Submitted:

15 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1.

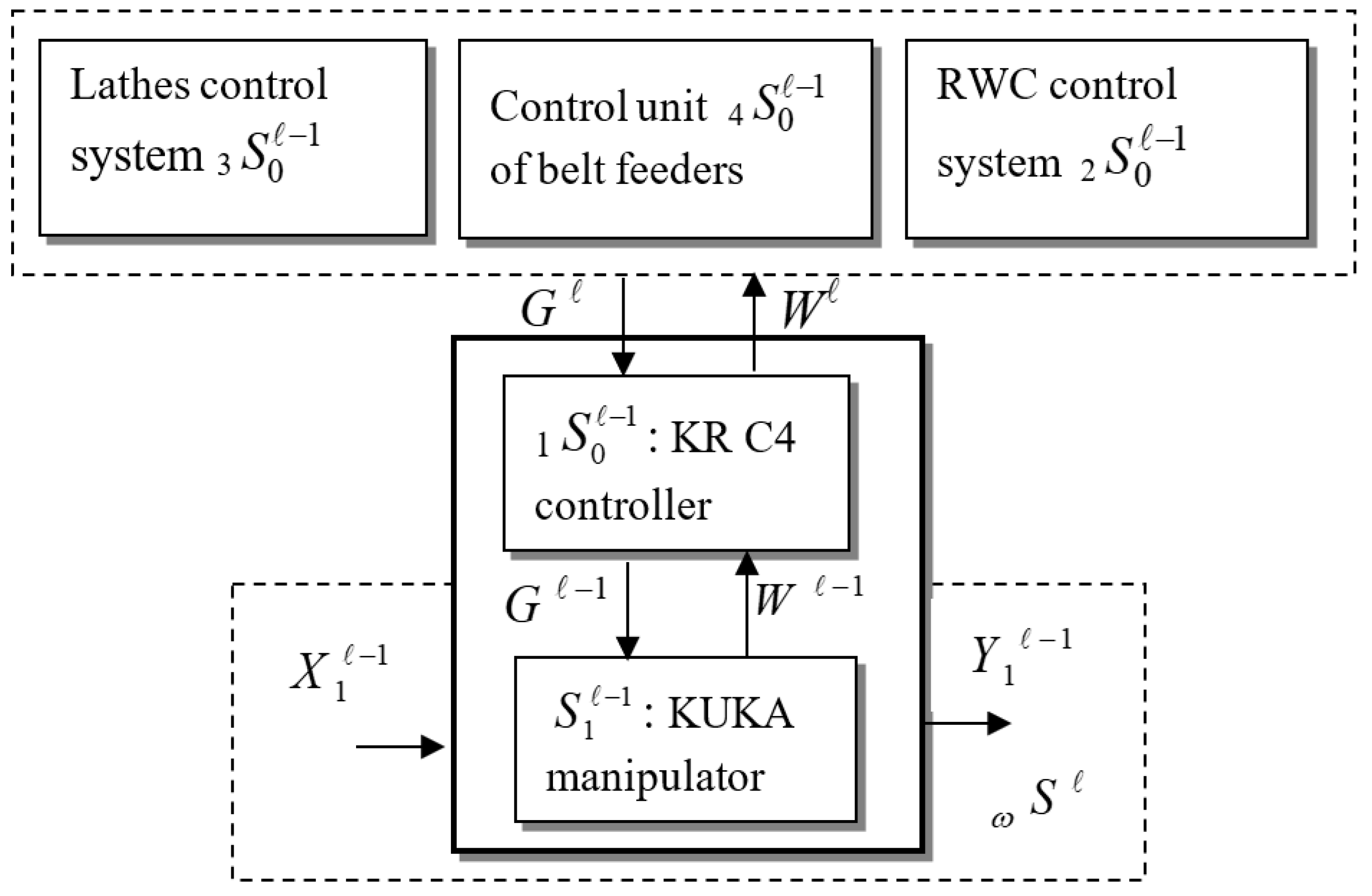

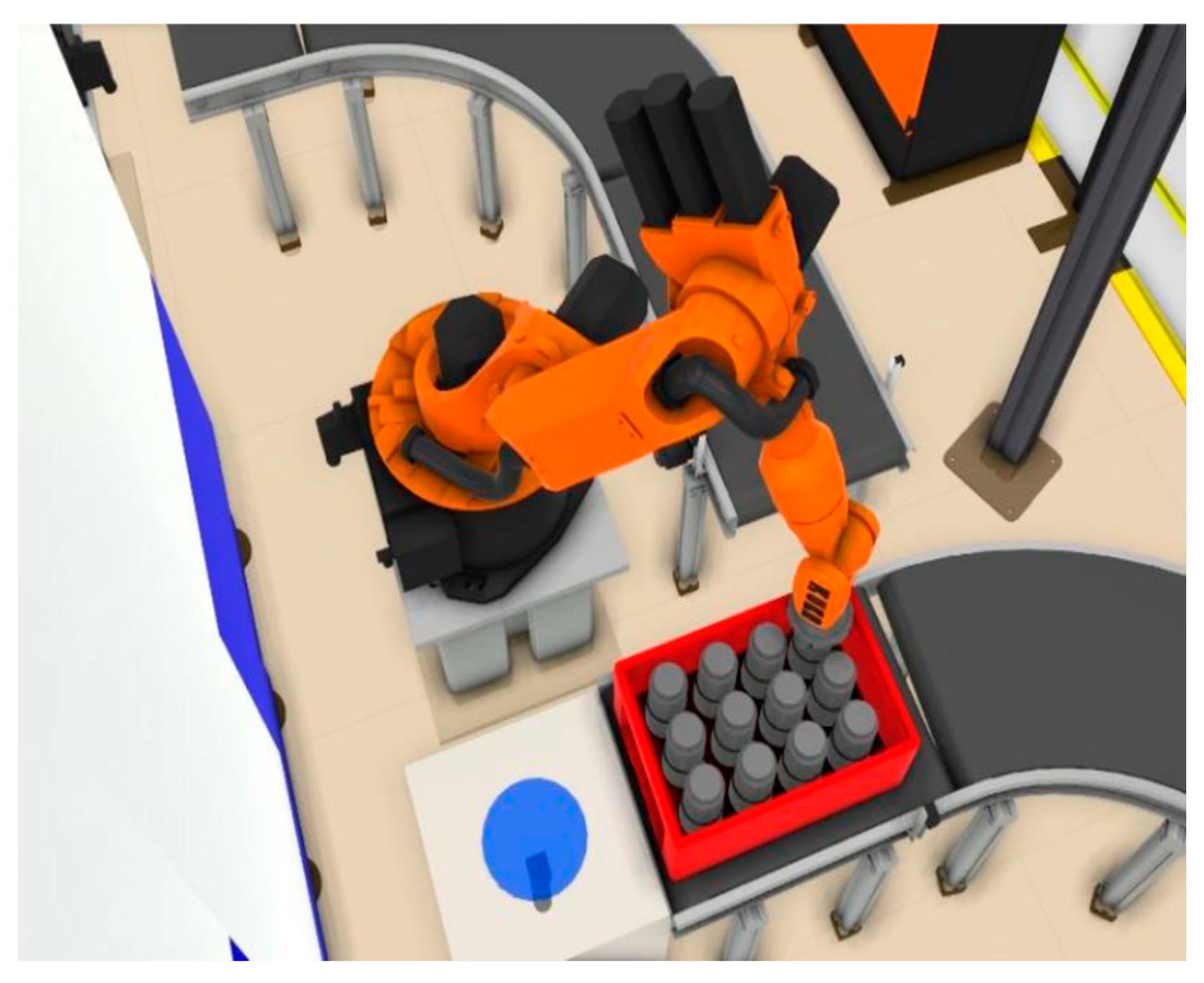

2.1.1. Robotic Work Cell Conceptual Model

2.1.2. RWC Coordinator Control Processes

2.2. Development of a Digital Model of Robotic Work Cell

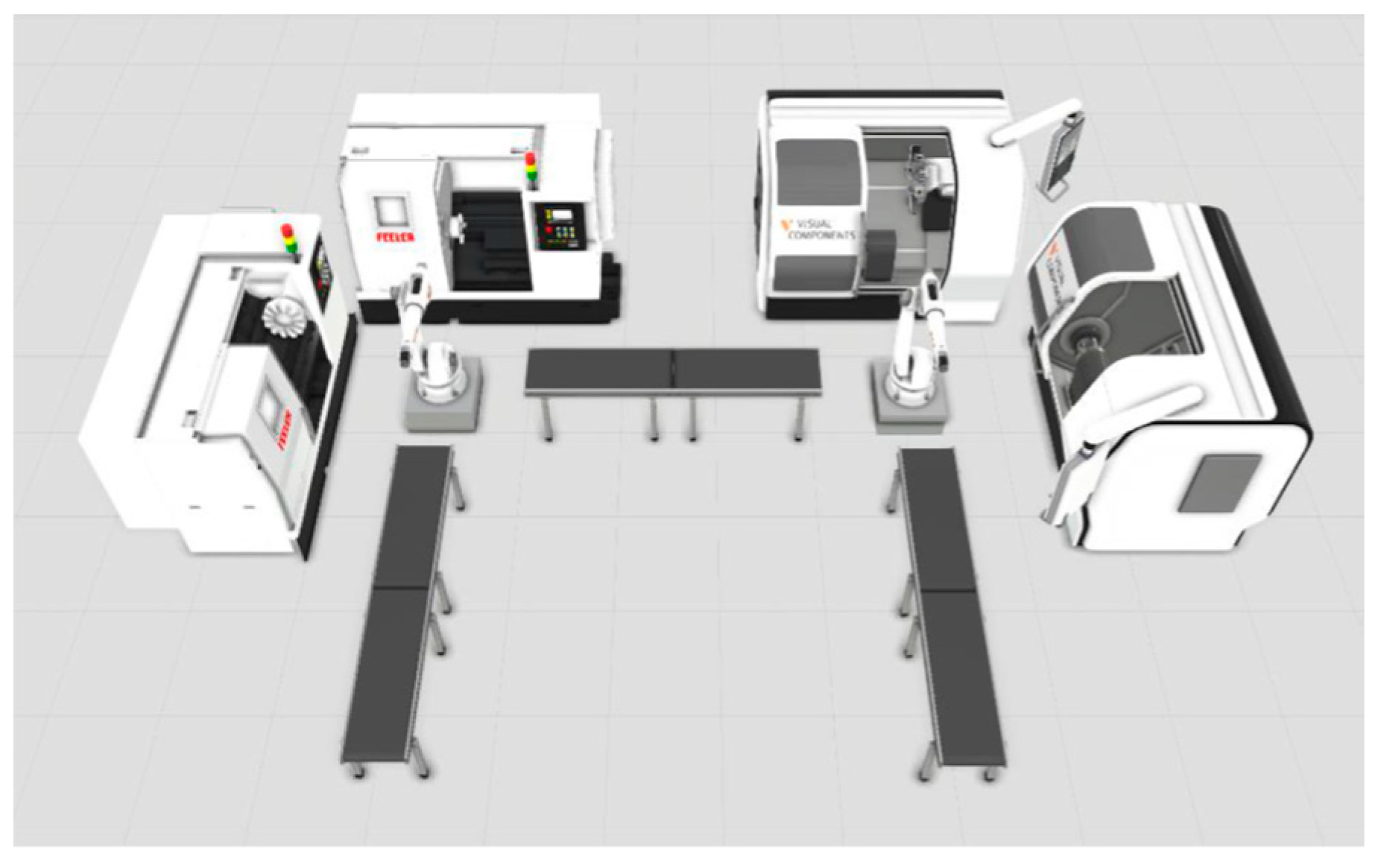

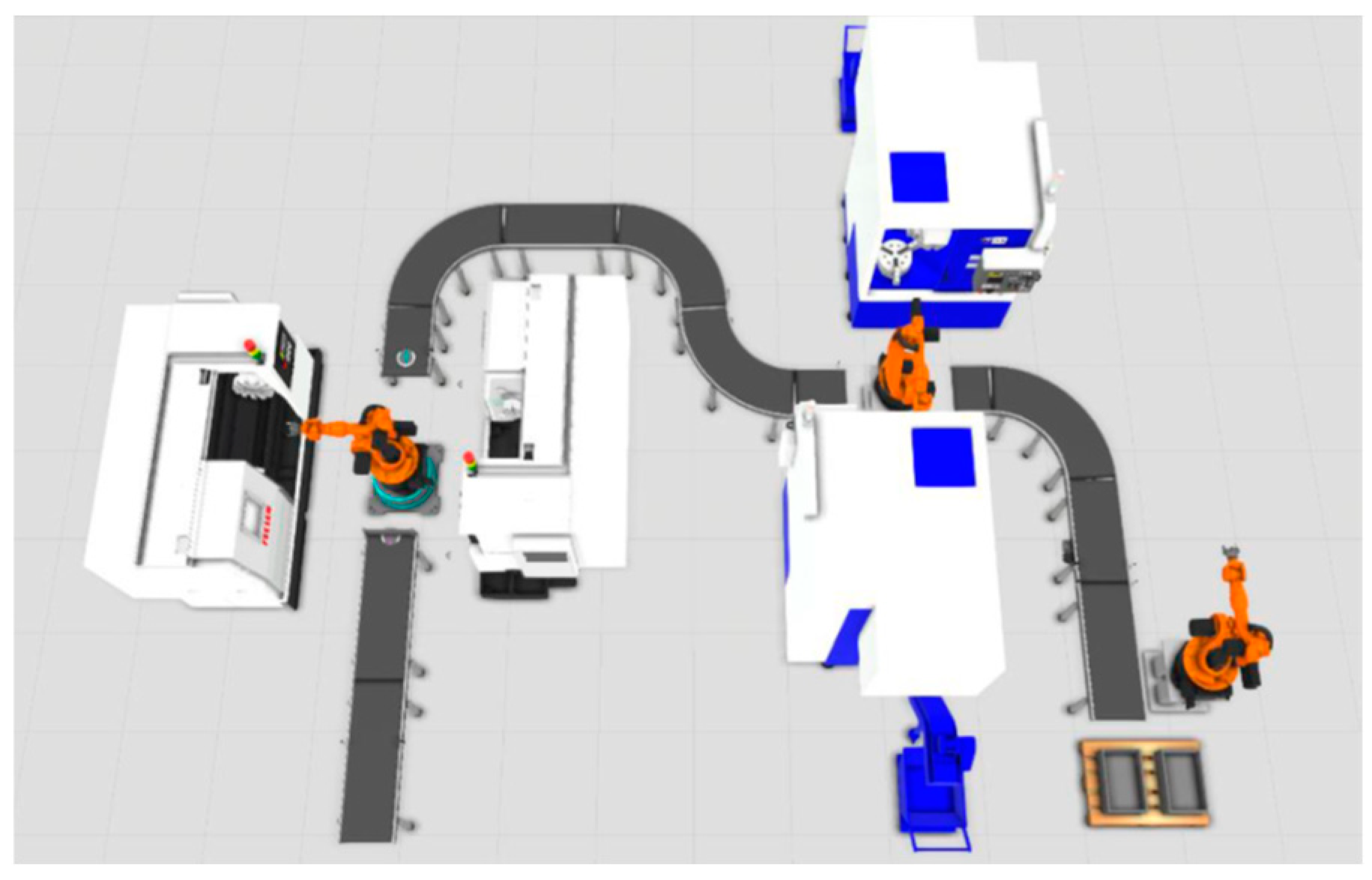

2.2.1. Creation of the RWC Prototypes

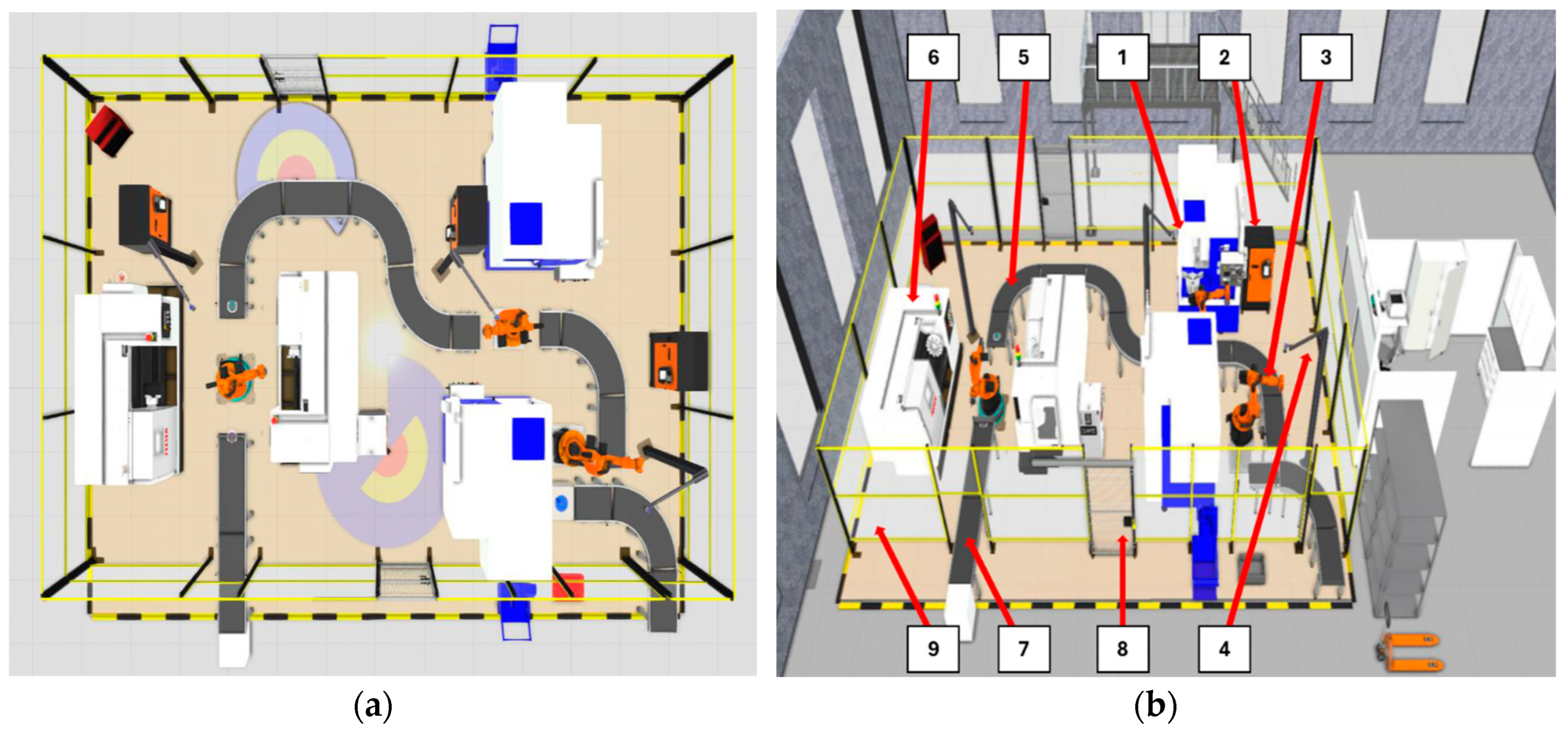

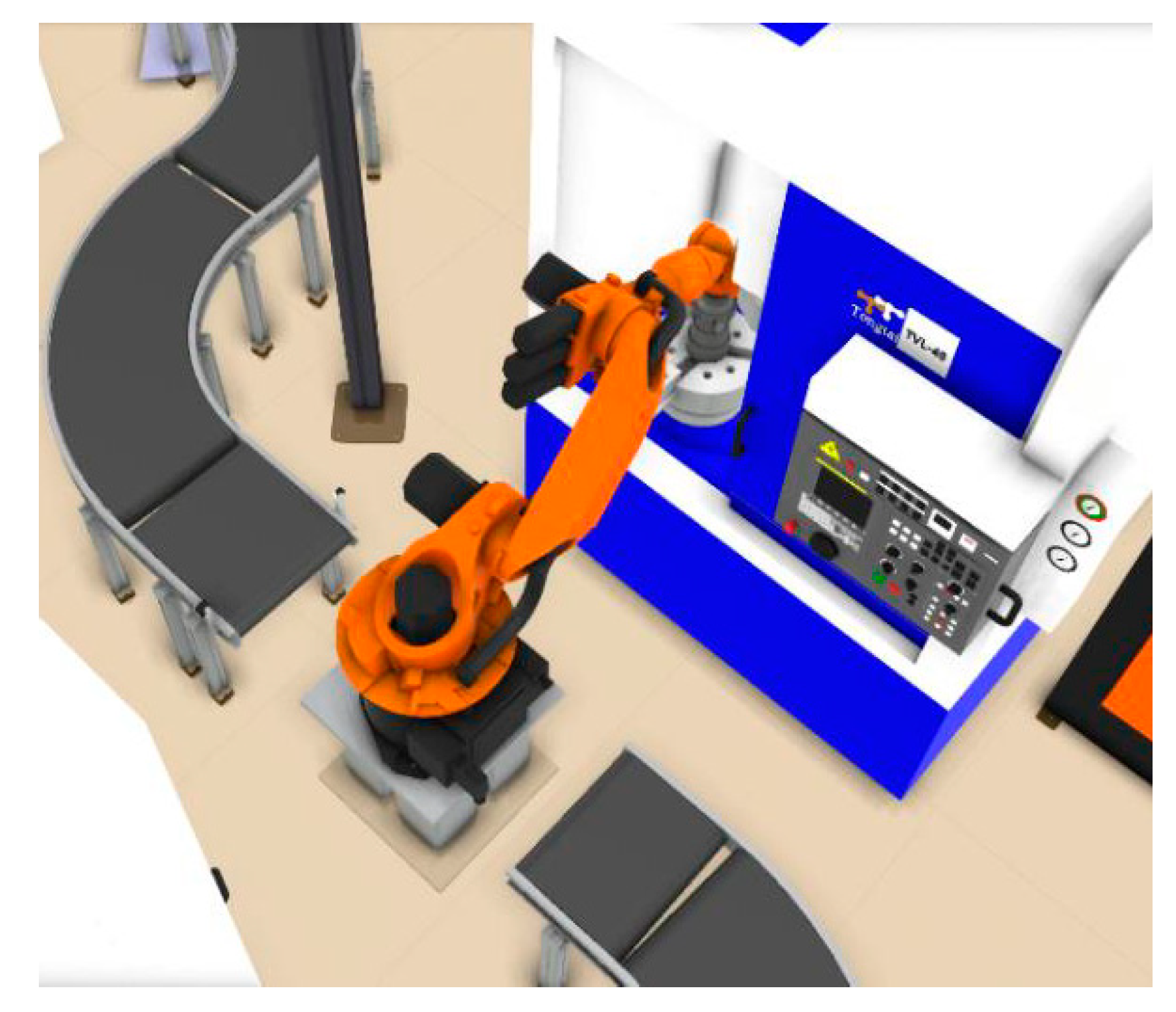

2.2.2. Resultant Work Cell Design

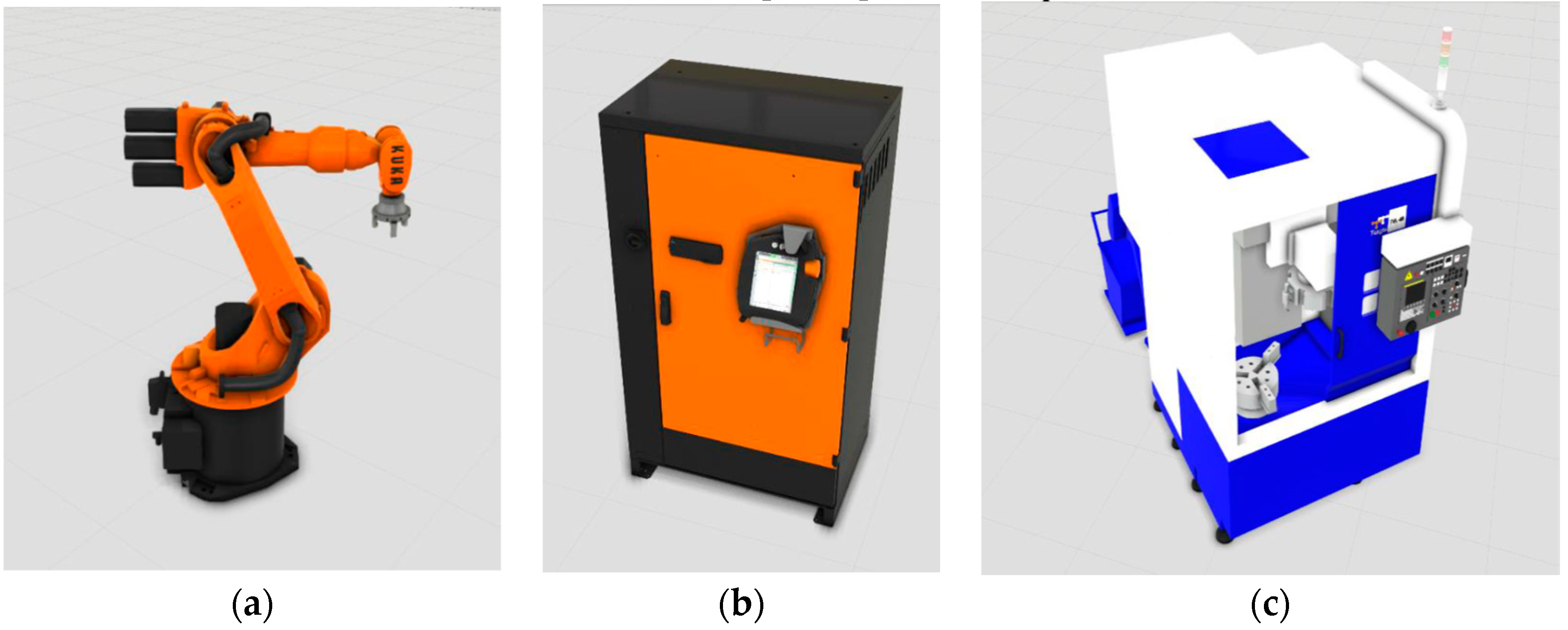

2.2.3. Work Cell Components Selection

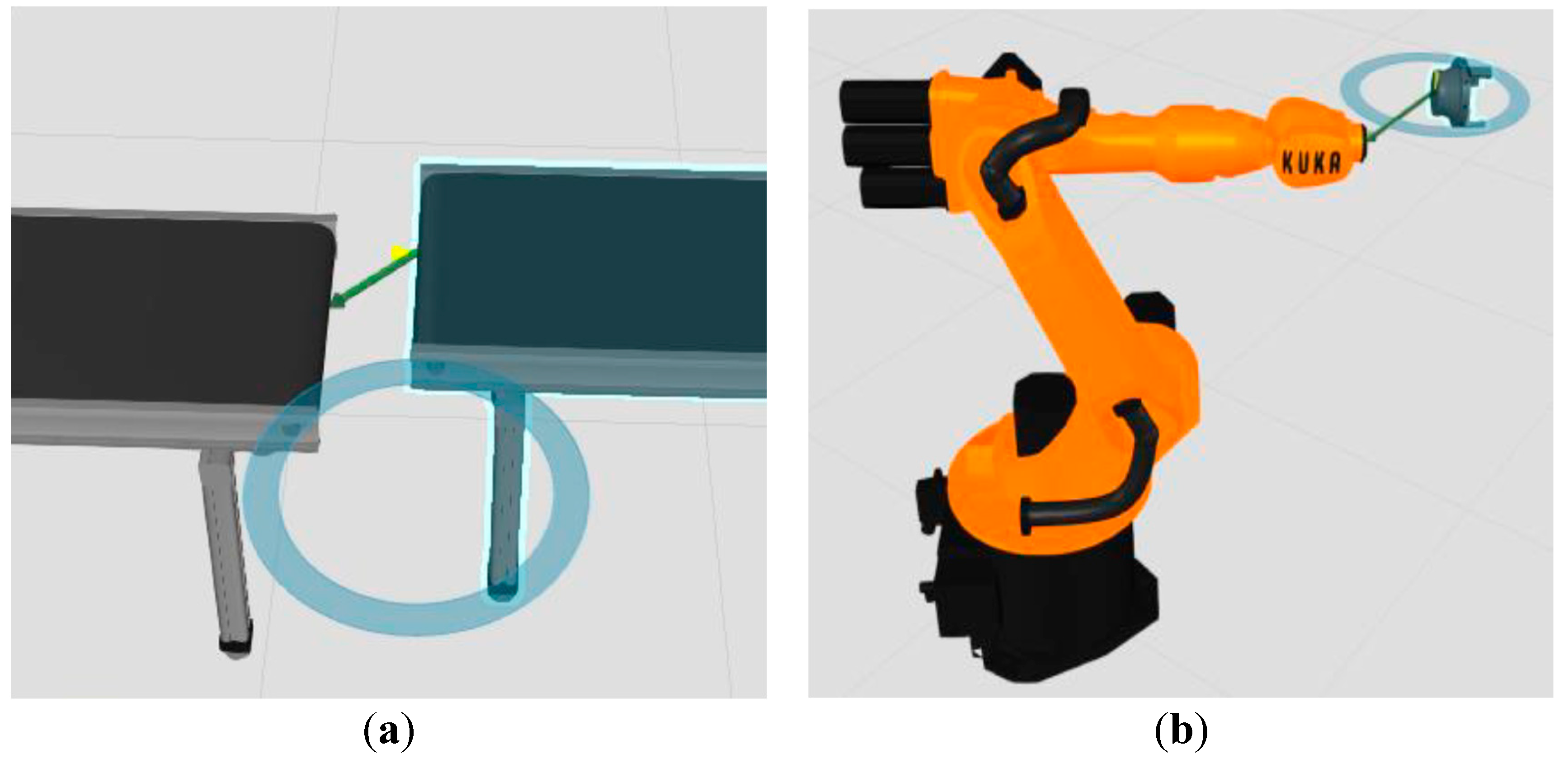

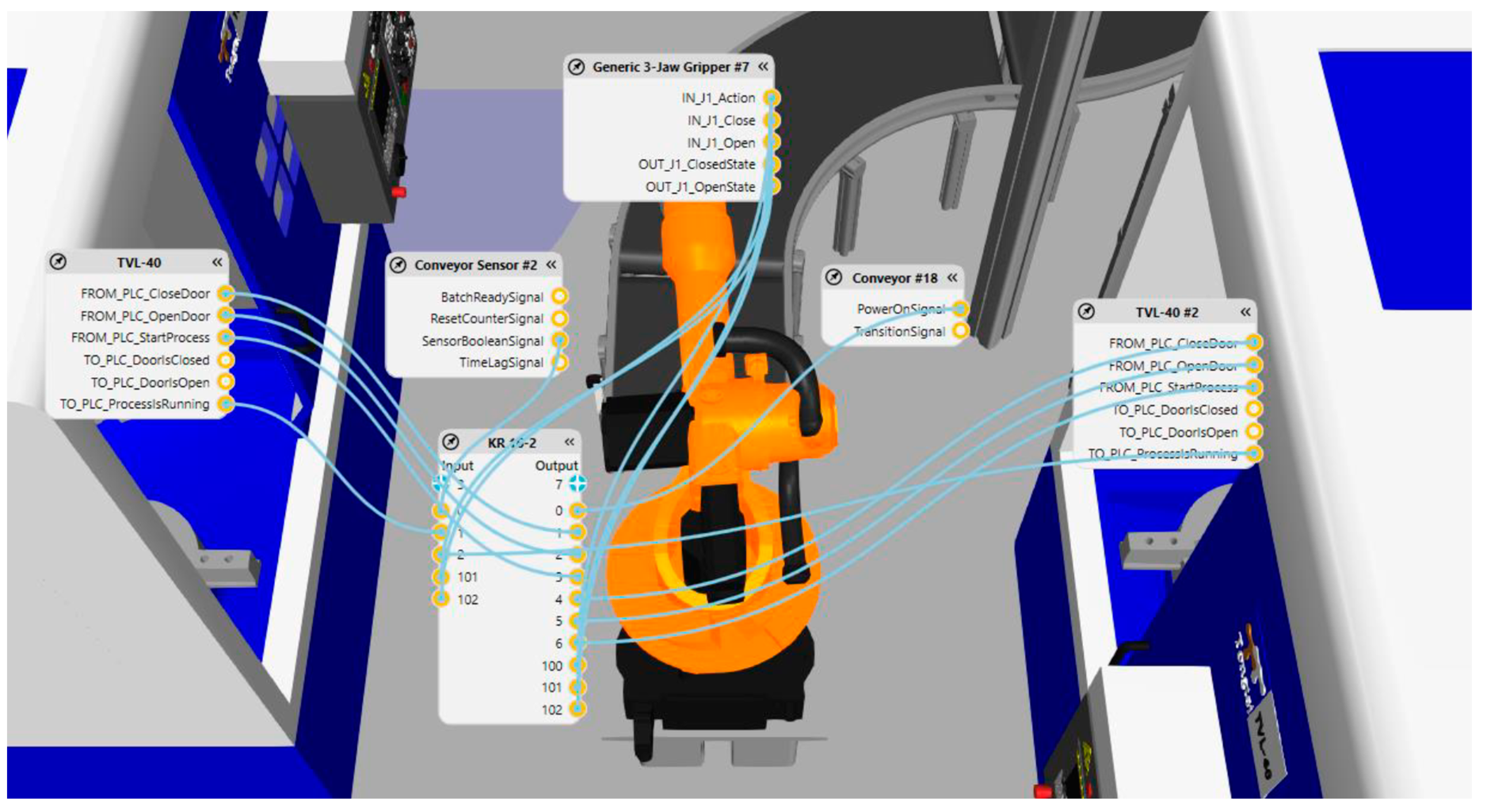

2.2.4. Implementation of the RWC Components Connections

2.2.5. Processes Performed by RWC

2.2.5. KUKA Robot Motion Control in Laboratory Environment

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Visual Components, https://www.visualcomponents.com/resources/blog/introducing-visual-components-4-4/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Pokojski, J.; Szustakiewicz, K. Towards an aided process of building a knowledge based engineering applications. Machine Dynamics Problems 2009, 33, 91–100. [Google Scholar]

- Sobieszczanski-Sobieski J., Morris A., J.L.van Tooren M. Multidisciplinary design optimization supported by knowledge based engineering, John Wiley & Sons, 2015.

- Papiernik, K.; Grabska, E.; Borkowski, A. On applying model-driven engineering to conceptual design. Machine Dynamics Problems 2007, 31, 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, C.R., et al.: Concept generation from the functional basis of design, In Proceedings of International Conference on Engineering Design ICED 2005, Melbourne, Australia, 2005.

- Gero, J.S.; Kannengiesser, U. A function–behaviour–structure ontology of processes. Artificial Intelligence for Engineering Design Analysis and Manufacturing 2007, 21, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gausemeier J., Ramming F.J., Schafer W. Design methodology for intelligent technical systems, Springer, 2014.

- Kühn, A.; Dumitrescu, R.; Gausemeier, J. Managing evolution from mechatronics to intelligent technical systems. Jurnal Teknologi 2015, 76, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miatliuk, K. Conceptual Design of Mechatronic Systems; WPB: Bialystok, Poland, 2017; Available online: https://pb.edu.pl/oficyna-wydawnicza/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2018/02/Miatluk_publikacja.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Miatliuk, K.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, K.; Siemieniako, F. Use of Hierarchical System Technology in Mechatronic.

- Design. J. Mechatron. 2010, 20, 335–339. 2010; 20, 335–339.

- Miatliuk, K. Conceptual Model in the Formal Basis of Hierarchical Systems for Mechatronic Design. J. Cybern. Syst. 2015, 46, 666–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miatluk, K.; Nawrocka, A.; Holewa, K.; Moulianitis, V. Conceptual Design of BCI for Mobile Robot Control. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RobotStudio, https://new.abb.com/products/robotics/robotstudio (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- CoppeliaSim, https://www.coppeliarobotics.com/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- DELMIA, https://www.cadsol.pl/produkty/delmia/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- RoboDK, https://robodk.com/ (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Archila, J. F., Dutra, M.S., Castro Pinto, F.A. Kinematical and Dynamical Models of KR 6 KUKA Robot, Including the Kinematic Control in a Parallel Processing Platform, Robot Manipulators, New Achievements, 2010, 601-620.

- KUKA, https://www.robots.com/images/robots/KUKA/Low-Payload/KUKA_KR_16_2_F_Datasheet.pdf (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- TongTai, https://www.tongtai.com.tw/en/product-detail.php?id=138 (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- K. Miatliuk, K., Wolniakowski, A., Kolosowski, P. Engineering system of systems conceptual design in theoretical basis of hierarchical systems, In Proceedings IEEE International Conference Systems Man and Cybernetics SMC, Toronto, Canada, 2020, IEEE xplore, 2850-2856.

- Miatluk K., Wolniakowski A., Trochimczuk R., Jorgensen J. Mechatronic Design and Control of a Robot System for Grinding, In Proceedings of IEEE/ASME International Conference on Mechatronic and Embedded Systems and Applications, Genova, Italy, 2024, 1-6.

- Wolniakowski, A.; Miatliuk, K.; Kruger, N.; Petersen, H.; Ritz, J. Task and context sensitive gripper design learning using dynamic grasp simulation. J. Intelligent and Robotic Systems 2017, 87, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valsamos, C.; Miatluk, K.; Wolniakowski, A.; Moulianitis, V.; Aspragathos, N. Optimal kinematic task position determination – application and experimental verification for the UR5 manipulator. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 9352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.; Ferrer, M.A.; Miatliuk, K.; Wolniakowski, A.; Vessio, C.; et al. Neural network modelling of kinematic and dynamic features for signature verification. Pattern Recognition Letters 2025, 187, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).