1. Introduction

Major oils typically lack a high abundance of oleic acid. To meet market demands, significant research has focused on developing high-oleic soy, rapeseed, and camelina oils, primarily through genetic modifications and, more recently, gene editing [

1]. In the context of oil palms, interspecific OxG hybrids were developed through conventional breeding to address bud rot disease. Some of these cultivars exhibit high oleic genotypes, resulting in hybrids that produce oil with over 55% oleic acid content and 33% saturated fatty acid content [

2,

3]. These OxG hybrids are a product of crossing the American oil palm (

Elaeis oleifera) with the African oil palm (

Elaeis guineensis) and constitute 12% of the total oil palm plantation area in Colombia [

4]. Notably, these hybrids are highly productive, with an average production of 38 metric tons per hectare per year of fresh fruit bunches (FFB) in certain regions of Colombia, and some plantations achieving nearly 45 metric tons per hectare per year [

5]. In addition to their high productivity and superior oil quality, OxG hybrids exhibit a slow growth rate. However, they require assisted pollination using pollen from E. guineensis to produce well-formed bunches with oil content comparable to

E. guineensis cultivars [

6]. This necessary assisted pollination is both expensive and labor-intensive, accounting for approximately 18% of the crop’s total annual cost, which negatively impacts the crop’s economic viability [

7]. Tissue culture techniques, including large-scale micropropagation, have been explored to address these limitations, ensuring the efficient multiplication of high-quality planting materials [

8]. Recent genomic and agronomic studies further enhance understanding of OxG hybrid performance under diverse environmental conditions, solidifying its role as a sustainable crop. The oil derived from OxG hybrids has garnered attention due to its unique composition and broad industrial applicability. High oleic acid content, reduced saturated fat levels, and excellent oxidative stability make the OxG oil particularly valuable for food processing, cosmetics, and biodiesel production [

2,

9,

10]. In the premium market segment, the oil meets rising consumer demand for healthier edible oils, especially in health-conscious markets. Its oxidative stability extends the shelf life of processed foods and makes it suitable for high-temperature cooking, a critical feature for industrial and household applications [

10]. Globally, OxG oil production is concentrated in Latin America, with Colombia, Brazil, and Ecuador leading the supply chain. These countries capitalize on the hybrid’s resilience to local diseases and environmental challenges.

The rising demand for high-oleic palm oil has further highlighted the need for sustainable alternatives to tropical oil crops. Microbial fermentation, particularly utilizing microalgae such as

Prototheca moriformis, offers a transformative solution. Our recent advancements [

11,

12] underscore the remarkable versatility of

P. moriformis as a technology and production platform, capable of generating oils with diverse compositions tailored for specific industrial applications. By employing genetic engineering and/or classical strain optimization,

P. moriformis has proven to be a scalable and efficient lipid production platform in both temperate and tropical regions alike such as Brazil, the United States, Canada, Japan, and Europe.

Our research group demonstrated [

11] that

P. moriformis strains could be genetically engineered to produce oils mimicking human milk fat, achieving precise incorporation of palmitic acid into the

sn-2 position of triacylglycerols (TAG). Their process consistently achieved oil yields exceeding 150 g/L of fermentation broth, highlighting its industrial scalability. Similarly, we optimized

P. moriformis for high-oleic acid production, enhancing oleic acid levels to over 85% of total fatty acids and maintaining high oil productivity of up to 145 g/L [

12]. These studies illustrate the flexibility of

P. moriformis to produce oils with diverse functional properties, such as high-oleic oils and structured lipids, depending on the specific engineering strategy employed. The scalability and robustness of

P. moriformis, demonstrated through fermentation trials further emphasize its suitability for industrial applications. The platform’s ability to utilize various carbon sources and adapt to large-scale processes positions

P. moriformis as a relevant technology in the sustainable production of high-value oils for applications in food, cosmetics, biofuels, and specialty chemicals.

This study aims to leverage the P. moriformis platform, applying classical strain optimization techniques, to develop a strain capable of producing an oil with a fatty acid and TAG composition comparable to high-oleic palm oil. By tailoring the fatty acid profile and ensuring industrial scalability, this research seeks to reduce reliance on tropical oil crops, thereby mitigating environmental concerns such as deforestation and biodiversity loss. The resulting high-oleic algal oil holds the potential to meet the rigorous functional and nutritional requirements of diverse industries.

2. Materials and Methods

Palm oil samples: Crude high-oleic palm oil sample has been obtained from Palmas de Tumaco (Bogotá, Colombia). Conventional red palm oil was obtained in a local grocery store (San Francisco, California).

Strain development. P. moriformis wild-type strain isolate UTEX 1533 was received from the University of Texas (Austin, TX) and classical strain improvement initiated from a baseline of 28% and 60% palmitic and oleic acids, respectively (

Table 1). The experimental process to develop the high-oleic palm oil alternative strain from the parental strain involved several optimization techniques targeting lipid productivity and fatty acid profiles. Initially, the parental strain was chemically mutagenized using 44 μM 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide (4-NQO) at 32°C for 30 minutes. The mutagen was neutralized with sodium thiosulfate and removed by washing. Following recovery in limited sugar media, the cells were cultured in lipid production media at 38°C for five days, a temperature higher than optimal to stress the cells and select for mutants predisposed to higher palmitate production. Surviving cells were then subjected to a heat shock at 65°C for 4 minutes, which eliminated more than 99% of the population, allowing selection of mutants. The resulting sub-clones were screened successively for high glucose consumption within lipid production media using a hexose kinase based microtiter plate assay (e.g., ThermoScientific#TR15421), followed by a high-throughput FAME assay to screen for fatty acid profiles among the more limited selection of high glucose consuming subclones. These clones underwent additional rounds of serial passaging and phenotypic stability assessment to refine the desired traits. After five rounds, a stable strain, designated as the high-oleic palm oil alternative strain, was identified. This strain demonstrated improved lipid production metrics, including enhanced oil content, dry cell weight, and lipid titer, alongside a significant increase in palmitate levels compared to the parental strain (see

Table 1).

Culture media composition. Cultured conditions and media used has been described in a previous paper [

12]. Briefly, vegetative growth medium was comprised of macronutrients including NaH2PO4, K2HPO4, Citric acid monohydrate, Magnesium sulfate heptahydrate, Calcium chloride dihydrate, and dextrose at 1.64, 1.98, 1.05, 1.23, 0.02 and 40 g/L, respectively. Ammonium sulfate served as the sole nitrogen source at 1.0 g/L. Antifoam (Sigma 204, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, Missouri, USA) was added to a final concentration of 0.225 mL/L. Trace minerals were prepared as a 1000 X stock solution comprised of boric acid, zinc sulfate heptahydrate, manganese sulfate monohydrate, sodium molybdate dihydrate, nickel nitrate heptahydrate, citric acid monohydrate, copper (II) sulfate pentahydrate, and Iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate at 0.91, 1.76, 1.23, 0.05, 0.04, 20.49, 0.05, and 0.75 g/L, respectively. A 1000 X vitamin stock was comprised of thiamine HCl, D-pantothenic acid hemicalcium salt, biotin, cyanocobalamin, riboflavin, and pyridoxine HCl at 3.0, 0.16, 0.0048, 0.00034, 0.015, and 0.0078 g/L, respectively. Lipid production medium was identical to vegetative growth medium except that ammonium sulfate was supplied at 0.2 g/L. All solutions were filter sterilized prior to use.

Production of algae oil. The production process was scaled from 1 L and 20 L reactor scale essentially as described previously [

12], followed by drying of algal fermentation broth on a double drum dryer (Buflovak Model ADDD operating at 70 psig steam, 1200 rpm; Buflovak, Tonawanda, NY, USA), and subsequent mechanical/solvent extraction utilizing a 6:1 hexane to biomass ratio carried out for up to 6 hours on an MSE Pro planetary ball mill (10L capacity). Micellae resulting from solvent extraction were subsequently roto-vaped to remove hexane, followed by degumming using citric acid (0.2% wt:wt of a 50% solution) at 130 °C for 10 minutes with agitation. Removal of gums was carried out by centrifugation at 3,000 rpm for 10 minutes, after which the de-gummed oil was decanted. This was followed by bleaching under vacuum (27 in Hg 685.8 mm Hg) and temperature (90-110 °C) using 2% (wt:wt) bentonite bleaching earth. Bleaching clay and oil were separated by filtration under vacuum followed by steam deodorization under vacuum (< 25 in Hg (or 635 mm Hg) at 200 °C for 90 minutes) resulting in refined, bleached and deodorized (RBD) oil. Typical fermentation results obtained at 1 and 20 and 50 L scales are provided in

Table 1. Fermentation conditions utilized, an inoculation volume of 0.25-0.3% of the fermenter volume, pH and dissolved oxygen (DO) setpoints of 5.5-6.0 and 30%, respectively. The operating temperature was 28 °C throughout with aeration and agitation managed to maintain DO. Fermentation medium was fortified to support higher cell density as follows. Medium composition remained the same, however vitamin and trace metals solutions were increased 10 and 15-fold, respectively. Micronutrients (sodium phosphate, potassium phosphate, citric acid monohydrate, magnesium sulfate heptahydrate, and calcium chloride dihydrate) were increased to 7.13, 9.25, 2.1, 17.33, and 0.8 g/L, respectively. Glucose feed was a 55% wt:wt sterile solution.

Fatty acid (FA) analysis. Fatty acid composition of algal and high-oleic palm oil samples were measured as their fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) following direct transesterification with a sulfuric acid methanol solution [

12]. Samples were injected on an Agilent 8890 gas chromatograph system equipped with a split/splitless inlet and a flame ionization detector (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA). An Agilent DB-WAX column (30 m × 0.32 mm × 0.25 um dimensions) was used for the chromatographic separation of the FAME peaks. A FAME standard mixture purchased from Nu-Chek Prep (Nu-Chek Prep Inc., Elysian, MN, USA) was injected to establish retention times. Response factor corrections were determined empirically previously using various standard mixtures from Nu-Chek Prep. Methyl nonadecanoate (19:0) was used as an internal standard for quantitation of individual FAMEs.

Triacylglycerols (TAG) and Diacylglycerols (DAG) analysis. TAG profiles were determined as described previously using an Agilent 1290 Infinity II UHPLC system coupled to a 6470B triple quadrupole mass spectrometer and APCI ionization source according to the parameters described previously [

11,

13]. Diacylglycerol (DAG) ion ratios were used to assess the relative abundance of TAG regio-isomers, and quantification was performed using a calibration curve of pure standards.

3. Results

3.1. Development of High-Oleic Palm Oil Alternative Strain

To develop the high-oleic palm oil alternative strain from the parental strain, a classical strain improvement strategy was employed. The parental strain cells were chemically mutagenized using 44 μM 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide (4-NQO) at 32°C for 30 minutes, followed by neutralization with sodium thiosulfate and recovery in limited sugar media. Cells were cultured in lipid production media at 38°C for five days to induce stress conditions and select for mutants with improved lipid production. A subsequent heat shock at 65°C for 4 minutes eliminated over 99% of the population, allowing the selection of robust mutants. Surviving clones were subjected to high-throughput screening for glucose consumption and fatty acid profiles, with selected clones undergoing multiple rounds of passaging to ensure phenotypic stability. The optimized high-oleic palm oil alternative strain exhibited a significant increase in palmitic acid content at the sn-1(3) position of TAG as observed in the parental strain. Fermentation performance demonstrated enhanced oil content and improved lipid production metrics, including increased lipid titer and dry cell weight, establishing its superior capability for industrial-scale lipid synthesis.

3.2. Fermentation Trials

The high-oleic palm oil alternative algal strain, developed from a base strain of

Prototheca moriformis through classical strain optimization, exhibited remarkable robustness in fermentation performance across diverse conditions (

Table 1). The optimized strain consistently delivered elevated oil yields and maintained high productivity metrics. Comparative analyses revealed an average palmitic acid of 30.71% and oleic acid content of 56.4% of total fatty acids (FA) and an average oil content of 69.45% of dry cell weight (DCW), surpassing the base strain in oil titer and productivity (

Table 1). Across multiple fermentation runs, the dry cell weight ranged from 186.3 to 204 g/kg, with an average oil titer of 136.5 g/L and a low coefficient of variation (3.88%), emphasizing the strain’s reliability. These results highlight the strain’s robustness, achieved through iterative optimization, and its potential to serve as a sustainable and efficient alternative for high-oleic palm oil production.

3.3. Fatty Acid (FA) and Triacylglycerol (TAG) Profile

High-oleic palm oil exhibits a fatty acid profile characterized by a significantly higher concentration of oleic acid (18:1 n-9, 49.21%) compared to regular palm oil (39.07%), while having substantially lower palmitic acid (16:0) content with 32.71% versus 42.83% (

Table 2). This profile highlights its enhanced unsaturated-to-saturated fatty acid ratio, making it a healthier alternative [Riley]. The fatty acid composition of the high-oleic palm oil alternative algae strain closely mirrors that of high-oleic palm oil. The high-oleic palm oil algal alternative strain achieved an oleic acid content ranging from 55 to 57%, exceeding that of high-oleic palm oil, while maintaining a comparable level of palmitic acid (30-32%,

Table 1 and 2). Furthermore, the algal strain displayed a balanced unsaturated fatty acid content of 63.57%, closely aligned with the 62.96% observed in high-oleic palm oil, and both significantly surpassing the 50.07% of regular palm oil (

Table 2). The total saturated fatty acid levels of the algal strain (36.21%) and high-oleic palm oil (36.86%) are also nearly identical, confirming the strain’s potential to replicate the desired properties of high-oleic palm oil (

Table 2).

This close compositional alignment underscores the effectiveness of the algal strain as an alternative to high-oleic palm oil.

The TAG profile of high-oleic palm oil differs notably from regular palm oil, with a significantly higher proportion of unsaturated-unsaturated-unsaturated (Unsat-Unsat-Unsat) TAG species (20.32% vs. 9.39%) and lower levels of saturated-saturated-saturated (Sat-Sat-Sat) TAG species (0.75% vs. 4.99%, see

Table 3). This reflects the enhanced unsaturation characteristic of high-oleic palm oil, contributing to its improved functional and nutritional qualities [

14].

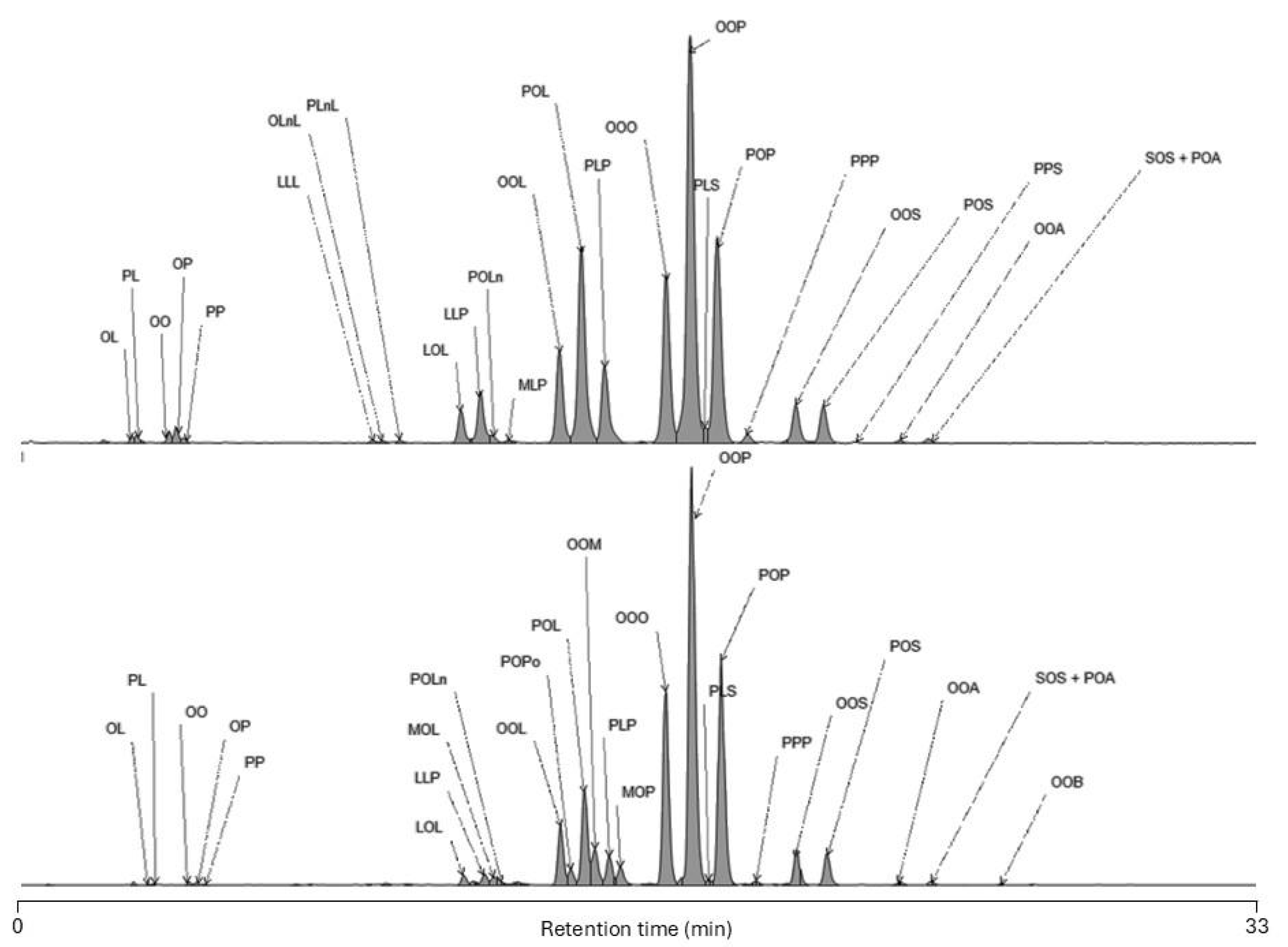

The high-oleic palm oil alternative algal strain demonstrates a close TAG composition to high-oleic palm oil. The main TAG species in both high-oleic palm oil and algal high-oleic palm oil alternative remains (in croissant order) OOP, POP, OOO and OOL (

Table 3 and

Figure 1). The algal strain achieved a similar proportion of Unsat-Unsat-Unsat TAG species (20.32%), far exceeding that of regular palm oil. Its Sat-Sat-Sat TAG species were also notably lower (0.28%) compared to high-oleic palm oil (0.75%) and regular palm oil (4.99%). Additionally, the levels of saturated-unsaturated-unsaturated (Sat-Unsat-Unsat) TAG species in the algal strain (50.90%) closely align with those of high-oleic palm oil (51.73%) and are considerably higher than in regular palm oil (41.02%). These results highlight the algal strain’s capacity to replicate the desirable TAG distribution of high-oleic palm oil, further solidifying its potential as a alternative.

Crude high-oleic palm oil contains 2% of diacylglycerols (DAG,

Figure 1) identified as dipalmitin (PP), diolein (OO), oleoyl-palmitoyl-glycerol (OP), oleoyl-linoleoyl-glycerol (OL) and palmitoyl-linoleoyl-glycerol (PL). The occurrence of partial glycerides such as DAG in high-oleic palm oil and its fractions arises from the characteristics of the raw materials and is a result of the oil’s extraction from ripening fruits. In algal oil, the same DAG species have been identified and the total amount estimated to 0.5% of the oil.

In summary, the high-oleic palm oil alternative algal strain demonstrates a fatty acid and triacylglycerol profile that is remarkably similar to high-oleic palm oil, with nearly identical levels of unsaturated fatty acids and comparable TAG species distributions and a lower level of DAG. These results highlight the strain’s capacity to effectively replicate the overall composition of high-oleic palm oil, reinforcing its potential as a functional alternative to sources historically associated with deforestation, megafauna habitat loss, loss from disease / pests, lack of supply chain traceability and transparency in Sout East Asia (e.g, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand), and Colombia. reinforcing its potential as a sustainable and functional alternative.

4. Discussion

This study successfully demonstrated the development of a high-oleic palm oil alternative using the microalga P. moriformis. Through iterative strain optimization and scaling of fermentation processes, the resulting algal oil closely matched the fatty acid and TAG profiles of high-oleic palm oil. Key findings included an oleic acid content ranging from 55-57% of total fatty acids, with an oil yield of 136.5 g/L and an oil content of 69.45% of dry cell weight (DCW). The TAG profile, characterized by high proportions of unsaturated TAG species, further reinforced the oil’s functionality and nutritional value. These results highlight the potential of microbial fermentation to meet the growing demand for sustainable, scalable, and high-quality oil alternatives.

Our results align with previous studies that emphasize the utility of microbial fermentation for producing high-value lipids. Zhou and co-workers [

11] demonstrated the scalability of

P. moriformis to produce human milk fat analogs, achieving oil yields exceeding 150 g/L with customized fatty acid compositions. Similarly, studies by Silva and co-workers [

15] and Ghazani and Marangoni [

16] have underlined the role of oleaginous microorganisms in generating high-oleic lipids with competitive industrial applications. The oleic acid content reported in this study (56.4%) is consistent with values achieved in related microbial systems, such as

Yarrowia lipolytica [

17] and

Trichosporon capitatum [

18], which also exhibited fatty acid profiles tailored for nutritional and industrial purposes. Additionally, the TAG composition of the algal oil, with elevated unsaturated TAG species and reduced saturated TAG species is comparable to findings from metabolic engineering studies on

Mortierella alpina [

19].

A comparison with the group’s prior work [

12] reveals significant advancements in strain performance. While the earlier study achieved oleic acid levels exceeding 86% of total fatty acids with an oil yield of 145 g/L at industrial scale, this work focuses on replicating high-oleic palm oil’s unique fatty acid and TAG profiles. Both studies underscore the robustness and flexibility of P

. moriformis for sustainable oil production, with this study further emphasizing its capability to produce oils tailored for specific applications. Progress highlights the flexibility of classical strain improvement and fermentation scaling as tools to address evolving industry needs.

Microbial fermentation presents significant environmental benefits by reducing reliance on tropical oil crops such as palm oil. Utilizing oleaginous microorganisms like

Cutane-otrichosporon oleaginosus, researchers have developed sustainable oil production methods that offer a viable alternative to plant-derived oils [

20]. The economic feasibility of microbial oil production might further be enhanced by utilizing low-cost substrates like glycerol [

20]. In this context, microbial fermentation contributes to waste reduction and resource utilization by converting agricultural waste, such as cassava, potato and yam peels, into enriched animal feed, thereby reducing environmental pollution [

21]. Industrial by-products can also serve as fermentation substrates, promoting waste management and sustainability [

22]. Despite these advantages, continued research and technological advancements are necessary to optimize fermentation processes, enhance yield efficiency, and develop cost-effective large-scale production systems to fully realize the potential of microbial solutions.

Furthermore, the environmental benefits of microbial fermentation are corroborated by Meijaard and co-workers [

23], who emphasized the urgent need to reduce reliance on traditional tropical oil crops to mitigate deforestation and biodiversity loss. The scalability and adaptability demonstrated in this study’s fermentation trials strengthens the viability of microbial oil platforms as a sustainable alternative. The cultivation of traditional palm oil in Latin America has faced significant challenges, including deforestation, habitat destruction, and water scarcity [

23]. Although advancements such as OxG hybrids [

9] have improved disease resistance and oil quality, the environmental footprint of traditional cultivation remains a pressing issue. By contrast, the use of

P. moriformis to produce high-oleic oil offers a transformative solution. First, the fermentation process eliminates the need for arable land in tropical regions, directly addressing the drivers of deforestation and habitat loss. Second, the process requires significantly less water compared to traditional palm oil cultivation, as demonstrated in recent studies [

24,

25]. Third, the sustainability of the process is influenced by the origin of the sugar feedstock, with sourcing from sustainably managed agricultural systems further enhancing its environmental benefits. Finally, the adaptability of microbial systems to non-tropical regions, as highlighted by Patel and co-workers [

26], enables decentralized production, reducing transportation-related carbon emissions. From a socio-economic perspective, the fermentation of

P. moriformis could provide a sustainable livelihood for industries in non-tropical regions, while alleviating pressure on palm oil-producing nations. By leveraging microbial fermentation, stakeholders can align their operations with global sustainability goals, including the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions [

25] and the preservation of biodiversity.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study highlights the potential of P. moriformis as a sustainable and scalable platform for producing high-oleic palm oil alternatives. By aligning closely with the fatty acid and TAG profiles of conventional high-oleic palm oil, this microbial approach offers a viable solution to mitigate the environmental challenges associated with traditional palm oil cultivation. The findings underscore the transformative potential of microbial fermentation in building sustainable and resilient supply chains for the global oils and fats industry.

6. Patents

The data presented in this paper are described in the WO2023212726A2 patent entitled “Regiospecific incorporation of fatty acids in triglyceride oil”.

Author Contributions

L.P., K.W., T.P., J.P., P.D. and S.F. developed the algae strain. D.A., B.D., L.E., N.R. and G.A. performed the fermentation trials. J.W. and G.E. performed the extraction and refining of the algae oil samples. M.C., V.B. and R.M. conducted all the analytical method development and quantification of fatty acids and F.D., L.P., W.R. and S.F. determined the target composition from literature and wrote the manuscript draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors were all on the Checkerspot, Inc. team at the time of this work and did not receive any funds from third parties to perform this development.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors are team members of Checkerspot, Inc., headquartered in Alameda, California (USA) and declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Faure, J.-D.; Napier, J.A. Point of View: Europe’s first and last field trial of gene-edited plants? eLife 2018, 7, e42379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mozzon, M.; Foligni, R.; Mannozzi, C. Current Knowledge on Interspecific Hybrid Palm Oils as Food and Food Ingredient. Foods 2020, 9, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón, S.M.; Hormaza, P.A.; Moreno, L.P.; Prada, F.; Portillo, D.J.; García, J.A.; Romero, H.M. Use of phenological stages of the fruits and physicochemical characteristics of the oil to determine the optimal harvest time of oil palm interspecific OxG hybrid fruits. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2013, 49, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedepalma. Statistical Yearbook 2019. The Oil Palm Agroindustry in Colombia and the World 2014-2018; Federación Colombiana de Cultivadores de Palma de Aceite: Bogota, Colombia, 2019; p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera-Montoya, M.; Ruiz, E.; Munevar-Martínez, D.E.; Castro, L.; Moreno, L.P.; López-Alfonso, D.F. Oil palm agroindustry 2019 production costs: A benchmarking study among companies that have adopted good practices. Rev. Palmas 2020, 41, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hormaza, P.; Fuquen, E.M.; Romero, H.M. Phenology of the oil palm interspecific hybrid Elaeis oleifera × Elaeis guineensis. Sci. Agricola 2012, 69, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera-Montoya, M.; Ruiz-Alvarez, E.; Castros-Zamudio, L.E.; López-Alfonso, D.F.; Munevar-Martínez, D.E. Estimación del costo de producción para productores de palma de aceite de Colombia que han adoptado buenas prácticas agrícolas. Rev. Palmas 2019, 40, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Yarra, R.; Jin, L.; Zhao, Z.; Cao, H. Progress in Tissue Culture and Genetic Transformation of Oil Palm: An Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogollon, D.I.N.; Venturini, O.J.; Batlle, E.A.O.; González, A.M.; Munar-Florez, D.A.; Ramirez-Contreras, N.E.; García-Nuñez, J.A.; Borges, P.T.; Lora, E.E.S. Environmental and energy issues in biodiesel production using palm oil from the interspecific hybrid OxG and Elaeis guineensis: a case study in Colombia. OCL 2024, 31, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Santana, M.; Cagampang, G.B.; Nieves, C.; Cedeño, V.; MacIntosh, A.J. Use of High Oleic Palm Oils in Fluid Shortenings and Effect on Physical Properties of Cookies. Foods 2022, 11, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhao, X.; Parker, L.; Derkach, P.; Correa, M.; Benites, V.; Miller, R.; Athanasiadis, D.; Doherty, B.; Alnozaili, G.; et al. Development and large-scale production of human milk fat analog by fermentation of microalgae. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1341527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L.; Ward, K.; Pilarski, T.; Price, J.; Derkach, P.; Correa, M.; Miller, R.; Benites, V.; Athanasiadis, D.; Doherty, B.; et al. Development and Large-Scale Production of High-Oleic Acid Oil by Fermentation of Microalgae. Fermentation 2024, 10, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrdwell, W.C. The Updated Bottom Up Solution applied to mass spectrometry of soybean oil in a dietary supplement gelcap. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407, 5143–5160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, T. , Petersen, K., & Kris-Etherton, P. (2022). Health aspects of high-oleic oils. In High Oleic Oils; AOCS Press: Champaign, IL, USA, pp. 201-243.

- Silva, J.D.M.E.; Martins, L.H.D.S.; Moreira, D.K.T.; Silva, L.D.P.; Barbosa, P.D.P.M.; Komesu, A.; Ferreira, N.R.; Oliveira, J.A.R.D. Microbial lipid-based biorefinery concepts: A review of status and prospects. Foods 2023, 12, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazani, S.M.; Marangoni, A.G. Microbial lipids for foods. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2022, 119, 593–607. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Shi, T.-Q.; Wang, J.; Wei, P.; Ledesma-Amaro, R.; Ji, X.-J. Engineering the Lipid and Fatty Acid Metabolism in Yarrowia lipolytica for Sustainable Production of High Oleic Oils. ACS Synth. Biol. 2022, 11, 1542–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Zong, M. Production of microbial oil with high oleic acid content by Trichosporon capitatum. Appl. Energy 2010, 88, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, T.; Sakuradani, E.; Okuda, T.; Kikukawa, H.; Ando, A.; Kishino, S.; Izumi, Y.; Bamba, T.; Shima, J.; Ogawa, J. Metabolic engineering of oleaginous fungus Mortierella alpina for high production of oleic and linoleic acids. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 245, 1610–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman-Özdamar, Zeynep Efaun, et al. (2024). Combining metabolic engineering and fermentation optimization to achieve cost-effective oil production by Cutaneotrichosporon oleaginosus. bioRxiv, 2024-11.

- El-Imam, A. , Yafetto, L., Odamtten, G.T., & Wafe-Kwagyan, M. (2019). Valorization of agro-industrial wastes into animal feed through microbial fermentation: A review of the global and Ghanaian case. Heliyon, 9.4.

- Roy, M.; Mohanty, K. (2020). Byproducts of a Microalgal Biorefinery as a Resource for a Circular Bioeconomy. Biotic Resources. CRC Press, 109-138.

- Meijaard, E.; Brooks, T.M.; Carlson, K.M.; Slade, E.M.; Garcia-Ulloa, J.; Gaveau, D.L.A.; Lee, J.S.H.; Santika, T.; Juffe-Bignoli, D.; Struebig, M.J.; et al. The environmental impacts of palm oil in context. Nat. Plants 2020, 6, 1418–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carsanba, E.; Papanikolaou, S.; Erten, H. Production of oils and fats by oleaginous microorganisms with an emphasis given to the potential of the nonconventional yeast Yarrowia lipolytica. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2018, 38, 1230–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.; Morão, A.; Johnson, J.K.; Shen, L. Life cycle assessment of heterotrophic algae omega-3. Algal Res. 2021, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.K.; Chauhan, A.S.; Kumar, P.; Michaud, P.; Gupta, V.K.; Chang, J.-S.; Chen, C.-W.; Dong, C.-D.; Singhania, R.R. Emerging prospects of microbial production of omega fatty acids: Recent updates. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 360, 127534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).