Submitted:

15 February 2025

Posted:

18 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

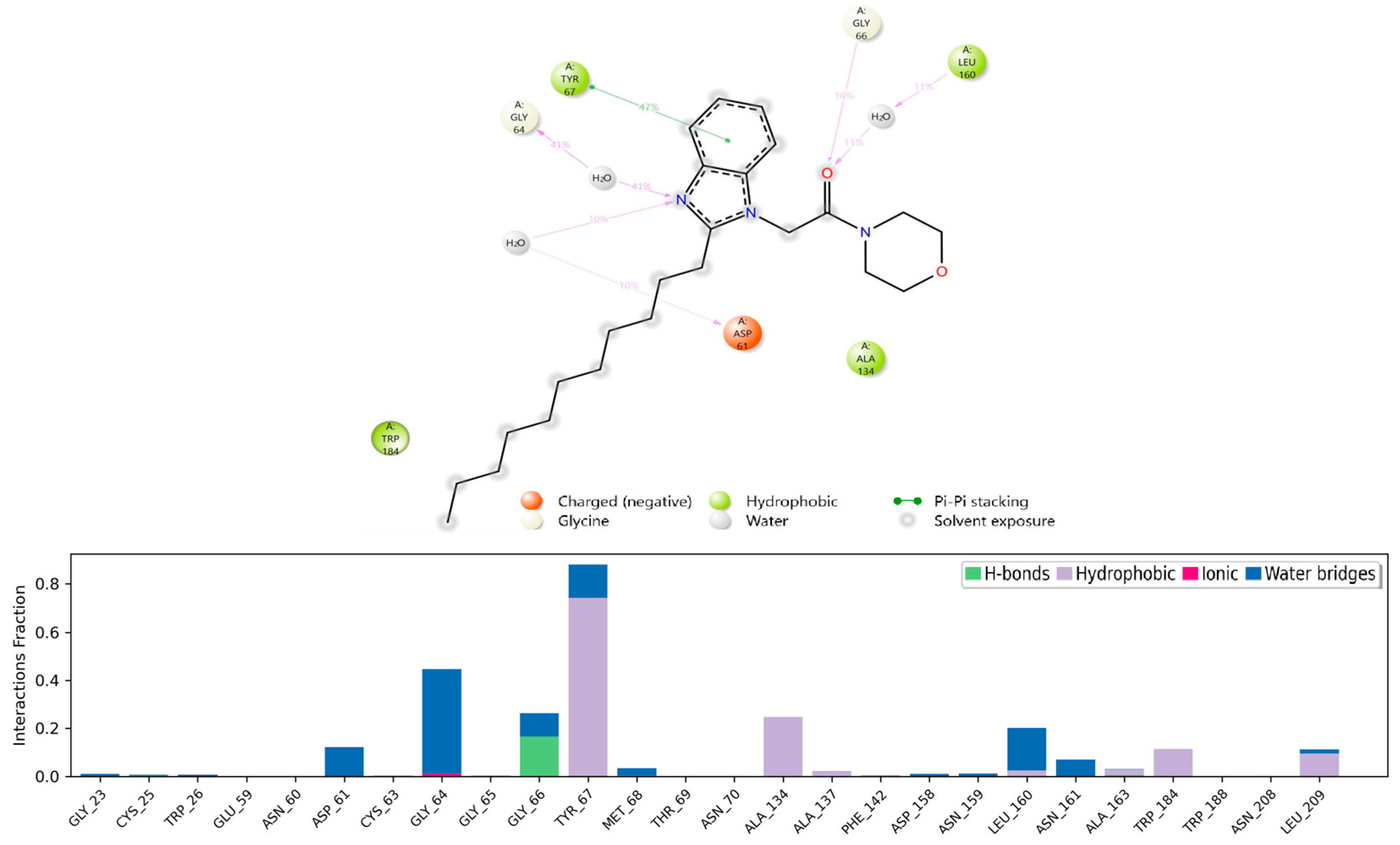

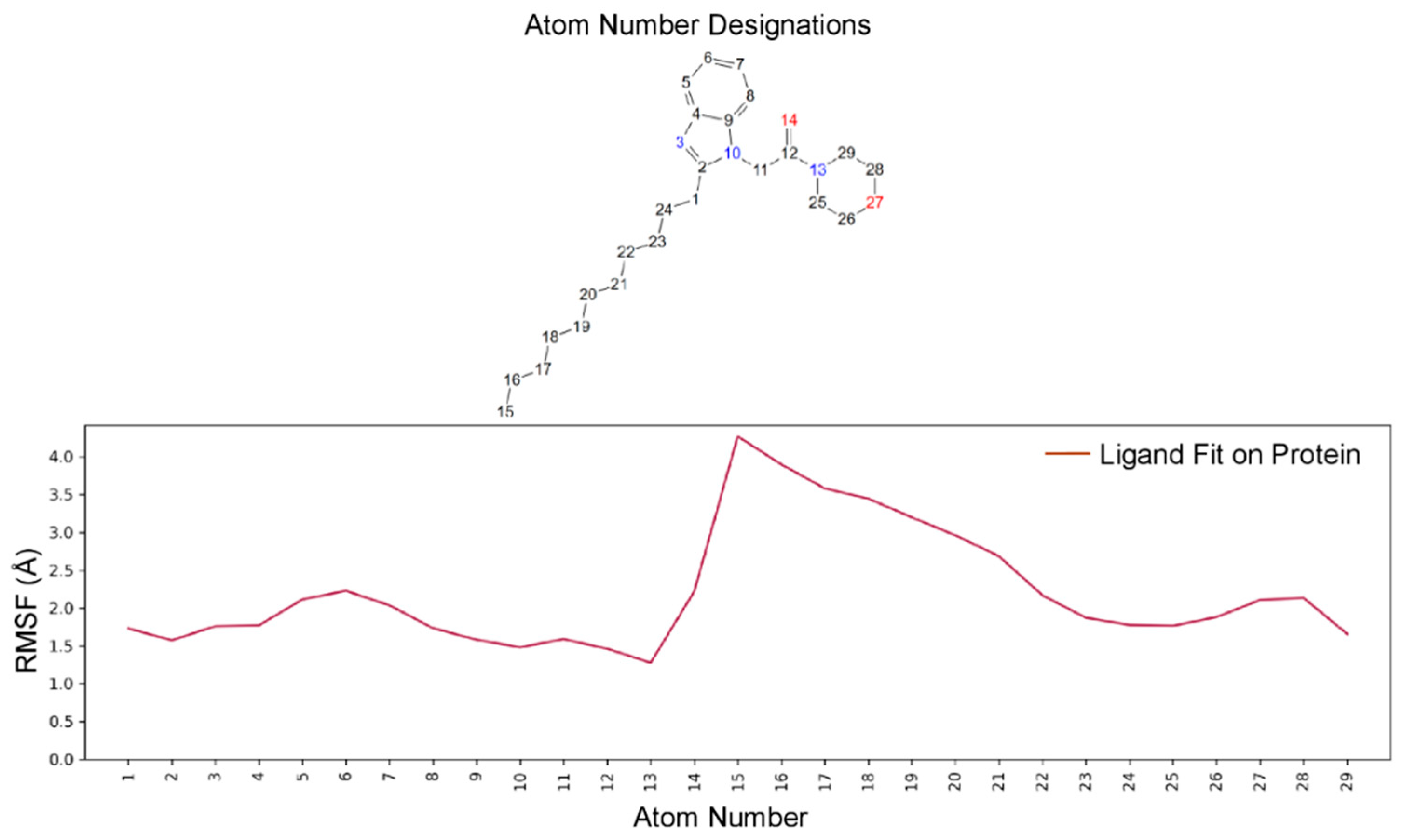

One of the most dangerous types of breast cancer that can spread from its original location to neighboring tissues is invasive breast cancer. Cathepsins, a group of proteolytic enzymes, has been thoroughly investigated in relation to cancer progression and has been shown to be crucial for the invasion and metastasis of breast cancer cells. A series of new N-alkyl-2-(2-undecyl-1H-benzimidazol-1-yl) acetamides were prepared from 2-(2-undecyl-1H-benzimidazol-1-yl)ethanhydrazide via azide coupling method with a variety of amines. The new compounds were designed to inhibit proliferation of breast cancer cells based on inhibition of the selectively and highly expressed cathepsin K. The compounds were tested for their antiproliferative activity on four cancer cell lines, namely, A549, MDA-MB231, MCF-7, U87, and HEK293 to elucidate their preferential activity on invasive breast cancer cells. The results showed that most compounds exerted enhanced activity against MDA-MD231 compared to other cell lines. Compounds 7h, 7i, 7a, and 7j showed the highest inhibition with IC50s of 17, 27, 38, and 67 μg/ml respectively. Compounds 7a, and 7j showed the highest selectivity to MDA-MD231 in terms of degree of inhibition. Molecular docking supported the cathepsin K mediated activity where compound 7i, the most potent compound, showed the best docking score of -7.126 with a low RMSD to the co-crystallized ligand pose. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations demonstrated that 7i maintained stability within the binding pocket with minimal fluctuations. The postulated lipo-philicity impact on activity was evaluated through LLE calculations, where values for the most active compounds demonstrated that optimal potency was frequently associated with moderate lipophilicity, as seen in compound 7i (LLE = 2.69). Thus, the developed compounds are promising antiproliferative agents for invasive breast cancer where a cathepsin inhibition pathway is implicated.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

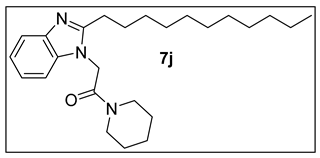

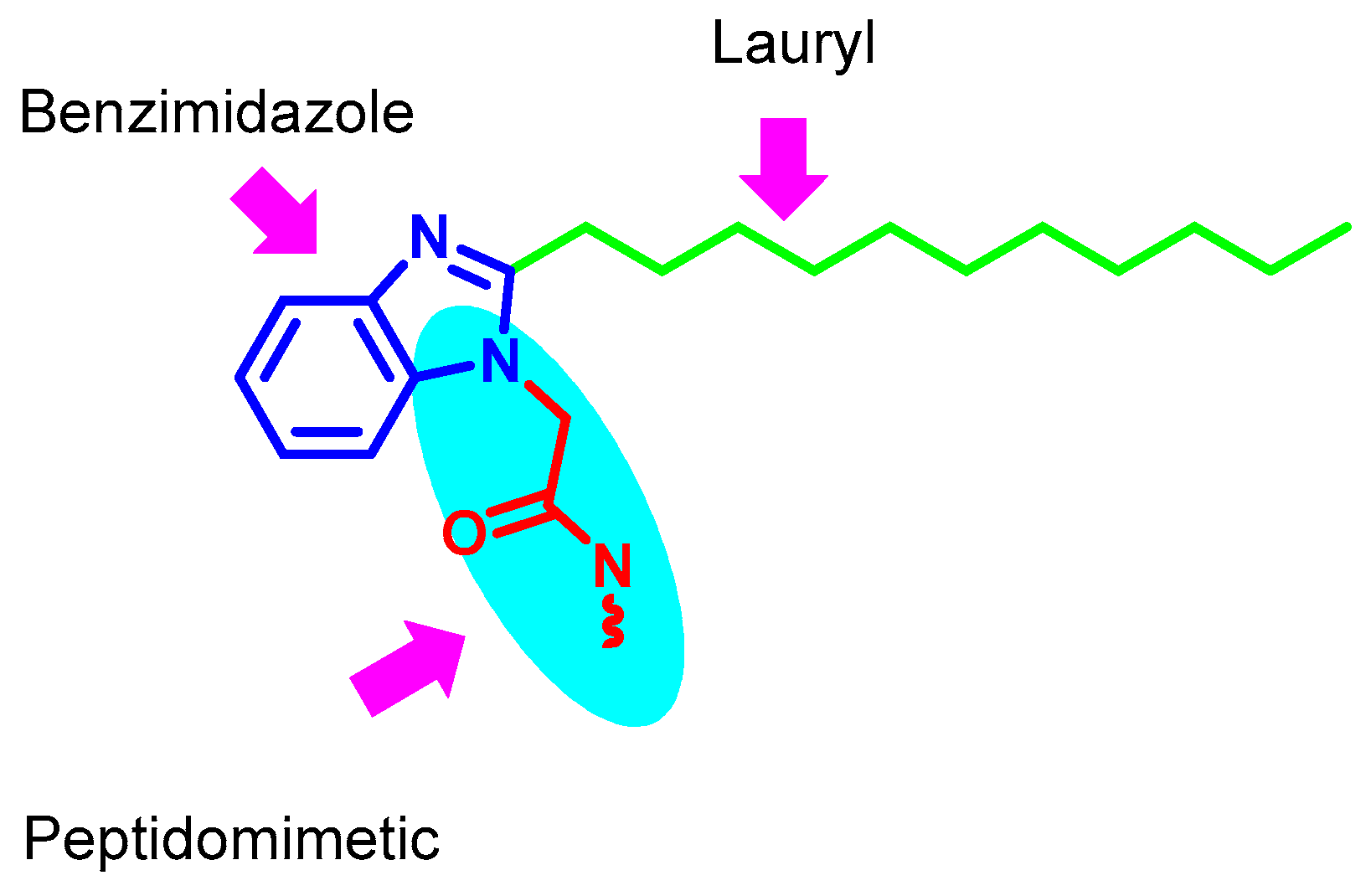

2.1. Compounds Design

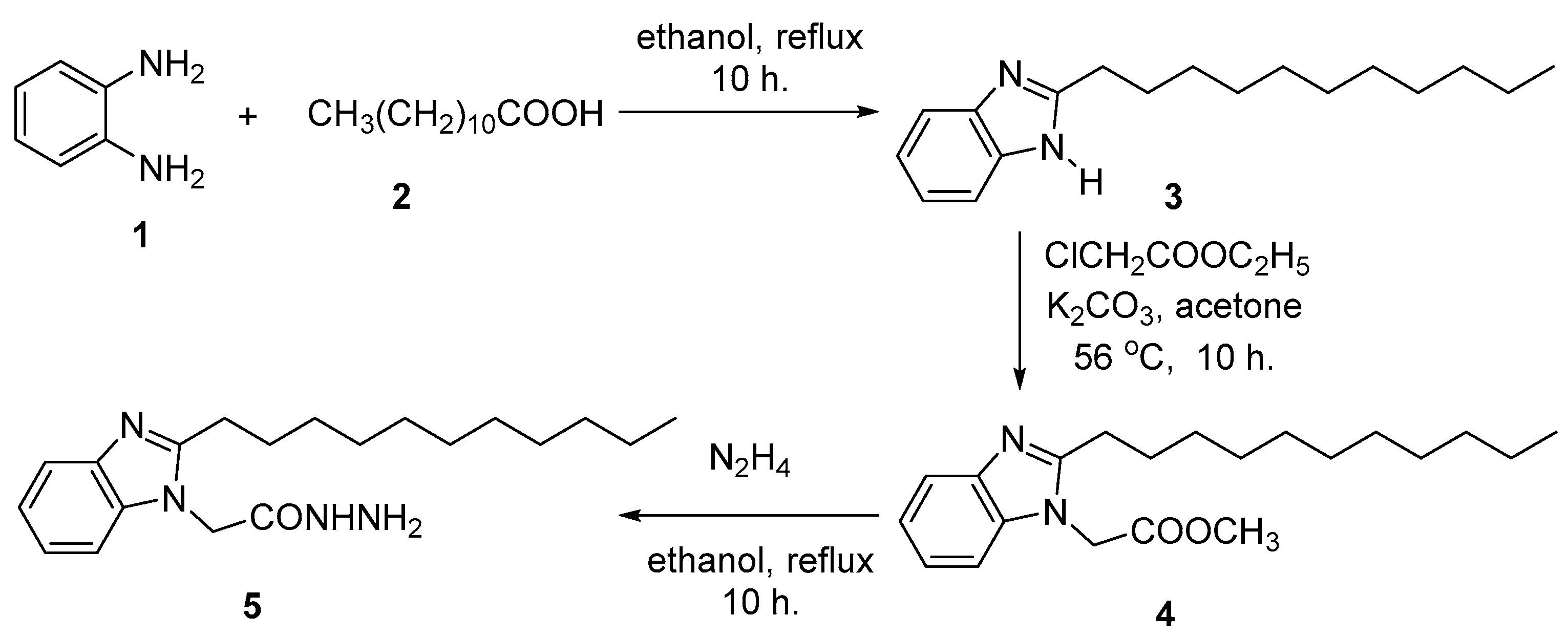

2.2. Chemical Synthesis

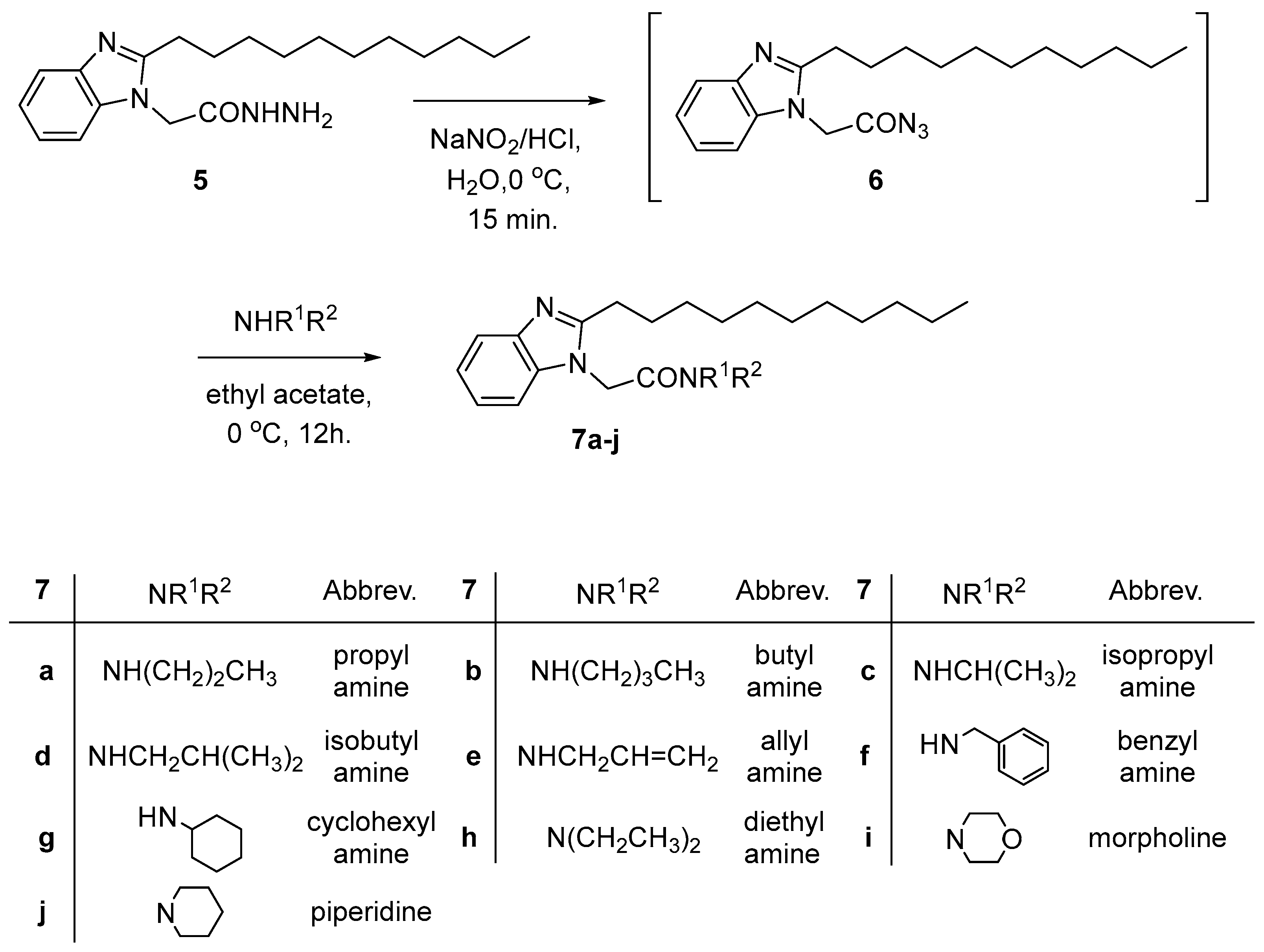

2.3. Antiproliferative Assay

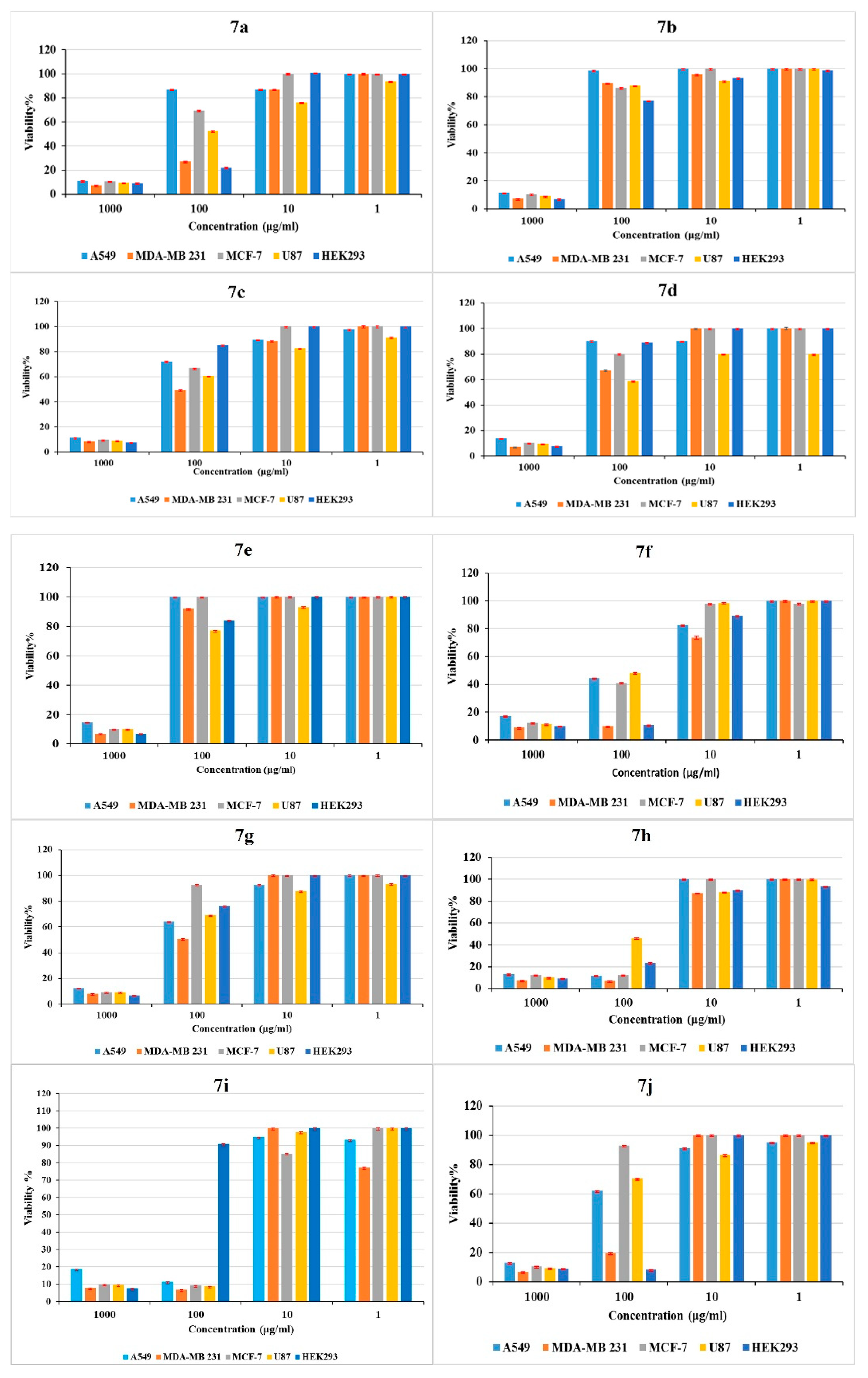

2.4. Ligand Lipophilic Efficiency (LLE)

2.5. In-Silico Analysis

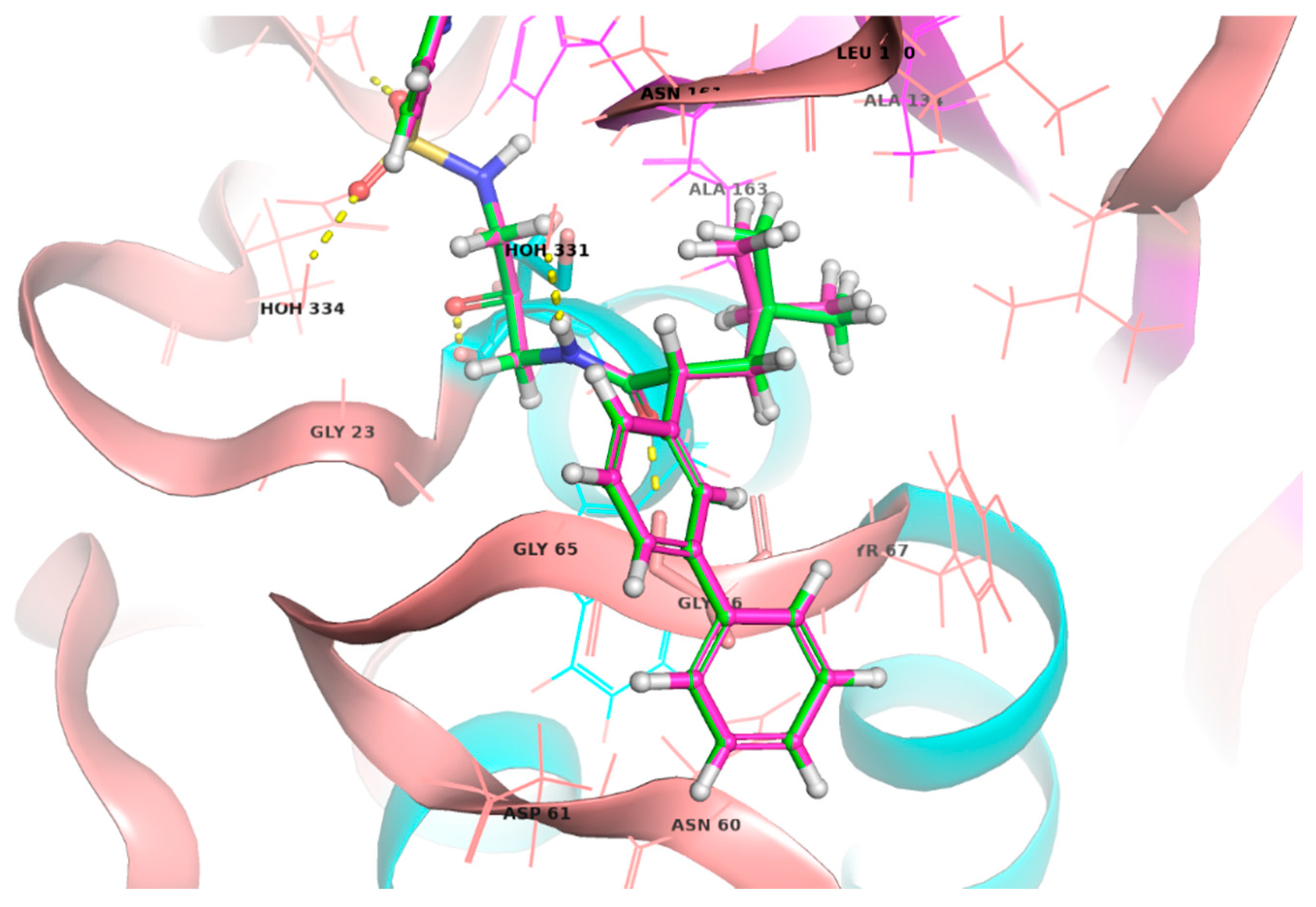

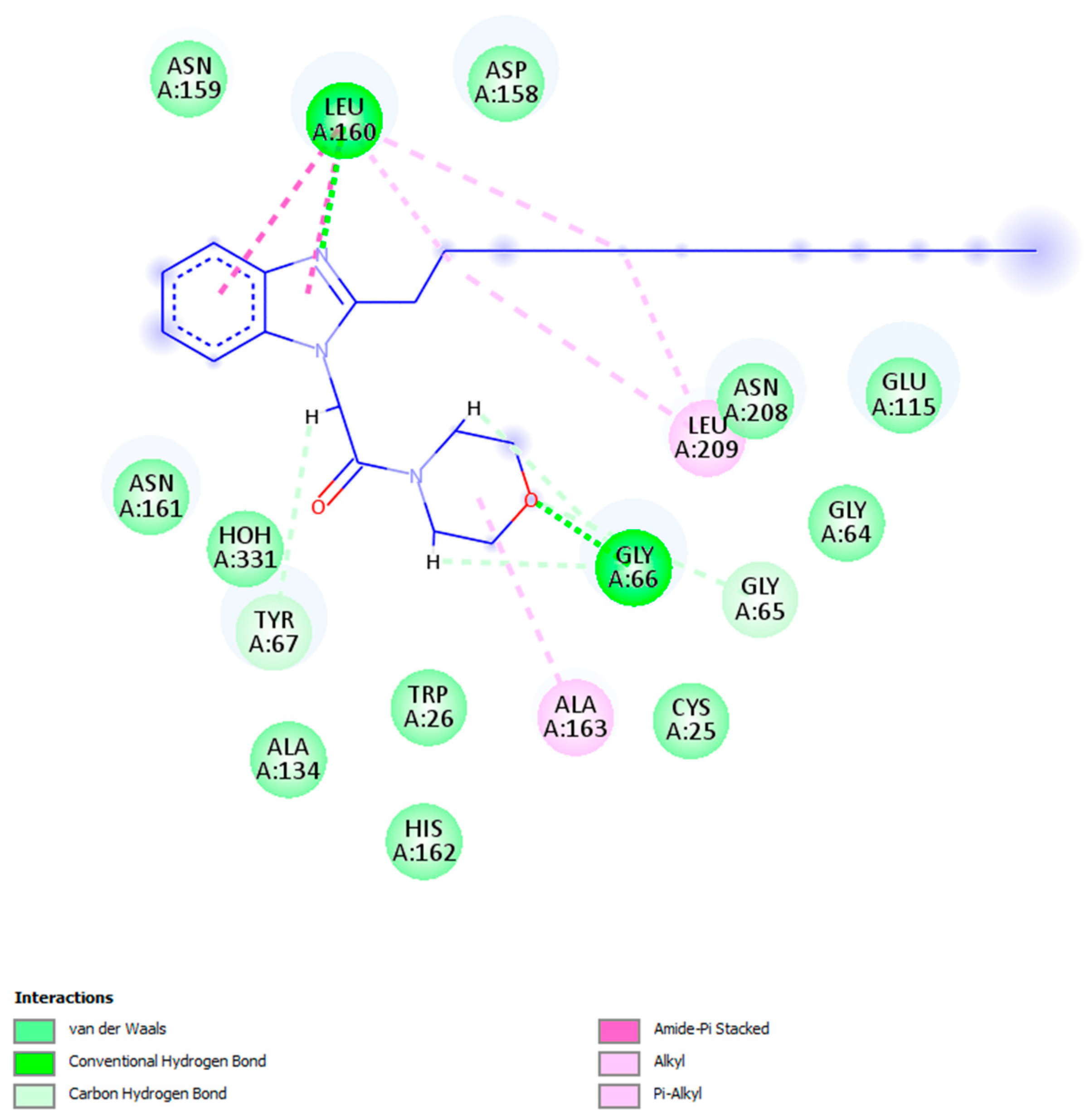

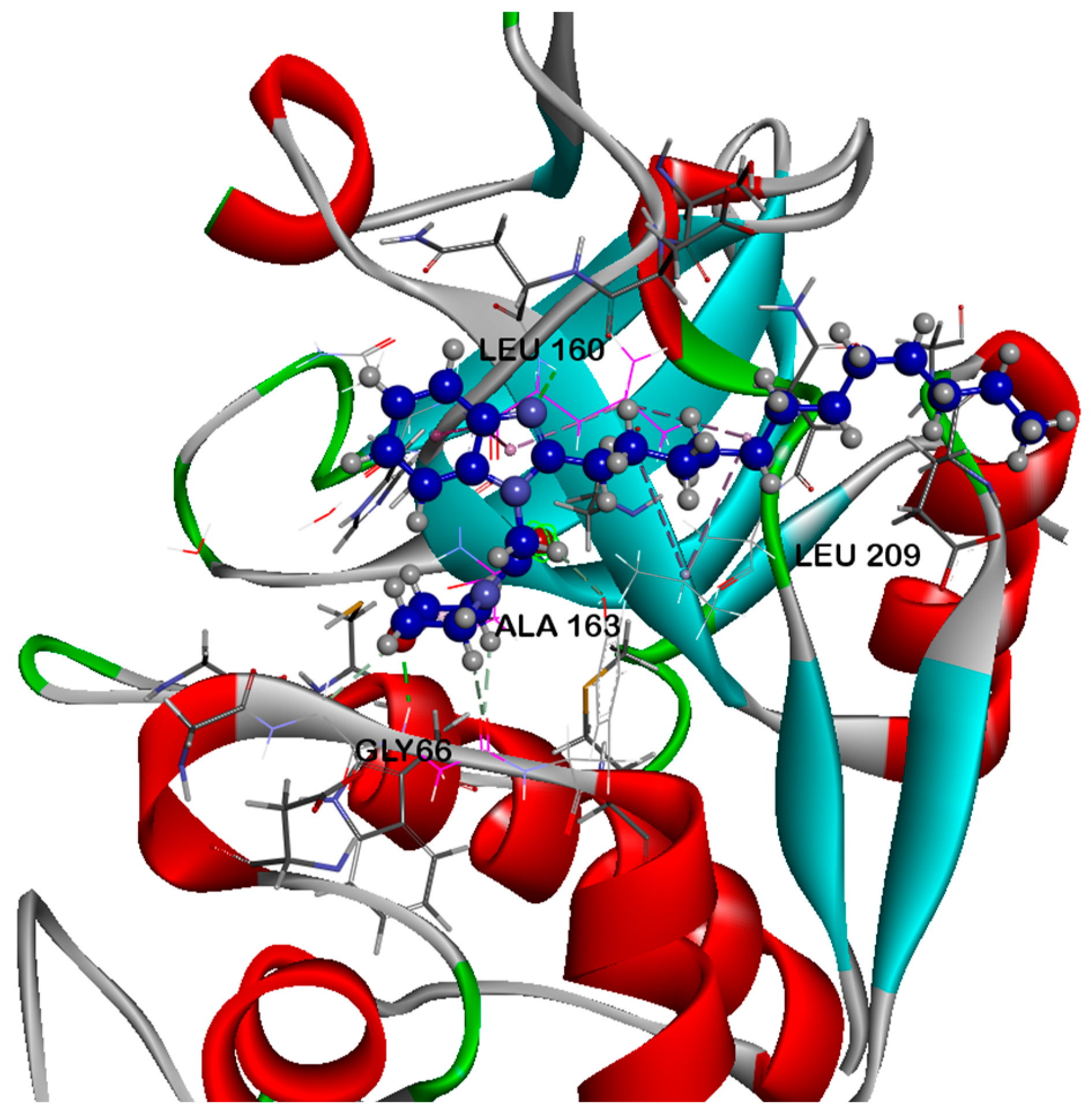

2.5.1. Docking Studies Analysis

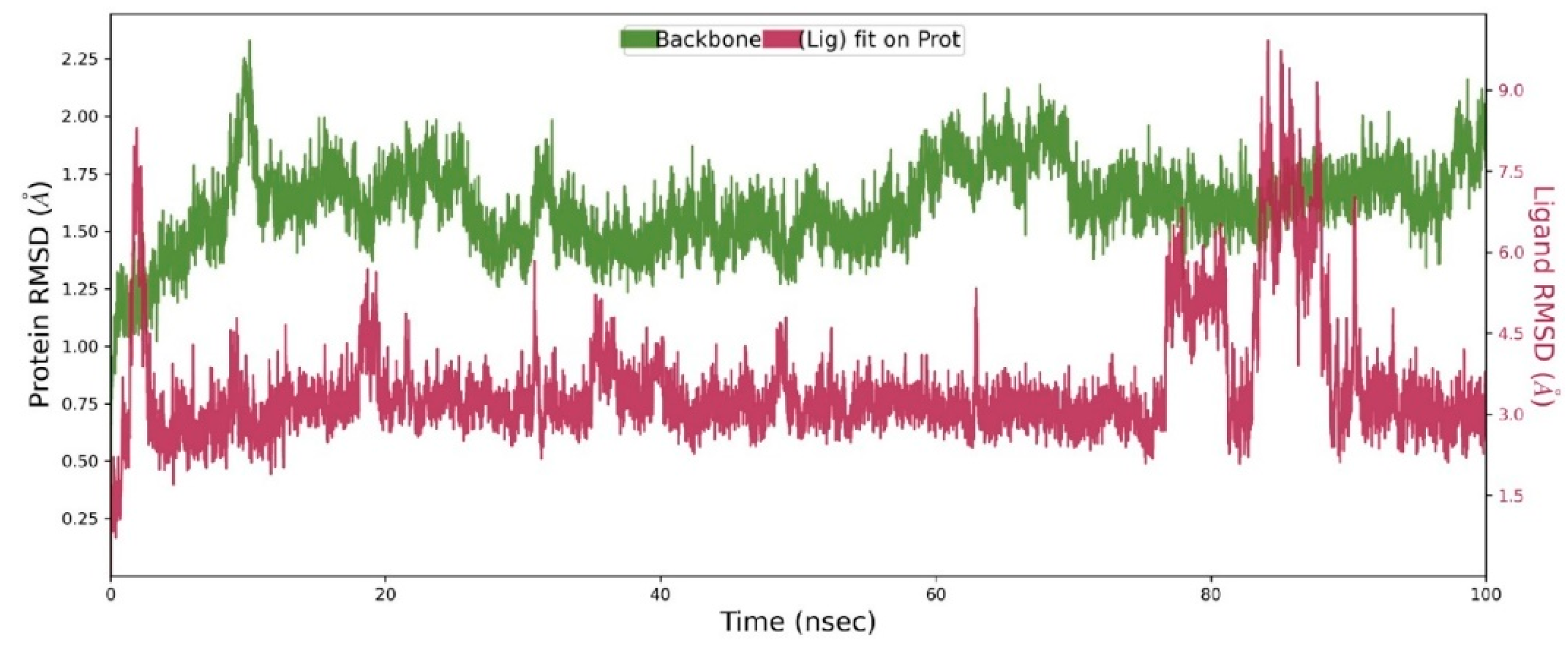

2.5.2. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemical Synthesis

3.1.1. General Procedures

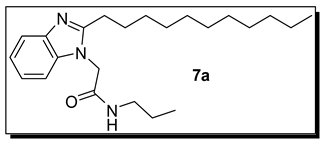

3.1.2. N-Propyl-2-(2-undecyl-1H-benzimidazol-1-yl)acetamide (7a)

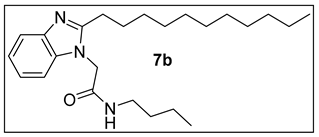

3.1.3.N-Butyl-2-(2-undecyl-1H-benzimidazol-1-yl)acetamide (7b).

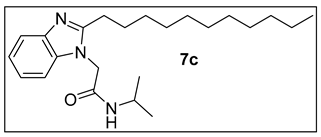

3.1.4.N-Isopropyl-2-(2-undecyl-1H-benzimidazol-1-yl)acetamide (7c).

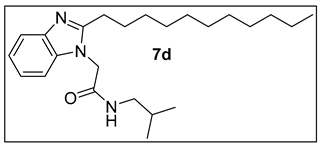

3.1.5.N-Isobutyl-2-(2-undecyl-1H-benzimidazol-1-yl)acetamide (7d).

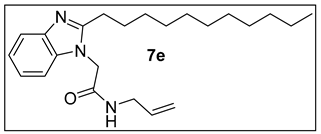

3.1.6.N-Allyl-2-(2-undecyl-1H-benzimidazol-1-yl)acetamide (7e).

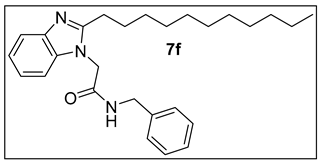

3.1.7.N-Benzyl-2-(2-undecyl-1H-benzimidazol-1-yl)acetamide (7f).

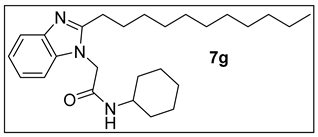

3.1.8. N-Cyclohexyl-2-(2-undecyl-1H-benzimidazol-1-yl)acetamide (7g).

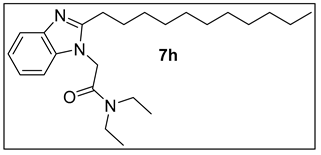

3.1.9. N,N-Diethyl-2-(2-undecyl-1H-benzimidazol-1-yl)acetamide (7h).

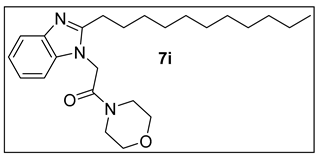

3.1.10. 1-Morpholino-2-(2-undecyl-1H-benzimidazol-1-yl)ethan-1-one (7i).

3.1.11. 1-(Piperidin-1-yl)-2-(2-undecyl-1H-benzimidazol-1-yl)ethan-1-one (7j).

3.2. Biological Experimentation

3.2.1. Cell Culture

3.2.2. MTT Assay

3.2.3. Ligand Lipophilic Efficiency (LLE)

3.3. In-Silico Studies

3.3.1. Docking Studies

3D Crystal Structure

3.3.2. Protein Preparation and Docking Validation

3.3.3. Ligand Library Preparation

3.3.4. Molecular Docking Using Induced-Fit Docking (IFD)

3.3.5. Molecular Dynamics Calculation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Deepak, K.G. , Vempati, R.; Nagaraju, G.P., Dasari, V.R., Nagini, S., Rao, D.N., Eds.; Malla, R.R. Tumor microenvironment: Challenges and opportunities in targeting metastasis of triple negative breast cancer. Pharmacological research 2020, 153, 104683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloane, B.F.; List, K.; Fingleton, B.; Matrisian, L. Proteases in Cancer: Significance for Invasion and Metastasis. Proteases: Structure and Function. [CrossRef]

- Gondi, C.S.; Rao, J.S. Cathepsin B as a cancer target. Expert opinion on therapeutic targets 2013, 17, 17,281–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seo, S.U.; Woo, S.M.; Im, S.S.; Jang, Y.; Han, E.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, H.; Lee, H.S.; Nam, J.O.; Gabrielson, E.; Min, K.J. Cathepsin D as a potential therapeutic target to enhance anticancer drug-induced apoptosis via RNF183-mediated destabilization of Bcl-xL in cancer cells. Cell Death & Disease. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.G.; Woo, S.M.; Seo, S.U.; Lee, C-H. ; Baek, M-C.; Jang, S.H.; Park, Z.Y.; Yook, S.; Nam, J-O.; Kwon, T.K. Cathepsin D promotes polarization of tumor-associated macrophages and metastasis through TGFBI-CCL20 signaling. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 2024, 56, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecaille, F.; Chazeirat, T.; Saidi, A.; Lalmanach, G. Cathepsin V: Molecular characteristics and significance in health and disease. Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 2022, 88, 101086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gall, C.L.; Bellahcene, A.; Bonnelye, E.; Gasser, J.A.; Castronovo, V.; Green, J.; Zimmermann, J.; Clezardin, P. A cathepsin K inhibitor reduces breast cancer–induced osteolysis and skeletal tumor burden. Cancer research 2007, 67, 9894–9902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, R.; Wu, Z.; Chu, H.Y.; Lu, J.; Lyu, A.; Liu, J.; Zhang, G. Cathepsin K: the action in and beyond bone. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2020, 8, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, L.T.; Wesolowski, G.A.; Leung, P.; Oballa, R.; Pickarski, M. Efficacy of a cathepsin K inhibitor in a preclinical model for prevention and treatment of breast cancer bone metastasis. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2014, 13, 2898–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Platt, M.O. Multiplex zymography captures stage-specific activity profiles of cathepsins K, L, and S in human breast, lung, and cervical cancer. Journal of translational medicine 2011, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, S.S.; Gouvea, I.E.; Silva, M.C.C.; Castro, E.D.; de Paula, C.A.A.; Okamoto, D.; Oliveira, L.; Peres, G.B.; Ottaiano, T.; Facina, G.; Nazario, A.C.P.; Campos, A.H. J.F.M.; Paredes-Gamer, E.J.; Juliano, M.; da Silva, I.D.C.G.; Oliva, M.L.V.; Girao, M.J. B C. Cathepsin K induces platelet dysfunction and affects cell signaling in breast cancer-molecularly distinct behavior of cathepsin K in breast cancer. BMC cancer. [CrossRef]

- Teitelbaum, S.L. Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science 2000, 289, 1504–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatani-Nakase, T.; Matsui, C.; Hosotani, M.; Omura, M.; Takahashi, K.; Nakase, I. Hypoxia enhances motility and EMT through the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE-1 in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Experimental cell research. 2022, 412, 113006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, K.; Jolly, M.K.; Balamurugan, K. Hypoxia, partial EMT and collective migration: Emerging culprits in metastasis. Translational oncology. 2020, 13, 100845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrakova, E.; Biryukov, M.; Troitskaya, O.; Gugin, P.; Milakhina, E.; Semenov, D.; Poletaeva, J.; Ryabchikova, E.; Novak, D.; Kryachkova, N.; Polyakova, A.; Zhilnikova, M.; Zakrevsky, D.; Schweigert, I.; Koval, O. Chloroquine enhances death in lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells exposed to cold atmospheric plasma jet. Cells. 2023, 12, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seker-Polat, F.; Degirmenci, N.P.; Solaroglu, I.; Bagci-Onder, T. Tumor cell infiltration into the brain in glioblastoma: from mechanisms to clinical perspectives. Cancers. 2022, 14, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, M.; Yang, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, S. The role of Cathepsin B in pathophysiologies of non-tumor and tumor tissues: a systematic review. Journal of Cancer. 2023, 14, 2344–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamyatnin, A.A.; Gregory, L.C.; Townsend, P.A.; Soond, S.M. Beyond basic research: the contribution of cathepsin B to cancer development, diagnosis, and therapy. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 2022, 26, 963–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qattan, M.Y.; Khan, M.I.; Alharbi, S.H.; Verma, A.K.; Al-Saeed, F.A.; Abduallah, A.M.; Al Areefy, A.A. Therapeutic importance of kaempferol in the treatment of cancer through the modulation of cell signalling pathways. Molecules. 2022, 27, 8864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanian S, Riahirad H, Pabarja A, Karimzadeh MR, Saeidi K. Kaempferol and docetaxel diminish side population and down-regulate some cancer stem cell markers in breast cancer cell line MCF-7. Biocell 2017, 41, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Bali, A.; Chaudhari, B.B. Synthesis of methanesulphonamido-benzimidazole derivatives as gastro-sparing anti-inflammatory agents with antioxidant effect. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2017, 27, 3007–3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerasamy, R.; Roy, A.; Karunakaran, R.; Rajak, H. Structure-Activity Relationship Analysis of Benzimidazoles as Emerging Anti-Inflammatory Agents: An Overview. Pharmaceuticals. 2021, 14, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, A.H.G.; Alam, T.; Imran, M. Design, molecular docking studies, in silico drug likeliness prediction and synthesis of some benzimidazole derivatives as antihypertensive agents. Indo American Journal of Pharmaceutical Science. 2017, 4, 926–936. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, M.; Husain, A.; Shaharyar, M.; Sarafroz, M. Anticancer activity of new compounds using benzimidazole as a scaffold. Anti-Cancer Agents in Medicinal Chemistry (Formerly Current Medicinal Chemistry-Anti-Cancer Agents) 2014, 14, 1003–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Deng, X.; Xiong, S.; Xiong, R.; Liu, J.; Zou, L.; Lei, X.; Cao, X.; Xie, Z.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, X.; Tang, G. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of chrysin benzimidazole derivatives as potential anticancer agents. Natural product research. 2018, 32, 2900–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, G.R.; Palma, E.; Marques, F.; Gano, L.; Oliveira, M.C.; Abrunhosa, A.; Miranda, H.V.; Outeiro, T.F.; Santos, I.; Paulo, A. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel 2-Aryl Benzimidazoles as Chemotherapeutic Agents. Journal of Heterocyclic Chemistry. 2017, 54, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, Y.M.; Omar, M.A.; Mahmoud, K.; Elhallouty, S.M.; El-Senousy, W.M.; Ali, M.M.; Mahmoud, A.E.; Abdel-Halim, A.H.; Soliman, S.M.; El Diwani, H.I. Synthesis, in vitro and in vivo antitumor and antiviral activity of novel 1-substituted benzimidazole derivatives. Journal of enzyme inhibition and medicinal chemistry. 2015, 30, 826–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archie, S.R.; Das, B.K.; Hossain, M.S.; Kumar, U.; Rouf, A.S. Synthesis and antioxidant activity of 2-substituted-5-nitro benzimidazole derivatives. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 9, 308–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, F.; Dey, B.K.; Sharma, K.; Chakraborty, A.; Kalita, P. Synthesis, antimicrobial and anthelmintic activity of some novel benzimidazole derivatives. Int. J. Drug Res. Tech. 2014, 4, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad, M.C.; Kumar, S.A.; Kumar, D.S.; Kumar, S.R.; Chandra, S.S.; Kumar, G.D. Designing and Synthesis of some Novel 2-Substituted Benzimidazole Derivatives and their Evaluation for Antimicrobial and Anthelmintic Activity. Asian Journal of Research in Chemistry, 2019, 12, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete-Vázquez, G.; Moreno-Diaz, H.; Aguirre-Crespo, F.; Leon-Rivera, I.; Villalobos-Molina, R.; Munoz-Muniz, O.; Estrada-Soto, S. Design, microwave-assisted synthesis, and spasmolytic activity of 2-(alkyloxyaryl)-1H-benzimidazole derivatives as constrained stilbene bioisosteres. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 2006, 16, 4169–4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gohary, N.S.; Shaaban, M.I. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a new series of benzimidazole derivatives as antimicrobial, antiquorum-sensing and antitumor agents. European journal of medicinal chemistry 2017, 131, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, L.R.; Avula, S.R.; Raj, S.; Srivastava, A.; Palnati, G.R.; Tripathi, C.K.M.; Pasupuleti, M.; Sashidhara, K.V. Coumarin–benzimidazole hybrids as a potent antimicrobial agent: synthesis and biological elevation. The Journal of antibiotics 2017, 70, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, Y.; Kaur, M.; Bansal, G. Antimicrobial potential of benzimidazole derived molecules. Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry 2019, 19, 624–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chintakunta, R.; Meka, G. Synthesis, in silico studies and antibacterial activity of some novel 2-substituted benzimidazole derivatives. Futur J Pharm Sci 2020, 6, 128–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

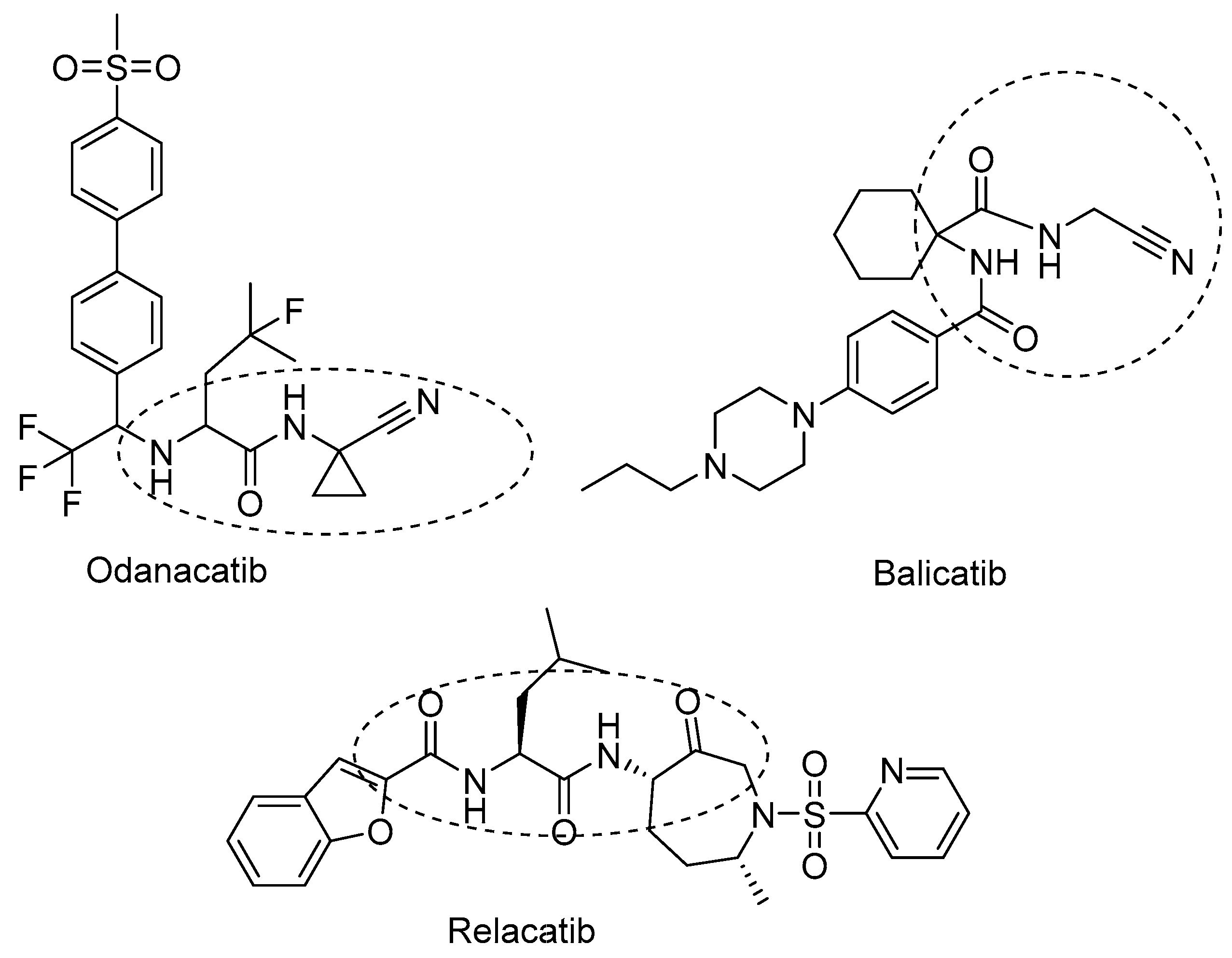

- Kara, M.; Oztas, E.; Ramazanogulları, R.; Kouretas, D.; Nepka, C.; Tsatsakis, A.M.; Veskoukis, A.S. Benomyl, a benzimidazole fungicide, induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in neural cells. Toxicology reports 2020, 7, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreikorn, B.A.; Owen, W.J. Fungicides, Agricultural. Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.L.; Ouyang, L.; Yu, N.N.; Sun, Z.H.; Gui, Z.K.; Niu, Y.L.; He, Q.Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. Histone deacetylase inhibitor pracinostat suppresses colorectal cancer by inducing CDK5-Drp1 signaling-mediated peripheral mitofission. Journal of pharmaceutical analysis 2023, 13, 1168–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedky, N.K.; Hamdan, A.A.; Emad, S.; Allam, A.L.; Ali, M.; Tolba, M.F. Insights into the therapeutic potential of histone deacetylase inhibitor/immunotherapy combination regimens in solid tumors. Clinical and Translational Oncology 2022, 24, 1262–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weide, R.; Hess, G.; Koppler, H.; Heymanns, J.; Thomalla, J.; Aldaoud, A.; Losem, C.; Schmitz, S.; Haak, U.; Huber, C.; Unterhalt, M.; Hiddemann, W.; Dreyling, M. High anti-lymphoma activity of bendamustine/mitoxantrone/rituximab in rituximab pretreated relapsed or refractory indolent lymphomas and mantle cell lymphomas. A multicenter phase II study of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG). Leukemia & lymphoma 2007, 48, 1299–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021. hdl: 10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML.

- Testa, B.; Crivori, P.; Reist, M.; Carrupt, P.A. The influence of lipophilicity on the pharmacokinetic behavior of drugs: Concepts and examples. Perspectives in Drug Discovery and Design 2000, 19, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morak-Młodawska, B.; Jelen, M.; Martula, E.; Korlacki, R. Study of Lipophilicity and ADME Properties of 1,9-Diazaphenothiazines with Anticancer Action. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24, 6970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathalla, W. Synthesis of methyl 2-[2-(4-phenyl [1, 2, 4] triazolo-[4, 3-a] quinoxalin-1-ylsulfanyl) acetamido] alkanoates and their N-regioisomeric analogs. Chemistry of Heterocyclic Compounds 2015, 51, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, E.F.; Ali, I.A.I.; Fathalla, W.; Alsheikh, A.A.; El Tamneya, E.S. Synthesis of methyl [3-alkyl-2-(2, 4-dioxo-3, 4-dihydro-2H-quinazolin-1-yl)-acetamido] alkanoate. ARKIVOC: Online Journal of Organic Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- Walid, F.; Pavel, P. Synthesis of methyl 2-[(1, 2-dihydro-4-hydroxy-2-oxo-1-phenylquinolin-3-yl) carbonylamino] alkanoates and methyl 2-[2-((1, 2-dihydro-4-hydroxy-2-oxo-1-phenylquinolin-3-yl) carbonyl-amino) alkanamido] alkanoate. ARKIVOC: Online Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2017, 2017, 158–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathalla, W.; Pazdera, P. Convenient Synthesis of Piperazine Substituted Quinolones. J. Heterocyclic Chem 2017, 54, 3481–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Rayes, S.M.; Aboelmagd, A.; Gomaa, M.S.; Ali, I.A.; Fathalla, W.; Pottoo, F.H.; Khan, F.A. Convenient Synthesis and Anticancer Activity of Methyl 2-[3-(3-Phenyl-quinoxalin-2-ylsulfanyl) propanamido] alkanoates and N-Alkyl 3-((3-Phenyl-quinoxalin-2-yl) sulfanyl) propanamides. ACS omega 2019, 4, 18555–18566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboelmagd, A.; Alotaibi, S.H.; El Rayes, S.M.; Elsayed, G.M.; Ali, I.A.; Fathalla, W.; Pottoo, F.H.; Khan, F.A. Synthesis and Anti proliferative Activity of New N-Pentylquinoxaline carboxamides and Their O-Regioisomer. Chemistry Select 2020, 5, 13439–13453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelmagd, A.; El Rayes, S.M.; Gomaa, M.S.; Ali, I.A.; Fathalla, W.; Pottoo, F.H.; Khan, F.A.; Khalifa, M.E. The synthesis and antiproliferative activity of new N-allyl quinoxalinecarboxamides and their O-regioisomers. New Journal of Chemistry 2021, 45, 831–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irby, D.; Du, C.; Li, F. Lipid–drug conjugate for enhancing drug delivery. Molecular pharmaceutics 2017, 14, 1325–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Mei, L.; Quach, T.; Porter, C.; Trevaskis, N. Lipophilic conjugates of drugs: a tool to improve drug pharmacokinetic and therapeutic profiles. Pharmaceutical Research 2021, 38, 1497–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.; Jatyan, R.; Mittal, A.; Mahato, R.I.; Chitkara, D. Opportunities and challenges of fatty acid conjugated therapeutics. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids 2021, 236, 105053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong Yao, Hong-Ping Wu, Jing Chang, Qi Lin, Tai-Bao Wei and You-Ming Zhang. A carboxylic acid functionalized benzimidazole-based supramolecular gel with multi-stimuli responsive properties. New J. Chem., 2016, 40, 4940–4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, M.; Hou, X.; Kuhn, M.; Wager, T. T.; Kauffman, G. W.; Verhoest, P. R. Quantitative assessment of the impact of fluorine substitution on P-Glycoprotein (P-GP) mediated efflux, permeability, lipophilicity, and metabolic stability. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2016, 59, 5284–5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meanwell, N. A. Improving Drug Design: An Update on Recent Applications of Efficiency Metrics, Strategies for Replacing Problematic Elements, and Compounds in Nontraditional Drug Space. Chemical Research in Toxicology 2016, 29, 564–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.L.G.; Andricopulo, A.D. ADMET modeling approaches in drug discovery. Drug discovery today 2019, 24, 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelley, J.C.; Cholleti, A.; Frye, L.L.; Greenwood, J.R.; Timlin, M.R.; Uchimaya, M. Epik: a software program for pKa prediction and protonation state generation for drug-like molecules. Journal of computer-aided molecular design 2007, 21, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomaa, M.; Gad, W.; Hussein, D.; Pottoo, F.H.; Tawfeeq, N.; Alturki, M.; Alfahad, D.; Alanazi, R.; Salama, I.; Aziz, M.; et al. Sulfadiazine Exerts Potential Anticancer Effect in HepG2 and MCF7 Cells by Inhibiting TNFα, IL1b, COX-1, COX-2, 5-LOX Gene Expression: Evidence from In Vitro and Computational Studies. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Khzem, A.H.; Shoaib, T.H.; Mukhtar, R.M.; Alturki, M.S.; Gomaa, M.S.; Hussein, D.; Tawfeeq, N.; Bano, M.; Sarafroz, M.; Alzahrani, R.; et al. Repurposing FDA-Approved Agents to Develop a Prototype Helicobacter pylori Shikimate Kinase (HPSK) Inhibitor: A Computational Approach Using Virtual Screening, MM-GBSA Calculations, MD Simulations, and DFT Analysis. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong Yao, Jiao Wang, Shan-Shan Song, Yan-Qing Fan, Xiao-Wen Guan, Qi Zhou, Tai-Bao Wei, Qi Lin and You-Ming Zhang. A novel supramolecular AIE gel acts as a multi-analyte sensor array. New J. Chem. 1805. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; Ahmad, R.; Alanazi, A.M.; Alsaif, N.; Abdullah, M.; Wani, T.A.; Bhat, M.A. Determination of anticancer potential of a novel pharmacoloFgically active thiosemicarbazone derivative against colorectal cancer cell lines. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2022, 30, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A.L.; Keseri, G.M.; Leeson, P.D.; Rees, D.C.; Reynolds, C.H. The role of ligand efficiency metrics in drug discovery. Nature reviews Drug discovery 2014, 13, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, I.; Pleban, K.; Rinner, U.; Chiba, P.; Ecker, G. F. Structure–Activity Relationships, Ligand Efficiency, and Lipophilic Efficiency Profiles of Benzophenone-Type Inhibitors of the Multidrug Transporter P-Glycoprotein. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 3261–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeson, P.D.; Springthorpe, B. The influence of drug-like concepts on decision-making in medicinal chemistry. Nature reviews Drug discovery 2007, 6, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryckmans, T.; Edwards, M.P.; Horne, V.A.; Correia, A.M.; Owen, D.R.; Thompson, L.R.; Tran, I.; Tutt, M.F.; Young, T. Rapid Assessment of a Novel Series of Selective CB2 Agonists Using Parallel Synthesis Protocols: A Lipophilic Efficiency (LipE) Analysis. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2009, 19, 4406–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

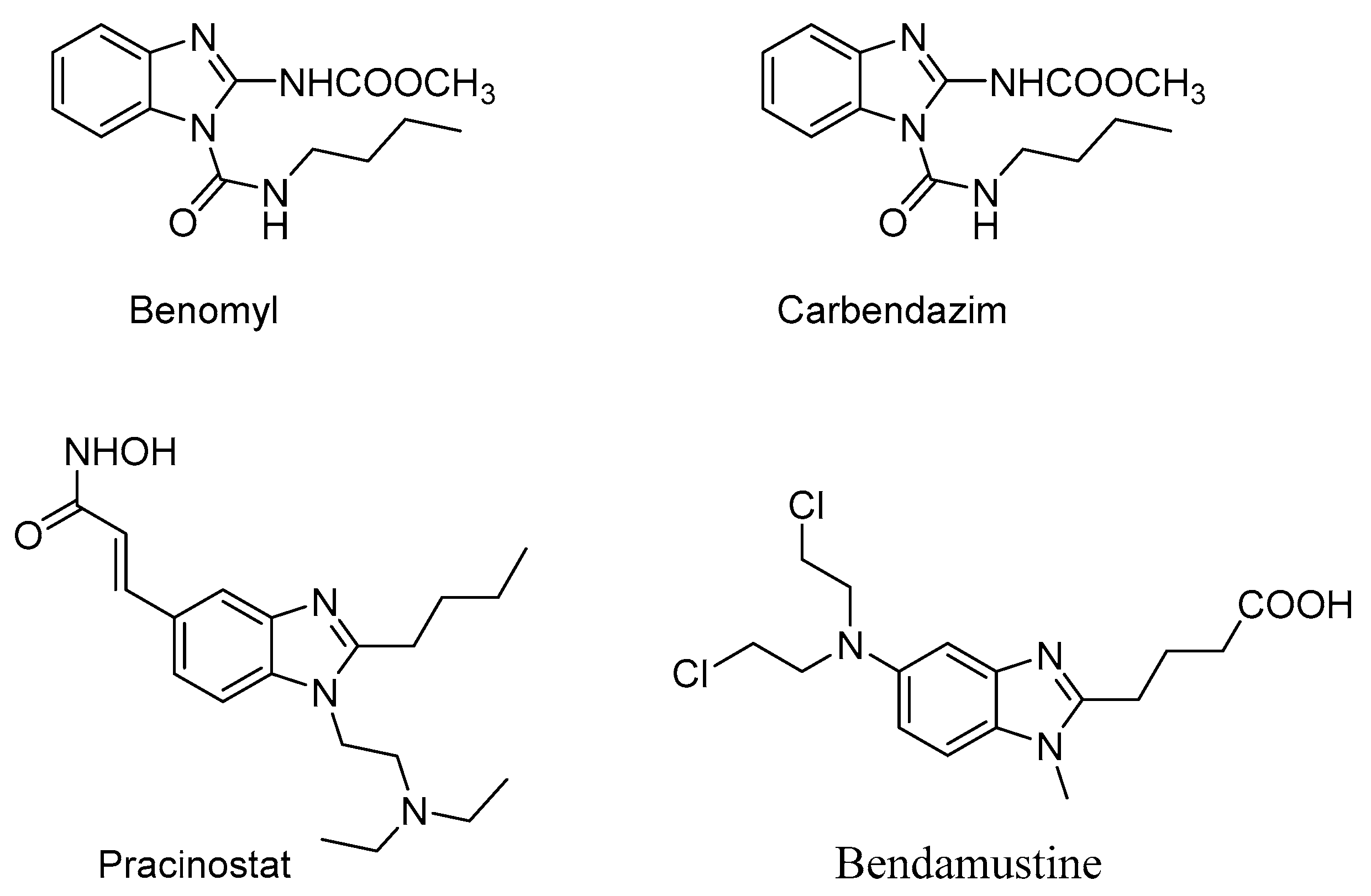

| Compound | IC50 (μg/ml) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A549 | MDA-MB 231 | MCF7 | U87 | |

| 7a | 661 | 38 | 120 | 95 |

| 7b | 603 | 465 | 464 | 450 |

| 7c | 300 | 106 | 115 | 160 |

| 7d | 841 | 121 | 371 | 150 |

| 7e | 555 | 421 | 484 | 300 |

| 7f | 94 | 107 | 71 | 95 |

| 7g | 117 | 97 | 370 | 250 |

| 7h | 37 | 17 | 37 | 80 |

| 7i | 30 | 27 | 14 | 17 |

| 7j | 187 | 67 | 368 | 250 |

| pIC50 | ClogP | LLE1 | pIC50 | ClogP | LLE1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound/ Cell line |

A549 | Compound/ Cell line |

MCF7 | ||||

| 7a | 6.75 | 5.41 | 1.34 | 7a | 6.49 | 5.41 | 1.08 |

| 7h | 7.02 | 5.54 | 1.48 | 7h | 7.02 | 5.54 | 1.48 |

| 7i | 7.12 | 4.77 | 2.35 | 7i | 7.46 | 4.77 | 2.69 |

| 7j | 6.33 | 5.63 | 0.70 | 7j | 6.03 | 5.63 | 0.40 |

| MDA-MB 231 | U87 | ||||||

| 7a | 6.99 | 5.41 | 1.58 | 7a | 6.59 | 5.41 | 1.18 |

| 7h | 7.36 | 5.54 | 1.82 | 7h | 6.68 | 5.54 | 1.14 |

| 7i | 7.17 | 4.77 | 2.40 | 7i | 7.37 | 4.77 | 2.60 |

| 7j | 6.77 | 5.63 | 1.14 | 7j | 6.20 | 5.63 | 0.57 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).