1. Introduction

Anxiety disorders are disorders characterized by excessive fear and anxiety and related behavioral disturbances, with severe enough symptoms to result in significant distress or significant impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational, or other important areas of functioning [

1]. These disorders share features of excessive fear and anxiety, where fear is defined as an emotional response to an imminent, real, or imagined threat, and anxiety as the anticipatory response to a future threat. Anxiety disorders are common mental health conditions that affect a significant portion of the population [

2]. These conditions can have a considerable impact on an individual’s quality of life, interfering with daily functioning and causing significant emotional distress [

3]. These disorders include generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, specific phobias, agoraphobia, separation anxiety disorder, and selective mutism [

1] (p.1).

Currently, there are treatments considered effective for managing these disorders [

4,

5], such as gradual exposure, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), or mindfulness. Conceptually, one challenge with these effective therapies is identifying the processes through which they work. Paradoxically, despite not sharing a conceptual foundation or underlying mechanisms, different therapies have been found effective in treating the same mental health disorders, including anxiety disorders [

6]

One way to verify the underlying mechanisms of psychological treatment comes from a neuroscience perspective. Psychological changes can be reflected in changes in neural connectivity [

7]. These changes may extend to structural changes in the brain. Accordingly, there has been a preference for experimental studies on the brain activity of individuals receiving different psychological treatments. Initial data provided by neurocognitive studies show neural connectivity consistent with the theoretical model of CBT: if cognitive work generates positive effects, the processing of anxiety contexts would be characterized by greater activation of executive areas responsible for emotional regulation (such as the ventromedial and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) and, consequently, a decrease in activation of limbic areas, especially the amygdala and, possibly, the insula. This has been termed the dual-route model [

8]. Essentially, the dual-route model describes a balance between an automatic processing response (impulsive) and a top-down, cognitive regulation response (reflective), observable in the described changes.

Early studies using fMRI techniques applied to CBT in anxiety disorders confirmed these hypotheses [

9], supporting a dual-route model of psychological treatment effects on the control of anxiety states (an increase in activity in emotional regulation areas and a decrease in activation of limbic areas). Compared to pre-treatment levels, increased activation of the ventromedial and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and decreased activation of the amygdala were observed post-treatment [

10].

However, not all available data supports this dual-route model. In the review by Lueken & Hahn (2017) [

8] (p. 2), it was noted that such increased activation in prefrontal areas does not always occur. Another review [

11] found this to be true, with some studies showing lower activation in these areas and greater activation in other associative areas (particularly the anterior cingulate gyrus and superior parietal areas.

The dual-route model as an explanation for CBT’s effectiveness in Specific Phobia has been the subject of ongoing debate. Conducting a scoping review to explore the evidence surrounding this model offers an opportunity to comprehensively map the available literature, shedding light on the mechanisms underpinning CBT’s effectiveness in Specific Phobia. Furthermore, this approach facilitates the examination of whether the dual-route model’s mechanisms extend to anxiety disorders more broadly, providing insights into shared or divergent neural pathways.

Therefore, the main objective of this scoping review was to explore the factors contributing to the efficacy of CBT in specific phobia, with the aim of providing evidence to clarify or expand the ongoing debate surrounding the dual-route model, which currently explains CBT's effectiveness in this disorder. A secondary objective was to explore whether the mechanisms of the dual-route model also apply to anxiety disorders more broadly, providing evidence for CBT’s efficacy in treating them.

2. Materials and Methods

To achieve these objectives, a review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist, a 22-item checklist designed to promote transparency by explaining the rationale for the review, the methods used, and the results obtained [

12].

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria:

Studies published from 2018 onwards were included. To ensure that the review encompasses the most recent advancements in cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), and given the significant contributions by Lueken et al. (2017) [

8] (p.2), who made notable advancements in understanding the dual-route model of CBT for anxiety disorders, this year was selected as the starting point for our search, aiming to incorporate the most current evidence related to the dual-route model and its application.

Experimental studies, randomized clinical trials or randomized controlled trials applying some CBT procedure

CBT used as a treatment for phobic and/or anxiety disorders with clinical or subclinical samples

Studies providing improvement in phobic and/or anxiety symptoms as a consequence of CBT application

Studies providing neuroimage data about CBT efficacy

Studies using adult samples

Studies published in Spanish, English or French.

Exclusion criteria:

Observational studies (cohorts, cases/non-cases, cross-sectionals), single case designs, qualitative studies or literature reviews

Studies where phobic and/or anxiety disorders were secondary disorders to a major disorder

Studies not providing fMRI data

fMRI data provided cannot test the presence or absence of dual-route model

2.3. Information Sources

The review search was conducted using the following databases: SCOPUS, APA PsycInfo, APA PsycArticles, Web of Science and SpringerLink.

2.4. Search Strategy

The search string used was: (‘’anxiety disorders’’ OR ‘’Generalized Anxiety Disorder’’’ OR ‘’specific phobia’’ OR ‘’Agoraphobia’’ OR ‘’Panic Disorder’’ OR ‘’Social Anxiety Disorder’’) AND ("cognitive behavioral therapy" OR "CBT" OR "cognitive therapy" OR "behavioral therapy" OR "exposure therapy") AND ("functional magnetic resonance imaging" OR "fMRI" OR "neuroimaging" OR "brain imaging" OR "functional MRI")

2.5. Selection of Sources of Evidence

Only peer-reviewed scientific articles were considered for inclusion in this scoping review. Other sources, such as conference proceedings, symposium abstracts, or unpublished data, were excluded to ensure the methodological rigor and reliability of the findings.

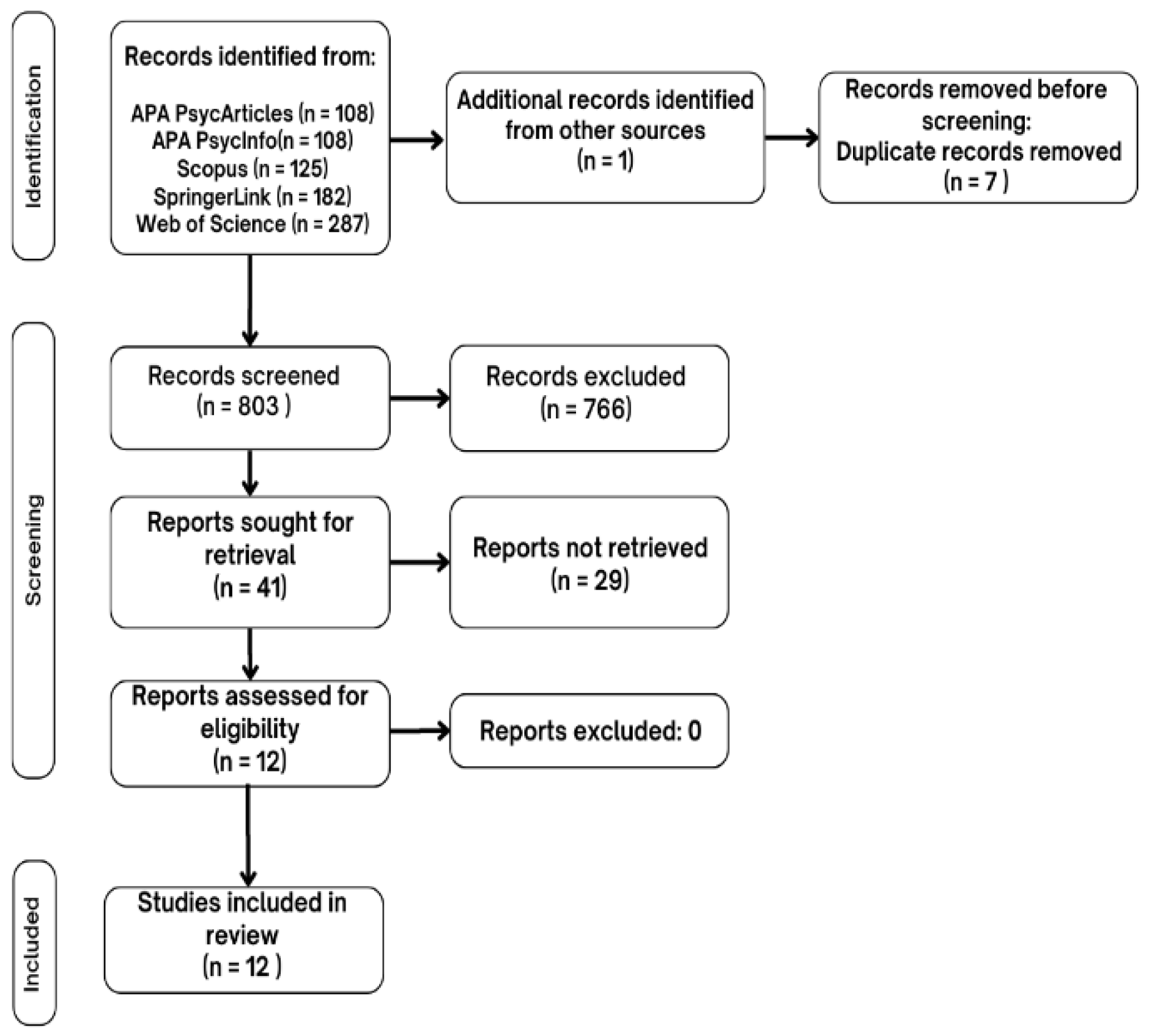

The selection process adhered to the PRISMA flow diagram. First, in the identification phase, duplicates were removed. During the screening phase titles and abstracts were revised, and publications that didn’t meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria were removed. Afterwards, publications selected for eligibility assessment were read in full, with those deemed ineligible being excluded. Finally, studies meeting all inclusion criteria were included in the systematic review.

Additionally, the Cochrane quality assessment scale was used to evaluate the methodological quality of included studies.

2.6. Data Charting Process

The data charting process was conducted using a predefined and calibrated form to extract key information systematically from each included study. Charting was performed independently by two reviewers to enhance reliability, with discrepancies resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. This ensured consistency in capturing relevant variables, such as study design, population characteristics, intervention details, and key outcomes.

2.7. Data Items

The following key data items were charted from the included studies and structured into a summary table:

Author(s): The primary authors of each study.

Disorder: The specific anxiety disorder addressed in the study.

Participants: Sample size and characteristics (e.g., patient vs. control groups).

Results: Key findings, particularly those related to neuroimaging data (e.g., changes in brain activity pre- and post-CBT).

This approach ensures that the data extraction process aligns directly with the scoping review objectives, facilitating a clear synthesis of the findings.

2.8. Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources

The quality of included studies was assessed using the Cochrane quality assessment scale [

13], a standardized tool for evaluating methodological rigor. This appraisal considered elements such as randomization, blinding, control of confounding factors, and reporting completeness. The results of this evaluation were used to contextualize the findings, identifying potential biases and varying levels of evidence quality among the included studies.

2.9. Synthesis of Results

The synthesis of results was performed narratively, summarizing the charted data in relation to the review objectives. Patterns in neuroimaging findings were identified and linked to the theoretical framework of the dual-route model. Discrepancies among studies, such as differences in prefrontal cortex activation, were highlighted to reflect the variability in evidence. Results were tabulated to present key findings systematically, while the narrative discussion emphasized overarching trends, gaps in knowledge, and potential implications for future research.

3. Results

The selection and analysis process for the studies in this scoping review followed the PRISMA flow diagram. In

Figure 1 the selection process is summarized. Initially, 803 studies were identified in specific databases, removing duplicates. Based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, 12 studies were finally selected and included in the scoping review.

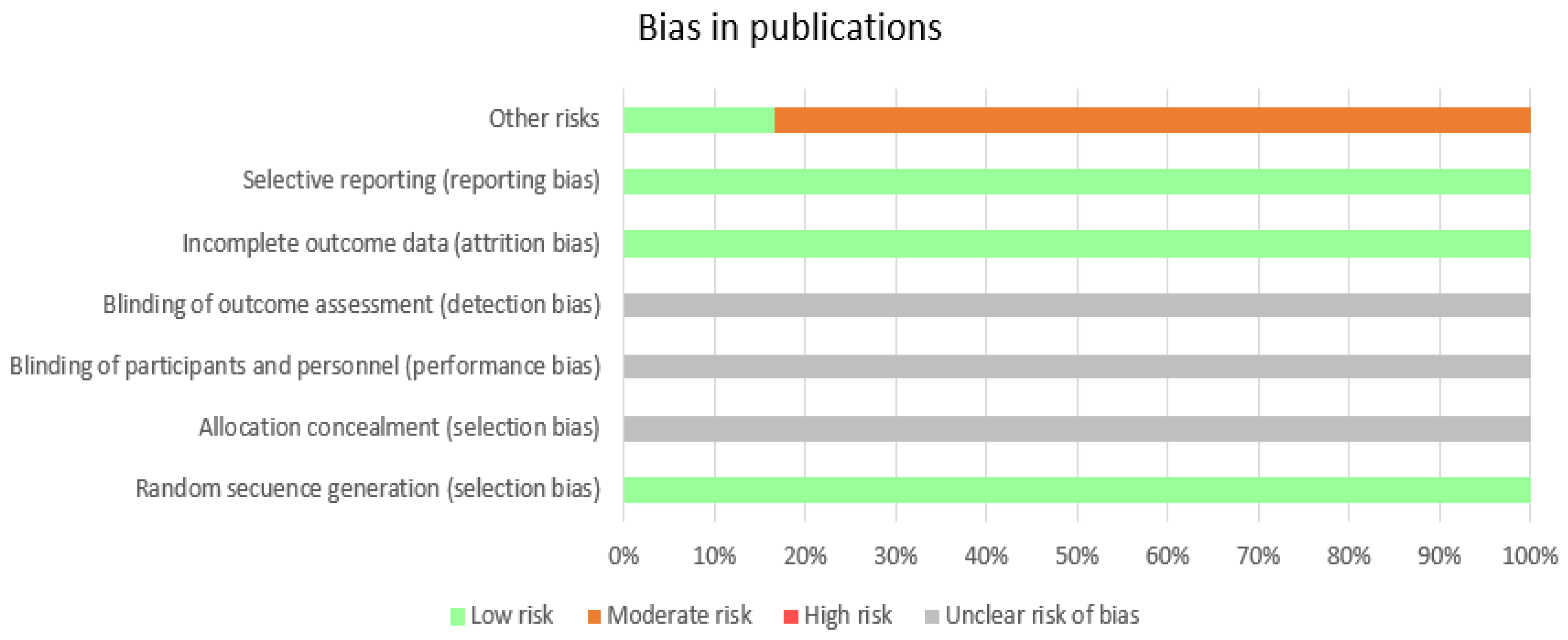

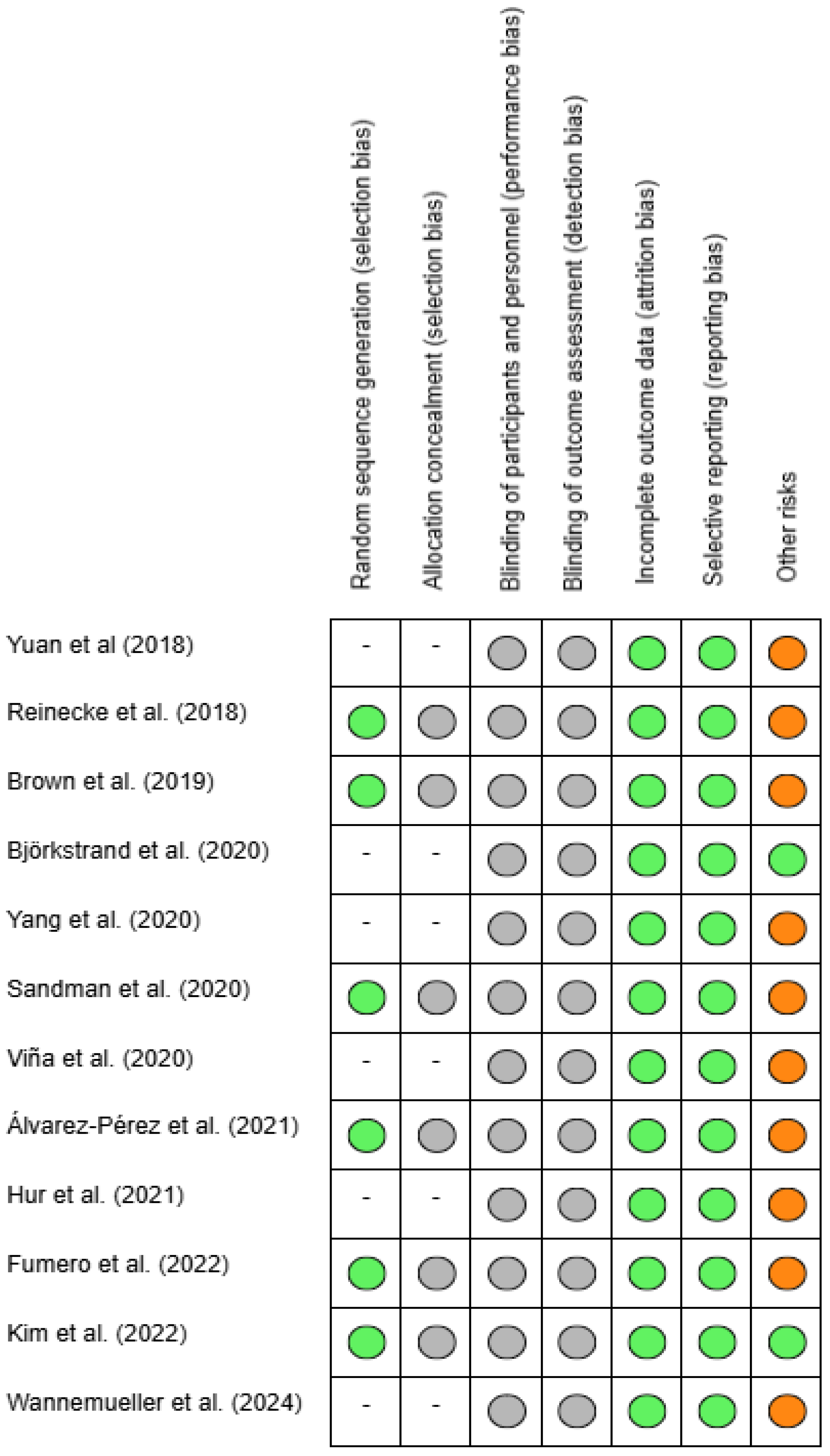

Regarding the bias risk of the articles, Cochrane quality assessment scale was administered, to assess their quality. In

Figure 2 the chart presented provides a visual representation of bias levels in different categories, indicating areas of low, moderate, high, and unclear risks. As can be observed, almost all publications comply with reporting dropout rates and informing about the potential methodological limitations of their studies. Half of the studies report on the randomization process. The highest risks have been identified in the detection of other risks (for example having a small sample, not having a control group or patients being medicated for their disorder). Additionally, the aspect that is expressed with the least clarity is blinding and allocation concealment.

In

Figure 3, the chart indicates the level of bias identified in each study, classifying the risks as low, moderate, high, or unclear in the different categories mentioned above.

On the following table there’s a summary of the main results found in each included study, as well as the authors, the disorder which is studied and the participants that took part in the study.

Table 1.

Results.

| Author |

Disorder |

Participants |

Results |

| Yuan at al. (2018) [14] |

SAD |

1 patients, 19 healthy controls |

Decreased amplitude of low-frequency fluctuation (ALFF) was observed in the right precuneus. Reduced degree centrality (DC) in the left precuneus and left middle temporal gyrus, as well as increased DC in the right putamen. |

| Reinecke et al. (2018) [15] |

Panic Disorder |

28 participants. 14 in treatment group, 14 in waiting group |

Reductions in amygdala, left middle-superior temporal gyrus, dorsomedial (dmPFC) and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC). Decreased connectivity between the right amygdala and left precuneus/posterior cingulate cortex during emotion regulation tasks. |

| Brown et al. (2019) [16] |

SAD |

64 participants. 17 participants in CBT group. 20 ACT group and 14 waitlist. 13 healthy controls. |

Decreased activation in left insula and anterior cingulate cortex during self-referential processing. Stronger positive connectivity between the amygdala and FFA during self-referential processing in participants with greater reductions in social anxiety severity (measured by LSAS). Decreased connectivity between the amygdala and insula in the treatment group but increased in the waitlist group. |

| Björkstrand et al. (2020) [17] |

Specific phobia |

45 participants |

Reduced amygdala reactivity. At 6-month follow up, initial reductions in amygdala activation still predicted avoidance. Decreased activation in the anterior insula, dorsal hippocampus, supplementary motor area, and visual cortex during repeated exposure to spider images. |

| Yang et al. (2020) [18] |

Panic Disorder |

42 patients and 52 healthy controls |

Attenuation of neural activation in the anterior cingulate cortex for processing of panic-trigger/panic-symptom word pairs. |

| Sandman et al. (2020) [19] |

SAD |

23 participants. 11 patients to CBT group and 12 to ACT group. |

Negative changes in amygdala connectivity with regulatory brain regions (e.g., dorsomedial prefrontal cortex [dmPFC] and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex [dACC]). |

| Viña et al. (2020) [20] |

Specific phobia |

32 participants: 16 patients and 16 healthy controls |

Increased activation in the precuneus, and reduced activation in fear-related regions, such as the thalamus and visual cortex (e.g., the calcarine gyrus). |

| Álvarez-Pérez et al. (2021) [21] |

Specific phobia |

31 participants. 17 in CBT with real images and 14 in CBT with VR |

Reduced activity in the thalamus, fusiform gyrus, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex after treatment, Amygdala activity was reduced but still present. |

| Hur et al. (2021) [22] |

SAD |

21 patients and 22 healthy controls |

Increased activation in the posterior cingulate cortex/precuneus, lingual gyrus, inferior temporal gyrus, precentral gyrus, and postcentral gyrus during positive self-referential processing. There was also enhanced activation in the middle occipital gyrus, parahippocampus, Rolandic operculum, superior frontal gyrus, and caudate nucleus during negative self-referential processing. |

| Fumero et al. (2022) [23] |

Specific phobia |

30 participants. 9 participants self-verbalization training (S), 10 participants breathing training (B) and 11 participants exposure-only (E). |

Exposure-Only Condition (E): Greater activation in fear-related regions: Amygdala, insula, anterior and middle cingulate cortex, ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Increased activity in sensory-perceptive and motor areas: Postcentral gyrus, precentral gyrus, and superior occipital cortex.

Self-Verbalization Condition (S): Activation of top-down regulatory areas: Inferior frontal gyrus (pars opercularis and pars triangularis).

Breathing Condition (B): Reduced activation in fear-related areas.. |

| Kim et al. (2022) [24] |

SAD |

52 participants. 24 patients and 28 control group |

Decreased nodal efficiency in left inferior frontal gyrus (language processing circuits), left Heschl’s gyrus (auditory language comprehension) and increased degree centrality in right calcarine sulcus (visual processing), and left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (reduced overactivation, suggesting improved cognitive control). |

| Wannemueller et al. (2024) [25] |

Specific phobia |

17 patients and 17 healthy controls. |

Decrease in activity in the amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex, precuneus, insula and parietal cortex. ACC activation decrease correlated with reductions in dental fear. |

A summary of the quantity of studies for each disorder can be found in

Table 2. It can be observed that specific phobia is the disorder that had more articles, followed by social anxiety disorder and, finally, panic disorder.

4. Discussion

In this scoping review, the main objective was to explore the factors contributing to the efficacy of CBT in specific phobia, with the aim of providing evidence to clarify or expand the ongoing debate surrounding the dual-route model, which currently explains CBT's effectiveness in this disorder. A secondary objective was to explore whether the mechanisms of the dual-route model also apply to anxiety disorders more broadly, providing evidence for CBT’s efficacy in treating them.

The results from the research conducted indicate that, since 2018, 12 studies have been focused on finding the reasons why CBT is effective for anxiety disorders at a brain activation level, which, in itself, presents a limitation on extracting conclusions.

4.1. Specific Phobia

Across all studies, before CBT amygdala, ACC and insula are hyperactivated, implying a dominance on the impulsive route, aligning with the dual-route model. CBT consistently reduces subcortical activity and improves top-down regulation, restoring the balance between cortical and subcortical systems. Although the model predicts a significant reduction in subcortical activity, some studies show residual responses in the amygdala even after treatment [

21], suggesting that cortical regulation may not be entirely effective in all cases. According to that result, and the fact that in all studies subjective anxiety levels were reduced, and therefore, CBT worked, there’s a need to explore the reasons behind that. Some of the studies emphasize intermediate areas such as lateral parietal cortex or the precuneus, which are not found in the traditional dual-route model. The precuneus seems to be a key node in anxiety disorders and, more specifically in specific phobia, as it is involved in self-referential processing, plays an important role in emotional processing and shows improvements following treatment. Additionally, precuneus activity seems to be different among phobic stimuli after treatment. Small animals’ phobia finds that precuneus activity is enhanced after CBT [

20,

21,

23], which can be related with better emotional regulation and ability to reorganize phobic stimuli meaning. On the other hand, the dental phobia experiment [

25] found a reduction in precuneus activation, which can be related to reduced egocentric processing or rumination over phobic stimuli.

4.2. Social Anxiety Disorder

Amygdala, insula and prefrontal areas are consistently affected after CBT regarding clinical improvement. Other areas seem relevant for CBT’s effectiveness such as the precuneus, which activation proved to be reduced after treatment [

14] and seems to be altered before treatment [

16,

19,

24], although these studies didn’t mention what happened to precuneus activation post-treatment, it’s implied that as a central aspect in negative auto-referential processes and rumination, the reduction in its hyperactivity leads to a disconnection in persistent negative thoughts and improvement in emotional regulation.

Fusiform gyrus activation showed a reduction in its activation as well [

16,

24], which implies a normalization in the reactivity and sensitivity to visual information during social evaluation. Medial temporal gyrus also finds enhanced connectivity after CBT [

14,

22], which provides a better ability to integrate sensory and linguistic information in social contexts. Posterior cingulate cortex shows also reduced activation after treatment, which may indicate a reduction in negative thoughts.

Dual-route model, understanding it as a balance between hyperactivation and regulation, can be extrapolated to SAD, although the traditional areas involved need to be expanded, including default mode network and sensorial areas that contribute to the disorder, as extracted from the results.

4.3. Panic Disorder

Results of Panic Disorder articles show that there was a reduction in amygdala activation, which was related to clinical improvement. Although ACC was heavily studied in Yang et al. (2020) [|8] in comparison to Reinecke et al. (2018) [

15], which means that there’s no explicit mention of amygdala, it’s implied that there was a reduction in its activation after CBT. ACC activation is reduced and there’s a reduced activation in dmPFC and dlPFC, which indicates better efficiency over emotional regulation and less need for cognitive efforts to handle stimuli. Both studies seem to partially support the dual-route Model, although there needs to be emphasis on areas involved in interoception such as insula or ACC, and internal signals monitoring, which expands the traditional dual-route model.

Overall, the findings partially support the dual-route model in the case of CBT for panic disorder and specific phobia, where consistent reductions in limbic activation (e.g., amygdala) and adjustments in prefrontal regions responsible for emotional regulation are observed. However, in SAD, the results are more varied. While there is evidence for reduced limbic reactivity, the increased prefrontal connectivity may indicate a stronger engagement of emotional control pathways, suggesting that the dual-route model may require adaptation depending on the specific disorder.

Across all disorders, amygdala and ACC activity reductions reflect a shared mechanism of improved fear and emotion regulation following CBT. These findings align well with the dual-route model framework. Nevertheless, differences in precuneus and PFC activity highlight the need for disorder-specific adaptations of the dual-route model. For example, changes in precuneus activity in specific phobia and SAD suggests unique pathways for self-referential and emotional processing that may not align directly with the dual-route model. Taking this diversity into account, a need for study of the dual-route model and its possible expansion to other areas urges.

From this scoping review, the main conclusion that can be extracted is that the dual-route model doesn’t necessarily apply to all anxiety disorders, and more areas are involved depending on which disorder is being studied. On the other hand, for specific phobia, which has been widely accepted that CBT’s effectiveness relies on this dual-route model, data implies that dual-route model may not be enough to explain why CBT works, and there are several areas that should be studied to further complete this model and expand it, such as the precuneus, which activation consistently shows to be affected after CBT.

The dual-route model remains a valuable framework for understanding CBT’s neurobiological effects. However, future research should investigate the role of self-referential processing and variability in regulatory regional activation to refine the model for different anxiety disorders.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CBT |

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy |

| SAD |

Social Anxiety Disorder |

| PRISMA |

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews |

| AAC |

Anterior Cingulate Cortex |

| ALFF |

Amplitude of low-frequency activity |

| DC |

Degree centrality |

| LSAS |

Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale |

| FFA |

Fusiform face area |

| EBA |

Extrastriate body area |

| HC |

Healthy controls |

| dmPFC |

Dorsomedial prefrontal cortex |

| dACC |

Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex |

| dlPFC |

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex |

References

- World Health Organization (2019). International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision). https://icd.who.int/en.

- Baxter, A.J.; Scott, K.M.; Vos, T.; Whiteford, H.A. Global prevalence of anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-regression. Psychol. Med. 2013, 43, 897–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Barlow, D. H. (2002). Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Hayes, S.C. (2004). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior therapy, 35, 639-665.

- Apolinário-Hagen, J., Drüge, M., & Fritsche, L. (2020). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Mindfulness- Based Cognitive Therapy and Acceptance Commitment Therapy for Anxiety Disorders: Integrating Traditional with Digital Treatment Approaches. En Y.K. Kim (Ed.). Anxiety Disorders. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology (V. 1191). Springer.

- Kandel, E.R. A New Intellectual Framework for Psychiatry. Am. J. Psychiatry 1998, 155, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lueken, U., & Hahn, T. (2015). Functional neuroimaging of psychotherapeutic processes in anxiety and depression: From mechanisms to predictions. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 2015, 29, 25–31.

- Weingarten, C.P.; Strauman, T.J. Neuroimaging for psychotherapy research: Current trends. Psychother. Res. 2014, 25, 185–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldin, P.R.; Ziv, M.; Jazaieri, H.; Weeks, J.; Heimberg, R.G.; Gross, J.J. Impact of cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder on the neural bases of emotional reactivity to and regulation of social evaluation. Behav. Res. Ther. 2014, 62, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marwood, L.; Wise, T.; Perkins, A.M.; Cleare, A.J. Meta-analyses of the neural mechanisms and predictors of response to psychotherapy in depression and anxiety. 2018, 95, 61–72. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K. K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M. D. J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, M.; Zhu, H.; Qiu, C.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Z.; Li, Y.; Yuan, C.; Gao, M.; Lui, S.; et al. Altered regional and integrated resting-state brain activity in general social anxiety disorder patients before and after group cognitive behavior therapy. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2017, 272, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinecke, A.; Thilo, K.V.; Croft, A.; Harmer, C.J. Early effects of exposure-based cognitive behaviour therapy on the neural correlates of anxiety. Transl. Psychiatry 2018, 8, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, L.A.; Young, K.S.; Goldin, P.R.; Torre, J.B.; Burklund, L.J.; Davies, C.D.; Niles, A.N.; Lieberman, M.D.; Saxbe, D.E.; Craske, M.G. Self-referential processing during observation of a speech performance task in social anxiety disorder from pre- to post-treatment: Evidence of disrupted neural activation. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2019, 284, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björkstrand, J.; Agren, T.; Frick, A.; Hjorth, O.; Furmark, T.; Fredrikson, M.; Åhs, F. Decrease in amygdala activity during repeated exposure to spider images predicts avoidance behavior in spider fearful individuals. Transl. Psychiatry 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Lueken, U.; Richter, J.; Hamm, A.; Wittmann, A.; Konrad, C.; Ströhle, A.; Pfleiderer, B.; Herrmann, M.J.; Lang, T.; et al. Effect of CBT on Biased Semantic Network in Panic Disorder: A Multicenter fMRI Study Using Semantic Priming. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandman, C.F.; Young, K.S.; Burklund, L.J.; Saxbe, D.E.; Lieberman, M.D.; Craske, M.G. Changes in functional connectivity with cognitive behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder predict outcomes at follow-up. Behav. Res. Ther. 2020, 129, 103612–103612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viña, C., Herrero, M., Rivero, F., Álvarez-Pérez, Y., Fumero, A., Bethencourt, J. M., Pitti, C., & Peñate, W. (2020). Changes in brain activity associated with cognitive-behavioral exposure therapy for specific phobias: Searching for underlying mechanisms. Revista de Neurologia, 71(11), 391–398. [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Pérez, Y.; Rivero, F.; Herrero, M.; Viña, C.; Fumero, A.; Betancort, M.; Peñate, W. Changes in Brain Activation through Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy with Exposure to Virtual Reality: A Neuroimaging Study of Specific Phobia. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hur, J.-W.; Shin, H.; Jung, D.; Lee, H.-J.; Lee, S.; Kim, G.J.; Cho, C.-Y.; Choi, S.; Lee, S.-M.; Cho, C.-H. Virtual Reality–Based Psychotherapy in Social Anxiety Disorder: fMRI Study Using a Self-Referential Task. JMIR Ment. Heal. 2021, 8, e25731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fumero, A.; Marrero, R.J.; Olivares, T.; Rivero, F.; Alvarez-Pérez, Y.; Pitti, C.; Peñate, W. Neuronal Activity during Exposure to Specific Phobia through fMRI: Comparing Therapeutic Components of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Life 2022, 12, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Kim, B.-H.; Kim, M.-K.; Eom, H.; Kim, J.-J. Alteration of resting-state functional connectivity network properties in patients with social anxiety disorder after virtual reality-based self-training. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 959696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wannemueller, A.; Margraf, J.; Busch, M.; Jöhren, H.-P.; Suchan, B. More than fear? Brain activation patterns of dental phobic patients before and after an exposure-based treatment. J. Neural Transm. 2024, 131, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).