Submitted:

19 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

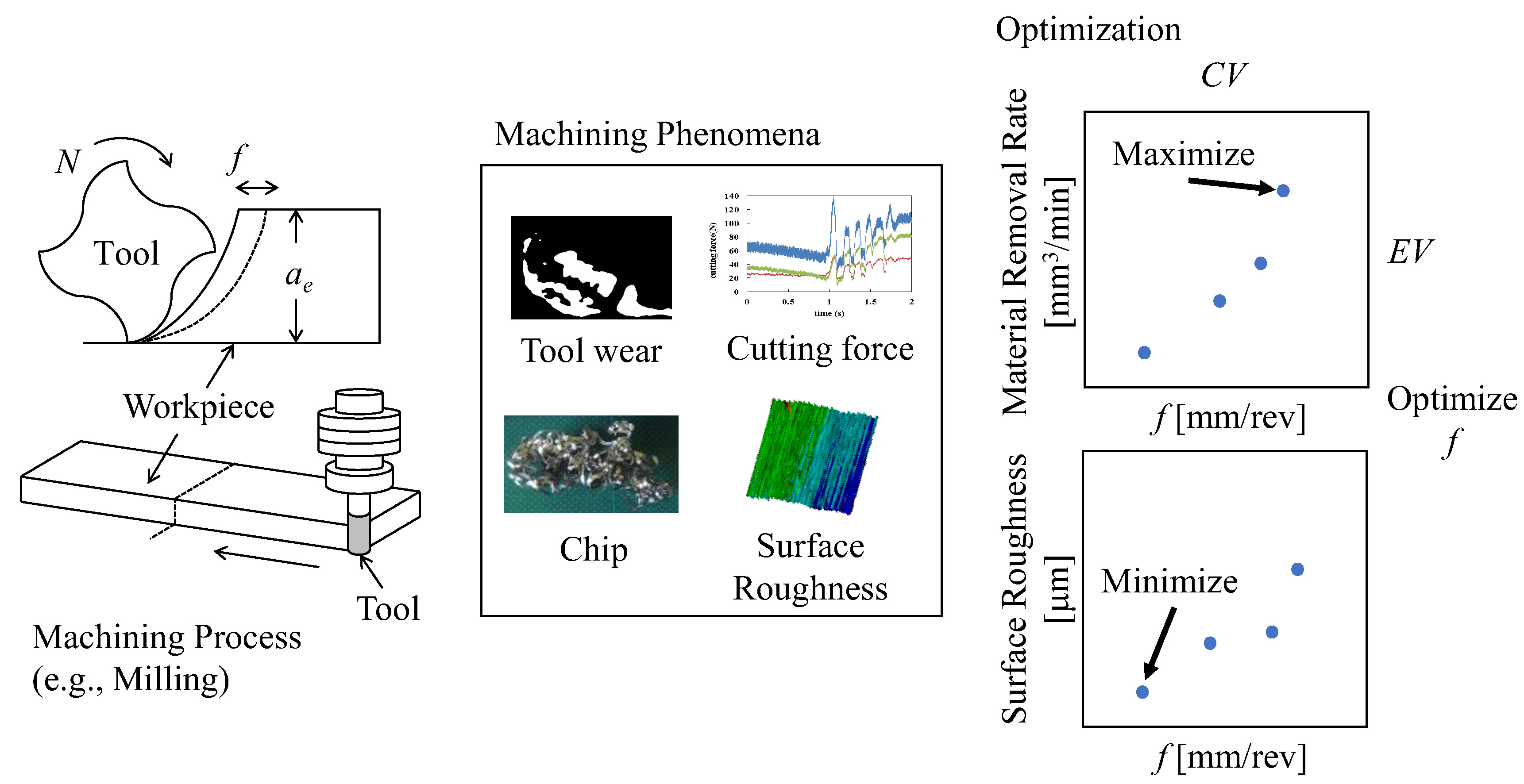

1. Introduction

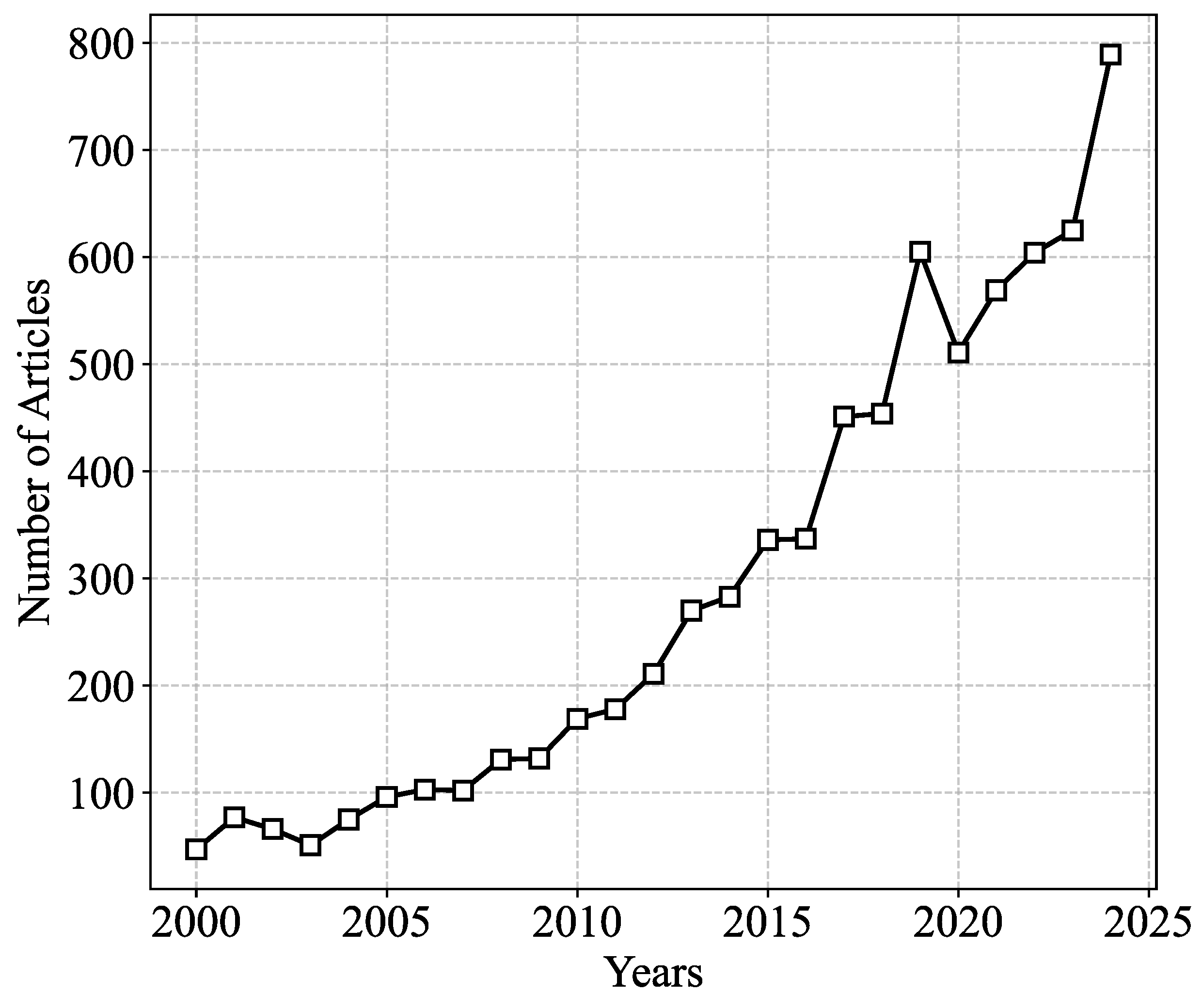

2. Literature Review

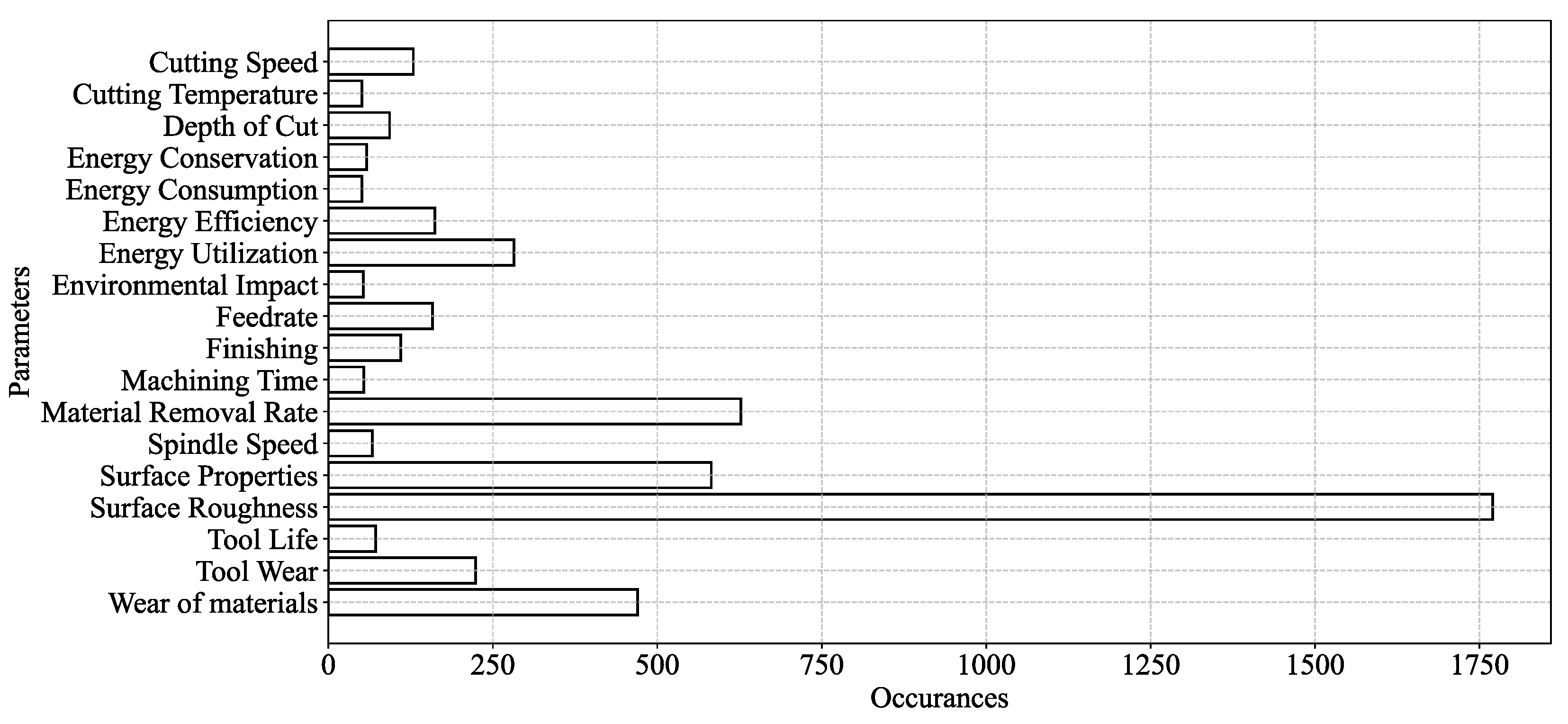

2.1. Overview

2.2. Selected Studies

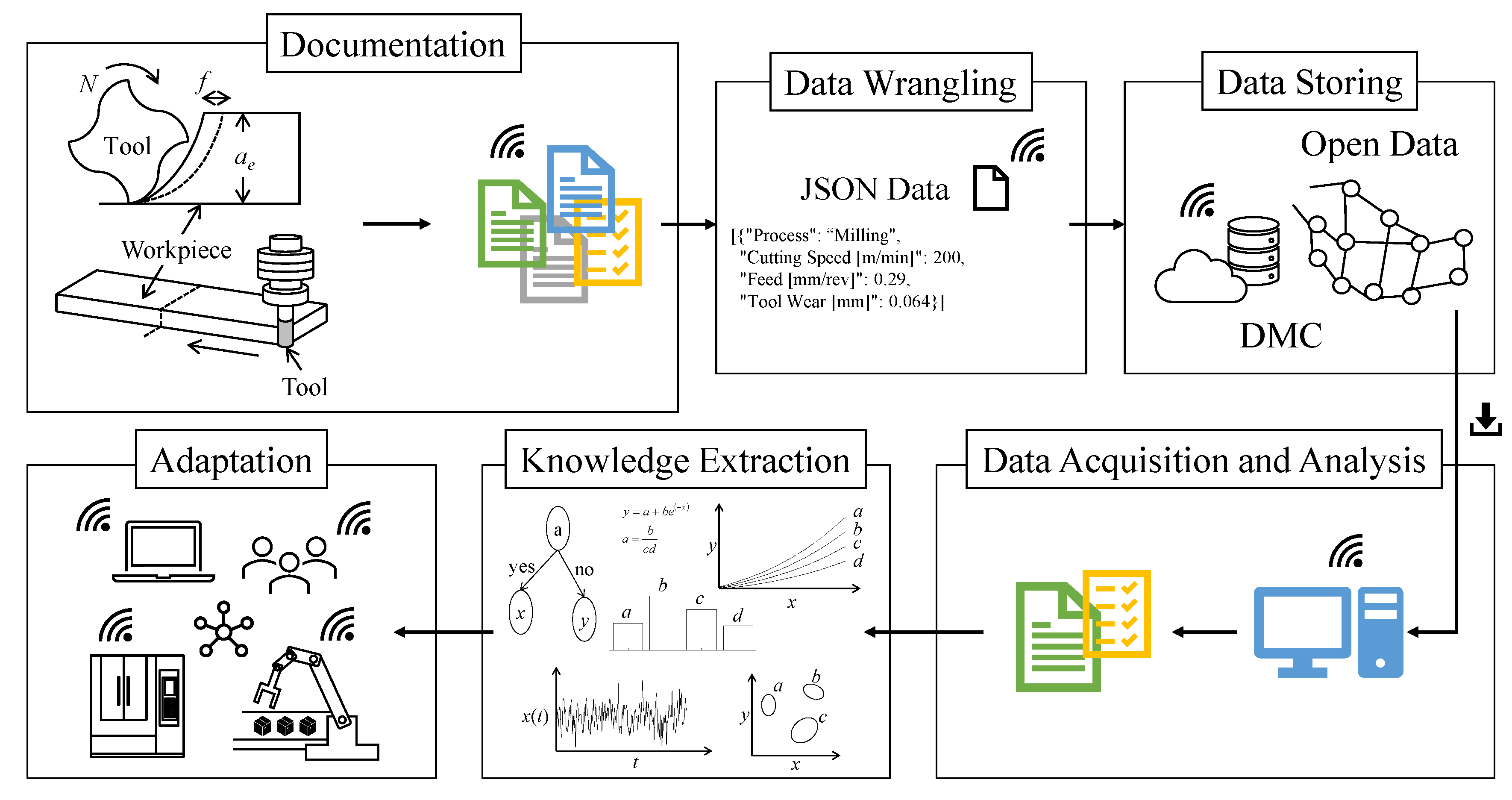

3. Methods

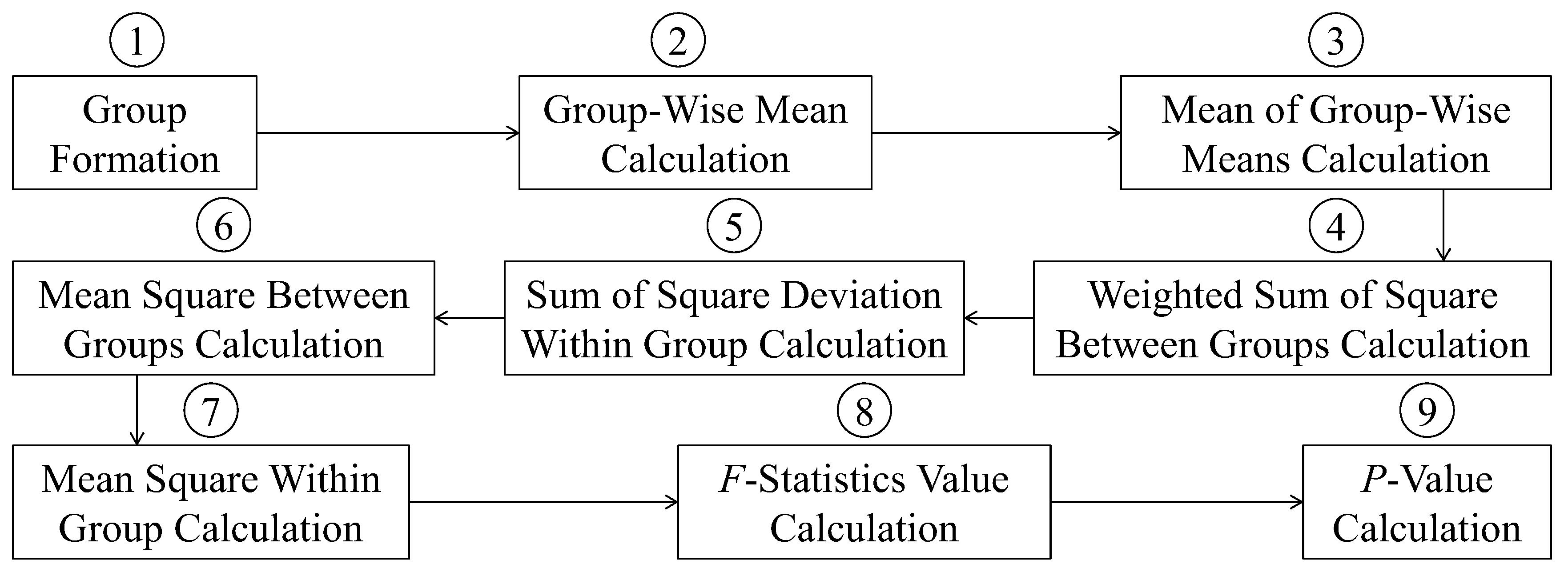

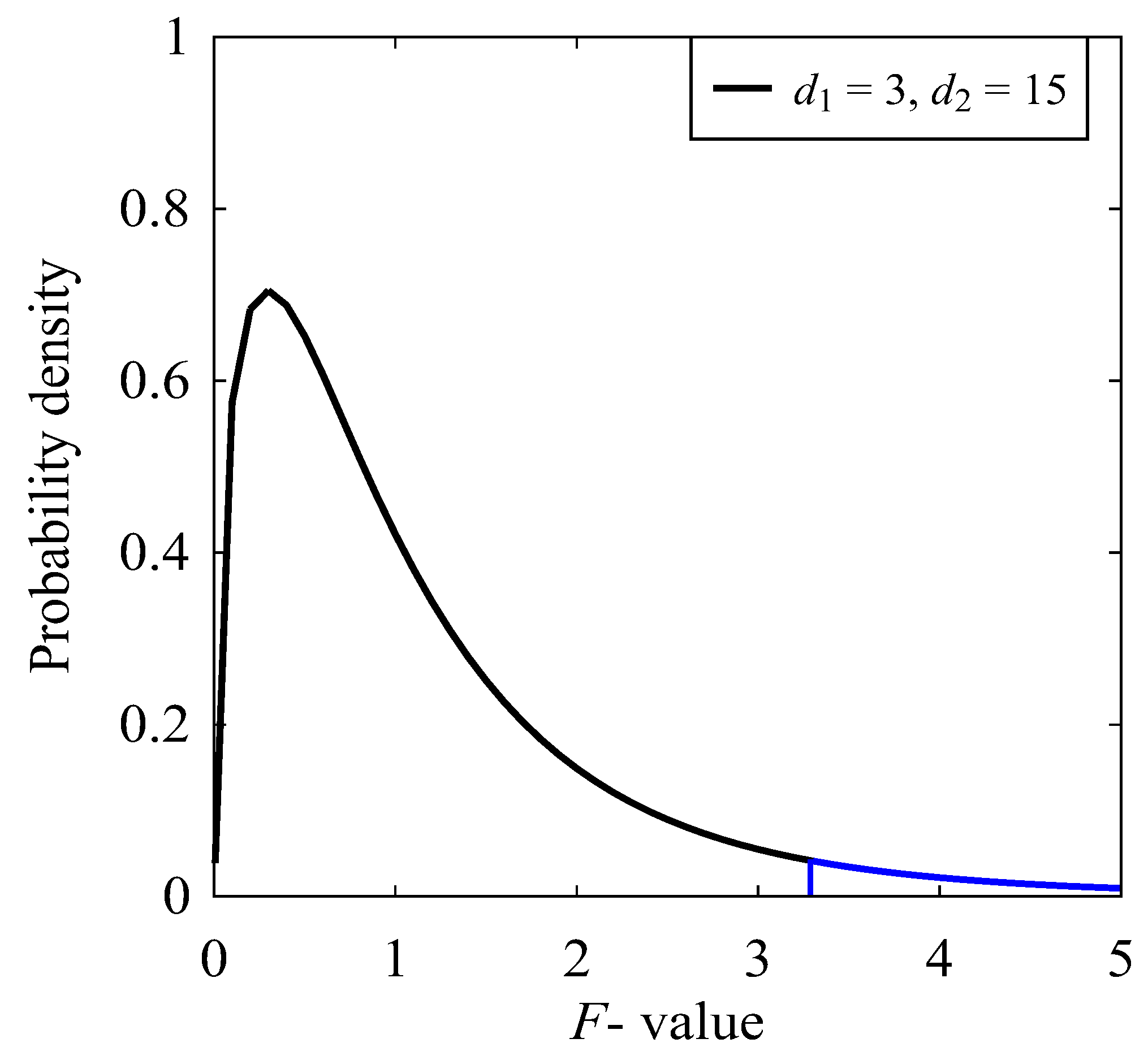

3.1. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA)

3.2. Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)

3.2.1. Smaller-the-Better (STB)

3.2.2. Larger-the-Better (LTB)

3.2.3. Nominal-the-Better (NTB)

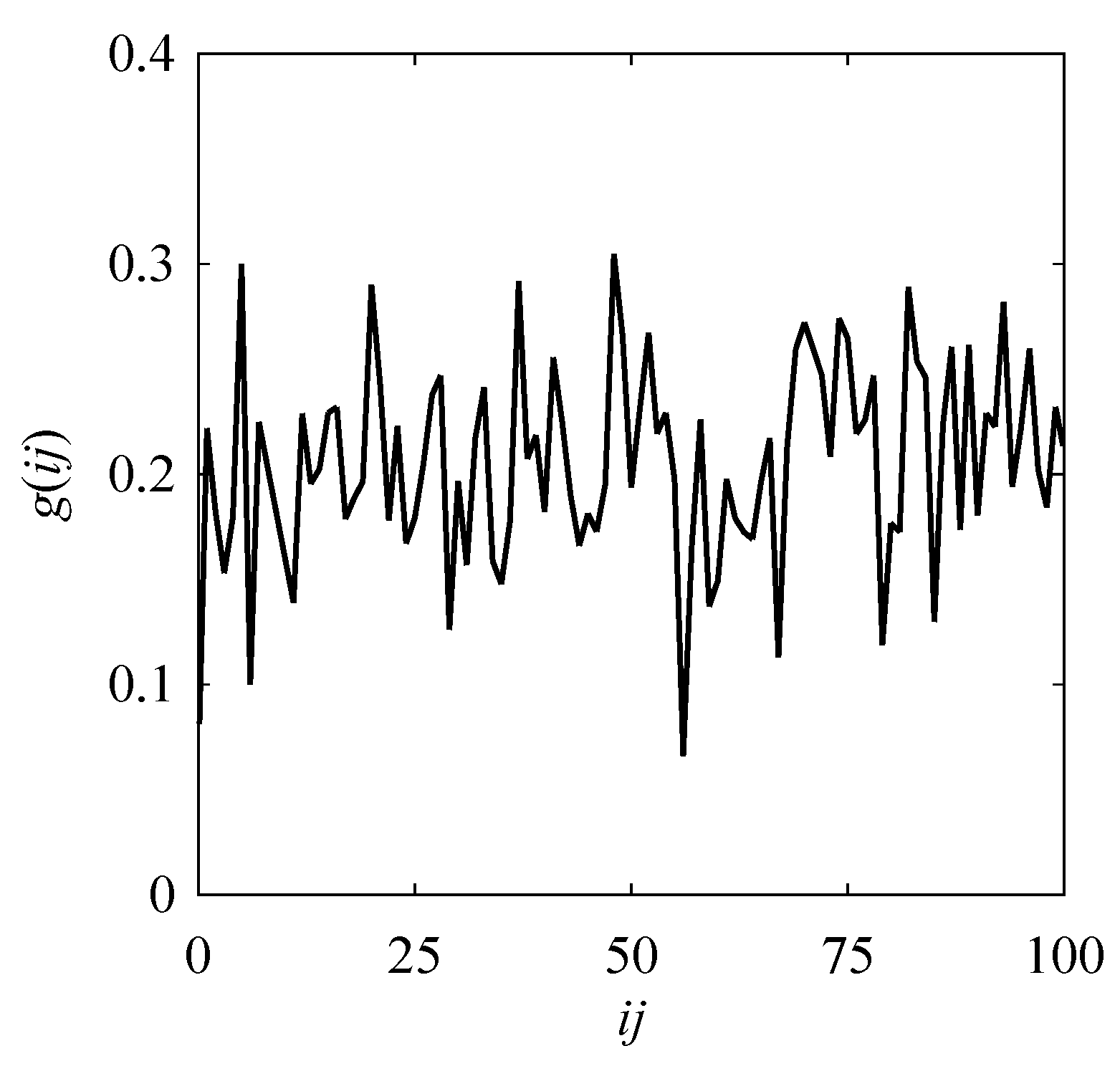

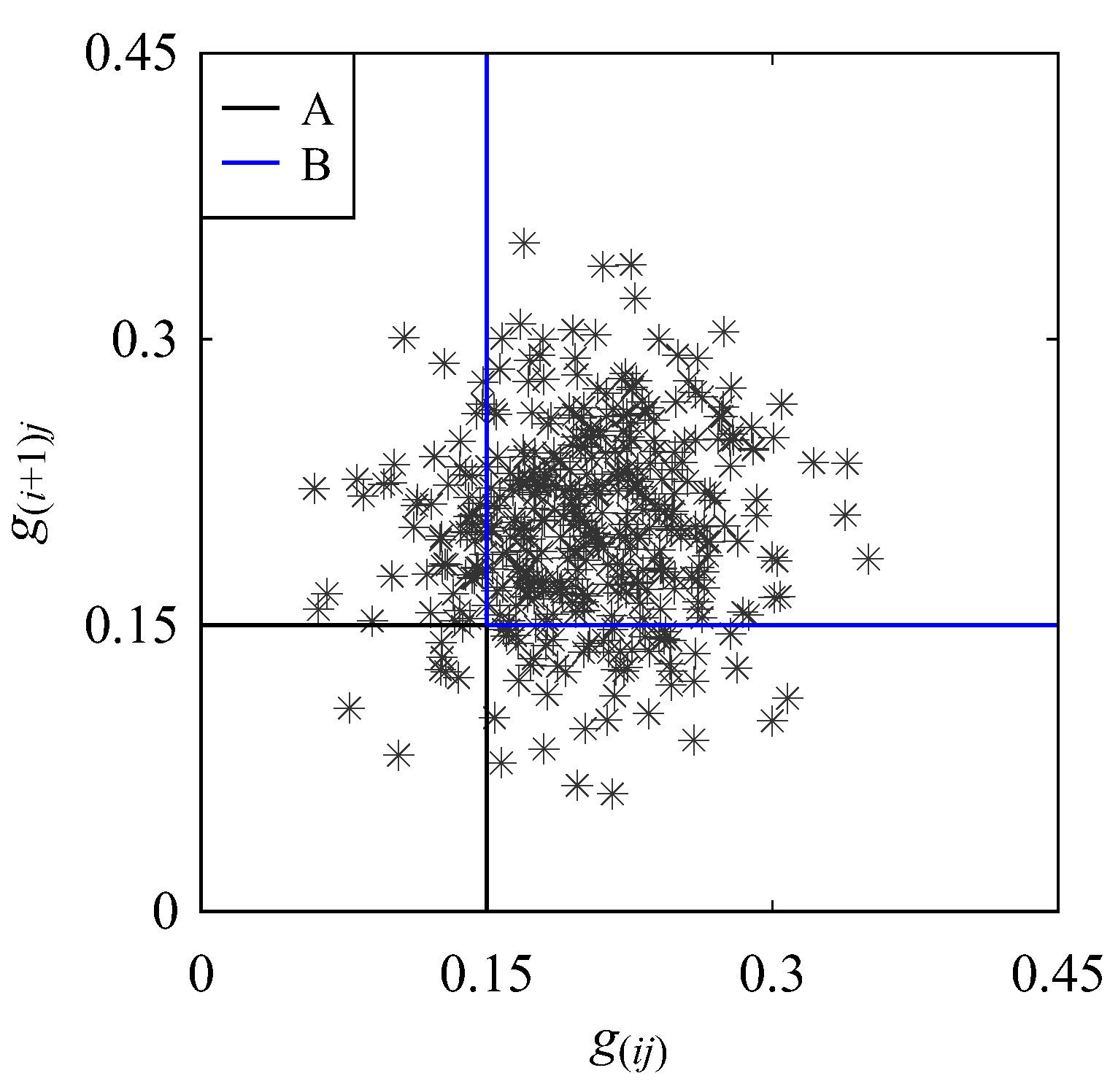

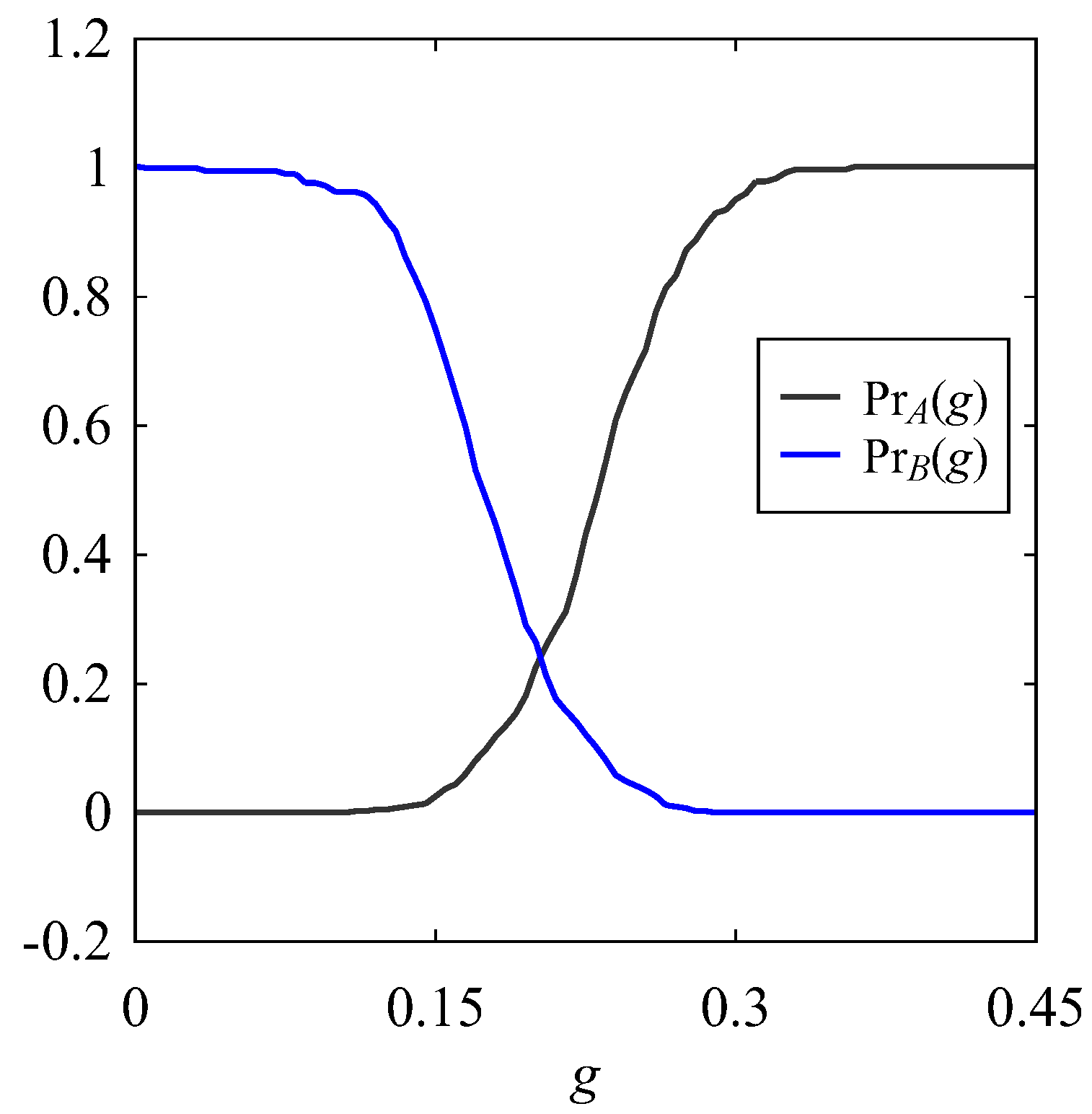

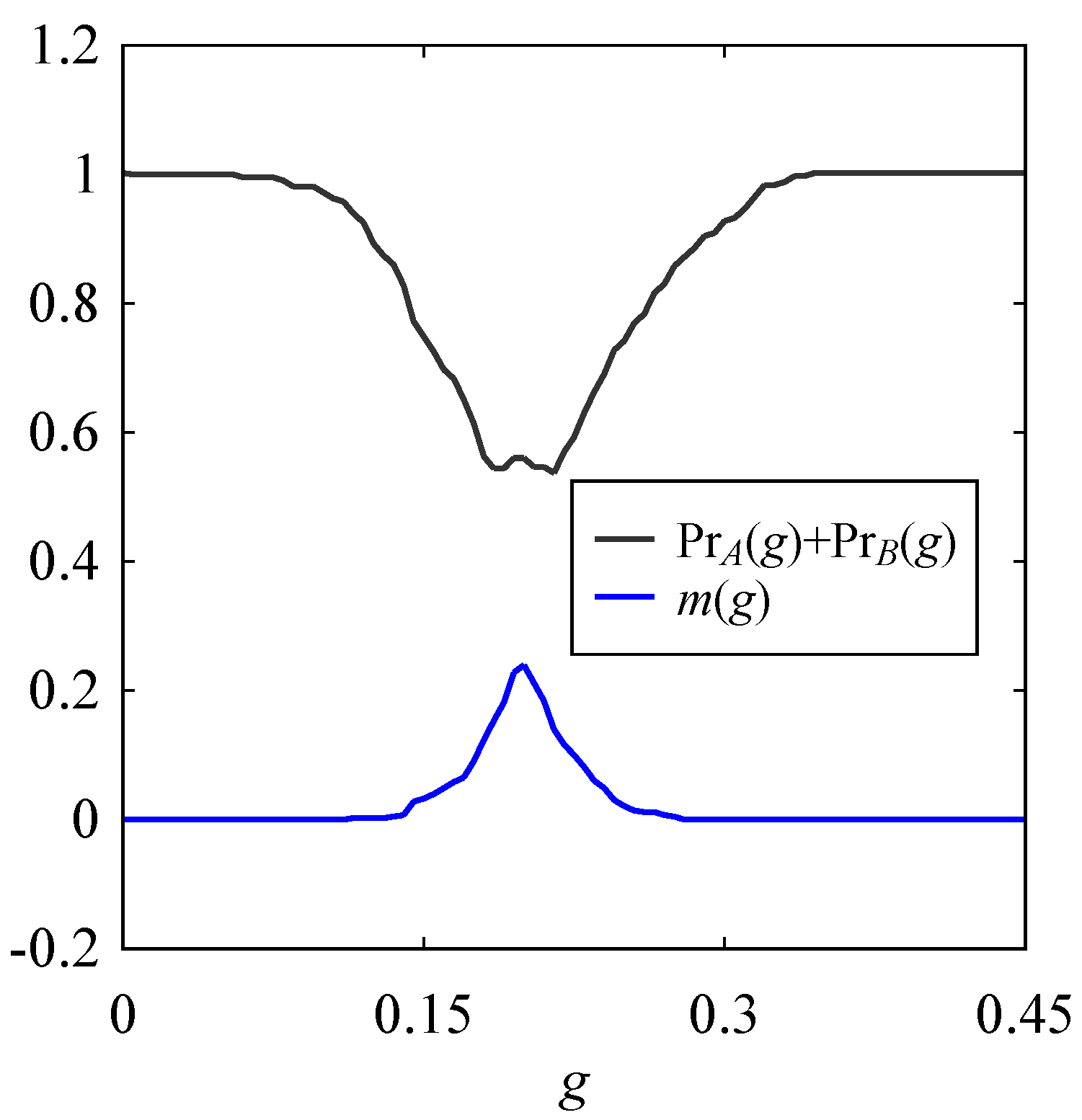

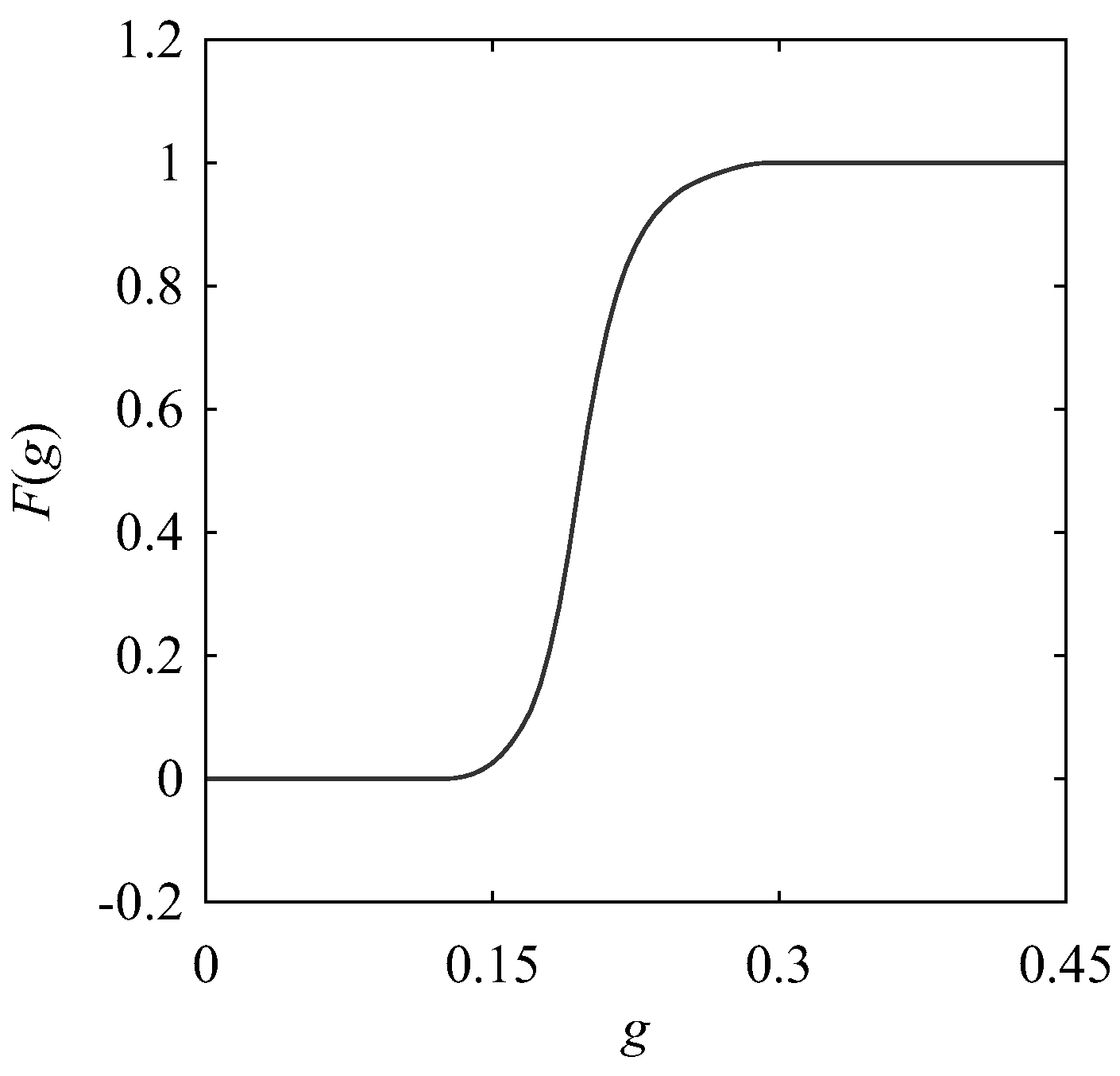

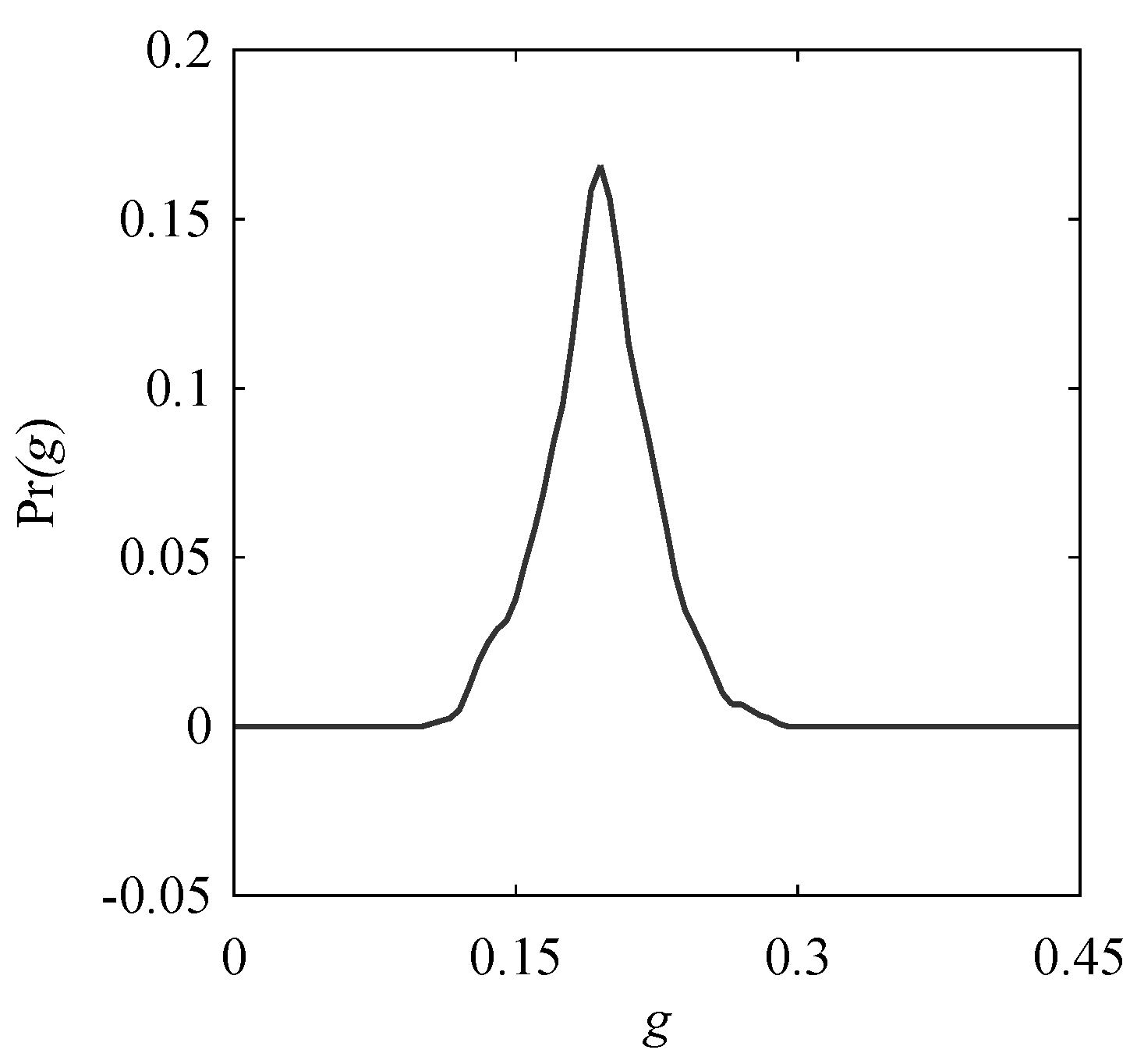

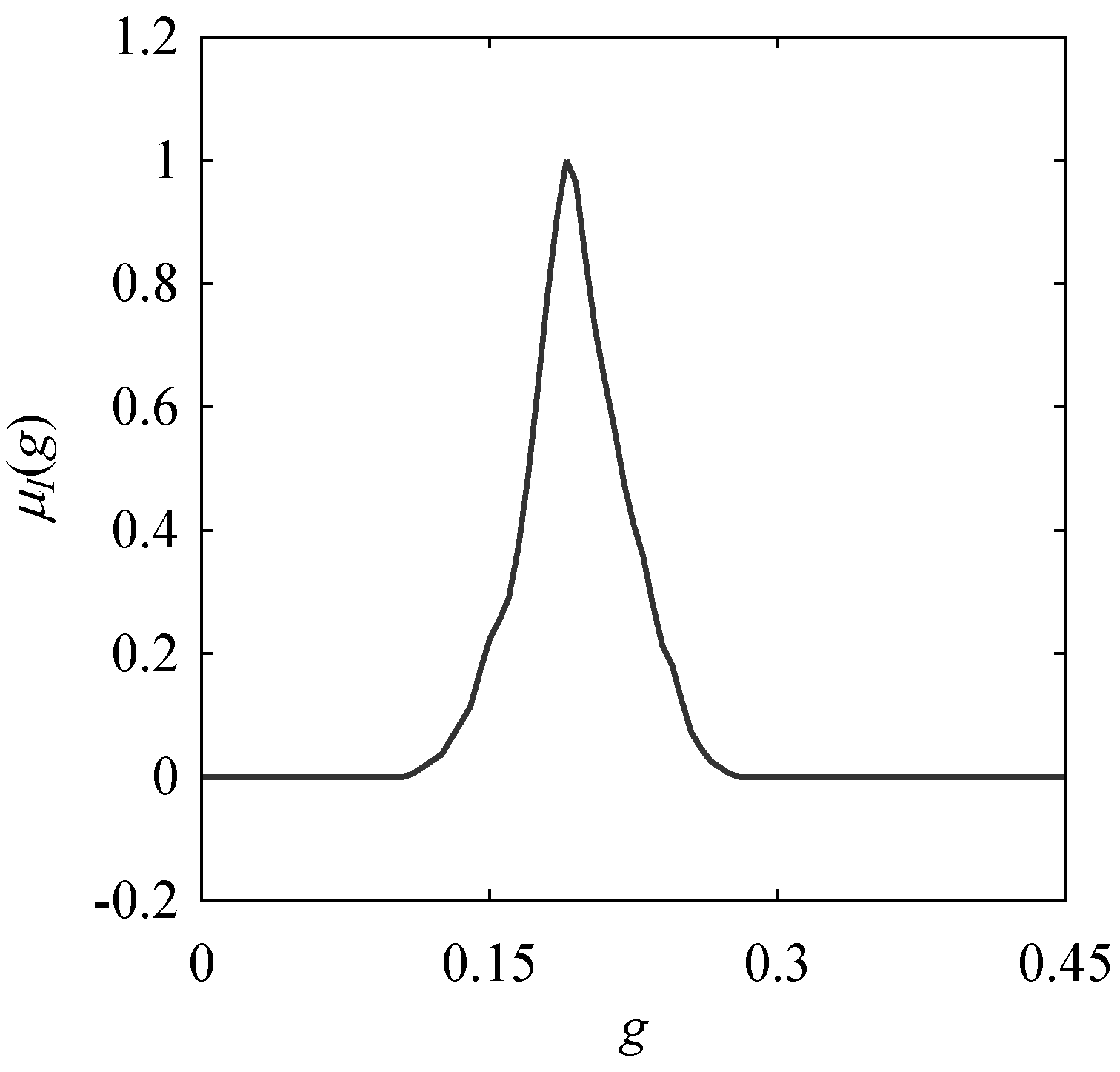

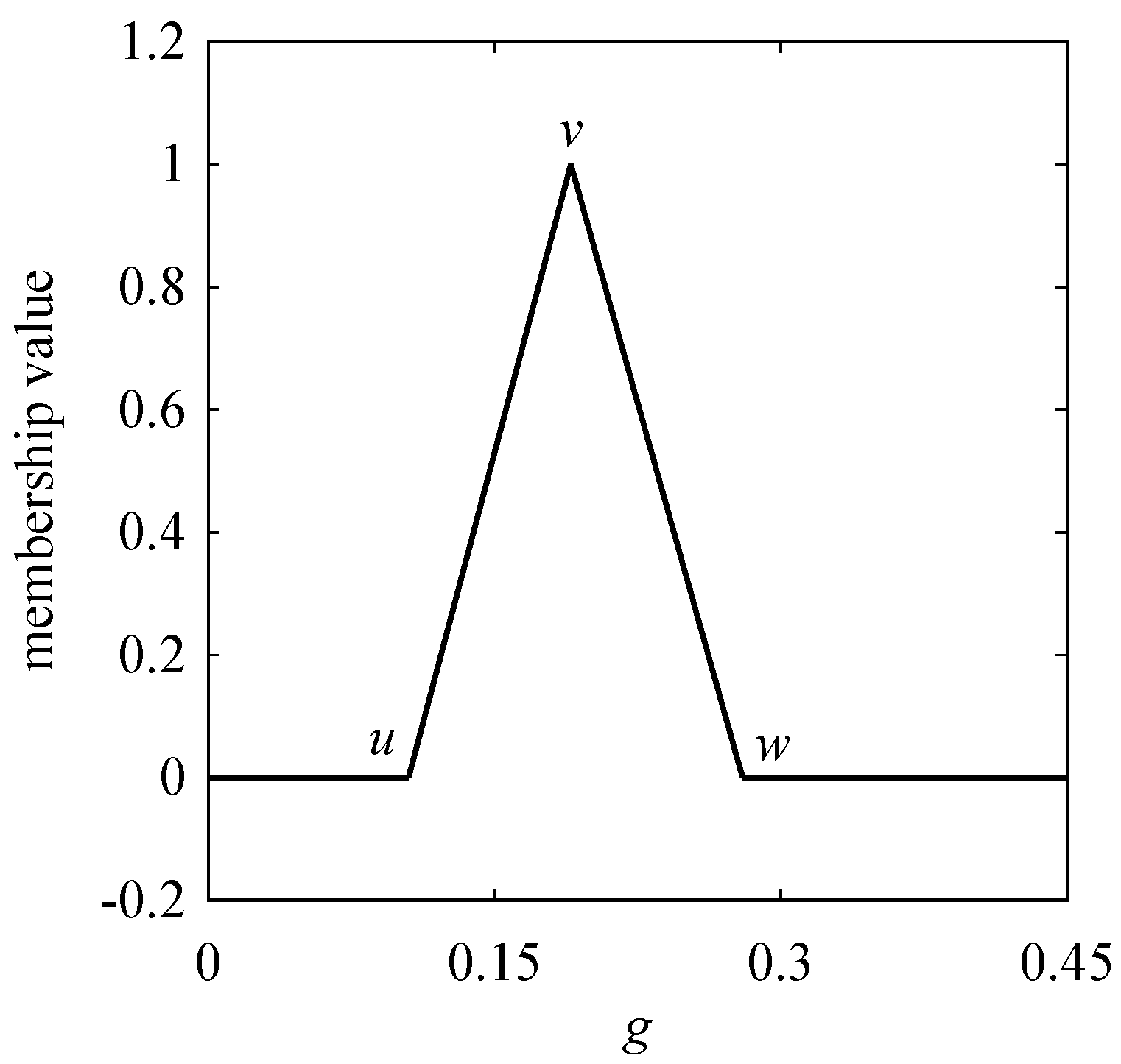

3.3. Possibility Distribution (PD)

4. Results

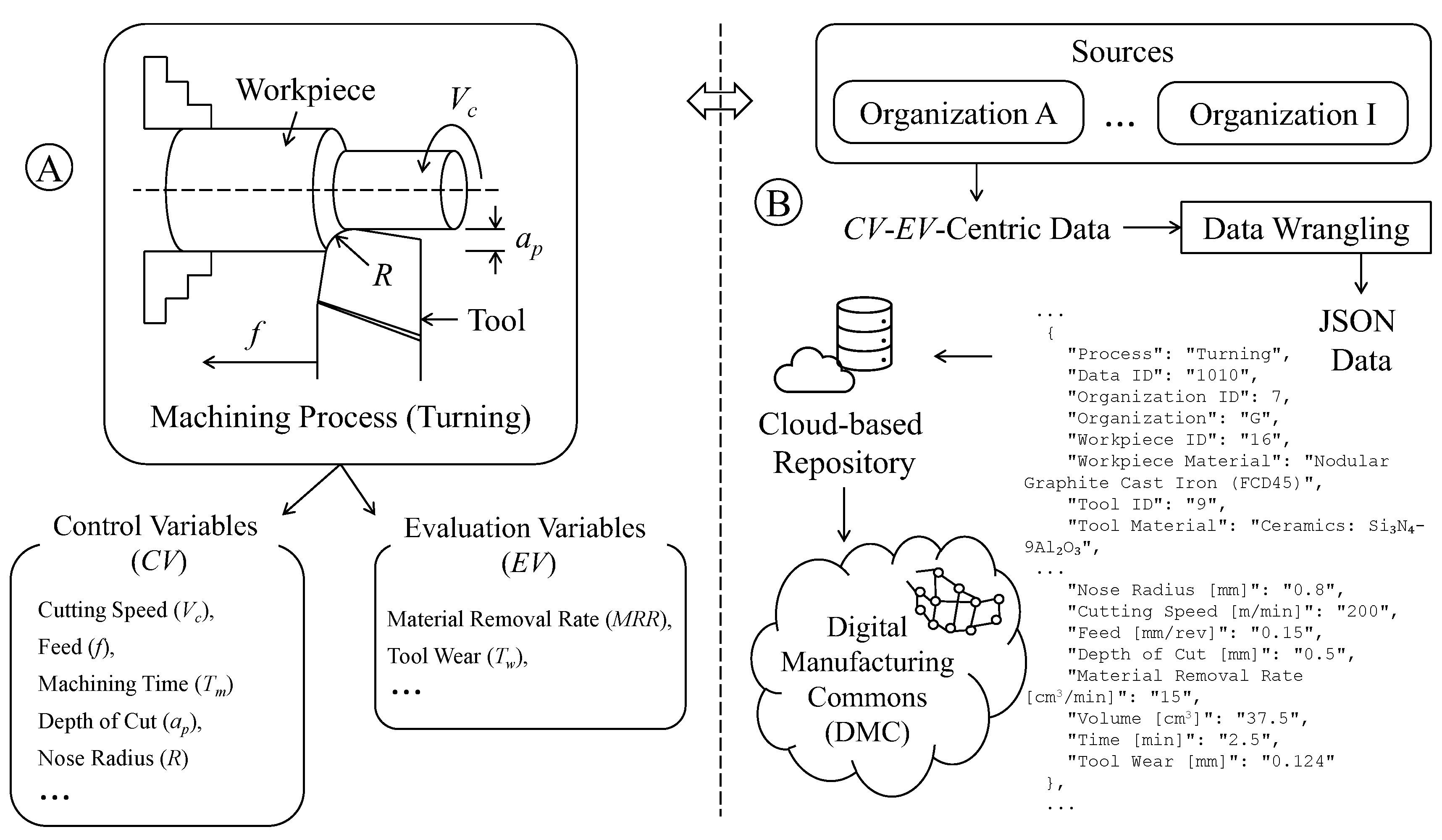

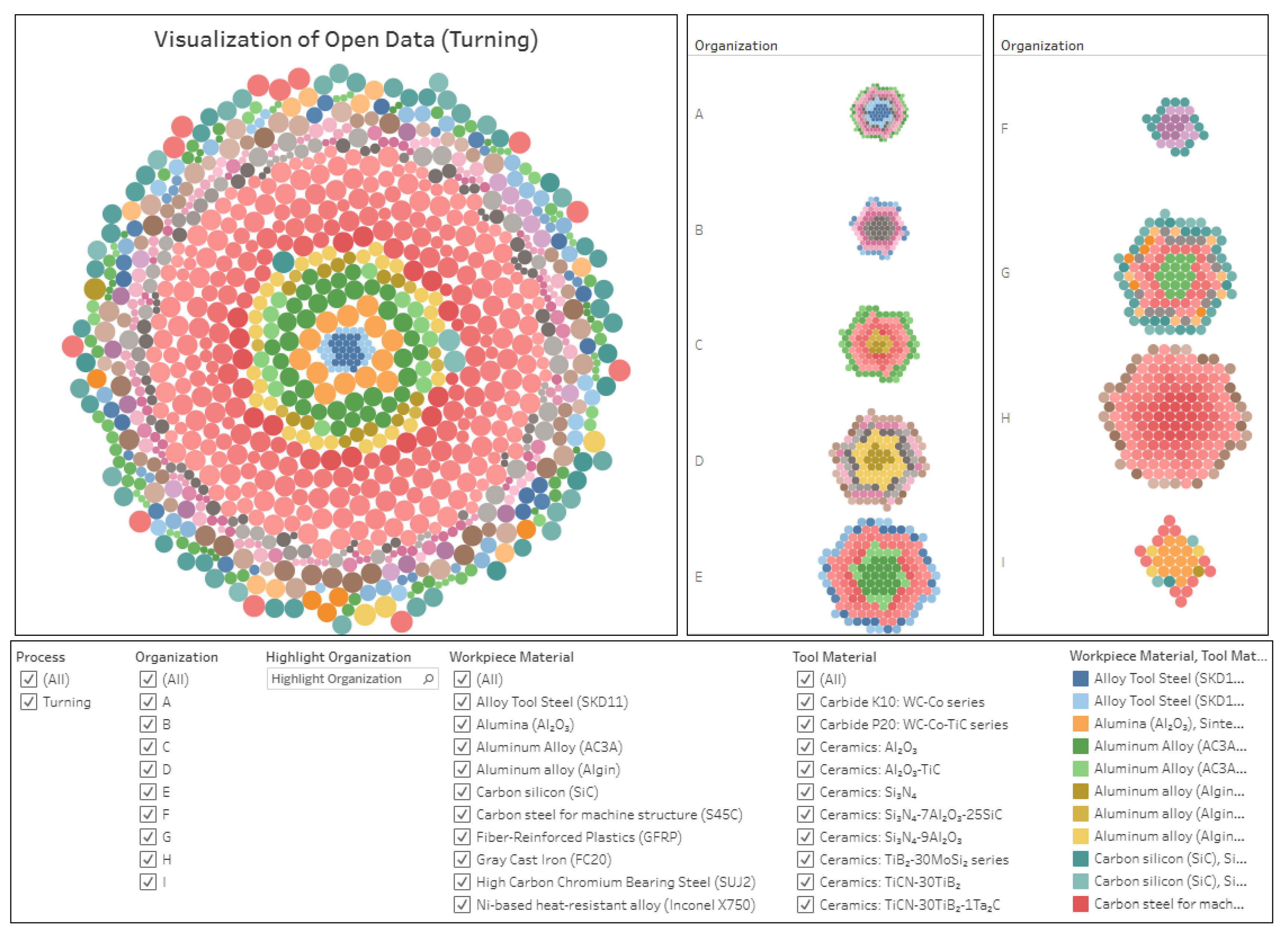

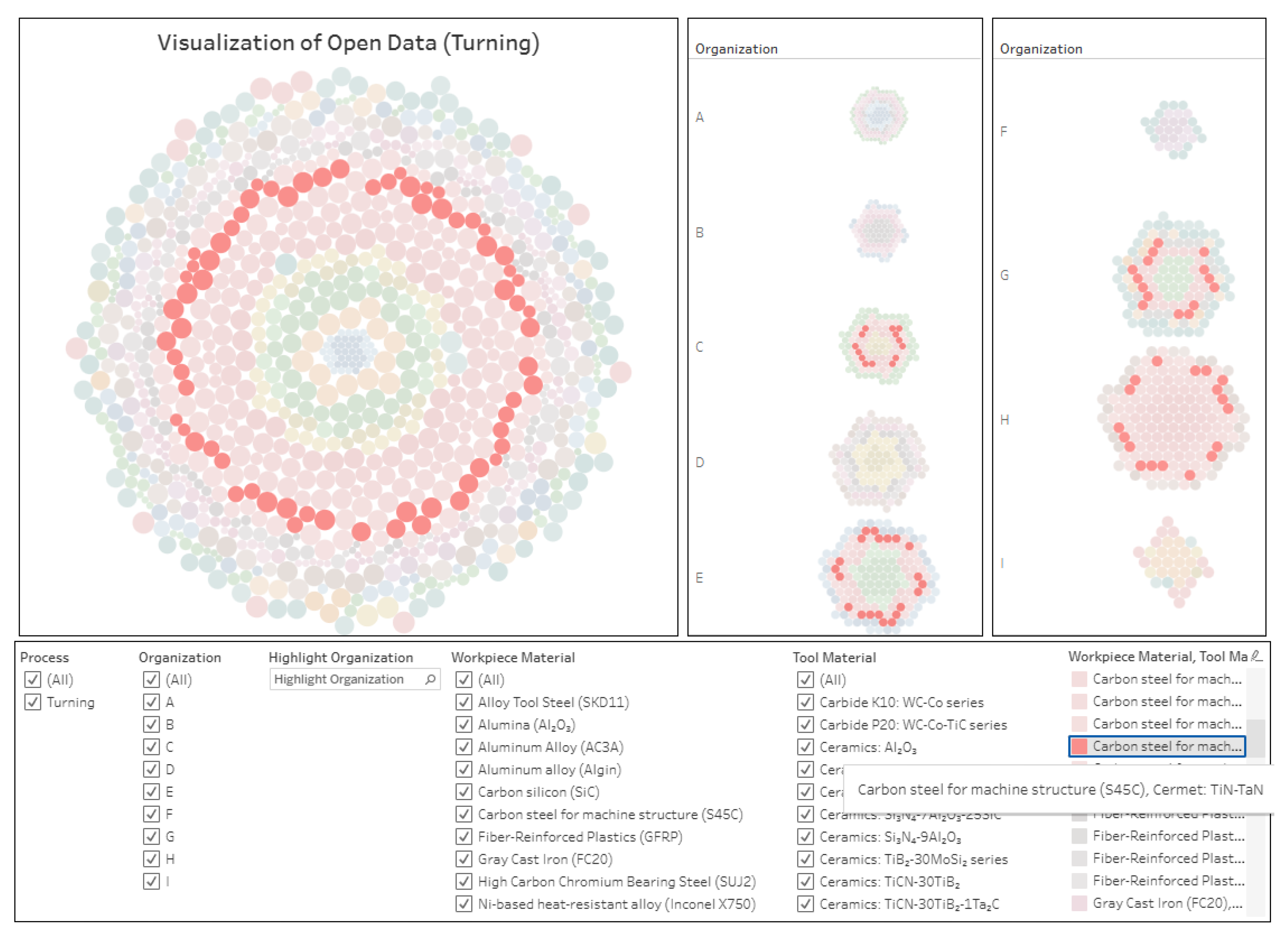

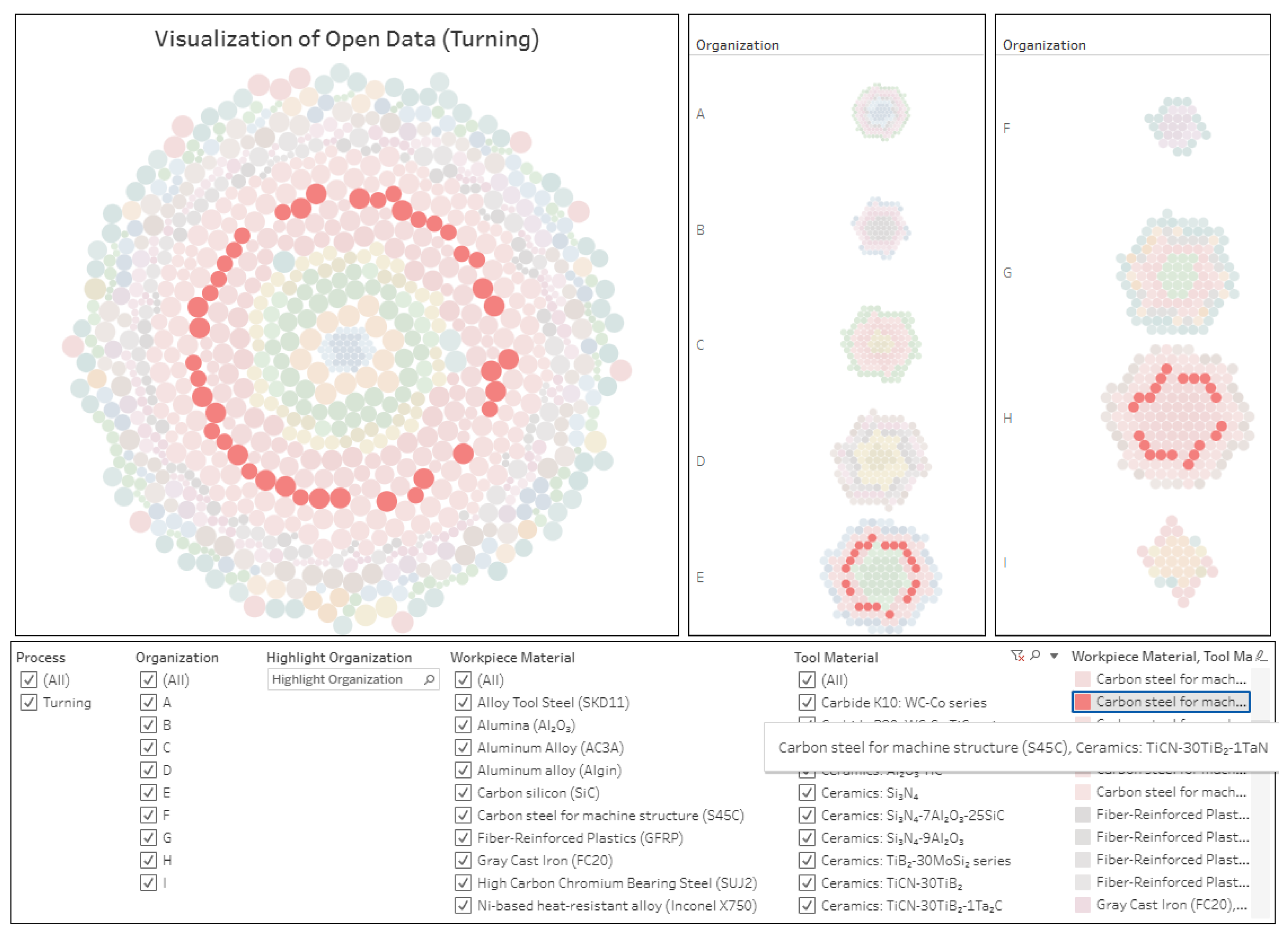

4.1. Open Data and Its Preparation

4.2. Analyses

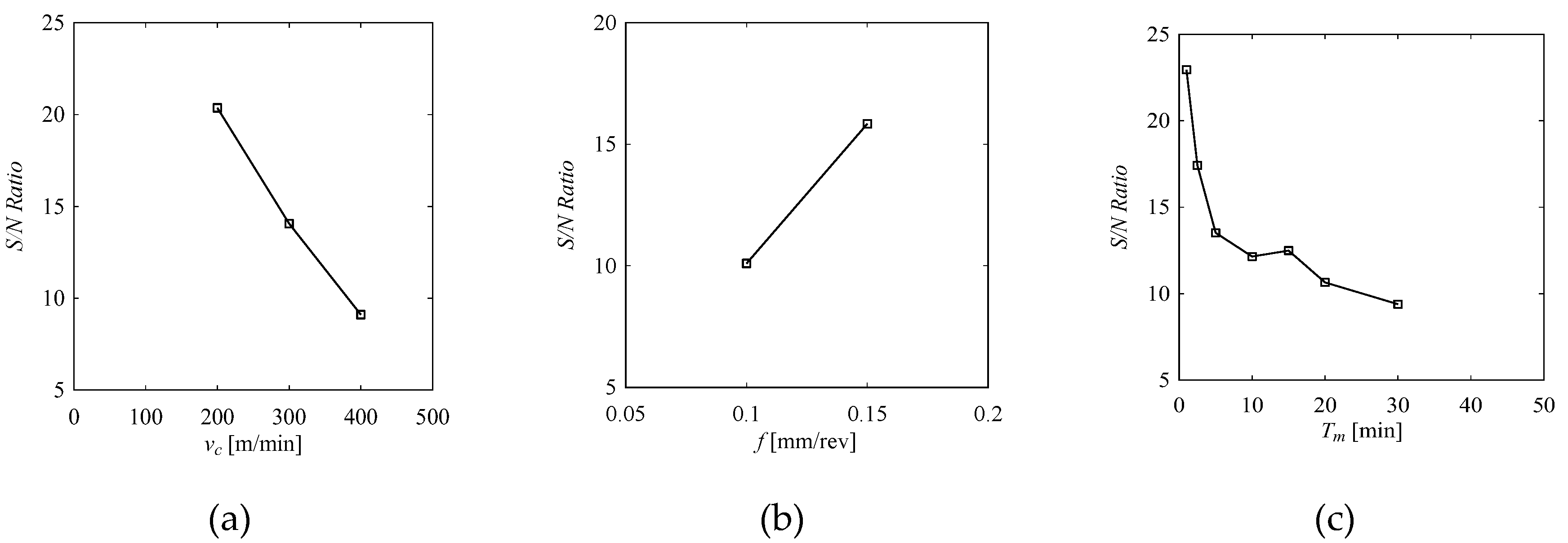

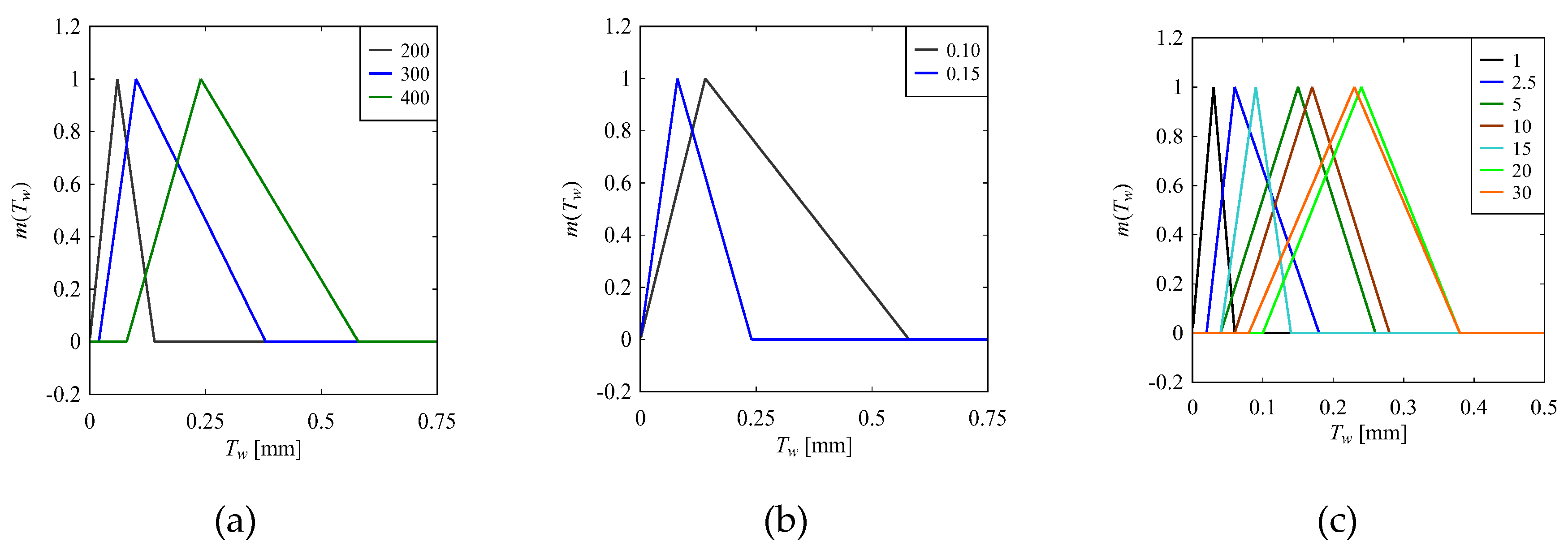

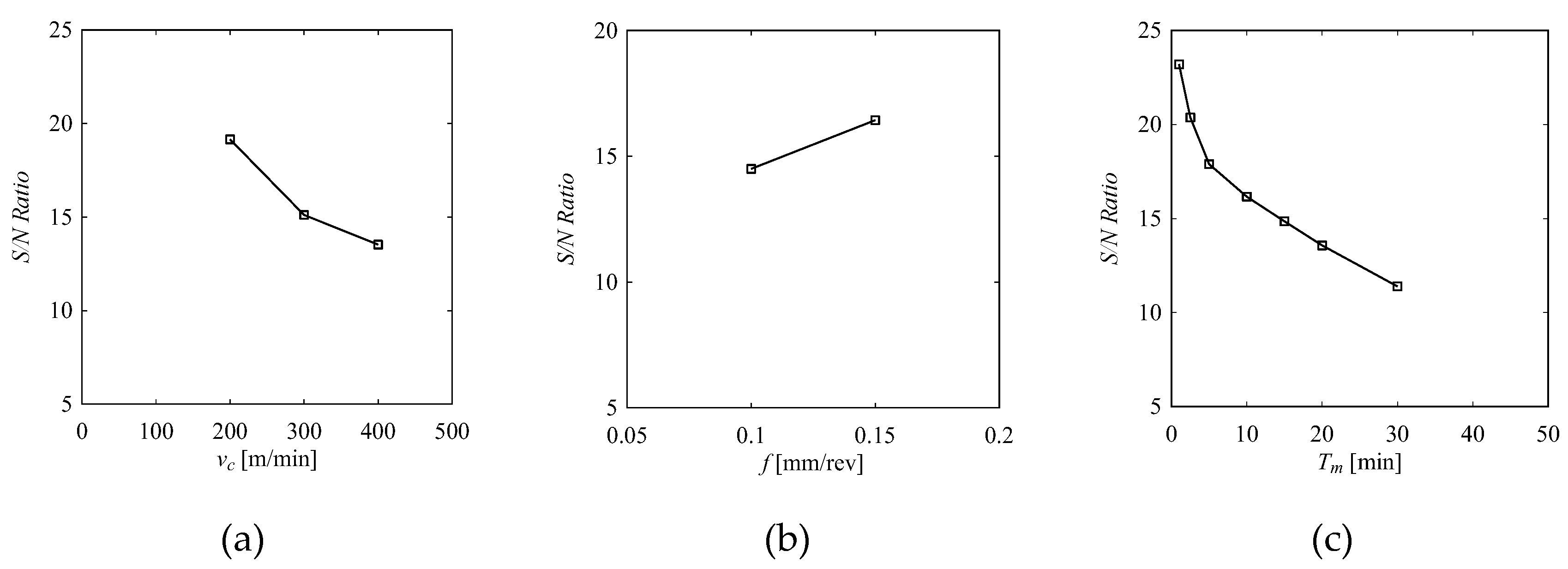

4.2.1. WM1-TM1

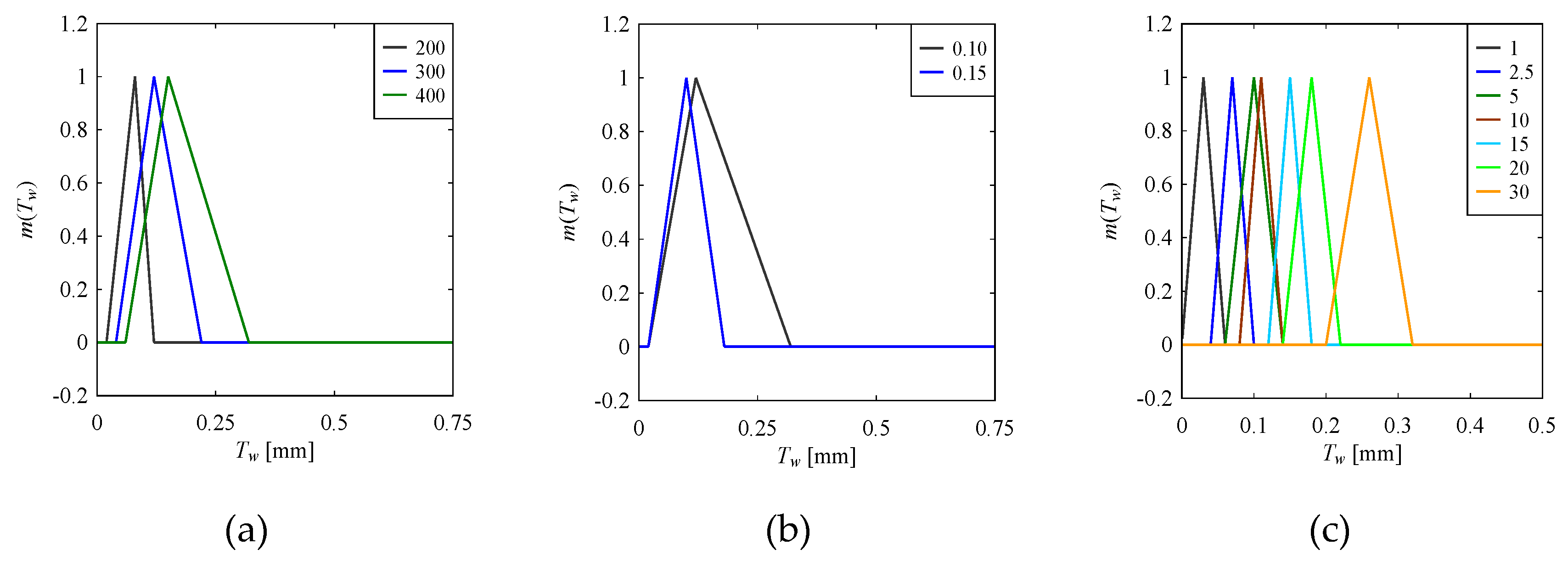

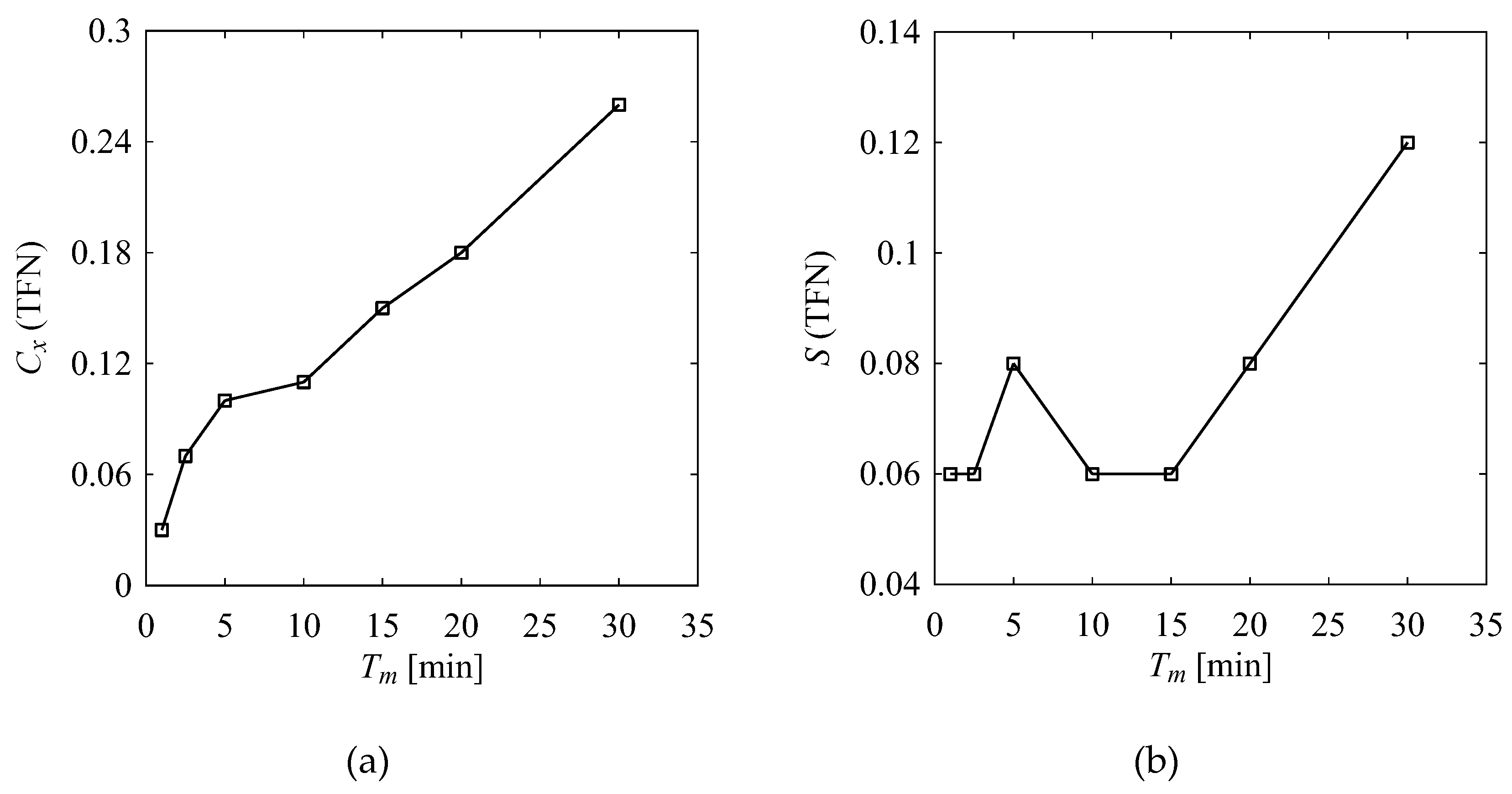

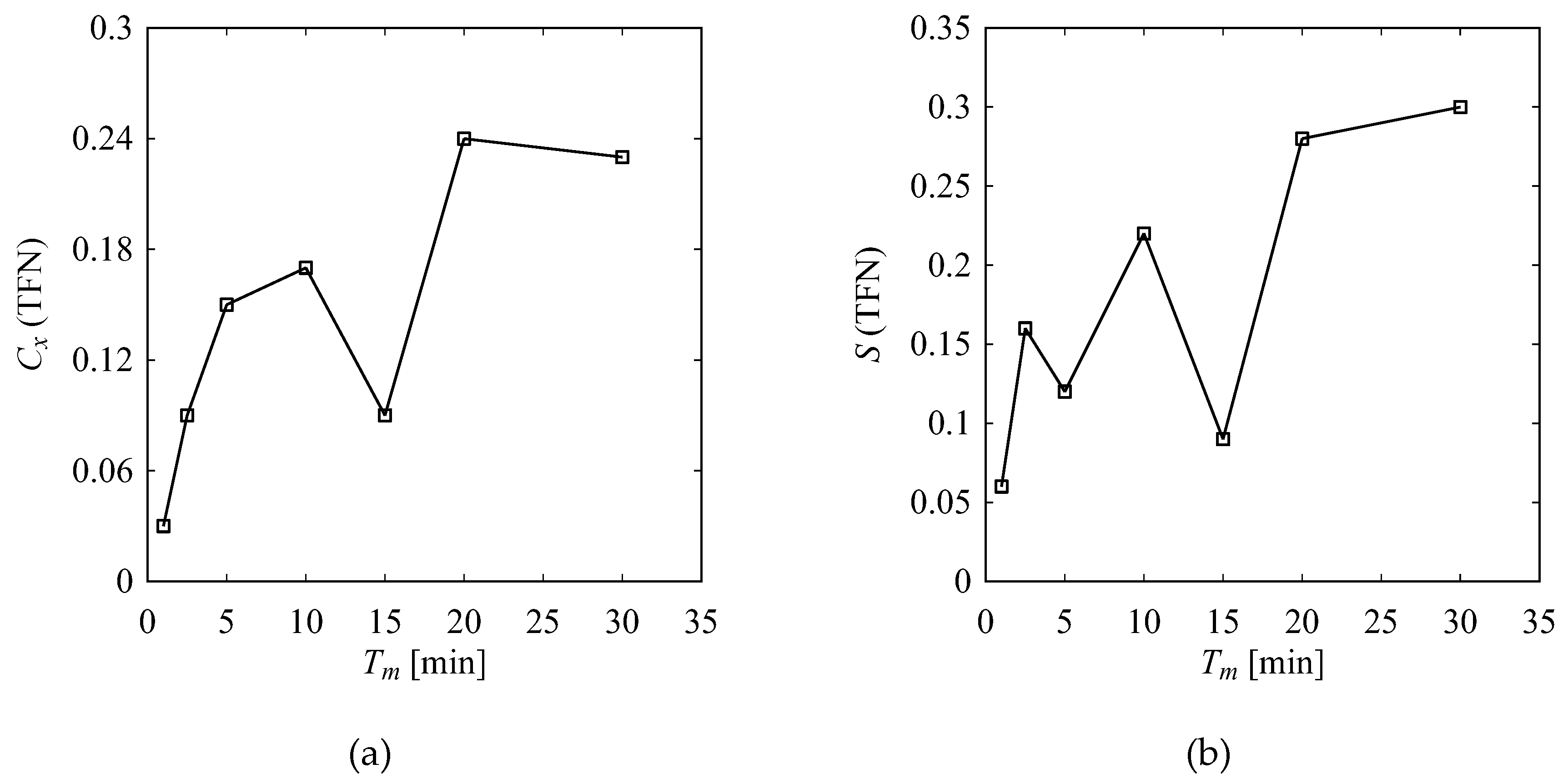

4.2.2. WM1-TM2

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Appendix

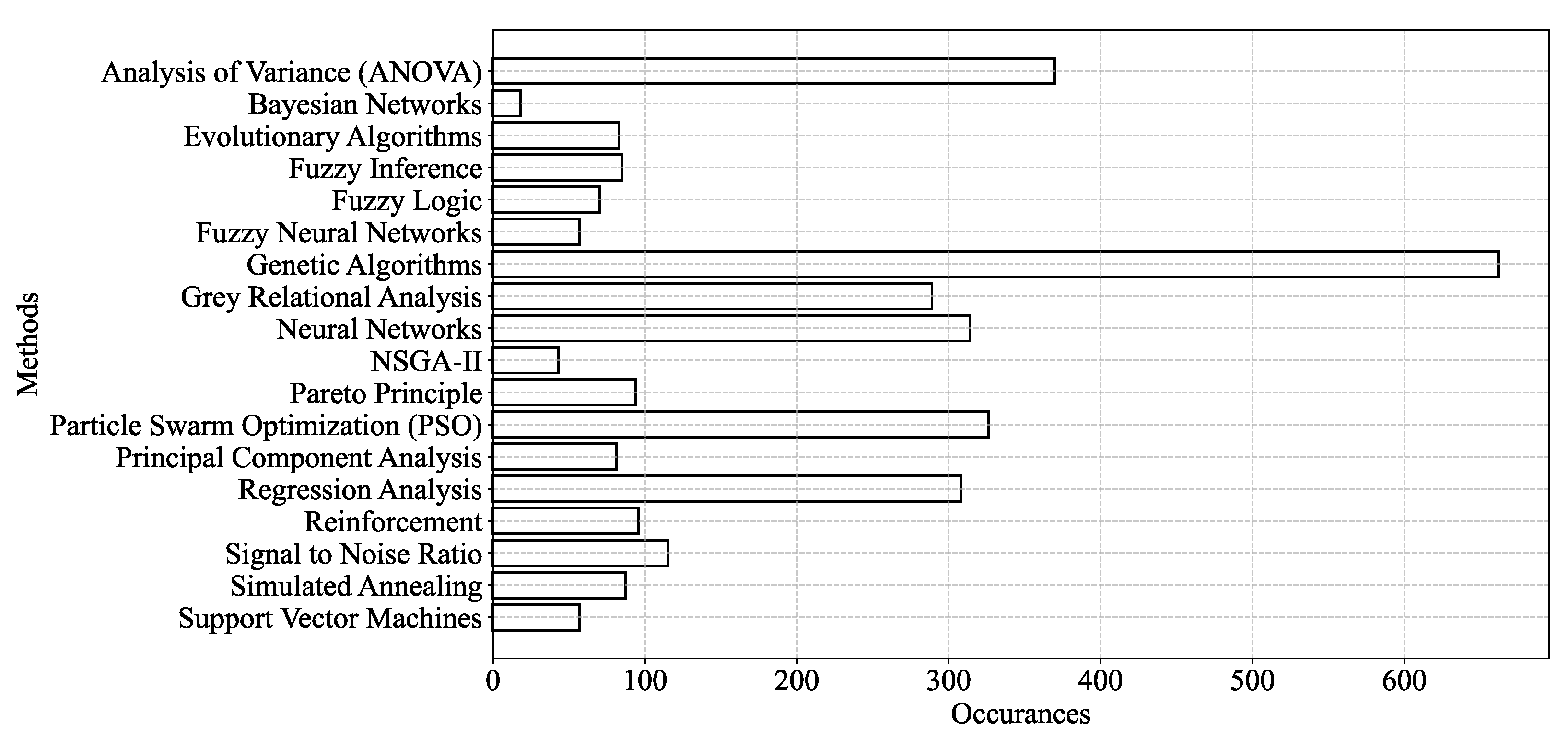

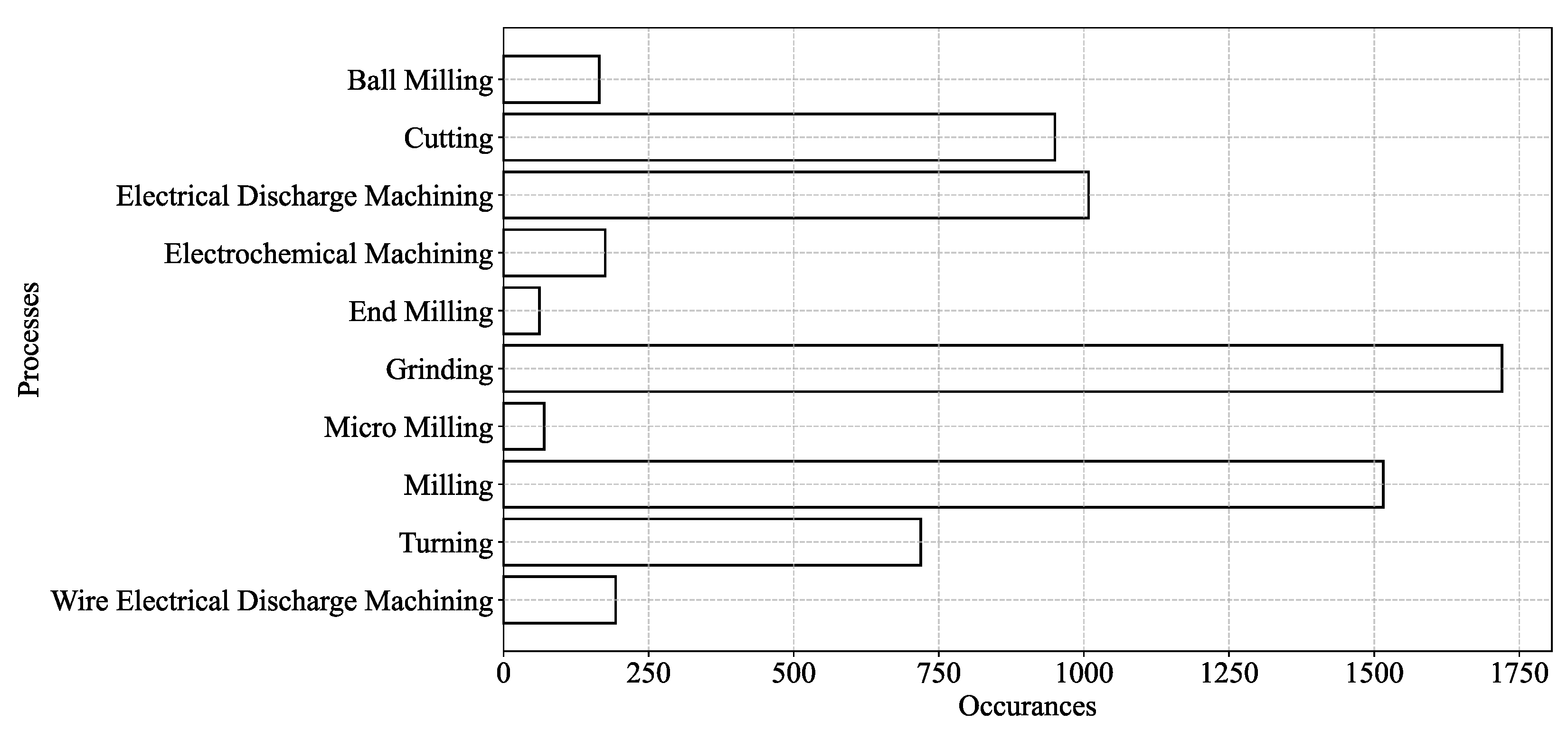

Appendix A: Section 2 (Literature Review)-Related Table and Figures

Appendix B: Access URL for Open Data

References

- Gupta, H.N. Manufacturing Process; 2nd ed.; New Age International Ltd: Daryaganj, New Delhi, 2009; ISBN 978-81-224-2844-5.

- Kalpakjian, S.; Schmid, S.R. Manufacturing Engineering and Technology; Eighth edition in SI units.; Pearson Education Limited: Harlow, 2023; ISBN 978-1-292-42224-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tlusty, J. Manufacturing Processes and Equipment; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2000; ISBN 978-0-201-49865-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, A.M.M.S. On the Interplay of Manufacturing Engineering Education and E-Learning. Int. J. Mech. Eng. Educ. 2016, 44, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.M.M.S.; Harib, K.H. Manufacturing Process Performance Prediction by Integrating Crisp and Granular Information. J. Intell. Manuf. 2005, 16, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, T.; Ghosh, A.K.; Ura, S. Toward Big Data Analytics for Smart Manufacturing: A Case of Machining Experiment. Proc. Int. Conf. Des. Concurr. Eng. Manuf. Syst. Conf. 2023, 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Fattahi, S.; Ura, S. Towards Developing Big Data Analytics for Machining Decision-Making. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 7, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazuyuki, M. Survey of Big Data Use and Innovation in Japanese Manufacturing Firms (Online); 2025;

- Beckmann, B.; Giani, A.; Carbone, J.; Koudal, P.; Salvo, J.; Barkley, J. Developing the Digital Manufacturing Commons: A National Initiative for US Manufacturing Innovation. Procedia Manuf. 2016, 5, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosarac, A.; Tabakovic, S.; Mladjenovic, C.; Zeljkovic, M.; Orasanin, G. Next-Gen Manufacturing: Machine Learning for Surface Roughness Prediction in Ti-6Al-4V Biocompatible Alloy Machining. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2023, 7, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, S.; Amarnath, M.K.; Marimuthu, K.; Subramaniam, P.; Rathinavelu, V.; Jagadeesh, D. Titanium Carbonitride–Coated CBN Insert Featured Turning Process Parameter Optimization during AA359 Alloy Machining. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 136, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teimouri, R.; Amini, S.; Mohagheghian, N. Experimental Study and Empirical Analysis on Effect of Ultrasonic Vibration during Rotary Turning of Aluminum 7075 Aerospace Alloy. J. Manuf. Process. 2017, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Suman, R.; Bahl, S.; Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Sharma, M.K.; Prakash, C.; Sehgal, S.; Singhal, P. Optimisation of Cutting Parameters during Turning of 16MnCr5 Steel Using Taguchi Technique. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. IJIDeM 2024, 18, 2055–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, J.; Ma, Z.; Jiang, C.; Yu, T.; Gu, R. Grinding Performance and Parameter Optimization of Laser DED TiC Reinforced Ni-Based Composite Coatings. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 134, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Maity, K. Hybrid Optimization Strategies for Improved Machinability of Nitronic-50 with MT-PVD Inserts. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 137, 221–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechagias, J. Multiparameter Signal-to-Noise Ratio Optimization for End Milling Cutting Conditions of Aluminium Alloy 5083. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 132, 4979–4988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahi, S.; Ullah, A.S. Optimization of Dry Electrical Discharge Machining of Stainless Steel Using Big Data Analytics. Procedia CIRP 2022, 112, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.A.K.; Ullah, A.M.M.S.; Anwar, S. Drilling High Precision Holes in Ti6Al4V Using Rotary Ultrasonic Machining and Uncertainties Underlying Cutting Force, Toolwear, and Production Inaccuracies. Materials 2017, 10, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongan, P.G.; Hinchy, E.P.; O’Dowd, N.P.; McCarthy, C.T.; Diaz-Elsayed, N. An Ensemble Neural Network for Optimising a CNC Milling Process. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 71, 377–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhali, R.; Bendjeffal, H.; Chetioui, K.B.; Bousba, I. Multivariable Optimization Based on the Taguchi Method to Study the Cutting Conditions in Aluminum Turning. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. IJIDeM 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usgaonkar, G.G.S.; Gaonkar, R.S.P. GRA and CoCoSo Based Analysis for Optimal Performance Decisions in Sustainable Grinding Operation. Int. J. Math. Eng. Manag. Sci. 2025, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R, M.K.; Ranganathan, R.; A, S.; Velu, R.; Jatti, V.S.; Mohan, D.G.; Vijayakumar, P. Achieving Multi-Response Optimization of Control Parameters for Wire-EDM on Additive Manufactured AlSi10Mg Alloy Using Taguchi-Grey Relational Theory. Eng. Res. Express 2025, 7, 015404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, D.; Yadav, S.; Singh, R.K.; Sharma, A.K. To Investigate the Effect of Discharge Energy and Addition of Nano-Powder on Processing of Micro Slots Using EDM Assisted µ-Milling Operation. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2025, 40, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, L.; Wu, B. A Novel Tolerance Optimization Approach for Compressor Blades: Incorporating the Measured out-of-Tolerance Error Data and Aerodynamic Performance. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2025, 158, 109920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boga, C.; Koroglu, T. Proper Estimation of Surface Roughness Using Hybrid Intelligence Based on Artificial Neural Network and Genetic Algorithm. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 70, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthick, M.; Anand, P.; Siva Kumar, M.; Meikandan, M. Exploration of MFOA in PAC Parameters on Machining Inconel 718. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2022, 37, 1433–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantheti, P.R.; Meena, K.L.; Chekuri, R.B.R. Maximizing Machining Efficiency and Quality in AA7075/Gr/B4 C HMMCs through Advanced DS-EDM Parameter Optimization Strategies. Eng. Res. Express 2024, 6, 045504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, S.; Mondal, S.C.; Kumar, A.; Ghadai, R.K. Performance Analysis and Optimization of Machining Parameters Using Coated Tungsten Carbide Cutting Tool Developed by Novel S3P Coating Method. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. IJIDeM 2024, 18, 3909–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wen, D.; Ran, X. A Multi-Sensor Monitoring Methodology for Grinding Wheel Wear Evaluation Based on INFO-SVM. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 208, 111003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Li, K.; Zheng, M.; Wang, C.; Chen, E. Research on Dynamic Characteristics of Turning Process System Based on Finite Element Generalized Dynamics Space. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 131, 4683–4698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Chen, M.; Gong, Y.; Gong, Q.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, M. Optimizing Grinding Parameters for Surface Integrity in Single Crystal Nickel Superalloys Using SVM Modeling. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 135, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, D.K.; Sahoo, B.; Mohanty, A.M. Experimental Analysis for Optimization of Process Parameters in Machining Using Coated Tools. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2024, 71, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathapalli, V.R.; Pittam, S.R.; Sarila, V.; Burragalla, D.; Gagandeep, A. Multi-Objective Parametric Optimization of AWJM Process Using Taguchi-Based GRA and DEAR Methodology. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2024, 238, 2845–2853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, T.-C.; Wu, S.-C.; Ullah, A.; Farooq, U.; Wang, I.-H.; Chang, S.-L. Integrating Numerical Techniques and Predictive Diagnosis for Precision Enhancement in Roller Cam Rotary Table. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 132, 3427–3445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanvir, M.H.; Hussain, A.; Rahman, M.M.T.; Ishraq, S.; Zishan, K.; Rahul, S.T.T.; Habib, M.A. Multi-Objective Optimization of Turning Operation of Stainless Steel Using a Hybrid Whale Optimization Algorithm. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2020, 4, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Yu, T.; Zhao, J. Assessment and Optimization of Grinding Process on AISI 1045 Steel in Terms of Green Manufacturing Using Orthogonal Experimental Design and Grey Relational Analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, D.K.; Sahoo, B.; Mohanty, A.M. Optimization of Process Parameter in AI7075 Turning Using Grey Relational, Desirability Function and Metaheuristics. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2023, 38, 1615–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanie, S.E.; Bogale, T.M.; Siyoum, Y.B. Optimization of Wire-Cut EDM Parameters Using Artificial Neural Network and Genetic Algorithm for Enhancing Surface Finish and Material Removal Rate of Charging Handlebar Machining from Mild Steel AISI 1020. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 136, 3505–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Qi, X.; Wang, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhang, S. Tool Wear Prediction Based on SVR Optimized by Hybrid Differential Evolution and Grey Wolf Optimization Algorithms. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 55, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, S.K.; Chauhan, A.; Banerjee, D.; Teyi, N.; Samanta, S. Developing Precision in WEDM Machining of Mg-SiC Nanocomposites Using Machine Learning Algorithms. Eng. Res. Express 2024, 6, 045435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painuly, M.; Singh, R.P.; Trehan, R. Investigation into Electrochemical Machining of Aviation Grade Inconel 625 Super Alloy: An Experimental Study with Advanced Optimization and Microstructural Analysis. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2025, 97, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanti, R.; Das, M. Sustainable EDM Production of Micro-Textured Die-Surfaces: Modeling and Optimizing the Process Using Machine Learning Techniques. Measurement 2025, 242, 115775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, H.; Ou, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, G. Analysis of Root Residual Stress and Total Tooth Profile Deviation in Hobbing and Investigation of Optimal Parameters. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2025, 58, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.-H.; Le, T.-T.; Nguyen, A.-T.; Hoang, X.-T.; Nguyen, N.-T.; Nguyen, N.-K. Optimization of Milling Conditions for AISI 4140 Steel Using an Integrated Machine Learning-Multi Objective Optimization-Multi Criteria Decision Making Framework. Measurement 2025, 242, 115837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, X.; Rupenyan, A.; Fassl, L.; Nabavi, M.; Lygeros, J. Plasma Spray Process Parameters Configuration Using Sample-Efficient Batch Bayesian Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 17th International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE); IEEE: Lyon, France, August 23, 2021; pp. 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Ao, S.; Xiang, S.; Yang, J. A Hyperparameter Optimization-Assisted Deep Learning Method towards Thermal Error Modeling of Spindles. ISA Trans. 2025, 156, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Dvivedi, A.; Tiwari, T.; Tewari, M. Predictive Modeling of Tool Wear in Rotary Tool Micro-Ultrasonic Machining. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2024, 238, 2160–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousnina, K.; Hamza, A.; Yahia, N.B. Design of an Intelligent Simulator ANN and ANFIS Model in the Prediction of Milling Performance (QCE) of Alloy 2017A. Artif. Intell. Eng. Des. Anal. Manuf. 2024, 38, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.M.M.S.; Harib, K.H. A Human-Assisted Knowledge Extraction Method for Machining Operations. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2006, 20, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M.Q.; Mehmood, A. Eco-Friendly Precision Turning of Superalloy Inconel 718 Using MQL Based Vegetable Oils: Tool Wear and Surface Integrity Evaluation. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 73, 112–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, M.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, D. A Multi-Criteria Decision-Making System for Selecting Cutting Parameters in Milling Process. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 65, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leese, M. The New Profiling: Algorithms, Black Boxes, and the Failure of Anti-Discriminatory Safeguards in the European Union. Secur. Dialogue 2014, 45, 494–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Alessandro, B.; O’Neil, C.; LaGatta, T. Conscientious Classification: A Data Scientist’s Guide to Discrimination-Aware Classification. Big Data 2017, 5, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmert-Streib, F.; Yli-Harja, O.; Dehmer, M. Artificial Intelligence: A Clarification of Misconceptions, Myths and Desired Status. Front. Artif. Intell. 2020, 3, 524339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bzdok, D.; Altman, N.; Krzywinski, M. Statistics versus Machine Learning. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 233–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; Always learning; 6. ed., international ed.; Pearson: Boston Munich, 2013; ISBN 978-0-205-89081-1.

- Miller, R.G.; Brown, B.W. Beyond ANOVA: Basics of Applied Statistics; Chapman & Hall texts in statistical science series; 1st ed.; Chapman & Hall: London ; New York, 1997; ISBN 978-0-412-07011-2.

- Dang, X.; Al-Rahawi, M.; Liu, T.; Mohammed, S.T.A. Single and Multi-Response Optimization of Scroll Machining Parameters by the Taguchi Method. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2024, 25, 1601–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwe, N.C.; Ozoegwu, C.G. Analyzing Empirically and Optimizing Surface Roughness and Tool Wear during Turning Aluminum Matrix/Rice Husk Ash (RHA) Composite. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 134, 1563–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhujani, F.; Abdullahu, F.; Todorov, G.; Kamberov, K. Optimization of Multiple Performance Characteristics for CNC Turning of Inconel 718 Using Taguchi–Grey Relational Approach and Analysis of Variance. Metals 2024, 14, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukrishnan, N.; Davim, J.P. Optimization of Machining Parameters of Al/SiC-MMC with ANOVA and ANN Analysis. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2009, 209, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureshkumar, B.; Navaneethakrishnan, G.; Panchal, H.; Manjunathan, A.; Prakash, C.; Shinde, T.; Mutalikdesai, S.; Prajapati, V.V. Effects of Machining Parameters on Dry Turning Operation of Nickel 200 Alloy. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. IJIDeM 2024, 18, 6023–6038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azawqari, A.A.; Amrani, M.A.; Hezam, L.; Baggash, M.; Abidin, Z.Z. Multi-Objectives Optimization of WEDM Parameters on Machining of AISI 304 Based on Taguchi Method. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 134, 5493–5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Malviya, S.K.; Pal, S.K.; Samantaray, A.K. Optimization of Quality Characteristics Parameters in a Pulsed Metal Inert Gas Welding Process Using Grey-Based Taguchi Method. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2009, 44, 1250–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Gill, S.S.; Mahajan, A. Experimental Investigation and Optimizing of Turning Parameters for Machining of Al7075-T6 Aerospace Alloy for Reducing the Tool Wear and Surface Roughness. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 33, 8745–8756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Chang, G.; Yang, J.; Zhao, M.; Li, J. Process Optimization of Robotic Polishing for Mold Steel Based on Response Surface Method. Machines 2022, 10, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy Sets as a Basis for a Theory of Possibility. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1999, 100, 9–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, D.; Foulloy, L.; Mauris, G.; Prade, H. Probability-Possibility Transformations, Triangular Fuzzy Sets, and Probabilistic Inequalities. Reliab. Comput. 2004, 10, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif Ullah, A.M.M.; Shamsuzzaman, M. Fuzzy Monte Carlo Simulation Using Point-Cloud-Based Probability–Possibility Transformation. SIMULATION 2013, 89, 860–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauris, G.; Lasserre, V.; Foulloy, L. A Fuzzy Approach for the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement. Measurement 2001, 29, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Shahinur, S.; Haniu, H. On the Mechanical Properties and Uncertainties of Jute Yarns. Materials 2017, 10, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahinur, S.; Ullah, A.S. Quantifying the Uncertainty Associated with the Material Properties of a Natural Fiber. Procedia CIRP 2017, 61, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.M.M. Surface Roughness Modeling Using Q-Sequence. Math. Comput. Appl. 2017, 22, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif Ullah, A.M.M.; Fuji, A.; Kubo, A.; Tamaki, J.; Kimura, M. On the Surface Metrology of Bimetallic Components. Mach. Sci. Technol. 2015, 19, 339–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.M.M.S. A.M.M.S. A Fuzzy Monte Carlo Simulation Technique for Sustainable Society Scenario (3S) Simulator. In Sustainability Through Innovation in Product Life Cycle Design; Matsumoto, M., Masui, K., Fukushige, S., Kondoh, S., Eds.; EcoProduction; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2017; pp. 601–618. ISBN 978-981-10-0469-8. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Ullah, A.S.; Teti, R.; Kubo, A. Developing Sensor Signal-Based Digital Twins for Intelligent Machine Tools. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2021, 24, 100242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- On the Full and Open Exchange of Scientific Data; National Academies Press: Washington, D.C., 1995; p. 18769; ISBN 978-0-309-30427-6.

- Orlowski, C. Smart Cities and Open Data. In Management of IOT Open Data Projects in Smart Cities; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 1–41 ISBN 978-0-12-818779-1.

| ID | Name of Workpiece Material | Number of Data |

| WM1 | Carbon steel for machine structure (S45C) | 289 |

| WM2 | Gray Cast Iron (FC20) | 142 |

| WM3 | Fiber-Reinforced Plastics (GFRP) | 103 |

| WM4 | Pure titanium (Ti) | 90 |

| WM5 | Ni-based heat-resistant alloys (Inconel 600) | 65 |

| WM6 | Ni-based heat-resistant alloy (Inconel X750) | 64 |

| WM7 | Stainless Steel (SUS304) | 55 |

| WM8 | Aluminum Alloy (AC3A) | 50 |

| WM9 | Aluminum alloy (Algin) | 50 |

| WM10 | Alloy Tool Steel (SKD11) | 42 |

| WM11 | High Carbon Chromium Bearing Steel (SUJ2) | 17 |

| WM12 | Nodular Graphite Cast Iron (FCD45) | 14 |

| WM13 | Alumina (Al2O3) | 13 |

| WM14 | Zirconia (ZrO2) | 12 |

| WM15 | Silicon nitrogen (Si3N4) | 4 |

| WM16 | Carbon silicon (SiC) | 3 |

| Workpiece Material | ID | Name of Tool Material | Number of Data |

| Carbon steel for machine structure (S45C), denoted as WM1 |

TM1 | Cermet: TiN-TaN | 68 |

| TM2 | Ceramics: TiCN-30TiB2-1TaN | 42 | |

| TM3 | Ceramics: TiCN-30TiB2-1Ta₂C | 40 | |

| TM4 | Coating: Al2O3 | 38 | |

| TM5 | Ceramics: TiCN-30TiB2 | 21 | |

| TM6 | Ceramics: TiN-30TiB2 | 21 | |

| TM7 | Coating: TiCN | 21 | |

| TM8 | Ceramics: Al2O3 | 15 | |

| TM9 | Ceramics: TiB2-30MoSi2 series | 13 | |

| TM10 | Ceramics: Si3N4-9Al2O3 | 7 | |

| TM11 | Ceramics: Si3N4-7Al2O3-25Si | 3 |

| Variable Types | Name of CVs | States |

| Control Variable (CVs) | Cutting Speed (vc) [m/min] | 200, 300, 400 |

| Feed (f) [mm/rev] | 0.1, 0.15 | |

| Machining Time (Tm) [min] | 1, 2.5, 5, 10,15, 20, 30 | |

| Evaluation Variable (EV) | Tool Wear (Tw) [mm] |

| CVs | Source of Variation | df | MS | F-value | P-value | Significant / Nonsignificant |

| vc | Between Groups | 2 | 0.225 | 16.75 | 1.4E-6 | Significant |

| Within Groups | 65 | 0.013 | ||||

| f | Between Groups | 1 | 0.178 | 10.24 | 0.002 | Significant |

| Within Groups | 66 | 0.017 | ||||

| Tm | Between Groups | 6 | 0.047 | 2.76 | 0.019 | Significant |

| Within Groups | 61 | 0.017 |

| CVs | Source of Variation | df | MS | F-value | P-value | Significant / Nonsignificant |

| vc | Between Groups | 2 | 0.029 | 5.901 | 0.006 | Significant |

| Within Groups | 39 | 0.005 | ||||

| f | Between Groups | 1 | 0.007 | 1.170 | 0.286 | Nonsignificant |

| Within Groups | 40 | 0.006 | ||||

| Tm | Between Groups | 6 | 0.026 | 9.211 | 4.56E-6 | Significant |

| Within Groups | 35 | 0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).