1. Introduction

When evisceration of the eyeball is performed due to trauma or ocular disease, the eyeball collapses. However, the volume of the ocular prosthesis alone is insufficient to compensate for the lost volume in the orbit, and enophthalmos develops on the affected side alongside the asymmetry of the upper eyelid, creating a cosmetically unnatural appearance. This is especially likely in patients with orbital fractures, [

1] as the intraorbital volume is enlarged by the fracture. Furthermore, in many cases, patients who have used a thick, heavy ocular prosthesis for a long period have difficulty wearing it because the socket changes over time owing to the load of the ocular prosthesis, causing it to fall out or cause pain. A wide range of materials can be used during orbital implant surgery.[

2,

3] However, in Japan, artificial materials such as acrylic or hydroxyapatite are no longer approved as medical materials. Consequently, autologous tissues, such as costal cartilage[

4] must be harvested, processed, and grafted. Therefore, orbital implant surgery is only performed at a limited number of centers in Japan. This procedure can improve the quality of life of ocular prosthesis users and has significant advantages. Our department uses costal cartilage grafts as orbital implants after eyeball evisceration.

The purpose of this study was twofold: to report the short-term outcomes of our institution’s orbital implant surgery protocol and to clarify the cosmetic perspective of this procedure by comparing the positions of the upper eyelids of patients who underwent this procedure and those who did not. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

The group that underwent cartilage grafting shows significantly less upper eyelid asymmetry.

In cases involving orbital fractures, additional surgery is often required due to enophthalmos or blepharoptosis resulting from increased orbital volume caused by insufficient orbital fracture reduction.

Significant inter-individual differences were observed in upper eyelid positions; therefore, we focused on comparing the “degree of asymmetry” between the group that underwent costal cartilage grafting and the group that did not. Asymmetry was quantified by assessing left-to-right side differences within individual cases for both groups.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design/sample

First, this was a retrospective study. The study population comprised patients with ocular prostheses reviewed at our Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery between October 2019 and April 2023. Two groups were studied: Group 1, comprising patients who underwent evisceration of the eyeball and orbital implant graft with costal cartilage, and Group 2, comprising individuals who used a prosthetic eye without orbital implants.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Clinical Research Review Committee of Tokai University (approval number: 24R077-001 MH). Since this was a retrospective study conducted in an opt-out format, it was not necessary to obtain informed consent from all patients; however, informed consent was obtained from patients whose face photographs could be used.

2.2. Surgical technique for one-stage surgery

The surgical technique followed the principles that have been published previously.[

5] The first step involved the identification of the four external ocular muscles (superior, inferior, medial, and lateral rectus muscles) and evisceration of the eyeball by an ophthalmologist (

Figure 1A). At the same time, plastic surgeons harvested costal cartilage through a skin incision on the right side of the chest. For females, the incision was made in line with the inframammary folds. The sixth costal cartilage was often used. The strips were then cut from the harvested costal cartilage and wrapped around the core cartilage pieces to create a spherical cartilage ball. The diameter of the prosthesis was approximately 20–23 mm. In elderly patients with severe costal cartilage calcification, it was not possible to make or bend the strips; therefore, a bundle was made by combining large blocks, and the surrounding area was shaved to form a sphere (

Figure 1B–D). This was followed by the creation of four scleral flaps using the extraocular muscles as pedicles (

Figure 1E), which were subsequently used to cover the costal cartilage ball implants (

Figure 1F, G).

The superior rectus muscle is kept attached to the sclera using a silk thread as a landmark(A). The spherical orbital prosthetic implant can be made with a small volume of costal cartilage(B). In elderly patients, the costal cartilage is highly calcified; hence, four blocks of cartilage are assembled, and then the surface is scraped with a motorized tool to fashion it into a sphere. In this case, the amount of rib cartilage to be harvested is greater (C and D). Four scleral flaps are shown unfolded. The posterior part of the sclera is detached around the optic nerve papilla (E). Each rectus muscle serving as the pedicle of the flap(F). The scleral flaps are sutured together using absorbable thread (G).

2.3. Variables

Data were collected on the following variables: age, sex, cause of blindness, preoperative complications/risks, and postoperative complications/additional surgery/symmetry of the upper eyelid protrusion. Upper eyelid protrusion was quantified using 3D images taken with VECTRA H2 imaging software version 7.4.6 (Canfield, Parsippany, NJ, USA).

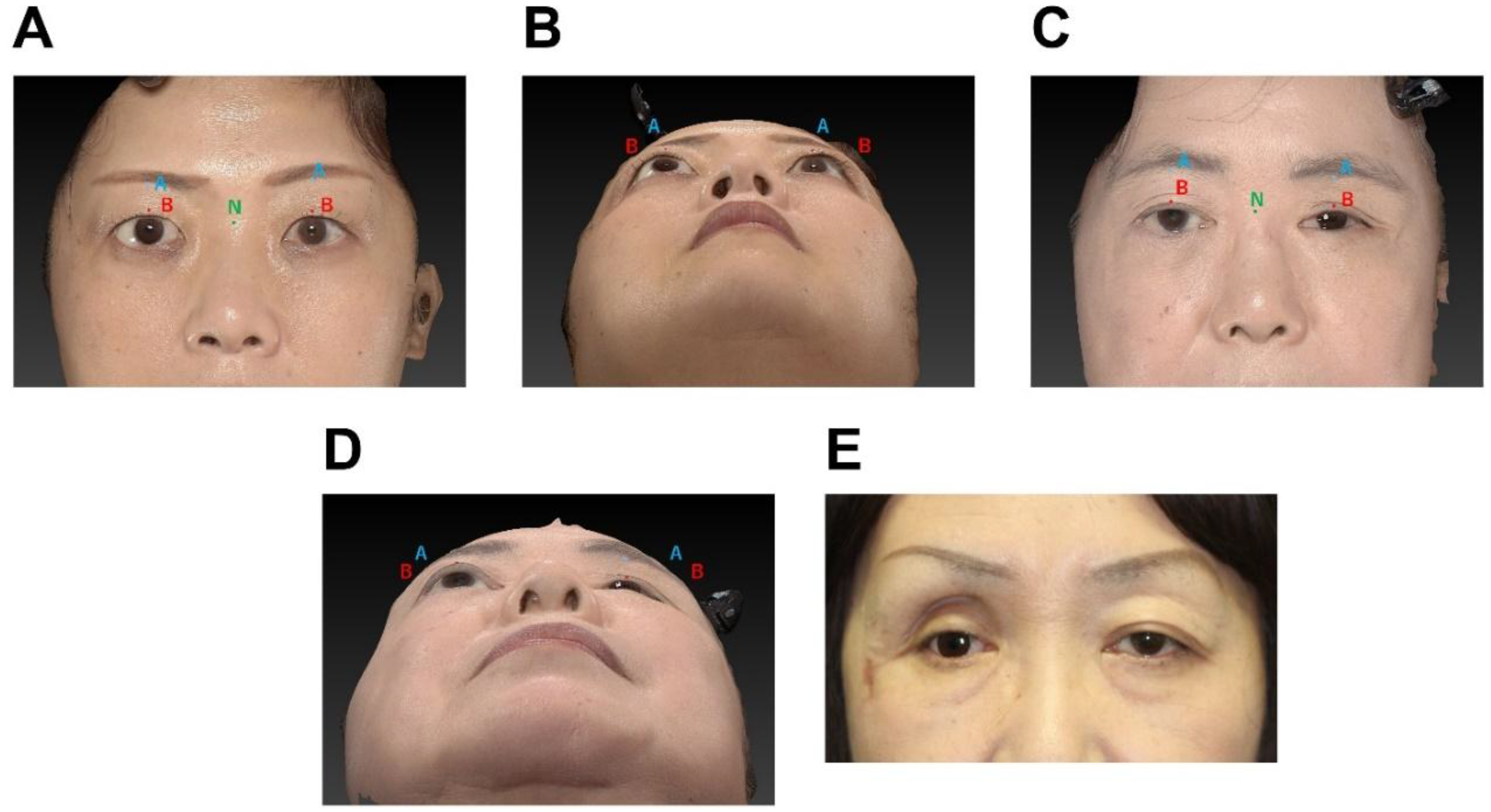

In this study, the anteroposterior positions of the two points on the upper eyelid (points A and B) were measured using the nasal radix (point N) as the reference point (

Figure 2). Points A, B, and N were defined as the median point of the supraorbital rim, the median point of the upper eyelid margin, and the most recessed point of the nasal root, respectively.

2.4. Data collection methods

Data on demographic and clinical variables were collected by reviewing the medical records. The imaging-based measurements were performed using the VECTRA H2 imaging software version 7.4.6.

2.5. Data analysis

Mann–Whitney U tests and chi-square tests were used to compare Groups 1 and 2 on the above measures. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 4.1.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), with a significance level of 0.05.

3. Results

The study population comprised 23 patients with ocular prostheses: 13 in Group 1 and 10 in Group 2. Out of the 13 cases in Group 1, one patient lacked postoperative 3D imaging data, making it impossible to evaluate "symmetry of upper eyelid protrusion." Therefore, this case was excluded from this parameter. The age distribution of the two study groups was significantly different. Group 1 had a significantly lower median age of 52 years (IQR: 35.50–62.50), whereas Group 2 had a median age of 68 years (IQR: 62.25–76.00), with a P value of 0.002, indicating statistical significance (Mann–Whitney U test). The sex distribution among the participants was significantly different between the two groups. In Group 1, three (23.1%) participants were male and 10 (76.9%) were female; however, in Group 2, three (30.0%) were female and seven (70.0%) were male, indicating a significant sex difference (chi-square test P value=0.024).

Regarding the side of ocular prosthesis, Group 1 had an almost equal distribution between left and right sides, with 6 (46.2%) having a left ocular prosthesis and 7 (53.8%) having a right ocular prosthesis. In Group 2, the left side was more prevalent (n=8, 80.0%) than the right side (n=2, 20.0%), although the difference between Groups 1 and 2 was not statistically significant (P=0.099, chi-square test).

The causes of blindness varied among the participants. The leading cause in Group 1 was injury (n=7, 53.8%), followed by congenital blindness (n=2, 15.4%), diabetic retinopathy (n=2, 15.4%), and keratitis (n=2, 15.4%). In Group 2, injury was the predominant cause (n=7, 70.0%), with additional cases due to cytomegalovirus (n=1, 10.0%), septic endophthalmitis (n=1, 10.0%), and thyroid eye disease (n=1, 10.0%) (

Table 1).

A comparison of the upper eyelid measurements according to groups (1 and 2), measurement points (A and B), and sides (normal and affected) is presented in

Table 2. The results showed no statistically significant differences in the Point A or Point B values between the normal and affected sides in both Groups 1 and 2, except for the Point A values on the affected side. These were significantly lower for Group 2 (median: -6.47, IQR: -15.08 to -4.96) than for Group 1 (median: -4.23, IQR: -6.28 to -2.59; P=0.042, Mann–Whitney U test).

To further analyze the differences in Points A and B measurements between individuals in Groups 1 and 2, we compared upper eyelid asymmetry using the differences between the normal and affected sides for each case (

Table 2).

At Point A, Group 1 had a median difference of 0.75 (IQR: -0.26–2.44), whereas Group 2 showed a more pronounced asymmetry with a median difference of 3.23 (IQR: 2.42–5.11). The associated P value of 0.003 (Mann–Whitney U test) indicated a statistically significant difference between the groups at Point A. Similarly, for Point B, Group 1 had a median difference of 0.86 (IQR: -0.53–1.78), and Group 2 had a median of 4.20 (IQR: 2.29–5.80), with a P value of 0.001 (Mann–Whitney U test), indicating a significant difference between the groups at this point. These results suggest that Group 2 exhibited more upper eyelid asymmetry than Group 1 at both Points A and B.

Preoperative complications in Group 1 included orbital fractures (n=5, 38.5%), multiple facial fractures (n=2, 15.4%), and bulbar atrophy (n=1, 7.7%). The most common postoperative complication was isolated blepharoptosis (n=3, 23.1%), with 5 (38.5%) reporting no complications (

Table 3).

Among Group 1 participants, additional surgeries were performed in eight (61.5%) cases, with blepharoptosis surgery and conjunctival sacroplasty being the most common procedures (n=5, 38.5% each) (

Table 4). All (100%) participants with orbital fractures required additional surgery, while only five (37.5%) of those without fractures required additional surgery, a difference that was not statistically significant (P=0.075, Fisher’s exact test) (

Table 5). The specific additional surgeries performed in the five patients with orbital fractures were as follows: blepharoptosis surgery (n=4, 80%; levator aponeurosis tucking in three patients; frontalis suspension in one patient), conjunctival sacroplasty (n=3, 60%), and revision surgery for chronic orbital fracture repair (n=2, 40%).

4. Discussion

The purpose of this study was to report the short-term outcomes of our institution’s orbital implant surgery protocol using autologous costal cartilage and to quantify and compare the upper eyelid shape between patients who underwent this procedure and those who did not. Several interesting results are obtained. First, our results suggest that Group 2 exhibited more upper eyelid asymmetry than Group 1 at both Points A and B. These findings suggest that orbital implant surgery with costal cartilage grafts leads to better symmetry and improved cosmetic appearance.

In this study, measurements were performed using 3D camera VECTRA software. Measurement methods relying on computed tomography imaging have been shown to not correlate with subjective clinical assessment in cases of orbital fractures, [

6] which is highly relevant to this study, given the importance that patients tend to place on cosmetic appearance, supporting the role of subjective assessments of asymmetry rather than CT-based assessments.

Second, no significant association was observed between the presence of orbital fractures and the need for additional surgery. However, all five cases with orbital fractures required additional surgery. This was attributed to the insufficient correction of the expanded orbital volume, which led to enophthalmos and blepharoptosis. In this study, revision surgery for chronic orbital fracture repair was performed in two cases. However, in cases of chronic fractures, even if the orbital volume is restored to match the unaffected side, severe scar contracture of the orbital contents, including the optic nerve, impedes the advancement of the orbital implant. Moreover, the tissues covering the anterior surface of the implant contract and lack elasticity, further restricting advancement. Even when enophthalmos improved, the conjunctival sac became shallow, necessitating conjunctival sacroplasty. Therefore, in cases of globe rupture with orbital fracture, early and accurate orbital volume repair is very important to avoid enophthalmos.[

7,

8] Despite the accurate repair and fixation of orbital fractures, some reports indicate that further bone grafting is necessary.[

9] However, excessive overcorrection may impede ocular motility, presenting significant challenges in achieving optimal balance.

In patients with significant preoperative bulbar atrophy, the scleral flap size is sufficient to cover only the anterior surface of the costal cartilage implant, and the conjunctival area is insufficient, necessitating secondary conjunctival sacroplasty.

This study has some limitations. First, the sample size was small, and patients were recruited from a single center, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. Additional studies from multiple centers are required to confirm the findings of this study. Second, potential bias in the allocation to Groups 1 and 2 exists, as the choice to undergo orbital implant surgery was not randomized but instead determined through agreement between the ophthalmologist and the surgeon. Therefore, biases may have influenced surgical decisions, with ophthalmologists likely guiding patients' choices. Third, the decision to undergo additional surgery for complications is influenced by the patient’s wishes; therefore, it is not necessarily correlated with complication severity. Fourth, significant differences in age and sex existed between the two groups in this study. This is likely because the main purpose of the surgery is cosmetic improvement, and it can be assumed that elderly patients, particularly males, are less likely to request additional surgery. Additionally, because costal cartilage harvesting can be associated with postoperative pain and carries a small but real risk of pleural injury, elderly patients may wish to avoid the risk of additional comorbidities.

In conclusion, our study suggests that orbital implant surgery with costal cartilage grafts leads to improved symmetry and cosmetic appearance. Furthermore, our data support the notion that an orbital implant is necessary to compensate for the orbital content. Early and accurate orbital volume repair is important to prevent enophthalmos and blepharoptosis.

References

- Park, H.Y.; Kim, T.H.; Yoon, J.S.; Ko, J. Quantitative assessment of increase in orbital volume after orbital floor fracture reconstruction using a bioabsorbable implant. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2022, 260, 3027–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, K.Y.; Fujioka, J.K.; Daigle, P.; Tran, S.D. The Use of Functional Biomaterials in Aesthetic and Functional Restoration in Orbital Surgery. J Funct Biomater. 2024, 15, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Grob, S.; Yonkers, M.; Tao, J. Orbital Fracture Repair. Semin Plast Surg. 2017, 31, 31–39, Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Book Title, 3rd ed.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2008; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Carraway, J.H.; Mellow, C.G.; Mustarde, J.C. Use of cartilage graft for an orbital socket implant. Ann Plast Surg. 1990, 24, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motomura, H.; Deguchi, A.; Ataka, S.; Fujii, N.; Hatano, T.; Fujikawa, H.; Maeda, S.; Haraoka, G. A Dynamic Costal Cartilage Platform Promotes Ocular Prosthetic Excursion: Preliminary Report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021, 9, e3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Andrades, P.; Hernandez, D.; Falguera, M.I.; Millan, J.M.; Heredero, S.; Gutierrez, R.; Sánchez-Aniceto, G. Degrees of tolerance in post-traumatic orbital volume correction: the role of prefabricated mesh. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009, 2404–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birgfeld, C.; Gruss, J. The importance of accurate, early bony reconstruction in orbital injuries with globe loss. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2011, 4, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ataullah, S.; Whitehouse, R.W.; Stelmach, M.; Shah, S.; Leatherbarrow, B. Missed orbital wall blow-out fracture as a cause of post-enucleation socket syndrome. Eye (Lond). 1999, 13 Pt 4, 541–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, P.A.; Shore, J.W.; Yaremchuk, M.J. Complex orbital fracture repair using rigid fixation of the internal orbital skeleton. Ophthalmology. 1992, 99, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).