Submitted:

15 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

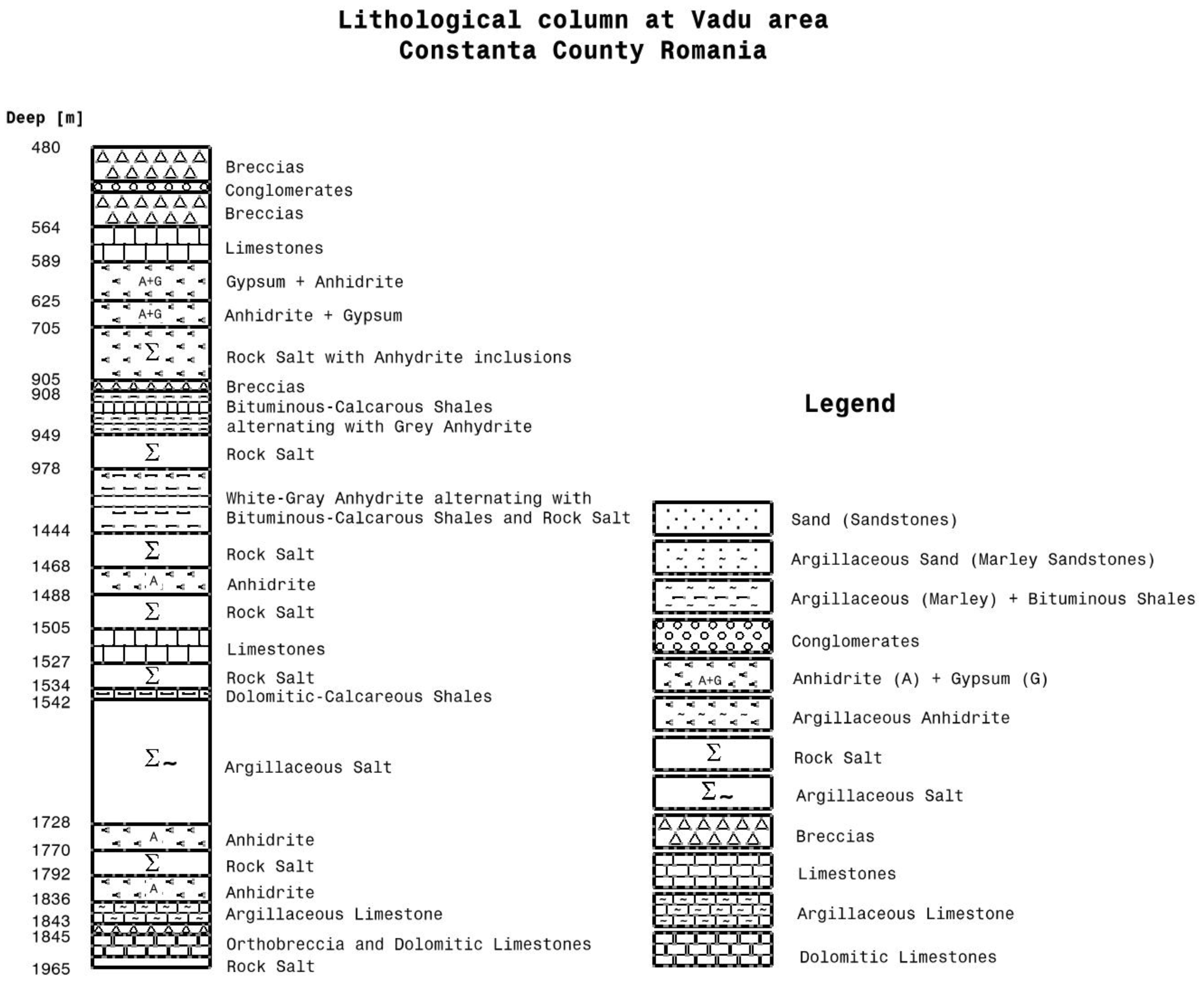

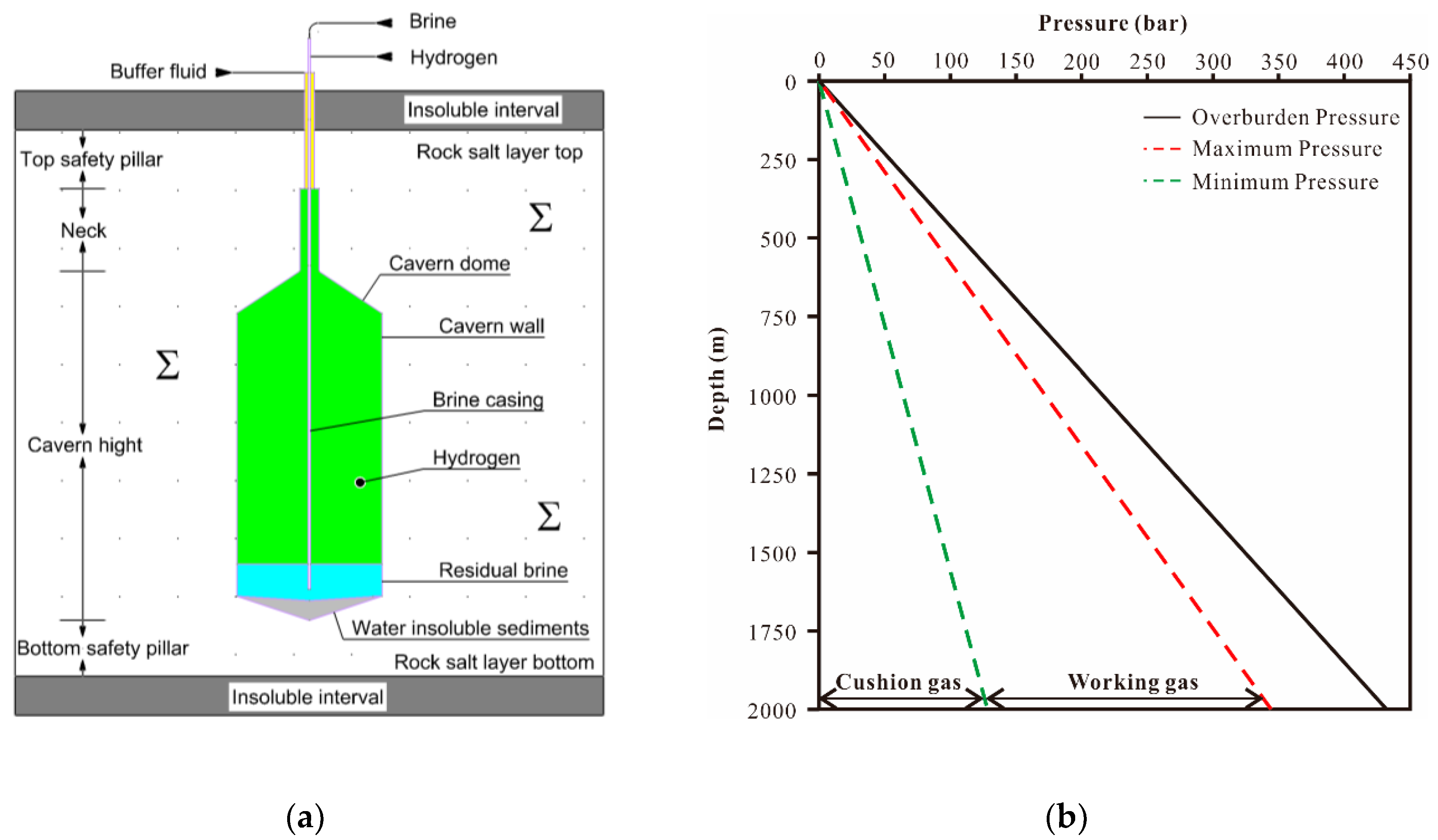

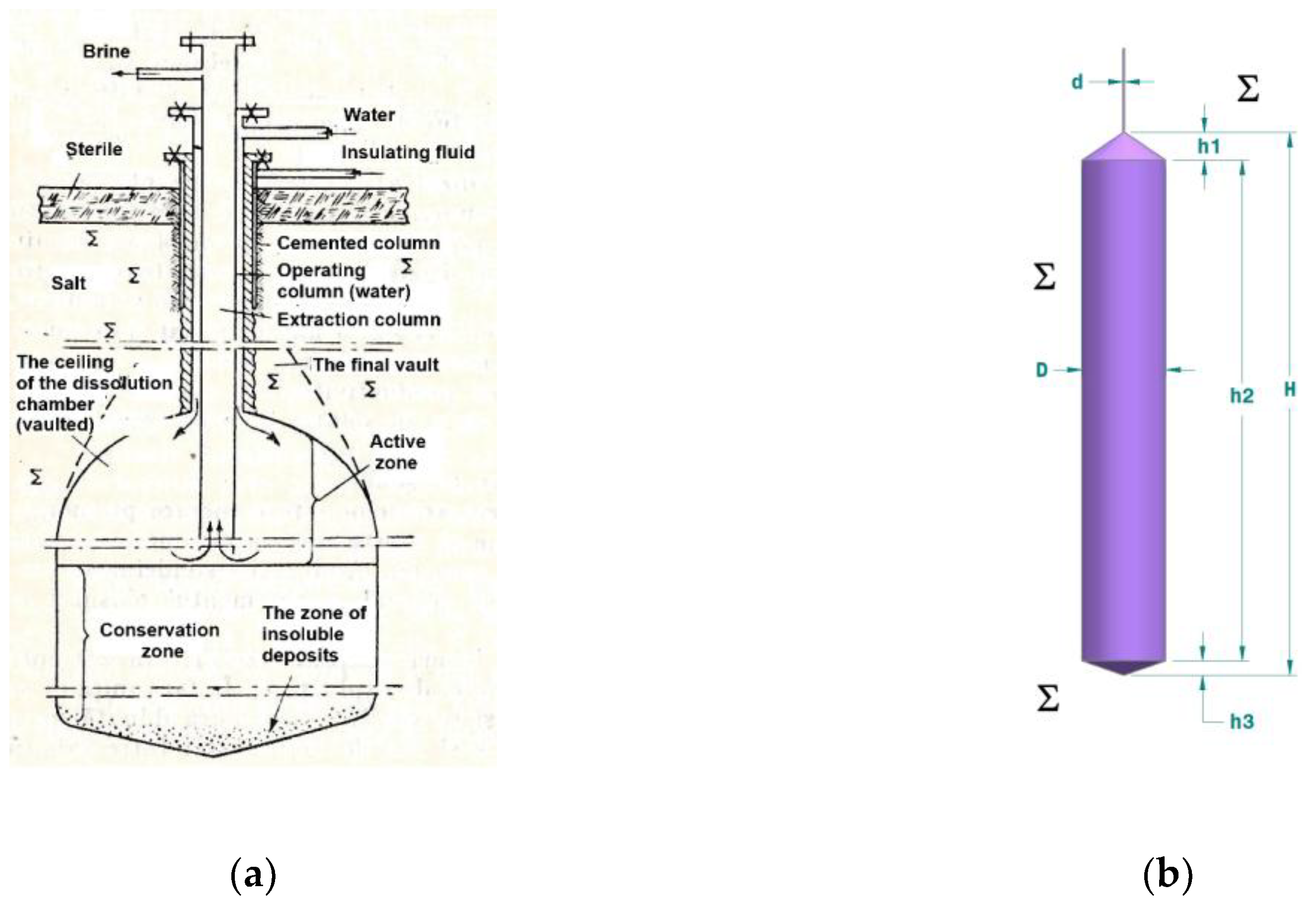

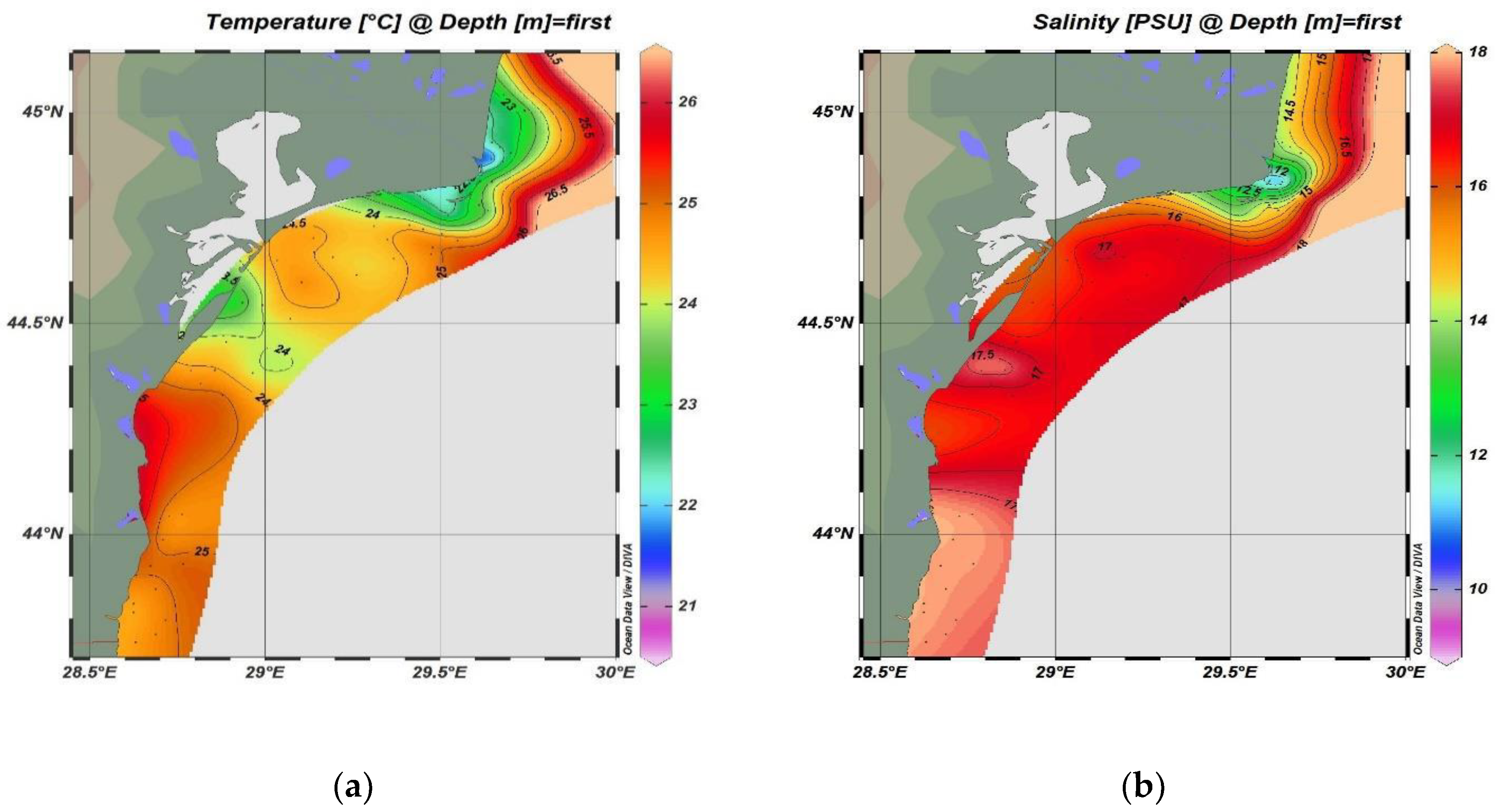

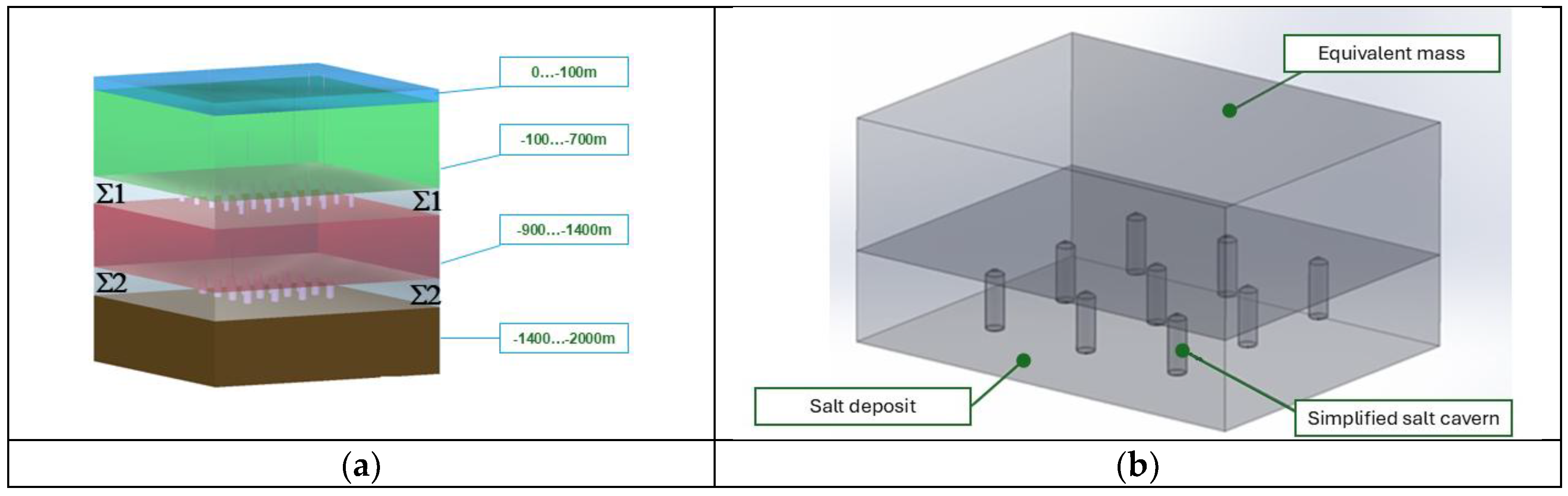

2. The Evaluation Methodology for the Deep Salt Deposit in the Continental Shelf of the Black Sea and Calculus Results for Energy Storage Potential

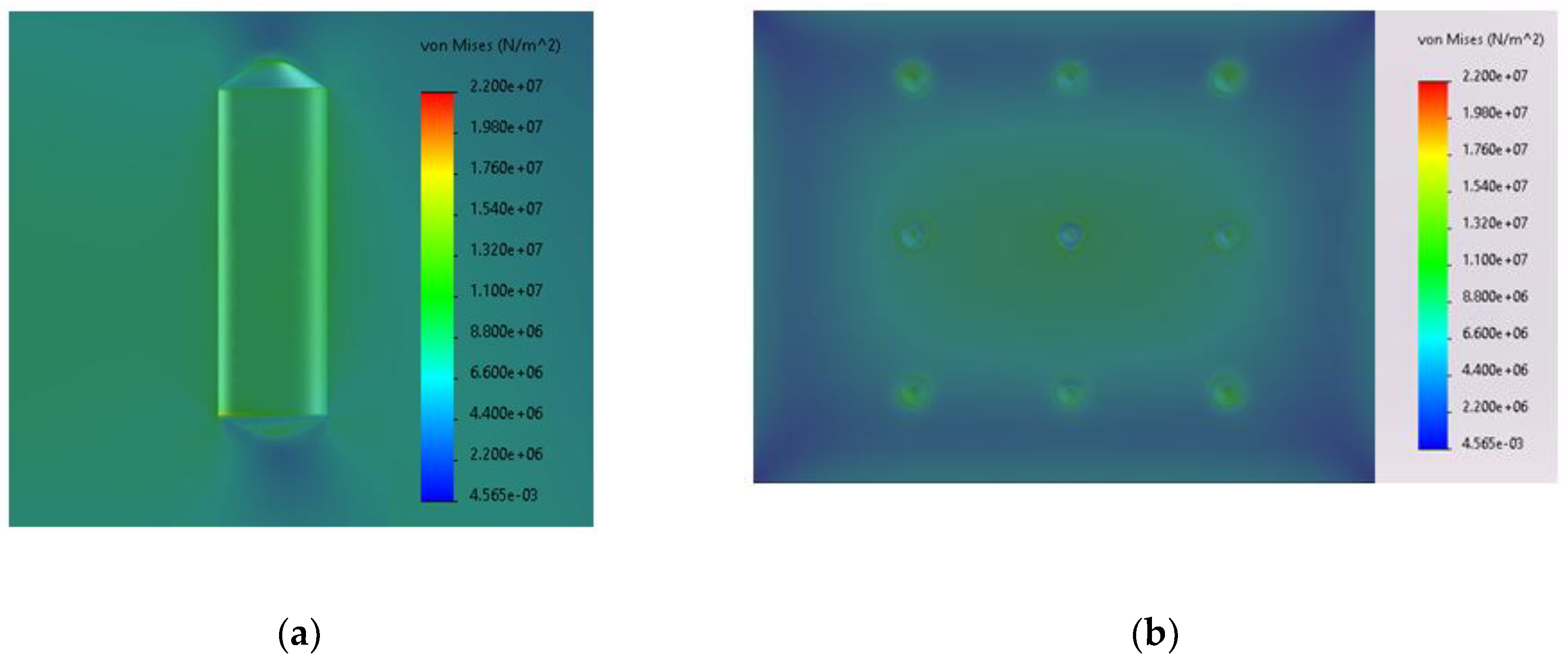

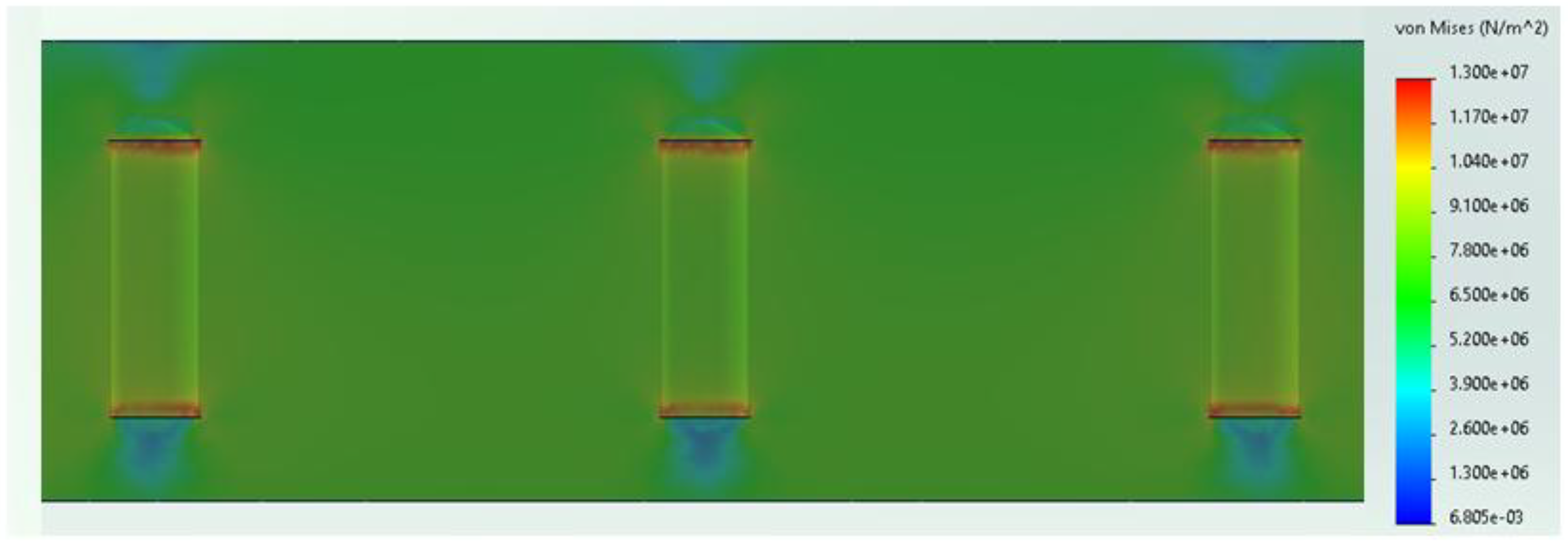

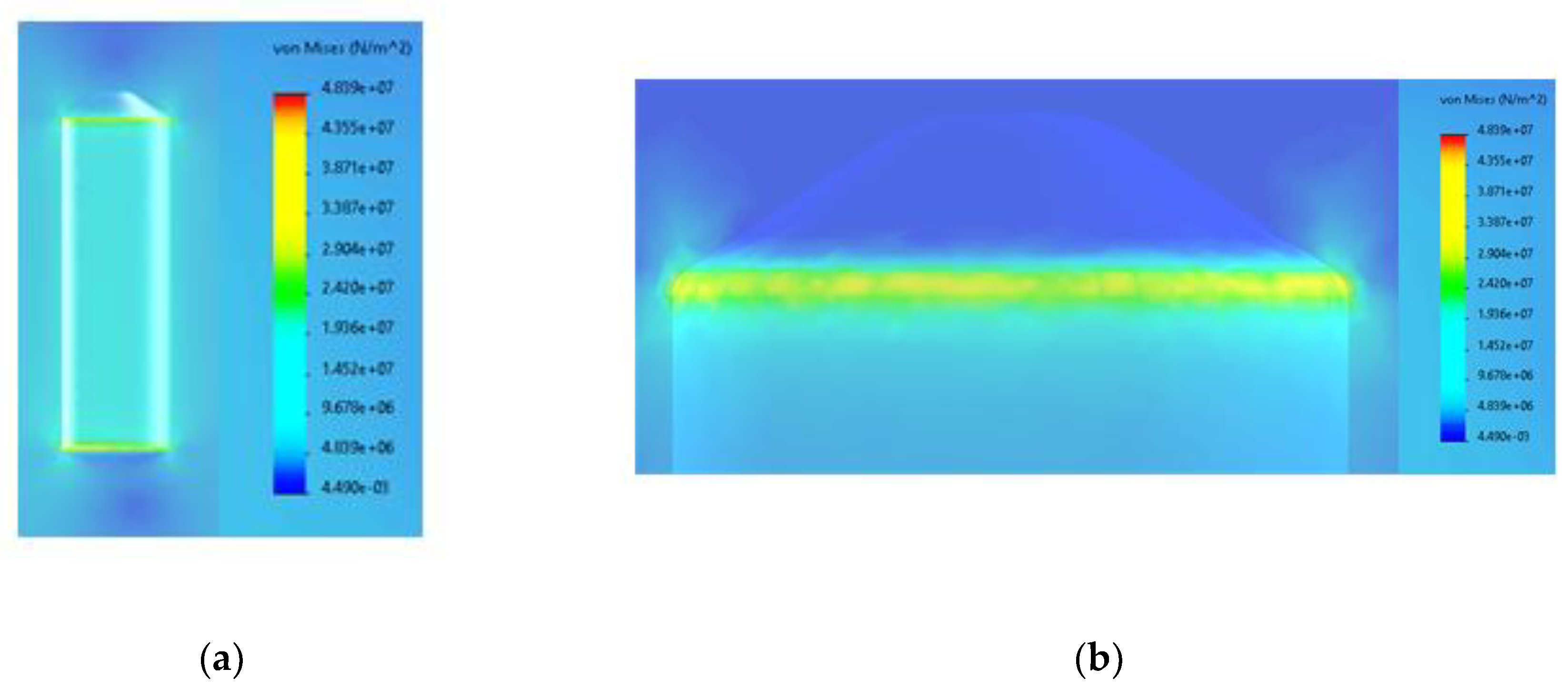

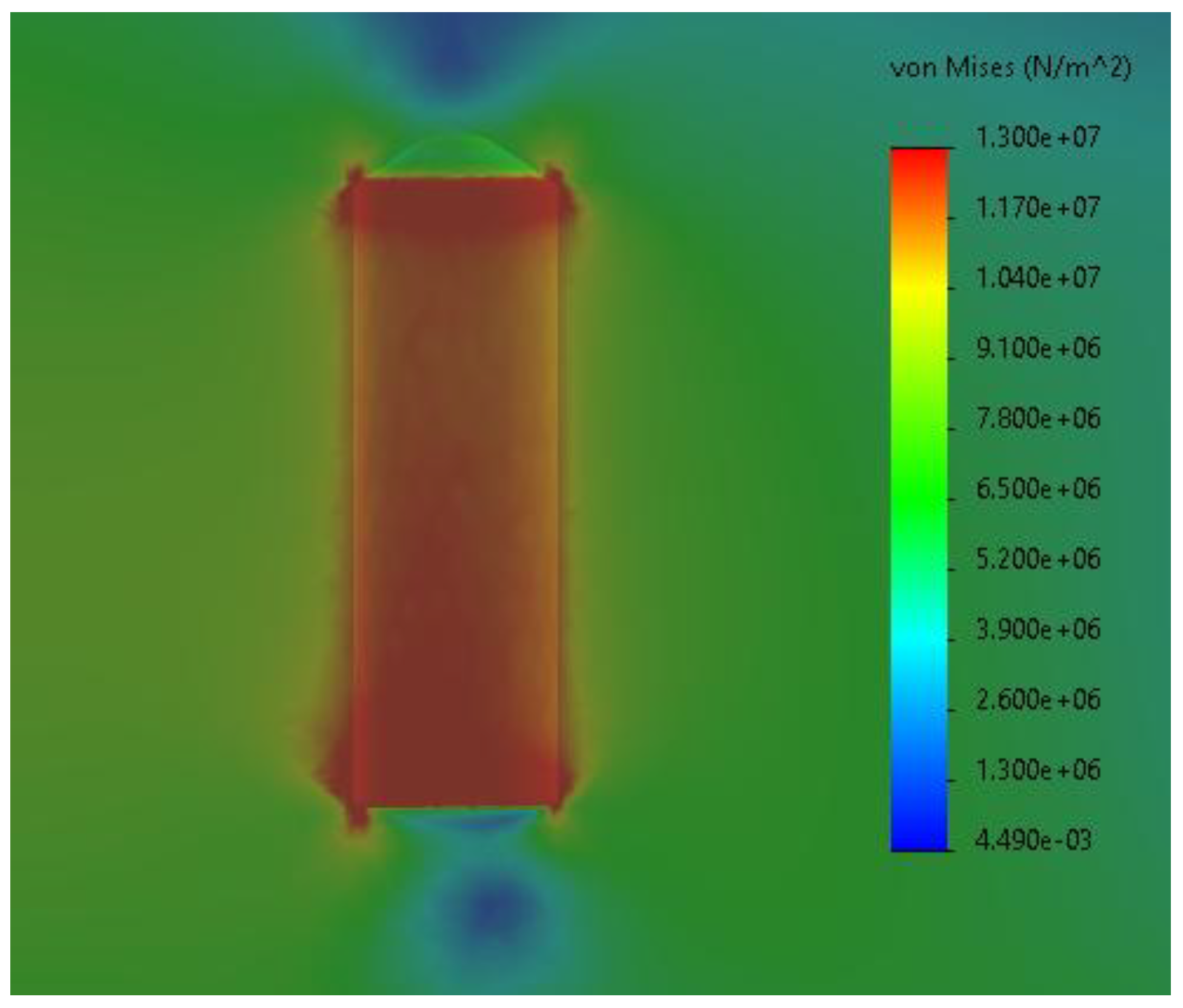

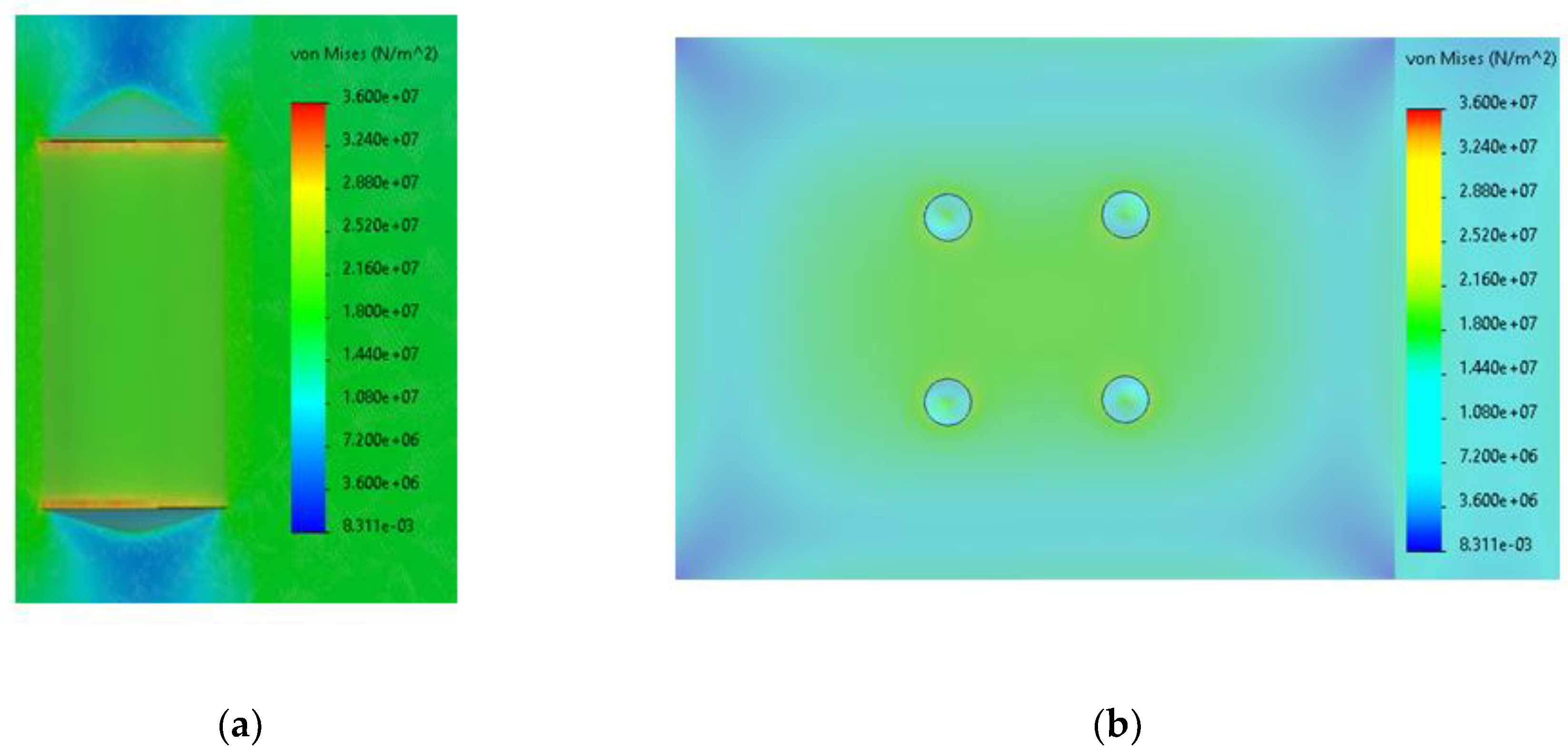

3. FEA Analysis of Underground Hydrogen Storage Caverns: Structural Integrity Under Pressure

4. Short Comparison Between H2 Salt Cavern Storage and H2 Hydrate Storage

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

References

- Hévin, G.; Underground storage of Hydrogen in salt caverns, European Workshop on Underground Energy Storage, Paris, France, 7th - 8th November 2019. Available online: https://energnet.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/3-Hevin-Underground-Storage-H2-in-Salt.pdf (accesed on 29.10.2024).

- Jahanbakhsh, A.; Potapov-Crighton, A. L.; Mosallanezhad A.; Tohidi Kaloorazi N.; Mercedes Maroto-Vale M.; Underground hydrogen storage: A UK perspective, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2024, 189, Part B, 114001. [CrossRef]

- Zhu S.; Shi X.; Yang C.; Bai W.; Wei X.; Yang K.; Li P.; Li H.; Li Y.; Wang G.; Site selection evaluation for salt cavern hydrogen storage in China, Renewable Energy, 2024, 224, 120143. [CrossRef]

- Parliament says shipping industry must contribute to climate neutrality. Press release. European Parliament, 16-09-2020. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/ro/press-room/20200910IPR86825/parliament-says-shipping-industry-must-contribute-to-climate-neutrality (accessed on 08.01.2025).

- How much does the shipping industry contribute to global CO2 emissions? GHG Emissions. Sinai SAS. September 22, 2023. Available online: https://sinay.ai/en/how-much-does-the-shipping-industry-contribute-to-global-co2-emissions/ (accessed on 08.01.2025).

- Dimitriu R. G.; Oaie G.; Ranguelov B.; Radichev R.; Maps of the Gravity and Magnetic Anomalies for the Western Black Sea Continental Margin (Romanian - Bulgarian Sector), In Proceedings of 16th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference SGEM, 2016, 3.

- Oaie G.; Florescu S.; Mare Nigrum – The First Romanian Multidisciplinary Research Vessel in Romania, In Proceedings of EuroEcoGeoCenter - Romania / Danube Delta, Romania, 2004, No. 9-10. Available online: https://geoecomar.ro/website/publicatii/Nr.9-10-2004/22.pdf (accesed on 29.10.2024).

- Mare Nigrum. Ship of national interest. GeoEcoMar. Available online: https://geoecomar.ro/en/research-vessels/mare-nigrum/ (accessed on 08.01.2025).

- Georgiev G.; Geology and Hydrocarbon Systems in the Western Black Sea, Turkish Journal of Earth Sciences, 2012, 21, (5), 4. [CrossRef]

- Flores M. N.; Aleman C. O.; Orozco-del-Castillo M. G.; Fucugauchi J. U.; Castellanos A. R.; Castañeda C. C.; Alcantara A. T.; 3D Gravity Modeling of Complex Salt Features in the Southern Gulf of Mexico, International Journal of Geophysics, 2016, Article ID 1702164. [CrossRef]

- Prutkin I.; Saleh A.; Gravity and magnetic data inversion for 3D topography of the Moho discontinuity in the northern Red Sea area, Egypt, Journal of Geodynamics, 2009, 47, 5, pp. 237-245. [CrossRef]

- Prutkin I.; Vajda P.; Jahr T.; Bleibinhaus F.; Novák P.; Tenzer R., Interpretation of gravity and magnetic data with geological constraints for 3D structure of the Thuringian Basin, Germany, Journal of Applied Geophysics, 2017, 136, pp. 35–41. [CrossRef]

- Juravle D. T., In Geologia Romaniei, Vol. 1, Geologia terenurilor Est-Carpatice (Platformele şi Orogenul Nord-Dobrogean) (Romanian Geology, Vol. 1, Geology of the Eastern Carpathian lands (Platforms and the North Dobrogean Orogen)), Editura STEF, Iasi, Romania, 2009, ISBN: 978-973-1809-55-7, 2009. Available online: https://doru.juravle.com/publicatii/geologia_romaniei_vol01.html (accesed on 29.10.2024).

- Dinu C.; Wong H. K.; Tambrea D.; Matenco L., Stratigraphic and structural characteristics of the Romanian Black Sea shelf, Tectonophysics 2005, 410, (1) pp. 417–435. [CrossRef]

- Coteş D., Studiul geomecanic al masivului de sare din structura Vadu în vederea executării unui rezervor de gaze naturale (Geo-mechanical study of Vadu salt deposit, in view of the construction of an underground natural gas storage facility), PhD. Thesis, University of Petroşani, Faculty of Mines, Petroşani, Romania, 2008.

- Hui S., Yin S., Pang X., Chen Z., Shi K., Potential of Salt Caverns for Hydrogen Storage in Southern Ontario, Canada, Mining 2023, 3, pp. 399–408. [CrossRef]

- Popescu S., Radu M. S., Vîlceanu F., Dinescu S., Research on the setting of maximum pressure in salt caverns intended for CO2 storage, MATEC Web of Conferences, 2022, 373, 00066. [CrossRef]

- Caglayan D. G.; Weber N.; Heinrichs H. U.; Linßen J.; Robinius M.; Kukla P. A.; Stolten D., Technical potential of salt caverns for hydrogen storage in Europe, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2020, 45, pp. 6793–6805. [CrossRef]

- Wang L.; Bérest P.; Brouard B., Mechanical behavior of salt caverns: closed-form solutions vs numerical computations, Rock Mechanics and Rock Engineering, 2015, 48, pp. 2369–2382. [CrossRef]

- Wang T.; Yang C.; Ma H.; Daemen J. J. K.; Wu H., Safety evaluation of gas storage caverns located close to a tectonic fault, Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering, 2015, 23, pp. 281–293. [CrossRef]

- Lux K. H., Design of salt caverns for the storage of natural gas, crude oil and compressed air: geomechanical aspects of construction, operation and abandonment, Geological Society, Special Publications, London, 2009, 313, pp. 93–128. [CrossRef]

- Evans D. J.; Holloway S., A review of onshore UK salt deposits and their potential for underground gas storage. Geological Society, Special Publications, London, 2009, 313, pp. 39–80. [CrossRef]

- Plaat H., Underground gas storage: why and how, Geological Society, Special Publications, London, 2009, 313, pp. 25–37. [CrossRef]

- Ozarslan A., Large-scale hydrogen energy storage in salt caverns, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 2012, 37, pp. 14265–14277. [CrossRef]

- Stolzenburg, K.; Hamelmann, R.; Wietschel, M.; Genoese, F.; Michaelis, J.; Lehmann, J.; Miege, A.; Krause, S.; Donadei, S.; Crotogino, F.; Acht, A.; Sponholz, C. & Horvath, P.-L. (2014). Integration von Wind-Wasserstoff-Systemen in das Energiesystem. Abschlussbericht. Planungsgruppe Energie und Technik (PLANET); Fachhochschule Lübeck (FH Lübeck); Fraunhofer Institut für System- und Innovationstechnik (ISI); Fachhochschule Stralsund (FH Stralsund); Underground Technologies (KBB). Available online: https://www.planet-energie.de/de/media/Abschlussbericht_Integration_von_Wind_Wasserstoff_Systemen_in_das_Energiesystem.pdf (accesed on 29.10.2024).

- Kupfer D. H.; Lock B. E.; Schank P. R., Anomalous zones within the salt at Weeks Island, Louisiana, Gulf Coast Association of Geological Societies Transactions, 1998, 48, pp. 181–192.

- Exploatarea zacamintelor de sare din Romania (II), (Exploitation of salt deposits in Romania (II)), Univers Ingineresc nr. 4/2015. Available online: https://www.agir.ro/univers-ingineresc/numar-4-2015/exploatarea-zacamintelor-de-sare-din-romania-ii_4763.html (accesed on 29.10.2024).

- Stoica C.; Gherasie I., Sarea şi sărurile de potasiu şi magneziu din România (Halite and potassium and magnesium salts from Romania), Editura tehnică, 1981, Bucureşti, Romania.

- Raport privind starea mediului marin şi costier în anul 2022 (Report on the state of the marine and coastal environment in 2022), Institutul National de Cercetare-Dezvoltare Marina „Grigore Antipa” (National Institute for Marine Research and Development “Grigore Antipa”). Available online: https://www.anpm.ro/documents/18093/81141723/2022+Capitolul+II.3+Mediul+marin+si+costier.pdf/08610e93-db2a-4c05-887e-e0980b2f7b35 (accesed on 29.10.2024).

- Furst S. L.; Doucet S.; Vernant P.; Champollion C.; Carme J. L.; Monitoring surface deformation of deep salt mining in Vauvert (France), combining InSAR and leveling data for multi-source inversion, Solid Earth, 2021, 12, pp. 15–34. [CrossRef]

- Popescu P., Analiza stabilității golurilor și riscurile miniere din exploatările de sare în soluție din românia, în vederea utilizării acestora ca depozite subterane (Analysis of void stability and mining risks in solution salt mines in Romania, with a view to their use as underground storage), PhD. Thesis, University of Petroşani, Faculty of Mines, Petroşani, Romania, 2023.

- Paul C., Exploatarea sării prin sonde (Exploitation of salt through wells), Editura Asociaţiei “S.I.P.G.”, 2006, Bucureşti, Romania.

- Allsop C.; Yfantis G.; Passaris E.; Edlmann K., Utilizing publicly available datasets for identifying offshore salt strata and developing salt caverns for hydrogen storage, Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 2023, 528, pp. 139 – 169. [CrossRef]

- Smith N. J. P.; Evans D. J.; Andrew I., The geology of gas storage in offshore salt caverns. Marine, Coastal and Hydrocarbons Programme, British Geological Survey, 1–22. Confidential Report to the Department of Trade and Industry No. GC05/11, 2005.

- Li J.; Tang Y.; Shi X.; Xu W.; Yang C., Modeling the construction of energy storage salt caverns in bedded salt. Applied Energy, 2019, 255, 113866. [CrossRef]

- Solution Mining, Saltwork Consultants Pty Ltd. Available online: https://www.saltworkconsultants.com/solution-mining/ (accessed on 08.01.2025).

- Minkley W.; Knauth M.; Fabig T.; Farag N., Stability and integrity of salt caverns under consideration of hydro-mechanical loading, IfG Institut für Gebirgsmechanik GmbH, 2016. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283871641_Stability_and_integrity_of_salt_caverns_under_consideration_of_hydro-mechanical_loading (accessed on 29.10.2024).

- Li S.; Urai J., Numerical modelling of gravitational sinking of anhydrite stringers in salt (at rest). Bollettino di Geofisica Teorica e Applicata, 2016, 57, pp. 233–246. [CrossRef]

- Zijp M. H. A. A.; Huijgen M. A.; Wilpshaar M.; Bouroullec R. J.; ter Heege H., Stringers in Salt as a Drilling Risk. Report no. TNO2018 R10975 by Nederlandse Organisatie voor Toegepast Natuurwetenschappelijk Onderzoek for Dutch State Supervision of Mines, 2018.

- Urai J. L.; Schmatz J.; Kalver J., Over-pressured Salt Solution Mining Caverns and Leakage Mechanisms. Report, Project KEM-17, Phase 1: Micro-scale processes, 2019. Available online: https://kemprogramma.nl/file/download/a22c0dda-017d-4ecf-9f72-a911d9c51b5c/kem-17-kem-deepnl-colloquium-overpressured-caverns-presentatie-sodm-7-oktober-2021.pdf (accessed on 29.10.2024).

- Li W.; Miao X.; Yang C., Failure analysis for gas storage salt cavern by thermo-mechanical modelling considering rock salt creep, Journal of Energy Storage, 2020, 32, 102004. [CrossRef]

- Taheri S. R.; Pak A.; Shad S.; Mehrgini B.; Razifar M., Investigation of rock salt layer creep and its effects on casing collapse, International Journal of Mining Science and Technology, 2020, 30, pp. 357–365. [CrossRef]

- Bruno M. S., Geomechanical Analysis and Design Considerations for Thin-bedded Salt Caverns. Final report no. DE-FC26-03NT41813, GTI Contract 8701. Terralog Technologies Inc., Arcadia, CA, 2005.

- Cala M.; Cyran K.; Kowalski M.; Wilkosz P., Influence of the anhydrite interbeds on a stability of the storage caverns in the Mechelinki salt deposit (Northern Poland). Archives of Mining Sciences, 2018, 63, pp. 1007–1025. [CrossRef]

- Hamilton W. N., Salt in east-central Alberta. Research Council of Alberta, RCA/AGS Bulletin, 1971, 29, 65.

- Richter-Bernburg G., Salt tectonics, interior structures of salt bodies. Bulletin des Centres de Recherches Exploration-Production Elf-Aquitaine, 1980, 4, pp. 373–393,.

- Li J.; Tang Y.; Shi X.; Xu W.; Yang C., Modeling the construction of energy storage salt caverns in bedded salt, Applied Energy, 2019, 255, 113866. [CrossRef]

- Looff K.; Duffield J.; Looff K., Edge of salt definition for salt domes and other deformed salt structures – geologic and geophysical considerations, Solution Mining Research Institute Technical Conference, 2003, Houston, TX, United States of America.

- F. Chen, Z. Ma, H. Nasrabadi, B. Chen, M. Z. Saad Mehana, J. Van Wijk, Capacity assessment and cost analysis of geologic storage of hydrogen: A case study in Intermountain-West Region USA, IJHE 48 (2023) 9008-9022. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, Yan Li, Y. Rao, Yang Li, T. He, P. Linga, X. Wang, Q. Chen, Z. Yin, Probing the pathway of H2-THF and H2-DIOX sII hydrates formation: Implication on hydrate-based H2 storage, Applied Energy 376 (2024) 124289. [CrossRef]

- T. Shibata, H. Yamachi, R. Ohmura, Y. H. Mori, Engineering investigation of hydrogen storage in the form of a clathrate hydrate: Conceptual designs of underground hydrate-storage silos, IJHE, 37, 9, 2012, pp. 7612-7623. [CrossRef]

- D. Rutherford, X. Mao, B. Comer, Potential CO2 reductions under the Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index, ICCT WORKING PAPER 2020-27, 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/345950880_Potential_CO_2_reductions_under_the_Energy_Efficiency_Existing_Ship_Index. (accessed on 13.02.2025).

- Romanian Energy Strategy 2016-2030, With an Outlook to 2050. Executive Summary, Ministry of Energy. Available online: https://energie.gov.ro/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Romanian-Energy-Strategy-2016-2030-executive-summary3-1.pdf (accessed on 29.10.2024).

- Dogar A., Producători de energie eoliană în România. Lista completă a centralelor în 2024 (Wind energy producers in Romania. Complete list of power plants in 2024), GreatNews, April 4, 2024. Available online: https://onoff.greatnews.ro/producatori-de-energie-eoliana-in-romania-lista-completa-a-centralelor-in-2024/ (accessed on 08.01.2025).

- Nicut M., Premieră: România a depășit pragul de 1.000 MW producție instantanee de energie solară pentru prima dată în istorie (Premiere: Romania has exceeded the threshold of 1,000 MW of instantaneous solar energy production for the first time in history), ECONOMICA.net, March 4, 2024. Available online: https://www.economica.net/premiera-romania-a-depasit-pragul-de-1-000-mw-productie-instantanee-de-energie-solara-pentru-prima-data-in-istorie_729357.html (accessed on 08.01.2025).

- EWE, Siemens Energy to build 280 MW green hydrogen electrolysis plant, Reuters, July 25, 2024. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/ewe-siemens-energy-build-280-mw-green-hydrogen-electrolysis-plant-2024-07-25/ (accessed on 08.01.2025).

- Vlăducă I.; Nechifor C. V.; Vasile M. L.; Suciu C. P.; Badea P. G.; Stănescu T.; Nicoară R. E.; Prisăcariu E. G.; Stanciuc R. M.; Popescu S.; Dinescu S.; Obreja A. M., Hydrogen Storage in Offshore Salt Caverns for Reducing Ships Carbon Dioxide Footprint, Technium: Romanian Journal of Applied Sciences and Technology (ISSN: 2668-778X), 2022, 4, 9. [CrossRef]

- Tetrahydrofuran. National Library of Medicine. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Tetrahydrofuran. (accessed on 13.02.2025).

- P.A. O’Neill, Industrial compressors. Theory and equipment. Butterworth-Heinemann Ltd, Linacre House, Oxford, Great Britain, 1993. ISBN 0-7506-0870-6.

| Parameters | Values | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distance between caverns(axis to axis) | 4 times the cavern diameter | Caglayan et al. (2020) [18] | |

| Ceiling-wall thickness | 75% from cavern diameter | Caglayan et al. (2020) [18] | |

| Foot-wall thickness | 20% from cavern diameter | L. Wang et al. (2015) [19] | |

| Height / Diameter ratio | > 0,5 | T. Wang et al. (2015) [20] | |

| The shape of the caverns | Bell-shaped or cylindrical | Lux (2009) [21] | |

| The depth range where from the cavern begin to be formed | 500 - 3000m | Evans and Holloway (2009) [22] Plaat (2009) [23] Caglayan et al. (2020) [18] |

|

| Distance from adjacent faults/ discontinuities or old workings (e.g. abandoned oil wells) | > 2 times the cavern diameter | L. Wang et al. (2015) [19] | |

| H2 operating pressure (measured at the bottom of the cemented column) | Pmin=24%, Pmax=80% from geostatic pressure | Ozarslan (2012); [24]Stolzenburg et al. (2014) [25] | |

| Distance from salt formation edge (dome margins) | > 500m (diapiric) > 2000m (sedimentary) |

Kupfer et al. (1998) [26] Caglayan et al. (2020) [18] |

|

| Physically | Mechanically | Elastically | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific distance γ.104[N/m3] |

Apparent specific gravity a.104[N/m3] | Porosity n[%] |

Humidity W[%] | Compressive strength σrc,[MPa] | Tensile strength σrt, [MPa] | Flexural strength σrf, [MPa] |

Cohesion C [MPa] | The angle of internal friction ϕ, [0] | The modulus of elasticity E [MPa] | The tension at the dilatation threshold σd*[MPa] |

Wave propagation speed v[m/s] |

| 2.175 - 2.181 | 2.04 - 2.059 | 0.82 - 1.231 | 2.13 - 3.13 | 21.94 - 36.76 | 0.80 - 2.154 | 9.75 - 13.00 | 1.20 - 4.42 | 39 - 42 | 2120 - 2610 | 12.94 - 15.65 | 3885 - 4215 |

| Deposit | Praid | Ocna Dej | Ocnele Mari | Tg. Ocna | Slanic Prahova | Vadu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Romanian County | Harghita | Cluj | Valcea | Bacau | Prahova | Constanta |

| Compression strength | 21.7 [ MPa] |

21.1 [ MPa] |

18.3 [ MPa] |

25 [ MPa] |

20 [ MPa] |

30 [ MPa] |

| Parameter | Cavern A | Cavern B |

|---|---|---|

| Diameter [m] | 40 | 60 |

| Height [m] | 120 | 120 |

| Cavern total volume [m3] | 150,000 | 320,000 |

| Cavern free volume [m3] | 100,000 | 225,000 |

| Formation time/step | 200 days/8.7 m=23 days/m | 300 days/5.7 m=51 days/m |

| Total time for a cavern formation | 2,760 days~92 month~8 years | 6120 days~204 month~17 years |

| Depth to cavern ceiling from seabed [m] | 700 | 1,400 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Seabed depth | 20 ÷ 100 m |

| Fraction of total cavern volume used as cavern free volume | 70% |

| Average temperature at wellhead | 6°C |

| Maximum cavern pressure, measured at the LCCS (Last Cemented Casing Shoe) | 0.80 · σv |

| Minimum cavern pressure, measured at the LCCS | 0.20 · σv |

| Average temperature at seabed | 9°C |

| Geothermal gradient | 0.031°C/m |

| Calculations results | Cavern A | Cavern B |

|---|---|---|

| Depth to cavern ceiling from seabed (m] | 700 | 1,400 |

| Geostatic vertical stress at the LCCS depth (bar) | 150 | 290 |

| Maximum cavern pressure, measured at the LCCS (bar-abs) | 120 | 230 |

| Minimum cavern pressure, measured at the LCCS (bar-abs) | 30 | 60 |

| Temperature at cavern mid-height (°C) | 31 | 53 |

| Cushion hydrogen required to maintain minimum cavern pressure (millions Nm3) | 2.75 | 11.16 |

| Cushion hydrogen required to maintain minimum cavern pressure (tonnes) | 245 | 996 |

| Netto hydrogen volume (million Nm3) | 7.9 | 31.61 |

| Netto hydrogen mass (tonnes) | 704 | 2,821 |

| Netto energy stored in the cavern (GWh) | 23.443 | 93.939 |

| Energy density per cavern (MWh/tonne) | 33.3 | |

| Parameter | Criteria | Positive indicator score = 10 |

Intermediate indicator score = 5 |

Cautionary indicator score = 1 |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Host salt formation | Depth (m) (from seabed) | 1000–1500 | 500–1000 and 1500–2000 | <500 and >2000 | Smith et al. (2005) [34]; Evans and Holloway (2009) [22]; Plaat (2009) [23]; Caglayan et al. (2020) [18] |

| Thickness (m) | >400 | 200-400 | <200 | Caglayan et al. (2020) [18]; Allsop et al. (2023) [16]; |

|

| Purity (%) | >80 | 60-80 | <60 | Li et al. (2019) [35] ; Saltwork Consultants Pty Ltd (2021) [36]; |

|

| In situ stress state | Isotropic | Orthotropic | Anisotropic | Minkley et al. (2015) [37]; Li and Urai (2016) [38]; Zijp et al. (2018) [39] ; Urai et al. (2019) [40]; |

|

| Load bearing rock formation (hanging and foot wall) | Lithology | Halite | Mudstone and K–Mg salts | Carbonate and anhydrite | Li et al. (2020) [41] ; Taheri et al. (2020) [42]; |

| Thickness (m) | Bedded hanging: >80; foot: >30 |

Bedded hanging: 63; foot: 16.8 | Bedded hanging: <60; foot: <20 |

Bruno (2005) [43] ; Wang T. et al. (2015) [20]; Caglayan et al. (2020) [18]; |

|

| Diapiric hanging: >50; foot: >15 |

Diapiric hanging: >43.5; foot: 11.6 |

Diapiric hanging: <40; foot: <10 |

|||

| Structural features | None | Folding | Faults/fractures | Allsop et al. (2023) [16]; | |

| Lithological Interlayers If no interlayers, award score = 100 | Lithology | K–Mg salts and polyhalite | Anhydrite and mudstone | Carbonates | Li and Urai (2016) [38]; Cala et al. (2018) [44]; Zijp et al. (2018) [39]; Urai et al. (2019) [40]; |

| Thickness (m) (non-salt) | <3 (single interlayer) | 3 (single interlayer) | >3 (single interlayer) | Hamilton (1971) [45]; | |

| Thickness (m) (K–Mg salts) | <3 (total thickness) | 3–10 (total thickness) | >10 (total thickness) | Urai et al. (2019) [40]; | |

| Location | Base | Centre | Top | Richter-Bernburg (1980) [46]; Li et al. (2019) [47]; |

|

| Number of interlayers | 0 | 1 – 2 | > 2 | Li and Urai (2016) [38]; Cala et al. (2018) [44]; Zijp et al. (2018) [39]; Urai et al. (2019) [40]; |

|

| Cavern geometry | Cavern volume (m3)/ height (m) | 750,000 (300) |

500,000 (120) |

n/a | Caglayan et al. (2020) [18]; |

| Distance from salt edge (m) | Bedded: 2000 | Bedded: <2000, >500 | > 500 m | Kupfer et al. (1998) [26]; Looff et al. (2003) [48]; |

|

| Diapiric: 1000 | Diapiric: <1000, >500 |

Caglayan et al. (2020) [17]; | |||

| Industrial | Pipeline infrastructure (km) | < 5 | 5 – 10 | > 10 | Allsop et al. (2023) [16]; |

| Distance from UK coastline (km) |

< 50 | 50 – 80 | > 80 | Allsop et al. (2023) [16]; |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).