1. Introduction

Information and communication technologies (ICTs) have become ubiquitous in daily life, fundamentally transforming both remote and face-to-face interactions. This pervasiveness often results in individuals being physically present yet emotionally disconnected, enclosed in their digital spheres [

1,

2]. While existing research primarily focuses on technology’s role in facilitating remote communication, fewer studies examine in-person interactions [

1,

3], particularly among strangers in co-located settings. Our research addresses this gap by investigating the design of social experiences for groups of strangers, exploring how technology and thoughtful design can foster dynamic social interactions.

A responsive environment, as defined here, is characterized by data processing and media choreography processes that operate in real-time and are synchronized with participants’ movements [

42]. We underline that our environments are

responsive in that our feature analysis and media choreography processes run concurrently with participant activity. Our multi-modal media vary in real-time with effectively zero latency relative to participants’ physical engagement, enabling a multi-modal coupling essential for felt tangibility and coherence of bodily experience.

Responsive environments incorporating multiple modalities have demonstrated various benefits, including the creation of more diverse experiences, reduction of social anxiety [

43], enhancement of embodied interaction, and support of social learning [

6]. The system has been methodically designed to complement social environments, ensuring that media output and behavioral responses integrate naturally with common social scenarios, such as dining or socializing. For example, there is growing interest in combining food with multisensory experiences within the realm of Human-Food Interaction (HFI).

Educatableware,kadomura2013educatableware introduces utensils that emit sounds to promote better eating habits in children. Spence et al. [

6] emphasize the complexities of digitizing taste and smell, suggesting a holistic approach engaging multiple senses. Gupta et al. [

7] note that participants may feel responsible for technologically-mediated outcomes and personal well-being within food-related contexts.

Olsson [

9] emphasizes the significance of distinct technological and design approaches when designing for enabling versus enhancing social interaction. However, the differentiation between these two concepts remains ambiguous in current research [

9]. This highlights the necessity of defining technology’s role by considering various contextual factors [

10]. In response, our study incorporates a temporal perspective, specifically focusing on the dynamic social stages that emerge as strangers gradually integrate experiences and responses with each other over time. We have developed and evaluated optimal design solutions for unfamiliar group dynamics across different stages: ice-breaking, exploration, and engagement. Key research inquiries stemming from our work include:

How does the implementation of experiential design and technological affordances in augmented multisensory interventions affect the dynamics of social interaction over time?

What role do haptic, auditory, visual, and motor interactions play in affecting collective experience and user engagement?

Our research identifies three pivotal themes for technology-mediated approach in designing co-located interaction: relational dynamics, improvised activities, and interaction over time. Utilizing a mixed multimodal methodology, we integrated continuously responsive video, sound, and haptic elements to augment physical engagement and coordination. We invented four responsive media interventions, encompassing computational tools, augmented spaces, shared haptic feedback, and multisensory feedback mechanisms, and subsequently evaluated their efficacy across two social settings. Our results underscore the responsive mutlimodal environement’s potential as a research instrument that can potentially foster enriched, embodied social interactions. We summarized these insights as design recommendations for the broader research community.

2. Literature Study

2.1. Understanding the Sociotechnical Context of Co-located Interaction

The domain of technology-mediated co-located social interactions encompasses diverse research trajectories, including interactive game [

18,

19], interpersonal conversational dynamics [

20], social facilitation mechanisms [

21,

22,

23], and collaborative experiences within immersive virtual and mixed reality environments [

24,

25].

Prior investigations have yielded novel methodological approaches in this domain. Lagom et al. [

20] developed a bio-responsive wearable interface in the form of a volumetric floral apparatus that monitors vocal participation patterns. This system implements multimodal feedback mechanisms, incorporating both haptic and visual modalities to optimize conversational equilibrium in group interactions. Simliarly, Hotaru [

40] is a lighting bug game with two-player movement-based and costume-enabled gameplay. Wearables with technology support can enhance bodily expression and social signaling, as highlighted by the strong concept of "interdependent play" [

21,

39]. Additionally, the

Element system [

26] leverages principles of tangible interaction design through a shape-morphing luminaire that exhibits dynamic chromatic and morphological variations corresponding to varying degrees of affective engagement. This interface facilitates the interpretation of emotional states within social contexts through ambient environmental feedback.

Advancing this research, scholars also emphasize the importance of incorporating physical aspects, such as proximity, orientation, and position, movement to influence interpersonal dynamics [

27]. In Hall’s [

29] theory, proximity interaction refers to the way individuals use and interpret physical distance as a form of communication.

Digital Proxemics,10.1145/3491102.3517594 explores the nuanced perception and reciprocation of social closeness in adaptable virtual environments. This framework includes variables like activity types, auditory cues, and broader environmental factors. Such as

Six-feet,postma2022sixfeet, a novel digital-physical sports platform that allows participants to play rigorous, collaborative sports at a six feet distance. They propose employing technological interventions that use proxemic indicators to augment the sense of communal togetherness. Szu-yu et al. [

31] also elucidate the critical significance of implementing technological interventions that integrate multimodal nonverbal communication channels—including kinesthetic gestures, prosodic variations, facial affect displays, and proxemic behavioral indicators—to enhance collective social presence and interpersonal synchrony in shared experiential contexts. For example,

Tableware,lyu2020tableware presents an array of augmented champagne vessels that facilitate gesture-based coordination through diverse sonic feedback mechanisms, enabling multi-player collaborative musical composition through coordinated interactions.

Drawing from this theoretical and experimental research, we investigate a novel technology-mediated approach to augmenting human perception, encompassing proxemic awareness, kinesthetic dynamics, and multimodal sensory integration. This investigation examines how computational mediation can shape human behavioral patterns and enhance mutual understanding and social relationships within group interactions.

2.2. Responsive Environments

Responsive Environments (ResEnv) are spaces equipped with media and technology designed to create dynamic, immersive, and transformative experiences that respond to the behaviors and actions of participants [

42]. These environments interact with the people they serve, are responsive to their actions, and incorporate social and cultural values [

45]. ResEnv manifests in various forms—some innovations are invisible, such as sensors embedded within the space, while others are more obvious and observable, such as those utilizing tangible interfaces or objects. The manner in which technology is utilized within these spaces dictates how participants interact with the installation, varying from natural reactions to mechanical responses [

42].

2.2.1. Responsive Environments Integrating Multimodal Medias

Research in responsive environments with multimodal media has evolved significantly since its inception. Originally developed for individuals with developmental disabilities, this approach has proven effective for both therapeutic and relaxation purposes. The concept emerged from the 1960s sensory cafeteria [

12], with a significant advancement in the 1980s through the Snoezelen Rooms by Hulsegge and Verheul, which introduced controlled, interactive media for therapeutic applications [

13].

Recent implementations have expanded to diverse populations and contexts. In therapeutic settings, examples include the Land of Fog [

16], which enhances socialization in children with ASD through full-body interaction, interactive sound, and virtual avatars projected in a large-scale environment, and MEDIATE [

17], a multisensory space featuring dynamic digital elements that respond to interpersonal distances through adaptive lighting and visual transformations. In healthcare environments, such as Ambient Intelligence systems [

46] have been developed to enhance patient well-being and emotional regulation. DeLight [

47,

48] demonstrates how responsive ambient lighting environments can facilitate relaxation and stress reduction by dynamically adjusting illumination based on users’ physiological signals.

2.2.2. Responsive Environments in Social Contexts

Research on responsive environments in social settings has highlighted the importance of natural, engaging interactions within daily activities. Gupta et al. [

7] demonstrate how design elements that promote playful sensorimotor engagement can enhance social interaction, particularly through food-based multimodal storytelling systems that encourage active participation. The significance of food-centered social interactions has been further validated by Boltong et al. [

14], who found that shared eating and drinking experiences positively impact patient recovery after chemotherapy. These findings emphasize three key benefits of augmented sensory experiences in social contexts: behavioral adaptation [

8], enhanced well-being [

7], and strengthened social connections [

41].

Building upon these frameworks of social interaction and environmental responsiveness, our work implements a sophisticated multi-modal system that seamlessly integrates visual, auditory, and haptic feedback, responding in real-time to participants’ natural gestures and full-body movements. The system has been meticulously designed to complement existing social dynamics, ensuring that technological interventions enhance rather than disrupt authentic social experiences in everyday settings. By carefully calibrating media outputs and behavioral responses to align with natural social scenarios, particularly in contexts like dining and casual socializing, the system facilitates organic social interactions while preserving the spontaneity and fluidity of natural social engagement. This approach represents a significant advancement in creating technology-enhanced environments that support and enrich social connections within the familiar contexts of daily life.

2.3. Design Attributes for Technology-Mediated Social Activity

As technology increasingly mediates everyday social interactions, identifying effective design attributes for co-located social experiences becomes critical. Previous research by Rinott and Tractinsky [

10] has established foundational design attributes for technology-mediated co-located social interactions by emphasizing

participant relationships, group size, spatial configurations, and entrainment stimuli. Building upon this framework, particularly focusing on interactions among unfamiliar individuals in group settings, we proposes three additional design attributes:

relational interaction,

improvised activity, and

interaction over time. These attributes specifically address the unique challenges and opportunities in designing technology-mediated experiences that facilitate social connection among unfamiliar participants.

2.3.1. Relational Interaction (Attention)

This principle is a concept that underscores the significance of coordinated bodily behaviors and cognitive expressions during social encounters. It is rooted in the principles of enactivism and embodiment, and greatly influences the development of social cognition [

4,

32]. We employed media interventions to enhance interpersonal relational awareness to foster coordinated experiences through stimulus-joint attention coordination. This involves examining how one’s movements affect others’ sensations using media feedback, investigating how design and technology can help in forming mutual awareness, and facilitating rewarding coordinated interactions. All phases of this attunement, including coordination that may not be complete synchronization are also considered as part of the coordination experience. Isbister et al. [

33] introduce

"interdependent wearables" manifested for example, in

Hotaru, where two players collaborate by holding hands to transfer "energy." Similarly, in our work, we emphasize treating all participants as reciprocating peers, not solipsistic individuals. Our design allows participants to perceive the energy of others’ movements through real-time vibrotactile feedback and a composite of movement activity from multiple individuals, not just one person.

2.3.2. Improvised Activity

This principle centers on the concept of a spontaneous motor process guided by sensory mediation. Crucially, we suggest that while joint attention often manifests through visually oriented metaphors, a more effective approach involves controlling various modalities—such as speed, volume, and texture perception—viewing the process as a dynamic rather than static paradigm [

34]. Therefore, technologically-mediated social activity, particularly when employing improvisational interaction models, offers not only an actively-engaging environment but also a participatory space. In such a space, participants can actively perceive and collaboratively regulate the sensorimotor interactions within play [

34].

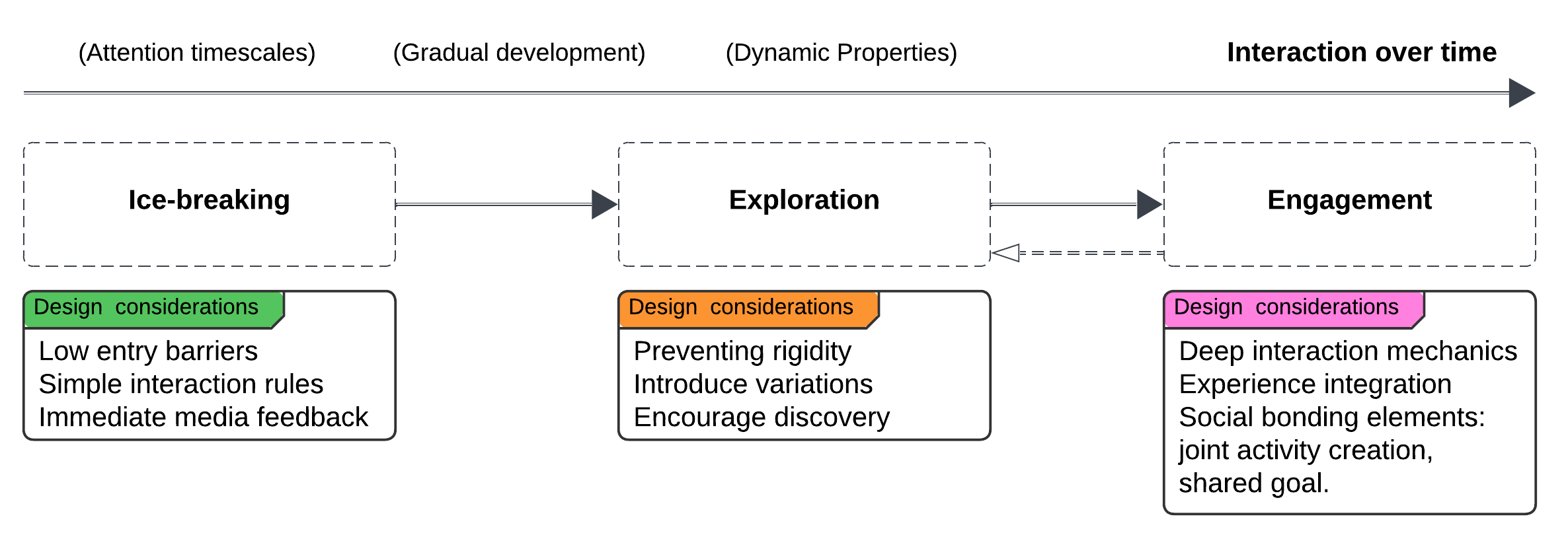

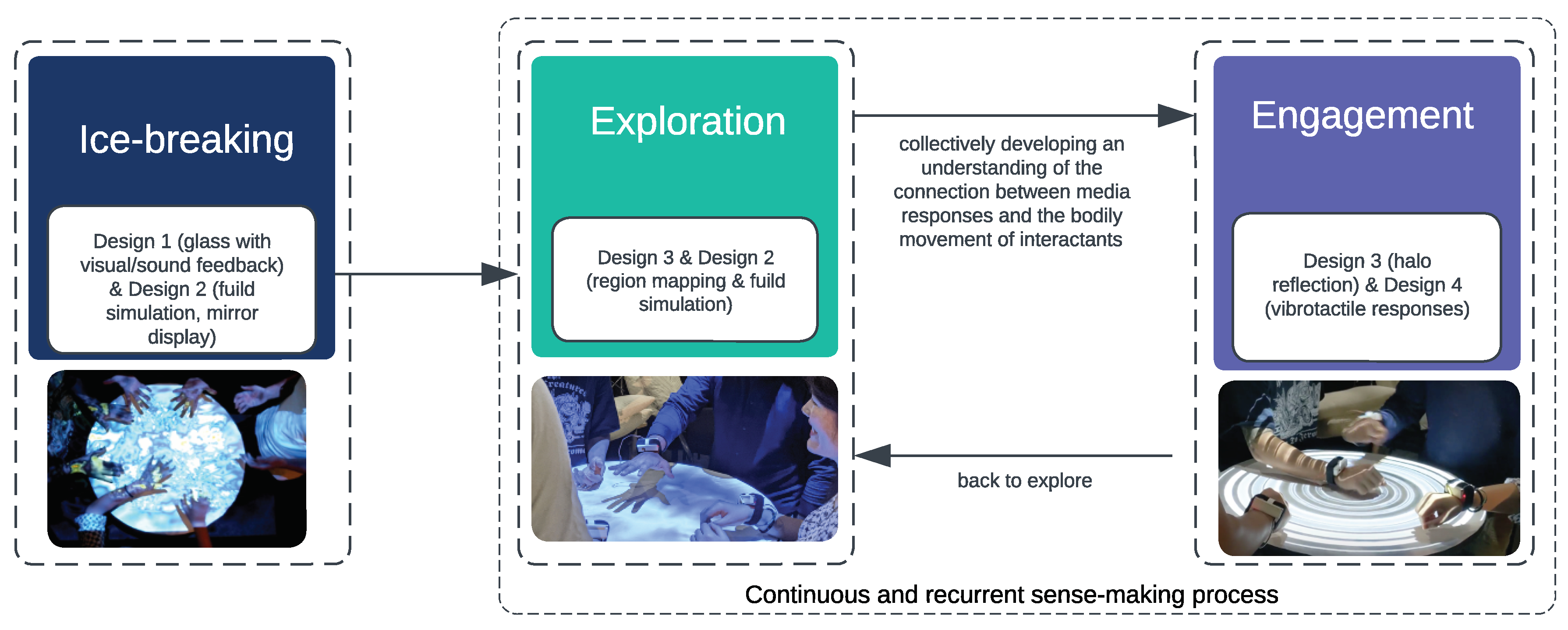

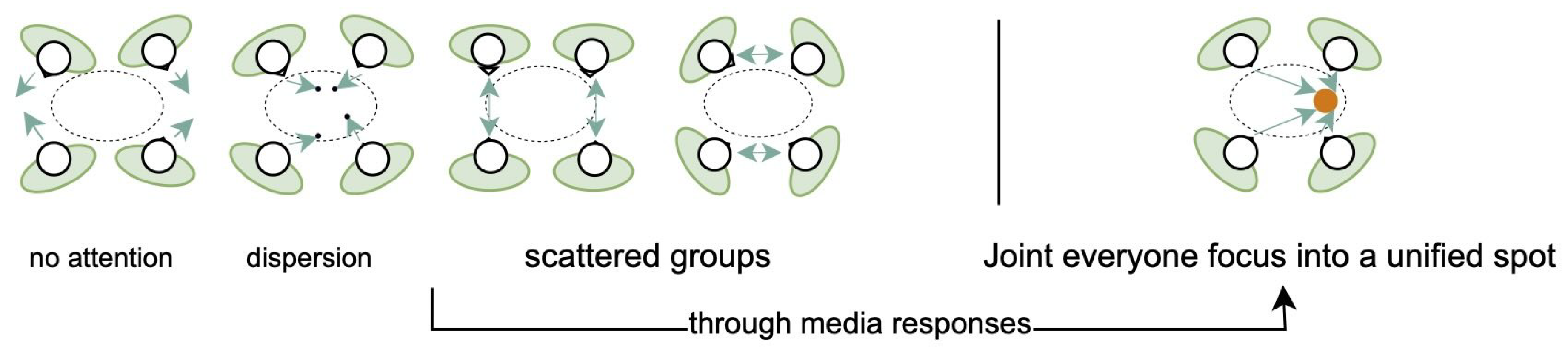

2.3.3. Interaction Over Time

With a focus on attention timescales, this principle centers around transitions, and dynamic properties that develop gradually, see

Figure 1. This phenomenon is exemplified by Hayes and Loaiza’s [

34] study of technologically-mediated musical improvisation, where they emphasize the importance of "organizational dynamics that emerge over time between group members" (p. 281). Moreover, Colombetti [

35] explores the phases of dynamic social interaction, highlighting that once participants reach a certain level of familiarity, introducing variation and new elements can help prevent rigidity. Hence, considering interaction over time helps designers in contemplating how interactions evolve, encompassing the initiation of interactions (ice-breaking), preventing interactions from becoming rigid as participants’ attention and motivation decline over time (encouraging continuous exploration), and integrating experience and responses. We propose three distinct but overlapping stages of social interaction among strangers that can be useful for design methodologies:

ice-breaking,

exploration, and

engagement. These suggest the need to customize different media and design solutions to facilitate each of these stages.

3. Implementation

3.1. System Configuration

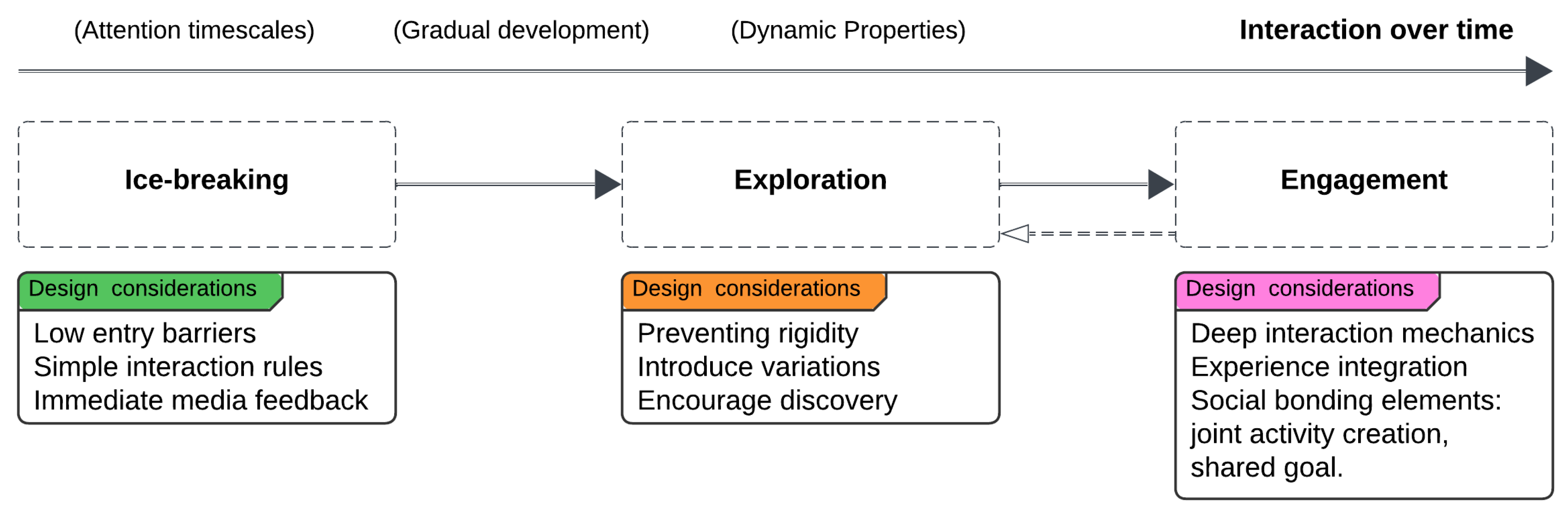

As depicted in

Figure 2, our system consisted of three components: (i) four responsive champagne glasses with infra-red LEDs affixed on the top edge of the glass; (ii) ambient projected media with real-time responsive video and sound; and (iii) a wearable hardware device equipped with an inertial measurement unit (IMU) movement detection sensor and haptic motors output, designed to be worn on the right wrist. The projected visual and audio cued participants to changes in their movement and in turn served to coordinate and modulate their own bodily entrainment in response. These wearable devices have proved useful as versatile and expressive instruments for modulating real-time visual, auditory, and haptic mapping. The wearable device comprised a 3D-printed container involving a Feather M0 WiFi module-based board, a 3.7-volt battery, a DRV2605L motor driver, a flat-type linear motor, a BNO055 IMU sensor, and an adjustable wrist strap to hold it in place. The wireless sensor package, consisting of a 3-axis accelerometer, gyroscope, orientation sensor, and haptic driver and actuators, was connected to a Feather M0 WiFi with ATWINC1500 microcontroller and embedded into the wristband. The microcontroller was programmed to simultaneously convert raw data into an Open Sound Control (OSC) data stream and then send it via WiFi to a computer running the graphical creative coding environment Max/MSP/Jitter

1, which mapped normalized sensor data to multimodal media feedback comprising: (i) digital sound synthesis; (ii) responsive fluid simulations; and (iii) haptic patterns that are felt on the wrist (see

Figure 2).

3.2. Software Implementation

BNO055 IMU sensors were programmed to send UDP packets involving 9-DOF features values at a programmable frame rate to configurable IP addresses and wireless networks. Mainly three types of sensor data were detected from linear acceleration: vector, gyroscope, and absolute orientation. The acceleration and orientation were first calibrated to remove the effect of constant acceleration due to gravity. Then, the acceleration magnitude, gyroscope magnitude, and orientation magnitude were defined as the Euclidean norm, scaled from 0 to 1. These magnitudes yielded a correlation coefficient measurement in a moving window of variable size - as an index of the relative ’sameness’ occurring in different periods of time. Covariance values approaching 1 suggested that the movements were more positively related for longer periods of time. A covariance value approaching 0 suggests a negligible relation. We analyzed and compared the four sets of variable lists from the four different accelerometer magnitude values of each sensor. Our algorithm iteratively compared the data from a participant’s sensors to the data coming from each of the other participants, and then determined the covariance value of their respective movements in the given time frame (window size).

4. Design in Multisensory Interventions

In this section, we introduce four design interventions that are inspired by advancements in sensory stimulation. These interventions have been developed based on three design frameworks: enhancing relational interaction, considering interaction over time, and promoting collective play.

4.1. Design Intervention 1: Interactive Everyday Objects with Visual and Auditory Feedback

Social-cultural context strongly condition the use and significance of made objects [

36]. Our work exploits computational champagne glasses, as the medium of mediation due to their inherent social connotations and versatile nature, which sets them apart from props that offer artificially restricted degrees of freedom.

To measure changes in weight, we affixed four 1.5-inch square force-sensitive resistors (FSRs) to a fixed position on the table’s surface, concealed by a tablecloth. These FSRs were connected to an Arduino Uno board discreetly positioned beneath the table. The FSRs detected weight changes when participants placed the glasses in that position and poured fluid into them. Furthermore, each glass was equipped with an overhead-mounted infrared (IR) LED, enabling an overhead IR camera to track its position and project visual ripples in its corresponding cup position. The changes in weights served as input values with a threshold to adjust the volume of a bubble-like sound played back from speakers, with higher fluid weights corresponding to higher pitch sounds. The size and color of the virtual ripples reflected the weight of the fluid in the glass. Moreover, these visual ripples followed the movements of the glass as participants raised or moved it. In

Figure 3, participants interacted with the visual ripples by engaging with their neighbors, observing the overlap when two virtual ripples crossed, and purposely moving the ripples over the food and others’ plates.

Additionally, we incorporated four white plates as ’menus’ to display the cooking process and indicate the arrival of food. These plates displayed videos that had been designed in advance which displayed the progress of cake-making.

4.2. Design Intervention 2: Regional Mapping with Visual and Auditory Stimuli

In the early stages of social interactions, individuals often exhibited reserved behavior, avoided direct eye contact expressing unfamiliarity and discomfort, and hesitated to participate in discussions. Our investigation sought to understand how responsive visual and auditory modalities, integrated with a specific design approach, could impact this reserved demeanor and encourage participants to engage with others in a more playful manner.

The first approach utilized a hierarchical visual dynamic, where the most vibrant visual feedback occurred when a relatively larger amount of movement activity was detected. The second design approach focused on nurturing a sense of togetherness in movement by constructing an augmented shared space using various acoustic responses, referred to as region mapping. These two approaches were intertwined: the first aimed to motivate more bodily movement, creating a continuous flow of embodied action over time, while the second aimed to generate collective awareness throughout this continuous movement.

The dynamic and interactive simulation fluid was projected over the table surface (see

Figure 4). We describe relationship between the actions and the changes in fluidity of the visual elements and the sonic output as follows:

Fluid stimulation: A visual water fluid simulation dynamically displayed bodily movements and their related movement tracks, and gradually disappeared once the bodily movement stops. Additionally, more movement (of more than two people) or more volume of the fluid yielded correspondingly more variety of the colors, with denser water waves also appearing.

Mirroring display: The motion-generated visuals were mirrored onto nearby spots, promoting self-awareness, while also attracting others’ attention.

Region mapping: here we divided the tabletop into five regions as potentially sites of bodily movement, and mapped distinct sound processes to each region. Using an overhead webcam we mapped the degree of movement within each region to its associate sound.

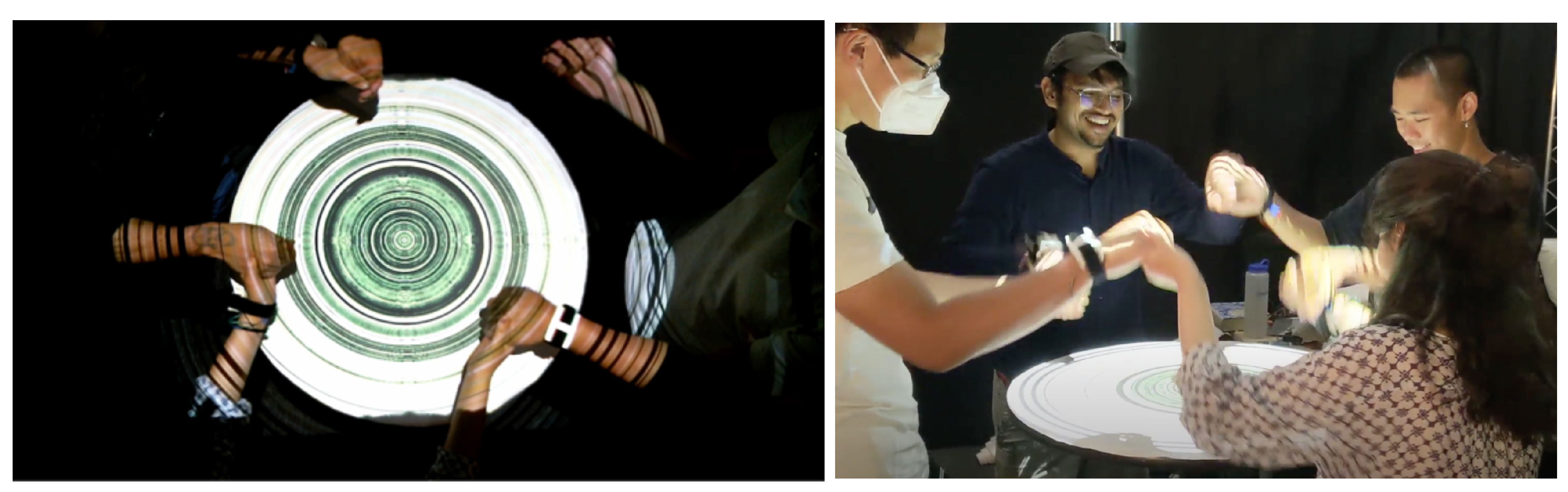

4.3. Design Intervention 3: Coordination Exploration with Visual-Haptic-Audio Responses

In intervention 3, we projected onto the table a `halo’ whose fluctuations of diameter and color reflected level of engagement from all the participants. (See

Figure 5) A covariance coefficient between degrees of camera-tracked movement varied the diameter of the halo. Higher correlation values mapped to more colorful and larger halos. However, an individual’s movement or coordinated movement among just a pair of people only yielded a smaller, monochrome halo. We also mapped the covariance coefficient to the playback speed and amplitude with a fixed frequency ratio to the state-variable sound filter. More strongly coordinated movement yielded a softer, more natural, less distorted sound.

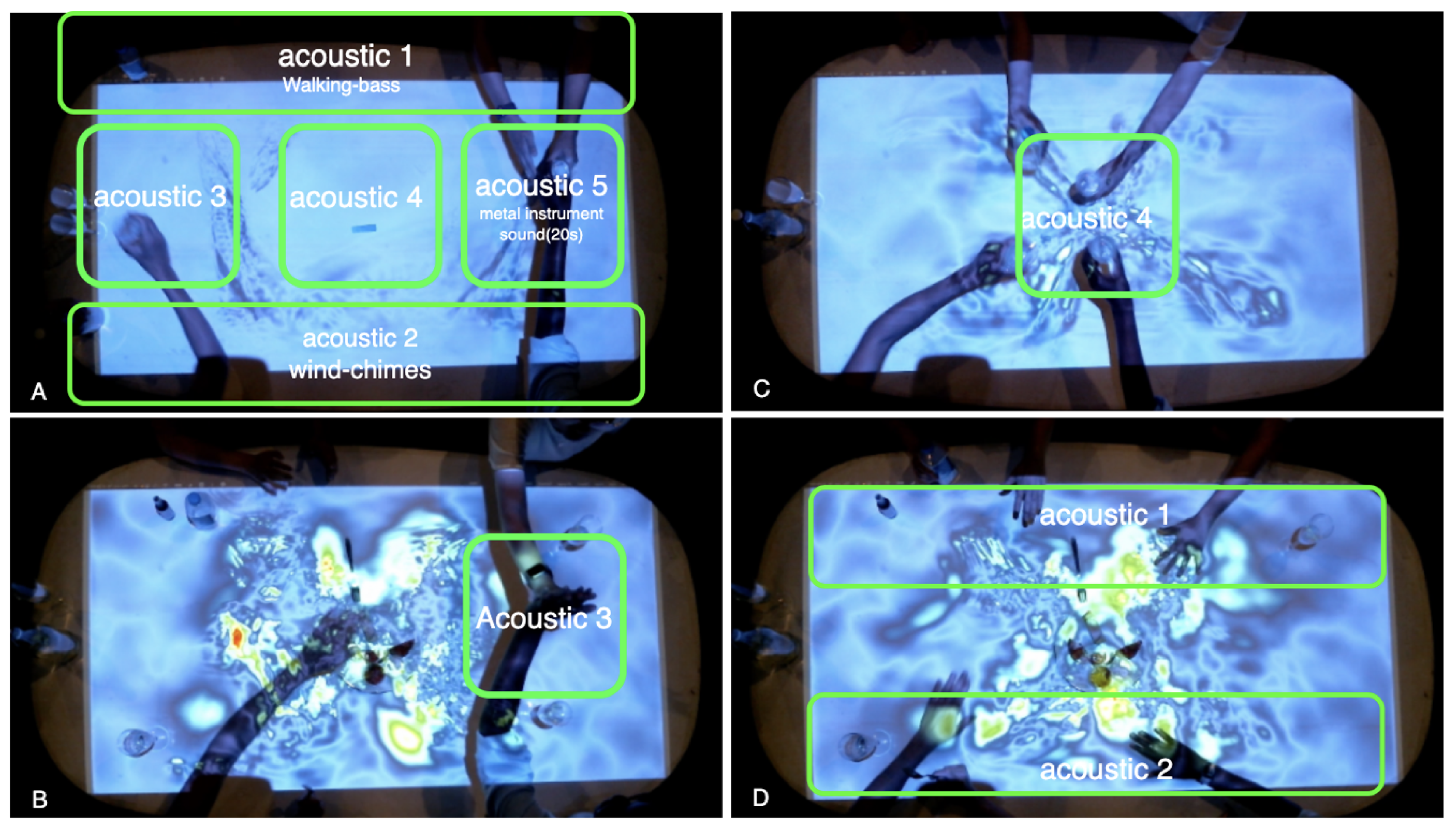

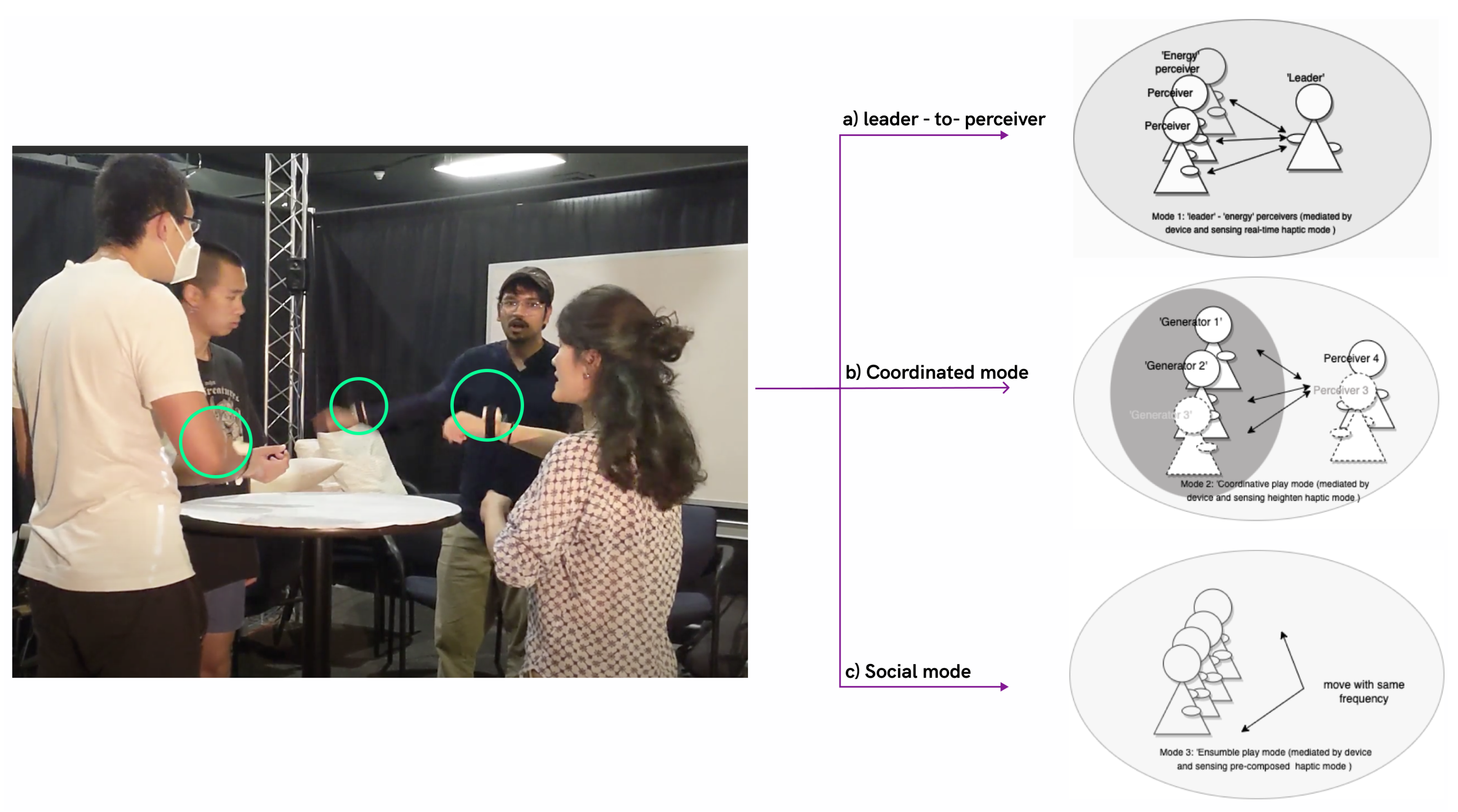

4.4. Design Intervention 4: Dynamic Social Patterns Exploration with Vibrotactile Response

We developed three social interaction modes (

Figure 6) using real-time haptic responses generated from participants’ right-arm movements to encourage joint attention and coordinated action. The aim was to sense how participants regard themselves as a collective or as atomic individuals.

Leader-to-Perceivers Mode: Participants reciprocally sensed others’ energy of movement, computed as a function of movement duration and intensity, mapped to haptic feedback. We found that participants spontaneously adopted a leader-to-perceivers mode: one participant would become more active while the others voluntarily moved less and paid attention to sensing the emergent leader’s energy.

Coordinated Movement Mode: In this mode two or three participants moved at a similar pace according to the covariance measurement. The remaining participant(s) acted as perceivers, sensing an aggregated and heightened vibration sensation. The more participants coordinated their movements, the stronger the felt vibration.

Social Mode: all participants intentionally moved with the same perceived pace within a period window. This led to the triggering of a unique, predetermined vibrotactile feedback experience that was collectively perceived – that is, each participant felt the same haptic pattern.

5. Experimental User Study

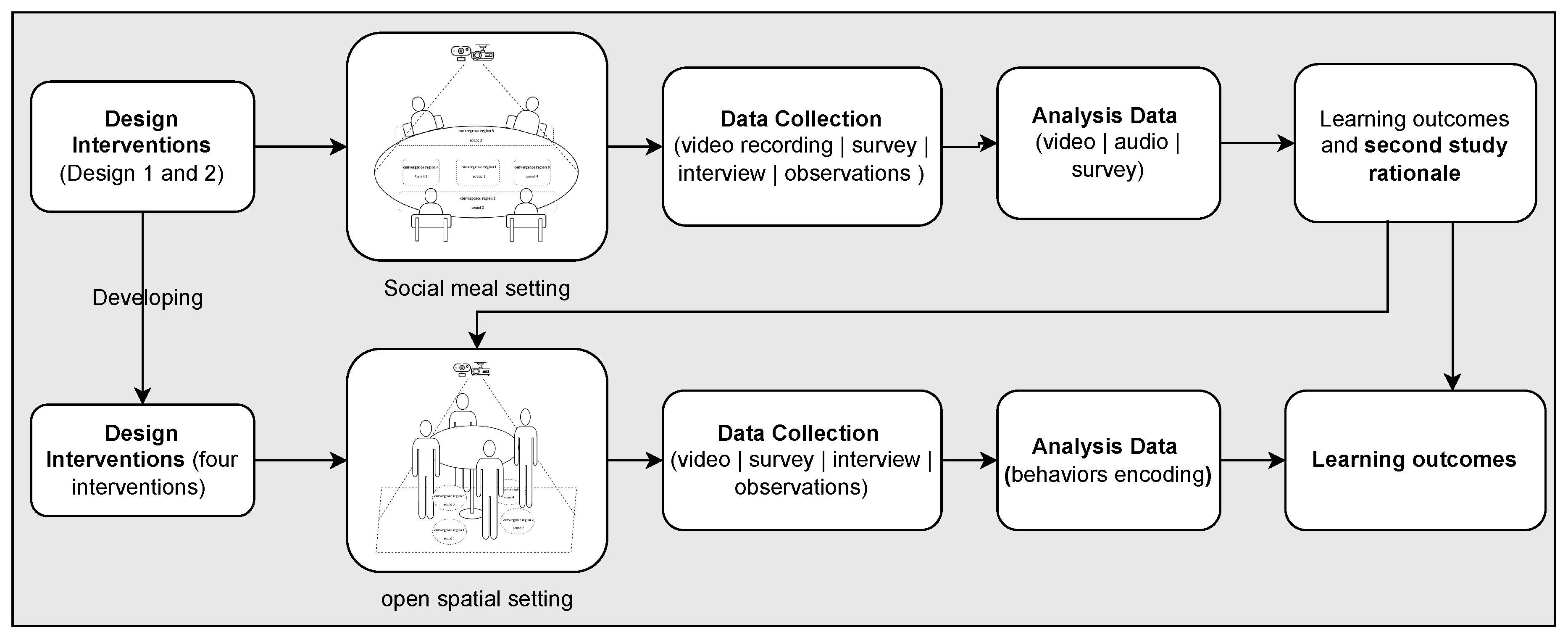

As depicted in

Figure 7, The first study was conducted as a pilot study in a social meal setting with the aim of evaluating Design Interventions 1 and 2. Based on the findings from this preliminary investigation, participants reported experiencing limited mobility and flexibility due to predetermined positioning and separation (COVID-19 precautions) while seated. We developed two additional media interventions tailored for open-ended social play setting designed to encourage exploration and to gain insights about effectiveness of media design in affecting social interaction.

5.1. Participants

We had 16 participants, consisting of 8 males and 8 females, all aged 18 years or older (with an average age of 29 years). Four people were assigned to a group and each participant was given a wearable device. We conducted two studies in each of two social settings, yielding a total of four studies. One session took place as a social meal setting and the other as an open-ended play setting. Prior to the study, participants were provided with an IRB-approved informed consent form via email, which they reviewed and signed electronically upon scheduling their participation. All participants voluntarily took part in the experiment and completed a screening form, which included questions regarding any food allergies they may have had. As an incentive for their participation, each participant was given a gift card upon completion of the study. Before starting each session, we asked the participants to confirm that they were not acquainted with each.

5.2. Pilot Study: A Social Meal Setting

5.2.1. Objectives

Food-related activities are often linked to creativity, enjoyment, gift-giving, connectedness, and relaxation [

7,

14]. We developed two design approaches suitable for such occasions: An interactive tabletop visually displaying bodily movement tracks using simulated fluid; secondly, a set of champagne glasses and plates serve as a "display" to signal the arrival of food (as described in Intervention 1 & 2). The objective of the study was to examine the efficacy of these interventions from two perspectives: their impact on social behavioral expression and participant engagement. Before starting, participants were simply informed that the wearable device tracks movement and provides vibrant feedback. There is no perceived risk involved. The study setting is interactive, providing an opportunity for media manipulation. Participants were deliberately not informed about specific measurements.

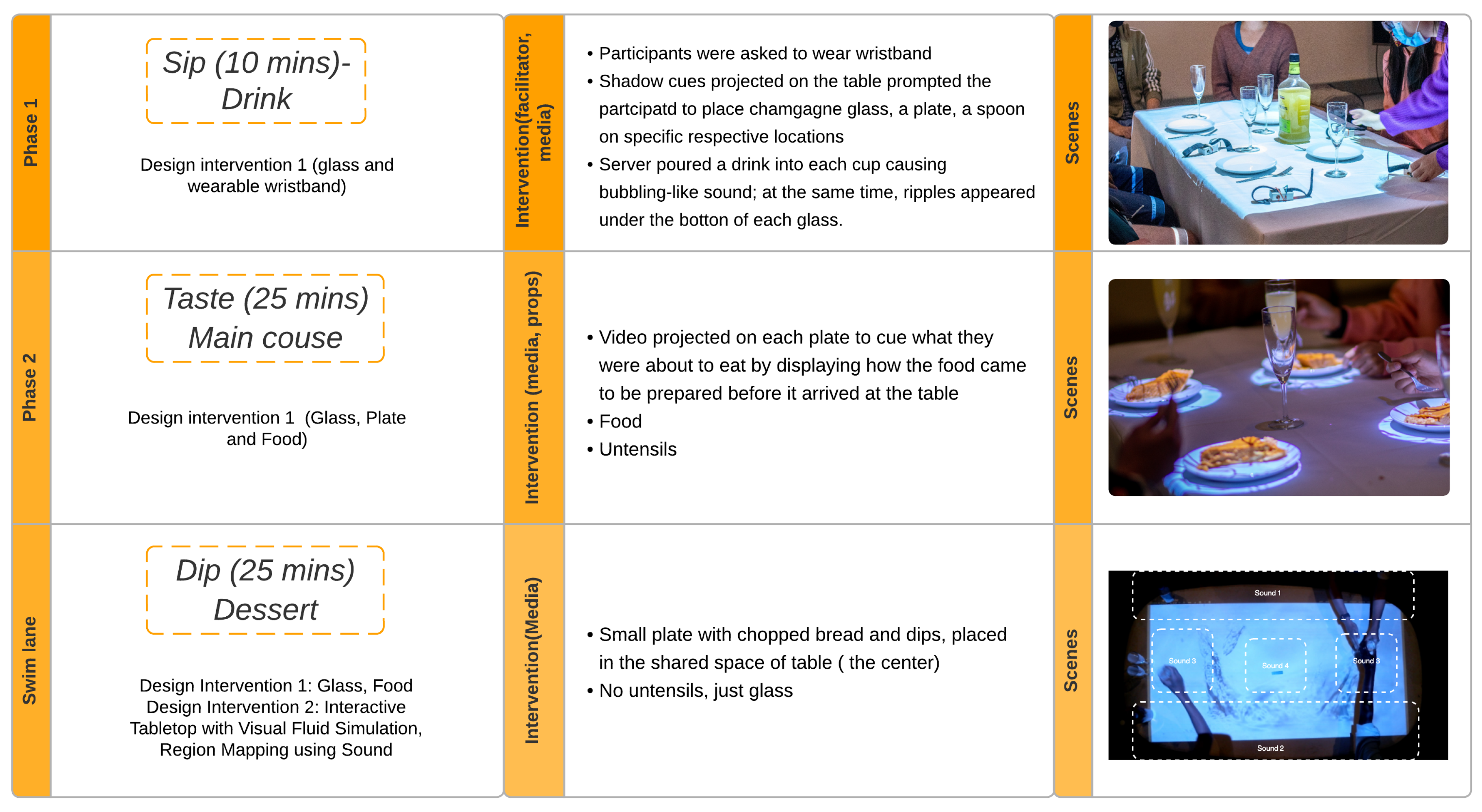

5.2.2. Study Procedure

As depicted in

Figure 8, in the social meal study procedure, the initial phase–henceforth referred to as the

Drink phase–commenced with the facilitator introducing the objective and helping participants don their wearable devices. The facilitator assumed the role of a host and started by pouring a beverage into each glass. This action produced a bubbling sound and visual ripples, where the size of the ripples and the depth and intensity of the auditory feedback indicated the quantity of liquid in the glass. The subsequent phase, called

Taste, involved participants wearing the devices that monitored their physical movements while eating and using utensils, such as a fork, to consume cake. Additionally, a video was projected onto each participant’s plate, serving as a `display’ showcasing the incoming food. Lastly, in the third phase, called

Dip, the plate, food, and silverware were removed, leaving only the glass on the table. In this phase, a shared small plate containing chopped bread and dips was placed at the center of the table, with one sound source mapped to this central area. While within the scope of a curated and partially choreographed research study, this design allowed for events to transpire at a natural pace, with space for spontaneous conversation and maintaining continuous engagement.

5.2.3. Data Collection

Semi-structured interviews, participatory observations, surveys, and video recordings were employed in this study. The semi-structured interviews, each lasting approximately 25 minutes, were conducted after the event and were audio-recorded. These interviews aimed to gather qualitative insights that surveys alone may not capture. The interview questions focused on understanding individuals’ lived experiences and obtaining insights into the role of Design Interventions 1 and 2 in a physically co-located social setting. Observers documented direct observations by taking notes, with a specific emphasis on interpersonal improvised behaviors and the corresponding media feedback. To ensure clarity and consistency the observers subsequently shared and reviewed their notes with the research team. The survey questions covered demographic information (age, gender, race) and included space for participants to offer suggestions for improvement on the study design in order to provide feedback to us for the development of the next phase of the study. Participants evaluated their affective experience of the Design Interventions by means of a 5-point Likert scale ranging from "Very pleasant" to "Very Unpleasant." [

37] The video recordings were conducted using two setups: one with an overhead perspective using a webcam, and another with a conventional perspective.

5.2.4. Data Analysis

The interviews, observer notes, and survey responses were coded by the first author. The insights obtained from this coding process were subsequently classified into three categories: the impact on behavioral manifestations, user experience and perception, and suggestions. A comprehensive video analysis was conducted using a human-centric frame-by-frame analysis method. It should be noted that when percentages and discussed below, these are based on the survey responses, and quotations are taking from the interviews or the free-text option given in the survey. The text incorporates timestamps indicating the video analysis position. Our video analysis method, detailed in Study 2, is referenced below. Interviewees are denoted by the identifier P#.

5.3. Results

We sequenced our results in an order that emphasized the fact that these insights primarily rely on video analysis and semi-structured interviews. Additionally, we conducted a non-technological social meal event as a comparative study before the responsive social meal study. This involved typical activities involved in meal preparation and consumption, such as cooking the meal, sipping beverages, tasting food, and incorporating dips. Six participants gathered around a comfortable carpeted area and were provided with utensils and cups with which to begin preparing, consuming, and enjoying their meal together. Key findings from this investigation follow. 1) the role of facilitators proved crucial, as the event would have faced operational challenges without their presence. For instance, the host consistently posed questions to encourage idea sharing within the group. 2) it was evident that participants manifested passive roles during the meal event, such as focusing on food rather than on others. And within this, they, 3) tended to form small discussion groups with nearby individuals. In contrast, the key findings within the study involving the utilization of responsive media indicated that the technological-mediation heightened nonverbal expressions of rapport, directed joint participants’ attention, and fostered group socialization, as discussed in the next.

Theorem 1. Technological mediation fosters active and spontaneous behaviors for enriched nonverbal interactions.

The manipulation of the glass and tabletop surface through media-guided operations encouraged improvised interactions and increased motivation. Participants consciously explored potential interactions with the object itself, exemplified by P1 quickly finishing a drink to observe the visual changes. Additionally, P3 spoke noticeably louder (07:05) to explore voice recognition, immediately attracting others’ attention. Moments of collective play emerged, with four people purposefully and repeatedly toasting back and forth through spontaneous invitations and verbal suggestions (11:40) Furthermore, P4 stated, "I was engaging to find a connection between the two ripples... [I] noticed it changed color; textures grew, and became entangled with other ripples." Without the augmented media interventions, these improvised behaviors may not have emerged within an everyday meal setting. In this study, the improvised behaviors via the responsive media suggested an affective experience, referring to the pleasure of participants’ engagement (50% for Very Pleasant, 37.5% for Pleasant, 12.5% for Neutral), which reflexively contributed to an increased frequency of conversations.

5.3.1. Increasing the Frequency of Conversations

Both the audio-recorded interviews, as well as the video evidence, demonstrate that active involvement through media stimuli significantly influenced conversation frequency and information sharing. For example, P8 shared a personal experience from a previous immersive meal in Shanghai (P8) entitled Dining in the Dark. P5 verbally invited others to collectively engage in similar actions, such as suggesting toasting (P5) and proposing movements such as "how about we move towards the left together." (P5) Participants actively shared their opinion. For instance, P8 mentioned La Petit Chef, an immersive culinary journey with responsive media in the dining space. P4 shared a joke with others, resulting in shared laughter (at 28:00 in the video). This spontaneity led to more frequent and productive conversations. Moreover, during the conversation, participants’ speaking gestures, face expression, mutual eye contact, recurrent head-nodding, and laughter (25:48) contributed to more spontaneous conversation, emerging a relaxed atmosphere.

5.3.2. The Placement of the Projection

Our observers provided valuable insights regarding the project’s placement. As noted by one observer, "the way of looking down and focusing on one’s own plate, which itself is a way of isolation, and divided their attention." Our video analysis (15:10-17:00) confirms this observation. P3 pointed out,"I was interested in looking at the ’video’, while, instead of projecting on the plate, having a shared video displayed in the center of the room could be more fun." P4 noted, "I was wondering if others were seeing a different animation than me. How about different videos on different plates? We can then change positions to see the difference."

5.3.3. The Spatial Arrangement, Setting and Atmosphere

Type of location and the arrangement of space can determine how people act, explore, and feel within a study. The majority of participants mentioned an experience of limited agency within the selected physical setting. P1 stated, "There is no possibility for me to freely move since the individual space is small, and sitting on the chair, and I feel uncomfortable if I make any exaggerated movements." In response, P4 suggested a more open-ended arrangement, proposing, "Could be a cocktail table; we can then more freely move and change positions to engage with the media." Participants also emphasized the importance of paying attention to atmosphere through provisions such as dim-light to light changes(P6) or relaxing music (P8) to accompany the interactive objects. P8 mentioned,"I normally prefer to listen to relaxing music with my friends in a relaxing atmosphere." P7 responded: "How about sensing its different [lighting] due to our mood?"

5.3.4. Engagement with iMSE Over Time

In general, all participants acknowledged the responsive system as an effective icebreaker, but they all pointed out its limitations when considering the goal of creating a playful experience over time. P2 stated, "It drew my motivation at the beginning but felt lost after playing for a while." P7 mentioned, "I can see its meaning of being an ice-breaker for us to socialize, especially at the beginning." One of the observers pointed out that "Sound could be muted in the later session when people are engaged in conversation." On the other hand, participants mentioned improvements that could be considered in the technical realm involving, the refinement of the haptic feedback. P1 expressed, "I fully ignore its existence, especially when I spend a while to understand its buzzing logic." Participants generally expressed the opinion that the inclusion of continuously emerging media stimuli could be a much more effective strategy.

5.4. Second Study: A Open-Ended Social Setting

5.4.1. Objectives

Based on insights from the pilot study, our primary objective in the main study was to establish a free-play space within an open setting that permitted unrestricted movement and minimized physical constraints. We designed an open-ended social play scenario, emphasizing the enhancement of playful engagement rather than solely facilitating icebreaking. Specifically, we implemented a small high-top ’cocktail’ round table setup with a tabletop diameter of 75cm. Participants gathered around this high table in much closer proximity, and the open nature of the setting allowed for freedom in changing positions, moving around, and adjusting physical distance from others.

5.4.2. Study Procedures

As

Figure 9 depicted, Phase 1, known as ice-breaking, aims to stimulate audience curiosity and promote active motor experiences. Interventions 1 and 2–computational objects with visual and sound activities and fluid simulation with mirror display–are implemented during this phase. The design involves mapping sound sources to the standing area, encouraging participants to switch places and move around the table. Visuals of individual motion generation are mirrored, creating a focus, and fostering self-other attention. The transition from ice-breaking to exploration is a process where participants spontaneously engage with each other and make use of media feedback as a cue for continuous exploration.

Before the exploration phase, participants are introduced to the wearable wristbands featuring vibrotactile motors. Intervention 3 (visual-haptic-sound association) is implemented during the exploration phase. As participants coordinate movements and synchronize frequencies, a colorful halo appears on the tabletop surface, accompanied by unique vibrotactile feedback. The transition from exploration to engagement is a continuous, recurrent sensorimotor interaction process where participants develop, evolve and integrate shared and collective objectives. Importantly, this transition is non-linear and bidirectional.

In the engagement stage, participants come to understand the design and interaction possibilities, through purposeful and recurrent movements, and by perceiving an assortment of different vibrotactile feedback, by way of their continuous and emergent social engagement.

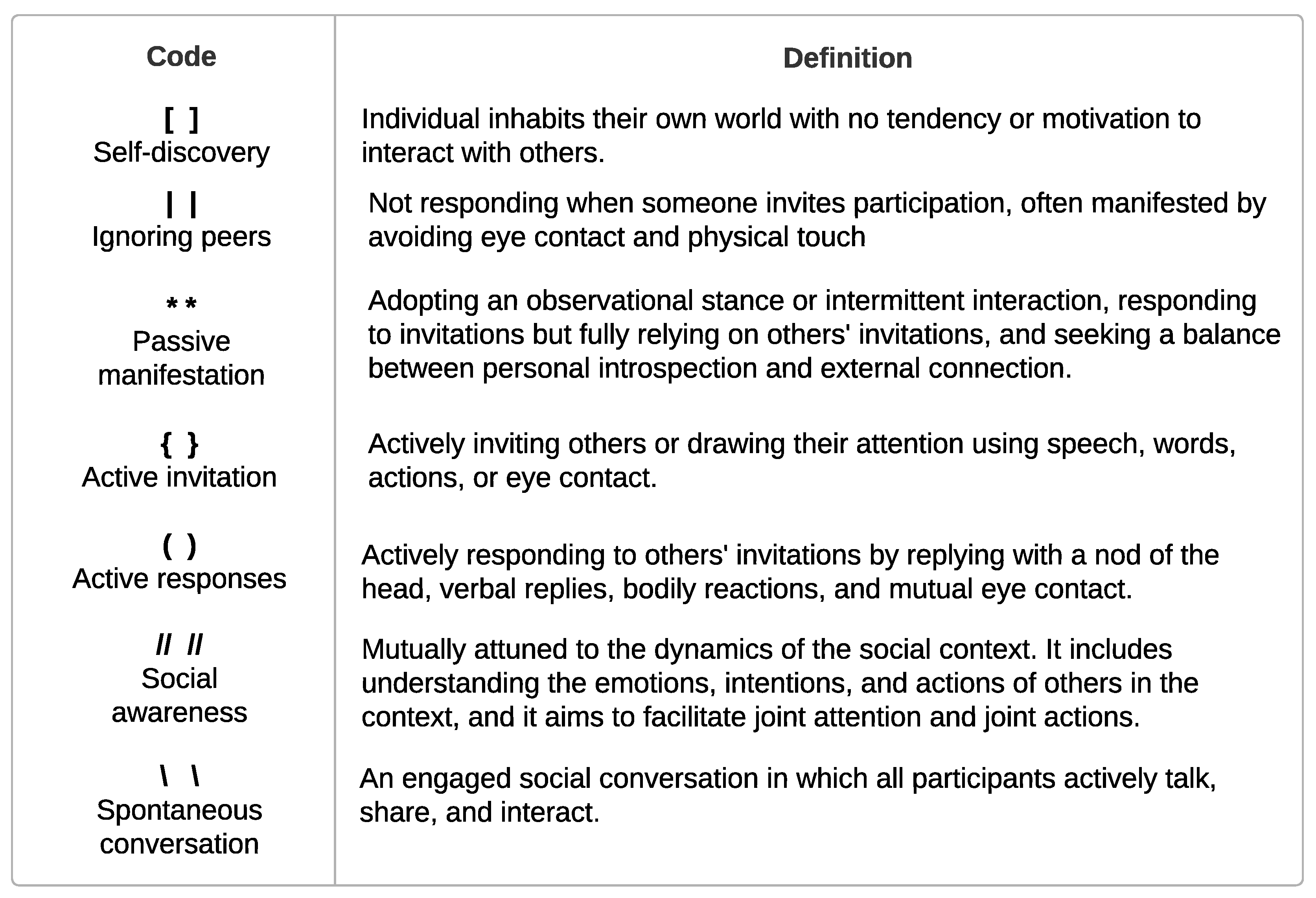

5.4.3. Data Collection and Analysis

Similar to Study 1, the data collection methodology in Study 2 included surveys, semi-structured interviews, observations, and video recordings. We manually transcribed the gathered data onto a Miro board and conducted inductive thematic analysis [

38], with a primary focus on four key aspects:

user experience,

collective engagement,

effectiveness of media design, and

responses to multimodal feedback. Our video analysis method followed three main criteria: firstly, the encoding of social behaviors using different symbols on the video transcript (see

Figure 10); secondly, deriving and encoding social behaviors, marking them with symbols and notes (e.g., noting the duration of such behaviors and adding complementary notes); and finally, noting corresponding media responses as these behaviors occurred. The process initiated with the conversion of the video into a transcript, followed by an analysis of verbal and non-verbal social behaviors, facial expressions, and actions interacting with objects and their responsive media. These behaviors were then systematically categorized into seven subsets, as illustrated in

Figure 10.

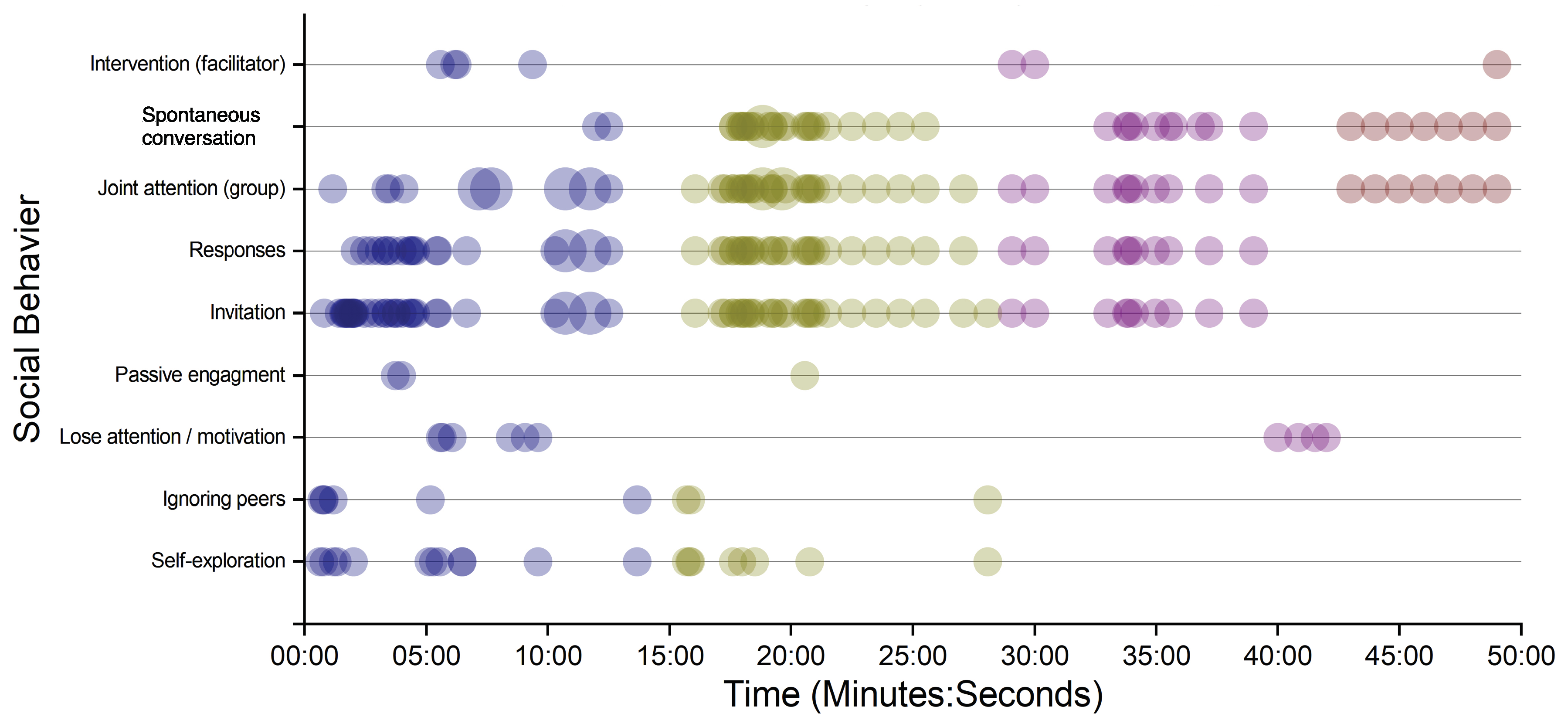

5.5. Results and Discussion

Our visualization (

Figure 11) underscores that all participants exhibited notably more active behaviors, as evidenced by the sparse lines corresponding to signals over time, which is what we would expect given the affordances of the revised design space. Video observations unveiled a progression in participant engagement: starting with a stage of free self-exploration (depicted in phase 1 with a blue dot), participants actively engaged throughout. Subsequently, they demonstrated increased proficiency (phase 2 with a green dot) in understanding the rules and underlying logic, ultimately transitioning into a later stage characterized by collective action-driven play (phase 3 with a purple dot). The size of the dot represents the quantity of corresponding mediated behaviors at a given point in time. Each stage persisted for approximately 15-20 minutes until the facilitator noted a decline in interest. Notably, participants spontaneously engaged in conversation after the third experience, which lasted for about 10 minutes until the facilitator intervened.

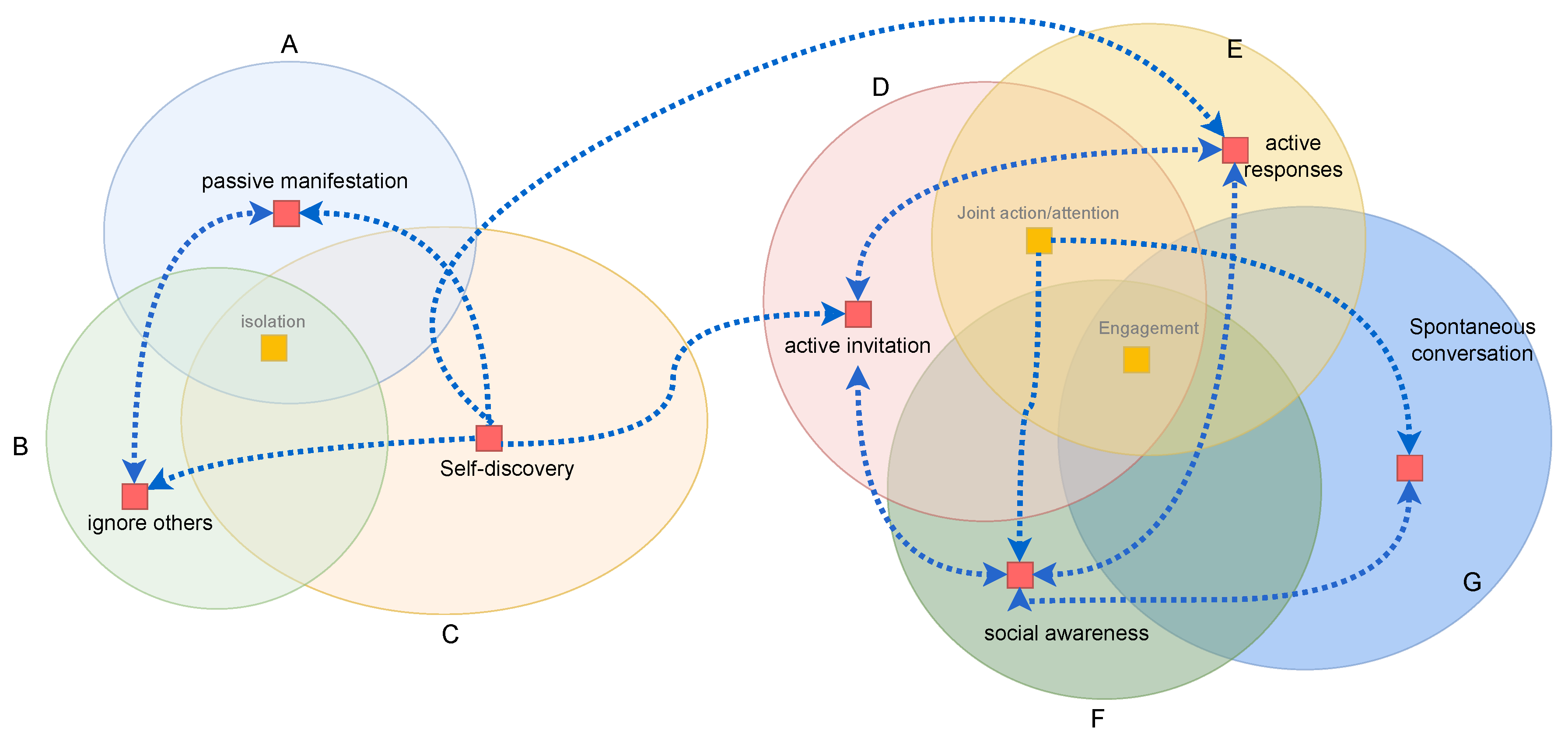

A more intrinsic way to understand the evolution of engagement among the participants is to visualize, from an individual’s perspective, the phase space of possible states of engagement and how they relate. It is important to note that in the setting where people are free to act in more ad hoc ways, the individual’s experience does not simply progress in lock-step along a fixed sequence but can evolve from state to state with certain relative propensities which we summarize in the phase space

Figure 12.

5.5.1. Reflections of Coordination Exploration with Visual-Haptic-Audio Responses

The video elucidates the process by which individuals establish collaborative cognition through haptic and visual stimuli, revealing two periods of participant experience. i) Challenge period: Participants initially grapple with self-exploration, as exemplified by P4’s continuous arm movements with the wearable wristband over the halo (18:15-20:17). P3 mimics P4’s actions, adjusting speed, forms, and orientation (19:25-19:40), P1 and P2 adopt an observational stance. Participants face challenges in collectively integrating an understanding of the responses until the host notes a gradual loss of attention. P3 looks at the host (20:26), and P1 moves out of the play area to test the detection capabilities of the wearable device (23:03); P4 (at 23:41) moved out of the engagement area. The facilitator manually adjusts the threshold value of the covariance coefficient to a lower value in order to let participant more easily perceive the visual halo. ii) Active exploration period: Participants actively engage in prompted and suggested actions, collectively developing an understanding of the connection between media responses and the bodily movement of interactants. Exploration of such interconnection and causality occurs through verbal invitations, eye contact, and the quick establishment of a conversation by sharing findings. Recurrent play through invitation cycles emerges after successfully altering the halo for the first (25:08). For instance, P3 suggests more exploration by verbally inviting others (P1) to shake hands together, and P2 and P4 immediately follow suit. A cross-handshake occurs, and participants engage in altering the halo’s color and diameter together. P4 then suggests everyone hold their neighbors’ hands. Highly-focused engagement through active invitations and responses occurs four times, lasting around 5 minutes over the entire phase. In summary, design featuring size and color changes of the halo offered goal-directed play that demanded high engagement within a collaborative framework. This stands in contrast to Design Intervention 2.

5.5.2. Reflections of Dynamic Social Patterns Exploration with Vibrotactile Response

One of the prevalent themes explored with participants revolved around participant experience, specifically whether they willingly attempted to mediate vibrotactile responses with other participants by experimenting with different movements. P4 provided feedback, stating, "Initially, I perceived the dynamic feedback while remaining still and paying close attention to it. I also engaged in adjusting my own movements to allow others to sense it." Several participants reported heightened awareness of others’ feelings during this experience, leading them to restrict their own movement and focus closely on the sensation and who was moving. For instance, P2 stated, "I actually controlled myself a lot because I was concerned that my movements might disturb others." P3 concurred, stating, "I focused on observing how others were moving and how it affected my sense of tactile feeling. I then tried to respond to them slightly."

Another prominent theme centered on participants’ collaborative engagement. Interviewees shared their understanding and insights in building awareness of collective play, including their perception of vibrotactile distinctions and how they perceived them. The results of our study reveal that a significant majority of participants exhibited a high level of enjoyment in the collaborative-driven experience. Specifically, 62.5% reported being highly engaged, while 25% indicated being very engaged. A smaller percentage, 12.5%, reported moderate engagement, and none expressed slight engagement or none at all. An interviewee metaphorically described the process as a "decoded process:" P1 explained, "It was like a decoded process that greatly stimulated my motivation... I constantly wondered who was performing, what caused it, why it was different, and what else was there." Additionally, P6 (in the second round) emphasized an emotional aspect, stating, "I felt highly engaged when we attempted to move as a team, especially when we collectively discovered the causality through communication and continuous attempts. The collaborative play gave me a sense of quiet pleasure and a feeling of closeness with other members."

Our video analysis supported these findings. During a specific movement phase, P1 suggested taking turns to perform–with the rest remaining still–by verbally requesting it. All participants followed this suggestion. Throughout the process, we observed a significant number of active social signals, such as participants actively sharing their experiences, quickly responding through actions, continuously nodding their heads when receiving an invited signal (e.g., verbal cue), and making direct eye contact as a cue to move together.

According to participants’ survey responses, the majority (n=6) successfully perceived two different vibrotactile feedback modes: the shared haptic feedback (leader-to-perceives mode) and the social mode (when all people moved with a higher similar frequency). However, the aggregated vibration sensation (coordinate mode) was reported to be relatively challenging for the participants to perceive. Participants also suggested that refined haptic patterns or a more diverse vibrotactile feedback should be implemented for improvement.

In terms of participant expectation, participants expressed strong enthusiasm for the prospective use of vibrotactile design in various contexts, including co-play, sensory substitution scenarios, and educational settings such as in children’s social play. As P3 stated, "I felt this is effective in fostering shared attention, bridging social divides, and heightening sensitivity to the emotions of others within a social setting." Participants also recommended refining the haptic patterns for future implementation, suggesting their potential integration as suggestive cueing for collective play (P2), similar to sign language (P4), to facilitate multi-user engagement.

6. Discussion

We summarize results and outline design recommendations for co-located technology, emphasizing principles tailored for researchers using an augmented sensory approach. Starting with a review of the three foundational design frameworks, we provide a concise summary of recommendations. Subsequently, we delve into a comprehensive discussion, elucidating the roles of sensory media in shaping embodied interaction within design practices.

6.1. Design Recommendations

6.1.1. Facilitating Participants’ Attention: Beyond the Media or Computational Object

Augmented multisensensory space incorporating responsive media can immediately capture participants’ attention, particularly when used at the beginning of an intervention. They encourage spontaneous exploratory behavior and contribute to a relaxed atmosphere. However, we note that individuals may become absorbed in prolonged play with media feedback or the object itself. Therefore, it is important to evolve the behavior of the media according to the state of the participants’ activity, redirecting attention from the mesmerizing responsive media to other people.

6.1.2. The Placement of the Projection

Research involving ResEnv predominantly applies projection techniques to surfaces such as the floor or wall [

15,

16,

43] . Our designs 1, 2, and 3, embedding media as diegetic objects requires designers to carefully consider placement’s impact on attention. Media objects, placement and responsive behavior dictates how the groups’ attention is timed and distributed.

Figure 13 visually illustrates the shift from dispersed focus to collective attention. A crucial insight from study 1, particularly in Intervention 1 (with the "past" video on the plate) and Intervention 3 (featuring a concentrated "visual" representation in the center of the table), and Intervention 2 (with the method of

region mapping with sound response) reveals that projection orientation can strongly concentrate or disperse the group’s attention.

Collective attention: everyone focuses on a unified spot

6.1.3. Interaction Over Time

Collective cognition in social interaction evolves over time, ranging from individual self-exploration to spontaneous interpersonal motor interaction. When designing responsive media to augment social interaction, it is important to consider the interweaving of initiation, exploration, and engagement, rather than foregrounding only one aspect from the overall flow. Moreover, Dourish, Varela, Shapiro et al. [

4,

32] have pointed out that cognition emerges through

recurrent and

continuous sensorimotor processes, rather than being instantaneous, disembodied cognitive events. Shared haptic sensation and Design Interventions 1 and 2, acting as a transitional phase seem to help participants integrate their understanding. Design 3 plays a substantial role in the emergence of "collective" play.

6.1.4. Encouraging Multiple Activities Within the Event

Our study featured three phases utilizing different modalities, intending to provide numerous opportunities to shape a rich collective experience, but also avoiding boredom. In interviews, the majority of participants expressed a desire for additional activities or a more diverse experience with sensory responses.

6.2. The Roles of Haptic, Auditory, Visual in Affecting Participant Engagement

6.2.1. Haptic Feedback Provides a Stronger Sense of Group Activity Than Other Modalities

Our findings highlight that the integration of haptic responses, coupled with a thoughtfully designed approach, not only encourages individuals to explore their surroundings but also effectively directs their attention towards others. The incorporation of shared vibrotactile feedback acts as a catalyst for immediate connection and enhances self-other awareness. In contrast to visually-induced interaction, the introduction of shared haptic feedback, driven by peer activities, heightens each participant’s sensitivity to the collective experience. This, in essence, facilitates a seamless non-verbal coordination of attention and intention, leading to a notable increase in social cues, such as mutual eye contact and nuanced emotional expressions. Mutual eye contact has been demonstrated as a powerful facilitator of interpersonal motor resonance and the expression of emotional reciprocity [

46].

6.2.2. Optimal Use of Responsive Sound for Enhanced Social Interaction and Timing Considerations

In the design of sound responses, achieving a balance between natural activation and managing the "off" state (silencing sound synthesis) is crucial. Continuous sound playback during active conversations has the potential to distract individuals from collective experiences, as noted by both participants and observers. We find that an engaged social experience in a co-located setting does not require all media to be active. Mindful use of the "off"state enhances authenticity in social interaction.

6.2.3. Coordination Exploration with Visual-Haptic-(Audio) Responses

Significantly, participants reported a highly enjoyable and satisfying experience with the provision of haptic-visual feedback (85% very satisfied; 10% satisfied; 5% less satisfied). We suggest that designers consider incorporating mechanics based on collective play or "decoded process" into their designs, as these approaches tend to be more captivating. Concerning the "decoded" mechanics, it is essential to note, however, that the time required to overcome challenges may impact motivation, as longer duration could lead to decreased interest. Our studies have shown that facilitators can play a role by offering hints to participants before they lose interest.

7. Limitation and Future Work

We presented several limitations that may have influenced our results: i) Technological advancements:the current wearable wristband solely tracks arm movements. Future work aims to improve this by implementing full-body movement tracking for a more diverse and holistic understanding of collective interaction experiences. ii) Quantity of users in studies: the current sample size is small (n=16 for two settings), necessitating a larger sample for increased statistical significance. iii) Comprehensive consideration in design: co-located social interaction, inherently complex, provides a rich lived experience. Our experimental studies indicate that technologically-supported responsive media, coupled with optimal design methods, is effective in a mixed-gender, multi-race integration setup. However, a comparative study examining outcomes between same-gender and mixed-gender settings in user studies may provide diverse insights. In the future, we plan to extend our research to specific fields, including a group of children [

16], aiming to promote social-emotional learning skills, and for elderly individuals to alleviate isolation.

8. Conclusions

In this paper, we present four interaction designs incorporating augmented media, grounded in three design principles: relational awareness, improvised activity, and interaction over time. Utilizing an iterative research method, we design and develop two social studies with different design interventions. Our findings demonstrate the impact of augmented sensory media on dynamic social cues, influencing bodily engagement, mutual eye contact, proximal sensitivity, and spontaneous conversation. These factors play a crucial role in fostering interpersonal engagement, a sense of togetherness, and cultivating enjoyment. We propose that the insights from this research can be extended to various domains, including VR social interaction, education, entertainment, and situations involving individuals with visual impairments. We assert the value of our approach but acknowledge the need for further exploration in specific contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L.; methodology, Y.L.; software, Y.L.; validation, L.H., X.S.; formal analysis, Y.L.; investigation, Y.L.; resources, L.H, X.S.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, L.H., X.S.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, L.H., X.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Arizona State University (protocol code STUDY00015849, approved on May 21, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

We extend our heartfelt thanks to all the participants for their invaluable feedback and insights, which greatly enriched this work. We also wish to express our gratitude to our colleagues for their thoughtful suggestions and unwavering encouragement throughout the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rogers, Y. Bursting our Digital Bubbles: Life Beyond the App. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Multimodal Interaction; 2014; pp. 1–1. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.-Y.; Smith, B.A.; Vaish, R.; Monroy-Hernández, A. Understanding the role of context in creating enjoyable co-located interactions. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 2022, 6, CSCW1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, M.; Lieschke, J.; Cruwys, T.; Cárdenas, D.; Platow, M.J.; Reynolds, K.J. Better together: How group-based physical activity protects against depression. In Proceedings of the 2021 Social Science &, Medicine Conference, Virtual Event; 2021; p. 114337. [Google Scholar]

- Dourish, P. Where the Action Is; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ringland, K.E.; Zalapa, R.; Neal, M.; Escobedo, L.; Tentori, M.; Hayes, G.R. SensoryPaint: A multimodal sensory intervention for children with neurodevelopmental disorders. In Proceedings of the 2014 ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing, Location of Conference; 2014; pp. 873–884. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, C.; Piqueras-Fiszman, B. The Perfect Meal: The Multisensory Science of Food and Dining; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Bertran, F.A.; ’Oz’Buruk, O.; Espinosa, S.M.; Tanenbaum, T.; Wu, M. Exploring food-based interactive, multi-sensory, and tangible storytelling experiences. In Proceedings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference 2021, Location of Conference; 2021; pp. 651–665. [Google Scholar]

- Kadomura, A.; Tsukada, K.; Siio, I. EducaTableware: Computer-augmented tableware to enhance the eating experiences. In Proceedings of the CHI’13 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Location of Conference; 2013; pp. 3071–3074. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, T.; Jarusriboonchai, P.; Woźniak, P.; Paasovaara, S.; Väätänen, K.; Lucero, A. Technologies for enhancing collocated social interaction: Review of design solutions and approaches. Comput. Support. Coop. Work 2020, 29, 29–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinott, M.; Tractinsky, N. Designing for interpersonal motor synchronization. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2022, 37, 69–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Mechtley, B.; Hayes, L.; Sha, X.W. Tableware: Social coordination through computationally augmented everyday objects using auditory feedback. In Proceedings of the HCI International 2020–Late Breaking Papers: Digital Human Modeling and Ergonomics, Mobility and Intelligent Environments: 22nd HCI International Conference, HCII 2020, Copenhagen, Denmark, 19–24 July 2020; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 332–349. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M. Multi-sensory Environments: A Qualitative Exploration; Master’s Thesis, University Name, Location, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lancioni, G.E.; Cuvo, A.J.; O’Reilly, M.F. Snoezelen: An overview of research with people with developmental disabilities and dementia. Disabil. Rehabil. 2002, 24, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boltong, A.; Keast, R.; Aranda, S. Experiences and consequences of altered taste, flavour and food hedonics during chemotherapy treatment. Support. Care Cancer 2012, 20, 2765–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garzotto, F.; Beccaluva, E.; Gianotti, M.; Riccardi, F. Interactive multisensory environments for primary school children. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA; 2020; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mora-Guiard, J.; Crowell, C.; Pares, N.; Heaton, P. Lands of fog: Helping children with autism in social interaction through a full-body interactive experience. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Interaction Design and Children, Manchester, UK; 2016; pp. 262–274. [Google Scholar]

- Pares, N.; Masri, P.; Van Wolferen, G.; Creed, C. Achieving dialogue with children with severe autism in an adaptive multisensory interaction: The "MEDIATE" project. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2005, 11, 734–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagan, E.; Márquez Segura, E.; Altarriba Bertran, F.; Flores, M.; Mitchell, R.; Isbister, K. Design framework for social wearables. In Proceedings of the 2019 on Designing Interactive Systems Conference, San Diego, CA, USA; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1001–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazzini, M. Poetry Vicenza 2016; ETS: Pisa, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dagan, E.; Márquez Segura, E.; Flores, M.; Isbister, K. ’Not Too Much, Not Too Little’: Wearables for group discussions. In Extended Abstracts of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2018; pp. 1–6.

- Dagan, E.; Márquez Segura, E.; Altarriba Bertran, F.; Flores, M.; Isbister, K. Designing ’True Colors’: A social wearable that affords vulnerability. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2019; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Memarovic, N.; Langheinrich, M.; Alt, F.; Elhart, I.; Hosio, S.; Rubegni, E. Using public displays to stimulate passive engagement, active engagement, and discovery in public spaces. In Proceedings of the 4th Media Architecture Biennale Conference: Participation; 2012; pp. 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Powell, E.; Brinkman, R.; Barnes, T.; Catete, V. Table tilt: making friends fast. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games; 2012; pp. 242–245. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.T.; Wang, C.H.; Chan, L.-W. ShareSpace: Facilitating shared use of the physical space by both VR head-mounted display and external users. In UIST 2018 - Proceedings of the 31st Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Gugenheimer, J.; Stemasov, E.; Frommel, J.; Rukzio, E. ShareVR: Enabling Co-Located Experiences for Virtual Reality between HMD and Non-HMD Users. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2017; pp. 4021–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Y.; Nieto, J. Element: An Ambient Display System for Evoking Self-Reflections and Supporting Social-Interactions in a Workspace. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballendat, T.; Marquardt, N.; Greenberg, S. Proxemic Interaction: Designing for a Proximity and Orientation-Aware Environment. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Interactive Tabletops and Surfaces; 2010; pp. 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J. R.; O’Hagan, J.; Guerra-Gomez, J. A.; Williamson, J. H.; Cesar, P.; Shamma, D. A. Digital Proxemics: Designing Social and Collaborative Interaction in Virtual Environments. In Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2022; Article No. 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E. T. The Hidden Dimension, Volume 609; Anchor: 1966.

- Postma, D.; de Ruiter, A.; Reidsma, D.; Ranasinghe, C. SixFeet: An Interactive, Corona-Safe, Multiplayer Sports Platform. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction, 2022; Article No. 66; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-Y. (Cyn); Smith, B. A.; Vaish, R.; Monroy-Hernández, A. Understanding the Role of Context in Creating Enjoyable Co-Located Interactions. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2022, 6, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, L. Embodied Cognition; New Problems of Philosophy; Taylor & Francis: 2019; ISBN 9781351719162. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?id=ycaWDwAAQBAJ.

- Isbister, K.; Márquez Segura, E.; Kirkpatrick, S.; Chen, X.; Salahuddin, S.; Cao, G.; Tang, R. Yamove! A movement synchrony game that choreographs social interaction. Human Technology 2016, 12, University. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, L.; Loaiza, J. M. Chapter 12 Exploring Attention Through Technologically-Mediated Musical Improvisation: An Enactive-Ecological Perspective. In Access and Mediation: Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Attention; Wehrle, M., D?Angelo, D., Solomonova, E., Eds.; De Gruyter: 2022; pp. 279–298.

- Colombetti, G. The feeling body: Affective science meets the enactive mind. The Feeling Body: Affective Science Meets the Enactive Mind.

- Benzecry, C. E.; Domínguez Rubio, F. The cultural life of objects. In Routledge Handbook of Cultural Sociology; Grindstaff, L.; Lo, M.-C. M.; Hall, J. R., Eds.; Routledge, 2018; Chapter 34.

- Sauro, J.; Lewis, J. R. When designing usability questionnaires, does it hurt to be positive? In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 2215–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isbister, K.; Abe, K. Costumes as game controllers: An exploration of wearables to suit social play. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Tangible, Embedded, and Embodied Interaction; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 691–696. [Google Scholar]

- Isbister, K.; Abe, K.; Karlesky, M. Interdependent Wearables (for Play): A Strong Concept for Design. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 465–471. [Google Scholar]

- Obrist, M.; Gatti, E.; Maggioni, E.; Vi, C.T.; Velasco, C. Multisensory experiences in HCI. IEEE MultiMedia 2017, 24, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, B.; Alves Lino, J.; Simons, J. Alves Lino, J.; Simons, J. A Framework for Responsive Environments. In Ambient Intelligence: 13th European Conference, AmI 2017, Malaga, Spain, 26–28 April 2017; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 263–277. [Google Scholar]

- Pagliano, P. Multisensory Environments; David Fulton Publishers: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, B.; Alves Lino, J.; Simons, J. Alves Lino, J.; Simons, J. A Framework for Responsive Environments. In Ambient Intelligence: 13th European Conference, AmI 2017, Proceedings, Malaga, Spain, 26–28 April 2017; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 263–277. [Google Scholar]

- Alves Lino, J.; Salem, B.; Rauterberg, M. Responsive Environments: User Experiences for Ambient Intelligence. J. Ambient Intell. Smart Environ. 2010, 2, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acampora, G.; Cook, D.J.; Rashidi, P.; Vasilakos, A.V. A Survey on Ambient Intelligence in Healthcare. Proc. IEEE 2013, 101, 2470–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, C. Interaction Design in the Built Environment: Designing for the ’Universal User’. In Universal Design 2016: Learning From the Past, Designing for the Future; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 314–324. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Hu, J.; Funk, M.; Feijs, L. DeLight: Biofeedback through Ambient Light for Stress Intervention and Relaxation Assistance. Pers. Ubiquitous Comput. 2018, 22, 787–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 |

Referred to as Max henceforth. |

Figure 1.

Interaction stages over time and its design consideration uner each stage.

Figure 1.

Interaction stages over time and its design consideration uner each stage.

Figure 2.

The diagram of the system architecture.

Figure 2.

The diagram of the system architecture.

Figure 3.

(left) computational tableware; (center) color changes when two glass close; (right) plate as a menu cueing incoming food.

Figure 3.

(left) computational tableware; (center) color changes when two glass close; (right) plate as a menu cueing incoming food.

Figure 4.

Region mapping involves participants engaging with different acoustic feedback through: A) the action of passing a glass, which occurs in area 5; B) the action of clapping hands, intentionally explored in area 5; C) the action of toasting, observed in the middle area; and D) the mutual action of playing, observed in area 2.

Figure 4.

Region mapping involves participants engaging with different acoustic feedback through: A) the action of passing a glass, which occurs in area 5; B) the action of clapping hands, intentionally explored in area 5; C) the action of toasting, observed in the middle area; and D) the mutual action of playing, observed in area 2.

Figure 5.

Collectively engaging, participants sense multisensory responses. The left side captures an overhead view, projecting halos in synchronized movement. On the right, a side view showcases their commitment to successfully generating both visual halos and haptic feedback simultaneously.

Figure 5.

Collectively engaging, participants sense multisensory responses. The left side captures an overhead view, projecting halos in synchronized movement. On the right, a side view showcases their commitment to successfully generating both visual halos and haptic feedback simultaneously.

Figure 6.

Participants shared their experiences by mutually regulating their movements, verbally communicating, and maintaining direct eye contact. Three types of coordinative modes were designed with three distinct vibrotactile feedback mechanisms

Figure 6.

Participants shared their experiences by mutually regulating their movements, verbally communicating, and maintaining direct eye contact. Three types of coordinative modes were designed with three distinct vibrotactile feedback mechanisms

Figure 7.

The structure of Two Types of User Studies.

Figure 7.

The structure of Two Types of User Studies.

Figure 8.

Social-meal study procedure.

Figure 8.

Social-meal study procedure.

Figure 9.

Open-ended social play procedure.

Figure 9.

Open-ended social play procedure.

Figure 10.

Behavior coding and derived social behaviors into 7 subsets with corresponding description.

Figure 10.

Behavior coding and derived social behaviors into 7 subsets with corresponding description.

Figure 11.

Aggregated behaviour, indexed by wall-clock time, in study 2: open-ended social play.

Figure 11.

Aggregated behaviour, indexed by wall-clock time, in study 2: open-ended social play.

Figure 12.

Phase space of states of an individual’s engagement behavior in study 2: open-ended social play.

Figure 12.

Phase space of states of an individual’s engagement behavior in study 2: open-ended social play.

Figure 13.

The transition from dispersed focus to collectively drawing everyone’s attention to a shared spot using media feedback.

Figure 13.

The transition from dispersed focus to collectively drawing everyone’s attention to a shared spot using media feedback.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).