1. Introduction

The production of Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC) is independently responsible for about 7% of the total CO2 emissions worldwide [1]. This encouraged the researchers to looking for alternative solutions to reduce the use of OPC in concrete, consequently eliminating the CO2 emissions [2]. Generation of Construction and Demolition Waste (CDW) has become prominent worldwide. Being one of the largest sectors contributing to global solid waste production. Twenty-eight member states of the European Union generated a total 830 million Ton (Mt) of CDW in 2012, which accounts for approximately 1.65 Mt per year [3]. In 2015, United States generated a total of 548 Mt of CDW, which corresponds to nearly 1.7 Tons of CDW per capita [4]. Examples show that generation of CDW is a global issue. Unless controlled properly, large portions of CDW continue flow to the clean landfills and threaten the health of individuals and environment. CDWs have the potential of containing alkaline activation due to their aluminosilicate-rich nature. However, studies on the performance of CDWs in geopolymer synthesis are quite limited. It was shown that individual fractions of CDW-based materials such as tiles [5], bricks [6], glass [7], concrete [8], unbound aggregates [9], fire clay brick [10] can successfully be used in geo-polymerization. Geopolymers (alkali-activated materials) are green options that commonly produced by activating aluminosilicate wastes (i.e., precursors) by alkali hydroxides and silicates solutions [11]. Common industrial by-products (e.g., different classes of Fly Ash (FA) and Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag (GGBFS) are widely used in producing of geopolymer matrix [12]. Research on geopolymer has been reported for different sources of materials depending on their local availability and the production cost. Studies on the mechanical properties; in specific, compressive strength of geopolymer mortar or concrete made from fly ash or GGBS partially or fully replacement were reported in previous works. The main examined parameters were: activator molarity, activator ratios, curing methods, the temperature of heat curing, and the alkaline solution to binder ratio [13-24]. These studies concluded that the fly ash and GGBS can be successfully used in production of geopolymer matrix. However, no significant work has been reported on the use of other wastes such as; Ceramic Ball (CB), Fire Brick (FB), Ceramic Waste (CW), Glassy Sand (GS), Cement Kiln Dust (CKD), Grinded Aggregate (GA) and Silica Rock (SR). The current study investigated for the first time the potential of use these materials as binders for producing geopolymer matrix. Firstly, XRF test was conducted to choose the binders that could possibly used for producing geopolymer matrix. Secondly, for the chosen binders, the following parameters were examined: the curing conditions (ambient and heat curing 70 and 100 C0), the molarity of alkaline activator (10, 12, 15) M and the alkaline activator ratios (AR) sodium silicate (Na2SiO3) to sodium hydroxide (NaOH) (1:1, 1.5:1, 2:1, and 2.5:1). Furthermore, fly ash replacement for the chosen binders with 15% or 30% for specific specimens were also investigated. Finally, the performance of the produced geopolymer was evaluated in terms of the compressive strength at ages of 7, 14 and 28 days.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Binding Materials

Assorted resources of binding materials were adopted in this study according to their availability (naturally or waste-form found), namely; Ceramic Ball (CB), Fire Brick (FB), Ceramic Waste (CW), Glassy Sand (GS), Cement Kiln Dust (CKD), Grinded Aggregate (GA) and Silica Rock (SR) (See

Figure 1). XRF test was conducted to determine their chemical composition and ensure they met the requirement needed for producing geopolymer matrix [25],

Table 1, presents the results of the XRF tests.

2.2. Selected Binders

Fire brick and ceramic wastes were adopted in this study due to their chemical compositions, local availability and its low cost. The firebrick waste was collected from damaged lining of oil furnaces in petroleum refineries, whereas, the ceramic waste was obtained from the locally available deconstruction wastes (

Figure 2). The two CDW-based materials were initially crushed and then milled for final grinding.

Table 2, lists the chemical compositions of FA, FB, and CW CDW-based precursors as determined by X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis following the provisions of ASTM E1621-13 [26]. The results showed that FB and CW are rich in siliceous and aluminous oxides which are vital chemical compounds for the formation of calcium silicate aluminum hydrate (C-A-S-H) gel in geopolymer materials. These minerals (i.e., siliceous and aluminous oxides) enhanced the mechanical properties of the final products [27].

Table 2 also provides, the Loss on Ignition (L.O.I) (which is an indicator of the quality of the binder) obtained by measuring the content of the organic matter in the binder. It was determined in accordance with the guidelines of ASTM C114-18 [28].

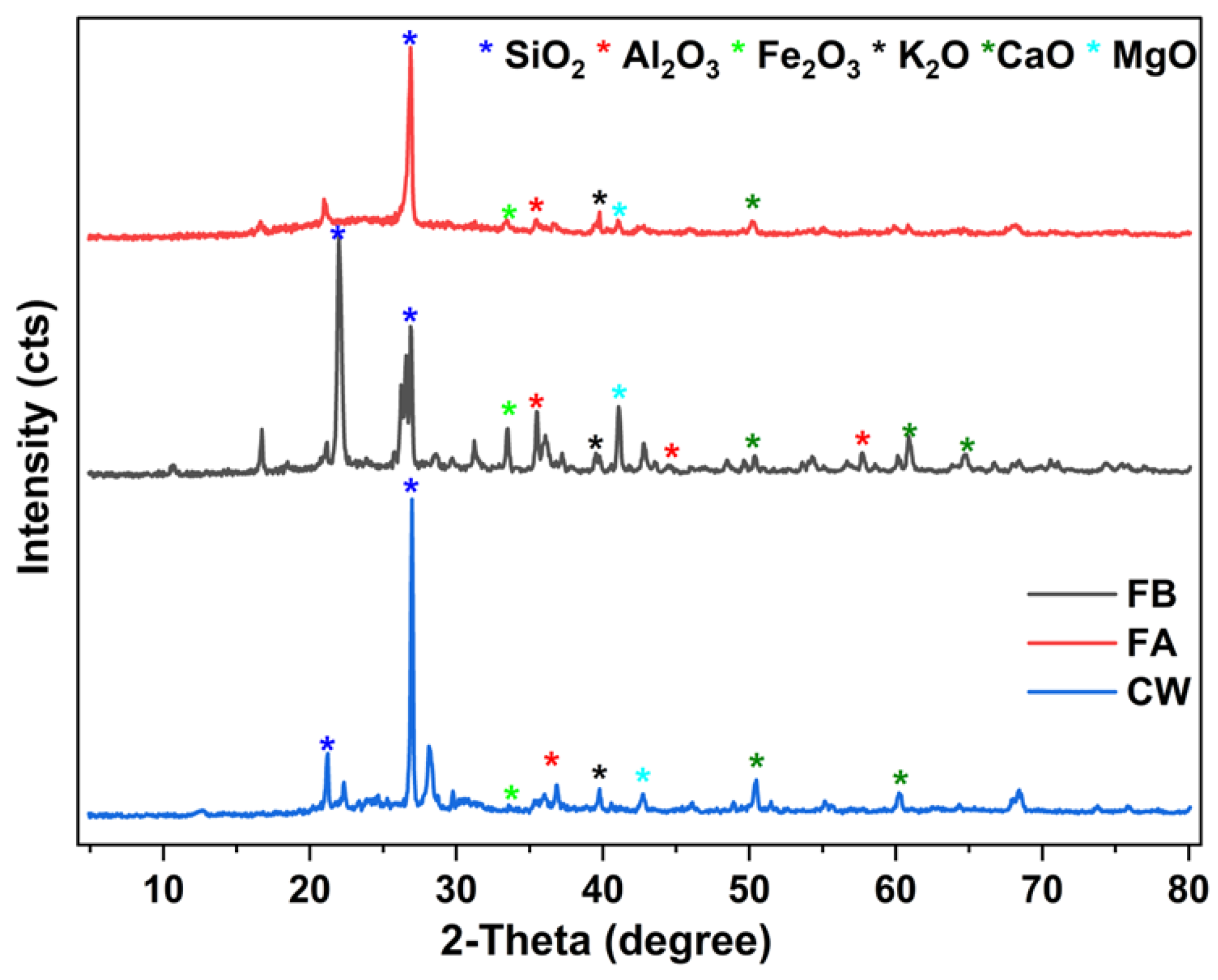

Figure 3, shows the crystalline structures of FB and CW which was analyzed using X-ray diffraction (XRD) technique. The XRD diffractograms identifies the characteristic peaks at 2θ = 26.976° and 2θ = 35.475°, corresponded to SiO

2 and Al

2O

3 oxides respectively. These characteristics are important to assess the pozzolanic potential of any supplementary cementitious material [25]. In the current study, the two binders showed low intensity diffraction peaks at 2θ = 33.23° belonging to Fe

2O

3 oxide, which provides a supporting role in strength gaining and pozzolanic mechanism with silica and alumina. Similar to alumina, it can be observed that the two binders presented diffractions peaks at 2θ = 50.457° related to CaO oxide. The presence of CaO oxide enhances the formation of Ca(OH)

2 which extends the formation of hydration products in proposed binders [29]. The studied binders also revealed diffraction peaks at 2θ = 39.773° for sodium and potassium oxides and 2θ = 41.023 - 42.725° for magnesium oxide, and 2θ = 33. 23°.Finally, the results from XRD patterns were well agreed with that obtained from XRF data.

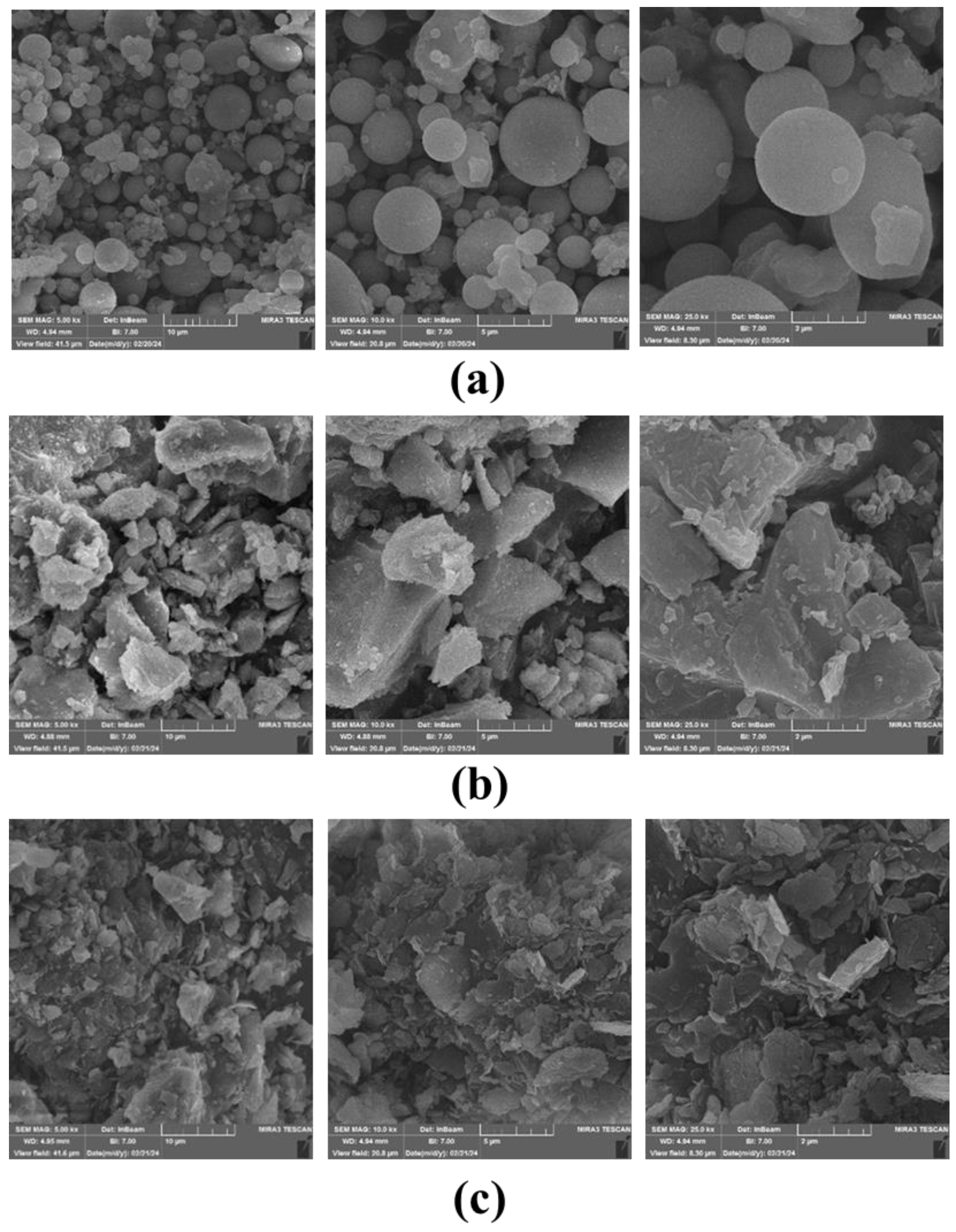

Figure 4 shows the morphology of FB and CW that was determined using Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FESEM) and elemental composition determined by Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX). The FESEM of fly ash (which is one of the most frequently used source materials in the production of geopolymer concrete) was also included for the sake of comparison (

Figure 4a). From this Figure, it can be seen that the particles of the fly ash appeared in spherical shape with various diameter ranging from 500 nm to 10 μm, due to various elements as shown in XRF results. Referring to

Figure 4b, the surface morphology of the CW had uneven particle shape, rough surface texture and sharp edges. While the FESEM observation of FB indicated that the FB particles have a nonhomogeneous and angular-shaped structure morphology as well as a flaky appearance (see

Figure 4c). In addition,

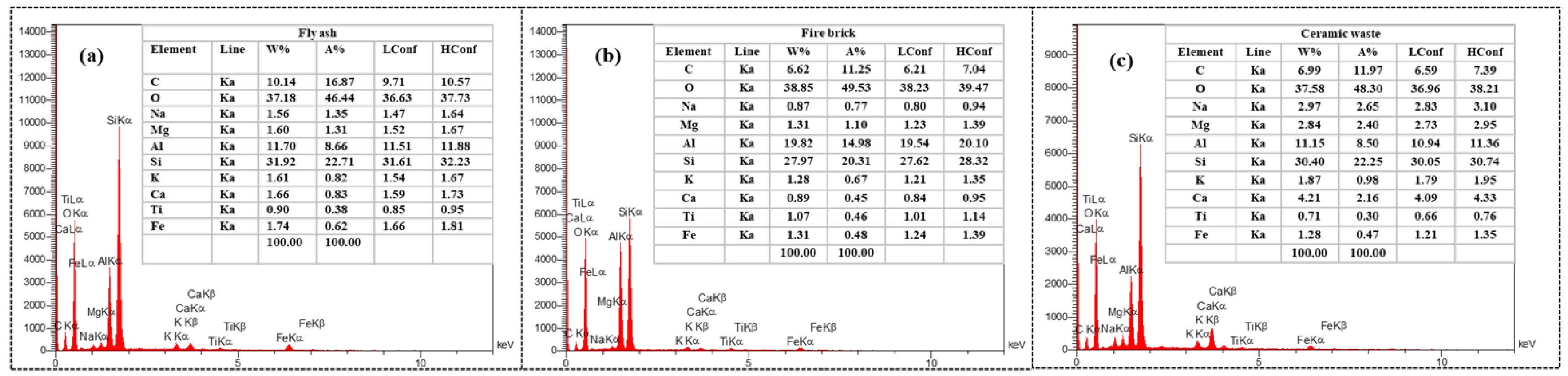

Figure 5, exhibits the EDX line spectra of the three binders, showed the presence of oxygen (O), silicon (Si) and aluminum (Al) as a main element with highest percentages for FB binder, with a trace of sodium (Na), calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg) and iron (Fe).

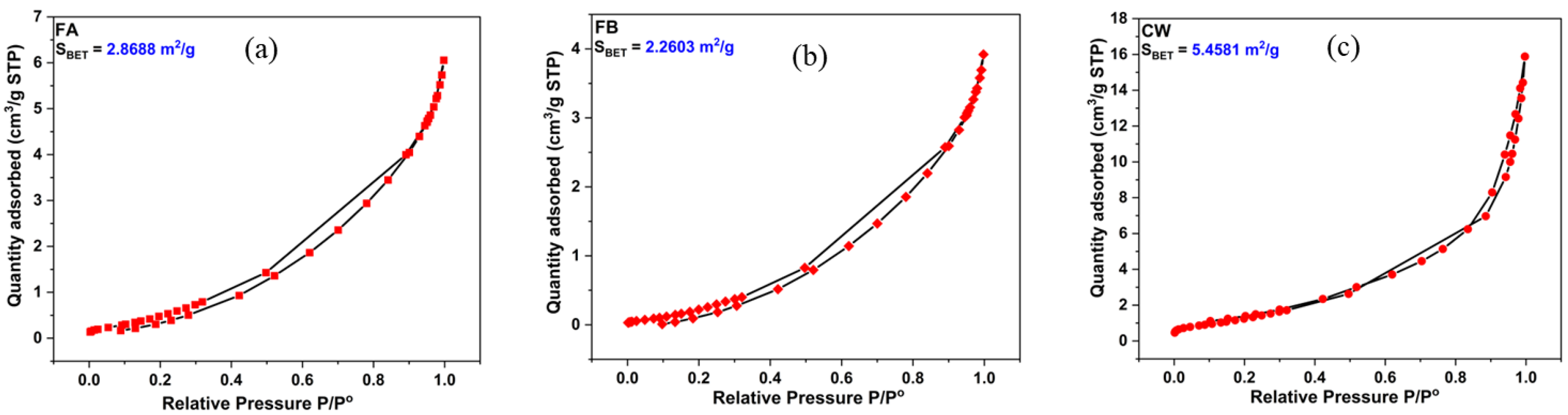

Figure 6 shows the calculated S

BET values (Specific surface area calculated by Brunauer-Emmett-Teller BET) method. This value was 2.8688 m

2/g, 2.2603 m

2/g and 5.4581 m

2/g for FA, FB and CW, respectively. The value of the total pore volume and mean pore diameter were 0.01250 cm

3/g and 5.449 nm for FA; 0.008276 cm

3/g and 5.483 nm for FB; and 0.02744 cm

3/g and 7.580 nm for CW. In general, higher specific area provides good interaction between the binder and activator, hence improving geopolymerization process and mechanical properties.

2.3. Preparation of Alkaline Activator

Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) and Sodium Silicate (Na2SiO3) was used as an alkaline activator. To prepare the alkali activator, firstly, a 10M sodium hydroxide solution was prepared by dissolving 400 g of sodium hydroxide NaOH (98%) flakes in 1L of water tab. Secondly, the solution was allowed to cool down to the room temperature for 24 hr. The 12M and15M sodium hydroxide solutions were, respectively prepared by dissolving 480 gm and 600 gm following the same procedure for 10M. Finally, the sodium silicate solution (13.1-13.7 % Na2O, 32-33% SiO2) was mixed with the previously prepared sodium hydroxide solutions. Previous studies showed that the combination of sodium silicate (SN) and sodium hydroxide (HN) led to enhance the geopolymerization reaction and increase the degree of gelation [29,30]. In addition, studies reported that the activator ratio; Na2SiO3 : NaOH of 2.5:1 usually led to the optimum mechanical properties of the produced geopolymer matrix [31,32]. In this study the activator ratios; Na2SiO3: NaOH (1:1, 1.5:1, 2:1, 2.5:1) were considered as a parameter under investigation which is a further step beyond the current state of the art.

2.4. Fine Aggregates

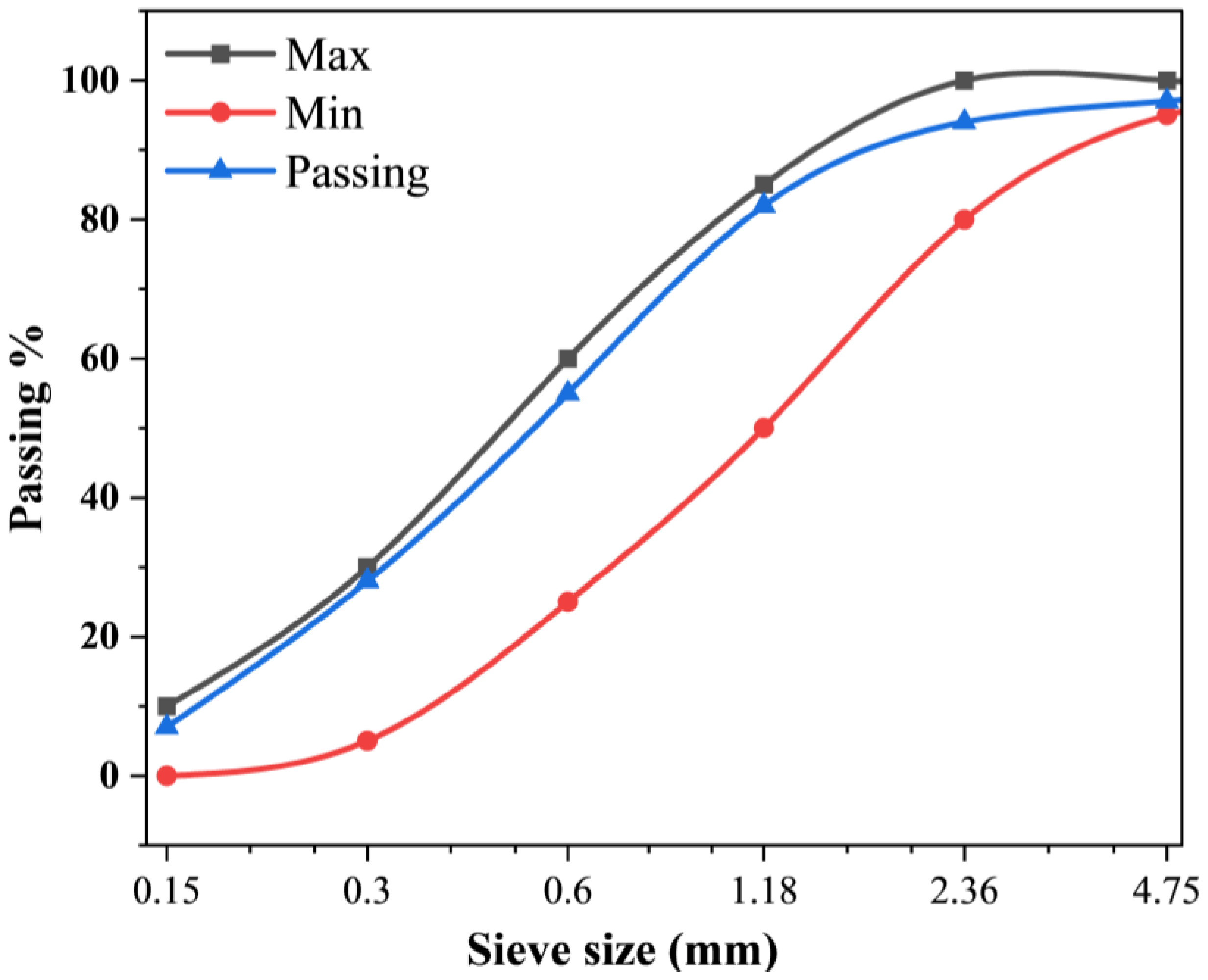

River sand was used as fine aggregate in this study with a nominal maximum grain size of 4.75 mm. The results of the sieve analysis are presented in

Figure 7. Gradation of the sand was tested according to the limit specified for the use in masonry mortar as per ASTM C33 / C33M-16 [33].

2.5. Trail Mixes

Several trail mixes were examined to select a mix ingredient that provided acceptable properties in terms of workability and compressive strength. For all mixes, the CDW-based material and sand were poured into a mixer and mixed for 1 minutes. Then, the alkali solution (the Liquid to Binder (L/B) ratio was 0.44) was slowly added to the mix and stirred for 4 minutes [7]. The fresh mixes were then cast into cubic molds measuring (50×50×50) mm (

Figure 8). Specimens were divided into three groups. The first group was left to cure at ambient temperature (40±2), the second and third group was treated with heat at temperature of 70 and 100 C

o for a period of 24 hrs. and then left to cure at ambient temperature to the day of testing at ages of 7, 14 and 28 days. Finally, compressive tests were conducted to evaluate the strength of the mortar using compression machine with a loading rate of 0.9 kN/s according to ACI Committee 437 [34]. Detailed of trial mixes proportions and resulted compressive strength are provided in

Table 3. According to this Table, trial mix No. 3 was adopted based on their workability and compressive strength.

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results of the compressive strength taking into the account the effect of type of CDW-based precursor (FB and CW), molarity (10, 12, and 15) M, curing methods (ambient and heat curing), and concentration/ratio of alkaline activator (1:1, 1:1.5, 1:2,1nd 1:2.5). The compressive strength was evaluated at ages of 7, 14, and 28 days. The total number of tested specimens was 396 spacemen. The specimen’s name followed Xm_Y_Z where X refers to the type of binder (FB: for fire brick and CW: for ceramic waste), m stands for molarity, Y denotes to the sodium silicate ratio, Z represents the curing method (A: for ambient curing, H: for heat curing (70 and 100 C0). The suffix R (FA replacement ratio) was added for those specimens that the fly ash replacement was included.

3.1. Compressive Strength

Table 4 presents the results of the compressive strength (average of three specimens) of geopolymer mortars. They were presented according to the activator concentrations, activator Ratio (AR), curing methods, and curing temperature. In the following sections, the effect of different parameters on the compressive strength development of geopolymer mortars is discussed separately.

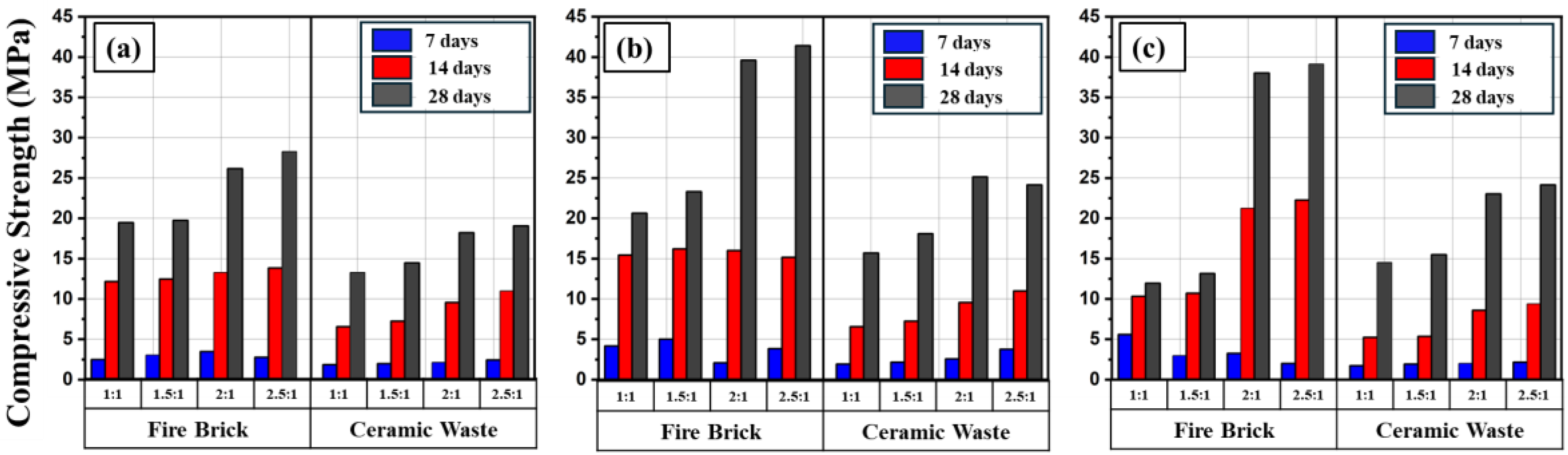

3.2. Type of Binder

Figure 9a-c presents the results of the compressive strength at different ages and at ambient curing condition. In general, the highest compressive strength recorded was for geopolymer mortars produced from fire brick for all activator concentrations, activator ratio, curing methods, and heat curing temperature. In specific, the higher compressive strength achieved was 39.6, 41.4, 38.0 and 39.1 MPa for specimens FB12_2_A, FB12_2.5_A, FB15_2_A and FB15-2.5_A respectively (

Table 4). Whereas, the maximum corresponding compressive strength of geopolymer mortars produced from ceramic waste was 25.2, 24.1, 23.0 and 24.2 MPa, for specimens CW12_2_A, CW12_2.5_A, CW15_S2_A and CW15_S2.5_A respectively.

The performance of fire brick over ceramic waste can be explained by its chemical composition. This material has high SiO2 (54.113%) and Al2O3 (22.394%) content, thus more Si and Al ions are solubilized during alkaline activation and participate in geopolymeric reactions for the formation of Si–O–Al bonds [35]. In contrast, the low compressive strength of CW could be attributed to the following reasons: (i) the existence of sodium and potassium oxides in CW binder materials may cause fast dehydration and thus reduced the efficiency of geopolymerization reaction; (ii) the presence of magnesium oxide in CW binder slightly lowered the mechanical strength of the produced geopolymer mortars [36]; (iii) the high content of CaO could also be the reason behind low compressive strength of CW geopolymer mortar since it consumes NaOH [37].

Figure (9a-c) show also the effect of the age of geopolymer mortar of both binders on the compressive strength. In general, a considerable enhancement in the strength from age 7 to 28 days was observed which agrees with the behavior of normal cement mortar.

3.3. Effect of Alkaline Activator

Three types of molarity (10, 12 and 15) M and four AR (1, 1.5, 2 and 2.5) were adopted.

Figure 9a-c presents the results of compressive strength of FB and CW based mortar with that molarity and activator ratio. For both two types of geopolymer, it can be seen that increasing the molarity of alkaline activator from 10 to 12 M resulted in noticeable enhancement in the compressive strength. However, after further increase of molarity to 15 M, a slight reduction in the compressive strength compared to the 12 M was observed. Nevertheless, the 15M specimens showed higher compressive strength than the counterpart specimens of 10 M. It was reported that the low concentrations of NaOH did not provide sufficient alkalinity in the matrix and formation of calcium silicate aluminum hydrate (C-A-S-H) gel in geopolymer matrix, consequently, the compressive strength weakened. Similarly, the high concentrations of NaOH may resulted in a residual alkali concentration that remains unreacted and thus reduced the strength [38]. This weakness in the strength could also be attributed to coagulation of silica and faster setting which does not allow for a homogenous mixing resulted in a poor and incipient polymerization [39].

In terms of activator ratio, it was noted that as Na2SiO3 increased, the compressive strength was also increased. The reason behind that was the formation of the geopolymer network depends on the Na2SiO3 concentration which responsible for the dissolution of the binder particles of the based geopolymer. However, above 2:1 AR, the increase in the compressive strength was margin (see Figure9), which might due to the high viscosity of the Na2SiO3 that inhibited the dissociation of the Al and Si into the network of the geopolymer [40].

Overall, it can be recommended that the optimum conditions that provide reasonable compressive strength for both types of geopolymer mortar in terms of molarity and activator ratio was 12M and 2:1, respectively.

3.4. Effect of Curing Temperature

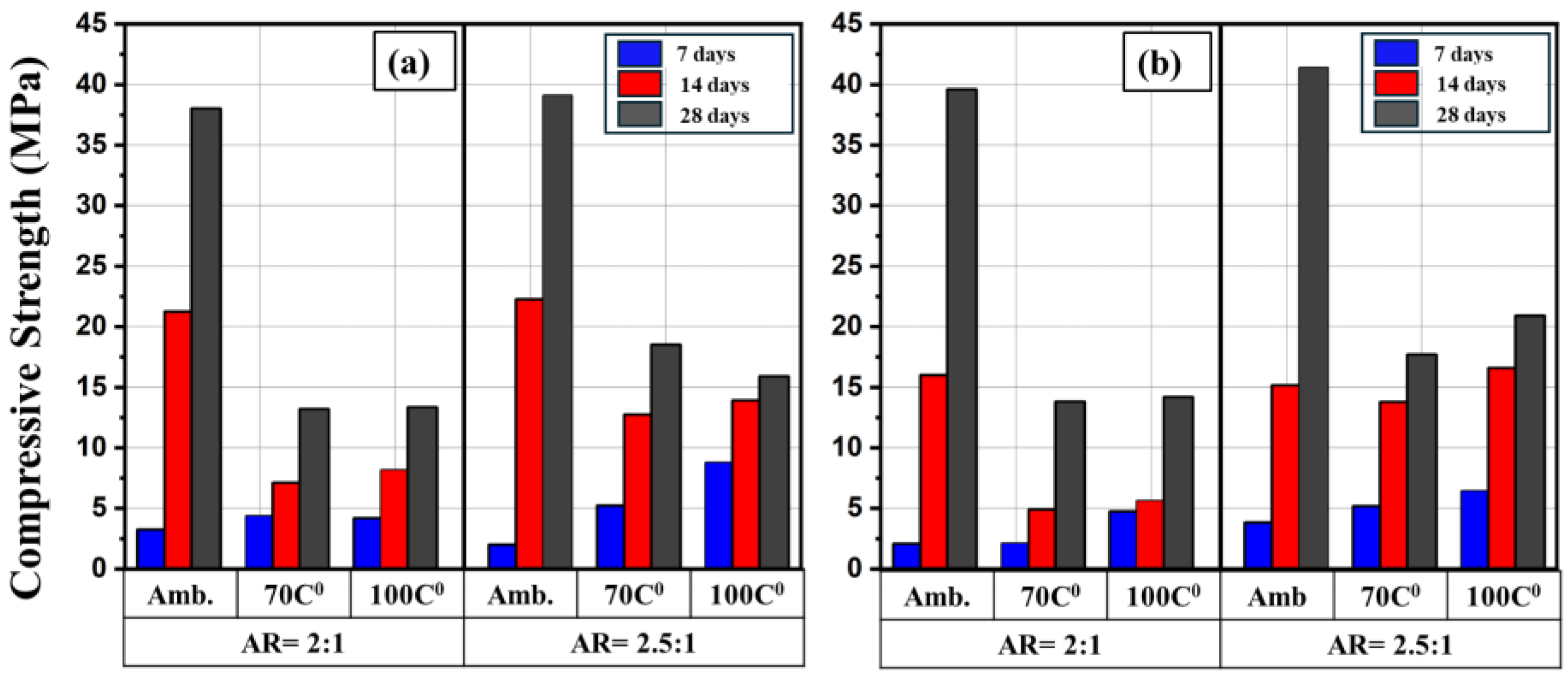

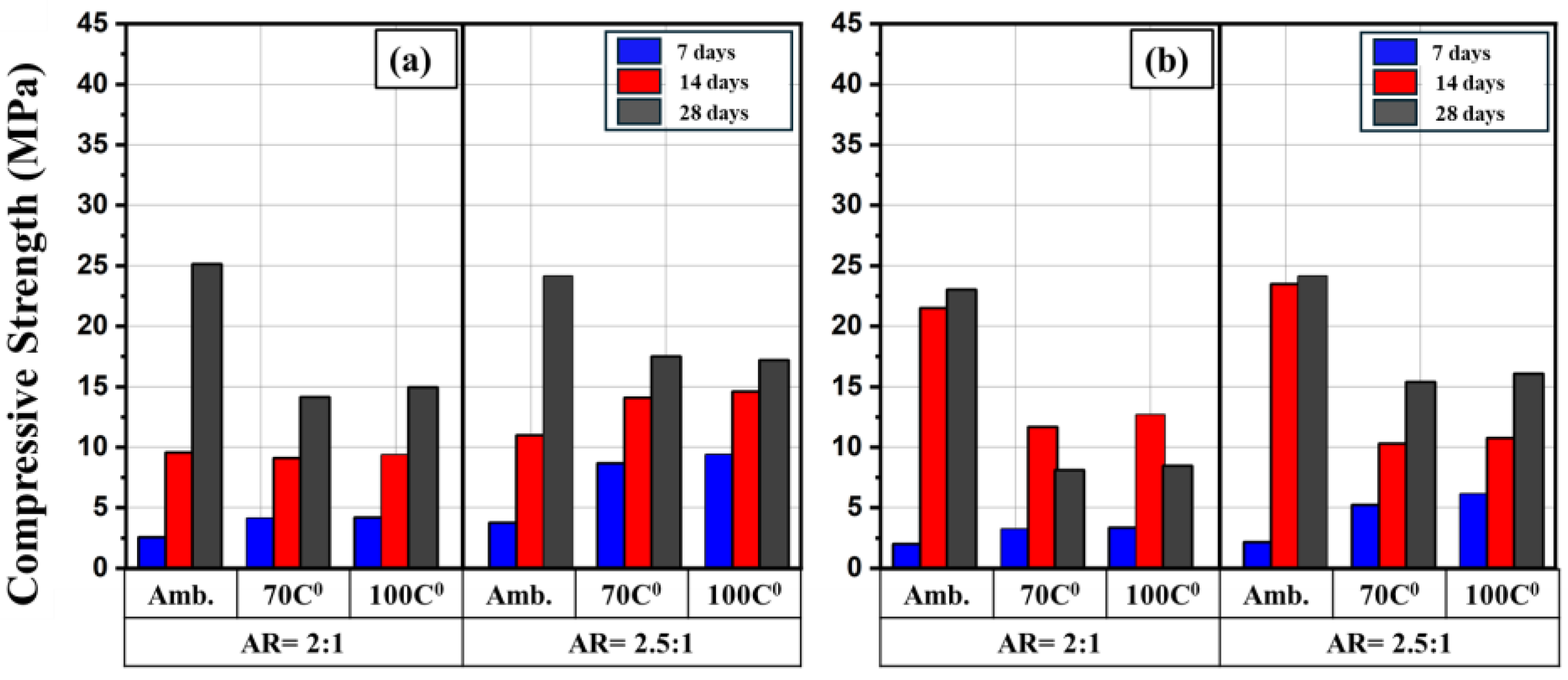

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 show the effect heat curing on the compressive strength in comparison with counterpart specimens cured at ambient conditions. The heat curing at high temperatures was compared with those specimens with molarity of 12M and 15M and AR of 2:1 and 2.5:1 as these molarity and AR showed the highest compressive strength. It can be seen that irrespective of the alkaline solution concentration and the type of binder, the highest compressive strength was achieved for those specimens that cured at ambient temperature. After further increase in the temperature to 70 C

0 a considerable decrease in the strength was noted. However, at temperature of 100 C

0, a slight increase in the strength in some of specimens was observed compared to 70 C

0. These findings agreed with results reported by Reig. et al. [41]. This would rise an important question on the curing temperature above 100 C

0 and curing time.

As mentioned, the highest compressive strength achieved was for those specimens that cured at ambient temperature. It was reported that when geopolymer mortars cured at low temperatures, the reaction products would have enough time to slowly fill the pores in the geopolymeric structure. This led to increase the density of the mortar [42], consequently, the compressive strength enhanced. It was also found that the compressive strength decreases with increasing the curing temperature. This probably due to presence of cracks at microscale that caused by excessive shrinkage and dehydration. In addition, curing at elevated temperatures could cause rapid geopolymerization reactions, giving a less ordered and more porous structures, which may reduce the compressive strength [43]. Another reason regarding low compressive strength noted at high curing temperatures can be related to the quality of reaction products that formed after geopolymerization. This may due to the fact that part of solution may evaporate at this temperature and thus did not contribute in geopolymerization reactions [44].

Overall, among all above parameters, it seems that the chemical composition of the source materials was the most effective factor influencing the compressive strength. This explains why the highest compressive strength was achieved for the FB based geopolymers despite the high crystallinity implying that although physical properties are highly important, chemical composition may be the main criterion that modify the mechanical response of geopolymers.

3.5. Fly Ash Replacement

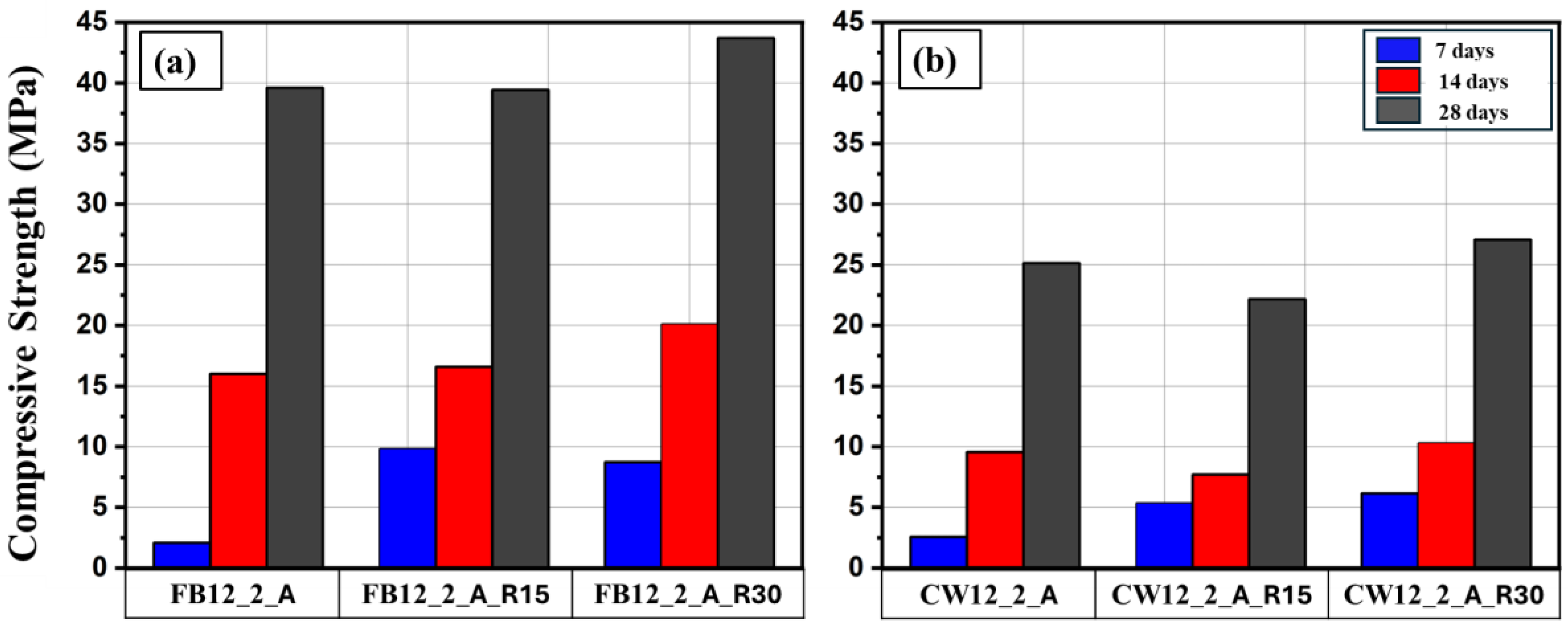

From

Table 4, it can be seen that the early strength (at 7 days) of all produced mortars was quite low. According to previous studies [45] using fly ash enhance the early strength of geopolymer; therefore, two percentages (15 and 30%) of the binding material was replaced by fly ash for those specimens of 12M and AR= 2.

Figure 12 demonstrates the effect of FA replacement on the compressive strength of geopolymer mortars. For FB-based mortar (

Figure 12a), a significant increase in the early strength (at 7 days) was observed, However, this was not the case for the CW-based mortar; as can be seen from

Figure 12b , the enhancement of the early strength was limited.

In terms of late strength (i.e., at 28 days), no clear conclusion can be drawn, however, it seems that using fly ash as a replacing did not affect the compressive strength. It could be attributed to the intrinsic properties of based binders in giving high strength at the late age.

4. Conclusions

This study investigates for the first time the potential of producing geopolymer mortar using Fire Brick (FB) and Ceramic Waste (CW) -based materials as a binder. The main tested parameters were; type of binder (FB and CW), the activator molarity (M) (10, 12, and 15M), the activator ratio; Na2SiO3 : NaOH (1:1, 1.5:1, 2:1, 2.5:1), curing conditions (ambient and heating to 70 and 100C◦) and replacement ratio of the binder by 15 and 30% of fly ash. The compressive strength was evaluated at age of 7, 14 and 28 days. According to the obtained results, the following conclusions can be drawn:

Both binders (FB and CW) can be a successful potential for production of geopolymer concrete.

Regardless the molarity, activator ratio and curing conditions, the FB- based mortar showed higher compressive strength than the counterpart CW-based mortar for all testing ages. This is due to the fact that the chemical composition (i.e. the content of SiO2, Al2O3, CaO, Fe2O3, and MgO) of the selected binder play important roles in the mechanical properties of the produced geopolymer concrete.

Different molarity of alkali activator (10, 12 and 15M) resulted in different compressive strength. In general, for both binders, increasing the molarity form 10 to 12 M resulted in a significant increase in the strength. However, beyond 12 M, a noticeable reduction in the compressive strength was observed compared to the 12M but still higher than the counterpart 10M specimens for all other parameters under investigations.

For both binder-based geopolymer mortar, the highest compressive strength achieved was for those specimens of molarity 12 M and Na2SiO3 : NaOH 2:1 and 2.5:1.

The results of the compressive strength of the two types of binders showed that the curing at ambient temperature was the more effective than the heat curing at 70 and 100 C◦.

Replacing 15 and 30% of FB and CW binders by fly ash significantly enhance the early strength (at 7 days). However, the corresponding increase at 28 days was almost negligible which confirm that the based binder was responsible for such strength.

Overall, the general conclusion, it appears that the chemical composition of the selected binder was the main factor that paly important role in enhancing the compressive strength of the resulted geopolymer.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OPC |

Ordinary Portland Cement |

| CDWs |

Construction and Demolishing Wastes |

| FB |

Fire brick |

| CW |

Ceramic Waste |

| FA |

Fly Ash |

| GGBFS |

Ground Granulated Blast Furnace Slag |

| AR |

activator ratios |

| CB |

Ceramic Ball |

| SR |

Silica Rock |

| GS |

Glassy Sand |

| CKD |

Cement Kiln Dust |

| GA |

Grinded Aggregate |

| XRF |

X-ray fluorescence |

| XRD |

X-ray diffraction |

| L.O.I |

Loss on Ignition |

| EDX |

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| FESEM |

Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope |

| BET |

Brunauer-Emmett-Teller |

| M |

Molarity |

| GPC |

Geopolymer concrete |

References

- Nguyen, T.K.L.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Nguyen, T.L.H.; Chang, S.W.; Nguyen, D.D.; Varjani, S.; Lei, Z.; Deng, L. Environmental impacts and greenhouse gas emissions assessment for energy recovery and material recycle of the wastewater treatment plant. Sci. Total Environ 2021, 784, 147135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zareei SA, Ameri F, Shoaei P, Bahrami N. Recycled ceramic waste high strength concrete containing wollastonite particles and micro-silica: A comprehensive experimental study. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 201, 11-32. [CrossRef]

- Deloitte, 2017. Study on resource efficient use of mixed wastes, improving management of construction and demolition waste – Final report. Prepared for the European Commission,DG ENV.

- U.S.E.P. Agency Office of Resource Conservation and Recovery, 2018. Construction and demolition debris generation in the United States.

- Yıldırım G, Kul A, Özçelikci E, Şahmaran M, Aldemir A, Figueira D, Ashour A. Development of alkali-activated binders from recycled mixed masonry-originated waste. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 33, 101690. [CrossRef]

- Tuyan M, Andiç-Çakir Ö, Ramyar K. Effect of alkali activator concentration and curing condition on strength and microstructure of waste clay brick powder-based geopolymer. Composites Part B: Engineering 2018, 135, 242-52. [CrossRef]

- Ulugöl H, Kul A, Yıldırım G, Şahmaran M, Aldemir A, Figueira D, Ashour A. Mechanical and microstructural characterization of geopolymers from assorted construction and demolition waste-based masonry and glass. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 280, 124358. [CrossRef]

- Robayo-Salazar RA, Valencia-Saavedra W, Mejía de Gutiérrez R. Construction and demolition waste (CDW) recycling—As both binder and aggregates—In alkali-activated materials: A novel re-use concept. Sustainability 2020, 12(14), 5775. [CrossRef]

- Bassani M, Tefa L, Russo A, Palmero P. Alkali-activation of recycled construction and demolition waste aggregate with no added binder. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 205, 398-413. [CrossRef]

- Silva G, Castañeda D, Kim S, Castañeda A, Bertolotti B, Ortega-San-Martin L, Nakamatsu J, Aguilar R. Analysis of the production conditions of geopolymer matrices from natural pozzolana and fired clay brick wastes. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 215, 633-43. [CrossRef]

- Provis JL, Lukey GC, Van Deventer JS. Do geopolymers actually contain nanocrystalline zeolites? A reexamination of existing results. Chemistry of materials 2005, 17(12), 3075-85. [CrossRef]

- Ryu GS, Lee YB, Koh KT, Chung YS. The mechanical properties of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete with alkaline activators. Construction and building materials 2013, 47, 409-18. [CrossRef]

- Nuaklong P, Sata V, Chindaprasirt P. Properties of metakaolin-high calcium fly ash geopolymer concrete containing recycled aggregate from crushed concrete specimens. Construction and Building Materials 2018, 161, 365-73. [CrossRef]

- Hu Y, Tang Z, Li W, Li Y, Tam VW. Physical-mechanical properties of fly ash/GGBFS geopolymer composites with recycled aggregates. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 226, 139-51. [CrossRef]

- Elyamany HE, Abd Elmoaty M, Elshaboury AM. Setting time and 7-day strength of geopolymer mortar with various binders. Construction and Building Materials 2018, 187, 974-83. [CrossRef]

- Bai T, Song Z, Wang H, Wu Y, Huang W. Performance evaluation of metakaolin geopolymer modified by different solid wastes. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 226, 114-21. [CrossRef]

- Huseien GF, Ismail M, Khalid NH, Hussin MW, Mirza J. Compressive strength and microstructure of assorted wastes incorporated geopolymer mortars: Effect of solution molarity. Alexandria engineering journal 2018, 57(4), 3375-86. [CrossRef]

- Singh S, Aswath MU, Ranganath RV. Effect of mechanical activation of red mud on the strength of geopolymer binder. Construction and Building Materials 2018, 177, 91-101. [CrossRef]

- Mustakim SM, Das SK, Mishra J, Aftab A, Alomayri TS, Assaedi HS, Kaze CR. Improvement in fresh, mechanical and microstructural properties of fly ash-blast furnace slag based geopolymer concrete by addition of nano and micro silica. Silicon 2021, 13, 2415-2428.

- Nurruddin MF, Sani H, Mohammed BS, Shaaban I. Methods of curing geopolymer concrete: A review. International Journal of Advanced and Applied Sciences 2018, 5(1), 31-6. [CrossRef]

- Komnitsas K, Zaharaki D, Vlachou A, Bartzas G, Galetakis M. Effect of synthesis parameters on the quality of construction and demolition wastes (CDW) geopolymers. Advanced Powder Technology 2015, 26(2), 368-76. [CrossRef]

- Sethi H, Bansal PP, Sharma R. Effect of addition of GGBS and glass powder on the properties of geopolymer concrete. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Civil Engineering 2019, 43, 607-617. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40996-018-0202-4#citeas.

- Alghannam M, Albidah A, Abbas H, Al-Salloum Y. Influence of critical parameters of mix proportions on properties of MK-based geopolymer concrete. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 2021, 46, 4399-4408. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13369-020-04970-0#citeas.

- Tan J, Cai J, Li X, Pan J, Li J. Development of eco-friendly geopolymers with ground mixed recycled aggregates and slag. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 256, 120369. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C618 (2008) Standard Specification for Coal Fly Ash and Raw or Calcined Natural Pozzolan for Use in Concrete.

- ASTM E1621-13, Standard Guide for Elemental Analysis by Wavelength Dispersive X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2013.

- Moudio AM, Tchakouté HK, Ngnintedem DL, Andreola F, Kamseu E, Nanseu-Njiki CP, Leonelli C, Rüscher CH. Influence of the synthetic calcium aluminate hydrate and the mixture of calcium aluminate and silicate hydrates on the compressive strengths and the microstructure of metakaolin-based geopolymer cements. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2021, 264, 124459. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C114-18, Standard Test Methods for Chemical Analysis of Hydraulic Cement, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2018.

- Saini G, Vattipalli U. Assessing properties of alkali activated GGBS based self-compacting geopolymer concrete using nano-silica. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2020, 12, e00352. [CrossRef]

- Yahya Z, Abdullah MM, Hussin K, Ismail KN, Abd Razak R, Sandu AV. Effect of solids-to-liquids, Na2SiO3-to-NaOH and curing temperature on the palm oil boiler ash (Si+ Ca) geopolymerisation system. Materials 2015, 8(5), 2227-42. [CrossRef]

- Al Bakri Abdullah MM, Kamarudin H, Ismail KN, Bnhussain M, Zarina Y, Rafiza AR. Correlation between Na2SiO3/NaOH ratio and fly ash/alkaline activator ratio to the strength of geopolymer. Advanced materials research 2012, 341, 189-93. [CrossRef]

- Abdullah MM, Kamarudin H, Bnhussain M, Ismail KN, Rafiza AR, Zarina Y. The relationship of NaOH molarity, Na2SiO3/NaOH ratio, fly ash/alkaline activator ratio, and curing temperature to the strength of fly ash-based geopolymer. Advanced Materials Research 2011, 328, 1475-82. [CrossRef]

- Görhan G, Kürklü G. The influence of the NaOH solution on the properties of the fly ash-based geopolymer mortar cured at different temperatures. Composites part b: engineering 2014, 58, 371-7. [CrossRef]

- ASTM C33 / C33M-16, Standard Specification for Concrete Aggregates, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2016.

- Walkley B, Ke X, Hussein OH, Bernal SA, Provis JL. Incorporation of strontium and calcium in geopolymer gels. Journal of hazardous materials 2020, 382, 121015. [CrossRef]

- Siddique S, Shrivastava S, Chaudhary S. Influence of ceramic waste as fine aggregate in concrete: Pozzolanic, XRD, FT-IR, and NMR investigations. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2018, 30(9), 04018227. [CrossRef]

- Ilcan H, Sahin O, Unsal Z, Ozcelikci E, Kul A, Demiral NC, Ekinci MO, Sahmaran M. Effect of industrial waste-based precursors on the fresh, hardened and environmental performance of construction and demolition wastes-based geopolymers. Construction and Building Materials 2023, 394, 132265.

- Panizza M, Natali M, Garbin E, Ducman V, Tamburini S. Optimization and mechanical-physical characterization of geopolymers with Construction and Demolition Waste (CDW) aggregates for construction products. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 264, 120158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120158. [CrossRef]

- Palomo A, Grutzeck MW, Blanco MT. Alkali-activated fly ashes: A cement for the future. Cement and concrete research 1999, 29(8), 1323-9. [CrossRef]

- Heah CY, Kamarudin H, Al Bakri AM, Bnhussain M, Luqman M, Nizar IK, Ruzaidi CM, Liew YM. Study on solids-to-liquid and alkaline activator ratios on kaolin-based geopolymers. Construction and Building Materials 2012, 35, 912-22. [CrossRef]

- Reig L, Tashima MM, Borrachero MV, Monzó J, Cheeseman CR, Payá J. Properties and microstructure of alkali-activated red clay brick waste. Construction and Building Materials 2013, 43, 98-106. [CrossRef]

- Mo BH, Zhu H, Cui XM, He Y, Gong SY. Effect of curing temperature on geopolymerization of metakaolin-based geopolymers. Applied clay science 2014, 99, 144-8. [CrossRef]

- Rovnaník P. Effect of curing temperature on the development of hard structure of metakaolin-based geopolymer. Construction and building materials 2010, 24(7), 1176-83. [CrossRef]

- Van Jaarsveld JG, Van Deventer JS, Lukey GC. The effect of composition and temperature on the properties of fly ash-and kaolinite-based geopolymers. Chemical Engineering Journal 2002, 89(1-3), 63-73. [CrossRef]

- Zhang HY, Kodur V, Qi SL, Cao L, Wu B. Development of metakaolin–fly ash based geopolymers for fire resistance applications. Construction and Building Materials 2014, 55, 38-45. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Different resources of binding materials.

Figure 1.

Different resources of binding materials.

Figure 2.

CDW-based materials: (a): Fire brick waste, (b): Ceramic waste.

Figure 2.

CDW-based materials: (a): Fire brick waste, (b): Ceramic waste.

Figure 3.

X-ray diffractograms of the FB and CW precursors.

Figure 3.

X-ray diffractograms of the FB and CW precursors.

Figure 4.

FESEM images of;(a): Fly ash, (b): Fire brick, (c): Ceramic Waste.

Figure 4.

FESEM images of;(a): Fly ash, (b): Fire brick, (c): Ceramic Waste.

Figure 5.

EDX results: (a): Fly ash, (b): Fire brick, (c): Ceramic Waste.

Figure 5.

EDX results: (a): Fly ash, (b): Fire brick, (c): Ceramic Waste.

Figure 6.

BET analysis of (a): Fly ash, (b): Fire brick, (c): Ceramic Waste.

Figure 6.

BET analysis of (a): Fly ash, (b): Fire brick, (c): Ceramic Waste.

Figure 7.

Sieve analysis of fine aggregate.

Figure 7.

Sieve analysis of fine aggregate.

Figure 8.

Stages of preparation, casting, and testing of the mortar mixes.

Figure 8.

Stages of preparation, casting, and testing of the mortar mixes.

Figure 9.

Effect of the type of the binder and activator ratio on the compressive strength at ambient curing condition and different ages for different molarity; (a) 10 Molarity, (b) 12 Molarity and (c) 15 Molarity for ambient curing method.

Figure 9.

Effect of the type of the binder and activator ratio on the compressive strength at ambient curing condition and different ages for different molarity; (a) 10 Molarity, (b) 12 Molarity and (c) 15 Molarity for ambient curing method.

Figure 10.

Comparison of compressive strength of FB-based geopolymer mortars at different curing conditions and ages; (a) 12 M and (b) 15 M.

Figure 10.

Comparison of compressive strength of FB-based geopolymer mortars at different curing conditions and ages; (a) 12 M and (b) 15 M.

Figure 11.

Comparison of compressive strength of CW-based geopolymer mortars at different curing conditions and ages; (a) 12 M and (b) 15 M.

Figure 11.

Comparison of compressive strength of CW-based geopolymer mortars at different curing conditions and ages; (a) 12 M and (b) 15 M.

Figure 12.

Figure 12. Effect of 15 and 30% replacing of FB and CW- based binder by fly ash on the compressive strength at different ages; (a) FB, (b) CW

Figure 12.

Figure 12. Effect of 15 and 30% replacing of FB and CW- based binder by fly ash on the compressive strength at different ages; (a) FB, (b) CW

Table 1.

Chemical composition of assorted binding materials based of XRF test.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of assorted binding materials based of XRF test.

| Type of Binding Material |

Chemical Composition % |

| SiO2

|

Al2O3

|

CaO |

Fe2O3

|

MgO |

Na2O |

K2O |

MnO |

TiO2

|

P2O5

|

| Ceramic Ball |

68.48 |

22.19 |

1.04 |

0.03 |

0.28 |

1.2 |

0.95 |

0.24 |

0.02 |

0.27 |

| Fire Brick* |

54.11 |

22.4 |

4.432 |

2.94 |

0.606 |

0.158 |

0.953 |

0.03 |

1 |

0.071 |

| Aggregates |

71.4 |

2.54 |

11.2 |

0.37 |

1.6 |

12.25 |

0.36 |

0.10 |

0.16 |

0.2 |

| Glassy sand |

92.16 |

6.69 |

1.16 |

0.20 |

0.61 |

0.02 |

0.1 |

0.02 |

0.20 |

0.12 |

| Silica Rocks |

97.01 |

0.306 |

0.052 |

0.775 |

0.063 |

0.041 |

0.057 |

0.02 |

0.32 |

0.16 |

| Ceramic Waste* |

49.5 |

20.303 |

2.43 |

6.62 |

4.43 |

1.9 |

1.596 |

0.043 |

0.678 |

0.074 |

| Cement Kiln Dust |

15.6 |

3.72 |

45.36 |

2.6 |

1.9 |

3.16 |

2.74 |

0.45 |

0.25 |

0.17 |

Table 2.

Chemical composition of the selected precursors.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of the selected precursors.

| Chemical Compound |

Fly Ash |

Fire Brick |

Ceramic Waste |

| SiO2 |

51.999 |

54.113 |

49.113 |

| Al2O3 |

18.273 |

22.394 |

20.303 |

| Fe2O3 |

7.288 |

2.94 |

6.62 |

| CaO |

3.145 |

4.432 |

2.432 |

| MgO |

1.191 |

0.606 |

4.427 |

| Na2O |

0.683 |

0.158 |

1.897 |

| K2O |

1.296 |

0.953 |

1.596 |

| TiO2 |

0.949 |

1.196 |

0.678 |

| MnO |

0.055 |

0.03 |

0.043 |

| P2O5 |

0.199 |

0.071 |

0.074 |

| LOI |

14.87 |

13.45 |

12.2 |

| SUM |

99.948 |

100.343 |

99.383 |

Table 3.

Trail mix Details.

Table 3.

Trail mix Details.

| Mix No. |

Mix Details |

Testing Results |

| L/B |

Binder |

Sand |

Workability (mm) |

Compressive Strength (MPa) |

| 1 |

0.44 |

1 |

1.33 |

90 |

15 |

| 2 |

0.44 |

1 |

1.25 |

95 |

17 |

| 3 |

0.44 |

1 |

1.00 |

100 |

23 |

| 4 |

0.44 |

1 |

2.25 |

60 |

12 |

| 5 |

0.42 |

1 |

1.70 |

75 |

14 |

Table 4.

Test results.

| No |

Mix |

Compressive Strength (MPa) |

No |

Mix |

Compressive Strength (MPa) |

|

7

(day) |

14

(day) |

28

(day) |

7 (day) |

14

(day) |

28

(day) |

|

| 1 |

FB10_1_A |

2.5 |

12.2 |

19.5 |

23 |

CW10_1_A |

1.8 |

6.1 |

13.3 |

|

| 2 |

FB10_1.5_A |

3.0 |

12.5 |

19.8 |

24 |

CW10_1.5_A |

2.0 |

7.0 |

14.5 |

|

| 3 |

FB10_12_A |

3.5 |

13.3 |

26.2 |

25 |

CW10_12_A |

2.1 |

8.6 |

18.2 |

|

| 4 |

FB10_2.5_A |

2.8 |

13.8 |

28.3 |

26 |

CW10_2.5_A |

2.4 |

9.5 |

19.1 |

|

| 5 |

FB12_1_A |

4.2 |

15.4 |

20.6 |

27 |

CW12_S_A |

1.9 |

6.6 |

15.7 |

|

| 6 |

FB12_1.5_A |

5.0 |

16.2 |

23.3 |

28 |

CW12_1.5_A |

2.2 |

7.3 |

18.1 |

|

| 7 |

FB12_2_A |

2.1 |

16.0 |

39.6 |

29 |

CW12_2_A |

2.6 |

9.6 |

25.2 |

|

| 8 |

FB12_2.5_A |

3.8 |

15.2 |

41.4 |

30 |

CW12_2.5_A |

3.8 |

11.0 |

24.1 |

|

| 9 |

FB15_1_A |

5.6 |

10.3 |

12.0 |

31 |

CW15_S1_A |

1.7 |

5.2 |

14.5 |

|

| 10 |

FB15_1.5_A |

3.0 |

10.7 |

13.2 |

32 |

CW15_S1.5_A |

1.9 |

5.4 |

15.5 |

|

| 11 |

FB15_2_A |

3.2 |

21.2 |

38.0 |

33 |

CW15_S2_A |

2.0 |

8.6 |

23.0 |

|

| 12 |

FB15-2.5_A |

2.0 |

22.3 |

39.1 |

34 |

CW15_S2.5_A |

2.2 |

9.4 |

24.2 |

|

| 13 |

FB12_2_H70

|

2.1 |

4.9 |

13.8 |

35 |

CW12_2_H70

|

4.1 |

9.1 |

14.2 |

|

| 14 |

FB12_2_H100

|

4.8 |

5.6 |

14.2 |

36 |

CW12_2_H100

|

4.2 |

9.4 |

15.0 |

|

| 15 |

FB12_2.5_H70

|

5.2 |

13.8 |

17.7 |

37 |

CW12_2.5_H70

|

8.7 |

14.1 |

17.5 |

|

| 16 |

FB12_2.5_H100

|

6.5 |

16.6 |

20.9 |

38 |

CW12_2.5_H100

|

9.4 |

14.6 |

17.2 |

|

| 17 |

FB15_2_H70

|

4.4 |

7.1 |

13.2 |

39 |

CW15_2_H70

|

3.2 |

4.7 |

8.1 |

|

| 18 |

FB15_2_H100

|

4.2 |

8.2 |

13.4 |

40 |

CW15_ 2_H100

|

3.4 |

5.1 |

8.5 |

|

| 19 |

FB15_2.5_H70

|

5.2 |

12.7 |

18.5 |

41 |

CW15_2.5_H70

|

5.2 |

10.3 |

15.4 |

|

| 20 |

FB15_2.5_H100

|

8.8 |

13.9 |

15.9 |

42 |

CW15_2.5_H100

|

6.2 |

10.8 |

16.1 |

|

| 21 |

FB12_2_A_R15 |

8.7 |

16.6 |

39.4 |

43

|

CW12_2_A_R15 |

5.4 |

7.7 |

22.2 |

|

| 22 |

FB12_2_A_R30 |

9.8 |

20.1 |

43.7 |

44

|

CW12_2_A_R30 |

6.2 |

10.3 |

27.1 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).