Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

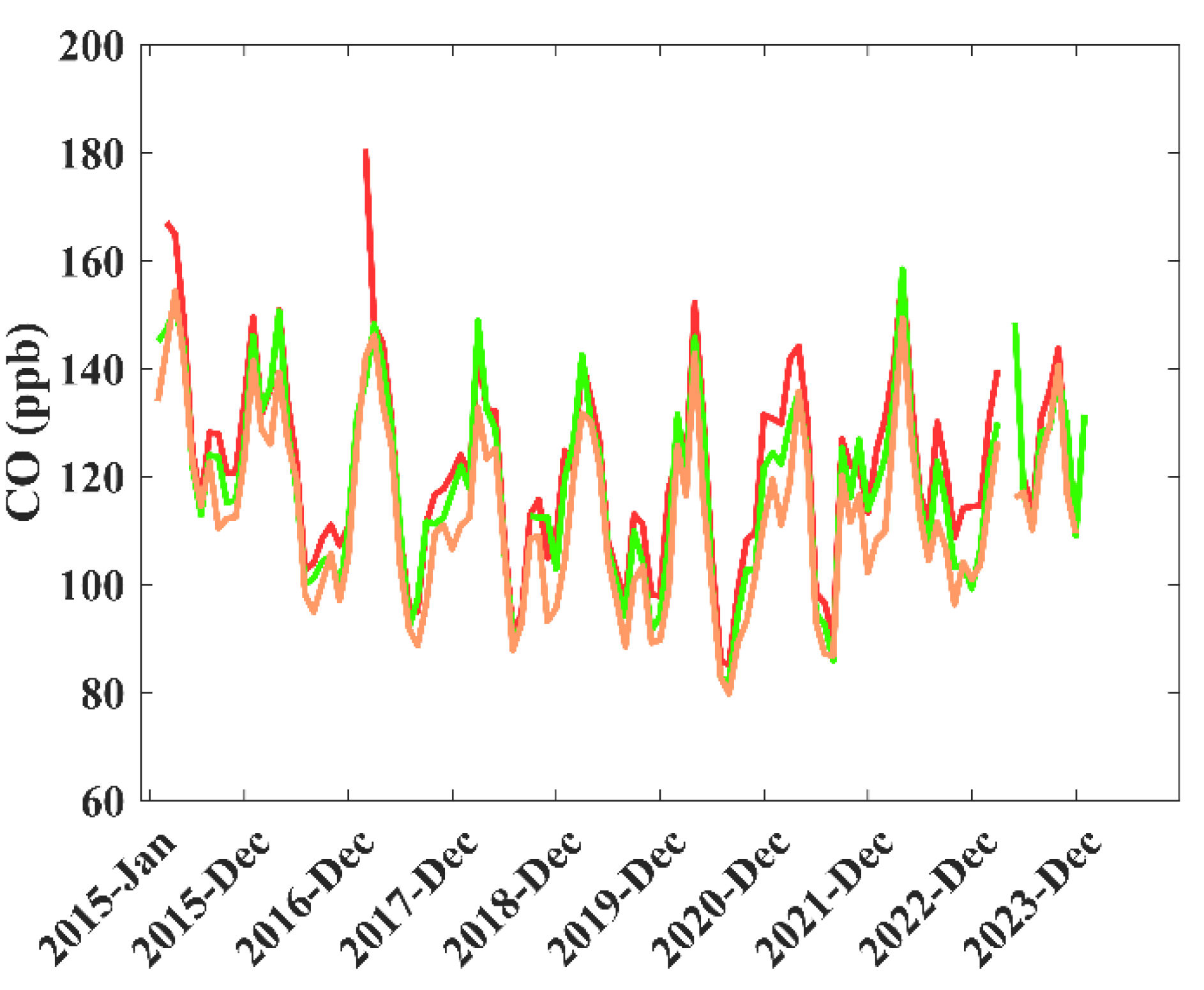

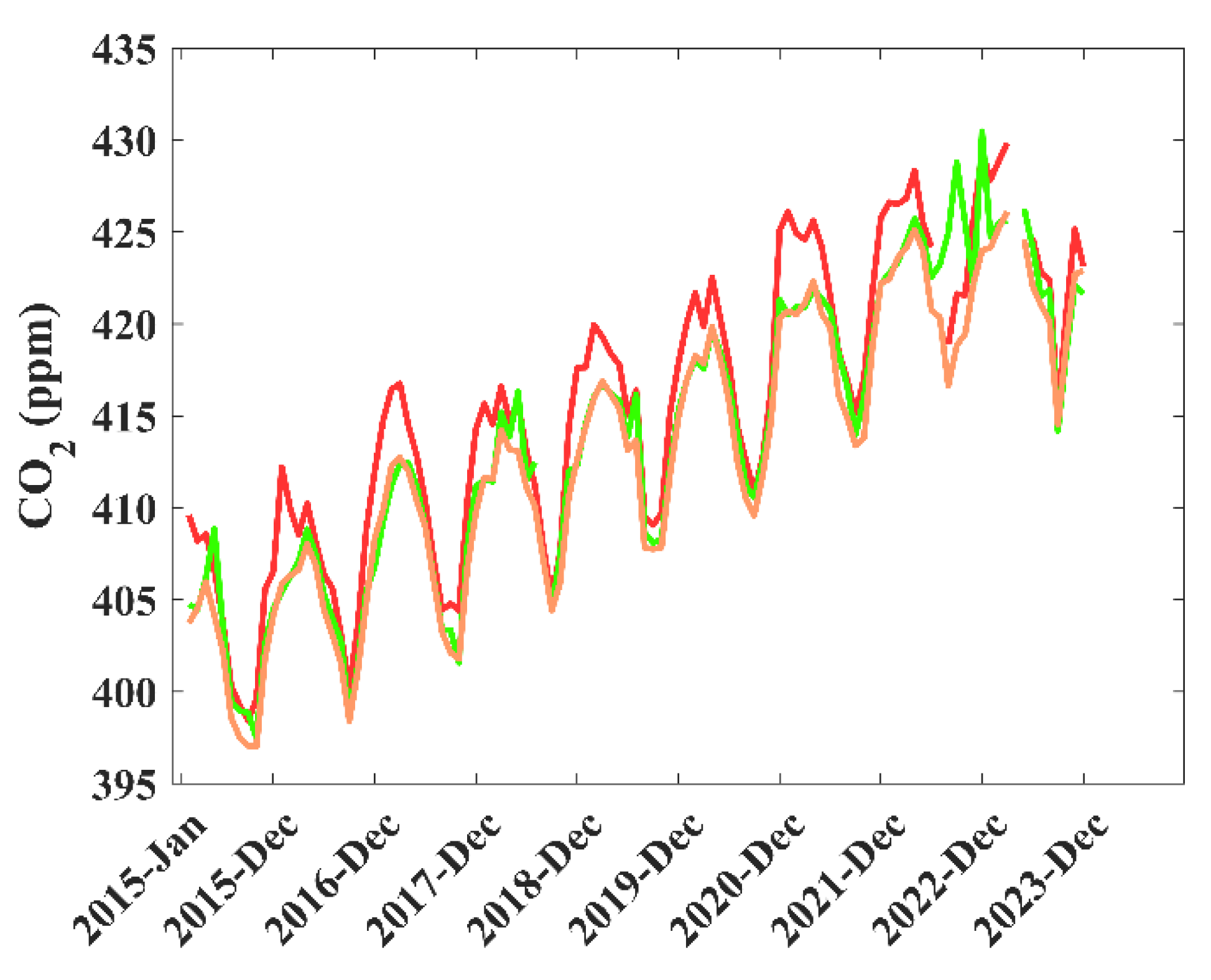

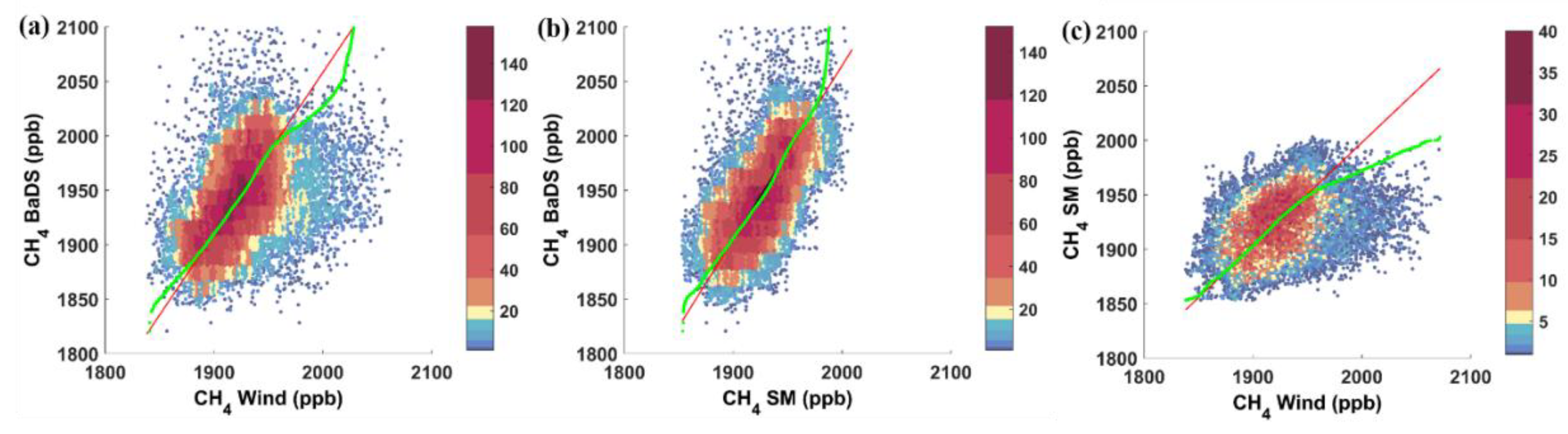

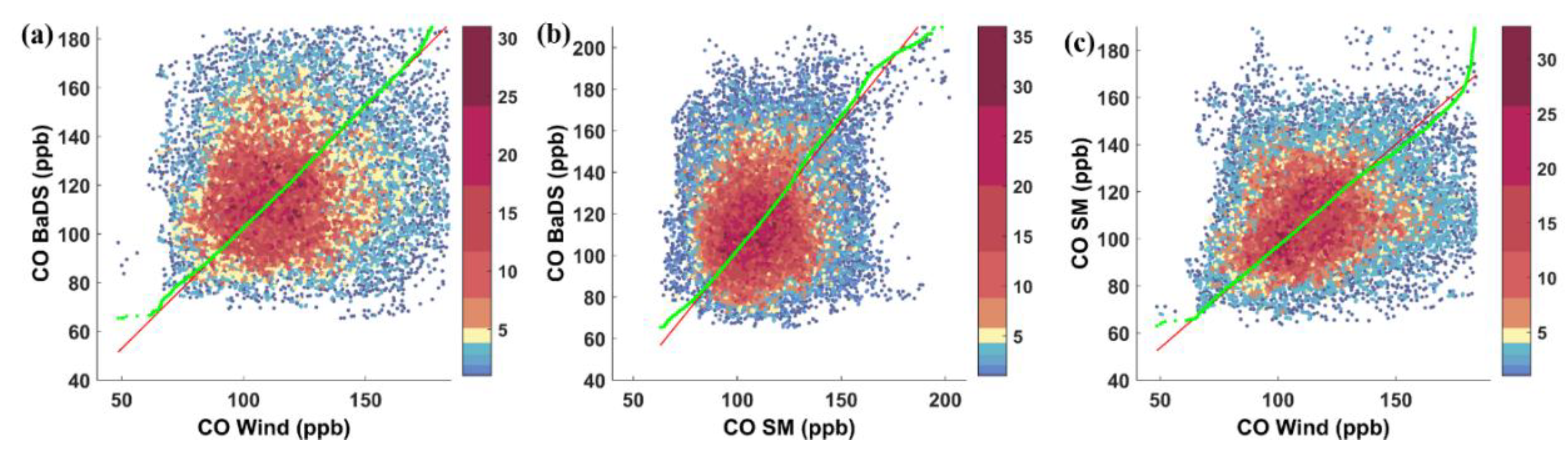

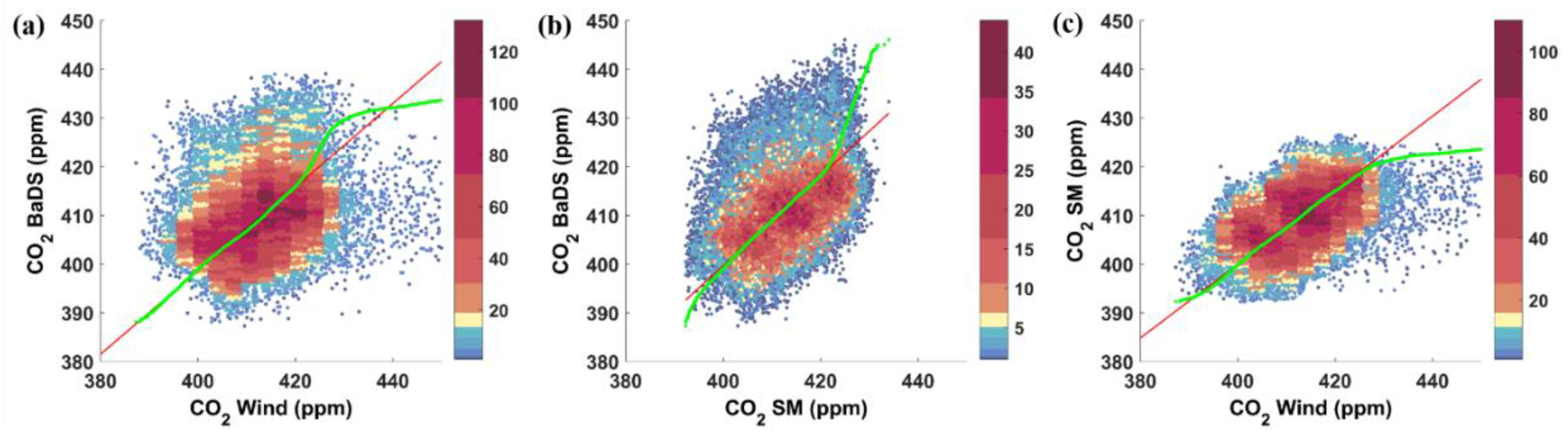

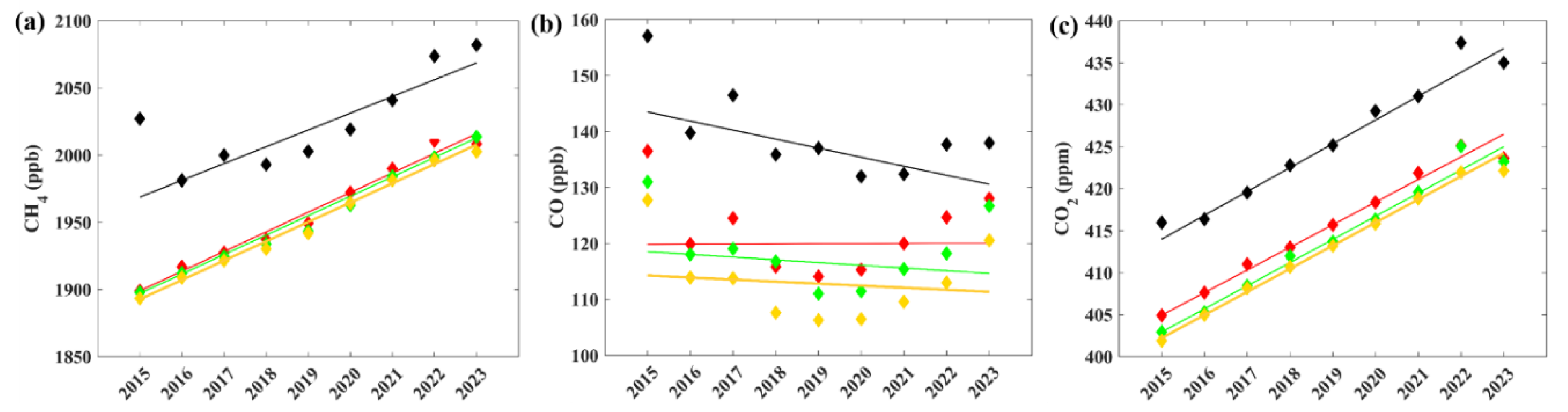

Since 2015, the permanent World Meteorological Organization/Global Atmosphere Watch (WMO/GAW) station of Lamezia Terme (LMT) in Calabria, Southern Italy, has been performing continuous measurements of atmospheric greenhouse gases (GHGs). As a coastal monitoring station, LMT allowed continuous data gathering of carbon dioxide (CO2), carbon monoxide (CO) and methane (CH4) mole fractions in a region characterized by a Mediterranean climate. This work aims to test the adoption of three different methods in the selection of observations representative of the atmospheric background conditions at LMT. In particular, we applied the Background Data Selection (BaDS) method, the smoothed minima baseflow separation method (SM), and the “Wind” method. All the three selection methods appeared to be effective in retaining the background CH4, CO and CO2 data. The “Wind” method, based on the analysis of the local wind regime, selected the lowest number of data. For all the gases considered, the monthly mean values obtained after the implementation of BaDS (SM) were the highest (lowest). Taking into account the complete gases datasets over the period 2015 - 2023, Mann-Kendall and Sen's slope showed annual and seasonal increasing tendencies for CH4 and CO2 with significance levels of α = 0.05 and α = 0.001, respectively. For CO, a decreasing tendency was only observed for the winter season level of α = 0.05. The application of the three selection methods resulted in changes in the calculated annual and seasonal growth rates and non-negligible deviations were also found for the average annual growth rates calculated for the three background datasets. This indicates that the growth rate calculations are sensitive to the choice of background selection method and we recommend that multiple selection methods could be applied to resolve the associated uncertainties.

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

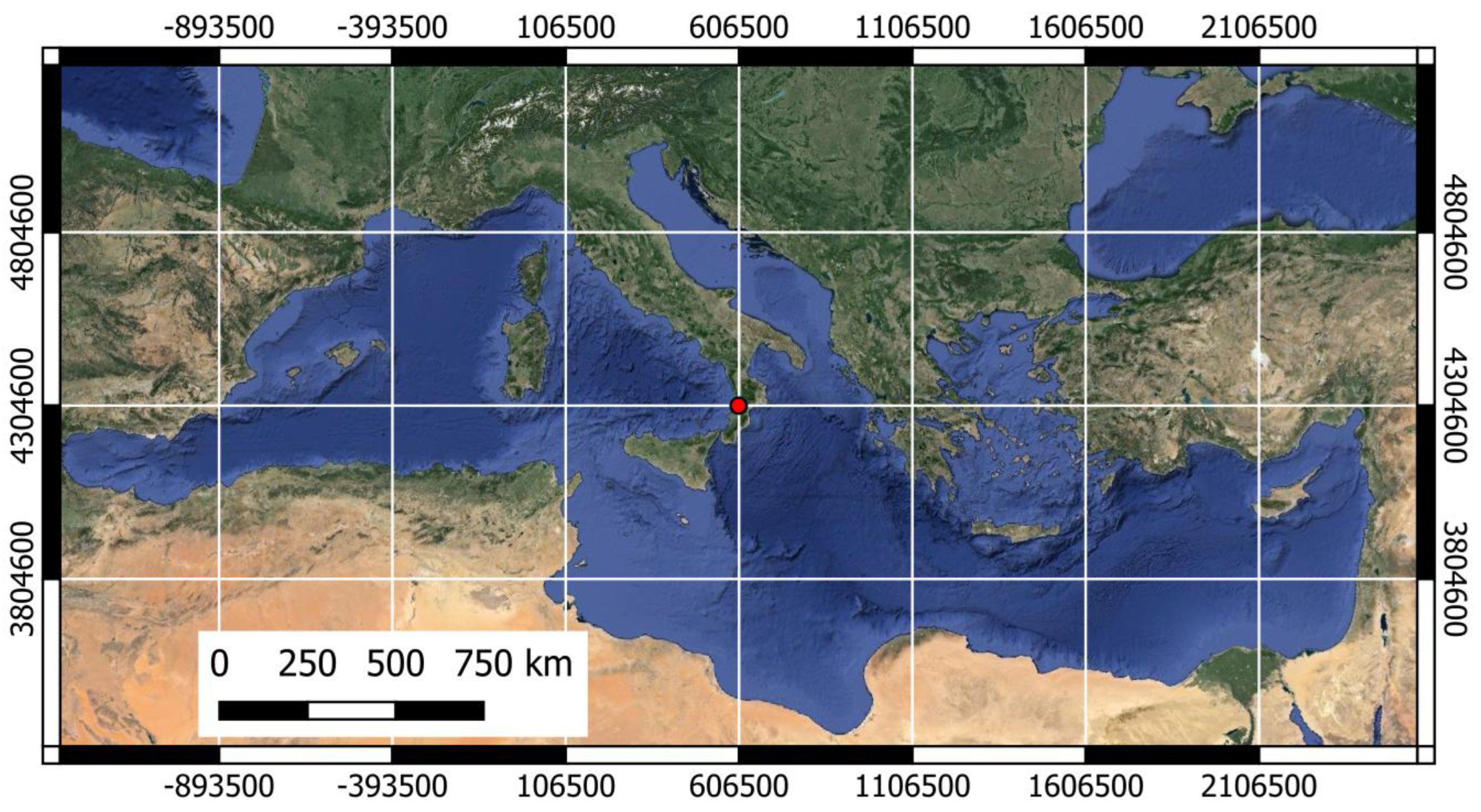

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Experimental

2.3. Description of the Models for Background Definition

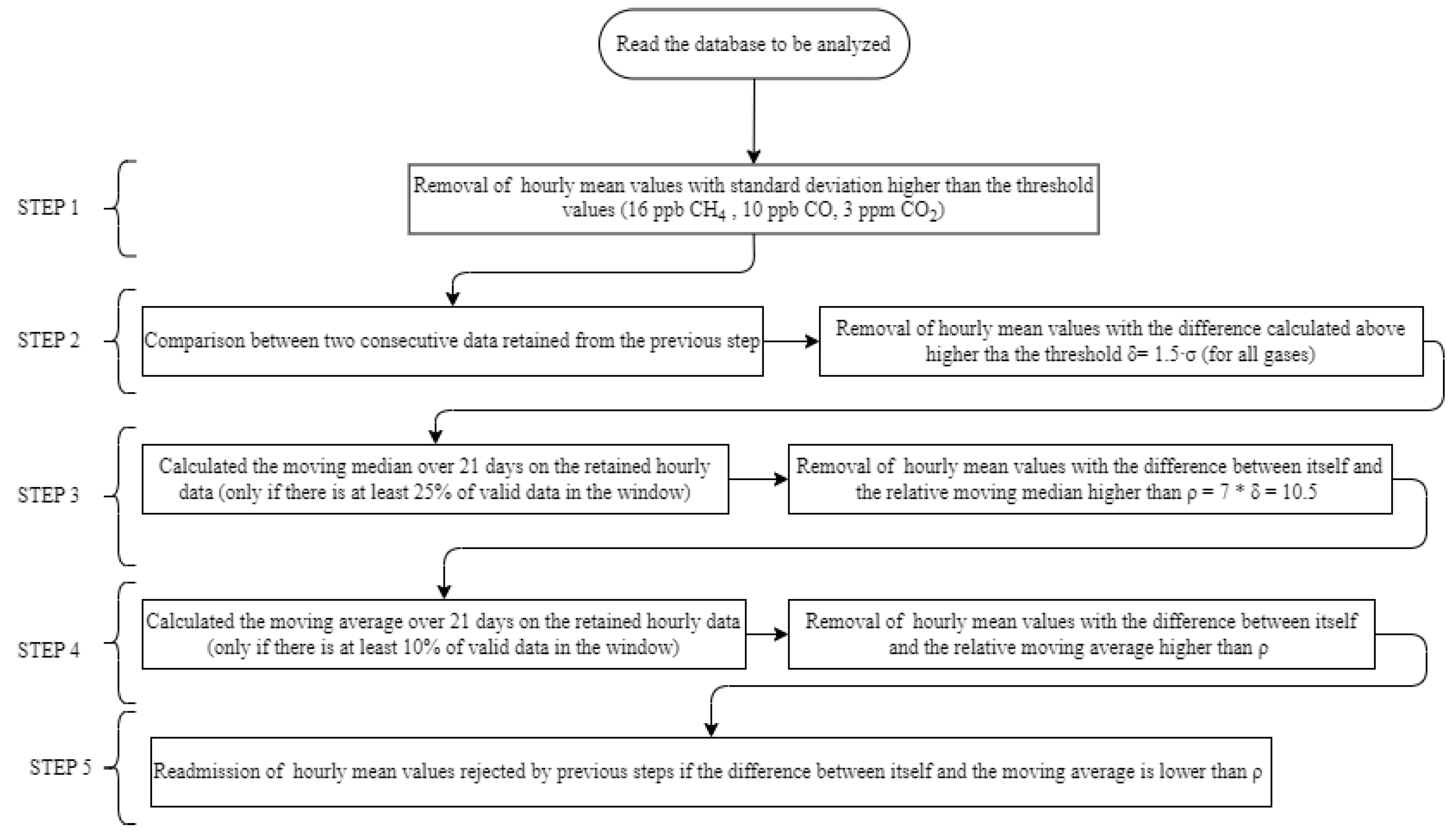

2.3.1. BaDS

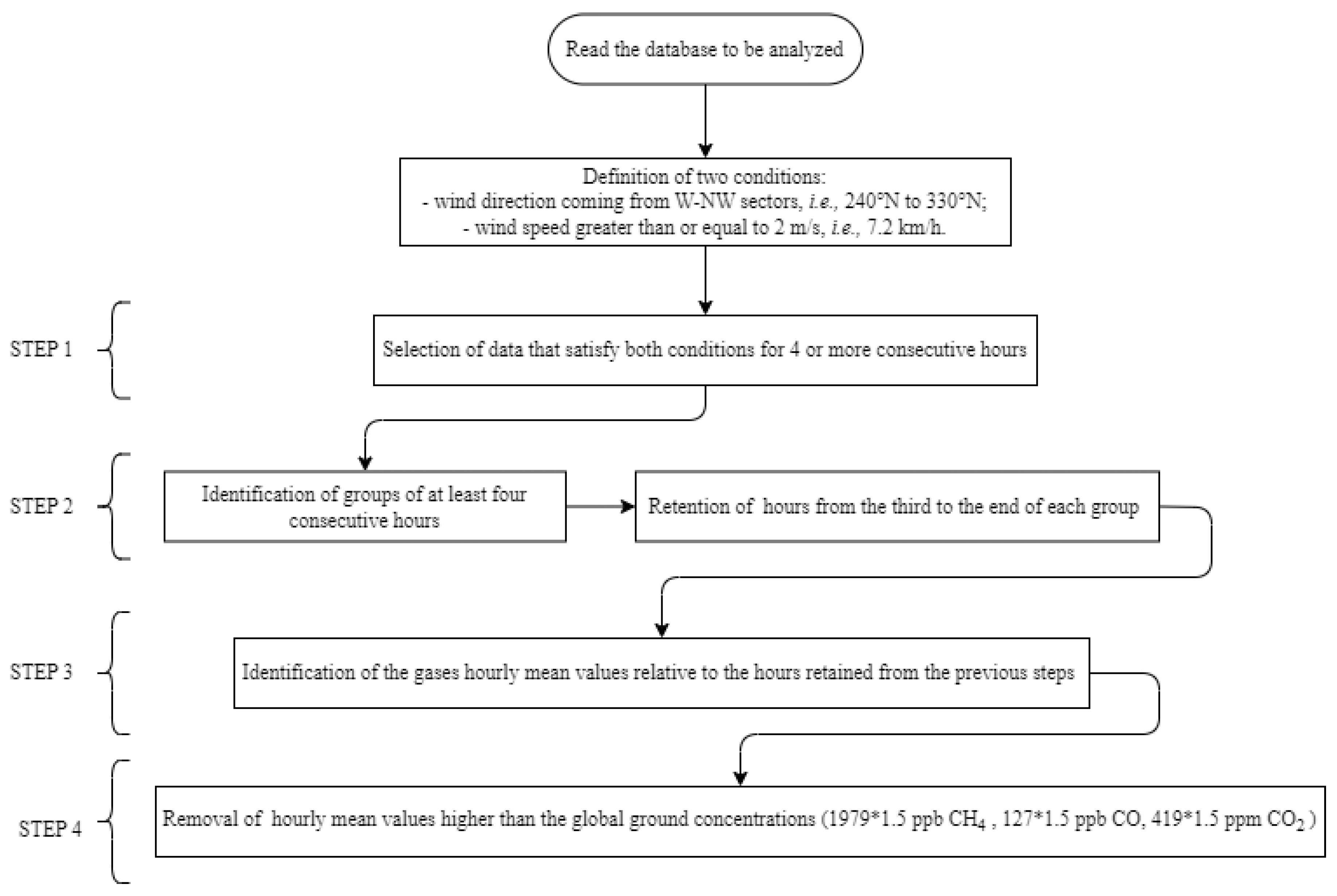

2.3.2. Meteorology-Based Selection

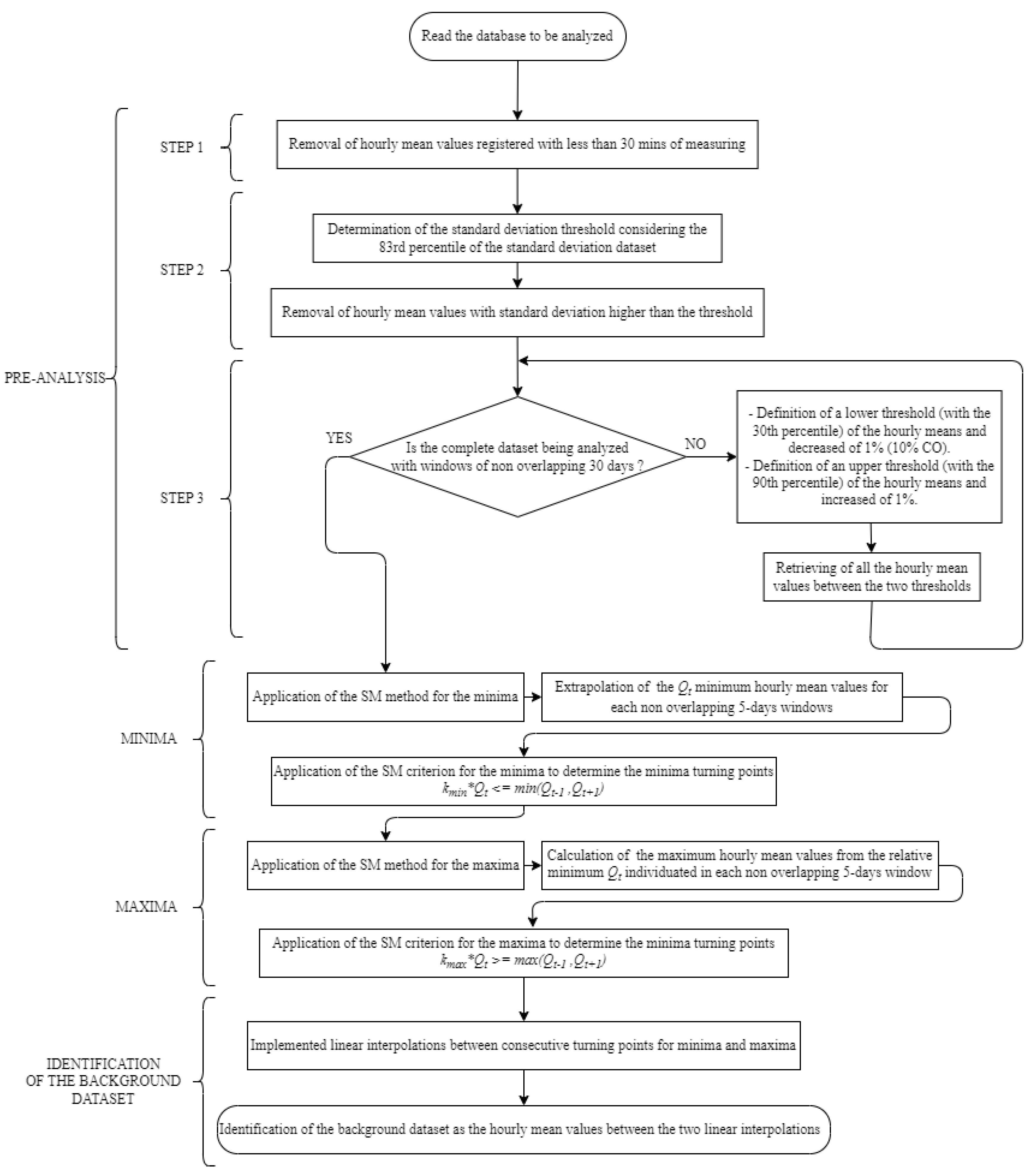

2.3.3. Smoothed Minima (SM)

- is the central minimum point of the sliding interval;

- is the previous minimum point of the same window;

- is the next minimum point of the same window;

- is a constant value of 0.995, experimentally perfected on the basis of the value reported by Hafzullah Aksoy et al. (2009).

2.4. Adopted Metrics for Calculating Temporal Tendencies

2.4.1. Adopted Metrics to Compare Background Selection Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aksoy, H. , Kurt, I., Eris, E. Filtered smoothed minima baseflow separation method. Journal of Hydrology 2009, 372, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexe, M. , Bergamaschi, P., Segers, A., Detmers, R., Butz, A., Hasekamp, O., Guerlet, S., Parker, R., Boesch, H., Frankenberg, C., et al. Inverse modelling of CH4 emissions for 2010–2011 using different satellite retrieval products from GOSAT and SCIAMACHY. Atmos. Chem. Phys 2015, 15, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, A.E. , Kofler, J.D., Trudeau, M.E., Williams, J.C., Neff, D.H., Masarie, K.A., Chao, D.Y., Kitzis, D.R., Novelli, P.C., Zhao, C.L., Dlugokencky, E.J., Lang, P.M., Crotwell, M.J., Fischer, M.L., Parker, M.J., Lee, J.T., Baumann, D.D., Desai, A.R., Stanier, C.O., De Wekker, S.F.J., Wolfe, D.E., Munger, J.W., Tans, P.P. CO2, CO, and CH4 measurements from tall towers in the NOAA Earth System Research Laboratory’s Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network: instrumentation, uncertainty analysis, and recommendations for future high-accuracy greenhouse gas monitoring efforts. Atmos. Meas. Tech 2014, 7, 647–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apadula, F. , Cassardo, C., Ferrarese, S., Heltai, D., Lanza, A. Thirty Years of Atmospheric CO2 Observations at the Plateau Rosa Station, Italy. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artuso, F. , Chamard, P., Piacentino, S., Sferlazzo, D.M., De Silvestri, L., Di Sarra, A., Meloni, D., Monteleone, F. Influence of transport and trends in atmospheric CO2 at Lampedusa. Atmos. Environ 2009, 43, 3044–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzani Lo¨o¨v, J.M. , Henne, S., Legreid, G., Staehelin, J., Reimann, S., Pre´voˆt, A.S.H., Steinbacher, M., Vollmer, M.K. Estimation of background concentrations of trace gases at the Swiss Alpine site Jungfraujoch (3580 m asl). Journal of Geophysical Research 2008, 113, D22305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamaschi, P. , Houweling, S., Segers, A., Krol, M., Frankenberg, C., Scheepmaker, R.A., Dlugokencky, E., Wofsy, S.C., Kort, E.A., Sweeney, C., et al. Atmospheric CH4 in the first decade of the 21st century: Inverse modeling analysis using SCIAMACHY satellite retrievals and NOAA surface measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos 2013, 118, 7350–7369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calidonna, C.R. , et al. Five years of dust episodes at the Southern Italy GAW Regional Coastal Mediterranean Observatory: Multisensors and modeling analysis. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, L. , Green, T., Mills, G., Bauguitte, S., Penkett, S., Zanis, P., Schuepbach, E., Schmidbauer, N., Monks, P., Zellweger, C. Oxidized nitrogen and ozone production efficiencies in the springtime free troposphere over the Alps. J. Geophys. Res 2000, 105, 14547–14559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. , Winderlich, J., Gerbig, C., Hoefer, A., Rella, C. W., Crosson, E. R., Van Pelt, A. D., Steinbach, J., Kolle, O., Beck, V., Daube, B.C., Gottlieb, E. W., Chow, V. Y., Santoni, G. W., and Wofsy, S. C. High-accuracy continuous airborne measurements of greenhouse gases (CO2 and CH4) using the cavity ringdown spectroscopy (CRDS) technique. Atmos. Meas. Tech 2010, 3, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. , Karion, A., Rella, C. W., Winderlich, J., Gerbig, C., Filges, A. Accurate measurements of carbon monoxide in humid air using the cavity ring-down spectroscopy (crds) technique. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 2013, 6, 1031–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimmins, A. Improving the use of calibrated language in US climate assessments. Earth’s Future 2020, 8, e2020EF001817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofanelli, P. , Busetto, M., Calzolari, F., Ammoscato, I., Gullì, D., Dinoi, A., Calidonna, C.R., Contini, D., Sferlazzo, D., Di Iorio, T., Piacentino, S., Marinoni, A., Maione, M., Bonasoni, P. Investigation of reactive gases and methane variability in the coastal boundary layer of the central Mediterranean basin. Elem. Sci. Anth 2017, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cundari, V. , Colombo, T., Ciattaglia, L. Thirteen years of atmospheric carbon dioxide measurements at Mt. Cimone station, Italy. Il Nuovo Cim. C 1995, 18, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curcoll, R. , Camarero, L., Bacardit, M., Agueda, A., Grossi, C., Gacia, E., Font, A., Morguí, J.-A. Atmospheric carbon dioxide variability at Aigüestortes, central Pyrenees, Spain. Reg. Environ. Change 2019, 19, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F. , Ammoscato, I., Gullì, D., Avolio, E., Lo Feudo, T., De Pino, M., Cristofanelli, P., Malacaria, L., Parise, D., Sinopoli, S., De Benedetto, G., Calidonna, C.R. Integrated Analysis of Methane Cycles and Trends at the WMO/GAW Station of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy). Atmosphere 2024, 2024071587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F. , Gullì, D., Lo Feudo, T., Ammoscato, I., Avolio, E., De Pino, M., Cristofanelli, P., Busetto, M., Malacaria, L., Parise, D., Sinopoli, S., De Benedetto, G., Calidonna, C.R. Cyclic and multi-year characterization of surface ozone at the WMO/GAW coastal station of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy): implications for the local environment, cultural heritage, and human health. Environments 2024, 11, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, F. , Ammoscato, I., Gullì, D., Avolio, E., Lo Feudo, T., De Pino, M., Cristofanelli, P., Malacaria, L., Parise, D., Sinopoli, S., De Benedetto, G., Calidonna, C.R. Trends in CO, CO2, CH4, BC, and NOx during the First 2020 COVID-19 Lockdown: Source Insights from the WMO/GAW Station of Lamezia Terme (Calabria, Southern Italy). Atmosphere 2024, 2024071587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwent, R. , Simmonds, P., O’Doherty, S., Ciais, P., Ryall, D. European source strengths and northern hemisphere baseline concentrations of radiatively active trace gases at Mace Head, Ireland. Atmos. Environ 1998, 32, 3703–3715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.P. , et al. Observations of carbon monoxide and aerosols from the Terra satellite: Northern Hemisphere variability. Journal of geophysical research 2004, 109, D24202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federico, S. , Pasqualoni, L., Sempreviva, A.M., De Leo, L., Avolio, E., Calidonna, C.R., Bellecci, C. The seasonal characteristics of the breeze circulation at a coastal Mediterranean site in South Italy. Adv. Sci. Res 2010, 4, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrer, J. , Rüttimann, R., Schneiter, D., Fischer, A., Buchmann, B., Hofer, P. Variability of trace gases at the high-Alpine site Jungfraujoch caused by meteorological transport processes. J. Geophys. Res 2000, 105, 12241–12251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortems-Cheiney, A. , Broquet, G., Potier, E., Plauchu, R., Berchet, A., Pison, I., Denier van der Gon, H., Dellaert, S. CO anthropogenic emissions in Europe from 2011 to 2021: insights from Measurement of Pollution in the Troposphere (MOPITT) satellite data. Atmos. Chem. Phys 2024, 24, 4635–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, M. , Sha, M.K., Hase, F., Kiel, M., Blumenstock, T., Harig, R., Surawicz, G., Deutscher, N.M., Shiomi, K., Franklin, J.E., et al. Building the Collaborative Carbon Column Observing Network (COCCON): Long-term stability and ensemble performance of the EM27/SUN Fourier transform spectrometer. Atmos. Meas. Tech 2019, 12, 1513–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P. , O'sullivan, M., Jones, M.W., Andrew, R.M., Bakker, D.C., Hauck, J.,... & Zheng, B. Global carbon budget 2023. Earth System Science Data 2023, 15, 5301–5369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaoa, S. , Yangb, W., Zhanga, H., Suna, Y., Maoa, J., Maa, Z., Congc, Z., Zhanga, X., Tiana, S., Azzid, M., Chena, L., Bai, Z. Estimating representative background PM2.5 concentration in heavily polluted areas using baseline separation technique and chemical mass balance model. Atmospheric Environment 2018, 174, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gialesakis, N. , Kalivitis, N., Kouvarakis, G., Ramonet, M., Lopez, M., Yver Kwok, C., Narbaud, C., Daskalakis, N., Mihalopoulos, N., Kanakidou, M. A twenty years record of greenhouse gases in the East Mediterranean atmosphere. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 864, 161003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, R.O. , 1987. Statistical methods for environmental pollution monitoring. John Wiley & Sons.

- Gomez-Pelaez, A. J. , Ramos, R., Cuevas, E., Gomez-Trueba, V., and Reyes, E. Atmospheric CO2, CH4, and CO with the CRDS technique at the Izaña Global GAW station: instrumental tests, developments, and first measurement results. Atmos. Meas. Tech 2019, 12, 2043–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.D. , Crotwell, A.M., Kitzis, D.R., Mefford, T., Miller, B.R., Schibig, M.F., Tans, P.P. Revision of the World Meteorological Organization Global Atmosphere Watch (WMO/GAW) CO2 calibration scale. Atmos. Meas. Tech 2021, 14, 3015–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazan, L. , Tarniewicz, J., Ramonet, M., Laurent, O., Abbaris, A. Automatic processing of atmospheric CO2 and CH4 mole fractions at the ICOS Atmosphere Thematic Centre. Atmos. Meas. Tech 2016, 9, 4719–4736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helsel, D.R. , Hirsch, R.M., 1993. Statistical methods in water resources. Elsevier.

- Henne, S. , Furger, M., Prevot, A. Climatology of mountain venting-induced elevated moisture layers in the lee of the Alps. J. Appl. Meteorol 2005, 44, 620–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirdman, D. , Sodemann, H., Eckhardt, S., Burkhart, J.F., Jefferson, A., Mefford, T., Quinn, P.K., Sharma, S., Ström, J., Stohl, A. Source identification of short-lived air pollutants in the Arctic using statistical analysis of measurement data and particle dispersion model output. Atmos. Chem. Phys 2010, 10, 669–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K., Meyer, L.A., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; 151p. [Google Scholar]

- NOAA Technical memorandum; The statistical treatment of CO2 data records, (NOAA, 1989) Available online: https://www.arl.noaa.gov/documents/reports/arl-173.pdf.

- Irannezhad, M. , Marttila, H., Chen, D., Kløve, B. Century-long variability and trends in daily precipitation characteristics at three Finnish stations. Adv. Clim. Chang. Res 2016, 7, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeling, C.D. The concentration and isotopic abundances of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Tellus 1960, 12, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA.

- Kisi, O. , 2015. An innovative method for trend analysis of monthly pan evaporations. J. Hydrol 1975, 527, 1123–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, X. , Thoning, K.W., Dlugokencky, E.J., Trends in globally-averaged CH4, N2O, and SF6 determined from NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory measurements. Version 2024-06. [CrossRef]

- Laughner, J.L. , Neu, J.L., Schimel, D., Wennberg, P.O., Barsanti, K., Bowman, K.W., Chatterjee, A., Croes, B.E., Fitzmaurice, H.L., Henze, D.K., Kim, J., Kort, E.A., Liu, Z., Miyazaki, K., Turner, A.J., Anenberg, S., Avise, J., Cao, H., Crisp, D., de Gouw, J., Eldering, A., Fyfe, J.C., Goldberg, D.L., Gurney, K. R., Hasheminassab, S., Hopkins, F., Ivey, C.E., Jones, D.B.A., Liu, J., Lovenduski, N.S., Martin, R.V., McKinley, G.A., Ott, L., Poulter, B., Ru, M., Sander, S.P., Swart, N., Yung, Y.L., Zeng, Z.-C. Societal shifts due to COVID-19 reveal large-scale complexities and feedbacks between atmospheric chemistry and climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2021, 118, e2109481118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malacaria, L. , Parise, D., Lo Feudo, T., Avolio, E., Ammoscato, I., Gullì, D., Sinopoli, S., Cristofanelli, P., De Pino, M., D’Amico, F., Calidonna, C.R. Multiparameter Detection of Summer Open Fire Emissions: The Case Study of GAW Regional Observatory of Lamezia Terme (Southern Italy). Fire 2024, 7, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric tests against trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNorton, J. , Bousserez, N., Agustí-Panareda, A., Balsamo, G., Cantarello, L., Engelen, R., Huijnen, V., Inness, A., Kipling, Z., Parrington, M., Ribas, R. Quantification of methane emissions from hotspots and during COVID-19 using a global atmospheric inversion. Atmos. Chem. Phys 2022, 22, 5961–5981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nashwan, M.S. , Shahid, S. Spatial distribution of unidirectional trends in climate and weather extremes in Nile river basin. Theor. Appl. Climatol 2019, 137, 1181–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA Technical memorandum; The statistical treatment of CO2 data records, (NOAA, 1989) Available online: https://www.arl.noaa.gov/documents/reports/arl-173.pdf.

- Olivier, J.G.J. , Van Aardenne, J. A., Dentener, F.J., Pagliari, V., Ganzeveld, L.N., Peters, J.A.H.W. Recent trends in global greenhouse gas emissions: regional trends 1970–2000 and spatial distributionof key sources in 2000. Environmental Sciences 2005, 2, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztopal, A. , Sen, Z. Innovative Trend Methodology Applications to Precipitation Records in Turkey. Water Resour. Manag 2017, 31, 727–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S. , Lin, X., Thompson, R.L., Xi, Y., Liu, G., Hauglustaine, D., Lan, X., Poulter, B., Ramonet, M., Saunois, M., Yin, Y., Zhang, Z., Zheng, B., Ciais, P. Wetland emission and atmospheric sink changes explain methane growth in 2020. Nature 2022, 612, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prinn, R.G. , Weiss, R.F., Fraser, P.J., Simmonds, P.G., Cunnold, D.M., Alyea, F.N., O’Doherty, S., Salameh, P., Miller, B.R., Huang, J., et al. A history of chemically and radiatively important gases in air deduced from ALE/GAGE/AGAGE. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos 2000, 105, 17751–17792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rella, C. 2010. Accurate Greenhouse Gas Measurements in Humid Gas Streams Using the Picarro G1301 Carbon Dioxide/Methane/Water Vapor Gas Analyzer. https://www.picarro.com/assets/docs/White_Paper_G1301_Water_Vapor_Correction.pdf.

- Rella, C. W. , Chen, H., Andrews, A. E., Filges, A., Gerbig, C., Hatakka, J., Karion, A., Miles, N. L., Richardson, S. J., Steinbacher, M., Sweeney, C., Wastine, B., and Zellweger, C. High accuracy measurements of dry mole fractions of carbon dioxide and methane in humid air. Atmos. Meas. Tech 2013, 6, 837–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reum, F. , Göckede, M., Lavric, J. V., Kolle, O., Zimov, S., Zimov, N., Pallandt, M., and Heimann, M. Accurate measurements of atmospheric carbon dioxide and methane mole fractions at the Siberian coastal site Ambarchik. Atmos. Meas. Tech 2019, 12, 5717–5740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryall, D.B. , Derwent, R., Manning, A., Simmonds, P., O’Doherty, S. Estimating source regions of European emissions of trace gases from observations at Mace Head. Atmos. Environ 2001, 35, 2507–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotmans, J. , Swart, R.J. The role of the CH4-CO-OH cycle in the greenhouse problem. The Science of the Total Environment 1990, 94, 233–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckstuhl, A.F. , Henne, S., Reimann, S., Steinbacher, M., Vollmer, M.K., O’Doherty, S., Buchmann, B., Hueglin, C. Robust extraction of baseline signal of atmospheric trace species using local regression. Atmos. Meas. Technol 2012, 5, 2613–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.G. , Akimoto, H., Bottenheim, J., Buchmann, B., Galbally, I.E., Gilge, S., Helmig, D., Koide, H., Lewis, A.C., Novelli, P.C., Plass-Dülmer, C., Ryerson, T.B., Steinbacher, M., Steinbrecher, R., Tarasova, O., Tørseth, K., Thouret, V., Zellweger, C. The Global Atmosphere Watch reactive gases measurement network. Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene 2015, 3, 000067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şen, Z. Innovative Trend Analysis Methodology. J. Hydrol. Eng 2012, 17, 1042–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. , Bian, L., Tang, J., Gao, Z., Lu, C., Schnell, R.C. CO2 monitoring and background mole fraction at Zhongshan station, Antarctica. Atmosphere 2014, 5, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoning, K. , Tans, P., Komhyr, W. Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide at Mauna Loa Observatory. 2. Analysis of the NOAA GMCC Data, 1974–1985. J. Geophys. Res 1989, 94, 8549–8565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trisolino, P. , Di Sarra, A., Sferlazzo, D., Piacentino, S., Monteleone, F., Di Iorio, T., Apadula, F., Heltai, D., Lanza, A., Vocino, A., Caracciolo di Torchiarolo, L., Bonasoni, P., Calzolari, F., Busetto, M., Cristofanelli, P. Application of a Common Methodology to Select in Situ CO2 Observations Representative of the Atmospheric Background to an Italian Collaborative Network. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsutsumi, Y. , Mori, K., Ikegami, M., Tashiro, T., Tsuboi, K. Long-term trends of greenhouse gases in regional and background events observed during 1998–2004 at Yonagunijima located to the east of the Asian continent. Atmospheric Environment 2006, 40, 5868–5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, A.J. , Fung, I., Naik, V., Horowitz, L.W., Cohen, R.C. Modulation of hydroxyl variability by ENSO in the absence of external forcing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, 8931–8936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uglietti, C. , Leuenberger, M., Brunner, D. Large-scale European source and flow patterns retrieved from back-trajectory interpretations of CO&1t; sub> 2 </ sub> at the high alpine research station Jungfraujoch. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss 2011, 11, 813–857. [Google Scholar]

- . [CrossRef]

- Uglietti, C. , Leuenberger, M., Brunner, D. European source and sink areas of CO2 retrieved from Lagrangian transport model interpretation of combined O2 and CO2 measurements at the high alpine research station Jungfraujoch. Atmos. Chem. Phys 2011, 11, 8017–8036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallero, D.A. Chapter 8-Air pollution biogeochemistry. Air Pollution Calculations 2019, 175–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Schneidemesser, E. , et al. Chemistry and the Linkages between Air Quality and Climate Change. Chemical reviews 2015, 115, 3856–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO. Greenhouse Gas Bulletin, No. 14|22. November 2018. Available online: https://library.wmo.int/records/item/58673-no-14-22-november-2018 (accessed on 30 December 2020).

- WMO Global Atmosphere Watch Implementation Plan, 2016–2023 (WMO, 2017). Available online: https://wmo.int/activities/global-atmosphere-watch-programme-gaw (accessed on 30 December 2020).

- Wu, H. , Qian, H. Innovative trend analysis of annual and seasonal rainfall and extreme values in Shaanxi, China, since the 1950s. Int. J. Climatol 2017, 37, 2582–2592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y. , Ries, L., Petermeier, H., Steinbacher, M., Gómez-Peláez, A.J., Leuenberger, M.C., Schumacher, M., Trickl, T., Couret, C., Meinhardt, F., Menzel, A. Adaptive selection of diurnal minimum variation: A statistical strategy to obtain representative atmospheric CO2 data and its application to European elevated mountain stations. Atmos. Meas. Technol 2018, 11, 1501–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yver-Kwok, C. , Philippon, C., Bergamaschi, P., Biermann, T., Calzolari, F., Chen, H., Conil, S., Cristofanelli, P., Delmotte, M., Hatakka, J., Heliasz, M., Hermansen, O., Komínková, K., Kubistin, D., Kumps, N., Laurent, O., Laurila, T., Lehner, I., Levula, J., Lindauer, M., Lopez, M., Mammarella, I., Manca, G., Marklund, P., Metzger, J.-M., Mölder, M., Platt, S. M., Ramonet, M., Rivier, L., Scheeren, B., Sha, M. K., Smith, P., Steinbacher, M., Vítková, G., and Wyss, S. Evaluation and optimization of ICOS atmosphere station data as part of the labeling process. Atmos. Meas. Tech 2021, 14, 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanis, P. , Ganser, A., Zellweger, C., Henne, S., Steinbacher, M., Staehelin, J. Seasonal variability of measured ozone production efficiencies in the lower free troposphere of Central Europe. Atmos. Chem. Phys 2007, 7, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, C. , Forrer, J., Hofer, P., Nyeki, S., Schwarzenbach, B., Weingartner, E., Ammann, M., Baltensperger, U. Partitioning of reactive nitrogen (NOy) and dependence on meteorological conditions in the lower free troposphere. Atmos. Chem. Phys 2003, 3, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, C. , Emmenegger, L., Firdaus, M., Hatakka, J., Heimann, M., Kozlova, E., Spain, T. G., Steinbacher, M., van der Schoot, M. V., and Buchmann, B. Assessment of recent advances in measurement techniques for atmospheric carbon dioxide and methane observations. Atmos. Meas. Tech 2016, 9, 4737–4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, C. , Steinbrecher, R., Laurent, O., Lee, H., Kim, S., Emmenegger, L., Steinbacher, M., and Buchmann, B. Recent advances in measurement techniques for atmospheric carbon monoxide and nitrous oxide observations. Atmos. Meas. Tech 2019, 12, 5863–5878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F. , Zhou, L., Conway, T.J., Tans, P.P., Wang, Y. Short-term variations of atmospheric CO2 and dominant causes in summer and winter: Analysis of 14-year continuous observational data at Waliguan, China. Atmos. Environ 2013, 77, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y. , Saunois, M., Bousquet, P., Lin, X., Berchet, A., Hegglin, M.I., Canadell, J.G., Jackson, R.B., Deushi, M., Jöckel, P., Kinnison, D., Kirner, O., Strode, S., Tilmes, S., Dlugokencky, E.J., Zheng, B. On the role of trend and variability in the hydroxyl radical (OH) in the global methane budget. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 2020, 20, 13011–13022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B. , et al. Rapid decline in carbon monoxide emissions and export from East Asia between years 2005 and 2016. Environmental Research Letters 2018, 13, 044007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Wind Speed | Barometric pressure | Relative humidity | |||

| Speed Range | Uncertainty | Range | Uncertainty | Range | Uncertainty |

| 0 - 35 m/s | ±0.3 m/s or ±3% | in 0 ... +30 °C | ±0.5 hPa | in 0 ... 90 %RH | ±3 %RH |

| 35- 60 m/s | ±5% | in -52 ... 0 °C and in +30°...+60 °C | ±1 hPa | in 90 ... 100 %RH | ±5 %RH |

| Wind DirectionUncertainty | Air temperature Uncertainty | Liquid precipitation Uncertainty | |||

| ±3 sexagesimal degrees | ±0.3 °C (±0.5 °F) | 5%* | |||

| Root Mean Square Error | BIAS | R2 | Scatter Index % | |

| CH4 | ||||

| BaDS vs SM | 46.32 | 21.27 | 0.3 | 2 |

| BaDS vs Wind | 49.96 | 20.49 | 0.14 | 3 |

| SM vs Wind | 33.08 | -0.09 | 0.12 | 2 |

| CO | ||||

| BaDS vs SM | 29.20 | 5.93 | 0.02 | 26 |

| BaDS vs Wind | 30.78 | 2.63 | 0.01 | 26 |

| SM vs Wind | 27.22 | -5.76 | 0.05 | 23 |

| CO2 | ||||

| BaDS vs SM | 8.79 | -0.77 | 0.17 | 2 |

| BaDS vs Wind | 11.66 | -3.01 | 0.05 | 3 |

| SM vs Wind | 9.89 | -3.6 | 0.17 | 2 |

| CH4 | CO | CO2 | ||||||||||||||

| Time series | n | Test S | Signif. | A | B | n | Test S | Signif. | A | B | n | Test S | Signif. | A | B | |

| DJF | 9 | 20 | * | 8.95 | 1988.49 | 9 | -24 | * | -4.85 | 189.14 | 9 | 36 | *** | 2.76 | 412.11 | |

| MAM | 9 | 24 | * | 11.16 | 1962.32 | 9 | -14 | -2.29 | 149.33 | 9 | 36 | *** | 2.74 | 414.84 | ||

| JJA | 9 | 24 | * | 15.91 | 1939.94 | 9 | 6 | 1.10 | 113.49 | 9 | 32 | *** | 3.06 | 414.17 | ||

| SON | 9 | 22 | * | 11.53 | 1991.58 | 9 | -6 | -1.33 | 132.82 | 9 | 32 | *** | 2.50 | 417.12 | ||

| ANNUAL | 9 | 24 | * | 12.49 | 1968.70 | 9 | -12 | -1.61 | 143.47 | 9 | 34 | *** | 2.84 | 413.98 | ||

| Mann-Kendall test and Sen’s slope estimate | ||||||||||||||||

| CH4 BaDS | CH4 SM | CH4 WIND | ||||||||||||||

| Time series | n | Test S | Signif. | A | B | n | Test S | Signif. | A | B | n | Test S | Signif. | A | B | |

| DJF | 9 | 34 | *** | 14.82 | 1906.31 | 9 | 36 | *** | 14.26 | 1895.69 | 9 | 36 | *** | 14.60 | 1898.77 | |

| MAM | 9 | 36 | *** | 15.59 | 1898.44 | 9 | 36 | *** | 15.01 | 1891.04 | 9 | 36 | *** | 15.19 | 1899.77 | |

| JJA | 9 | 36 | *** | 14.27 | 1882.96 | 9 | 36 | *** | 14.15 | 1880.05 | 9 | 34 | *** | 13.35 | 1882.50 | |

| SON | 9 | 32 | *** | 14.60 | 1907.22 | 9 | 36 | *** | 14.01 | 1899.11 | 9 | 32 | *** | 13.08 | 1904.18 | |

| ANNUAL | 9 | 34 | *** | 14.61 | 1898.99 | 9 | 36 | *** | 14.38 | 1892.66 | 9 | 36 | *** | 14.46 | 1897.02 | |

| Mann-Kendall test and Sen’s slope estimate | |||||||||||||||

| CO BaDS | CO SM | CO WIND | |||||||||||||

| Time series | n | Test S | Signif. | A | B | n | Test S | Signif. | A | B | n | Test S | Signif. | A | B |

| DJF | 9 | -12 | -2.13 | 143.47 | 9 | -16 | -2.22 | 129.74 | 9 | -26 | ** | -1.96 | 135.25 | ||

| MAM | 9 | -16 | -2.31 | 138.09 | 9 | -16 | -1.82 | 130.19 | 9 | -4 | -1.11 | 133.32 | |||

| JJA | 9 | 4 | 0.75 | 101.02 | 9 | 6 | 0.61 | 94.47 | 9 | 2 | 0.15 | 101.35 | |||

| SON | 9 | 8 | 0.92 | 111.79 | 9 | 2 | 0.45 | 102.11 | 9 | 4 | 0.64 | 107.22 | |||

| ANNUAL | 9 | 2 | 0.03 | 119.86 | 9 | -6 | -0.37 | 114.27 | 9 | -4 | -0.48 | 118.51 | |||

| Mann-Kendall test and Sen’s slope estimate | |||||||||||||||

| CO2 BaDS | CO2 SM | CO2 WIND | |||||||||||||

| Time series | n | Test S | Signif. | A | B | n | Test S | Signif. | A | B | n | Test S | Signif. | A | B |

| DJF | 9 | 34 | *** | 2.47 | 409.87 | 9 | 36 | *** | 2.59 | 405.81 | 9 | 36 | *** | 2.77 | 404.89 |

| MAM | 9 | 32 | *** | 2.82 | 406.14 | 9 | 34 | *** | 2.77 | 404.12 | 9 | 36 | *** | 2.55 | 406.06 |

| JJA | 9 | 34 | *** | 2.71 | 400.29 | 9 | 34 | *** | 2.62 | 399.11 | 9 | 34 | *** | 2.65 | 400.37 |

| SON | 9 | 32 | *** | 2.56 | 405.10 | 9 | 34 | *** | 2.68 | 401.41 | 9 | 32 | *** | 2.94 | 401.52 |

| ANNUAL | 9 | 34 | *** | 2.69 | 404.92 | 9 | 36 | *** | 2.75 | 402.20 | 9 | 34 | *** | 2.76 | 402.92 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).