1. Introduction

Overexpression or abnormal functionality of HER1 and/or HER2 is found in various solid tumors and plays a key role in tumor initiation and progression [

1]. The uncontrolled activity of HER1/HER2 homodimers or heterodimers excessively activates critical intracellular pathways, leading to sustained proliferation [

2]. These receptors have been the targets selected for many monoclonal antibodies, tyrosine kinase inhibitors and vaccines, which are registered or in development. However, tumors often develop resistance to HER specific targeting therapies that involves other receptors of the family. Therefore, therapies directed to more than one target in the HER family could be more potent and prevent or delay the emergence of resistance. Understanding the molecular basis of antitumor therapies and tumor cell resistance mechanisms is crucial [

3]. Recent studies show that the effectiveness of treatments targeting tumoral growth and signaling pathways is influenced by the tumor’s microenvironment [

4]. Thus, defining how oncogenic signaling involving HER1 and HER2 affects this microenvironment is increasingly important [

5]. However, most therapeutic antibodies and vaccine candidates targeting HER1 and/or HER2 do not recognize murine counterparts (ErbB1 and ErbB2, respectively), limiting the characterization of their mechanisms in immunocompetent mice [

6,

7]. Creating syngeneic mouse tumor lines with human proteins via lentiviral transduction is an effective and cost-efficient approach for immunotherapy studies targeting tumor-associated antigens [

8]. Lentiviruses facilitate efficient gene expression in various cell lines [

9] and allow stable integration of recombinant DNA into active chromatin sites [

10], making them valuable for generating syngeneic tumor models.

HER1 and HER2 are overexpressed in solid tumors of epithelial origin, including prostate, lung, and breast carcinomas, and often associated with poor prognosis and reduced patient survival. HER1 is overexpressed in 80% of lung tumors, and some studies report that overexpression of HER1 is a predictive factor for trastuzumab response in HER2+ tumors [

11]. In breast carcinoma, HER2 expression is linked to a more aggressive phenotype, where co-expression with HER1 could promote distant metastasis and is significantly associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with breast cancer [

12]. Furthermore, studies demonstrate a strong correlation between HER1 overactivation and metastatic progression in prostate tumors, emphasizing the importance of HER2 heterodimers in the development of resistance [

13]. Given the significance of HER1/HER2 heterodimer formation in tumor progression [

14], it is essential to develop models that express both receptors, enabling the evaluation of their combined inhibition in various cellular contexts. In the present study, we generated in vitro murine models by transducing RM1 (prostate cancer), 3LL (lung carcinoma), and 4T1 (breast carcinoma) cell lines, with lentivirus expressing HER1 and/or HER2 in using a lentiviral approach.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Antibodies and Reagents

HER1-specific monoclonal antibody cetuximab (Erbitux) was obtained from Roche (Switzerland), while the HER2-specific mAb 5G4, a biosimilar to trastuzumab, was sourced from CIM [

15]. Antibodies targeting HER1 (#4267S), phosphorylated HER1 (Y1068, #2234L), phosphorylated ERK1/2 (T202/Y204, #9102), ERK1/2 (#9102), HER2 (#2242) and β-actin (#4967S) were acquired from Cell Signaling Technologies. Antibody targeting phosphorylated HER2 (Y1248, #K612) were acquired from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG 1478 (Tyrophostin AG-1478, #T4182-5MG) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and recombinant human EGF was obtained from the Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (CIGB).

2.2. Plasmids

The plasmids used in this work correspond to the third-generation HIV-1-based lentiviral (LV) packaging system and included three helper plasmids (Invitrogen, USA): (1) pLP1 (contains gag and pol genes), (2) pLP2 (contains rev gene) and 3) pLP VSV-G (contains VSV G glycoprotein gene). For HER1 expression,

erbB1 gene encoding full-length human EGFR pLenti6.3/V5–DEST vector was cloned into pLenti6.3/V5–DEST vector (with blasticidin marker) and kindly donated to our lab by Prof. Maicol Mancini. For HER2 expression, pHAGE-ERBB3 was a gift from Gordon Mills & Kenneth Scott (Addgene plasmid #116734;

http://n2t.net/addgene:116734; RRID: Addgene_116734).

2.3. Cell lines and Culture Conditions

The HEK293-T cell line (CRL-11268) was used as a packaging strain to produce lentiviral particles. The murine prostate carcinoma-derived cell line (RM1) was kindly donated by Dr. Andrea Alimonti, Director of the Swiss Cancer Research Institute, the breast carcinoma-derived cell line 4T1 was obtained from the ATCC and the lung carcinoma-derived cell line D122 clone of Lewis lung carcinoma (3LL) [

16]. Cells were maintained in basal growth media (DMEM-F12) purchased from Gibco and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco).

2.4. Transduction of cells using LV

2.4.1. Production of LV

Lentivirus were produced by transfection of HEK-293T using lineal PEI (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) as previously described [

17]. The cells were transfected with the lentiviral transfer plasmids and helper plasmids: pLP1, pLP2 and pLP VSV-G at a ratio of (2:1:1:1) (w:w:w:w) for 30 μg of total DNA. After 6 h of incubation at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO

2, FBS was added to the culture and the supernatant was harvested at 72 h post-transfection. The cell culture supernatant was centrifuged at 290 g for 5 min, filtered (0.45 mm membrane) and stored at 4°C.

2.4.2. Transduction of Cells

The day prior to transduction, RM1, 3LL and 4T1 cells were seeded in 6-well plate using DMEM/F12-FBS medium and incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2. After 16 h, transduction was performed by incubating supernatant LVs with cells in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10 μg/mL of polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). For co-transduction, the supernatant LV encoding HER1 and HER2 were used in 1:1 ratio. Eight hours post-transduction, the medium was replaced with fresh DMEM/ F12-FBS medium and blasticidin for cell transduction with LV encoding HER1 or puromycin for cell transduction LV of HER2. A second round of transduction was performed in the same conditions as outlined above. The cell culture supernatant was harvested at 72 h post-transduction and HER1 and/or HER2 expression was assessed by Flow cytometry.

2.5. Inoculation in Mice of Heterologous Syngeneic Models

Female mice, aged 8–12 weeks old, were purchased from the National Center for Laboratory Animals Production (CENPALAB, Havana, Cuba). All mice were kept under pathogen-free conditions. Animal experiments were approved by the Center of Molecular Immunology’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, or CICUAL (CIM, Havana, Cuba). BALB/c mice were used for 4T1-derived models, while C57BL/6 mice for RM1 and 3LL models. In all cases, 8 x 105 cells were inoculated into the right flank of the mice. Once tumor growth matched the sacrifice criteria of the mice, tumors were excised and disaggregated, and cell suspensions were inoculated into another group of the same strain. This process was repeated three times. Finally, cell suspensions obtained from tumor disaggregated were cultured to establish the desired tumor cell lines.

2.6. Flow Cytometry Assays

2.6.1. Detection of HER1 and/or HER2 Expression at the Cell Membrane

RM1, 3LL, and 4T1 parental cells and corresponding modified cells expressing HER1 and/or HER2, were seeded in 6-well plates (105 cells/ well) for 24 hours. Cells were detached with trypsin for 5 minutes, washed with PBS by centrifugation at 300g for 5 minutes, and blocked in saline with 1% (w/v) albumin for 20 minutes at 4°C. They were then incubated with cetuximab or 5G4 (1 µg/mL) for 20 minutes at 4°C, followed by an anti-human IgG secondary antibody conjugated to allophycocyanin (APC) (1:400) for 30 minutes at 4°C. A minimum of 5 x 103 cells was analyzed using a CyFlow flow cytometer (Partec Sysmex, Germany). Three washes with blocking solution were performed during incubations, and data analysis was conducted using FlowJo 10.0.7 software (Tree Star Inc.).

2.7. Immunoblotting Assays

RM1, RM1-HER1, RM1-HER2 y RM1-HER1/HER2 (2,5 x 105 cells/well) cells were seeded in 6-well plates for 24 hours. The culture medium was removed, and cells were kept overnight in DMEM-F12 medium without FBS supplementation for 16 hours. Afterwards, cells were stimulated with EGF (100 ng/mL) for 10 min at 37 °C. Cells were washed twice with cold PBS, and scraped into lysis buffer [50 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 10% glycerol, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA,1 mM EGTA, 10 mM NaF, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, and complete protease inhibitor cocktail. Next, lysates were centrifuged at 14,000g for 15 min at 4°C and supernatants were preserved at -80°C. After protein separation by gel electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Immunoblotting was performed according to the antibody manufacturers’ recommendation. Antibody binding to membranes was detected using horseradish peroxidase–secondary antibodies (BioRad), followed by treatment with ECL Clarity detection reagents (BioRad).

2.8. Colorimetric Assays

2.8.1. AlamarBlue Assay

RM1, 3LL, and 4T1 parental cells, along with corresponding modified cells expressing HER1 and/or HER2, were plated in 96-well plates at 5 x 10

3 cells per well in a medium with 10% FBS (culture condition) at 37°C in a 5% CO

2 atmosphere. Absorbance was measured 4 hours after the assay began, with tumor growth assessed at 24, 48, and 72 hours. Afterward, the medium was removed, and 10 µL of AlamarBlue reagent [

18] was added to each well for a final concentration of 10%. The plates were incubated in the dark at 37°C for 2 hours, and absorbance was measured at 540 nm and 630 nm wavelength using a spectrophotometer (Dialab, Austria).

2.8.2. MTT Assay

RM1, 3LL, and 4T1 parental cells and corresponding modified cells expressing HER1 and/or HER2 were cultured in 96-well plates at a density of 5 x 103 cells per well for 24 hours. After removing the medium, treatments were applied in culture medium with 1% FBS: 5G4 (10 μg/mL), Cetuximab (10 μg/mL), and TKI AG1478 (1:500). Control cells were incubated with medium and 1% FBS for maximum viability (100%). Six replicates per condition were incubated for 96 hours. Afterward, the culture supernatant was removed, and MTT reagent (1 mg/mL) was added. Cells were incubated for 4 hours at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Formazan crystals were solubilized with 100 µL of dimethyl sulfoxide per well. Absorbance at 540 nm and 620 nm was measured using a spectrophotometer, and the percentage of viable cells was calculated using untreated cells as the reference for maximum viability.

2.9. Statistical and Data Analyses

Graphical and statistical analysis was done using GraphPad Prism 9.3.1 software. Figures were constructed in GIMP 2.10.8 software. Normality was evaluated by Shapiro Wilk test, and Levene test was used to assess variance homogeneity. Tests used to determine statistical differences among group media are specified in the figure legends. In graphics, significant differences were highlighted with asterisks. (*) p<0.05, (**) p<0.01, (***) p<0.001.

3. Results

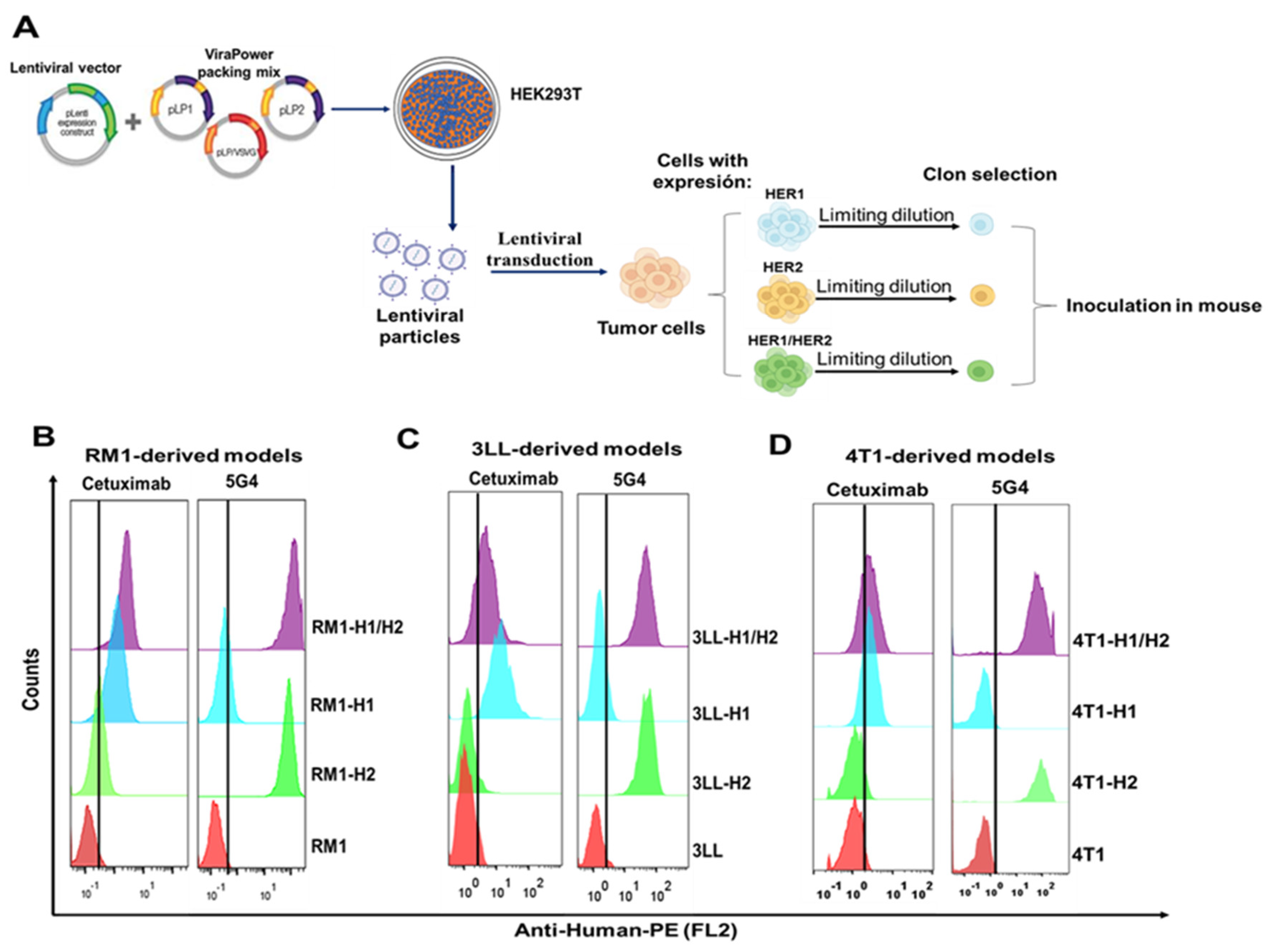

3.1. Generation of Cellular Models from Various Tumor Types with Heterologous Expression of HER1 and/or HER2

Tumoral cell models expressing HER1 and/or HER2 receptors were created via lentiviral transduction using particles containing their full-length coding sequences. These lentiviral particles transduced tumoral cells from different origins (RM1-prostate, 3LL-lung, and 4T1-breast). The populations that emerged from antibiotic selection underwent cloning through limiting dilution, and those clones exhibiting the highest levels of membrane receptor expression were chosen for inoculation into mice (C57BL/6 for RM1 and 3LL, Balb/c for 4T1). The strategy is summarized in

Figure 1A.

We assessed the membrane expression of the receptors in heterologous models within the primary culture after three inoculations in mice using flow cytometry with specific monoclonal antibodies: cetuximab for HER1 and the 5G4 biosimilar for HER2.

Figure 1B-D demonstrate that HER1-expressing cells show increased mean fluorescence intensity (blue and violet histograms) after cetuximab incubation, while HER2-expressing cells (green and violet histograms) exhibit a similar shift after 5G4 incubation. Both antibodies exhibited high affinity for their respective receptors [

19,

20]. Notably, MFI values for 5G4 were consistently higher than those for cetuximab across all models, suggesting greater HER2 expression compared to HER1

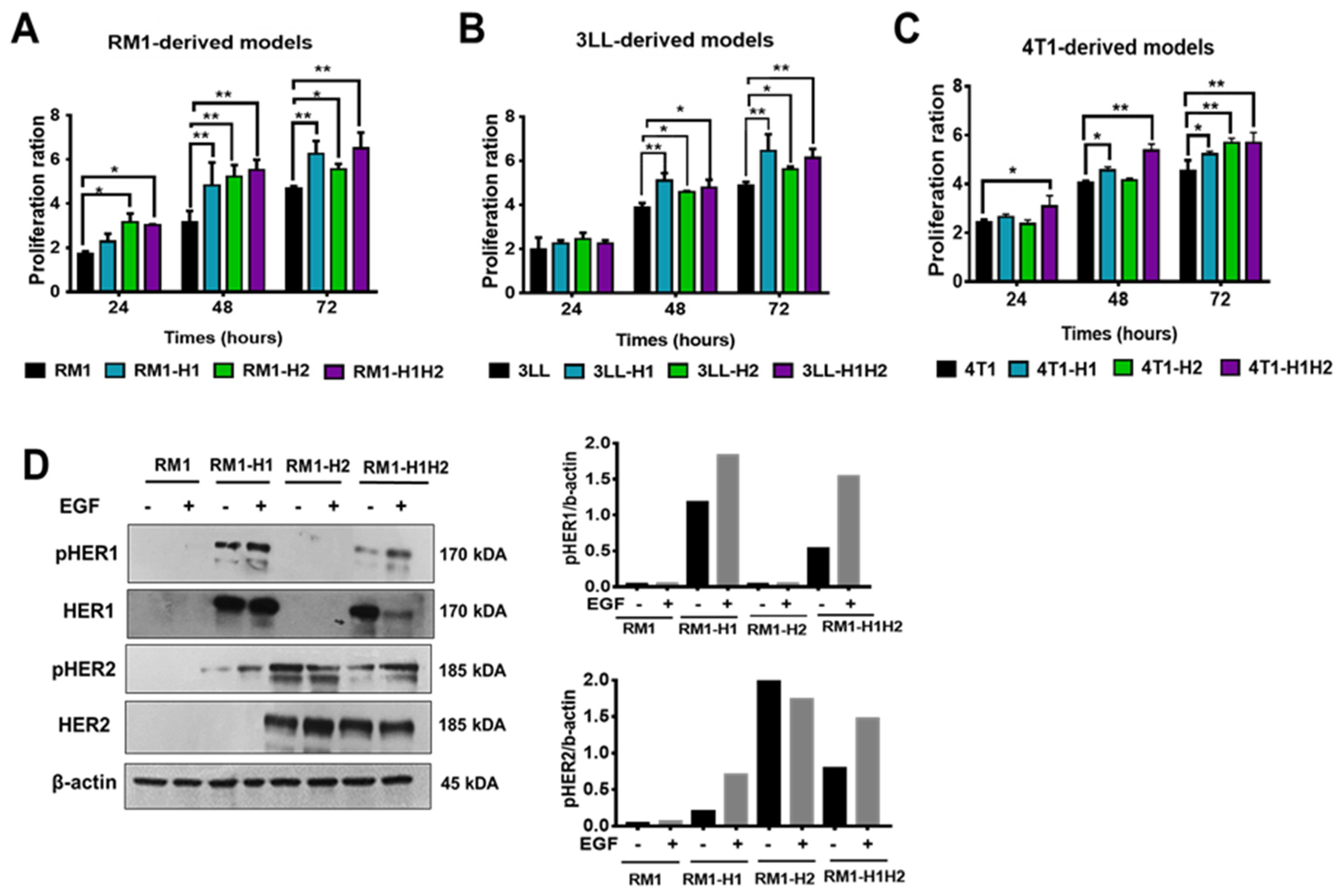

3.2. In vitro characterization of the Functionality of HER1 and/or HER2 Receptors in the Generated Models

The impact of HER1 and/or HER2 expression on cell proliferation was evaluated across all generated models (RM1, 3LL and 4T1), using a colorimetric assay. While HER1 and HER2 expression significantly enhanced proliferation in all models compared to parental cells, confirming the functional role of these receptors in promoting tumor cell growth (

Figure 2A-C).

To validate the functionality of the heterologous receptors and further explore the mechanisms underlying the observed proliferative increase, we assessed HER1 and HER2 phosphorylation in RM1-derived models. The RM1 cell line, was selected as a representative model to confirm receptor activation.

Figure 2D shows phosphorylated HER1 (pHER1) bands at tyrosine Y1068 in RM1-HER1 and RM1-HER1/HER2 models. These bands were detected in stimulated and non-stimulated cells, indicating basal phosphorylation. Densitometry analysis revealed increased band intensity following EGF stimulation, confirming ligand-induced activation. In HER1-expressing models, a band corresponding to the receptor’s full molecular weight was observed; however, this expression decreased in the RM1-HER1/HER2 after EGF treatment. Furthermore, we assessed HER2 activation and found a phosphorylated receptor band (pHER2) in models with heterologous receptor expression. Notably, HER2 phosphorylation in the RM1-HER2 model occurs independently of EGF, indicating a basal self-activation mechanism. In contrast, densitometric analysis showed increased HER2 phosphorylation in the RM1-HER1/HER2 model after ligand treatment, suggesting HER1/HER2 heterodimer formation. Additionally, HER2 phosphorylation in the RM1-HER1 model post-EGF may indicate heterodimerization with murine ErBb2, likely due to due commercial antibody cross-reactivity.

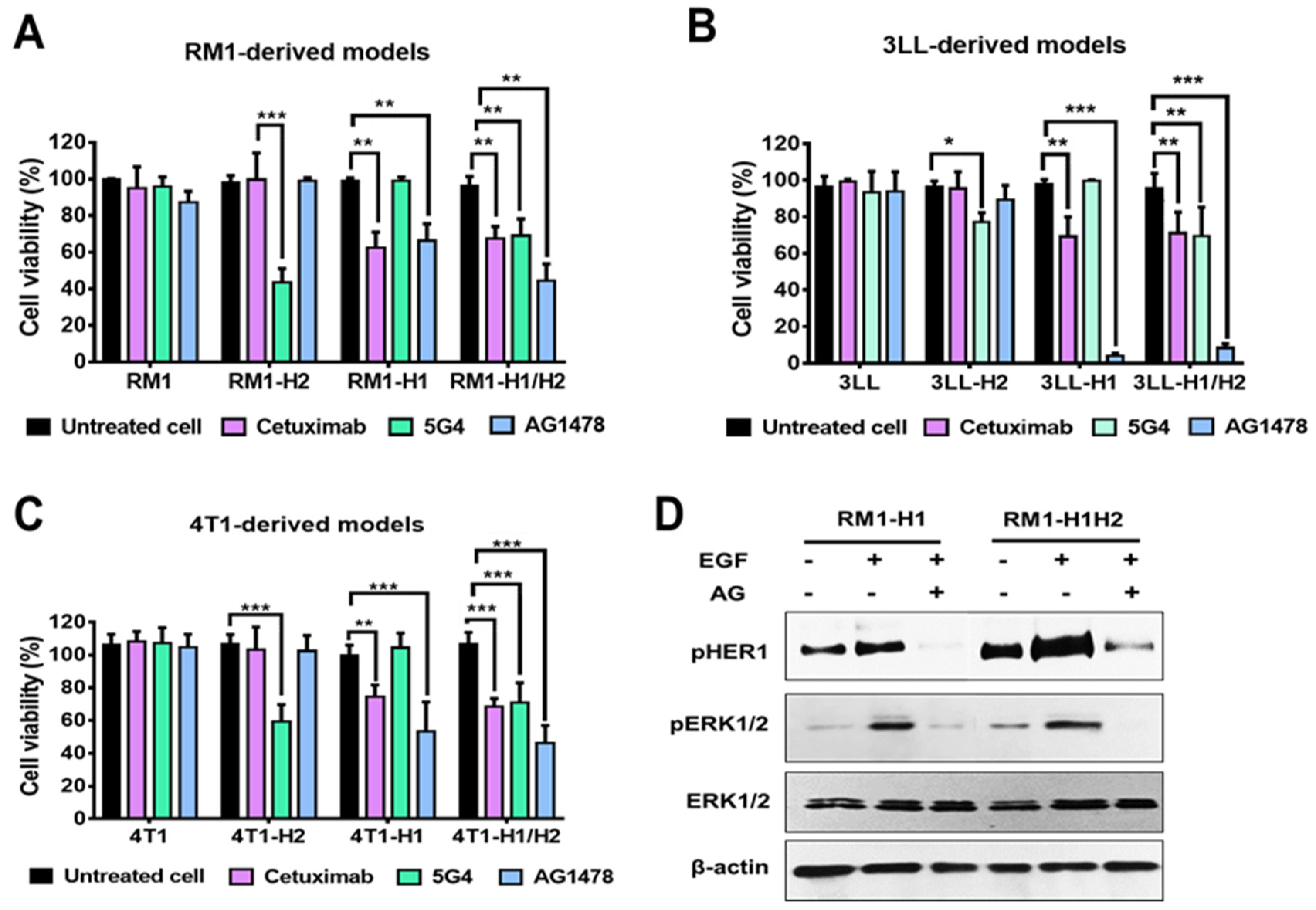

Finally, we assessed the sensitivity of the generated cellular models to the blockade and inhibition of HER1 and/or HER2 receptors. The cells were treated with specific monoclonal antibodies (cetuximab or 5G4) and the HER1-specific tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478. As illustrated in

Figure 3A-C, inhibition of HER2 by the 5G4 antibody resulted in a significant decrease in cell viability (40% to 60%) in the HER2+ models. Similarly, the HER1+ models exhibited a reduced cell viability after blocking this receptor with the cetuximab antibody or, more drastically, following treatment with a specific TKI. Noticeably, HER1-expressing models derived from 3LL cells demonstrated high sensitivity to treatment with the TKI, leading to a reduction in viability of up to 90% (

Figure 2E). Parental cells exhibited no sensitivity to any of the treatments evaluated. The latest, along with the lack of effect of these therapies in the cells that do not express the corresponding antigen, suggests the specificity of the observed effect.

In the RM1-derived models, we assessed the effect of HER1 inhibition using the TKI (AG1478) on ERK1/2 activation. As shown in

Figure 3D, EGF stimulation induced an increase in ERK1/2 phosphorylation. However, this effect was reversed upon HER1 inhibition, as evidenced by the reduction in HER1 phosphorylation levels following treatment with the inhibitor.

4. Discussion

Uncontrolled HER1/HER2 homodimer and heterodimer activity leads to excessive activation of key intracellular pathways, resulting in increased proliferation, invasiveness, and resistance to apoptosis in cancer cells [

1]. Both receptors are also involved in immune evasion and metabolic reprogramming, making them critical therapeutic targets [

21]. Specific inhibitors, including tyrosine kinase inhibitors, monoclonal antibodies, and therapeutic vaccines, have been developed [

22]. However, targeting a single receptor can induce resistance mechanisms due to the upregulation of other family members, demanding treatments that inhibit multiple receptors [

23]. Understanding the impact of HER1 and HER2 inhibitors on tumor physiology and microenvironments is essential, and preclinical models effectively simulate tumor behaviour for research optimization.

In vivo studies examining the antitumor effects of therapies targeting HER1 and/or HER2 receptors require immunocompetent mice, as they better represent tumor-microenvironment dynamics and enhance preclinical result predictions [

24]. In this sense, the generation of syngeneic mouse models expressing human proteins is valuable for tumor biology and immunotherapy studies and is cost-effective to develop and maintain [

25].

The lentiviral transduction method effectively introduces foreign DNA, allowing multiple copies of the integrated transgene per cell at active transcription sites [

26]. However, lentivirus-generated models for heterologous expression face the challenge of random transgene integration, which can lead to variable expression levels and affect transgene stability and functionality [

9]. Our results show that these models retained HER1 and/or HER2 expression levels on their membranes after inoculation in mice, indicating efficient integration of HER1 and/or HER2 DNA into the modified cells’ genomes [

27]. In all the generated models, HER2 expression was higher than HER1, possibly due to its insertion in more active chromatin sites. However, structural differences among these protein receptors may also explain such differential expression levels. Recent studies suggest that post-translational modifications, such as N-glycosylation, can hinder the secretion of recombinant proteins, with HER2 having eight potential N-glycosylation sites and HER1 having 12-14 [

28].

The functionality of heterologous receptors in RM1-derived models was confirmed by evaluating their phosphorylation status. EGF stimulation significantly enhanced HER1 phosphorylation, while HER2 activation also increased in HER1-expressing models, suggesting the formation of active heterodimeric complexes. These findings indicate that HER1 and HER2 can heterodimerize not only in heterologous contexts but also with autologous ErbB2. Notably, studies have shown that HER1/HER2 heterodimers exhibit stronger activation compared to homodimers. Additionally, activated HER1 undergoes rapid internalization and lysosomal degradation, leading to reduced expression following EGF stimulation. This may explain the observed decrease in HER1/HER2 levels in RM1 cells treated with EGF. Following ligand binding, homo- and heterodimeric interactions between HER receptors induce autophosphorylation at the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain, creating docking sites for adapter and scaffolding proteins that activate various downstream signaling pathways [

29]. Key pathways include RAS-RAF-MEK-MAPK, which regulates gene transcription and cell cycle progression from G1 to S phase, and PI3K-Akt, which triggers anti-apoptotic signals [

30]. The increased proliferation in models expressing HER1 and/or HER2 suggests that, indeed, inserted receptors can dimerize and transactivate while maintaining the necessary structure for ligand binding. However, it would be beneficial to further confirm that inserted HER1 and HER2 are able to engage cell signaling machinery and trigger previously mentioned cascades.

HER1 and HER2 receptors are central to tumor physiology, and their suppression attenuates tumor growth. In RM1-derived models, HER1 inhibition reversed ERK1/2 phosphorylation, demonstrating HER1 phosphorylation’s functional relevance within the heterologous context of these cell lines. Generated models expressing HER1 and/or HER2, when treated with specific monoclonal antibodies or TKIs, show decreased cell viability, unlike parental lines. This indicates the receptors’ functionality and the sensitivity of expressing lines to targeted therapies. Various modified cell lines, such as EL4-HER2 (lymphoma) [

31], CT26-HER1 (colon) [

32], and 4T1-HER2 (breast) [

33], have facilitated studies on therapies like cetuximab and trastuzumab. However, murine models with both receptors have not been reported, limiting the simultaneous HER1 and HER2 blockade evaluation. Models from different cancer types would help assess the effects of inhibiting one or both receptors in parallel. For instance, previous reports suggest that HER2 expression in lung cancer may lead to HER1 mutations, and co-expression of HER1 and HER2 correlates with poor outcomes in breast carcinoma. Also, several studies describe an important relationship between the hyperactivation of HER1 and HER2 and the metastatic progression of prostate tumors. Therefore, HER1/HER2-coexpressing generated models will allow us to explore the specific therapies (alone or combined) and their effects on tumor progression and the microenvironment in different cellular contexts.

This study takes advantage of a lentiviral transduction platform to generate tumor models from various locations with heterologous expression of HER1 and/or HER2. To our knowledge, these are the first tumor models derived from prostate, lung and breast carcinomas that simultaneously express human HER1 and HER2, providing a unique platform for studying targeted therapies. These models could accelerate the development of novel immunotherapies and improve our understanding of resistance mechanisms in HER1/HER2 driven cancers.

5. Conclusions

The present work generated tumor models from different mouse cell lines carcinomas with heterologous expression of HER1 and/or HER2. These models represent valuable tools for studying the biology of HER1/HER2-driven carcinomas and evaluating the efficacy of targeted therapies in immunocompetent settings.

Author Contributions

TFB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. ARHB: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation. LCG: Methodology, Investigation. MAGC: Methodology, Investigation. NGS: Methodology, Investigation. BSR: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Resources, Supervision. GBB: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The protocol performed on mice was duly reviewed and approved by the CIM Institutional Committee on the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals.

Data Availability Statement

The lead contact will share all data reported in this paper upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Dr. Maicol Mancini from the Oncogenic Pathways in Lung Cancer, Institut de Recherche en Cancérologie de Montpellier (IRCM)-Université de Montpellier (UM)-Institut Régional du Cancer de Montpellier (ICM), who kindly donated lentiviral vector encoding full-length human EGFR (HER1) receptor to our group.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| HER1-HER2 |

Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 1-2 |

| ATCC |

American Type Culture Collection |

| CIM |

Molecular Immunology Center |

| DMEM-F12 |

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium, nutrient mixture F12 |

| TKI |

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors |

| MFI |

Mean Fluorescence Intensity |

References

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.R.; Yarden, Y. The EGFR-HER2 module: a stem cell approach to understanding a prime target and driver of solid tumors. Oncogene 2016, 35, 2949–2960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Z.N.; Tian, Q.; Teng, Q.X.; Wurpel, J.N.; Zeng, L.; Pan, Y.; et al. Understanding and targeting resistance mechanisms in cancer. MedComm 2023, 4, e265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goenka, A.; Khan, F.; Verma, B.; Sinha, P.; Dmello, C.C.; Jogalekar, M.P.; et al. Tumor microenvironment signaling and therapeutics in cancer progression. Cancer Communications 2023, 43, 525–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, A.; Wei, T.; Meng, H.; Luo, P.; Zhang, J. Role of the dynamic tumor microenvironment in controversies regarding immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with EGFR mutations. Molecular cancer 2019, 18, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Cruz, J.L.; Joseph, S.; Pett, N.; Chew, H.Y.; Tuong, Z.K.; et al. Characterization of 7A7, an anti-mouse EGFR monoclonal antibody proposed to be the mouse equivalent of cetuximab. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 12250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis Phillips, G.; Guo, J.; Kiefer, J.R.; Proctor, W.; Bumbaca Yadav, D.; Dybdal, N.; et al. Trastuzumab does not bind rat or mouse ErbB2/neu: implications for selection of non-clinical safety models for trastuzumab-based therapeutics. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simm, D.; Popova, B.; Braus, G.H.; Waack, S.; Kollmar, M. Design of typical genes for heterologous gene expression. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 9625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elegheert, J.; Behiels, E.; Bishop, B.; Scott, S.; Woolley, R.E.; Griffiths, S.C.; et al. Lentiviral transduction of mammalian cells for fast, scalable and high-level production of soluble and membrane proteins. Nature protocols 2018, 13, 2991–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalidasan, V.; Ng, W.H.; Ishola, O.A.; Ravichantar, N.; Tan, J.J.; Das, K.T. A guide in lentiviral vector production for hard-to-transfect cells, using cardiac-derived c-kit expressing cells as a model system. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 19265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Seo, A.; Kim, E.; Jang, M.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; et al. Prognostic and predictive values of EGFR overexpression and EGFR copy number alteration in HER2-positive breast cancer. British journal of cancer 2015, 112, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Pu, T.; Chen, S.; Qiu, Y.; Zhong, X.; Zheng, H.; et al. Breast cancers with EGFR and HER2 co-amplification favor distant metastasis and poor clinical outcome. Oncology letters 2017, 14, 6562–6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, K.C.; Hiles, G.L.; Kozminsky, M.; Dawsey, S.J.; Paul, A.; Broses, L.J.; et al. HER2 and EGFR overexpression support metastatic progression of prostate cancer to bone. Cancer research 2017, 77, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.; Sun, P.; Wang, X.; Long, C.; Liao, S.; Dang, S.; et al. Structure and dynamics of the EGFR/HER2 heterodimer. Cell Discovery 2023, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro Pérez, L.; Rodríguez Taño, A.d.l.C.; Martín Márquez, L.R.; Gómez Pérez, J.A.; Valle Garay, A.; Blanco Santana, R. Conformational characterization of a novel anti-HER2 candidate antibody. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0215442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenbach, L.; Hollander, N.; Greenfeld, L.; Yakor, H.; Segal, S.; Feldman, M. The differential expression of H-2K versus H-2D antigens, distinguishing high-metastatic from low-metastatic clones, is correlated with the immunogenic properties of the tumor cells. International Journal of Cancer 1984, 34, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, J.R.; Prieto, Y.; Oramas, N.; Sánchez, O. Polyethylenimine-based transfection method as a simple and effective way to produce recombinant lentiviral vectors. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology 2009, 157, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twigg, R. Oxidation-reduction aspects of resazurin. Nature 1945, 155, 401–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, V.L.; Souza-Egipsy, V.; Gion, M.; Pérez-García, J.; Cortes, J.; Ramos, J.; et al. Binding affinity of trastuzumab and pertuzumab monoclonal antibodies to extracellular HER2 domain. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24, 12031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, B.; Sundaram, S.; Walton, W.; Patel, I.; Kuo, P.; Khan, S.; et al. Differentiation between the EGFR antibodies necitumumab, cetuximab, and panitumumab: In vitro biological and binding activities. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2011, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, K.J.; Sung, J.H.; Kim, J.W.; Han, S.-H.; Lee, H.S.; Min, A.; et al. EGFR or HER2 inhibition modulates the tumor microenvironment by suppression of PD-L1 and cytokines release. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 63901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarden, Y.; Pines, G. The ERBB network: at last, cancer therapy meets systems biology. Nature Reviews Cancer 2012, 12, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett, J.T.; Arteaga, C.L. Resistance to HER2-directed antibodies and tyrosine kinase inhibitors: mechanisms and clinical implications. Cancer biology & therapy 2011, 11, 793–800. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, T.; Fakurnejad, S.; Sayegh, E.T.; Clark, A.J.; Ivan, M.E.; Sun, M.Z.; et al. Immunocompetent murine models for the study of glioblastoma immunotherapy. Journal of translational medicine 2014, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechner, M.G.; Karimi, S.S.; Barry-Holson, K.; Angell, T.E.; Murphy, K.A.; Church, C.H.; et al. Immunogenicity of murine solid tumor models as a defining feature of in vivo behavior and response to immunotherapy. Journal of immunotherapy 2013, 36, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.H.; Pallant, C.; Sampson, C.J.; Boiti, A.; Johnson, S.; Brazauskas, P.; et al. Rapid lentiviral vector producer cell line generation using a single DNA construct. Molecular Therapy Methods & Clinical Development 2020, 19, 47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, S.; Hegde, R.S. Membrane protein insertion at the endoplasmic reticulum. Annual review of cell and developmental biology 2011, 27, 25–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-M.; Fan, Z.-L.; Wang, X.-Y.; Wang, T.-Y. Factors affecting the expression of recombinant protein and improvement strategies in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2022, 10, 880155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, I.N. Mechanisms of activation of receptor tyrosine kinases: monomers or dimers. Cells 2014, 3, 304–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume-Jensen, P.; Hunter, T. Oncogenic kinase signalling. Nature 2001, 411, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Gaetano, N.; Cittera, E.; Nota, R.; Vecchi, A.; Grieco, V.; Scanziani, E.; et al. Complement activation determines the therapeutic activity of rituximab in vivo. The Journal of Immunology 2003, 171, 1581–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzi, C.; Cuomo, A.; Spadoni, I.; Magni, E.; Silvola, A.; Conte, A.; et al. The EGFR-specific antibody cetuximab combined with chemotherapy triggers immunogenic cell death. Nature medicine 2016, 22, 624–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taha, Z.; Crupi, M.J.; Alluqmani, N.; Fareez, F.; Ng, K.; Sobh, J.; et al. Syngeneic mouse model of human HER2+ metastatic breast cancer for the evaluation of trastuzumab emtansine combined with oncolytic rhabdovirus. Frontiers in Immunology 2023, 14, 1181014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).