1. Introduction

Instrumented gait analysis provides comprehensive data on both normal and pathological gait, offering objective tools that are valuable for clinical assessment. Surface electromyography (EMG), a primary non-invasive technique, records muscle electrical activity during walking and has shown significant benefits for clinical decision-making [

1,

2,

3,

4]. However, interpreting EMG results requires clinicians to have reliable reference data to accurately identify abnormal activation patterns and guide treatment strategies [

5]. In a Delphi survey, experts reached a consensus that a sample size of 20 may be sufficient to establish a clinical norm band [

6]. They also recommended that this data should include healthy individuals both below and above eight years of age, as these age groups likely exhibit different EMG patterns. Schwartz et al. [

7] published normative gait and EMG data for 83 children (ages 4-17) across a range of walking speeds. Bovi et al. [

8] aimed to expand this research by including adults and exploring various gait analysis protocols. However, their study was limited by a sample size of 40 participants (20 in each age group) and did not specifically examine factors like gender.

Extensive research has established distinct gait characteristics between adult males and females, highlighting significant differences in walking patterns. Females generally display higher cadence, shorter step length, and similar gait speed compared to males [

9,

10]. Gender-related differences in joint kinematics and kinetics during walking include greater hip flexion, reduced knee extension before initial contact, lower knee and ankle torque in midstance, and increased knee flexion, knee extension torque at terminal stance, along with a higher knee flexion moment and power during pre-swing [

11]. These findings suggest that gender affects motion and joint loading in gait; however, these differences may also vary with age. For example, ankle dorsiflexion duration in initial swing tends to increase more steeply with age in females than in males [

12]. Age-related gait changes extend further, including longer stance time with slower walking, decreased ankle plantar flexor moment at push-off, and increased peak hip extensor moment during early stance [

13,

14].

While age- and gender-related changes in gait functions are well-documented, the underlying factors driving these changes remain poorly understood. Some studies suggest that these gender-dependent differences may be partially attributed to variations in muscle recruitment patterns. Di Nardo et al. [

15,

16] observed higher activation of the tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius lateralis within a single gait stride in adult females, whereas this activation was absent in children aged 6-8. They propose that this difference may reflect the influence of motor control development with age on EMG patterns. Schmitz et al. [

17] specifically examined the effect of age on the activation patterns of lower body muscles during gait and found increased gastrocnemius lateralis activation during the loading response in younger adults, alongside greater activity of the vastus lateralis, soleus, and rectus femoris during mid-stance. They attributed these differences to higher ankle joint stiffness and altered stabilizing strategies in older adults. In a comprehensive study, Bailey et al. [

12] examined the interactive effects of age and sex on EMG in 93 healthy adults, revealing a correlation between higher rectus femoris activation in males and greater gastrocnemius lateralis activation in females during mid-swing, with both variables showing age-related changes. However, their study was limited to adults (aged >20), excluding children, while other studies have shown that children may exhibit significantly different EMG patterns due to the ongoing development of motor control, particularly in females [

15,

16]. Therefore, there is a need for further investigation into the effect of age, specifically comparing children and adults, as a factor in studying the influence of gender on neuromuscular control of gait. Additionally, most of the existing literature has focused on specific phases of gait, while methodologies like statistical parametric mapping (SPM,

www.spm1d.org) [

18] allow for analysis across the entire gait cycle, addressing the limitations of previous studies by preventing the missing of critical information.

To our knowledge, no study has systematically examined the interaction between age and gender on lower limb muscle activation during gait using a comprehensive EMG dataset that includes children. A secondary aim of our study is to determine the minimum sample size needed in a reference dataset to effectively capture these influences, thereby enhancing the clinical applicability of EMG interpretations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the local Ethical Committee “Medical Faculty, Heidelberg University (no: S-243/2022)”.

2.2. Participants

The data analyzed in this study were part of a larger database established at the local University Clinics between 2000 and 2024, comprising data from more than 350 typically developing (TD) individuals. All healthy participants had no history of motor pathology. The primary inclusion criterion for this study was the availability of both EMG and gait data. Based on this criterion, 108 subjects were initially selected and categorized into three age groups: children (aged <13, thirty-five subjects), juveniles (aged 13–18, eleven subjects), and adults (aged >18, sixty-two subjects). Due to the significantly smaller sample size in the juvenile group compared to the other groups, these individuals were excluded from further analysis. As a result, a total of 97 typically developing individuals were included in the study. The demographic details of the participants are provided in

Table 1. Each participant was informed about the study’s purpose and provided written informed consent.

2.3. Instrumentation and Protocol

All participants walked barefoot at a self-selected speed along a 15-meter walkway during data acquisition. Kinematic and kinetic data were recorded using a twelve-camera 3D motion analysis system (VICON, Oxford Metrics Limited, UK) operating at 120 Hz and three force plates (Kistler Instruments Co.). Skin-mounted markers were placed according to the protocol of Kadaba et al. [

19], and the plug-in-gait model was used for analysis. Gait parameters were determined from at least seven strides per participant.

EMG data were collected from seven major lower-extremity muscles: tibialis anterior (TIB), soleus (SOL), gastrocnemius (GAS), rectus femoris (REF), vastus lateralis (VAS), biceps femoris (BIC), and semimembranosus (SEM) of both legs. Data acquisition was performed using the Myon 320 system (Myon AG, Schwarzenberg, CH). Bipolar surface adhesive electrodes (Blue Sensor, Ambu Inc., Glen Burnie, MD, USA) were placed on the target muscles following SENIAM guidelines [

20], with an inter-electrode distance of 2 cm [

21]. To amplify the EMG signal, the Biovision EMG apparatus (Biovision Inc., Wehrheim, Germany) was used before 2013/14, and Delsys systems (Delsys Inc., Natick, MA, USA) were used after 2013/14, with a preamplification factor of ×5000.

2.4. Signal Processing

Raw EMG signals were processed as follows: band-pass filtering (Butterworth filter, cutoff frequency: 20–350 Hz), rectification, smoothing (Butterworth low-pass filter, cutoff frequency: 9 Hz), amplitude normalization to the mean signal, and time normalization to one gait cycle (101 data points). The processed data were then averaged across valid strides using MATLAB (2018b, The MathWorks, Inc., USA) [

21]. The peak value of the time series and its occurrence within the gait cycle, along with the mean values over the entire cycle, were calculated. Additionally, these features were analyzed in relation to time by computing them for the full stride, as well as separately for the stance and swing phases [

22].

To support the findings from EMG envelopes, additional kinematic, kinetic, and spatiotemporal (ST) parameters—namely cadence, walking speed, stride time, stride length, and foot-off time—were calculated from the gait data to examine differences between age and gender groups. Additionally, the gait data included the peak angles, moments, and power at the ankle, knee, and hip joints in the sagittal plane (flexion-extension/dorsiflexion-plantarflexion).

2.5. Statistical analysis

We used SPM technique (version: M.0.4.10) implemented in MATLAB [

18] to compare the EMG envelopes of each muscle across age and gender groups throughout the gait cycle. This method treats the data as continuous time-series, maintaining the temporal structure of muscle activation patterns during the entire cycle. SPM(t) evaluates the data at every time point within the gait cycle, detecting significant differences between age groups (children vs. adults) and gender groups (males vs. females). The results (SPM{t}) reveal the specific regions of the gait cycle where statistically significant differences occur, emphasizing phases where age and gender notably influence muscle activation. By eliminating the need to divide the gait cycle into predefined phases, SPM provides a more detailed and holistic analysis of time-dependent variations in muscle activity.

Following the SPM analysis for the effects of age and gender, gait and spatiotemporal (ST) parameters were examined using repeated measures MANOVA, with the significance level set at p = 0.05. Furthermore, the interaction effect between age and gender on EMG features was also assessed using repeated measures MANOVA, followed by post-hoc analyses with Bonferroni correction, adjusting the significance level to p = 0.0125. For variables showing a significant interaction effect, the effect size (Cohen’s f²) was calculated to quantify the magnitude of the observed differences. Additionally, to determine the minimum sample size required for establishing an EMG reference dataset that accounts for the influence of both age and gender on the patterns, we used G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7; Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Germany;

http://www.gpower.hhu.de). The test family was set as F tests, with the statistical test defined as “MANOVA: Special effects and interactions”, an alpha level of 0.0125, and power of 0.8. The highest calculated effect size was included in the analysis to ensure robust sample size estimation. The number of groups was set at 4, since we had two gender groups × two age groups, and also the number of predictions at 3 (age, gender and interaction).

3. Results

No significant differences in height, weight, or BMI were observed between males and females within the children’s age group. However, in the adult group, all parameters demonstrated significant differences (p < 0.001), with males being taller and having higher weight and BMI compared to females.

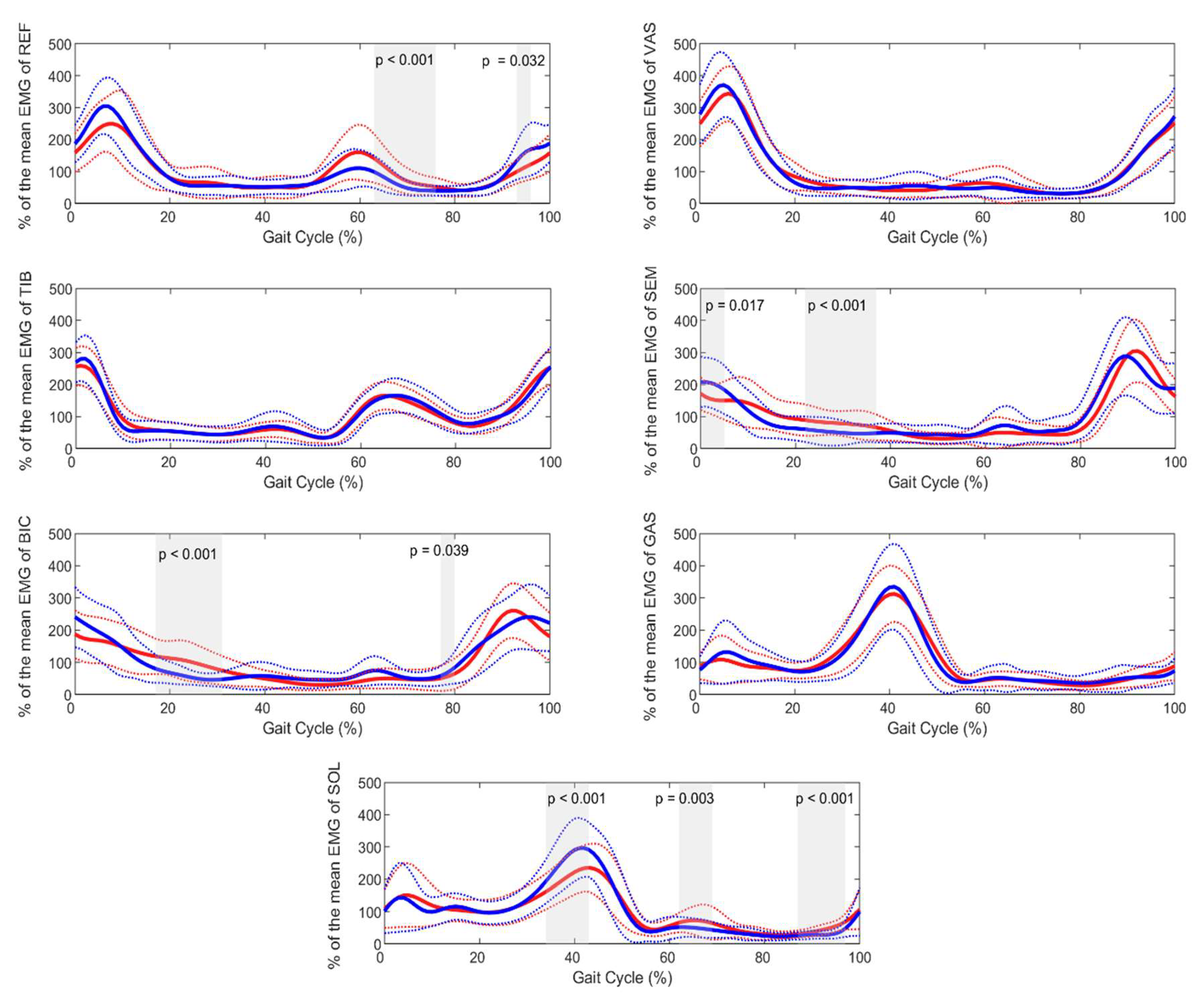

The SPM analysis for the effect of age (

Figure 1) indicates that the main differences in EMG activity between children and adults occurred during the mid-stance phase of the gait cycle for the biceps femoris (17–31% of the gait cycle, p < 0.001) and 77–80% (p = 0.039). Additionally, significant differences were observed for the semimembranosus during the first 5% of the gait cycle (p = 0.017) and 22–37% (p < 0.001); for the rectus femoris during 63–76% (p < 0.001) and 93–96% (p = 0.032); and for the soleus during 34–43% (p < 0.001), 62–69% (p = 0.003), and 87–94% (p < 0.001).

Table 2 presents the mean and standard deviation (SD) of the gait and spatiotemporal characteristics across different age groups. The effect of age on both peak ankle dorsiflexion moment and power was statistically significant (p < 0.001), with higher values observed in adults. A similar effect was found for peak plantarflexion power (p = 0.012) and knee flexion moment (p = 0.004). However, children exhibited higher hip flexion and cadence during gait, as well as lower values for hip extension moment, walking speed, stride time, and stride length.

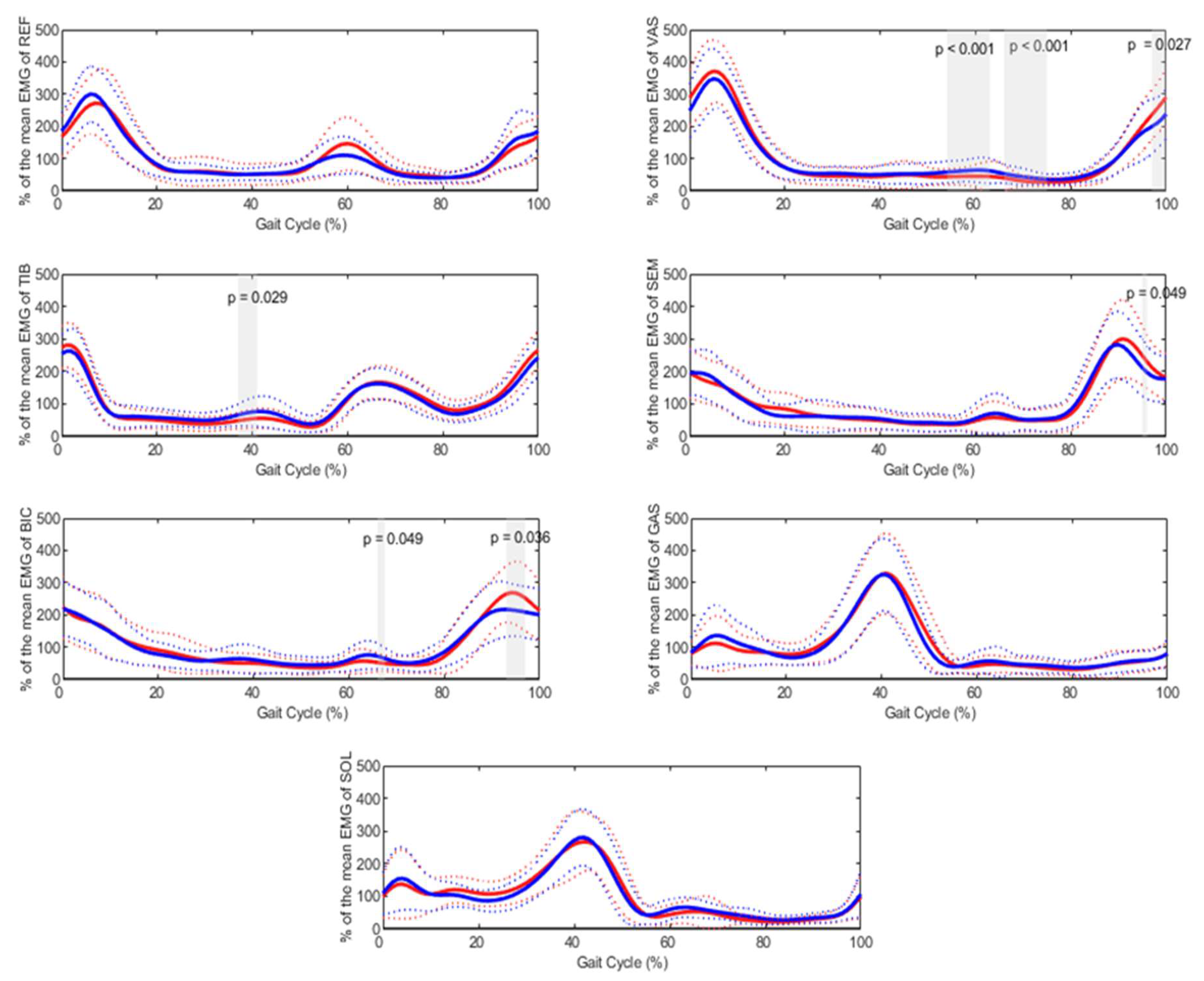

The gender effect, also analyzed using SPM (

Figure 2), revealed significant differences for the biceps femoris during 66–68% of the gait cycle (p = 0.049) and 93–97% (p = 0.036). For the semimembranosus, significant differences were observed at approximately 95% of the gait cycle (p = 0.049), and for the tibialis anterior, between 37–41% (p = 0.029). The vastus lateralis exhibited the longest durations of significant differences, occurring during 54–63% (p < 0.001), 66–75% (p < 0.001), and 97–100% (p = 0.029) of the gait cycle. The influence of gender on gait measures was also significant, with females showing a higher plantarflexion angle (p = 0.023) and larger dorsiflexion power (p = 0.041) at the ankle compared to males. Additionally, females exhibited an increased peak of hip flexion, greater hip extension power, and an earlier foot-off phase.

The comparison of the age-gender interaction effect on EMG features revealed significant differences in the mean EMG activity of the biceps femoris during both stance (p = 0.002) and swing (p < 0.001), as well as peak activity during swing (p < 0.001). The interaction effect on the semimembranosus during both stance (p = 0.006) and swing (p = 0.006) was also significant. In examining the averages, male children exhibited higher biceps femoris activity during stance compared to female children (90.4 vs. 81.9), while in adults, females demonstrated higher biceps femoris activity than males (88.1 vs. 79.1). A similar pattern was observed for the semimembranosus during stance: male children showed higher activity than female children (85.1 vs. 76.2), but in adulthood, activity decreased in males (71.2) while it increased in females (78.6). During the swing phase, the mean and peak EMG activity of the biceps femoris decreased with growth in females, while in males, it increased. A similar growth effect was observed for the semimembranosus in both genders.

To perform the power analysis on the extracted EMG features that demonstrated a significant interaction effect, the effect size was calculated (

Table 4). The biceps femoris maximum activity during the swing phase showed the largest effect size (f² = 0.199). With an alpha level of 0.0125, a power level of 0.80, and five response variables, the total sample size required, based on the largest effect size, was determined to be 47. Therefore, a minimum of 47 subjects is necessary to adequately capture the age- and gender-related differences in the EMG data of the normative population studied. Ideally, this sample size of 47 should be evenly distributed across the four age-gender groups to ensure a balanced representation of children, adults, males, and females, with approximately 12 subjects per group (male children, female children, male adults, and female adults). Our dataset consists of 97 subjects, with more than 12 subjects in each group, indicating that the sample size is sufficient to reliably detect the interaction effect.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to quantify age- and gender-related differences in lower-limb myoelectric activity during walking in typically developing individuals. By applying the SPM approach to EMG envelopes, we were able to capture differences across the entire gait cycle, preserving important information that could be lost through averaging. To further explore these differences, we conducted an analysis of the interaction effect between age and gender, followed by a power analysis to determine the minimum number of subjects required for establishing comprehensive reference data in the clinic.

The observed differences in gait mechanics between children and adults highlight distinct neuromuscular strategies influenced by developmental factors. Children exhibited a higher cadence but lower walking speed, shorter stride time, and reduced stride length, accompanied by increased peak hip flexion and greater activation of the rectus femoris in initial swing and the hamstrings in mid-stance. A higher cadence with shorter strides reflects a reliance on more frequent, smaller steps to maintain stability and forward progression, a common characteristic of developing gait patterns [

23]. The increased peak hip flexion likely aids in advancing the limb during swing, compensating for the shorter stride length. This is supported by the heightened rectus femoris activation in initial swing, which plays a crucial role in lifting and accelerating the limb forward [

24]. The greater hamstring activation in mid-stance suggests an increased demand for knee stability and control [

25]. Given children's relatively weaker musculature and ongoing neuromuscular maturation, the hamstrings may play a compensatory role in stabilizing the knee and modulating joint moments to accommodate their altered gait mechanics.

In contrast, adults exhibited different EMG and gait patterns, characterized by greater activation of the semimembranosus during initial contact, soleus during push-off, and rectus femoris during late swing, along with faster gait, increased knee flexion, hip extension, and ankle dorsi-plantar flexion power. In adults, increased semimembranosus activation at initial contact might be related to a higher knee flexion moment by stabilizing the knee joint, controlling knee extension, and facilitating shock absorption [

26]. Furthermore, the greater soleus activation during push-off indicates stronger plantarflexor engagement, which is essential for efficient forward propulsion and faster gait observed in adults [

17]. In children, weaker push-off mechanisms may necessitate compensatory adaptations, such as increased cadence and hip flexion, whereas adults achieve higher walking speeds through more effective force generation at the ankle. The heightened rectus femoris activation in late swing further suggests a refined control strategy for decelerating the limb before initial contact, optimizing positioning for the subsequent stance phase. These gait adaptations could reflect the influence of growth on developing motor control, leading to a smoother and more coordinated gait cycle.

Gender-based differences in muscle activation patterns during gait have been well-documented in the literature [

16,

27,

28]. Females exhibit higher EMG activity in the tibialis anterior during terminal stance and the vastus lateralis during pre- and initial swing, alongside increased hip flexion, hip extension, and ankle dorsiflexion power. These findings align with previous studies, which suggest that females walk with greater hip flexion and reduced knee extension at touchdown compared to males, generating more mechanical power at the hip and ankle during the propulsion phase [

10]. Given their shorter height and leg length, females require a more flexed hip and plantarflexed ankle to generate sufficient power and compensate for their smaller physique while maintaining walking speed similar to males. Increased vastus lateralis activity in females, which was also observed in a different dynamic task like side-step maneuvers and stop jumps [

29,

30], may reflect the need for greater muscle engagement to sustain gait at the same speed as males, further supported by a higher hip flexion. Additionally, as Di Nardo et al. [

16] reported females tend to exhibit greater co-activation of ankle muscles, which was also seen in our study by an increased ankle joint power in this group, contributing to improved stride length and cadence despite their smaller size.

Increased activation of the tibialis anterior during terminal stance likely plays a key role in controlling foot positioning and facilitating ankle dorsiflexion, which is crucial for toe clearance and preparation for the swing phase. Specifically, Chiu and Wang [

31] found that, when analyzing the EMG signals of the biceps femoris, rectus femoris, gastrocnemius, and tibialis anterior, females exhibited significantly higher tibialis anterior activity during walking. This was also observed in our study for tibialis anterior. In contrast, males exhibited higher activation of the vastus lateralis and biceps femoris during terminal swing, along with a delayed foot-off. Given that males are typically taller and heavier, maintaining stability may require increased joint stiffness [

32]. Consequently, the greater co-activation of agonist and antagonist muscles likely contributes to stabilizing the knee and hip, preparing them for initial contact. The delayed foot-off, indicative of a prolonged stance phase, may further reflect the need for enhanced stability during gait.

The significant age-gender interaction effects observed in the biceps femoris and semimembranosus align with previous studies indicating that gender differences in muscle activation patterns become more pronounced with age [

14,

16]. Di Nardo et al. [

16] found that gender-related EMG differences in children appear predominantly during adolescence, with adult-like patterns emerging around the ages of 10–12 years. This aligns with our findings, where significant gender differences in the biceps femoris and semimembranosus were primarily observed in adults. In addition, while male children exhibited higher activity in both muscles during stance, this pattern reversed in adulthood, with females showing higher activity. These changes in muscle activation suggest that gait patterns evolve with age, with sex differences becoming more prominent in adulthood, likely as a result of neuromuscular maturation.

Our findings emphasize the necessity of considering both age and gender when establishing normative gait databases. While the impact of age on gait patterns in clinical settings is well-documented [

33,

34], our results highlight the equally important role of gender-related differences. Given the influence of sex-related variations in musculoskeletal structure and neuromuscular control, including both male and female participants across different age groups is crucial. Based on our power analysis, a minimum of 47 subjects is required to reliably detect age-gender interactions in EMG data, with at least 12 participants per subgroup (male children, female children, male adults, and female adults). According to our findings we strongly recommend that clinical norm bands incorporate both age and gender to enhance the accuracy of gait assessments and improve comparisons in both clinical and research settings.

A limitation of this study is the absence of juvenile participants, which restricts the ability to fully examine the effects of growth and maturation on EMG patterns across sexes. Future research should aim to include this age group to enable comprehensive comparisons across different developmental stages. Additionally, the influence of gait speed on EMG patterns was not analyzed. Hof et al. [

35] demonstrated that average EMG profiles consist of both speed-dependent and speed-independent components, suggesting that normalizing EMG patterns to gait speed could help mitigate the confounding effects of speed variations. However, in this study, participants walked at their self-selected speed without constraints, as the primary objective was to establish clinical EMG reference data for gait while focusing on age- and gender-related differences. Although gait speed was not a factor in our analysis, future studies should consider investigating its interaction effects alongside age and gender.

Author Contributions

MD: Writing original draft, Data analysis; FS: Review & editing, Methodology; CP: Review & editing; SIW: Review & editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration.

Funding

This research was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) (no: WO 1624/ 8-1). This funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics “Committee Medical Faculty, Heidelberg University Hospital” with the serial number S-243/2022.

Informed Consent Statement

The data analyzed in this retrospective study were part of a larger database established at the local University Clinics in the years 2000-2022 when retrieval was stopped. Only personnel that had regular legal access to the medical records retrieved patient data. They collected data in the time November and December 2022, and anonymized it in the same year December 28th. After this step, individual participants could not be identified anymore. The study was approved by the local Ethical Committee (no: S-243/2022) waiving the requirement for informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

‘The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.’There is no conflict of interest.

References

- Davoudi, M.; Salami, F.; Reisig, R.; Patikas, D.A.; Beckmann, N.A.; Gather, K.S.; Wolf, S. Are Electromyography data a fingerprint for patients with cerebral palsy (CP)? medRxiv 2024, 2024–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, M.; Salami, F.; Reisig, R.; Gather, K.S.; Wolf, S.I. Gluteus medius muscle activation patterns during gait with Cerebral Palsy (CP): A hierarchical clustering analysis. PLOS ONE 2025, 20, e0309582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, M.; Salami, F.; Reisig, R.; Patikas, D.A.; Wolf, S.I. Rectus femoris electromyography signal clustering: Data-driven management of crouch gait in patients with cerebral palsy. PLOS ONE 2024, 19, e0298945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreher, T.; Wolf, S.I.; Maier, M.; Hagmann, S.; Vegvari, D.; Gantz, S.; Heitzmann, D.; Wenz, W.; Braatz, F. Long-Term Results After Distal Rectus Femoris Transfer as a Part of Multilevel Surgery for the Correction of Stiff-Knee Gait in Spastic Diplegic Cerebral Palsy. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 2012, 94, e142–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agostini, V.; Ghislieri, M.; Rosati, S.; Balestra, G.; Knaflitz, M. Surface electromyography applied to gait analysis: How to improve its impact in clinics? Frontiers in neurology 2020, 11, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisig, R.; Alexander, N.; Armand, S.; Barton, G.J.; Böhm, H.; Boulay, C.; Brunner, R.; Castagna, A.; Davoudi, M.; Desailly, E.; et al. Status of surface electromyography assessment as part of clinical gait analysis in the management of patients with cerebral palsy – Outcomes of a Delphi process. Gait Posture 2024, 117, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M.H.; Rozumalski, A.; Trost, J.P. The effect of walking speed on the gait of typically developing children. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 1639–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bovi, G.; Rabuffetti, M.; Mazzoleni, P.; Ferrarin, M. A multiple-task gait analysis approach: Kinematic, kinetic and EMG reference data for healthy young and adult subjects. Gait Posture 2011, 33, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Park, J.; Kwon, O. Gender differences in three dimensional gait analysis data from 98 healthy Korean adults. Clin. Biomech. 2004, 19, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerrigan, D.C.; Todd, M.K.; Croce, U.D. Gender differences in joint biomechanics during walking Normative Study in Young Adults. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 1998, 77, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santuz, A.; Janshen, L.; Brüll, L.; Munoz-Martel, V.; Taborri, J.; Rossi, S.; Arampatzis, A. Sex-specific tuning of modular muscle activation patterns for locomotion in young and older adults. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0269417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, C.A.; Corona, F.; Pilloni, G.; Porta, M.; Fastame, M.C.; Hitchcott, P.K.; Penna, M.P.; Pau, M.; Côté, J.N. Sex-dependent and sex-independent muscle activation patterns in adult gait as a function of age. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 110, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloot, L.H.; Malheiros, S.; Truijen, S.; Saeys, W.; Mombaur, K.; Hallemans, A.; van Criekinge, T. Decline in gait propulsion in older adults over age decades. Gait Posture 2021, 90, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Hobara, H.; Heldoorn, T.A.; Kouchi, M.; Mochimaru, M. Age-independent and age-dependent sex differences in gait pattern determined by principal component analysis. Gait Posture 2016, 46, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Nardo, F.; Mengarelli, A.; Maranesi, E.; Burattini, L.; Fioretti, S. Gender differences in the myoelectric activity of lower limb muscles in young healthy subjects during walking. Biomed. Signal Process. Control. 2015, 19, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Nardo, F.; Laureati, G.; Strazza, A.; Mengarelli, A.; Burattini, L.; Agostini, V.; Nascimbeni, A.; Knaflitz, M.; Fioretti, S. Is child walking conditioned by gender? Surface EMG patterns in female and male children. Gait Posture 2017, 53, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, A.; Silder, A.; Heiderscheit, B.; Mahoney, J.; Thelen, D.G. Differences in lower-extremity muscular activation during walking between healthy older and young adults. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol. 2009, 19, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataky, T.C. Generalized n-dimensional biomechanical field analysis using statistical parametric mapping. J. Biomech. 2010, 43, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadaba, M.P.; Ramakrishnan, H.K.; Wootten, M.E. Measurement of lower extremity kinematics during level walking. J. Orthop. Res. 1990, 8, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermens, H.J.; Freriks, B.; Merletti, R.; Stegeman, D.; Blok, J.; Rau, G.; Disselhorst-Klug, C.; Hägg, G. European recommendations for surface electromyography. Roessingh research and development 1999, 8, 13–54. [Google Scholar]

- Patikas, D.; Wolf, S.I.; Schuster, W.; Armbrust, P.; Dreher, T.; Döderlein, L. Electromyographic patterns in children with cerebral palsy: Do they change after surgery? Gait & posture 2007, 26, 362–371. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, S.; Loose, T.; Schablowski, M.; Döderlein, L.; Rupp, R.; Gerner, H.J.; Bretthauer, G.; Mikut, R. Automated feature assessment in instrumented gait analysis. Gait Posture 2006, 23, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Liao, L.; Luo, X.; Ye, X.; Yao, Y.; Chen, P.; Shi, L.; Huang, H.; Wu, Y. Analysis and Classification of Stride Patterns Associated with Children Development Using Gait Signal Dynamics Parameters and Ensemble Learning Algorithms. BioMed Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nene, A.; Mayagoitia, R.; Veltink, P. Assessment of rectus femoris function during initial swing phase. Gait Posture 1999, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augsburger, S.; White, H.; Iwinski, H. Midstance hamstring length is a better indicator for hamstring lengthening procedures than initial contact length. Gait Posture 2020, 80, 26–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrath, J.M.; Saxby, D.J.; Killen, B.A.; Pizzolato, C.; Vertullo, C.J.; Barrett, R.S.; Lloyd, D.G. Muscle contributions to medial tibiofemoral compartment contact loading following ACL reconstruction using semitendinosus and gracilis tendon grafts. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0176016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMont, R.G.; Lephart, S.M. Effect of sex on preactivation of the gastrocnemius and hamstring muscles: Table 1. Br. J. Sports Med. 2004, 38, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.-U.; Tolea, M.I.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Ferrucci, L. Sex-specific differences in gait patterns of healthy older adults: Results from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J. Biomech. 2011, 44, 1974–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, J.D.; Creighton, R.A.; Giuliani, C.; Yu, B.; Garrett, W.E. Kinematics and electromyography of landing preparation in vertical stop-jump: risks for noncontact anterior cruciate ligament injury. The American journal of sports medicine 2007, 35, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigward, S.M.; Powers, C.M. The influence of gender on knee kinematics, kinetics and muscle activation patterns during side-step cutting. Clin. Biomech. 2006, 21, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.-C.; Wang, M.-J. The effect of gait speed and gender on perceived exertion, muscle activity, joint motion of lower extremity, ground reaction force and heart rate during normal walking. Gait Posture 2007, 25, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cammarata, M.L.; Dhaher, Y.Y. The differential effects of gender, anthropometry, and prior hormonal state on frontal plane knee joint stiffness. Clin. Biomech. 2008, 23, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, S.-U.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Ferrucci, L. Age-associated differences in the gait pattern changes of older adults during fast-speed and fatigue conditions: Results from the Baltimore longitudinal study of ageing. Age Ageing 2010, 39, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Nakayama, E.; Hanaoka, M. Effects of aging on gait patterns in the healthy elderly. Anthr. Sci. 2007, 115, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hof, A.L.; Elzinga, H.; Grimmius, W.; Halbertsma, J.P.K. Speed dependence of averaged EMG profiles in walking. Gait Posture 2002, 16, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).