1. Introduction

The current global social, economic, and political landscape, shaped by the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath, has created a perfect scenario for an increase in psychological disorders, particularly among children, adolescents, and emerging adults, who have experienced a significant psychosocial impact in recent years (Cai eta al., 2021; Cao et al., 2020; Duan et al., 2020; Huseyin et al., 2021; INE, 2020; Kohls et al., 2021; Orgilés et al., 2020; WHO & UNICEF, 2024; Zhou et al., 2020). In fact, several studies confirm that emerging adults exhibit higher rates of anxiety, stress, and depression compared to other age groups, including adolescents (Gómez-Gómez et al., 2020; Reed-Fitzke, 2020). This may be attributed to adolescents' heightened sense of invulnerability, which leads them to somatise less in response to such threats (Wickman et al., 2008). Emerging adulthood is a transitional stage between adolescence and full adulthood, typically spanning ages 18 to 29 (Arnett, 2000; Barrera & Vinet, 2017). At this stage, individuals are neither adolescents nor fully adults, still grappling with a strong need for environmental adaptation, low self-confidence, and an undefined sense of personal goals, characteristic of adolescence. In addition, they now face significant life challenges, such as gaining access to higher education and navigating the competitive labour market (Cuevas-Caravaca et al., 2024; García-Álvarez, 2022). Furthermore, it is worth noting that, in much of the world, university students constitute a substantial segment of the population, with most of them undergoing emerging adulthood (Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, 2019). Therefore, beyond the already concerning social context in which they live, they must also transition into and adapt to the demanding university environment—an entirely new setting where they continue to explore their identity (Chiang & Hawley, 2013). This stage is also marked by a wide range of unfamiliar rights and responsibilities, such as major educational decision-making, changes in personal autonomy, and challenges related to family, financial, and social independence (Moore & Shell, 2017). These circumstances are frequently associated with stress, anxiety, and depression (Cheung et al., 2020) Numerous studies report a diminished quality of life among university students, characterized by sleep difficulties, lack of motivation, and socio-affective problems linked to anxiety and depression. These conditions are often associated with poorly managed academic stress, the proximity to adolescence, romantic relationships, and financial instability (Cuevas-Caravaca et al., 2024; Riveros, 2018; Silva & de la Cruz, 2017). Moreover, university students with psychological and/or psychiatric conditions are at greater risk of making unfortunate decisions that could negatively impact their academic performance and, consequently, the rest of their adult lives (Lemos et al., 2018; Osorio et al., 2020; Pozos et al., 2015; Rosales et al., 2021).

Regarding the vulnerability of this population, several studies highlight the protective role of psycho-emotional variables such as emotional intelligence and social support networks (Jiménez et al., 2022). However, fewer studies have examined the role of personality traits in either predisposing individuals to or protecting them from mental health conditions, and whether these traits directly influence the coping styles people adopt when facing overwhelming situations (Cuevas-Caravaca et al., 2024). The Big Five personality model has been widely researched. Some of its dimensions are linked to healthy behaviours, while others are associated with maladaptive and psychosocially problematic behaviours in young populations. For example, low academic performance, academic burnout, delinquent behaviour, substance use and abuse, and risky sexual behaviours have shown statistically significant associations with traits such as impulsivity, high neuroticism, and extraversion (Cooper et al., 2003; Cuevas-Caravaca, 2024; Malow et al., 2001). By other hand, coping styles refer to the cognitive and behavioural strategies individuals develop to manage overwhelming demands in their environment, aiming to mitigate the psychological impact of stress (Fernández & Díaz, 2001). According to the literature, active coping styles—focused on behaviour and problem-solving—are associated with greater psychological well-being (Contreras et al., 2007; Khechane & Mwaba, 2004). In contrast, passive coping styles—focused on emotional response and avoidance—tend to be linked to negative mood states such as anxiety and depression, thus posing a risk factor for mental health disorders (Arraras et al., 2002; Bhar et al., 2008). Additionally, several studies confirm that the neuroticism dimension is associated with passive and maladaptive coping styles, whereas the conscientiousness dimension is linked to active coping strategies focused on behaviour and problem-solving (Contreras et al., 2009). However, no significant evidence has been found regarding the remaining personality dimensions and coping styles. The relationship between personality and health has been studied within various theoretical frameworks, such as Eysenck’s personality model, stress control models, and healthy behaviour models (Cabanach et al., 2012). Nonetheless, no theoretical framework has yet fully explained the link between personality and health, with the clearest associations in disease contexts focusing on neuroticism and passive coping styles. Further research is needed to confirm preliminary indications that personality influences health in terms of its onset, persistence, and recovery (Jiménez-Benítez, 2015).

Undoubtedly, promoting and safeguarding mental health is a pressing challenge for higher education institutions. Ideally, universities should not only serve as spaces for professional training but also provide socio-affective support networks (Patiño, 2020). It is urgent to encourage research aimed at identifying potential risk factors to implement long-term mental health surveillance and support programmes on university campuses, contributing to improved prevalence data (Zapata et al., 2021). When mental health issues remain unaddressed during youth, their consequences extend into adulthood, affecting both physical and mental health and limiting individuals’ prospects for leading a fulfilling life (WHO & UNICEF, 2024).

Given the concerns outlined above, the main objectives of this study are: (1) to assess the mental health status of the participant sample; (2) to analyze the role of sociodemographic, personality, and behavioural variables as potential risk factors; and (3) to develop a predictive model tailored to the selected sample. Based on these objectives, the study proposes the following research hypotheses:

A predominance of moderate to severe scores is expected across the three clinical axes: anxiety, stress, and depression.

Sociodemographic variables such as gender, age, marital status, living arrangements, and online study mode are expected to show statistically significant differences within the sample, allowing for the establishment of a risk/protective factor profile.

Certain personality traits—namely, neuroticism, openness to experience, and conscientiousness—are expected to explain moderate to severe anxiety, stress, and depression scores.

Passive stress coping styles are predicted to increase the likelihood of moderate to severe anxiety, stress, and depression.

The recruited sample is expected to confirm the ‘behavioural model of risk/health behaviours’.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

During the sample recruitment phase, the following inclusion criteria were established: (1) being of legal age (18+) and (2) being enrolled in an undergraduate or postgraduate university programme at the time of completing the questionnaire. The exclusion criteria were: (1) failure to properly sign the informed consent form within the questionnaire; (2) being enrolled in a non-regulated higher education programme; and (3) being enrolled at a university outside Spanish territory.

A total of 267 participants were recruited using incidental non-probabilistic sampling. After excluding 25 cases due to omissions and/or response errors, the final sample comprised 242 university students, with a completion rate of 90.6%. Of the total sample, 74.8% were women and 25.2% were men. The participants' ages ranged from 18 to 56 years (M = 25.81; SD = 7.59).

2.2. Measures

A battery of tests was administered, consisting of:

2.2.1. An ad hoc demographic questionnaire, including items on age, gender, marital status, children, employment status, living arrangements, type of studies, and study mode.

2.2.2. The short version of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). This instrument consists of three subscales—depression, anxiety, and stress—each containing seven items that assess the presence of symptoms experienced in the past seven days. The total scale comprises 21 items, with responses scored on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Did not apply to me at all) to 3 (Applied to me very much, or most of the time). The questionnaire is self-administered and can be completed in approximately three minutes. The DASS-21 is derived from the original DASS-42, meaning that final scores are doubled. Normal score ranges are 0–9, 0–7, and 0–14, whereas high scores are 10–28, 8–20, and 15–34 for the depression, anxiety, and stress subscales, respectively. The depression subscale assesses hopelessness, dysphoria, lack of interest, self-deprecation, devaluation, and anhedonia. The anxiety subscale evaluates musculoskeletal symptoms, autonomic arousal, subjective anxious experience, and situational anxiety. The stress subscale measures non-specific persistent activation, irritability, impatience, and inability to relax. Additionally, it has demonstrated good reliability and construct validity (Bibi et al., 2020).

2.2.3. The Big Five Inventory-10 (BFI-10; Rammstedt & John, 2007). This inventory consists of 10 items rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly agree, 5 = Strongly disagree) and is an abbreviated version of the 44-item Big Five Inventory (BFI-44). It uses two items per domain—one representing the positive pole and the other the negative pole—and takes approximately one minute to complete (Carciofo et al., 2016). The BFI-10 assesses global personality traits based on the "Big Five" model, with total scores calculated by summing the items within each domain separately to determine the most dominant trait. The first dimension, Extraversion (items 1 and 6), relates to sociability, assertiveness, and activity, while its opposite, introversion, is characterized by withdrawal, quietness, and reserve. Agreeableness (items 2 and 7) defines interpersonal behaviours, with high scores reflecting altruism, cooperation, trust, and compliance, whereas low scores indicate coldness, suspicion, and critical tendencies. Conscientiousness (Responsibility) (items 3 and 8) differentiates individuals who set goals, are persistent, reliable, and disciplined, from those who are careless, inconsistent, and indifferent. Neuroticism (items 4 and 9) refers to emotional reactivity to unstable situations, with high scores indicating nervousness, anxiety, depression, and insecurity. Finally, Openness to experience (items 5 and 10) reflects curiosity about new projects, impressions, and adventures, with high scores suggesting an imaginative, artistic, and intellectual interest, while low scores indicate strong, conservative opinions and little interest in novelty. The BFI-10 has demonstrated good reliability and validity in large samples, and Cronbach’s alpha is not calculated due to the scale’s brevity and the fact that each dimension contains only two items (Nikčević et al., 2021).

2.2.4. The Coping Strategies Inventory (COPE-28; Carver, 1997). This is an abbreviated version of the original Ways of Coping Checklist (Folkman & Lazarus, 1984), measuring two coping styles: passive and active. It comprises 28 items across 14 dimensions, with two items per dimension, rated on a four-point Likert scale (1 = Never to 4 = Always). The scoring system involves summing items related to active and passive coping styles separately, with the higher score determining the individual’s predominant coping style. The questionnaire is self-administered, simple to complete due to its clarity, and requires approximately three minutes. The active coping style (Approach Coping) includes active coping (items 2 and 7), planning (items 14 and 25), positive reinterpretation (items 12 and 17), humour (items 18 and 28), acceptance (items 20 and 24), emotional support (items 5 and 15), and instrumental support (items 10 and 23). The passive coping style (Avoidance Coping) includes disengagement (items 6 and 16), self-distraction (items 1 and 19), denial (items 3 and 8), religion (items 22 and 27), substance use (items 4 and 11), self-blame (items 13 and 26), and emotional venting (items 9 and 21). Active coping signifies direct problem-solving, while passive coping seeks to avoid stressors and emotional engagement, providing short-term relief but maintaining negative symptoms through denial or cognitive avoidance (Cirami et al., 2020). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient ranges between 0.6 and 0.8, indicating an acceptable level of reliability for measuring stress coping styles.

2.3. Procedure

This study employed a single-group ex post facto design with predictive purposes. Upon obtaining the approval of the University’s Research Ethics Committee (CEO62202), data collection was conducted through an online survey, distributed via social media and messaging services such as email, WhatsApp, and Telegram. The survey was designed using Google Forms and required approximately 10 minutes to complete. At the beginning of the questionnaire, participants were presented with an informed consent form detailing the study’s purpose, anonymity guarantees, voluntary participation, the right to withdraw, and compliance with General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679.

Once the data collection period ended, a data-cleaning process was carried out, eliminating cases in which participants had incomplete or incorrectly answered responses. Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 25 (IBM Corp., 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics v25.0 for Windows; Armonk, NY, USA).

2.4. Data Analysis

First, frequency and descriptive analyses were conducted for qualitative variables, along with symmetry and kurtosis indices and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov goodness-of-fit test for normality for quantitative variables. These quantitative variables were described using standard central tendency measures: mean and median, and variability measures: observed range, standard deviation, and interquartile range. Secondly, to assess relationships between quantitative variables, the following correlation coefficients were used depending on the normality assumption: Pearson correlation coefficient (parametric) and Spearman correlation coefficient (non-parametric). Finally, a series of stepwise linear regression models were developed using forward variable selection. The model coefficients and goodness-of-fit estimators, expressed as R² and adjusted R² (p < 0.05), were included.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

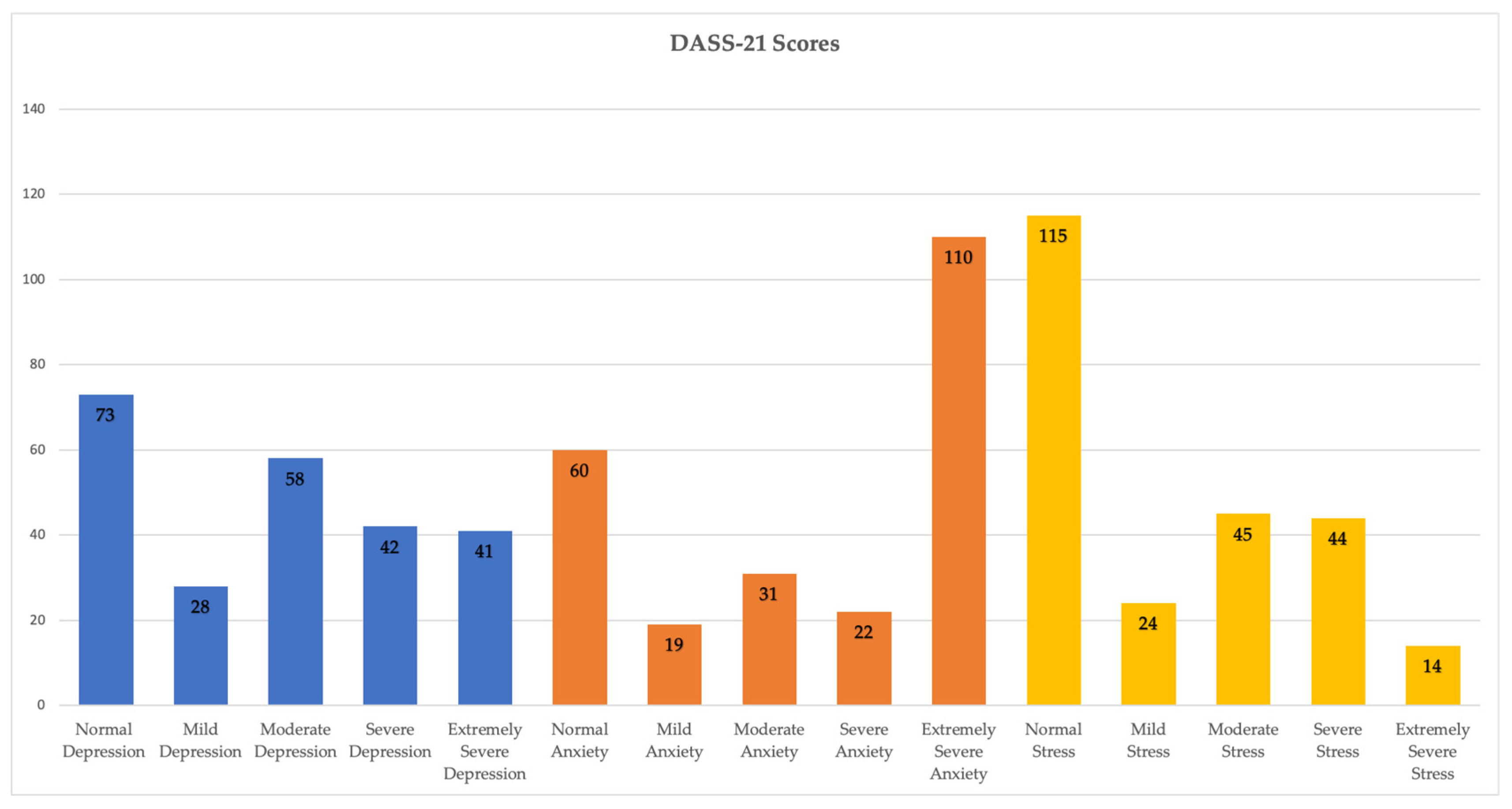

In

Figure 1 y

Table 1, descriptive data and frequencies of the dependent variables examined in this study can be consulted.

Table 1.

Descriptive data and normality tests.

Table 1.

Descriptive data and normality tests.

| Variables |

p |

m |

M |

Min/Max |

SD |

IQR |

| Depression |

.000* |

8.26 |

8.00 |

0.00/21.00 |

5.54 |

8.00 |

| Anxiety |

.000* |

8.67 |

8.50 |

0.00/21.00 |

5.69 |

9.25 |

| Stress |

.000* |

8.19 |

8.00 |

0.00/20.00 |

5.32 |

9.00 |

| Extraversion |

.000* |

5.52 |

6.00 |

2.00/10.00 |

1.34 |

1.00 |

| Agreeableness |

.000* |

5.90 |

6.00 |

2.00/10.00 |

1.48 |

2.00 |

| Responsibility |

.000* |

5.88 |

6.00 |

2.00/10.00 |

1.33 |

2.00 |

| Neuroticism |

.000* |

5.91 |

6.00 |

2.00/10.00 |

1.18 |

2.00 |

| Openness |

.000* |

5.55 |

6.00 |

2.00/10.00 |

1.97 |

3.00 |

| Active coping |

.093 |

19.66 |

20.00 |

4.00/31.00 |

4.80 |

7.00 |

| Passive coping |

.000* |

22.38 |

22.00 |

11.00/34.00 |

4.20 |

5.00 |

Table 2.

Effect of sociodemographic variables on the clinical axes of depression, anxiety, and stress (parametric tests).

Table 2.

Effect of sociodemographic variables on the clinical axes of depression, anxiety, and stress (parametric tests).

| |

Depression |

Anxiety |

Stress |

| p |

m |

SD |

p |

m |

SD |

p |

m |

SD |

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Male (61) |

.000* |

6.54 |

4.97 |

.000* |

6.51 |

5.16 |

.010* |

6.18 |

4.86 |

| Female (181) |

.038* |

8.85 |

5.61 |

.023* |

9.40 |

5.69 |

.000* |

8.87 |

5.30 |

| Marital status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Single (213) |

.000* |

8.35 |

5.54 |

.000* |

8.70 |

5.73 |

.000* |

8.24 |

5.31 |

| Married (23) |

>.200 |

7.96 |

5.38 |

>.200 |

8.78 |

5.55 |

>.200 |

8.43 |

5.68 |

| Civil partnership (3) |

.000* |

8.67 |

8.14 |

.000* |

8.67 |

6.66 |

.000* |

5.67 |

4.62 |

| Divorced (3) |

.000* |

4.33 |

5.86 |

.000* |

5.67 |

4.51 |

.000* |

5.33 |

4.51 |

| Children |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| No (216) |

.000* |

8.38 |

5.57 |

.000* |

8.72 |

5.71 |

.000* |

8.23 |

5.29 |

| Yes (26) |

>.200 |

7.35 |

5.25 |

>.200 |

8.31 |

5.64 |

.081 |

7.92 |

5.64 |

| Occupation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Student (167) |

.001* |

8.54 |

5.69 |

.000* |

8.83 |

5.90 |

.000* |

8.29 |

5.47 |

| Salaried employee (62) |

>.200 |

7.15 |

4.63 |

>.200 |

7.90 |

5.01 |

.031* |

7.53 |

4.86 |

| Unemployed (10) |

>.200 |

11.80 |

7.00 |

>.200 |

12.20 |

5.51 |

>.200 |

11.40 |

5.10 |

| Self-employed (3) |

.000* |

4.33 |

0.58 |

.000* |

4.33 |

1.53 |

.000* |

5.67 |

2.31 |

| Living arrangements |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| With a partner (25) |

.008* |

5.32 |

4.92 |

.060 |

6.32 |

4.68 |

.006* |

5.92 |

5.29 |

| With family (154) |

.018* |

8.64 |

5.27 |

.024* |

8.78 |

5.57 |

.000* |

8.32 |

5.04 |

| With flat mates (49) |

>.200 |

9.20 |

6.49 |

.092 |

9.76 |

6.48 |

.010* |

8.82 |

6.36 |

| Alone (14) |

.199 |

6.14 |

3.88 |

>.200 |

7.93 |

4.97 |

>.200 |

8.64 |

3.52 |

| Studies |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Undergraduate (164) |

.000* |

8.46 |

5.55 |

.000* |

8.98 |

5.76 |

.000* |

8.66 |

5.26 |

| Postgraduate (78) |

>.200 |

7.85 |

5.52 |

.032* |

8.04 |

5.53 |

.030* |

7.22 |

5.33 |

| Study mode |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| In-person (83) |

.008* |

7.25 |

5.13 |

.008* |

8.02 |

5.54 |

.000* |

7.70 |

5.25 |

| Online (159) |

.005* |

8.79 |

5.68 |

.007* |

9.01 |

5.76 |

.001* |

8.45 |

5.35 |

Table 3.

Effect of sociodemographic variables on the clinical axes of depression, anxiety, and stress (non-parametric tests).

Table 3.

Effect of sociodemographic variables on the clinical axes of depression, anxiety, and stress (non-parametric tests).

| |

|

Depression |

|

Anxiety |

|

Stress |

|

| Variables |

Test |

Statistic |

p |

Statistic |

p |

Statistic |

p |

| Sex |

U de Mann-Whitney |

2.75** |

.006 |

3.4** |

.001 |

3.42** |

.001 |

| Marital status |

Kruskal-Wallis |

1.7 |

.638 |

0.89 |

.827 |

1.58 |

.664 |

| Children |

U de Mann-Whitney |

-0.79 |

.431 |

-0.34 |

.730 |

-0.37 |

.713 |

| Occupation |

Kruskal-Wallis |

5.49 |

.064 |

4.78 |

.092 |

4.18 |

.124 |

| Living arrangements |

Kruskal-Wallis |

11.34** |

.010 |

5.55 |

.136 |

5.47 |

.140 |

| Studies |

U de Mann-Whitney |

-0.86 |

.389 |

-1.22 |

.221 |

-2.1* |

.036 |

| Study mode |

U de Mann-Whitney |

1.88 |

.059 |

1.24 |

.217 |

1.02 |

.309 |

3.2. Parametric and Non-Parametric Tests (Qualitative Variables)

3.3. Correlations (Quantitative Variables)

Bivariate correlations were calculated to assess the relationships between mental health axes (depression, anxiety, and stress) and some quantitative factors, such as participants’ age, personality traits, and stress coping styles.

Table 4 presents the correlation coefficients between these quantitative variables, showing that all dimensions of ‘DASS-21’ questionnaire correlate directly and highly significantly with each other (

p = .000). There is a significant inverse correlation between depression levels and Responsibility (

p = .036), indicanting that more responsible individuals tend to exhibit lower levels of depression and vice versa. Additionally, there is an inverse correlation with age (

p = .000), suggesting that depression levels decrease as age increases. Although significant, these correlations are of weak magnitude. A weak direct correlation is observed between passive stress coping and depression (

p = .000), meaning that higher passive coping scores are associated with higher stress levels. Similarly, anxiety levels follow an identical correlation pattern to depression levels, correlating inversely with Responsibility (

p = .033) and age (

p = .005), and directly with passive stress coping (

p = .000). Likewise, stress levels correlate inversely with Responsibility (

p = .005) and age (

p = .000) and directly with passive stress coping (

p = .000).

3.4. Regression Models

Three models were developed to predict participants' mental health axes in accordance with ‘DASS-21’ and they were based on sociodemographic factors, personality traits, and stress coping styles.

Table 5 presents the variables selected for the predictive model of depression, along with their corresponding coefficients. This model includes, in order of importance, the individual's age and sex, employment status, level of passive stress coping, cohabitation with a partner, level of active stress coping, and neuroticism. The model exhibits an adjusted R² value of .180, indicating that the predictor variables can account for approximately 18.0% of the observed variability in depression levels. It is important to note that this value reflects a limited predictive power, as the model fails to explain the remaining 82.0% of the variability in the dependent variable.

Table 6 presents the variables selected for the predictive model of anxiety scores, along with their corresponding coefficients. This model includes, in order of importance, the individual's sex, level of passive stress coping, level of active stress coping, cohabitation with a partner, employment status, and level of neuroticism. As in the previous case, the model exhibits very limited predictive power, as it accounts for only 16.5% of the variability in anxiety levels (Adjusted R² = .165).

Table 7 presents the variables selected for the predictive model of stress scores, along with their corresponding coefficients. This model includes, in order of importance, the level of passive stress coping, the individual's sex, cohabitation with a partner, employment status, level of Responsibility, type of studies pursued, and level of neuroticism. The model exhibits an adjusted R² value of .183, indicating that the predictor variables account for only 18.3% of the variability in stress levels. Once again, this reflects a limited predictive power.

4. Discussion

This analysis began by describing the sample based on its sociodemographic characteristics, mental health status, personality traits, and stress coping styles, concluding with the development of a predictive model for each symptomatic axis assessed by the DASS-21 (anxiety, depression, and stress).

Firstly, it is worth noting that normal and average scores predominated for the depression and stress axes in the recruited sample, whereas for the anxiety axis, the predominant score was “extremely severe.” Consequently, Hypothesis 1 of this study is only partially confirmed, as moderate/severe levels were expected across all three symptomatic axes measured by the DASS-21, as reported in previous similar studies conducted with university populations (Cuevas-Caravaca et al., 2024; Duan et al., 2020; Huseyin et al., 2021; Kohls et al., 2021; Orgilés et al., 2020; Reed-Fitzke, 2020; WHO & UNICEF, 2024; Zhou et al., 2020).

Secondly, it is important to highlight that sex has shown a clear trend across all three symptomatic axes, with women consistently scoring higher in anxiety, depression, and stress. Likewise, being childless, unemployed, living with family (parents/guardians) or flatmates have all emerged as clear risk factors for poor mental health. Conversely, being male, divorced, self-employed, living with a partner appear to play a protective role against mental health disturbances. Regarding sex, being female has been identified as a risk factor predisposing individuals to higher levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. Scores in these areas were significantly higher among female participants compared to their male counterparts, making sex a strong predictor (Huseyin et al., 2021; Muyor-Rodríguez et al., 2021). Regarding age, an inverse relationship has been observed between age and levels of depression, anxiety, and stress in the sample. These findings suggest that as age increases, levels of these mental health conditions decrease. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 of this study is partially confirmed, as the expected relationship with sex aligns with previous national and international studies mentioned above, but the same does not hold for age. Additionally, it has been determined that the type of cohabitation significantly impacts depression levels, which are lower among individuals living with their partner. These findings suggest that being in a relationship may positively influence mental well-being. This may be explained by the fact that individuals living with a partner benefit from a broader socio-emotional support network compared to those living alone (Jiménez et al., 2022; Muyor et al., 2021). Furthermore, they have achieved one of the key milestones of early adulthood: independence from their family nucleus (Arnett, 2000; Moore & Shell, 2017). Regarding the field of study, it has been observed that this factor significantly affects stress levels, which are higher among undergraduate students and those studying online. This indicates that university students experience higher stress levels compared to those who are not currently studying. Thus, these results are highlighting the need for further investigation into this relatively unexplored association in the literature.

Furthermore, an inverse relationship has been found between Responsibility scores and levels of depression, anxiety, and stress. This implies that individuals with higher levels of responsibility tend to exhibit better mental health compared to those with lower scores. Consequently, Hypothesis 3 of this study is partially confirmed, consistent with previous findings by Contreras et al. (2009). However, no significant results were found regarding Neuroticism or Openness to Experience as risk factors, as suggested by other researchers (Cooper et al., 2003; Malow et al., 2001).

A direct relationship has also been observed between passive stress coping and levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, indicating that individuals with a predominantly passive stress coping style are more likely to have poorer mental health indicators (Arraras et al., 2002; Bhar et al., 2008; Lazarus & Folkman, 1986; Mishra et al., 2021). This confirms Hypothesis 4 of this study.

Finally, it is noted that predictive models were developed during the analysis; however, they were found to have limited predictive power. This suggests the need to consider additional factors or variables not included in these models to enhance their predictive capacity. Therefore, Hypothesis 5 of this study was not confirmed. Further research is needed to validate predictive models of health and personality (Jiménez-Benítez, 2015).

5. Conclusions

This study has provided a detailed overview of the sociodemographic characteristics, mental health, personality traits, and stress coping styles of the analysed sample. The findings highlight the importance of age, responsibility, gender, living arrangements, and type of study in participants' mental health. The study also presents evidence of the protective effect of the personality trait ‘Responsibility’ against mental health issues, while emphasising passive coping as a risk factor that should be considered. This trend can be explained by the fact that individuals with a predominant ‘Responsibility’ trait are more likely to engage in protective behaviours and health-related habits than the general population. Conversely, those who frequently adopt a passive coping style, characterised by problem avoidance, are more likely to develop anxiety-depressive symptoms. Furthermore, the need to develop more robust predictive models to better understand these phenomena is highlighted.

A key limitation of this study is the need to increase male participation, as the sample lacked gender balance. Additionally, it would be beneficial to reconsider the inclusion of potential mediating variables that could enhance the explained variance. Moreover, in the three proposed models, greater predictive power could be achieved by binarising the dependent variables, thereby predicting the presence or absence of depression, anxiety, or stress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.A-R.; methodology, J.A.A-R., E.I.S-R. and M.B.C.; formal analysis, E.I.S-R. and M.B.C..; data curation, E.I.S-R. and M.B.C...; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.A-R. and E.C-C.; writing-review and editing, J.A.A-R., E.C-C. and A.I.L-N.; supervision, A.I.L-N. All the authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Catholic University of Murcia (CEO62202, 2023) for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this study would like to express their gratitude to all the anonymous participants in data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arraras, J. I., Wright, S. J., Jusue, G., Tejedor, M. & Calvo, J. I. (2002). Coping style, locus of control, psychological distress and pain-related behaviours in cancer and other diseases. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 7, 181-187.

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55(5), 469. [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Herrera, A., & Vinet, E. V. (2017). Adultez Emergente y Características culturales de la etapa en Universitarios chilenos. Terapia Psicológica, 35(1), 47-56. [CrossRef]

- Bhar, S. S., Brown, G. K. & Beck, A. T. (2008). Dysfunctional beliefs and psychopathology in Borderline Personality Disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 22(2), 165-77.

- Bibi, A., Lin, M., Zhang, X. & Margraf, J. (2020). Psychometric properties and measurement invariance of Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scales (DASS-21) across cultures. International Journal of Psychology, 55 (6), 916-925. [CrossRef]

- Cabanach, R., Fariña, F., Freire, C., González, P, & Ferradás, M. (2013). Diferencias en el afrontamiento del estrés en estudiantes universitarios hombres y mujeres. European Journal of Education and Psychology, 6 (1), 19-32.

- Cai, H., Tu, B., Ma, J., Chen, L., Fu, L., Jiang, Y., & Zhuang, Q. (2020). Psychological Impact and Coping Strategies of Frontline Medical Staff in Hunan Between January and March 2020 During the Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei, China. Medical Science Monitor, 26, e924171-1. [CrossRef]

- Cao, W., Fang, Z., Hou, G., Han, M., Xu, X., Dong, J., & Zheng, J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 217, 112-934. [CrossRef]

- Carciofo, R., Yang, J., Song, N., Du, F. & Zhang, K. (2016). Psychometric Evaluation of Chinese Language 44-Item and 10-Item Big Five Personality Inventories, Including Correlations with Chronotype, Mindfulness and Mind Wandering. PLoS ONE 11(2): e0149963. [CrossRef]

- Cheung, D. K., Tam, D. K. Y., Tsang, M. H., Zhang, D. L. W., & Lit, D. S. W. (2020). Depression, anxiety and stress in different subgroups of first-year university students from 4-year cohort data. Journal of affective disorders, 274, 305–314. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, S. & Hawley, J. (2013). The role of higher education in their life: emerging adults on the crossroad. New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resources Development, 25(3), 3-13. [CrossRef]

- Cirami, L., Hernán, E. & Ferrari, L.E. (2020). Coping with job stress in health workers and reflections on organizational transformations from the COVID-19 pandemic. Revista Subjetividad y Procesos Cognitivos, 24 ( 2).

- Cooper, M. L., Word, P. K. & Albino, A. (2003). Personality and the Predisposition to Engage in Risky or Problem Behaviors during Adolescents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 390-410.

- Cuevas-Caravaca, E., Sánchez-Romero, E.I., y Antón-Ruiz, J.A. (2024). Desgaste académico, personalidad y variables académicas en estudiantes universitarios. Revista Europea de Investigación en Salud, Psicología y Educación, 14 (6), 1561-1571. [CrossRef]

- Duan, L., Shao, X., Wang, Y., Huang, Y., Miao, J., Yang, X., & Zhu, G. (2020). An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in China during the outbreak of COVID-19. Journal of Affective Disorders. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, M. D. & Díaz, M. A. (2001). Relación entre estrategias de afrontamiento, síndromes clínicos y trastornos de personalidad en pacientes esquizofrénicos crónicos. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica, 6, 129-136.

- García-Álvarez, D.; Ricón-Gill, B. & Urdaneta-Barroeta, M.P. (2022). Autopercepción de adultez emergente y sus relaciones con gratitud, ansiedad y bienestar. Revista de Estudios e Investigación en Psicología y Educación, 9 (2), 186-206. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Gómez,M.; Gómez-Mir, P. & Valenzuela, B. (2020). Adolescencia y edad adulta emergente frente al COVID-19 en España y República Dominicana. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes, 7 (3), 35-41. [CrossRef]

- Huseyin, H. C., Ustuner Top, F., & Kuzlu Ayyildiz, T. (2021). Impact of the COVID- 19 pandemic on mental health and health-related quality of life among university students in Turkey. Current Psychology, 1- 10. [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. (2020). Salud Mental. INEGI. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/ temas/salud/default.html#Tabulados.

- Jiménez, A.M.; de la Barrera, U.; Schoeps, K. & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2022). Factores emocionales que median la relación entre inteligencia emocional y problemas psicológicos en adultos emergentes. Psicología Conductual, 30 (1), 249-267. [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Benítez, M. (2015). Mecanismos de relación entre la personalidad y los procesos de salud-enfermedad. Revista de Psicología Universidad de Antioquia, 7(1), 163-184.

- Khechane, N. & Mwaba, K. (2004). Treatment adherence and coping with stress among black South African haemodialysis patients. Social Behavior and Personality, 32, 777-782.

- Kohls, E., Baldofski, S., Moeller, R., Klemm S. L. & Rummel-Kluge, C. (2021). Mental Health, Social and Emotional Well-Being, and Perceived Burdens of University Students During COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown in Germany. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1-1. [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.W. & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, Appraisal and coping. New York: Springer.

- Lemos, M., Henao, M. y López, D. C. (2018). Estrés y salud mental en estudiantes de medicina: relación con afrontamiento y actividades extracurriculares. iMedPub Journals, 14(23). [CrossRef]

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 335–343. [CrossRef]

- alow R. M., Devieux, J. G., Jennings, T., Lucenko, B. A. & Kalichman, S. C. (2001). Substance abusing adolescents at varying levels of HIV risk: Psychosocial characteristics, drug use, and sexual behavior. Journal of Substance Abuse, 13(1-2), 103-117.

- Ministerio de Ciencia Innovación & Universidades (2019). Datos y cifras del sistema universitarioespañol. Available online: https://www.ciencia.gob.es/stfls/MICINN/Universidades/Ficheros/Estadist icas/datos-y-cifras-SUE-2018-19.pdf.

- Mishra, J., Samanta, P., Panigrahi, A., Dash, K., Behera, M. R., & Das, R. (2021). Mental Health Status, Coping Strategies During Covid-19 Pandemic Among Undergraduate Students of Healthcare Profession. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Moore, L. E. & Shell, M. D. (2017). The effects of parental support and self-esteem on internalizing symptoms in emerging adulthood. Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research, 22(2), 131-140. [CrossRef]

- Muyor-Rodríguez, J., Caravaca-Sánchez, F., & Fernández-Prados, J. S. (2021). COVID-19 Fear, Resilience, Social Support, Anxiety, and Suicide among College Students in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18 (15), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Nikčević, A. V., Marino, C., Kolubinski, D. C., Leach, D., & Spada, M. M. (2021). Modelling the contribution of the Big Five personality traits, health anxiety, and COVID-19 psychological distress to generalised anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of affective disorders, 279, 578–584. [CrossRef]

- Orgilés, M., Morales, A., Delveccio, E., Mazzeschi, C., & Espada, J. P. (2020). Immediate Psychological Effects of COVID-19 Quarantine in Youth from Italy and Spain. Frontiers in Psychology, 11: 579038. [CrossRef]

- Osorio, M., Parrello, S. & Prado, C. (2020). Burnout académico en una muestra de estudiantes universita-rios mexicanos. Enseñanza e investigación en Psicología, 12 (1), 27-37. Available online: https://www.revistacneip.org/idex.php/cneip/artcle/view/86/67.

- Patiño, J. (2020). Salud mental y subjetividad: pensando en el mundo universitario pospandemia. USC Universidad Santiago de Cali. [CrossRef]

- Pozos, B. E., Preciado, M. L., Plascencia, A. R., Acosta, M. & Aguilera, M. A. (2015). Estrés académico y síntomas físicos, psicológicos y comportamentales en estudiantes mexicanos de una universidad pública. Revista Ansiedad y Estrés, 21 (1), 35-42. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/ 311605177_Academic_stress_and_physical_psychological_and_behavio ural_factors_in_Mexica-n_ public_university_students.

- Rammstedt, B., John, O.P.(2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality 41 (1), 203–212.

- Reed-Fitzke, K. (2020). El papel de los autoconceptos en la depresión adulta emergente: una síntesis de investigación sistemática. Journal of Adult Development, 27, 36-48. [CrossRef]

- Riveros, A. (2018). Los estudiantes universitarios: vulnerabilidad, atención e intervención en su desarrollo. Revista Digital Universitaria, 19(1), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Rosales, R., Chávez-Flores, Y. V., Pizano, C., (2021). Promoción de la salud mental en el ámbito universitario. Enseñanza e Investigación en Psicología, 3(1), 1-9.

- Silva, B. N. y de la Cruz, U. O. (2017). Autopercepción del estado de salud mental en estudiantes universitarios y propiedades psicométricas del cuestionario de salud general (GHQ28). Revista Iberoamericana de Producción Académica y Gestión Educativa, 4(8). Available online: https://www.pag.org.mx/index.php/ PAG/article/view/676.

- Wickman, M. E., Anderson, N. L. R., & Greenberg, C. S. (2008). The adolescent perception of invincibility and its influence on teen acceptance of health promotion strategies. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 23(6), 460-468. [CrossRef]

- WHO & UNICEF. (2024). Mental Health of Children and Young People: Service Guidance. Ginebra: WHO & UNICEF.

- Zapata, J., Patiño, D., Vélez, C., Campos, S., Madrid, P., Quintero, S., Pérez, A., Ramírez, P., & Vélez, V. (Eds.). (2021). Intervenciones para la salud mental de estudiantes universitarios durante la pandemia por COVID-19: una síntesis crítica de la literatura (Vol. 50, Número 3). Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S. J., Zhang, L. G., Wang, L. L., Guo, Z. C., Wang, J. Q., Chen, J. C., & Chen, J. X. (2020). Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1-10. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).