Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and Isolation of Xylanolytic Fungi

2.2. Sampling and Processing of Agricultural Residue as Enzyme Substrate

2.3. Screening of Xylanase Producing Fungi

2.3.1. Qualitative Assay

2.3.2. Quantitative Analysis of Xylanase Activity (Enzyme Assays)

2.4. Mutagenesis of Fungal Strains for Xylanase Enhancement

2.5. Screening of Fungal Mutant Strains

2.7. Enzyme Production Under Fermentation Conditions

2.7.1. Effect of Carbon Sources on Xylanase Production in Wild and Mutant Fungal Strains

2.7.2. Effect of pH on Xylanase Production in Wild and Mutant Fungal Strains

2.7.3. Effect of Temperature on Xylanase Production in Wild and Mutant Fungal Strains

2.7.4. Effect of Incubation Time on Xylanase Production in Wild and Mutant Fungal Strains

2.8. Isolation of Genomic DNA and from Wild and Mutant Fungal Strains

2.8.1. Amplification of 18S rRNA Gene

2.8.2. Sequencing of Fungal Strains

2.9. Amplification of Xylanase Gene in Wild and Mutant Fungal Strain

2.9.1. Sequencing of Amplified Gene

3. Results

3.1. Sampling of Natural Sources for Xylanolytic Fungi

3.2. Isolation and Purification of Fungal Species

| Sr. No. |

Sample no. | Colony morphology | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colony colour | Colony size | Colony elevation | Colony margin | Colony surface | Colony form | ||

| 1. | ZGCL01 | Green | Small | Flat | Undulate | Smooth | Irregular |

| 2. | ZGCL09 | Green | Small | Sharp | Entire | Smooth | Regular |

| 3. | ZGCL23 | Green | Small | Raised | White filiform | Rough | Irregular |

| 4. | ZGCL05 | Green | Small | Raised | White filiform | Rough | Irregular |

| 5. | ZGCL06 | Dark green | Big | Flat | Undulate | Smooth | Irregular |

| 6. | ZGCL27 | Black | Big | Raised | Filiform | Rough | Filamentous |

| 7. | ZGCL49 | Black | Small | Raised | Entire | Rough | Irregular |

| 8. | ZGCL09 | Dark green | medium | Raised | Filiform | Rough | Filamentous |

| 9. | ZGCL18 | White, green | Small | Raised | Entire | Smooth | Circular |

| 10. | ZGCL47 | Green | Small | Flat | Entire | Smooth | Circular |

| 11. | ZGCL14 | White, green | Medium | Flat | Filiform | Smooth | Circular |

| 12. | ZGCL44 | White | Large | Flat | Undulate | Smooth | Irregular |

| 13. | ZGCL51 | Green | Small | Raised | White entire margin | Smooth | Circular |

| 14. | ZGCL18 | White | Big | Flat | Undulate | Smooth | Irregular |

| 15. | ZGCL19 | Light green | Medium | Raised | Filiform | Rough | Circular |

| 16. | ZGCL12 | Green | Small | Flat | Undulate | Smooth | Circular |

3.3. Screening of Xylanase Producing Fungi

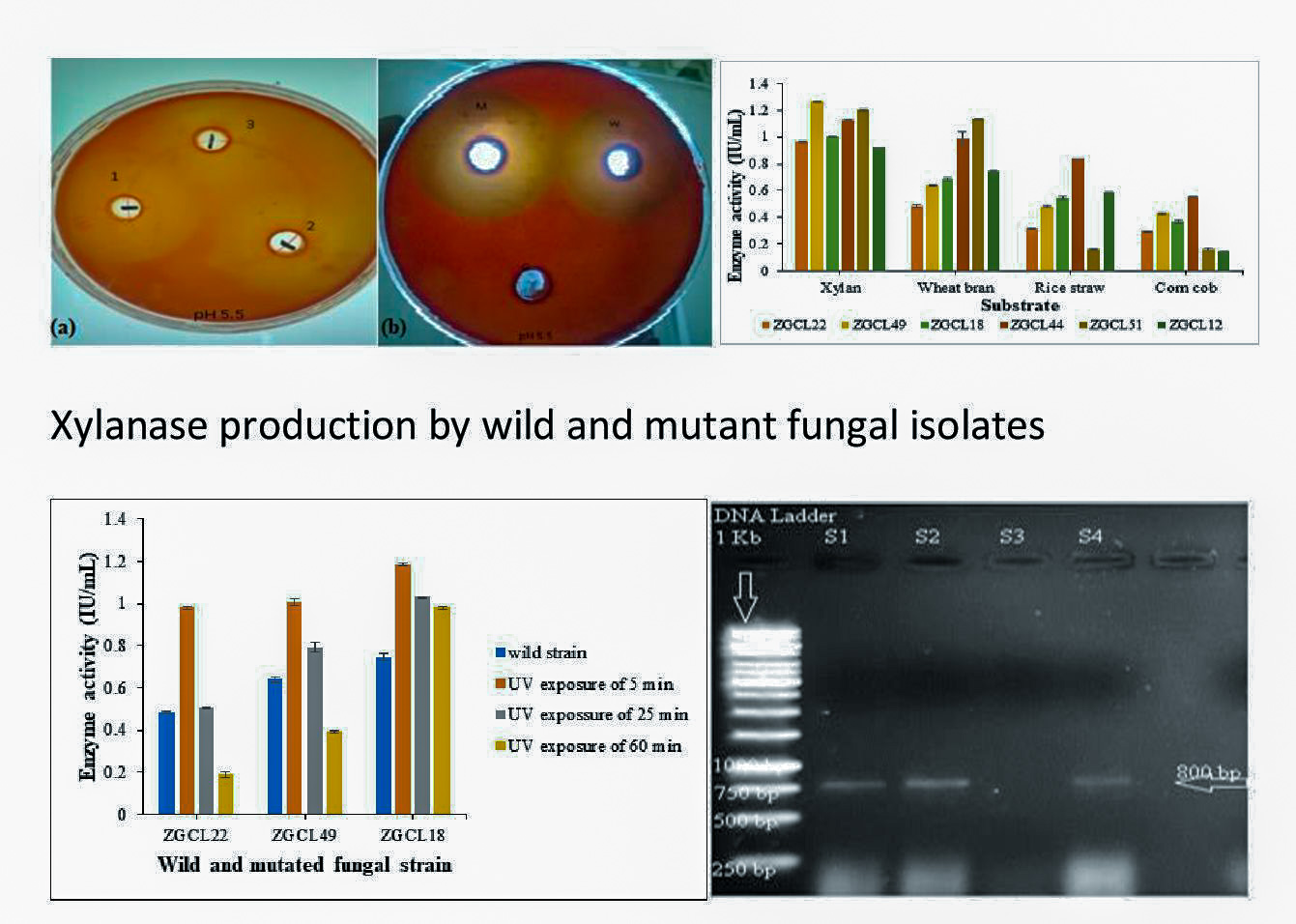

3.3.1. Qualitative Assay

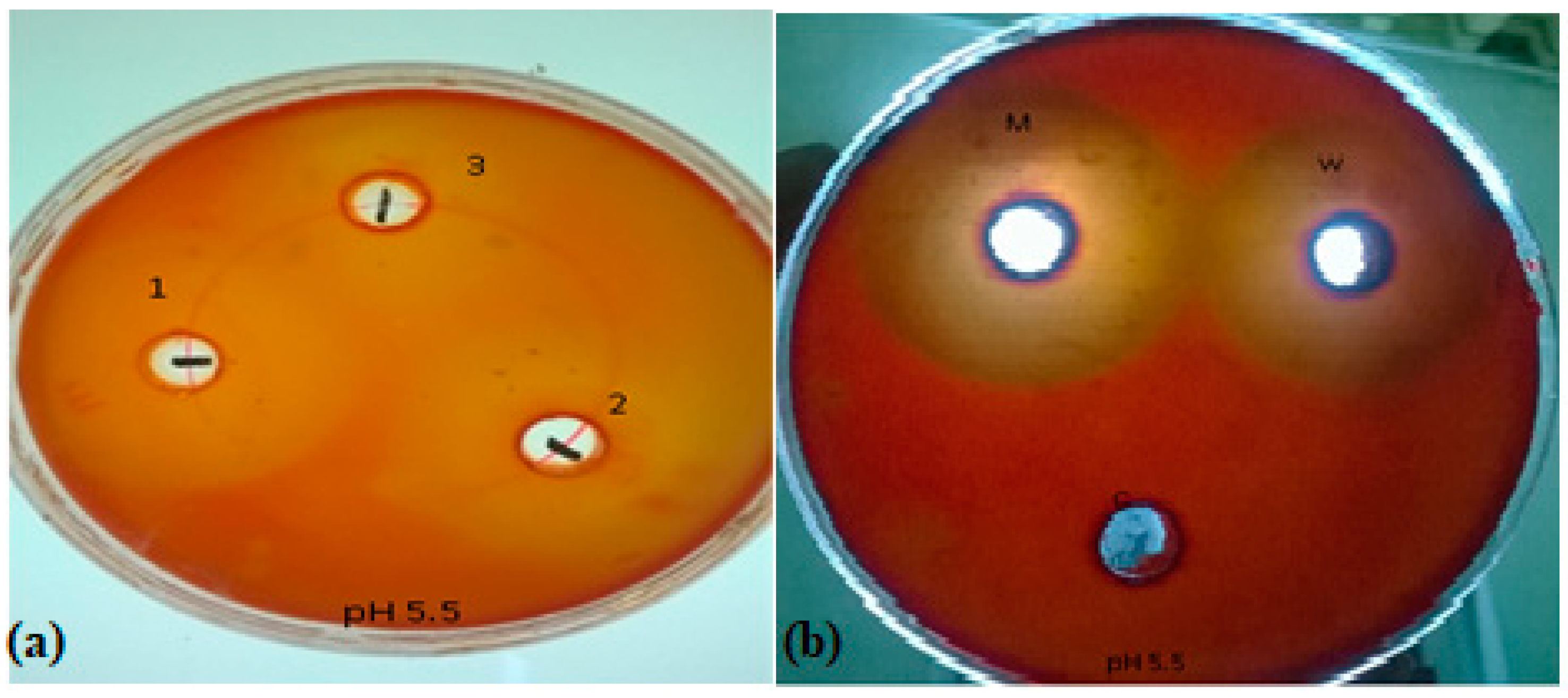

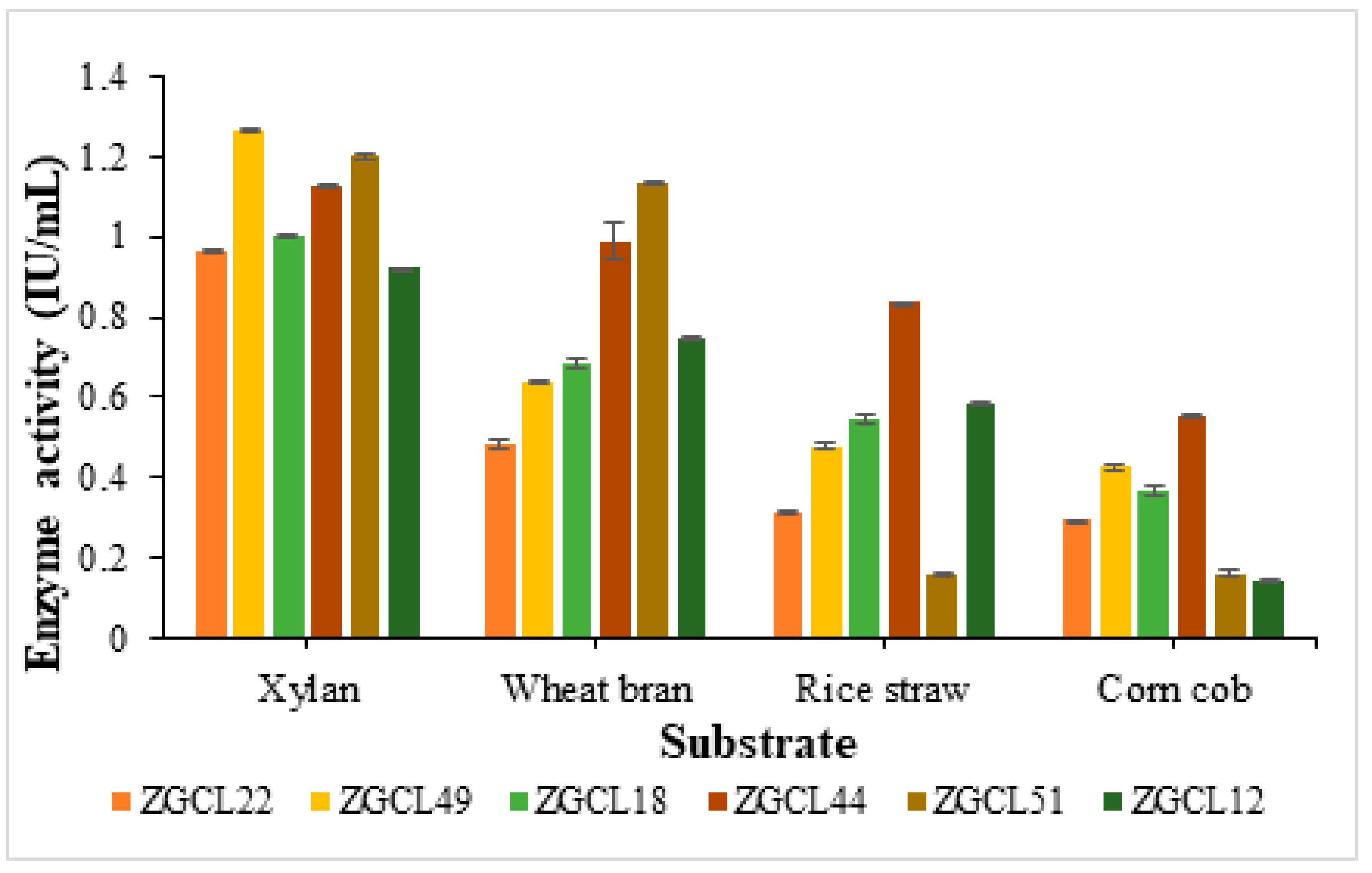

3.3.2. Quantitative Enzyme Assays of Xylanase Activity

3.4. Mutation of the Xylanase Producing Fungal Strains

3.5. Screening of Fungal Mutant Strains

3.5.1. Qualitative Assay

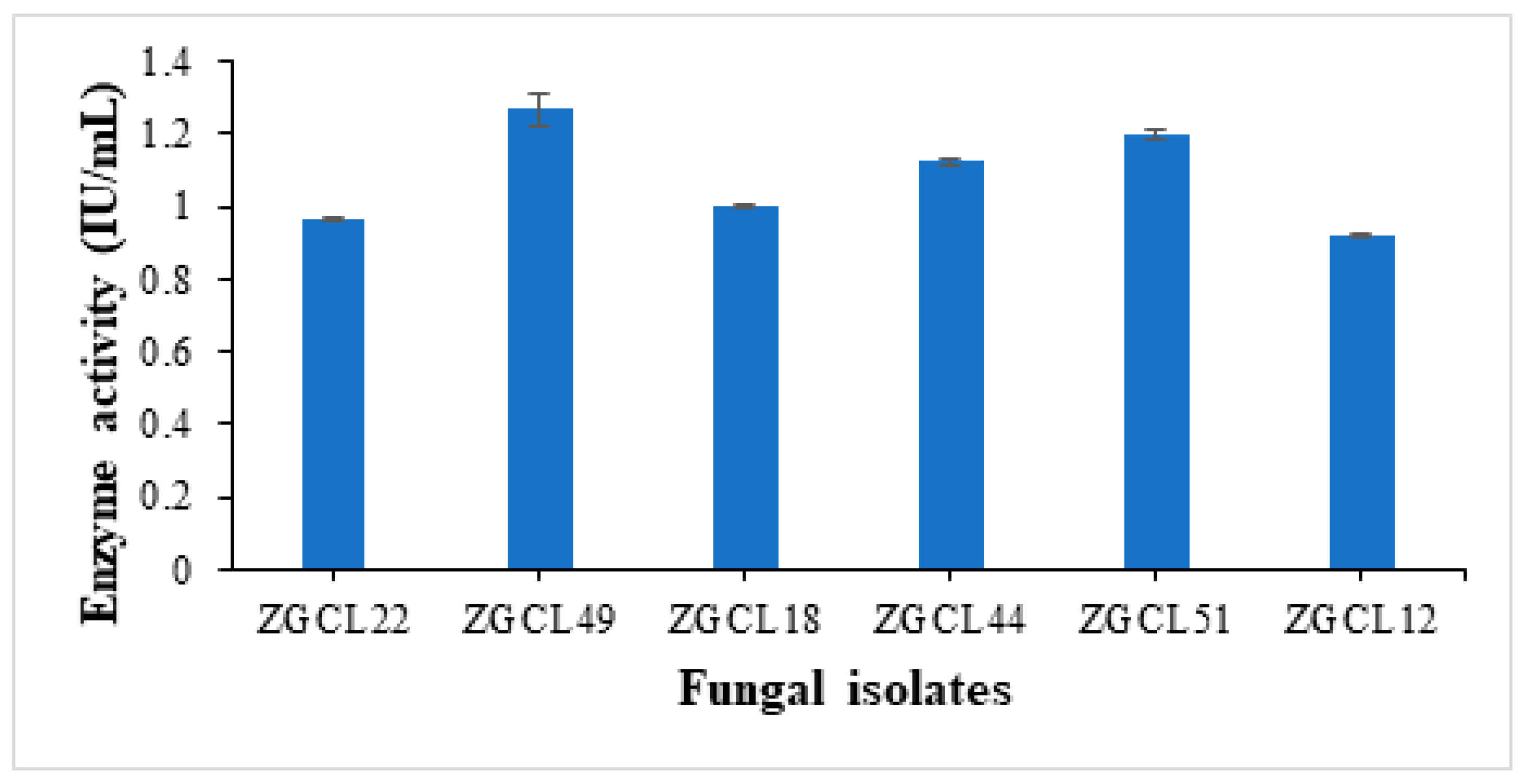

3.5.2. Quantitative Assay

3.6. Enzyme Production Under Fermentation Conditions

3.6.1. Optimization of Carbon Source for Enhanced Xylanase Production

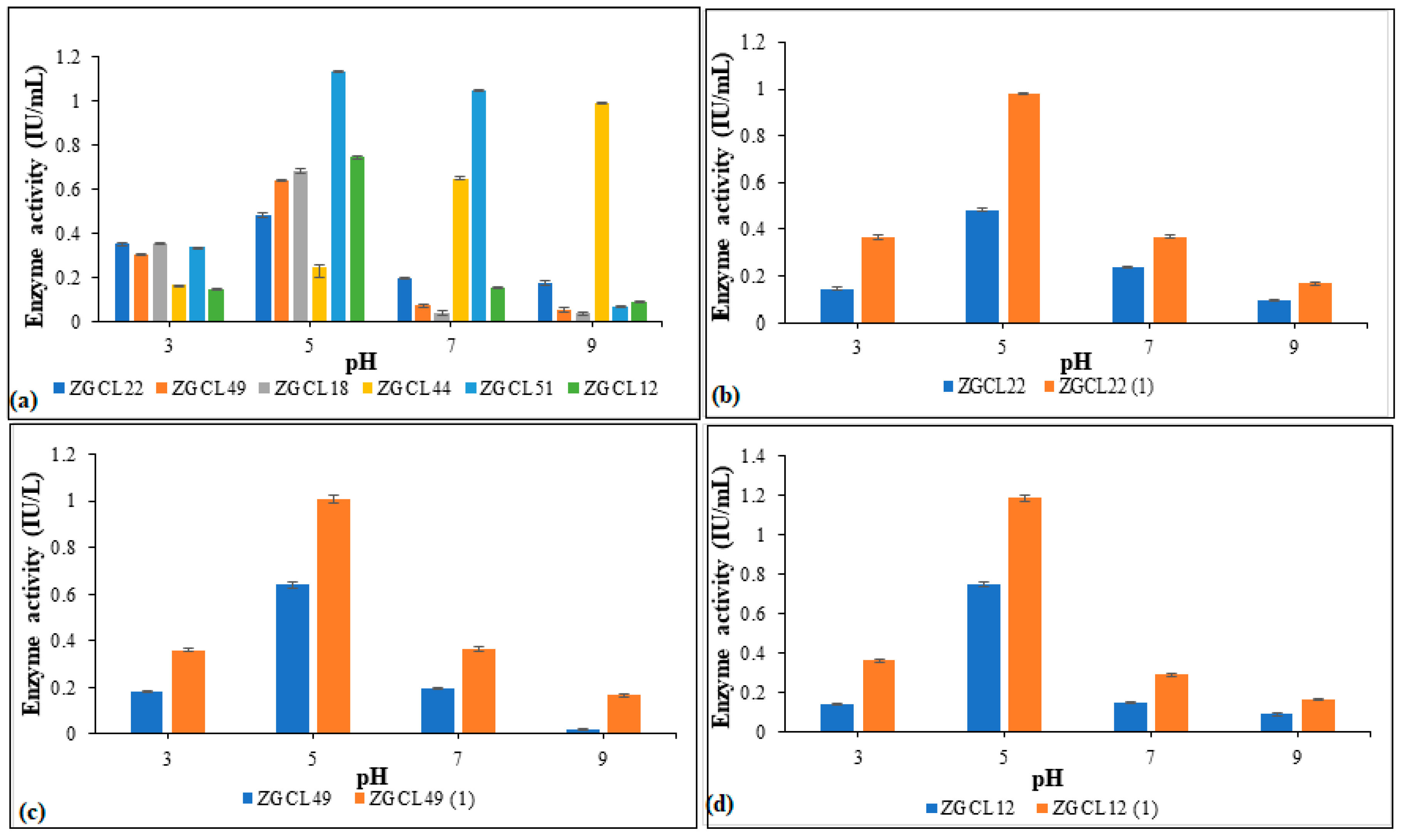

3.6.2. Effect of Different pH on Xylanase Production

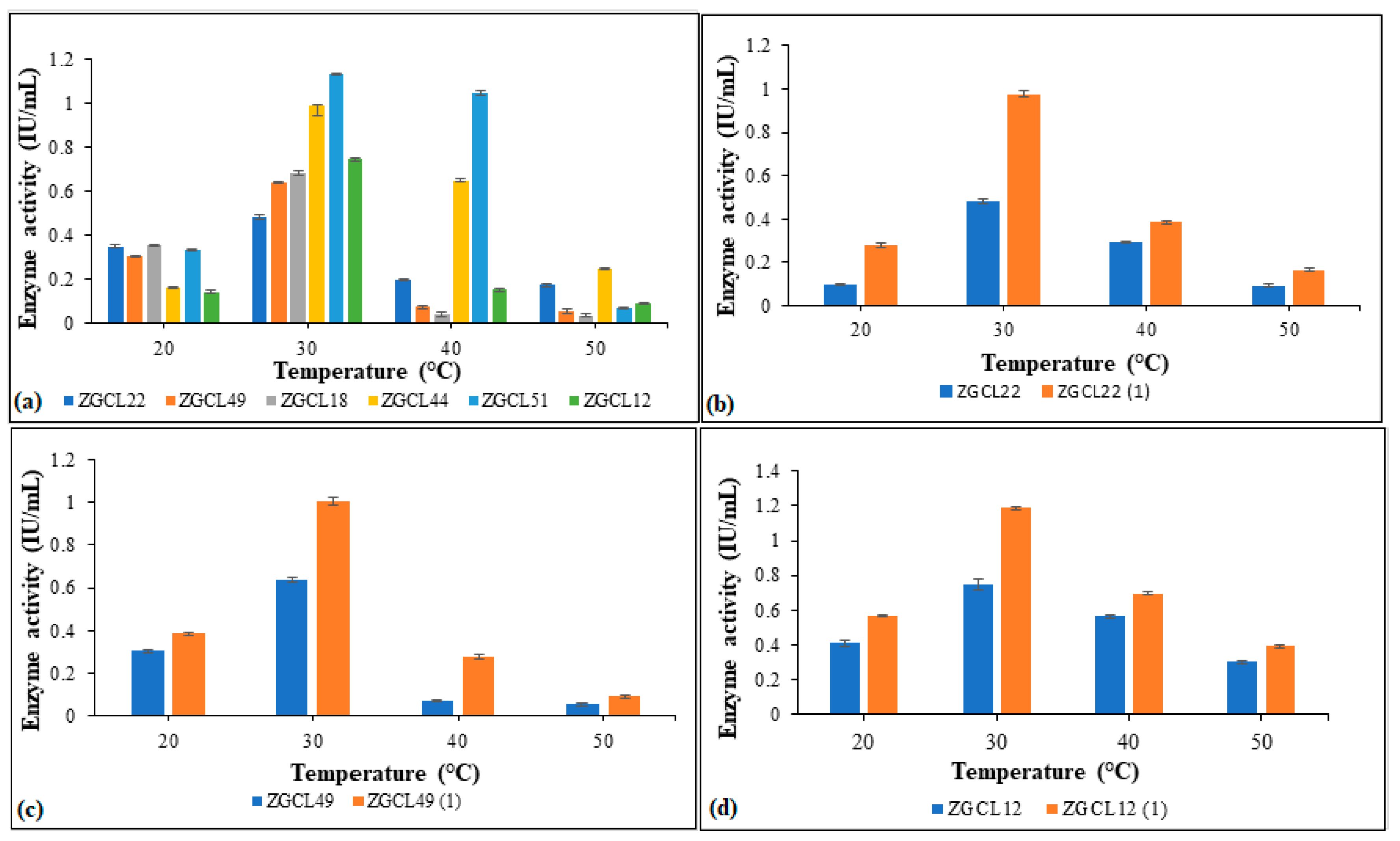

3.6.3. Temperature

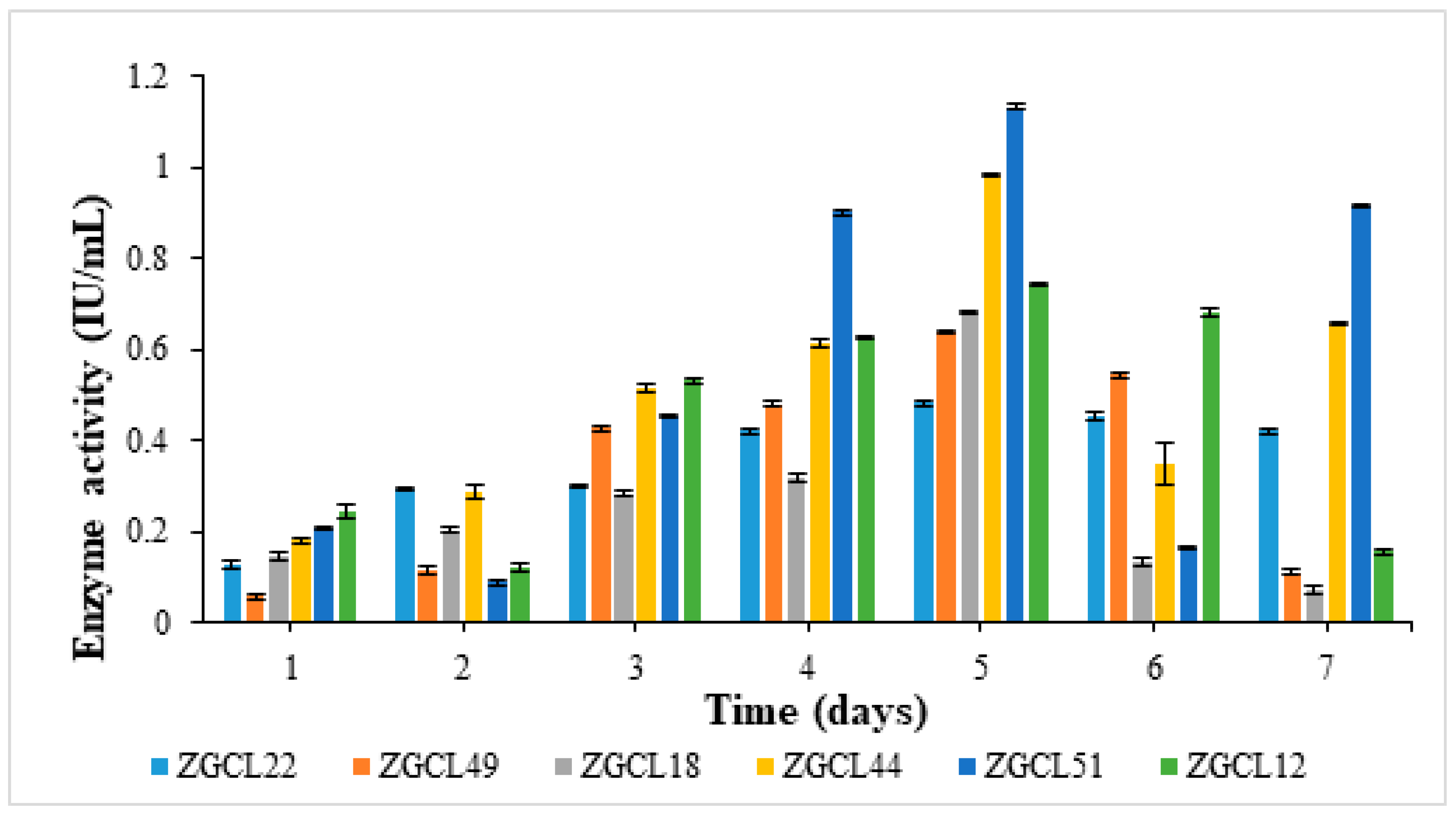

3.6.4. Incubation Time

3.7. Sequencing of Fungal Strains

| Sr. # | Isolates | Strain | Homology with | Percentage (%) | Accession number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | ZGCL22 | Aspergillus niger | Aspergillus niger isolate SUMS0061 FJ011541.1 | 100 | KT964482 |

| 2. | ZGCL49 | Aspergillus flavus | Aspergillus flavus strain 176.1B2 KP784374.1 | 99 | KT964481 |

| 3. | ZGCL18 | Fusarium oxysporum | Fusarium oxysporum isolate FoxySIN8 KJ466113.1 | 100 | KT964484 |

| 4. | ZGCL44 | Pencillium digitatum | Pencillium digitatum, strain FRr 1313 AY373910.1 | 100 | KT964483 |

| 5. | ZGCL51 | Trichoderma harzonium | Trichoderma harzonium strain HEND AF055216.1 | 100 | KT964485 |

| 6. | ZGCL12 | Aspergillus oryzae | Aspergillus oryzae NRRL 506. (AF459735.1 | 100 | KT964480 |

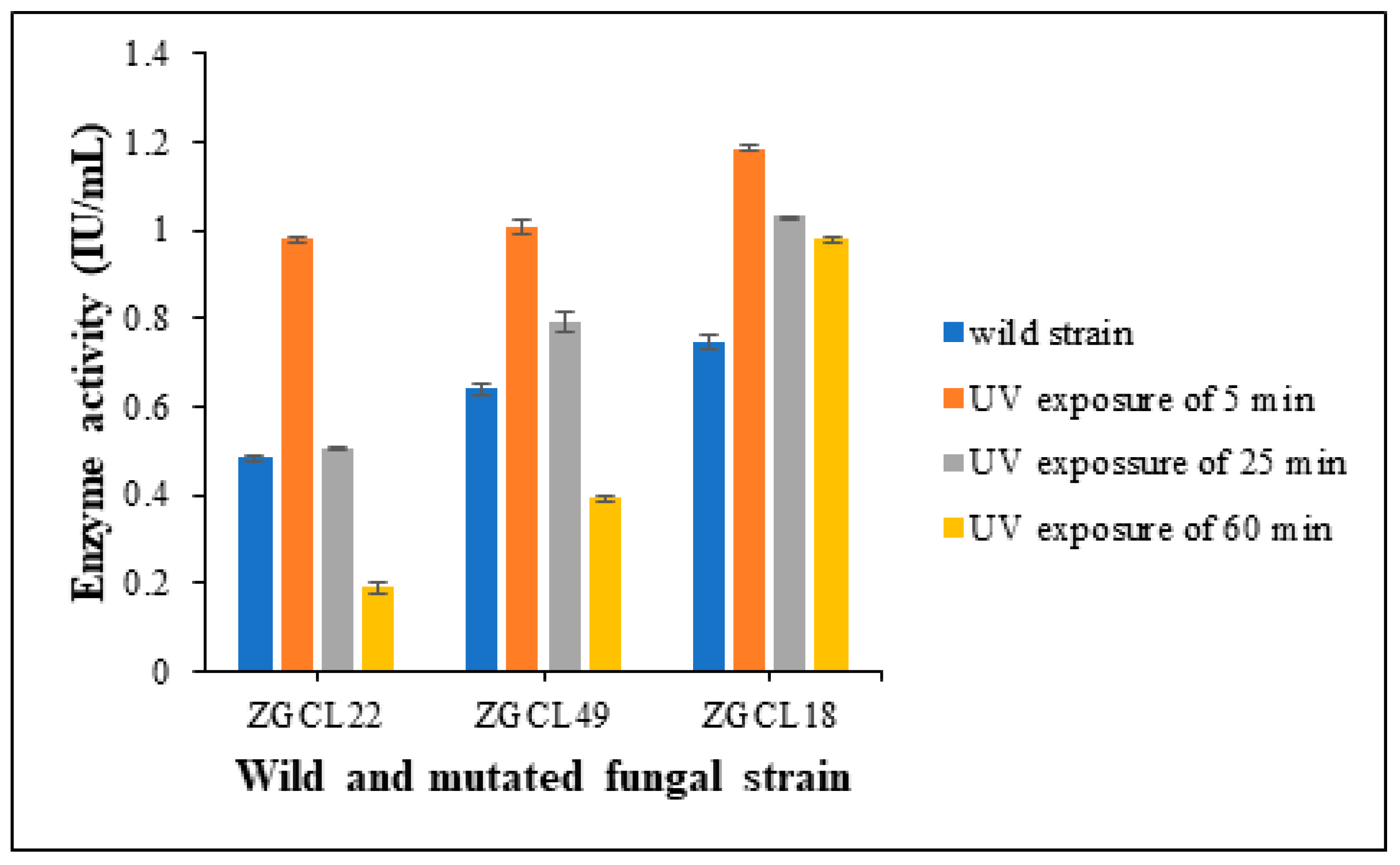

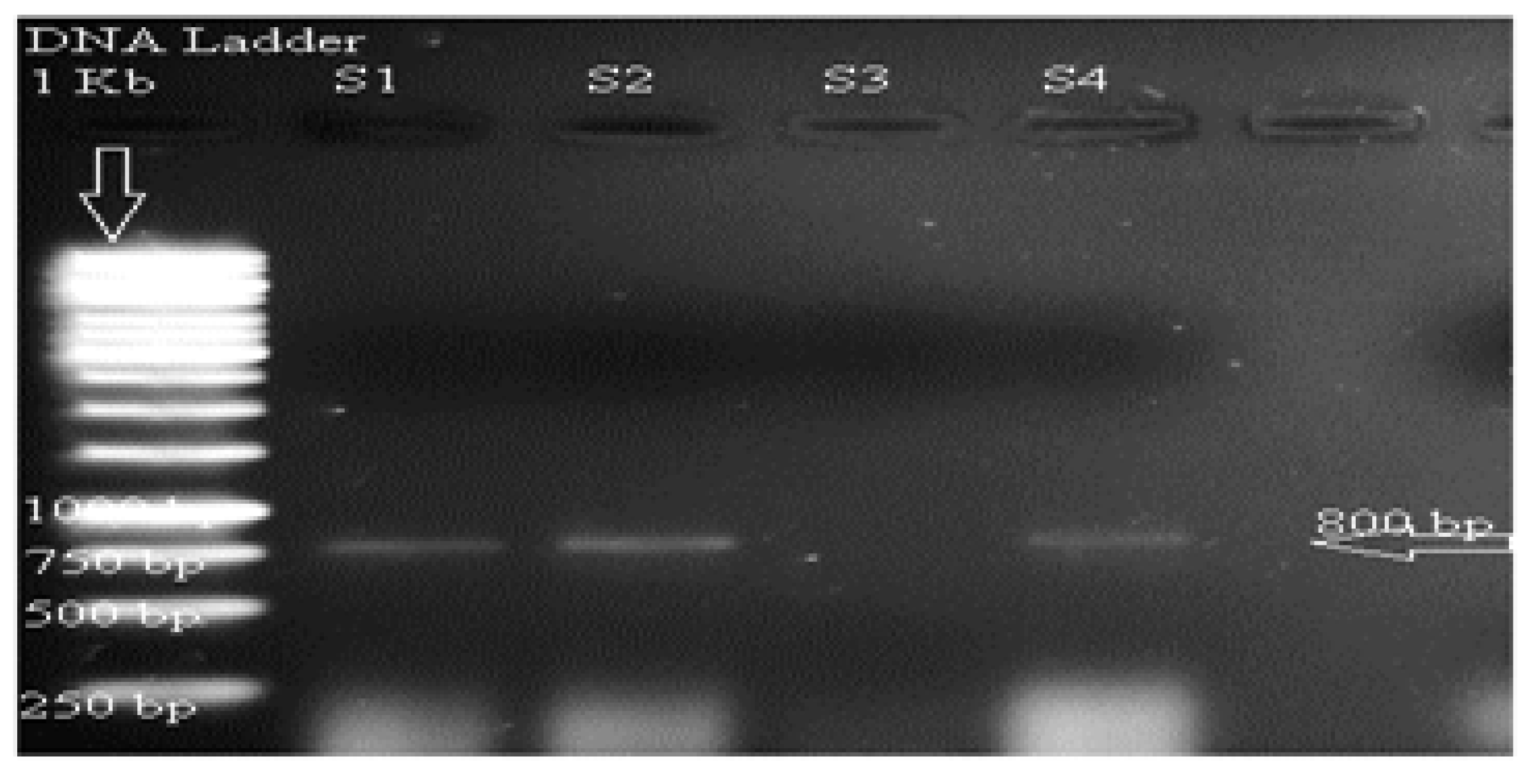

3.8. Characterization of Xylanase Gene in Wild and Mutant Fungal Strain

3.8.1. Sequencing of Amplified Gene

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

References

- Palaniappan, A.; Mapengo, C.R.; Emmambux, M.N. Properties of water-soluble xylan from different agricultural by-products and their production of xylooligosaccharides. Starch-Stärke. 2023, 75, 2200122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santibáñez, L.; Henríquez, C.; Corro-Tejeda, R.; Bernal, S.; Armijo, B.; Salazar, O. Xylooligosaccharides from lignocellulosic biomass: A comprehensive review. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2021, 251, 117118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, P.; Thakur, M.; Tondan, D.; Bamrah, G.K.; Misra, S.; Kumar, P.; Kulshrestha, S. Nanomaterial conjugated lignocellulosic waste: cost-effective production of sustainable bioenergy using enzymes. Biotech. 2021, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, G.K.; Dixit, M.; Kapoor, R.K.; Shukla, P. Xylanolytic enzymes in pulp and paper industry: new technologies and perspectives. Molecular biotechnology. 2022, 64, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Verma, P. A critical review on environmental risk and toxic hazards of refractory pollutants discharged in chlorolignin waste of pulp and paper mills and their remediation approaches for environmental safety. Environmental Research. 2023, 116728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moita, V.H.C.; Kim, S.W. Nutritional and functional roles of phytase and xylanase enhancing the intestinal health and growth of nursery pigs and broiler chickens. Animals. 2022, 12, 3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, F.; Özçelik, F. Screening of xylanase producing Bacillus species and optimization of xylanase process parameters in submerged fermentation. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology. 2023, 51, 102801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mousa, A.A.; Abo-Dahab, N.F.; Hassane, A.M.; Gomaa, A.E.R.F.; Aljuriss, J.A.; Dahmash, N.D. Harnessing Mucor spp. for Xylanase Production: Statistical Optimization in Submerged Fermentation Using Agro-Industrial Wastes. BioMed Research International. 2022, 2022, 3816010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuchová, K.; Fehér, C.; Ravn, J.L.; Bedő, S.; Biely, P.; Geijer, C. Cellulose-and xylan-degrading yeasts: Enzymes, applications and biotechnological potential. Biotechnology Advances. 2022, 59, 107981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumari, S.; Dindhoria, K.; Manyapu, V.; Kumar, R. Efficient utilization and bioprocessing of agro-industrial waste. In Sustainable agriculture reviews 56: Bioconversion of food and agricultural waste into value-added materials. 2022, (pp. 1–37). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Dhaver, P.; Pletschke, B.; Sithole, B.; Govinden, R. Isolation, screening, preliminary optimisation and characterisation of thermostable xylanase production under submerged fermentation by fungi in Durban, South Africa. Mycology. 2022, 13, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, F.M.; Dar, P.M. Fungal xylanases for different industrial applications. Industrially Important Fungi for Sustainable Development: Bioprospecting for Biomolecules 2021, 2, 515–539. [Google Scholar]

- Ellatif, S.A.; Abdel Razik, E.S.; Al-Surhanee, A.A.; Al-Sarraj, F.; Daigham, G.E.; Mahfouz, A.Y. Enhanced production, cloning, and expression of a xylanase gene from endophytic fungal strain Trichoderma harzianum kj831197. 1: unveiling the in vitro anti-fungal activity against phytopathogenic fungi. Journal of Fungi. 2022, 8, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saroj, P.P.M.; Narasimhulu, K. Biochemical characterization of thermostable carboxymethyl cellulase and β-glucosidase from Aspergillus fumigatus JCM 10253. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 2022, 194, 2503–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohail, M.; Barzkar, N.; Michaud, P.; Tamadoni Jahromi, S.; Babich, O.; Sukhikh, S.; Nahavandi, R. Cellulolytic and xylanolytic enzymes from yeasts: Properties and industrial applications. Molecules. 2022, 27, 3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbu, V.M.; Gheorghe-Barbu, I.; Dumbravă, A.Ș.; Vrâncianu, C.O.; Șesan, T.E. Current insights in fungal importance—a comprehensive review. Microorganisms. 2023, 11, 1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovão, M.; Schüler, L.M.; Machado, A.; Bombo, G.; Navalho, S.; Barros, A.; Varela, J. Random mutagenesis as a promising tool for microalgal strain improvement towards industrial production. Marine drugs. 2022, 20, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, H.; Singh, S.; Sinha, R. Fermentation Technology for Microbial Products and Their Process Optimization. In Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology: A New Horizon of the Microbial World. 2024, 35-64. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Banoon, S.R.; Salih, T.S.; Ghasemian, A. Genetic mutations and major human disorders: A review. Egyptian Journal of Chemistry. 2022, 65, 571–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, C.; Arock, M.; Valent, P. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors for the treatment of indolent systemic mastocytosis: are we there yet? Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2022, 149, 1912–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, R.; Pennacchio, A.; Vandenberghe, L.P.D.S.; De Chiaro, A.; Birolo, L.; Soccol, C.R.; Faraco, V. Screening of fungal strains for cellulolytic and xylanolytic activities production and evaluation of brewers’ spent grain as substrate for enzyme production by selected fungi. Energies. 2021, 14, 4443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmelová, D.; Legerská, B.; Kunstová, J.; Ondrejovič, M.; Miertuš, S. The production of laccases by white-rot fungi under solid-state fermentation conditions. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2022, 38, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellaouchi, R.; Abouloifa, H.; Rokni, Y.; Hasnaoui, A.; Ghabbour, N.; Hakkou, A.; Asehraou, A. Characterization and optimization of extracellular enzymes production by Aspergillus niger strains isolated from date by-products. Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology. 2021, 19, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siwach, R.; Sharma, S.; Khan, A.A.; Kumar, A.; Agrawal, S. Optimization of xylanase production by Bacillus sp. MCC2212 under solid-state fermentation using response surface methodology. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2024, 103085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Z.; Khan, G. . PCR-Based Techniques. In Molecular Techniques for Studying Viruses: Practical Notes. 2024, 25-31. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore.

- Abena, T.; Simachew, A. A review on xylanase sources, classification, mode of action, fermentation processes, and applications as a promising biocatalyst. BioTechnologia. 2024, 105, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, P.; Kaushik, R.; Sirohi, R. Insights into recent advances in agro-waste derived xylooligosaccharides: production, purification, market, and health benefits. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Huang, B.; Liu, Y.; Sun, X.; Xiong, L.; Zhu, T.; Liu, H. Characterization of a novel cold-active β-Xylosidase from Parabacteroides distasonis and its synergistic hydrolysis of beechwood xylan. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2025, 284, 137895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).