1. Introduction

Classic Hutchinson‒Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) is a rare premature aging disorder, that occurs in approximately 1 in 4 million individuals. It is caused by a mutation in the

LMNA gene on Chr.1q22 (c.1824C>T, p.G608G) [

1,

2], leading to progerin accumulation. Farnesylated progerin disrupts nuclear envelope stability, impairs DNA repair, and accelerates aging. Progeria patients look similar to normal babies at birth. However, severe growth failure and sclerotic skin changes begin in infancy. Over time, distinctive facial features, including hair loss, prominent eyes, micrognathia, a beaked nose, lipodystrophy, and joint stiffness, become evident [

3,

4,

5]. After the age of 2 years, the mean growth rate is only 3.58 cm/year, and weight gain is limited to 0.44 kg/year [

6,

7]. The accumulation of progerin also induces rapid atherosclerosis through vascular smooth muscle cell depletion in the media and endothelial cell dysfunction, promoting the formation of unstable plaques prone to rupture [

8,

9]. These changes lead to a mean life expectancy of 14.5 years, with cardiovascular complications being the primary cause of death [

10,

11].

Lonafarnib (Zokinvy®), a farnesyltransferase inhibitor, is the first and only approved drug for progeria, extending life expectancy by an average of 2.5 years [

12,

13]. Moreover, it has positive effects on weight gain, cardiovascular stiffness, bone structure, and audiological status [

14]. However, its high cost, gastrointestinal side effects affecting over 80%, and limited accessibility in some countries pose barriers to its use. Additionally, lonafarnib alone does not fully halt disease progression, leading to studies on combination therapies, such as zoledronic acid, pravastatin, or everolimus, to improve its efficacy [

15,

16].

Stem cell exhaustion is characteristic of HGPS. Increased nuclear fragility, increased mitochondrial oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation lead to high cell turnover, which depletes progenitor cells. High cell turnover accelerates telomere shortening. These consequences ultimately result in stem cell depletion [

17,

18,

19]. Progerin accumulation also reduces the capacity for the proliferation and differentiation of MSCs in progeria patients and contributes to premature aging symptoms [

20]. According to Wiener et al., the premature exhaustion of endothelial progenitor cells in progeria contribute atherosclerosis. Stem cell depletion is also linked to various symptoms, such as lipodystrophy, hair loss, joint stiffness, and delayed dentition [

19].

Mesenchymal stem cell (MSCs) therapy has demonstrated immune modulating properties [

21], therapeutic potential against aging[

22], atherosclerosis [

23,

24], and stroke owing to its paracrine effects and regenerative potential[

25]. Notably, commercially available MSC products provide easier accessibility for clinical application.

Given their potential to address the multifaceted pathology of HGPS, we invetstigated the efficacy and safety of intravenous (IV) allogeneic bone marrow-derived clonal MSC therapy for HGPS as a novel approach to mitigate premature segmental aging in HGPS.

2. Case Report

2.1. Case Description

The patient was a 7-year–9-month-old male with classic HGPS at the start of the study. This study protocol was approved by the Korean Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, Advanced Regenerative Medicine (R-3-0005), and informed consent was obtained from the patient and his parents.

The patient was born full term with a birth weight of 2.8 kg (11.8 percentile). However, severe growth failure due to poor feeding and abdominal sclerodermoid changes were observed within one month of birth. By 5 months of age, his weight(5.3 kg) and height(61 cm) had fallen below the 1st percentile. At age 5, the patient was diagnosed with progeria due to an LMNA mutation (c.1824C>T). A comprehensive evaluation was conducted at the time of diagnosis. He exhibited hair loss with prominent scalp veins, and impaired nail growth, including joint contractures, particularly in the hand and foot. Brain magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) revealed mild to moderate atherosclerosis in the bilateral internal carotid arteries and severe segmental stenosis of the bilateral vertebral arteries with collateral vessels, although the patient had no preceding neurological symptoms. Atorvastatin and clopidogrel were started on the basis of the vascular state. Echocardiography revealed normal ventricular function with trivial tricuspid regurgitation and pulmonary regurgitation. At age 6 years and 9 months, the patient experienced his first transient ischemic attack (TIA), with symptoms of severe headache, dizziness and lower extremity weakness, all of which resolved spontaneously.

2.2. Study Design

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of allogenic bone marrow-derived clonal MSCs in a patient with HGPS. This study was designed after patients visited our hospital. The study was planned for 24 months and included screening, a treatment phase, an interim evaluation, and follow-up periods. Five IV administrations of MSCs (2.5x10⁵ cells/kg each, SCM-AGH, SCM Life Sciences) were planned. The first three doses were administered at one-month intervals. An interim evaluation was conducted three months following the third injection, after which two additional doses were administered at six-month intervals. The inclusion criteria were (1) a typical phenotype of HGPS, (2) confirmation of HGPS by genetic testing and (3) AST/ALT< 5 times the upper limit of the normal range for age. The exclusion criteria were (1) severe renal impairment (glomerular filtration rate [GFR]<30 mL/min/1.73 m2), (2) received any other clinical trial treatment 90 days prior to the start of this study, and (3) severe adverse drug reactions during stem cell therapy. The patient underwent comprehensive baseline assessments, including growth (anthropometric measurements, IGF-1, IGFBP3, and z score for age), metabolic (AST, ALT, insulin, c-peptide, Hba1c, and cholesterol), proinflammatory and atherosclerosis-associated cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-8, and IL-18; monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1); and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (sICAM-1)), brain (MRA), cardiac (chest X-ray, electrocardiography, echocardiography, brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity [baPWV] testing, carotid intima-media thickness [cIMT] measurement), ophthalmological, auditory (impedance, pure tone audiogram), and musculoskeletal (bone marrow density (BMD) and range of motion (ROM)) measurements. All blood tests were performed once at a time when the intravenous line was established for MSC administration, considering the vascular state of the patient. To prevent vascular occlusive complications following MSC administration, such as pulmonary embolism, enoxaparin was administered subcutaneously at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg before and after MSC infusion. The study was terminated prematurely because of death 10 months after the start of the study and 2 months after the 4th dose of MSCs. To assess the efficacy of MSC treatment, we compared changes across three periods: the two years prior to treatment, the treatment period, and the posttreatment period, encompassing the natural progression of progeria. Adverse reactions were assessed via the WHO-UMC causality assessment system and the common terminology of criteria for adverse events (CTCAE). This study was registered with the Clinical Research Information Service (CRIS number: KCT0008336).

3. Results

3.1. Improvements in Body Composition, Bone Mineral Density and Dentition

Following treatment, notable improvements in bone mineral density (BMD), lean body mass, and dentition status were observed. In particular, BMD significantly increase from baseline. The total body-less head BMD, which had declined by 20.5% before treatment, improved to a positive change of 2.8% after therapy (0.556 g/cm² → 0.442 g/cm² → 0.455 g/cm²). Similarly, the lumbar spine BMD, which decreased by 0.6% during the pretreatment period, increased by 26.5% after treatment. Notably, the lumbar spine BMD z-score, which decreased from -1.8 to -2.0 before therapy, improved to -1.4 after treatment, indicating a positive response to the intervention (

Figure 1A). Lean body mass significantly increased from baseline, with total lean mass increasing from -0.8% to 11.5% and total body-less head (TBLH) lean mass increasing from 3.5% to 14.6% over an 8-month period, surpassing the levels observed two years before treatment (

Figure 1B). All the primary teeth were retained before treatment. After MSC administration, the previously retained deciduous teeth exhibited mobility, rapid eruption of permanent teeth and exfoliation of primary teeth following the first (#51, #52, #71), second (#81), and fourth (#61) administrations of MSCs.

3.2. Amelioration of Stiffness: Joints, Tympanic Membrane, and Arterial Flexibility

Treatment led to improvements in the stiffness of joint mobility, tympanic membrane, and arterial stiffness. The ROMs of the hip, knee, shoulder, and elbow joints increased slightly. However, the ROMs of the wrist and fingers did not improve (

Figure S1). A decrease in tympanic membrane stiffness was observed via tympanometry, leading to improved hearing, as confirmed by pure tone audiometry (

Figure S2A,B). BaPWV, an indicator of arterial stiffness, decreased by an average of 9.98% with treatment. Specifically, the velocity decreased from 1113 cm/s to 1011 cm/s on the right side and from 1228 cm/s to 1097 cm/s on the left side (

Table 1). These findings indicate that the treatment effectively improved stiffness and overall physiological function.

3.3. Short-Term Improvement in Growth and Metabolic Aspects

Weight gain improved with MSC treatment, and after two months of treatment, the greatest improvement in all indicators (weight, height, IGF-1, IGFBP3, and HbA1c) was observed. A weight gain of 1 kg was observed during the 8-month treatment period, whereas only 0.5 kg was observed over the two-year pretreatment period. The change in the z-score during the post treatment period was + 0.75, wherase that during the pretreatment period was -1.13. The increase in the growth rate is less clear, but the rate of z-score deterioration has slowed. The IGF-1 level rose from 173.1 ng/mL (z score: 0.03) to 235.6 ng/mL (z score: 1.32), and the IGFBP3 level rose from 1786.5 ng/mL (z score: -1.6) to 2664.7 ng/mL (z score: 0.37) after 2 months of treatment. In terms of metabolism, glycemic control improved initially (glycated hemoglobin [HbA1c]: 5.8% → 5.5% in 2 months). However, by 6 months after the third MSC administration, these gains had diminished (

Table 1). Metabolic abnormalities associated with steatotic liver disease (MASLD) was observed with abdominal ultrasound at baseline and did not progress during treatment (

Table 1).

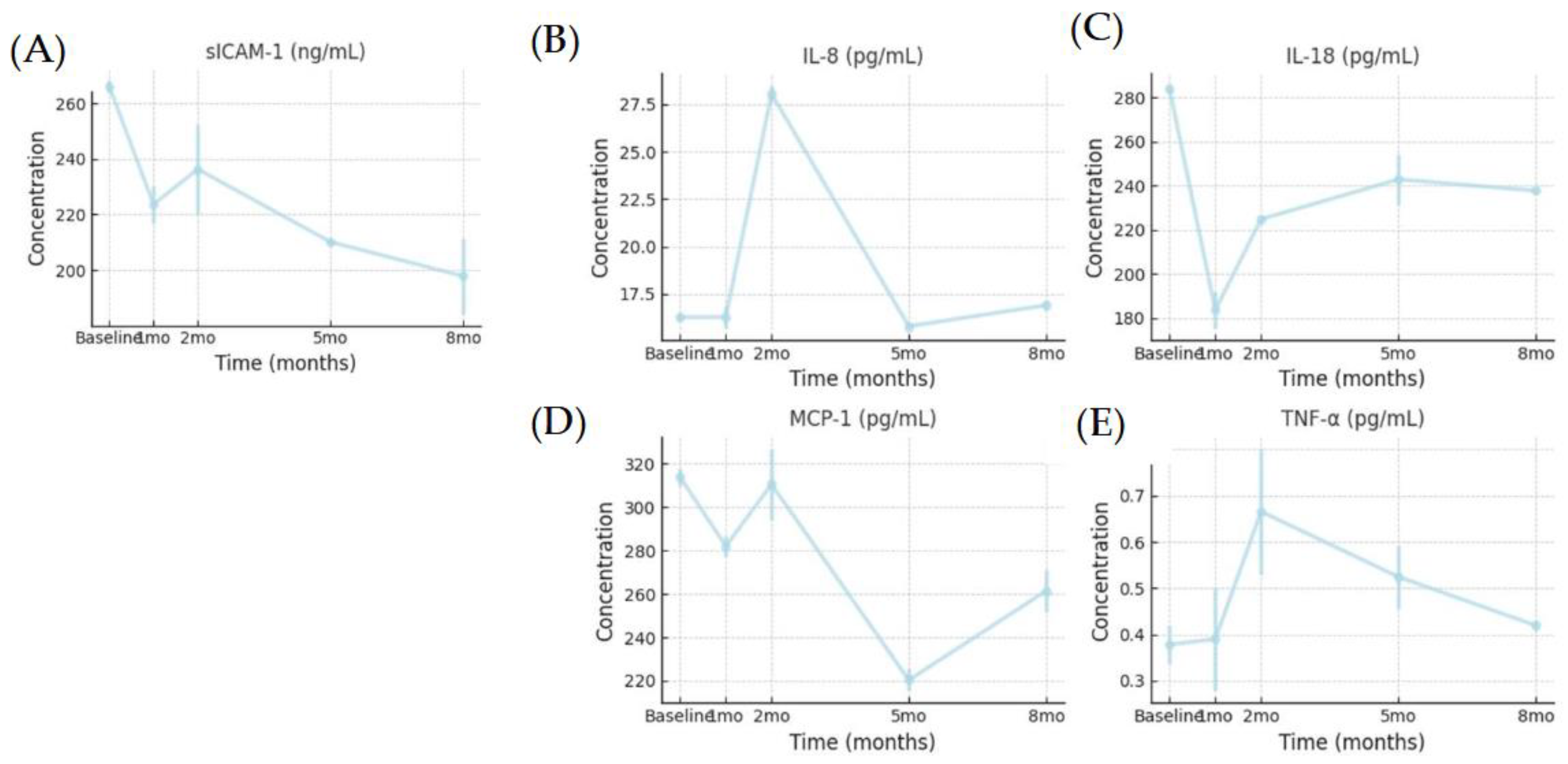

3.4. Reduction in Inflammatory Cytokines

We evaluated the cytokines IL-18, MCP-1, sICAM-1, IL-8, TNF- α, and IL-1β. IL-1β was undetectable throughout the study. Assessment of the expression of proinflammatory and atherosclerosis-associated cytokines in systemic blood revealed sustained downregulation of sICAM-1 with repeated administration, suggesting reduced vascular inflammation. IL-18, MCP-1, and sICAM-1 levels decreased after the first dose infusion, indicating reduced inflammation with MSC treatment. Increased IL-8 levels with repeated MSC treatment improve endothelial cell function by increasing endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity and inhibiting smooth muscle cell proliferation and platelet aggregation, thereby regulating vascular tone, improving endothelial cell function and reducing oxidative stress. However, in the context of cytokine changes, we assume that the efficacy of MSCs decreases over time.

Figure 1.

Changes in the levels of the following serum cytokines: (A) sICAM-1, (B) IL-8, (c) IL-18, (D) MCP-1, (E) TNF-α. sICAM-1, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1; IL-18, interleukin-18; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. ; IL-8, interleukin-8; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; IL-1β, interleukin-.

Figure 1.

Changes in the levels of the following serum cytokines: (A) sICAM-1, (B) IL-8, (c) IL-18, (D) MCP-1, (E) TNF-α. sICAM-1, soluble intercellular adhesion molecule-1; IL-18, interleukin-18; MCP-1, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1. ; IL-8, interleukin-8; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α; IL-1β, interleukin-.

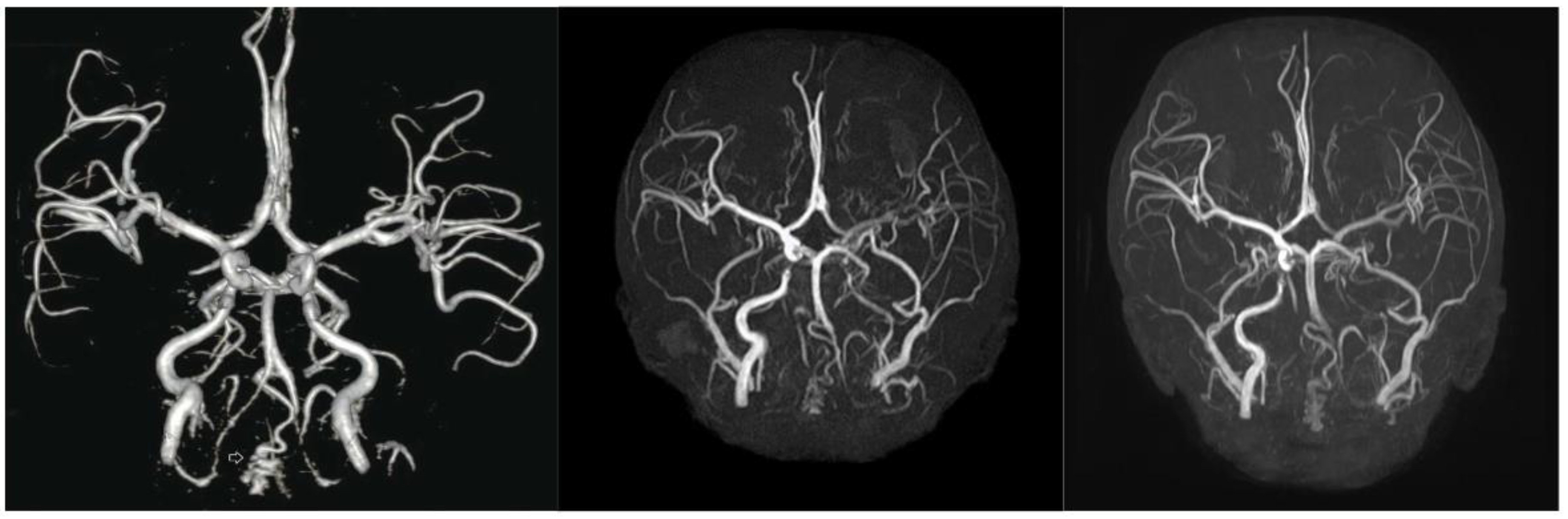

3.5. Lower Efficacy for Atherosclerosis and Cardiovascular Aspects

Despite treatment, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular deterioration did not stop or reverse. However, cerebrovascular deterioration shows a delayed progression. Two years before treatment, severe segmental stenosis of the bilateral vertebral arteries and mild stenosis of the bilateral ICA with collateral vessels were observed (

Figure 2A). At baseline, vertebral artery stenosis progressed, and hypoplastic changes with segmental total occlusion in the left ICA were observed. Although the treatment did not completely halt vascular deterioration, no severe worsening was observed. (

Figure 2C).

On the other hand, atherosclerosis and cardiac dysfunction progression were evident. The atherosclerotic marker cIMT increased during treatment. At 5 months, the right mean cIMT increased from 0.47 mm to 0.61, exceeding the normal range (0.365–0.58mm) [

26]. Additionally, right maximum cIMT also increased from 0.60 to 0.80 mm. Progression of mild diastolic dysfunction was observed through tissue Doppler imaging (early diastolic velocity 7→5.89 cm/s normal>8 cm/s, E/e 16.1-> 12.28 normal< 8). Systolic function, as measured by the ejection fraction and fractional shortening, was within the normal range but declined over time. No calcification was detected on TTE during treatment (

Table 1).

3.6. Safety of MSC Treatment

Unfortunately, MSC therapy did not result in an extension of the patient’s lifespan. The study was terminated prematurely at age 8 years and 7 months because of death 10 months after the start of treatment. The cause of death was presumed to be postexercise arrhythmia and was unlikely to be directly related to stem cell treatment. This conclusion is supported by the fact that the initial onset of chest pain occurred approximately one month after the final treatment, and both D-dimer and CK-MB levels remained within normal limits throughout the treatment period. This might be an inevitable consequence of the rapid progression of progeria and its natural course.

During MSC administration, the only adverse events that occurred within 24 hours of administration were nausea, vomiting and dizziness with the first dose. At the 1

st dose, lorazepam was administered concurrently to relieve anxiety. Without lorazepam, the side effects do not appear repeatedly, so it looks less relevant to stem cell therapy. Hand weakness lasting for an hour and a half without headache at 6 days after the first dose might be associated with his basal vascular state, which is less likely with MSC therapy. Frequent epistaxis was thought to be due to the use of clopidogrel. Thirty-six days after the 4th MSC treatment, the patient reported intermittent, stress-induced chest pain lasting 1–2 minutes, which resolved completely. An immediate attempt to conduct additional evaluation was made, but patient refused scheduling delays because various circumstances resulted in unexpected death during daily activities. Other mild adverse reactions associated with infection were noted (

Table S1).

4. Discussion

This study was designed to be systemic from the outset, and to our knowledge, is the first to administer a precise cell count of MSCs to a patient with progeria. Safety was ensured through precise quantification and repeated administration of MSCs, along with comprehensive monitoring.

Like lonafarnib [

13], this study confirmed that MSC therapy also has positive effects on bone structure, the stiffness of arteries and joints, and low-frequency sensorineural hearing. Additionally, MSC therapy improved dentition and had anti-inflammatory effects, with short-term positive effects on growth and metabolism. Previously, there were two cases of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in HGPS. A single using adipose tissue derived stromal vascular fractions containing MSCs showed improvement in growth rate, weight gain and IGF-1 levels [

27]. Another patient treated with cord blood cells exhibited decreased PWV, increased height, weight gain, and increased ROM of the proximal joint [

28]. These results were consistent with our study. However, positive effects on cIMT observed in the lonafarnib and cord blood treatment studies were not observed in this study. This difference seems to be due to poor vascular conditions at baseline.

At baseline, the patient rapidly progressed to vascular changes. He had bilateral vertebral artery stenosis at diagnosis, and additional ICA stenosis had developed over two years. Murtada et al reported that the aortic phenotype worsened rapidly as the disease progressed toward the terminal stage in mouse models [

29]. Despite active LDL-cholesterol management using lipid-lowering agents for preventing stroke, the results of cIMT and TTE indicated the progression of atherosclerosis and cardiac deterioration. This aligns with the findings of a clinical trial in which combined therapy with lonafarnib, pravastatin, and zoledronate did not demonstrate increased efficacy compared with lonafarnib alone [

15]. The failure of lipid-lowering drugs to improve arteriosclerosis is thought to be attributed to a distinct mechanism specific to progeria. TTE result in the progression of diastolic dysfunction, a characteristic finding in patients with progeria[

30]. Since cerebrovascular states worsen at an early age, we believe that a similar change would be observed in the coronary artery. We considered cardiac MRI for further evaluation of the coronary artery and calcification, but we could not perform cardiac MRI because of poor patient compliance and the risks of anesthesia

The clinically proven drug for cardiovascular manifestations in progeria is lonafarnib, the efficacy of which has been demonstrated in a mouse model through the use of progerinin [

31] and antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) [

32]. These drugs effectively lower progerin levels. Unfortunately, progerin levels were not assessed in this study. However, the effects of MSC therapy on vascular health were confirmed to occur through changes in baPWV and cytokine levels. Baseline measurements revealed an elevated baPWV in the patient, with a mean value of 1170 cm/s, which exceeds the 95th percentile for a healthy 12-year-old boy (1039 cm/s) [

33]. Given that the PWV naturally increases with age and height, this value indicates a significant degree of arterial stiffness. After MSC treatment, the patient demonstrated a reduction in baPWV, suggesting an improvement in arterial stiffness and a positive therapeutic response. sICAM-1 is an inflammatory marker and an oxidative stress marker that acts on endothelial cells and plays a key role in cardiovascular disease [

34,

35]. ICAM-1 expression in endothelial cells is induced by TNF-α and IL-1β [

35] and the proinflammatory factors MCP-1 [

36] and IL-18 [

37] in atherosclerosis. A continuous decrease in sICAM-1 levels indicates a reduction in inflammation and a risk of progression to atherosclerosis.

This study was conducted with a single subject due to the extremely low prevalence. Therefore, it is not suitable for statistical analysis, but the findings provide valuable insights. As observed in brain MRA follow-ups, it can alleviate deterioration but not halt or reverse structural changes. Therefore, it is crucial to administer these drugs before irreversible changes begin to maximize therapeutic benefits. Some effects of MSCs are short-lived and relatively insufficient. In this study, a low dose of MSCs (2.5*10

5 cells/kg) was chosen to prioritize vascular safety considering patients’ compromised vascular status, such as that of individuals in their 80s, and history of TIA. According to Kabat [

38], MSCs have minimal effective doses (MEDs) ranging from 70--190 million MSCs/patient/dose. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved Prochymal cell dose for children with graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is 2*10

6 cells/kg [

39]. The recommended dose of SCM-AGH for atopic dermatitis is 10

6 cells/kg[

40]. Dose escalation should be considered in further studies, as safety was ensured throughout this study.

5. Literature Review

Recent advances in stem cell research have opened new therapeutic avenues for HGPS. In a notable study by Suh et al. (2021), a 13-year-old patient received three IV infusions of allogeneic cord blood cells, which were administered at four-month intervals[

28]. Clinical observations following these treatments revealed increased skin elasticity, evidence of hair growth, and increased body weight. These findings support the hypothesis that cord blood stem cells may exert trophic effects or partially replace damaged cells in HGPS.

Parallel progress in cellular reprogramming has also provided insights into HGPS pathophysiology. Lo Cicero and Nissan (2015) described the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) from HGPS patient fibroblasts, including those from the above pediatric patients[

41]. Through subsequent multilineage differentiation of these iPSCs, researchers have investigated the underlying disease mechanisms and established a platform for drug screening. Zhang et al. advanced this approach by differentiating iPSC-derived cells to uncover specific defects in vascular smooth muscle cells and MSCs, revealing potential targets for therapeutic intervention [

42].

Findings from stem cell transplantation studies in animal models further underscore the potential of regenerative therapies for HGPS. For example, Lavasani et al. (2012) reported that injecting young wild-type muscle-derived stem/progenitor cells into progeroid mice extended both their healthspan and lifespan [

43]. Evaluations of multiple health parameters strongly support the therapeutic potential of stem cell transplantation.

Complementing cell-based interventions, Xiong et al. (2015) examined the effects of methylene blue on HGPS patient-derived fibroblasts and demonstrated improvements in nuclear architecture, mitochondrial function, and progerin solubility [

44]. This work highlights the potential of pharmacological agents to alleviate certain cellular abnormalities in HGPS, although these agents are not substitutes for stem cell therapies or the broader regenerative effects that they might offer.

Despite these promising findings, the translation of stem cell therapies into clinical practice remains challenging. For example, Scaffidi and Misteli (2008) noted that progerin can compromise human MSC function by promoting premature aging pathways, thereby diminishing the effectiveness of endogenous stem cell pools [

45]. In parallel, Rosengardten et al. (2011) reported that specific HGPS mutations reduced adult stem cell populations and impaired wound healing capacity in a conditional HGPS mouse model [

19]. Taken together, these findings underscore the importance of targeted strategies—potentially including allogeneic or autologous stem cell replacement—to counter stem cell depletion in HGPS.

In summary, stem cell research has substantially advanced our understanding of HGPS and yielded potential therapeutic strategies. Whether through cord blood cell infusions, iPSC-based modeling, or transplantations of muscle-derived stem cells, the accumulated evidence points toward regenerative medicine as a promising pathway. However, further elucidation of key mechanisms is required, and robust clinical trials will be essential for establishing the efficacy and safety of these novel interventions.

Table 3.

In vivo and in vitro stem cell research on HGPS. HGPS: Hutchinson‒Gilford progeria syndrome; SVF, stromal vascular fraction; iPSCs, induced pluripotent stem cells; MDSPCs, muscle-derived stem/progenitor cells.

Table 3.

In vivo and in vitro stem cell research on HGPS. HGPS: Hutchinson‒Gilford progeria syndrome; SVF, stromal vascular fraction; iPSCs, induced pluripotent stem cells; MDSPCs, muscle-derived stem/progenitor cells.

| Year |

Authors |

Subjects |

Methodology |

Key Findings |

Mechanism of Action |

Clinical Implications |

Limitations/Future Directions |

| 2021[28] |

Suh YS, et al. |

13-year-old HGPS patient |

Cord blood stem cell infusion |

Improved skin elasticity, hair growth, weight gain |

Cord blood stem cells may provide trophic support and replace damaged cells |

Potential noninvasive treatment for HGPS |

Single case study; larger trials needed |

| 2020 [27] |

Park J et al. |

13-year-old HGPS |

adipose SVF containing MSC |

Increased height, weight and IGF-1 |

anti-inflammatory effects via paracrine signaling |

Proposal for the potential treatment of inflammaging-related diseases |

Single case study; larger trials needed |

| 2015 [41] |

Lo Cicero A, Nissan X |

iPSCs |

iPSC modeling of HGPS |

Improved understanding of disease mechanisms |

iPSCs recreate HGPS cellular environment for study |

Improved drug screening platform |

Translation to in vivo models needed |

| 2011[42] |

Zhang J, et al. |

iPSC-derived cells |

iPSC differentiation and analysis |

Vascular smooth muscle and mesenchymal stem cell defects identified |

iPSCs reveal specific cellular defects in HGPS |

New targets for therapeutic intervention |

Validation in patient samples required |

| 2015[44] |

Xiong ZM, et al. |

HGPS patient-derived fibroblasts |

Treatment with methylene blue (MB); confocal microscopy; western blotting; nuclear fractionation |

MB improved nuclear morphology and mitochondrial function; increased solubility of progerin |

MB upregulates A-type lamin expression and increases progerin solubility; acts as mitochondrial electron carrier |

Potential therapeutic agent for cellular abnormalities in HGPS |

Not direct stem cell therapy; in vivo studies needed |

| 2008 [45] |

Scaffidi P, Misteli T |

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) |

Expression of progerin in hMSCs; analysis of stem cell function |

Discovered misregulation leading to premature aging |

Progerin interferes with the function of hMSCs |

Progerin activates Notch signaling pathway in hMSCs |

Limited to in vitro study; in vivo confirmation needed |

| 2012[43] |

Lavasani M et al. |

Progeroid mice |

Intraperitoneal injection of young wild-type MDSPCs |

Extended lifespan and healthspan of progeroid mice |

Secretion of factors by MDSPCs that improve tissue function |

Stem cell transplantation as potential therapy for progeria |

Limited to animal model; human studies needed |

| 2011[46] |

Liu GH et al.; Ho JC et al. |

HGPS patient fibroblasts |

Generation of iPSCs from HGPS fibroblasts; Differentiation of iPSCs |

iPSCs from HGPS patients lack progerin expression but resume upon differentiation |

Reprogramming suppresses progerin expression; differentiation resumes aging-associated phenotypes |

iPSCs as a model for studying HGPS and drug screening |

Limited to in vitro model; in vivo validation needed |

| 2011 [19] |

Rosengardten Y et al. |

HGPS mouse model |

Analysis of stem cell populations and wound healing capacity |

HGPS mutation causes adult stem cell depletion and impaired wound healing |

Progerin accumulation leads to stem cell exhaustion |

Stem cell therapies may be beneficial for HGPS patients |

Limited to mouse model; human studies needed |

6. Conclusions

Herein, we report the case of a patient with HGPS who received MSC therapy. Our findings suggest that MSC therapy for HGPS is safe and has the potential to increase bone mineral density, reduce joint stiffness and arterial stiffness, and have anti- inflammatory effects. Given that a favorable safety profile was observed, we recommend further studies with increased doses and frequencies, particularly at an earlier age before significant vascular deterioration occurs. Additionally, a personalized protocol with long-term monitoring should be developed to optimize therapeutic outcomes. Since MSC therapy has limited effects on cardiovascular disease, it may be more effective as an adjuvant therapy to lonafarnib than as monotherapy. Furthermore, beyond HGPS, stem cell therapy holds promise for delaying aging, preventing cardiovascular disease and treating rare diseases.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, EY. J., JS. P., SJ. K. HT. S., J. L., GS. C.; methodology, EY. J., JS. P., SJ. K. HT. S., J. L., GS. C.; software, IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA); validation, EY. J., J. L., and GS. C.; formal analysis, EY. J.; investigation, EY. J., JS. P., MJ. Y., SJ. L., HT. S., J. L., GS. C.; resources, SJ. L., HT. S., J. L., GS. C.; data curation, EY. J., MJ. Y.; writing—original draft preparation, EY. J. and JS. P.; writing—review and editing, EY. J., JS. P, J. L.; visualization, EY. J.; supervision, J. L., KS. C.; project administration, EY. J., MJ. Y., J. L., KS. C.; funding acquisition, J. L. and GS. C. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Regenerative Medicine Acceleration Foundation, grant number R -3-0005.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Inha University Hospital (2023-04-040-000, 2024-12-013-000).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the patients and their parents in this study.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge SCM Science for providing in vitro research support and conducting in vivo safety evaluations for MSC therapy.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have received research funding from the Regenerative Medicine Acceleration Foundation. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- De Sandre-Giovannoli, A.; Bernard, R.; Cau, P.; Navarro, C.; Amiel, J.; Boccaccio, I.; Lyonnet, S.; Stewart, C.L.; Munnich, A.; Le Merrer, M.; et al. Lamin a truncation in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria. Science 2003, 300, 2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, M.; Brown, W.T.; Gordon, L.B.; Glynn, M.W.; Singer, J.; Scott, L.; Erdos, M.R.; Robbins, C.M.; Moses, T.Y.; Berglund, P. Recurrent de novo point mutations in lamin A cause Hutchinson–Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature 2003, 423, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansen, T.; Romiti, R. Progeria infantum (Hutchinson-Gilford syndrome) associated with scleroderma-like lesions and acro-osteolysis: a case report and brief review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol 2000, 17, 282–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rork, J.F.; Huang, J.T.; Gordon, L.B.; Kleinman, M.; Kieran, M.W.; Liang, M.G. Initial cutaneous manifestations of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol 2014, 31, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennekam, R.C. Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome: review of the phenotype. Am J Med Genet A 2006, 140, 2603–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merideth, M.A.; Gordon, L.B.; Clauss, S.; Sachdev, V.; Smith, A.C.; Perry, M.B.; Brewer, C.C.; Zalewski, C.; Kim, H.J.; Solomon, B.; et al. Phenotype and course of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. N Engl J Med 2008, 358, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, L.B.; McCarten, K.M.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Machan, J.T.; Campbell, S.E.; Berns, S.D.; Kieran, M.W. Disease progression in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome: impact on growth and development. Pediatrics 2007, 120, 824–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevado, R.M.; Hamczyk, M.R.; Gonzalo, P.; Andres-Manzano, M.J.; Andres, V. Premature Vascular Aging with Features of Plaque Vulnerability in an Atheroprone Mouse Model of Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome with Ldlr Deficiency. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Mojiri, A.; Boulahouache, L.; Morales, E.; Walther, B.K.; Cooke, J.P. Vascular senescence in progeria: role of endothelial dysfunction. Eur Heart J Open 2022, 2, oeac047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, L.B.; Massaro, J.; D'Agostino, R.B., Sr.; Campbell, S.E.; Brazier, J.; Brown, W.T.; Kleinman, M.E.; Kieran, M.W.; Progeria Clinical Trials, C. Impact of farnesylation inhibitors on survival in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Circulation 2014, 130, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A.; Gordon, L.B.; Kleinman, M.E.; Gurary, E.B.; Massaro, J.; D'Agostino, R., Sr.; Kieran, M.W.; Gerhard-Herman, M.; Smoot, L. Cardiac Abnormalities in Patients With Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome. JAMA Cardiol 2018, 3, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, L.B.; Shappell, H.; Massaro, J.; D'Agostino, R.B., Sr.; Brazier, J.; Campbell, S.E.; Kleinman, M.E.; Kieran, M.W. Association of Lonafarnib Treatment vs No Treatment With Mortality Rate in Patients With Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome. JAMA 2018, 319, 1687–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, M.; Jeng, L.J.B.; Chefo, S.; Wang, Y.; Price, D.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Li, R.J.; Ma, L.; Yang, Y.; et al. FDA approval summary for lonafarnib (Zokinvy) for the treatment of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome and processing-deficient progeroid laminopathies. Genet Med 2023, 25, 100335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, L.B.; Kleinman, M.E.; Miller, D.T.; Neuberg, D.S.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Gerhard-Herman, M.; Smoot, L.B.; Gordon, C.M.; Cleveland, R.; Snyder, B.D.; et al. Clinical trial of a farnesyltransferase inhibitor in children with Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 16666–16671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, L.B.; Kleinman, M.E.; Massaro, J.; D'Agostino, R.B., Sr.; Shappell, H.; Gerhard-Herman, M.; Smoot, L.B.; Gordon, C.M.; Cleveland, R.H.; Nazarian, A.; et al. Clinical Trial of the Protein Farnesylation Inhibitors Lonafarnib, Pravastatin, and Zoledronic Acid in Children With Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome. Circulation 2016, 134, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abutaleb, N.O.; Atchison, L.; Choi, L.; Bedapudi, A.; Shores, K.; Gete, Y.; Cao, K.; Truskey, G.A. Lonafarnib and everolimus reduce pathology in iPSC-derived tissue engineered blood vessel model of Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halaschek-Wiener, J.; Brooks-Wilson, A. Progeria of stem cells: stem cell exhaustion in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2007, 62, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridger, J.M.; Kill, I.R. Aging of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome fibroblasts is characterised by hyperproliferation and increased apoptosis. Exp Gerontol 2004, 39, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengardten, Y.; McKenna, T.; Grochova, D.; Eriksson, M. Stem cell depletion in Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Aging Cell 2011, 10, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prolla, T.A. Multiple roads to the aging phenotype: insights from the molecular dissection of progerias through DNA microarray analysis. Mech Ageing Dev 2005, 126, 461–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowska, S.; Andrzejewska, A.; Janowski, M.; Lukomska, B. Immunomodulatory and Regenerative Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Extracellular Vesicles: Therapeutic Outlook for Inflammatory and Degenerative Diseases. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 591065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Ge, J.; Huang, C.; Liu, H.; Jiang, H. Application of mesenchymal stem cell therapy for aging frailty: from mechanisms to therapeutics. Theranostics 2021, 11, 5675–5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogay, V.; Sekenova, A.; Li, Y.; Issabekova, A.; Saparov, A. The Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cells in the Treatment of Atherosclerosis. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther 2021, 16, 897–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwin, T.; Gomes, A.; Amin, R.; Sufi, A.; Goswami, S.; Wang, B. Mechanisms underlying the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells in atherosclerosis. Regen Med 2021, 16, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Dong, N.; Hong, H.; Qi, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J. Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Therapeutic Mechanisms for Stroke. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drole Torkar, A.; Plesnik, E.; Groselj, U.; Battelino, T.; Kotnik, P. Carotid Intima-Media Thickness in Healthy Children and Adolescents: Normative Data and Systematic Literature Review. Front Cardiovasc Med 2020, 7, 597768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, J.; Lee, J.H.; Jeon, J.H.; Kim, Y.B.; Jeong, B.C.; Lee, S.H. Potential Benefits of Allogeneic Haploidentical Adipose Tissue-Derived Stromal Vascular Fraction in a Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome Patient. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020, 8, 574010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, M.R.; Lim, I.; Kim, J.; Yang, P.S.; Choung, J.S.; Sim, H.R.; Ha, S.C.; Kim, M. Efficacy of Cord Blood Cell Therapy for Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome-A Case Report. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtada, S.I.; Mikush, N.; Wang, M.; Ren, P.; Kawamura, Y.; Ramachandra, A.B.; Li, D.S.; Braddock, D.T.; Tellides, G.; Gordon, L.B.; et al. Lonafarnib improves cardiovascular function and survival in a mouse model of Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Elife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, F.J.; Gordon, L.B.; Smoot, L.; Kleinman, M.E.; Gerhard-Herman, M.; Hegde, S.M.; Mukundan, S.; Mahoney, T.; Massaro, J.; Ha, S.; et al. Progression of Cardiac Abnormalities in Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. Circulation 2023, 147, 1782–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.M.; Seo, S.; Song, E.J.; Kweon, O.; Jo, A.H.; Park, S.; Woo, T.G.; Kim, B.H.; Oh, G.T.; Park, B.J. Progerinin, an Inhibitor of Progerin, Alleviates Cardiac Abnormalities in a Model Mouse of Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdos, M.R.; Cabral, W.A.; Tavarez, U.L.; Cao, K.; Gvozdenovic-Jeremic, J.; Narisu, N.; Zerfas, P.M.; Crumley, S.; Boku, Y.; Hanson, G.; et al. A targeted antisense therapeutic approach for Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Nat Med 2021, 27, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sougawa, Y.; Miyai, N.; Utsumi, M.; Miyashita, K.; Takeda, S.; Arita, M. Brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in healthy Japanese adolescents: reference values for the assessment of arterial stiffness and cardiovascular risk profiles. Hypertens Res 2020, 43, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Kaur, R.; Kumari, P.; Pasricha, C.; Singh, R. ICAM-1 and VCAM-1: Gatekeepers in various inflammatory and cardiovascular disorders. Clin Chim Acta 2023, 548, 117487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.M.; Wiesolek, H.L.; Sumagin, R. ICAM-1: A master regulator of cellular responses in inflammation, injury resolution, and tumorigenesis. J Leukoc Biol 2020, 108, 787–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Kakkar, V.; Lu, X. Impact of MCP-1 in atherosclerosis. Curr Pharm Des 2014, 20, 4580–4588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, A.; Sathyapalan, T.; Sahebkar, A. The Role of Interleukin-18 in the Development and Progression of Atherosclerosis. Curr Med Chem 2021, 28, 1757–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat, M.; Bobkov, I.; Kumar, S.; Grumet, M. Trends in mesenchymal stem cell clinical trials 2004-2018: Is efficacy optimal in a narrow dose range? Stem Cells Transl Med 2020, 9, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtzberg, J.; Prockop, S.; Teira, P.; Bittencourt, H.; Lewis, V.; Chan, K.W.; Horn, B.; Yu, L.; Talano, J.A.; Nemecek, E.; et al. Allogeneic human mesenchymal stem cell therapy (remestemcel-L, Prochymal) as a rescue agent for severe refractory acute graft-versus-host disease in pediatric patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014, 20, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.T.; Lee, S.H.; Yoon, H.S.; Heo, J.H.; Lee, S.B.; Byun, J.W.; Shin, J.; Cho, Y.K.; Chung, E.; Jeon, M.S.; et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of intravenous injection of clonal mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow in five adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol 2021, 48, 1236–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo Cicero, A.; Nissan, X. Pluripotent stem cells to model Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS): Current trends and future perspectives for drug discovery. Ageing Res Rev 2015, 24, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Lian, Q.; Zhu, G.; Zhou, F.; Sui, L.; Tan, C.; Mutalif, R.A.; Navasankari, R.; Zhang, Y.; Tse, H.F.; et al. A human iPSC model of Hutchinson Gilford Progeria reveals vascular smooth muscle and mesenchymal stem cell defects. Cell Stem Cell 2011, 8, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavasani, M.; Robinson, A.R.; Lu, A.; Song, M.; Feduska, J.M.; Ahani, B.; Tilstra, J.S.; Feldman, C.H.; Robbins, P.D.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; et al. Muscle-derived stem/progenitor cell dysfunction limits healthspan and lifespan in a murine progeria model. Nat Commun 2012, 3, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Z.M.; Choi, J.Y.; Wang, K.; Zhang, H.; Tariq, Z.; Wu, D.; Ko, E.; LaDana, C.; Sesaki, H.; Cao, K. Methylene blue alleviates nuclear and mitochondrial abnormalities in progeria. Aging Cell 2016, 15, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaffidi, P.; Misteli, T. Lamin A-dependent misregulation of adult stem cells associated with accelerated ageing. Nat Cell Biol 2008, 10, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.H.; Barkho, B.Z.; Ruiz, S.; Diep, D.; Qu, J.; Yang, S.L.; Panopoulos, A.D.; Suzuki, K.; Kurian, L.; Walsh, C.; et al. Recapitulation of premature ageing with iPSCs from Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. Nature 2011, 472, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).