Submitted:

19 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

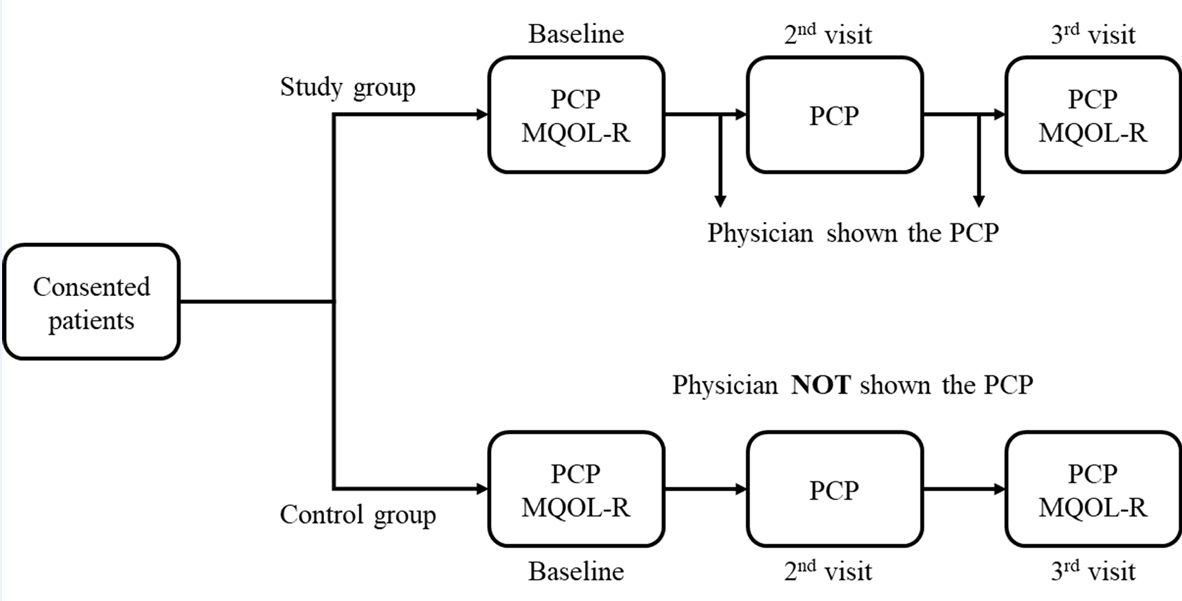

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Particpants

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Study Instruments

2.4.1. Patient Communication Profile (PCP)

2.4.2. The Revised McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (MQOL-R)

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Flow

3.2. Baseline Characteristics

3.3. The PCP

3.4. MQOL-R

3.5. Relationships Between Patients’ QoL and Communicated Medical Information

4. Discussion

5. Study Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gilligan, T.; Coyle, N.; Frankel, R.M.; Berry, D.L.; Bohlke, K.; Epstein, R.M.; Finlay, E.; Jackson, V.A.; Lathan, C.S.; Loprinzi, C.L.; et al. Patient-Clinician Communication: American Society of Clinical Oncology Consensus Guideline. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35, 3618–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Street, R.L.; Makoul, G.; Arora, N.K.; Epstein, R.M. How Does Communication Heal? Pathways Linking Clinician–Patient Communication to Health Outcomes. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 74, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lelorain, S.; Brédart, A.; Dolbeault, S.; Sultan, S. A Systematic Review of the Associations between Empathy Measures and Patient Outcomes in Cancer Care: Associations between Empathy and Outcomes. Psychooncology. 2012, 21, 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, C.; Daly, M.; Walsh, W.P.; Resch, N.; Seay, J.; Barsevick, A.; Heggan, T.; Martin, G.; Birenbaum, L. Communication between Patients with Breast Cancer and Health Care Providers Determinants and Implications. Cancer 1993, 72, 2612–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luo, X.; Cao, Q.; Lin, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, Q. Communication Needs of Cancer Patients and/or Caregivers: A Critical Literature Review. J. Oncol. 2020, 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, W.E.; Levoy, K.; Doyon, K.; McDarby, M.; Ferrell, B.R.; Parker, P.A.; Sanders, J.J.; Epstein, A.S.; Sullivan, D.R.; Rosenberg, A.R. Integrating Evidence-Based Communication Principles into Routine Cancer Care. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, S.M. Monitoring versus Blunting Styles of Coping with Cancer Influence the Information Patients Want and Need about Their Disease. Implications for Cancer Screening and Management. Cancer 1995, 76, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, C.G.; Labrecque, M.S.; Ruckdeschel, J.C.; Blanchard, E.B. Physician Behaviors, Patient Perceptions, and Patient Characteristics as Predictors of Satisfaction of Hospitalized Adult Cancer Patients. Cancer 1990, 65, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, O.; Ham-Baloyi, W.T.; Rooyen, D. (Rm) V.; Aldous, C.; Marais, L.C. Culturally Competent Patient–Provider Communication in the Management of Cancer: An Integrative Literature Review. Glob. Health Action 2016, 9, 33208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glimelius, B.; Birgegård, G.; Hoffman, K.; Kvale, G.; Sjödén, P.-O. Information to and Communication with Cancer Patients: Improvements and Psychosocial Correlates in a Comprehensive Care Program for Patients and Their Relatives. Patient Educ. Couns. 1995, 25, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longacre, M.L.; Galloway, T.J.; Parvanta, C.F.; Fang, C.Y. Medical Communication-Related Informational Need and Resource Preferences Among Family Caregivers for Head and Neck Cancer Patients. J. Cancer Educ. 2015, 30, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wersch, A.; De Boer, M.F.; Van Der Does, E.; De Jong, P.; Knegt, P.; Meeuwis, C.A.; Stringer, P.; Pruyn, J.F.A. Continuity of Information in Cancer Care: Evaluation of a Logbook. Patient Educ. Couns. 1997, 31, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.; Tod, A.M.; Brummell, S.; Collins, K. Prognostic Communication in Cancer: A Critical Interpretive Synthesis of the Literature. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015, 19, 554–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, S.M.; Clayton, J.M.; Hancock, K.; Walder, S.; Butow, P.N.; Carrick, S.; Currow, D.; Ghersi, D.; Glare, P.; Hagerty, R.; et al. A Systematic Review of Prognostic/End-of-Life Communication with Adults in the Advanced Stages of a Life-Limiting Illness: Patient/Caregiver Preferences for the Content, Style, and Timing of Information. J. Pain Symptom Manage. 2007, 34, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson-Barnett, J.; Osborne, J. Studies Evaluating Patient Teaching: Implications for Practice. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 1983, 20, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolley, F.R.; Kane, R.L.; Hughes, C.C.; Wright, D.D. The Effects of Doctor--Patient Communication on Satisfaction and Outcome of Care. Soc. Sci. Med. 1978, 12, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beisecker, A.E.; Beisecker, T.D. Patient Information-Seeking Behaviors When Communicating With Doctors. Med. Care 1990, 28, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butow, P.; Dunn, S.; Tattersall, M.; Jones, Q. Computer-Based Interaction Analysis of the Cancer Consultation. Br. J. Cancer 1995, 71, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, J.G.; Howerton, M.W.; Lai, G.Y.; Gary, T.L.; Bolen, S.; Gibbons, M.C.; Tilburt, J.; Baffi, C.; Tanpitukpongse, T.P.; Wilson, R.F.; et al. Barriers to Recruiting Underrepresented Populations to Cancer Clinical Trials: A Systematic Review. Cancer 2008, 112, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Négrier, S.; Lanier-Demma, F.; Lacroix-Kante, V.; Chauvin, F.; Saltel, P.; Mercatello, A.; Philip, T. Evaluation of the Informed Consent Procedure in Cancer Patients Candidate to Immunotherapy. Eur. J. Cancer 1995, 31, 1650–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rood, J.A.J.; Van Zuuren, F.J.; Stam, F.; Van Der Ploeg, T.; Huijgens, P.C.; Verdonck- De Leeuw, I.M. Cognitive Coping Style (Monitoring and Blunting) and the Need for Information, Information Satisfaction and Shared Decision Making among Patients with Haematological Malignancies. Psychooncology. 2015, 24, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.; Woodruff, R.K. Communicating with Patients with Advanced Cancer. J. Palliat. Care 1997, 13, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, G.; Peterson, V.W.; Lampic, C.; Von Essen, L.; Sjödén, P. Cancer Patient and Staff Ratings of the Importance of Caring Behaviours and Their Relations to Patient Anxiety and Depression. J. Adv. Nurs. 1998, 27, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, S.; Sanson-Fisher, R.W.; Girgis, A.; Bonaventura, A. How Well Do Medical Oncologists’ Perceptions Reflect Their Patients’ Reported Physical and Psychosocial Problems? Data from a Survey of Five Oncologists. Cancer 1998, 83, 1640–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanco, K.; Rhondali, W.; Perez-Cruz, P.; Tanzi, S.; Chisholm, G.B.; Baile, W.; Frisbee-Hume, S.; Williams, J.; Masino, C.; Cantu, H.; et al. Patient Perception of Physician Compassion After a More Optimistic vs a Less Optimistic Message: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2015, 1, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westendorp, J.; Geerse, O.P.; Van Der Lee, M.L.; Schoones, J.W.; Van Vliet, M.H.M.; Wit, T.; Evers, A.W.M.; Van Vliet, L.M. Harmful Communication Behaviors in Cancer Care: A Systematic Review of Patients and Family Caregivers Perspectives. Psychooncology 2023, pon.6247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernacki, R.E.; Block, S.D. Communication About Serious Illness Care Goals: A Review and Synthesis of Best Practices. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butow, P.; Brown, R.; Aldridge, J.; Juraskova, I.; Zoller, P.; Boyle, F.; Wilson, M.; Bernhard, J. Can Consultation Skills Training Change Doctors’ Behaviour to Increase Involvement of Patients in Making Decisions about Standard Treatment and Clinical Trials: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Health Expect. 2015, 18, 2570–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.C. Building Measurement and Data Collection into Medical Practice. Ann. Intern. Med. 1998, 128, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puts, M.T.E.; Tapscott, B.; Fitch, M.; Howell, D.; Monette, J.; Wan-Chow-Wah, D.; Krzyzanowska, M.; Leighl, N.B.; Springall, E.; Alibhai, S.M. A Systematic Review of Factors Influencing Older Adults’ Decision to Accept or Decline Cancer Treatment. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2015, 41, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydarnejad, M.S.; Hassanpour, D.A.; Solati, D.K. Factors Affecting Quality of Life in Cancer Patients Undergoing Chemotherapy. Afr. Health Sci. 2011, 11, 266–270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thorne, S.; Hislop, T.G.; Kim-Sing, C.; Oglov, V.; Oliffe, J.L.; Stajduhar, K.I. Changing Communication Needs and Preferences across the Cancer Care Trajectory: Insights from the Patient Perspective. Support. Care Cancer 2014, 22, 1009–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Bos, G.; Triemstra, A. Quality of Life as an Instrument for Need Assessment and Outcome Assessment of Health Care in Chronic Patients. Qual. Saf. Health Care 1999, 8, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.R.; Sawatzky, R.; Russell, L.B.; Shahidi, J.; Heyland, D.K.; Gadermann, A.M. Measuring the Quality of Life of People at the End of Life: The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire–Revised. Palliat. Med. 2017, 31, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratheepawanit, N. Incorporation of Quality of Life Assessment in Routine Practice as an Aid to Clinical Decision-Making. PhD thesis, University of Wales, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S.R.; Mount, B.M.; Bruera, E.; Provost, M.; Rowe, J.; Tong, K. Validity of the McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire in the Palliative Care Setting: A Multi-Centre Canadian Study Demonstrating the Importance of the Existential Domain. Palliat. Med. 1997, 11, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohammadi, A.; Salek, M.S.; Maughan, T.; Mason, M.; Nicholls, P.J. The Impact of Routine Assessment of Information Needs on HRQoL of Patients with Cancer. Qual. Life Res. 2003, 12, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohammadi, A. Development and Validation of a Medical Information Needs and Outcomes Assessment Tool for Patients with Cancer. PhD Thesis, University of Cardiff, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Mokkink, L.B.; Terwee, C.B.; Patrick, D.L.; Alonso, J.; Stratford, P.W.; Knol, D.L.; Bouter, L.M.; de Vet, H.C.W. The COSMIN Checklist for Assessing the Methodological Quality of Studies on Measurement Properties of Health Status Measurement Instruments: An International Delphi Study. Qual. Life Res. Int. J. Qual. Life Asp. Treat. Care Rehabil. 2010, 19, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouelhi, Y.; Jouve, E.; Castelli, C.; Gentile, S. How Is the Minimal Clinically Important Difference Established in Health-Related Quality of Life Instruments? Review of Anchors and Methods. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2020, 18, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Crotty, K. Low Health Literacy and Health Outcomes: An Updated Systematic Review. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011, 155, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, C.G.; Labrecque, M.S.; Ruckdeschel, J.C.; Blanchard, E.B. Information and Decision-Making Preferences of Hospitalized Adult Cancer Patients. Soc. Sci. Med. 1988, 27, 1139–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaturvedi, S.K.; Strohschein, F.J.; Saraf, G.; Loiselle, C.G. Communication in Cancer Care: Psycho-Social, Interactional, and Cultural Issues. A General Overview and the Example of India. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimori, M.; Uchitomi, Y. Preferences of Cancer Patients Regarding Communication of Bad News: A Systematic Literature Review. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 39, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothenbacher, D.; Lutz, M.P.; Porzsolt, F. Treatment Decisions in Palliative Cancer Care: Patients’ Preferences for Involvement and Doctors’ Knowledge about It. Eur. J. Cancer 1997, 33, 1184–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynia, M.K.; Osborn, C.Y. Health Literacy and Communication Quality in Health Care Organizations. J. Health Commun. 2010, 15, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodd, M.J. Assessing Patient Self-Care for Side Effects of Cancer Chemotherapy--Part I. Cancer Nurs. 1982, 5, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walling, A.; Lorenz, K.A.; Dy, S.M.; Naeim, A.; Sanati, H.; Asch, S.M.; Wenger, N.S. Evidence-Based Recommendations for Information and Care Planning in Cancer Care. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 3896–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWilliam, C.L.; Brown, J.B.; Stewart, M. Breast Cancer Patients’ Experiences of Patient–Doctor Communication: A Working Relationship. Patient Educ. Couns. 2000, 39, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butow, P.N.; Dunn, S.M.; Tattersall, M.H.N.; Jones, Q.J. Patient Participation in the Cancer Consultation: Evaluation of a Question Prompt Sheet. Ann. Oncol. 1994, 5, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, J.M.; Hancock, K.M.; Butow, P.N.; Tattersall, M.H.N.; Currow, D.C. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Communicating Prognosis and End-of-life Issues with Adults in the Advanced Stages of a Life-limiting Illness, and Their Caregivers. Med. J. Aust. 2007, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, E.L.; Corner, G.W.; De Rosa, A.; Breitbart, W.; Applebaum, A.J. Prognostic Awareness and Communication of Prognostic Information in Malignant Glioma: A Systematic Review. J. Neurooncol. 2014, 119, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vries, A.M.M.; De Roten, Y.; Meystre, C.; Passchier, J.; Despland, J.-N.; Stiefel, F. Clinician Characteristics, Communication, and Patient Outcome in Oncology: A Systematic Review. Psychooncology. 2014, 23, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodd, M.J. Measuring Informational Intervention for Chemotherapy Knowledge and Self-Care Behavior. Res. Nurs. Health 1984, 7, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillen, M.A.; De Haes, H.C.J.M.; Stalpers, L.J.A.; Klinkenbijl, J.H.G.; Eddes, E.H.; Butow, P.N.; Van Der Vloodt, J.; Van Laarhoven, H.W.M.; Smets, E.M.A. How Can Communication by Oncologists Enhance Patients’ Trust? An Experimental Study. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 896–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Pearson, J.; McGregor, S.; Gilmour, W.H.; Atkinson, J.M.; Barrett, A.; Cawsey, A.J.; McEwen, J. Cross Sectional Survey of Patients’ Satisfaction with Information about Cancer. BMJ 1999, 319, 1247–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steptoe, A.; Sutcliffe, I.; Allen, B.; Coombes, C. Satisfaction with Communication, Medical Knowledge, and Coping Style in Patients with Metastatic Cancer. Soc. Sci. Med. 1991, 32, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggers, J.H.; Donovan, K.O.; Redman, S.; Sanson-Fisher, R.W. Cancer Patient Satisfaction with Care. Cancer 1990, 66, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimori, M.; Shirai, Y.; Asai, M.; Kubota, K.; Katsumata, N.; Uchitomi, Y. Effect of Communication Skills Training Program for Oncologists Based on Patient Preferences for Communication When Receiving Bad News: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2166–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodin, G.; Zimmermann, C.; Mayer, C.; Howell, D.; Katz, M.; Sussman, J.; Mackay, J.A.; Brouwers, M. Clinician–Patient Communication: Evidence-Based Recommendations to Guide Practice in Cancer. Curr. Oncol. 2009, 16, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, L.M.L.; De Haes, J.C.J.M.; Hoos, A.M.; Lammes, F.B. Doctor-Patient Communication: A Review of the Literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 1995, 40, 903–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, F.A.; Barry, C.A.; Britten, N.; Barber, N.; Bradley, C.P. Doctor–Patient Communication about Drugs: The Evidence for Shared Decision Making. Soc. Sci. Med. 2000, 50, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molleman, E.; Krabbendam, P.J.; Annyas, A.A.; Koops, H.S.; Sleijfer, D.Th.; Vermey, A. The Significance of the Doctor-Patient Relationship in Coping with Cancer. Soc. Sci. Med. 1984, 18, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total (n = 105) | Control (n = 41) | Study (n = 64) | p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age(years) | ||||

| Mean | 57.96 | 58.32 | 57.73 | 0.828 |

| Range | 18-88 | 18-80 | 26-88 | |

| 18-44 | 15 (14.3) | 6 (14.6) | 9 (14.1) | |

| 45-64 | 53 (50.5) | 21 (51.2) | 32 (50.0) | |

| ≥65 | 37 (35.2) | 14 (34.1) | 23 (35.9) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 45 (43) | 15 (37) | 30 (47) | 0.320 |

| Female | 60 (57) | 26 (63) | 34 (53) | |

| Education | ||||

| Further | 36 (38) | 14 (39) | 22 (37) | 1.000 |

| No further | 59 (62) | 22 (61) | 37 (63) | |

| Cancer site | ||||

| Breast | 23 (21.9%) | 8 (19.5) | 15 (23.4) | 0.236 |

| Urogenital | 10 (9.5%) | 2 (4.9) | 8 (12.5) | |

| Lymphoma | 22 (21.0%) | 7 (17.1) | 15 (23.4) | |

| GIT | 26 (24.8%) | 14 (34.1) | 12 (18.8) | |

| Gynaecological | 18 (17.1%) | 7 (17.1) | 11 (17.2) | |

| Brain | 04 (3.8%) | 1 (2.4) | 3 (4.7) | |

| Other | 02 (1.9%) | 2 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Illness status | ||||

| Advanced | 66 (62.5%) | 23 (64) | 43 (72) | 0.497 |

| Not advanced | 30 (37.5%) | 13 (36) | 17 (28) |

| PCP and MQOL-R Domains | Control | Study | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Source of information preferred: | |||

| One source preferred | 21 (51) | 36 (56) | 0.690 |

| More than one source preferred | 20 (49) | 28 (44) | |

| Method of information preferred: | |||

| One method preferred | 23 (56) | 36 (56) | 1.000 |

| More than one method preferred | 18 (44) | 28 (44) | |

| Preferences for involvement in treatment decision-making: |

|||

| Passive | 14 (34) | 18 (28) | 0.523 |

| Active | 27 (66) | 46 (72) | |

| Domains | Median (range) | ||

| Information needs (A) | 3.64 (1.50-4) | 3.71 (1.57-4) | 0.272 |

| Satisfaction with the amount of information (B) | 3.78 (2.22-4) | 3.67 (1.67-4) | 0.567 |

| Understanding of information (C) | 3.50 (2.00-4) | 3.56 (1.50-4) | 0.610 |

| Satisfaction with the quality of information (D) | 3.90 (2.50-4) | 3.90 (2.40-4) | 0.857 |

| Mental distress (E) | 2.00 (1.00-4) | 3.00 (1.00-4) | 0.636 |

| MQOL-R | Median (range) | ||

| Overall quality of life | 7.00 (1.00-10) | 7.00 (1.00-10) | 0.906 |

| Physical symptoms | 6.00 (0.33-10) | 7.66 (1.33-10) | 0.160 |

| Physical well being | 7.00 (0.00-10) | 7.00 (0.00-10) | 0.419 |

| Psychological domain | 8.25 (0.25-10) | 7.75 (0.00-10) | 0.277 |

| Existential domain | 7.67 (0.33-10) | 7.58 (0.83-10) | 0.461 |

| Support domain | 9.00 (4.00-10) | 9.00 (1.00-10) | 0.769 |

| Total MQOL-R | 7.00 (1.13-9.9) | 7.35 (2.88-10) | 0.791 |

| Control | Study | p-value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (range) | Mean (SD) | Median (range) | ||

| Domain A | Patients’ need for information | ||||

| Baseline | 3.52 (0.51) | 3.64 (1.50-4) | 3.56 (0.53) | 3.71 (1.57-4) | 0.272 |

| Visit 2 | 3.52 (0.52) | 3.71 (2.07-4) | 3.61 (0.40) | 3.75 (2.36-4) | 0.478 |

| Visit 3 | 3.50 (0.48) | 3.57 (1.93-4) | 3.59 (0.51) | 3.79 (1.64-4) | 0.107 |

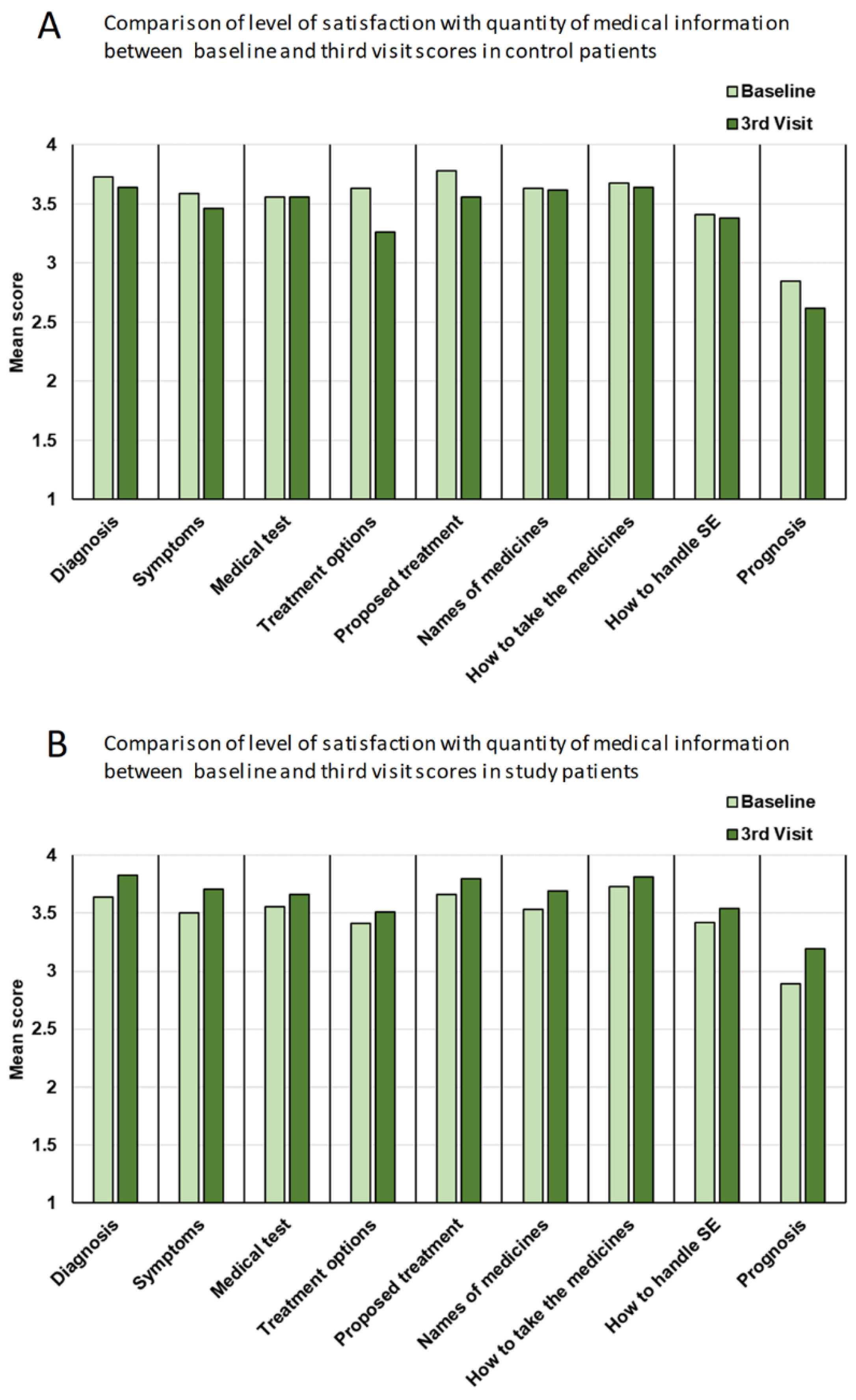

| Domain B | Patients’ satisfaction with the quantity of medical information | ||||

| Baseline | 3.54 (0.53) | 3.77 (2.22-4) | 3.48 (0.58) | 3.66 (1.67-4) | 0.567 |

| Visit 2 | 3.42 (0.53) | 3.66 (2.11-4) | 3.52 (0.53) | 3.78 (1.78-4) | 0.211 |

| Visit 3 | 3.42 (0.55) | 3.66 (2.33-4) | 3.64 (0.46) | 3.89 (2.22-4) | 0.018 |

| Domain C | Patients’ understanding of information | ||||

| Baseline | 3.34 (0.59) | 3.50 (2.00-4) | 3.38 (0.63) | 3.56 (1.50-4) | 0.610 |

| Visit 2 | 3.30 (0.57) | 3.38 (2.25-4) | 3.45 (0.60) | 3.63 (1.75-4) | 0.084 |

| Visit 3 | 3.27 (0.58) | 3.12 (2.38-4) | 3.47 (0.53) | 3.63 (2.00-4) | 0.072 |

| Domain D | Patients’ satisfaction with the quality of information | ||||

| Baseline | 3.68 (0.48) | 3.90 (2.50-4) | 3.69 (0.45) | 3.90 (2.40-4) | 0.857 |

| Visit 2 | 3.51 (0.53) | 3.70 (2.30-4) | 3.75 (0.38) | 3.95 (2.30-4) | 0.018 |

| Visit 3 | 3.53 (0.47) | 3.70 (2.50-4) | 3.72 (0.51) | 4.00 (1.40-4) | 0.017 |

| Domain E | Patients’ mental stress | ||||

| Baseline | 2.37 (0.92) | 2.00 (1.00-4) | 2.40 (0.77) | 3.00 (1.00-4) | 0.636 |

| Visit 2 | 2.27 (0.90) | 2.00 (1.00-4) | 2.22 (0.84) | 2.00 (1.00-4) | 0.967 |

| Visit 3 | 2.26 (0.85) | 2.00 (1.00-4) | 2.25 (0.84) | 2.00 (1.00-4) | 0.865 |

| Type of information | Control | Study | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline$ | 3rd visit$ | z# | p-value* | Baseline$ | 3rd visit$ | z# | p-value* | |

| Domain B | Comparison of the impact of the intervention on patients’ satisfaction with the amount of information receieved on various aspects of treatment | |||||||

| Diagnosis | 3.73 | 3.64 | -0.83 | 0.202 | 3.64 | 3.83 | +2.13 | 0.016 |

| Symptoms | 3.59 | 3.46 | -1.00 | 0.158 | 3.50 | 3.71 | +2.29 | 0.011 |

| Medical test | 3.56 | 3.56 | +0.27 | 0.391 | 3.56 | 3.66 | +1.36 | 0.087 |

| Treatment options | 3.63 | 3.26 | -2.84 | 0.002 | 3.41 | 3.51 | +0.82 | 0.206 |

| Proposed treatment | 3.78 | 3.56 | -2.31 | 0.011 | 3.66 | 3.80 | +1.79 | 0.037 |

| Names of medicines | 3.63 | 3.62 | -0.03 | 0.487 | 3.53 | 3.69 | +2.52 | 0.006 |

| How to take the medicines | 3.68 | 3.64 | -0.42 | 0.337 | 3.73 | 3.81 | +1.43 | 0.076 |

| How to handle side-effects | 3.41 | 3.38 | -0.00 | 0.500 | 3.42 | 3.54 | +1.62 | 0.053 |

| Prognosis | 2.85 | 2.62 | -1.25 | 0.106 | 2.89 | 3.19 | +1.78 | 0.037 |

| Domain C | Effects of the intervention on patients’ understanding of each type of information | |||||||

| Diagnosis | 3.51 | 3.49 | 0.000 | 0.500 | 3.59 | 3.61 | 0.000 | 0.500 |

| How diagnosed | 3.49 | 3.56 | +0.943 | 0.173 | 3.69 | 3.64 | -0.254 | 0.400 |

| Medical test | 3.32 | 3.31 | +0.218 | 0.413 | 3.45 | 3.54 | +1.034 | 0.150 |

| Treatment | 3.59 | 3.46 | -1.000 | 0.158 | 3.53 | 3.64 | +1.410 | 0.079 |

| Other available treatment | 2.85 | 2.64 | -0.813 | 0.208 | 2.84 | 2.88 | +0.601 | 0.274 |

| Names of medicines | 3.24 | 3.21 | -0.166 | 0.434 | 3.30 | 3.44 | +1.621 | 0.052 |

| How to handle side-effects | 3.27 | 3.13 | -1.291 | 0.098 | 3.19 | 3.42 | +2.241 | 0.012 |

| The current state of illness | 3.49 | 3.33 | -1.116 | 0.132 | 3.44 | 3.56 | +1.073 | 0.141 |

| Domain D |

Comparisons of the impact of intervention on the patients’ level of satisfaction with the quality of various aspects of information received |

|||||||

| Opportunity to ask questions | 3.68 | 3.56 | -1.43 | 0.076 | 3.69 | 3.81 | +2.07 | 0.019 |

| Express feelings | 3.66 | 3.56 | -1.21 | 0.112 | 3.53 | 3.66 | +1.93 | 0.027 |

| Caring answers | 3.80 | 3.67 | -2.11 | 0.017 | 3.81 | 3.85 | +0.64 | 0.261 |

| Given enough time | 3.59 | 3.62 | -0.24 | 0.404 | 3.70 | 3.76 | +0.84 | 0.201 |

| Honest information | 3.83 | 3.69 | -1.25 | 0.106 | 3.89 | 3.80 | -1.51 | 0.065 |

| Given all the available information | 3.66 | 3.54 | -1.08 | 0.141 | 3.72 | 3.75 | +0.37 | 0.356 |

| Satisfactory explanation of the treatment | 3.76 | 3.54 | -2.50 | 0.006 | 3.77 | 3.73 | -0.25 | 0.402 |

| Involvement in decision-making | 3.68 | 3.31 | -2.36 | 0.009 | 3.64 | 3.51 | -1.36 | 0.087 |

| Feeling informed | 3.66 | 3.54 | -1.15 | 0.125 | 3.64 | 3.71 | +0.78 | 0.219 |

| Feeling reassured | 3.44 | 3.31 | -1.53 | 0.063 | 3.55 | 3.63 | +0.76 | 0.224 |

| Domain E | Comparisons of the impact of intervention on patients’ mental distress | |||||||

| Visit 2 | -0.853 | 0.197 | -2.01 | 0.022 | ||||

| Visit 3 | -0.688 | 0.245 | -1.37 | 0.085 | ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | Active | Passive | p-value* |

| Overall | 6.90 (2.39) | 6.69 (2.06) | 0.553 |

| Physical symptoms | 6.98 (2.75) | 6.35 (2.95) | 0.295 |

| Physical well being | 6.94 (2.34) | 6.32 (2.40) | 0.277 |

| Psychological | 7.60 (2.73) | 6.50 (2.94) | 0.068 |

| Existential | 7.65 (2.06) | 7.11 (2.16) | 0.179 |

| Support | 9.12 (1.26) | 8.48 (1.92) | 0.145 |

| Total MQOL-R | 7.68 (1.47) | 6.95 (1.69) | 0.049 |

| Lower needs | Higher needs | ||

| Overall | 8.14 (1.95) | 6.65 (2.14) | 0.094 |

| Physical symptoms | 7.86 (2.23) | 6.45 (2.92) | 0.151 |

| Physical well being | 7.57 (3.05) | 6.43 (2.33) | 0.207 |

| Psychological | 9.29 (0.83) | 6.66 (2.93) | 0.015 |

| Existential | 8.17 (1.42) | 7.20 (2.17) | 0.306 |

| Support | 9.07 (1.24) | 8.64 (1.81) | 0.703 |

| Total MQOL-R | 8.39 (1.19) | 7.08 (1.65) | 0.033 |

| ‡Less satisfied | More satisfied | ||

| Overall | 6.00 (2.24) | 6.91 (2.12) | 0.116 |

| Physical symptoms | 5.41 (2.95) | 6.77 (2.84) | 0.017 |

| Physical well being | 5.76 (2.75) | 6.66 (2.30) | 0.110 |

| Psychological | 6.88 (2.85) | 6.83 (2.94) | 0.522 |

| Existential | 6.43 (2.76) | 7.44 (1.97) | 0.104 |

| Support | 7.62 (2.55) | 8.88 (1.50) | 0.011 |

| Total MQOL-R | 6.42 (2.18) | 7.32 (1.50) | 0.028 |

| Low understanding | High understanding | ||

| Overall | 5.74 (2.32) | 7.05 (2.02) | 0.011 |

| Physical symptoms | 5.64 (2.87) | 6.81 (2.86) | 0.105 |

| Physical well being | 5.78 (2.70) | 6.72 (2.26) | 0.129 |

| Psychological | 6.45 (2.86) | 6.95 (2.93) | 0.336 |

| Existential | 6.44 (2.65) | 7.51 (1.92) | 0.093 |

| Support | 7.89 (2.35) | 8.90 (1.50) | 0.052 |

| Total MQOL-R | 6.44 (1.94) | 7.38 (1.50) | 0.027 |

| ‡‡Less satisfied | More satisfied | ||

| Overall | 6.00 (2.16) | 6.84 (2.15) | 0.194 |

| Physical symptoms | 5.73 (2.57) | 6.63 (2.92) | 0.329 |

| Physical well being | 6.30 (1.95) | 6.53 (2.44) | 0.527 |

| Psychological | 5.80 (2.84) | 6.95 (2.91) | 0.142 |

| Existential | 5.82 (2.37) | 7.43 (2.06) | 0.024 |

| Support | 7.15 (2.82) | 8.84 (1.55) | 0.039 |

| Total MQOL-R | 6.16 (1.72) | 7.28 (1.62) | 0.047 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).