Submitted:

25 February 2025

Posted:

26 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

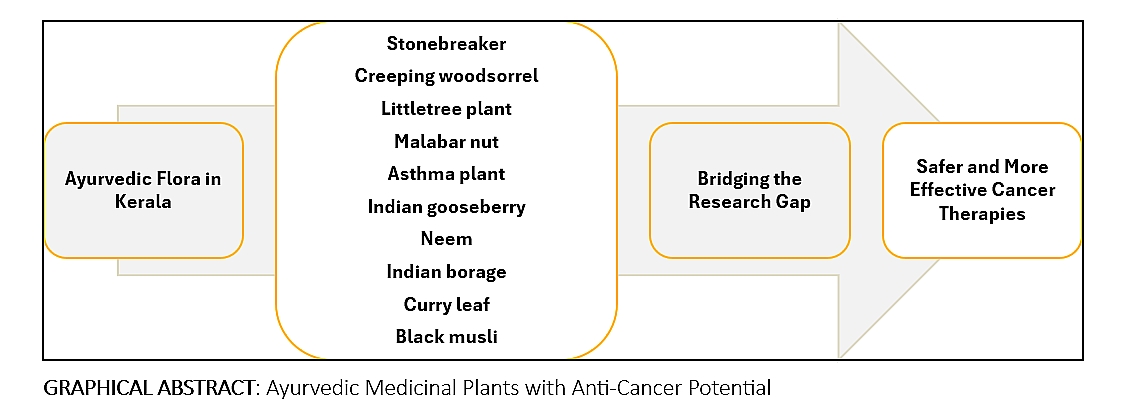

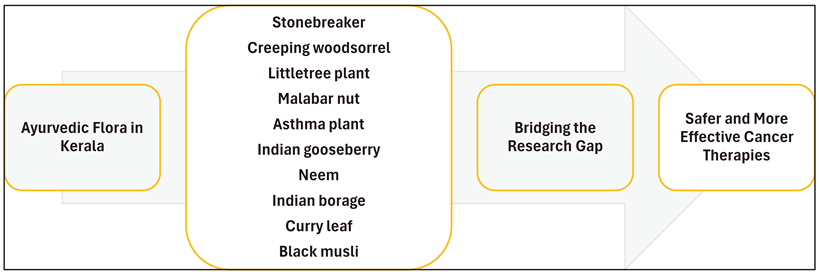

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Review Method

3. Ayurvedic Medicinal Plants: Promising Candidates in Cancer Research

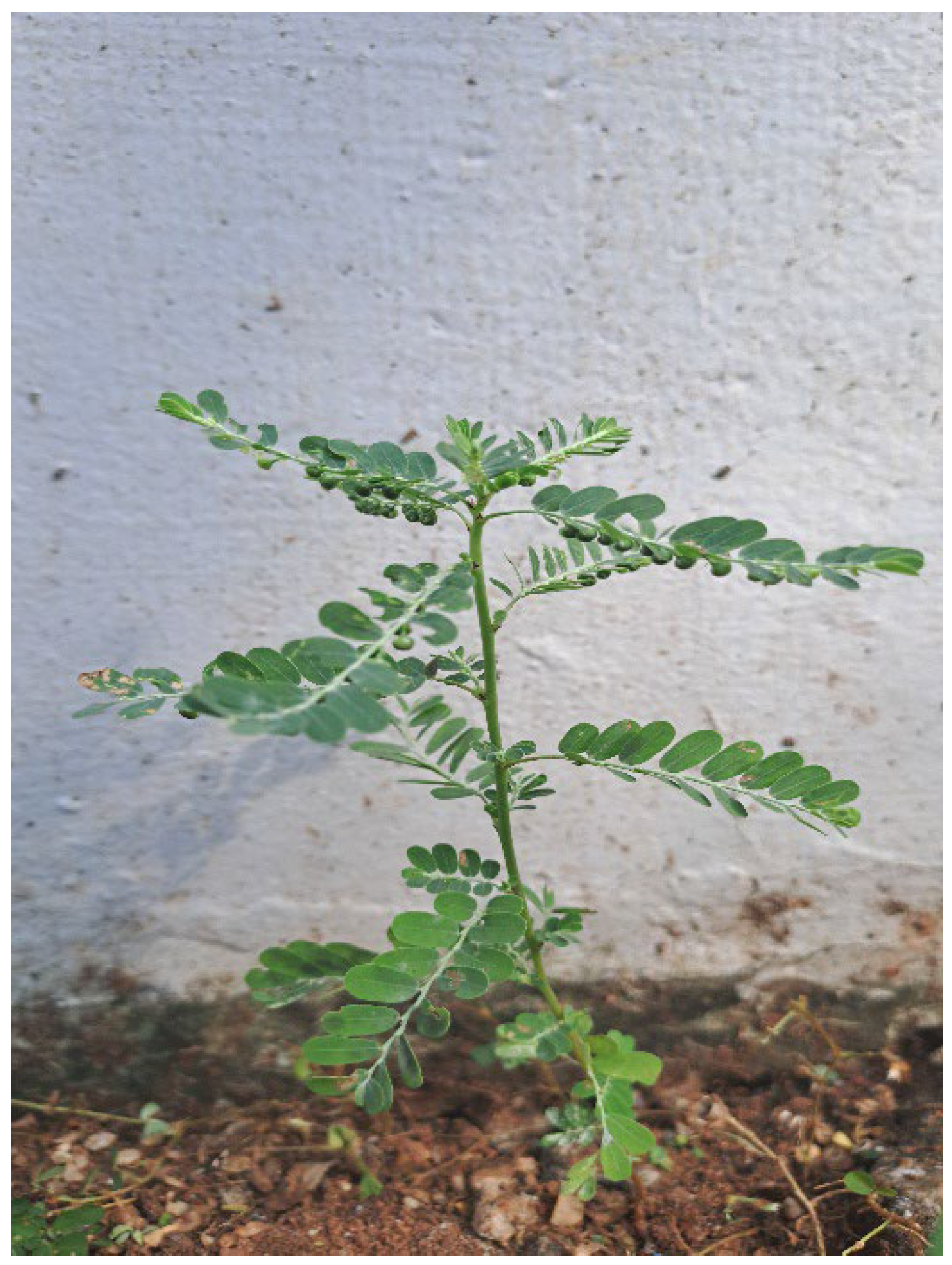

3.1. STONEBREAKER (Phyllanthus amarus):

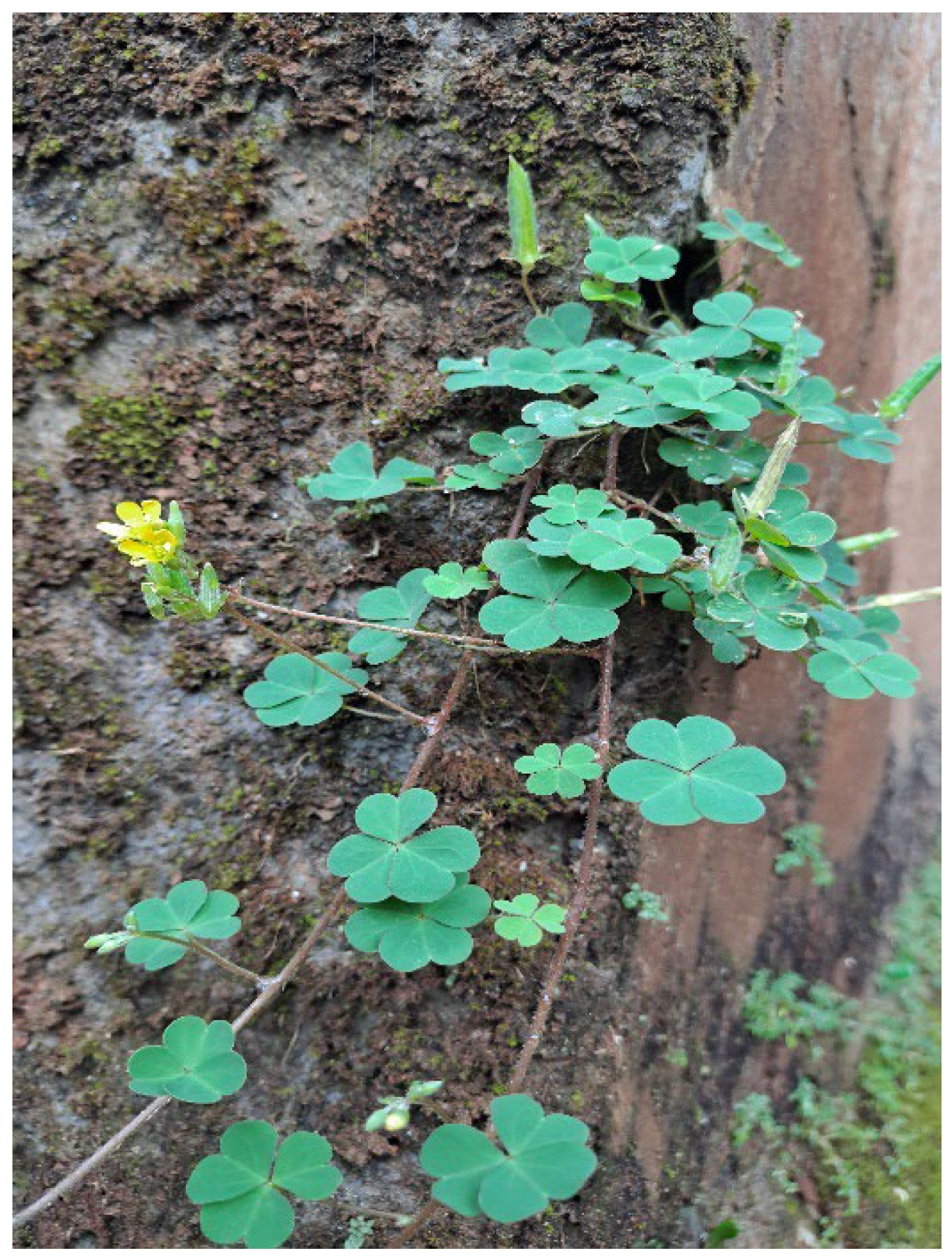

3.2. CREEPING WOODSORREL (Oxalis corniculata):

3.3. LITTLE TREE PLANT (Biophytum sensitivum):

3.4. MALABAR NUT (Justicia adhatoda):

3.5. ASTHMA- PLANT (Euphorbia hirta):

3.6. INDIAN GOOSEBERRY (Phyllanthus emblica):

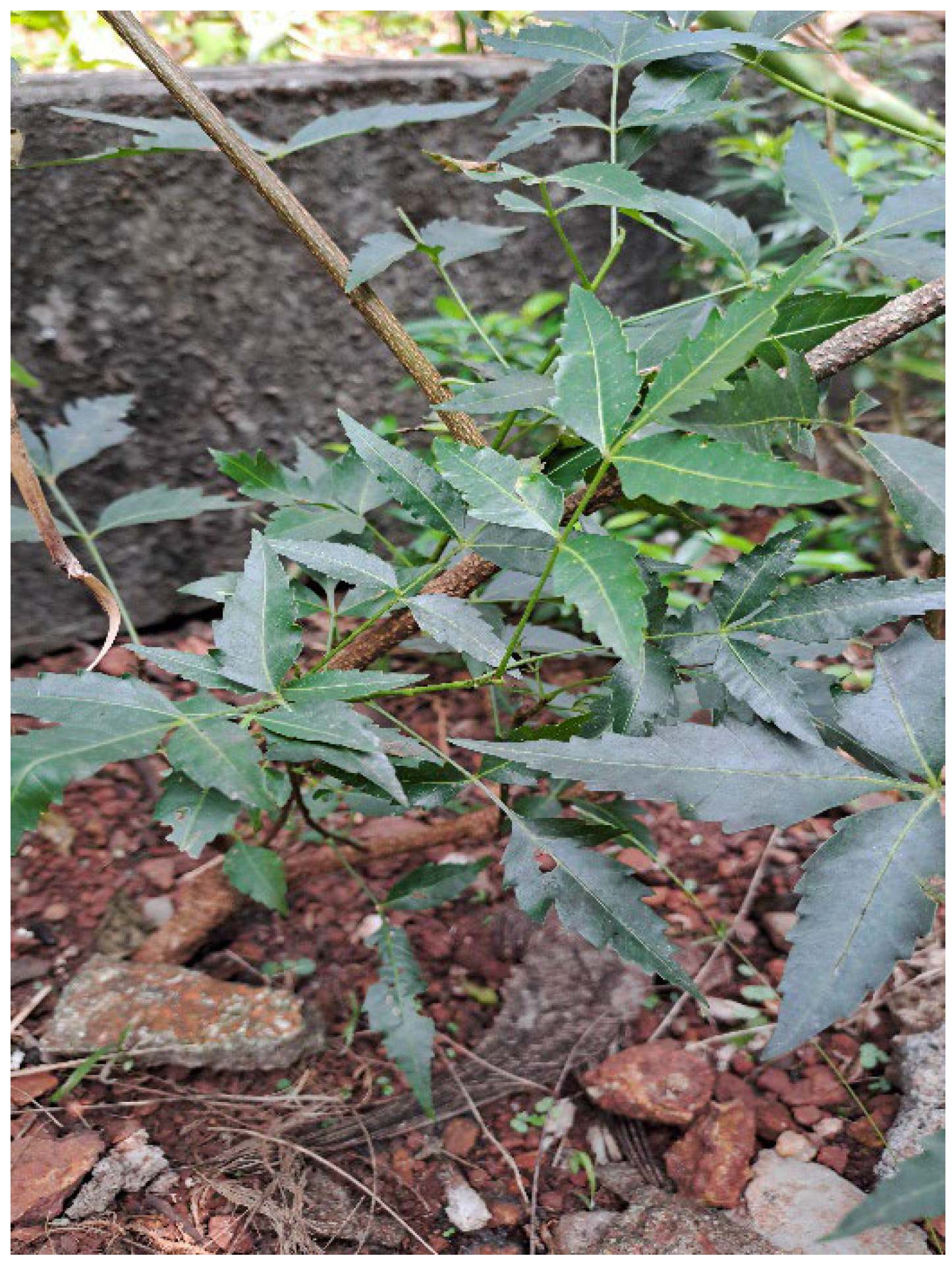

3.7. NEEM (Azadirachta indica):

3.8. INDIAN BORAGE (Plectranthus amboinicus):

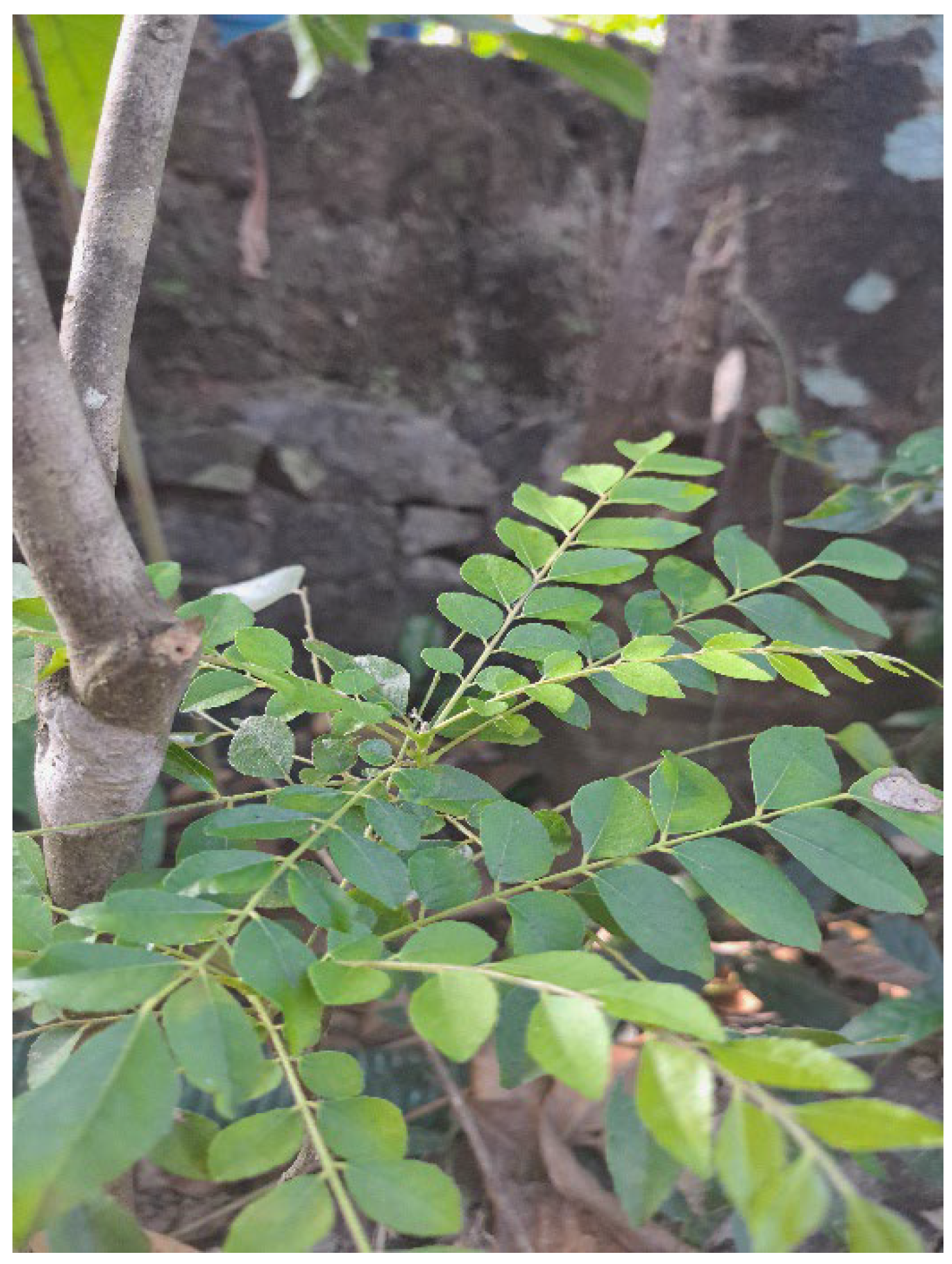

3.9. CURRY LEAF (Murraya koenigii):

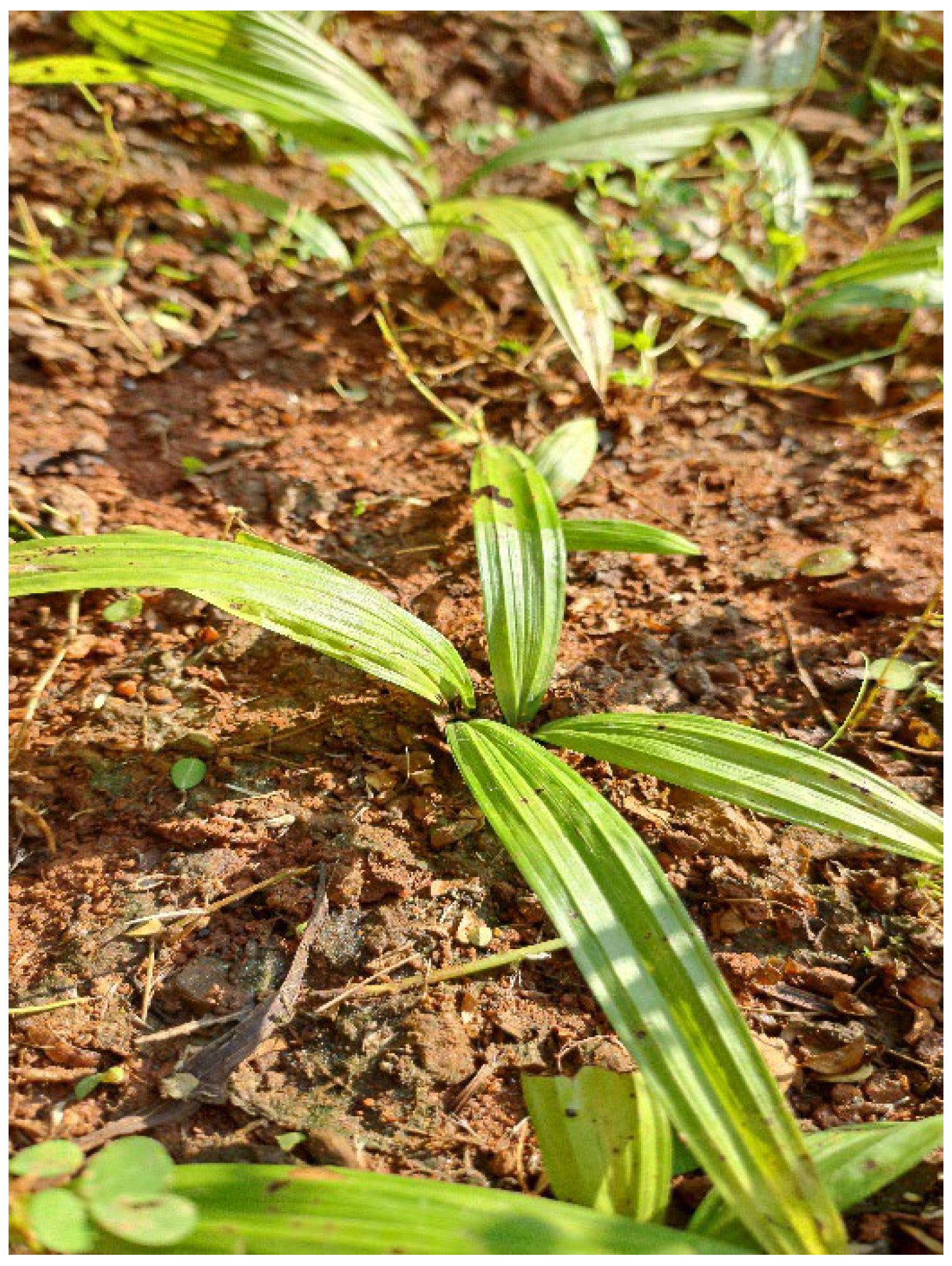

3.10. BLACK MUSLI (Curculigo orchioides):

4. Conclusion

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gupta SC, Patchva S, Koh W, Aggarwal BB. Discovery of curcumin, a component of golden spice, and its miraculous biological activities. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2012 Mar;39(3):283–99. [accessed 9 Dec 2024] Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22118895/.

- Turmeric (curcuma) exports by country |2022. [accessed 9 Dec 2024] Available from: https://wits.worldbank.org/trade/comtrade/en/country/ALL/year/2022/tradeflow/Exports/partner/WLD/product/091030.

- Ayurvedic Medicine: In Depth Is Ayurvedic Medicine Safe? Is Ayurvedic Medicine Effective? Available from: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/ayurvedic-medicine-in-depth.

- Tannenbaum A, Silverstone H. Nutrition in Relation to Cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 1953 Jan 1;1(C):451–501. [CrossRef]

- Variar PR. THE AYURVEDIC HERITAGE OF KERALA. Anc Sci Life. 1985 Jul;5(1):54. [accessed 10 Dec 2024] Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3331432/.

- Indian Systems of Medicine - Home. [accessed 28 Jan 2025] Available from: https://www.ism.kerala.gov.in/eng/.

- State Medicinal Plants Board Kerala | SMPB Kerala. [accessed 28 Jan 2025] Available from: https://smpbkerala.in/.

- Nguyen VT, Sakoff JA, Scarlett CJ. Physicochemical Properties, Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Activities of Crude Extracts and Fractions from Phyllanthus amarus. Medicines. 2017 Jun 18;4(2):42. [accessed 21 Dec 2024] Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5590078/.

- Mohamed SIA, Jantan I, Nafiah MA, Seyed MA, Chan KM. Lignans and Polyphenols of Phyllanthus amarus Schumach and Thonn Induce Apoptosis in HCT116 Human Colon Cancer Cells through Caspases-Dependent Pathway. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2021 Jun 13;22(2):262–73. [accessed 21 Dec 2024] Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32532192/.

- Rajeshkumar N V., Joy KL, Kuttan G, Ramsewak RS, Nair MG, Kuttan R. Antitumour and anticarcinogenic activity of Phyllanthus amarus extract. J Ethnopharmacol. 2002 Jun 1;81(1):17–22. [CrossRef]

- Rajeshkumar N V., Kuttan R. Phyllanthus amarus extract administration increases the life span of rats with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Ethnopharmacol. 2000;73(1–2):215–9. [accessed 21 Dec 2024] Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11025159/.

- Gholipour AR, Jafari L, Ramezanpour M, Evazalipour M, Chavoshi M, Yousefbeyk F, et al. Apoptosis Effects of Oxalis corniculata L. Extract on Human MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cell Line: -. Galen Medical Journal. 2022 Oct 31;11:e2484. [accessed 22 Dec 2024] Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9838112/.

- Bharti R, Mujwar S, Priyanka, Gurjeet Singh T, Khatri N. A computational approach for screening of phytochemicals from Oxalis corniculata as promising anti-cancer candidates. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2024 Oct 1;36(9):103383. [CrossRef]

- Gudasi S, Gharge S, Koli R, Patil K. Antioxidant properties and cytotoxic effects of Oxalis corniculata on human Hepatocarcinoma (Hep-G2) cell line: an in vitro and in silico evaluation. Future Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2023 9:1. 2023 Mar 28;9(1):1–13. [accessed 22 Dec 2024] Available from: https://fjps.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s43094-023-00476-2.

- Sakthivel KM, Guruvayoorappan C. Biophytum sensitivum: Ancient medicine, modern targets. J Adv Pharm Technol Res. 2012;3(2):83. [accessed 25 Dec 2024] Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3401679/.

- Guruvayoorappan C, Kuttan G. Biophytum sensitivum (L.) DC Inhibits Tumor Cell Invasion and Metastasis Through a Mechanism Involving Regulation of MMPs, Prolyl Hydroxylase, Lysyl Oxidase, nm23, ERK-1, ERK-2, STAT-1, and Proinflammatory Cytokine Gene Expression in Metastatic Lung Tissue. 2008 Mar 1;7(1):42–50. [accessed 26 Dec 2024] Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1534735407313744. [CrossRef]

- Amentoflavone stimulates apoptosis in B16F-10 melanoma cells by regulating bcl-2, p53 as well as caspase-3 genes and regulates the nitric oxide as well as proinflammatory cytokine production in B16F-10 melanoma cells, tumor associated macrophages and peritoneal macrophages. | EBSCOhost. [accessed 26 Dec 2024] Available from: https://openurl.ebsco.com/EPDB%3Agcd%3A11%3A24088507/detailv2?sid=ebsco%3Aplink%3Ascholar&id=ebsco%3Agcd%3A35424684&crl=c&link_origin=scholar.google.com.

- Immunomodulatory and antitumor activity of Biophytum sensitivum extract - PubMed. [accessed 25 Dec 2024] Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17477767/.

- Santhi MP, Saravanan K, Karuppannan P. In Vitro Anticancer Activity of Biophytum sensitivum on Liver Cancer Lines (HEPG2). Drug Development for Cancer and Diabetes. 2020 Aug 30;191–7. [accessed 26 Dec 2024] Available from: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9780429330490-16/vitro-anticancer-activity-biophytum-sensitivum-liver-cancer-lines-hepg2-santhi-saravanan-karuppannan.

- Gulfraz M, Arshad M, Nayyer N, Kanwal N, Nisar U. Investigation for Bioactive Compounds of Berberis Lyceum Royle and Justicia Adhatoda L. Ethnobotanical Leaflets. 2004 Jan 1;2004(1). [accessed 27 Dec 2024] Available from: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/ebl/vol2004/iss1/5.

- Kumar S, Singh R, Dutta D, Chandel S, Bhattacharya A, Ravichandiran V, et al. In Vitro Anticancer Activity of Methanolic Extract of Justicia adhatoda Leaves with Special Emphasis on Human Breast Cancer Cell Line. Molecules. 2022 Dec 1;27(23):8222. [accessed 27 Dec 2024] Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/27/23/8222/htm.

- East African Scholars Journal of Medical Sciences Abbreviated Key Title: East African Scholars J Med Sci. Available from: http://www.easpublisher.com/easjms/.

- Latha D, Prabu P, Arulvasu C, Manikandan R, Sampurnam S, Narayanan V. Enhanced cytotoxic effect on human lung carcinoma cell line (A549) by gold nanoparticles synthesized from Justicia adhatoda leaf extract. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2018 Nov 1;8(11):540–7. [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman CT, Deepak M, Praveen TK, Lijini KR, Salman M, Sadheeshnakumari S, et al. Metabolite profiling and anti-cancer activity of two medicinally important Euphorbia species. Medicine in Omics. 2023 Mar;7:100018. [accessed 15 Feb 2025] Available from: https://www.aryavaidyasala.com/blogs/two-plants-in-cancer-treatment-breakthrough-in-arya-vaidya-salas-research/.

- Ghosh P, Ghosh C, Das S, Das C, Mandal S, Chatterjee S. Botanical Description, Phytochemical Constituents and Pharmacological Properties of Euphorbia hirta Linn: A Review. International Journal of Health Sciences & Research (www.ijhsr.org). 2019;9:273. [accessed 29 Dec 2024] Available from: www.ijhsr.org.

- Sulaiman CT, Deepak M, Praveen TK, Lijini KR, Salman M, Sadheeshnakumari S, et al. Metabolite profiling and anti-cancer activity of two medicinally important Euphorbia species. Medicine in Omics. 2023 Mar 1;7:100018. [CrossRef]

- Patil SB, Magdum CS. Phytochemical investigation and antitumour activity of Euphorbia hirta Linn. Eur J Exp Biol. 2011;1(1):51–6. [accessed 29 Dec 2024] Available from: www.pelagiaresearchlibrary.com.

- Kwan YP, Saito T, Ibrahim D, Al-Hassan FMS, Ein Oon C, Chen Y, et al. Evaluation of the cytotoxicity, cell-cycle arrest, and apoptotic induction by Euphorbia hirta in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Pharm Biol. 2016 Jul 2;54(7):1223–36. [accessed 29 Dec 2024] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3109/13880209.2015.1064451.

- Jung OB, In GH, Tae MK, Bang YH, Ung SL, Jeong HS, et al. Anti-proliferate and pro-apoptotic effects of 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6- methyl-4H-pyranone through inactivation of NF-κB in human colon cancer cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2007 Nov 30;30(11):1455–63. [accessed 29 Dec 2024] Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF02977371.

- Sharma N, Samarakoon KW, Gyawali R, Park YH, Lee SJ, Oh SJ, et al. Evaluation of the Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, and Anticancer Activities of Euphorbia hirta Ethanolic Extract. Molecules. 2014 Sep 15;19(9):14567. [accessed 29 Dec 2024] Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6271915/.

- Anitha P, Geegi P, Yogeswari J, Anthoni S. In Vitro Anticancer Activity of Ethanolic Extract of Euphorbia hirta (L.). Science, Technology and Arts Research Journal. 2014 Jun 4;3(1):01–7. [accessed 29 Dec 2024] Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/star/article/view/104009.

- Prananda AT, Dalimunthe A, Harahap U, Simanjuntak Y, Peronika E, Karosekali NE, et al. Phyllanthus emblica: a comprehensive review of its phytochemical composition and pharmacological properties. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1288618. [accessed 4 Jan 2025] Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10637531/.

- Chanda S, Biswas SM, Kumar Sarkar P, State JBR. Phytochemicals and antiviral properties of five dominant medicinal plant species in Bankura district, West Bengal: An overview. ~ 1420 ~ Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry. 2020;9(6):1420–7. [accessed 4 Jan 2025] Available from: www.phytojournal.com.

- Estimation of resveratrol in few native fruits of north-east India | Request PDF. [accessed 4 Jan 2025] Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281675812_Estimation_of_resveratrol_in_few_native_fruits_of_north-east_India.

- Liu X, Zhao M, Wu K, Chai X, Yu H, Tao Z, et al. Immunomodulatory and anticancer activities of phenolics from emblica fruit (Phyllanthus emblica L.). Food Chem. 2012 Mar 15;131(2):685–90. [CrossRef]

- Zhang YJ, Nagao T, Tanaka T, Yang CR, Okabe H, Kouno I. Antiproliferative Activity of the Main Constituents from Phyllanthus emblica. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004 Feb;27(2):251–5. [CrossRef]

- Jose JK, Kuttan G, Kuttan R. Antitumour activity of Emblica officinalis. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001 May 1;75(2–3):65–9. [CrossRef]

- Mahata S, Pandey A, Shukla S, Tyagi A, Husain SA, Das BC, et al. Anticancer Activity of Phyllanthus emblica Linn. (Indian Gooseberry): Inhibition of Transcription Factor AP-1 and HPV Gene Expression in Cervical Cancer Cells. Nutr Cancer. 2013 Oct 1;65(SUPPL.1):88–97. [accessed 7 Jan 2025] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01635581.2013.785008.

- Chekdaengphanao P, Jaiseri D, Sriraj P, Aukkanimart R, Prathumtet J, Udonsan P, et al. Anticancer activity of Terminalia chebula, Terminalia bellirica, and Phyllanthus emblica extracts on cholangiocarcinoma cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis. J Herb Med. 2022 Sep 1;35:100582. [CrossRef]

- Ngamkitidechakul C, Jaijoy K, Hansakul P, Soonthornchareonnon N, Sireeratawong S. Antitumour effects of phyllanthus emblica L.: Induction of cancer cell apoptosis and Inhibition of in vivo tumour promotion and in vitro invasion of human cancer cells. Phytotherapy Research. 2010 Sep 1;24(9):1405–13. [accessed 9 Jan 2025] Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ptr.3127.

- Khanal S. Qualitative and Quantitative Phytochemical Screening of Azadirachta indica Juss. Plant Parts. Int J Appl Sci Biotechnol. 2021 Jun 28;9(2):122–7. [accessed 12 Jan 2025] Available from: https://www.nepjol.info/index.php/IJASBT/article/view/38050.

- Alzohairy MA. Therapeutics Role of Azadirachta indica (Neem) and Their Active Constituents in Diseases Prevention and Treatment. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:7382506. [accessed 12 Jan 2025] Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4791507/.

- Paul R, Prasad M, Sah NK. Anticancer biology of Azadirachta indica L (neem): A mini review. www.landesbioscience.com Cancer Biology & Therapy. 2011;12(6):467–76. [accessed 14 Jan 2025] Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=kcbt20.

- Dkhil MA, Al-Quraishy S, Aref AM, Othman MS, El-Deib KM, Abdel Moneim AE. The Potential Role of Azadirachta indica Treatment on Cisplatin-Induced Hepatotoxicity and Oxidative Stress in Female Rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:741817. [accessed 14 Jan 2025] Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3867870/.

- Agrawal S, Bablani Popli D, Sircar K, Chowdhry A. A review of the anticancer activity of Azadirachta indica (Neem) in oral cancer. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2020 Apr 1;10(2):206–9. [CrossRef]

- Moga MA, Bălan A, Anastasiu CV, Dimienescu OG, Neculoiu CD, Gavriș C. An Overview on the Anticancer Activity of Azadirachta indica (Neem) in Gynecological Cancers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, Vol 19, Page 3898. 2018 Dec 5;19(12):3898. [accessed 14 Jan 2025] Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/19/12/3898/htm.

- Jeba Malar TRJ, Antonyswamy J, Vijayaraghavan P, Ock Kim Y, Al-Ghamdi AA, Elshikh MS, et al. In-vitro phytochemical and pharmacological bio-efficacy studies on Azadirachta indica A. Juss and Melia azedarach Linn for anticancer activity. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2020 Feb 1;27(2):682–8. [CrossRef]

- Guchhait KC, Manna T, Barai M, Karmakar M, Nandi SK, Jana D, et al. Antibiofilm and anticancer activities of unripe and ripe Azadirachta indica (neem) seed extracts. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2022 Dec 1;22(1):1–18. [accessed 15 Jan 2025] Available from: https://link.springer.com/articles/10.1186/s12906-022-03513-4.

- Alharbi NS, Alsubhi NS. Green synthesis and anticancer activity of silver nanoparticles prepared using fruit extract of Azadirachta indica. J Radiat Res Appl Sci. 2022 Sep 1;15(3):335–45. [CrossRef]

- Dutt Y, Pandey RP, Dutt M, Gupta A, Vibhuti A, Raj VS, et al. Silver Nanoparticles Phytofabricated through Azadirachta indica: Anticancer, Apoptotic, and Wound-Healing Properties. Antibiotics 2023, Vol 12, Page 121. 2023 Jan 9;12(1):121. [accessed 15 Jan 2025] Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2079-6382/12/1/121/htm.

- Nagini S, Palrasu M, Bishayee A. Limonoids from neem (Azadirachta indica A. Juss.) are potential anticancer drug candidates. Med Res Rev. 2024 Mar 1;44(2):457–96. [accessed 15 Jan 2025] Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/med.21988.

- Arumugam G, Swamy MK, Sinniah UR. Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour.) Spreng: Botanical, Phytochemical, Pharmacological and Nutritional Significance. Molecules 2016, Vol 21, Page 369. 2016 Mar 30;21(4):369. [accessed 16 Jan 2025] Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/21/4/369/htm.

- Asif Killedar M. Collection, extraction and phytochemical analysis of Indian borage leaves (Plectranthus amboinicus). ~ 52 ~ International Journal of Plant Pathology and Microbiology. 2024;4(2). [accessed 16 Jan 2025] Available from: https://doi.org/10.22271/27893065.2024.v4.i2a.93.

- Hasibuan PAZ, Sitorus P, Satria D. Anticancer activity of Β-sitosterol from Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour. Spreng.) leaves: In vitro and in silico studies. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research. 2017;10(5):306–8. [CrossRef]

- Manurung K, Sulastri D, Zubir N, Ilyas S. In silico Anticancer Activity and in vitro Antioxidant of Flavonoids in Plectranthus amboinicus. Pharmacognosy Journal. 2020 Nov 1;12(6s):1573–7. [CrossRef]

- Laila F, Fardiaz D, Yuliana ND, Damanik MRM, Nur Annisa Dewi F. Methanol Extract of Coleus amboinicus (Lour) Exhibited Antiproliferative Activity and Induced Programmed Cell Death in Colon Cancer Cell WiDr. Int J Food Sci. 2020 Jan 1;2020(1):9068326. [accessed 16 Jan 2025] Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1155/2020/9068326.

- Mujamammi AH, Sumaily KM, Alnomasy SF, Althafar ZM, AlAfaleq NO, Sabi EM. Phyto-fabrication and Characterization of Coleus amboinicus Inspired Copper Oxide Nanoparticles and Evaluation of Its Apoptotic and Anti-cancerous Activity Against Colon Cancer Cells (HCT 116). J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater. 2024 Jun 1;34(6):2581–95. [accessed 16 Jan 2025] Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10904-024-02997-6.

- Balakrishnan R, Vijayraja D, Jo SH, Ganesan P, Su-kim I, Choi DK. Medicinal Profile, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacological Activities of Murraya koenigii and its Primary Bioactive Compounds. Antioxidants 2020, Vol 9, Page 101. 2020 Jan 24;9(2):101. [accessed 17 Jan 2025] Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3921/9/2/101/htm.

- Igara C, Omoboyowa D, Ahuchaogu A, Orji N, Ndukwe M. Phytochemical and nutritional profile of Murraya Koenigii (Linn) Spreng leaf. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2016;5(5):07–9. [accessed 18 Jan 2025] Available from: https://www.phytojournal.com/archives/2016.v5.i5.931/phytochemical-and-nutritional-profile-of-murraya-koenigii-linn-spreng-leaf.

- Nagappan T, Ramasamy P, Wahid MEA, Segaran TC, Vairappan CS. Biological Activity of Carbazole Alkaloids and Essential Oil of Murraya koenigii Against Antibiotic Resistant Microbes and Cancer Cell Lines. Molecules 2011, Vol 16, Pages 9651-9664. 2011 Nov 21;16(11):9651–64. [accessed 18 Jan 2025] Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1420-3049/16/11/9651/htm.

- Arun A, Patel OPS, Saini D, Yadav PP, Konwar R. Anti-colon cancer activity of Murraya koenigii leaves is due to constituent murrayazoline and O-methylmurrayamine A induced mTOR/AKT downregulation and mitochondrial apoptosis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2017 Sep 1;93:510–21. [CrossRef]

- Iman V, Mohan S, Abdelwahab SI, Karimian H, Nordin N, Fadaeinasab M, et al. Anticancer and anti-inflammatory activities of girinimbine isolated from Murraya koenigii. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2017;11:103–21. [accessed 18 Jan 2025] Available from:. [CrossRef]

- Sanaye M, Pagare N, Pagare N, Pagare N. Evaluation of antioxidant effect and anticancer activity against human glioblastoma (U373MG) cell lines of Murraya Koenigii. Pharmacognosy Journal. 2016;8(3):220–5. [CrossRef]

- Bhatt S, Dadwal V, Padwad Y, Gupta M. Study of physicochemical, nutritional, and anticancer activity of Murraya Koenigii extract for its fermented beverage. J Food Process Preserv. 2022 Jan 1;46(1). [CrossRef]

- (PDF) Phytochemical Screening and Variation Studies in Secondary Metabolite Contents in Rhizomes of Curculigo orchioides from Madhya Pradesh State of India. [accessed 21 Jan 2025] Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/363090557_Phytochemical_Screening_and_Variation_Studies_in_Secondary_Metabolite_Contents_in_Rhizomes_of_Curculigo_orchioides_from_Madhya_Pradesh_State_of_India.

- Wu Q, Fu DX, Hou AJ, Lei GQ, Liu ZJ, Chen JK, et al. Antioxidative Phenols and Phenolic Glycosides from Curculigo orchioides. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 2005;53(8):1065–7. [CrossRef]

- Bhukta P, Ranajit SK, Kumar Sahu P, Rath D. Phytochemistry and pharmacology of Curculigo orchioides Gaertn: A review. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2023;13(10):83–091. [accessed 21 Jan 2025] Available from: http://www.japsonline.com.

- Xia LF, Liang SH, Wen H, Tang J, Huang Y. Anti-tumor effect of polysaccharides from rhizome of Curculigo orchioides Gaertn on cervical cancer. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2016 Sep 5;15(8):1731–7. [accessed 21 Jan 2025] Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/tjpr/article/view/143351.

- Venkatachalam P, Kayalvizhi T, Udayabanu J, Benelli G, Geetha N. Enhanced Antibacterial and Cytotoxic Activity of Phytochemical Loaded-Silver Nanoparticles Using Curculigo orchioides Leaf Extracts with Different Extraction Techniques. J Clust Sci. 2017 Jan 1;28(1):607–19. [accessed 21 Jan 2025] Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10876-016-1141-5.

- Kayalvizhi T, Ravikumar S, Venkatachalam P. Green Synthesis of Metallic Silver Nanoparticles Using Curculigo orchioides Rhizome Extracts and Evaluation of Its Antibacterial, Larvicidal, and Anticancer Activity. Journal of Environmental Engineering. 2009 Mar 15;142(9). [CrossRef]

- Hejazi II, Khanam R, Mehdi SH, Bhat AR, Rizvi MMA, Thakur SC, et al. Antioxidative and anti-proliferative potential of Curculigo orchioides Gaertn in oxidative stress induced cytotoxicity: In vitro, ex vivo and in silico studies. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2018 May 1;115:244–59. [CrossRef]

- Nanotechnology Cancer Therapy and Treatment - NCI. [accessed 8 Feb 2025] Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/nano/cancer-nanotechnology/treatment.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).