1. Introduction

In recent years, the transition through the HIV care cascade has greatly improved in high- and middle-income countries. These improvements have significantly reduced the time an individual remains infective in the community, which will help reduce HIV incidence in the upcoming years [

1,

2,

3]. Nevertheless, late diagnosis is rising and remains one of the main concerns in achieving effective community viral suppression in high-income countries [

1,

4,

5].

Late HIV diagnosis, which has recently been redefined to better exclude recent infections [

6], is rising all over Europe [

1,

4,

5]. Despite significant efforts to improve HIV testing and reduce late diagnosis, which increases the time that an infected individual is at risk of transmitting the infection, testing remains suboptimal in many settings. Opt-out screening is part of the testing guidelines in many regions with higher prevalence [

7,

8], while others rely on indicator condition-guided HIV testing. However, most of the testing strategies rely on physicians to identify patients who could potentially be at risk of acquiring HIV based on individual risk factors[

9,

10]. Some formative strategies and electronic aids, including training sessions at the hospital and primary care level, have been demonstrated to increase testing rates transiently [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. However, data on the long-term effect of these strategies is lacking.

Nevertheless, the assessment of individual HIV risk presents numerous challenges in real-world clinical settings. Time constraints, complex consent processes, limited professional training, patient reluctance, and competing healthcare priorities are significant barriers to optimal testing and risk assessment [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

To address reduced testing and late diagnosis, our group has been working on improving primary care and hospital physician

s’ HIV and HCV awareness[

11,

12,

20,

21]. In this sense, in the first months of 2017, we performed a two-hour formative session on HIV and Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) guidelines to encourage HIV and HCV screening in primary care centres that are adhered to our health area (Ramón y Cajal Hospital, Madrid)[

12].

In this study, we aimed to describe the long-term evolution of HIV testing rates in our healthcare area before and after the training sessions.

2. Materials and Methods

In 2017, we provided a non-mandatory two-hour training session accredited by the Council of the Community of Madrid in each of the 20 primary care centres in the Ramón y Cajal Hospital area. The session, conducted by infectious diseases specialists, targeted medical doctors and nurses and included four modules: (1) epidemiology of HIV infection, (2) diagnostic strategies, (3) treatment of HIV, and (4) other sexually transmitted infections. After the sessions, we had an hour to review the material and complete questionnaires to estimate the knowledge of HIV testing, the barrier to HIV testing, and the rates of previous offering of HIV tests. We used a self-administered questionnaire developed within the OptTEST project (Project No. 20131102, European Union, Framework of the Health Program 2008–2013)[

22]. The main objective was to promote early diagnosis of HIV infection in the primary care setting by disseminating current HIV testing guidelines; another aim is to improve knowledge of current trends in the prevention, diagnosis, and management of HIV infection among primary care providers[

12].

Study Groups and Outcomes

We compared the yearly absolute number of HIV tests requested in these primary care facilities and calculated the annual rate of HIV testing and the annual rate of HIV-positive tests per 100,000 patients who were assigned to the centres with the intervention.

We defined two periods according to the date the training sessions were carried out: the pre-session period included five years leading up to the training session in 2017 (2012 to the beginning of the training sessions), and the post-session period consisted of five years after the training sessions were completed up to the censoring date (mid-2017 to November 2022).

We then created two groups: the intervention group included all patients assigned to a primary care doctor at the 20 primary care centres with intervention; the control group included all the remaining patients who had been included in the cohort during the study period.

Data Collection

To obtain the number of ordered HIV tests and positive HIV tests, we used the electronic records of the Microbiology Department of Ramón y Cajal Hospital, which processes all requested HIV tests of the intervened primary care centres. We included al the tests that were ordered starting 01/01/2012 until 31/12/2022. Data was accessed on 13/06/2023. We excluded tests from patients with previously positive HIV serology results. We obtained the annual number of patients assigned to each primary care centre from each centre’s database. All the tests were processed as a yearly anonymised batch, and researchers did not have access to the personal information of the patients other than date of birth, sex, and in those who were positive, the first CD4 count and viral load.

To calculate the rates of late and advanced HIV diagnoses, we used data from CoRIS, a prospective multicentre cohort of individuals with HIV infection. The cohort includes more than 19,000 antiretroviral treatment (ART)-naïve patients starting in 01/01/2004 and a censoring date on 30/11/2022. Data was accessed on 01/09/2023. Patients were recruited across 47 centres in 14 autonomous regions in Spain. The recorded data includes anonymized clinical and epidemiological information, and internal quality controls are performed annually, with 10% of the data being externally audited every two years[

23]. We extracted anonymized clinical and demographic information, including sex, date of birth, nationality, educational level, date of the first positive test, date of any previous negative HIV test, HIV acquisition route, hospital of inclusion, and relevant immunological and virological markers, including first CD4+ T cells and first viral load (VL), CDC classification at diagnosis, and date of first AIDS-defining illness.

We defined late diagnosis, according to the 2022 definition by Croxford et al., as a CD4 count <350 cells per µL and/or the presence of an AIDS-defining illness at the time of diagnosis, without evidence of recent seroconversion[

6]. We defined advanced HIV disease as the presence of an AIDS-defining illness upon HIV diagnosis or in the six months following the diagnosis.

Objectives

Our primary objective was to describe the evolution of HIV testing rates before and after the training session, considering an extended follow-up period of five years. The secondary objectives were to describe and compare the rates of late diagnosis and advanced HIV diagnosis in our cohort and the CoRIS cohort in the five years before and after the intervention.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the rates of requested and positive HIV tests per 100,000 patients and compared paired quantitative variables with Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test. We performed a descriptive analysis of the baseline characteristics of HIV-positive patients using frequency distributions and between-group comparisons using the χ2 test. We compared the rates of late HIV diagnosis and advanced HIV disease in both groups before and after the training sessions. We used logistic regression to obtain association measures (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]) and included age, sex, geographical origin, mode of transmission, and level of education as covariates. We used Stata v.18 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA) to perform all statistical analyses and GraphPad Prism v.10 (GraphPad Software Inc.) to generate the figures.

3. Results

Of the 630 primary care providers working at the 20 target primary care centres, 454 (72%) attended the sessions. Martínez-Sanz et al. [

12] described the characteristics of the providers who answered the questionnaire during the session, which is shown in

Tables S1A and S1B.

3.1. Number of Tests and Positive HIV Test Results

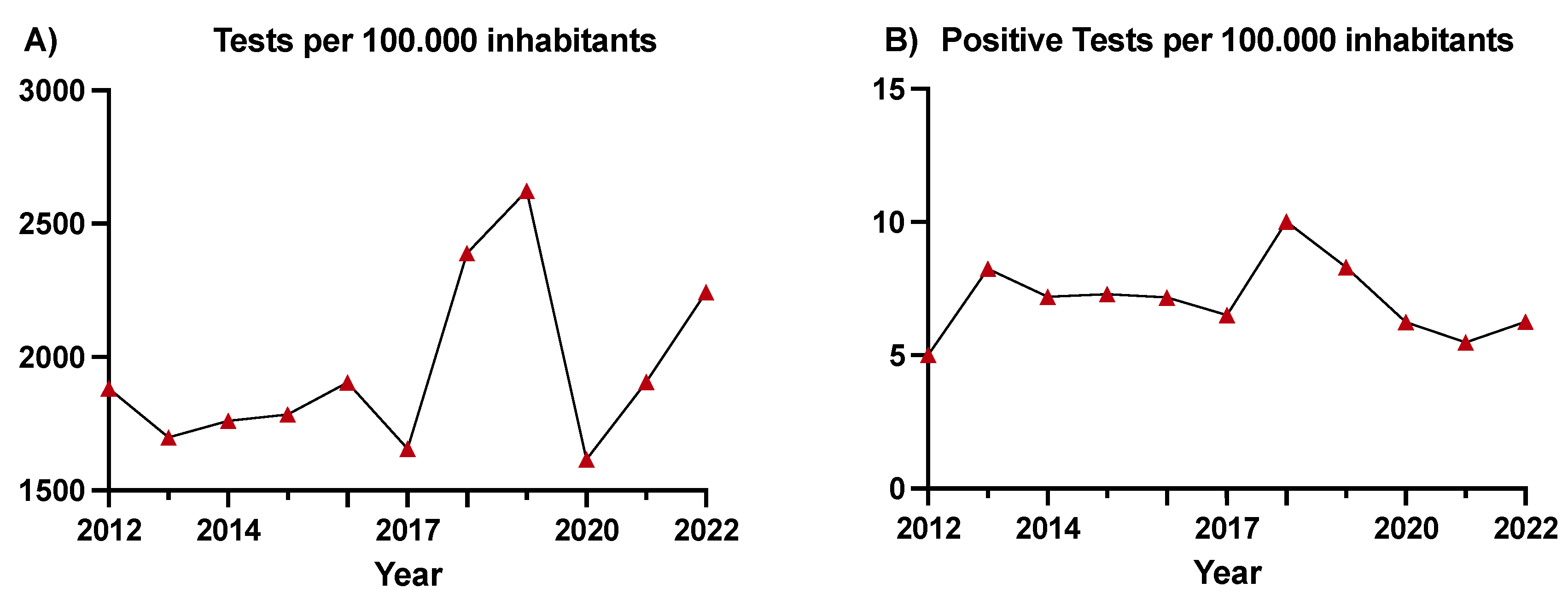

The average annual rate of HIV screening was 1,780 tests per 100,000 inhabitants in the period preceding the intervention and 2,155 tests per 100,000 inhabitants in the period after the intervention (p<0.0001), despite a reduction in testing during 2020 (1,615 tests per 100,000 inhabitants) (

Figure 1A). The rate of positive tests was 7 per 100,000 inhabitants before and 7.3 per 100,000 inhabitants after the intervention (p=0.676), showing an initial increase of up to 10 positive tests per 100,000 inhabitants until 2020 and lower rates thereafter (

Figure 1B). The overall number of tests, positive tests, and number of assigned patients per year are shown in the Supplementary Material,

Table S2.

3.2. Characteristics of Patients Newly Diagnosed with HIV

We included 10,184 patients newly diagnosed with HIV, 341 of whom belonged to centres with intervention.

Table 1 shows the distribution of the new HIV diagnoses in the cohort and their demographic characteristics. These participants were predominantly male (88.4%), middle-aged, born in Spain, and had sex with men (MSM). Both groups were comparable, except for a greater percentage of Spanish patients in the pre-session period and a greater rate of MSM in the post-session period in the intervention group.

3.3. Late Diagnosis and Advanced HIV Disease upon Diagnosis

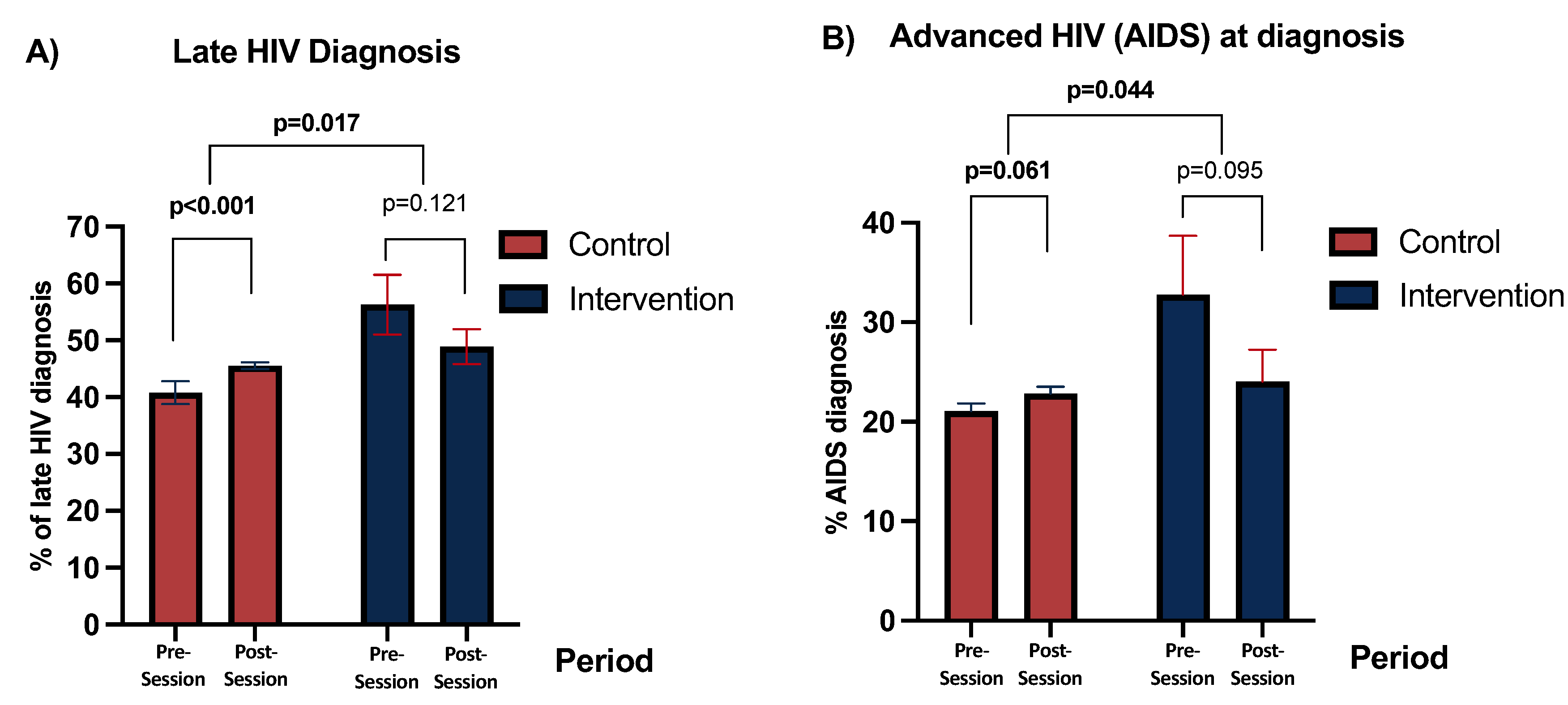

Overall, there was a significant increase in the rate of late HIV diagnosis in the 2017-2022 period compared to the 2012-2017 period (40.5% to 45.6%, p<0.0001). However, the rate of advanced HIV disease remained stable (21.9% to 22.8%) (

Table 1).

Among the new diagnoses made in the Ramón y Cajal Hospital area, the rate of late diagnosis decreased from 58.9% in the first period to 48.7% in the second period (AOR 0.70 [95%CI 0.45–1.09], p=0.121). In the rest of Spain, late diagnosis significantly increased between the two periods (AOR, 1.22 [95%CI 1.13–1.33], p<0.001) (

Table 1,

Figure 2A). When comparing both differences, there was a significant reduction in late diagnosis in patients from the centres with intervention compared to the rest of Spain (p=0.017) (

Figure 2A).

Regarding the rate of advanced HIV disease, the centres with intervention showed a borderline-significant reduction in AOR 0.66 [95%CI 0.40-1.08], p=0.095) (Table 2,

Figure 2), whereas the rest of Spain showed a borderline significant increase (AOR 1.10, [95%CI, 0.99-1.22]; p=0.061) (

Table 1,

Figure 2B). The comparison of both differences showed a significant decrease in advanced HIV disease in the intervention group compared to that in the control group (p=0.044) (

Figure 2B).

We performed sensitivity analyses comparing the intervention group with the rest of the Community of Madrid instead of the rest of Spain, yielding similar results (Supplementary Material

Table S3).

4. Discussion

This study highlights the positive impact of a low-effort training session on HIV testing and positivity rates in primary care centres across a health area in Madrid, Spain. Following the intervention, we noted a significant reduction in late HIV diagnoses, a metric that initially was higher in our area compared to the rest of Madrid and Spain. Interestingly, while the rest of Madrid and Spain saw an increase in late diagnoses, our area showed improvement. Our findings also revealed a national trend of increasing late HIV presentations, consistent with trends reported across Spain [

24] and Europe [

4], whereas our local cohort showed a modest reduction.

Recent studies have identified late diagnosis as one of the main drivers of ongoing transmission in middle- and high-income countries, despite substantial improvements in other stages of the care continuum in recent years [

1,

2,

3]. However, strategies to mitigate late diagnoses are still lacking, with initiatives like universal opt-out screening only implemented in specific regions and settings [

7,

8].

In Spain and many other European countries, HIV diagnosis primarily relies on primary care physicians identifying indicator conditions. These physicians often face significant challenges, including being overwhelmed by the number of patients they see daily, dealing with HIV-related stigma [

25,

26,

27,

28], staying updated with the latest HIV testing guidelines, and encountering various barriers to testing [

12]. Our group has previously demonstrated that formative sessions with hospital specialists can temporarily improve HIV testing and diagnosis rates [

11]. Additionally, structured HIV testing programs in emergency departments and primary care centres have been shown to enhance physicians’ awareness and implementation of HIV testing [

12,

21].

Our data reinforce the idea that a formative session can increase the number of people screened for and diagnosed with HIV. This increased screening reduced the rate of late diagnosis in our area, while rates in the rest of Spain and Madrid continued to rise. Although the increase in testing and positivity rates might seem small, a 20% increase from a low-effort training session is significant and directly addresses the main gap in the HIV care cascade [

1,

2]. HIV tests are very cheap compared to the costs of late HIV diagnosis. Therefore, implementing such strategies more broadly might help counteract the rising trends in late diagnosis [

4,

24] that public awareness strategies have not yet improved.

The baseline rate of late diagnosis was higher in our population than in the rest of Madrid and Spain. Despite the intervention, our most recent rate remained slightly higher, and the reasons for this are unclear. However, some factors may explain this. First, our hospital serves as a reference for many NGOs due to its easy access to healthcare, even for people with irregular status in our country. Recently, Palich and collaborators [

29] in France reported that most migrants diagnosed with HIV acquire the infection after migration and higher rates of late diagnosis in this group are linked to social and economic disadvantages. Second, our hospital proactively includes every HIV diagnosis in CoRIS with patient consent, even those acutely ill and diagnosed as inpatients. We cannot confirm if other hospitals in the cohort do the same. Still, the Spanish Ministry of Health’s annual report shows similar rates of late diagnosis and AIDS stage at diagnosis [

24] as we report in CoRIS, suggesting that most other centres also include their critically ill patients.

Our study had some limitations. First, we might not be aware of small local strategies to improve HIV screening implemented in different regions during the study period. However, this does not change the interpretation of our results, as the trend in our area differs from others, regardless of their strategies to address late diagnosis. Second, CoRIS does not include all patients diagnosed with HIV in Spain, though the nationally reported rates of late diagnosis are similar to those in our cohort [

24]. Finally, COVID-19 interrupted the presumed effect of our intervention in 2020, significantly disrupting healthcare systems and access to care for many patients [

30,

31,

32]. Still, data from the following years suggests that the screening rate returned to pre-COVID levels in 2022.

Despite these limitations, we present systematic data from all HIV tests performed in our area and from a large, well-structured, prospective cohort with audited and updated data up to November 30, 2022. The results for the number of tests and late diagnoses are consistent with the presumed effect of the sessions and similar published strategies.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, a two-hour low-effort training session for primary care providers increases HIV testing rates. It reduces late diagnoses compared to the trends in a nationwide Spanish cohort of HIV ART-naïve patients. Implementing similar strategies on a broader scale could help mitigate the rising rates of late HIV diagnosis and improve overall community health outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, includes tables S1B (population characteristics by professional category), S1B (characteristics of providers according to previous offer of an HIV test, Table S2 (Absolute number of HIV tests, HIV positive tests, and assigned population per year, segregated by gender) and Table S3 (Number of HIV late diagnoses and diagnoses in advanced stage in the hospitals of Madrid included in CoRIS, after excluding those from Ramón y Cajal Hospital).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Alejandro G. García-Ruiz de Morales, María Jesús Vivancos, Santiago Moreno, Javier Martínez-Sanz and María Jesús Pérez-Elías; Data curation, Beatriz Romero-Hernández, David Rial-Crestelo, Francisco Arnaiz de las Revillas, Jorge Sanchez-Villegas, Marta Montero-Alonso, María de la Villa López Sánchez and María Remedios Alemán Valls; Formal analysis, Alejandro G. García-Ruiz de Morales, David Rial-Crestelo and Javier Martínez-Sanz; Funding acquisition, María Jesús Vivancos and María Jesús Pérez-Elías; Investigation, Alejandro G. García-Ruiz de Morales, Beatriz Romero-Hernández, Francisco Arnaiz de las Revillas, Javier Martínez-Sanz and María Jesús Pérez-Elías; Methodology, Alejandro G. García-Ruiz de Morales, María Jesús Vivancos, Santiago Moreno, Javier Martínez-Sanz and María Jesús Pérez-Elías; Project administration, Javier Martínez-Sanz and María Jesús Pérez-Elías; Resources, María Jesús Vivancos, Beatriz Romero-Hernández, David Rial-Crestelo, Francisco Arnaiz de las Revillas, Jorge Sanchez-Villegas, Marta Montero-Alonso, María de la Villa López Sánchez, María Remedios Alemán Valls, Javier Martínez-Sanz and María Jesús Pérez-Elías; Software, María Jesús Pérez-Elías; Supervision, María Jesús Vivancos, Santiago Moreno, Javier Martínez-Sanz and María Jesús Pérez-Elías; Validation, Alejandro G. García-Ruiz de Morales, David Rial-Crestelo, Javier Martínez-Sanz and María Jesús Pérez-Elías; Writing – original draft, Alejandro G. García-Ruiz de Morales, Santiago Moreno, Javier Martínez-Sanz and María Jesús Pérez-Elías; Writing – review & editing, Alejandro G. García-Ruiz de Morales, María Jesús Vivancos, Beatriz Romero-Hernández, David Rial-Crestelo, Francisco Arnaiz de las Revillas, Jorge Sanchez-Villegas, Marta Montero-Alonso, María de la Villa López Sánchez, María Remedios Alemán Valls, Santiago Moreno, Javier Martínez-Sanz and María Jesús Pérez-Elías

Funding

This study was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) through project PI22/01878, Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, and co-funded by the European Union. CoRIS cohort is supported by CIBER – Consorcio Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red- (CB21/13/00091), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación and Unión Europea – NextGenerationEU. The funders had no role in the study design, data analysis, or interpretation of results.

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in this study can be obtained through reasonable requests from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the CoRIS cohort and all the participants who made this study possible.

Ethics: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Carlos III Health Institute, Madrid, Spain, and the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Ramón y Cajal (ceic.hrc@salud.madrid.org, approval number 001-23), who granted a waiver for informed consent for the retrospective use of the anonymised data extracted from the microbiology department. The CoRIS committee approved the use of the CoRIS cohort data in the study with no need of further informed consent, as all the participants enrolled in the CoRIS cohort provided written informed consent to allow the use of their anonymised personal data for research purposes (proyectoscoris@isciii.es, approval number RIS EPICLIN 02/2023).

Conflicts of Interest

A.G.G.-R.d.M. reports personal fees from ViiV Healthcare, non-financial support from ViiV Healthcare, Jannsen Cilag, and Gilead Sciences, and research grants from Gilead Sciences outside the submitted work. MJV has received honoraria (grants and personal fees) as a speaker in educational programmes sponsored by ViiV and Gilead and has received support (registration, travel assistance) for expert courses and congresses from Gilead, MSD and ViiV. J.M.-S. reports personal fees from ViiV Healthcare, Janssen Cilag, Gilead Sciences, and MSD; non-financial support from ViiV Healthcare, Jannsen Cilag, and Gilead Sciences; and research grants from Gilead Sciences outside the submitted work. SM reports grants, personal fees, and non-financial support from ViiV Healthcare, personal fees, and non-financial support from Janssen, grants, personal fees, and non-financial support from MSD, grants, personal fees, and non-financial support from Gilead, outside the submitted work.

References

- García-Ruiz de Morales, A.G.; Vivancos, M.J.; de Lagarde, M.; Ramírez Schacke, M.; del Mar Arcos Rueda, M.; Orviz, E.; Curran, A.; Carmona-Torre, F.; Moreno, S.; Pérez-Elías, M.J.; et al. Transition Times across the HIV Care Continuum in Spain from 2005 to 2022: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Lancet HIV 2024, 11, e470–e478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuzin, L.; Morisot, A.; Allavena, C.; Lert, F.; Pugliese, P.; Group, the D. S. Drastic Reduction in Time to Controlled Viral Load in People With Human Immunodeficiency Virus in France, 2009–2019: A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2023, 78, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Santen, D.K.; Mepi, A.; Traeger, M.W.; Mepi, E.-H.; Hellard, M.; Van Santen, (D K; El-Hayek, C. ; Callander, (D; Donovan, B.; Petoumenos, K.; et al. Improvements in Transition Times through the HIV Cascade of Care among Gay and Bisexual Men with a New HIV Diagnosis in New South Wales and Victoria, Australia (2012-19): A Longitudinal Cohort Study. Lancet HIV 2021, 8, 623–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; WHO Regional Office for Europe HIV/AIDS Surveillance in Europe – 2022 Data. 2023.

- Jarrín, I.; Rava, M.; Domínguez-Domínguez, L.; Bisbal, O.; López-Cortés, L.F.; Busca, C.; Antela, A.; González-Ruano, P.; Hernández, C.; Iribarren, J.A.; et al. Late Presentation for HIV Remains a Major Health Issue in Spain: Results from a Multicenter Cohort Study, 2004–2018. PLoS One 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croxford, S.; Stengaard, A.R.; Brännström, J.; Combs, L.; Dedes, N.; Girardi, E.; Grabar, S.; Kirk, O.; Kuchukhidze, G.; Lazarus, J. V.; et al. Late Diagnosis of HIV: An Updated Consensus Definition. HIV Med 2022, 23, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haukoos, J.S.; Hopkins, E.; Bucossi, M.M. Routine Opt-Out HIV Screening: More Evidence in Support of Alternative Approaches? Sex Transm Dis 2014, 41, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, P.W.; Messer, L.C.; Myers, E.R.; Weber, D.J.; Leone, P.A.; Miller, W.C. Impact of a Routine, Opt-Out HIV Testing Program on HIV Testing and Case Detection in North Carolina Sexually-Transmitted Disease Clinics. Sex Transm Dis 2014, 41, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Sanidad, S.S. e I.; Plan Nacional sobre Sida Guía de Recomendaciones Para El Diagnóstico Precoz de VIH En El Ámbito Sanitario. 2014.

- Plan Nacional sobre el, Sida; Ministerio de Sanidad, C. Plan Nacional sobre el Sida; Ministerio de Sanidad, C. y B.Social. Guía Para La Realización de Pruebas Rápidas Del VIH En Entornos Comunitarios. 2019.

- García-Ruiz de Morales, A.G.; Martínez-Sanz, J.; Vivancos-Gallego, M.J.; Sánchez-Conde, M.; Vélez-Díaz-Pallarés, M.; Romero-Hernández, B.; Vázquez, M.D.G.; de Luque, C.M.C.; González-Sarria, A.; Galán, J.C.; et al. HIV and HCV Screening by Non-Infectious Diseases Physicians: Can We Improve Testing and Hidden Infection Rates? Front Public Health 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sanz, J.; Pérez Elías, M.J.; Muriel, A.; Ayerbe, C.G.; Vivancos Gallego, M.J.; Sanchez Conde, M.; Herrero Delgado, M.; Pérez Elías, P.; Polo Benito, L.; de la Fuente Cortés, Y.; et al. Outcome of an HIV Education Program for Primary Care Providers: Screening and Late Diagnosis Rates. PLoS One 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joore, I.K.; Van Bergen, J.E.A.M.; Ter Riet, G.; Van Der Maat, A.; Van Dijk, N. Development and Evaluation of a Blended Educational Programme for General Practitioners’ Trainers to Stimulate Proactive HIV Testing. BMC Fam Pract 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayuelas Redondo, L.; Ruíz, M.; Kostov, B.; Sequeira, E.; Noguera, P.; Herrero, M.A.; Menacho, I.; Barba, O.; Clusa, T.; Rifa, B.; et al. Indicator Condition-Guided HIV Testing with an Electronic Prompt in Primary Healthcare: A before and after Evaluation of an Intervention. Sex Transm Infect 2019, 95, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llibre, M.; Vliegenthart-Jongbloed, K.J.; Vasylyev, M.; Jordans, C.C.E.; Bernardino, J.I.; Nozza, S.; Psomas, C.K.; Voit, F.; Barber, T.J.; Skrzat-Klapaczy’nska, A.; et al. Systematic Review: Strategies for Improving HIV Testing and Detection Rates in European Hospitals. Microorganisms 2024, Vol. 12, Page 254 2024, 12, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon Ellis; Hilary Curtis; Edmund LC Ong; on behalf of the British HIV Association (BHIVA) and BHIVA Clinical Audit and Standards sub-committee HIV Diagnoses and Missed Opportunities. Results of the British HIV Association (BHIVA) National Audit 2010. Clinical Medicine 2012, 12, 430–434. [CrossRef]

- Deblonde, J.; Van Beckhoven, D.; Loos, J.; Boffin, N.; Sasse, A.; Nöstlinger, C.; Supervie, V. HIV Testing within General Practices in Europe: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.C.; Sepkowitz, K.A.; Bernstein, K.T.; Karpati, A.M.; Myers, J.E.; Tsoi, B.W.; Begier, E.M. Why Don’t Physicians Test for HIV? A Review of the US Literature. AIDS 2007, 21, 1617–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.Y.; Suneja, A.; Chou, A.L.; Arya, M. Physician Barriers to Successful Implementation of US Preventive Services Task Force Routine HIV Testing Recommendations. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2014, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sanz, J.; Vivancos, M.J.; Sánchez-Conde, M.; Gómez-Ayerbe, C.; Polo, L.; Labrador, C.; González, P.; Mesa, A.; Muriel, A.; Chamorro, C.; et al. Hepatitis C and HIV Combined Screening in Primary Care: A Cluster Randomized Trial. J Viral Hepat 2021, 28, 345–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Ayerbe, C.; Martínez-Sanz, J.; Muriel, A.; Elías, P.P.; Moreno, A.; Barea, R.; Polo, L.; Cano, A.; Uranga, A.; Santos, C.; et al. Impact of a Structured HIV Testing Program in a Hospital Emergency Department and a Primary Care Center. PLoS One 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Optimising Testing and Linkage to Care for HIV (OptTEST by HIV in Europe) Available online:. Available online: http://www.opttest.eu/ (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Sobrino-Vegas, P.; Gutiérrez, F.; Berenguer, J.; Labarga, P.; García, F.; Alejos-Ferreras, B.; Muñoz, M.A.; Moreno, S.; Del Amo, J. La Cohorte de La Red Española de Investigación En Sida y Su Biobanco: Organización, Principales Resultados y Pérdidas al Seguimiento. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2011, 29, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sistema de Información sobre Nuevos Diagnósticos de VIH y Registro Nacional de Casos de, Sida; Centro Nacional de, Epidemiología.; Instituto de Salud Carlos III/ División de control de VIH, I.H. Sistema de Información sobre Nuevos Diagnósticos de VIH y Registro Nacional de Casos de Sida; Centro Nacional de Epidemiología.; Instituto de Salud Carlos III/ División de control de VIH, I.H. viral y tuberculosis; Ministerio de Sanidad Unidad de Vigilancia de VIH, ITS y Hepatitis. Vigilancia Epidemiológica Del VIH y Sida En España 2022. 2023.

- Rayment, M.; Thornton, A.; Mandalia, S.; Elam, G.; Atkins, M.; Jones, R.; Nardone, A.; Roberts, P.; Tenant-Flowers, M.; Anderson, J.; et al. HIV Testing in Non-Traditional Settings--the HINTS Study: A Multi-Centre Observational Study of Feasibility and Acceptability. PLoS One 2012, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, A.C.; Rayment, M.; Elam, G.; Atkins, M.; Jones, R.; Nardone, A.; Roberts, P.; Tenant-Flowers, M.; Anderson, J.; Sullivan, A.K. Exploring Staff Attitudes to Routine HIV Testing in Non-Traditional Settings: A Qualitative Study in Four Healthcare Facilities. Sex Transm Infect 2012, 88, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casalino, E.; Bernot, B.; Bouchaud, O.; Alloui, C.; Choquet, C.; Bouvet, E.; Damond, F.; Firmin, S.; Delobelle, A.; Nkoumazok, B.E.; et al. Twelve Months of Routine HIV Screening in 6 Emergency Departments in the Paris Area: Results from the ANRS URDEP Study. PLoS One 2012, 7, e46437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokhi, D.S.; Oxenham, C.; Coates, R.; Forbes, M.; Gupta, N.K.; Blackburn, D.J. Four-Stage Audit Demonstrating Increased Uptake of HIV Testing in Acute Neurology Admissions Using Staged Practical Interventions. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0134574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palich, R.; Arias-Rodríguez, A.; Duracinsky, M.; Le Talec, J.Y.; Rousset Torrente, O.; Lascoux-Combe, C.; Lacombe, K.; Ghosn, J.; Viard, J.P.; Pialoux, G.; et al. High Proportion of Post-Migration HIV Acquisition in Migrant Men Who Have Sex with Men Receiving HIV Care in the Paris Region, and Associations with Social Disadvantage and Sexual Behaviours: Results of the ANRS-MIE GANYMEDE Study, France, 2021 to 2022. Euro Surveill 2024, 29, 2300445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, S.; Poongulali, S.; Kumarasamy, N. Impact of COVID-19 on People Living with HIV: A Review. J Virus Erad 2020, 6, 100019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-Hernández, B.; Martínez-García, L.; Rodríguez-Dominguez, M.; Martínez-Sanz, J.; Vélez-Díaz-Pallarés, M.; Pérez Mies, B.; Muriel, A.; Gea, F.; Pérez-Elías, M.J.; Galán, J.C. The Negative Impact of COVID-19 in HCV, HIV, and HPV Surveillance Programs During the Different Pandemic Waves. Front Public Health 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.H.; Barth, S.K.; Monroe, A.K.; Ahsan, S.; Kovacic, J.; Senn, S.; Castel, A.D. The Impact of COVID-19 on the HIV Continuum of Care: Challenges, Innovations, and Opportunities. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2023, 21, 831–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).