Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Curation

2.2. Methods

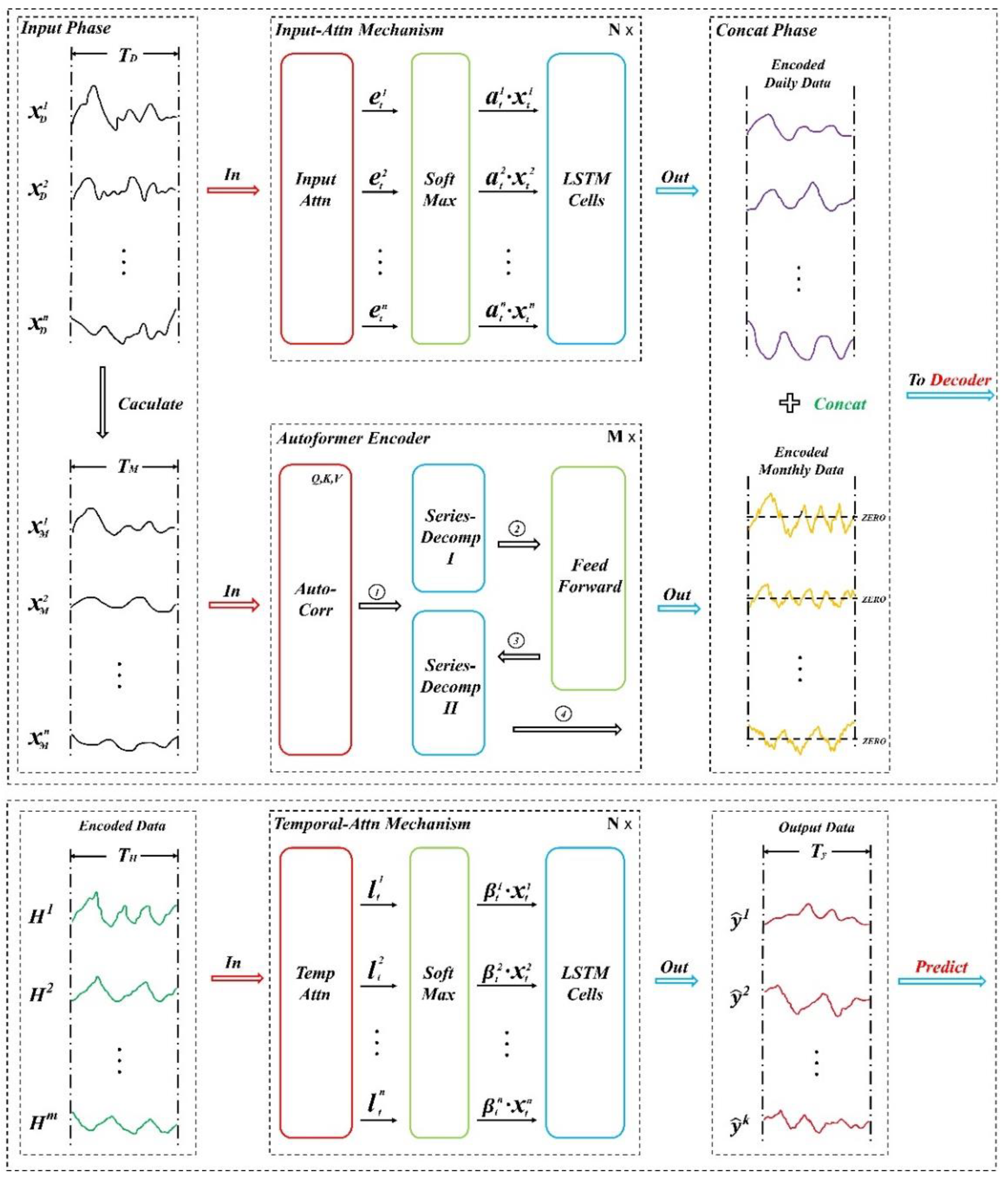

2.2.1. Encoder

2.2.2. Decoder

2.2.3. Metric

3. Results

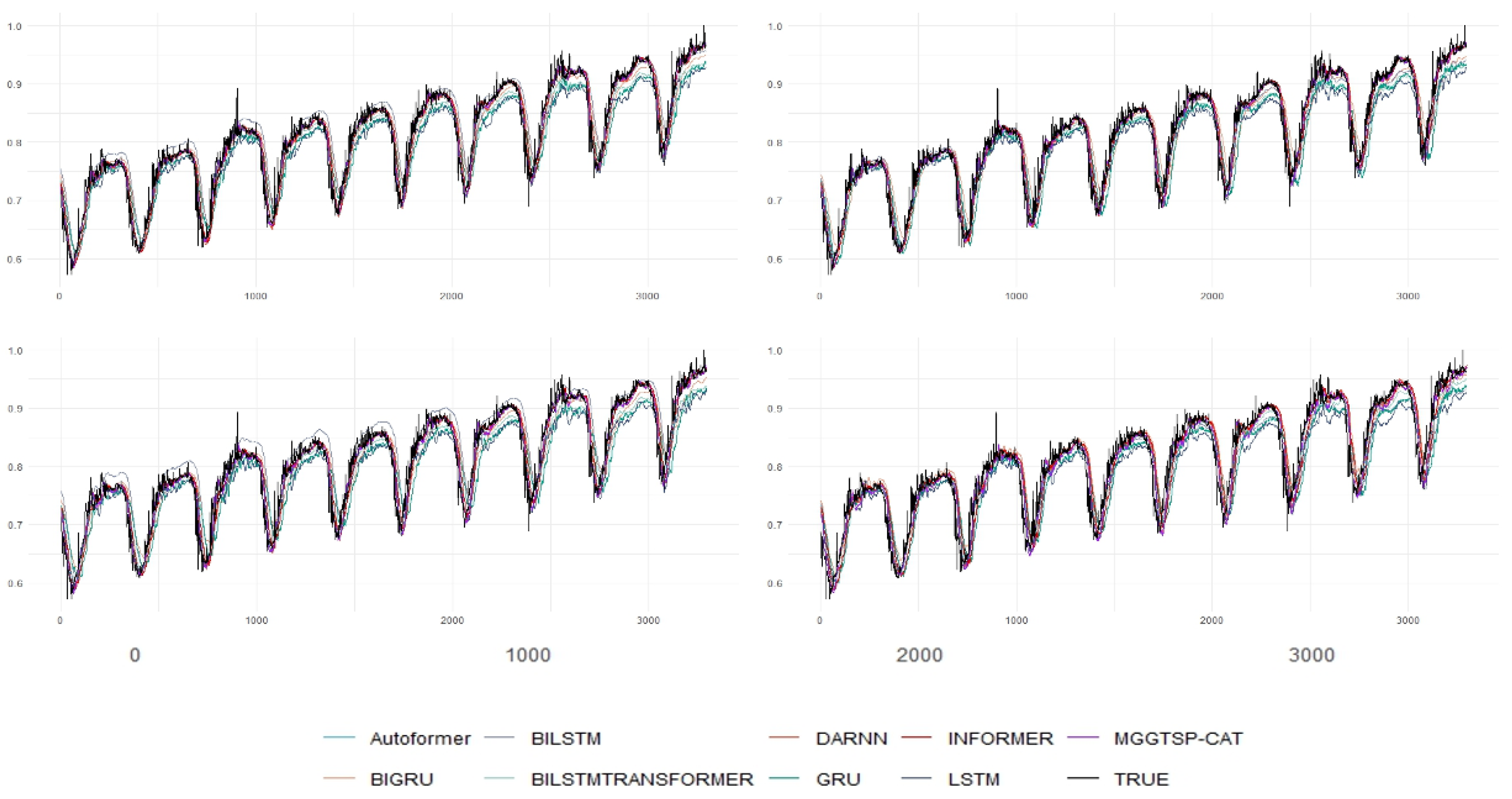

3.1. Overall Performances

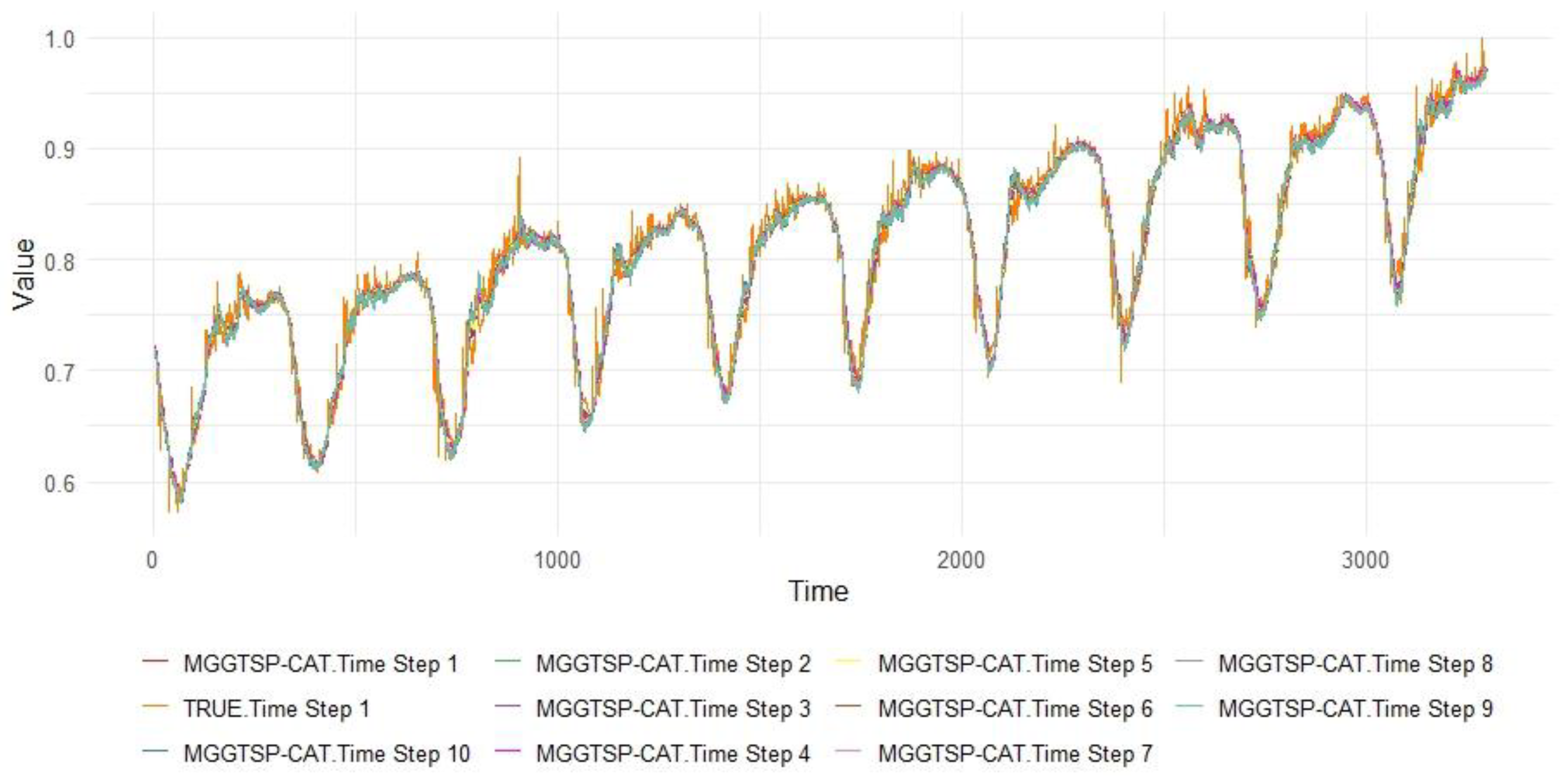

3.2. Single Step

3.3. Robustness Against Baseline Models

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

- 1)

- A greenhouse gas dataset covering multiple global major climate monitoring stations was created. The data is sourced from long-term monitoring stations in Mauna Loa (Hawaii), Barrow (Alaska), American Samoa, and Antarctica, spanning over half a century [22]. This dataset not only offers high temporal resolution (daily data) but also effectively reflects global climate change trends, providing a solid experimental foundation for cross-scale climate forecasting.

- 2)

- An innovative fusion of the model's time resolution with the characteristics of greenhouse gas data. This study designs a multi-encoder fusion architecture that integrates the characteristics of different time resolution data. The Input Attention Mechanism and Autoformer Encoder are used to extract features from daily and monthly data, respectively, while the Temporal Attention Mechanism further enhances the model’s ability to integrate information across different time scales. This method effectively captures the multi-scale features of greenhouse gas concentration changes, improving the model’s adaptability and accuracy in both short-term and long-term climate predictions.

- 3)

- Exceptional accuracy and stability of the model. The experimental results show that the proposed model exhibits outstanding performance in prediction tasks across multiple climate monitoring stations, especially in high-variability daily data. The model can accurately capture key change patterns and provide stable and reliable predictions. For both short-term and long-term predictions at different time scales, the model performs excellently, showing less fluctuation in prediction results and significantly improving stability compared to other existing methods.

- 4)

- Future research could further extend the application of the model by considering more types of greenhouse gas monitoring data and a wider range of geographical areas. The effectiveness and generalization ability of the model under different climate conditions could be explored. Additionally, the model could be applied to the prediction of various climate events, further enhancing its predictive accuracy and practical application value.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barnett, J. Security and Climate Change. Global Environmental Change 2003, 13, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adedeji, O.; Reuben, O.; Olatoye, O. Global Climate Change. Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection 2014, 2, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffry, L.; Ong, M.Y.; Nomanbhay, S.; Mofijur, M.; Mubashir, M.; Show, P.L. Greenhouse Gases Utilization: A Review. Fuel 2021, 301, 121017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledley, T.S.; Sundquist, E.T.; Schwartz, S.E.; Hall, D.K.; Fellows, J.D.; Killeen, T.L. Climate Change and Greenhouse Gases. Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union 1999, 80, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selin, H.; VanDeveer, S.D. Political Science and Prediction: What’s Next for U.S. Climate Change Policy? Review of Policy Research 2007, 24, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patnaik, S. A Cross-Country Study of Collective Political Strategy: Greenhouse Gas Regulations in the European Union. J Int Bus Stud 2019, 50, 1130–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narang, R.; Khan, A.M.; Goyal, R.; Gangopadhyay, S. Harnessing Data Analytics and Machine Learning to Forecast Greenhouse Gas Emissions. European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers, 14 November 2023; 2023, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kasatkin, A.J.; Krinitskiy, M.A. Machine Learning Techniques for Anomaly Detection in High-Frequency Time Series of Wind Speed and Greenhouse Gas Concentration Measurements. Moscow Univ. Phys. 2023, 78, S138–S148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami Javanmard, M.; Ghaderi, S.F. A Hybrid Model with Applying Machine Learning Algorithms and Optimization Model to Forecast Greenhouse Gas Emissions with Energy Market Data. Sustainable Cities and Society 2022, 82, 103886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.M.; Cusack, S.; Colman, A.W.; Folland, C.K.; Harris, G.R.; Murphy, J.M. Improved Surface Temperature Prediction for the Coming Decade from a Global Climate Model. Science 2007. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Liang, L.; Wang, C.; Wu, Y.; Yang, F.; Rong, M. Prediction of the Electrical Strength and Boiling Temperature of the Substitutes for Greenhouse Gas SF₆ Using Neural Network and Random Forest. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 124204–124216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Wei, R.; Xu, L.; Ding, X. A Method for Modelling Greenhouse Temperature Using Gradient Boost Decision Tree. Information Processing in Agriculture 2022, 9, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, R.; Zhang, M.; Huang, Y.; Hu, J.; Peng, J. Measuring the Critical Influence Factors for Predicting Carbon Dioxide Emissions of Expanding Megacities by XGBoost. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sak, H.; Senior, A.; Beaufays, F. Long Short-Term Memory Recurrent Neural Network Architectures for Large Scale Acoustic Modeling. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2014; ISCA, 14 September 2014; pp. 338–342. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Cai, Y.; Huang, H.; Li, A.; Yang, L.; Zhou, C. A CNN-LSTM Model for Soil Organic Carbon Content Prediction with Long Time Series of MODIS-Based Phenological Variables. Remote Sensing 2022, 14, 4441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panja, M.; Chakraborty, T.; Biswas, A.; Deb, S. E-STGCN: Extreme Spatiotemporal Graph Convolutional Networks for Air Quality Forecasting; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Yuan, Q.; Zhou, C.; Chen, X.; Xuan, D.; Song, J. Carbon Emissions Forecasting Based on Temporal Graph Transformer-Based Attentional Neural Network. Journal of Computational Methods in Sciences and Engineering 2024, 24, 1405–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewage, P.; Behera, A.; Trovati, M.; Pereira, E.; Ghahremani, M.; Palmieri, F.; Liu, Y. Temporal Convolutional Neural (TCN) Network for an Effective Weather Forecasting Using Time-Series Data from the Local Weather Station. Soft Comput 2020, 24, 16453–16482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Song, D.; Chen, H.; Cheng, W.; Jiang, G.; Cottrell, G. A Dual-Stage Attention-Based Recurrent Neural Network for Time Series Prediction; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Xu, J.; Wang, J.; Long, M. Autoformer: Decomposition Transformers with Auto-Correlation for Long-Term Series Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc., 2021; Vol. 34; pp. 22419–22430. [Google Scholar]

- Thoning, K.W.; Crotwell, A.M.; Mund, J.W. Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Dry Air Mole Fractions from continuous measurements at Mauna Loa, Hawaii, Barrow, Alaska, American Samoa and South Pole, 1973-present. Version 2024-08-15; National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Global Monitoring Laboratory (GML): Boulder, Colorado, USA, 2024; Volume -15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Model | Test_MSE | Test_MAE | Test_R² | Test_MAPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGGTSP | 0.0002878 | 0.0116377 | 0.9627339 | 0.0147310 |

| DARNN | 0.0003716 | 0.0131211 | 0.9518857 | 0.0167605 |

| Autoformer | 0.0004013 | 0.0136400 | 0.9480379 | 0.0174719 |

| TCN | 0.0004571 | 0.0146228 | 0.9408147 | 0.0187982 |

| BiTransfomer_LSTM | 0.0005962 | 0.0184426 | 0.9227868 | 0.0231243 |

| Informer | 0.0006874 | 0.0182407 | 0.9109833 | 0.0236269 |

| LSTM | 0.0008636 | 0.0243913 | 0.8881612 | 0.0295327 |

| Bi_GRU | 0.0012059 | 0.0257306 | 0.8438375 | 0.0333236 |

| Bi_LSTM | 0.0012679 | 0.0260454 | 0.8358032 | 0.0338971 |

| GRU | 0.0012723 | 0.0292467 | 0.8352157 | 0.0367302 |

| RNN | 0.0013303 | 0.0306885 | 0.8276975 | 0.0373433 |

| CNN1D | 0.0018290 | 0.0351233 | 0.7631485 | 0.0422021 |

| Bi_RNN | 0.0025301 | 0.0413129 | 0.6723005 | 0.0485256 |

| CNN1D_LSTM | 0.0028931 | 0.0447957 | 0.6253179 | 0.0527006 |

| ANN | 0.0043728 | 0.0612601 | 0.4336226 | 0.0744804 |

| Model | STEP1 | STEP2 | STEP3 | STEP4 | STEP5 | STEP6 | STEP7 | STEP8 | STEP9 | STEP10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGGTSP | 0.97878 | 0.97443 | 0.97074 | 0.96684 | 0.96564 | 0.96125 | 0.95805 | 0.95458 | 0.95005 | 0.94698 |

| DARNN | 0.97102 | 0.96757 | 0.96023 | 0.95383 | 0.95822 | 0.94851 | 0.94829 | 0.94355 | 0.93422 | 0.93341 |

| Autoformer | 0.96930 | 0.96559 | 0.95608 | 0.94813 | 0.95578 | 0.94324 | 0.94548 | 0.93990 | 0.92843 | 0.92844 |

| TCN | 0.96514 | 0.96146 | 0.94898 | 0.93800 | 0.95049 | 0.93385 | 0.93957 | 0.93361 | 0.91780 | 0.91926 |

| BiTransfomer _LSTM |

0.94296 | 0.92876 | 0.93205 | 0.92333 | 0.91395 | 0.94672 | 0.90693 | 0.91436 | 0.91156 | 0.90723 |

| Informer | 0.94596 | 0.94410 | 0.92072 | 0.89425 | 0.92664 | 0.89500 | 0.91480 | 0.90963 | 0.87846 | 0.88027 |

| LSTM | 0.91190 | 0.90502 | 0.90029 | 0.88391 | 0.89488 | 0.90956 | 0.88113 | 0.85724 | 0.86588 | 0.87179 |

| Bi_GRU | 0.88297 | 0.83717 | 0.90740 | 0.88788 | 0.84569 | 0.76714 | 0.91339 | 0.78506 | 0.74577 | 0.86590 |

| Bi_LSTM | 0.85418 | 0.92533 | 0.88067 | 0.78546 | 0.82317 | 0.80695 | 0.76901 | 0.85771 | 0.80601 | 0.84954 |

| GRU | 0.85939 | 0.84737 | 0.86361 | 0.88095 | 0.79092 | 0.82703 | 0.83580 | 0.79108 | 0.85289 | 0.80312 |

| RNN | 0.85730 | 0.84250 | 0.84315 | 0.82455 | 0.82357 | 0.82105 | 0.80826 | 0.81793 | 0.82042 | 0.81823 |

| CNN1D | 0.79477 | 0.79974 | 0.86495 | 0.76666 | 0.71630 | 0.78686 | 0.73372 | 0.79676 | 0.71642 | 0.65530 |

| Bi_RNN | 0.72101 | 0.70851 | 0.72330 | 0.66788 | 0.61899 | 0.65601 | 0.62097 | 0.69373 | 0.66151 | 0.65108 |

| CNN1D_LSTM | 0.70959 | 0.63854 | 0.65612 | 0.62404 | 0.70758 | 0.59694 | 0.67335 | 0.53487 | 0.60110 | 0.51105 |

| ANN | 0.51734 | 0.44780 | 0.37191 | 0.43568 | 0.46613 | 0.43010 | 0.44904 | 0.45915 | 0.47785 | 0.28123 |

| Model | STEP1 | STEP2 | STEP3 | STEP4 | STEP5 | STEP6 | STEP7 | STEP8 | STEP9 | STEP10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGGTSP | 0.000163 | 0.000197 | 0.000226 | 0.000256 | 0.000265 | 0.000299 | 0.000324 | 0.000351 | 0.000386 | 0.000410 |

| DARNN | 0.000223 | 0.000250 | 0.000307 | 0.000356 | 0.000322 | 0.000398 | 0.000400 | 0.000436 | 0.000509 | 0.000515 |

| Autoformer | 0.000236 | 0.000265 | 0.000339 | 0.000400 | 0.000341 | 0.000438 | 0.000421 | 0.000465 | 0.000553 | 0.000554 |

| TCN | 0.000268 | 0.000297 | 0.000393 | 0.000478 | 0.000382 | 0.000511 | 0.000467 | 0.000513 | 0.000636 | 0.000625 |

| BiTransfomer_LSTM | 0.000439 | 0.000549 | 0.000524 | 0.000591 | 0.000664 | 0.000411 | 0.000719 | 0.000662 | 0.000684 | 0.000718 |

| Informer | 0.000416 | 0.000431 | 0.000611 | 0.000816 | 0.000566 | 0.000811 | 0.000658 | 0.000699 | 0.000940 | 0.000926 |

| LSTM | 0.000678 | 0.000732 | 0.000769 | 0.000896 | 0.000811 | 0.000698 | 0.000919 | 0.001104 | 0.001037 | 0.000992 |

| Bi_GRU | 0.000901 | 0.001255 | 0.000714 | 0.000865 | 0.001191 | 0.001798 | 0.000669 | 0.001662 | 0.001966 | 0.001037 |

| Bi_LSTM | 0.001123 | 0.000575 | 0.000920 | 0.001655 | 0.001365 | 0.001491 | 0.001785 | 0.001100 | 0.001500 | 0.001164 |

| GRU | 0.001083 | 0.001176 | 0.001052 | 0.000918 | 0.001614 | 0.001336 | 0.001269 | 0.001615 | 0.001138 | 0.001523 |

| RNN | 0.001099 | 0.001214 | 0.001209 | 0.001354 | 0.001362 | 0.001382 | 0.001482 | 0.001407 | 0.001389 | 0.001406 |

| CNN1D | 0.001581 | 0.001543 | 0.001041 | 0.001800 | 0.002190 | 0.001646 | 0.002058 | 0.001571 | 0.002193 | 0.002667 |

| Bi_RNN | 0.002149 | 0.002246 | 0.002133 | 0.002562 | 0.002941 | 0.002657 | 0.002929 | 0.002368 | 0.002618 | 0.002699 |

| CNN1D_LSTM | 0.002237 | 0.002785 | 0.002651 | 0.002900 | 0.002257 | 0.003113 | 0.002524 | 0.003596 | 0.003085 | 0.003783 |

| ANN | 0.003717 | 0.004255 | 0.004843 | 0.004354 | 0.004121 | 0.004401 | 0.004257 | 0.004181 | 0.004038 | 0.005561 |

| Model | STEP1 | STEP2 | STEP3 | STEP4 | STEP5 | STEP6 | STEP7 | STEP8 | STEP9 | STEP10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGGTSP | 0.008435 | 0.009374 | 0.010210 | 0.010994 | 0.011186 | 0.012021 | 0.012577 | 0.013206 | 0.013918 | 0.014457 |

| DARNN | 0.010061 | 0.010630 | 0.011907 | 0.012869 | 0.012302 | 0.013680 | 0.013829 | 0.014469 | 0.015657 | 0.015807 |

| Autoformer | 0.010274 | 0.010891 | 0.012558 | 0.013691 | 0.012639 | 0.014409 | 0.014199 | 0.014928 | 0.016397 | 0.016415 |

| TCN | 0.010958 | 0.011553 | 0.013643 | 0.015087 | 0.013372 | 0.015661 | 0.014940 | 0.015786 | 0.017707 | 0.017521 |

| Informer | 0.013944 | 0.014224 | 0.017385 | 0.020133 | 0.016555 | 0.020105 | 0.018042 | 0.018612 | 0.021806 | 0.021601 |

| BiTransfomer _LSTM |

0.016098 | 0.018339 | 0.017876 | 0.018638 | 0.020110 | 0.013880 | 0.020849 | 0.019472 | 0.019489 | 0.019675 |

| LSTM | 0.021328 | 0.022347 | 0.022861 | 0.024917 | 0.023618 | 0.021431 | 0.025366 | 0.028250 | 0.027284 | 0.026510 |

| Bi_GRU | 0.022423 | 0.026983 | 0.021235 | 0.022717 | 0.026333 | 0.032263 | 0.019261 | 0.030710 | 0.032259 | 0.023122 |

| Bi_LSTM | 0.024449 | 0.017924 | 0.022438 | 0.029404 | 0.027164 | 0.028833 | 0.031595 | 0.024125 | 0.027837 | 0.026685 |

| GRU | 0.027698 | 0.027475 | 0.026573 | 0.025132 | 0.033664 | 0.030206 | 0.029865 | 0.032262 | 0.028023 | 0.031569 |

| RNN | 0.027605 | 0.029178 | 0.029061 | 0.030809 | 0.031127 | 0.031362 | 0.032624 | 0.031747 | 0.031580 | 0.031791 |

| CNN1D | 0.032972 | 0.032569 | 0.026367 | 0.035236 | 0.038554 | 0.033392 | 0.037443 | 0.033172 | 0.038725 | 0.042803 |

| Bi_RNN | 0.037570 | 0.038244 | 0.037586 | 0.041467 | 0.044881 | 0.042510 | 0.044928 | 0.040119 | 0.042524 | 0.043299 |

| CNN1D_LSTM | 0.038234 | 0.043631 | 0.042643 | 0.044788 | 0.038907 | 0.046889 | 0.041832 | 0.051089 | 0.047142 | 0.052802 |

| ANN | 0.057103 | 0.060965 | 0.065537 | 0.061544 | 0.059535 | 0.061573 | 0.060271 | 0.059627 | 0.057873 | 0.068573 |

| Model | STEP1 | STEP2 | STEP3 | STEP4 | STEP5 | STEP6 | STEP7 | STEP8 | STEP9 | STEP10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MGGTSP | 0.010664 | 0.011856 | 0.012908 | 0.013898 | 0.014153 | 0.015210 | 0.015928 | 0.016728 | 0.017639 | 0.018326 |

| DARNN | 0.012742 | 0.013492 | 0.015195 | 0.016444 | 0.015651 | 0.017497 | 0.017647 | 0.018523 | 0.020128 | 0.020286 |

| Autoformer | 0.013061 | 0.013875 | 0.016077 | 0.017557 | 0.016118 | 0.018489 | 0.018148 | 0.019151 | 0.021127 | 0.021117 |

| TCN | 0.013990 | 0.014770 | 0.017531 | 0.019441 | 0.017128 | 0.020177 | 0.019164 | 0.020293 | 0.022875 | 0.022614 |

| BiTransfomer _LSTM |

0.019778 | 0.022580 | 0.022051 | 0.023331 | 0.025092 | 0.017770 | 0.026130 | 0.024649 | 0.024767 | 0.025097 |

| Informer | 0.017983 | 0.018345 | 0.022511 | 0.026143 | 0.021399 | 0.026094 | 0.023321 | 0.024085 | 0.028329 | 0.028060 |

| LSTM | 0.025587 | 0.026832 | 0.027559 | 0.030017 | 0.028598 | 0.026056 | 0.030931 | 0.034351 | 0.033116 | 0.032278 |

| Bi_GRU | 0.028922 | 0.034812 | 0.027270 | 0.028817 | 0.033980 | 0.042075 | 0.024814 | 0.040054 | 0.042387 | 0.030106 |

| Bi_LSTM | 0.032075 | 0.022765 | 0.029086 | 0.038758 | 0.035504 | 0.037625 | 0.041396 | 0.031411 | 0.036513 | 0.033838 |

| GRU | 0.034505 | 0.034609 | 0.033364 | 0.031164 | 0.042297 | 0.037924 | 0.037472 | 0.041016 | 0.035105 | 0.039846 |

| RNN | 0.033020 | 0.035437 | 0.035304 | 0.037536 | 0.037904 | 0.038326 | 0.039871 | 0.038640 | 0.038453 | 0.038941 |

| CNN1D | 0.039474 | 0.038810 | 0.032060 | 0.042228 | 0.046183 | 0.040666 | 0.045155 | 0.039777 | 0.046488 | 0.051180 |

| Bi_RNN | 0.043991 | 0.044804 | 0.044306 | 0.048538 | 0.052553 | 0.049851 | 0.052712 | 0.047334 | 0.050156 | 0.051010 |

| CNN1D_LSTM | 0.044628 | 0.051063 | 0.050001 | 0.052544 | 0.045748 | 0.055173 | 0.049362 | 0.060271 | 0.055763 | 0.062453 |

| ANN | 0.069636 | 0.074062 | 0.079720 | 0.074864 | 0.072489 | 0.074870 | 0.073280 | 0.072609 | 0.070289 | 0.082984 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).