Submitted:

17 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

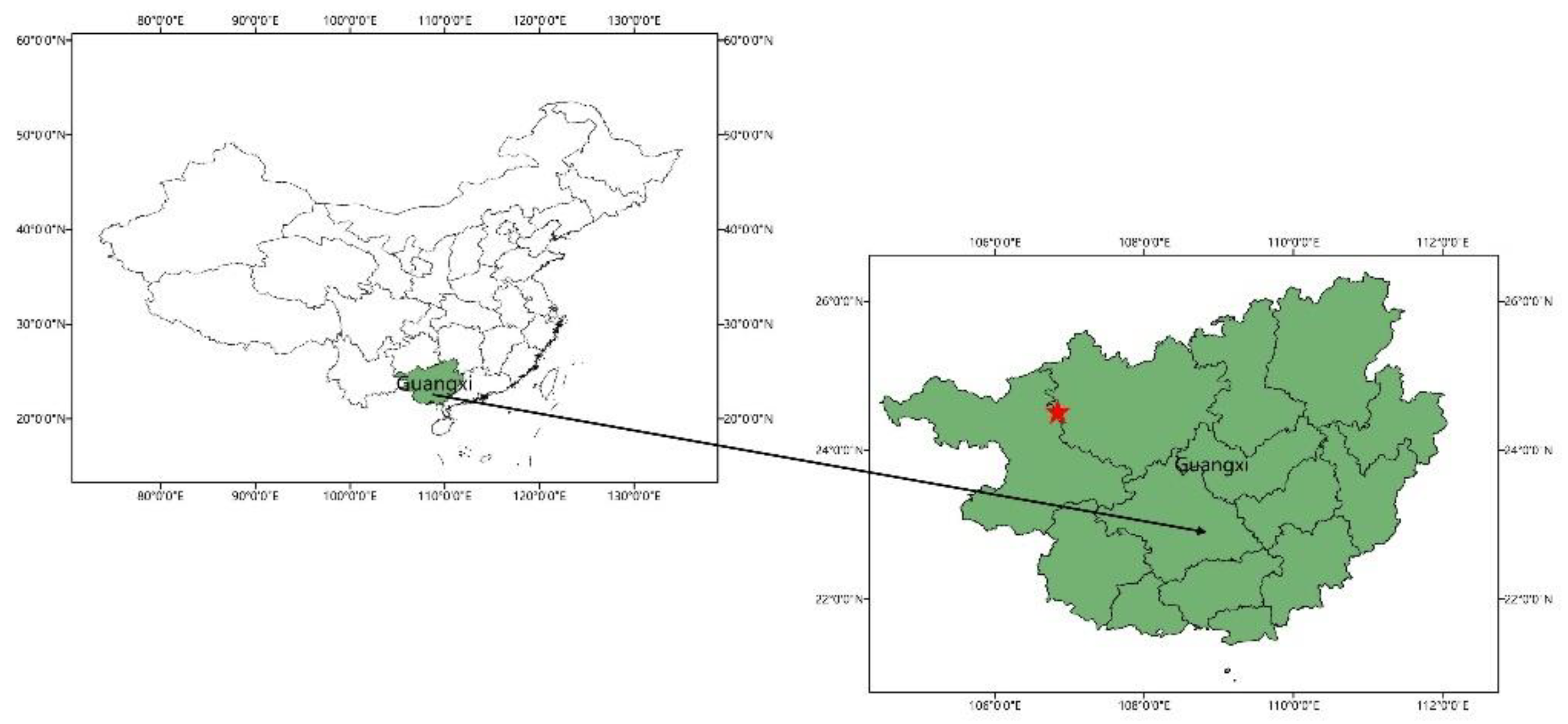

2.1. Introduction of the Research Region

2.2. Materials

2.3. Experimental Design

2.4. Test Methods

2.5. Data Processing

3. Results

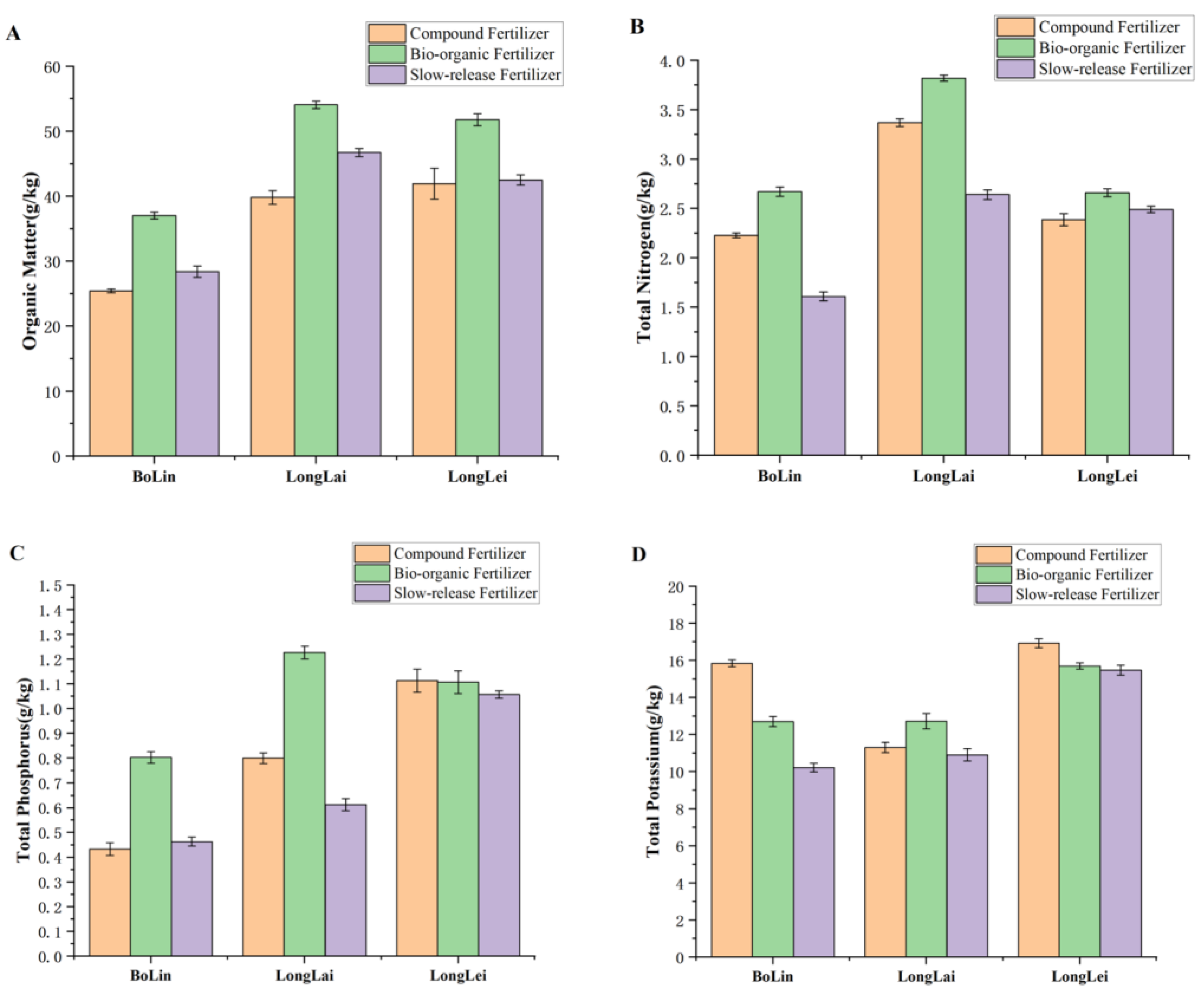

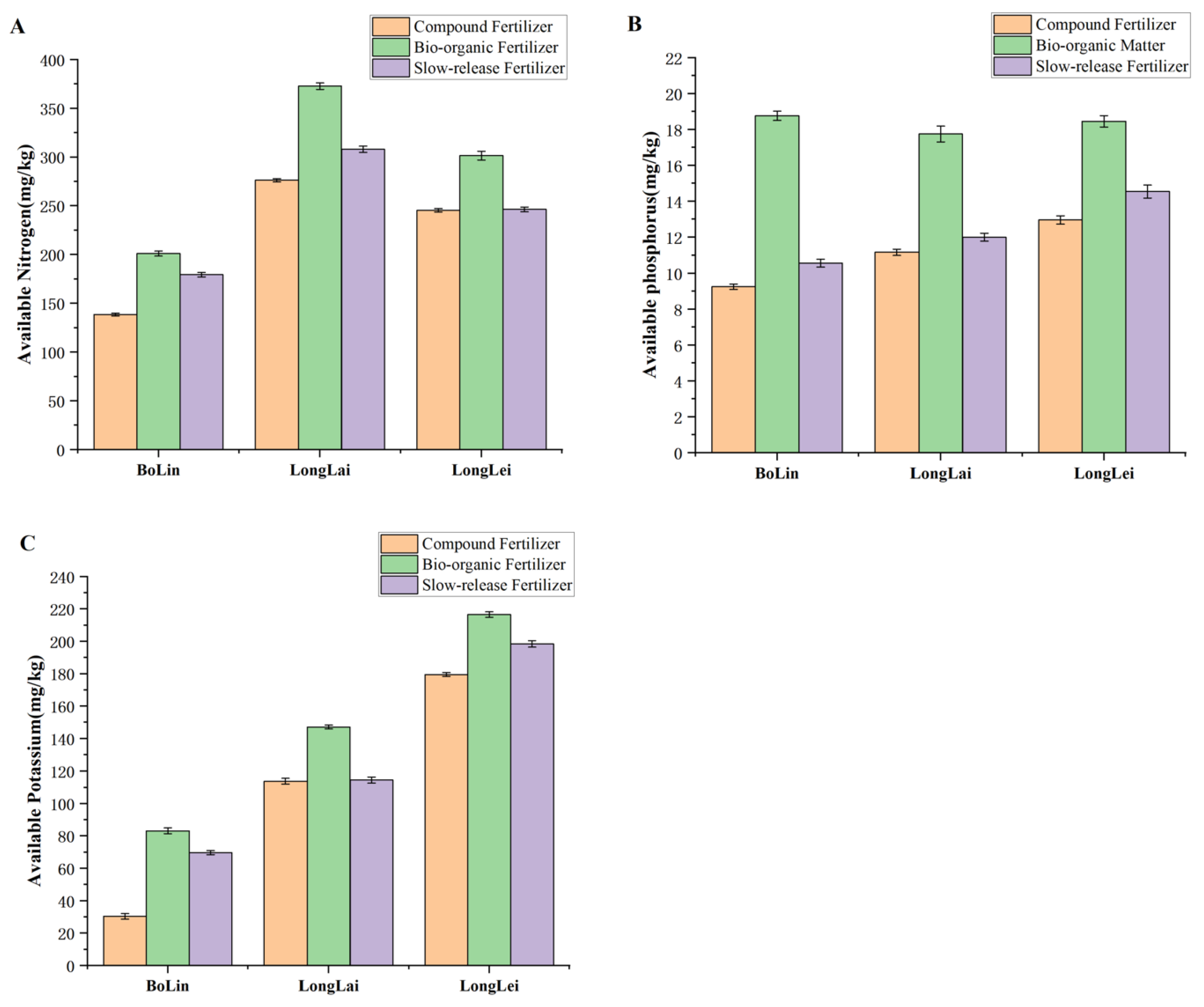

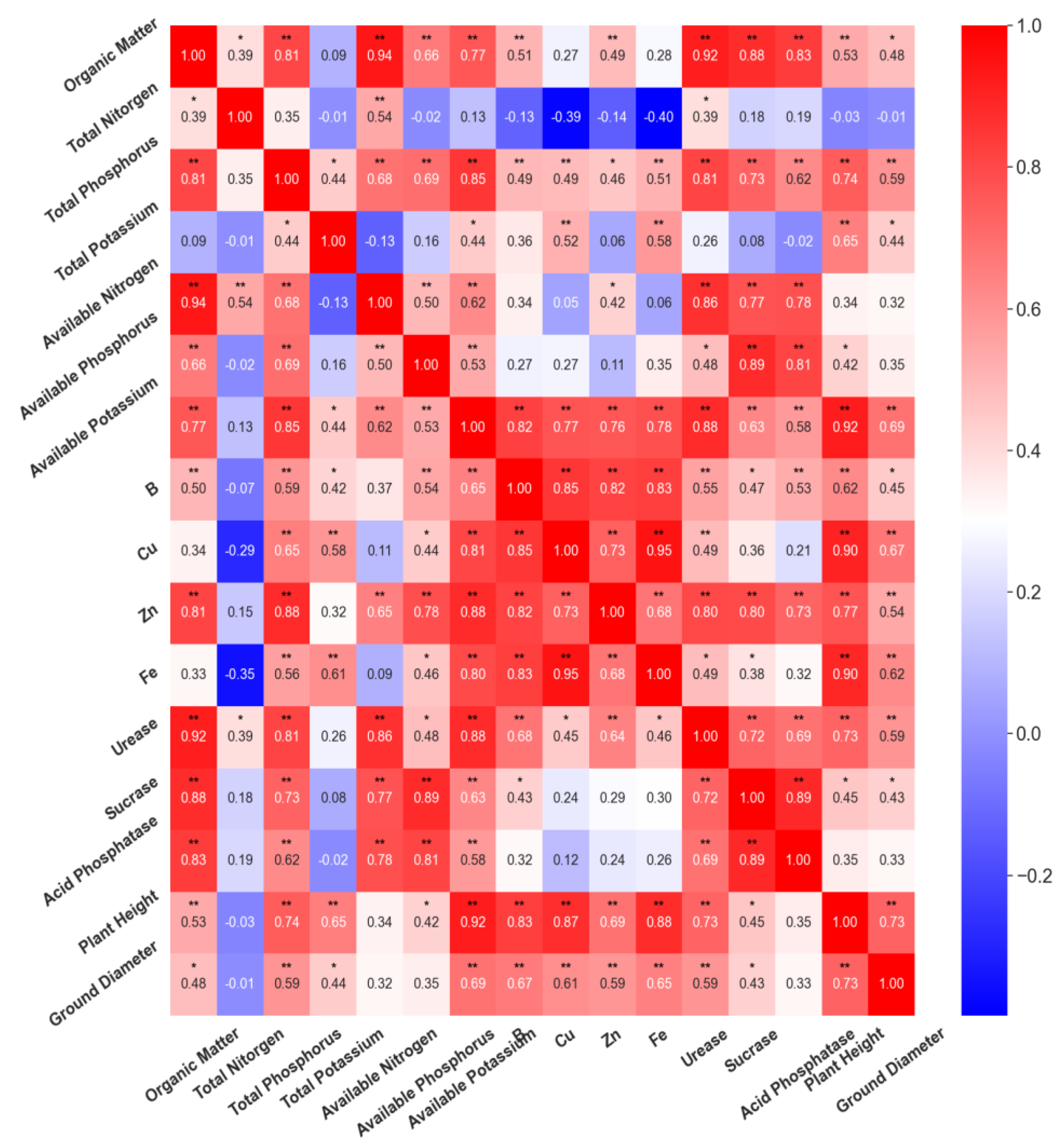

3.1. Effect of Different Fertilizer Applications on Soil Organic Matter and Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium Content of Soil

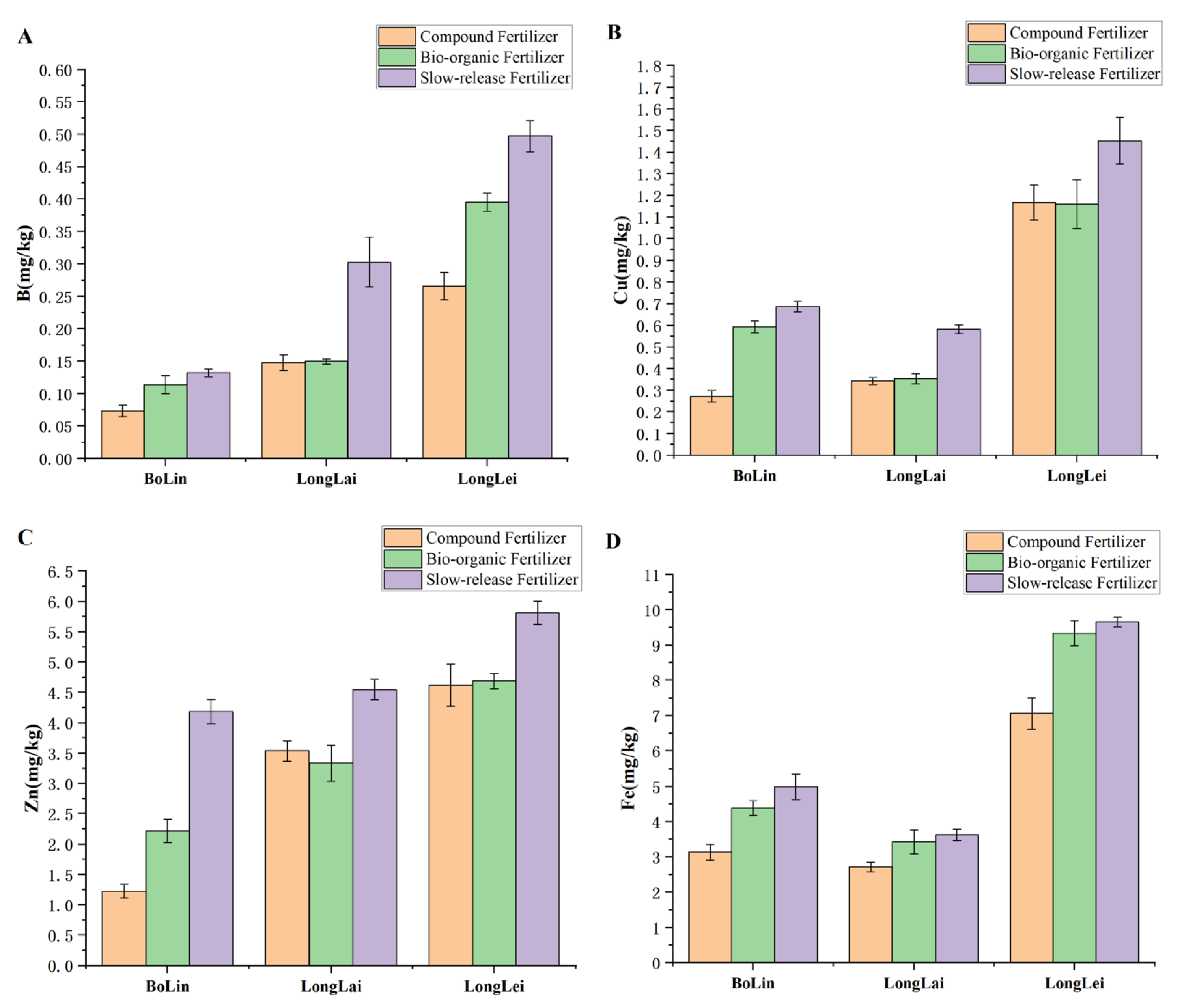

3.2. Effect of Different Fertilizer Applications on Soil Micronutrient Content

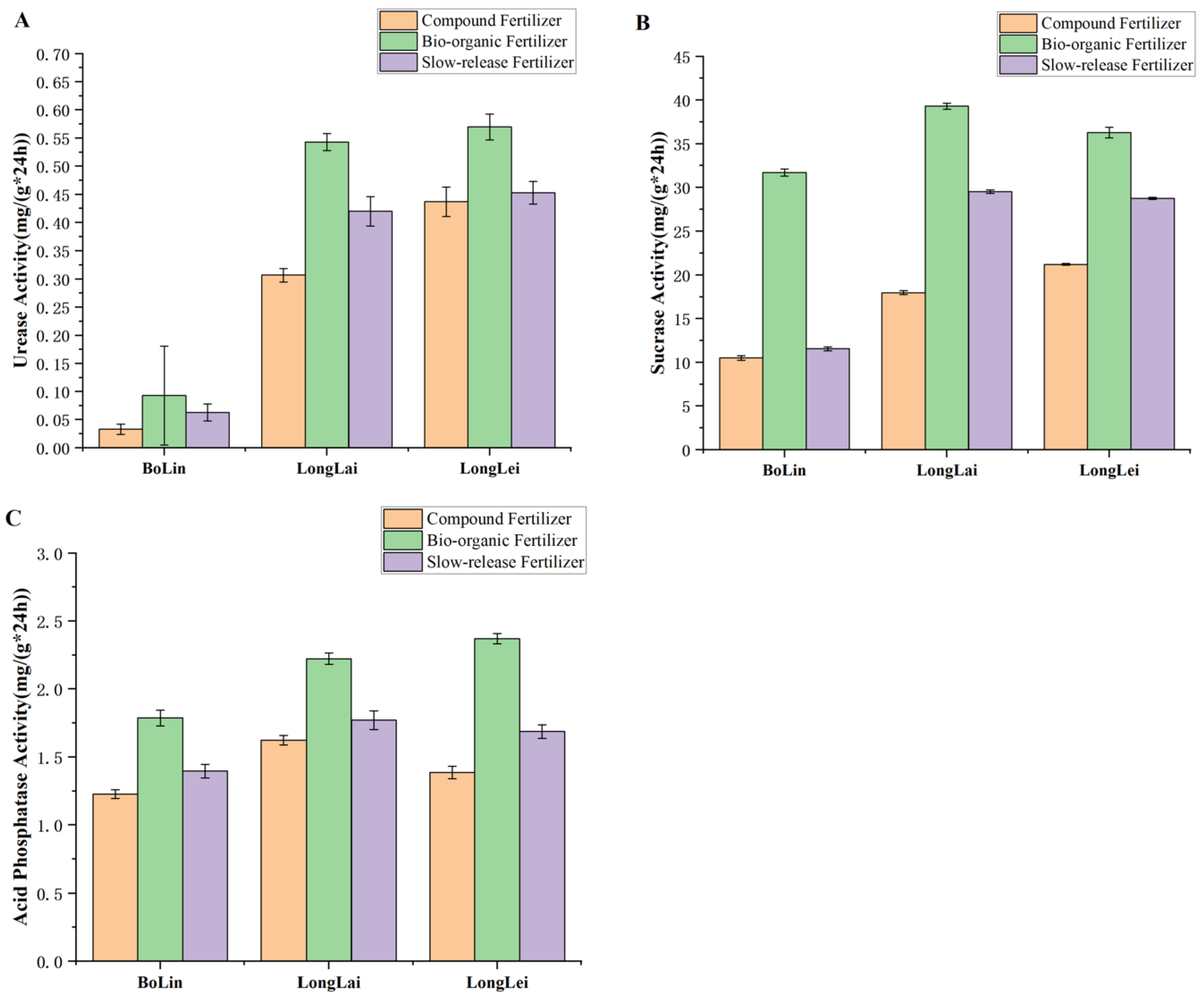

3.3. Effect of Different Fertilizer Applications on Soil Enzyme Activities

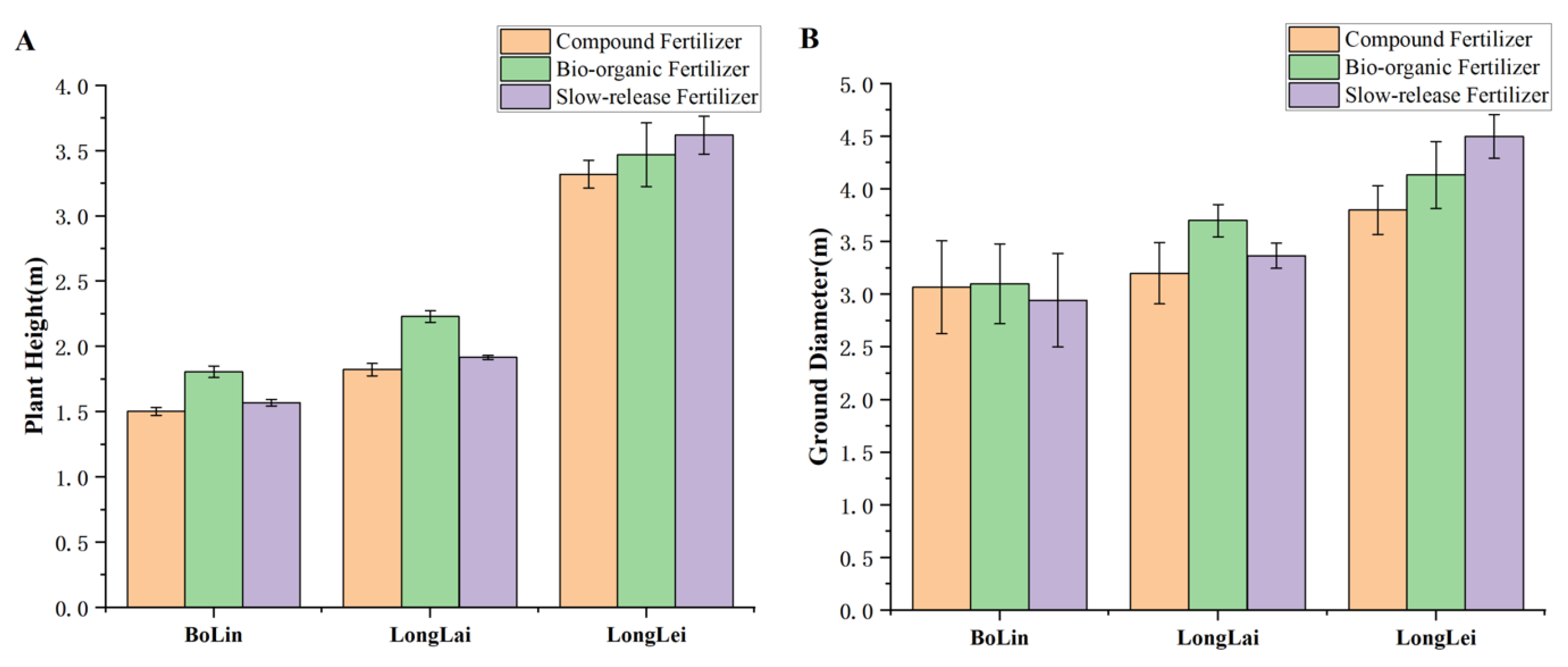

3.4. Effects of Different Fertilizer Applications on the Growth of Mahonia fortunei (Lindl.) Fedde

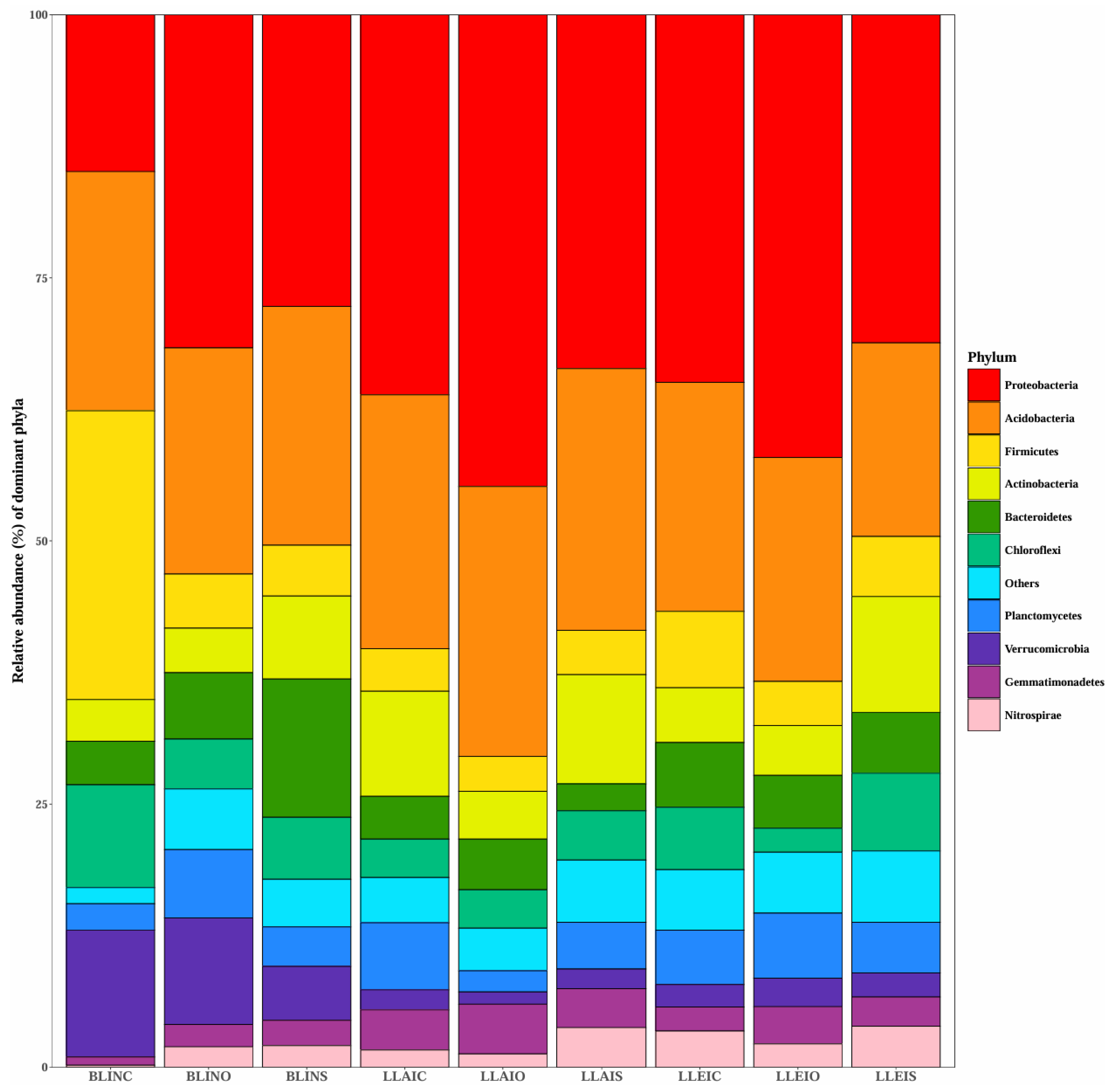

3.5. Effect of Different Fertilizer Applications on the Soil Bacterial Communities in Different Regions

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Application of Different Fertilizers on Soil Fertility in Different Regions

4.2. Effect of Application of Different Fertilizers on Soil Micronutrient Content in Different Regions

4.3. Effect of Application of Different Fertilizers on Soil Enzyme Activities in Different Regions

4.4. Effects of Applying Different Fertilizers on the Abundance, Diversity, and Structure of Soil Bacteria in Different Regions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yuan, L.; Liu, W.D.; Su, S.; Chen, Z. The rocky desertification management in Guizhou province under the localized governance system. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10, 1065663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.J.; Liu, Q.M.; Zhang, D.F. Karst rocky desertification in southwestern China: Geomorphology, landuse, impact and rehabilitation. Land Degradation & Development 2004, 15, 115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.Y.; Wang, S.J.; Xiong, K.N. Assessing spatial-temporal evolution processes of kaest rocky desertification land: indications for restoration strategies. Land Degradation & Development 2013, 24, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, W.B.; Yan, Y.J.; Wang, K.; Hu, G.; Ling, Z.H. Effects of control measures on soil quality evolution in the Karst rocky desertification area in southwestern China. Research of Soil and Water 2021, 28, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Madsen, L.M. The Danish afforestation programme and spatial planning: new challenges. Landscape and Urban Planning 2002, 58, 241–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.F.; Zhu, S.Q.; Ye, J.Z.; Wei, L.M.; Cheng, Z.R. Dynamics of a degraded karst forest in the process of natural restoration. Scientia Silvae Sinicae 2002, 38, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.; Xu, Y.Q.; Zhang, R.; Xiong, K.N.; Lan, A.J. Soil erosion monitoring and its implication in a limestone land suffering from rocky desertification in the Huajiang Canyon, Guizhou, Southwest China. Environmental Earth Sciences 2013, 69, 831–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.H.; Cai, Y.L.; Xing, X.S. Rocky desertification, antidesertification, and sustainable development in the karst mountain region of Southwest China. Ambio 2008, 37, 390–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.L. The origin, development and propspect of non-timber forest-based economics. Journal of Nanjing Forestry University (Natural Science Edition) 2022, 46, 105–114. [Google Scholar]

- Somarriba, E. Revisiting the past-an essay on agroforestry definition. Agroforestry Systems 1992, 19, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, J.Q.; Gao, L.; Liu, F.Y.; Liu, Y.J. Effects of different management measures of cultivation Panax notoginseng under forest on runoff and sediment yield and soil characteristics on slope. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 2024, 38, 20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.Q. The interplanting patterns of economic crops with young Chinese firplantations. Journal of Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University ( Natural Science Edition) 2005, 34, 34–238. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.S. Research and demonstration of planting grain crops under forest. Agricultural Engineering 2020, 10, 112–119. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, T.S.; Deng, X.W.; Chen, L.; Xiang, W.H. The soil properties and their effects on plant diversity in different degrees of rocky desertification. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 736, 139667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, C.Y.; Ma, W.R.; Qiang, B.B.; Jin, X.J.; Zhang, Y.X.; Wang, M.X. Effect of chemical fertilizer with compound microbial fertilizer on soil physical properties and soybean yield. Agronomy-Basel 2023, 13, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimkpa, C.; Adzawla, W.; Pandey, R.; Atakora, W.K.; Kouame, A.K.; Jemo, M.; Bindraban, P.S. Fertilizers for food and nutrition security in sub-Saharan Africa: An overview of soil health implications. Frontiers in Soil Science 2023, 3, 1123931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomiero, T. Soil degradation, land scarcity and food security: reviewing a complex challenge. Sustainability 2016, 8, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.A.; Khan, K.S.; Khalid, R.; Shabaan, M.; Alghamdi, A.G.; Alasmary, Z.; Majrashi, M.A. Integrated application of biochar and chemical fertilizers improves wheat (Triticum aestivum) productivity by enhancing soil microbial activities. Plant and Soil 2024, 502, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldfield, E.E.; Bradford, M.A.; Wood, S.A. Global meta-analysis of the relationship between soil organic matter and crop yields. Soil 2019, 5, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, P.; Abler, D.; Lin, G.; Sher, A.; Quan, Q. Substituting Organic Fertilizer for Chemical Fertilizer: Evidence from Apple Growers in China. Land 2021, 10, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, B.L.; Liu, M.Z.; Lü, S.Y.; Xie, L.H.; Wang, Y.F. Multifunctional Slow-Release Organic-Inorganic Compound Fertilizer. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2010, 58, 12373–12378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Mi, W.H.; Su, L.J.; Shan, Y.Y.; Wu, L.H. Controlled-release fertilizer enhances rice grain yield and N recovery efficiency in continuous non-flooding plastic film mulching cultivation system. Field Crops Research 2019, 231, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.J.; Fan, J.L.; Zhang, F.C.; Yan, S.C.; Zheng, J.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.L.; Sun, X.; Liu, X.Q.; et al. Blending urea and slow-release nitrogen fertilizer increases dryland maize yield and nitrogen use efficiency while mitigating ammonia volatilization. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 790, 148058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahrl, F.; Li, Y.J.; Su, Y.F.; Tennigkeit, T.; Wilkes, A.; Xu, J.C. Greenhouse gas emissions from nitrogen fertilizer use in China. Environmental Science & Policy 2010, 13, 688–694. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, N.; Jin, L.; Wang, S.Y.; Li, J.W.; Liu, F.H.; Liu, Z.C.; Luo, S.L.; Wu, Y.; Lyu, J.; Yu, J.H. Reduced chemical fertilizer combined with bio-organic fertilizer affects the soil microbial community and yield and quality of lettuce. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 863325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijen, M.G.A. The unseen majority: Soil microbes as drivers of plant diversity and productivity in terrestrial ecosystems (vol 11, pg 296, 2008). Ecology Letters 2008, 11, 651–651. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Cui, S.; Wu, L.; Qi, W.; Chen, J.; Ye, Z.; Ma, J.; Liu, D. Effects of bio-organic fertilizer on soil fertility, yield, and quality of tea. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2023, 23, 5109–5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naher, U.A.; Biswas, J.C.; Maniruzzaman, M.; Khan, F.H.; Sarkar, M.I.U.; Jahan, A.; Hera, M.H.R.; Hossain, M.B.; Islam, A.; Islam, M.R. Bio-organic fertilizer: a green technology to reduce synthetic N and P fertilizer for rice production. Frontiers in Plant Science 2021, 12, 602052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cai, Z.S.; Pei, J.B.; Wang, M.M.; Wang, S.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.W. The Effects of the Long-Term Application of Different Nitrogen Fertilizers on Brown Earth Fertility Indices and Fungal Communities. Soil Systems 2024, 8, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.X.; Li, H.H.; Liu, Q.L.; Ye, C.Y.; Yu, F.X. Application of bio-organic fertilizer, not biochar, in degraded red soil improves soil nutrients and plant growth. Rhizosphere 2020, 16, 100264. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.Y.; Zhang, H.Y.; Liang, X.Y.; Fu, R.; Li, M.; Chen, C.J. Effect of different biochar particle sizes together with bio-organic fertilizer on rhizosphere soil microecological environment on saline-alkali land. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2022, 10, 949190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.K.; Ghosh, G.K. Developing biochar-based slow-release N-P-K fertilizer for controlled nutrient release and its impact on soil health and yield. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2023, 13, 13051–13063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Clercq, T.; Merckx, R.; Elsen, A.; Vandendriessche, H. Impact of long-term compost amendments on soil fertility, soil organic matter fractions and nitrogen mineralization. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Symposium on Organic Matter Management and Compost Use in Horticulture, Murcia, SPAIN, 20-24 Apr 2015; pp. 79–86. [Google Scholar]

- Johannes, A.; Sauzet, O.; Matter, A.; Boivin, P. Soil organic carbon content and soil structure quality of clayey cropland soils: A large-scale study in the Swiss Jura region. Soil Use and Management 2023, 39, 707–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, D.W. The role of soil organic matter in maintaining soil quality in continuous cropping systems. Soil & Tillage Research 1997, 43, 131–167. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, E.G.; O'Sullivan, C.A.; Roper, M.M.; Palta, J.; Whisson, K.; Peoples, M.B. Yield and nitrogen use efficiency of wheat increased with root length and biomass due to nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium interactions. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 2018, 181, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassi, D.; Menossi, M.; Mattiello, L. Nitrogen supply influences photosynthesis establishment along the sugarcane leaf. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xucheng, Z.; Zhouping, S. Effect of nitrogen fertilization on photosynthetic pigment and fluorescence characteristics in leaves of winter wheat cultivars on dryland. Acta Agriculturae Nucleatae Sinica 2007, 21, 299. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Z.; Dai, Q.; Kong, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, J. Effects of the mutant with low chlorophyll content on photosynthesis and yield in rice. Acta Agronomica Sinica 2016, 42, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardi, S.; Morari, F.; Berti, A.; Tosoni, M.; Giardini, L. Soil organic matter properties after 40 years of different use of organic and mineral fertilisers. European Journal of Agronomy 2004, 21, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.B.; Cui, S.Y.; Wu, L.T.; Qi, W.L.; Chen, J.H.; Ye, Z.Q.; Ma, J.W.; Liu, D. Effects of Bio-organic Fertilizer on Soil Fertility, Yield, and Quality of Tea. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2023, 23, 5109–5121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warman, P.R.; Termeer, W.C. Evaluation of sewage sludge, septic waste and sludge compost applications to corn and forage: Ca, Mg, S, Fe, Mn, Cu, Zn and B content of crops and soils. Bioresource Technology 2005, 96, 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kot, F.S.; Farran, R.; Fujiwara, K.; Kharitonova, G.V.; Kochva, M.; Shaviv, A.; Sugo, T. On boron turnover in plant-litter-soil system. Geoderma 2016, 268, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, J.; Miwa, K.; Fujiwara, T. Boron transport mechanisms: collaboration of channels and transporters. Trends in Plant Science 2008, 13, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhead, J.L.; Reynolds, K.A.G.; Abdel-Ghany, S.E.; Cohu, C.M.; Pilon, M. Copper homeostasis. New Phytologist 2009, 182, 799–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravet, K.; Pilon, M. Copper and Iron Homeostasis in Plants: The Challenges of Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2013, 19, 919–932. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair, S.A.; Krämer, U. The zinc homeostasis network of land plants. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Molecular Cell Research 2012, 1823, 1553–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmgren, M.G.; Clemens, S.; Williams, L.E.; Kraemer, U.; Borg, S.; Schjorring, J.K.; Sanders, D. Zinc biofortification of cereals: problems and solutions. Trends in Plant Science 2008, 13, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kim, S.A.; Lee, J.; Guerinot, M.L.; An, G. Zinc deficiency-inducible OsZIP8 encodes a plasma membrane-localized zinc transporter in rice. Molecules and Cells 2010, 29, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, F.; Abbas, S.; Waseem, F.; Ali, N.; Mahmood, R.; Bibi, S.; Deng, L.F.; Wang, R.F.; Zhong, Y.T.; Li, X.X. Phosphorus (P) and Zinc (Zn) nutrition constraints: A perspective of linking soil application with plant regulations. Environmental and Experimental Botany 2024, 226, 105875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G. Iron uptake, signaling, and sensing in plants. Plant Communications 2022, 3, 100349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finazzi, G.; Petroutsos, D.; Tomizioli, M.; Flori, S.; Sautron, E.; Villanova, V.; Rolland, N.; Seigneurin-Berny, D. Ions channels/transporters and chloroplast regulation. Cell Calcium 2015, 58, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Wang, Y.S. Soil enzyme activities with greenhouse subsurface irrigation. Pedosphere 2006, 16, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demisie, W.; Liu, Z.Y.; Zhang, M.K. Effect of biochar on carbon fractions and enzyme activity of red soil. Catena 2014, 121, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.P.; Ma, H.; Zhao, Q.L.; Zhang, S.R.; Wei, W.L.; Ding, X.D. Changes in soil bacterial community and enzyme activity under five years straw returning in paddy soil. European Journal of Soil Biology 2020, 100, 103215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Tian, J.; Fang, H.J.; Gao, Y.; Xu, M.G.; Lou, Y.L.; Zhou, B.K.; Kuzyakov, Y. Functional soil organic matter fractions, microbial community, and enzyme activities in a Mollisol under 35 years manure and mineral fertilization. Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition 2019, 19, 430–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardgett, R.D.; van der Putten, W.H. Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nature 2014, 515, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousk, J.; Brookes, P.C.; Bååth, E. Contrasting Soil pH Effects on Fungal and Bacterial Growth Suggest Functional Redundancy in Carbon Mineralization. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2009, 75, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Si, L.L.; Zhang, X.; Cao, K.; Wang, J.H. Various green manure-fertilizer combinations affect the soil microbial community and function in immature red soil. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14, 1255056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, K.S.; Lauber, C.L.; Knight, R.; Bradford, M.A.; Fierer, N. Consistent effects of nitrogen fertilization on soil bacterial communities in contrasting systems. Ecology 2010, 91, 3463–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coolon, J.D.; Jones, K.L.; Todd, T.C.; Blair, J.M.; Herman, M.A. Long-term nitrogen amendment alters the diversity and assemblage of soil bacterial communities in tallgrass prairie. Plos One 2013, 8, e67884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.Y.; Deng, S.P.; Raun, W.R. Bacterial community structure and diversity in a century-old manure-treated agroecosystem. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2004, 70, 5868–5874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GuangHua, W.; JunJie, L.I.U.; XiaoNing, Q.I.; Jian, J.I.N.; Yang, W.; XiaoBing, L.I.U. Effects of fertilization on bacterial community structure and function in a black soil of Dehui region estimated by Biolog and PCR-DGGE methods. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2008, 28, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, V.; Rehman, A.; Mishra, A.; Chauhan, P.S.; Nautiyal, C.S. Changes in bacterial community structure of agricultural land due to long-term organic and chemical amendments. Microbial Ecology 2012, 64, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, J.H.; Song, J.; Kim, B.Y.; Kim, M.S.; Joa, J.H.; Weon, H.Y. Characterization of the Bacterial and Archaeal Communities in Rice Field Soils Subjected to Long-Term Fertilization Practices. Journal of Microbiology 2012, 50, 754–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spain, A.M.; Krumholz, L.R.; Elshahed, M.S. Abundance, composition, diversity and novelty of soil Proteobacteria. Isme Journal 2009, 3, 992–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, J.J.; Liu, W.B.; Zhu, C.; Luo, G.W.; Kong, Y.L.; Ling, N.; Wang, M.; Dai, J.Y.; Shen, Q.R.; Guo, S.W. Bacterial rather than fungal community composition is associated with microbial activities and nutrient-use efficiencies in a paddy soil with short-term organic amendments. Plant and Soil 2018, 424, 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, T.H.; Xie, J.M.; Li, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, X.D.; Ma, H.Y.; Wang, C. Response of rhizosphere microbial community of Chinese chives under different fertilization treatments. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13, 1031624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | Chao1 | ACE | Shannon | Simpson |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BLINC | 2479.75±98.46e | 2903.83±184.02e | 6.97±0.19bc | 0.9952±0.0022b |

| BLINO | 6242.78±551.51b | 7681.87±733.17b | 7.32±0.10ab | 0.9982±0.0003ab |

| BLINS | 2714.07±357.17e | 3227.64±348.53de | 7.11±0.16a | 0.9984±0.0005ab |

| LLAIC | 4836.93±220.27c | 5270.23±253.01c | 7.00±6.86bc | 0.9974±0.0002a |

| LLAIO | 12054.50±740.03a | 14476.99±1075.97a | 7.43±0.02a | 0.9987±0.0001a |

| LLAIS | 6276.02±66.94b | 7220.52±25.25b | 7.31±0.01ab | 0.9982±0.0003ab |

| LLEIC | 3363.22±439.94de | 4007.23±597.46cde | 7.21±0.14abc | 0.9977±0.0007ab |

| LLEIO | 6126.36±140.22b | 7054.35±158.76b | 7.26±0.03abc | 0.9968±0.0004ab |

| LLEIS | 4034.46±225.71cd | 4629.97±328.63cd | 6.91±0.13c | 0.9962±0.0013ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).