1. Introduction

Agriculture is a strategic sector for many African countries. In addition to its crucial role in supporting local economies, this sector also ensures food production, thus helping to solve food security problems. While the sustainability of this agriculture has long been a crucial issue for policy-makers and the scientific community, it is now time to critically examine the economic viability and sustainability of farms, by gauging the capacity of family farming to bear the burdens of production. The aim is to establish effective pricing systems that adequately support farmers' incomes.

From an economic point of view, a farm is viable when the annual cash income generated is sufficient to cover operating costs [

1]. Similarly, [

2] argue that the sustainability of agriculture must be considered from the point of view of economic sustainability, implying that income must be covered by expenses. This calls for a reconsideration of the content of production costs in order to ensure a more adequate evaluation of farms.

In most African countries, production is mainly handled by the family. A large proportion of production costs, relating to the work of family members and constituting opportunity costs, do not always appear in farm financial statements. What's more, most studies in rural areas struggle to collect information on these costs. Indeed, [

3] has already pointed out the difficulties involved in estimating the cost of family labor, for both economists and statisticians. He argued that farm accounts that do not take opportunity costs into account remain incomplete. In the specific context of cocoa farming in Ivory Coast, [

4] also stressed the failure of conventional economic calculations to take into account the costs associated with the use of FL and the amortization of invested capital. Contrary to a purely accounting view, economists must take into account opportunity costs, such as the cost of family labor (FLC) and the cost of using farm-specific production factors, in economic evaluations.

Opportunity costs are implicit costs that are not directly reflected in financial statements, but must be taken into account when calculating them [

5]. For a producer, the opportunity cost is defined as the wage he foregoes by using his labor power on his own farm rather than selling it to other producers [

7]. In this sense, [

6] argues that it is the measure of the cost of lost opportunities, or simply the opportunity cost. From the business owner's point of view, opportunity costs represent the lost benefits of the best alternative capital allocation to the one currently used [

5]. Furthermore, opportunity costs remain important for establishing certain performance indicators such as average FL productivity [

8]. To this end, an analysis of the profitability of family farms must necessarily take into account the opportunity FLC [

9]. This raises the need to develop tools to better assess the family labor force in order to more adequately determine the costs incurred.

In Ivory Coast, cocoa production is characterized by a constant movement of farmers in search of fertile land. This movement is mainly due to the ageing of cocoa orchards and the impoverishment of soils, requiring additional investment to maintain production in formerly cultivated areas [

24]. To optimize production, growers are turning to land that is still intact [25; 24, 26]. This phenomenon has led, particularly in the 2000s, to the migration of farmers to the savannah zones and high mountains in the west of the country to grow cocoa [

27]. While this move enables farmers to take advantage of forest rents to increase yields [

24], it does not guarantee a reduction in costs or in the drudgery of work. Production costs can vary considerably from one locality to another due to geographical specificities.

Moreover, agroforestry, which combines agriculture and forestry, is now widely promoted in cocoa farming as an innovative solution combining sustainability and productivity [

28]. However, little is known about the costs associated with this technique. Indeed, the high set-up costs of agroforestry systems sometimes raise doubts about their profitability. In addition, [

29] points out that agroforestry is more labor-intensive, which can lead to higher production costs in these systems. On the other hand, it is often argued that with very high initial costs, agroforestry systems can only be profitable in the long term due to the diversification of income sources [

30]. To ensure their short-term viability, these systems should be accompanied by compensatory measures. However, the Ivorian government's system for setting cocoa prices does not take into account geographical constraints or specific farming practices.

In the cocoa sector, numerous initiatives have been launched in recent years to determine a fairer income for Ivorian cocoa farmers. These include the Living Income initiative, supported by GIZ, which brings together players from the private sector, certification bodies, representatives of civil society, governments and numerous technical experts in economic sustainability. The shared ambition of these initiatives is to improve the incomes of small-scale producers, enabling them to achieve a decent standard of living. Decent income being defined as a level of income enabling producers and their households to cover their essential needs: food, housing, education, health, transport, clothing and to have a safety margin for possible unforeseen events [

40]. Three methods for assessing the decent income threshold (or benchmark) exist to date, namely: the Anker method, the Wageningen method (WUR), which is an adaptation of the Anker method, and finally the HEA method used to calculate an alternative threshold. On this subject, a study carried out by CIRES in 2018 among Ivorian cocoa farmers using the Anker method sets the decent income threshold at 262056 CFA. This implies that for a cocoa-growing household to live decently, it needs at least 262056 CFA per month [

40]. This threshold makes it possible to determine the gap between real income and decent income, with a view to implementing measures to close the gap. However, it has to be said that most studies of income estimates tend to favour an accounting approach, taking into account only the financial costs borne by producers, and neglecting the costs borne by members of the farmer's family. Estimating income in this way could lead to biased gaps between real and decent income, leading to potentially inappropriate measures. This article argues that before seeking to reduce the gap between real and decent income, it is first necessary to adequately estimate the production costs actually borne by farmers.

The rest of the article presents the literature review, the methodology, the results and their discussion, followed by the conclusion.

2. Literature Review

The concept of opportunity cost has largely dominated economic thought over the years, and was a key element of general equilibrium theory [

6]. It is considered an essential analytical tool, usable by all economic theories. Several studies have examined its measurement in various fields. [

10] evaluated the opportunity cost of carbon sequestration on tropical farms. Their conclusion is that it is less expensive to sequester carbon via agroforestry systems than via purely tree-based systems. Thus, opting for an agroforestry system would represent the best alternative in terms of carbon sequestration. Even in the context of environmental conservation, it is crucial to take opportunity costs into account when making optimal choices. For example, [

11] have examined the opportunity costs of conservation. Their approach is based on a comparison of conservation costs with market-driven land-use benefits. [

12] point out that there is sometimes a dilemma between conservation and land use. Their study assesses the opportunity costs of conserving the Kakamega forest in western Kenya. They conclude that conservation is the best alternative, as exploiting the forest can have detrimental consequences for future generations, both locally and globally. To achieve such an option, the authors recognize that understanding the local opportunity costs associated with restricting access to forest land and resources for conservation is crucial to developing cost-effective conservation programs that reduce negative impacts on poor forest-dependent populations.

In another study, [

13] examined the relationship between agricultural labor and migration to estimate the opportunity costs of agricultural labor. They observed a significant gap between the annual income of farmers and that of migrant workers, resulting in a continuing loss of rural population. Thus, the opportunity cost of farm income is equivalent to the income of migrant workers in some cases. [

14] showed that off-farm household income in Ningxia, China, accounted for over 60% of the total, reaching 79.4% in 2007. So the most accurate way for them to estimate the opportunity cost of farm labor is to use the maximum off-farm income. On the other hand, [

15] analyze the economic performance of dairy sheep farms in Spain. In their work a monthly wage of €1,000 was used to reward family labor and an interest rate of 4% for invested capital. They conclude that when opportunity costs are taken into account, the prices received did not cover costs, and 60% of the dairy farms studied made losses. In light of this, [

9] argues that farmers should capitalize on their own resources, such as land, labor and capital. By highlighting the potential results of allocating these resources to alternative uses, they could resort to resources with the lowest opportunity costs. In a study carried out on rubber, oil palm and sugarcane cultivation, [

16] use the salary of a night watchman in town of around 500 000 FCFA to estimate the opportunity cost of the labor force of one family asset per year. Similarly, [

17] use industrial wages to estimate the opportunity cost of family labor. As for the opportunity cost of land, they use regional rental and sale prices.

Opportunity costs can vary according to circumstances and geographical location. It is in this sense that [

43] argue that the estimation of opportunity costs should necessarily account for spatial variations. For farms far from urban areas, there are fewer opportunities for alternative off-farm employment. This limits the options available to farmers in these areas, reducing their opportunity costs compared with those located near major conurbations, who benefit more from off-farm employment opportunities. This complexity underlines the need for researchers to take into account the specificities of each situation. Nevertheless, three approaches to estimating opportunity costs have been proposed by [

5] to guide future farm research. These approaches include firstly the estimation of the opportunity cost of the farmer's labor, which offers two alternatives. The first assumes that the second-best alternative for farmers or family members is to work as employees in agriculture, enabling them to monetize their labor power with other farmers rather than on their own farm. The second option assumes that the second-best alternative for the farmer or family member is to be employed in other industries due to the relatively low incomes in agriculture. In this case, the opportunity cost is estimated by the average hourly cost of labor in these industries. Next, the opportunity cost of equity is estimated from the point of view of an investor who could have invested his capital in other investments to benefit from the interest. Finally, we estimate the opportunity cost of land, which considers the alternative benefits of land use for the farmer. Since the farmer is the owner of the land, he has the option of using his land for agricultural production or using it in some other way, such as renting or selling. [

2] also propose three approaches very similar to those of [

5]. According to the authors, the opportunity cost of land is obtained by multiplying the amount of land in hectare by the amount of rent in the region. Next, the opportunity cost of unpaid labor is determined by multiplying the unpaid labor input by the average agricultural wage in the region. Finally, the opportunity cost of capital is obtained by multiplying it by the interest rate. Their approach respects [

3] criterion that, in order to estimate the opportunity FLC, the economist should first carry out a sound analysis of the quantity of FL and its cost components.

Rather than considering a holistic dimension, some authors such as [

18] reduce production costs to the actual expenses borne by the producer. Conversely, [

19] argue that it is impossible to dispense with the evaluation of FL, given its importance for the implementation of certain agricultural techniques. By analyzing the opportunity cost of labor on the economic profitability of fertilizer microdosing in Burkina Faso, the authors show that this technique remains economically profitable even when these costs are taken into account. The study by [

20], based on close monitoring of 30 farms over three cropping seasons in the Central African cotton-growing zone, showed that the family's working time accounted for 58% of the working time required on the whole farm. This underscores the importance of family labor in African farming systems.

The economic literature thus shows the need to take opportunity costs into account to better estimate income in the agricultural sector. However, this review also reveals that there are fewer studies on the specific case of Ivorian cocoa farmers, which forms the basis of this investigation.

3. Methodology

The methodology begins with a description of the study area, then discusses sampling and data collection, followed by a detailed description of the survey population. It concludes with the methods used to estimate the financial and opportunity costs in this article.

3.1. Study Area

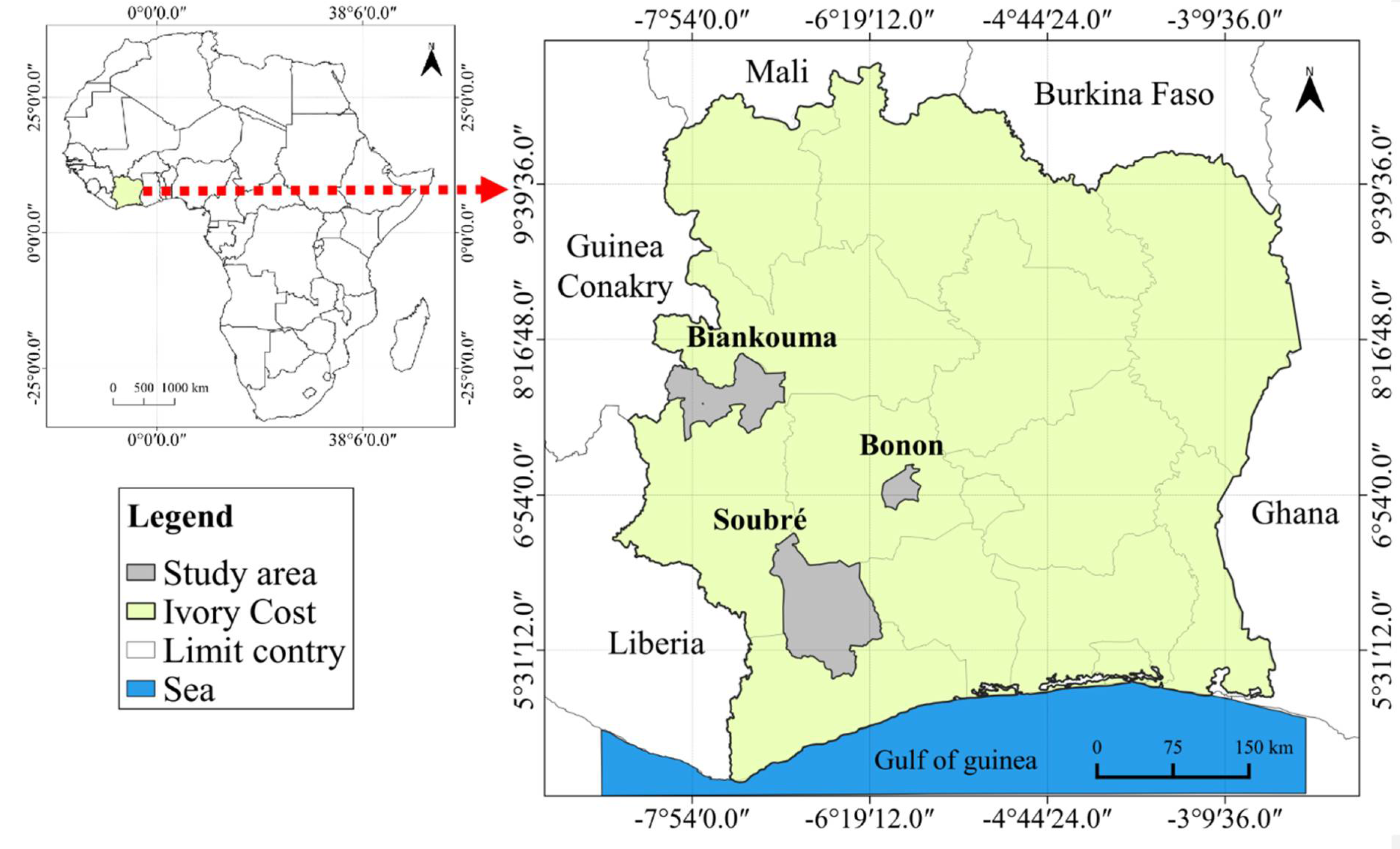

The present study was carried out in three cocoa production zones in Ivory Coast belonging to the agroforestry plot network of the Cocoa4Future project observatory

1 (

https://www.cocoa4future.org/le-projet/les-zones-d-intervention) . These sites were selected according to the East-West gradient, which corresponds to the evolution of the main cocoa production zones in Ivory Coast [

31]. These sites are located in Bonon in the centre-west, Soubré in the south-west and Biankouma in the west. The Bonon site represents the epicenter of the second cocoa production zone, which saw strong production in the 1990s. The Soubré site is representative of the current cocoa production zone par excellence. Finally, the Biankouma site in the west of the country is considered to be the future major cocoa production zone [27, 31]. This site has seen strong growth in cocoa production since 2010.

Figure 1.

Map of study area.

Figure 1.

Map of study area.

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

One hundred and fifty (150) cocoa farms were randomly sampled on the three sites, i.e. 50 farms per site. In the interest of observing certain farming practices, 78 additional farmers were selected, including 25 in Bonon, 25 in Soubré and 28 in Biankouma. The choice of these additional farmers was made on a reasoned basis with the help of the guides and project technicians. The data collection tool was a questionnaire addressed essentially to the farm manager. In practice, the farmer could call on his wife or any other family member to answer questions for which he had no answer or information. The questionnaire focused on cocoa production and purchase prices on the one hand, and on production costs over the entire production chain, from the farm to the marketing of the cocoa bean on the other. With regard to production costs, two main items of information were identified. In order to capture financial costs, information was collected on the expenses directly incurred by farmers for each operation throughout the production chain. For social costs and family labor, the farm income method was used. In other words, it was considered that the best opportunity that the family member loses is to be hired on another farm for similar work. Information was thus collected on work times for each social category in the household (men, women and children) throughout the production chain. The daily costs attributable to these household working days were also recorded. For land, the opportunity cost represents the income that would have been earned if the land had been rented from another cocoa farmer.

3.3. Description of the Study Population

The people taken into account in the estimation of social costs are the members of the household, i.e. those who are under the responsibility of the head of the family and who do not receive remuneration for carrying out tasks on the farm. In addition, the children mentioned here are those members of the household who sometimes accompany their parents and help them with certain tasks. Thus, a child is considered to be any person living in the household and aged 15 or under. This age bracket is chosen with reference to Article 6 of the International Labor Organization, which sets the minimum age for admission to employment at 14. However, there are exceptions for light work, which can be carried out from the age of 15, subject to certain conditions and the authorization of the competent authorities.

Furthermore, access to information on child labor within farming families is becoming increasingly difficult for researchers, due to pressure from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and multinationals. When this issue is raised, producers can sometimes react with a certain reticence, giving the impression that they are hiding something. During the course of this study, it was found that growers can be wary of researchers, fearing that disclosure of sensitive information could have negative consequences for themselves or their families. So, to obtain information on this seemingly delicate aspect, it was essential to cultivate a relationship of trust with growers over time. Despite these efforts, however, some of them refused to discuss the issue, probably resulting in a loss of information about part of the family's work.

3.4. Production Cost Estimation Method

Production costs are made up of two main components: financial costs and social costs. While financial costs are easy to calculate, the same cannot be said for social costs, which have to be estimated.

Financial costs include, first and foremost, the cost of outside labor (OUL) hired under contract for one production year. In cocoa farming, certain tasks, such as shelling, are carried out through arrangements between producers. Although this work involves the use of OUL, it does not require the payment of a wage for the external persons invited. Nonetheless, carrying out this work generates higher costs, as shelling is considered a feast, and the owner must satisfy his guests with food and drink. The costs associated with this type of task have been accounted for as self-help costs, which are then included in the costs of formal contracts to make up the total cost of the OUL.

Next, the costs associated with farm inputs were accounted for. In addition, all the equipment owned by the farmers was inventoried, along with its purchase price and lifespan, in order to calculate depreciation. Finally, the last component of the financial costs concerns the cost of the OUL during the creation of the plot. For this cost, 30-year depreciation is used, as the life expectancy of a cocoa plantation is between 25 and 30 years [

45]. However, these data are not accurate, since for plantations that are more than 10 years old, the current farmers are not necessarily those who planted them in the first place. In such a situation, the regional average of these costs has been imputed to these farms.

To assess the FLC, the article adopts the opportunity cost approach. Opportunity costs in family farming are often implicit costs that are not directly measurable in monetary terms. One of the challenges is to identify all the opportunity alternatives available to farmers. This may include options such as salaried work on other farms, work in other industries, capital investment in other sectors, leasing farmland to third parties, etc. The opportunity costs associated with each option then need to be measured in order to select the best alternative. However, this can be particularly difficult in practice, due to the many non-controllable factors specific to farmers that can influence the value of alternative opportunities. Indeed, operators' level of education, experience and skill in accessing other, more advantageous opportunities can make all the difference. To simplify the calculation and ensure a more objective estimate of opportunity costs, the first approach proposed by [

5] has been adopted. This approach assumes that the second-best alternative for farmers is to work as employees in agriculture. Although this method is the simplest, it corresponds well to the minimum reward that could be attributed to family labor. The advantage of such an approach is that it avoids calculating exaggerated opportunity costs that may not reflect reality in the farmer's environment.

The process began by identifying all the tasks involved in the production chain. Then, the working times and costs associated with each task for men, women and children were determined. In practice, daily costs in the region were used as the opportunity cost. Let's consider a farm where different tasks have to be performed to ensure production. The working time for men, noted

is determined by the sum of the product of the number of men

involved in each task

i and the number of days

required to complete that task. Similarly, the working time of women and children

and children

is calculated. Thus, the working time of men is determined as follows:

This means that the total working time for a farm can be expressed as follows:

with

the working time of each social category (men, women and children). This measure, expressed in man-days (Mdr), reflects the amount of human labor invested in cocoa production.

Once the working times are known, the opportunity costs can be calculated based on the daily costs. The opportunity cost of men, denoted

is determined by the sum of the products of the daily cost of men for each task, noted

by the time spent by the men on each task, noted

. The opportunity cost of women and children is determined by the same process. Formally, this translates into :

The total opportunity cost, TCO, for each operator is the sum of the opportunity cost of men

women

and children

or :

The cost of land was assessed using the regional rental price, obtained by interviewing growers and resource persons such as the heads of growers' associations. This approach is adopted because, in the production zones, we are in the second or even third generation of producers. As a result, heirs often don't remember the cost of the land, even when it was acquired by purchase.

Once production costs have been estimated, a minimum break-even point will be determined. This involves comparing the average cost of producing one kilogram of cocoa with the average market purchase price. The aim is to identify the purchase price that will generate sufficient income to cover production costs. The cost of producing one kilogram of cocoa is calculated by dividing the total cost of production by the total quantity of cocoa produced. This break-even point represents the point at which the business becomes viable. If the purchase price falls below this threshold, producers will incur losses, making their business unsustainable in the long term. It is therefore essential that the purchase price not only equals, but ideally exceeds this cost of production, in order to guarantee a profit margin and enable producers to reinvest in their farms and maintain a decent standard of living. Profitability depends not only on covering costs, but also on the ability to generate profits that will ensure the sustainability of the cocoa sector.

5. Discussions

Our results show that men are the most active in cocoa production. Indeed, in many cocoa-growing regions, the division of labor is often based on gender. Tasks requiring physical strength, such as cleaning the cocoa fields and harvesting, are generally assigned to men [

32]. In addition, men are often the owners of the land and resources required for cocoa production, giving them a more central and active role in farming activities [

33].

Very few farmers agreed to declare the working hours of the family's children. However, in the traditional practices of African communities, it is common for children to participate in family work from an early age. This participation is often seen as a sign of learning, socialization and the transmission of skills. This reluctance to discuss child labor is due to the fact that there are strict laws against child labor, as well as mechanisms to monitor their violation. This fear of legal repression can deter them from responding honestly to inquiries on the subject. Such a situation results in the loss of valuable information on production costs, and risks slowing down the process of skills transfer, essential to the sustainability of cocoa production. Such a fact is debated in Sierra Leone on the involvement of children in gold and diamond mining [

34]. According to these authors, unreserved acceptance of international child labor laws could have negative implications for children and, by extension, for the communities to which they belong.

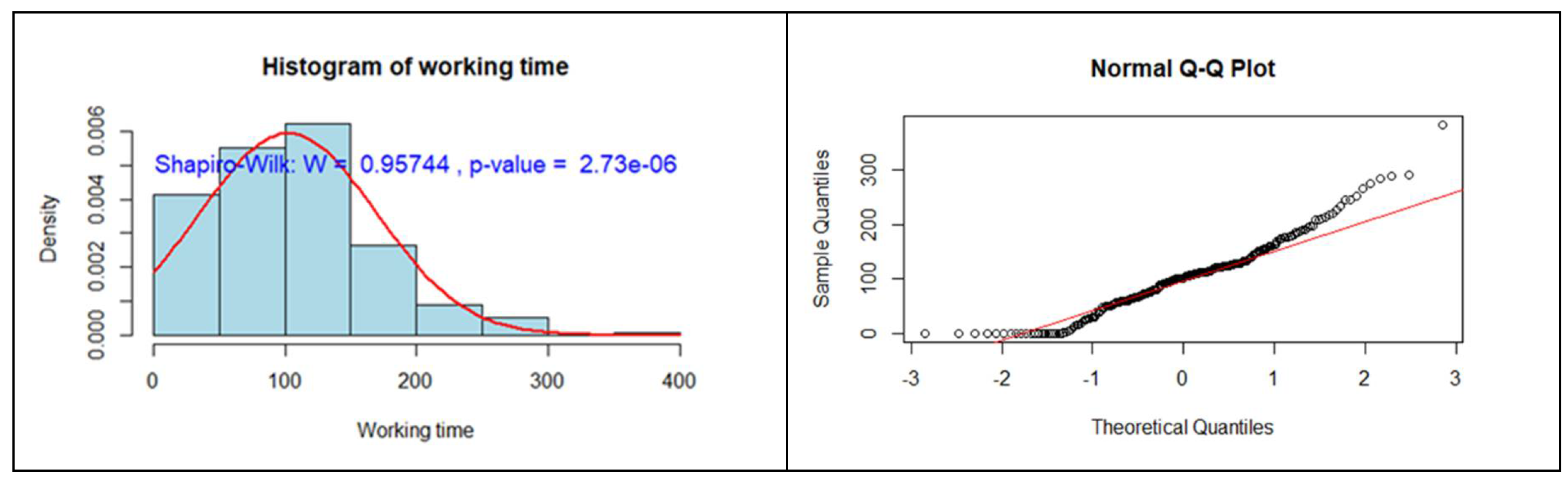

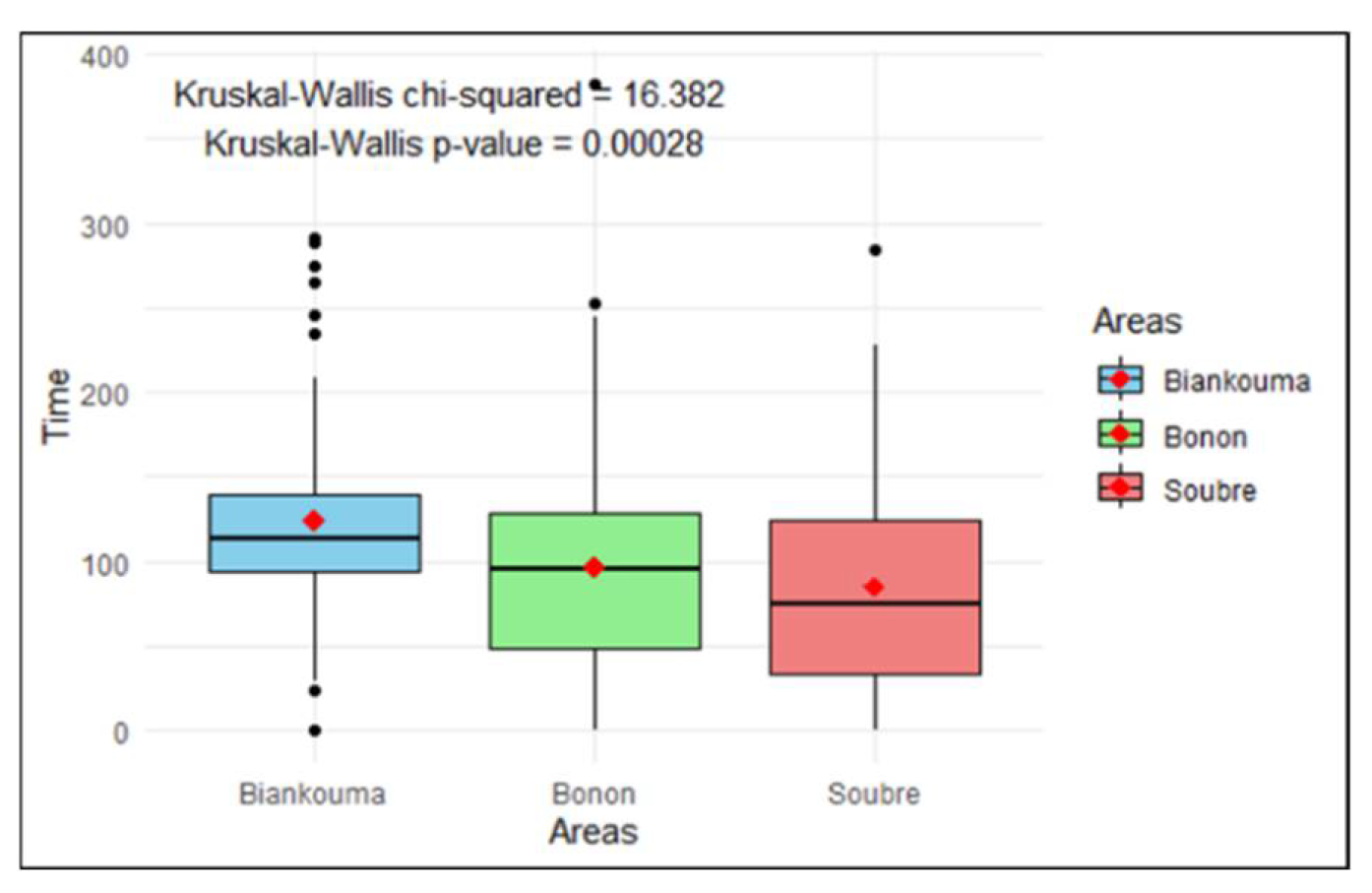

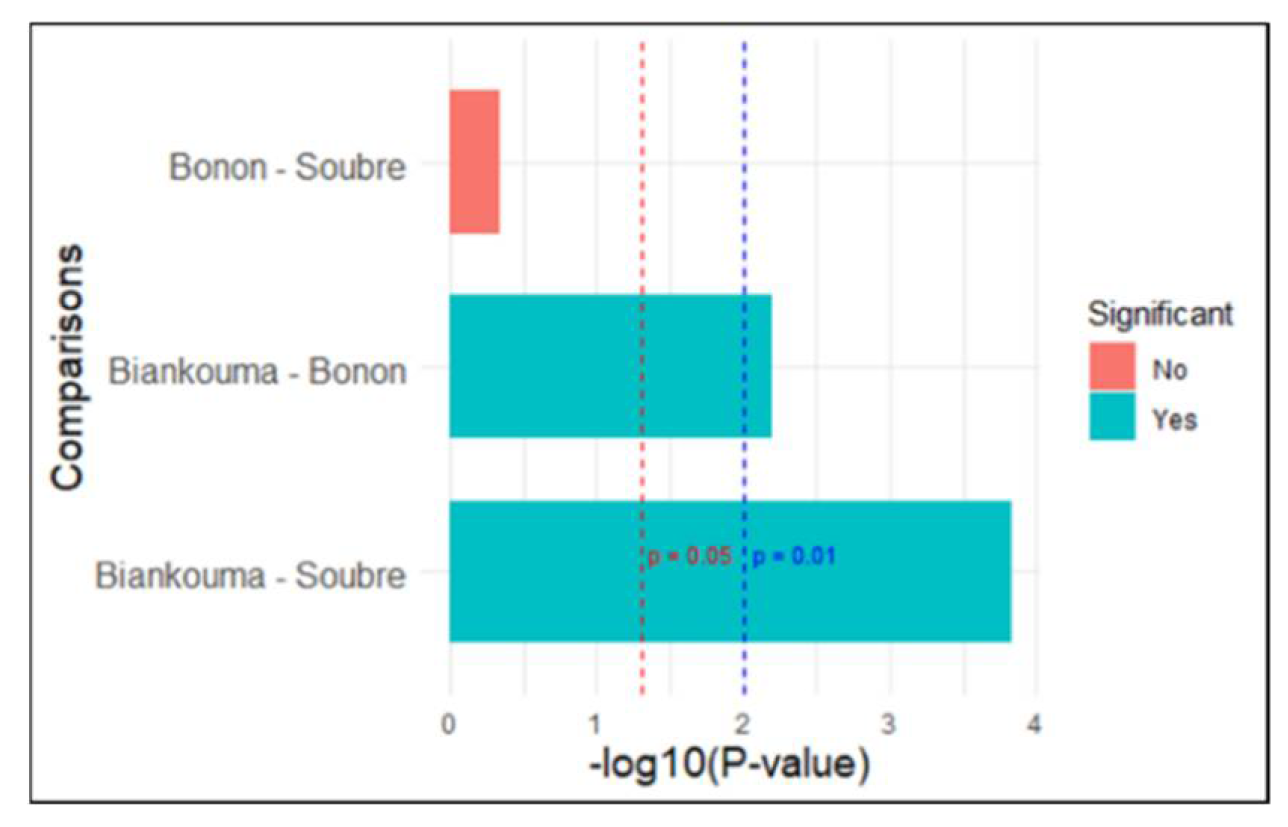

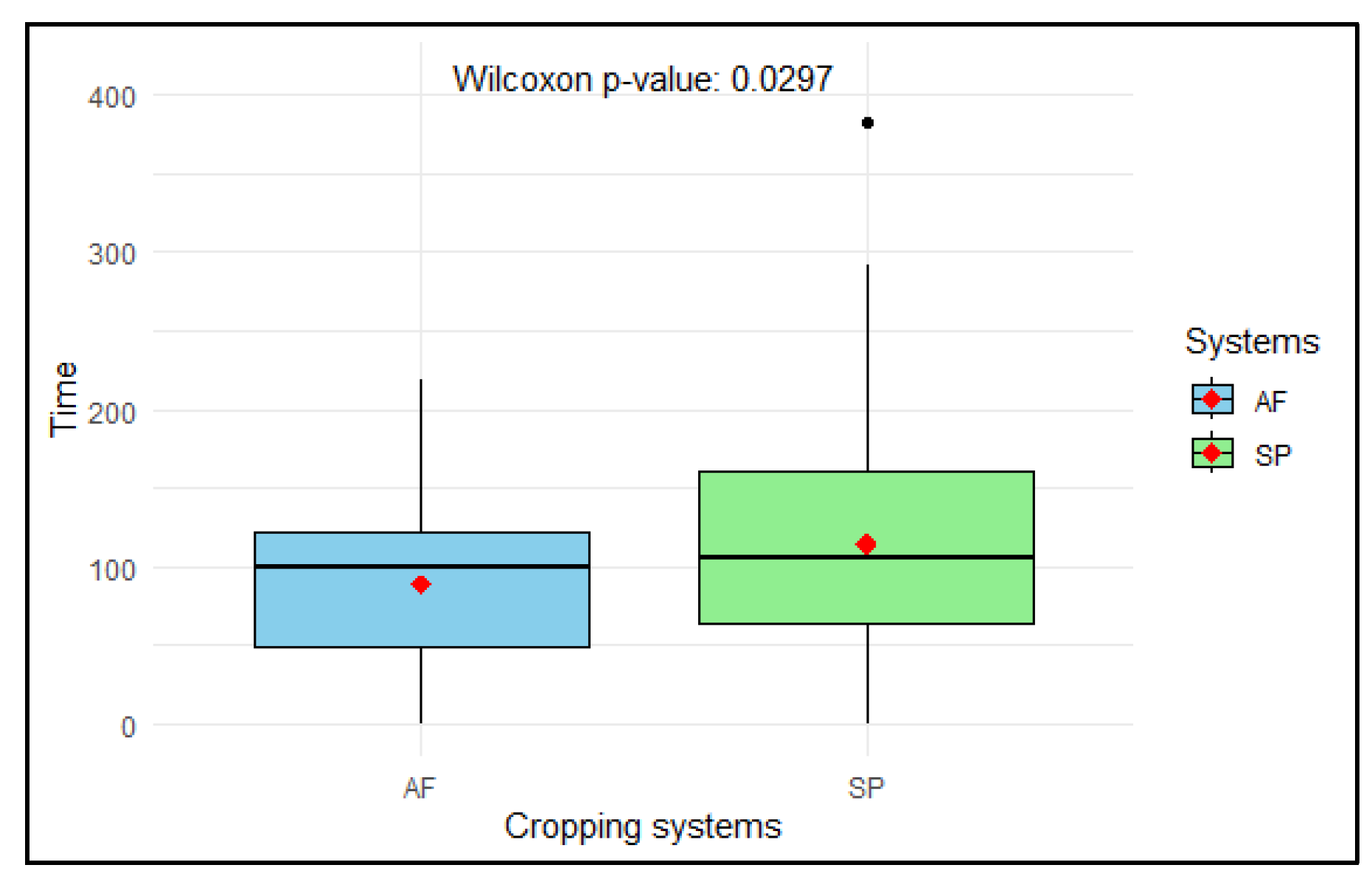

The complexity of the production process was analyzed by comparing production zones and cropping systems in terms of the time taken to produce. The results showed that the workload is significantly heavier for farm families in the new production zone at Biankouma than in the old production zones of Soubré and Bonon. This contrasts with the argument that growers are leaving the old cocoa loops to produce in more fertile areas due to the complexity of work and increased costs in the old zones [25, 24, 27]. While this new zone may offer more fertile land, it also requires greater labor investment due to the very rugged terrain. In Biankouma, there are two distinct landscapes, with savannah on one side and forest on the other. In the forest zone, the terrain is very rugged and plantations are established on mountainsides reaching up to 1,000 meters in altitude [

23]. This makes the work more arduous for the growers, requiring more manpower. What's more, in the savannah zone, growers also have to redouble their efforts to maintain production, as cocoa is grown in less favorable conditions. Although there is no significant difference between the results for Bonon and Soubré, growers spend more time on production in Bonon than in Soubré. This disparity can be explained by local farming practices, where the cocoa-cashew association is favoured. This technique requires regular pruning of cashew branches to ensure good aeration of the plantation, which probably increases the workload. In Soubré, where production seems less complex in terms of workload, it needs to be examined with particular care. Indeed, in this area, part of the locality is heavily affected by the cocoa swollen shoot disease [35, 36], which sometimes discourages growers and leads them to turn to other crops.

The resurgence of disease can also explain the excessive increase in production costs in some cases. Indeed, when plantations are attacked by diseases such as swollen shoot, the successive death of cocoa trees encourages weed growth, which considerably reduces the plantation's ability to produce efficiently [42, 41]. In these situations, although the plantation is no longer able to ensure optimum production, the grower nevertheless continues to invest considerable effort in maintenance, in the hope of harvesting the little cocoa needed for his livelihood. This leads to a significant imbalance between the amount of work involved and the small quantity of cocoa harvested. The cost to the farmer is disproportionate to the yield. In new production zones, where plots are still being set up, the situation is similar. Production has not yet reached its optimum level, while the upkeep and development of young plantations require considerable manpower and resources. This installation phase, combined with yields that are still low, can also lead to a significant increase in production costs per kilogram of cocoa.

As far as cropping systems are concerned, results have shown that agroforestry is more labor-saving than the full-sun system. In fact, agroforestry systems are most often established by natural regeneration and may not require any additional work for the farmer [37, 38]. Once these systems have been established, they can be useful in reducing the farmer's working time. In general, crops grown in full sun are more prone to weeds, requiring more time for weeding. Trees in agroforestry systems, on the other hand, can provide shade and develop competition to reduce weed growth, thus reducing the labour time required [

39].

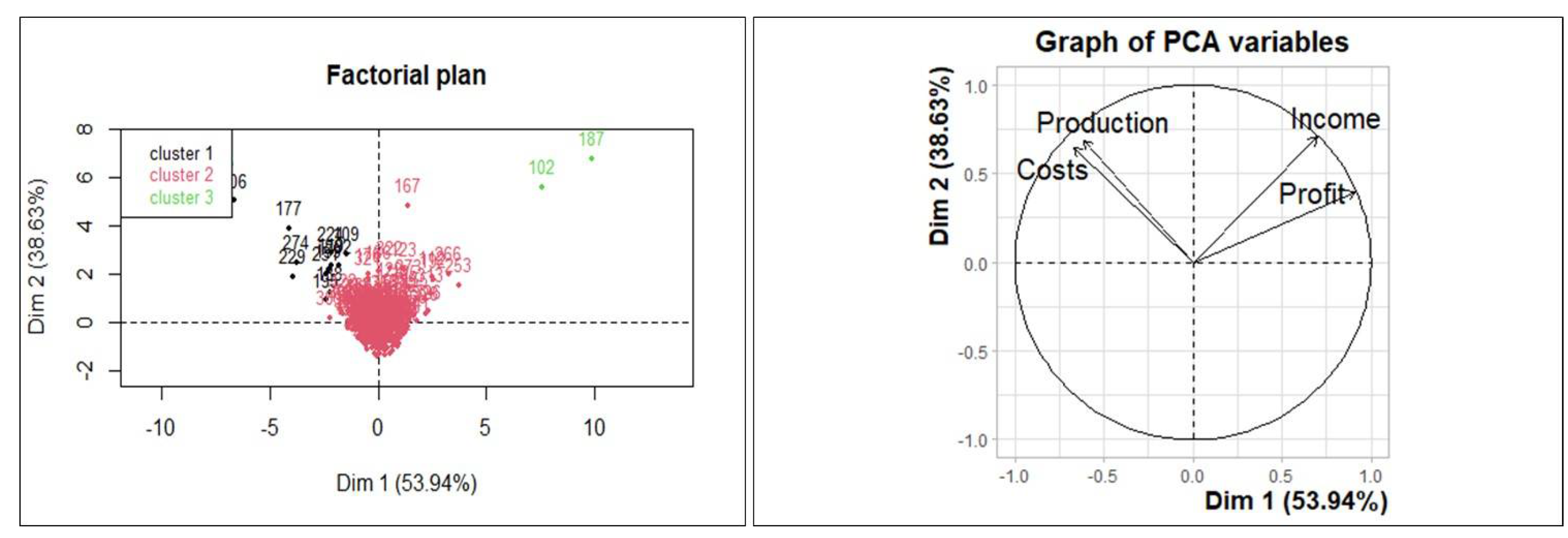

Our results show that social costs, made up of FLC and the cost of land, account for almost 72% of total production costs. FLC in particular represent around 52% of total costs. This implies that FL is the main component of production costs [20, 21, 22]. As a result, production costs are underestimated if opportunity costs are not taken into account, raising doubts about the fairness of producer remuneration. Our results show that, indeed, when opportunity costs are taken into account, around 38% of farmers produce at a loss. [

15] made the same finding on dairy sheep farms in Spain. According to the authors, when opportunity costs are taken into account, 60% of farmers struggle to cover their costs with the prices received, and therefore make a loss. In a study conducted in Turkey, [

43] demonstrated that government support provided to farmers to encourage the adoption of environmentally protective practices did not cover the opportunity cost.

The minimum price received by cocoa farmers is often lower than the official campaign price, set at 900 CFA. This situation can be explained by several factors. Firstly, the isolation and remoteness of certain localities from urban centers generate considerable transport costs for buyers. The latter are then forced to pass on these costs in the purchase price, revising it downwards. What's more, even before the official price is set, some buyers take advantage of the precarious economic situation of producers in difficulty. These producers, in a hurry to sell to meet their immediate needs, often accept prices well below the norm. Buyers speculate on price fluctuations, hoping to make a profit or, on the contrary, risking losses depending on the final price set by the authorities. However, not all producers are on the same footing. Those who are members of cooperatives or involved in certification programs often benefit from a price higher than the official campaign price. Indeed, certifications, which guarantee sustainable and ethical practices, attract buyers willing to pay more to guarantee the quality and origin of their cocoa.

What's more, the cost of producing one kilogram of cocoa is 82 CFA higher than the selling price. It's as if producers were subsidizing production, which raises questions about the long-term economic viability of these farms. There is therefore an imbalance between the effort invested in farming and the benefits obtained in return. This, in turn, can cause farmers to lose interest or disengage from cocoa farming. This is the case for Soubré farmers, who are gradually turning to other crops, in this case rubber and palm. In this sense, [

14] argue that in a context where opportunity costs are too high, labor productivity will be the main criterion for crop selection. Diversification can be seen as a strategy for mitigating financial risks and improving profitability, but it also highlights the growing difficulties of maintaining cocoa production under unfavorable economic conditions.