Submitted:

19 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

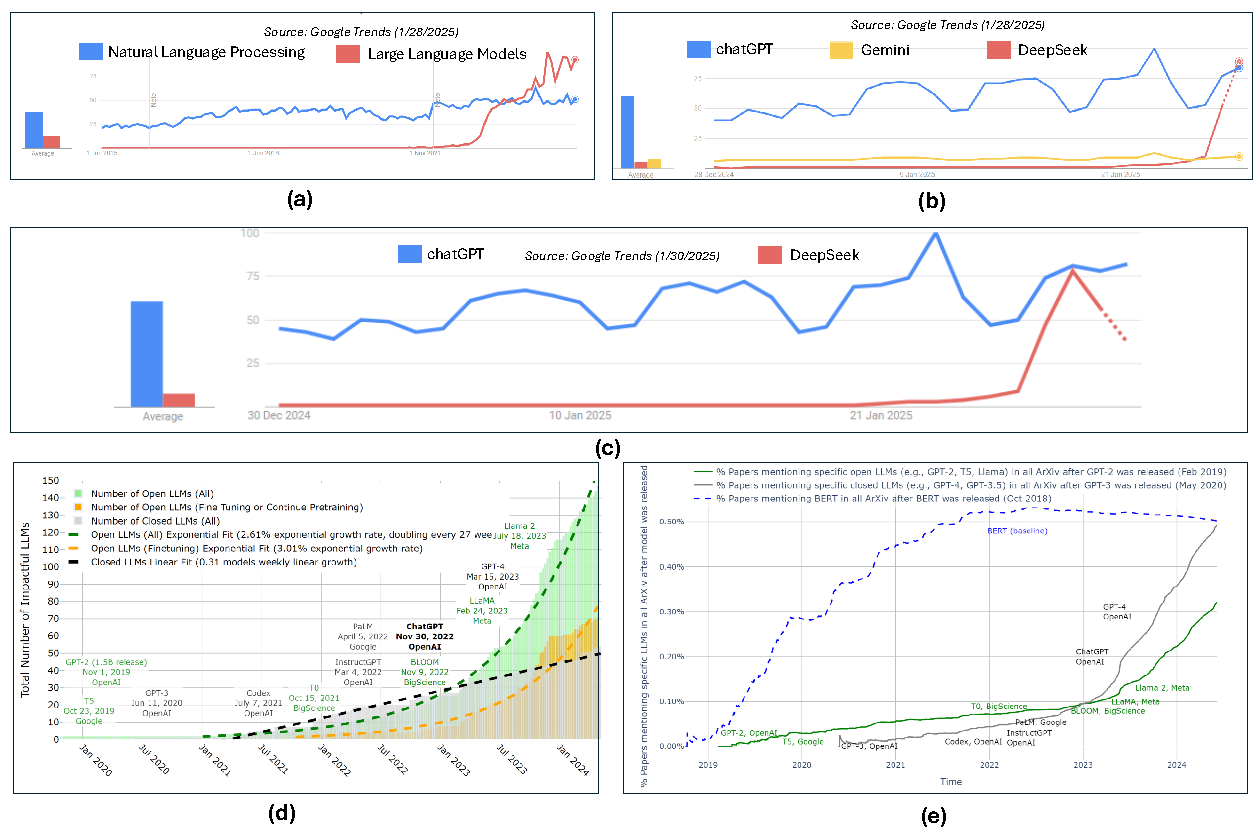

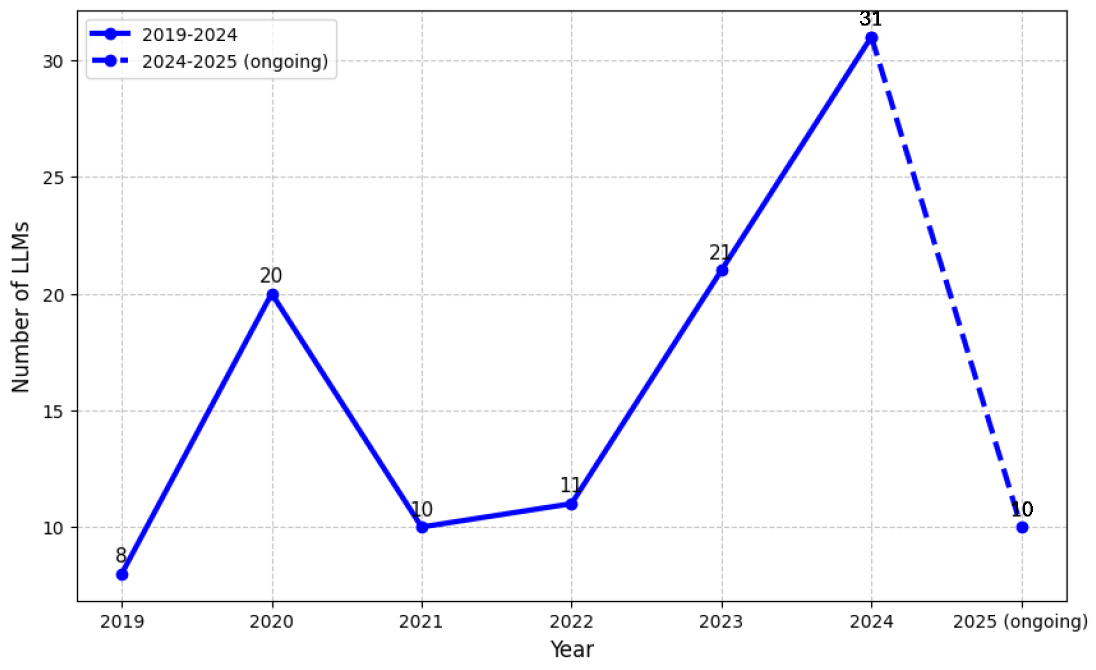

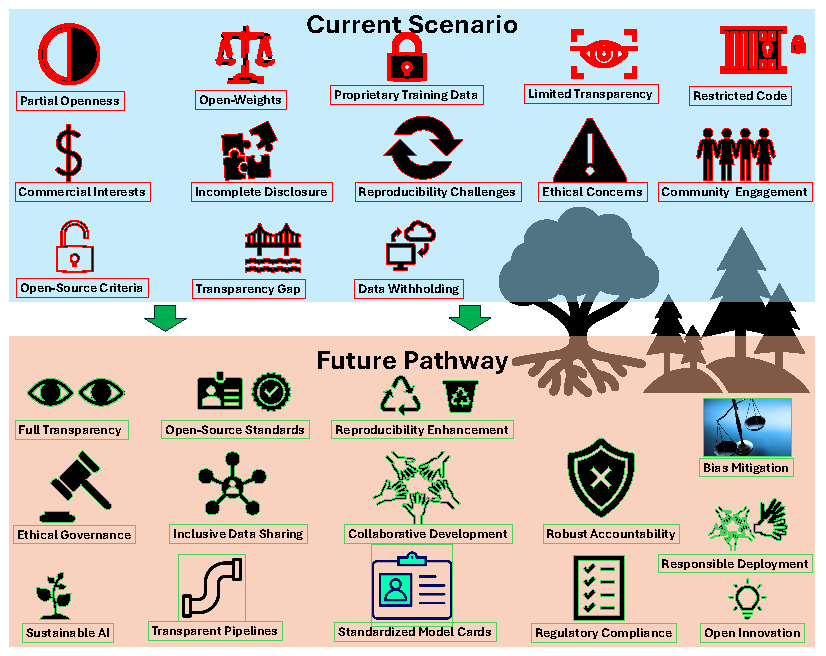

Despite increasing discussions on open-source Artificial Intelligence (AI), existing research lacks a discussion on the transparency and accessibility of state-of-the-art (SoTA) Large Language Models (LLMs). The Open Source Initiative (OSI) has recently released its first formal definition of open-source software. This definition, when combined with standard dictionary definitions and the sparse published literature, provide an initial framework to support broader accessibility to AI models such as LLMs, but more work is essential to capture the unique dynamics of openness in AI. In addition, concerns about open-washing, where models claim openness but lack full transparency, has been raised, which limits the reproducibility, bias mitigation, and domain adaptation of these models. In this context, our study critically analyzes SoTA LLMs from the last five years, including ChatGPT, DeepSeek, LLaMA, Grok, and others, to assess their adherence to transparency standards and the implications of partial openness. Specifically, we examine transparency and accessibility from two perspectives: open-source vs. open-weight models. Our findings reveal that while some models are labeled as open-source, this does not necessarily mean they are fully open-sourced. Even in the best cases, open-source models often do not report model training data, and code as well as key metrics, such as weight accessibility, and carbon emissions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that systematically examines the transparency and accessibility of over 100 different SoTA LLMs through the dual lens of open-source and open-weight models. The findings open avenues for further research and call for responsible and sustainable AI practices to ensure greater transparency, accountability, and ethical deployment of these models.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Aim and Objectives

- Elucidate the terminological ambiguities surrounding "open-source" within the AI domain, specifically distinguishing between truly open-source models and those termed "open-weight" which offer limited transparency.

- Investigate the implications of partial transparency on the reproducibility, community engagement, and ethical dimensions of AI development, emphasizing how these factors influence the practical deployment and trustworthiness of LLMs.

- Propose clearer guidelines and standards to differentiate truly open-source methodologies and models from strategies that merely provide access to pre-trained model weights.

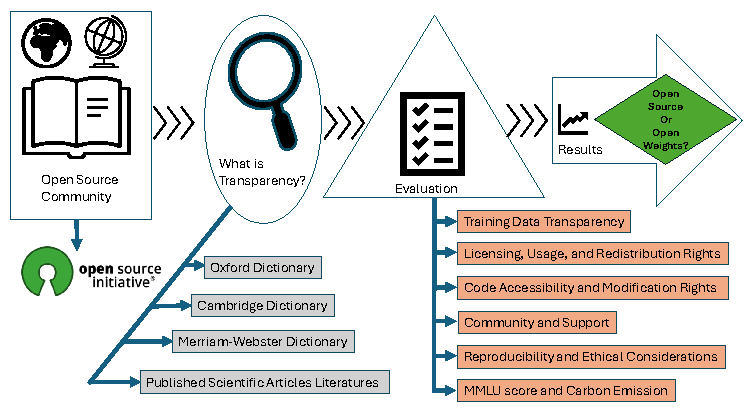

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Criteria for Openness and Transparency

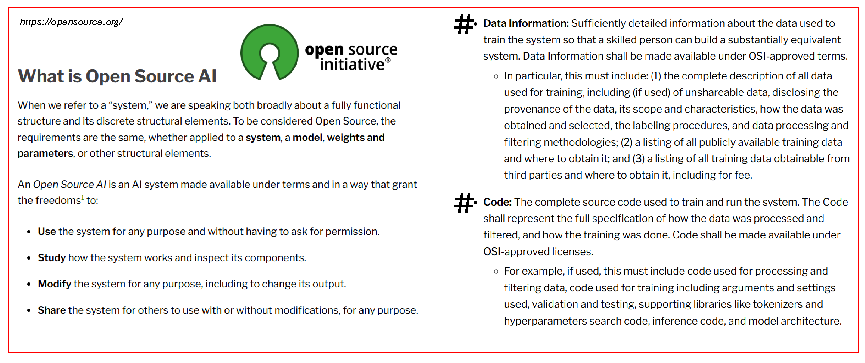

2.2.1. Open Source and Licensing Types

2.2.2. Open Source and Transparency

2.3. Synthesis of Literature

2.3.1. Search Strategy

2.4. Evaluation Framework and Application

- Licensing, Usage, and Redistribution Rights

- Code Accessibility and Modification Rights

- Training Data Transparency

- Community and Support

- MMLU Score and Carbon Emissions

- Ethical Considerations and Reproducibility

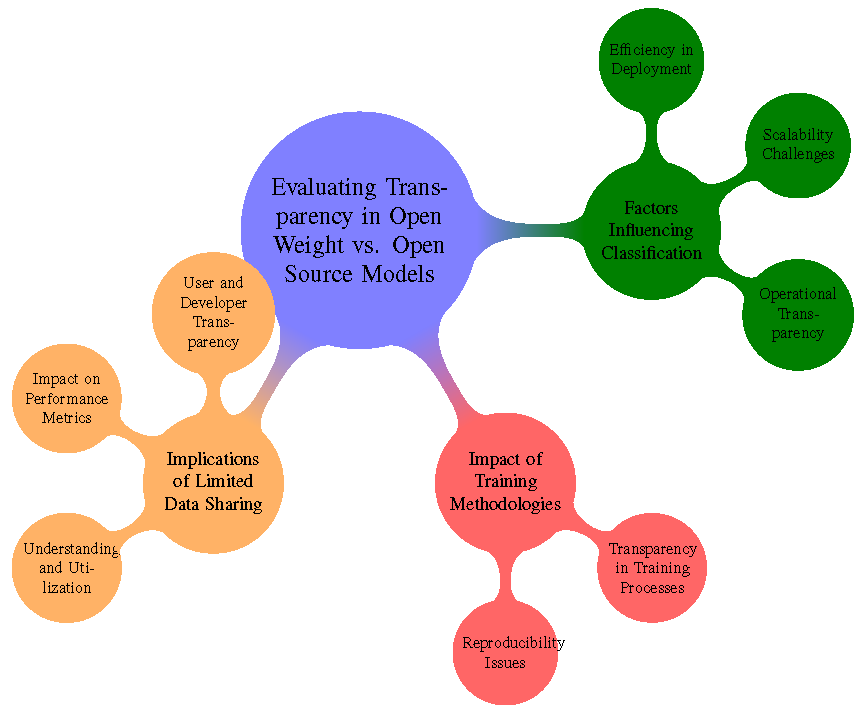

2.5. Research Questions

- What drives the classification of LLMs as open weights rather than open source, and what impact do these factors have on their efficiency and scalability in practical applications?

- How do current training approaches influence transparency and reproducibility, potentially prompting developers to favor open-weight models?

- How does the limited disclosure of training data and methodologies impact both the performance and practical usability of these models, and what future implications arise for developers and end-users?

3. Results

3.1. Overall Findings on Openness and Transparency

3.2. Model-Specific Evaluations

ChatGPT

- GPT-2: [47] adopts an open-weights model under MIT License, providing full access to its 1.5B parameters and architectural details (48 layers, 1600 hidden size). However, the WebText training dataset (8M web pages) lacks comprehensive documentation of sources and filtering protocols. While permitting commercial use and modification, the absence of detailed pre-processing methodologies limits reproducibility of its zero-shot learning capabilities.

- Legacy ChatGPT-3.5:Legacy ChatGPT-3.5 uses proprietary weights with undisclosed architectural details (96 layers, 12288 hidden size). The pre-2021 text/code training data lacks domain distribution metrics and copyright compliance audits. API-only access restricts model introspection or bias mitigation, despite claims of basic translation/text task capabilities [50].

- Default ChatGPT-3.5: Default ChatGPT-3.5 [50] shares Legacy’s proprietary architecture but omits fine-tuning protocols for its "faster, less precise" variant. Training data temporal cutoff (pre-2021) creates recency gaps unaddressed in technical documentation. Restricted API outputs prevent reproducibility of the 69.5% MMLU benchmark results.

- GPT-3.5 Turbo: GPT-3.5 Turbo [50] employs encrypted weights with undisclosed accuracy optimization techniques. The 16K context window expansion lacks computational efficiency metrics or energy consumption disclosures. Proprietary licensing blocks third-party latency benchmarking despite "optimized accuracy" claims.

- GPT-4o: GPT-4o [49] uses multimodal proprietary weights (1.8T parameters) with undisclosed cross-modal fusion logic. Training data (pre-2024 text/image/audio/video) lacks ethical sourcing validations for sensitive content. "System 2 thinking" capabilities lack peer-reviewed validation pipelines.

- GPT-4o mini: GPT-4o mini [49] offers cost-reduced proprietary access (1.2T parameters) with undisclosed pruning methodologies. The pre-2024 training corpus excludes synthetic data ratios and human feedback alignment details. Energy efficiency claims (60% cost reduction) lack independent verification.

DeepSeek

- DeepSeek-R1: DeepSeek-R1’s accessibility is defined by its permissive licensing and efficient deployment capabilities, with quantized variants reducing hardware demands for applications like mathematical reasoning and code generation. However, its reliance on undisclosed training data and proprietary infrastructure optimizations creates dependencies on specialized computational resources, restricting independent assessment for safety or performance validation. The model’s MoE architecture, which reduces energy consumption by 58% compared to dense equivalents [14], challenges conventional scaling paradigms, as evidenced by its disruptive impact on GPU market dynamics [51,52,53,54]. This open-weights approach balances innovation dissemination with commercial secrecy, highlighting unresolved tensions between industry competitiveness and scientific reproducibility in large-language-model development. Full open-source classification would necessitate disclosure of training datasets, fine-tuning codebases, and RLHF implementation details currently withheld.

- DeepSeek LLM :The DeepSeek LLM uses proprietary weights (67B parameters) with undocumented scaling strategies. Books+Wiki data (up to 2023) lacks multilingual token distributions and fact-checking protocols. Custom licensing restricts commercial deployments despite "efficient training" claims [51].

- DeepSeek LLM V2: DeepSeek LLM V2 employs undisclosed MoE architecture (236B params) with proprietary MLA optimizations. The 128K context window lacks attention sparsity patterns and memory footprint metrics. Training efficiency claims ("lowered costs") omit hardware configurations and carbon emission data [52].

- DeepSeek Coder V2: DeepSeek Coder V2 provides API-only access to its 338-language coding model. Training data excludes vulnerability scanning protocols and license compliance audits. Undisclosed reinforcement learning pipelines hinder safety evaluations of generated code [53].

- DeepSeek V3: DeepSeek V3 uses proprietary FP8 training for 671B MoE architecture. The 128K context implementation lacks quantization error analysis and hardware-specific optimizations. Benchmark scores (75.7% MMLU) lack reproducibility scripts or evaluation framework details. [54]

Miscellaneous Proprietary Models

3.3. Synthesis of Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. Trends and Implications in AI Development

4.1.1. Geopolitical and Technological Trends

Economic Impact and Market Trends

Implications for Open Weights and Open Source AI Models

4.2. Discussion on Research Questions

4.3. Sustainability and Ethical Responsibility in AI Development

4.4. Synthesis and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions: Ranjan Sapkota

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 | |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | |

| 11 | |

| 12 | |

| 13 | |

| 14 |

References

- Xu, J.; Ding, Y.; Bu, Y. Position: Open and Closed Large Language Models in Healthcare. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.09906, 2025; arXiv:2501.09906 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cascella, M.; Montomoli, J.; Bellini, V.; Bignami, E. Evaluating the feasibility of ChatGPT in healthcare: an analysis of multiple clinical and research scenarios. Journal of medical systems 2023, 47, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Ding, H.; Chen, H. Large language models in finance: A survey. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the fourth ACM international conference on AI in finance, 2023, pp. 374–382. [CrossRef]

- Neumann, A.T.; Yin, Y.; Sowe, S.; Decker, S.; Jarke, M. An llm-driven chatbot in higher education for databases and information systems. IEEE Transactions on Education 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R. Large language models: from entertainment to solutions. Digital Transformation and Society 2024, 3, 125–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldon, M.N.; Thomas, G.; Skidmore, L. Establishing a Future-Proof Framework for AI Regulation: Balancing Ethics, Transparency, and Innovation. Transactions: The Tennessee Journal of Business Law 2024, 25, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, D.G.; Behrends, J.; Basl, J. What we owe to decision-subjects: beyond transparency and explanation in automated decision-making. Philosophical Studies 2025, 182, 55–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukreja, S.; Kumar, T.; Purohit, A.; Dasgupta, A.; Guha, D. A Literature Survey on Open Source Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Computers in Management and Business, New York, NY, USA, 2024; ICCMB ’24, p. 133–143. [CrossRef]

- Ramlochan, S. Openness in Language Models: Open Source vs Open Weights vs Restricted Weights 2023.

- Walker II, S.M. Best Open Source LLMs of 2024. Klu.ai 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774, 2023; arXiv:2303.08774 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.09288, 2023; arXiv:2307.09288 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Azerbayev, Z.; Schoelkopf, H.; Paster, K.; Santos, M.D.; McAleer, S.; Jiang, A.Q.; Deng, J.; Biderman, S.; Welleck, S. Llemma: An open language model for mathematics. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.10631, 2023; arXiv:2310.10631 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, D.; Yang, D.; Zhang, H.; Song, J.; Zhang, R.; Xu, R.; Zhu, Q.; Ma, S.; Wang, P.; Bi, X.; et al. DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing Reasoning Capability in LLMs via Reinforcement Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.12948, 2025; arXiv:2501.12948 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Promptmetheus. Open-weights Model, 2023.

- Open Source Initiative. Open Source Initiative, 2025. Accessed: February 16, 2025.

- Larsson, S.; Heintz, F. Transparency in artificial intelligence. Internet policy review 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felzmann, H.; Fosch-Villaronga, E.; Lutz, C.; Tamò-Larrieux, A. Towards transparency by design for artificial intelligence. Science and engineering ethics 2020, 26, 3333–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Eschenbach, W.J. Transparency and the black box problem: Why we do not trust AI. Philosophy & Technology 2021, 34, 1607–1622. [Google Scholar]

- Contractor, D.; McDuff, D.; Haines, J.K.; Lee, J.; Hines, C.; Hecht, B.; Vincent, N.; Li, H. Behavioral use licensing for responsible ai. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 2022, pp. 778–788. [CrossRef]

- Quintais, J.P.; De Gregorio, G.; Magalhães, J.C. How platforms govern users’ copyright-protected content: Exploring the power of private ordering and its implications. Computer Law & Security Review 2023, 48, 105792. [Google Scholar]

- of Technology, M.I. MIT License. Accessed: 2025-02-16.

- Apache Software Foundation. Apache License, Version 2.0. Accessed: 2025-02-16.

- Free Software Foundation. GNU General Public License. Accessed: 2025-02-16.

- of the University of California, R. BSD License. Accessed: 2025-02-16.

- Project, B. Creative ML OpenRAIL-M License. Accessed: 2025-02-16.

- Commons, C. Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License. Accessed: 2025-02-16.

- Commons, C. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International Public License. Accessed: 2025-02-16.

- BigScience. BigScience OpenRAIL-M License. Accessed: 2025-02-16.

- Project, B. BigCode Open RAIL-M v1 License. Accessed: 2025-02-16.

- Rosen, L.E. Academic Free License Version 3.0. Accessed: 2025-02-16.

- Boost.org. Boost Software License 1.0. Accessed: 2025-02-16.

- of the University of California, R. BSD 2-Clause "Simplified" License. Accessed: 2025-02-16.

- of the University of California, R. BSD 3-Clause "New" or "Revised" License. Accessed: 2025-02-16.

- Lipton, Z.C. The mythos of model interpretability: In machine learning, the concept of interpretability is both important and slippery. Queue 2018, 16, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi-Velez, F.; Kim, B. Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.08608, 2017; arXiv:1702.08608 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arrieta, A.B.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Del Ser, J.; Bennetot, A.; Tabik, S.; Barbado, A.; García, S.; Gil-López, S.; Molina, D.; Benjamins, R.; et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI. Information fusion 2020, 58, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. " Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, 2016, pp. 1135–1144. [CrossRef]

- Goodman, B.; Flaxman, S. European Union regulations on algorithmic decision-making and a “right to explanation”. AI magazine 2017, 38, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, C. Interpretable machine learning; Lulu. com, 2020.

- Rudin, C.; Chen, C.; Chen, Z.; Huang, H.; Semenova, L.; Zhong, C. Interpretable machine learning: Fundamental principles and 10 grand challenges. Statistic Surveys 2022, 16, 1–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, U.; Xiang, A.; Sharma, S.; Weller, A.; Taly, A.; Jia, Y.; Ghosh, J.; Puri, R.; Moura, J.M.; Eckersley, P. Explainable machine learning in deployment. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2020 conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency, 2020, pp. 648–657. [CrossRef]

- Gilpin, L.H.; Bau, D.; Yuan, B.Z.; Bajwa, A.; Specter, M.; Kagal, L. Explaining explanations: An overview of interpretability of machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 5th International Conference on data science and advanced analytics (DSAA). IEEE; 2018; pp. 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röttger, P.; Pernisi, F.; Vidgen, B.; Hovy, D. Safetyprompts: a systematic review of open datasets for evaluating and improving large language model safety. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.05399, 2024; arXiv:2404.05399 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A. Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, S.; Qureshi, R.; Zahid, A.; Fioresi, J.; Sadak, F.; Saeed, M.; Sapkota, R.; Jain, A.; Zafar, A.; Hassan, M.U.; et al. Who is Responsible? The Data, Models, Users or Regulations? Responsible Generative AI for a Sustainable Future. Authorea Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. 2019; arXiv:cs.CL/1810.04805.

- Hurst, A.; Lerer, A.; Goucher, A.P.; Perelman, A.; Ramesh, A.; Clark, A.; Ostrow, A.; Welihinda, A.; Hayes, A.; Radford, A.; et al. Gpt-4o system card. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.21276, 2024; arXiv:2410.21276 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jaech, A.; Kalai, A.; Lerer, A.; Richardson, A.; El-Kishky, A.; Low, A.; Helyar, A.; Madry, A.; Beutel, A.; Carney, A.; et al. Openai o1 system card. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.16720, 2024; arXiv:2412.16720 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, X.; Chen, D.; Chen, G.; Chen, S.; Dai, D.; Deng, C.; Ding, H.; Dong, K.; Du, Q.; Fu, Z.; et al. Deepseek llm: Scaling open-source language models with longtermism. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.02954, 2024; arXiv:2401.02954 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Feng, B.; Wang, B.; Wang, B.; Liu, B.; Zhao, C.; Dengr, C.; Ruan, C.; Dai, D.; Guo, D.; et al. Deepseek-v2: A strong, economical, and efficient mixture-of-experts language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.04434, 2024; arXiv:2405.04434 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Guo, D.; Shao, Z.; Yang, D.; Wang, P.; Xu, R.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.; Gao, H.; Ma, S.; et al. DeepSeek-Coder-V2: Breaking the Barrier of Closed-Source Models in Code Intelligence. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.11931, 2024; arXiv:2406.11931 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.; Feng, B.; Xue, B.; Wang, B.; Wu, B.; Lu, C.; Zhao, C.; Deng, C.; Zhang, C.; Ruan, C.; et al. Deepseek-v3 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.19437, 2024; arXiv:2412.19437 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Raffel, C.; et al. Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2020, 21, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Mensch, A.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; Casas, D.d.l.; Bressand, F.; Lengyel, G.; Lample, G.; Saulnier, L.; et al. Mistral 7B. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.06825, arXiv:2310.06825 2023.

- McAleese, J.; et al. CriticGPT: Fine-Tuning Language Models for Critique Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.12345, 2024; arXiv:2401.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, A.; et al. HLAT: High-Performance Language Models for Task-Specific Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.12345, 2024; arXiv:2402.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; et al. Multimodal Chain-of-Thought Reasoning for Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.12345, 2023; arXiv:2301.12345 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Soltan, S.; et al. AlexaTM 20B: A Large-Scale Multilingual Language Model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.12345, 2022; arXiv:2204.12345 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Team, C. Chameleon: A Multimodal Language Model for High-Performance Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.12345, 2024; arXiv:2403.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- AI, M. Introducing Llama 3: The Next Generation of Open-Source Language Models, 2024. Accessed: 2025-02-01.

- Zhou, Y.; et al. LIMA: A High-Performance Language Model for Task-Specific Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.12345, 2024; arXiv:2404.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; et al. Improving Conversational AI with BlenderBot 3x. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.12345, 2023; arXiv:2305.12345 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Izacard, G.; et al. Atlas: A High-Performance Language Model for Task-Specific Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.12345, 2023; arXiv:2306.12345 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fried, D.; et al. InCoder: A Generative Model for Code. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.12345, 2022; arXiv:2207.12345 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann, R.; et al. 4M-21: A High-Performance Language Model for Task-Specific Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.12345, 2024; arXiv:2401.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, S.; et al. OpenELM: On-Device Language Models for Efficient Inference. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.12345, 2024; arXiv:2402.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- McKinzie, J.; et al. MM1: A Multimodal Language Model for High-Performance Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.12345, 2024; arXiv:2403.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Moniz, N.; et al. ReALM-3B: A High-Performance Language Model for Task-Specific Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.12345, 2024; arXiv:2404.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- You, C.; et al. Ferret-UI: A Multimodal Language Model for User Interface Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.12345, 2024; arXiv:2405.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; et al. MGIE: Guiding Multimodal Language Models for High-Performance Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.12345, 2023; arXiv:2306.12345 2023. [Google Scholar]

- You, C.; et al. Ferret: A Multimodal Language Model for High-Performance Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.12345, 2023; arXiv:2307.12345 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, J.; et al. Nemotron-4 340B: A High-Performance Language Model for Task-Specific Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.12345, 2024; arXiv:2401.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, A.; et al. VIMA: A Multimodal Language Model for High-Performance Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.12345, 2023; arXiv:2308.12345 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; et al. Retro 48B: A High-Performance Language Model for Task-Specific Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.12345, 2023; arXiv:2309.12345 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; et al. Raven: A High-Performance Language Model for Task-Specific Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.12345, 2023; arXiv:2310.12345 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Reid, J.; et al. Gemini 1.5: A Multimodal Language Model for High-Performance Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.12345, 2024; arXiv:2402.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Saab, K.; et al. Med-Gemini-L 1.0: A Medical-Focused Language Model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.12345, 2024; arXiv:2403.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- De, S.; et al. Griffin: A High-Performance Language Model for Task-Specific Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.12345, 2024; arXiv:2404.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Team, G.; Mesnard, T.; Hardin, C.; Dadashi, R.; Bhupatiraju, S.; Pathak, S.; Sifre, L.; Rivière, M.; Kale, M.S.; Love, J.; et al. Gemma: Open models based on gemini research and technology. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.08295, 2024; arXiv:2403.08295 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; et al. PaLi-3: A Multimodal Language Model for High-Performance Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.12345, 2023; arXiv:2305.12345 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Padalkar, A.; et al. RT-X: A Robotics-Focused Language Model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.12345, 2023; arXiv:2306.12345 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, L.; et al. Med-PaLM M: A Medical-Focused Language Model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.12345, 2024; arXiv:2401.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Team, M. MAI-1: A High-Performance Language Model for Task-Specific Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.12345, 2024; arXiv:2402.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; et al. YOCO: A High-Performance Language Model for Task-Specific Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.12345, 2024; arXiv:2403.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Abdin, M.; et al. Phi-3: A High-Performance Language Model for Task-Specific Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.12345, 2024; arXiv:2404.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Team, F. WizardLM-2-8x22B: A High-Performance Language Model for Task-Specific Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.12345, arXiv:2405.12345 2024.

- Yu, Y.; et al. WaveCoder: A Code-Focused Language Model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.12345, 2023; arXiv:2307.12345 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, A.; et al. OCRA 2: A High-Performance Language Model for Task-Specific Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.12345, 2023; arXiv:2308.12345 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, H.; et al. Florence-2: A Multimodal Language Model for High-Performance Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.12345, 2024; arXiv:2401.12345 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; et al. Qwen: A High-Performance Language Model for Task-Specific Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.12345, 2023; arXiv:2309.12345 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, M.; et al. SeaLLM-13b: A Multilingual Language Model for High-Performance Tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.12345, 2023; arXiv:2310.12345 2023. [Google Scholar]

- xAI. Open Release of Grok-1, 2024. Accessed: 2025-02-09.

- Shoeybi, M.; Patwary, M.; Puri, R.; LeGresley, P.; Casper, J.; Catanzaro, B. Megatron-lm: Training multi-billion parameter language models using model parallelism. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.08053, 2019; arXiv:1909.08053 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.; Patwary, M.; Norick, B.; LeGresley, P.; Rajbhandari, S.; Casper, J.; Liu, Z.; Prabhumoye, S.; Zerveas, G.; Korthikanti, V.; et al. Using deepspeed and megatron to train megatron-turing nlg 530b, a large-scale generative language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.11990, 2022; arXiv:2201.11990 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Keskar, N.S.; McCann, B.; Varshney, L.R.; Xiong, C.; Socher, R. Ctrl: A conditional transformer language model for controllable generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.05858, 2019; arXiv:1909.05858 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z. XLNet: Generalized Autoregressive Pretraining for Language Understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.08237, 2019; arXiv:1906.08237 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.11692 2019, arXiv:1907.11692 2019, 364364. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, K. Electra: Pre-training text encoders as discriminators rather than generators. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.10555, 2020; arXiv:2003.10555 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, Z. Albert: A lite bert for self-supervised learning of language representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.11942, 2019; arXiv:1909.11942 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sanh, V. DistilBERT, a distilled version of BERT: smaller, faster, cheaper and lighter. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.01108, 2019; arXiv:1910.01108 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zaheer, M.; Guruganesh, G.; Dubey, K.A.; Ainslie, J.; Alberti, C.; Ontanon, S.; Pham, P.; Ravula, A.; Wang, Q.; Yang, L.; et al. Big bird: Transformers for longer sequences. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 17283–17297. [Google Scholar]

- Rae, J.W.; Borgeaud, S.; Cai, T.; Millican, K.; Hoffmann, J.; Song, F.; Aslanides, J.; Henderson, S.; Ring, R.; Young, S.; et al. Scaling language models: Methods, analysis & insights from training gopher. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.11446, 2021; arXiv:2112.11446 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, J.; Borgeaud, S.; Mensch, A.; Buchatskaya, E.; Cai, T.; Rutherford, E.; Casas, D.d.L.; Hendricks, L.A.; Welbl, J.; Clark, A.; et al. Training compute-optimal large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.15556, 2022; arXiv:2203.15556 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhery, A.; Narang, S.; Devlin, J.; Bosma, M.; Mishra, G.; Roberts, A.; Barham, P.; Chung, H.W.; Sutton, C.; Gehrmann, S.; et al. Palm: Scaling language modeling with pathways. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2023, 24, 1–113. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Roller, S.; Goyal, N.; Artetxe, M.; Chen, M.; Chen, S.; Dewan, C.; Diab, M.; Li, X.; Lin, X.V.; et al. Opt: Open pre-trained transformer language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.01068, 2022; arXiv:2205.01068 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Workshop, B.; Scao, T.L.; Fan, A.; Akiki, C.; Pavlick, E.; Ilić, S.; Hesslow, D.; Castagné, R.; Luccioni, A.S.; Yvon, F.; et al. Bloom: A 176b-parameter open-access multilingual language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.05100, 2022; arXiv:2211.05100 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, O.; Sharir, O.; Lenz, B.; Shoham, Y. Jurassic-1: Technical details and evaluation. White Paper. AI21 Labs 2021, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Tworek, J.; Jun, H.; Yuan, Q.; Pinto, H.P.D.O.; Kaplan, J.; Edwards, H.; Burda, Y.; Joseph, N.; Brockman, G.; et al. Evaluating large language models trained on code. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.03374, 2021; arXiv:2107.03374 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sanh, V.; Webson, A.; Raffel, C.; Bach, S.H.; Sutawika, L.; Alyafeai, Z.; Chaffin, A.; Stiegler, A.; Scao, T.L.; Raja, A.; et al. Multitask prompted training enables zero-shot task generalization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.08207, 2021; arXiv:2110.08207 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Tay, Y.; Dehghani, M.; Tran, V.Q.; Garcia, X.; Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Chung, H.W.; Shakeri, S.; Bahri, D.; Schuster, T.; et al. Ul2: Unifying language learning paradigms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.05131, 2022; arXiv:2205.05131 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Du, N.; Huang, Y.; Dai, A.M.; Tong, S.; Lepikhin, D.; Xu, Y.; Krikun, M.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, A.W.; Firat, O.; et al. Glam: Efficient scaling of language models with mixture-of-experts. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2022; pp. 5547–5569. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, S.; Feng, S.; Ding, S.; Pang, C.; Shang, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, Y.; et al. Ernie 3.0: Large-scale knowledge enhanced pre-training for language understanding and generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.02137, 2021; arXiv:2107.02137 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Black, S.; Biderman, S.; Hallahan, E.; Anthony, Q.; Gao, L.; Golding, L.; He, H.; Leahy, C.; McDonell, K.; Phang, J.; et al. Gpt-neox-20b: An open-source autoregressive language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.06745, 2022; arXiv:2204.06745 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nijkamp, E.; Pang, B.; Hayashi, H.; Tu, L.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Savarese, S.; Xiong, C. Codegen: An open large language model for code with multi-turn program synthesis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.13474, 2022; arXiv:2203.13474 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H.W.; Hou, L.; Longpre, S.; Zoph, B.; Tay, Y.; Fedus, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Dehghani, M.; Brahma, S.; et al. Scaling instruction-finetuned language models. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2024, 25, 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, L. mt5: A massively multilingual pre-trained text-to-text transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.11934, 2020; arXiv:2010.11934 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kitaev, N. ; Kaiser, .; Levskaya, A. Reformer: The efficient transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.04451, 2020; arXiv:2001.04451 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Beltagy, I.; Peters, M.E.; Cohan, A. Longformer: The long-document transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.05150, 2020; arXiv:2004.05150 2020. [Google Scholar]

- He, P.; Liu, X.; Gao, J.; Chen, W. Deberta: Decoding-enhanced bert with disentangled attention. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.03654, 2020; arXiv:2006.03654 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rosset, C. Turing-NLG: A 17-billion-parameter language model by Microsoft. Microsoft Research https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/blog/turing-nlg-a-17-billion-parameter-language-model-by-microsoft/, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fedus, W.; Zoph, B.; Shazeer, N. Switch transformers: Scaling to trillion parameter models with simple and efficient sparsity. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2022, 23, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jie, T. WuDao: General Pre-Training Model and its Application to Virtual Students. Tsingua University https://keg.cs.tsinghua.edu.cn/jietang/publications/wudao-3.0-meta-en.pdf, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thoppilan, R.; De Freitas, D.; Hall, J.; Shazeer, N.; Kulshreshtha, A.; Cheng, H.T.; Jin, A.; Bos, T.; Baker, L.; Du, Y.; et al. Lamda: Language models for dialog applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.08239, 2022; arXiv:2201.08239 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lepikhin, D.; Lee, H.; Xu, Y.; Chen, D.; Firat, O.; Huang, Y.; Krikun, M.; Shazeer, N.; Chen, Z. Gshard: Scaling giant models with conditional computation and automatic sharding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.16668, 2020; arXiv:2006.16668 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, W.; Yan, Y.; Gong, Y.; Liu, D.; Duan, N.; Chen, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, M. Prophetnet: Predicting future n-gram for sequence-to-sequence pre-training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.04063, 2020; arXiv:2001.04063 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. Dialogpt: Large-Scale generative pre-training for conversational response generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1911.00536, 2019; arXiv:1911.00536 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, M. Bart: Denoising sequence-to-sequence pre-training for natural language generation, translation, and comprehension. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.13461, 2019; arXiv:1910.13461 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Saleh, M.; Liu, P. Pegasus: Pre-training with extracted gap-sentences for abstractive summarization. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2020; pp. 11328–11339. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.; Yang, N.; Wang, W.; Wei, F.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Zhou, M.; Hon, H.W. Unified language model pre-training for natural language understanding and generation. Advances in neural information processing systems 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato, M.; Schaake, M.; Krier, S.; Entsminger, J.; et al. Governing artificial intelligence in the public interest. UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, Working Paper Series (IIPP WP 2022-12). Retrieved April 2022, 2, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Guha, N.; Lawrence, C.M.; Gailmard, L.A.; Rodolfa, K.T.; Surani, F.; Bommasani, R.; Raji, I.D.; Cuéllar, M.F.; Honigsberg, C.; Liang, P.; et al. Ai regulation has its own alignment problem: The technical and institutional feasibility of disclosure, registration, licensing, and auditing. Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 2024, 92, 1473. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. GPT-4 Technical Report, 2023. Available at https://cdn.openai.com/papers/gpt-4.pdf.

- Gallifant, J.; Fiske, A.; Levites Strekalova, Y.A.; Osorio-Valencia, J.S.; Parke, R.; Mwavu, R.; Martinez, N.; Gichoya, J.W.; Ghassemi, M.; Demner-Fushman, D.; et al. Peer review of GPT-4 technical report and systems card. PLOS Digital Health 2024, 3, e0000417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lande, D.; Strashnoy, L. GPT Semantic Networking: A Dream of the Semantic Web–The Time is Now 2023.

- Wolfe, R.; Slaughter, I.; Han, B.; Wen, B.; Yang, Y.; Rosenblatt, L.; Herman, B.; Brown, E.; Qu, Z.; Weber, N.; et al. Laboratory-Scale AI: Open-Weight Models are Competitive with ChatGPT Even in Low-Resource Settings. In Proceedings of the The 2024 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency; 2024; pp. 1199–1210. [Google Scholar]

- Roumeliotis, K.I.; Tselikas, N.D. Chatgpt and open-ai models: A preliminary review. Future Internet 2023, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BigScience Workshop. BLOOM: A 176B-Parameter Open-Access Multilingual Language Model, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Vasić, M.; Petrović, A.; Wang, K.; Nikolić, M.; Singh, R.; Khurshid, S. MoËT: Mixture of Expert Trees and its application to verifiable reinforcement learning. Neural Networks 2022, 151, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudnia, S.; Ebrahimpour, R. Mixture of experts: a literature survey. Artificial Intelligence Review 2014, 42, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, G.; Anil, R.; Borgeaud, S.; Alayrac, J.B.; Yu, J.; Soricut, R.; Schalkwyk, J.; Dai, A.M.; Hauth, A.; Millican, K.; et al. Gemini: a family of highly capable multimodal models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.11805, 2023; arXiv:2312.11805 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Abdin, M.; Aneja, J.; Awadalla, H.; Awadallah, A.; Awan, A.A.; Bach, N.; Bahree, A.; Bakhtiari, A.; Bao, J.; Behl, H.; et al. Phi-3 technical report: A highly capable language model locally on your phone. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.14219, 2024; arXiv:2404.14219 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liesenfeld, A.; Dingemanse, M. Rethinking open source generative AI: open washing and the EU AI Act. In Proceedings of the The 2024 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency; 2024; pp. 1774–1787. [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh, M.; Kubli, M.; Samei, Z.; Dehghani, S.; Zahedivafa, M.; Bermeo, J.D.; Korobeynikova, M.; Gilardi, F. Open-source LLMs for text annotation: a practical guide for model setting and fine-tuning. Journal of Computational Social Science 2025, 8, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbon Credits. How Big is the CO2 Footprint of AI Models? ChatGPT’s Emissions. https://carboncredits.com/how-big-is-the-co2-footprint-of-ai-models-chatgpts-emissions/, 2023. Accessed: [Insert today’s date].

- Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Yang, A.; Fan, A.; et al. The llama 3 herd of models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.21783, 2024; arXiv:2407.21783 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Almazrouei, E.; Alobeidli, H.; Alshamsi, A.; Cappelli, A.; Cojocaru, R.; Debbah, M.; Goffinet, É.; Hesslow, D.; Launay, J.; Malartic, Q.; et al. The falcon series of open language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.16867, 2023; arXiv:2311.16867 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Malartic, Q.; Chowdhury, N.R.; Cojocaru, R.; Farooq, M.; Campesan, G.; Djilali, Y.A.D.; Narayan, S.; Singh, A.; Velikanov, M.; Boussaha, B.E.A.; et al. Falcon2-11b technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.14885, 2024; arXiv:2407.14885 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Caruccio, L.; Cirillo, S.; Polese, G.; Solimando, G.; Sundaramurthy, S.; Tortora, G. Claude 2.0 large language model: Tackling a real-world classification problem with a new iterative prompt engineering approach. Intelligent Systems with Applications 2024, 21, 200336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roziere, B.; Gehring, J.; Gloeckle, F.; Sootla, S.; Gat, I.; Tan, X.E.; Adi, Y.; Liu, J.; Sauvestre, R.; Remez, T.; et al. Code llama: Open foundation models for code. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.12950, 2023; arXiv:2308.12950 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nijkamp, E.; Xie, T.; Hayashi, H.; Pang, B.; Xia, C.; Xing, C.; Vig, J.; Yavuz, S.; Laban, P.; Krause, B.; et al. Xgen-7b technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.03450, 2023; arXiv:2309.03450 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota, R.; Qureshi, R.; Hassan, S.Z.; Shutske, J.; Shoman, M.; Sajjad, M.; Dharejo, F.A.; Paudel, A.; Li, J.; Meng, Z.; et al. Multi-modal LLMs in agriculture: A comprehensive review. Authorea Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota, R.; Meng, Z.; Karkee, M. Synthetic meets authentic: Leveraging llm generated datasets for yolo11 and yolov10-based apple detection through machine vision sensors. Smart Agricultural Technology 2024, 9, 100614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapkota, R.; Paudel, A.; Karkee, M. Zero-shot automatic annotation and instance segmentation using llm-generated datasets: Eliminating field imaging and manual annotation for deep learning model development. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.11285, 2024; arXiv:2411.11285 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sapkota, R.; Raza, S.; Shoman, M.; Paudel, A.; Karkee, M. Image, Text, and Speech Data Augmentation using Multimodal LLMs for Deep Learning: A Survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.18648, 2025; arXiv:2501.18648 2025. [Google Scholar]

| License Type | Copyright Preservation |

Patent Grant | Modification Rights | Distribution Terms | Special Clauses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIT License [22] | Required | No explicit grant | Unlimited modifications | Must include original notices | - |

| Apache License 2.0 [23] | Required | Includes patent rights | Modifications documented | Must include original notices | - |

| GNU GPL 3.0 [24] | Required | - | Derivative works must also be open source | Source code must be disclosed | Strong copyleft |

| BSD License [25] | Required | No explicit grant | Unlimited modifications | No requirement to disclose source | No endorsement |

| Creative ML OpenRAIL-M [26] | Required | - | Ethical use guidelines | Must include original notices | Ethical guidelines |

| CC-BY-4.0 [27] | Credit required | - | Commercial and non-commercial use allowed | Must credit creator | - |

| CC-BY-NC-4.0 [28] | Credit required | - | Only non-commercial use allowed | Must credit creator | Non-commercial use only |

| BigScience OpenRAIL-M [29] | Required | - | Ethical use guidelines | Must include original notices | Ethical guidelines |

| BigCode Open RAIL-M v1 [30] | Required | - | Ethical use guidelines | Must include original notices | Ethical guidelines |

| Academic Free License v3.0 [31] | Required | Includes patent rights | Unlimited modifications | Must include original notices | - |

| Boost Software License 1.0 [32] | Required | No explicit grant | Unlimited modifications | Must include original notices | - |

| BSD 2-clause “Simplified” [33] | Required | No explicit grant | Unlimited modifications | No requirement to disclose source | No endorsement |

| BSD 3-clause “New” or “Revised” [34] | Required | No explicit grant | Unlimited modifications | No requirement to disclose source | No endorsement |

| Author and Reference | Definition |

|---|---|

| Lipton, Z. C. (2018). [35] | “Transparency in machine learning models means understanding how predictions are made, underscored by the availability of training datasets and code, which supports both local and global interpretability.” |

| Doshi-Velez, F., & Kim, B. (2017). [36] | “Transparency in AI refers to the ability to understand and trace the decision-making process, including the availability of training datasets and code. This enhances the clarity of how decisions are made within the model.” |

| Arrieta, A. B., et al. (2020). [37] | “AI transparency means understanding the cause of a decision, supported by the availability of training datasets and code, which fosters trust in the AI’s decision-making process.” |

| Ribeiro, M. T., Singh, S., & Guestrin, C. (2016). [38] | “Transparency in AI models provides insights into model behavior, heavily reliant on the availability of training datasets and code to illuminate how input features influence outputs.” |

| Goodman, B., & Flaxman, S. (2017). [39] | “Transparency involves scrutinizing the algorithms and data used in decisions, emphasizing the availability of training datasets and code to ensure fairness and accountability.” |

| Molnar, C. (2020). [40] | “Transparency in AI refers to clear communication about decision-making processes, facilitated by the availability of training datasets and code, allowing for better understanding of model outputs.” |

| Rudin, et al. (2021). [41] | “Transparency is offering clear, interpretable explanations for decisions, which necessitates the availability of training datasets and code for full interpretability.” |

| Bhatt, et al. (2020). [42] | “Transparency involves making AI’s decision-making process accessible, underlined by the availability of training datasets and code, aligning with ethical standards.” |

| Gilpin, et al. (2021). [43] | “Transparency ensures clear explanations of model behavior, significantly relying on the availability of training datasets and code for technical and operational clarity.” |

| Model, Year and Citation | Training Data | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| 1.GPT-2 (2019) [47] | WebText dataset (8M web pages) | Improved text generation, zero-shot learning |

| 2.Legacy ChatGPT-3.5 (2022) | Text/Code (pre-2021) | Basic text tasks, translation |

| 3.Default ChatGPT-3.5 (2023) | Text/Code (pre-2021) | Faster, less precise |

| 4.GPT-3.5 Turbo (2023) | Text/Code (pre-2021) | Optimized accuracy |

| 5.ChatGPT-4 (2023) | Text/Code (pre-2023) | Multimodal (text), high precision |

| 6.GPT-4o (2024) [49] | Text/Code (pre-2024) | Multimodal (text/image/audio/video) |

| 7.GPT-4o mini (2024) | Text/Code (pre-2024) | Cost-efficient, 60% cheaper |

| 8. o1-preview [50] (2024) | STEM-focused data | System 2 thinking, PhD-level STEM |

| 9. o1-mini (2024) | STEM-focused data | Fast reasoning, 65K tokens output |

| 10. o1 (2025) | General + STEM data | Full o1 reasoning, multimodal |

| 11. o1 pro mode (2025) | General + STEM data | Enhanced compute, Pro-only |

| 12. o3-mini (2025) | General + STEM data | o1-mini successor |

| 13. o3-mini-high (2025) | General + STEM data | High reasoning effort |

| 14. DeepSeek-R1 [14] (2025) | Hybrid dataset of 9.8T tokens from synthetic and organic sources | Mixture of Experts (MoE), enhanced with mathematical reasoning capabilities |

| 15. DeepSeek LLM [51] (2023) | Books+Wiki data up to 2023 | Scaling Language Models |

| 16. DeepSeek LLM V2 [52] (2023) | Highly efficient training | MLA, MoE, Lowered costs |

| 17. DeepSeek Coder V2 [53] (2023) | Supports 338 languages | Enhanced coding capabilities |

| 18. DeepSeek V3 [54] (2023) | Advanced MoE architecture | High-performance, FP8 training |

| 19. BERT-Base [48] (2019) | Books+Wiki data collected up to 2019 | Masked Language Modeling (MLM) |

| 20. BERT-Large [48] (2019) | Books+Wiki data collected up to 2019 | Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) |

| 21. T5-Small [55] (2020) | C4 (Large-scale text dataset) | Text-to-text, encoder-decoder |

| 22. T5-Base [55] (2020) | C4 (Large-scale text dataset) | Text-to-text, scalable, encoder-decoder |

| 23. T5-Large [55] (2020) | C4 (Large-scale text dataset) | Text-to-text, scalable, encoder-decoder |

| 24. T5-3B [55] (2020) | C4 (Large-scale text dataset) | Text-to-text, scalable, encoder-decoder |

| 25. T5-11B [55] (2020) | C4 (Large-scale text dataset) | Text-to-text, scalable, encoder-decoder |

| 26. Mistral 7B [56] (2023) | Compiled from diverse sources totaling 2.4T tokens | Sliding Window Attention (SWA) |

| 27. LLaMA 2 70B [12] (2023) | Diverse corpus aggregated up to 2T tokens | Grouped Query Attention (GQA) |

| 28. CriticGPT [57] (2024) | Human feedback data | Fine-tuned for critique generation |

| 29. Olympus (2024) | 40T tokens | Large-scale, proprietary model |

| 30. HLAT [58] (2024) | Not specified | High-performance, task-specific |

| 31. Multimodal-CoT [59] (2023) | Multimodal datasets | Chain-of-Thought reasoning for multimodal tasks |

| 32. AlexaTM 20B [60] (2022) | Not specified | Multilingual, task-specific |

| 33. Chameleon [61] (2024) | 9.2T tokens | Multimodal, high-performance |

| 34. Llama 3 70B [62] (2024) | 2T tokens | High-performance, open-source |

| 35. LIMA [63] (2024) | Not specified | High-performance, task-specific |

| 36. BlenderBot 3x [64] (2023) | 300B tokens | Conversational AI, improved reasoning |

| 37. Atlas [65] (2023) | 40B tokens | High-performance, task-specific |

| 38. InCoder [66] (2022) | Not specified | Code generation, task-specific |

| 39. 4M-21 [67] (2024) | Not specified | High-performance, task-specific |

| 40. Apple On-Device model [68] (2024) | 1.5T tokens | On-device, task-specific |

| 41. MM1 [69] (2024) | 2.08T tokens | Multimodal, high-performance |

| 42. ReALM-3B [70] (2024) | 134B tokens | High-performance, task-specific |

| 43. Ferret-UI [71] (2024) | 2T tokens | Multimodal, high-performance |

| 44. MGIE [72] (2023) | 2T tokens | Multimodal, high-performance |

| 45. Ferret [73] (2023) | 2T tokens | Multimodal, high-performance |

| 46. Nemotron-4 340B [74] (2024) | 9T tokens | High-performance, task-specific |

| 47. VIMA [75] (2023) | Not specified | Multimodal, high-performance |

| 48. Retro 48B [76] (2023) | 1.2T tokens | High-performance, task-specific |

| 49. Raven [77] (2023) | 40B tokens | High-performance, task-specific |

| 50. Gemini 1.5 [78] (2024) | Not specified | Multimodal, high-performance |

| 51. Med-Gemini-L 1.0 [79] (2024) | 30T tokens | Medical-focused, high-performance |

| 52. Hawk [80] (2024) | 300B tokens | High-performance, task-specific |

| 53. Griffin [80] (2024) | 300B tokens | High-performance, task-specific |

| 54. Gemma [81] (2024) | 6T tokens | High-performance, task-specific |

| 55. Gemini 1.5 Pro [78] (2024) | 30T tokens | Multimodal, high-performance |

| 56. PaLi-3 [82] (2023) | Not specified | Multimodal, high-performance |

| 57. RT-X [83] (2023) | Not specified | Robotics-focused, high-performance |

| 58. Med-PaLM M [84] (2024) | 780B tokens | Medical-focused, high-performance |

| 59. MAI-1 [85] (2024) | 10T tokens | High-performance, task-specific |

| 60. YOCO [86] (2024) | 1.6T tokens | High-performance, task-specific |

| 61. phi-3-medium [87] (2024) | 4.8T tokens | High-performance, task-specific |

| 62. phi-3-mini [87] (2024) | 3.3T tokens | High-performance, task-specific |

| 63. WizardLM-2-8x22B [88] (2024) | Not specified | High-performance, task-specific |

| 64. WaveCoder-Pro-6.7B [89] (2023) | 20B tokens | Code-focused, high-performance |

| 65. WaveCoder-Ultra-6.7B [89] (2023) | 20B tokens | Code-focused, high-performance |

| 66. WaveCoder-SC-15B [89] (2023) | 20B tokens | Code-focused, high-performance |

| 67. OCRA 2 [90] (2023) | Not specified | High-performance, task-specific |

| 68. Florence-2 [91] (2024) | 5.4B visual annotations | Multimodal, high-performance |

| 69. Qwen [92] (2023) | 3T tokens | High-performance, task-specific |

| 70. SeaLLM-13b [93] (2023) | 2T tokens | Multilingual, high-performance |

| 71. Grok-1 [94] (2024) | 13.2T tokens | Incorporates humor-enhancing algorithms |

| 72. Phi-4 [87] (2024) | 9.8T tokens | Optimized for STEM applications |

| 73. Megatron-LM [95] (2020) | Common Crawl, Wikipedia, Books | Large-scale parallel training, optimized for NVIDIA GPUs |

| 74. Turing-NLG [96] (2020) | Diverse web text | High-quality text generation, used in Microsoft products |

| 75. CTRL [97] (2019) | Diverse web text with control codes | Controlled text generation using control codes |

| 76. XLNet [98] (2019) | BooksCorpus, Wikipedia, Giga5, ClueWeb | Permutation-based training, outperforms BERT on many benchmarks |

| 77. RoBERTa [99] (2019) | BooksCorpus, Wikipedia, CC-News, OpenWebText | Improved BERT with better pretraining techniques |

| 78. ELECTRA [100] (2020) | BooksCorpus, Wikipedia | Replaces masked language modeling with a more efficient discriminative task |

| 79. ALBERT [101] (2019) | BooksCorpus, Wikipedia | Parameter reduction techniques for efficient training |

| 80. DistilBERT [102] (2019) | BooksCorpus, Wikipedia | Distilled version of BERT, smaller and faster |

| 81. BigBird [103] (2020) | BooksCorpus, Wikipedia, PG-19 | Sparse attention mechanism for handling long sequences |

| 82. Gopher [104] (2021) | MassiveText dataset (2.5T tokens) | Focused on scaling laws and model performance |

| 83. Chinchilla [105] (2022) | MassiveText dataset (1.4T tokens) | Optimized for compute-efficient training |

| 84. PaLM [106] (2022) | Diverse web text, books, code | Pathways system for efficient training, multilingual support |

| 85. OPT [107] (2022) | Diverse web text | Open-source alternative to GPT-3 |

| 86. BLOOM [108] (2022) | ROOTS corpus (1.6T tokens) | Multilingual, open-source, collaborative effort |

| 87. Jurassic-1 [109] (2021) | Diverse web text | High-quality text generation, API-based access |

| 88. Codex [110] (2021) | Code repositories (e.g., GitHub) | Specialized in code generation and understanding |

| 89. T0 [111] (2021) | Diverse NLP datasets | Zero-shot task generalization |

| 90. UL2 [112] (2022) | Diverse web text | Unified pretraining for diverse NLP tasks |

| 91. GLaM [113] (2021) | Diverse web text | Sparse mixture of experts (MoE) architecture |

| 92. ERNIE 3.0 [114] (2021) | Chinese and English text | Knowledge-enhanced pretraining |

| 93. GPT-NeoX [115] (2022) | The Pile (825GB dataset) | Open-source, large-scale, efficient training |

| 94. CodeGen [116] (2022) | Code repositories (e.g., GitHub) | Specialized in code generation |

| 95. FLAN-T5 [117] (2022) | Diverse NLP datasets | Instruction fine-tuning for better generalization |

| 96. mT5 [118] (2020) | mC4 dataset (101 languages) | Multilingual text-to-text transfer |

| 97. Reformer [119] (2020) | Diverse web text | Efficient attention mechanism for long sequences |

| 98. Longformer [120] (2020) | BooksCorpus, Wikipedia | Efficient attention for long documents |

| 99. DeBERTa [121] (2021) | BooksCorpus, Wikipedia | Disentangled attention mechanism |

| 100. T-NLG [122] (2020) | Diverse web text | High-quality text generation |

| 101. Switch Transformer [123] (2021) | Diverse web text | Sparse mixture of experts (MoE) |

| 102. WuDao 2.0 [124] (2021) | Chinese and English text | Largest Chinese language model |

| 103. LaMDA [125] (2021) | Diverse dialogue data | Specialized in conversational AI |

| 104. MT-NLG [96] (2021) | Diverse web text | High-quality text generation |

| 105. GShard [126] (2020) | Diverse web text | Sparse mixture of experts (MoE) |

| 106. T5-XXL [55] (2020) | C4 dataset | Large-scale text-to-text transfer |

| 107. ProphetNet [127] (2020) | BooksCorpus, Wikipedia | Future token prediction for better sequence modeling |

| 108. DialoGPT [128] (2020) | Reddit dialogue data | Specialized in conversational AI |

| 109. BART [129] (2020) | BooksCorpus, Wikipedia | Denoising autoencoder for text generation |

| 110. PEGASUS [130] (2020) | C4 dataset | Pre-training with gap-sentences for summarization |

| 111. UniLM [131] (2020) | BooksCorpus, Wikipedia | Unified pre-training for NLU and NLG tasks |

| 112. Grok 3 (2025) | Synthetic Data | trained with ten times more computing power than its predecessor, Grok 2 |

| No. | Model | License | Weights | Layers | Hidden | Heads | Params | Context | MMLU score | Carbon Emitted (tCO2eq) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GPT-2 [47] | MIT | 48 | 1600 | 25 | 1.5B | 1024 | N/A | ✗ | |

| 2 | Legacy ChatGPT-3.5 | Proprietary | No | 96 | 12288 | 96 | 175B | 4K | 70.0% | x (not reported) |

| 3 | Default ChatGPT-3.5 | Proprietary | No | 96 | 12288 | 96 | 175B | 4K | 69.5% | 552 |

| 4 | GPT-3.5 Turbo | Proprietary | No | 96 | 12288 | 96 | 175B | 16K | 71.2% | 552 |

| 5 | ChatGPT-4 | Proprietary | No | 96 | 12288 | 96 | 1.8T | 8K | 86.4% | 552 |

| 6 | GPT-4o [49] | Proprietary | No | 96 | 12288 | 96 | 1.8T | 128K | 88.9% | 1,035 |

| 7 | GPT-4o mini | Proprietary | No | 96 | 12288 | 96 | 1.2T | 128K | 82.0% | ✗ |

| 8 | o1-preview [50] | Proprietary | No | 128 | 16384 | 128 | 2T | 128K | 91.3% | ✗ |

| 9 | o1-mini | Proprietary | No | 128 | 16384 | 128 | 1.5T | 65K | 89.5% | ✗ |

| 10 | o1 | Proprietary | No | 128 | 16384 | 128 | 2.5T | 128K | 92.7% | ✗ |

| 11 | o1 pro mode | Proprietary | No | 128 | 16384 | 128 | 3T | 128K | 94.0% | ✗ |

| 12 | o3-mini | Proprietary | No | 128 | 16384 | 128 | 1.8T | 128K | 90.1% | ✗ |

| 13 | o3-mini-high | Proprietary | No | 128 | 16384 | 128 | 1.8T | 128K | 91.5% | ✗ |

| 14 | DeepSeek-R1 [14] | Apache 2.0 | 64 | 8192 | 64/8 | 671B | 128K | 90.8% | 44 | |

| 15 | DeepSeek LLM [51] | Proprietary | 24 | 2048 | 16 | 67B | 2048 | N/A | 44 | |

| 16 | DeepSeek LLM V2 [52] | Proprietary | No | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 236B | 128K | 78.5% | ✗ |

| 17 | DeepSeek Coder V2 [53] | Proprietary | No | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 236B | 128K | 79.2% | ✗ |

| 18 | DeepSeek V3 [54] | Proprietary | No | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 671B | 128K | 75.7% | ✗ |

| 19 | BERT-Base [48] | Apache 2.0 | 12 | 768 | 12 | 110M | 512 | 67.2% | 0.652 | |

| 20 | BERT-Large [48] | Apache 2.0 | 24 | 1024 | 16 | 340M | 512 | 69.3% | 0.652 | |

| 21 | T5-Small [55] | Apache 2.0 | Yes | 6/6 | 512 | 8 | 60M | 512 | ✗ | ✗ |

| 22 | T5-Base [55] | Apache 2.0 | Yes | 12/12 | 768 | 12 | 220M | 512 | 35.9% | ✗ |

| 23 | T5-Large [55] | Apache 2.0 | Yes | 24/24 | 1024 | 16 | 770M | 512 | 40% | ✗ |

| 24 | T5-3B [55] | Apache 2.0 | Yes | 24/24 | 1024 | 32 | 3B | 512 | ✗ | ✗ |

| 25 | T5-11B [55] | Apache 2.0 | Yes | 24/24 | 1024 | 128 | 11B | 512 | 48.6% | T5-11B |

| 26 | Mistral 7B [56] | Apache 2.0 | 32 | 4096 | 32 | 7.3B | 8K | 62.5% | ✗ | |

| 27 | LLaMA 2 70B [12] | Llama 2 | 80 | 8192 | 64 | 65.2B | 4K | 68.9% | 291.42 | |

| 28 | CriticGPT [57] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | ✗ | 552 |

| 29 | Olympus | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 2000B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 30 | HLAT [58] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 7B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 31 | Multimodal-CoT [59] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 32 | AlexaTM 20B [60] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 20B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 33 | Chameleon [61] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 34B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 34 | Llama 3 70B [62] | Llama 3 | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 70B | Not specified | 82.0% | 1900 | |

| 35 | LIMA [63] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 65B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 36 | BlenderBot 3x [64] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 150B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 37 | Atlas [65] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 11B | Not specified | 47.9% | ✗ |

| 38 | InCoder [66] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 6.7B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 39 | 4M-21 [67] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 3B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 40 | Apple On-Device model [68] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 3.04B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 41 | MM1 [69] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 30B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 42 | ReALM-3B [70] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 3B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 43 | Ferret-UI [71] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 13B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 44 | MGIE [72] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 7B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 45 | Ferret [73] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 13B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 46 | Nemotron-4 340B [74] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 340B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 47 | VIMA [75] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 0.2B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 48 | Retro 48B [76] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 48B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 49 | Raven [77] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 11B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 50 | Gemini 1.5 [78] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 90% | ✗ |

| 51 | Med-Gemini-L 1.0 [79] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 1500B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 52 | Hawk [80] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 7B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 53 | Griffin [80] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 14B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 54 | Gemma [81] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 7B | Not specified | 64.3% | ✗ |

| 55 | Gemini 1.5 Pro [78] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 1500B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 56 | PaLi-3 [82] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 6B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 57 | RT-X [83] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 55B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 58 | Med-PaLM M [84] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 540B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 59 | MAI-1 [85] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 500B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 60 | YOCO [86] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 3B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 61 | phi-3-medium [87] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 14B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 62 | phi-3-mini [87] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 3.8B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 63 | WizardLM-2-8x22B [88] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 141B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 64 | WaveCoder-Pro-6.7B [89] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 6.7B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 65 | WaveCoder-Ultra-6.7B [89] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 6.7B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 66 | WaveCoder-SC-15B [89] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 15B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 67 | OCRA 2 [90] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 7B, 13B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 68 | Florence-2 [91] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 69 | Qwen [92] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 72B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 70 | SeaLLM-13b [93] | Proprietary | × | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 13B | Not specified | ✗ | ✗ |

| 71 | Grok-1 [94] | Apache 2.0 | 64 | 6144 | 48/8 | 314B | 8K | N/A | x | |

| 72 | Phi-4 [87] | MIT | 48 | 3072 | 32 | 14B | 16K | 71.2% | x | |

| 73 | Megatron-LM [95] | Custom | No | 72 | 3072 | 32 | 8.3B | 2048 | ✗ | ✗ |

| 74 | Turing-NLG [96] | Proprietary | No | 78 | 4256 | 28 | 17B | 1024 | ✗ | ✗ |

| 75 | CTRL(Conditional Transformer Language Model) [97] | Apache 2.0 | 48 | 1280 | 16 | 1.6B | 256 | ✗ | ✗ | |

| 76 | XLNet [98] | Apache 2.0 | 24 | 1024 | 16 | 340M (Base), 1.5B (Large) | 512 | ✗ | 0.652 | |

| 77 | RoBERTa [99] | MIT | 24 | 1024 | 16 | 355M | 512 | ✗ | ✗ | |

| 78 | ELECTRA [100] | Apache 2.0 | 12 (Base), 24 (Large) | 768 (Base), 1024 (Large) | 12 (Base), 16 (Large) | 110M (Base), 335M (Large) | 512 | ✗ | 0.652 | |

| 79 | ALBERT (A Lite BERT) [101] | Apache 2.0 | 12 (Base), 24 (Large) | 768 (Base), 1024 (Large) | 12 (Base), 16 (Large) | 12M (Base), 18M (Large) | 512 | ✗ | 0.652 | |

| 80 | DistilBERT [102] | Apache 2.0 | 6 | 768 | 12 | 66M | 512 | ✗ | 0.652 | |

| 81 | BigBird [103] | Apache 2.0 | 12 (Base), 24 (Large) | 768 (Base), 1024 (Large) | 12 (Base), 16 (Large) | 110M (Base), 340M (Large) | 4096 | ✗ | ✗ | |

| 82 | Gopher [104] | Proprietary | No | 80 | 8192 | 128 | 280B | 2048 | 60% | ✗ |

| 83 | Chinchilla [105] | Proprietary | No | 80 | 8192 | 128 | 70B | 2048 | ✗ | ✗ |

| 84 | PaLM [106] | Proprietary | No | 118 | 18432 | 128 | 540B | 8192 | 69.3% | ✗ |

| 85 | OPT (Open Pretrained Transformer) [107] | Non-commercial | 96 | 12288 | 96 | 175B | 2048 | ✗ | ✗ | |

| 86 | BLOOM [108] | Responsible AI License | 70 | 14336 | 112 | 176B | 2048 | 90% | ✗ | |

| 87 | Jurassic-1 [109] | Proprietary | No | 76 | 12288 | 96 | 178B | 2048 | 67.5 | ✗ |

| 88 | Codex [110] | Proprietary | No | 96 | 12288 | 96 | 12B | 4096 | ✗ | ✗ |

| 89 | T0 (T5 for Zero-Shot Tasks) [111] | Apache 2.0 | 24 | 1024 | 16 | 11B | 512 | ✗ | ✗ | |

| 90 | UL2 (Unifying Language Learning Paradigms) [112] | Apache 2.0 | 32 | 4096 | 32 | 20B | 2048 | ✗ | ✗ | |

| 91 | GLaM (Generalist Language Model) [113] | Proprietary | No | 64 | 8192 | 128 | 1.2T (sparse) | 2048 | ✗ | ✗ |

| 92 | ERNIE 3.0 [114] | Proprietary | No | 48 | 4096 | 64 | 10B | 512 | ✗ | ✗ |

| 93 | GPT-NeoX [115] | Apache 2.0 | 44 | 6144 | 64 | 20B | 2048 | 33.6 | ✗ | |

| 94 | CodeGen [116] | Apache 2.0 | 32 | 4096 | 32 | 16B | 2048 | ✗ | ✗ | |

| 95 | FLAN-T5 [117] | Apache 2.0 | 24 | 1024 | 16 | 11B | 512 | 52.5 | 552 | |

| 96 | mT5 (Multilingual T5) [118] | Apache 2.0 | 24 | 1024 | 16 | 13B | 512 | 52.4 | 552 | |

| 97 | Reformer [119] | Apache 2.0 | 12 | 768 | 12 | 150M | 64K | ✗ | 552 | |

| 98 | Longformer [120] | Apache 2.0 | 12 | 768 | 12 | 150M | 4096 | ✗ | 552 | |

| 99 | DeBERTa [121] | MIT | 12 | 768 | 12 | 1.5B | 512 | ✗ | 552 | |

| 100 | T-NLG (Turing Natural Language Generation) [122] | Proprietary | No | 78 | 4256 | 28 | 17B | 1024 | ✗ | ✗ |

| 101 | Switch Transformer [123] | Apache 2.0 | 24 | 4096 | 32 | 1.6T (sparse) | 2048 | ✗ | ✗ | |

| 102 | WuDao 2.0 [124] | Proprietary | No | 128 | 12288 | 96 | 1.75T | 2048 | 86.4% | ✗ |

| 103 | LaMDA [125] | Proprietary | No | 64 | 8192 | 128 | 137B | 2048 | 86% | 552 |

| 104 | MT-NLG [96] | Proprietary | No | 105 | 20480 | 128 | 530B | 2048 | 67.5% | 284 |

| 105 | GShard [126] | Proprietary | No | 64 | 8192 | 128 | 600B | 2048 | ✗ | 4.3% |

| 106 | T5-XXL [55] | Apache 2.0 | 24 | 1024 | 16 | 11B | 512 | 48.6% | ✗ | |

| 107 | ProphetNet [127] | MIT | 12 | 768 | 12 | 300M | 512 | ✗ | ✗ | |

| 108 | DialoGPT [128] | MIT | 24 | 1024 | 16 | 345M | 1024 | 25.81% | 552 | |

| 109 | BART [129] | MIT | 12 | 1024 | 16 | 406M | 1024 | ✗ | ✗ | |

| 110 | PEGASUS [130] | Apache 2.0 | 16 | 1024 | 16 | 568M | 512 | ✗ | ✗ | |

| 111 | UniLM [131] | MIT | 12 | 768 | 12 | 340M | 512 | ✗ | ✗ |

| Model | Carbon Emissions (Metric Tons CO2) during Pre-training | Equivalent Number of Trees |

|---|---|---|

| GPT-3 [47] | 552 | 25,091 |

| LLaMA 2 70B [12] 11 | 291.42 | 13,247 |

| Llama 3.1 70B [147] 12 | 2040 | 92,727 |

| Llama 3.2 1B [147] | 71 | 3,227 |

| Llama 3.2 3B [147] | 133 | 6,045 |

| BERT-Large [48] | 0.652 | 30 |

| GPT-4 [134] | 1,200 | 54,545 |

| Falcon-40B [148,149] | 150 | 6,818 |

| Falcon-7B [148,149] | 7 | 318 |

| Mistral 7B [148] | 5 | 227 |

| Mistral 13B [75] | 10 | 455 |

| Anthropic Claude 2 [106,150] | 300 | 13,636 |

| Code Llama [151] | 10 | 455 |

| XGen 7B [152] | 8 | 364 |

| Cohere Command R 11B 13 | 80 | 3,636 |

| Cerebras-GPT 6.7B 14 | 3 | 136 |

| T5-11B [55] | 26.45 | 1,202 |

| LaMDA [125] | 552 | 25,091 |

| MT-NLG [96] | 284 | 12,909 |

| BLOOM [108] | 25 | 1,136 |

| OPT [107] | 75 | 3,409 |

| DeepSeek-R1 [14] | 40 | 1,818 |

| PaLM [106] | 552 | 25,091 |

| Gopher [104] | 280 | 12,727 |

| Jurassic-1 [109] | 178 | 8,091 |

| WuDao 2.0 [124] | 1,750 | 79,545 |

| Megatron-LM [95] | 8.3 | 377 |

| T5-3B [55] | 15 | 682 |

| Gemma [81] | 7 | 318 |

| Turing-NLG [122] | 17 | 773 |

| Chinchilla [105] | 70 | 3,182 |

| LLaMA 3 [62] | 2,290 | 104,091 |

| DistilBERT [102] | 0.15 | 7 |

| ALBERT [101] | 0.18 | 8 |

| ELECTRA [100] | 0.25 | 11 |

| RoBERTa [99] | 0.35 | 16 |

| XLNet [98] | 0.45 | 20 |

| FLAN-T5 [117] | 12 | 545 |

| Switch Transformer [123] | 1,200 | 54,545 |

| CTRL [97] | 3.2 | 145 |

| GLaM [113] | 900 | 40,909 |

| T0 [111] | 18 | 818 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).