Corrosion is the gradual deterioration of substances, particularly metals, when they undergo chemical reactions with their environment, possibly when they come in contact with water, air, and corrosive chemicals such as acids. Aluminum is one of the metals which are prone to corrosion in industries. It is used to construct chemical vessels, transportation, and food packaging materials [

1]; hence efforts are made to mitigate its corrosion. Aluminum is very desirable for use in industries owing to its low density and great tensile strength. The corrosion of aluminum in hydrochloric acid involves its dissolution because of the chloride content in the acid, which helps to accelerate aluminum corrosion, leading to the breakdown of the protective aluminum oxide naturally formed on the surface of the metal, and further accelerate the corrosion process [

1]. Green inhibitors are preferred over conventional inhibitors because of their environmental friendliness, and they can be sourced from renewable and locally available materials, making them sustainable. The Hibiscus sabdariffa plant, also referred to as roselle, is a member of the family

Malvaceae. It is used to make a nourishing food drink, which is equally highly medicinal and recommended for treating high blood pressure depending on how it is prepared.

The plant Hibiscus sabdrariffa has the potential to function as a corrosion inhibitor because it has many phytochemicals which work by adhering to metal surfaces and protect the metal from the attack of corrosive substances [

1]

[

2] Reviewed 335 articles which consisted of plant extracts studied for their corrosion inhibition properties and results showed good inhibition performance greater than 80%.

[

3] Enlisted in the search for ecofriendly corrosion inhibitor by employing Patanus acerifolia leaves to reduce chloride induce reinforced corrosion, making use of electrochemical techniques.

[

4] Also provided evidence to consolidate literature on eco-friendly corrosion inhibitors by carrying out review on past corrosion works for extracts from leaves, stems and fruits of plants for aluminum alloy corrosion in acidic media. [

5] Investigated the corrosion inhibition performance of Artimisia annua L. aqueous extract (AAE) on aluminum alloy by employment electrochemical techniques and confirmed that AAL reduced the corrosion of aluminum alloy substantially by physisorption adsorption mechanism. [

6] Reviewed comprehensively the corrosion inhibition of aluminum alloy by plant extracts, with the aim of providing substantial evidence on the potential of plant extracts as eco-friendly corrosion inhibitors of aluminum alloys, highlighting the adsorption mechanism, and as well showing their advantage over traditional inhibitors in terms of less toxicity to the ecosystem.

[

7] Also provided evidence for plants as good inhibitors of aluminum corrosion in their study of aqueous extract of Aegle marmelos Leaves for corrosion of aluminum in H2SO4 acid using weight loss technique, which gave inhibition efficiencies of between 81 % to 90 %. [

8] Evaluated the corrosion behavior of aluminum-based fiber–metal laminates (FMLs) in basic media, by employing weight loss techniques, potentiodynamic polarization measurements and electrochemical-impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and the Tafel curve showed inhibition efficiency of 88 %. The adsorption mechanism was provided using Langmuir adsorption isotherm. Characterization using Fourier Transformer Infra-Red technique provided evidence of aromatic links, heteroatoms and oxygen, which enhanced the corrosion inhibition ability of FML. [

9] Provided a review of plant extracts’ inhibition potential to retard the corrosion of aluminum in acidic media, which reflected their inhibition efficiencies between 90 to 99 %. [

10] Evaluated the inhibition performance of Ilex paraguariensis in the temperature range of 298–323 K, by employing weight loss tests, potentiodynamic polarization measurements and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy techniques and confirmed that Ilex paraguariensis has good inhibition performance which was sustained even at elevated temperature. [

11] Studied the inhibition of aluminum alloy corrosion in alkaline environment by green tea and tulsi extract and obtained inhibition efficiencies of 83.93 % and 14.29 % respectively. [

12] Evaluated the inhibition of mild steel corrosion by Arbutus unedo leaf extract in hydrochloric acid, and obtained maximum inhibition efficiency for concentration as low as 0.5 g/L. [

13] assessed the inhibition of aluminum corrosion in 2M H2SO4 acid, using black olive oil, and employing gravimetric techniques, and results showed maximum inhibition efficiency of 88.57 %. FTIR analysis identified the presence of carbonyl and hydroxyl functional groups among others, and inhibition mechanism was by adsorption of on metal surface. [

14] Studied the inhibition of aluminum corrosion in HCl solution by four Schiff bases: 2-anisalidine-pyridine; 2-anisalidine-pyrimidine; 2-salicylidine-pyridine; and 2-salicylidine-pyrimidine, using mass loss and thermometric techniques, and obtained good and agreeable inhibition efficiencies using the two methods mentioned. [

15] Compared the inhibition efficiencies of different m-substituted aniline-N-salicylidenes, for corrosion of zinc in tetraoxosulphate IV acid, and found m- CNS as having the best inhibitor performance among the studied inhibitors up to 99 %. The inhibitors were seen to manifest mixed-type inhibition.

[

16] provided a review which reflected the suitability of plant extracts as green inhibitors of metal corrosion, providing effective corrosion protection and adsorption techniques, and included synergistic effects of various plant extracts.

[

17] evaluated the inhibition efficiency of Ficus leaf extract for carbon steel in saline and acidic environments for concentrations of 1, 2, 3 and 4 ppm. The best inhibition efficiencies were 87% for 2ppm and 99% for 1ppm concentration. The review of [

18] reflects that various plant parts such as leaves, roots, stem, bark among others, have been adequately harnessed for the inhibition of the corrosion of different metals and their alloys. [

19] Presented a review which provided insight on the suitability of extracts of plant origin as inhibitors of aluminum corrosion in hydrochloric acid solution, providing their extraction procedures and techniques used for the inhibition studies, and as well proposed gaps which were needed to be filled in future research. [

20] Studied for the corrosion of aluminum in hydrochloric acid by Guiera senegalensis, using weight loss, LPR, FT-IR, and scanning electron microscope techniques, with the result showing increase in inhibition performance with increase in concentration of inhibitor and decrease of inhibition efficiency with increase in temperature. The mechanism of physisorption was deduced from the result of Fourier Transform Infra-Red. [

21] Studied the inhibition of aluminum corrosion by Gmelina arborea extract in HCl and NaOH media, and the findings of the study reflected an increase in inhibition efficiency with increase in the concentration of the inhibitor, with the plant extract exhibiting better inhibition efficiency in the HCl medium. In the work of Oguzie [

22] leaf extracts of these plants: Occimum viridis ( OV ), Telferia occidentalis ( TO ), Azadirachta indica ( AI ) and Hibiscus sabdariffa ( HS ) seed extract of Garcinia kola ( GK ) were tested for their corrosion inhibition efficacy on mild steel in 2 M HCl and 1 M H 2SO4 using gasometric technique at temperatures of 30 and 60 °C, and they showed good inhibition efficiency which also improved in synergy by addition of halide ions.

Aluminum alloy AA6061 of percentage composition 98.6 % Al, 0.8 % of Mg, 0.45 % Si and 0.15 % Cu of thickness 2 mm was cut into a rectangular specimen of 15 mm by 15 mm. The aluminum surface was ground using abrasive papers of between 600-800 grits to remove surface oxides, scratches and irregularities, and then polished with a polishing cloth and alumina to obtain a mirror-like face. This was followed by degreasing with ethanol to remove oils and surface contaminants, then rinsed properly with deionized water and air-dried in a dust free environment.

Hibiscus sabdariffa leaves extract (HSLE) was prepared from fresh leaves of the Hibiscus sabdariffa plant. The leaves were thoroughly washed to remove any dirt or impurities, air-dried to preserve their bioactive constituents. The dried leaves were ground into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle, and the resulting powder was subjected to solvent extraction using 70 % v/v of ethanol The powdered plant was soaked in 400 ml of ethanol for 48 hours at a temperature of 30 oC, with occasional stirring and shaking, then followed by filtration using a qualitative filter paper to obtain a filtrate of approximately equal volume as the original volume of ethanol used. The filtrate was evaporated to dryness to obtain a dry mass of 7 g as reported in [

23]. Subsequently, concentrations of Hibiscus sabdariffa were prepared thus: by dissolving 0.1g in 1dm3 of water to obtain 100 mg/dm3, 0.5 g in 1 dm3 of water to obtain 500 mg/dm3, 1g in 1dm3 of water to obtain 1000 mg/dm3, 2 g in 1 dm3 of water to obtain 2000 mg/dm3 and 3 g in 1 dm3 of water to obtain 3000 mg/dm3.

2.2 Weight Loss Measurement

The experimental setup for corrosion testing involved exposing the prepared aluminum specimens to corrosive environments with and without the presence of Hibiscus sabdariffa extract. The corrosion tests were conducted using various techniques, including immersion tests and weight loss techniques. The immersion test was carried out as follows. Aluminum coupons of dimensions 15 by 15 by 2 mm were suspended in beakers with glass hooks and rods, inside beakers where the test solutions were put with total immersion in the test solution of volume 300 ml at 30 oC. The control experiment was carried out by immersion of aluminum coupons in hydrochloric acid without HSLE. The immersed coupons were retrieved at 24-hour intervals progressively for 120 hours, cleaned with deionized water, dried and re-weighed. The weight loss was calculated and recorded as a difference between the initial weight and subsequent weight of the metal coupon. The results were in triplicates. The corrosion rate and inhibition efficiency were calculated using the formulae.

Where mdd = millimeters per square decimeter per day,

= weight loss = Final weight –initial weight (W2 –W1) in milligram

A = surface area exposed to corrosion ( in square decimeter)

T= Time of exposure (in days)

W1 = weight of metal before exposure to the corrosive media

W2 = Weight of metal after dipping into the corrosive solution.

I.E = Inhibition efficiency

A three-electrode cell was set up, which consists of the working electrode (the sample material, in this case the aluminum coupon), the reference electrode (saturated calomel electrode) and the counter electrode (silver/silver chloride electrode). The sample material was polished with emery paper of grades 200-1000. The electrolyte solution that will initiate the corrosion process was chosen; in this case, it is 0.1 M and 1 M HCl acid solution. The electrochemical cell was filled with an electrolyte solution of high-purity reagents and deionized water. The potentiodynamic polarization was initiated by applying a potential sweep at a potential range of ±250 mv and scan rate of 0.333 mv/s. The readings were taken after 0.5 hours of immersion with the solution unstirred at 30 oC. The potentiodynamic polarization curve was recorded as applied potential versus the current density. Measurements were taken in triplicates to ensure reproducibility.

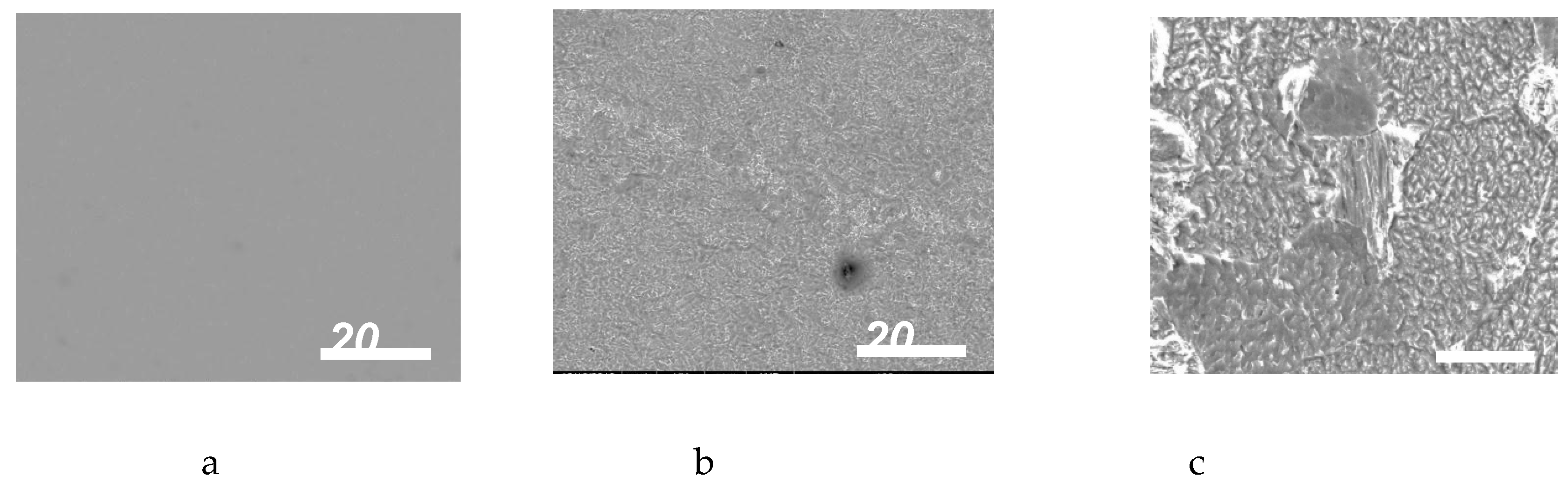

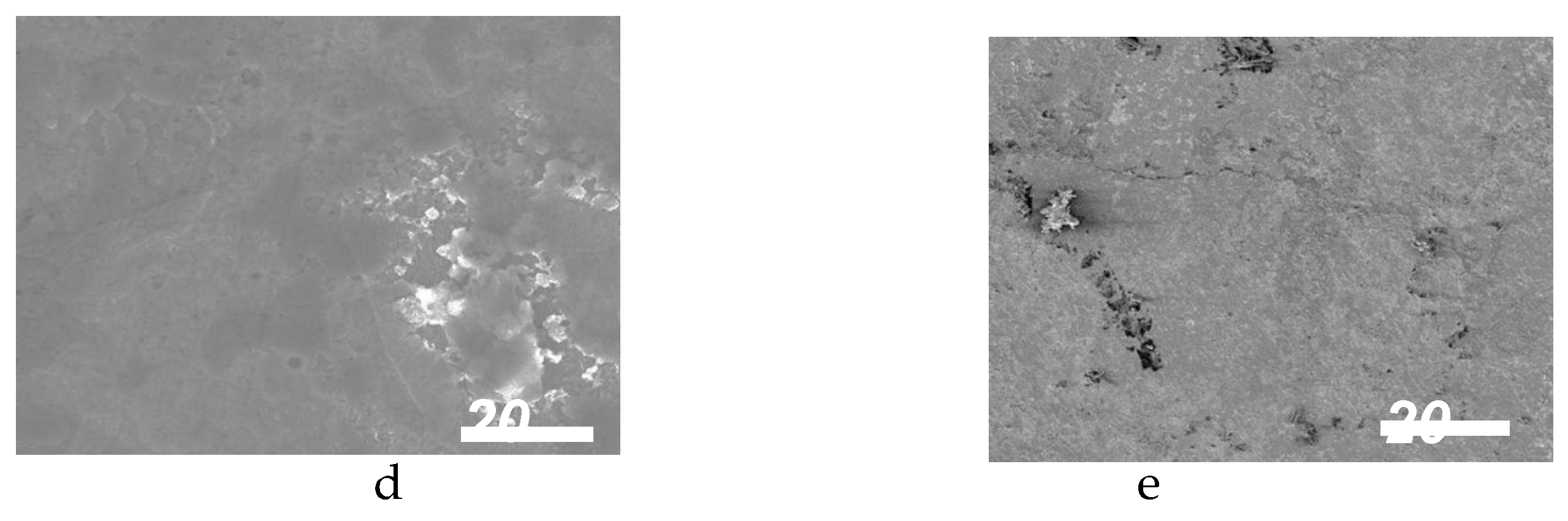

Surface investigations of the metals were undertaken by SEM examinations of the electrode surfaces exposed to different test solutions using XL-30FEG scanning electron microscope. Aluminum specimens of dimensions 15 x 15 x 2 mm were cleaned as previously described and immersed for 24 h in the blank solutions (hydrochloric acid) with or without the inhibitors under study at 30 oC. The metal sample was washed with distilled water and dried in warm air before being subjected to surface examination. The already prepared sample was mounted on the SEM sample holder with the aid of conducting adhesives. The prepared sample holder was loaded into the SEM chamber, whereby the electron beam was focused on the sample for image capture to examine its surface morphology. The SEM images obtained were analyzed to identify surface structural defects and the results were documented for further analysis.

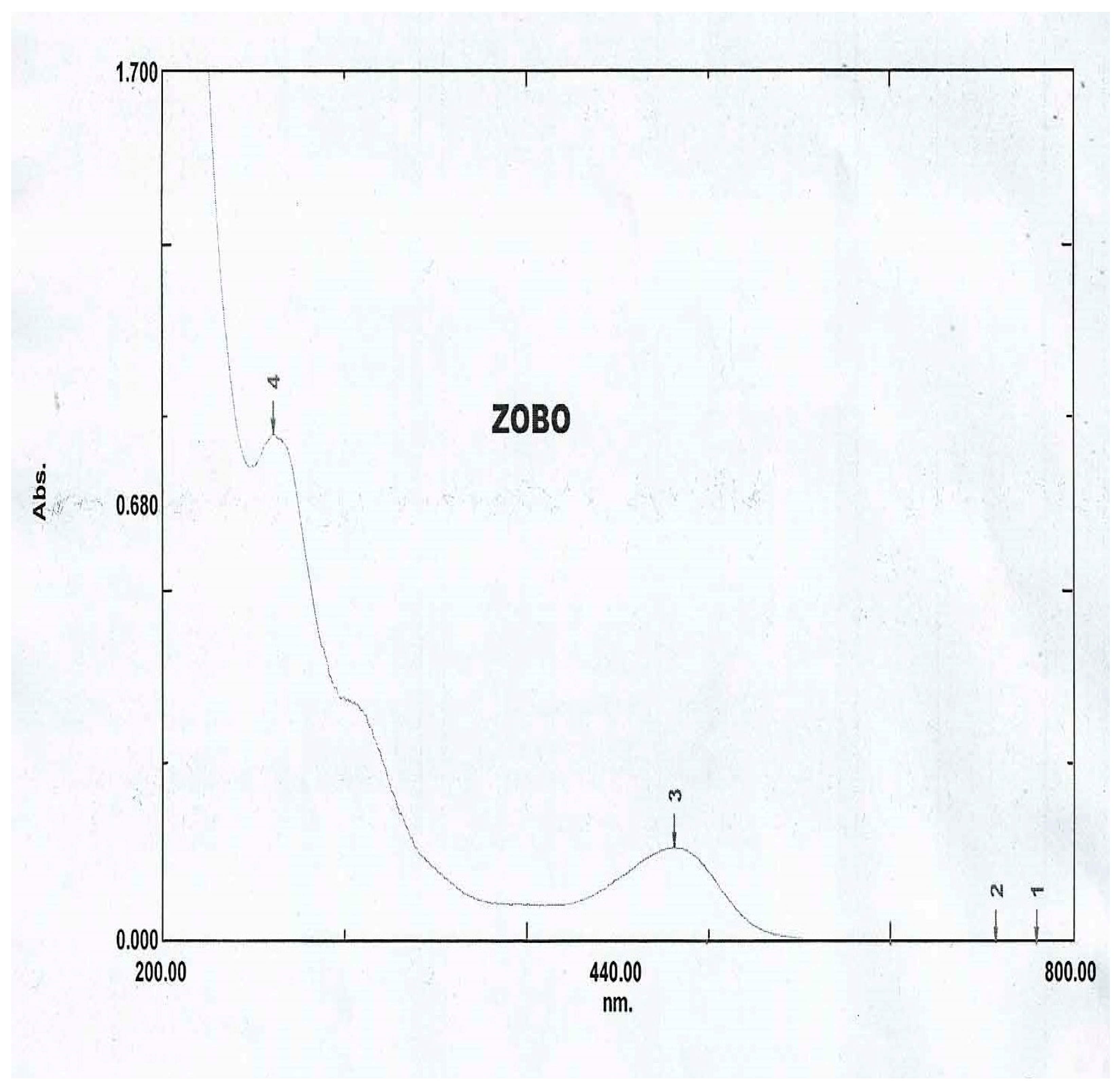

The UV-Visible spectrophotometer was turned on and allowed to warm up. The wavelength range for the analysis was set at 200-800 nm, where 200-400 nm and 400-800 nm represent ultraviolet and visible regions respectively. Standard concentration of 100 mg/dm3 of Hibiscus sabdariffa (HS) was prepared by dissolving 0.1 g of HS in 1 dm3 of water. The glass cuvette was selected, cleaned and filled with the pure solvent used for the sample, in this case water. The cuvette was placed in the spectrophotometer to run a blank measurement and zero the instrument. Afterwards, the cuvette was filled with the sample solution and the outside of the cuvette was wiped with a lint-free tissue to remove any fingerprints or smudges. The spectrophotometer was used to obtain the absorbance (A) at each wavelength.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Gravimetric Results

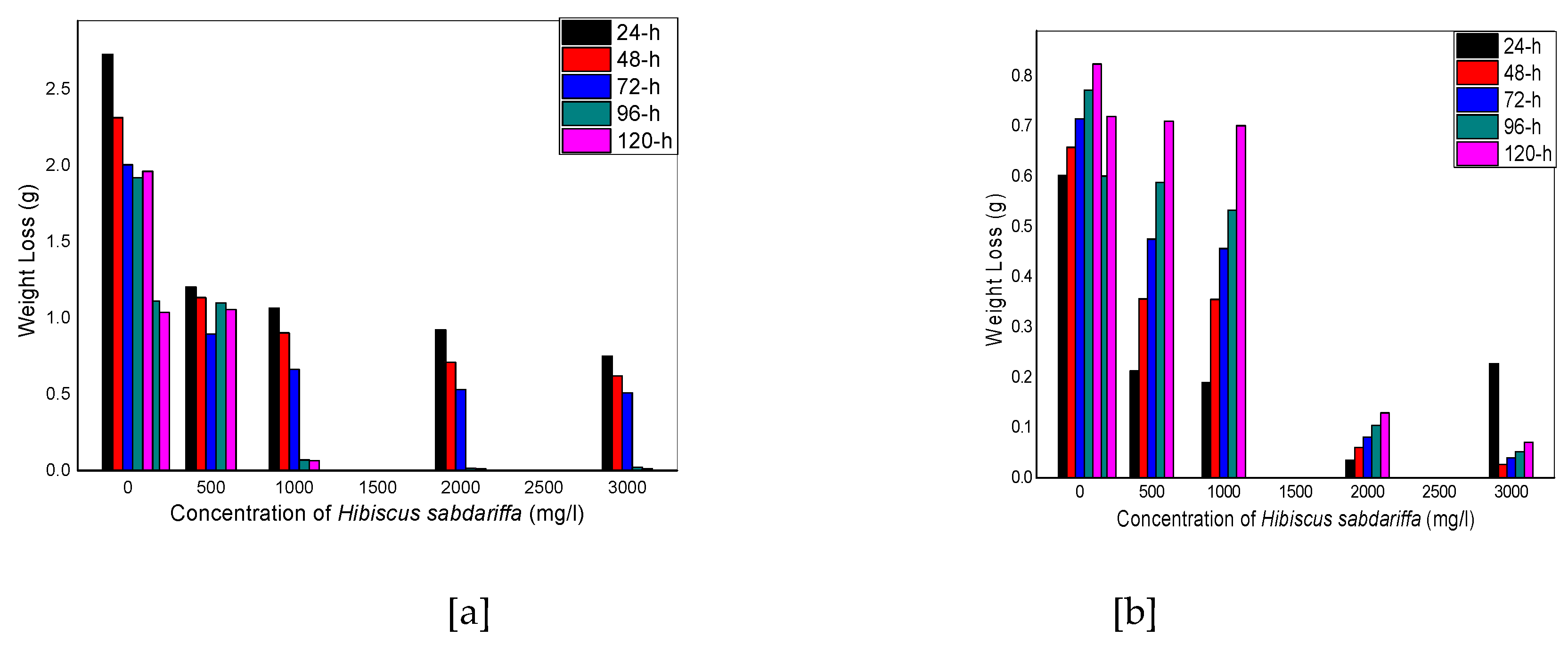

The results of the weight loss measurements for corrosion of aluminum in 0.1 M and 1 M HCL in the presence and absence of HSLE are presented in

Table 1 and Figures 1 to 3below.

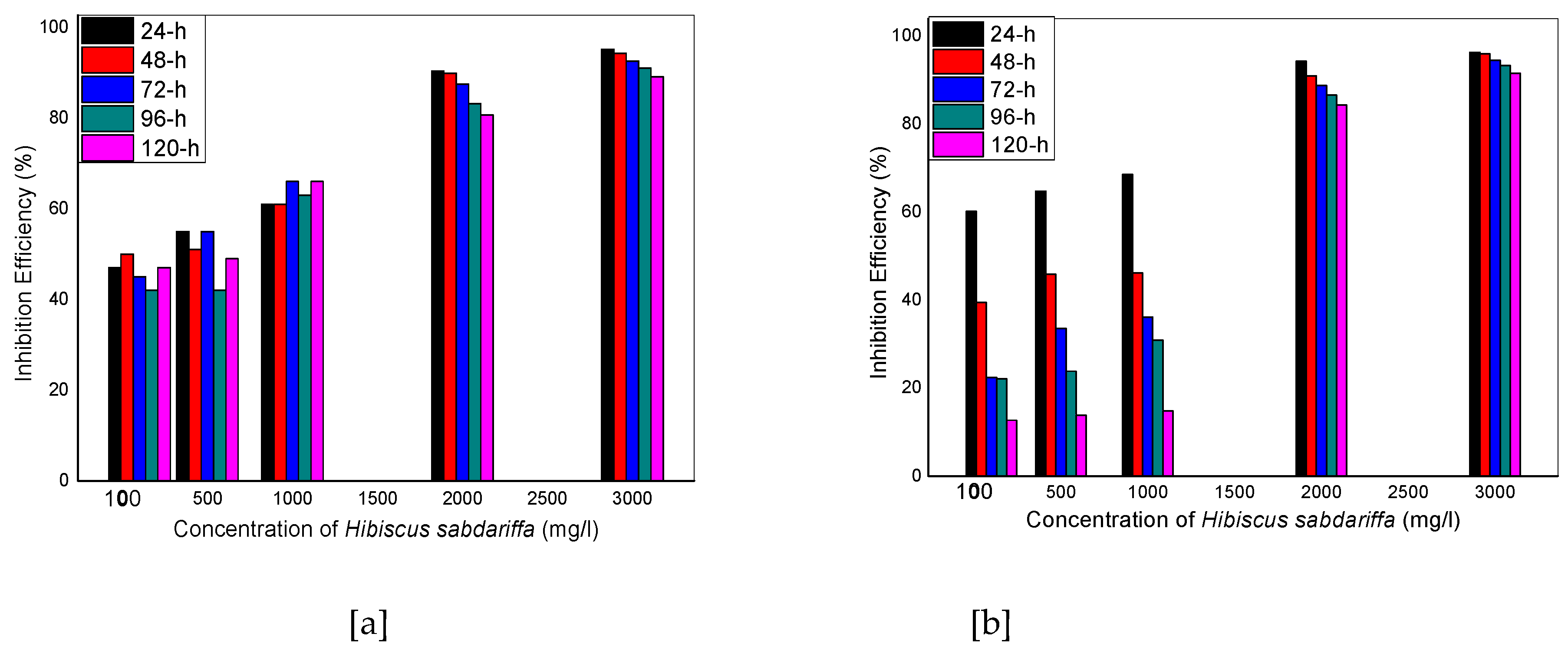

Table 1 depicts the lowest inhibition efficiencies for the blank solution which starts to increase moderately for the 500 mg/dm3 and 1000 mg/dm3 concentrations of HSLE. The inhibition efficiency seems to get to a peak at 2000 mg/dm3 and does not show significant rise at 3000 mg/dm3 showing excellent inhibitor performance of 95.1 % for the 0.1 M HCl. A similar trend is observed for the 1 M HCl with the highest inhibitor performance at 96.2 %. The trend of corrosion rate is observed to be highest for the blank solution (0.1 and 1 M HCl), but there is slight decrease in corrosion rate at higher time intervals with the introduction of HSLE, signifying a decrease in corrosion activities, which approaches to almost zero at the highest inhibitor concentration of 3000 mg/l at 120-hour interval. However, the corrosion rate is raised beyond 24 hours interval for the 1 M HCl corrosive solution at all HSLE concentrations used. The findings presented in the given work suggest that the Hibiscus sabdariffa leaf extract (HSLE) exhibits excellent corrosion inhibition properties for mild steel in both 0.1 M and 1 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) solutions. The inhibition efficiency increases with increasing HSLE concentration. The findings of the present study are conformable with the work of [

24], who used exudate gum from Raphia hookeri to inhibit the corrosion of mild steel in HCl and H2SO4 solutions and obtained inhibition efficiencies up to 92 %. In the same vein, [

25] achieved inhibition efficiency up to 95 %, with Occimum viridis, Azadirachta indica, and Telfairia occidentalis extracts as corrosion inhibitors of on mild steel in acidic media.

Figure 1.

Weight loss versus concentration of Hibiscus sabdariffa for aluminum coupons in (a) 0.1 M and (b) 1 M HCl at 30 oC

Figure 1.

Weight loss versus concentration of Hibiscus sabdariffa for aluminum coupons in (a) 0.1 M and (b) 1 M HCl at 30 oC

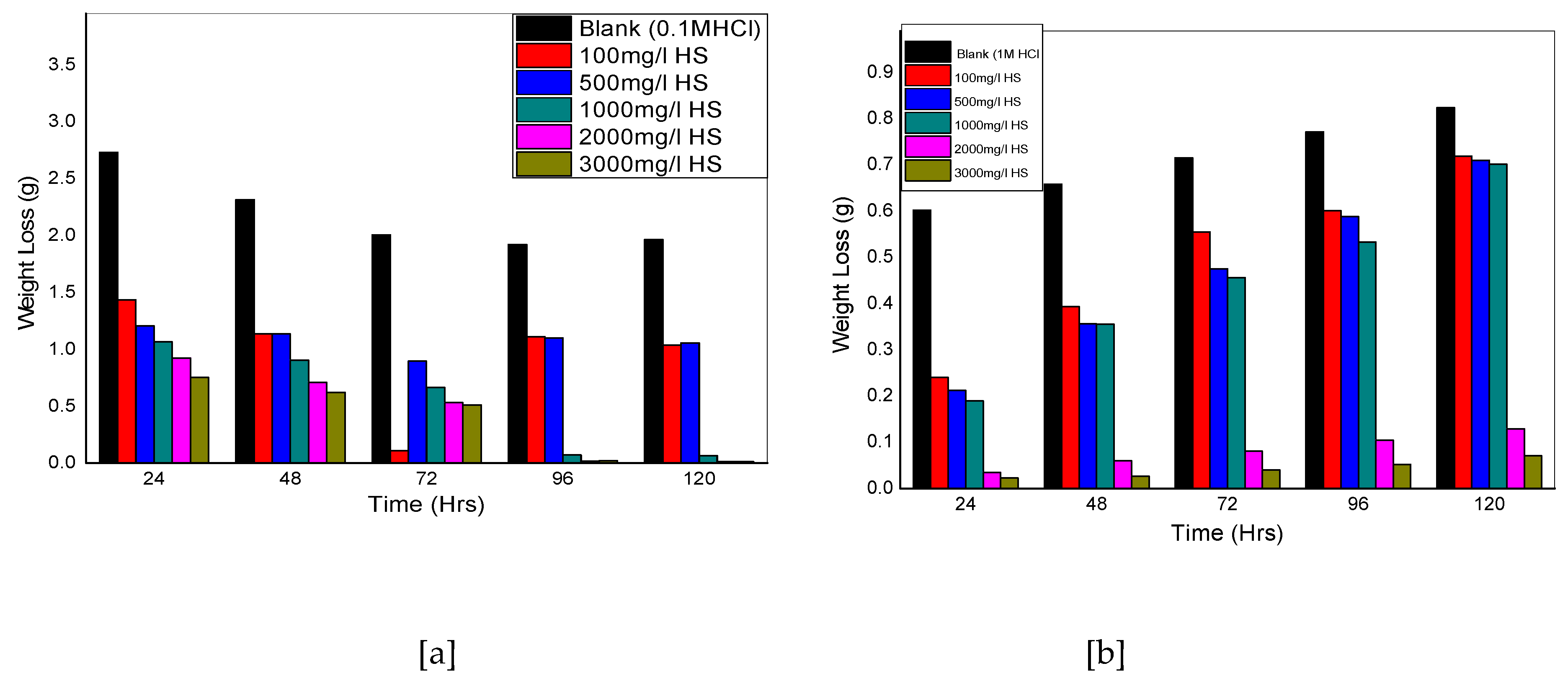

Figure 2.

Weight loss versus time for aluminum coupons in (a) 0.1 M and (b) 1 M HCl in the presence and absence of Hibiscus sabdariffa at 30 oC

Figure 2.

Weight loss versus time for aluminum coupons in (a) 0.1 M and (b) 1 M HCl in the presence and absence of Hibiscus sabdariffa at 30 oC

Figure 3.

Inhibition Efficiency versus concentration of Hibiscus sabdariffa for aluminum coupons in (a) 0.1 M and (b) 1 M HCl at 30 0C

Figure 3.

Inhibition Efficiency versus concentration of Hibiscus sabdariffa for aluminum coupons in (a) 0.1 M and (b) 1 M HCl at 30 0C

Figure 1a shows a decrease in weight loss as the concentration of HSLE is increased from 100 mg/dm3 to 3000 mg/dm3, which continues at various time intervals from 24 hours to 120 hours. The trend is somehow different for figure 1b whereby the weight loss follows the downward path from 100 mg/dm3to 3000 mg/dm3 for 24 hours’ time interval and increases afterwards. Corrosion rate is highest for the blank uninhibited solutions (0.1 and 1 M HCl) for Figures 2 a and b, and starts to reduce in Figure 2a, with the introduction of HSLE at concentration 100 mg/dm3to 3000 mg/dm3, and continues to decrease even at higher time intervals, almost approaching zero at 120 hours. Figure 2b shows a decrease in corrosion rate up to 24 hours’ time interval for concentrations 100 mg/dm3 to 3000 mg/dm3 but starts to increase at 48 hours and beyond. Figure 3ashows increase in inhibition efficiency of HSLE from concentrations of 100 mg/dm3 to 3000 mg/dm3 for the time intervals of 24 hours to 120 hours, up to 95.1 %. Figure 3b shows an increase in inhibition efficiency with an increase in concentrations of HSLE from 100 mg/dm3 to 3000 mg/dm3 reaching 96.2 % up to 24 hours but starts to decrease at 48 hours up to 120 hours. The above trend suggest that the corrosion inhibition performance of HSLE improves with higher concentrations, with the inhibitor being more stable in 0.1 M HCl as compared to 1 M HCl solution with prolonged immersion time. The findings of this study agree with the work of [

26] who evaluated the inhibition of mild steel corrosion in HCl solutions using Vernonia amygdalina extract and obtained greater as the inhibitor concentration and immersion time in the corrosive media increased. In a like manner, Oguzie [

27] obtained an increase in inhibition efficiency for the study of Gongronema latifolium extract as inhibitor of mild steel corrosion in acidic environment, with increase in inhibitor’s concentration and immersion time as well.

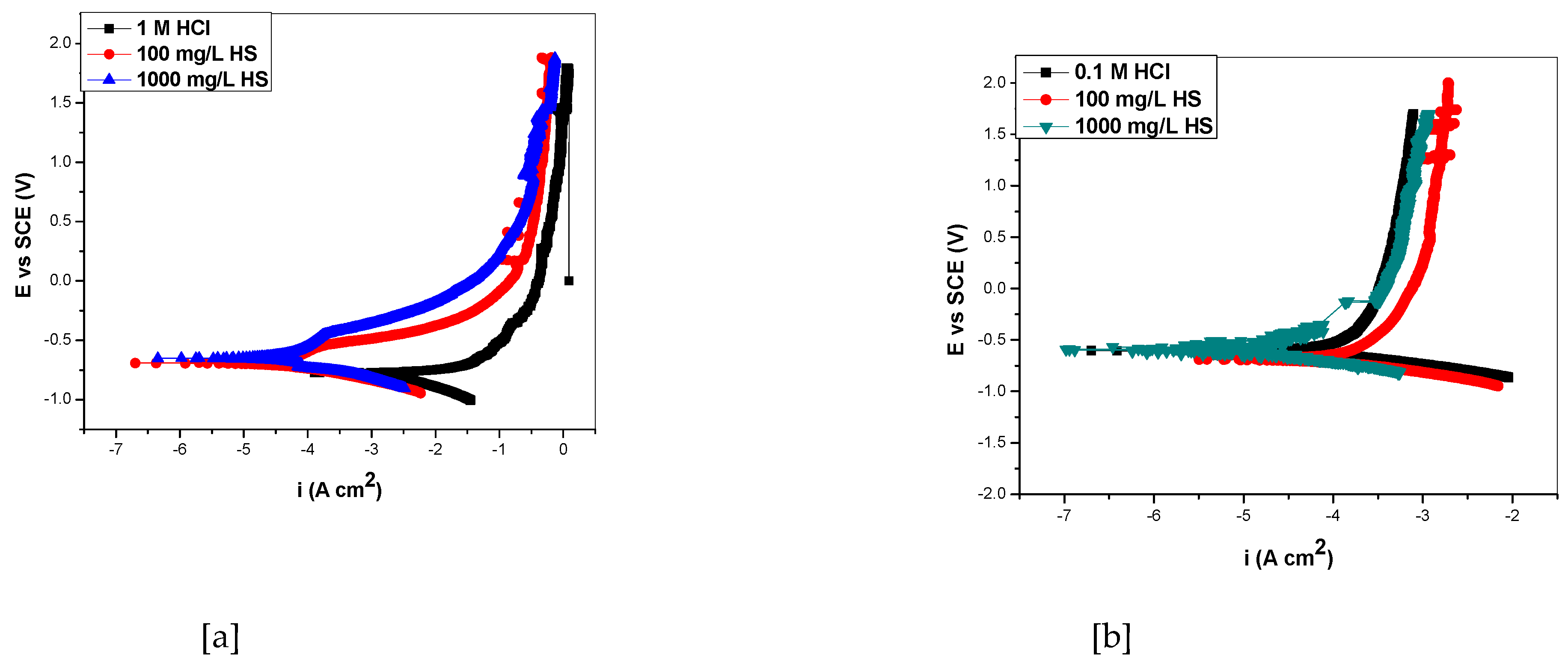

3.2. Potentiodynamic Polarization Results

Potentiodynamic polarization graphs for aluminum in HS in 0.1 M and 1.0 M HCl at 30 0C are as seen in figure 4. Electrochemical variables like corrosion potential (Ecorr) and corrosion current densities (Icorr) are presented in

Table 2

Figure 4.

PdP graphs for aluminum in (a) 1 M and (b) 0.1 M HCl with or without HS.

Figure 4.

PdP graphs for aluminum in (a) 1 M and (b) 0.1 M HCl with or without HS.

Figure 4 showed that the addition of Hibiscus sabdariffa shifted the Ecorr slightly to more positive (anodic) values and shifted the cathodic and anodic branches to lower values, with the anodic effect being greater, and the effect was more pronounced in the 1 M HCl acid solution, thus showing the character of a mixed-type inhibitor, as was also reported in Okore et al. (23) The inhibition efficiency increased up to 80.7 % in 1 M HCl and 80.6 % in 0.1 M HCl, respectively.

Table 2 shows the polarization variables for aluminum in the corrosive and inhibited solutions respectively. There is a shift in Ecorr values for HS in 1 M HCl as 60.2 ev and 122.5 ev for 100 mg/dm3 and 1000 mg/dm3 concentrations of HS respectively; and 38.1 ev and 28 ev for 100 mg/dm3 and 1000 mg/dm3 concentrations of HS as well, in 0.1 M HCl. There was a reduction in current density Icorr by 41.9 and 92.4 μAcm-2 for 100 mg/dm3 and 1000 mg/dm3 of HS in 0.1 M HCl; as well as 39.4 μAcm-2 and 75.2 μAcm-2 for 100 mg/dm3 and 1000 mg/dm3 in 0.1 M HCl. The Ecorr and the Icorr values for the uninhibited solution are -708.3 mV and 107.2 μA/cm² respectively. The HSLE effectively retarded the corrosion potential, current density and increased the inhibition efficiencies to maximum values of 86.2 % and 86.1 % for 1 M and 0.1 M inhibited solutions respectively. The shift in corrosion potential (Ecorr) values as obtained in HS is consistent with the work of [

28], who showed how various organic compounds were used as corrosion inhibitors to modify Ecorr through the formation of protective layers on metal surfaces, and retarding corrosion reaction processes in acidic environments. The reduction in current density (Icorr) as observed in the current study agrees with the findings of Roberge [

29], which showed how inhibitors effectively reduce Icorr by adsorbing onto the metal surface and thus retard the electrochemical reaction process. The increase in inhibition efficiency with higher concentrations of HS is in line with findings of Ahmed et al. [

28] which showed that the effectiveness of corrosion inhibitors improves with concentration and affords better coverage of the metal surface through adsorption of the inhibitor on the surface of the metal. This also aligns with the mechanisms described by Roberge [

29], that adsorption and formation of protective films are key factors in the inhibition process.

3.3. Langmuir Adsorption Isotherm

Langmuir isotherms suggest that each site holds one adsorbed species [

30] can be represented by

C = concentration of the inhibitor,

= degree of surface coverage

K = the equilibrium constant.

The plot of against C is characteristic of Langmuir adsorption isotherm. The equation requires that a plot of against C should be linear with a positive intercept on axes and with a slope of unity

Data for the Langmuir adsorption isotherm is presented in figure 8 as shown below.

Figure 5.

Langmuir isotherm for aluminum in (a) 0.1 M and (b)1 M HCl containing Hibiscus sabdariffa at 30oC

Figure 5.

Langmuir isotherm for aluminum in (a) 0.1 M and (b)1 M HCl containing Hibiscus sabdariffa at 30oC

Figure 5 reveals a linear relationship between and concentration of HS, with correlation coefficients (R2) of 0.95 and 0.98 for HS in 0.1 M and 1 M HCl, a slope of 0.95 and 1.02 for HS in 0.1 M and 1 M HCl acid solution.

The linearity of the plot shows some degree of agreement with the Langmuir behaviour, with correlation coefficients (R2) of 0.95 and 0.98 for HS in 0.1M and 1 M HCl, a slope of 0.95 and 1.02 for HS in 0.1 M and 1 M HCl acid solution. The linearity of the graph, and the slope and correlation coefficient (R2) approximating to unity (1) proves that Langmuir adsorption isotherm is suitable for the adsorption of HS plant extract on aluminum surface in HCl acid solution.

3.3.1. Linear Regression Analysis

Standard free energy

values were determined from the values of K

ads using the equation below.

= the standard free energy of the adsorption process

Kads = adsorption equilibrium constant

R = Gas constant

= 8.314 J/K/mol

T = Temperature

= 30 oC

Kads and figures are presented in 3 as shown below.

Table 3.

Adsorption isotherm parameters obtained from the corrosion data for aluminum coupons in 0.1 M and 1 M HCl containing Hibiscus sabdariffa

Table 3.

Adsorption isotherm parameters obtained from the corrosion data for aluminum coupons in 0.1 M and 1 M HCl containing Hibiscus sabdariffa

Isotherm Intercept Slope K Ln K R2

(KJ

Langmuir (0.1 M HCl)

Aluminum(30oC) 370.70867 0.9507 0.0027 5.9160.9545 -14.903

Langmuir (1 M HCl

Aluminum(30oC) 248.3519 0.9695 0.0040 5.5220.9754 -13.910 |

The calculated values of standard free energy of adsorption process were negative for all the Langmuir adsorption isotherm ranging from -14.903. to -13.910 for 0.1 M and 1 M HCl respectively. Standard free energy values lower than -20 kJmol-1is consistent with physisorption mechanism of adsorption, while those more negative than -40 kjmol-1 involve chemisorption mechanism of adsorption. The values obtained for the present study correspond with physisorption adsorption mechanism. The calculated values of standard free energy of adsorption process for the Langmuir adsorption isotherm ranging from -14.903 kJ/mol to -13.910 kJ/mol for 0.1 M and 1 M HCl, respectively, suggest a physisorption adsorption mechanism.

This is in line with the findings of Aksu [

31], which showed that physisorption typically occurs with weaker interactions, leading to less negative free energy values, while chemisorption involves stronger bonding and thus more negative values.

3.4. SEM RESULTS

From Figure 9 (a-e), it could be clearly seen that dipping the metal in the aggressive media brought serious damage to the aluminum surface which was more devastating in the 1 M HCl media. From the result, the inhibitor is said to reduce the deterioration of the metal by forming a passive layer which barred the corrosive ions from getting to the metal surface and consequently lowered the rate of corrosion. This agrees with the SEM analysis of Geethamani and Kasthuri [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38] on the potential of expired pharmaceutical drugs in preventing the deterioration of mild steel in acidic solution. The result revealed the lowering of mild steel deterioration. This was achieved by putting a strongly fixed inert layer on the surface of the metal, which helped to isolate the corrosive ions from the surface of the metal

Figure 9.

(a) SEM pictures for polished aluminum surface; (b), (c) SEM photographs of aluminum surface dipped in 0.1M, 1 M HCl; (d) SEM pictures for aluminum dipped in 0.1M HCl containing HS (e), SEM pictures for aluminum dipped in 1M HCl containing HS

Figure 9.

(a) SEM pictures for polished aluminum surface; (b), (c) SEM photographs of aluminum surface dipped in 0.1M, 1 M HCl; (d) SEM pictures for aluminum dipped in 0.1M HCl containing HS (e), SEM pictures for aluminum dipped in 1M HCl containing HS

3.5. UV-Visible Analysis Results

The result of the UV-Visible analysis is presented in figure 10 below.

Figure 6.

UV-Visible absorption spectra for Hibiscus sabdariffa

Figure 6.

UV-Visible absorption spectra for Hibiscus sabdariffa

From figure 10, two clear bands could be seen at wavelengths of maximum absorbance 537nm and 274 nm at positions 3 and 4 respectively. Moderate absorption occurs at wavelength 537 nm indicating presence of anthocyamins, in the green-yellow region. Strong absorption at 274 nm indicates the presence of organic compounds like phenolics and flavonoids, commonly found in plant extracts. These compounds contribute to the antioxidant properties of Hibiscus sabdariffa, and its color too. From literature,

536 nm is the absorption specification of anthocyanin cynidin [

39] Sukwattanasinit, Burana-Osot and Sotanaphun [

40] identified two peaks at 380 nm and 530 nm respectively from UV-Visible analysis of

Hibiscus sabdariffa flower signifying the presence of hydroxycinnamates and anthocyanins, respectively. Wafa Gamal Abdalh Al Shoosh [

41] identified red and violet bands from uv-visible analysis of

Hibiscus sabdariffa at 530 nm and 540 nm, respectively. The red band contains cyanidin and the violet band contains delphinidin which are the two major anthocyanins present in

Hibiscus sabdariffa. The identified compounds in Hibiscus sabdariffa contribute significantly to the corrosion inhibition properties. The flavonoids and phenolic compounds donate their pie electrons from the hydroxyl group and aromatic ring to the metal surface to form chelates which reduce the electrochemical process or become adsorbed on the metal surface and create a barrier between the metal surface and the corrosive materials. The antioxidant properties of anthocyanins reduce oxidative stress and hence mitigate the oxidative process and corrosion consequentially. By leveraging the corrosion inhibition properties of HS, it could be applied in marine, oil and gas and construction industries to protect metals from corrosion and increase their longevity.

Conclusion

1. The study demonstrates that Hibiscus sabdariffa leaf extract is a potent green inhibitor for aluminum corrosion in hydrochloric acid.

2. The corrosion rate decreased significantly with the increase in HSLE concentration, giving the optimum inhibition efficiencies of 95.1 % and 96.2 % for 3000 mg/l concentration of HSLE in 0.1 M and 1 M HCl, respectively.

3. The inhibition efficiency remained high within the time interval of 120 hours, showing that HSLE is stable with time.

4. Potentiodynamic polarization studies revealed that HSLE acts as a mixed-type inhibitor, affecting both anodic and cathodic reactions, and retarded the corrosion current density (Icorr).

5. Langmuir Adsorption Isotherm confirms the adsorption of the phytochemicals of HSLE onto the aluminum surface, using physisorption mechanism of adsorption.

6. The identified flavonoids, phenolic compounds and anthocyanins from UV-Visible analysis provided further evidence of the corrosion inhibition properties of Hibiscus sabdariffa.

Recommendations for Future Research

1. Further studies should explore the detailed molecular interactions between HSLE constituents and aluminum surfaces using advanced surface analysis techniques.

2. Investigations into the long-term stability and performance of HSLE in various industrial conditions are necessary.

3. Comparative studies with other plant-based inhibitors can provide a broader understanding of the efficacy and applicability of natural extracts in corrosion inhibition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization- Okore G. J.; Methodology- Okore, S.; Investigation, Ehirim A.I; Writing: original draft preparation- Okeke, P. I.; writing review and editing- Amanze, K. O.; Data curation- Nleonu, E. C. Supervision- Ejiogu, B. All authors have read and agreed to publish the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the 271 articles. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kanika C. and Mobin M. (2024). Phytochemicals/Plant extract as corrosion inhibitors for aluminum in NaCl solutions, Phytochemistry in corrosion science, 1st edition, 1-13. eBook ISBN 9781003394631.

- Silvia J. S., Nathalia M. Pereira Q., Adriana S., Ribeiro J. T. (2023). Green Corrosion inhibitors Based on Plant Extracts for Metals and Alloys in Corrosive Enviroment: A Technological and Scientific Prospection. Applied Science, 13 (13):7482-7482. Doi: 103390/app13137482.

- Qingyang L., Zijian S., Han H., Saddick D., Linhua J., Wanyi W., Hongqiang C. (2020). A novel green reinforcement corrosion inhibitor extracted from waste Platanus acerifolia leaves. Construction and Building Materials, 260:119695-. [CrossRef]

- Desai P. S., Falguni P., (2023). An overview of sustainable green inhibitors for aluminum in acid media. AIMS environmental science, 10(1):33-62. [CrossRef]

- Gloria Z., Ivan, M., Zora, P., Andrea, P., Ivana, M., Ante, P., Dusan, C. (2023). Green Inhibition of Corrosion of Aluminum Alloy 5083 by Artemisia annua L. Extract in Artificial Seawater. Molecules, 28(7):2898-2898. [CrossRef]

- Philipp, R. R. (2023). A comprehensive review of corrosion inhibition of aluminum alloys by green inhibitors. Canadian Metallurgical Quarterly, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Vundavalli, V., Sravanth., V., Poiba, M. V. (2023). Study of Green Corrosion Inhibitor of Aegle marmelos Leaves Extract in Acidic Medium. Key Engineering Materials, 943:117-126. [CrossRef]

- Rajesh N., Jesudoss, H., Nagarajan, J., Vignesh, C., Barile, P., Shenbaga, V., Thangagiri, B. J., Winowlin, J., Omar, A., Al-Khashman, M., Brykov, N, Antoaneta, E. (2022). Green Corrosion Inhibition on Carbon-Fibre-Reinforced Aluminum Laminate in NaCl Using Aerva Lanata Flower Extract. Polymers, 14(9):1700-1700. [CrossRef]

- Kanakapura, K., Namitha, P., Rao, S., Addanki, R. (2022). A brief insight into the use of plant products as green inhibitors for corrosion mitigation of aluminum and aluminum alloys. Canadian Metallurgical Quarterly, 61(4):429-441. [CrossRef]

- Claudia, M., Méndez, C., Gervasi, G., L., Pozzi, A., Esther, A. (2023). Corrosion Inhibition of Aluminum in Acidic Solution by Ilex paraguariensis (Yerba Mate) Extract as a Green Inhibitor. Coatings, 13(2):434-434. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, A., Chowdhury, N., Hossain, M., Mir, S., Ahmed, M., Aminul, I., Saiful, I., Masud, R. (2023). Green tea and tulsi extracts as efficient green corrosion inhibitors for aluminum alloy in alkaline medium. Heliyon, 9(6): e16504-e16504. [CrossRef]

- Abdelazi S., Benamira M., Messaadia L., Boughoues Y., Lahmar H., Boudjerda, A. (2021). Green corrosion inhibition of mild steel in HCl medium using leaves extract of Arbutus unedo L. plant: An experimental and computational approach. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 619:126496-. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed J., Mohammed, M. S., Isah. J. (2022). Evaluation of Anticorrosion Potential of African Black Olive (Canarium schweinfurthi) Oil as Green Corrosion Inhibtor on Aluminum Sheet in Acidic Medium. Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management, 26(11):1881-1885. [CrossRef]

- Bansiwal, A., Anthony, P., Mathur, P. S. (2000). Inhibitive effect of some Schiff bases on corrosion of aluminum in hydrochloric acid solutions. British Corrosion Journal, 35(4):301-303. [CrossRef]

- Talati, J. D., Desai, M. N., Neesha, S. (2005). Meta-substituted aniline-N-salicylidenes as corrosion inhibitors of zinc in sulphuric acid. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 93(1):54-64. [CrossRef]

- Al, Jahdaly, B. A., Yasmin, R., Maghraby, A., Ibrahim, K., RShouier, R., Mohamed, M., Taher, R., El-Shabasy, M. (2022). Role of Green Chemistry in Sustainable Corrosion Inhibition: A review on Recent Developments. Materials today sustainability, 20:100242-100242. [CrossRef]

- Haider, A., AlMashhadani, M., Kadhim, A., Fatma, A., Khazaal, A., Salman. M., Mustafa, M., Kadhim., Z., Abbas M., Sajad, K., Farag, H., Fadhil, H. (2021). Anti-Corrosive Substance as Green Inhibitor for Carbon Steel in Saline and Acidic Media. (IOP publishing), 1818(1):012128-. [CrossRef]

- Jasdeep, K., Neha, D., Akhil, S. (2021). Corrosion Inhibition Applications of Natural and Eco-Friendly Corrosion Inhibitors on Steel in the Acidic Environment: An Overview. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering, 1-18. [CrossRef]

- Narasimha, R. (2020). Green Compounds to Attenuate Aluminum Corrosion in HCl Activation: A Necessity Review. (Springer International Publishing, 3(1):21-34. [CrossRef]

- Ayuba A. M. and Abubakar M. (2021). Inhibiting aluminum acid corrosion using leaves extract of guiera senegalensis. Journal of Fundamental and Applied Sciences, 13(2):634-656. [CrossRef]

- Ayuba, A., Muhammad, M., Auta, A., Shehu, N. U. (2020). Comparative Study of the Inhibitive properties of Ethanolic Extract of Gmelina arboreaon Corrosion of Aluminum in Different Media. Applied journal of Environmental Engineering Science, 6(4): 374-386doi: 10.48422/IMIST.PRSM/AJEES-V6I4.23455.

- Oguzie, E. (2008). Evaluation of the inhibitive effect of some plant extracts on the acid corrosion of mild steel. Corrosion Science, 50, 2993-2998. [CrossRef]

- Okore, G., Ejiogu, B., Okeke, P., Amanze, K., Okore, S., Oguzie, E., Enyoh, C. E. Lawsonia inermis as an Active Corrosion Inhibitor for Mild Steel in Hydrochloric Acid. Appl. Sci.2024, 14, 6392. [CrossRef]

- Umoren, S. A., and Obot, I. B. (2008). Mild steel corrosion inhibition by acid extract of leaves of Hibiscus sabdariffa as a green corrosion inhibitor and sorption behaviour, Corrosion Science, 50(8), 2173-2180. [. [CrossRef]

- Oguzie, E. E. (2008). Corrosion inhibition of mild steel in acidic media by extracts of Ocimum viridis and Telfairia occidentalis. Corrosion Science, 50(12), 2993-2998. [. [CrossRef]

- Okafor, P. C., Odoemelam, S. A., and Inegbenebor, A. O. (2008). Corrosion Inhibition of Mild Steel in HCl Using Vernonia amygdalina Extract. African Journal of Biotechnology, 7(25), 4823-4826.

- Oguzie, E. E. (2008). Corrosion Inhibition of Mild Steel in Acidic Media Using Gongronema latifolium Extract. African Journal of Biotechnology, 7(25), 4513-4517.

- Ahmed, S. F., et al. (2020). "Corrosion inhibitors: A review." Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 9(3), 2467-2480.

- Roberge, P. R. (1999). "Handbook of Corrosion Engineering." McGraw-Hill, New York.

- Arenas, M.A., Bethencourt, M., Damborenea, de J. & Marcos, M. (2003) The inhibitor behaviour of CeCl3 for both AA5083 alloy and galvanized steel in aerated NaCl solutions.

- Aksu, Z. (2005). Application of biosorption for the removal of organic pollutants. Bioresource Technology, 97(18), 2195-2210.

- Geethamani, P &Kasthuri, P.K(2015). Adsorption and corrosion inhibition of mild steeel in acidic media by expired pharmaceutical drug, Cogent chemistry, 1, ( 1), 1-11.

- Adindu Chinonso Blessing, Kalu Georgina, Ikezu Uju Paul, Ikpa Chinaka B. and Okeke Pamela I. (2024) Molecular Docking ADMET &ADF Predictions of Cinnamonumzylanicum for Prostate Cancer Inhibition. Journal of Material Science, Research and Reviews. 7, 3, 392-426.

- Okore, G., Ejiogu, B., Okeke, P., Amanze, K., Okore, S., Oguzie, E., Enyoh C. E., (2024) Lawsonia inermis as an active corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in hydrochloric acid. Applied Sciences, 14, 6392, 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Okeke P. I., Nleonu E. C., Hamza I., Elyor B., Omar D,, Amanze K. O., Adindu B. C., Nizamuddin A., Avni B. and Abeer A. AlObaid. (2024) Chrysophyllum albidum extract as a new and green protective agent for metal. Canadian Metallurgical Quarterly. The Canadian Journal of Metallurgy and Materials Science, Taylor & Francis Group. Pages 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Okeke P. I., Maduka O. G., Emereonye R. U., Akalezi C. O., Mughele K., Achinihu I. O. Azubuike N. E. (2015) Corrosion Inhibition Efficacy of Cninodosculus chayamansa Extract on Aluminum Metal in Acidic and Alkaline Media. The International Journal of Science and Technoledge. 3(3): 227-234. ISSN 2321-919x.

- Okeke P. I., Emeghara K. C., Ibe Geogeline C., Oseghale T.I., Maduka O. G., Emereonye R. U. (2016) Inhibitive Action and Adsorption Character of Water Extract of Solanum melongena for the Corrosion of Mild Steel in 0.5 M H2SO4. IOSR Journal of Applied Chemistry 9 (2) 20-25. e-ISSN 2278-5736. [CrossRef]

- Nleonu E. C., Rajesh H., Ubaka K. G., Onyemenonu C. C., Ezeibe A. U, Okeke P. I., Mong O. O., Hamza I., Nadia A., Seong-Cheol K., Omar D., Ebenso E. E. and Mustapha T. (2022) Theoretical Study and Adsorption Behavior of Urea on Mild Steel in Automotive Gas Oil (AGO) Medium. Lubricants 10, 157, 1-13.

- Harbone J.B. (1958). Biochemistry of phenolic glycosides, Biochemistry Journal, 70 (1), 22-28.

- Sukwattanasinit T., Burana-osot J. and Sotanaphun (2016). Simple and rapid spectrophotometric method for quality determination of roselle (HS), Thai Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 40 (4), 194-199.

- Wafa G. A. (1997). Chemical Composition of Some Roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa) Genotypes, M. Sc Thesis, University of Khartoum, 123 pages.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).