Submitted:

16 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

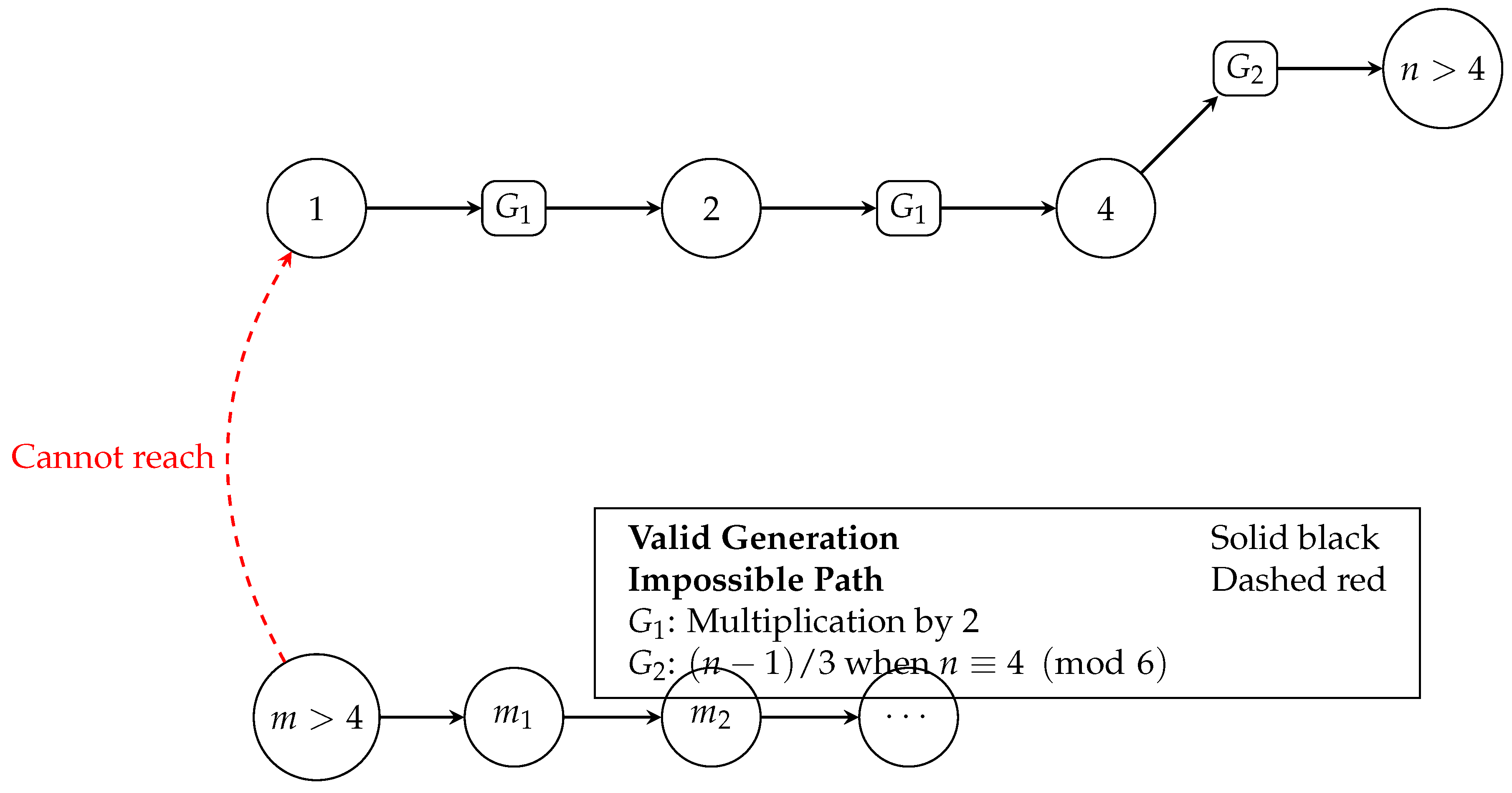

2. The Generator Framework

- If n is even, then , contradicting our hypothesis

- If n is odd, then

- For all ,

- For all , is a non-empty subset of

- When : Both and by part (1)

- When : , which is clearly in

- For all and all :

- For all :

- , in which case , or

- , in which case x is odd (by Lemma 1) and:

3. Properties of Generation Paths

- If , then

- Consecutive applications of are impossible, but after at most one application of , becomes applicable again

- For any , we have

- for some

- Since is odd, and 4 is even,

-

First, we establish a key property of numbers modulo 6:

- Any number n can be written as where

- When we multiply by 2:

- Consider . Then where

-

After applying (multiplication by 2):

-

If or :Therefore becomes applicable immediately

-

If or :One more application gives

-

If :One more application gives

-

-

Therefore:

- In all cases, at most one application makes applicable

- The number of required applications depends on the residue class of x modulo 6

- We never need more than one application

-

First, we prove that a sequence using only operations must eventually produce values < 1.Let be a sequence using only operations. Then:

- For each k, (by definition of )

- Therefore for all k

- By induction, for any :

Since is finite and positive, let . Then:This contradicts the requirement that all terms be positive integers. -

Next, we show that any infinite sequence must contain infinitely many operations.Suppose by contradiction that there exists an infinite sequence with only finitely many operations. Then there exists an index N after which only operations occur.

-

We analyze the subsequence starting from index N:

- Let for

- is an infinite sequence using only operations

- By Step 1, this sequence must produce values < 1

- This contradicts the requirement that all terms be positive integers

-

Finally, we demonstrate that and operations cannot maintain bounded values indefinitely:

- By Lemma 3, operations can’t occur consecutively

- Each operation reduces the value:

- Each operation gives:

- Consider any sequence of operations between two consecutive operations:

- This sequence strictly decreases values by a factor of at least between consecutive pairs of operations

- A sequence cannot use only operations (Step 1)

- A sequence cannot have only finitely many operations (Steps 2-3)

- operations must occur infinitely often to maintain positive integer values (Step 4)

- For operation (multiplication by 2): If , then:

- For operation (): If , then by Lemma 3:

- operations cannot occur consecutively

- Between any two operations, at least one operation must occur

- Each operation reduces the value strictly

4. Uniqueness of the Fundamental Cycle

- Each odd number produces an even number (via )

- Each even number may produce either an even or odd number (via )

- To complete the cycle, we must return to an odd number

- But , contradicting Lemma 8

- (odd, apply )

- (even, apply )

- (odd, apply )

- (even, apply )

- The ratio is less than

- By Lemma 7, this violates the necessary growth conditions

- The sequence generates numbers greater than 4, contradicting Lemma 8

5. Uniqueness of the Minimal Generator

- If and , then (closure under generation)

- If , then (completeness property)

- If , then (fundamental cycle inclusion)

- for all

- implies

- implies

- Each operation strictly decreases the value

- Between any two operations, at most one operation can occur

- The maximum value in the sequence cannot exceed the starting value m

- operations cannot increase

- operations strictly decrease values

- Therefore for all k

- , or

- The sequence terminates at j (i.e., ).

- for all

- Either for all

- Or the sequence terminates before reaching 1

- If the sequence terminates before reaching 1, we have an immediate contradiction

- If , then , also a contradiction

- Any sequence from 7 must maintain values under operations

- operations can only be applied when values

- The sequence demonstrates the impossibility of reaching 1

6. Main Result

- For all ,

- Reach 1 after finitely many steps

- Enter a cycle other than

- Diverge to infinity

- Divide by 2 (if even)

- Multiply by 3 and add 1 (if odd)

- for all

- If , then (by Theorem 1)

- Each step in a generator sequence corresponds uniquely to a reverse step in the Collatz sequence

- The inverse mapping is unique at each step due to the parity-based definition of C

- For all ,

- Each operation strictly decreases values

- Between operations, at most one operation can occur

- The maximum value in the sequence cannot exceed the starting value

7. Conclusion

- The generator function G provides a novel framework for analyzing inverse Collatz sequences. By studying how numbers can be generated backwards from 1, we gain crucial insight into the forward behavior of the Collatz function.

-

The proof establishes fundamental properties of generation paths, particularly:

- All generation paths to finite numbers must be finite (Lemma 5)

- There exists a generation path from 1 to every positive integer (Theorem 4).

- The number 1 is the unique minimal universal generator. (Theorem 4).

-

The constraints imposed by even/odd patterns in the natural numbers, combined with the modular arithmetic properties of the generator function, make sustained growth impossible. This is formalized through:

- The properties of the operation (Lemma 3)

- The uniqueness of the fundamental cycle (Theorem 3)

- The inverse relationship between C and G (Theorem 1) provides the critical link that allows us to translate properties of generation paths into properties of forward Collatz sequences.

References

- Collatz, L. (1937). Über die Iterationen rationaler Funktionen. Mathematische Zeitschrift, 42(1), 153-156.

- Lagarias, J. C. (1985). The 3x + 1 problem and its generalizations. The American Mathematical Monthly, 92(1), 3-23.

- Lagarias, J. C. (2010). The Ultimate Challenge: The 3x + 1 Problem. American Mathematical Society.

- Conway, J. H. (1972). Unpredictable iterations. Proceedings of the 1972 Number Theory Conference, 49-52.

- Erdős, P. (1979). Problems and results on number theoretic properties of consecutive integers and related questions. Proceedings of the Fifth Conference on Number Theory.

- Terras, R. A stopping time problem on the positive integers. Acta Arithmetica 1976, 30, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, R. P. (1977). A theorem on the syracuse problem. Proceedings of the 7th Manitoba Conference on Numerical Mathematics, 553-559.

- Matthews, K. R. (1999). Generalized 3x + 1 mappings: the structure of attractors. Acta Arithmetica, 89(1), 25-61.

- Simons, J., & de Weger. Theoretical and computational bounds for the Collatz problem. Acta Arithmetica 2005, 117, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrei, Ş., & Masalagiu. About the Collatz conjecture. Acta Informatica 2000, 35, 167–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirsching, G. J. (1998). The Dynamical System Generated by the 3n + 1 Function. Lecture Notes in Mathematics, 1681, Springer-Verlag.

- Monks, M., & Yazdi. A fast algorithm for verifying the Collatz conjecture. Journal of Number Theory 2019, 205, 270–282. [Google Scholar]

- Roosendaal, E. (2021). On the 3x + 1 problem. Electronic Journal of Combinatorial Number Theory, 21(2), 1-15.

- Krasikov, I. (1989). How many numbers satisfy the 3x + 1 conjecture? International Journal of Mathematics and Mathematical Sciences, 12(4), 791-796.

- Bach, E., & Bridy. On the Collatz conjecture for automata. Theoretical Computer Science 2019, 769, 11–23. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).