1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a wide range of implications at the medical, social, political, and financial levels [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Although the introduction of the genetically engineered vaccine, mRNA vaccine, live adenovirus vector vaccine, and inactivated vaccine effectively controlled the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and considerably reduced the severe morbidity and mortality associated with COVID-19, toward the end of 2020, there have been numerous mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 strains [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Owing to the enhancement of the immune escape ability of the mutants, the proportion of mutants in the global epidemic strains has rapidly increased, demonstrating a stronger transmission advantage [

9,

10]. The neutralizing ability of the neutralizing antibodies produced during previous infections decreased in some mutants, which has raised concerns regarding the “viral immune escape [

11,

12].” Therefore, it is important to closely monitor future virus mutations and other types of transmission. There is an urgent requirement to develop universal and novel coronavirus vaccines and drugs.

SARS-CoV-2 is the seventh coronavirus that causes infection in humans in addition to low pathogenic members HCoV-OC43, HCoV-HKU1, HCoV-NL63, and HCoV-229E, as well as highly pathogenic SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV [

13]. The genome of SARS-CoV-2 is approximately 30,000 bases comprising two large overlapping open reading frames (ORF1a and ORF1b) and encodes four structural proteins, namely spike, envelope, membrane, and nucleocapsid (N) proteins, as well as nine contactable proteins [

14]. ORF1a and ORF1b undergo further processing to produce 16 nonstructural proteins (Nsp1–16) [

13]. Among the virus proteins, N protein is the core component of the virus [

15]. It is a heterostructure, 419 amino acid long, multidomain RNA binding protein. Similar to other novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2 N protein has two conserved, independently folded domains, called N-terminal domain (NTD) and C-terminal domain (CTD) that are connected by an inherently disordered region (IDR) called the central linking region (LKR) [

16]. LKR includes a Ser/Arg (SR)-rich region that contains putative phosphorylation sites. In addition, there are usually two IDRs on both sides of the NTD and CTD of the coronavirus known as the N-arm and C-tail, respectively [

16,

17]. NTD, CTD, and IDR are responsible for RNA binding, RNA binding and dimerization, and regulating RNA binding activity and oligomerization of NTD and CTD, respectively [

15,

18].

Among the novel coronavirus proteins, N protein is also the most abundant protein in the virion and is the decisive factor of virulence and pathogenesis [

19]. It binds to the viral genomic RNA and packages the RNA into a ribonucleoprotein complex [

14,

15,

19]. In addition to assembly, N proteins have other functions, including transcription and replication of viral mRNA and immune regulation [

20]. In particular, the N protein of SARS-CoV-2 has been found to counteract the host RNAi-mediated antiviral response through its double-stranded RNA binding activity as a viral inhibitor for RNA silencing, thus, making it a key target for diagnosis and vaccine and drug development [

13,

19,

20,

21].

However, the basic function of N proteins is to bind genomic RNA and form protective nucleocapsids in mature viruses [

14,

22,

23]. The inherent ability of N protein to interact with nucleic acid makes its purification very challenging [

22,

24]. Moreover, N proteins can undergo liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS) and promote the formation of dense liquid condensates, thereby increasing the difficulty of its purification [

15,

25,

26,

27]. Notably, there are significant differences in the structure and phase separation properties between nucleic acid contaminated and uncontaminated N proteins [

24]. Nucleic acid contamination may seriously affect the molecular properties of purified N protein, and thus, hamper the results of subsequent research and development of vaccines and drugs from N proteins. Polyethyleneimine (PEI) is a linear polymer, and the structural formula of its repeat unit is (-CH

2CH

2-NH-)n [

28]. The n value is generally 700–2,000, and the overall molecular weight of the polymer is 30–90 kDa. The presence of numerous repeated imine units makes PEI rich in positive charge in near-neutral solution, and thus, PEI can adsorb negatively charged biomolecules, such as nucleic acids or acidic proteins, form complexes, and initiate flocculation, resulting in the coprecipitation of PEI and bound biomolecules [

28,

29,

30,

31]. Therefore, this study utilizes the characteristics of PEI binding to nucleic acids to remove nucleic acids from the N protein. This is followed by ammonium sulfate precipitation, dialysis, and nickel column purification to obtain the uncontaminated N protein.Thus, a simple process for the purification of full-length N protein without nucleic acid contamination was developed. At the same time, combined with virtual screening, inhibitors for nucleocapsid proteins were developed.

2. Result

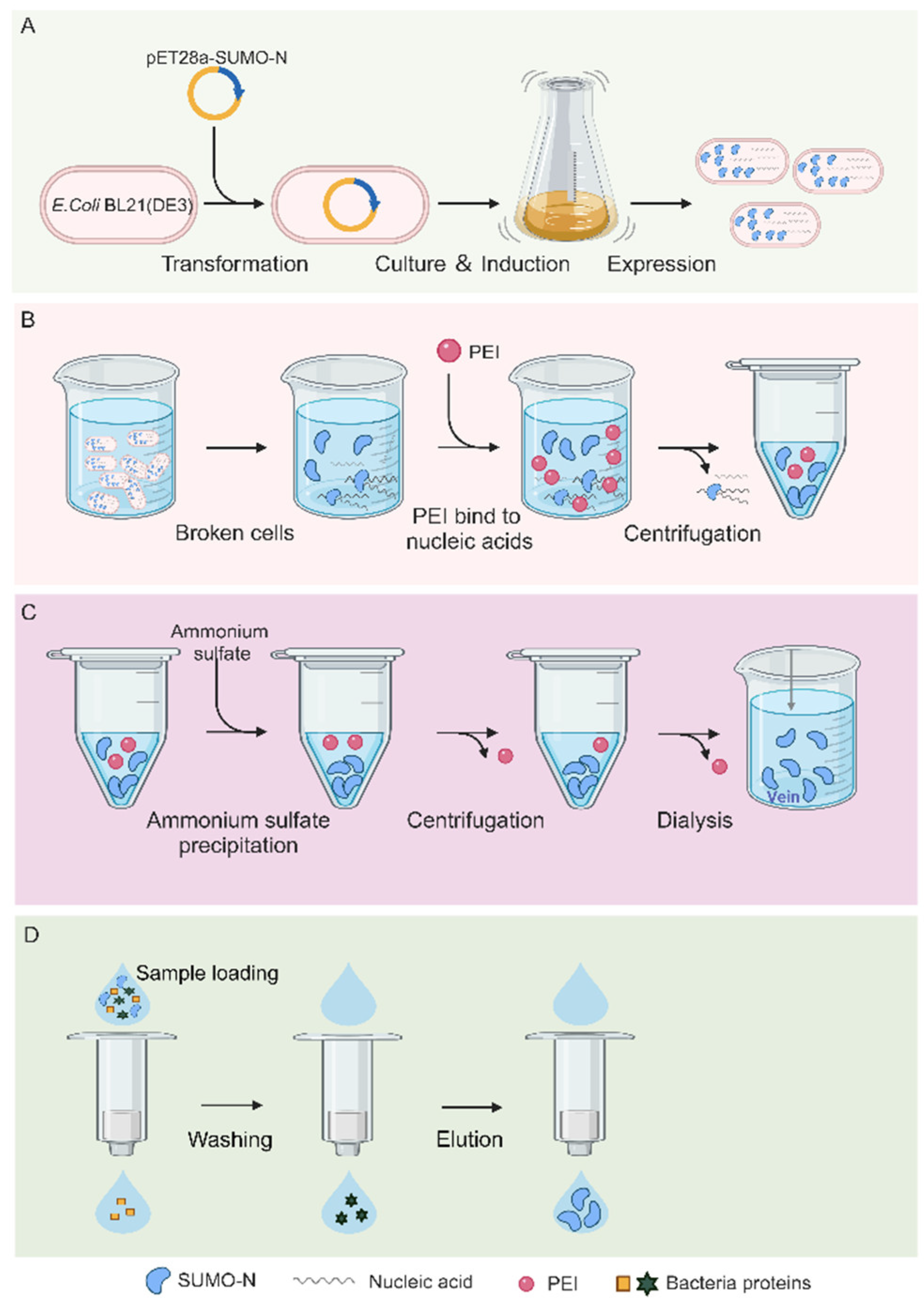

2.1. Purification Process of N Protein

To obtain the N protein without nucleic acid contamination, the purification process was designed as follows (

Figure 1): First, the soluble N protein was expressed in E. coli (

Figure 1A), and second, the nucleic acid in the N protein was removed using the characteristic of PEI binding to nucleic acid (

Figure 1B). Then, the N protein was precipitated with ammonium sulfate, and the free PEI that did not bind the nucleic acid was retained in the supernatant (

Figure 1C). The N protein was enriched by centrifugation, and the free PEI was removed. The dialysis step completely removed the residual PEI and ammonium sulfate, and finally, the purified N protein was obtained by nickel column purification (

Figure 1D). The experimental results of each step are described in detail below.

2.2. Prokaryotic Expression System

Compared with the eukaryotic expression system, the prokaryotic expression system has the advantages of high efficiency and low cost.

E. coli is a good choice for expressing N protein. It was previously reported that soluble N protein could be expressed under mild induction conditions, but the expression level was very low [

32]. Solubilizing the protein by fusing and expressing SUMO considerably increased the expression of soluble N protein [

24]. Therefore, in this study, we fused the N protein with SUMO for expression.

2.3. Ultrasonic Fragmentation

Initially, the collected bacteria were resuspended in the conventional buffer B, and it was observed that the broken liquid was turbid. Even if these aggregates are removed by high-speed centrifugation, the supernatant will slowly continue to appear as flocs, causing the solution to become sticky. The results indicated that the LLPS phenomenon occurred due to the release of bacterial nucleic acid by fragmentation and binding of the N protein to nucleic acid (no shown). Under the condition of low salt concentration, N protein can bind to nucleic acid, and LLPS phenomenon occurs automatically [

25,

27]. The positively charged N protein has an electrostatic effect with negatively charged RNA/DNA that drives the formation of condensates [

25]. When we use buffer A with high salt concentration (1M NaCl) to break up the suspension, the broken solution is clarified, and no obvious LLPS phenomenon occurs. Adding solid NaCl directly to the broken supernatant where the LLPS phenomenon occurs can reverse the LLPS phenomenon. The results indicated that increasing the salt concentration can prevent or weaken the formation of LLPS. Finally, the buffer containing 1M NaCl was selected as the buffer of choice for ultrasonic fragmentation.

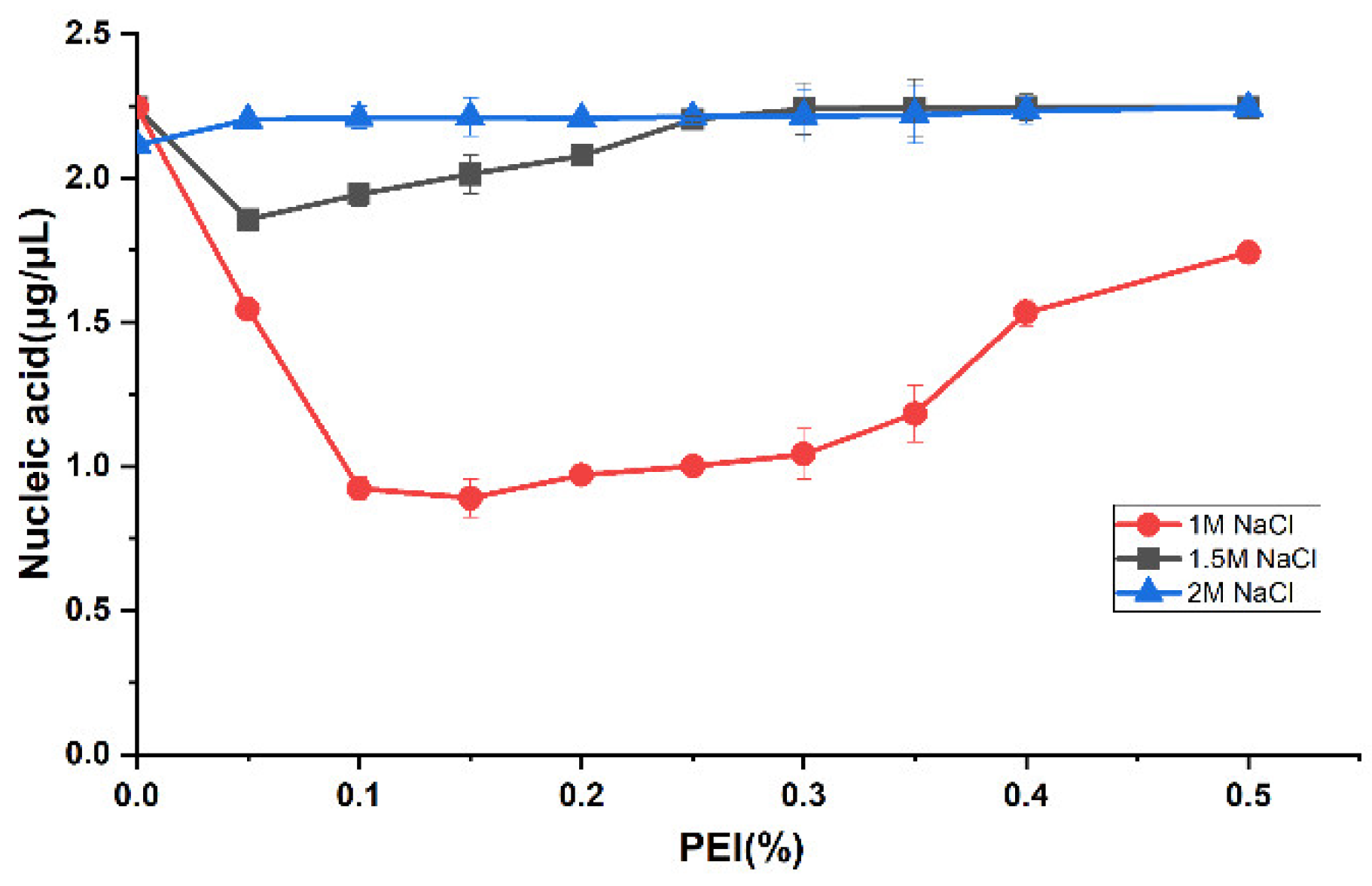

2.4. PEI precipitation of Nucleic Acids

PEI is a linear polymer rich in positive charge, which can form charge-neutralizing precipitation with a large number of negatively charged nucleic acid molecules, thus, removing nucleic acid [

28]. Therefore, the nucleic acid in the N protein sample was removed using the PEI precipitation method. To study the effect of nucleic acid precipitation with different PEI concentrations under different salt concentrations, we selected NaCl concentration gradients of 1, 1.5, and 2 M. As the full-length N protein demonstrates the LLPS phenomenon during the initial cell fragmentation step at low salt concentration, the PEI binding to nucleic acid experiment at low salt concentration was not performed. The PEI concentration of each sample under three NaCl concentrations is 0.05%, 0.1%, 0.15%, 0.2%, 0.25%, 0.3%, 0.35%, 0.4%, and 0.5% respectively. The nucleic acid content in the supernatants of each sample after PEI precipitation was determined. As shown in the

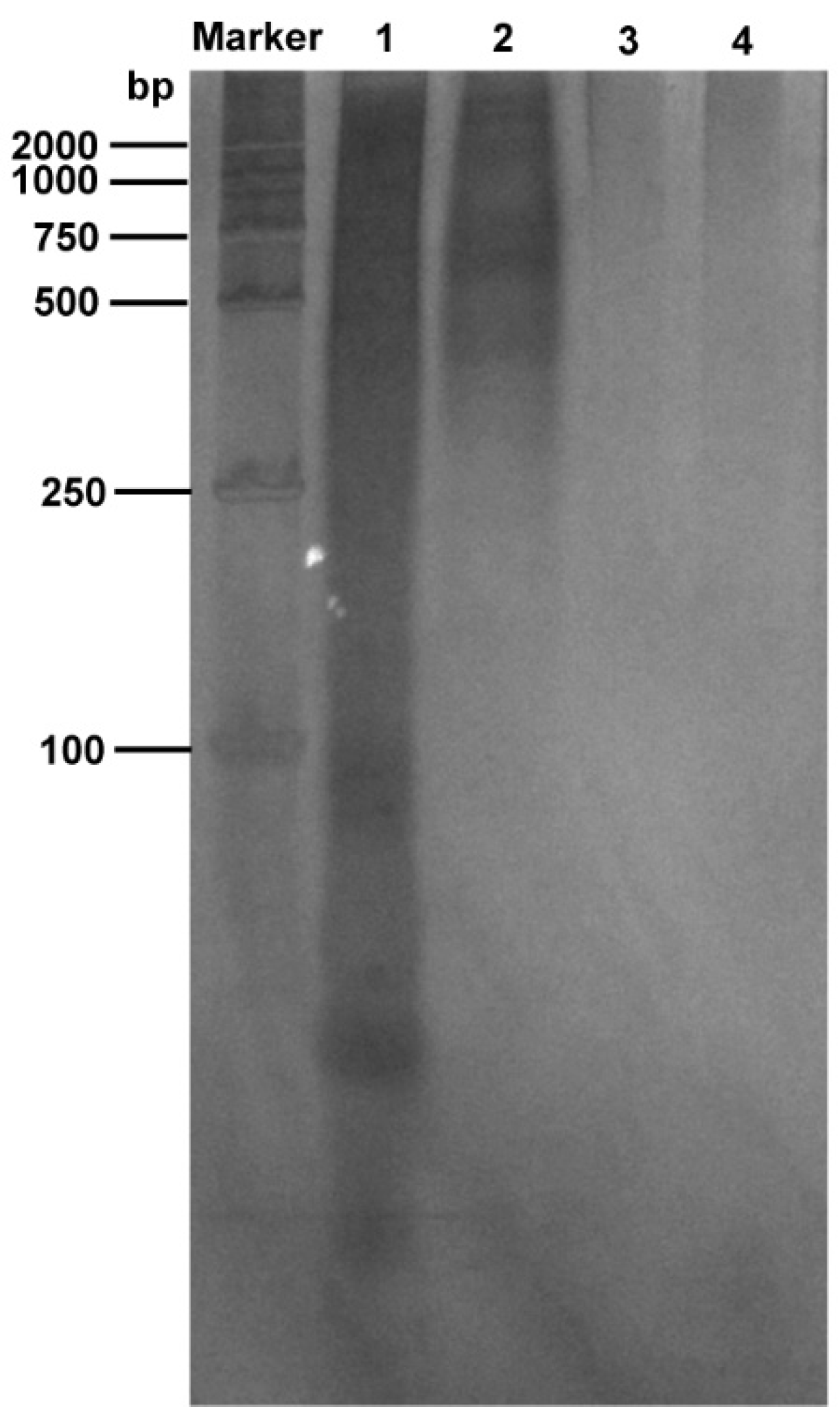

Figure 2, with 1M NaCl, the nucleic acid residue in the sample gradually decreases with an increase in PEI concentration. A final concentration of 0.15% PEI showed the best nucleic acid precipitation effect as the nucleic acid residue in the sample was the lowest. Furthermore, silver staining experiments showed that PEI removed most of the nucleic acids in the samples (

Figure 3, lane 2). Thereafter, an increase in PEI concentration significantly decreased the nucleic acid precipitation. However, under 1.5 and 2 M NaCl conditions, no visible effect of PEI was observed on nucleic acid precipitation (

Figure 2), indicating that the effect of PEI on nucleic acid precipitation decreased with an increase in salt concentration. This is primarily because the interaction between PEI and negatively charged molecules is affected by pH and salt concentration. The increase in salt concentration weakened the binding between PEI and the interacting molecules. Therefore, we selected 0.15% PEI under 1 M NaCl to remove most of the nucleic acids in the protein sample. The residual nucleic acid was removed with the subsequent purification step.

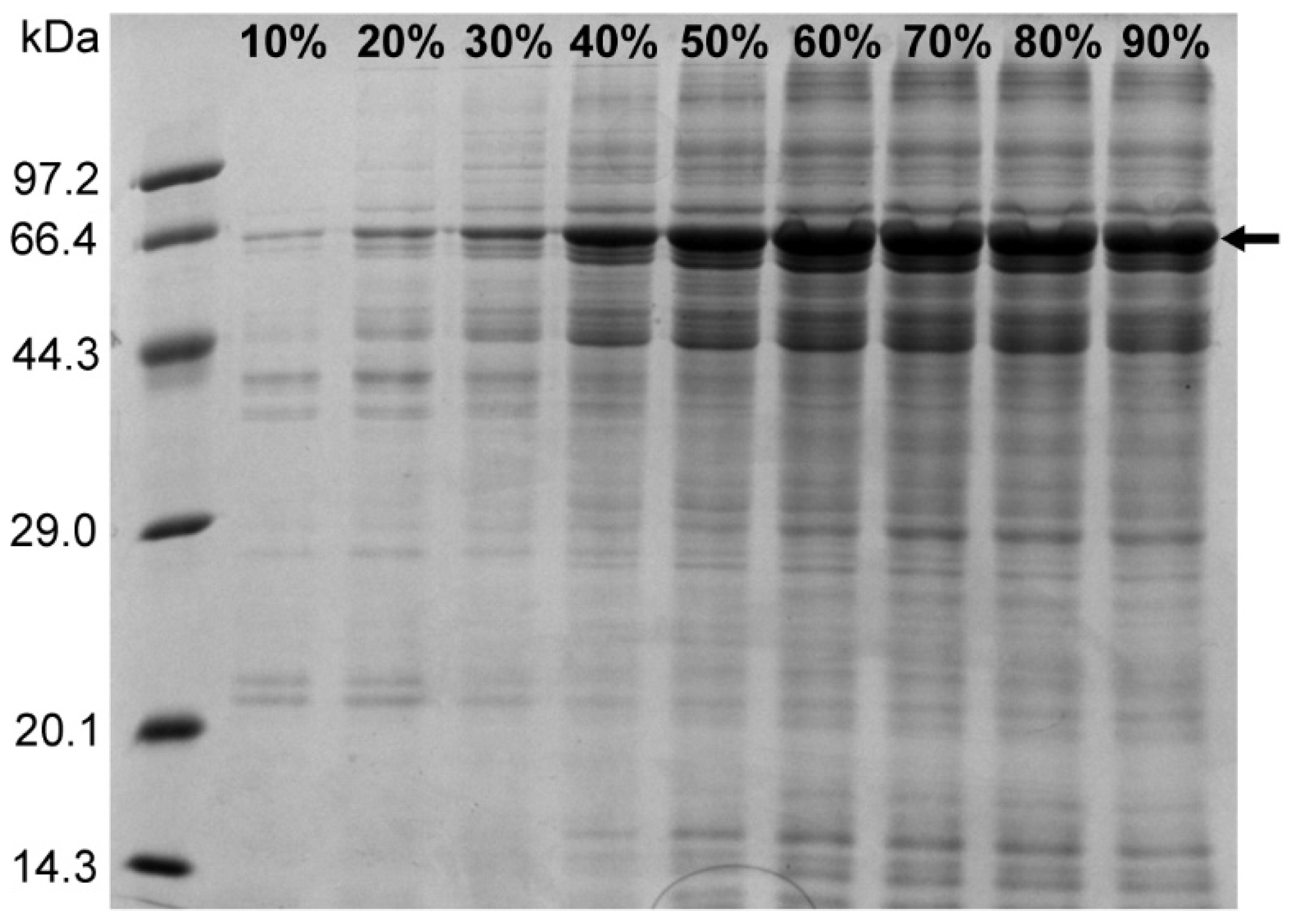

2.5. Ammonium Sulfate Precipitation

The ammonium sulfate precipitation method can not only enrich the sample protein but also have a certain purification effect by reducing the nucleic acid in the precipitated protein. In addition, there may be free PEI molecules in the sample treated with PEI, which can interfere with the subsequent purification step with the nickel column. Thus, the ammonium sulfate precipitation step removes the free PEI molecules that are retained in the supernatant after centrifugation. To study the relationship between the concentration of ammonium sulfate and the precipitation effect of the target protein, saturated ammonium sulfate solution was added to the sample containing 1 M NaCl after PEI treatment so that the concentration of ammonium sulfate was 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50%, 70%, 80%, and 90%, respectively. The sample was centrifuged at 4°C for 2 h, and the protein precipitate was resuspended in buffer C (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 M NaCl, pH 8.0), followed by SDS-PAGE analysis. The results showed that the amount of N protein precipitated by ammonium sulfate increased with increasing ammonium sulfate concentration under 1 M NaCl concentration (

Figure 4). At 60% ammonium sulfate concentration, the precipitation of N protein did not significantly increase as no visible difference was observed on the gel map. Therefore, we selected 60% ammonium sulfate to enrich the target protein while removing the residual nucleic acid and PEI.

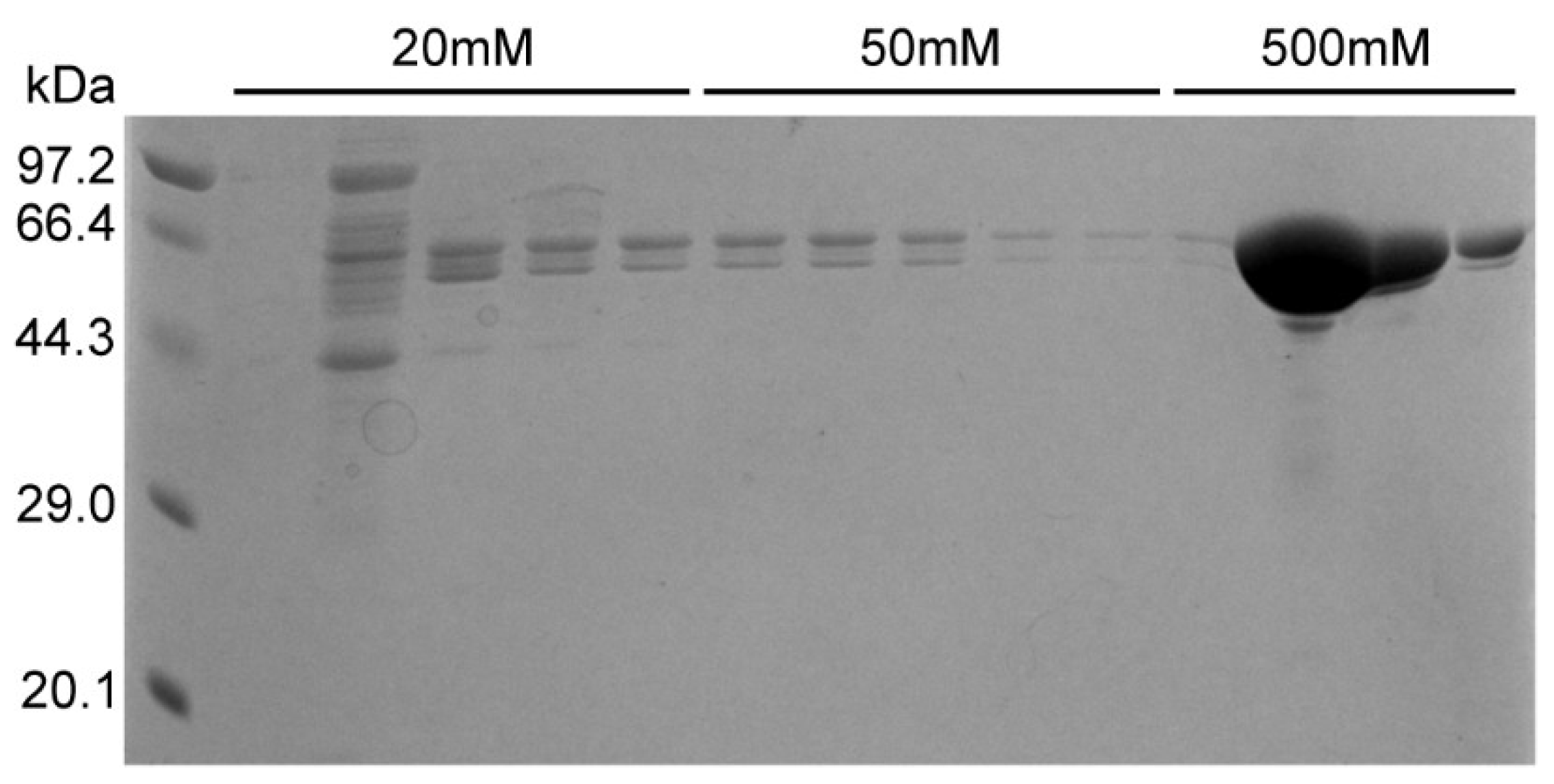

2.6. Purification of Nucleocapsid Protein Using Nickel Column

Following treatment with ammonium sulfate, traces of free PEI may still remain; therefore, the sample was dialyzed and then passed through a nickel column to obtain the pure N protein. After washing with 20 and 50 mm imidazole, the pure N protein was obtained at the concentration of 1 M imidazole (

Figure 5). Simultaneously, the purified samples were tested with silver staining. The results indicated that pure N protein without nucleic acid contamination can be obtained after performing the abovementioned purification steps (

Figure 3, lane 3). In addition, we also tried to purify N protein directly by nickel column after crushing and centrifugation under the condition of buffer C (without PEI and ammonium sulfate treatment). Although the N protein was also obtained, the N protein precipitated in the later dialysis step because the obtained N protein contained nucleic acid (

Figure S1A). However, the N protein treated with PEI and ammonium sulfate did not precipitate (

Figure S1B).

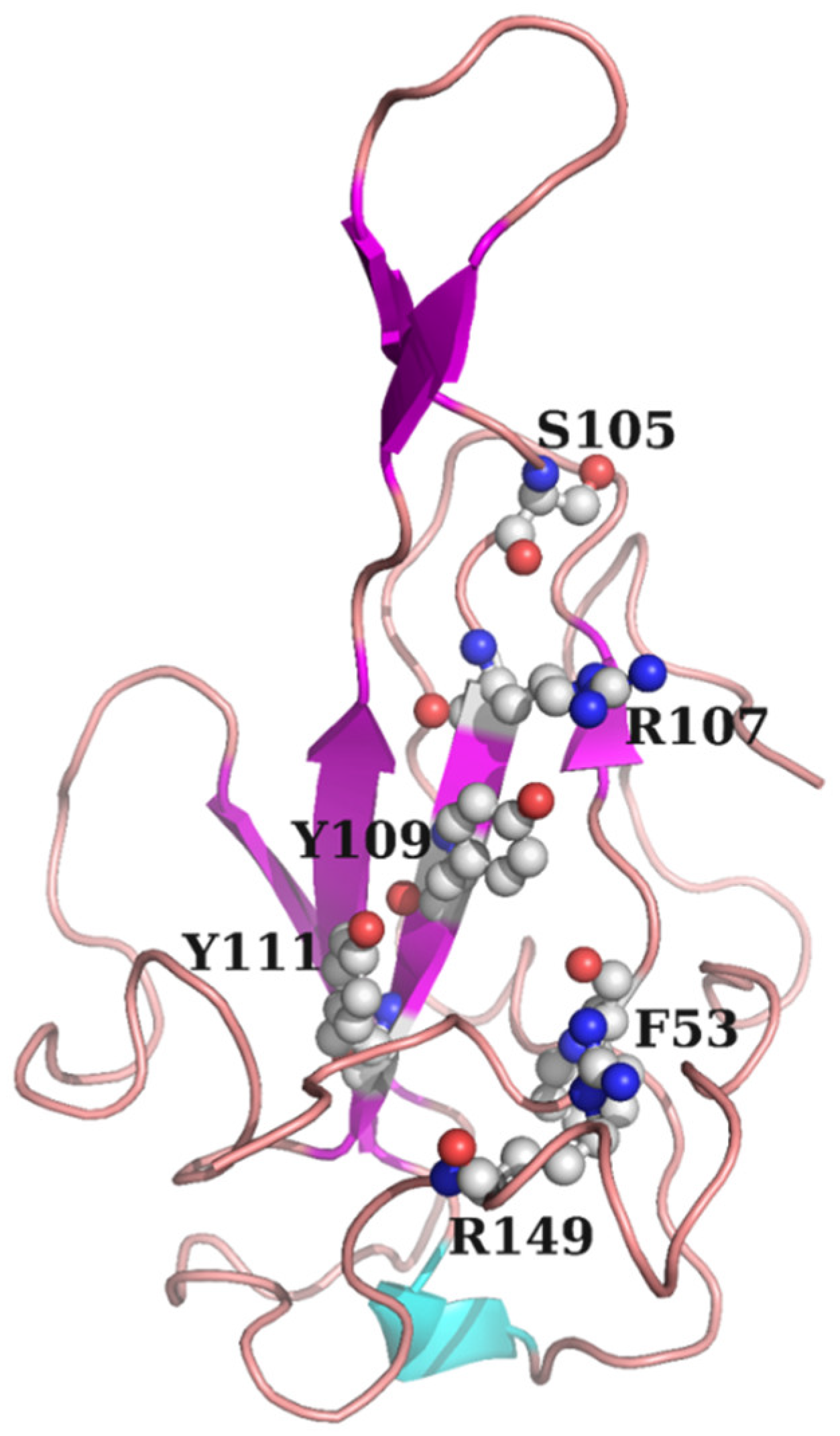

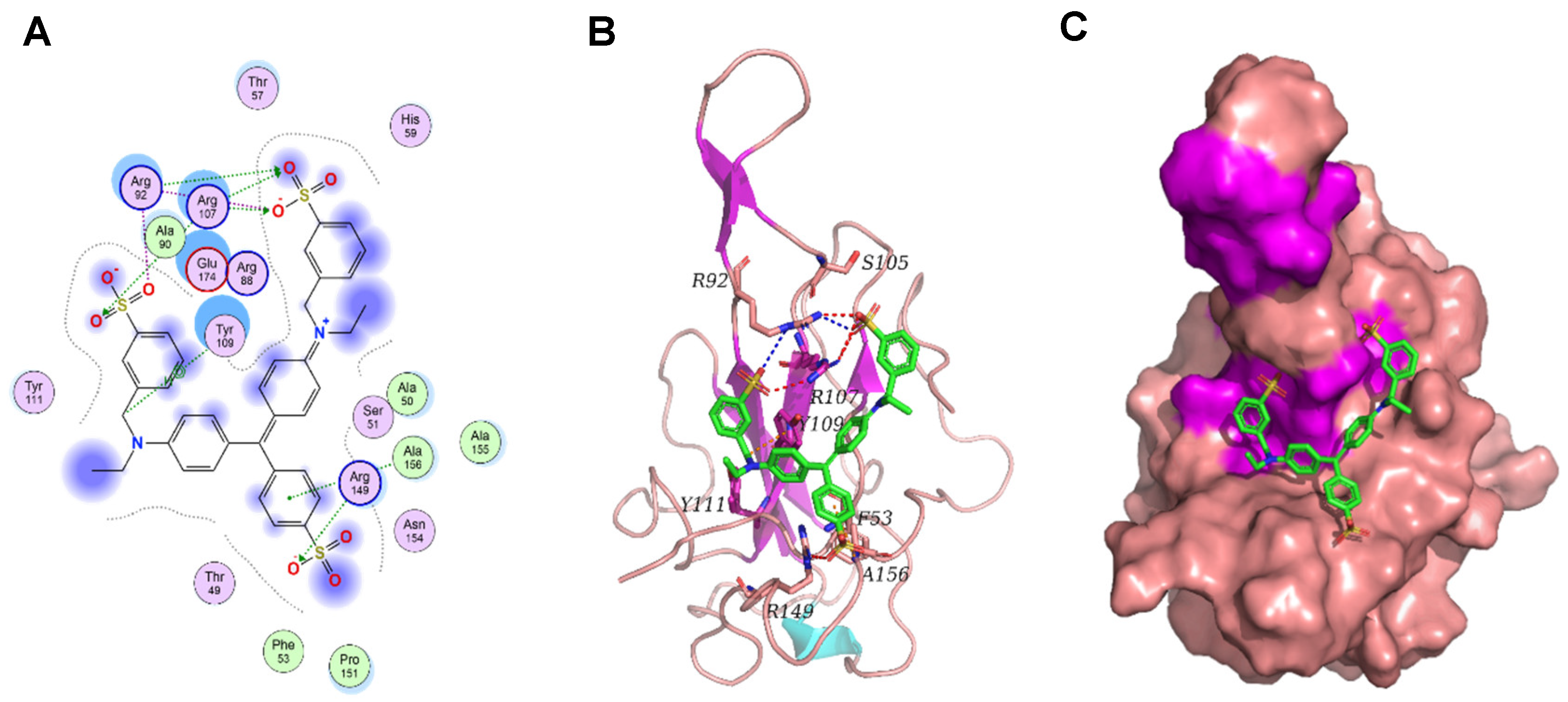

2.7. Screening of Inhibitors Targeting N Protein

N protein is crucial for SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis, vaccine production, and drug development [

13,

15,

19]. Our main research goal is the development of novel coronavirus drugs. Therefore, using the NTD of N protein of SARS-CoV-2 as the receptor protein, SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors were screened from 6,000 natural products and their derivatives as well as 2,800 approved drug molecules by computer-aided drug molecular design platform MOE. The molecule docking pocket of N protein is shown in

Figure 6. The structure and docking score of the top 20 natural products and their derivatives are shown in

Figure S2, and the top 20 approved drug molecules are shown in

Figure S3. The affinity between these potential small molecule inhibitors and N proteins was determined using the BLI technique.

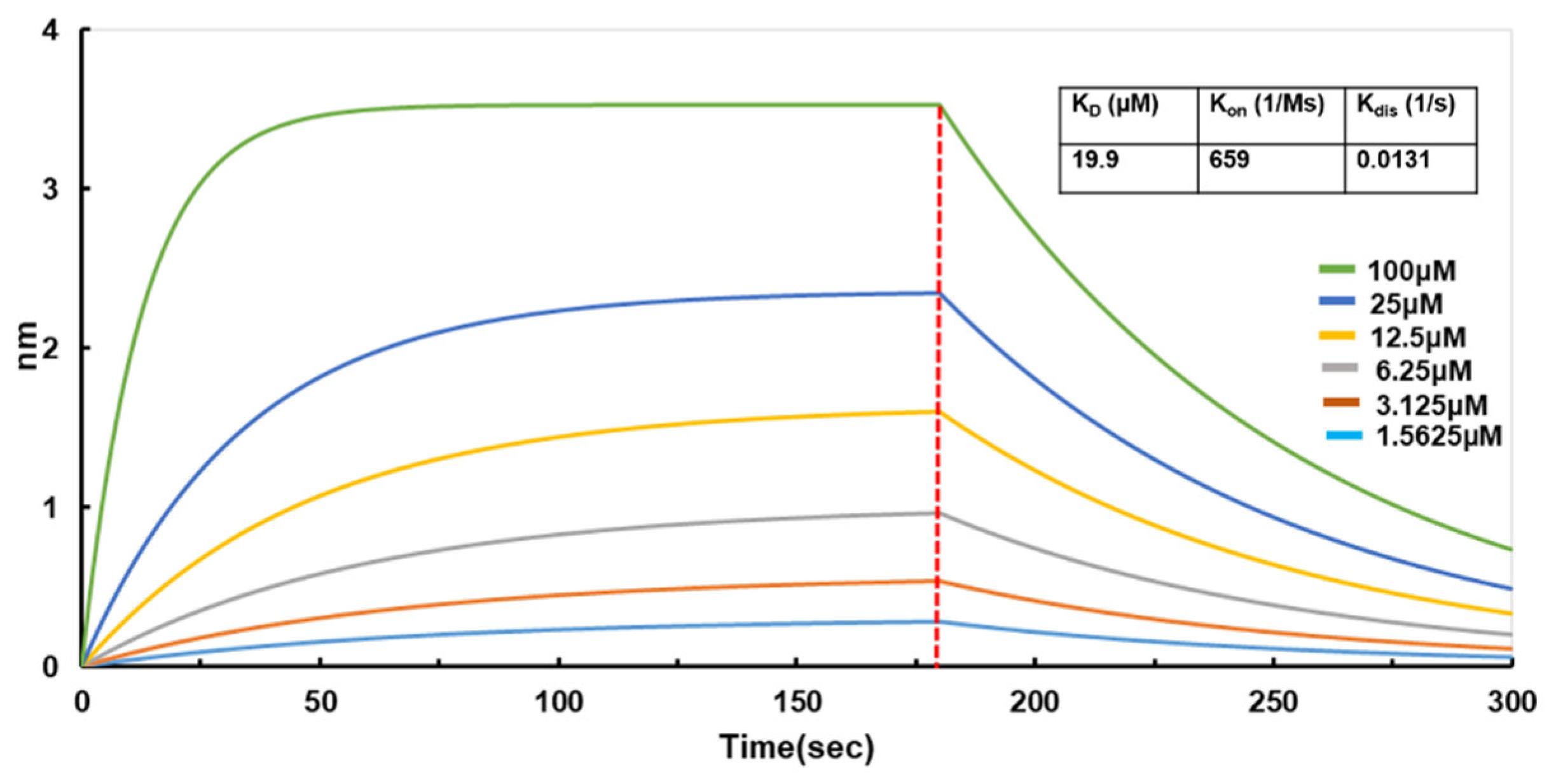

2.8. Analysis of the Interaction Between N Protein and Small Molecule Inhibitor Brilliant Green and Light Yellow

BLI is an unmarked, real-time optical detection technology, primarily used for omnidirectional quantitative analysis of biomolecule interactions. BLI can monitor the whole intermolecular binding process in real-time and calculate crucial data, such as intermolecular affinity (K

D), binding rate (K

on), and dissociation rate (K

dis). Several reports have successfully demonstrated the interactions between notable proteins and small molecules using BLI technology [

33,

34,

35]. Therefore, we used BLI technology to determine the affinity between the purified full-length N protein and small molecules. So far, we have screened small molecules, and Light Green SF has a good affinity for N protein (

Figure 7), suggesting a potential good inhibitor for N protein. Furthermore, the binding between Light Green SF and N protein was studied using molecular docking. The binding mode between Light Green SF and N protein is depicted in Figure. Within the binding pocket, the two oxygen atoms on the sulfate radical of Light Green SF form salt bridges with the two nitrogen atoms of Arg92; the four oxygen atoms on the three sulfate radicals of Light Green SF, regarded as hydrogen bond acceptors, form three hydrogen bonds with the nitrogen atom of Arg92, Arg107, and Arg149, respectively. The carbon atom of Light Green SF forms an H–π conjugate with the benzene ring of Tyr109; the benzene ring of Light Green SF forms an H–π conjugate with the nitrogen atom of Ala156. In short, we have screened the small molecule Light Green SF that can act on the N protein nucleic acid binding domain, and more experiments will be carried out to determine that the Light Green SF plays an inhibitory role in the life cycle of SARS-CoV-2.

3. Discussion

This study focused on the purification and inhibitor screening of the full-length N protein. We succeeded in developing the full-length N protein without nucleic acid contamination using a set of purification processes. First, the prokaryotic expression system was utilized to achieve high expression of soluble N protein. Cell fragmentation causes N proteins to aggregate due to the occurrence of LLPS phenomenon under low salt concentrations. This was significantly prevented by increasing the salt concentration to 1 M NaCl. In addition, the occurrence of LLPS is closely related to the content of nucleic acid and N protein in the system. As the expression of N protein was high, it was necessary to adjust the suspension volume of bacterial weight. Second, the nucleic acid was precipitated by the nucleic acid binding characteristics of PEI. It was observed that the precipitation effect of nucleic acid is the best at 0.15% PEI with 1 M NaCl. At 1.5M NaCl, the nucleic acid binding ability of PEI significantly decreased, and with 2 M NaCl, PEI lost its nucleic acid binding ability. The main reason for this observation was that the nucleic acid binding ability of PEI is affected by pH and salt concentration. Increasing salt concentration will weaken the binding of PEI to nucleic acid. Then, the sample was precipitated with ammonium sulfate. This step not only enriches the sample to facilitate subsequent purification but also removes free PEI, which can interfere with the protein purification step. Finally, the full-length N protein was purified using the conventional nickel column.

Next, we screened the inhibitors for N proteins. A classical method of drug screening is the combination of virtual screening and biological experimental verification. In this study, computer-aided drug molecular design platform MOE was used to screen SARS-CoV-2 inhibitors. The potential small molecular inhibitors were screened and identified by measuring the affinity of full-length N proteins with small molecular drugs using the BLI technique. The results showed that Light Green SF had a better binding ability to N protein and could potentially serve as a novel coronavirus inhibitor. In any case, the results of this study will provide a simple and convenient sample purification method for related research based on full-length nucleocapsid proteins and solve the problem of nucleic acid contamination of full-length nucleocapsid protein samples. At the same time, the library of potential drugs against SARS-CoV-2 has also been expanded.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Prokaryotic Expression of Nucleocapsid Protein

The expression vector of N protein (GenBank: UBE86422.1) was constructed via gene synthesis. To promote the soluble expression of N protein, small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) was fused at the amino terminal of the N protein. To express SUMO and N proteins in pET28a plasmid vector, the complementary DNAs of both proteins and the pET28a vector were digested with the upstream and downstream restriction enzymes NcoI and XhoI, respectively. This was followed by ligation to construct the recombinant pET28a-SUMO-N expression vector. The pET28a-SUMO-N expression vector was transformed into E. coli competent cells BL21 (DE3) and the transformants were selected into 5 mL liquid Luria Bertani (LB) medium containing 50 µg/mL kanamycin and incubated overnight at 37°C in a shaker incubator at 220 rpm. Subsequently, 1 mL of the culture was added to 1L LB medium containing 50 µg/mL kanamycin under continuous shaking at 220 rpm at 37 °C. When OD600 was 1.0, IPTG (5 mM) was added to induce the expression of N protein at 20°C for 16 h at 220 rpm. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 6,000 rpm for 10 min.

4.2. Purification of Nucleocapsid Protein

4.2.1. Ultrasonic Fragmentation of Bacteria

One part of the collected bacteria was resuspended in buffer A (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1M NaCl, 10% Glycerol, DNase I, RNase A, 1 mM DTT, pH 8.0) as the control, the other part was resuspended in buffer B (50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.3M NaCl, 10% Glycerol, DNase I, RNase A, 1 mM DTT, pH 8.0) for ultrasonic fragmentation of bacteria.

4.2.2. PEI Precipitated Nucleic Acid

To study the effect of nucleic acid precipitation with different PEI concentrations under different salt concentrations, buffer C (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 M NaCl, pH 8.0), buffer D (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1.5 M NaCl, pH 8.0), and buffer E (50 mM Tris-HCl, 2 M NaCl, pH 8.0) were prepared. A 5% PEI solution was prepared with each of the above three buffers, and the final pH was adjusted to 8.0. At the same time, the bacterial specimens obtained from the aforementioned three solutions were resuspended. The NaCl concentration in the lytic solution was set at 1 M, 1.5 M, and 2 M, respectively. Subsequently, the supernatants from the three distinct cell lysis fluids, each featuring different NaCl concentrations, were evenly divided into an equivalent number of samples.

To each sample, 5% polyethyleneimine (PEI) was introduced, yielding PEI concentrations corresponding to the respective NaCl concentrations as follows: 0.05%, 0.1%, 0.15%, 0.2%, 0.25%, 0.3%, 0.4%, and 0.5%. Finally, the sample volumes were adjusted to match those of a buffer solution containing the corresponding NaCl concentration. The resultant mixtures were then incubated at 4°C for a duration of 30 min, followed by centrifugation at 15000 rpm for 10 min. Subsequent determination of nucleic acid content was conducted using the Nano-100 instrument (Allsheng).

4.2.3. Ammonium Sulfate Precipitation

Saturated ammonium sulfate solution was prepared with buffers C, D, and E, respectively. We took a number of the same broken liquid samples and adjusted the NaCl concentration to 1, 1.5 and 2 M, respectively, followed by the addition of saturated ammonium sulfate solution with the corresponding NaCl concentration so that the ammonium sulfate concentration gradients in the samples containing different NaCl concentrations are 10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, and 90%. Finally, the sample volume was adjusted to the same volume by adding the buffer containing the corresponding NaCl concentration. The samples were allowed to incubate at 4°C for 2 h, followed by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 30 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the protein precipitates were resuspended in buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1M NaCl, pH 8.0) and SDS-PAGE was performed to analyze the effect of ammonium sulfate on the precipitation of N protein at different concentrations.

4.2.4. Purification of N Protein Using Nickel Column

The samples without PEI and ammonium sulfate were used as controls and directly purified using the nickel column, whereas the samples treated with PEI and ammonium sulfate were dialyzed to remove PEI and ammonium sulfate. The dialysis bag size was 35,000 D, and the dialysate composition was 50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 M NaCl, 5 mM Imidazole, pH 8.0. The protein sample was added to the nickel column, and 20 mM and 50 mM Imidazole buffer were used to remove the impure proteins. Finally, the N protein was eluted with the buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 M NaCl, 500 mM Imidazole, pH 8.0. The purity of the protein was assessed with SDS-PAGE.

4.3. Silver Staining Experiment

An appropriate amount of sample was collected from each of the above steps and reserved for the analysis of nucleic acid residues. The rapid nucleic acid silver staining kit was purchased from Coolaber. A 12% nucleic acid PAGE glue was prepared with the following ingredients: H20 (7.9 mL), 30% acrylamide (4 mL), 5× tris borate EDTA buffer (3 mL), 10% ammonium persulfate (0.11 mL), and tetramethylethylenediamine (0.01 mL). The sample (9 µL) was mixed with 1 µL 10× loading buffer, and nucleic acid PAGE was performed for 1 h at 120 V and 250 mA.

Following PAGE, the PAGE glue was transferred to a glass Petri dish containing deionized water and rinsed for 2 min each time, a total of 3 times. And then the PAGE glue was transferred to an appropriate volume of fixing liquid (10% ethanol and 1% nitric acid) so that the PAGE glue was immersed during gentle shaking at 40–60rpm for 10 min. Thereafter, the fixing solution was discarded, and the PAGE glue was quickly rinsed thrice with deionized water for 30 s each. The PAGE glue was transferred to an appropriate volume of dyeing solution (0.2% silver nitrate) to immerse the PAGE glue during gentle shaking for 5 min at room temperature. The dye solution was quickly rinsed thrice with deionized water for 30 s each. Finally, the PAGE glue was transferred to an appropriate volume of chromogenic solution (3% Na2CO3, 60 µL formaldehyde, and 10 mg Na2SO4), and 600 mL deionized H20 was added until the DNA marker or positive control band was clearly visible, and the PAGE glue was photographed using a gel imager (Bio-Rad).

4.4. SDS-PAGE

During all sample treatments, an appropriate amount of sample was retained for SDS-PAGE analysis. A 12% SDS-PAGE gel was used and run for 2 h at 120 V and 250 mA. After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, followed by decolorization with glacial acetic acid and ethanol, and finally photographed and analyzed using a gel imager (BIO-RED).

4.5. Virtual Screening

The docking module in MOE1 was used for structure-based visual screening (SBVS). Approximately 6000 natural products and their derivatives and 2800 approved drug molecules were selected as visual screening library. All compounds were prepared with the Wash module in MOE. The structure of protein 2019-nCoV nucleocapsid NTD is selected as receptor, and the PDB ID is 7CDZ The molecule binding site in the receptor was selected around the residues F53, S105, R107, Y109, Y111, and R149. Subsequently, all compounds were ranked by flexible docking with the “induced fit” protocol. Prior to docking, the force field of AMBER10:EHT and the implicit solvation model of the Reaction Field (R-field) were selected. The protonation state of the protein and the orientation of the hydrogens were optimized using QuickPrep module at pH 7 and a temperature of 300 K. For flexible docking, initially, the docked poses were ranked by London dG scoring, then a force field refinement was performed on the top 10 poses followed by a rescoring of GBVI/WSA dG, and the best-ranked pose was retained. After docking, the compounds were clustered structurally through the Fingerprint Cluster module in MOE. The best-ranked 1000 molecules were finally identified as potential hits.

4.6. BLI Analysis

BLI experiments were performed using Octet-RED96e (Santorius). Experiments were performed in an assay buffer containing 50 mM PBS pH 7.5, 1 M NaCl, and 0.2% (v/v) Tween. Samples were added to a 96-well plate containing 200 µL per well. For each experiment, we used anti-His tagged biosensors (HIS1K, Santorius), which were loaded with N protein ligands and then immersed in different concentrations of inhibitor analytes. The ligand concentration for loading was 1 mg/mL (His marker). All experiments were accompanied by reference measurements, using unloaded HIS1K tips immersed in wells with the same analyte. Experiments with different analyte concentrations also included zero analyte reference. Octet software version 10 (Santorius) was used to process and fit the data.

5. Conclusion

Although the global pandemic exhibits an overall declining trend, and the pressure on global health systems has eased, SARS-CoV-2 continues to mutate, leading to localized outbreaks in some countries and regions. Consequently, the research and development of vaccines and therapeutic drugs against SARS-CoV-2 remain ongoing and highly necessary worldwide. The N protein, the most abundant protein in the virion [

36,

37], is a determinant of SARS-CoV-2 virulence and pathogenesis [

38]. It is recognized as a highly immunogenic antigen and a potential vaccine and drug target for SARS-CoV-2 [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. One of the critical steps in drug development targeting the N protein is the acquisition of pure N protein.

To date, several papers have been published describing the structure, function, and molecular characteristics of the N protein. However, we have found that N protein samples obtained using previously described purification methods may be heavily contaminated with nucleic acids from the recombinant expression host organism [

44,

45,

46,

47]. The N protein have structures that bind nucleic acids, making it challenging to completely eliminate nucleic acid impurities. In this study, we attempted to develop an effective purification method capable of removing all nucleic acids bound to the N protein. Initially, during N protein purification, we introduced a nucleic acid removal step utilizing PEI, which, under certain conditions, has the property of binding and precipitating nucleic acids, thereby removing most of the nucleic acids. Residual nucleic acid fragments in the protein samples were further removed through subsequent ammonium sulfate precipitation and nickel column purification, ultimately yielding full-length nucleocapsid protein free of nucleic acid contamination.

Due to the difficulty in obtaining full-length nucleocapsid protein without nucleic acid contamination, most researchers often only express a certain domain of the nucleocapsid protein when developing inhibitors against it. This may result in the selected inhibitors not being the most effective, as there are structural differences between the partial and full-length nucleocapsid proteins targeted, and there are often interactions among domains. Therefore, the full-length nucleocapsid protein is more suitable as a drug development target. Next, we screened for inhibitor drugs against the obtained full-length nucleocapsid protein, combining virtual screening with biological experiments, and ultimately identified a potential inhibitor, Light Green SF. Unfortunately, due to experimental conditions, relevant experiments on the inhibitor Light Green SF in SARS-CoV-2 have not yet been conducted. We will complete this part in the future to further elucidate the specific mechanism of action and effectiveness of Light Green SF in SARS-CoV-2.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

C.C. wrote the original draft. C.C., Z.Z., Q.Z. curated laboratory data. C.C., Z.Z., Q.Z. performed the investigation. S.Z. and Y.Z. administered the project and acquired funding. All authors read and approved the fnal manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan (2020YJ0158), the Sichuan Province Science and Technology project (25NSFSC0880), the Joint Project of Luzhou Science and Technology Bureau and Southwest Medical University (2024LZXNYDT003), the Natural Science Foundation of Southwest Medical University (2019ZQN168) and the College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program (S202210632091 and S202210632244).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, J.; Lai, S.; Gao, G.F.; Shi, W. The emergence, genomic diversity and global spread of SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2021, 600, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Male, V. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. Nat Rev Immunol 2022, 22, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekely, J.; Mongkolprasert, J.; Jeayodae, N.; Senorit, C.; Chaimuti, P.; Swangphon, P.; Nanakorn, N.; Nualnoi, T.; Wongwitwichot, P.; Pengsakul, T. Development, Analytical, and Clinical Evaluation of Rapid Immunochromatographic Antigen Test for SARS-CoV-2 Variants Detection. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telenti, A.; Arvin, A.; Corey, L.; Corti, D.; Diamond, M.S.; García-Sastre, A.; Garry, R.F.; Holmes, E.C.; Pang, P.S.; Virgin, H.W. After the pandemic: perspectives on the future trajectory of COVID-19. Nature 2021, 596, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shaba, R.M.; Nayel, M.A.; Taher, M.M.; Abdelmonem, R.; Shoueir, K.R.; Kenawy, E.R. Three waves changes, new variant strains, and vaccination effect against COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Biol Macromol 2022, 204, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahumud, R.A.; Ali, M.A.; Kundu, S.; Rahman, M.A.; Kamara, J.K.; Renzaho, A.M.N. Effectiveness of COVID-19 Vaccines against Delta Variant (B.1.617.2): A Meta-Analysis. Vaccines 2022, 10, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pormohammad, A.; Zarei, M.; Ghorbani, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Aghayari Sheikh Neshin, S.; Khatami, A.; Turner, D.L.; Djalalinia, S.; Mousavi, S.A.; Mardani-Fard, H.A.; et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 Vaccines against Delta (B.1.617.2) Variant: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Studies. Vaccines 2022, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, G.; Li, D.; Lin, Y.; Fu, Z.; Qi, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Si, S.; Chen, Y. Development of a simple and miniaturized sandwich-like fluorescence polarization assay for rapid screening of SARS-CoV-2 main protease inhibitors. Cell Biosci 2021, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabelli, A.M.; Peacock, T.P.; Thorne, L.G.; Harvey, W.T.; Hughes, J.; de Silva, T.I.; Peacock, S.J.; Barclay, W.S.; de Silva, T.I.; Towers, G.J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: immune escape, transmission and fitness. Nat Rev Microbiol 2023, 21, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, W.T.; Carabelli, A.M.; Jackson, B.; Gupta, R.K.; Thomson, E.C.; Harrison, E.M.; Ludden, C.; Reeve, R.; Rambaut, A.; COVID-19 Genomics UK (COG-UK) Consortium; et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, spike mutations and immune escape. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 409–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, K.; Girl, P.; Giebl, A.; Gruetzner, S.; Antwerpen, M.; Khatamzas, E.; Wölfel, R.; von Buttlar, H. Sensitivity of two SARS-CoV-2 variants with spike protein mutations to neutralising antibodies. Virus Genes 2021, 57, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Schmidt, F.; Weisblum, Y.; Muecksch, F.; Barnes, C.O.; Finkin, S.; Schaefer-Babajew, D.; Cipolla, M.; Gaebler, C.; Lieberman, J.A.; et al. mRNA vaccine-elicited antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and circulating variants. Nature 2021, 592, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Du, N.; Lei, Y.; Dorje, S.; Qi, J.; Luo, T.; Gao, G.F.; Song, H. Structures of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid and their perspectives for drug design. EMBO J 2020, 39, e105938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Ye, Q.; Singh, D.; Cao, Y.; Diedrich, J.K.; Yates, J.R.; Villa, E.; Cleveland, D.W.; Corbett, K.D. The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid phosphoprotein forms mutually exclusive condensates with RNA and the membrane-associated M protein. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Cheng, Y.; Zhou, H.; Sun, C.; Zhang, S. The SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein: its role in the viral life cycle, structure and functions, and use as a potential target in the development of vaccines and diagnostics. Virol J 2023, 20, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V’kovski, P.; Kratzel, A.; Steiner, S.; Stalder, H.; Thiel, V. Coronavirus biology and replication: implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggen, J.; Vanstreels, E.; Jansen, S.; Daelemans, D. Cellular host factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Microbiol 2021, 6, 1219–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emrani, J.; Ahmed, M.; Jeffers-Francis, L.; Teleha, J.C.; Mowa, N.; Newman, R.H.; Thomas, M.D. SARS-COV-2, infection, transmission, transcription, translation, proteins, and treatment: A review. Int J Biol Macromol 2021, 193, 1249–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Cao, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, J. The SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and Its Role in Viral Structure, Biological Functions, and a Potential Target for Drug or Vaccine Mitigation. Viruses 2021, 13, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, J.; Yu, X.; Lan, H.Y. Signaling mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid protein in viral infection, cell death and inflammation. International journal of biological sciences 2022, 18, 4704–4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supekar, N.T.; Shajahan, A.; Gleinich, A.S.; Rouhani, D.S.; Heiss, C.; Chapla, D.G.; Moremen, K.W.; Azadi, P. Variable posttranslational modifications of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 nucleocapsid protein. Glycobiology 2021, 31, 1080–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forsythe, H.M.; Galvan, J.R.; Yu, Z.; Pinckney, S.; Reardon, P.; Cooley, R.B.; Zhu, P.; Rolland, A.D.; Prell, J.S.; Barbar, E. Multivalent binding of the partially disordered SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid phosphoprotein dimer to RNA. Biophysical Journal 2021, 120, 2890–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jack, A.; Ferro, L.; Trnka, M.; Wehri, E.; Nadgir, A.; Nguyenla, X.; Fox, D.; Costa, K.; Stanley, S.; Schaletzky, J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein forms condensates with viral genomic RNA. PLoS Biol 2021, 19, e3001425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarczewska, A.; Kolonko-Adamska, M.; Zarębski, M.; Dobrucki, J.; Ożyhar, A.; Greb-Markiewicz, B. The method utilized to purify the SARS-CoV-2 N protein can affect its molecular properties. Int J Biol Macromol 2021, 188, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuo, T. Viewing SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein in Terms of Molecular Flexibility. Biology 2021, 10, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Ge, Y.; Yuan, E.; Xiong, Y.; Wu, S.; Li, S.; Wu, N.; et al. Understanding the phase separation characteristics of nucleocapsid protein provides a new therapeutic opportunity against SARS-CoV-2. Protein Cell 2021, 12, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Yu, Y.; Sun, L.-M.; Xing, J.-Q.; Li, T.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, M.; Yu, Y.; Xue, W.; Xia, T.; et al. GCG inhibits SARS-CoV-2 replication by disrupting the liquid phase condensation of its nucleocapsid protein. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, R. Protein precipitation techniques. Methods in Enzymology 2009, 463, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duellman, S.J.; Burgess, R.R. Large-scale Epstein–Barr virus EBNA1 protein purification. Protein Expr Purif 2009, 63, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Li, F.Q.; Li, Q.; Hu, H.L.; Hong, G.F. Expression and purification of Rhizobium leguminosarum NodD. Protein Expr Purif 2002, 26, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, B.A.; Gillies, A.R.; Ghazi, I.; LeRoy, G.; Lee, K.C.; Westblade, L.F.; Wood, D.W. Purification of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase using a self-cleaving elastin-like polypeptide tag. Protein Sci 2010, 19, 1243–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Li, W.; Fang, X.; Song, X.; Teng, S.; Ren, Z.; Hu, D.; Zhou, S.; Wu, G.; Li, K. Expression and purification of recombinant SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein in inclusion bodies and its application in serological detection. Protein Expr Purif 2021, 186, 105908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrow, A.; Zuniga, B.; Topo, E.; Cho, J.H. Suppressing Nonspecific Binding in Biolayer Interferometry Experiments for Weak Ligand-Analyte Interactions. ACS omega 2022, 7, 9206–9211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murali, S.; Rustandi, R.R.; Zheng, X.; Payne, A.; Shang, L. Applications of Surface Plasmon Resonance and Biolayer Interferometry for Virus-Ligand Binding. Viruses 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.; Guo, W.; Shen, Q.; Han, J.; Lei, L.; Chen, L.; Yang, L.; Feng, C.; Zhou, B. In vitro biolayer interferometry analysis of acetylcholinesterase as a potential target of aryl-organophosphorus flame-retardants. Journal of hazardous materials 2021, 409, 124999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifoni, A.; Sidney, J.; Zhang, Y.; Scheuermann, R.H.; Peters, B.; Sette, A. A Sequence Homology and Bioinformatic Approach Can Predict Candidate Targets for Immune Responses to SARS-CoV-2. Cell host & microbe 2020, 27, 671–680.e672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Yang, M.; Hong, Z.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Z.; Chen, X.; He, S.; Zhou, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, Q.; et al. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein RNA binding domain reveals potential unique drug targeting sites. Acta pharmaceutica Sinica. B 2020, 10, 1228–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasui, F.; Kai, C.; Kitabatake, M.; Inoue, S.; Yoneda, M.; Yokochi, S.; Kase, R.; Sekiguchi, S.; Morita, K.; Hishima, T.; et al. Prior immunization with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) nucleocapsid protein causes severe pneumonia in mice infected with SARS-CoV. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md.: 1950) 2008, 181, 6337–6348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakib, A.; Sami, S.A.; Islam, M.A.; Ahmed, S.; Faiz, F.B.; Khanam, B.H.; Marma, K.K.S.; Rahman, M.; Uddin, M.M.N.; Nainu, F.; et al. Epitope-Based Immunoinformatics Approach on Nucleocapsid Protein of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus-2. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Huang, J.R.; Zhang, Y.L.; Zhang, J. SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein intranasal inoculation induces local and systemic T cell responses in mice. Journal of medical virology 2021, 93, 1923–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, M.; Sharma, A.R.; Patra, P.; Ghosh, P.; Sharma, G.; Patra, B.C.; Lee, S.S.; Chakraborty, C. Development of epitope-based peptide vaccine against novel coronavirus 2019 (SARS-COV-2): Immunoinformatics approach. Journal of medical virology 2020, 92, 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwudozie, O.S.; Chukwuanukwu, R.C.; Iroanya, O.O.; Eze, D.M.; Duru, V.C.; Dele-Alimi, T.O.; Kehinde, B.D.; Bankole, T.T.; Obi, P.C.; Okinedo, E.U. Attenuated Subcomponent Vaccine Design Targeting the SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Phosphoprotein RNA Binding Domain: In Silico Analysis. Journal of immunology research 2020, 2020, 2837670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, S.C.; de Magalhães, M.T.Q.; Homan, E.J. Immunoinformatic Analysis of SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and Identification of COVID-19 Vaccine Targets. Frontiers in immunology 2020, 11, 587615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zinzula, L.; Basquin, J.; Bohn, S.; Beck, F.; Klumpe, S.; Pfeifer, G.; Nagy, I.; Bracher, A.; Hartl, F.U.; Baumeister, W. High-resolution structure and biophysical characterization of the nucleocapsid phosphoprotein dimerization domain from the Covid-19 severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2021, 538, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdikari, T.M.; Murthy, A.C.; Ryan, V.H.; Watters, S.; Naik, M.T.; Fawzi, N.L. SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein phase-separates with RNA and with human hnRNPs. The EMBO journal 2020, 39, e106478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, W.; Liu, G.; Ma, H.; Zhao, D.; Yang, Y.; Liu, M.; Mohammed, A.; Zhao, C.; Yang, Y.; Xie, J.; et al. Biochemical characterization of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2020, 527, 618–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; West, A.M.V.; Silletti, S.; Corbett, K.D. Architecture and self-assembly of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein. Protein science: a publication of the Protein Society 2020, 29, 1890–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).