Introduction

Access to accurate and comprehensible health information is fundamental to decision-making in medical care (Adegoke et al., 2024). The growing dependence on digital health resources highlights this necessity: a 2022 global survey revealed that nearly 75% of patients seek online medical information before consulting healthcare professionals (Calixte et al., 2020). However, the quality and readability of such materials often vary significantly, frequently neglecting to account for disparities in health literacy levels (Evangelista et al., 2010). This challenge is particularly pronounced in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS), a condition affecting approximately 2–3% of children and adolescents globally, where treatment decisions hinge on complex factors such as curvature severity, skeletal maturity, and patient adherence to prescribed therapies.

Patients with scoliosis and their caregivers necessitate educational resources that are lucid and accessible to comprehend treatment alternatives, including bracing, physiotherapy, and surgical interventions. Although clinicians strive to simplify medical jargon, numerous families are progressively relying on AI-generated content as supplementary information sources (Zhang & Kamel Boulos, 2023). This trend raises critical concerns regarding the accuracy, clarity, and reliability of AI-generated health information, as prior studies have shown that such content often lacks appropriate citations and personalization, potentially leading to misinformation (Moore et al., 2024; Shekar et al., 2024; Shin et al., 2024). Given that AIS management involves long-term adherence and informed risk assessment, the quality of AI-generated educational materials demands rigorous evaluation.

In addition to readability, the capacity of AI-generated content to promote patient engagement and treatment adherence is equally critical. Research indicates that low health literacy can result in poorer health outcomes, reduced treatment adherence, and misinterpretation of medical advice (Berkman et al., 2011). Cognitive development limitations in teenage parents may further hinder comprehension, complicating the application of complex medical information to daily self-care. In the context of AIS, inadequate educational materials may lead to misconceptions about the condition, reduced adherence to bracing therapy, or delays in seeking necessary interventions. Therefore, AI-generated scoliosis educational materials must be both accurate and accessible to enhance patient literacy and self-management outcomes.

While previous studies have explored the clarity and empathy of AI-generated scoliosis education materials, existing evaluations predominantly depend on subjective assessments, such as user satisfaction ratings (Lang et al., 2024). Although useful, these methods may introduce bias and fail to provide an objective measurement of content quality and readability. Building upon prior research, the study adopts a more rigorous, data-driven approach, systematically evaluating AI-generated scoliosis education materials through standardized readability metrics and content quality assessments. The study seeks to elucidate the strengths and limitations of AI-generated health information to enhance the creation of more effective AI-driven educational resources for adolescent scoliosis patients and their caregivers.

Methods

Study Design

This study systematically evaluated AI-generated patient education materials on AIS using validated metrics to overcome this gap. Specifically, we assessed readability and informational integrity in outputs from five prominent natural language processing models: ChatGPT-4o (OpenAI), a multimodal AI system optimized for clinical reasoning; ChatGPT-o1, an earlier iteration of OpenAI’s multimodal AI, known for its strong language generation capabilities, ChatGPT-o3 mini - high (OpenAI), a lightweight model released in February 2025, emphasizing resource-efficient text generation DeepSeek-V3 (DeepSeek Inc.), and DeepSeek-R1, which incorporates cognitive architecture to enhance explanatory coherence.

On February 9, 2025, the five models were utilized to respond to common patient questions regarding the three major categories of adolescent scoliosis: idiopathic, neuromuscular, and congenital. These inquiries aimed to elicit accessible, user-friendly medical information from AI systems, following the approach outlined by Akkan and Seyyar (2025).

Table 1.

Questions for adolescent scoliosis terminology clarification.

Table 1.

Questions for adolescent scoliosis terminology clarification.

| Prompt |

| “I need information about ‘Idiopathic Adolescent Scoliosis.’ I’m not familiar with medical terms. Can you help clarify this for me?” |

| “I need information about ‘Neuromuscular Scoliosis’ in adolescents. I’m not familiar with medical terms. Can you help clarify this for me?” |

| “I need information about ‘Congenital Scoliosis’ in adolescents. I’m not familiar with medical terms. Can you help clarify this for me?” |

The DISCERN score assesses the quality of AI-generated responses using two validated tools. The DISCERN score was developed as an instrument for assessing the quality of written patient information related to treatment options (Charnock et al., 1999). It consists of three structured sections: (1) eight questions evaluating the reliability of the information presented, (2) seven questions focusing on the completeness and accuracy of treatment-related details, and (3) a final overall quality rating. The total possible score is 80, with classifications as follows: a score exceeding 70 is considered “excellent,” while a score above 50 is deemed “fair.”

The readability of the responses was evaluated using two recognized metrics: the Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease Score (FRES) and the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL) (Flesch, 1948). The FRES assigns a numerical readability score ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating simpler and more accessible text. A score approaching 100 suggests that the content is very easy to understand, whereas lower scores denote increased complexity. The FKGL is an adaptation of the FRES that estimates the minimum education level required for comprehension. A higher FKGL score signifies increased complexity, indicating that individuals with lower formal education may struggle to comprehend the topic. The readability was calculated using the WebFX online readability test (Readability Test, 2025).

Continuous variables were presented as their raw values. The average DISCERN score by two reviewers was also calculated by two independent authors (DISCERN scores by MZ and XS). Graphing and statistical tests were performed in R-Studio version 4.2.2.

Results

Readability

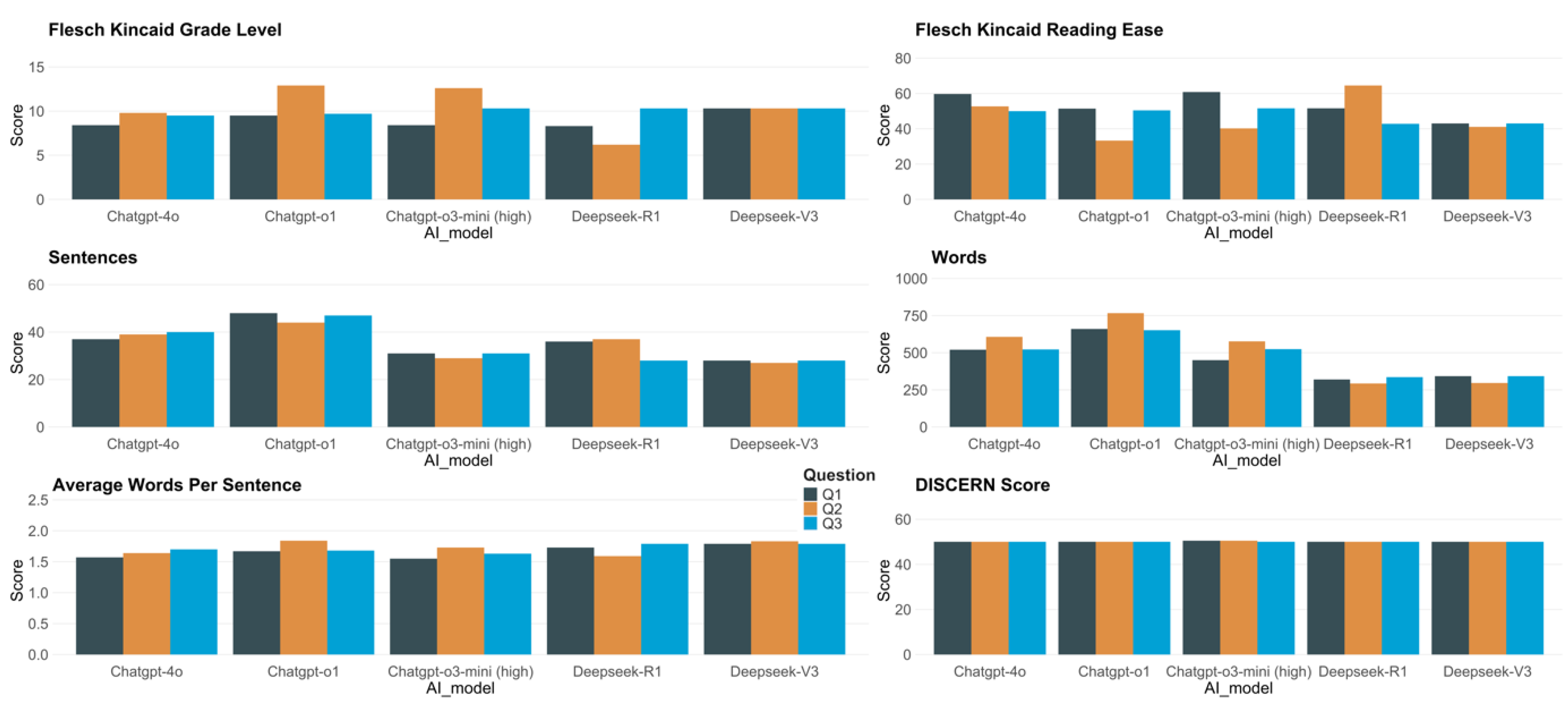

Figure 1 (subplots a–e) presents the readability outcomes for responses generated by five models—Deepseek-V3, Deepseek-R1, ChatGPT-4o, ChatGPT-o3-mini (high), and ChatGPT-o1—across three prompts (Q1, Q2, Q3).

According to the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (FKGL), Deepseek-R1 generally produced the most accessible texts, evidenced by its lowest score of 6.2 (Q2). Conversely, ChatGPT-o3-mini (high) and ChatGPT-o1 occasionally yielded more challenging content, both above FKGL 12.0 on Q2 (12.6 and 12.9, respectively), suggesting material that may require college-level reading skills. ChatGPT-4o exhibited a moderate level of difficulty, with FKGL values ranging from 8.4 to 9.8, while Deepseek-V3 consistently achieved FKGL 10.3 across all prompts.

In reference to the Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease (FKRE), ChatGPT-o3-mini (high) achieved the highest individual score of 60.8 on Q1, indicating relatively easy-to-read content. At the other end, ChatGPT-o1 reached the lowest FKRE of 33.3 (Q2), reflecting more intricate text. Deepseek-R1 ranged from 42.8 to 64.5, notably featuring the highest reading ease score overall (64.5, Q2). ChatGPT-4o produced moderately accessible responses (FKRE 50.0–59.7), whereas Deepseek-V3 maintained a narrower band of 41.1–43.0, indicating a comparatively denser style.

Analyses of sentence and word counts further underscore differences in verbosity and structure. ChatGPT-o1 generated the lengthiest responses, comprising up to 767 words (Q2) and as many as 48 sentences (Q1). Despite ChatGPT-o3-mini (high) reaching a considerable word count (577 in Q2), it tended to use fewer overall sentences (29–31). Meanwhile, Deepseek-R1 maintained concise outputs (293–336 words), coupled with shorter average sentence lengths (around 1.59–1.79 in the table’s measure). ChatGPT-4o fell between 520 and 607 words and comprised 37 to 40 sentences for each response.

As illustrated in

Figure 1 (subplot f), the reviewer-based scores (Reviewer 1, Reviewer 2) and their average remained relatively consistent, hovering around 50.0–50.5 across all models. No substantive differences emerged in these quality assessments, suggesting comparable performance on this metric for each system’s generated responses.

Figure 1.

Readability and DISCERN score of the response from ChatGPT and Deepseek for the three questions.

Figure 1.

Readability and DISCERN score of the response from ChatGPT and Deepseek for the three questions.

Discussion

The study conducts a comparative evaluation of five large language models (LLMs) in generating medical information, emphasizing readability and content quality. The findings reveal significant disparities in readability across the models. Notably, Deepseek-R1 produces the most comprehensible content, whereas ChatGPT-o3-mini (high) and ChatGPT-o1 generate more complex texts that require higher reading proficiency. Notwithstanding these variations in readability, all models attain similar DISCERN scores, suggesting that while sentence structures and complexity differ, the overall quality of medical information remains stable.

Consistent with previous research on LLMs in medical applications, the architecture of AI models significantly influences text readability (Behers et al., 2024). In our study, ChatGPT-o3-mini (high) and ChatGPT-o1 received elevated FKGL scores, signifying increased syntactic complexity and denser vocabulary. This trend aligns with previous findings that smaller or less optimized LLMs often mitigate their limited contextual understanding by increasing information density, leading to longer sentences and a higher prevalence of medical terminology (Mannhardt et al., 2024). The two DeepSeek models demonstrate outstanding performance in terms of readability. However, research on these models remains limited, and there is currently no systematic analysis in the literature exploring the potential reasons behind their superior performance. We hypothesize that several factors may contribute to this advantage. First, DeepSeek may employ a more advanced neural network architecture, incorporating more efficient attention mechanisms, deeper model structures, or optimized parameter tuning, allowing it to capture linguistic patterns with greater precision during text comprehension and generation. Second, the model might have been trained on a larger and higher-quality dataset, which could enhance its language understanding capabilities and improve text fluency. Additionally, DeepSeek may leverage fine-tuning strategies specifically designed to optimize readability, further refining the coherence and clarity of the generated text. Finally, optimizations at the inference stage, such as improved sampling methods or decoding strategies, may also contribute to producing text that aligns more closely with natural language conventions. Nevertheless, these remain speculative explanations, and future research should further investigate the specific optimization strategies that contribute to DeepSeek’s readability performance.

The observed differences in model behavior highlight a critical design consideration in LLMs: certain models prioritize simplified content to enhance accessibility, whilst others emphasize precision and depth, rendering them more suitable for audiences with elevated health literacy. Nevertheless, excessive simplification can sometimes lead to the omission of essential medical information. For example, it is reported that when AI-generated content is oversimplified, a substantial amount of critical information is omitted. Oversimplified explanations in teaching materials on scoliosis inadequately represent the complexity of the disease. This poses significant challenges for adolescent patients, as it may impede their understanding of disease progression, potential consequences, and the necessity for timely intervention. Ambiguous explanations may encourage patients or their parents to underestimate the importance of early treatment, leading to delayed medical intervention.

Additionally, patients’ ability to process medical information differs considerably depending on their developmental stage and age. Individuals with limited health literacy, especially younger ones, often struggle to grasp abstract medical concepts. They rely increasingly on intuitive analogies, visual aids (such as diagrams or animations), and narrative storytelling to build foundational knowledge of diseases. However, current LLMs focus primarily on enhancing text readability rather than diversifying information presentation. This constraint suggests that, even if text readability improves, key medical concepts may be ineffectively communicated, especially for complex diseases.

Moreover, adolescents prioritize different aspects of medical information compared to adults. They concentrate on the implications of a disease on their daily existence, including whether scoliosis would limit physical activities, alter body posture, or impact social interactions and self-esteem. However, current medical information dissemination strategies are predominantly designed for parents or healthcare professionals, rather than directly targeting adolescents. This "bystander" communication approach often overlooks adolescents’ autonomy and emotional needs, leading to a fragmented understanding of their condition or potential resistance to medical advice (Chen et al., 2020). If AI-generated information overemphasizes the need for medical intervention while neglecting lifestyle or exercise recommendations, adolescents may perceive limited personal choice, hence reducing their acceptance of treatment plans. Therefore, merely simplifying language or enhancing readability is insufficient; the key lies in developing a personalized information framework that caters to different age groups and psychological needs.

Future optimization efforts should transcend traditional text modifications by integrating insights from cognitive science and health communication research. For example, interactive Q&A models could augment adolescents' engagement, while adapting medical content to social media formats may better correspond with their reading preferences. Simultaneously, it is essential to avoid excessive simplification that undermines the scientific integrity of medical information. The ultimate goal is to ensure that audiences understand medical content and may make informed health decisions based on complete and accurate information.

Despite the evident differences in readability among models, the study reveals that their DISCERN scores remain relatively consistent, indicating that content quality is not significantly affected by textual complexity. However, a major limitation common to all models is the absence of explicit source citations—a well-documented issue in AI-generated medical content. Aljamaan et al. (2023) highlighted that AI medical chatbots frequently produce "hallucinated" citations, referencing inaccurate or non-existent sources. This problem is particularly prevalent in ChatGPT and Bing-generated medical content (Aljamaan et al., 2023). Additionally, Graf et al. (2023) substantiated that mainstream AI models perform poorly in the accuracy of scientific citation, especially in medical literature, frequently leading to misleading conclusions (Graf et al., 2023).

The lack of reliable references diminishes the credibility and verifiability of AI-generated health information and poses potential risks to medical decision-making. Shekar et al. (2024) found that general users often fail to distinguish AI-generated medical advice from professional recommendations, displaying high levels of trust in AI-generated content, even when it contains inaccuracies (Shekar et al., 2024). This over-reliance on AI-generated health information, along with citation deficiencies, increases the risk of widespread misinformation among the public.

Beyond citation concerns, another critical limitation is the lack of adaptive personalization in AI-generated health content. Current AI models rely on generalized information-generation strategies, failing to dynamically tailor content according to an individual's health literacy, prior knowledge, or cognitive capacity. Golan et al. (2023) suggest that personalized health education materials markedly enhance patient understanding and adherence to treatment plans, particularly for those with complex medical conditions (Golan et al., 2023). Nonetheless, existing AI systems continue to offer "one-size-fits-all" medical information, which not only inadequately addresses diverse patient requirements but may also result in misinterpretations or cognitive overload. This limitation is especially evident in scoliosis-related health communication. Adolescents and their parents often possess divergent apprehensions about scoliosis, such as its effects on daily life, physical appearance, and mental well-being. However, AI-generated texts frequently neglect to adequately address these aspects, reducing the practical relevance of the information.

Limitation

One major limitation of this study is the rapid evolution of AI, meaning that future versions may enhance transparency and clinical applicability, hence rendering the current conclusions time-sensitive. Another is that the quality of AI responses was judged based on expert opinion rather than clinical trials. Future studies should integrate feedback from both physicians and patients to comprehensively evaluate the reliability of AI-generated medical services. Ultimately, the study exclusively compared models from ChatGPT and Deepseek; subsequent work should encompass a wider array of AI models for comparison.

Conclusions

The study highlights notable differences in the readability of AI-generated medical texts. Among the evaluated models, Deepseek-R1 produces the most understandable content, whereas ChatGPT-o3-mini (high) and ChatGPT-o1 often provide more complex responses. Despite these readability disparities, the overall level of content remains consistent across models, with all five LLMs achieving comparable DISCERN scores. Future advancements should focus on enhancing readability without compromising informational integrity, integrating real-time citation mechanisms, and developing AI systems to customize responses based on users' health literacy and individual medical conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

McZ contributed to conceptualization, methodology, software, investigation, data curation, writing – original draft, and visualization. HH contributed to methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, and data curation. MZ contributed to conceptualization, validation, writing–review & editing. XS contributed to conceptualization, validation, writing–review & editing, supervision, and project administration. YH contributed to the formal analysis and visualization. YZ contributed to the formal analysis and visualization. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to the developers of ChatGPT and DeepSeek for their valuable contributions.

Additional Information

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Clinical Trial Number

Not applicable.

List of Abbreviations

AI – Artificial Intelligence, FKGL – Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, FKRE – Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease, DISCERN – A standardized tool for assessing the quality of written consumer health information.

References

- Adegoke, B. O., Odugbose, T., & Adeyemi, C. (2024). Assessing the effectiveness of health informatics tools in improving patient-centered care: A critical review. International journal of chemical and pharmaceutical research updates [online], 2(2), 1-11.

- Akkan, H., & Seyyar, G. K. (2025). Improving readability in AI-generated medical information on fragility fractures: the role of prompt wording on ChatGPT’s responses. Osteoporosis International, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Behers, B., Vargas, I., Behers, B., Rosario, M., Wojtas, C., Deevers, A., & Hamad, K. (2024). Assessing the Readability of Patient Education Materials on Cardiac Catheterization From Artificial Intelligence Chatbots: An Observational Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus, 16. [CrossRef]

- Berkman, N., Sheridan, S., Donahue, K., Halpern, D., Viera, A., Crotty, K., Holland, A., Brasure, M., Lohr, K., Harden, E., Tant, E., Wallace, I., & Viswanathan, M. (2011). Health literacy interventions and outcomes: an updated systematic review. Evidence report/technology assessment, 199, 1-941. https://consensus.app/papers/health-literacy-interventions-and-outcomes-an-updated-berkman-sheridan/35e4d784e988541abbe4a20adbc4c21c/.

- Calixte, R., Rivera, A., Oridota, O., Beauchamp, W., & Camacho-Rivera, M. (2020). Social and Demographic Patterns of Health-Related Internet Use Among Adults in the United States: A Secondary Data Analysis of the Health Information National Trends Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6856. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/18/6856. [CrossRef]

- Charnock, D., Shepperd, S., Needham, G., & Gann, R. (1999). DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 53(2), 105-111. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-Y., Lo, F., & Wang, R.-H. (2020). Roles of emotional autonomy, problem-solving ability and parent-adolescent relationships on self-management of adolescents with type 1 diabetes in Taiwan. Journal of pediatric nursing. [CrossRef]

- Evangelista, L. S., Rasmusson, K. D., Laramee, A. S., Barr, J., Ammon, S. E., Dunbar, S., Ziesche, S., Patterson, J. H., & Yancy, C. W. (2010). Health literacy and the patient with heart failure—implications for patient care and research: a consensus statement of the Heart Failure Society of America. Journal of cardiac failure, 16(1), 9-16. [CrossRef]

- Lang, S., Vitale, J., Galbusera, F., Fekete, T., Boissiere, L., Charles, Y. P., Yucekul, A., Yilgor, C., Núñez-Pereira, S., Haddad, S., Gomez-Rice, A., Mehta, J., Pizones, J., Pellisé, F., Obeid, I., Alanay, A., Kleinstück, F., Loibl, M., & Group, E. E. S. S. (2024). Is the information provided by large language models valid in educating patients about adolescent idiopathic scoliosis? An evaluation of content, clarity, and empathy. Spine Deformity. [CrossRef]

- Mannhardt, N., Bondi-Kelly, E., Lam, B., O'Connell, C., Asiedu, M., Mozannar, H., Agrawal, M., Buendia, A., Urman, T., Riaz, I., Ricciardi, C., Ghassemi, M., & Sontag, D. (2024). Impact of Large Language Model Assistance on Patients Reading Clinical Notes: A Mixed-Methods Study. ArXiv, abs/2401.09637. [CrossRef]

- Moore, I., Magnante, C., Embry, E., Mathis, J., Mooney, S., Haj-Hassan, S., Cottingham, M., & Padala, P. (2024). Doctor AI? A pilot study examining responses of artificial intelligence to common questions asked by geriatric patients. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 7. [CrossRef]

- Readability Test. (2025). https://www.webfx.com/tools/read-able/.

- Shekar, S., Pataranutaporn, P., Sarabu, C., Cecchi, G., & Maes, P. (2024). People over trust AI-generated medical responses and view them to be as valid as doctors, despite low accuracy. ArXiv, abs/2408.15266. [CrossRef]

- Shin, D., Jitkajornwanich, K., Lim, J. S., & Spyridou, A. (2024). Debiasing misinformation: how do people diagnose health recommendations from AI? Online Inf. Rev., 48, 1025-1044. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P., & Kamel Boulos, M. N. (2023). Generative AI in medicine and healthcare: promises, opportunities and challenges. Future Internet, 15(9), 286. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).