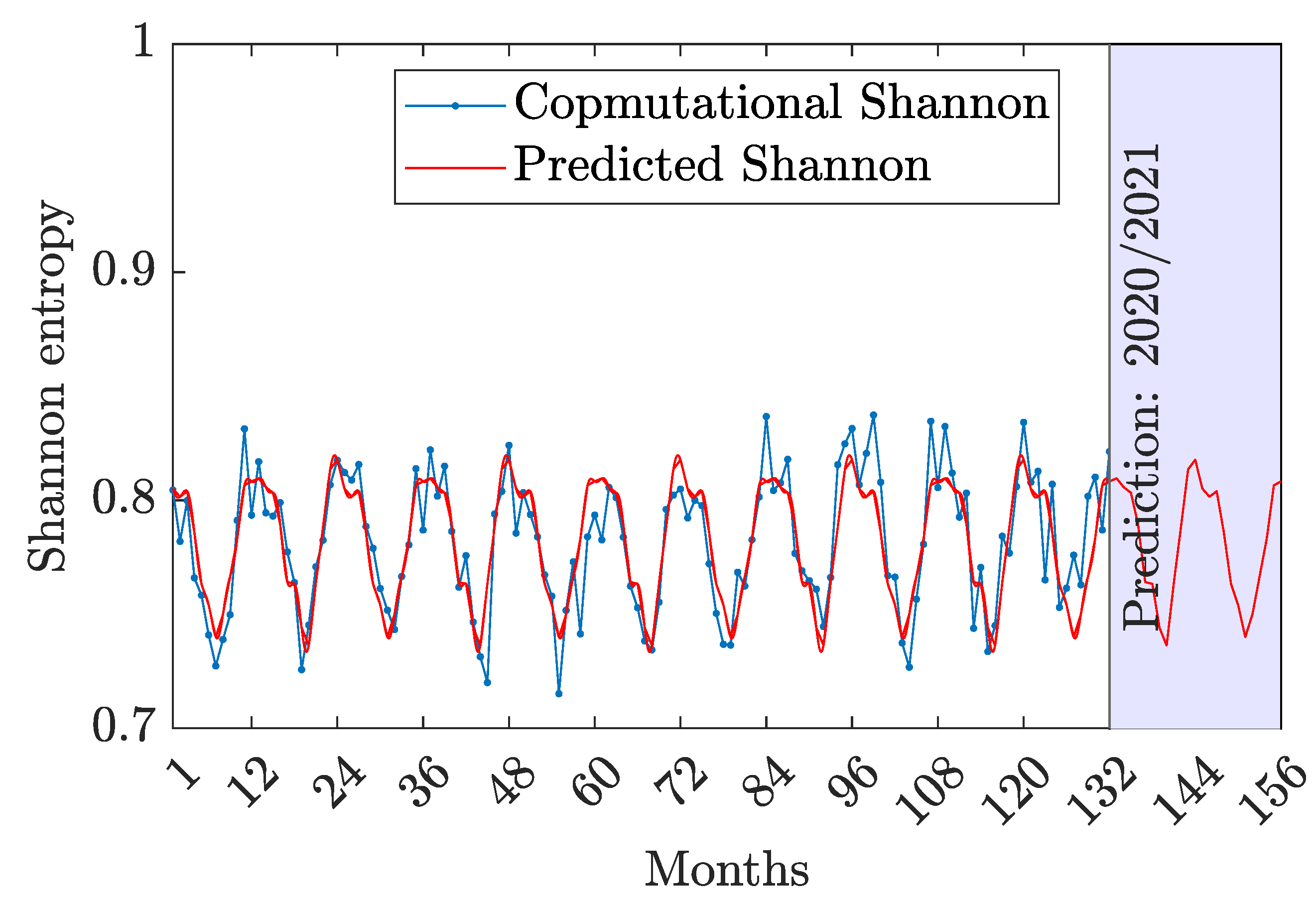

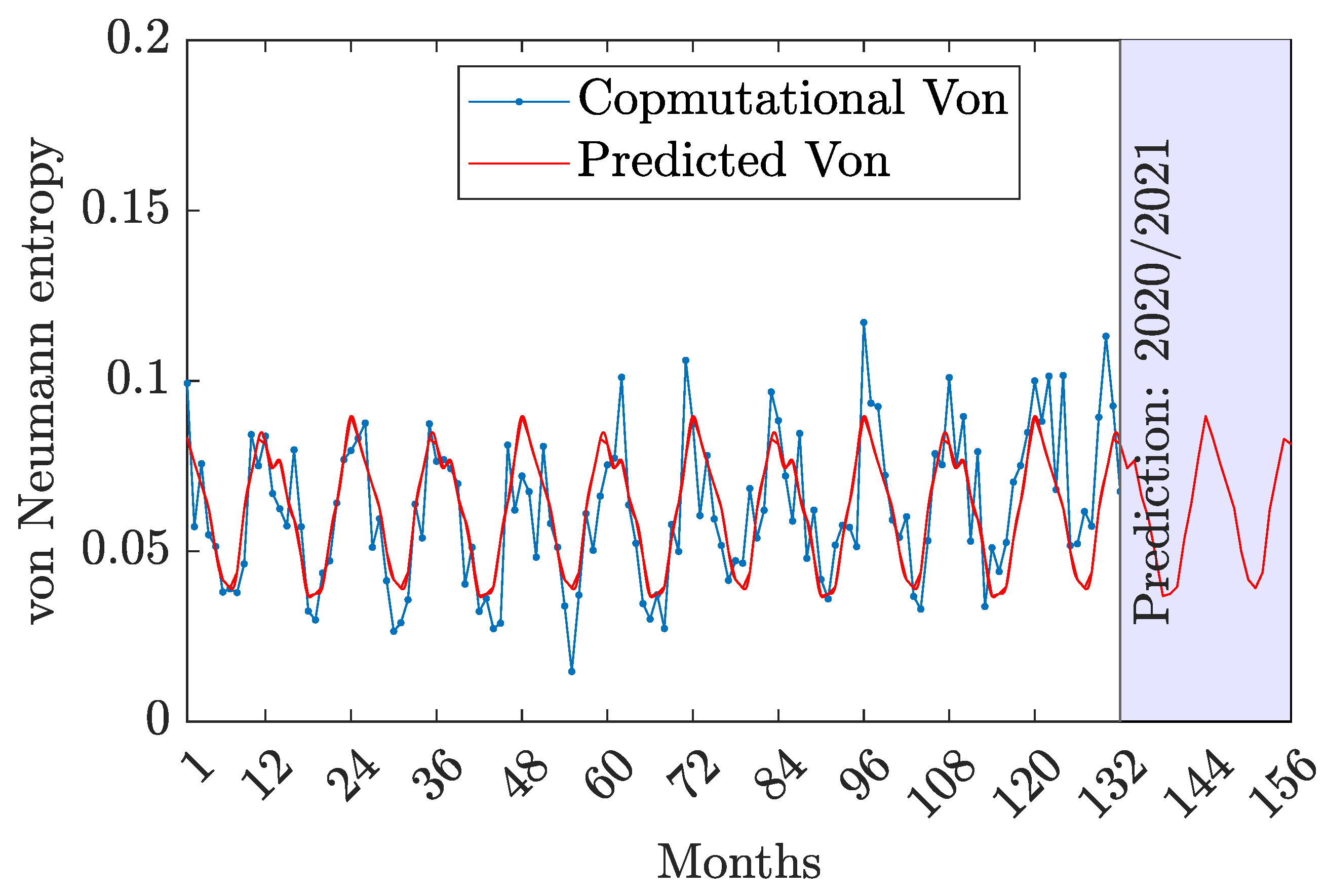

Table 9, all predicted values of each quantum informative measure are recorded from 2020 to 2021 based on months from

Each quantum informative measure investigates monthly mixed weather states. In all figures, each quantum informative measure is plotted versus the months as the unit time from 1 to 156 where the month domain

provides the computational values and the month domain

presents predicted values, especially future predicted values from 133 to 156. The blue curve represents computational values and the red curve shows predicted values. The shaded area on the right figure during the period

marks the prediction period for 2020 and 2021. Predicated curves are plotted by Equation (

20) and Tables (

Table 7,

Table 9). All curves are taken in waveforms.

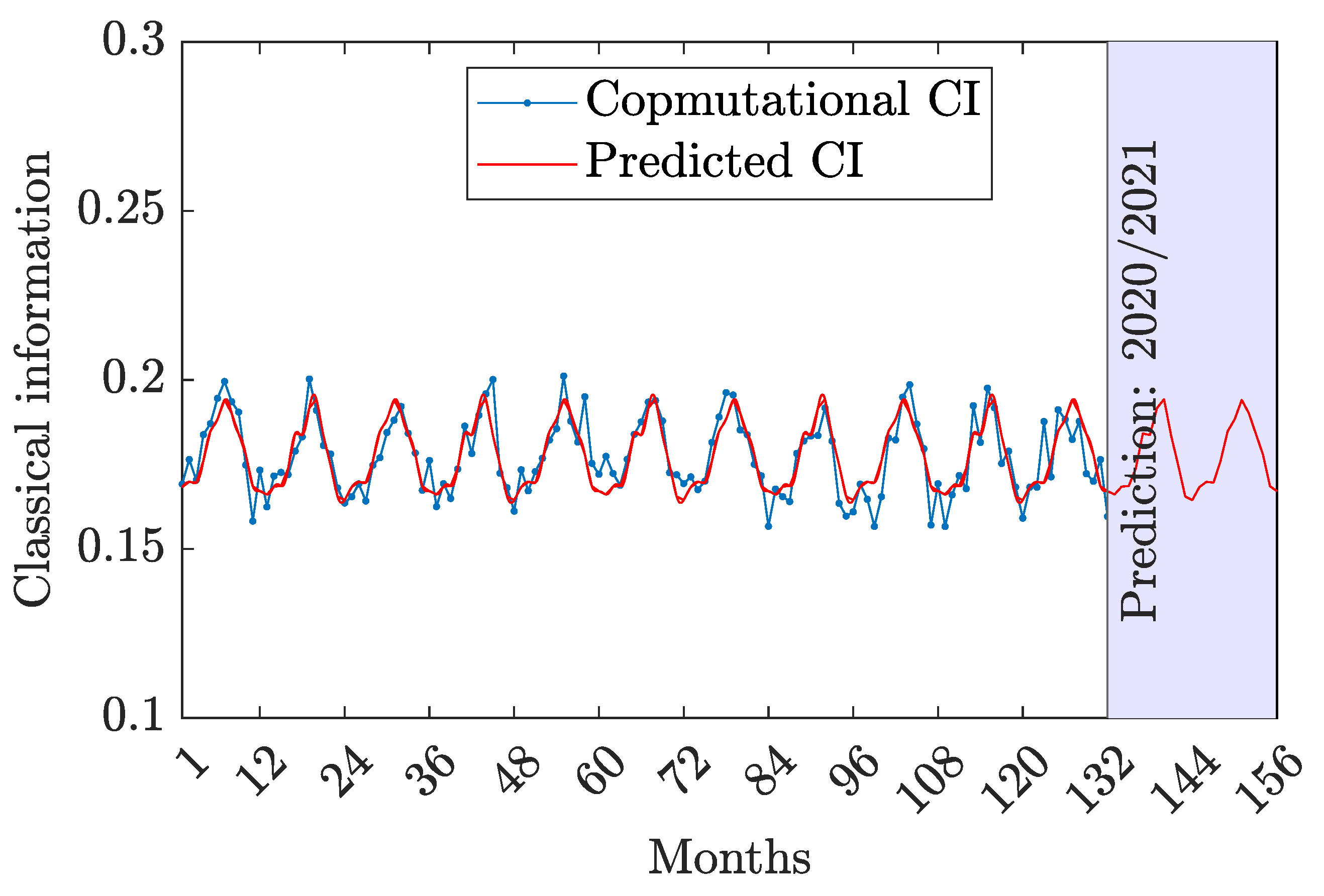

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show a comparison between three distinct types of the information; CI, QI, and DI, respectively. In

Figure 4, the classical information is plotted by

Table 2,

Table 7 and

Table 8 and Equation (

20) versus months in two curves. Two curves are close in nearly sinusoidal forms with a cyclic behavior. It has maximum extremes in summer and minimum in winter.

In

Figure 5, by

Table 3,

Table 7 and

Table 8 and Equation (

20), the quantum information is plotted against months in two curves. The computational curve fluctuates far the predicted curve. The computational curve appears in an irregular behavior while the predicted curve has regular behavior. However, it depicts fluctuations in QI with no clear long-term increasing or decreasing trend.

By

Table 4,

Table 7,

Table 8 and Equation (

20), the decoherent information is provided graphically versus months by two curves in

Figure 6. The computational curve undergoes slight fluctuations but the predicated curve is regular. Indeed, the system exhibits a high value of the quantum information relative to the classical information which means that the model behaves like a real quantum model rather than a classical one. When the information measures are compared; QI exhibits the highest value with respect to CI and DI. This proves that a treatment of the quantum mechanical system will provide with considerable information with respect to classical one.

Investigating two distinct types of entropy;

and

is shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 respectively. In

Figure 7, Shannon entropy is plotted against months by

Table 5,

Table 7 and

Table 8 and Equation (

20), in two curves. Clearly, the predicted curve is close to the computational curve with some slight fluctuations after

Shannon entropy describes a noise in the classical information with high values comparing with classical information values.

In

Figure 8, von Neumann entropy is plotted against months by

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8 and Equation (

20), in two curves. von Neumann entropy fluctuates in recent years and has small values which are near to values of the decoherent information. Indeed, the system exhibits a high value of Shannon entropy with respect to the von Neumann entropy approximately 10 times it. There is an oscillatory behavior in both measures due to the periodicity in weather dynamics. Measured values of von Neumann entropy prove the uncertainty of predicting the weather for a month relative to the Shannon entropy.

The analysis of Vancouver’s weather dynamics from 2009 to 2019 through the lens of quantum information theory provides a unique perspective on climate data interpretation. Using concepts from various studies, such as the application of fuzzy logic in decision making [

20] and the exploration of quantum entropy in physical systems [

21,

22], the research integrates advanced mathematical frameworks to model weather patterns. Additionally, insights from quantum classification algorithms [

23,

24] and the role of entanglement in complex systems [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29] further enhance the robustness of this analysis. By synthesizing these diverse approaches, the study aims to reveal intricate relationships in weather dynamics, potentially leading to improved predictive models and a deeper understanding of climatic shifts in the Vancouver area.