Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

19 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The FFS Approach and Methodology

2.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

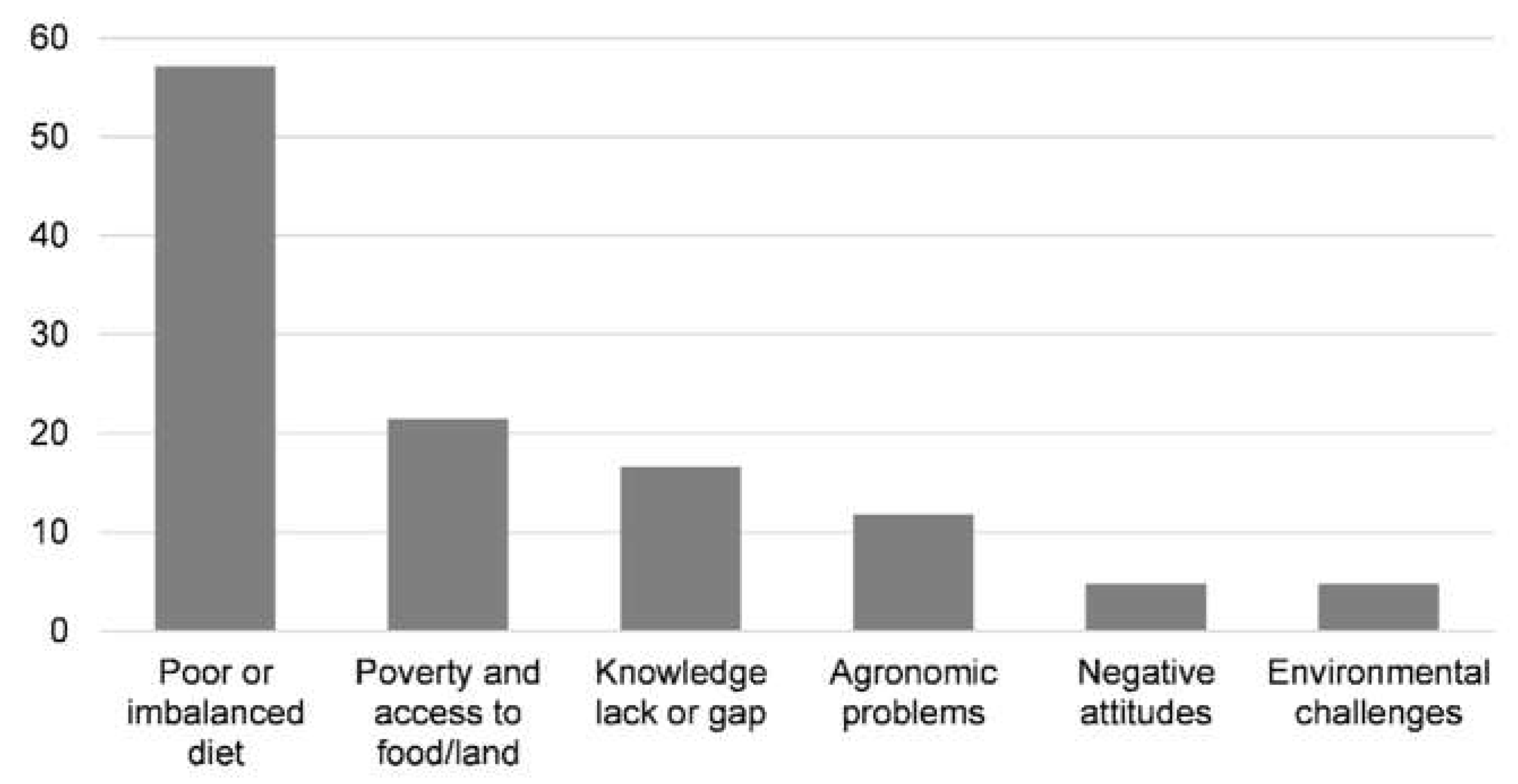

3.1. Malnutrition Problem Tree

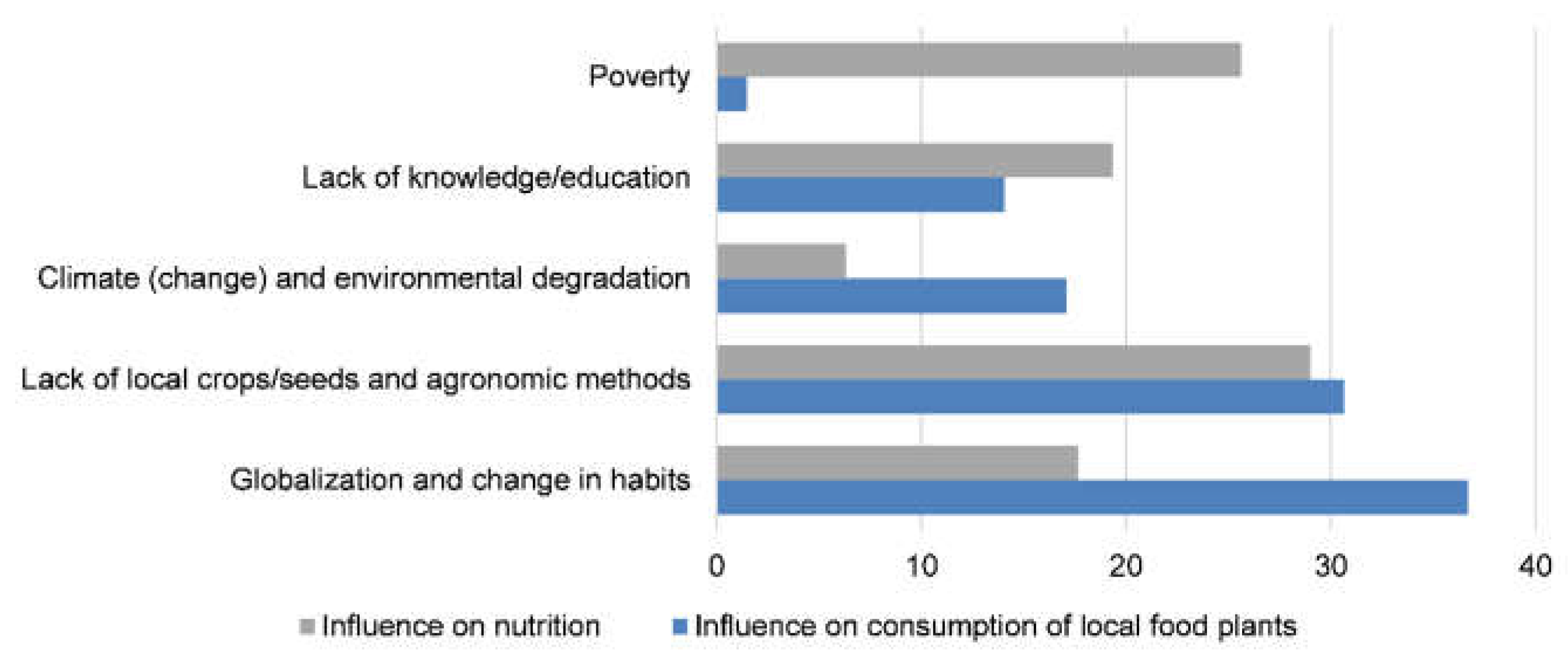

3.2. Changes in Local Food Plant Consumption and Community Nutrition Status over Time

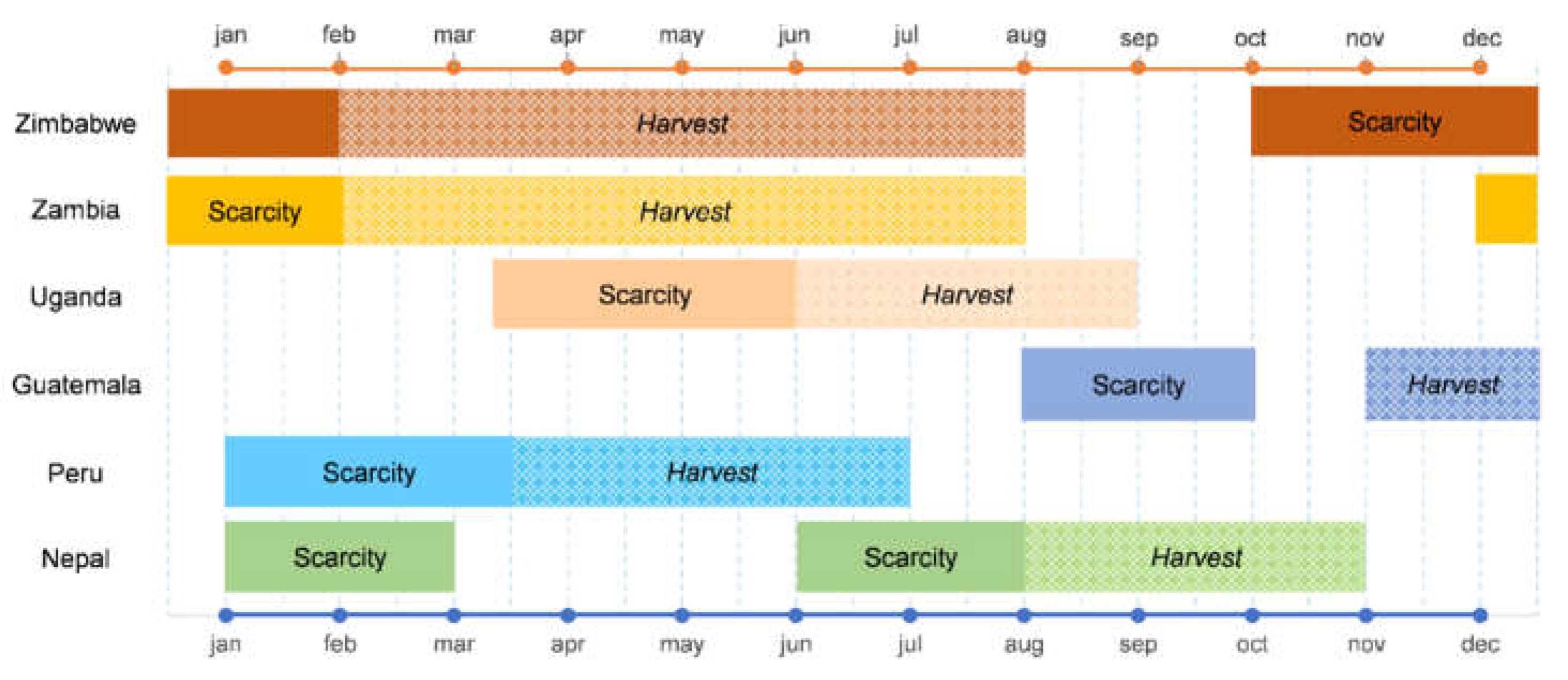

3.3. The Role of Local Food Plants During Food Scarcity Periods

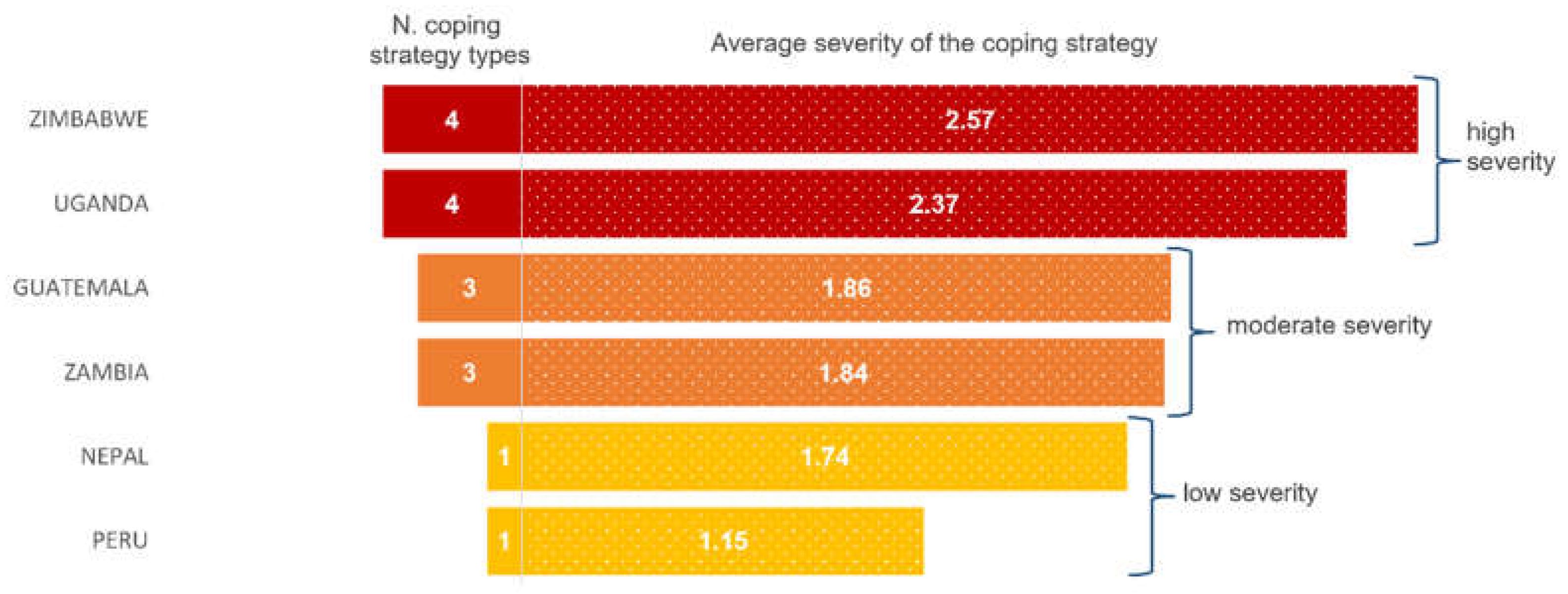

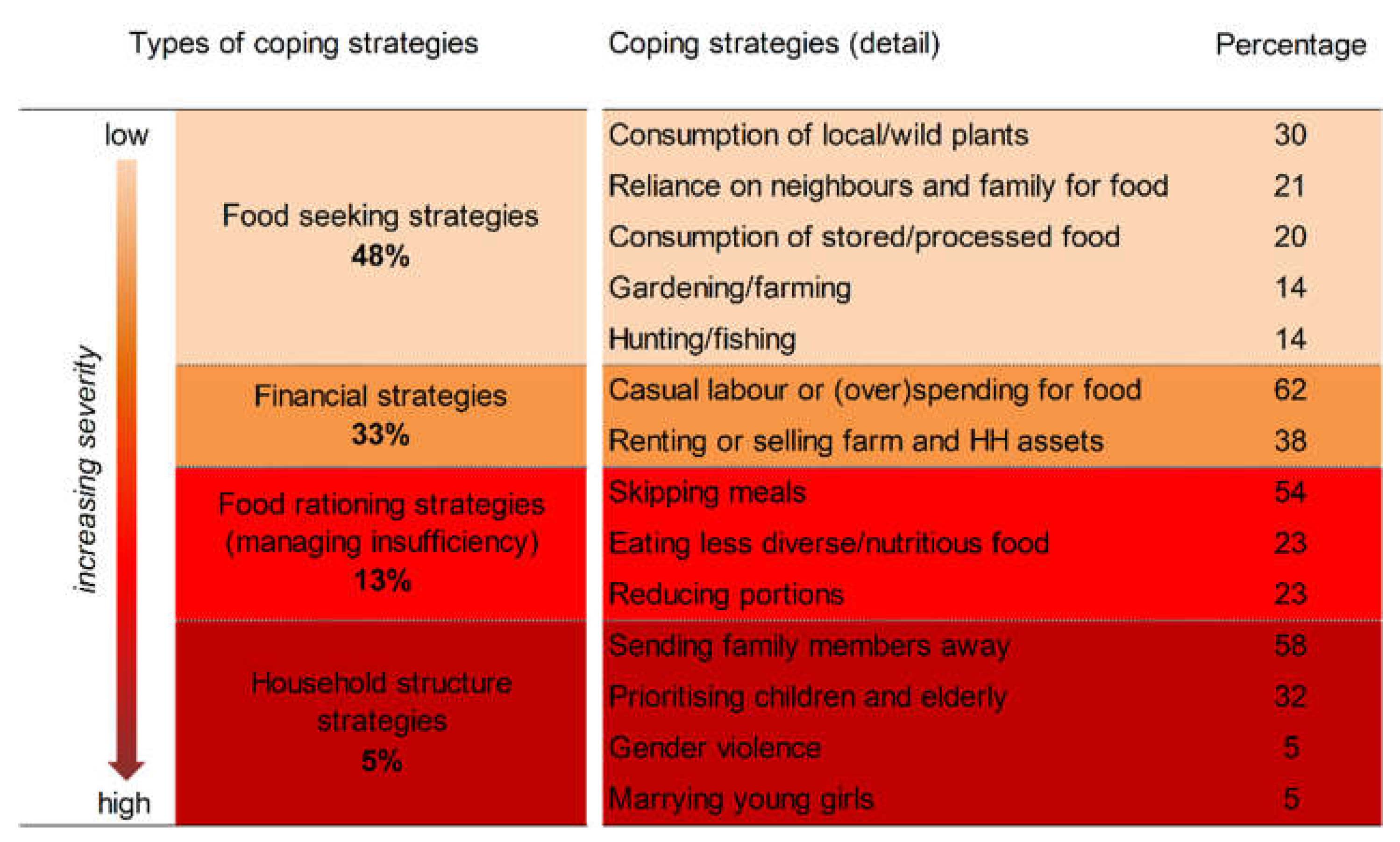

3.4. Food Scarcity Coping Strategies

3.5. Priority Activities for Leveraging the Role of Local Food Plants

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FFS | Farmer Field Schools |

| NUS | Neglected and Underutilized Species |

| 1 | 1 We have adopted the term local food plants as an alternative to the term Neglected and Underutilised Species (NUS), as a term better understood by local communities who participated in the FFS object of this study. Local food plants can be described as all species that occur in local ecosystems, wild and cultivated, that provide or may provide food items in such communities and complement major and often global staple crops in the local diet. Many NUS may and often do function as local food plants. |

| 2 | 2 For the purpose of this report food scarcity is defined as a situation in which locally available food from any source is insufficient to meet the food and nutrition intake needs of a specific community, both in quantitative terms (calories) as in qualitative terms (dietary diversity, nutritional quality). |

References

- Micha, R.; Mannar, V.; Afshin, A.; Allemandi, L.; Baker, P.; Battersby, J.; Dolan, C. Global Nutrition Report: Action on Equity to End Malnutrition; Bristol, UK, 2020.

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; et al. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT-Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi, S.L.; Lammerts van Bueren, E.T.; Ceccarelli, S.; Grando, S.; Upadhyaya, H.D.; Ortiz, R. Diversifying Food Systems in the Pursuit of Sustainable Food Production and Healthy Diets. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 842–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachat, C.; Raneri, J.E.; Smith, K.W.; Kolsteren, P.; Van Damme, P.; Verzelen, K.; Penafiel, D.; Vanhove, W.; Kennedy, G.; Hunter, D.; et al. Dietary Species Richness as a Measure of Food Biodiversity and Nutritional Quality of Diets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Diet, Nutrition, and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases : Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation; World Health Organization, 2003; ISBN 924120916X.

- WHO The Double Burden of Malnutrition; Geneva, 2017.

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World. Safeguarding against Economic Slowdowns and Downturns; Rome, Italy, 2019.

- Kuhnlein, H.V.; Erasmus, B.; Spigelski, D. Indigenous Peoples’ Food Systems:The Many Dimensions of Culture, Diversity and Environment for Nutrition and Health; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Roche, M.L.; Creed-Kanashiro, H.M.; Tuesta, I.; Kuhnlein, H.V. Traditional Food System Provides Dietary Quality for the Awajún in the Peruvian Amazon. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2007, 46, 377–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.K.; Sreenivasulu, N.; Prasad, M. Potential of Underutilized Crops to Introduce the Nutritional Diversity and Achieve Zero Hunger. Funct. Integr. Genomics 2022, 1459–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padulosi, S.; Heywood, V.; Hunter, D.; Jarvis, A. Underutilized Species and Climate Change: Current Status and Outlook. In Crop Adaptation to Climate Change; 2011; pp. 507–521 ISBN 9780470960929.

- Cámara-Leret, R.; Raes, N.; Roehrdanz, P.; De Fretes, Y.; Heatubun, C.D.; Roeble, L.; Schuiteman, A.; van Welzen, P.C.; Hannah, L. Climate Change Threatens New Guinea’s Biocultural Heritage. Sci. Adv. 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, J.; Pilling, D. The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture.; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 2019; ISBN 9251312702.

- Sõukand, R. Perceived Reasons for Changes in the Use of Wild Food Plants in Saaremaa, Estonia. Appetite 2016, 107, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quave, C.L.; Pieroni, A. Fermented Foods for Food Security and Food Sovereignty in the Balkans: A Case Study of the Gorani People of Northeastern Albania. J. Ethnobiol. 2014, 34, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Garcia, G.S.; Price, L.L. Gathering of Wild Food Plants in Anthropogenic Environments across the Seasons: Implications for Poor and Vulnerable Farm Households. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2014, 53, 363–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocho, D.L.; Struik, P.C.; Price, L.L.; Kelbessa, E.; Kolo, K. Assessing the Levels of Food Shortage Using the Traffic Light Metaphor by Analyzing the Gathering and Consumption of Wild Food Plants, Crop Parts and Crop Residues in Konso, Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz García, G.S. The Mother – Child Nexus. Knowledge and Valuation of Wild Food Plants in Wayanad, Western Ghats, India. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2006, 2, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaza, M. Modernization and Gender Dynamics in the Loss of Agrobiodiversity in Swaziland’s Food System. In Women and plants. Gender relations in biodiversity management and conservation; 2003; pp. 243–257.

- Somnasang, P.; Moreno-Black, G. Knowing, Gathering and Eating: Knowledge and Attitudes about Wild Food in an Isan Village in Northeastern Thailand. J. Ethnobiol. 2000, 20, 197–216. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Garcia, G.S.; Price, L.L. Ethnobotanical Investigation of “wild” Food Plants Used by Rice Farmers in Kalasin, Northeast Thailand. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2011, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyakoojo, C.; Tugume, P. Traditional Use of Wild Edible Plants in the Communities Adjacent Mabira Central Forest Reserve, Uganda. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2020, 20, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Penafiel, D.; Vanhove, W.; Espinel, R.L.; Van Damme, P. Food Biodiversity Includes Both Locally Cultivated and Wild Food Species in Guasaganda, Central Ecuador. J. Ethn. Foods 2019, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Schunko, C.; Li, X.; Klappoth, B.; Lesi, F.; Porcher, V.; Porcuna-Ferrer, A.; Reyes-García, V. Local Communities’ Perceptions of Wild Edible Plant and Mushroom Change: A Systematic Review. Glob. Food Sec. 2022, 32, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, C.K.; Bjorkman, A.D.; Dempewolf, H.; Ramirez-Villegas, J.; Guarino, L.; Jarvis, A.; Rieseberg, L.H.; Struik, P.C. Increasing Homogeneity in Global Food Supplies and the Implications for Food Security. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2014, 111, 4001–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.; Bhatta, S.; Aryal, K.; Joshi, B.K.; Gauchan, D. Threats, Drivers, and Conservation Imperative of Agrobiodiversity. J. Agric. Environ. 2020, 21, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orphan Crops for Sustainable Food and Nutrition Security: Promoting Neglected and Underutilized Species; Padulosi, S., Oliver King, I.E.D., Hunter, D., Swaminathan, M.S., Eds.; 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021.

- Oxfam Novib Starting with Farmer Field Schools; 2021.

- Oxfam Novib Facilitators’ Field Guide for Farmer Field Schools on Local Food Plants for Nutrition. Module: Diagnostic Phase. 2022, 34. Oxfam Novib Facilitators’ Field Guide for Farmer Field Schools on Local Food Plants for Nutrition. Module: Diagnostic Phase. 2022, 34.

- Beck, H.E.; Zimmermann, N.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Wood, E.F. Present and Future Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Maps at 1-Km Resolution. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dil Farzana, F.; Rahman, A.S.; Sultana, S.; Raihan, M.J.; Haque, M.A.; Waid, J.L.; Choudhury, N.; Ahmed, T. Coping Strategies Related to Food Insecurity at the Household Level in Bangladesh. PLoS One 2017, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, R.; Schönfeldt, H.C.; Owen, J.H. Food-Coping Strategy Index Applied to a Community of Farm-Worker Households in South Africa. Food Nutr. Bull. 2008, 29, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Development Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria 2011.

- FAO Natural Regions in Zimbabwe. Fertilizer use by crop in Zimbabwe; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Veldcamp, W.J.; Muchinda, M.; Delmotte, A.P. Agro-Climate Zones in Zambia. Soil Bull. No. 9 1984.

- International Red Cross Federation Seasonal and Critical Events Calendar - Eastern Africa Region. Available online: https://ifrcgo.org/africa/img-foodsecurity/171130_Eastern_Africa_Region_Critical _Events_and_Outlook_Calendar.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- de la Cruz, J.R. Clasificación de Zonas de Vida de Guatemala a Nivel de Reconocimiento. Sistema Holdridge.; Instituto Nacional Forestal: Ciudad de Guatemala, Guatemala, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- FEWS NET Guatemala Food Security Outlook, October 2021–May 2022: Seasonal Income Gains Fail to Fully Alleviate Food Insecurity. Available online: https://fews.net/central-america-and-caribbean/guatemala/food-security-outlook/october-2021 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Pulgar Vidal, J. Geografía Del Perú; 9th editio.; PEISA: Lima, Peru, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- de Haan, S.; Burgos, G.; Liria, R.; Rodriguez, F.; Creed-Kanashiro, H.M.; Bonierbale, M. The Nutritional Contribution of Potato Varietal Diversity in Andean Food Systems: A Case Study. Am. J. Potato Res. 2019, 96, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paudel, B.; Panday, D.; Dhakal, K. Climate. In The Soils of Nepal; Ojha, R.B., Panday, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-80999-7. [Google Scholar]

- Rohwerder, B. Seasonal Vulnerability and Risk Calendar in Nepal (GSDRC Helpdesk Research Report 1358); Birmingham, UK, 2016.

- Arimond, M.; Ruel, M.T. Dietary Diversity Is Associated with Child Nutritional Status: Evidence from 11 Demographic and Health Surveys. J. Nutr. 2004, 134, 2579–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, K.G.; Adu-Afarwuah, S. Systematic Review of the Efficacy and Effectiveness of Complementary Feeding Interventions in Developing Countries. Matern. Child Nutr. 2008, 4, 24–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, D.K.; Allen, L.H. The Importance of Milk and Other Animal-Source Foods for Children in Low-Income Countries. Food Nutr. Bull. 2011, 32, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquis, G.S.; Habicht, J.-P.; Lanata, C.F.; Black, R.E.; Rasmussen, K.M. Breast Milk or Animal-Product Foods Improve Linear Growth of Peruvian Toddlers Consuming Marginal Diets. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997, 66, 1102–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyango, A.W.; Borghi, E.; de Onis, M.; del Carmen Casanovas, M.; Garza, C. Complementary Feeding and Attained Linear Growth among 6–23-Month-Old Children. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1975–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyn, N.P.; Nel, J.H.; Nantel, G.; Kennedy, G.; Labadarios, D. Food Variety and Dietary Diversity Scores in Children: Are They Good Indicators of Dietary Adequacy? Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moramarco, S.; Amerio, G.; Palombi, L.; Buonomo, E. Nutritional Counseling Improves Dietary Diversity and Feeding Habits of Zambian Malnourished Children Admitted in Rainbow Nutritional Programs. Biomed. Prev. issues 2017, 1, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murendo, C.; Aziz, T.; Tirivanhu, D.; Mapfungautsi, R.; Stack, J.; Mutambara, S.; Langworthy, M.; Mafuratidze, C. Dietary Diversity and Food Coping Strategies in Zimbabwe: Do Resilience and Food Insecurity Status Matter? Ecol. Food Nutr. 2021, 60, 116–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FANTA Development of Evidence-Based Dietary Recommendations for Children, Pregnant Women, and Lactating Women Living in the Western Highlands of Guatemala; Washington DC, 2013.

- Singh, D.R.; Ghimire, S.; Upadhayay, S.R.; Singh, S.; Ghimire, U. Food Insecurity and Dietary Diversity among Lactating Mothers in the Urban Municipality in the Mountains of Nepal. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0227873. [Google Scholar]

- Oostendorp, R.; van Wesenbeeck, L.; Sonneveld, B.; Zikhali, P. Who Lacks and Who Benefits from Diet Diversity: Evidence from (Impact) Profiling for Children in Zimbabwe. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2020, 19, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alae-Carew, C.; Scheelbeek, P.; Carrillo-Larco, R.M.; Bernabé-Ortiz, A.; Checkley, W.; Miranda, J.J. Analysis of Dietary Patterns and Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Associations with Hypertension, High BMI and Type 2 Diabetes in Peru. Public Health Nutr. 2020, 23, 1009–1019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cordain, L.; Boyd Eaton, S.; Sebastian, A.; Mann, N.; Lindeberg, S.; Watkins, B.A.; O’Keefe, J. .; Brand-Miller, J. Origins and Evolution of the Western Diet: Health Implications for the 21st Century. Am J Clin Nutr 2005, 81, 341–354. [Google Scholar]

- Popkin, B.M.; Adair, L.S.; Ng, S.W. Global Nutrition Transition and the Pandemic of Obesity in Developing Countries. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Sibhatu, K.T.; Krishna, V. V; Qaim, M. Production Diversity and Dietary Diversity in Smallholder Farm Households. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2015, 112, 10657–10662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Harris, J.; Rawat, R. If They Grow It, Will They Eat and Grow? Evidence from Zambia on Agricultural Diversity and Child Undernutrition. J. Dev. Stud. 2015, 51, 1060–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.D. On-Farm Crop Species Richness Is Associated with Household Diet Diversity and Quality in Subsistence- and Market-Oriented Farming Households in Malawi. J. Nutr. 2017, 147 1, 86–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ekesa, B.; Walingo, M.K.; Abukutsa-Onyango, M. Influence of Agricultural Biodiversity on Dietary Diversity of Preschool Children in Matungu Division, Western Kenya. African J. Food, Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2009, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduor, F.O.; Boedecker, J.; Kennedy, G.; Termote, C. Exploring Agrobiodiversity for Nutrition: Household on-Farm Agrobiodiversity Is Associated with Improved Quality of Diet of Young Children in Vihiga, Kenya. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0219680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carletto, G.; Ruel, M.; Winters, P.; Zezza, A. Farm-Level Pathways to Improved Nutritional Status: Introduction to the Special Issue. J. Dev. Stud. 2015, 51, 945–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, S.; van den Bold, M. Agriculture, Food Systems, and Nutrition: Meeting the Challenge. Glob. Challenges 2017, 1, 1600002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food Systems Failure: The Global Food Crisis and the Future of Agriculture; Rosin, C., Stock, P., Campbell, H., Eds.; 1st ed.; Routledge, 2012.

- DeClerck, F.A.J.; Fanzo, J.; Palm, C.; Remans, R. Ecological Approaches to Human Nutrition. Food Nutr. Bull. 2011, 32, S41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, F.; Salam, R.A.; Lassi, Z.S.; Das, J.K. The Intertwined Relationship Between Malnutrition and Poverty. Front. Public Heal. 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, L.; Hussain, A.; Rasul, G. Tapping the Potential of Neglected and Underutilized Food Crops for Sustainable Nutrition Security in the Mountains of Pakistan and Nepal. Sustainability 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-El Dadon, S.; Abbo, S.; Reifen, R. Leveraging Traditional Crops for Better Nutrition and Health - The Case of Chickpea. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 64, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaenicke, H.; Dawson, I.K.; Guarino, L.; Hermann, M. Impacts of Underutilized Plant Species Promotion on Biodiversity. Acta Hortic. 2009, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yadav, R.; Siddique, K.H.M. Neglected and Underutilized Crop Species: The Key to Improving Dietary Diversity and Fighting Hunger and Malnutrition in Asia and the Pacific. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talabi, A.O.; Vikram, P.; Thushar, S.; Rahman, H.; Ahmadzai, H.; Nhamo, N.; Shahid, M.; Singh, R.K. Orphan Crops: A Best Fit for Dietary Enrichment and Diversification in Highly Deteriorated Marginal Environments. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruel, M.T.; Minot, N.; Smith, L. Patterns and Determinants of Fruit and Vegetable Consumption in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Multicountry Comparison; WHO: Geneva, 2005; ISBN 9241592834. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-García, V.; Guèze, M.; Luz, A.C.; Paneque-Gálvez, J.; Macía, M.J.; Orta-Martínez, M.; Pino, J.; Rubio-Campillo, X. Evidence of Traditional Knowledge Loss among a Contemporary Indigenous Society. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2013, 34, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Corbera, E.; Reyes-García, V. Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Global Environmental Change: Research Findings and Policy Implications. Ecol Soc 2013, 18, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meybeck, A.; Gitz, V. Sustainable Diets within Sustainable Food Systems. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2017, 76, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Robinson, S.; Garnett, T.; Godfray, H.C.J.; Gollin, D.; Rayner, M.; Ballon, P.; Scarborough, P. Global and Regional Health Effects of Future Food Production under Climate Change: A Modelling Study. Lancet 2016, 387, 1937–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uusitalo, U.; Pietinen, P.; Puska, P. Dietary Transition in Developing Countries: Challenges for Chronic Disease Prevention. In Globalization, Diets and Noncommunicable Diseases; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- McMullin, S.; Stadlmayr, B.; Mausch, K.; Revoredo-Giha, C.; Burnett, F.; Guarino, L.; Brouwer, I.D.; Jamnadass, R.; Graudal, L.; Powell, W.; et al. Determining Appropriate Interventions to Mainstream Nutritious Orphan Crops into African Food Systems. Glob. Food Sec. 2021, 28, 100465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldrum, G.; Padulosi, S.; Lochetti, G.; Robitaille, R.; Diulgheroff, S. Issues and Prospects for the Sustainable Use and Conservation of Cultivated Vegetable Diversity for More Nutrition-Sensitive Agriculture. Agriculture 2018, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulian, T.; Diazgranados, M.; Pironon, S.; Padulosi, S.; Liu, U.; Davies, L.; Howes, M.R.; Borrell, J.S.; Ondo, I.; Pérez-Escobar, O.A. Unlocking Plant Resources to Support Food Security and Promote Sustainable Agriculture. Plants, People, Planet 2020, 2, 421–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westengen, O.T.; Dalle, S.P.; Mulesa, T.H. Navigating toward Resilient and Inclusive Seed Systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2023, 120, e2218777120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clement, C.R. 1492 and the Loss of Amazonian Crop Genetic Resources. II. Crop Biogeography at Contact. Econ. Bot. 1999, 53, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, M.L.; Alves, R.P.; Hanazaki, N. Knowledge, Use, and Disuse of Unconventional Food Plants. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2018, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, B.F.; Cevallos, J.; Santana, F.; Rosales, J.; M., S.G. Losing Knowledge about Plant Use in the Sierra de Manantlan Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Econ. Bot. 2000, 183–191.

- Nolan, J.; Robbins, M. Cultural Conservation of Medicinal Plant Use in the Ozarks. Hum. Organ. 1999, 58, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, V.; Vadez, V.; Huanca, T.; Leonard, W.; Wilkie, D. Knowledge and Consumption of Wild Plants: A Comparative Study in Two Tsimane’villages in the Bolivian Amazon. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2005, 3, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathnasinghe, D.; Samarasinghe, G.; Silva, R.; Hunter, D. True Sri Lanka Taste’food Outlets: Promoting Indigenous Foods for Healthier Diets. Nutr. Exch 2019, 12, 14–15. [Google Scholar]

- Padulosi, S.; Mal, B.; King, O.I.; Gotor, E. Minor Millets as a Central Element for Sustainably Enhanced Incomes, Empowerment, and Nutrition in Rural India. Sustainability 2015, 7, 8904–8933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granos Andinos. Rojas, W., Soto, J.L., Pinto, M., Jäger, M., Padulosi, S., Eds.; Avances, Logros y Experiencias Desarrolladas En Quinua, Cañahua y Amaranto En Bolivia; Bioversity International: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, I.D.; Hendre, P.; Powell, W.; Sila, D.; McMullin, S.; Simons, T.; Revoredo-Giha, C.; Odeny, D.A.; Barnes, A.P.; Graudal, L. Supporting Human Nutrition in Africa through the Integration of New and Orphan Crops into Food Systems: Placing the Work of the African Orphan Crops Consortium in Context; 2018.

- McMullin, S.; Njogu, K.; Wekesa, B.; Gachuiri, A.; Ngethe, E.; Stadlmayr, B.; Jamnadass, R.; Kehlenbeck, K. Developing Fruit Tree Portfolios That Link Agriculture More Effectively with Nutrition and Health: A New Approach for Providing Year-Round Micronutrients to Smallholder Farmers. Food Secur. 2019, 11, 1355–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paumgarten, F.; Shackleton, C.M. The Role of Non-Timber Forest Products in Household Coping Strategies in South Africa: The Influence of Household Wealth and Gender. Popul. Environ. 2011, 33, 108–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.A.; Rakotobe, Z.L.; Rao, N.S.; Dave, R.; Razafimahatratra, H.; Rabarijohn, R.H.; Rajaofara, H.; MacKinnon, J.L. Extreme Vulnerability of Smallholder Farmers to Agricultural Risks and Climate Change in Madagascar. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 20130089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascual-Mendoza, S.; Saynes-Vásquez, A.; Pérez-Herrera, A. Traditional Knowledge of Edible Plants in an Indigenous Community in the Sierra Norte of Oaxaca, Mexico. Plant Biosyst. - An Int. J. Deal. with all Asp. Plant Biol. 2022, 156, 515–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Morin, D.R. Indigenous Communities and Their Food Systems: A Contribution to the Current Debate. J. Ethn. Foods 2020, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, M.C.M.; Araújo de Medeiros, M.F.; Albuquerque, U.P. Biodiverse Food Plants in the Semiarid Region of Brazil Have Unknown Potential: A Systematic Review. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0230936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackmore, I.; Rivera, C.; Waters, W.F.; Iannotti, L.; Lesorogol, C. The Impact of Seasonality and Climate Variability on Livelihood Security in the Ecuadorian Andes. Clim. Risk Manag. 2021, 32, 100279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seasonality, Rural Livelihoods and Development; Devereux, S., Sabates-Wheeler, R., Longhurst, R., Eds.; 1st ed.; Routledge, 2011.

- Burlingame, B. Wild Nutrition. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2000, 2, 99–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minnis, P.E. Famine Foods: Plants We Eat to Survive; University of Arizona Press, 2021; ISBN 0816542252.

- Ravaoarisoa, L.; Rakotonirina, J.; Randriamanantsaina, L.; de Dieu Marie Rakotomanga, J.; Dramaix, M.W.; Donnen, P. Food Consumption and Undernutrition Variations among Mothers during the Post-Harvest and Lean Seasons in Amoron’i Mania Region, Madagascar. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukpa, W. Minor Cereals and Food Security in the Marginal Areas of Bhutan. J. Renew. Nat. Resour. Bhutan 2006, 2, 73–92. [Google Scholar]

- Rubaihayo, E.B. Conservation and Use of Traditional Vegetables in Uganda. In Proceedings of the Proceedings on Genetic Resources of Traditional Vegetables in Africa: Options for Conservation and Use; ICRAF: Kenya; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Vitolas, C.A.; Harvey, C.A.; Cruz-Garcia, G.S.; Vanegas-Cubillos, M.; Schreckenberg, K. The Socio-Ecological Dynamics of Food Insecurity among Subsistence-Oriented Indigenous Communities in Amazonia: A Qualitative Examination of Coping Strategies among Riverine Communities along the Caquetá River, Colombia. Hum. Ecol. 2019, 47, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drysdale, R.E.; Moshabela, M.; Bob, U. Adapting the Coping Strategies Index to Measure Food Insecurity in the Rural District of ILembe, South Africa. Food, Cult. Soc. 2019, 22, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO Indigenous Peoples’ Food Systems and Well-Being: Interventions and Policies for Healthy Communities; Rome, Italy, 2013.

- Kuhnlein, H.V. Food System Sustainability for Health and Well-Being of Indigenous Peoples. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppmair, S.; Kassie, M.; Qaim, M. Farm Production, Market Access and Dietary Diversity in Malawi. Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, M.V.; De Giuseppe, R.; Monti, M.C.; Mkindi, A.G.; Mshanga, N.H.; Ceppi, S.; Msuya, J.; Cena, H. Indigenous Vegetables: A Sustainable Approach to Improve Micronutrient Adequacy in Tanzanian Women of Childbearing Age. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 75, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, A. School Gardening in Busia County, Kenya. Available online: http://www.b4fn.org/from-the-field/stories/school-gardening-in-busia-county-kenya (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Tan, A.; Adanacioğlu, N.; Tuğrul Ay, S. Students in Nature, in the Garden and in the Kitchen, Turkey. Available online: http://www.b4fn.org/case-studies/case-studies/students-in-nature-in-the-garden-and-in-the-kitchen (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Hunter, D.; Moura de Oliveira Beltrame, D. Biodiversity for Food and Nutrition in Brazil; Washington, D.C. 2015.

- Wineman, A.; Ekwueme, M.C.; Bigayimpunzi, L.; Martin-Daihirou, A.; de Gois VN Rodrigues, E.L.; Etuge, P.; Warner, Y.; Kessler, H.; Mitchell, A. School Meal Programs in Africa: Regional Results from the 2019 Global Survey of School Meal Programs. Front. Public Heal. 2022, 10, 871866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borelli, T.; Hunter, D.; Padulosi, S.; Amaya, N.; Meldrum, G.; de Oliveira Beltrame, D.M.; Samarasinghe, G.; Wasike, V.W.; Güner, B.; Tan, A.; et al. Local Solutions for Sustainable Food Systems: The Contribution of Orphan Crops and Wild Edible Species. Agronomy 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.; Borelli, T.; Beltrame, D.M.O.; Oliveira, C.N.S.; Coradin, L.; Wasike, V.W.; Wasilwa, L.; Mwai, J.; Manjella, A.; Samarasinghe, G.W.L. Potential of Orphan Crops for Improving Diets and Nutrition. Planta 2019, 250, 709–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gee, E.; Borelli, T.; Beltrame, D.; Oliveira, C.; Coradin, L.; Wasike, V.; Manjella, A.; Güner, B.; Tan, A.; Özbek, K.; et al. The ABC of Mainstreaming Biodiversity for Food and Nutrition. In Biodiversity, Food and Nutrition; Routledge, 2020; pp. 85–186 ISBN 9780429030574.

| Exercise Name | Content |

| Malnutrition problem tree | Malnutrition is a complex problem with multiple causes and consequences that may vary according to the local context. The exercise provides an in-depth and shared understanding of the root causes and consequences of malnutrition in the community. |

| Preparation of the local food plant list | FFS participants agree on a list of local food plants occurring in the community, whether in the wild, in farmers’ fields or in home gardens. Farmers are asked questions on properties of the listed plants, including in terms of their seasonality and their relevance in the scarcity period. |

| Timeline analysis of local food plants and nutrition | In this exercise, farmers assess how consumption patterns of local food plants and the quality of the nutrition in the communities changed in the past three decades, identifying the factors underlying such trends. |

| Seasonal calendar and coping strategies | FFS participants prepare a seasonal calendar of the community’s agroecosystem, indicating the food scarcity period. They also list the main strategies they adopt for coping with food scarcity, and subsequently sort the strategies according to how severe the scarcity period is (from 1 to 3, corresponding to low, medium or high severity). In the same exercise, participants recall the plants from the local food plant list and describe which of these are either available during the scarcity period or can be preserved to be made available as food during the scarcity period, or both. |

| Setting FFS research objectives and activities | In this exercise, FFS participants define and prioritize the objectives they wish to achieve with the FFS work, and their corresponding activities. |

| Country | Changes in consumption of local food plants | Changes in nutrition | Correlation | |||

| Decreased (%) | Same or increased (%) | Worsened (%) | Same or improved (%) | cor | p-value | |

| Uganda | 91 | 9 | 91 | 9 | 1 | < 2.2e-16 *** |

| Zambia | 100 | 0 | 84 | 16 | NA | NA |

| Zimbabwe | 92 | 8 | 83 | 17 | 0.67 | 0.0162 * |

| Guatemala | 100 | 0 | 50 | 50 | NA | NA |

| Peru | 100 | 0 | 87 | 13 | NA | NA |

| Nepal | 57 | 43 | 43 | 57 | -0.42 | 0.35 |

|

| Activity type | Percentage | Activities (detail) | Percentage |

| Field based activities | 48 | Sowing local food plants | 19 |

| Seed germination and breaking seed dormancy | 11 | ||

| Seed storage | 9 | ||

| Harvesting wild food plants | 6 | ||

| Creating school gardens | 3 | ||

| Mixed activities | 15 | Seed fairs and food fairs | 15 |

| Food based activities | 31 | Food preparation and cooking demonstrations | 23 |

| Food preservation | 8 | ||

| Other activities | 6 | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).