1. An Extended Introduction

1.1. “Definition” of Complex Systems

When we ask a question about the definition of a complex system, rhetorically or not, we are faced with whether the existing language of science can describe a world of complex systems in which there is a rule - "more is different" [

1]. As we were creating the structure of this paper on the use of permutation entropy in complex system sciences, particularly hydrology, I came across the paper "Complex Systems at the Center of Attention: The Next Steps After Nobel Prize in Physics 2021" written by Bianconi et al. [

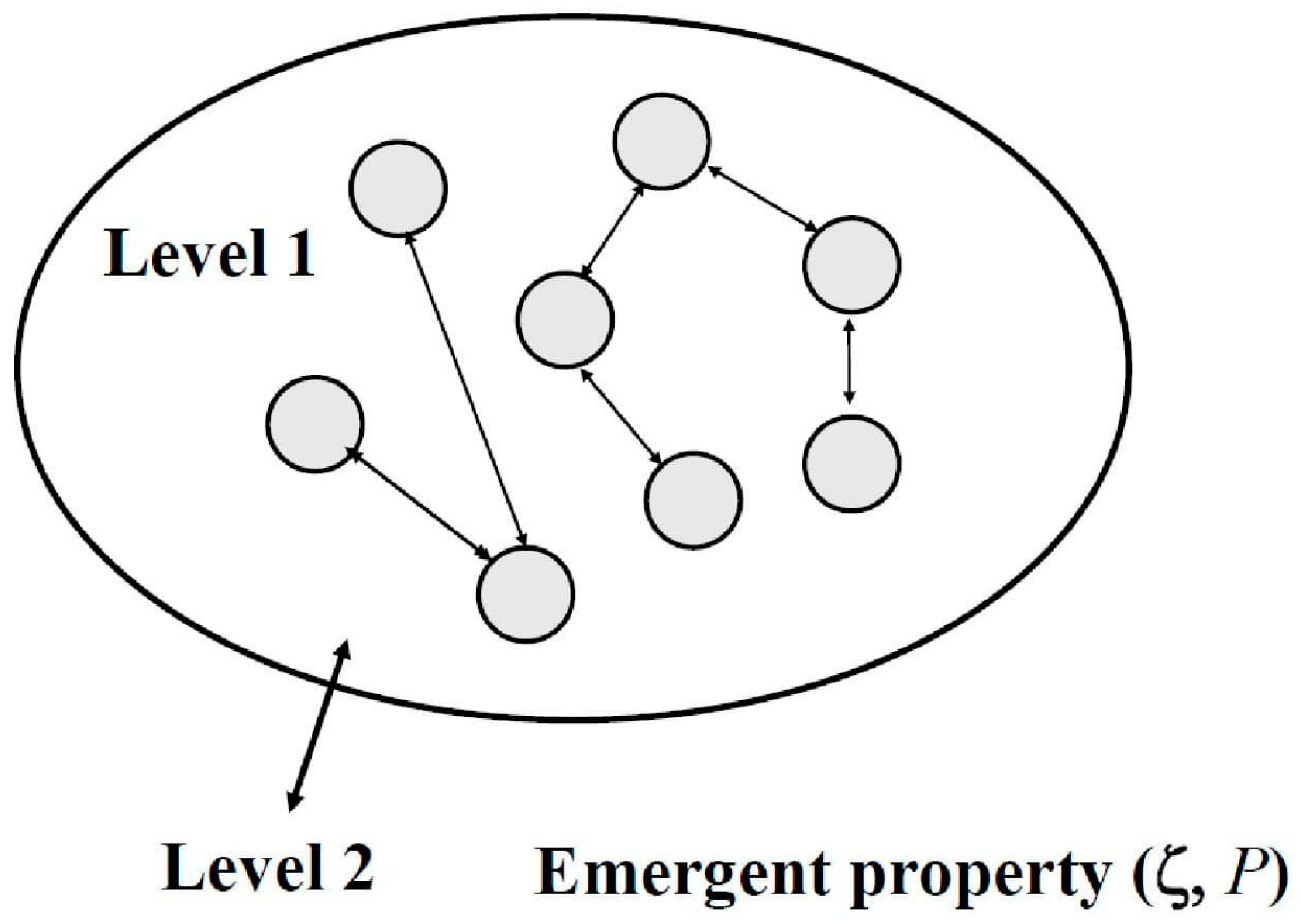

2], which was published in JPhys Complexity. This editorial presents the editorial board's perspective on the current state and future projections for exploring complex systems, organized around six key themes. The majority of comments lack significant insights that would contribute to advancing complex systems research currently or in the future. Additionally, some comments are more akin to literary descriptions than substantive scientific contributions. We consider a complex system (

Figure 1) as it was done in Mihailović et al. [

3], i.e.: “… as a collection of entities (circles). Each component interacts with others via simple local rules and the possibility of feedback (arrows). When they interact, a new feature arises (level 1). The complex system cannot be decomposed nontrivially into a set of basic entities for which it is the logical sum [

4] (to have the character of an emergent phenomenon, this new feature is completely unexpected [level 2]). The new property is characterized by (ζ, P), where ζ represents data, and P is the probability distribution.” This is perhaps the most concise definition that describes a complex system's nature but does not indicate how to interpret that system holistically, considering all its characteristics. Complex systems are characterized by several distinct properties that arise from the interactions among their components. These properties make complex systems difficult to model and predict, as they often exhibit behaviors that are not apparent when examining individual parts in isolation.

We enumerate their properties in accordance with the principles outlined by Arshinov and Fuchs [

6].

Emergence and

self-organization are the two main concepts when we consider a complex system. Aspects of emergence are:

synergism,

novelty,

irreducibility,

unpredictability,

coherence/correlation, and

historicity. Self-organization includes the following aspects:

systemness,

complexity,

cohesion,

openness,

bottom-up-emergence,

downward causation,

nonlinearity,

feedback loops,

circular causality,

information,

relative chance, and

hierarchy.

1.2. What Can We Do to Model Complexity or Complex Models?

Members of the complex system community simplify the above definition reducing the complex system to a system with many degrees of freedom and nonlinear interactions. These conditions are found in all natural phenomena. Otherwise, we would be living in a purely linear world. Consequently, they cannot be sufficient assumptions for analyzing complex systems. For example, the edge of chaos, i.e., the transitional space between order and disorder, exists within various complex systems but does not distinguish between complex and noncomplex systems [

7]. Why is this the case? Because certain properties of complex systems are not essential for their classification. We will illustrate this point by modeling a complex system when the model shows none of the most discriminating properties of complexity using a simple mathematical model [

8]

for a group of point particles with position vectors

and velocities

and a force due to interactions with other particles having a direction

for

i-th particle. The left term on the right-hand side of Eq. (1) represents a repulsion between the particles, while the second term is an attraction that tries to line up their motion. The force is made stochastically by adding a small random number to it. We can ask if the simple mathematical model for particle points is based on Eq. (1) shows any of the characteristics that we have argued are discriminatory separating complex and non-complex systems. There are no visible signs, such as a hierarchy of effective degrees of freedom, or the emergence of strategy as a more meaningful description of an element of the system. On the contrary, it seems the model describes a straightforward system with competitive rejection (short-range) and long-term attraction (longer-range), which is often found in physics. However, Eq. (1) has been effectively used to model the dynamics of fish shoals [

8], which is undoubtedly a complex system. How can this simple system model a complex system (fish shoals) since that model shows none of the most discriminating features of complexity? There are some reasons for participating in a possible response. For example, the restrictiveness of the criteria, using the model to describe the interactions between point particles rather than fish, and finally, does the model still represent a complex system? Consequently, based on the above, we should classify many simple physical systems as complex. The resolution to this puzzle is the following: describing complexity is not the same when we describe a particular facet of a complex system. The model described above focuses on the mechanistic dynamics of fish shoals, which coincidentally resembles the type of model used to illustrate the interactions of particles governed by repulsive and attractive forces. However, it is important to recognize that fish are not mechanistic entities in the same way that particles in a force field are. Consequently, such models do not provide meaningful insights into complexity or allow us to determine what constitutes complexity within a complex system. While we can model complex systems, this does not imply that we can effectively capture the essence of complexity itself. Currently, there is no comprehensive theory that addresses this challenge. Many existing models are designed to answer a limited set of questions, which can restrict our understanding. Nevertheless, systems that incorporate strategic elements—such as agent-based models of financial markets—represent significant progress toward addressing this paradigm. These models move beyond simplistic representations and offer a more nuanced understanding of complex behavior. While they still provide limited answers, they pave the way for deeper insights into the complexities inherent in dynamic systems.

1.3. Complexity and Time Series Analysis

Natural fluids are exemplary physical complex systems. Hydrologists design their models heuristically, varying in levels of sophistication. These models enable understanding of complex hydrological processes, enhance predictive capabilities regarding hydrological phenomena, identify significant trends, facilitate flood risk assessments, improve access to data quality, and inform effective water resource management strategies. As previously noted, the complexity of a complex system cannot be fully modeled. It is essential to know that even models have their complexities, which can raise questions about the results' reliability. Although the above subsections appear lengthy and unnecessary for this review, they could be condensed into a concise and useful summary of the concept of complexity from both epistemological and scientific perspectives. Across all scientific disciplines, the available information is generally limited to what has been observed or measured, typically presented as (i) equidistantly ordered numbers or (ii) converted into time series arrangement. Time series are a

natural source of information about phenomena, yet they convey a message that is locked or encoded. From these time series, it is possible to calculate complexity measures for both low-dimensional systems, such as coded strings of symbols (e.g., measured quantities, text, computer code, proteins), and high-dimensional systems (e.g., ecosystems, brain activity, telecommunications networks, computer systems, biological systems, social structures), which require methods from network science [

9]. Recent efforts have aimed to establish a complexity hierarchy between the primary variable (master variable) and other system components that affect it [

10].

Historically, Kolmogorov complexity (approximated via the Lempel-Ziv algorithm [

11]) and Shannon entropy were the primary measures used to assess complexity until the early 21st century. The introduction of permutation entropy (PE) by Brand and Pompe [

12] in 2002 expanded the toolkit for complexity analysis. It is an intrinsic measure of complexity in time series analysis, characterized by its unique properties and advantages over traditional methods. Its key features include a foundation in ordinal analysis, robustness against noise, invariance properties, and computational efficiency. This information measure has quickly found applications across a wide range of scientific fields: biomedical sciences [

13,

14,

15,

16], econophysics [

17,

18], signal processing [

19,

20], climate research [

21,

22], laser physics and geophysics [

19,

23], machine learning [

20] as well as in hydrology ([

24,

25,

26,

27,

28], among many others).

In this paper,

Section 2 provides a brief overview of the development of permutation entropy from 2002 to 2024, while

Section 3 presents an outlook on the application of permutation entropy in hydrology.

2. Permutation Entropy. Its Advantages and Limitations

Permutation entropy (PE) is a non-parametric information measure that quantifies the degree of disorder or complexity within a time series by examining the order relations among its values. It is robust to noise and considers the temporal ordering of values. PE of a time series

is calculated through four steps. (1) creating permutations for a given order

, transforming the time series into permutations based on the order of

. (2) calculating probabilities of each permutation. (3) calculation of entropy

where

is the probability of each permutation

. PE value ranges from 0 to

with lower values that indicate more ordered sequences and higher values indicating randomness, and (4) normalization: The permutation entropy can be normalized to yield values between 0 and 1 by dividing the calculated PE by

. This information measure provides substantial theoretical and practical advantages, establishing itself as a critical methodology in comprehensive time series analysis. Here are some key advantages. (1)

Intuitive background. The fundamental intuition recognizes that sequential patterns carry inherent information about a system's complexity [

29]. (2)

Computational efficiency. It is seen through: high-speed calculation, low computational overhead that is efficient for analyzing high-frequency data, and minimal memory requirements providing reliable estimation of entropy from relatively small sample sizes [

13,

29]. (3)

Robustness to noise. PE demonstrates remarkable robustness against noise, highlighting its ability to deliver consistent and reliable performance even in the presence of noise within input data or the surrounding environment. This critical property plays an essential role across a wide range of fields, including auditory perception, machine learning, and signal processing, as well as in specialized domains such as biomedical engineering and financial analytics [

13,

18,

30]. (4)

Minimal parameter requirements. One of the primary advantages of PE is its nearly parameter-free nature, which contributes to its high adaptability and ease of implementation. In contrast to many other techniques, PE significantly reduces the complexity typically associated with extensive parameter tuning, allowing users to apply it more readily across various contexts [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. (5)

Discrimination of dynamics. One of the most remarkable properties of permutation entropy is its ability to distinguish between different types of dynamical behavior, such as periodic and chaotic dynamics [

12,

29]. This capability stems from its distinctive approach to quantifying the order relations among data points in a time series. Numerous studies have further explored and enhanced this property, highlighting its versatility and effectiveness in analyzing complex systems [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39].

Despite its advantages, permutation entropy does have some drawbacks, which we will briefly outline. (i)

Sensitivity to noise. PE is particularly vulnerable to noise, especially broad-band noise. Its performance degrades quickly when noise levels increase, which can lead to inaccurate assessments of complexity in real-world signals [

30,

40]. (ii)

Loss of amplitude information. A notable limitation of PE is its inability to incorporate amplitude information from the time series. While PE effectively captures the ordinal patterns, it disregards the actual magnitudes of the data points. This omission can result in the loss of critical information, particularly in applications such as signal time series analysis, where amplitude variations often carry significant meaning [

41]. Various modifications to the standard PE have been proposed to incorporate amplitude information to address this issue. For example, improved permutation entropy versions integrate ordinal relations and amplitude data, enabling a more comprehensive analysis [

35,

42]. These enhancements allow for retaining crucial amplitude-related characteristics while preserving the ability to capture the underlying order dynamics [

43,

44]. (iii)

Handling equal values. The presence of equal values in a time series can significantly distort the ordinal patterns upon which PE depends. This distortion may result in inaccuracies in entropy calculations. To moderate the issues caused by equal values, several strategies have been proposed [

45,

46]. (iv)

Heuristic methods in parameter selection. The effectiveness of PE is highly dependent on the careful selection of key parameters, such as the permutation dimension and embedding delay. These parameters play a critical role in optimizing the performance of PE. However, their selection often relies on heuristic methods—practical, trial-and-error approaches that prioritize feasible solutions over theoretically optimal ones. While these methods can be effective in practice, they may lack consistency and precision, underscoring the need for more systematic and data-driven parameter-tuning strategies [

30,

33,

34]. (iv)

Inability to differentiate between distinct patterns within the same motif. Some waveforms, such as electroencephalograms (EEG) [

47], can be represented by a series of ordinal patterns known as motifs, which are derived from the ranking of values in subsequence time series. Permutation Entropy (PE) is designed to capture the relative occurrence of these motifs; however, it struggles to differentiate between distinct patterns within a given motif. This limitation can be addressed through the use of Weighted-Permutation Entropy (WPE), a modified version of PE proposed by Fadlallah et al. [

48]. (v)

Sensitivity to certain processes. Recent studies have indicated that traditional PE may struggle to capture slow-changing signals' dynamics accurately. This limitation is particularly significant when analyzing data from systems that evolve gradually over time, as it can lead to an underestimation of their complexity [

46,

49,

50,

51]. (vi)

Complexity in interpretation. PE is a powerful tool for measuring complexity, but its interpretation can be challenging, particularly in diverse applications such as EEG analysis or financial time series. The complexity of these systems often requires a nuanced understanding of the underlying dynamics, and PE values alone may not provide sufficient insight. Therefore, clear and meaningful conclusions cannot be drawn without additional context or complementary analyses [

52].

3. Permutation Entropy in Hydrology: Diverse Applications and Insights

Permutation entropy (PE) has significantly expanded its application across various fields of hydrology, primarily due to its effectiveness in analyzing the complexity and dynamics of hydrological time series data. Since 2002, the number of research papers utilizing PE in hydrology has increased exponentially. This remarkable growth can be attributed to several key factors: advancements in the standard methodology of PE, the development of models that effectively incorporate this metric, and significant progress in computational techniques, including neural networks and artificial intelligence (AI). Selecting a single effective approach to review the applications of PE in hydrology was challenging. This process was carried out in the following steps. Categorization: We categorized the uses of PE across various subfields, examining its role in runoff prediction, streamflow analysis, water level forecasting, assessment of hydrological changes, and the impact of infrastructure on hydrology. Inclusion criteria: We included papers primarily or partially focused on PE.

Runoff predictions. He et al. [

53] proposed a non-stationary monthly runoff prediction model for optimizing agricultural water management. This model is particularly useful for large irrigation areas along river basins, addressing the spatial and temporal variations in runoff. By integrating multi-scale permutation entropy (MPE), the model improves prediction accuracy, allowing stakeholders to manage water resources effectively in response to changing runoff patterns. A single model cannot fully address the challenges posed by the non-stationarity of runoff. In the hybrid model developed by Wang et al. [

54], the complexity of each subcomponent is assessed using PE. This approach improves the model's efficiency and effectiveness in managing the complexities of runoff data. Building on this foundation, the authors proposed a multi-scale two-phase processing hybrid model for runoff prediction. This innovative approach integrates various processing techniques to enhance prediction accuracy. By decomposing runoff data into multiple scales, the model facilitates a more detailed analysis and improves forecasting capabilities [

55]. The impact of climate change on streamflow complexity is a critical issue for hydrological modeling, runoff predictions, and water resource management. Based on daily streamflow records and calculated permutation entropy (PE), Song et al. [

56] analyzed annual streamflow complexity from 1960 to 2014. Their findings indicate a substantial increase in streamflow complexity since 1972, which can be attributed to climate change, with a huge impact on runoff predictions.

Streamflow analysis. The analysis of streamflow time series on different time scales using PE has been widely recognized as an efficient method since its introduction. From the beginning, permutation entropy was mainly applied to distinguish between chaotic and stochastic behaviors in hydrological systems. Over time, as the methodology advanced, PE became instrumental in understanding the complexity of streamflow dynamics. This progress has been particularly significant in exploring the impacts of climate change and human activities on hydrological phenomena. The pioneering work in applying PE to analyze climate change impact in hydrology is a paper by Hao et al. [

22]. The authors evaluated: (i) climate complexity (higher PE indicates greater unpredictability in climate patterns); (ii) regional variations (variations of PE across regions suggest how environmental factors affect climate complexity); and (iii) temporal trends (noted temporal variations of PE point out changes in climate complexity) in Yunnan Province for the period 1971-2000. The loss of complexity in river streamflow is particularly characteristic of mountain rivers. Analysis of monthly streamflows of two mountain rivers in Bosnia and Herzegovina showed that this loss, followed by a decrease in PE, occurred in 1946–1965 compared to 1926–1990. This complexity loss may be attributed to (i) human interventions after the Second World War on these two rivers because of their use for water consumption and (ii) the impact of climate change [

57]. The paper [

58] studied the influence of anthropically induced effects on streamflow dynamics. Suriano et al. [

59] explored the impact of building the Sobradinho Dam on the daily streamflow of the São Francisco River (Brazil) using the PE method. They analyzed daily streamflow time series recorded during the 1929–2010 period, encompassing the 1973–1979 period when the dam was built. It was found that the original and depersonalized streamflow time series had different complexities and entropy patterns before the building of the dam.

Minimizing the cost monitoring of daily streamflow data is an important issue in hydrology [

60]. To address this issue the authors applied joint PE to data recorded during the period 1989–2016 at twelve gauging stations on the Brazos River, Texas, USA. They found that the best cost efficiency is achieved by performing weekly measurements, in comparison with daily ones which exhibit information redundancy.

Hydrological changes assessment. PE is applied to assess alterations in hydrological patterns due to urbanization or changes in land use. Studies have shown that urban watersheds exhibit decreased complexity and increased entropy, indicating significant hydrological changes over time [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61].

Water level forecasting. We wrap up our look at how PE is used in hydrology by pointing out that new models are superior because they greatly overperform traditional forecasting methods predicting water level changes like the combined GRU–TCN–Transformer AI-based model [

62].

4. Conclusions

In this paper we reviewed the use of permutation entropy in hydrology. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) In various scientific fields, including hydrology, ambiguity exists regarding which aspects can be represented in complex physical systems and which properties serve as discriminatory. Therefore, we have highlighted the distinction between the inability to fully model complex systems and the prevailing view that their complexities can be modeled. We have illustrated this point by modeling a complex system if the model shows none of the most discriminating properties of complexity using a simple mathematical model.

(2) Hydrologists typically analyze complexity in complex systems by applying complexity measures to measured time series—a natural source of information—instead of using heuristic hydrological models. PE is perhaps the most widely used complexity measure in hydrology.

(3) Permutation entropy (PE) is a non-parametric information measure that quantifies the degree of disorder or complexity within a time series by examining the order relations among its values. We briefly discuss its advantages, which include intuitive background, computational efficiency, robustness to noise, minimal parameter requirements, and discrimination of dynamics. However, PE also has several drawbacks: sensitivity to noise, loss of amplitude information, difficulties in handling equal values, reliance on heuristic methods for parameter selection, inability to differentiate between distinct patterns, sensitivity to certain processes, and complexity in interpretation.

4) We reviewed the diverse applications of permutation entropy in hydrology, categorizing its uses across various subfields. Specifically, we examined PE's role in runoff prediction, streamflow analysis, water level forecasting, assessment of hydrological changes, and evaluating the impact of infrastructure on hydrology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.T.M.; Project administration, D.T.M.; Funding acquisition, D.T.M.; Data curation, D.T.M.; Formal analysis, D.T.M.; Methodology, D.T.M.; Validation, D.T.M..; Visualization, D.T.M.; Writing-original draft, D.T.M.; Writing-review and editing, D.T.M.

Funding

This research had no funding.

Acknowledgments

I thank Mi. Anja Mihailović for useful comments and assistance in the computing part of the work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Anderson, P.W. More Is Different: Broken Symmetry and the Nature of the Hierarchical Structure of Science. Science 1972, 177, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianconi, G.; et al. Complex systems in the spotlight: next steps after the 2021 Nobel Prize in Physics. J. Phys. Complex 2023, 4, 010201. [Google Scholar]

- Mihailović, D.; Kapor, D.; Crvenković, S.; Mihailović, A. Physics of Complex Systems: Discovery in the Age of Gödel. CRC Press 2023, 200. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, R. Life Itself: A Comprehensive Inquiry into the Nature, Origin, and Fabrication of Life; Columbia Univ. Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, M. Complexity and the emergence of physical properties. Entropy 2014, 16, 4489–4496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshinov, V.; Fuchs, C. Preface. In Causality, Emergence, Self-Organization; Arshinov, V., Fuchs, C., Eds.; NIAPriroda: Moscow, Russia, 2003; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, C.R. What Isn’t Complexity? arXiv 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Couzin, I.D.; Krause, J.; Franks, N.R.; Levin, S.A. Effective Leadership and Decision-Making in Animal Groups on the Move. Nature 2005, 433, 513–516. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, K. Measuring Complexity Using Information. Qeios 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailović, D.T.; Singh, V.P. Information in Complex Physical Systems: Kolmogorov Complexity Plane of Interacting Amplitudes. Phys. Complex Syst. 2024, 5, 146–153. [Google Scholar]

- Lempel, A.; Ziv, J. On the Complexity of Finite Sequences. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 1976, 22, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandt, C.; Pompe, B. Permutation Entropy: A Natural Complexity Measure for Time Series. Physical Review Letters 2002, 88, 174102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanin, M.; Zunino, L.; Rosso, O.A.; Papo, D. Permutation Entropy and Its Main Biomedical and Econophysics Applications: A Review. Entropy 2012, 14, 1553–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, D.S.; Bahmer, A. Increase in Mutual Information During Interaction with the Environment Contributes to Perception. Entropy 2019, 21, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Wei, J.; Zhang, Y. Fault Diagnosis for Rail Vehicle Axle-Box Bearings Based on Energy Feature Reconstruction and Composite Multiscale Permutation Entropy. Entropy 2019, 21, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegoyen, I.; López-Sanz, D.; Martínez, J.H.; Maestú, F.; Buldú, J.M. Permutation Entropy and Statistical Complexity in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease: An Analysis Based on Frequency Bands. Entropy 2020, 22, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Liu, F.; Gao, J.; Cheng, C.; Song, C. Characterizing Complexity Changes in Chinese Stock Markets by Permutation Entropy. Entropy 2017, 19, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zunino, L.; Zanin, M.; Tabak, B.M.; Perez, D.G.; Rosso, O.A. Forbidden patterns, permutation entropy and stock market inefficiency. Phys. A 2009, 388, 2854–2864. [Google Scholar]

- Raath, J. L.; Olivier, C. P.; Engelbrecht, N. E. A permutation entropy analysis of Voyager interplanetary magnetic field observations. J. Geophys. Res. 2022, 127(6), e2021JA030200. [Google Scholar]

- Renin, S. Unveiling hidden structures: Applications of permutation entropy in data analysis. Adv. Robot. Autom. 2023, 12, 268. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, B.; Myers, A.; Boydston, T.; Ellwein, E.; Mackenzie, C.; Alvarez, I.; Lentz, E. Permutation entropy for signal analysis. Discrete Math. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2024, 26(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, C.Y.; Wu, S.H.; Li, S.C. Measurement of Climate Complexity Using Permutation Entropy. Geogr. Res. 2007, 26, 46–52. [Google Scholar]

- Tirabassi, G.; Duque-Gijon, M.; Tiana-Alsina, J.; Masoller, C. Permutation entropy-based characterization of speckle patterns generated by semiconductor laser light. APL Photonics 2023, 8, 126112. [Google Scholar]

- Machiwal, D.; Jha, M.K. Time Series Analysis of Hydrologic Data for Water Resources Planning and Management: A Review. J. Hydrol. Hydromech. 2006, 54, 237–257. [Google Scholar]

- Neppel, F.; Renard, B.; Lang, M.; Aryal, P.-A.; Coeur, D.; Gaume, E.; Jacob, N.; Payrastre, O.; Pobanz, K.; Vinet, F. Flood Frequency Analysis Using Historical Data: Accounting for Random and Systematic Errors. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2010, 55, 192–208. [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire, G.R.; Jadidoleslam, N.; Krajewski, W.F.; Tsonis, A.A. Insights on Streamflow Predictability Across Scales Using Horizontal Visibility Graph Based Networks. Front. in Water 2020, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. , Jiang, L., Luo, Y., and Liu, J.: A global streamflow indices time series dataset for large-sample hydrological analyses on streamflow regime (until 2022). Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 2023, 15, 4463–4479. [Google Scholar]

- Dastour, H.; Hassan, Q.K. A Machine-Learning Framework for Modeling and Predicting Monthly Streamflow Time Series. Hydrology 2023, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R. Permutation Entropies and Chaos; Department of Physics, UC Davis: Davis, CA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Riedl, M.; Müller, A.; Wessel, N. Practical considerations of permutation entropy: A tutorial review. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2013, 222, 249–262. [Google Scholar]

- Zanin, M.; Rodríguez-González, A.; Menasalvas Ruiz, E.; Papo, D. Assessing Time Series Reversibility through Permutation Patterns. Entropy 2018, 20, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boaretto, B.R.R.; Budzinski, R.C.; Rossi, K.L. Discriminating Chaotic and Stochastic Time Series Using Permutation Entropy and Artificial Neural Networks. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 15789. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, A.; Khasawneh, F. A. On the automatic parameter selection for permutation entropy. Chaos 2020, 30, 033130. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, A.D.; Chumley, M.M.; Khasawneh, F.A. Delay Parameter Selection in Permutation Entropy Using Topological Data Analysis. La Matematica 2024, 3, 1103–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Ma, X.; Fu, J.; Li, Y. Ensemble Improved Permutation Entropy: A New Approach for Time Series Analysis. Entropy 2023, 25, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amigó, J.M.; Dale, R.; Tempesta, P. A Generalized Permutation Entropy for Random Processes. arXiv 2003.13728 [physics.data-an].

- Keller, K.; Mangold, T.; Stolz, I.; Werner, J. Permutation Entropy: New Ideas and Challenges. Entropy 2017, 19, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutjahr, T.; Keller, K. Equality of Kolmogorov-Sinai and permutation entropy for one-dimensional maps consisting of countably many monotone parts. Discrete Contin. Dyn. Syst. 2019, 39(7), 4207–4224. [Google Scholar]

- Zunino, L.; Kulp, C. W. Detecting nonlinearity in short and noisy time series using the permutation entropy. Phys. Lett. A 2017, 381, 3627–3635. [Google Scholar]

- Porta, A.; Bari, V.; Marchi, A.; De Maria, B.; Castiglioni, P.; di Rienzo, M.; Guzzetti, S.; Cividjian, A.; Quintin, L. Limits of Permutation-Based Entropies in Assessing Complexity of Short Heart Period Variability. Physiol Meas 2015, 36, 755–765. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, B.; Myers, A.; Boydston, T.; Ellwein, E.; Mackenzie, C.; Alvarez, I.; Lentz, E. Permutation Entropy for Signal Analysis. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2312.00964v2 [cs.IT]. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Liang, H.; Yu, J. Improved Permutation Entropy for Measuring Complexity of Time Series under Noisy Condition. Complexity 2019, 2019, 1403829. [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta-Frau, D.; Molina-Picó, A.; Vargas, B.; González, P. Permutation Entropy: Enhancing Discriminating Power by Using Relative Frequencies Vector of Ordinal Patterns Instead of Their Shannon Entropy. Entropy 2019, 21, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta-Frau, D. Permutation entropy: Influence of amplitude information on time series classification performance. Math Biosci Eng 2019, 16(6), 6842–6857. [Google Scholar]

- Zunino, L.; Olivares, F.; Scholkmann, F.; Rosso, O. A. Permutation entropy-based time series analysis: Equalities in the input signal can lead to false conclusions. Physics Letters A 2017, 381(22), 1883–1892. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X.; Shang, H. L.; Pitt, D. Permutation entropy and its variants for measuring temporal dependence. Aust. N. Z. J. Stat. 2022, 64(4), 413–421. [Google Scholar]

- Vuong, P. L.; Malik, A. S.; Bornot, J. Weighted-permutation entropy as a complexity measure for electroencephalographic time series of different physiological states. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Sciences (IECBES); Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; 2014; pp. 979–984. [Google Scholar]

- Fadlallah, B.; Chen, B.; Keil, A.; Príncipe, J. Weighted-Permutation Entropy: A Complexity Measure for Time Series Incorporating Amplitude Information. Phys. Rev. E 2013, 87(2), 022911. [Google Scholar]

- Goekoop, R.; de Kleijn, R. Permutation Entropy as a Universal Disorder Criterion: How Disorders at Different Scale Levels Are Manifestations of the Same Underlying Principle. Entropy 2021, 23, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpua, E.; Good, S.; Ala-Lahti, M.; Osmane, A.; Koikkalainen, V. Permutation Entropy and Complexity Analysis of Large-Scale Solar Wind Structures and Streams. EGU General Assembly 2023, 2023, 2352. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, B.; Myers, A.; Boydston, T.; Ellwein, E.; Mackenzie, C.; Alvarez, I.; Lentz, E. Permutation Entropy for Signal Analysis. arXiv 2023, 2312.00964.

- Berger, S.; Schneider, G.; Kochs, E.F.; Jordan, D. Permutation Entropy: Too Complex a Measure for EEG Time Series? Entropy 2017, 19, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Chen, F.; Long, A.; Qian, Y.; Tang, H. Improving the Precision of Monthly Runoff Prediction Using the Combined Non-stationary Methods in an Oasis Irrigation area. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 279, 108161. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zhao, X.; Guo, Q. A Novel Hybrid Model by Integrating TCN with TVFEMD and Permutation Entropy for Monthly Non-Stationary Runoff Prediction. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 31699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wang, H.; Guo, Q.; et al. Runoff prediction using a multi-scale two-phase processing hybrid model. Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Cheng, C.; Ye, S. The coupling impact of climate change on streamflow complexity in the headwater area of the northeastern Tibetan Plateau across multiple timescales. Journal of Hydrology 2020, 588, 124996. [Google Scholar]

- Mihailović, D.T.; Nikolić-Đorić, E.; Drešković, N.; Mimić, G. Complexity Analysis of the Turbulent Environmental Fluid Flow Time Series. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2014, 395, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stosic, T.; Telesca, L.; Ferreira, D.V.D.; Stosic, B. Investigating anthropically induced effects in streamflow dynamics by using permutation entropy and statistical complexity analysis: A case study. J. Hydrol. 2016, 540, 1136–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriano, M.; Caram, L.F.; Rosso, O.A. Daily Streamflow of Argentine Rivers Analysis Using Information Theory Quantifiers. Entropy 2024, 26, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stosic, T.; Stosic, B.; Singh, V.P. Optimizing Streamflow Monitoring Networks Using Joint Permutation Entropy. Journal of Hydrology 2017, 554, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Huang, B.; Qin, T.; Nie, H.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Shen, Z. Assessment of Hydrological Changes and Their Influence on the Aquatic Ecology over the last 58 Years in Ganjiang Basin, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; He, T.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y. Forecasting Gate-Front Water Levels Using a Coupled GRU–TCN–Transformer Model and Permutation Entropy Algorithm. Water 2024, 16, 3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).