As

cs·

cs·=

cs, (

cscs i

d(

cscs·

d·, the bivector operator

cs·

also has the properties of an exponential function, similar to the

ivector operator

cįs·. The operator

is the exponential form of the operator

cs·. Since

=

cs, one more analogy with complex analysis is the notion of the so-called vector logarithmic function

, where

. In addition, Log

,

. Let

sc. The ordered pair of vectors

is the inverse orthonormal basis with respect to the orthonormal basis

of the field of vectors

. For an arbitrary vector

, the vector

is the rotated vector

, in the positive mathematical direction, by the angle

, and the vector

by the angle

. The geometric products of the vector

with the inverse basis vectors

and

rotate the vector

by the angles

and

, respectively, in the positive mathematical direction. On the basis of the geometric products

,

and

and

(

), all other combinations of geometric products of the basis vectors

,

,

and

can also be obtained.

If we introduce the differential operator

, then

. Hence,

and

. Since

and

, the vector operators of partial derivatives are introduced, as a vector analogue of the

Virtinger operators [

16],

Here,

It is important to emphasize that when geometric products and geometric quotients are differentiated, the same rules apply as when ordinary products and quotients are differentiated. Namely,

The vector operator

with the symmetric part of the geometric product

, can be said to be a radial vector differential operator. The vector operator, with the antisymmetric part,

is a transverse vector differential operator. It is obvious that the vector operator

is a gradient operator in polar coordinates. The symmetric part of the geometric product

is the divergence vector (

) of the vector field

, and the antisymmetric part is the

of the vector field

, since

so that

that is,

where

On the other hand, as

cs, it follows that

,

Therefore,

In addition,

In accordance with above,

since

. The vector identity just derived can be obtained explicitly, if we introduce the determinant of the

Jacobi matrix (

Jacobian) of the bijective mapping

, defined by the system of vector equations

and

, as follows

In this case,

, which leads to (

22). The vector

, corresponding to the bivector

of the bivector field

, is the

Lebesgue measure of the infinitesimal surface of the field of vectors

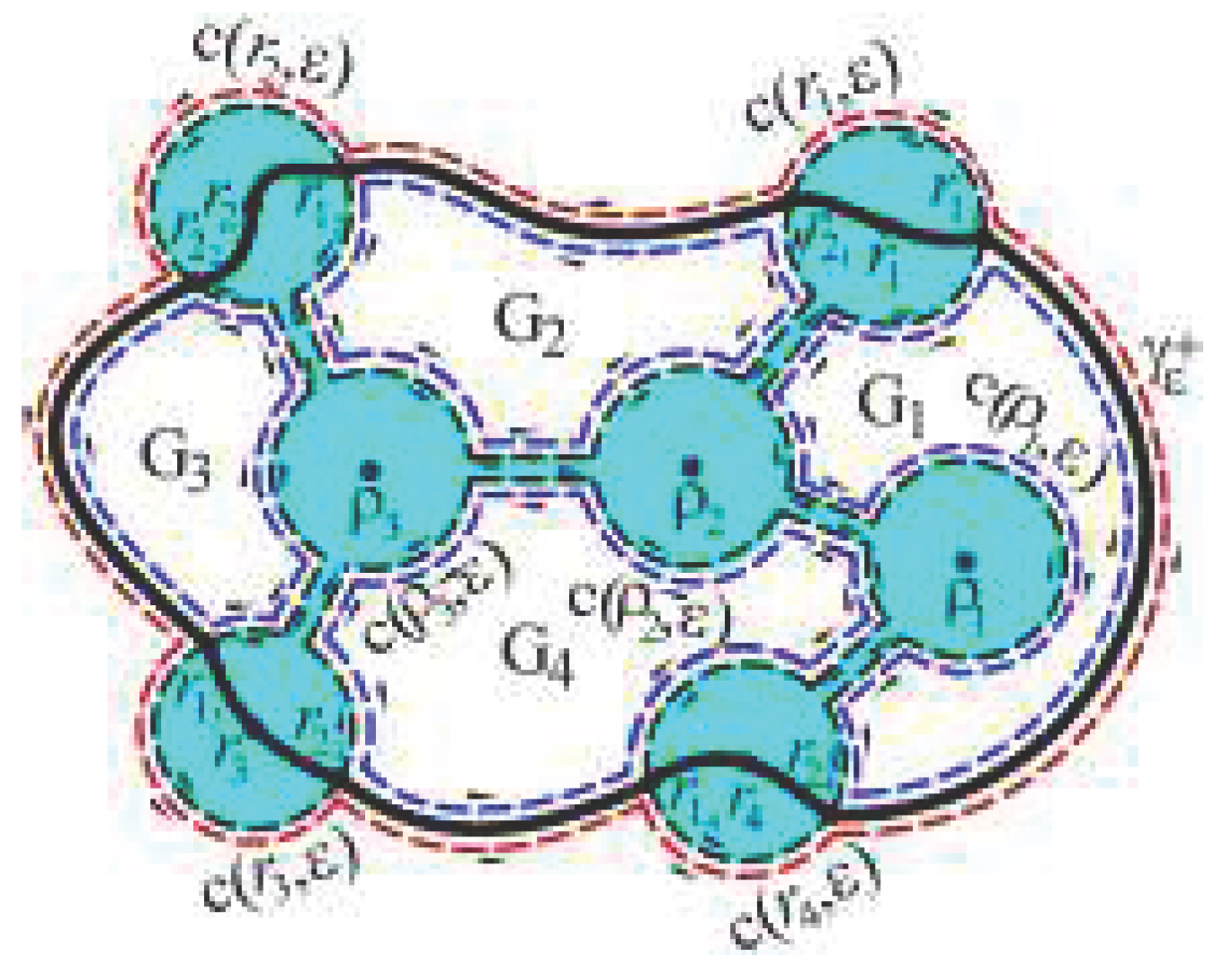

. In accordance with above, the vector integral operator over the closed smooth

Jordan curve

, which is the boundary of an arbitrary region

G in the vector field

, is defined as follows

where

denotes the total value of an improper integral [

9]-[

14], such that

and

denotes the

Cauchy principal value of an improper integral,

are isolated points on the curve

, surrounded by circles

centered at the points

and with an arbitrarily small radius

, which at the points

and

intersect the curve

and do not intersect each other. The set of points

, of

Lebesgue measure zero, is the set of singular points, on curve

, of a field on which the vector integral operator is applied. If also in region

G, bounded by the curve

, there are isolated singular points

, which can be surrounded by circles

, which do not intersect each other, then it is possible to form a simply connected region

S, within which all singularities are, by connecting the circles

, successively, the first with the second, the second with the third, etc., using parallel straight line segments

and

, at a mutual distance

, as well as by connecting the circles

on the curve

with the circles

, using the parallel straight line segments

and

, at a mutual distance

. The boundary

of the singular region

S (blue region in

Figure 1), inside region

G, divides region

G into

n subregions

.

The vector integral operator

where

is the residue operator in region

G of the field of vectors

. The vector integral operator in region

G is as follows

where

,

,

and

Finally, on the basis of the result of the

Kelvin-Stokes theorem (

Green’s theorem) [

6],

If there is a limit

, and

tends to infinity as

tends to zero, then the limit

is also infinite. In this emphasized case, the limit

leads to the indeterminate form of the difference of two infinities, which has a finite value. According to (

34), since

it follows that

If

, then

. In addition,

since

Clearly,

.

2.1. Integrals of Scalar and Vector Fields

The vector differential of a scalar field

is as follows

where

. The second vector partial derivative of

F is the first vector partial derivative of the vector field

, so that

If

and

are uniform vector fields, then by applying the vector integral operator (

36) to the scalar field

F, a vector integral identity is obtained

where

. The integral identity of complex analysis, which is an analogue of the vector integral identity (

42), is the integral identity of

Cauchy’s integral theorem [

7].

As

and if, in addition,

, then

, that is,

A vector field , satisfying theCauchy-Riemann condition , is said, analogous to complex analytic functions, to be an analytic vector field. Hence, an analytic vector field is a vector derivative of the Laplace scalar field F. Clearly, the coordinate components of the analytic vector field are also Laplace scalar fields.

Assume that the analytic vector field

, as the vector derivative of the

Laplace scalar field

F, is not defined at the point

, where

G is a region in the field of vectors

, bounded by a closed smooth

Jordan curve

, as well as at point

on curve

. The vector integral identity

is a vector analogue of the integral identity of

Cauchy’s integral theorem, which is slightly generalized, since in this emphasized case

If

is a differentiable (regular) vector field, but not an analytic vector field, in an arbitrary region

G of the vector field

, bounded by a closed smooth

Jordan curve

, the integral identity

where

, is a vector analogue, in the field of vectors

, of the surface (spatial) derivative, which was introduced, into complex analysis, by

Pompeiu[

8], originally calling it the areolar derivative. Similarly, based on the vector identity (

17), the so-called cumulative surface (spatial) derivative of the vector field

can be defined as follows

According to (

47), if

is a regular and uniform vector field in the

-neighborhood

of its singular point

and

, then

If

, then

, which is another vector analogy to the well-known result of complex analysis. Let

be an analytic vector field, such that

leads to the determinate form only after the application of

L’Hospital’s rule

n times. Then, the vector formula for

, being analogous to the complex analysis formula, can be obtained via the vector identity

, see (

44), where

. Namely, since the same vector identity applies to the analytic vector field

, it follows that

Accordingly, applying

L’Hospital’s rule,

Further, since the vector field

is an analytic vector field, it follows that

This means that

L’Hospital’s rule can be explicitly applied to the vector field

.

If some analytic vector field

is regular in an arbitrary region

G bounded by a closed smooth

Jordan curve

, then for the vector field

where

, according to (

45), (

52) and (

54), the following is true

Hence

since

, whenever

. This is the vector analogue of the well-known

Cauchy’

s integral formula.

If the vector field

is such that the scalar fields

F and

have continuous first partial derivatives in region

G, bounded by the closed smooth

Jordan curve

, almost everywhere (everywhere except on the singular set of points of

Lebesgue measure zero), then by applying the vector integral operator (

36) to the vector field

, one comes to the following vector integral identity

since

Clearly, in the general case

is not the same as

. Namely,

So,

differs from

. Accordingly,

since

which can be explicitly obtained if in (

17)

is formally replaced by

. Therefore, the two identities 5. and 6., on page 85., in Section 3.16., Chapter 3., in [

15], should be replaced by: 5.

and 6.

if

is either an analytic vector field (

) or a

Laplace vector field (

). In both of these cases, the vector field

satisfies

Laplace’s equation

.

On the other hand, let

be continuous in an arbitrary region

G bounded by a closed smooth

Jordan curve

, in which the partial derivatives

,

,

and

exist and satisfy the

Cauchy-Riemann equations

Then, according to the

Looman-Menchoff theorem [

1], both the analytic vector field

and the

Laplace vector field

can be said to be regular (holomorphic) vector fields in

G. Therefore, on the basis of (

56),

In addition,

where

and

. These vector integral formulas are analogous to the

Cauchy-Pompeiu integral formula of complex analysis [

17].

On the basis of the previous results one can say that there is a complete analogy between complex analysis in

and real vector analysis in

, thus all the results of complex analysis are applicable to scalar and vector fields in

and vice versa. In doing so,

z is formally replaced by

, and the imaginary unit

i, more precisely the

ivector

į, is replaced by the vector

and vice versa (

and

į). This conclusion can be even more obvious if a formally analogous method of deriving previously obtained vector identities is applied to the field of complex vectors

, which corresponds to the

ivector field (field of complex numbers)

, in the sense of the correspondence:

and

į≒

, where the unit vector

and the pseudo-unit vector

) form an orthogonal basis of the field of complex vectors

, whose algebraic structure is based on the geometric product of two complex vectors

as follows [

9]