1. Introduction

Due to the superior characteristics and commercial availability, silicon carbide (SiC) devices are gradually finding their applications. Compared to silicon (Si) counterparts, SiC devices have faster switching speed (shorter switching time), higher voltage blocking capability and higher temperature performance [

1,

2]. The switching frequency of hard-switched SiC inverters can reach 100kHz and the rise time of the switching voltage pulse can be only 10s of nanoseconds [

3]. In contrast, the switching frequency of Si IGBT inverters is normally below 20kHz and the switching time is in the order of several hundred nanoseconds. Higher switching frequency can reduce the filtering components and the faster switching speed can reduce the switching loss hence the cooling requirement [

4,

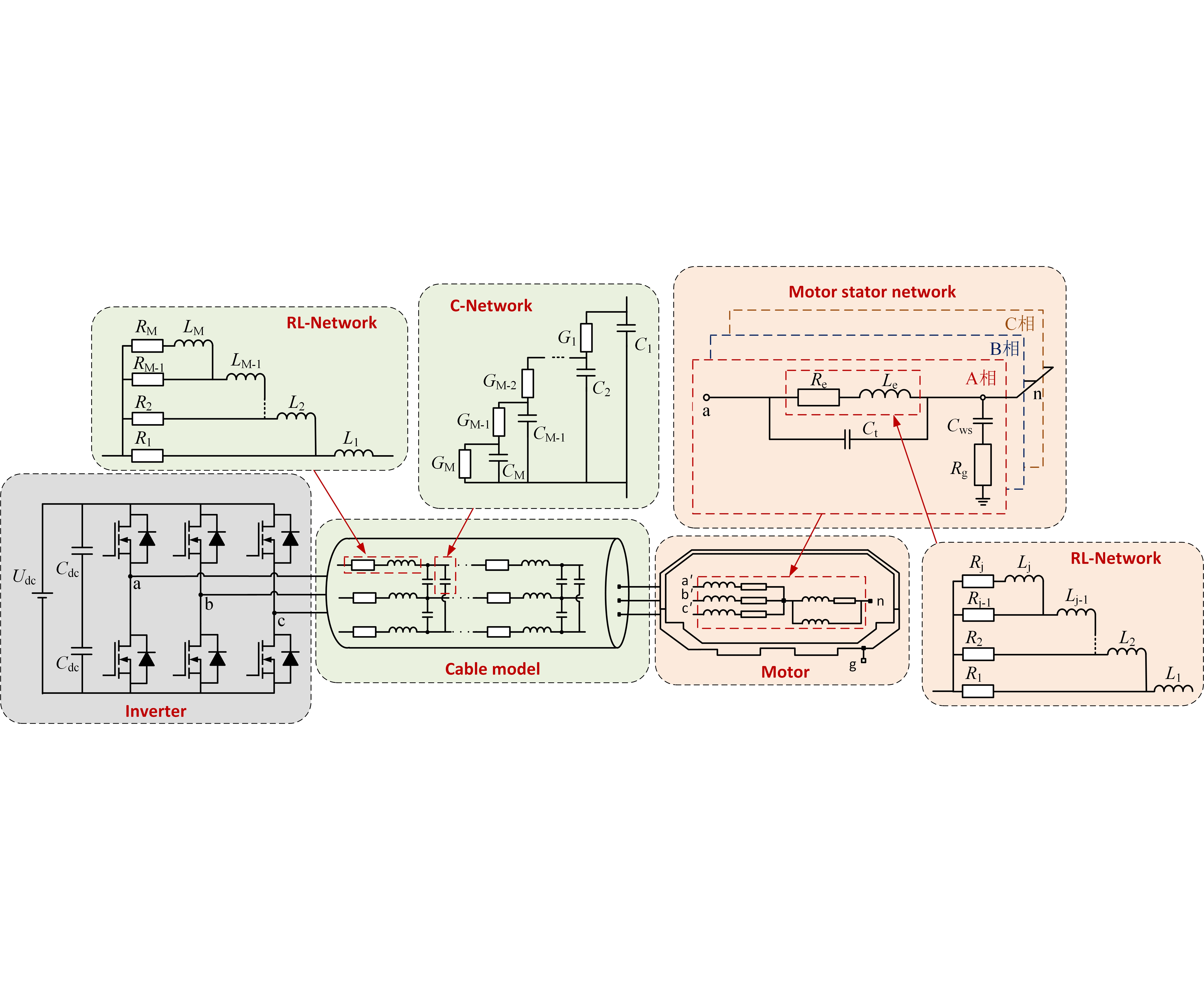

5]. The adoption of SiC devices in motor drive systems can improve higher power density and efficiency, which is favored in applications such as more electric aircraft, electric vehicle, etc. The basic structure of an inverter-fed AC motor drive system with connecting cables is shown in

Figure 1.

To protect motor winding insulation, the slew rate of the motor input voltage is suggested to be limited to 500V/

μs by the standard, i.e. MG1 of National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) for general motor [

6]. In [

7], the switching behaviors of a 1700V, 50A SiC MOSFET are tested and analyzed. The

dv/dt of the output voltage exceed 36kV/

μs with a 5Ω gate resistance. The very high

dv/dt will lead to overvoltage at motor terminals, which will have clear negative effects on the motors, e.g. causing motor winding insulation and bearing failure [

8]. Furthermore, under higher frequencies, the overvoltage at motor terminals will be unevenly distributed among the winding turns, where the first several turns will bear most of the overvoltage during the transient of the PWM pulse, causing higher stress for the first several turns [

9].

To analyze the above issues, suitable models need to be developed to analyze the negative effects of fast-switching SiC converters on motors, especially the overvoltage phenomenon. Motor terminal overvoltage need to be considered for selecting system configuration, filter design and selecting the insulation grade. The main factors affecting the motor overvoltage are the rise time of the inverter output voltage pulses, the length of the cable connecting the inverter and the motor, and the impedance mismatch between the characteristic impedance of the cable and the motor [

10]. Due to the sharp edges of SiC inverter output voltages, the critical cable length for inducing overvoltage (voltage doubling) will be much shorter compared with that using relatively slow Si IGBT inverters. In other words, for similar conditions, the motor will experience higher overvoltage when the motor is driven by a SiC MOSFETs inverter.

At present, there are a few studies focusing on the negative effects of wide bandgap (WBG) devices on motors. In [

11], the reflected wave phenomenon with gallium nitride (GaN) HEMTs, SiC MOSFETs and Si MOSFETs are studied and compared. It is found that the motor overvoltage is more likely to happen under shorter rise time of the inverter output voltage. However, the main factors affecting the motor overvoltage with a cable connected to an AC motor and a SiC inverter is not studied in detail. The motor overvoltage using SiC MOSFETs under different length of cables is studied in [

12,

13]. As a conclusion, the motor overvoltage (smaller than twice the DC input voltage (<2Vdc)) can occur with 2.3 meters-23 meters of cable length due to SiC MOSFETs short rise time. But in these papers, the effect of different rise times (10s of nanoseconds) on motor overvoltage are not studied in detail.

In order to analyze the motor overvoltage at high frequencies systematically and accurately, a high-frequency cable model needs to be established [

14,

15]. Regarding cable modelling, the distributed parameter model provides more accurate results than the lumped parameter model for the high-frequency behavior [

16]. Long cable models for analyzing the motor overvoltage phenomenon have been widely studied [

17,

19]. The traditional multiple π-section model was proposed in [

17,

18] and the lossy transmission line model was also intensively studied in [

20]. However, these traditional lumped cable models cannot predict the motor overvoltage with SiC system accurately and the parameters of these models are set to be constant. In other words, these models are frequency independent. To address the frequency-dependent parameters, a RL-ladder circuit is added into the cable equivalent circuit to represent the skin effect, etc [

21]. This method could match the high frequency characteristics of the cable given the impedance of the RL-ladder circuit is frequency dependent. However, the number of the ladder branch and the number of cells of unit length will influence the accuracy of the prediction, so appropriate cells and branches are important in the ladder model and the computation time is a concern under high number of cells and branches to address the high frequency behavior. [

22] extracted the cable parameters by using an open and short circuit testing method (low frequency excitation), and the cable model with low frequency response is stablished.

This paper quantitatively analyzes the factors influencing the motor overvoltage by the wave reflection theory when using SiC inverters. A high-frequency distributed parameter model of the cable is established, and the cable impedance is modeled as frequency dependent. The model parameters can be simply obtained by measurement using an impedance analyzer. This model can accurately predict the overvoltage for the SiC inverter-cable-motor system. The influencing factors including rise time and cable length on motor overvoltage with SiC inverter are studied in detail. This paper aims to provide a timely reference for analyzing and understanding the negative effects of fast-switching SiC inverters regarding motor voltage.

2. Wave Reflection Theory for Overvoltage Prediction

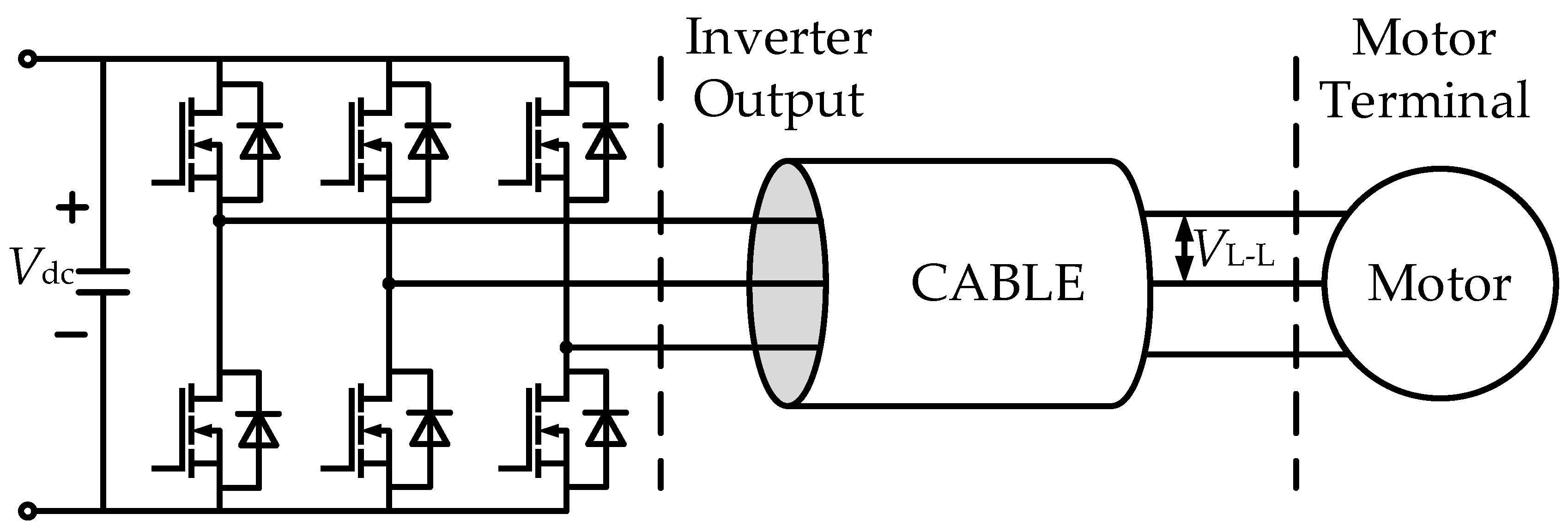

The structure of a variable speed motor drive system is shown in

Figure 1. The inverter is connected with the motor through the cable (inverter-cable-motor system). In this topology, there are three main factors influencing the overvoltage on the motor, which are the cable length, the rise time of inverter output voltage pulses, and the characteristic impedance mismatch between the cable and the motor.

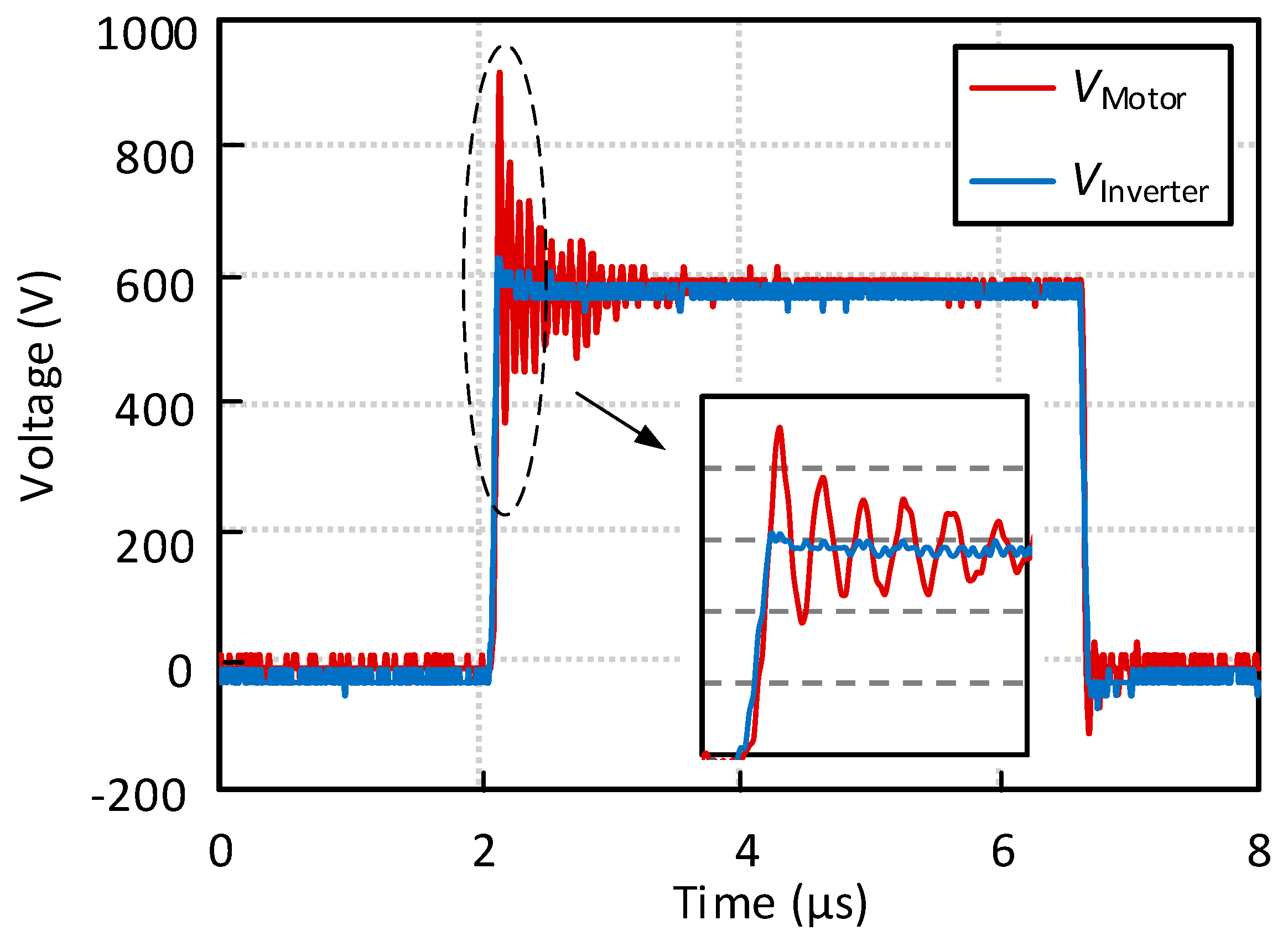

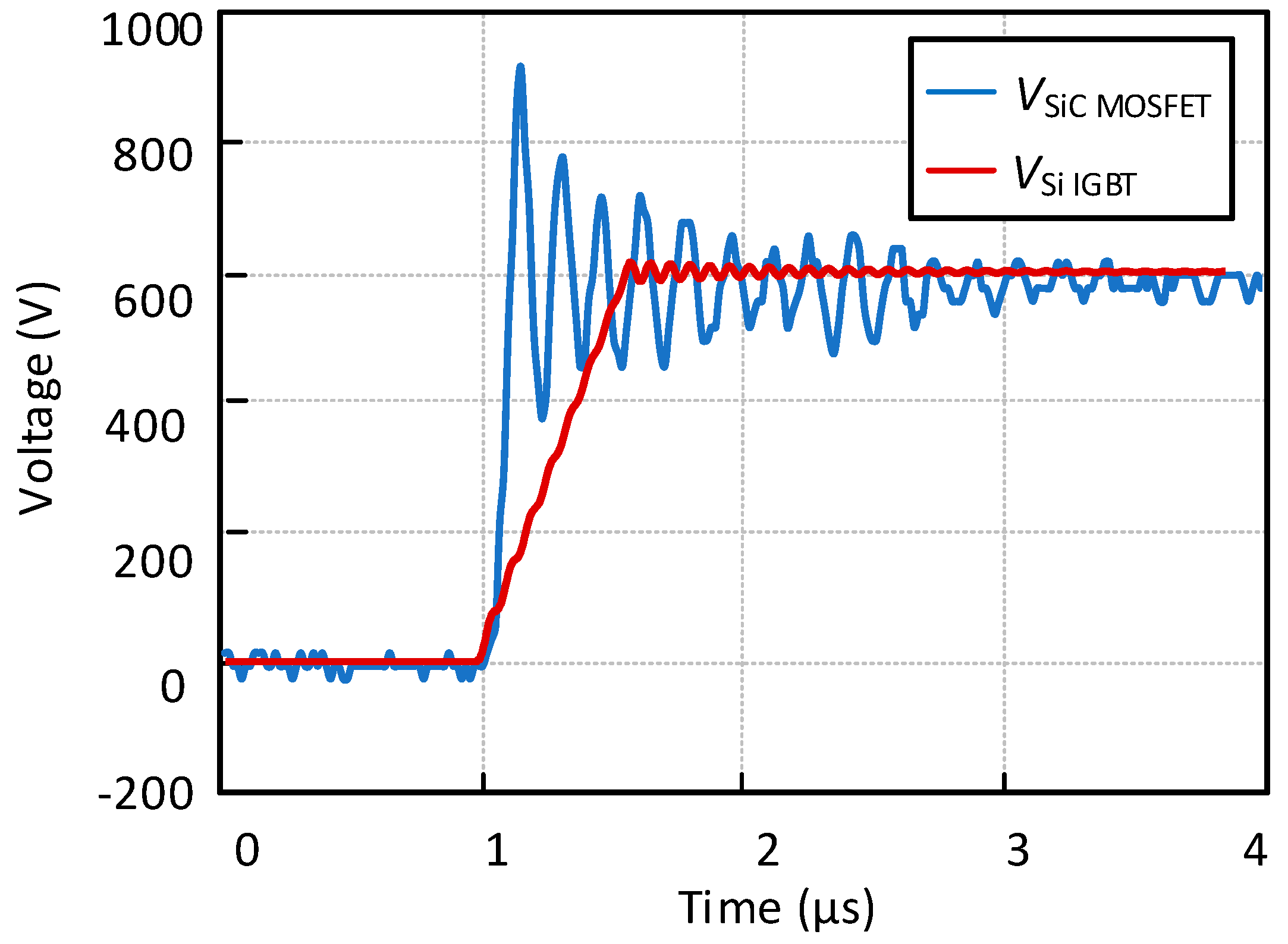

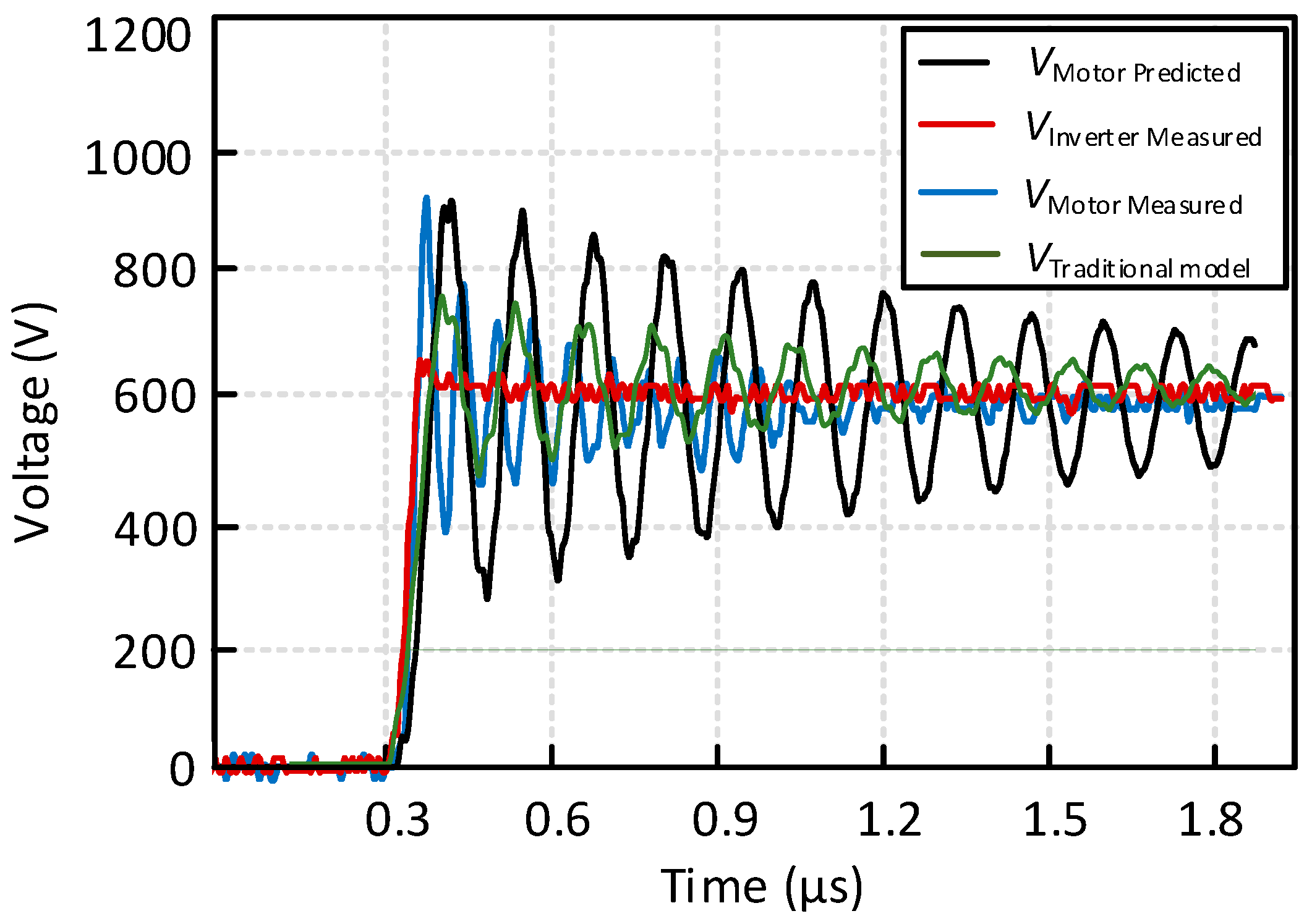

Figure 2 shows a measured example of the motor overvoltage, where the SiC MOSFET inverter output voltage (

VInverter) is a square wave (600V) and there is obvious overvoltage and oscillations at the motor terminal (

VMotor). It can be seen from

Figure 2 that when the inverter dc-link voltage

Vdc is 600 V, the peak phase-to-phase (line) voltage of the motor can reach as high as 920V. It should be noted that the cable length is 2 meters in this test.

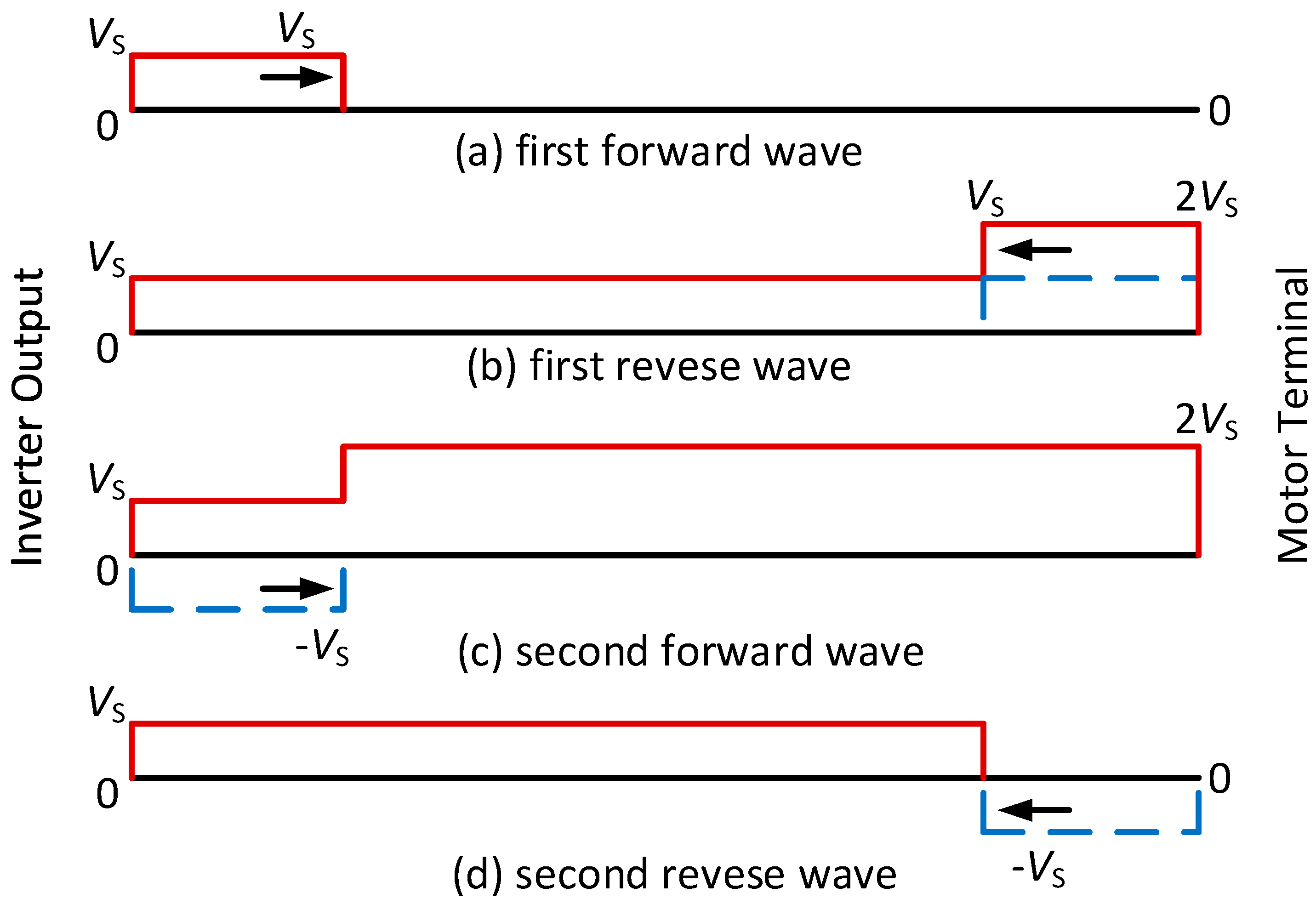

Figure 3 shows the reflection process of a traveling wave in the cable [

23].

Figure 3(a) shows the voltage pulse traveling from the inverter output to the motor terminal which is called the first forward wave.

Figure 3(b) shows the reflection of the first forward wave (

VS) after arriving at the motor terminal. The motor terminal reflection coefficient is approximately equal to one since the load impedance of the motor is much higher than the impedance of the cable. The first forward wave will generate a traveling wave with the same amplitude (+

VS) from the motor terminal back to the inverter output, which is called the first reverse wave. If the reflection coefficient is equal to one and the cable is long enough, the peak value of the voltage at the motor terminal is the superposition of the forward and reverse wave, presenting twice

VS (voltage doubling). The motor overvoltage magnitude will be less than 2

Vs with smaller reflection coefficient and shorter cable length.

Figure 3(c) shows the second forward wave from the reflection of the first reverse wave at the inverter side. The inverter can be seen as a short circuit where the inverter can be modelled as a voltage source. Therefore, the reflection coefficient of the inverter output is -1. Hence, the first reverse wave will generate a traveling wave with the amplitude of -

VS from inverter output back to the motor terminal, which is called the second forward wave.

Figure 3(d) shows the motor voltage drops to 0 with the superposition of the second forward wave and second reverse wave. A forward wave will reflect three times in a cycle and then reduce to 0 by the wave reflection theory. Actually, a forward wave will reflect many times in a cycle which induces the voltage oscillation and then reduce to 0, since the reflection coefficient is less than 1.

For long cables, the forward wave will generate a reflection wave after arriving at the motor terminal and the magnitude will be scaled by the reflection coefficient. However, the motor overvoltage is affected by the rise time of inverter output voltage with shorter cables. The transmission of the traveling waves along the cable from the inverter output to the motor terminal takes time, which is defined as

tt. Also, the voltage pulse has a rise time of

tr. The motor overvoltage only occurs when tr is less than the propagation time

tt. It can be seen from

Figure 3 that the voltage pulse has reflected through the cable three times in a cycle. Hence the motor terminal overvoltage peak (

Vpeak) can be given by (1) and (2) respectively according to the relationship between the propagation time

tt and 1/3 of the rise time

tr [

23].

where

Vdc is the magnitude of the forward wave and is equal to the inverter dc-link voltage, l is the cable length,

v is the pulse velocity in the cable,

N is the reflection coefficient at the motor terminal which can be expressed as the function of the cable impedance (

Zc) and the motor impedance (

Zm) as shown in (3) and (4).

In (4), L0 and Co are inductance and capacitance of per unit cable length, respectively.

However, the cable impedance

Zc is closely related to the cable length, structure, material and parasitic parameters. Hence, it was found that

Zc is a relatively constant value with a 2m 3 core XLPE cable, around 62Ω. The value of the motor impedance

Zm can be approximated according to empirical formula (around 3500Ω for a 7.5kW motor) [

24]. It should be noted that this traditional formula cannot describe the frequency response of the cable-motor model. In other words, the impedance calculated by this formula cannot represent the true impedance value under high-frequency excitation.

The voltage pulse propagation time (

tt) can be expressed as the function of l and v as shown in (5).

The pulse propagation velocity (

v) relates to the inductance (

Lc) and capacitance (

Cc) of per unit cable length [

25]. Besides, the pulse propagation velocity can also be defined as a function of the permeability (

µ) and permittivity (

ε) of the dielectric material between conductors [

26]. Hence, v can be expressed as (6).

It can be seen from (1) that the inverter is more likely to generate double overvoltage (2

Vdc) when the

tr is less than 3 times of

tt. Submitting (5) into (2), the ratio of 3

tt to

tr is going to be less than 1 when

tr > 3

tt as (7).

Therefore, the motor overvoltage will reduce significantly when the rise time of the voltage pulse is longer. In other words, the motor overvoltage will be less than twice

Vdc because of the longer rise time. Compared to Si IGBT inverters, the motor overvoltage using SiC MOSFETs inverters is higher due to the shorter rise time.

Figure 4 shows an example where the motor overvoltage under a SiC MOSFET inverter and a Si IGBT inverter is compared. As seen, the motor overvoltage reaches 960V with the inverter SiC and a dc-link voltage of 600V. In contrast, with the Si IGBT inverter, there is very little overvoltage. A 2 meters cable is adopted in these two systems and the rise time for the SiC MOSFET inverter is 34ns versus 400ns for the Si IGBT inverter. Therefore, the motor overvoltage with the SiC inverter is more serious compared to the Si IGBT inverter with the same short cable.

Table 1 shows the rise time and the corresponding cable critical length for inducing the double voltage, which is calculated according to (2). The critical cable length reduces with the decrease of the rise time. As seen, for a typical rise time of 40ns of the SiC MOSFETs, the critical cable length is only 1.84m, which is much shorter than that with Si IGBTs (rise time 100 ~400ns), which is normally longer than 10m. Using

Table 1, the cable length can be preliminary adjusted according to the rise time to reduce the magnitude of overvoltage where possible.

However, the amplitude of the motor overvoltage cannot be accurately calculated with SiC device system by (2).

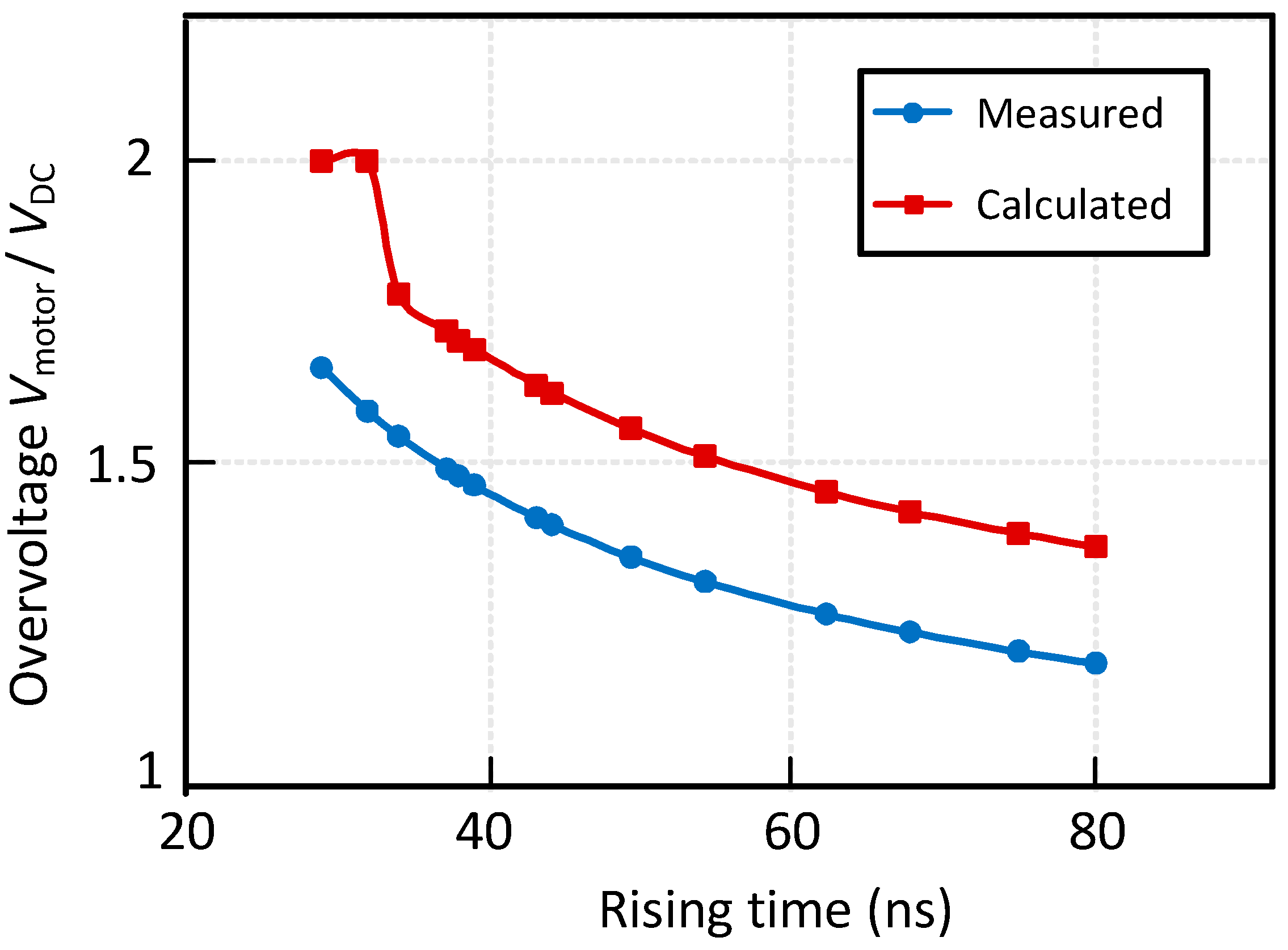

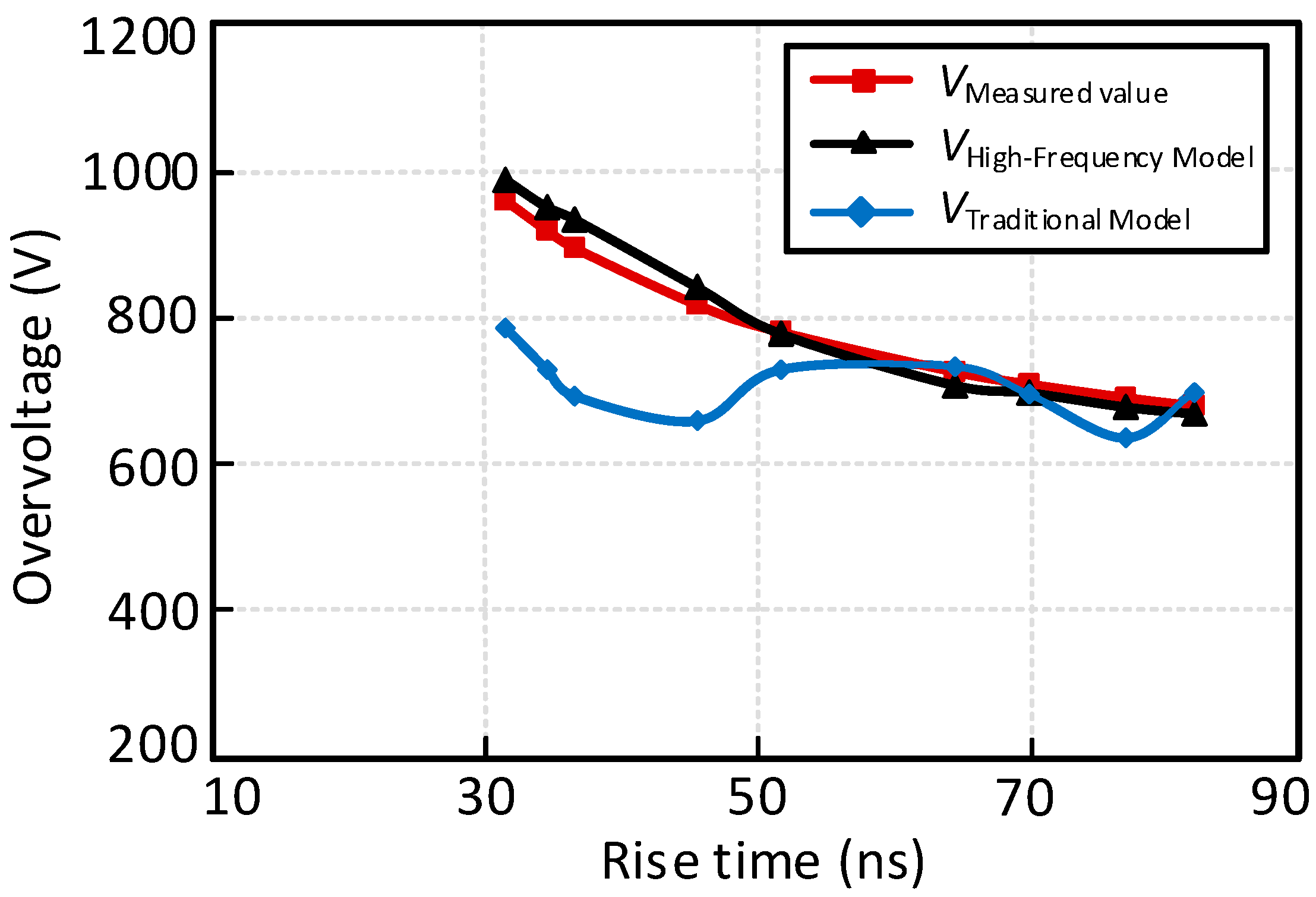

Figure 5 shows the ratio between motor terminal voltage (

VM) and inverter output voltage (

VDC) with various rise times measured in experiment and calculated using equation (2). As seen, the overvoltage reduces with the increase of rise time. Although the trend of the measure overvoltage ratio agrees with the that calculated from (2), there are clear differences in the magnitude. This is because the inaccuracy

Zc for calculating equation (2) and (3), where the high frequency excitation could affect the impedance of the cable. In order to accurately predict the motor terminal overvoltage with the SiC inverter, it is necessary to establish a suitable cable model at high frequencies rather than approximately calculating the impedance of the cable by (4).

3. High-Frequency Cable Modelling

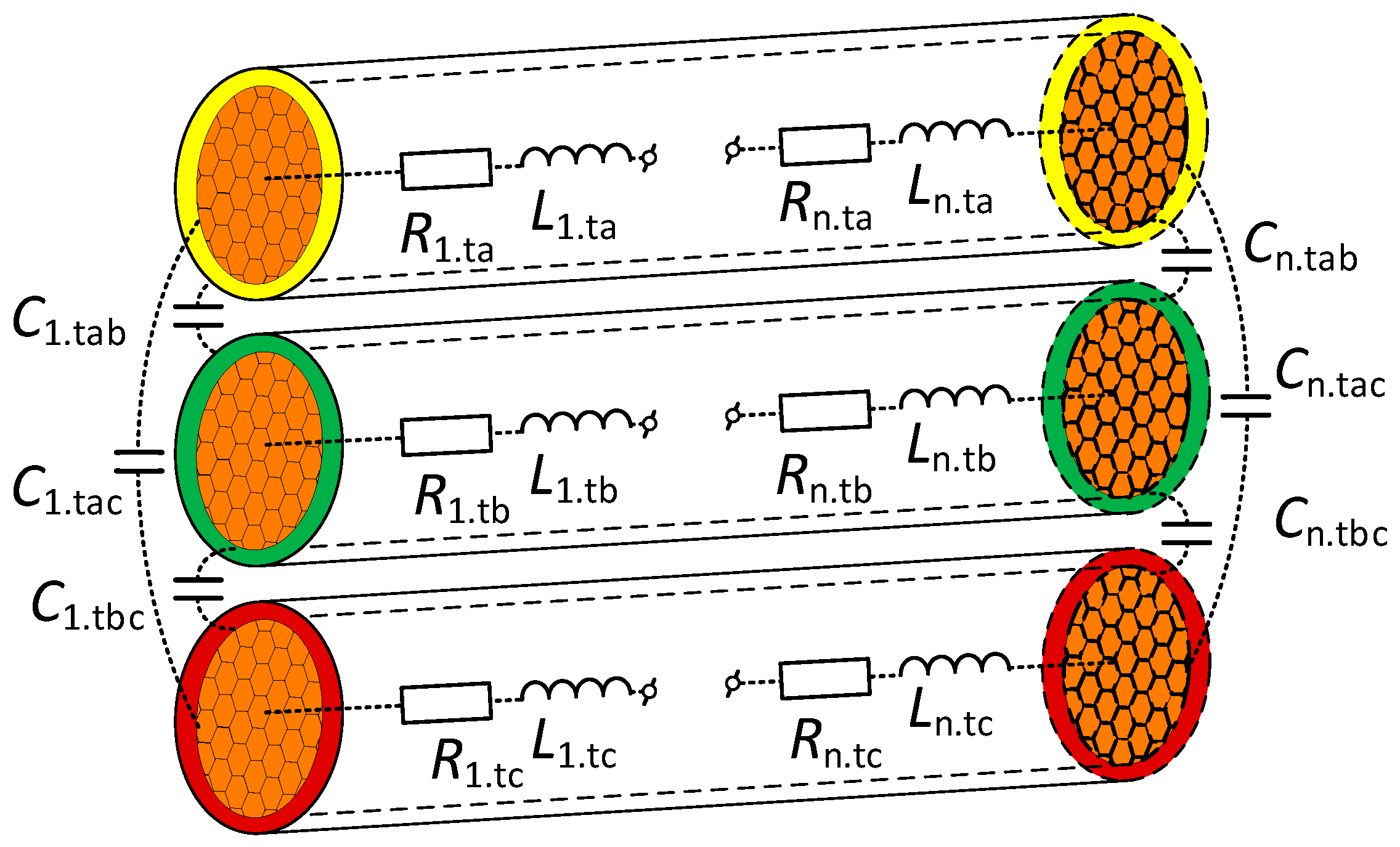

An accurate high-frequency cable model is critical for studying the overvoltage and voltage oscillation which is determined by the cable length, the cable structure, and the insulation material. Normally, the parasitic parameters in existing cable models are mainly studied under low-frequency conditions. The high frequency effects of the cable parasitic parameters are often not considered. For example,

Figure 6 shows a widely used distributed cable model structure. This traditional distributed R-L-C cable model can be used between the inverter and the motor. However, the voltage characteristics at high frequencies cannot be accurately predicted in this model.

The overvoltage on the motor contains oscillations from several hundred Hz to several MHz due to the shorter rise time of the SiC MOSFET. In order to improve the prediction accuracy of motor overvoltage and voltage oscillation under high-frequency conditions, it is necessary to add the high-frequency part to the traditional distributed parameter model in

Figure 6 to reflect the skin effect and proximity effect of the cable.

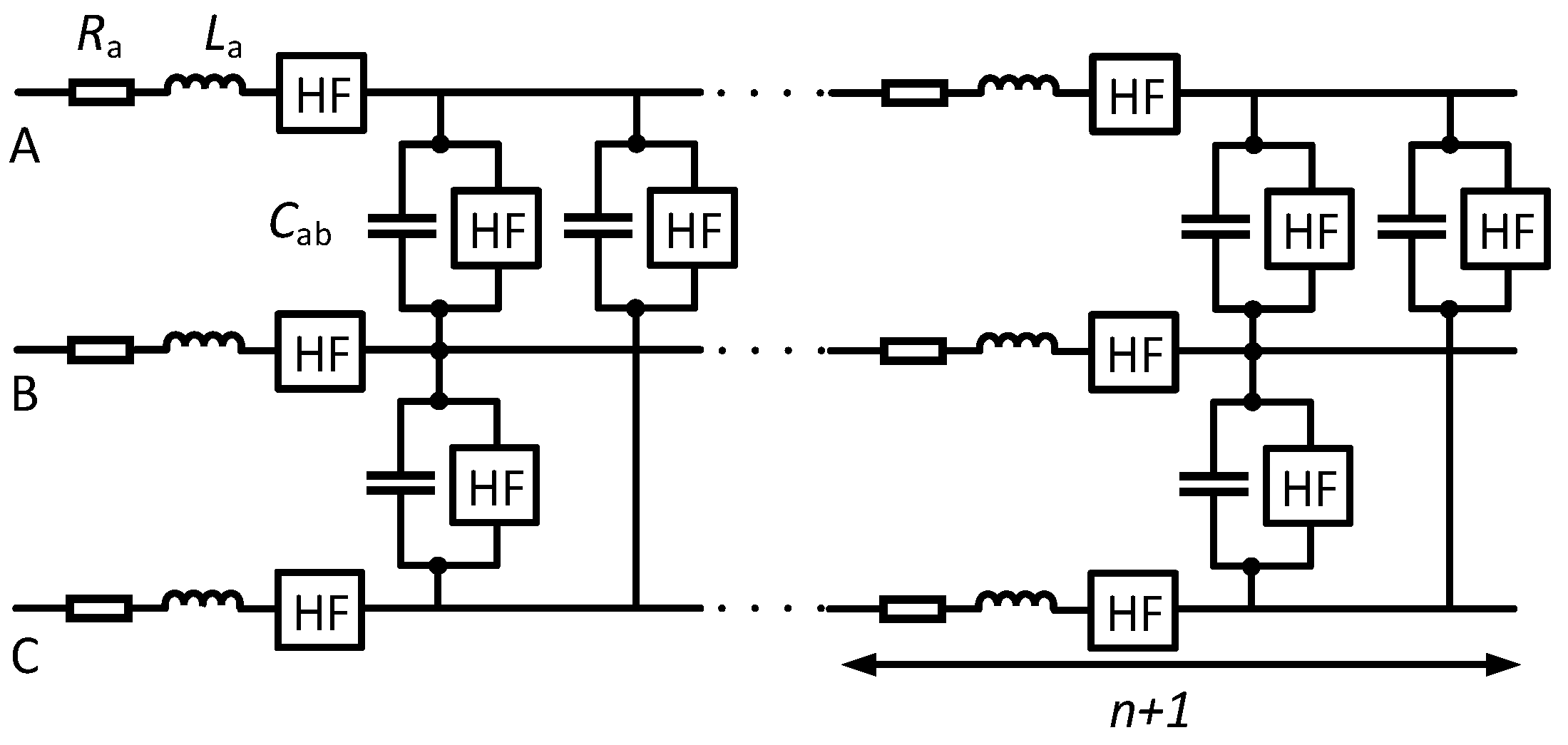

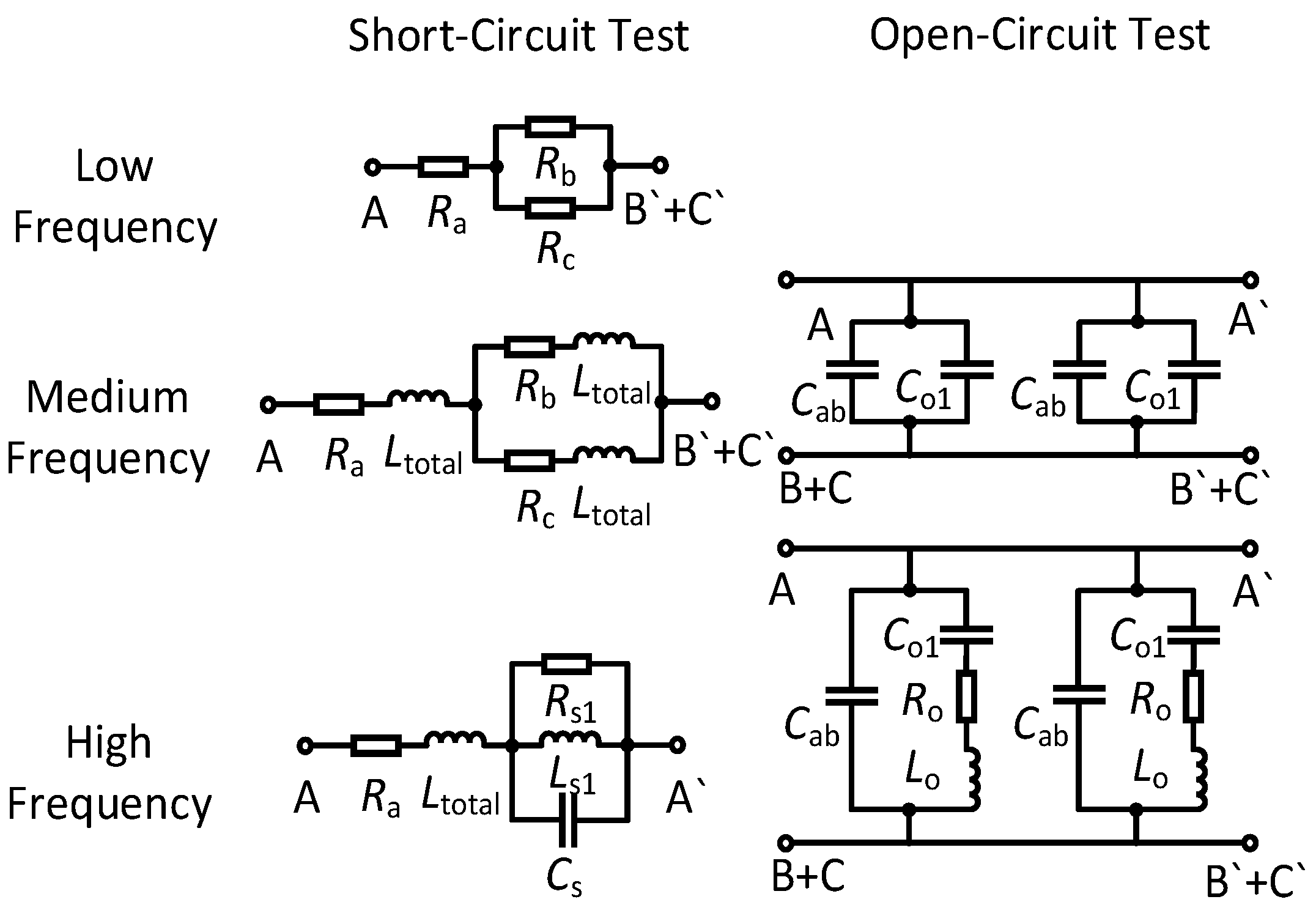

Figure 7 shows the simplified high-frequency three-phase distributed cable model with the high-frequency (HF) block. It should be noted that only one form of cable model cannot cover a wide frequency range.

Figure 8 shows the proposed equivalent circuit cable models in the low, medium, and high frequency regions, and it is represented in two forms (open circuit and short circuit) for the convenience of extracting physical parameters.

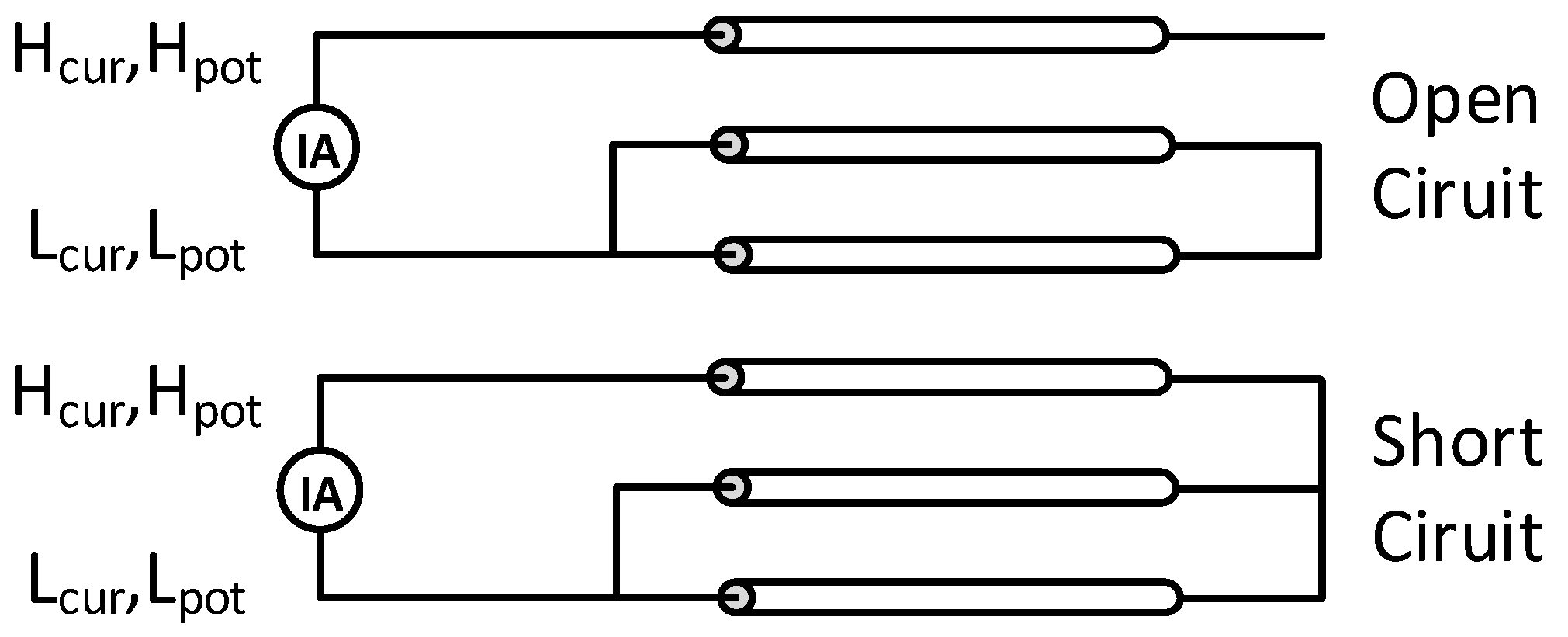

In the following, how the circuit parameters are extracted is explained. The parasitic parameters of cable can be extracted from the impedance measurement as shown in

Figure 9.

Figure 9 shows the connection method of the cables during the short circuit and open circuit test. The series parasitic resistance and inductance of the cables can be obtained by short circuit test and the paralleled parasitic capacitance of the cables can be derived by open circuit test [

21]. Therefore, the high-frequency parameters of the cable model in

Figure 8 can be calculated by extracting the feature points of a real unit length cable. The cable used in this work is an unshielded, crosslinked polyethylene (XLPE) 3 core cable and the conductor area of the cable is 4mm2. An E4990A RLC impedance analyzer and a 16047E test fixture from Keysight is used to extract the parasitic parameters of the cables. The bandwidth of the impedance analyzer is set as 100MHz to identify the resonant point of the cable in the high frequency region.

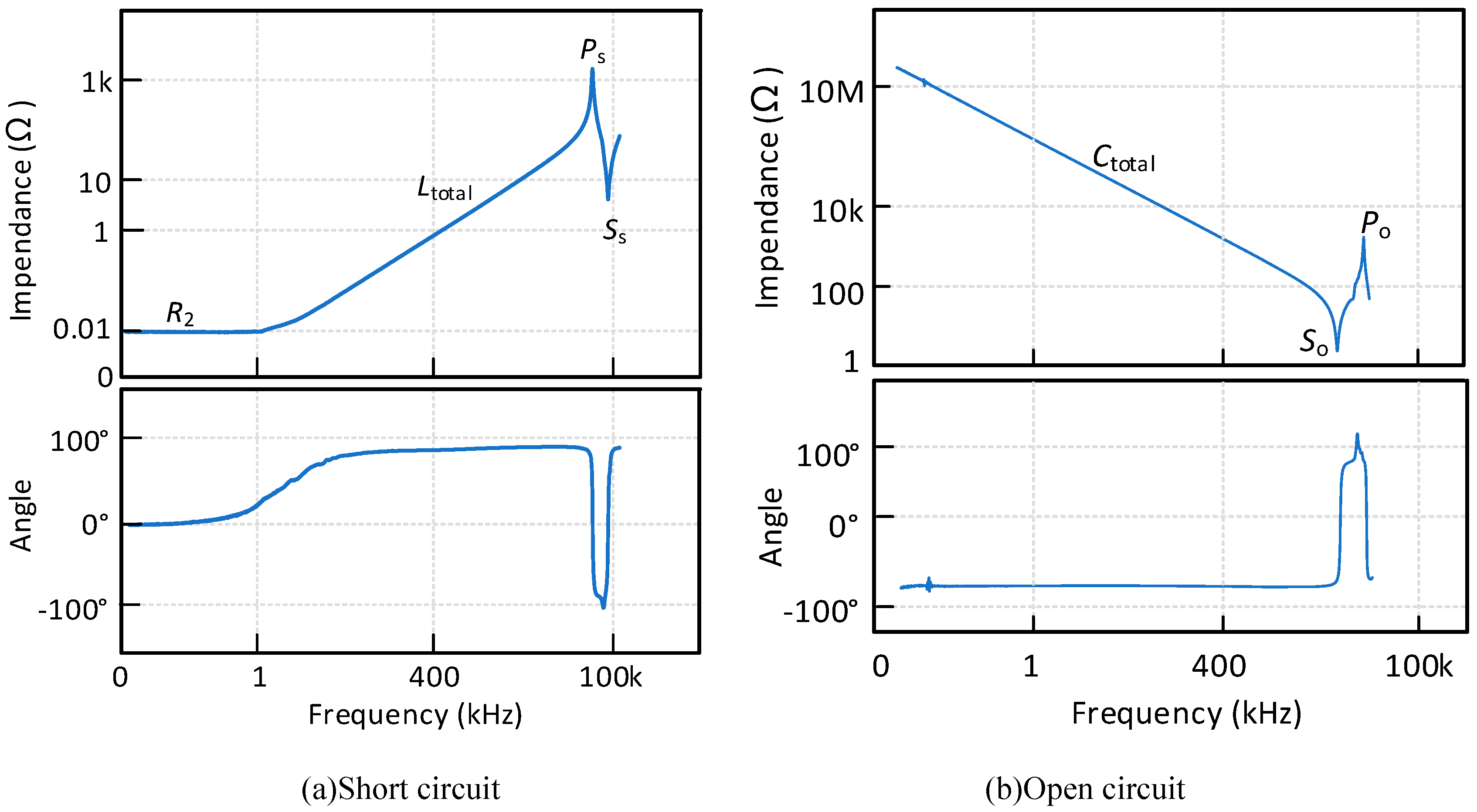

Figure 10 shows the frequency response test results with an 1m cable, where the cable frequency response is shown. At low frequencies, short circuit test shows clear resistive characteristics and open circuit test shows clear capacitive characteristics. In the medium frequency range, short circuit test shows resistive and inductive characteristics and open circuit test still shows capacitive characteristic. At high frequencies, both short circuit test and open circuit test have two resonant points. From these frequency characteristics, the parasitic parameters of the cable can be obtained and parameters can accurately identify by separating the frequency into the low, medium and high regions.

For the short-circuit test, in the low-frequency region, the impedance characteristic of the cable is resistive as seen the impedance angle is around 0-degree as shown in

Figure 10. Therefore, the value of the low-frequency resistance

Rx(x=a,b,c) in

Figure 8 is equal to |

Z|. As the frequency increases, the impedance becomes more inductive. The value of the

Ltotal can be calculated by the average value of the impedance corresponding to the 90-degree impedance angle in the low and medium frequency regions as shown in (9).

It can be seen from

Figure 10 that in the high-frequency region, the parallel resonance phenomenon first occurs at the Ps point, so the value of the high-frequency resistance is equal to |

ZPs| as shown in (10). And the value of the high-frequency capacitance and inductance can be expressed as (11). Similarly, the frequency of

Ss can be expressed as (12) due to the series resonance at point

Ss, where

LT can be expressed in (13).

From (11)-(13), the parameters Cs and Ls1 can be calculated.

The parasitic parameters between phases can be calculated and extracted from the open-circuit impedance as shown in

Figure 10 (b). In the low to medium frequency region, the impedance characteristic is capacitive evidenced by the impedance angle of -90 degree. Therefore, the total capacitance at low-medium frequencies can be derived as:

As the series resonance phenomenon first occurs at

So point, the value of the high-frequency resistance

Ro is equal to |

Z| as shown in (15). And the value of high-frequency capacitance and inductance can be expressed as (16). Similar, the frequency of

Po can be expressed as (17) due to the parallel resonance at point

Po, where

Cp can be expressed as in (18).

Based on the method presented above, the high-frequency parasitic parameters of the cable for per unit length can be accurately extracted, which can help to establish a more accurate cable model. This cable model could accurately fit the high-frequency characteristics of the real cable and accurately predict the amplitude of motor terminal overvoltage under high-frequency excitation. The parameters of unit length cable model parameters are summarized in

Table 2.