Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Moment Frames and Connections

2.1. Evolution of Steel Moment Frame Design

2.2. Advancements in Modelling Techniques

2.3. Integration of Machine Learning

2.4. Experimental Investigations and Numerical Modelling

2.5. Future Directions

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

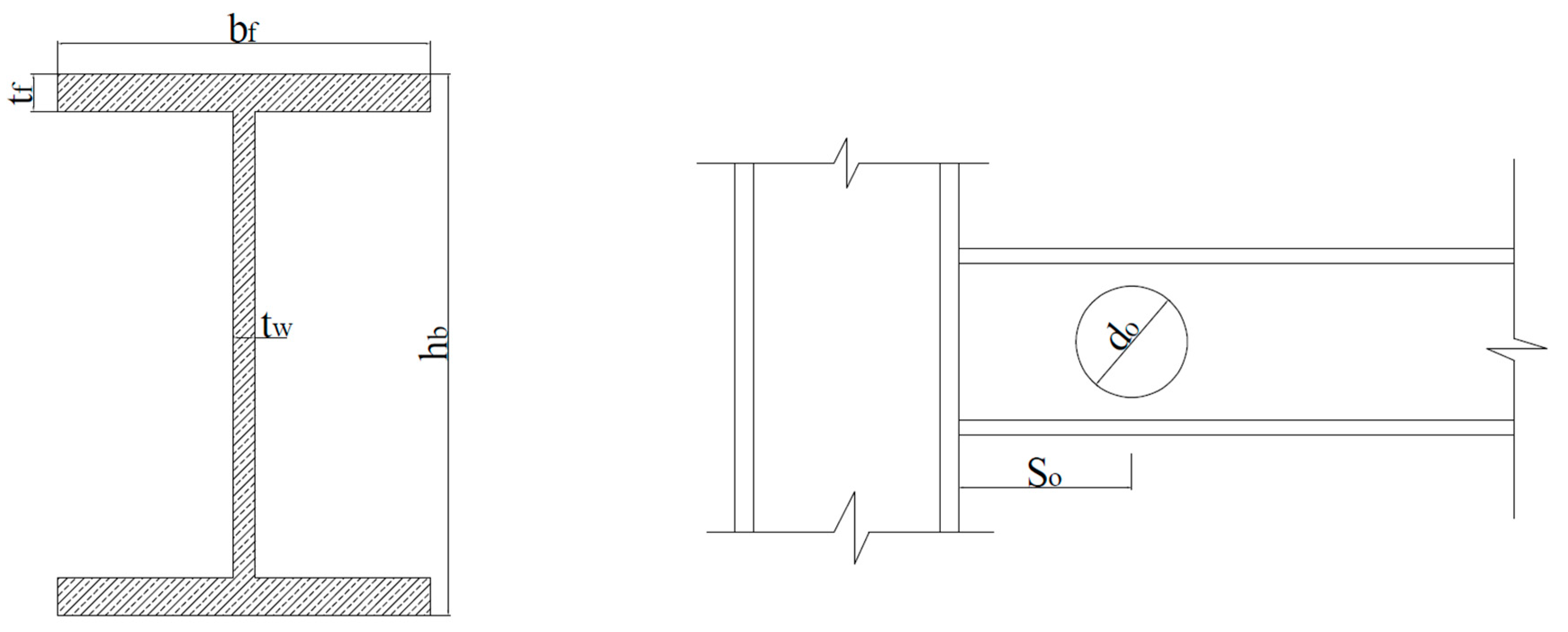

- 251 specimens and 247 FE models of RWS connections

- 14 solid webbed-beam connections as benchmarks

- Both bare steel and composite RWS connections

- Various connection types (welded and bolted extended end-plate)

- Different test setups (cantilever, cruciform, and frame arrangements)

- Isolation of connection behaviour

- Clear insights into local effects of web openings

- Simplified data interpretation

Integrated Methodology

- Detailed local behaviour data from cantilever tests

- Broader frame behaviour modelled through the Gupta and Krawinkler approach

| Reference | Study | Connection | Number of Sections | Total Number of Considered Tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tsavdaridis et al. [16] | FE | Welded | 1 | 3 |

| Tsavdaridis and Papadopoulos | FE | BEEP-3-R | 1 | 1 |

| Zhang et al. [17] | Experiment | Welded | 1 | 1 |

| Boushehri et al. [18] | FE | Welded | 4 | 48 |

| Nazaralizadeh et al. [19] | FE | BEEP-4-R | 1 | 1 |

| Xu et al. [20] | Experiment | Welded | 1 | 5 |

| Almutairi and Tsavdaridis [13] | FE | BEEP-4-R | 1 | 95 |

| Total Number of FE/Experimental tests | 154 | |||

3.2. Calibration of IMK Bilin Parameters

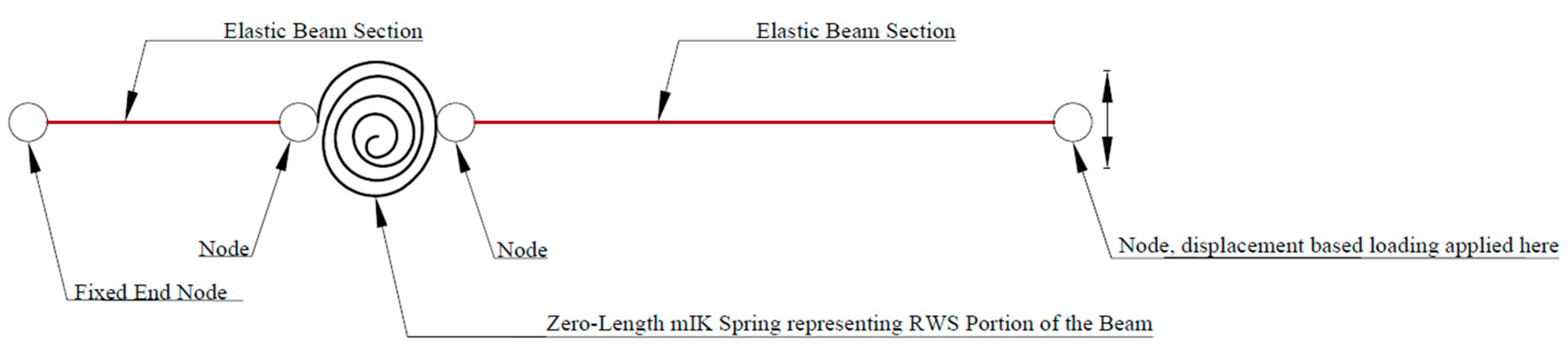

3.2.1. Model Setup

3.2.2. Loading Conditions

- Control Parameter: The story drift angle (θ) is used as the primary control parameter.

-

Loading Sequence:

- ○

- Initial cycles: 6 cycles each at θ = 0.00375, 0.005, and 0.0075 rad

- ○

- Intermediate cycles: 4 cycles at θ = 0.01 rad

- ○

- Higher deformation cycles: 2 cycles each at θ = 0.015, 0.02, 0.03, and 0.04 rad

- Continued loading: Increments of θ = 0.01 rad, with 2 cycles per step

- Boundary conditions matched those used in the FE models and Experimental tests.

3.2.3. Calibration Method

- Cyclic deterioration parameters for strength and post-capping strength (Lamda_S, Lamda_C)

- Cyclic deterioration parameter for unloading stiffness (Lamda_K)

- Strain-hardening ratios (as_Plus, as_Neg)

- Post-capping rotations (theta_pc_Plus, theta_pc_Neg)

3.2.4. Analysis and Post-Processing

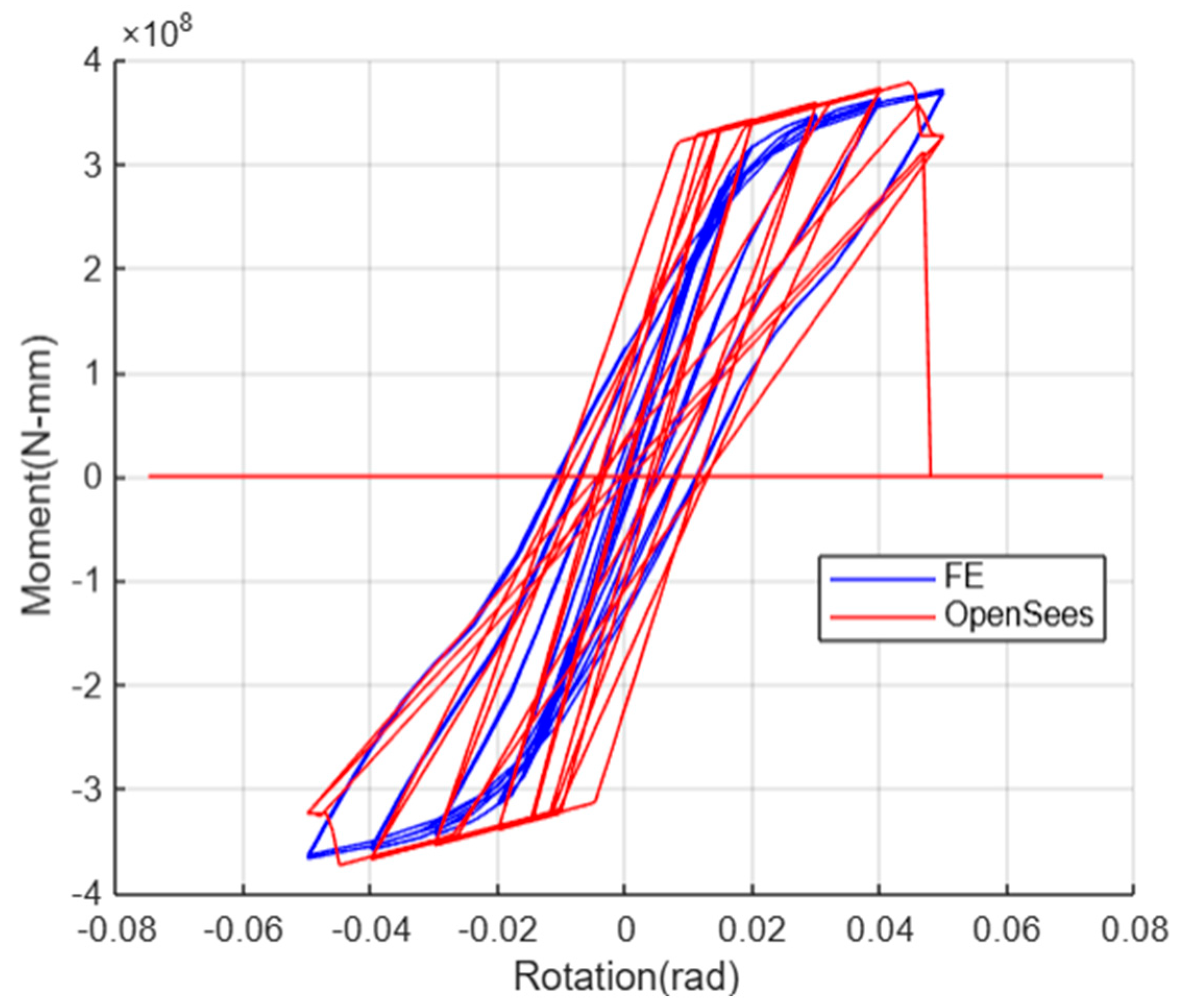

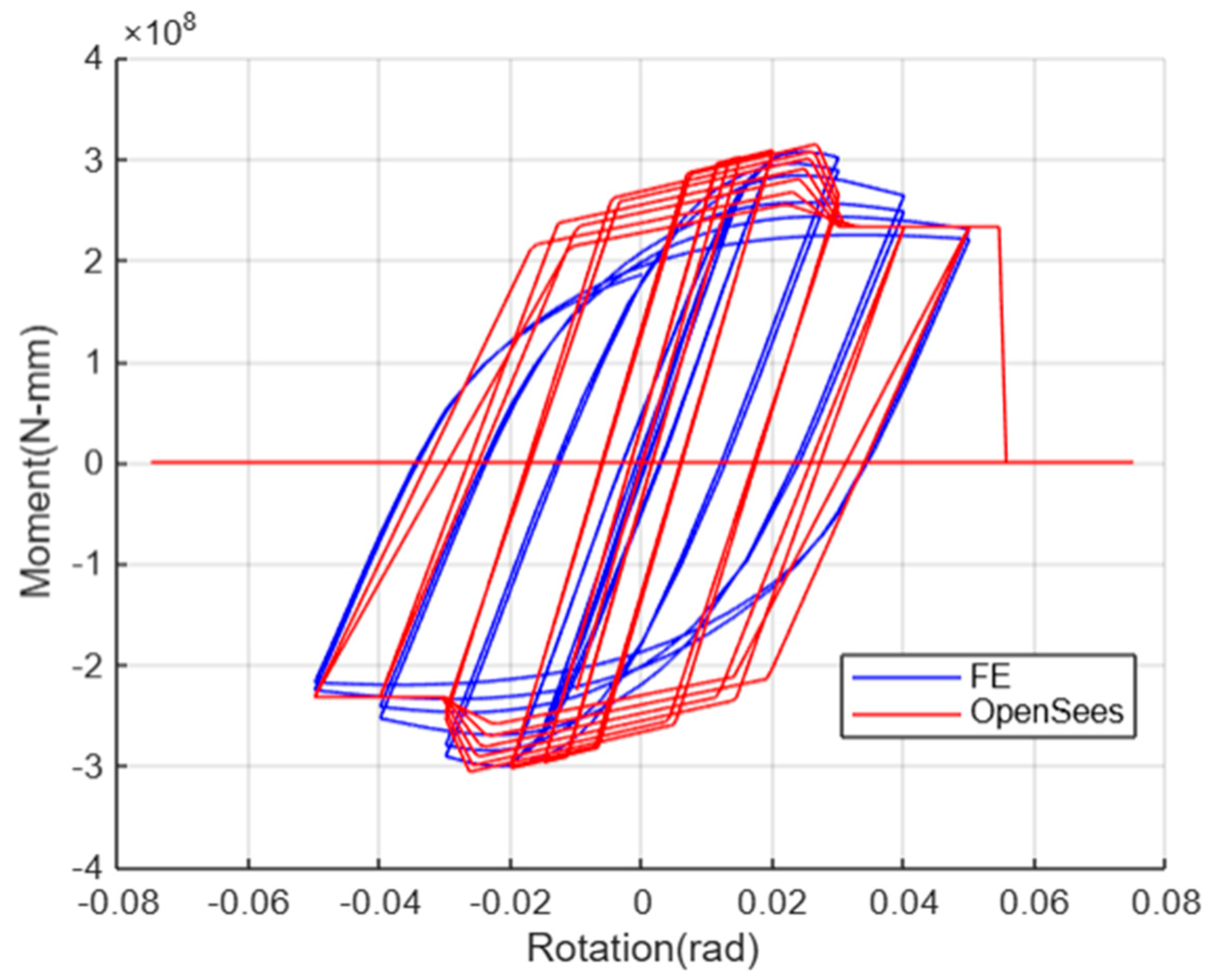

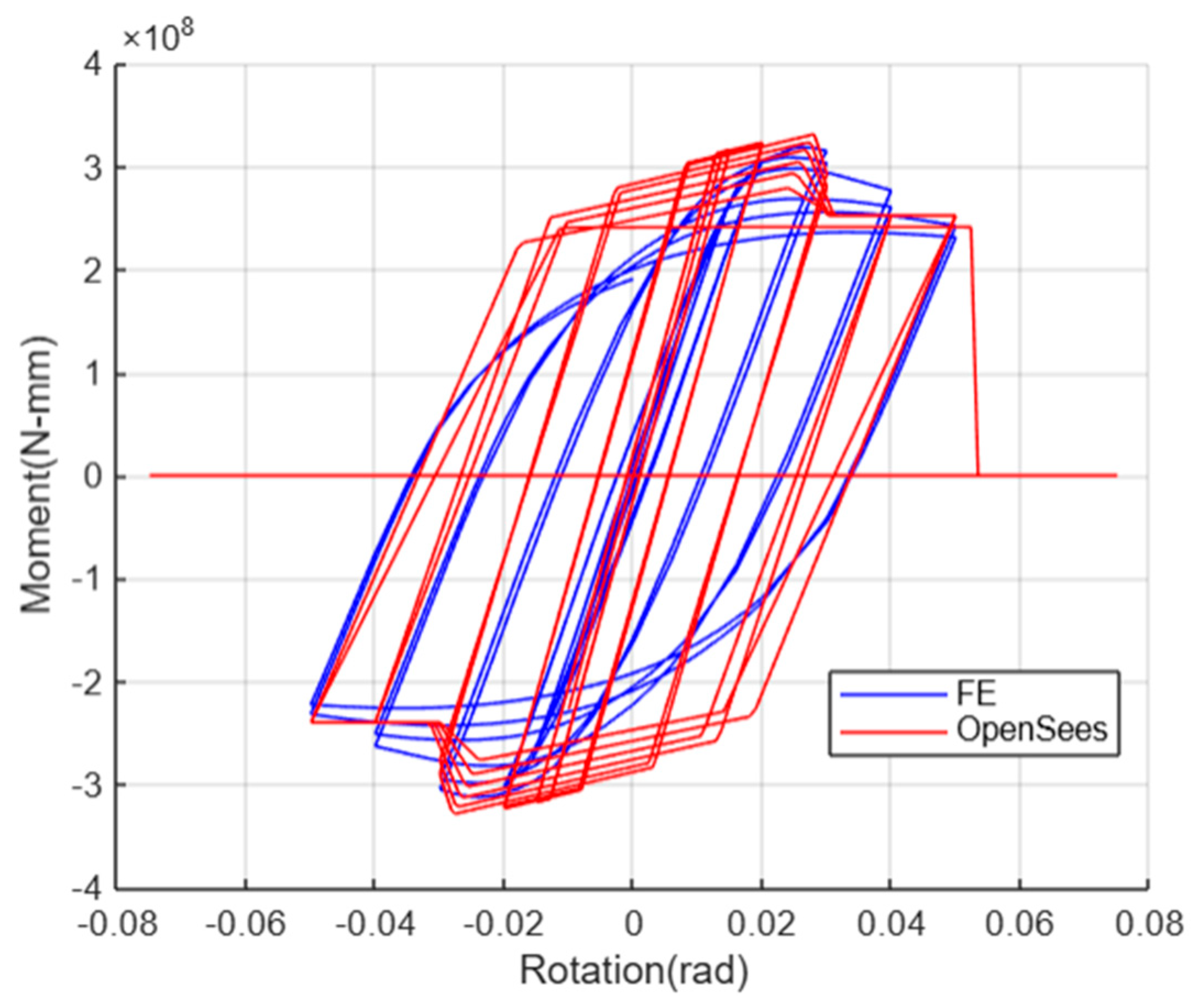

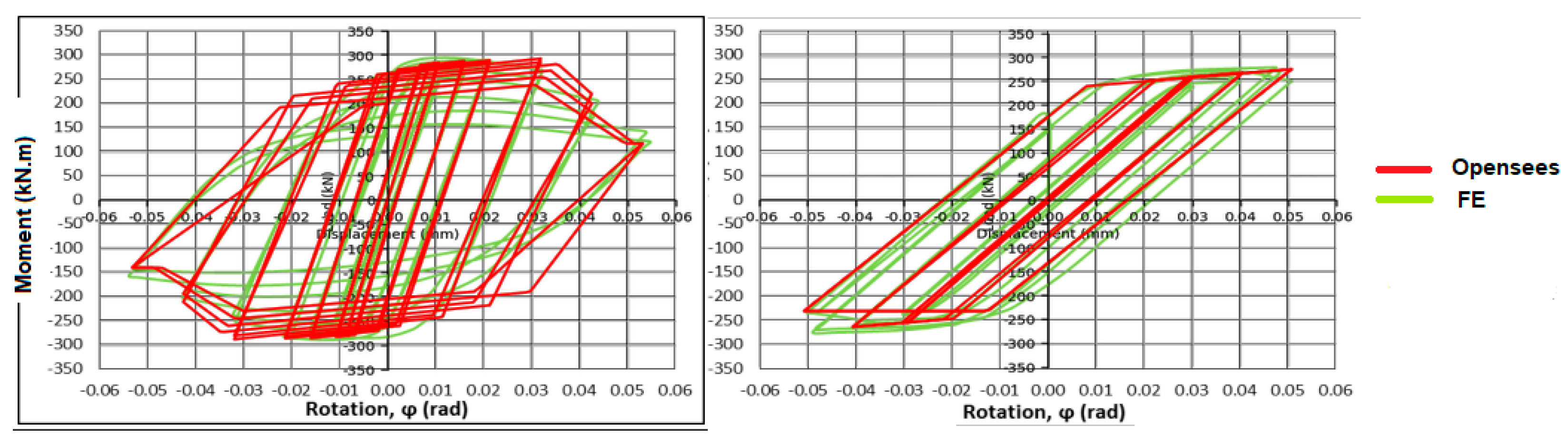

3.2.5. Model Accuracy

3.2.6. Database Scope

3.2.7. Results of Calibration

- Web Opening Size Effect

- Stiffness Degradation: Noticeable degradation in stiffness is observed, primarily controlled by the parameter.

- Strength Preservation: No significant degradation in strength occurs, suggesting limited influence of the parameter.

- Absence of Post-Capping Phase: The analysis does not show the development of a post-capping phase, indicating minimal influence of the parameter.

- Post-Capping Phase: A distinct post-capping phase is observed, characterised by significant strength decrease after reaching maximum capacity.

- Enhanced Energy Dissipation: Larger hysteresis loops indicate higher energy dissipation during cyclic loading.

- More Pronounced Deterioration: All three lambda parameters (, , and ) play significant roles in shaping the structural response.

- Web Opening Position Effect

- Strain Hardening Ratio: As the distance of the centreline of the web opening from the column face increases, the strain hardening ratio decreases.

- Beam Length Effect

- Energy Dissipation: As the beam length increases from 3 meters to 15 meters, there is a noticeable decrease in energy dissipation. This is likely reflected in smaller hysteresis loops for longer beams.

- Stiffness: The increase in beam length is accompanied by a significant decrease in stiffness. This relationship between length and stiffness is consistent with fundamental beam theory, where stiffness is inversely proportional to the length.

- Performance Implications: The reduction in both energy dissipation and stiffness with increased length suggests that longer beams may be more susceptible to larger deformations and potentially reduced energy dissipation performance.

- Web Opening Size: Influences the overall deterioration pattern and energy dissipation capacity.

- Web Opening Position: Affects the strain hardening behaviour, potentially impacting the beam's post-yield response.

- Beam Length: Directly impacts the beam's stiffness and energy dissipation capabilities, with longer beams exhibiting reduced performance in these aspects.

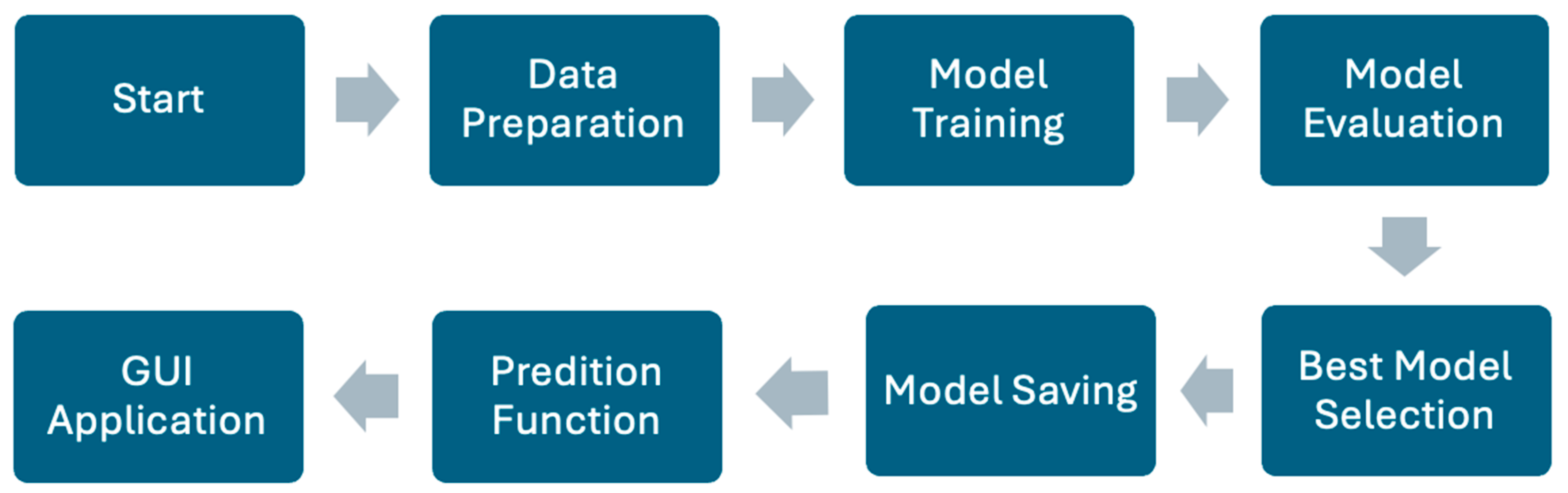

3.3. Machine Learning and Deep Learning Implementation

- Random Forest (RF),

- Neural Network (NN) / Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) Regressor,

- Support Vector Regression (SVR),

- Gradient Boosting (GB),

- XGBoost (XGB), and

- Deep Learning (DL).

Code Structure and Implementation:

- Overview:

- Data Preparation and Feature Engineering:

- : Web slenderness ratio

- : Flange slenderness ratio

- : related to Lateral-torsional buckling slenderness

- : Opening height ratio

- : Edge distance ratio

- : Yield strength

- Model Development:

- Random Forest Regressor

- Neural Network (MLPRegressor)

- Support Vector Regression (SVR)

- Gradient Boosting Regressor

- XGBoost Regressor

- Deep Learning model (using TensorFlow/Keras)

- Model Training and Evaluation:

- Cross-validation techniques:

- Purpose: To ensure the model's performance is robust and generalisable.

- Implementation: The code uses K-Fold cross-validation (with 5 folds).

-

Process:

- ○

- The data is split into 5 subsets.

- ○

- The model is trained on 4 subsets and tested on the remaining one.

- ○

- This process is repeated 5 times, with each subset serving as the test set once.

- Advantage: This approach provides a more reliable estimate of the model's performance on unseen data, reducing the risk of overfitting.

- Understanding Evaluation Metrics: R² vs. Database Error:

- R² quantifies how well the model captures overall trends in connection behaviour.

- Database error focuses on the accuracy of predictions for specific RWS connection geometry and configuration scenarios.

- R² provides a comprehensive view of the model's performance across various seismic scenarios.

- Database error highlights the model's accuracy for RWS connection configurations.

- Multi-Metric Approach to Model Assessment:

- MSE (Mean Squared Error): Measures the average squared difference between predicted and actual values.where n is the total number of FE or Experimental tests, yᵢ is the actual value, and ŷᵢ is the predicted value.

- MAE (Mean Absolute Error): Measures the average absolute difference between predicted and actual values.

- R2 Score: Indicates the proportion of variance in the dependent variable predictable from the independent variable(s).where ȳ is the mean of the actual values.

- RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error): The square root of MSE, providing a metric in the same units as the target variable.

- MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error): Measures the percentage difference between predicted and actual values.

- Spearman Correlation: Assesses how well the relationship between predicted and actual values can be described using a monotonic function.where dᵢ is the difference between the ranks of corresponding values of yᵢ and ŷᵢ.

- Best Model Selection:

- MSE and RMSE are sensitive to large errors, crucial for avoiding significant underestimations in structural capacity.

- MAE provides a straightforward measure of average error magnitude.

- R2 and Spearman correlation ensures the model captures the overall trends in the data.

- MAPE gives a percentage view of errors, useful for comparing across different scales of output.

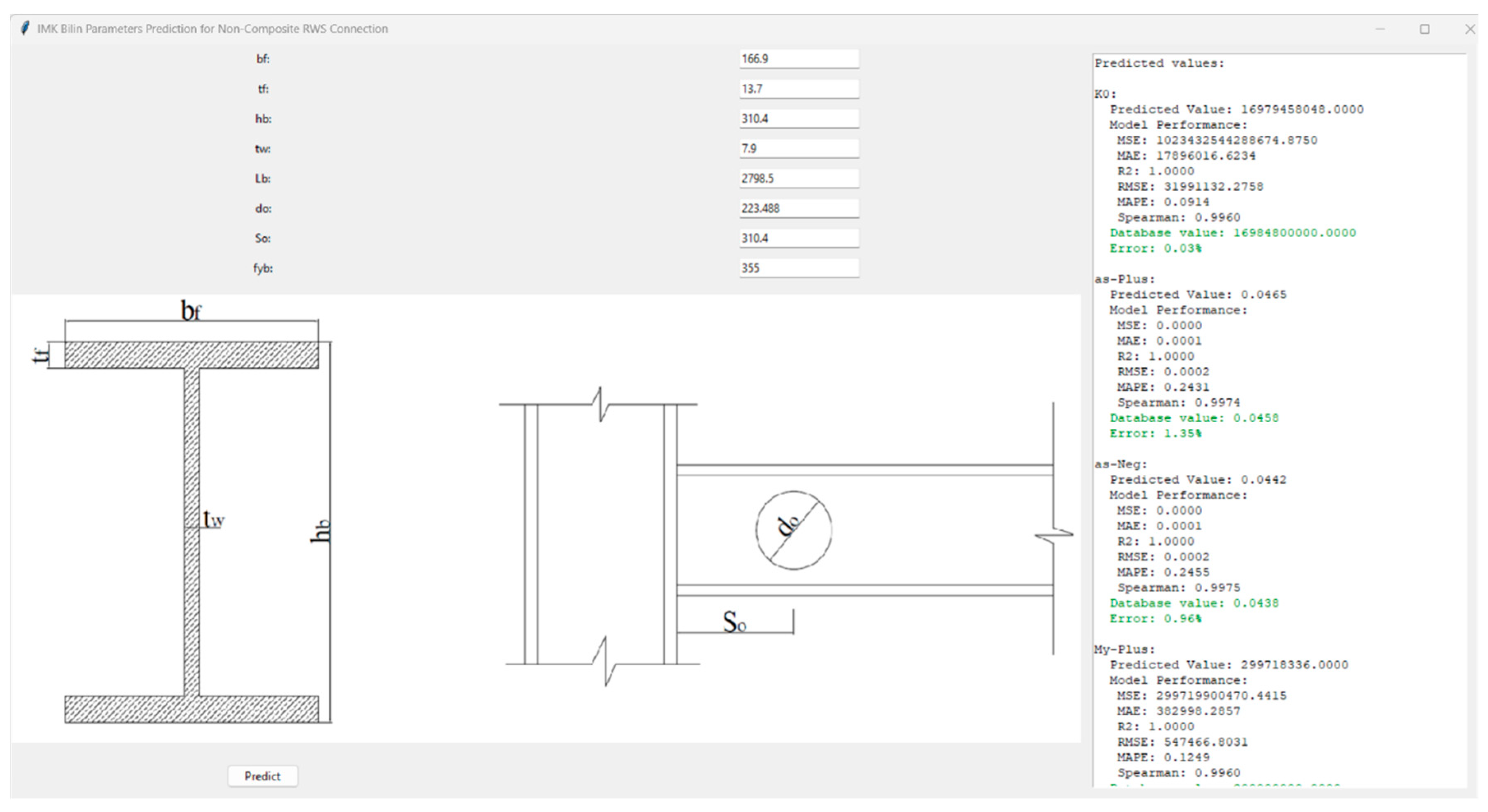

- Prediction and Application:

- Engineering Significance:

- Initial stiffness (K0)

- Yield moments (My-Plus, My-Neg)

- Various lambda factors (Lamda-S, Lamda-C, Lamda_A, Lamda_K)

- Rotation capacities (theta_p_Plus, theta_p_Neg, theta_pc_Plus, theta_pc_Neg)

- Ultimate rotations (theta_u_Plus, theta_u_Neg)

- Ductility factors (D_Plus, D_Neg)

- Practical Implementation:

3.4. Results

3.4.1. Model Performance Overview

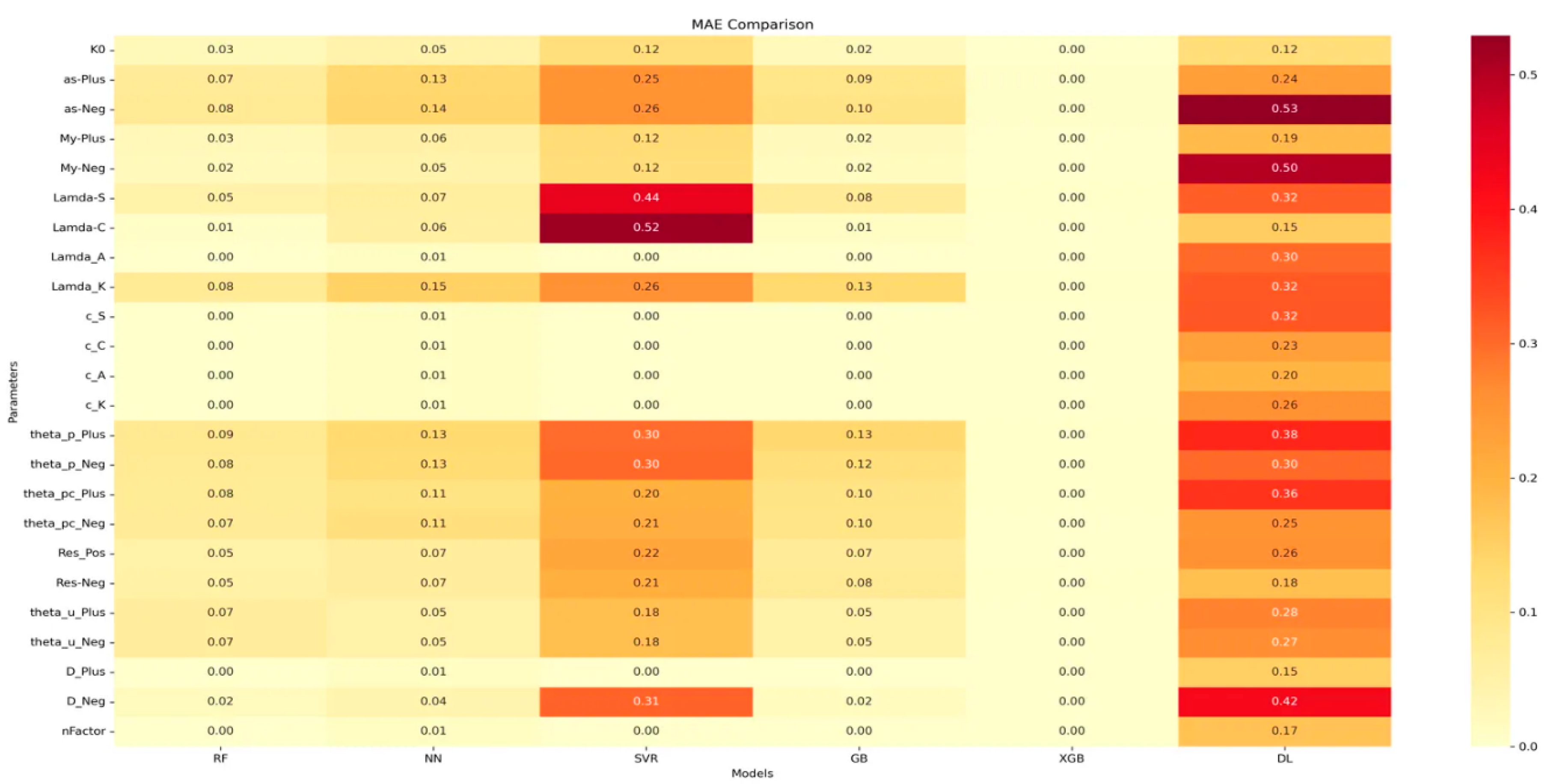

3.4.2. MAE (Mean Absolute Error) Analysis

- XGBoost consistently shows the lowest MAE across most parameters, indicating it has the best overall accuracy.

- SVR and DL models generally have higher MAE values, suggesting they may be less suitable for this specific prediction task.

- Parameters like Lamda-C and Lamda-S show higher MAE across all models, indicating these may be more challenging to predict accurately.

3.4.3. MAPE (Mean Absolute Percentage Error) Insights

- XGBoost again performs exceptionally well, with very low MAPE values for most parameters.

- There's significant variability in MAPE across different parameters, with some (e.g., theta_pc_Neg) showing very high errors across all models.

- The DL model shows inconsistent performance, excelling in some parameters but performing poorly in others.

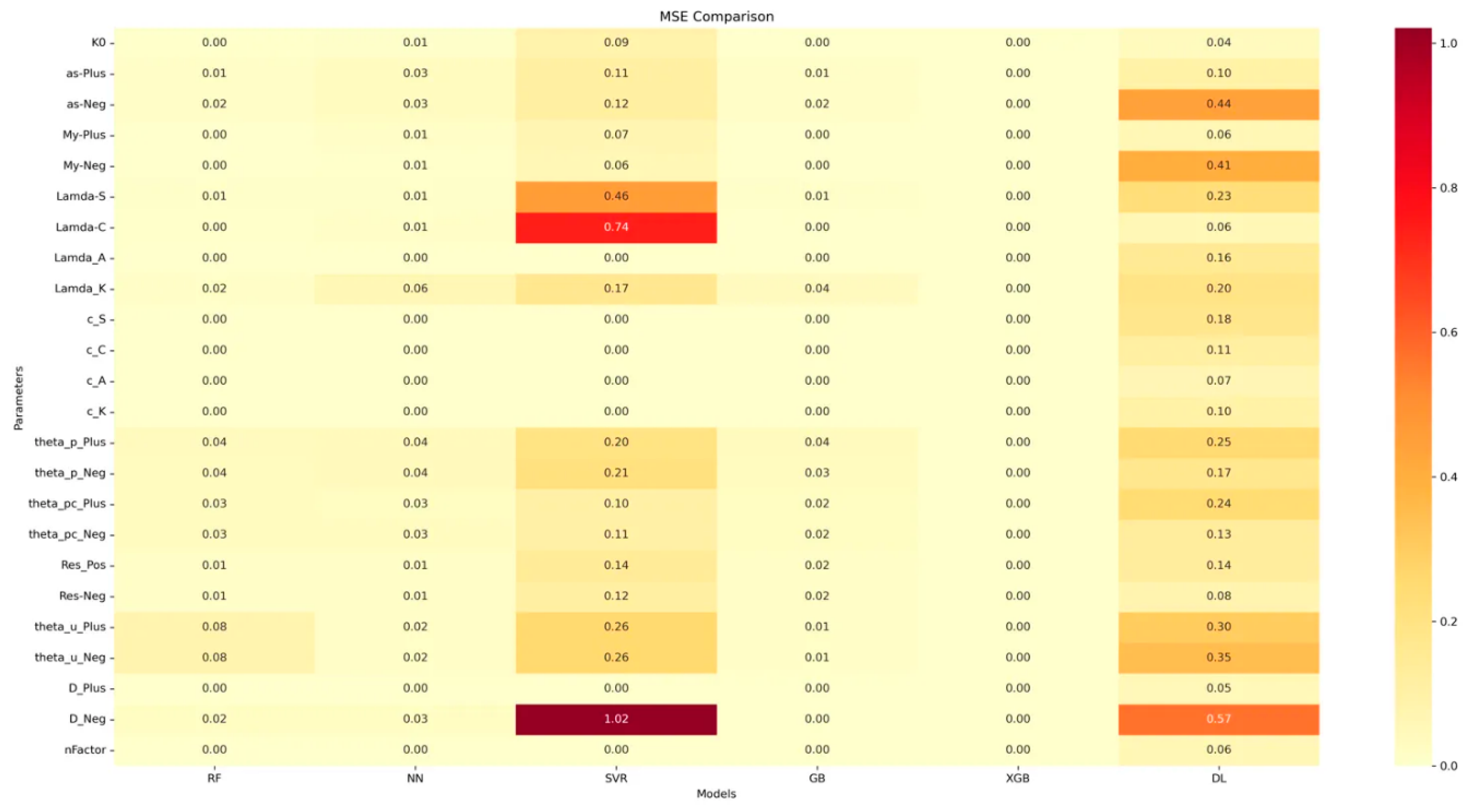

3.4.4. MSE (Mean Squared Error) Observations

- The MSE plot reinforces XGBoost's superior performance, showing consistently low errors.

- SVR shows notably high MSE for certain parameters (e.g., Lamda-C, D_Neg), indicating potential outlier sensitivity.

- RF and GB models show stable performance across parameters, suggesting good generalisation.

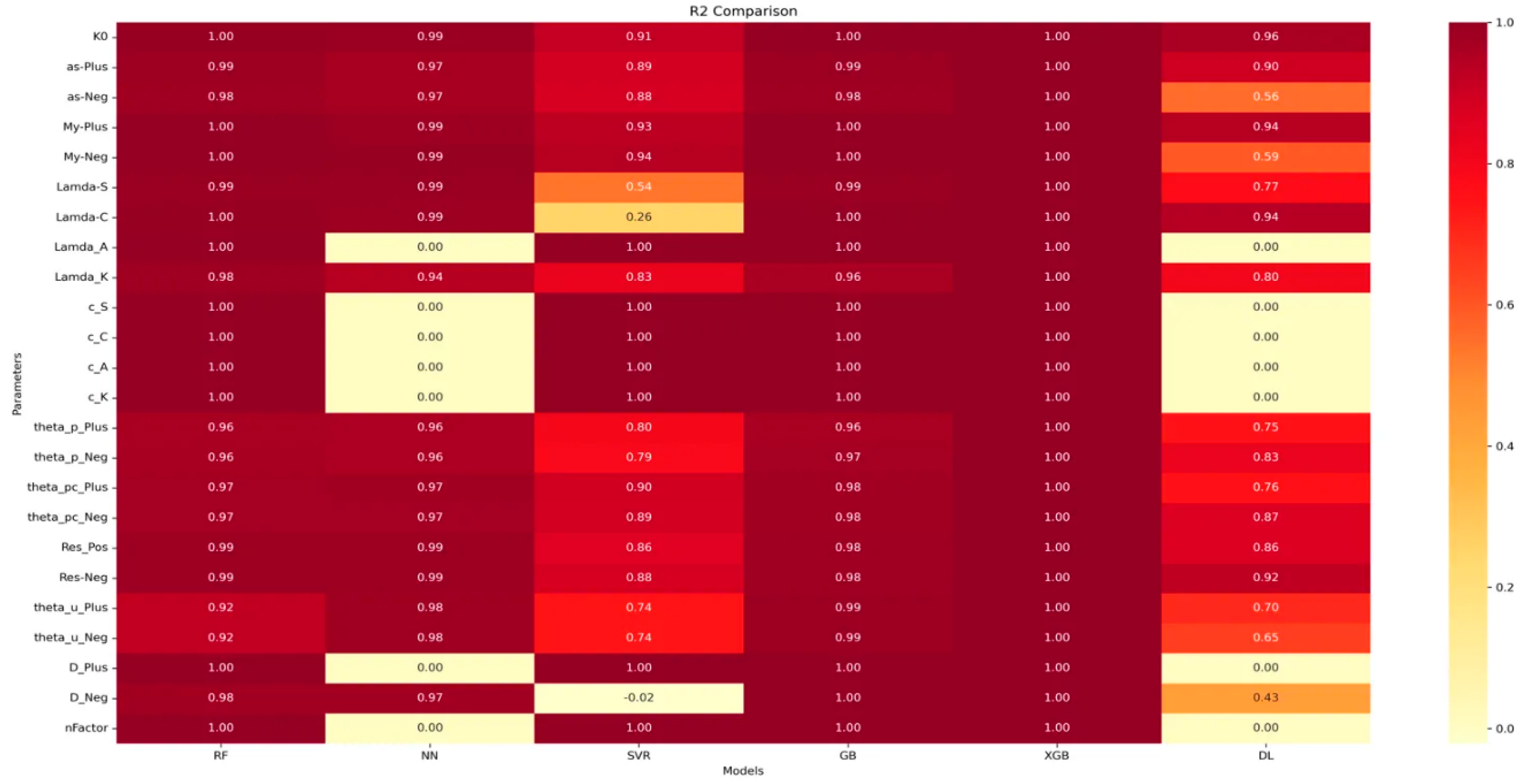

3.4.5. R2 Score Analysis

- Most models achieve high R2 scores (close to 1) for many parameters, indicating good fit overall.

- XGBoost consistently achieves R2 scores of 1 or very close to 1, suggesting excellent predictive power.

- Some parameters (e.g., Lamda-S, D_Neg) show lower R2 scores across models, hinting at inherent difficulty in their prediction.

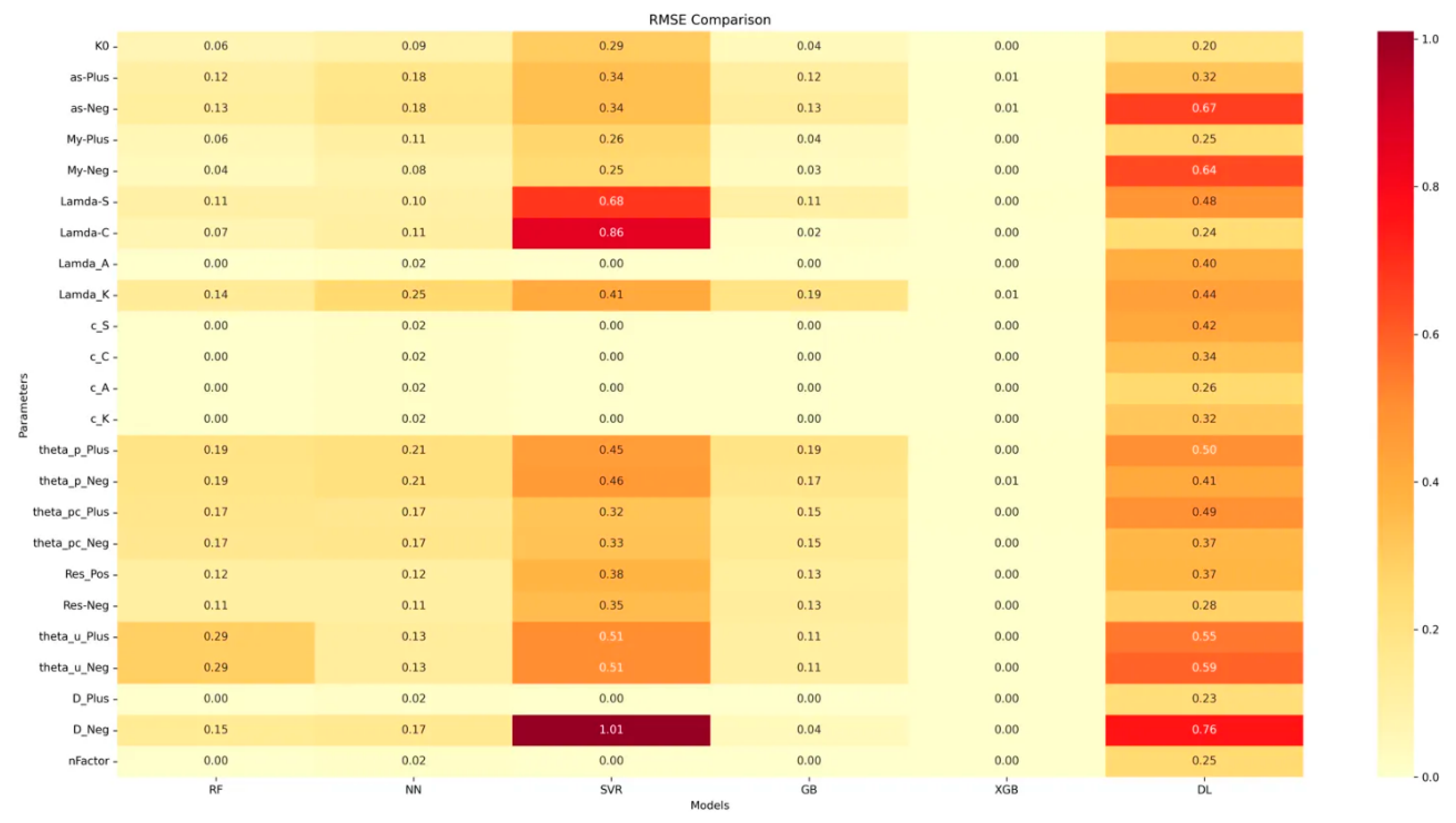

3.4.6. RMSE (Root Mean Square Error) Evaluation

- The RMSE plot largely mirrors the MSE plot but provides a more interpretable scale of error.

- XGBoost maintains its superior performance with consistently low RMSE values.

- Certain parameters (e.g., theta_u_Plus, theta_u_Neg) show higher RMSE across all models, suggesting these are more challenging to predict accurately.

3.4.7. Spearman Correlation Analysis

- XGBoost (XGB) consistently shows the highest Spearman correlation values across most parameters, often reaching perfect correlation (1.0). This indicates that XGBoost excellently captures the rank-order relationships between predicted and actual values.

- Random Forest (RF) follows closely, demonstrating very high correlations for most parameters.

- Traditional machine learning models (RF, NN, GB, XGB) generally outperform SVR and DL in terms of Spearman correlation.

- The Deep Learning (DL) model shows more variability in its performance across different parameters compared to other models.

- Most parameters show high correlations (>0.8) across all models, indicating generally good predictive performance.

- Lamda-C and Lamda-S show lower correlations, especially for SVR and DL models, suggesting these parameters are more challenging to predict accurately.

- The D_Neg parameter stands out with notably lower correlations across all models, indicating it might be the most difficult parameter to predict accurately.

3.5. Analysis Results

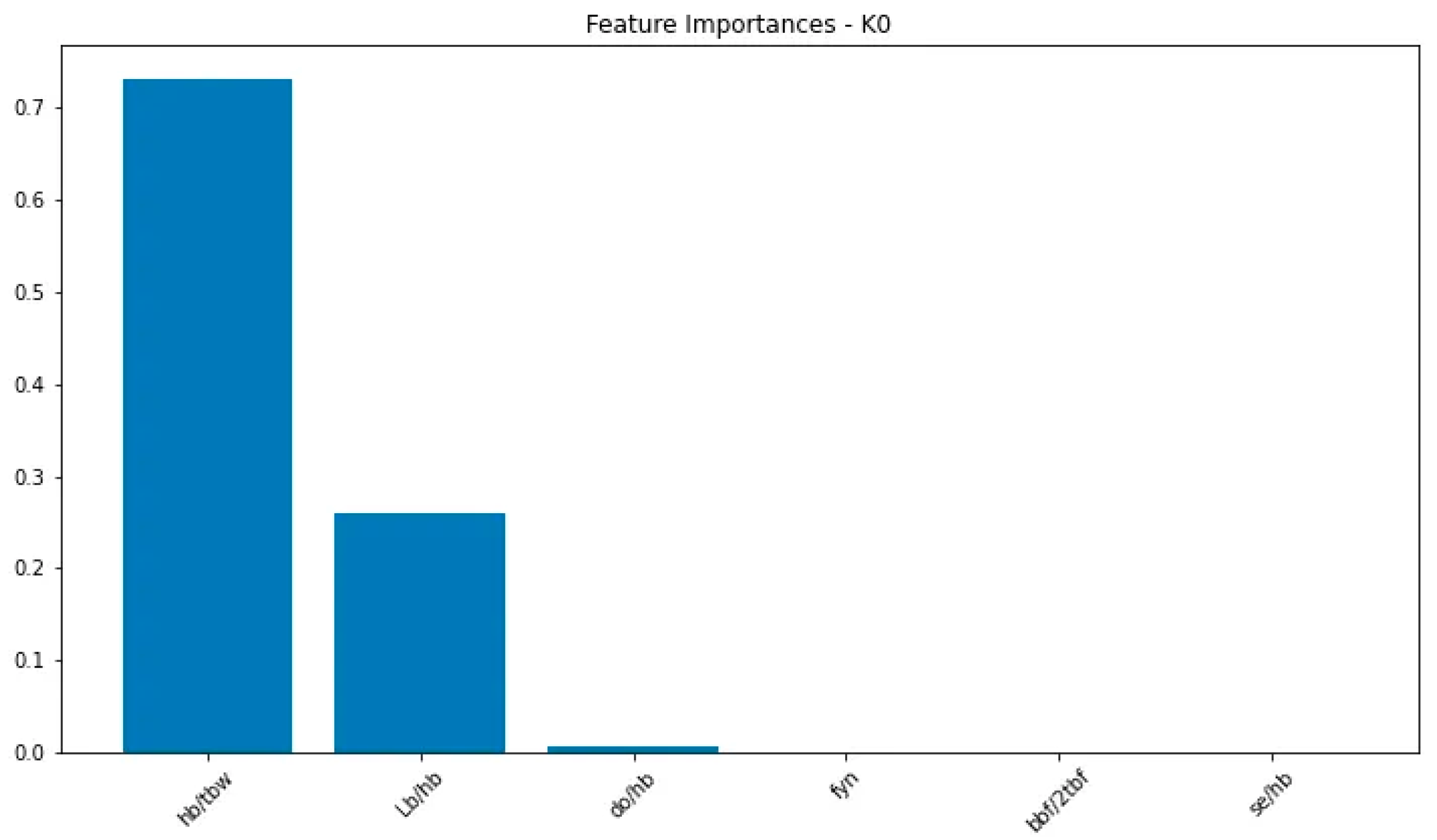

3.5.1. Feature Importance Graphs

- It helps identify which geometric or material properties have the most significant influence on each aspect of RWS connection behaviour.

- It provides insights into the underlying mechanics of RWS connections, potentially revealing relationships that are not immediately apparent from traditional analytical methods.

- It guides the focus of design considerations, highlighting which parameters engineers should prioritise when designing RWS connections for specific performance criteria.

- It can inform future research directions by identifying areas where the connection behaviour is particularly sensitive to certain properties.

3.5.2. Key Observations

- ○

- Different aspects of RWS connection behaviour are influenced by different geometric and material properties, highlighting the complex nature of these connections.

- ○

- Web slenderness and span-to-depth ratio consistently play significant roles across multiple parameters, emphasising their fundamental importance in RWS connection design.

- ○

- The opening-to-beam height ratio, which is unique to RWS connections, is crucial for many parameters, particularly those related to strength and stiffness degradation.

- ○

- The material yield strength, while not always the most important factor, plays a critical role in determining plastic rotation capacities, underlining the importance of material selection in achieving desired ductility.

4. Integration with Structural Analysis

4.1. Pushover Analysis

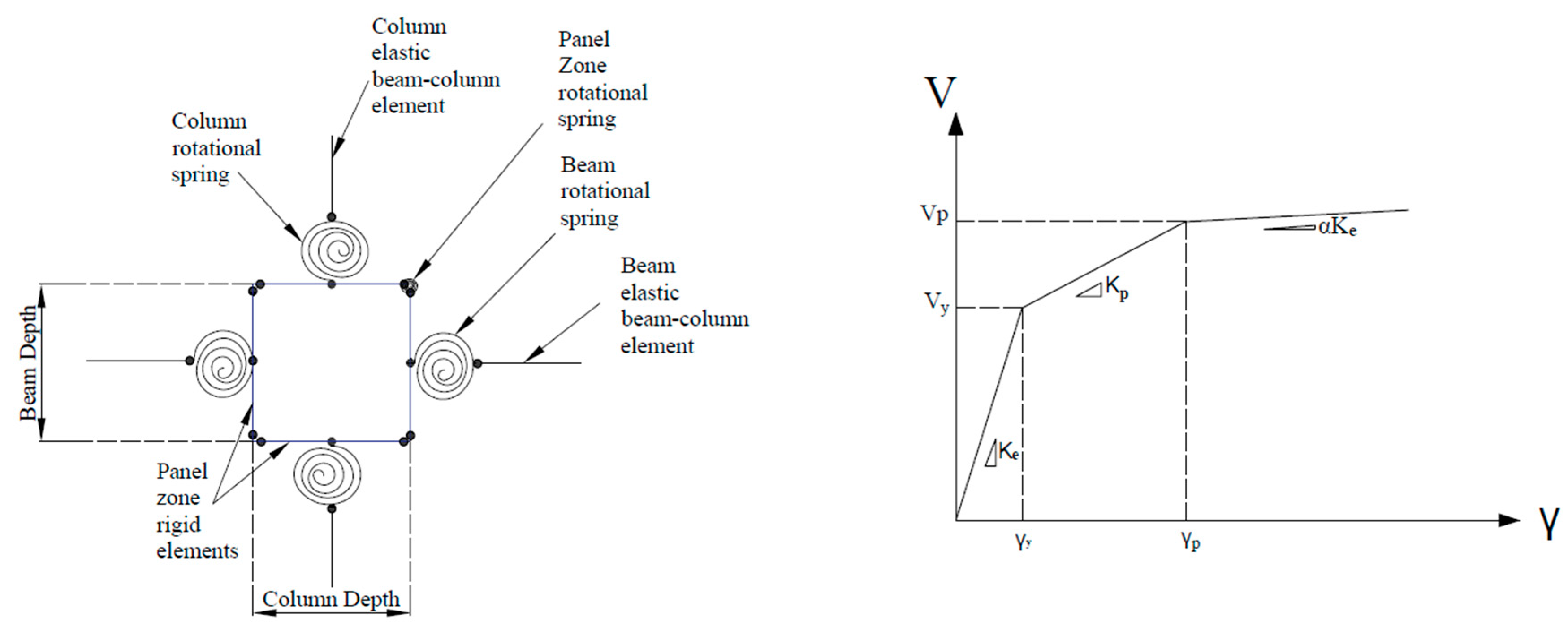

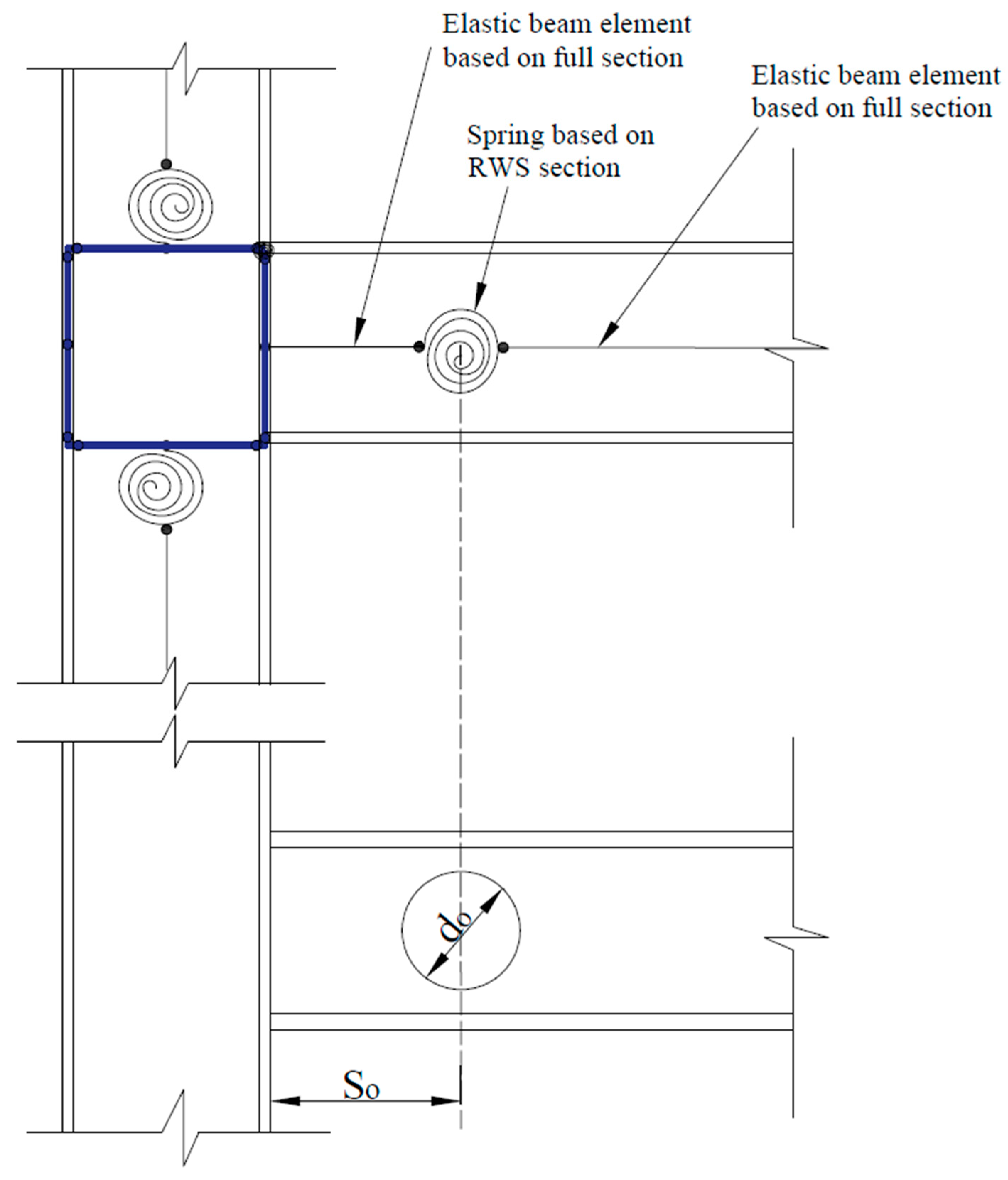

4.1.1. Panel Zone Modelling

- Elastic region: Defined by yield shear force (Vy), elastic shear stiffness (Ke), and yield rotation (γ_y)

- Post-yield region: Accounts for strength contribution from surrounding elements, characterised by post-yield stiffness (Kp)

- Post-capping region: Represents behaviour after reaching full plastic shear resistance (Vp) at a shear distortion angle (γ_p) equal to four times (γ_y), with a second post-yielding slope (Ksh)

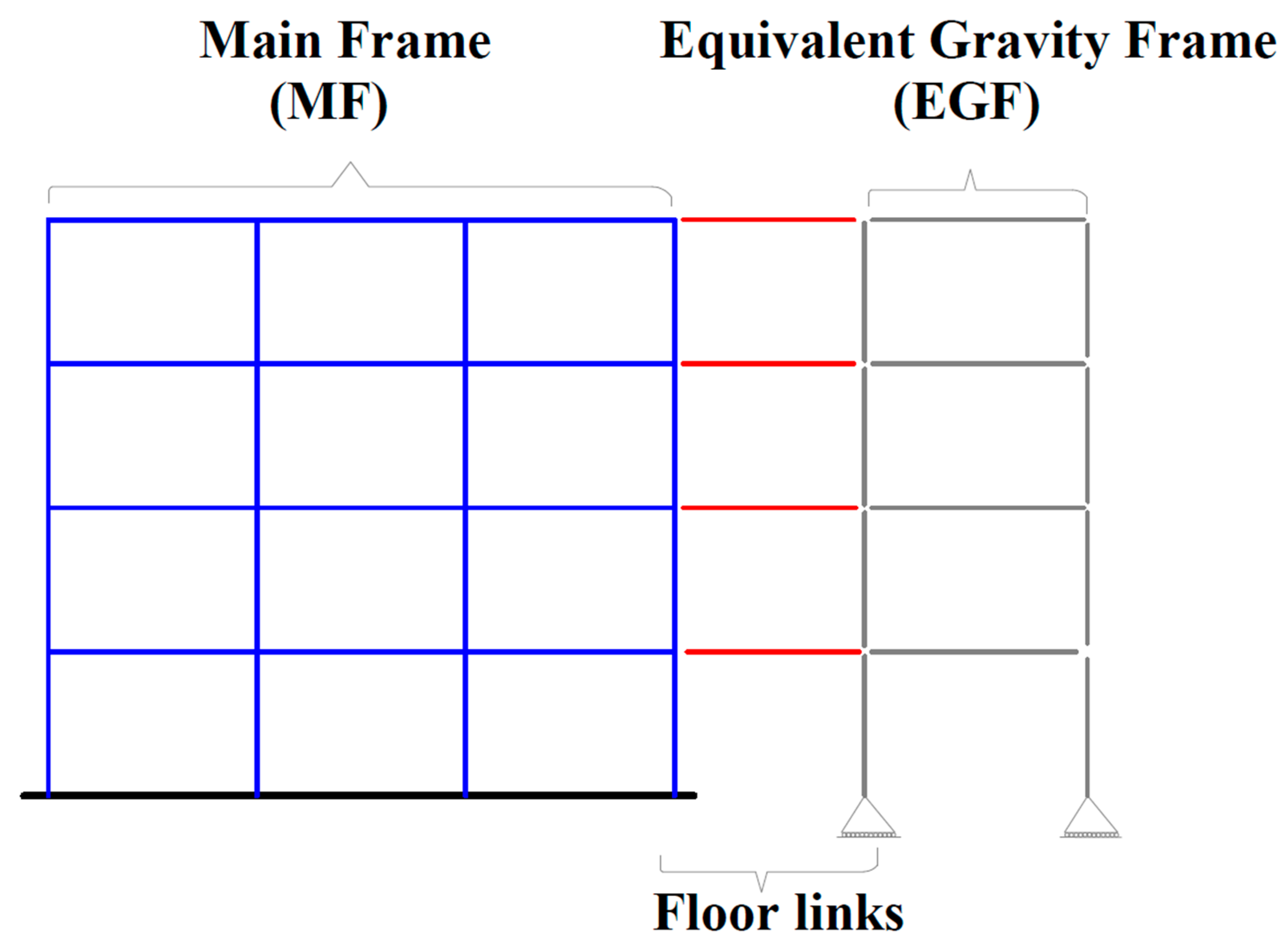

4.1.2. Equivalent Gravity Frame (EGF) Modelling

4.1.3. Integration of Modelling Techniques

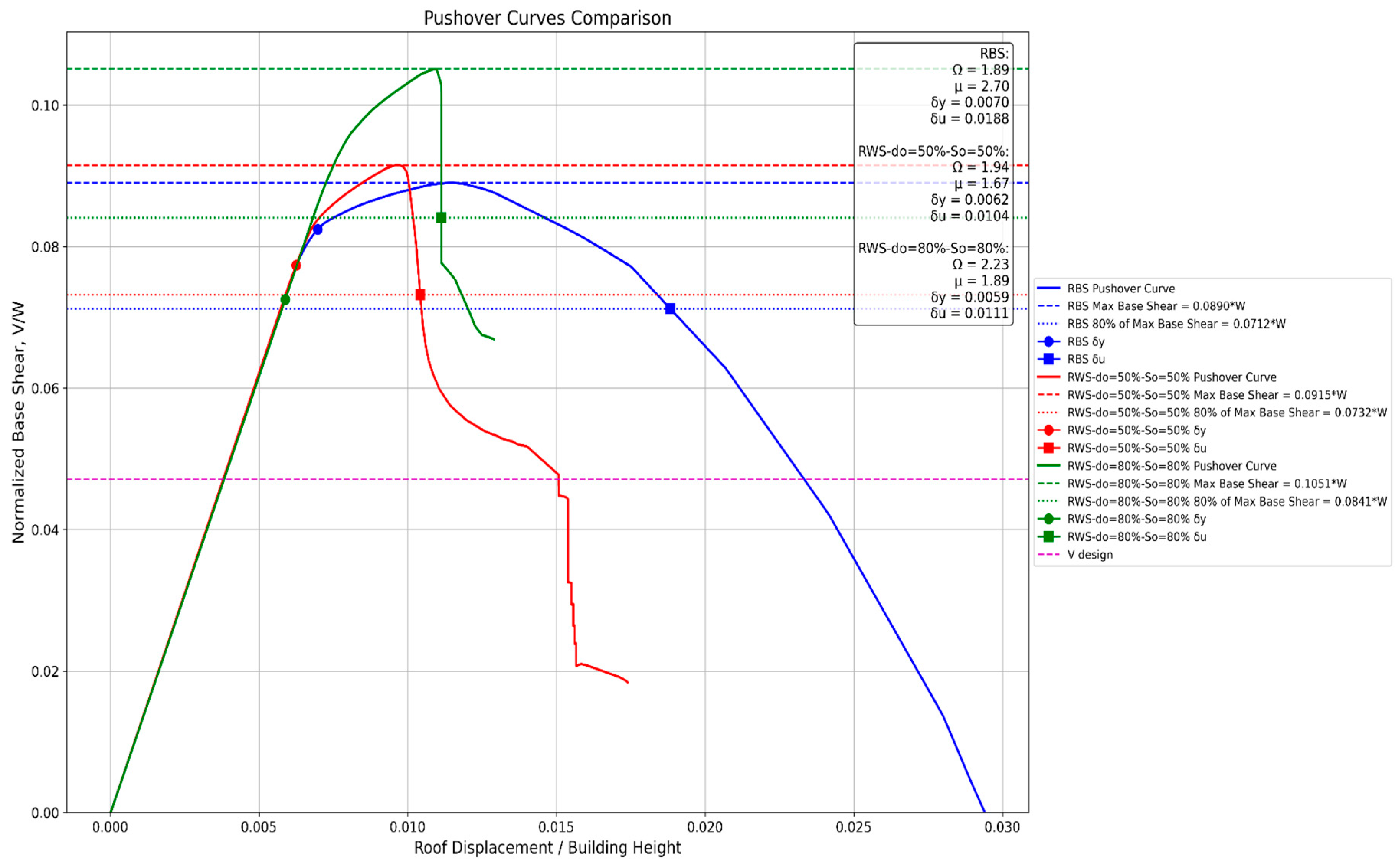

4.2. Pushover Analysis Results

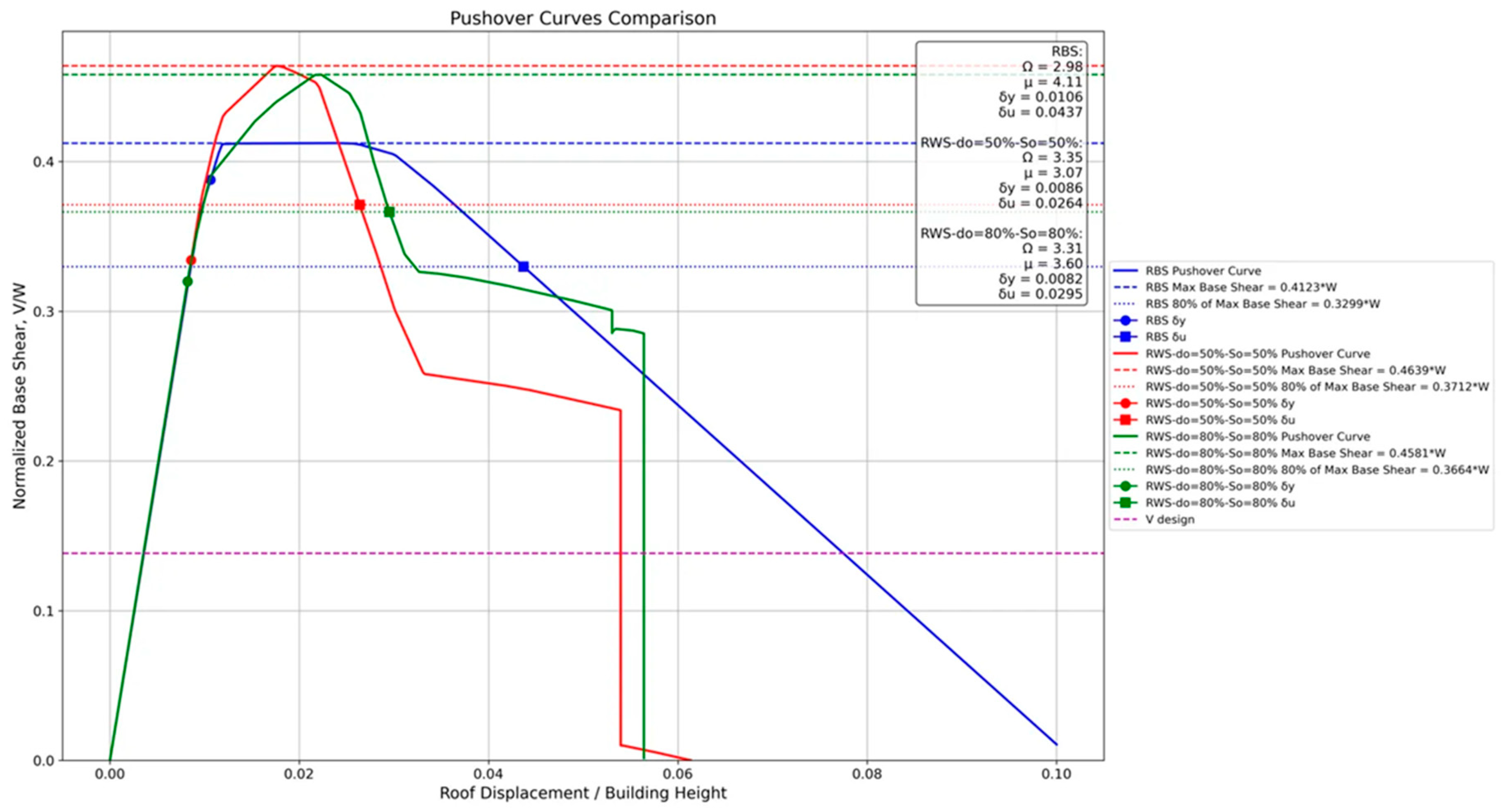

4.2.1. 2-Story Frame

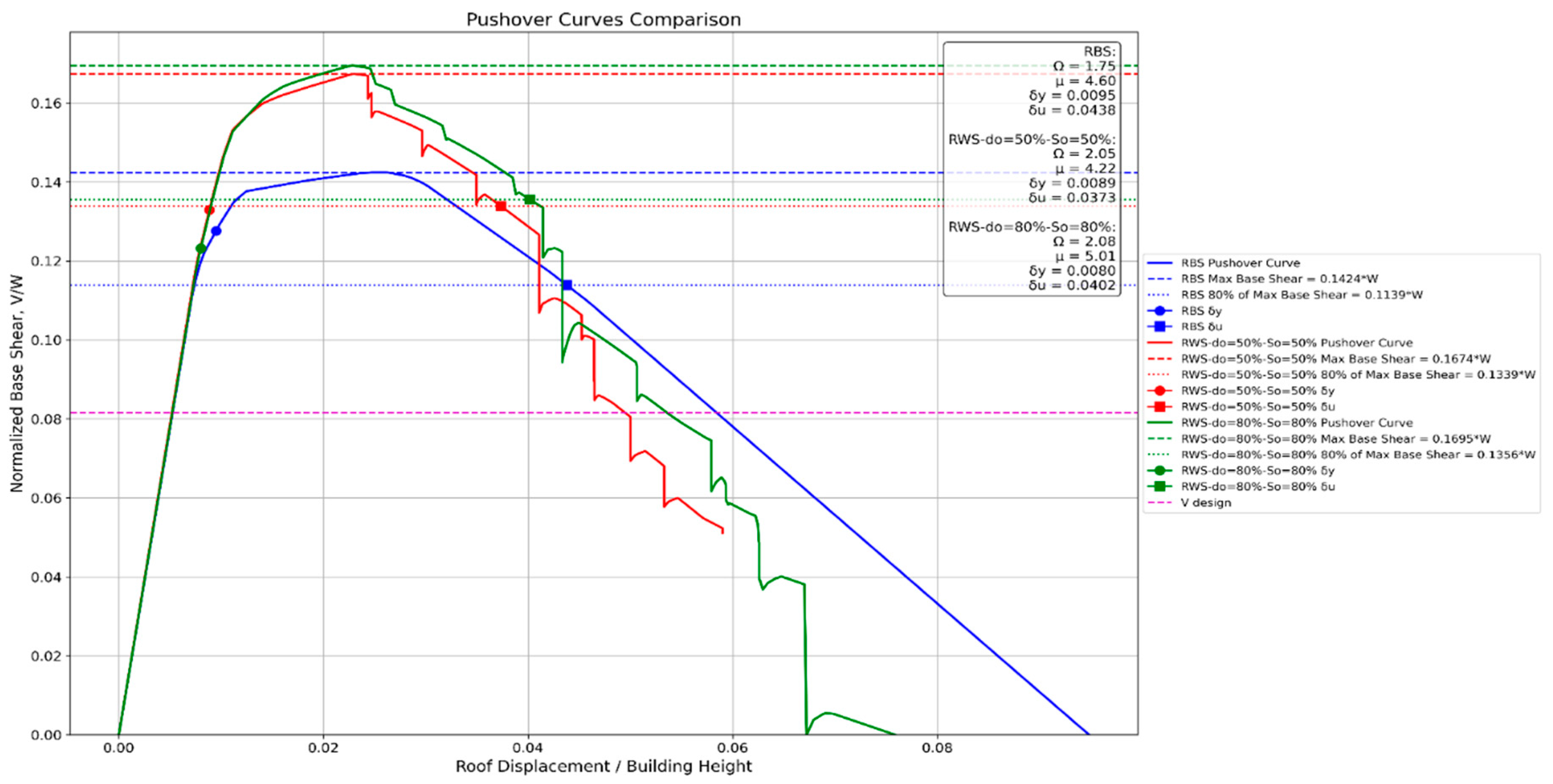

4.2.2. 4-Story Frame

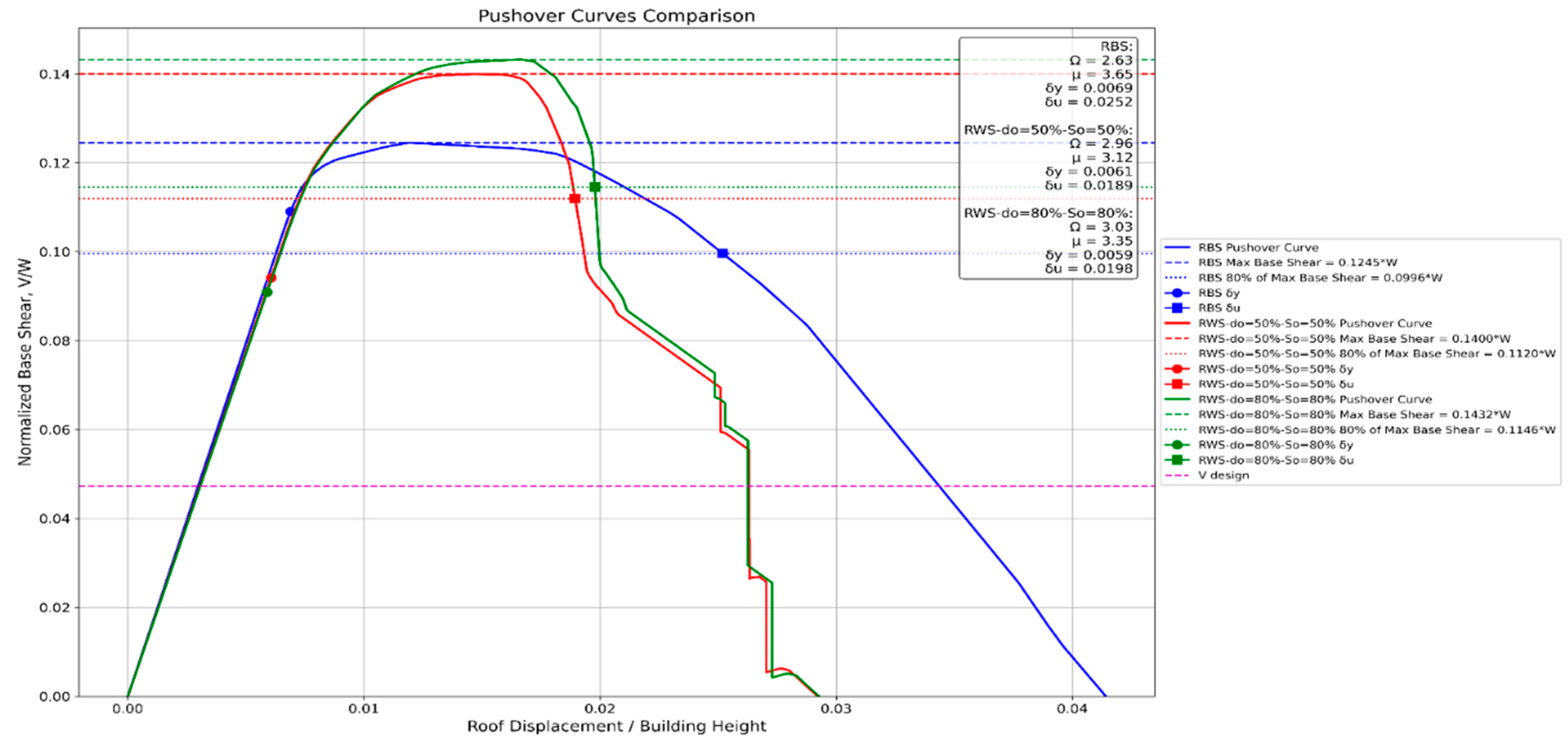

4.2.3. 8-Story Frame

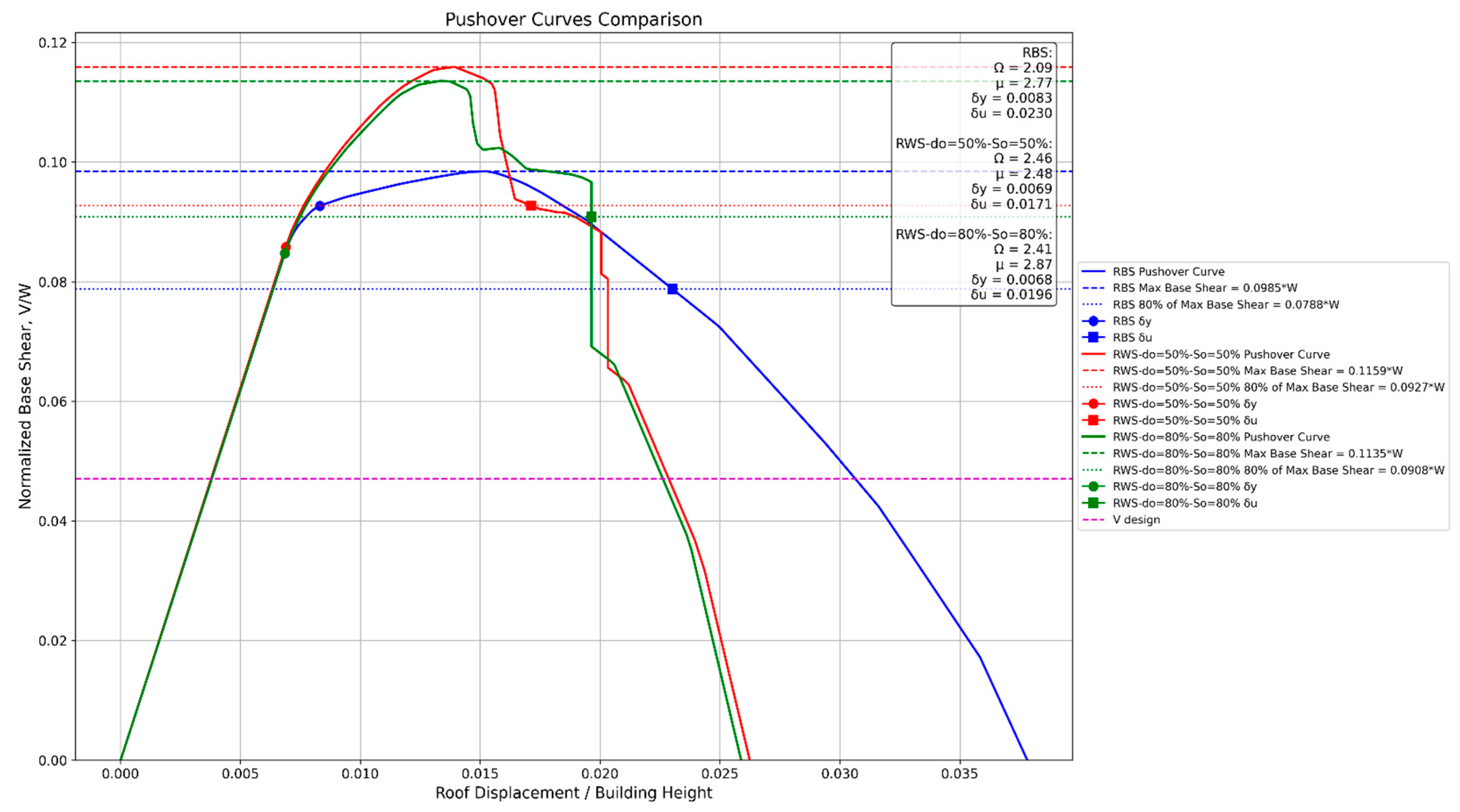

4.2.4. 12-Story Frame

4.2.5. 20-Story Frame

5. Conclusions

- RWS connections demonstrate viable and often superior performance compared to traditional RBS connections in steel moment frames, particularly in low to mid-rise structures.

- RWS connections consistently exhibit higher initial stiffness, peak strength, and overstrength factors compared to RBS connections across various frame heights (2 to 20 stories).

- The apparent earlier strength degradation in RWS connections is primarily due to the imposed ultimate rotation limit of 0.05 radians, which was set to control building damage. Despite this limitation, RWS connections still achieve interstory drifts larger than 4%, meeting performance targets set by ANSI/AISC and EC8 standards.

- ML and DL techniques, particularly XGBoost and Random Forest algorithms, demonstrate high accuracy in predicting Ibarra-Medina-Krawinkler (IMK) Bilin parameters for RWS connections, offering a powerful tool for efficient design and analysis.

- The study reveals complex interactions between web opening characteristics, beam length, and structural behaviour in RWS connections, providing valuable insights for optimising connection design.

- Feature importance analysis highlights that different aspects of RWS connection behaviour are influenced by various geometric and material properties, with web slenderness and span-to-depth ratio consistently playing significant roles across multiple parameters.

- The developed predictive models offer a rapid and accurate method for estimating IMK Bilin parameters across a wide range of RWS connection configurations, potentially streamlining the design process for structural engineers.

Acknowledgments

References

- F. M. Mazzolani, “Steel Structures in Seismic Zones,” in Seismic Resistant Steel Structures, F. M. Mazzolani and V. Gioncu, Eds., Vienna: Springer Vienna, 2000, pp. 1–17.

- A. Astaneh-Asl, “Post-earthquake stability of steel moment frames with damaged connections,” Connections in Steel Structures III, pp. 391–402, Jan. 1996. [CrossRef]

- J. O. Malley, “Performance of moment resisting steel frames in the january 17, 1994 northridge earthquake,” Connections in Steel Structures III, pp. 553–561, Jan. 1996. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Sofias and D. T. Pachoumis, “Assessment of reduced beam section (RBS) moment connections subjected to cyclic loading,” J Constr Steel Res, vol. 171, p. 106151, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Horton, I. Hajirasouliha, B. Davison, Z. Ozdemir, and I. Abuzayed, “Development of more accurate cyclic hysteretic models to represent RBS connections,” Eng Struct, vol. 245, p. 112899, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. T. Naughton, K. D. Tsavdaridis, C. Maraveas, and A. Nicolaou, “Pushover analysis of steel seismic resistant frames with reduced web section and reduced beam section connections,” Front Built Environ, vol. 3, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. D. Tsavdaridis and T. Papadopoulos, “A FE parametric study of RWS beam-to-column bolted connections with cellular beams,” J Constr Steel Res, vol. 116, pp. 92–113, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Elkady and D. G. Lignos, “Modeling of the composite action in fully restrained beam-to-column connections: Implications in the seismic design and collapse capacity of steel special moment frames,” Earthq Eng Struct Dyn, vol. 43, no. 13, pp. 1935–1954, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- D. Lignos and H. Krawinkler, “SIDESWAY COLLAPSE OF DETERIORATING STRUCTURAL SYSTEMS UNDER SEISMIC EXCITATIONS,” 2012. [Online]. Available: http://blume.stanford.edu.

- F. F. Almutairi, K. D. Tsavdaridis, A. Alonso-Rodriguez, and I. Hajirasouliha, “Experimental investigation using demountable steel-concrete composite reduced web section (RWS) connections under cyclic loads,” Bulletin of Earthquake Engineering, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- “EN 1998-1: Eurocode 8: Design of structures for earthquake resistance – Part 1: General rules, seismic actions and rules for buildings,” 2004.

- “Prequalified Connections for Special and Intermediate Steel Moment Frames for Seismic Applications,” 2016. [Online]. Available: www.aisc.org.

- F. F. Almutairi and K. D. Tsavdaridis, “Capacity design assessment of composite reduced web section (RWS) connections,” Eng Struct, vol. 316, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Gupta and H. Krawinkler, “SEISMIC DEMANDS FOR PERFORMANCE EVALUATION OF STEEL MOMENT RESISTING FRAME STRUCTURES,” 1999. [Online]. Available: http://blume.stanford.edu.

- L. F. Ibarra and H. Krawinkler, “GLOBAL COLLAPSE OF FRAME STRUCTURES UNDER SEISMIC EXCITATIONS,” 2005. [Online]. Available: http://blume.stanford.edu.

- K. D. Tsavdaridis, F. Faghih, and N. Nikitas, “Assessment of perforated steel beam-to-column connections subjected to cyclic loading,” Journal of Earthquake Engineering, vol. 18, no. 8, pp. 1302–1325, 2014. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, S. Zheng, and X. Zhao, “Seismic performance of steel beam-to-column moment connections with different structural forms,” J Constr Steel Res, vol. 158, pp. 130–142, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Boushehri, K. D. Tsavdaridis, and G. Cai, “Seismic behaviour of RWS moment connections to deep columns with European sections,” J Constr Steel Res, vol. 161, pp. 416–435, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Nazaralizadeh, H. Ronagh, P. Memarzadeh, and F. Behnamfar, “Cyclic performance of bolted end-plate RWS connection with vertical-slits,” J Constr Steel Res, vol. 173, p. 106236, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Q. Xu, H. Chen, W. Li, S. Zheng, and X. Zhang, “Experimental investigation on seismic behavior of steel welded connections considering the influence of structural forms,” Eng Fail Anal, vol. 139, p. 106499, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. By, : Thomas, and A. Horton, “Predicting Reduced Beam Section (RBS) Connection Performance in Steel Moment Frames”.

- Fema, “FEMA 350 - Recommended Seismic Design Criteria for New Steel Moment-Frame Buildings.” [Online]. Available: www.seaoc.org.

- C. G. Deng, O. S. Bursi, and R. Zandonini, “A hysteretic connection element and its applications,” Comput Struct, vol. 78, no. 1–3, pp. 93–110, Nov. 2000. [CrossRef]

- D. Patsialis, A. P. Kyprioti, and A. A. Taflanidis, “Bayesian calibration of hysteretic reduced order structural models for earthquake engineering applications,” Eng Struct, vol. 224, p. 111204, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Elkady and D. G. Lignos, “Effect of gravity framing on the overstrength and collapse capacity of steel frame buildings with perimeter special moment frames,” Earthq Eng Struct Dyn, vol. 44, no. 8, pp. 1289–1307, Jul. 2015. [CrossRef]

- “Seismic Provisions for Structural Steel Buildings Supersedes the Seismic Provisions for Structural Steel Buildings,” 2016. [Online]. Available: www.aisc.org.

- S. M. A, T. K. Daniel, and Y. Satoshi, “Comprehensive FE Study of the Hysteretic Behavior of Steel–Concrete Composite and Noncomposite RWS Beam-to-Column Connections,” Journal of Structural Engineering, vol. 144, no. 9, p. 04018150, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Fares, P. Eng, J. Coulson, and D. W. Dinehart, “Castellated and Cellular Beam Design 31 Steel Design Guide,” 2016.

- D. Darwin, “Steel Design Guide Series Steel and Composite Beams with Web Openings Design of Steel and Composite Beams with Web Openings,” 2003.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).