Submitted:

19 February 2025

Posted:

20 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

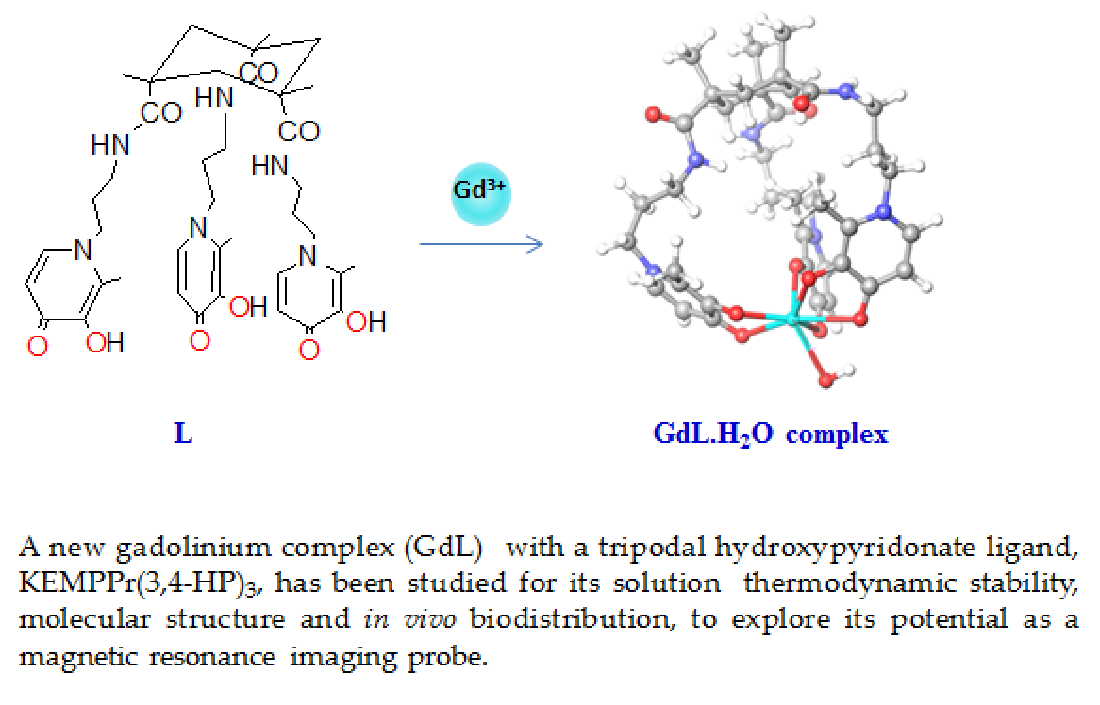

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

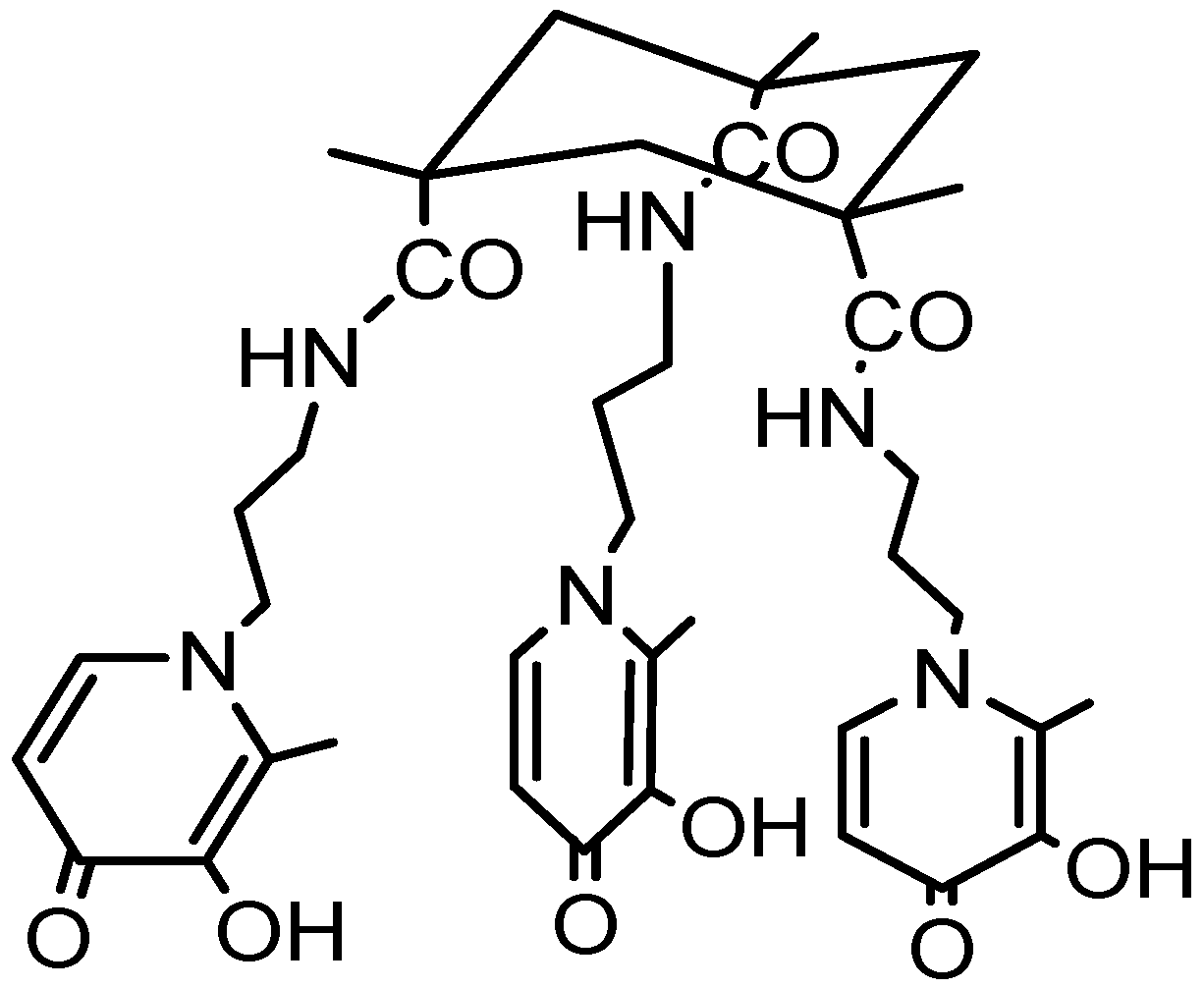

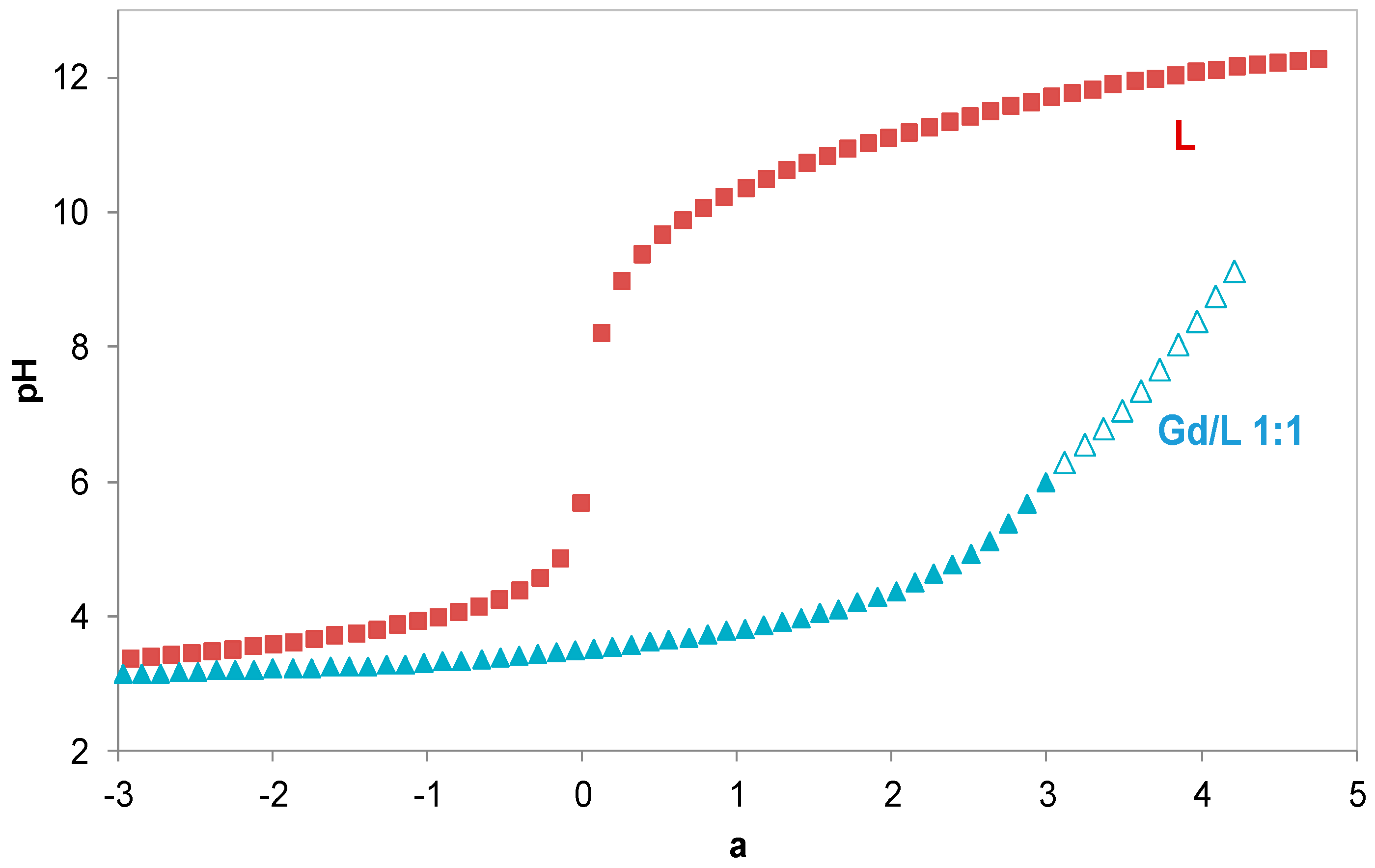

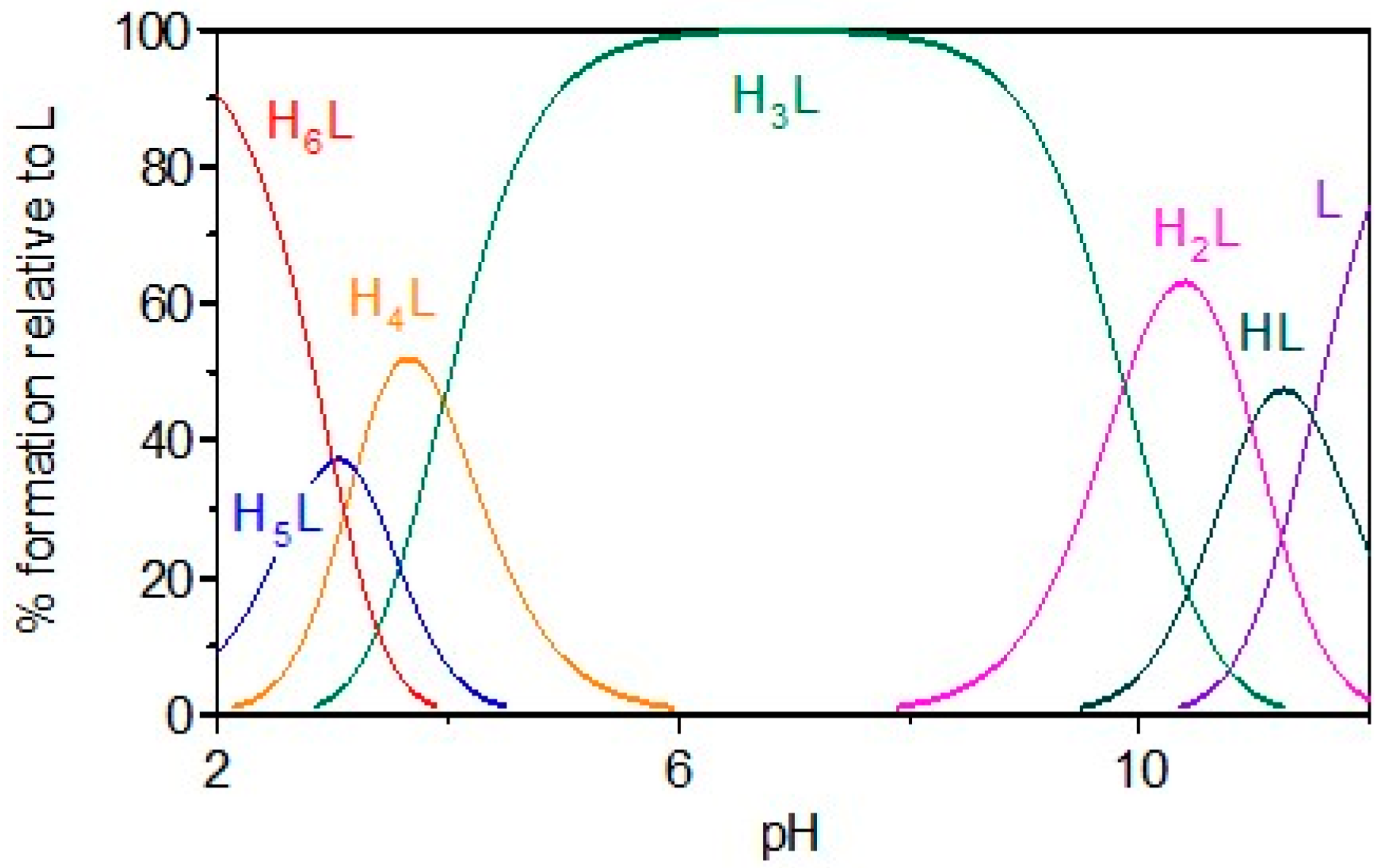

2. Results and Discussion

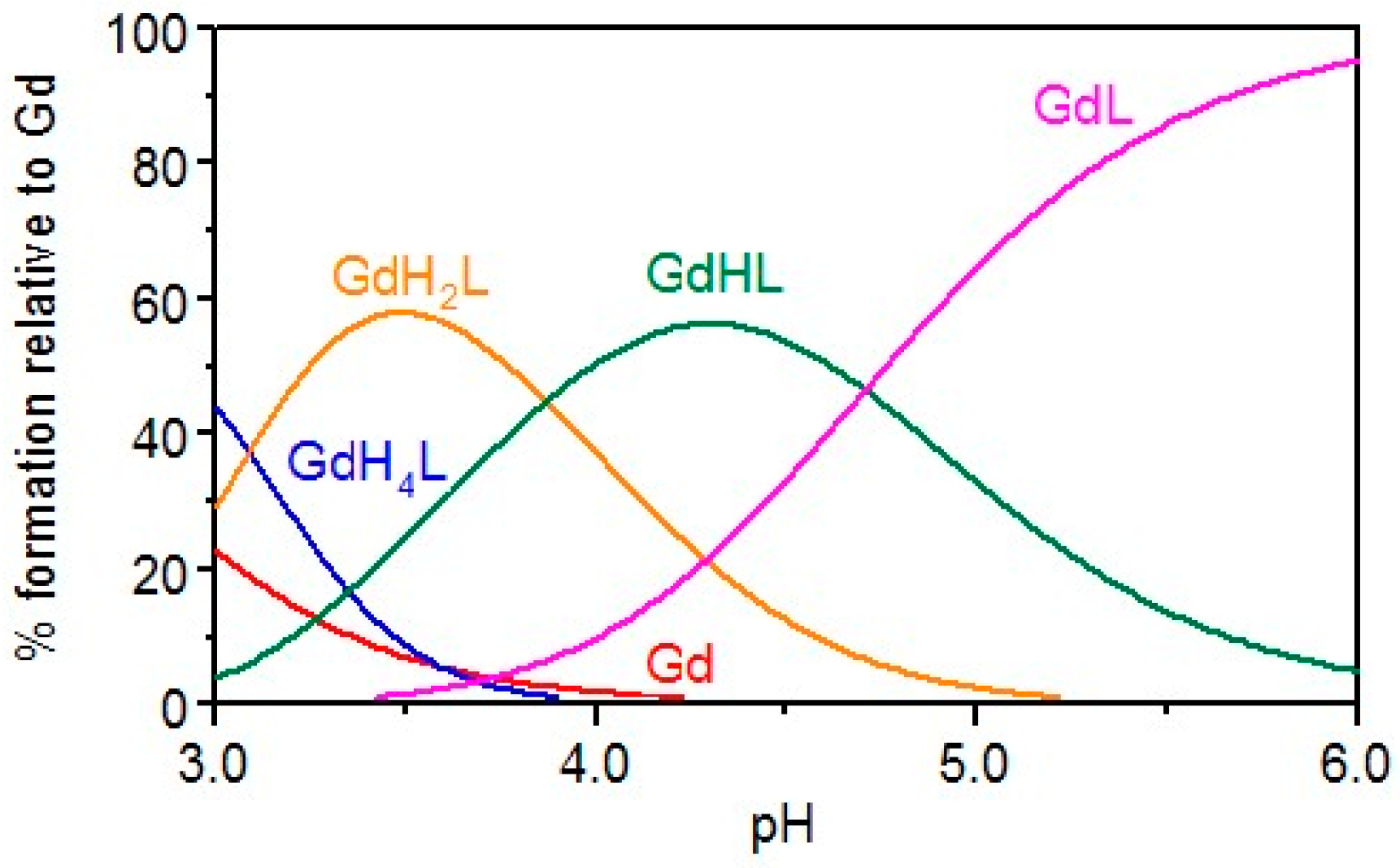

2.1. Gd Chelation Studies

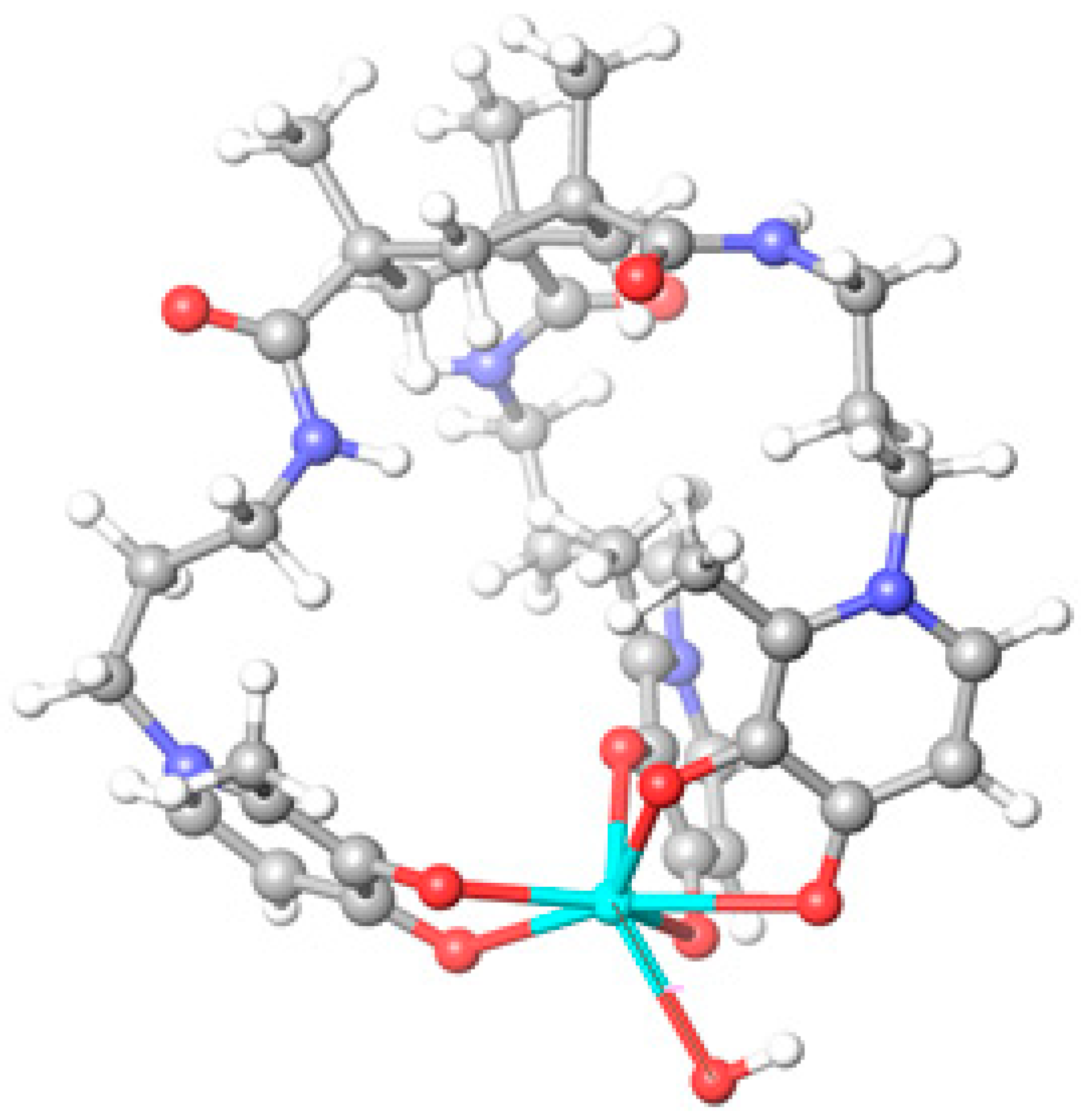

2.2. Molecular Modeling of the Gd Complex

2.3. Predicted Pharmacokinetic Properties

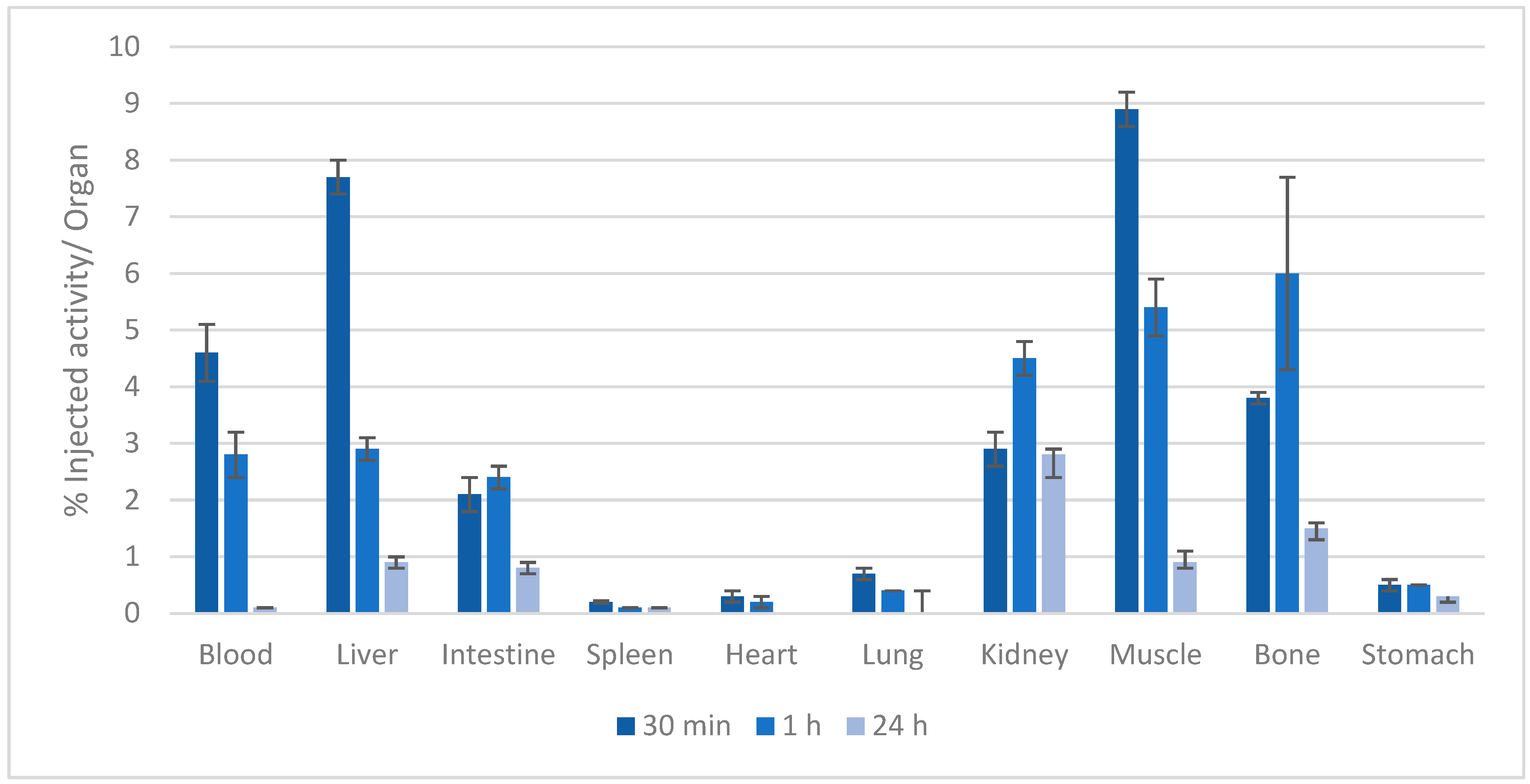

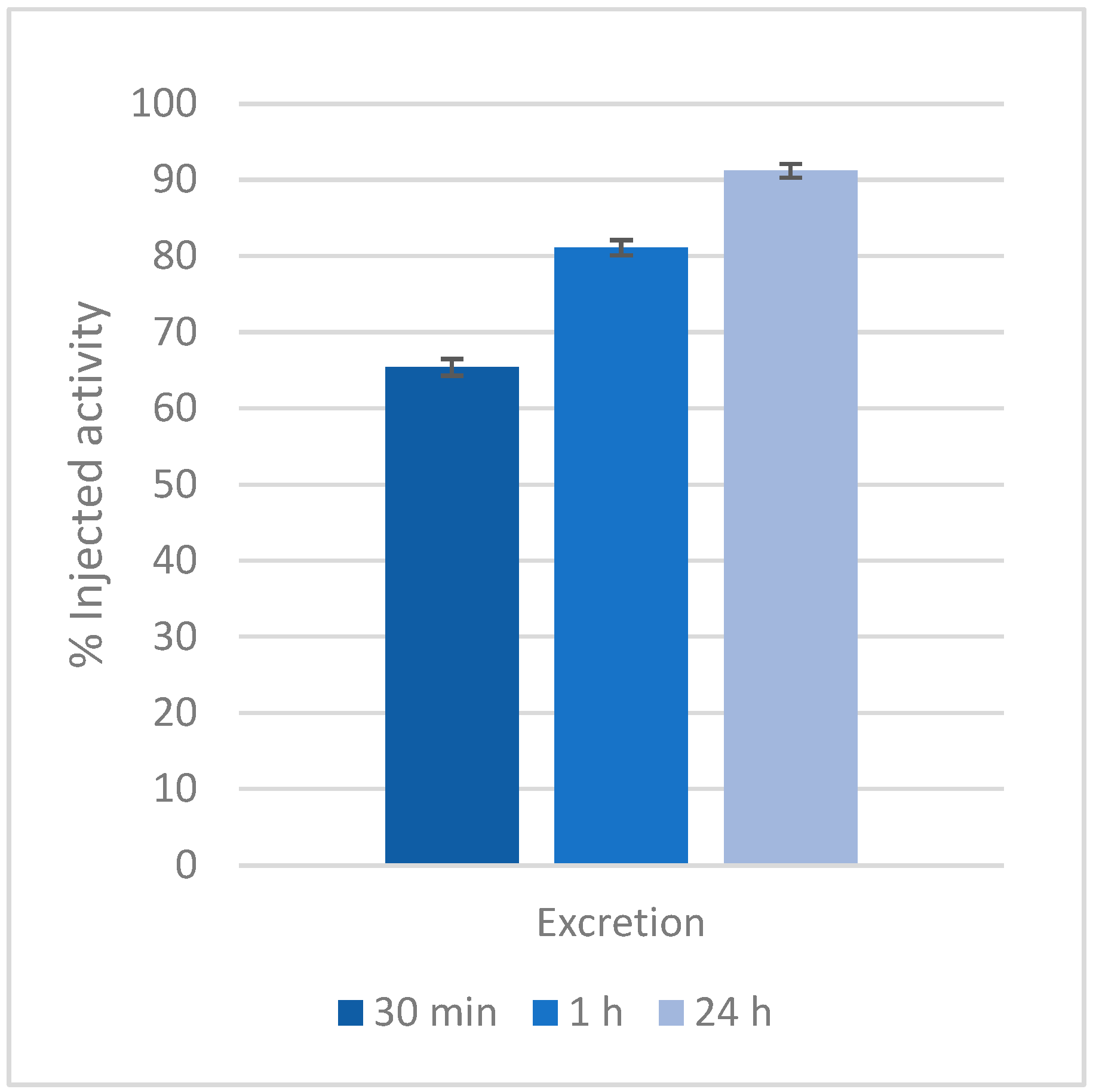

2.4. Biodistribution Studies

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Gd Complexation Studies

3.1.1. Materials and Equipment

3.1.2. Potentiometric Measurements

3.1.3. Calculation of Equilibrium Constants

3.2. Molecular Modeling

3.3. In Silico Evaluation of Pharmacokinetic Parameters

3.4. Biodistribution Studies

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethical statement

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wahsner, J.; Gale, E.M.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, A.; Caravan, P. Chemistry of MRI contrast agents: current challenges and new frontiers. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 957–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aime, S.; Crich, S.G.; Gianolio, E.; Giovenzana, G.B.; Tei, L.; Terreno, E. High sensitivity lanthanide(III) based probes for MR-medical imaging. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006, 250, 1562–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaraza, A.J.L.; Bumb, A.; Brechbiel, M.W. Macromolecules, Dendrimers, and Nanomaterials in Magnetic Resonance Imaging: The Interplay between Size, Function, and Pharmacokinetics. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2921–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.; Abramova, L.; Gaab, G.; Turabelidze, G.; Patel, P.; Arduino, M.; Hess, T.; Kallen, A.; Jhung, M. Nephrogenic Fibrosing Dermopathy Associated With Exposure to Gadolinium-Containing Contrast Agents - St. Louis, Missouri, 2002-2006. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2007, 297, 1542–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzal-Varela, R.; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, A.; Wang, H.; Esteban-Gómez, D.; Brandariz, I.; Gale, E.M.; Caravan, P.; Platas-Iglesias, C. Prediction of Gd(III) complex stability. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2022, 467, 214606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prybylski, J.P.; Semelka, R.C.; Jay, M. The stability of gadolinium-based contrast agents in human serum: a re-analysis of literature data and association with clinical outcomes. Magn. Reson. Imag. 2017, 38, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, E.J.; Avedano, S.; Botta, M.; Hay, B.P.; Moore, E.G.; Aime, S.; Raymond, K.N. Highly soluble tris-hydroxypyridonate Gd(III) complexes with increased hydration number, fast water exchange, slow electronic relaxation, and high relaxivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 1870–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierre, V.C.; Melchior, M.; Doble, D.M.J.; Raymond, K.N. Toward optimized highrelaxivity MRI agents: thermodynamic selectivity of hydroxypyridonate /catecholate ligands. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 8520–8525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendonça, A.C.; Martins, A.F.; Melchior, A.; Marques, S.M.; Chaves, S.; Villette, S.; Petoud, S.; Zanonato, P.L.; Tolazzi, M.; Bonnet, C.S.; Tóth, É.; Di Bernardo, P.; Geraldes, C.F.G.C.; Santos, M.A. New tris-3,4-HOPO lanthanide complexes as potential imaging probes. Complex stability and magnetic properties. Dalton Trans 2013, 42, 6046–6057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, S.; Gwizdała, K.; Chand, K.; Gano, L.; Pallier, A.; Tóth, É.; Santos, M.A. GdIII and GaIII complexes with a new tris-3,4-HOPO ligand, towards new potential imaging probes: complex stability, magnetic properties and biodistribution. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 6436–6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grazina, R.; Gano, L.; Sebestik, J.; Santos, M.A. New tripodal hydroxypyridinone based chelating agents for Fe(III), Al(III) and Ga(III): Synthesis, physico-chemical properties and bioevaluation. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2009, 103, 262–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gans, P.; Sabatini, A.; Vacca, A. Investigation of equilibria in solution. Determination of equilibrium constants with the HYPERQUAD suite of programs. Talanta 1996, 43, 1739–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaves, S.; Marques, S.M.; Matos, A.M.F.; Nunes, A.; Gano, L.; Tuccinardi, T.; Martinelli, A.; Santos, M.A. New Tris(hydroxypyridinones) as Iron and Aluminium Sequestering Agents: Synthesis, Complexation and In Vivo Studies. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 10535–10545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawlak, Z.; Bates, R.G. Solute-solvent interactions in acid-base dissociation: nine protonated nitrogen bases in water-DMSO solvents. J. Sol. Chem. 1975, 4, 817–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, B.; Neeraja, R.; Kumar, J.S.; Ramanaiah, M. An eletrometric method for the determination of impact of DMSO-water mixtures on pKa values of salicylic acid derivatives. Int. J. App. Pharm. 2023, 15, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, M.T.; Nagypal, I. Chemistry of complex equilibria, Ellis Horwood Ltd, Chichester, 1990, ISBN 13-173063-0.

- Raymond, K.N. , Carrano, C.J. Coordination chemistry and microbial iron transport. Acc. Chem. Res. 1979, 12, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Franklin, S.J.; Whisenhunt Jr., D. W.; Raymond, K.N. Gadolinium complex of tris[(3-hydroxy-1-methyl-2-oxo-1,2-didehydropyridine-4-carboxamido)ethyl]- amine: A New Class of gadolinium magnetic resonance relaxation agents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 7245-7246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerta, D.T.; Botta, M.; Jocker, C.J.; Werner, E.J.; Avedano, S.; Raymond, K.N.; Cohen, S.M. Tris(pyrone) Chelates of Gd(III) as High Solubility MRI-CA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 2222–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werner, E.J.; Datta, A.; Jocher, C.J.; Raymond, K.N. High-Relaxivity MRI Contrast Agents: Where Coordination Chemistry Meets Medical Imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 8568–8580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parr, R.G.; Yang, W. Density Functional Theory of Atoms and Molecules, Oxford University Press, New York, 1989.

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Montgomery Jr., J. A.; Vreven, T.; Kudin, K.N.; Burant, J.C.; Millam, J.M.; Iyengar, S.S.; Tomasi, J.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Cossi, M.; Scalmani, G.; Rega, N.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Hada, M.; Ehara, M.; Toyota, K.; Fukuda, R.; Hasegawa, J.; Ishida, M.; Nakajima, T.; Honda, Y.; Kitao, O.; Nakai, H.; Klene, M.; Li, X.; Knox, J.E.; Hratchian, H.P.; Cross, J.B.; Bakken, V.; Adamo, C.; Jaramillo, J.; Gomperts, R.; Stratmann, R.E.; Yazyev, O.; Austin, A.J.; Cammi, R.; Pomelli, C.; Ochterski, J.W.; Ayala, P.Y.; Morokuma, K.; Voth, G.A.; Salvador, P.; Dannenberg, J.J.; Zakrzewski, V.G.; Dapprich, S.; Daniels, A.D.; Strain, M.C.; Farkas, O.; Malick, D.K.; Rabuck, A.D.; Raghavachari, K.; Foresman, J.B.; Ortiz, J.V.; Cui, Q.; Baboul, A.G.; Clifford, S.; Cioslowski, J.; Stefanov, B.B.; Liu, G.; Liashenko, A.; Piskorz, P.; Komaromi, I.; Martin, R.L.; Fox, D.J.; Keith, T.; Al-Laham, M.A.; Peng, C.Y.; Nanayakkara, A.; Challacombe, M.; Gill, P.M.W.; Johnson, B.; Chen, W.; Wong, M.W.; Gonzalez, C.; Pople, J.A. Gaussian 03, Revision C.02, Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford CT, 2004.

- Bauschlicher, C.W. A comparison of the accuracy of different functionals. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1995, 246, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (a) Haussermann, U.; Dolg, M.; Stoll, H.; Preuss, H.; Schwerdtfeger, P.; Pitzer, R.M. Accuracy of energy‐adjusted quasirelativistic ab initio pseudopotentials. Mol. Phys. 1993, 78, 1211–1224. https://doi.org/10.1080/00268979300100801 (b) Kuchle, W.; Dolg, M.; Stoll, H.; Preuss, H. Energyadjusted pseudopotentials for the actinides. Parameter sets and test calculations for thorium and thorium monoxide. J. Chem. Phys. 1994, 100, 7535–7542. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.466847 (c) Leininger, T.; Nicklass, A.; Stoll, H.; Dolg, M.; Schwerdtfeger, P. The accuracy of the pseudopotential approximation. II. A comparison of various core sizes for indium pseudopotentials in calculations for spectroscopic constants of InH, InF, and InCl. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 105, 1052–1059. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.471950.

- QikProp, version 2.5, Schrödinger, LLC, New York, NY, 2005.

- Thompson, M.K.; Misselwitz, B.; Tso, L.; Doble, D.M.J.; Schmitt‐Willich, H.; Raymond, K.N. In Vivo Evaluation of Gadolinium Hydroxypyridonate Chelates: Initial Experience as Contrast Media in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 3874‐3877. https://doi.org/10.1021/jm049041m.

- Le Fur, M.; Rotile, N.J.; Correcher, C.; Jordan, V.C.; Ross, A.W.; Catana, C.; Caravan, P. Yttrium‐86 is a Positron Emitting Surrogate of Gadolinium for Noninvasive Quantification of Whole‐Body Distribution of Gadolinium‐Based Contrast Agents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 1474‐1478. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201911858.

- Rossotti, F.J.C.; Rossotti, H. Potentiometric titrations using Gran plots: a textbook omission. J. Chem. Ed. 1965, 42, 375–378. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed042p375.

- Maestro, version 9.3. Schrödinger Inc., Portland, OR, 2012.

| Compound | log Ki | (m,h,l) | log β (GdmHhLl) |

|---|---|---|---|

KEMPPr(3,4-HP)3 |

11.5(4) 10.97(5) 9.87(6) 3.96(7) 3.19(8) 3.04(9) |

(1,4,1) (1,2,1) (1,1,1) (1,0,1) pGd |

41.35(8) 35.17(7) 31.30(4) 26.59(8) 13.2d |

H3L2e |

9.93(2) 9.75(4) 9.18(5) 4.26(5) 3.11(6) 2.77(7) |

(1,4,1) (1,2,1) (1,0,1) pGd |

37.74(4) 30.03(6) 21.22(5) 14.3 |

NTP(PrHP)3 |

9.95f 9.84f 9.09f 6.77f 3.81f 3.14f 2.76f |

(1,5,1) (1,4,1) (1,3,1) (1,2,1) (1,1,1) (1,0,1) (1,5,2) [1,3,2) pGd |

42.8g 39.46g 35.69g 31.16g 26.35g - 65.3g 52.3g 12.3 |

| Species | MWa | HBD/HBAb | PSAc | clog Po/wd | log K (HSA) Bindinge | log BBf | Caco-2 Permeab (nm/s)g | MDCK Permeab(nm/s)h | % Oral Absorpti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KEMP(PrHP)3 | 750.9 | 6/17 | 228.8 | 0.78 | -0.97 | -2.50 | 18 | 21 | 51 |

| Si-KEMP(PrHP)3 | 778.9 | 3/14 | 133.5 | 3.51 | -0.34 | -0.80 | 1212 | 1490 | 93 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).