Submitted:

20 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Study Setting

2.4. Study Population and Sampling Method

2.5. Data Treatment and Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

2.7. Methodological Design

2.7.1. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing (E-Test)

2.7.2. DNA Extraction

2.7.3. Tet x gene detection using PCR

3. Results

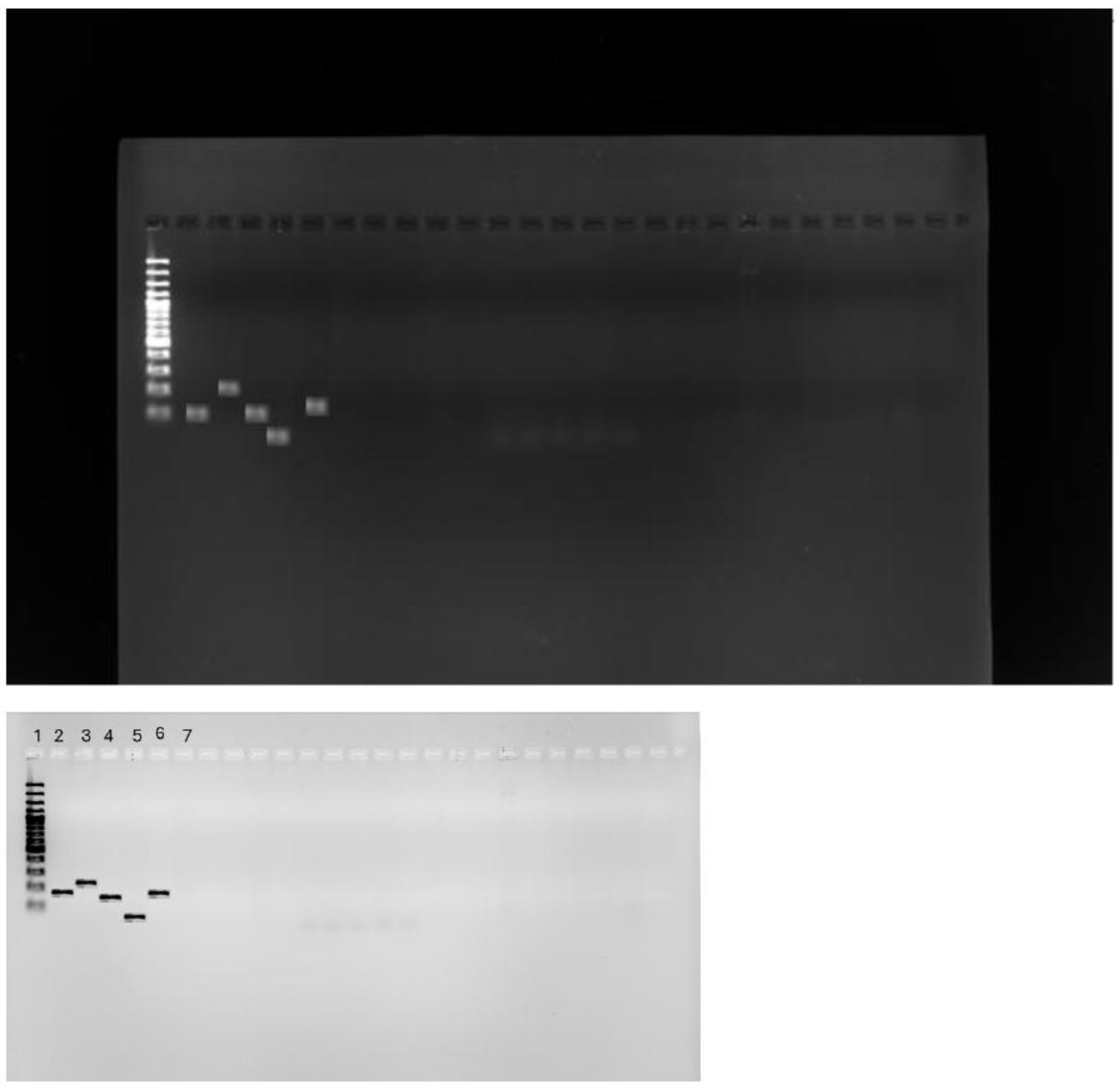

3.1. Carbapenem Resistant Enterobacterales Species

| Species | VIM | KPC | NDM | OXA-48 | Not detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citrobacter spp. | 0 | 0 | 50% | 25% | 25% |

| Enterobacter spp. | 0 | 0 | 45.6% | 27.8% | 27.% |

| Escherichia coli | 0 | 0 | 60% | 40% | 0 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 0 | 0 | 60.2% | 29.1% | 11.3% |

| Specimen | Type | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Abscess | Blood culture | Pus swab | Sputum | Urine | Tissue | Other |

| Citrobacter spp. | 0 | 0 | 8.3% | 14.3% | 5.9% | 0 | 0 |

| Enterobacter spp. | 0 | 13% | 33.3% | 33.3% | 41.2% | 0 | 80% |

| Escherichia coli | 0 | 4.35% | 50% | 14.3% | 5.9% | 0 | 0 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 100% | 86.9 % | 41.7 | 71.4% | 41.2% | 100% | 20% |

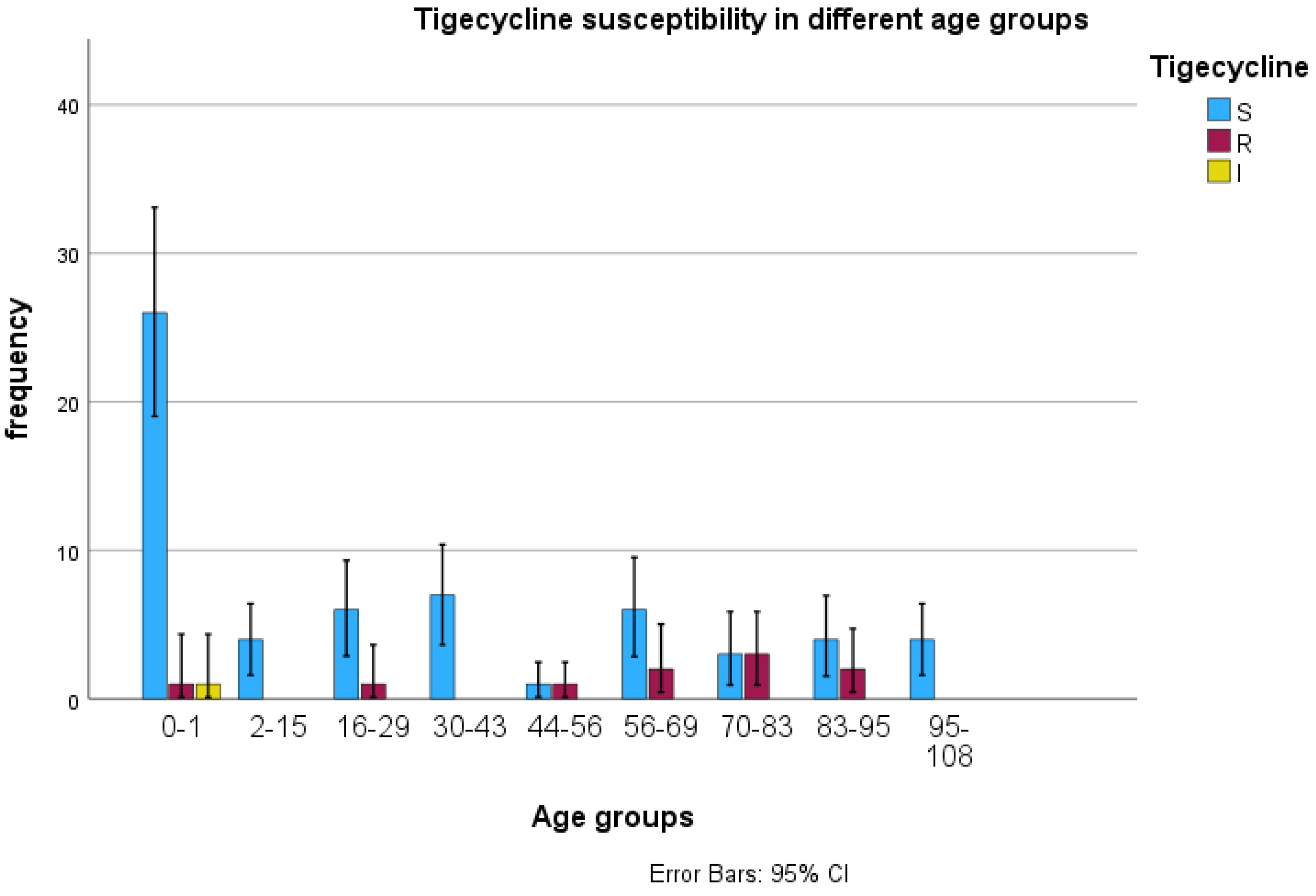

3.2. Tigecycline Susceptibility Using E-Test

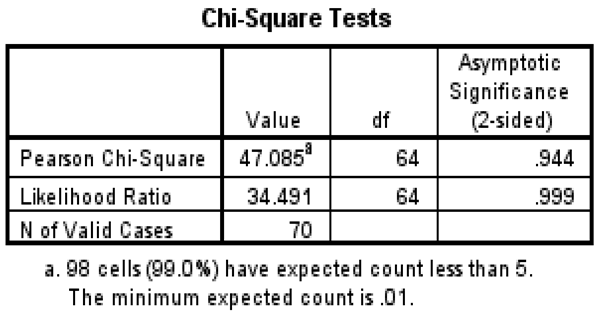

3.3. Detection of tet(X) Genes Using PCR

3.4. Risk Factors Associated with Tigecycline Resistance

4. Discussion

4.1. To Determine the CRE Species

4.2. Tigecycline Susceptibility Using E-Test

4.3. PCR for Tet (X) Genes

4.4. Risk Factors Associated with Tigecycline

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Qadheeb, N.S., Althawadi, S., Alkhalaf, A., Hosaini, S. and Alrajhi, A.A., 2010. Evolution of tigecycline resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae in a single patient. Annals of Saudi Medicine, 30(5), pp.404-407.

- Alraddadi, B.M., Heaphy, E.L., Aljishi, Y., Ahmed, W., Eljaaly, K., Al-Turkistani, H.H., Alshukairi, A.N., Qutub, M.O., Alodini, K., Alosaimi, R. and Hassan, W., 2022. Molecular epidemiology and outcome of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales in Saudi Arabia. BMC Infectious Diseases, 22(1), p.542. [CrossRef]

- Araj, G.F. and Ibrahim, G.Y., 2008. Tigecycline in vitro activity against commonly encountered multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens in a Middle Eastern country. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease, 62(4), pp.411-415. [CrossRef]

- Aslam, B., Rasool, M., Muzammil, S., Siddique, A.B., Nawaz, Z., Shafique, M., Zahoor, M.A., Binyamin, R., Waseem, M., Khurshid, M. and Arshad, M.I., 2020. Carbapenem resistance: Mechanisms and drivers of global menace. Pathog Bact, pp.1-11.

- Babaei, S. and Haeili, M., 2021. Evaluating the performance characteristics of different antimicrobial susceptibility testing methodologies for testing susceptibility of gram-negative bacteria to tigecycline. BMC Infectious Diseases, 21, pp.1-8Adesanya, O.A. and Igwe, H.A., 2020. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) and gram-negative bacterial infections in south-west Nigeria: a retrospective epidemiological surveillance study. AIMS Public Health, 7(4), p.804.

- Bajaj, A., Mishra, B., Loomba, P.S., Thakur, A., Sharma, A., Rathod, P.G., Das, M. and Bhasin, A., 2020. Tigecycline Susceptibility of Carbapenem Resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter spp. isolates from Respiratory Tract: A Tertiary Care Centre Study. Journal of Krishna Institute of Medical Sciences (JKIMSU), 9(1).

- Bankan, N., Koka, F., Vijayaraghavan, R., Basireddy, S.R. and Jayaraman, S., 2021. Overexpression of the adeB efflux pump gene in tigecycline-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates and its inhibition by (+) usnic acid as an adjuvant. Antibiotics, 10(9), p.1037. [CrossRef]

- Baron, S.A., Cassir, N., Hamel, M., Hadjadj, L., Saidani, N., Dubourg, G. and Rolain, J.M., 2021. Risk factors for acquisition of colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and expansion of a colistin-resistant ST307 epidemic clone in hospitals in Marseille, France, 2014 to 2017. Eurosurveillance, 26(21), p.2000022. [CrossRef]

- Bender, J.K., Klare, I., Fleige, C. and Werner, G., 2020. A nosocomial cluster of tigecycline-and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium Isolates and the Impact of rpsJ and tet (M) mutations on tigecycline resistance. Microbial Drug Resistance, 26(6), pp.576-582. [CrossRef]

- Bilal, H., Khan, M.N., Rehman, T., Hameed, M.F. and Yang, X., 2021. Antibiotic resistance in Pakistan: a systematic review of the past decade. BMC Infectious Diseases, 21, pp.1-19. [CrossRef]

- Brink, A.J., Coetzee, J., Corcoran, C., Clay, C.G., Hari-Makkan, D., Jacobson, R.K., Richards, G.A., Feldman, C., Nutt, L., van Greune, J. and Deetlefs, J.D., 2013. Emergence of OXA-48 and OXA-181 carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae in South Africa and evidence of in vivo selection of colistin resistance as a consequence of selective decontamination of the gastrointestinal tract. Journal of clinical microbiology, 51(1), pp.369-372. [CrossRef]

- Bush, K. and Bradford, P.A., 2020. Epidemiology of β-lactamase-producing pathogens. Clinical microbiology reviews, 33(2), pp.10-1128. [CrossRef]

- Campany-Herrero, D., Larrosa-Garcia, M., Lalueza-Broto, P., Rivera-Sánchez, L., Espinosa-Pereiro, J., Mestre-Torres, J. and Pigrau-Serrallach, C., 2020. Tigecycline-associated hypofibrinogenemia in a real-world setting. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 42, pp.1184-1189. [CrossRef]

- Cassir, N., Rolain, J.M. and Brouqui, P., 2014. A new strategy to fight antimicrobial resistance: the revival of old antibiotics. Frontiers in microbiology, 5, p.109581.

- Cattoir, V., Isnard, C., Cosquer, T., Odhiambo, A., Bucquet, F., Guérin, F. and Giard, J.C., 2015. Genomic analysis of reduced susceptibility to tigecycline in Enterococcus faecium. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 59(1), pp.239-244. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.L., Jiang, Y., Li, M.M., Sun, Y., Cao, J.M., Zhou, C., Zhang, X.X., Qu, Y. and Zhou, T.L., 2021. Acquisition of Tigecycline Resistance by carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae confers collateral hypersensitivity to aminoglycosides. Frontiers in Microbiology, 12, p.674502. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q., Cheung, Y., Liu, C., Chan, E.W.C., Wong, K.Y., Zhang, R. and Chen, S., 2022. Functional and phylogenetic analysis of TetX variants to design a new classification system. Communications Biology, 5(1), p.522. [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.Y., He, Q., Jia, Q.L., Li, C., Chen, C., Wu, X.T., Zhang, X.J., Lin, Z.Y., Zheng, Z.J., Liao, X.P. and Kreiswirth, B.N., 2021. The evolutionary trajectory of the Tet (X) family: critical residue changes towards high-level tigecycline resistance. Msystems, 6(3), pp.10-1128. [CrossRef]

- Curcio, D., Fernández, F. and Duret, F., 2007. Tigecycline use in critically ill older patients: case reports and critical analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55(2), pp.312-313. [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.X., Chen, C., Cui, C.Y., Li, X.P., Zhang, Y., Liao, X.P., Sun, J. and Liu, Y.H., 2020. Emerging high-level tigecycline resistance: novel tetracycline destructases spread via the mobile Tet (X)—Bioessays, 42(8), p.2000014.

- Fu, Y., Chen, Y., Liu, D., Yang, D., Liu, Z., Wang, Y., Wang, J., Wang, X., Xu, X., Li, X. and He, J., 2021. Abundance of tigecycline resistance genes and association with antibiotic residues in Chinese livestock farms. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 409, p.124921. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y., Liu, D., Song, H., Liu, Z., Jiang, H. and Wang, Y., 2020. Development of a multiplex real-time PCR assay to rapidly detect tigecycline resistance gene tet (X) variants from bacterial, fecal, and environmental samples. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 64(4), pp.10-1128.

- Gajic, I., Ranin, L., Kekic, D., Opavski, N., Smitran, A., Mijac, V., Jovanovic, S., Hadnadjev, M., Travar, M. and Mijovic, G., 2020. Tigecycline susceptibility of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii from intensive care units in the western Balkans. Acta Microbiologica et Immunologica Hungarica, 67(3), pp.176-181. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., Chen, M., Cai, M., Liu, K., Wang, Y., Zhou, C., Chang, Z., Zou, Q., Xiao, S., Cao, Y. and Wang, W., 2022. An analysis of risk factors for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infection. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance, 30, pp.191-198. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S., Sadowsky, M.J., Roberts, M.C., Gralnick, J.A. and LaPara, T.M., 2009. Sphingobacterium sp. strain PM2-P1-29 harbors a functional tet (X) gene encoding for the degradation of tetracycline. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 106(4), pp.1336-1342.

- Gomis, P.F., Jean-Pierre, H., Rousseau-Didelot, M.N., Compan, B., Michon, A.L. and Godreuil, S., 2013. Tigécycline: CMI 50/90 vis-à-vis de 1766 bacilles à Gram-négatif (entérobactéries résistantes aux céphalosporines de troisième génération), Acinetobacter baumannii et Bacteroides du groupe fragilis, CHU–Montpellier, 2008–2011. Pathologie Biologie, 61(6), pp.282-285.

- Han, X., Shi, Q., Mao, Y., Quan, J., Zhang, P., Lan, P., Jiang, Y., Zhao, D., Wu, X., Hua, X. and Yu, Y., 2021. The emergence of ceftazidime/avibactam and tigecycline resistance in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae due to in-host microevolution. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 11, p.757470. [CrossRef]

- Heidary, M., Sholeh, M., Asadi, A., Khah, S.M., Kheirabadi, F., Saeidi, P., Darbandi, A., Taheri, B. and Ghanavati, R., 2024. Prevalence of tigecycline resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease, 108(1), p.116088. [CrossRef]

- Heidary, M., Sholeh, M., Asadi, A., Khah, S.M., Kheirabadi, F., Saeidi, P., Darbandi, A., Taheri, B. and Ghanavati, R., 2023. Prevalence of Tigecycline Resistance in Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease, p.116088. [CrossRef]

- Hovan, M.R., Narayanan, N., Cedarbaum, V., Bhowmick, T. and Kirn, T.J., 2021. Comparing mortality in patients with carbapenemase-producing carbapenem resistant Enterobacterales and non-carbapenemase-producing carbapenem resistant Enterobacterales bacteremia. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease, 101(4), p.115505. [CrossRef]

- Hua, X., He, J., Wang, J., Zhang, L., Zhang, L., Xu, Q., Shi, K., Leptihn, S., Shi, Y., Fu, X. and Zhu, P., 2021. Novel tigecycline resistance mechanisms in Acinetobacter baumannii are mediated by mutations in adeS, rpoB, and rrf. Emerging Microbes & Infections, 10(1), pp.1404-1417.

- Jenner, L., Starosta, A.L., Terry, D.S., Mikolajka, A., Filonava, L., Yusupov, M., Blanchard, S.C., Wilson, D.N. and Yusupova, G., 2013. Structural basis for potent inhibitory activity of the antibiotic tigecycline during protein synthesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(10), pp.3812-3816. [CrossRef]

- Ji, K., Xu, Y., Sun, J., Huang, M., Jia, X., Jiang, C. and Feng, Y., 2020. Harnessing efficient multiplex PCR methods to detect the expanding Tet (X) family of tigecycline resistance genes. Virulence, 11(1), pp.49-56. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y., Jia, X. and Xia, Y., 2019. Risk factors with the development of infection with tigecycline-and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacter cloacae. Infection and drug resistance, pp.667-674.

- Jiang, Y., Yang, S., Deng, S., Lu, W., Huang, Q. and Xia, Y., 2022. Epidemiology and resistance mechanisms of tigecycline-and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacter cloacae in Southwest China: a 5-year retrospective study. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance, 28, pp.161-167. [CrossRef]

- Juan, C.H., Huang, Y.W., Lin, Y.T., Yang, T.C. and Wang, F.D., 2016. Risk factors, outcomes, and mechanisms of tigecycline-nonsusceptible Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 60(12), pp.7357-7363.

- Karami-Zarandi, M., Rahdar, H.A., Esmaeili, H. and Ranjbar, R., 2023. Klebsiella pneumoniae: an update on antibiotic resistance mechanisms. Future Microbiology, 18(1), pp.65-81.

- Karlowsky, J.A., Kazmierczak, K.M., Young, K., Motyl, M.R. and Sahm, D.F., 2020. In vitro activity of ceftolozane/tazobactam against phenotypically defined extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-positive isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from hospitalized patients (SMART 2016). Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease, 96(4), p.114925.

- Kaye, K.S., Naas, T., Pogue, J.M. and Rossolini, G.M., 2023. Cefiderocol, a siderophore cephalosporin, as a treatment option for infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales. Infectious Diseases and Therapy, 12(3), pp.777-806. [CrossRef]

- Kechagias, K.S., Chorepsima, S., Triarides, N.A. and Falagas, M.E., 2020. Tigecycline for the treatment of patients with Clostridium difficile infection: an update of the clinical evidence. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, 39, pp.1053-1058.

- Kessel, J., Bender, J., Werner, G., Griskaitis, M., Herrmann, E., Lehn, A., Serve, H., Zacharowski, K., Zeuzem, S., Vehreschild, M.J. and Wichelhaus, T.A., 2021. Risk factors and outcomes associated with the carriage of tigecycline vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium. Journal of Infection, 82(2), pp.227-234.

- Khabbaz, R.F., Moseley, R.R., Steiner, R.J., Levitt, A.M. and Bell, B.P., 2014. Challenges of infectious diseases in the USA. The Lancet, 384(9937), pp.53-63.

- Korczak, L., Majewski, P., Iwaniuk, D., Sacha, P., Matulewicz, M., Wieczorek, P., Majewska, P., Wieczorek, A., Radziwon, P. and Tryniszewska, E., 2024. Molecular mechanisms of tigecycline-resistance among Enterobacterales. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 14, p.1289396. [CrossRef]

- Korczak, L., Majewski, P., Iwaniuk, D., Sacha, P., Matulewicz, M., Wieczorek, P., Majewska, P., Wieczorek, A., Radziwon, P. and Tryniszewska, E., 2024. Molecular mechanisms of tigecycline-resistance among Enterobacterales. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 14, p.1289396.

- Korczak, L., Majewski, P., Iwaniuk, D., Sacha, P., Matulewicz, M., Wieczorek, P., Majewska, P., Wieczorek, A., Radziwon, P. and Tryniszewska, E., 2024. Molecular mechanisms of tigecycline-resistance among Enterobacterales. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 14, p.1289396.

- Kotb, S., Lyman, M., Ismail, G., Abd El Fattah, M., Girgis, S.A., Etman, A., Hafez, S., El-Kholy, J., Zaki, M.E.S., Rashed, H.A.G. and Khalil, G.M., 2020. Epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Egyptian intensive care units using National Healthcare–associated Infections Surveillance Data, 2011–2017. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control, 9, pp.1-9.

- Lamut, A., Peterlin Mašič, L., Kikelj, D. and Tomašič, T., 2019. Efflux pump inhibitors of clinically relevant multidrug resistant bacteria. Medicinal Research Reviews, 39(6), pp.2460-2504. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M., Abbey, T., Biagi, M. and Wenzler, E., 2021. Activity of aztreonam in combination with ceftazidime–avibactam against serine-and metallo-β-lactamase–producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease, 99(1), p.115227.

- Li, L., Wang, L., Yang, S., Zhang, Y., Gao, Y., Ji, Q., Fu, L., Wei, Q., Sun, F. and Qu, S., 2024. Tigecycline-resistance mechanisms and biological characteristics of drug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium strains in vitro. Veterinary Microbiology, 288, p.109927.

- Li, X., Quan, J., Yang, Y., Ji, J., Liu, L., Fu, Y., Hua, X., Chen, Y., Pi, B., Jiang, Y. and Yu, Y., 2016. Abrp, a new gene, confers reduced susceptibility to tetracycline, glycylcine, chloramphenicol, and fosfomycin classes in Acinetobacter baumannii. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, 35(8), pp.1371-1375.

- Li, Y.Y., Wang, J., Wang, R. and Cai, Y., 2020. Double-carbapenem therapy in the treatment of multidrug resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infectious Diseases, 20, pp.1-13. [CrossRef]

- Lowe, M., Shuping, L. and Perovic, O., 2022. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales in patients with bacteremia at tertiary academic hospitals in South Africa, 2019-2020: An update. South African Medical Journal, 112(8), pp.545-552.

- Luchao Lv, L., Wan, M., Wang, C., Gao, X., Yang, Q., Partridge, S.R., Wang, Y., Zong, Z., Shen, J., Jia, P. and Song, Q., 2020. The emergence of a Plasmid-Encoded Resistance-Nodulation-Division Efflux Pump Conferring Resistance to Multiple Drugs, Including Tigecycline, in Klebsiella pneumoniae.

- Marot, J.C., Jonckheere, S., Munyentwali, H., Belkhir, L., Vandercam, B. and Yombi, J.C., 2012. Tigecycline-induced acute pancreatitis: about two cases and review of the literature. Acta Clinica Belgica, 67(3), pp.229-232.

- Moore, I.F., Hughes, D.W. and Wright, G.D., 2005. Tigecycline is modified by the flavin-dependent monooxygenase TetX. Biochemistry, 44(35), pp.11829-11835.

- Mzimela, B.W., Nkwanyana, N.M. and Singh, R., 2021. Clinical outcome of neonates with Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections at the King Edward VIII Hospital’s neonatal unit, Durban, South Africa. Southern African Journal of Infectious Diseases, 36(1), p.223.

- Ni WenTao, N.W., Han YuLiang, H.Y., Liu Jie, L.J., Wei ChuanQi, W.C., Zhao Jin, Z.J., Cui JunChang, C.J., Wang Rui, W.R. and Liu YouNing, L.Y., 2016. Tigecycline treatment for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

- Olayiwola, J.O., Ojo, D.A., Balogun, S.A. and Ojo, O.E., 2021. Global Spread of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae: A Challenging Threat to the Treatment of Bacterial Diseases in Clinical Practice. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Applied Science, 6(10), pp.52-60. [CrossRef]

- Onuk, S.E.V.D.A., Coruh, A., Kilic, A.Y.Ş.E.G.Ü.L., EREN, E. and GÜNDOĞAN, K., 2023. The frequency of ESBL producing bacterial infections and related antimicrobial susceptibility in ICU patients: A five-year longitudinal study ESBL producing bacterial infections in ICU. ANNALS OF CLINICAL AND ANALYTICAL MEDICINE.

- Park, D.R., 2005. Antimicrobial treatment of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Respiratory care, 50(7), pp.932-955.

- Park, S.H., Kim, J.S., Kim, H.S., Yu, J.K., Han, S.H., Kang, M.J., Hong, C.K., Lee, S.M. and Oh, Y.H., 2020. Prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Seoul, Korea. Journal of Bacteriology and Virology, 50(2), pp.107-116. [CrossRef]

- Paveenkittiporn, W., Lyman, M., Biedron, C., Chea, N., Bunthi, C., Kolwaite, A. and Janejai, N., 2021. Molecular epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales in Thailand, 2016–2018. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control, 10(1), p.88.

- Perovic, O., Ismail, H., Quan, V., Bamford, C., Nana, T., Chibabhai, V., Bhola, P., Ramjathan, P., Swe Swe-Han, K., Wadula, J. and Whitelaw, A., 2020. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in patients with bacteremia at tertiary hospitals in South Africa, 2015 to 2018. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, 39, pp.1287-1294.

- Ravoor, J., Amirthalingam, S., Mohan, T. and Rangasamy, J., 2020. Antibacterial, anti-biofilm, and angiogenic calcium sulfate-nano MgO composite bone void fillers for inhibiting Staphylococcus aureus infections. Colloid and Interface Science Communications, 39, p.100332. [CrossRef]

- Rempel, S., Stanek, W.K. and Slotboom, D.J., 2019. ECF-type ATP-binding cassette transporters. Annual review of biochemistry, 88, pp.551-576. [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, K., Horwich-Scholefield, S. and Epson, E., 2019. Carbapenem and cephalosporin resistance among Enterobacteriaceae in healthcare-associated infections, California, USA. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 25(7), p.1389.

- Rodrigues, Y.C., Lobato, A.R.F., Quaresma, A.J.P.G., Guerra, L.M.G.D. and Brasiliense, D.M., 2021. The spread of NDM-1 and NDM-7-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae is driven by multiclonal expansion of high-risk clones in healthcare institutions in the state of Pará, Brazilian Amazon Region. Antibiotics, 10(12), p.1527.

- Rodvold, K.A., Gotfried, M.H., Cwik, M., Korth-Bradley, J.M., Dukart, G. and Ellis-Grosse, E.J., 2006. Serum, tissue and body fluid concentrations of tigecycline after a single 100 mg dose. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 58(6), pp.1221-1229.

- Sader, H.S., Mendes, R.E., Streit, J.M., Carvalhaes, C.G. and Castanheira, M., 2022. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Gram-negative bacteria from intensive care unit and non-intensive care unit patients from United States hospitals (2018–2020). Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease, 102(1), p.115557.

- Saeed, N.K., Alkhawaja, S., Azam, N.F.A.E.M., Alaradi, K. and Al-Biltagi, M., 2019. Epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in a Tertiary Care Center in the Kingdom of Bahrain. Journal of laboratory physicians, 11(02), pp.111-117.

- Sah, R., BEGUM, S. and Anbumani, N., 2022. Colistin and Tigecycline susceptibility among carbapenemase producing Enterobacteriaceae at a tertiary care hospital of South India. Microbes and Infectious Diseases, 3(2), pp.387-397.

- Seifert, H., Blondeau, J. and Dowzicky, M.J., 2018. In vitro activity of tigecycline and comparators (2014–2016) among key WHO ‘priority pathogens’ and longitudinal assessment (2004–2016) of antimicrobial resistance: a report from the TEST study. International journal of antimicrobial agents, 52(4), pp.474-484.

- Seifert, H., Blondeau, J., Lucassen, K. and Utt, E.A., 2022. Global update on the in vitro activity of tigecycline and comparators against isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii and rates of resistant phenotypes (2016–2018). Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance, 31, pp.82-89.

- Sekyerea, J.O., Pedersenb, T., Sivertsenb, A., Govindena, U., Essacka, S.Y., Moodleyc, K., Samuelsenb, O. and Sundsfjordb, A., 2016. Molecular epidemiology of carbapenem, colistin, and tigecycline resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Durban, South Africa.

- Sheykhsaran, E., Baghi, H.B., Soroush, M.H. and Ghotaslou, R., 2019. An overview of tetracyclines and related resistance mechanisms. Reviews and Research in Medical Microbiology, 30(1), pp.69-75.

- Shi, S., Xu, M., Zhao, Y., Feng, L., Liu, Q., Yao, Z., Sun, Y., Zhou, T. and Ye, J., 2023. Tigecycline–Rifampicin Restrains Resistance Development in Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. ACS Infectious Diseases, 9(10), pp.1858-1866.

- Soraci, L., Cherubini, A., Paoletti, L., Filippelli, G., Luciani, F., Laganà, P., Gambuzza, M.E., Filicetti, E., Corsonello, A. and Lattanzio, F., 2023. Safety and tolerability of antimicrobial agents in the older patient. Drugs & Aging, 40(6), pp.499-526. [CrossRef]

- Stein, G.E. and Babinchak, T., 2013. Tigecycline: an update. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease, 75(4), pp.331-336.

- Su, W., Wang, W., Li, L., Zhang, M., Xu, H., Fu, C., Pang, X. and Wang, M., 2024. Mechanisms of tigecycline resistance in Gram-negative bacteria: A narrative review. Engineering Microbiology, p.100165.

- Sun, C., Yu, Y. and Hua, X., 2023. Resistance mechanisms of tigecycline in Acinetobacter baumannii. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 13, p.1141490. [CrossRef]

- Swaminathan, S. and Kundu, P., 2020. Tigecycline: Role in the Management of cIAI and cSSTI in the Indian Context. Indian Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(1-2), pp.24-30.

- Tamma, P.D., Goodman, K.E., Harris, A.D., Tekle, T., Roberts, A., Taiwo, A. and Simner, P.J., 2017. Comparing the outcomes of patients with carbapenemase-producing and non-carbapenemase-producing carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae bacteremia. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 64(3), pp.257-264.

- Tootla, H.D., Prentice, E., Moodley, C., Marais, G., Nyakutira, N., Reddy, K., Bamford, C., Niehaus, A., Whitelaw, A. and Brink, A., 2024. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales among hospitalized patients in Cape Town, South Africa: clinical and microbiological epidemiology. JAC-Antimicrobial Resistance, 6(2), p.dlae051. [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.M., Li, L., Monk, I.R., Lee, J.Y.H., Ingle, D.J., Duchene, S., Sherry, N.L., Stinear, T.P., Kwong, J.C., Gorrie, C.L. and Howden, B.P., 2023. Rifaximin prophylaxis causes resistance to the last-resort antibiotic daptomycin. medRxiv, pp.2023-03.

- Varma, M., Reddy, L.R., Vidyasagar, S., Holla, A. and Bhat, N.K., 2018. Risk factors for carbapenem resistant enterobacteriaceae in a teritiary hospital—A case control study. Indian Journal of Medical Specialities, 9(4), pp.178-183. [CrossRef]

- Venter, H., Mowla, R., Ohene-Agyei, T. and Ma, S., 2015. RND-type drug efflux pumps from Gram-negative bacteria: molecular mechanism and inhibition. Frontiers in microbiology, 6, p.135560.

- Viechtbauer, W. and Cheung, M.W.L., 2010. Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta-analysis. Research synthesis methods, 1(2), pp.112-125.

- Vink, J.P., Otter, J.A. and Edgeworth, J.D., 2020. Carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae–once positive always positive?. Current Opinion in Gastroenterology, 36(1), pp.9-16.

- Vogelaers, D., Blot, S., Van den Berge, A. and Montravers, P., 2021. Antimicrobial lessons from a large observational cohort on intra-abdominal infections in intensive care units. Drugs, 81(9), pp.1065-1078.

- Wang, J., Pan, Y., Shen, J. and Xu, Y., 2017. The efficacy and safety of tigecycline for the treatment of bloodstream infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of clinical microbiology and antimicrobials, 16, pp.1-10.

- Wang, L., Tong, X., Huang, J., Zhang, L., Wang, D., Wu, M., Liu, T. and Fan, H., 2020. Triple versus double therapy for the treatment of severe infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 10, p.487865.

- Weiner, L.M., Webb, A.K., Limbago, B., Dudeck, M.A., Patel, J., Kallen, A.J., Edwards, J.R. and Sievert, D.M., 2016. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011–2014. infection control & hospital epidemiology, 37(11), pp.1288-1301. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, L.A. and Kuruvilla, T.S., 2023. Evaluation of in vitro activity of tigecycline against multidrug-resistant clinical isolates. APIK Journal of Internal Medicine, 11(3), pp.150-153. [CrossRef]

- Woodworth, K.R., 2018. Vital signs: containment of novel multidrug-resistant organisms and resistance mechanisms—United States, 2006–2017. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 67.

- World Health Organization, 2014. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. World Health Organization.

- Yaghoubi, S., Zekiy, A.O., Krutova, M., Gholami, M., Kouhsari, E., Sholeh, M., Ghafouri, Z. and Maleki, F., 2022. Tigecycline antibacterial activity, clinical effectiveness, and mechanisms and epidemiology of resistance: narrative review. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, pp.1-20.

- Yaghoubi, S., Zekiy, A.O., Krutova, M., Gholami, M., Kouhsari, E., Sholeh, M., Ghafouri, Z. and Maleki, F., 2022. Tigecycline antibacterial activity, clinical effectiveness, and mechanisms and epidemiology of resistance: narrative review. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases, pp.1-20.

- Yu, W.L., Lee, N.Y., Wang, J.T., Ko, W.C., Ho, C.H. and Chuang, Y.C., 2020. Tigecycline therapy for infections caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing enterobacteriaceae in critically ill patients. Antibiotics, 9(5), p.231. [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.L., Lee, N.Y., Wang, J.T., Ko, W.C., Ho, C.H. and Chuang, Y.C., 2020. Tigecycline therapy for infections caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in critically ill patients. Antibiotics, 9(5), p.231. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M., Xia, J., Zong, Z., Shi, Y., Ni, Y., Hu, F., Chen, Y., Zhuo, C., Hu, B., Lv, X. and Li, J., 2023. Guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and control of infections caused by carbapenem-resistant gram-negative bacilli. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection, 56(4), pp.653-671. [CrossRef]

- Zha, L., Pan, L., Guo, J., French, N., Villanueva, E.V. and Tefsen, B., 2020. Effectiveness and safety of high dose tigecycline for the treatment of severe infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Advances in therapy, 37, pp.1049-1064.

- Zha, L., Pan, L., Guo, J., French, N., Villanueva, E.V. and Tefsen, B., 2020. Effectiveness and safety of high dose tigecycline for the treatment of severe infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Advances in therapy, 37, pp.1049-1064.

- Zhang, R.M., Sun, J., Sun, R.Y., Wang, M.G., Cui, C.Y., Fang, L.X., Liao, M.N., Lu, X.Q., Liu, Y.X., Liao, X.P. and Liu, Y.H., 2021. Source tracking and global distribution of the tigecycline non-susceptible tet (X). Microbiol Spectr 9: e0116421. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Wen, J., Wang, Y., Wang, M., Jia, R., Chen, S., Liu, M., Zhu, D., Zhao, X., Wu, Y. and Yang, Q., 2022. Dissemination and prevalence of plasmid-mediated high-level tigecycline resistance gene tet (X4). Frontiers in Microbiology, 13, p.969769. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Wen, J., Wang, Y., Wang, M., Jia, R., Chen, S., Liu, M., Zhu, D., Zhao, X., Wu, Y. and Yang, Q., 2022. Dissemination and prevalence of plasmid-mediated high-level tigecycline resistance gene tet (X4). Frontiers in Microbiology, 13, p.969769. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Wang, Q., Yin, Y., Chen, H., Jin, L., Gu, B., Xie, L., Yang, C., Ma, X., Li, H. and Li, W., 2018. Epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections: report from the China CRE Network. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy, 62(2), pp.10-1128. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.C., Huang, F., Zhang, J.M. and Zhuang, Y.G., 2023. Population pharmacokinetics of tigecycline: a systematic review. Drug Design, Development and Therapy, pp.1885-1896.

- Zhu, Y., Zhao, F. and Jin, P., 2023. Clinical Manifestations and Risk Factors of Tigecycline-Associated Thrombocytopenia. Infection and Drug Resistance, pp.6225-6235. [CrossRef]

- Zou, C., Xu, C., Yu, R., Shan, X., Schwarz, S., Li, D. and Du, X.D., 2024. Tandem amplification of a plasmid-borne tet (A) variant gene confers tigecycline resistance in Escherichia coli. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 79(6), pp.1294-1302. [CrossRef]

| Tigecycline susceptibility | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tigecycline Resistance Risk factor | No. of CRE (%) | S | R | I | P-value | r2 |

| Wards | 0.1631 | 0.4182 | ||||

| Accident Emergency | 1.43 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Adult care | 1.43 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Casualty | 2.86 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Female Surgical | 4.29 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Gyno | 1.43 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| ICU | 5.71 | 75 | 25 | 0 | ||

| Male Surgical | 14.29 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Maternity | 8.57 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Neonatal | 24.29 | 94.11 | 0 | 5.88 | ||

| Trauma | 2.86 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Not stated (unknown) | 1.43 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| OPD | 11.43 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Pediatrics | 20 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

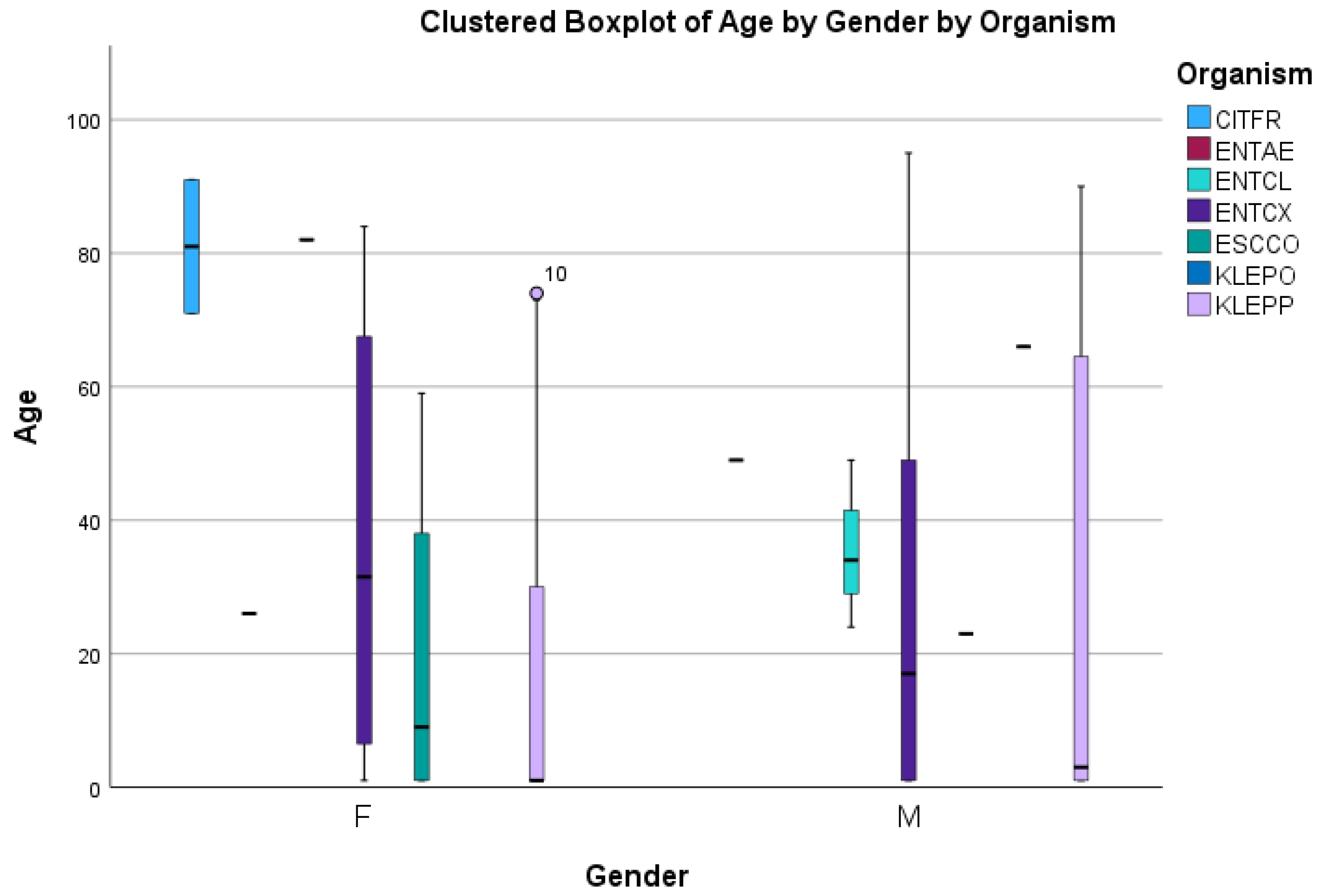

| Age | 0.0011 | 0.9501 | ||||

| 0-1 | 42.86 | 98.57 | 0 | 1.43 | ||

| 2_15 | 2.8 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 16-29 | 11.42 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 30-43 | 8.57 | 98.57 | 1.43 | 0 | ||

| 44-56 | 8.57 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 57-70 | 11.42 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 71-83 | 7.14 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 84-96 | 5.71 | 100 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 97-109 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Gender | 0.001 | 0.991 | ||||

| Males | 47.88 | 97.05 | 2.94 | 100 | ||

| Females | 50.7 | 100 | 100 | 2.94 | ||

| Not Started | 1.43 | 100 | 100 | 100 | ||

| Prio-exposureto antibiotics | 0.0478 | 0.967 | ||||

| antibiotics intake | 75.71 | 98.11 | 1.88 | 0 | ||

| No-antibiotics taken | 24.29 | 94.41 | 0 | 5.88 | ||

| Invasive Procedure | ||||||

| underwent procedure | 5.63 | 75 | 25 | 0 | <0.0001 | |

| No procedure done | 94.37 | 98.51 | 1.49 | 0 | ||

| Hospitalization duration | 0.3679 | |||||

| Prolong | 10 | 98.69 | 1.41 | 0 | ||

| standardized | 90 | 98.68 | 0 | 1.41 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).