Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

16 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

The objectives of this study were to investigate extended exposure of ‘Gala’ apples to con-stant presence of ethanol and hexanal on the production of aroma compounds after long-term CA storage. 'Gala' apples were stored in CA under 2 kPa O2 and 98 kPa N2 at 1.0 ± 0.1 °C with a constant ethanol (CA-et) or hexanal (CA-he) concentration maintained at 50 µgL-1 throughout six month storage period. A total of 25 volatile compounds (VOCs) were identified. The Odor Activity Value (OAV) results showed that 9 VOCs were the key aroma compounds. Among them, hexyl acetate, 2-metyhbutyl acetate, and 1-butanol were the highest. Hexanal increased the production of hexyl acetate, while ethanol increased the production of 2-metyhlbutyl acetate and ethyl 2-methylbutanoate. Both precursors promoted the production of 1-butanol after two months of storage and 1 day of shelf life. Overall, the impact of the precursors on aroma production was more pronounced after two months than after six months of storage. Different storage atmosphere significantly influenced VOCs correlations, suggesting that ethanol and hexanal addition altered aro-ma biosynthesis pathways in ‘Gala’ apples. For varieties like ‘Gala’ that rapidly lose aroma during CA storage, CA-et and CA-he treatments may be beneficial for short-term storage, enhancing key aroma compounds and improving sensory quality.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant material and Storage Techniques

2.2. Ethylene Production and Respiratory Rate

2.3. Fruit Color

2.4. Ethylene Production and Respiratory Rate

2.5. Sample Preparation and Extraction of Volatile Compounds

2.6. Volatile Compunds Identificaton and Quantificicaton

2.7. Calculation of the Odor Activity Values

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Ethylene Production and Respiratory Rate

3.2. Fruit Color

3.3. Volatile Compounds Analysis

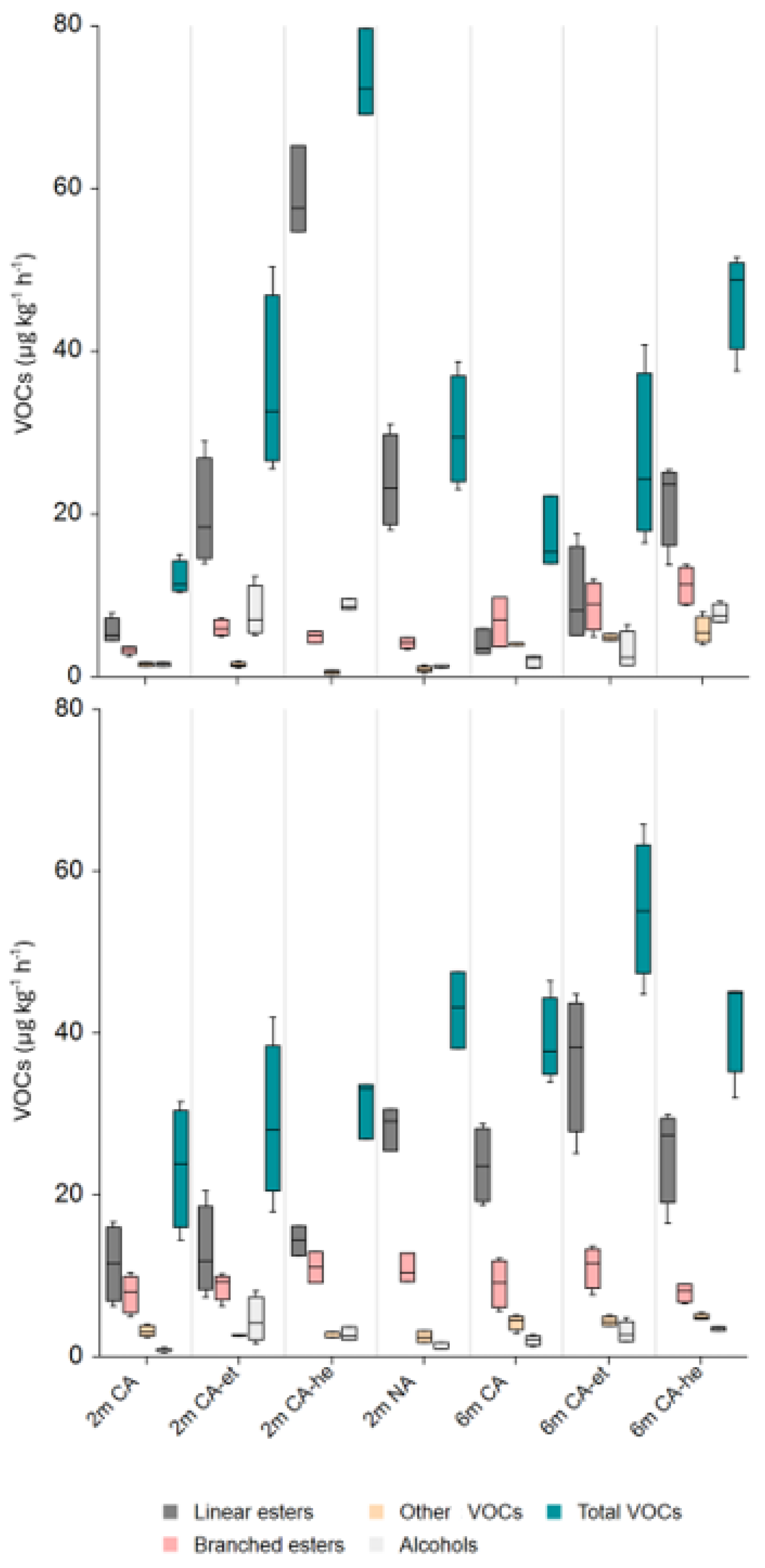

3.3.1. Total Volatile Compounds

3.3.2. Total Esters

3.3.3. Individual Esters

3.3.4. Total Alcohols

3.3.5. Individual Alcohols

3.3.6. Other Compounds

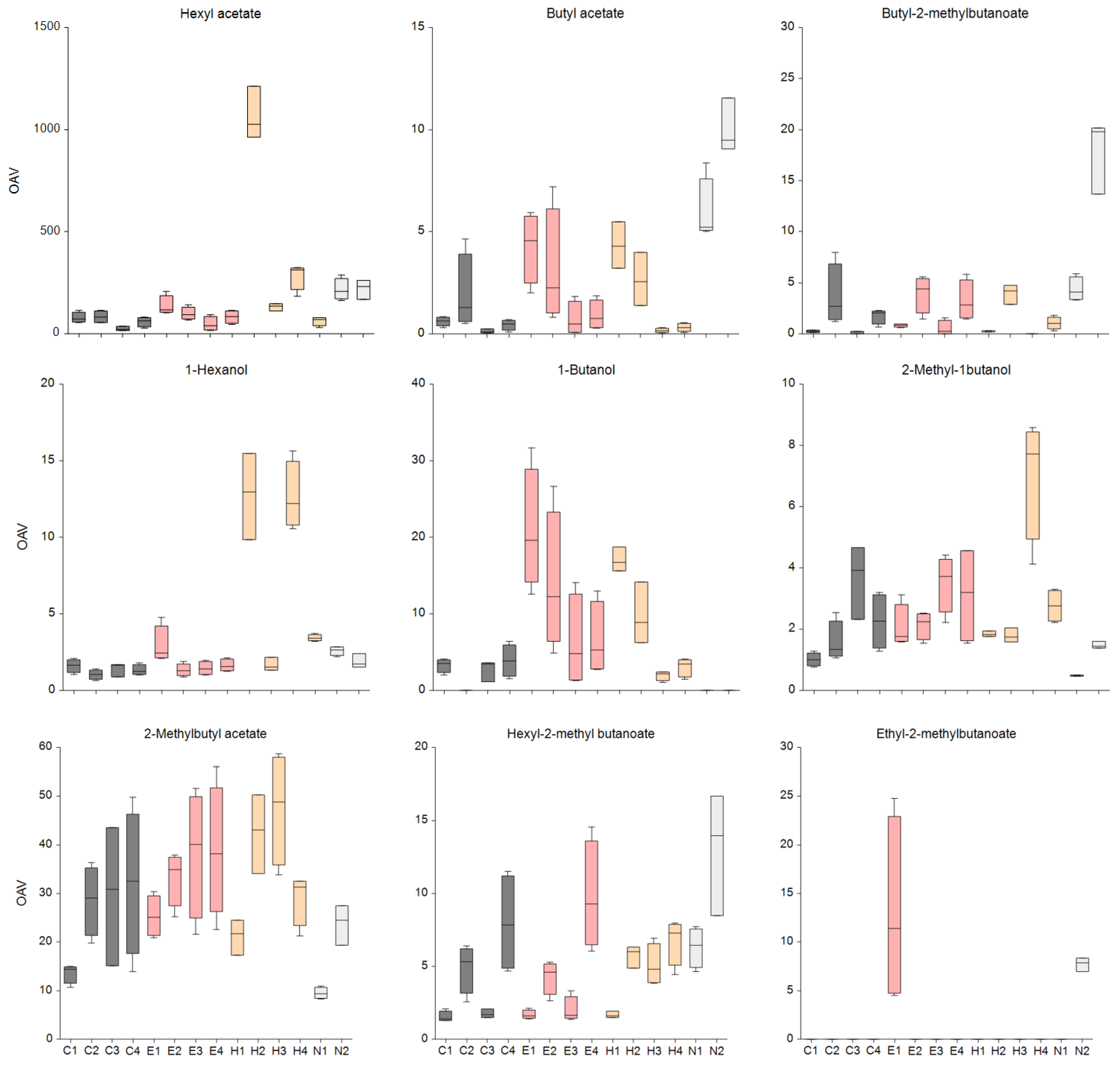

3.4. The Odor-Activity Values

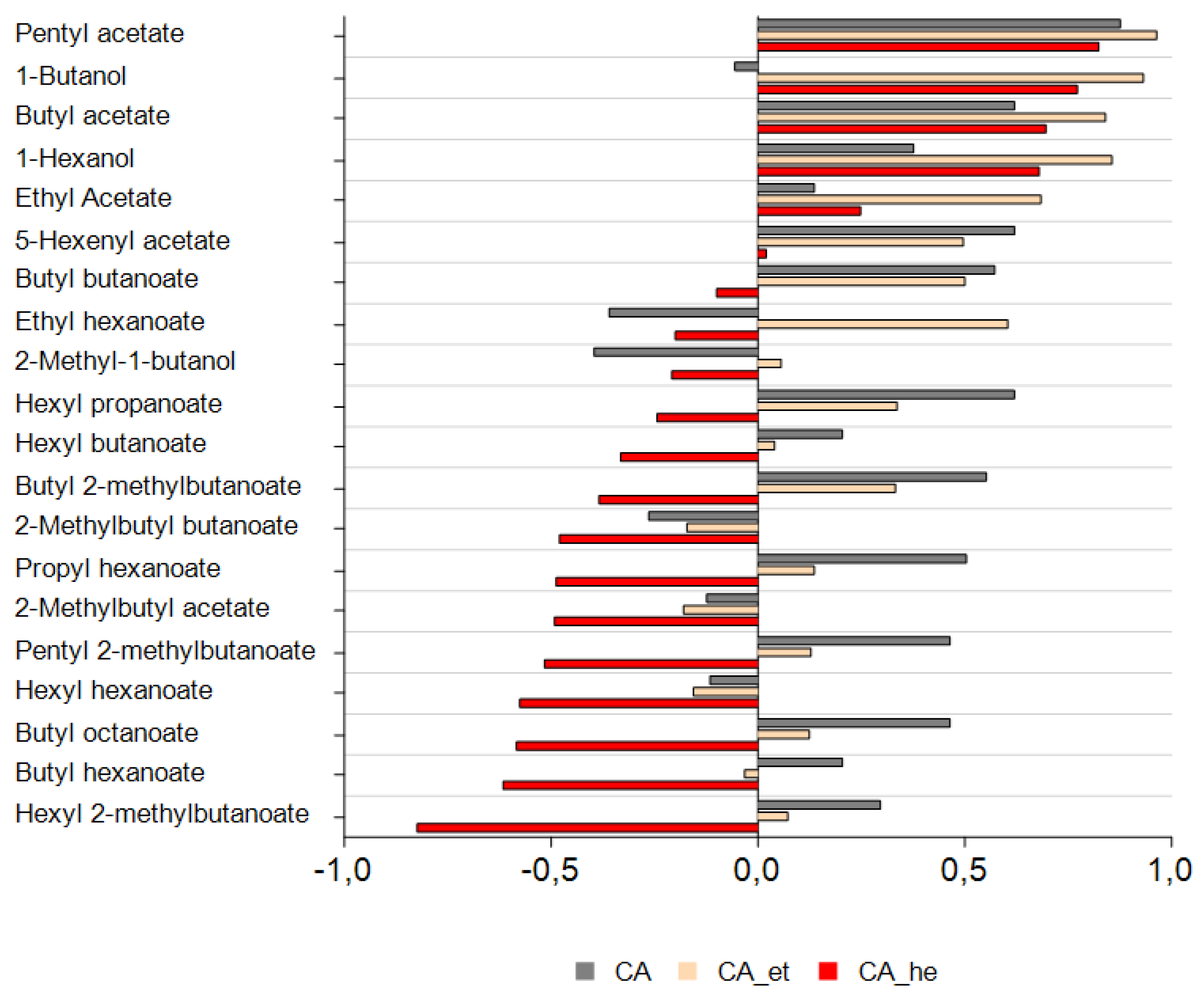

3.5. Correlation Analysis for Hexyl Acetate

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Identification | Retention Time (min) | Quantitative (first) and qualitative ions (m/z) |

| Ethyl Acetate | 10.31 | 61.0. 70.1, 87.9 |

| Ethanol | 11.96 | 31.1, 45.1 |

| 2-Pentanone | 13.76 | 86.2, 71.1, 58.1 |

| 2-Methylpropyl acetate | 15.05 | 73.1, 61.1, 86.2, 101.2 |

| Ethyl 2-methylbutanoate | 16.62 | 102.1, 57.1, 85.1, 115.0 |

| Butyl acetate | 17.52 | 61.0, 73.0, 87.0 |

| Hexanal | 18.00 | 72.1, 82.1, 67.1 |

| 2-Pentanol | 19.17 | 73.2, 58.1, 87.2 |

| 2-Methylbutyl acetate | 19.49 | 70.1, 55.1, 85.1, 101.0 |

| 1-Butanol | 20.19 | 56.1, 41.1, 73 |

| Butyl propoionate | 20.21 | 75.0, 87.1, 101.1 |

| Pentyl acetate | 21.52 | 70.2, 61.1, 101.1 |

| 2-Methyl-1-butanol | 22.61 | 70.1, 56.1, 42.1 |

| Butyl butanoate | 23.22 | 71.1, 89.1, 101.0, 116.1 |

| Butyl 2-methylbutanoate | 23.72 | 103.1, 85.1, 74.1, 130.1 |

| Ethyl hexanoate | 23.82 | 88.0, 99.1, 60.0, 73.0 |

| 2-Methylbutyl butanoate | 24.45 | 71.1, 55.0, 89.0 |

| Hexyl acetate | 25.02 | 84.0, 61.0, 69.0 |

| Propyl hexanoate | 26.96 | 99.0, 117.1, 71.1, 87.0 |

| Pentyl 2-methylbutanoate | 27.27 | 103.1, 85.0, 70.1 |

| 5-Hexenyl acetate | 27.34 | 67.0, 82.0, 54.1 |

| Hexyl propanoate | 27.69 | 75.1, 84.1, 69.1, 129.1 |

| 6-Methyl-5-heptene-2-one | 27.91 | 108.2, 69.1, 129.1 |

| 1-Hexanol | 28.03 | 56.1, 69.1, 84.1 |

| Butyl hexanoate | 30.30 | 99.1, 117.1, 71.1 |

| Hexyl butanoate | 30.38 | 71.1, 89.1, 84.1 |

| Hexyl 2-methylbutanoate | 30.72 | 103.1, 85.1, 69.1 |

| Benzaldehyde | 34.98 | 105.0, 77.0, 55.1, 73.0 |

| Hexyl hexanoate | 36.68 | 117.1, 99.1, 84.1 |

| Butyl octanoate | 36.79 | 127.1, 145.1, 73.0, 200.1 |

| Estragole | 39.20 | 148.1, 121.1 117.1 |

| α-Farnesene | 40.86 | 93.1, 107.1, 119.1, 189.2 |

Appendix A.2

| 1 day of shelf life at 20°C | 7 days of shelf life at 20°C | |||||||||||||||||

| NA | CA | CA-et | CA-he | NA | CA | CA-et | CA-he | |||||||||||

| VOC | Month of storage | avg | sd | avg | sd | avg | sd | avg | sd | avg | sd | avg | sd | avg | sd | avg | sd | |

| Linear esters | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ethyl Acetate (13500a)* | 2 | 0.03a | 0.01 | 0.02a | 0.00 | 6.87b | 2.89 | 0.12a | 0.05 | 0.16a | 0.05 | 0.11a | 0.13 | 0.52a | 0.87 | 0.07a | 0.03 | |

| 6 | 0.10a | 0.05 | 1.38b | 1.16 | 0.21a | 0.09 | 0.05a | 0.02 | 0.08b | 0.05 | 0.04a | 0.01 | ||||||

| Butyl acetate (66a) | 2 | 5.28a | 1.42 | 0.53b | 0.20 | 3.78a | 1.52 | 3.83a | 1.01 | 8.88b | 1.18 | 1.71a | 1.66 | 2.77a | 2.51 | 2.34a | 1.16 | |

| 6 | 0.10a | 0.09 | 0.63a | 0.75 | 0.14a | 0.09 | 0.39a | 0.22 | 0.80a | 0.65 | 0.26a | 0.18 | ||||||

| Butyl propionate (25g) | 2 | 0.51b | 0.11 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.74b | 0.07 | 0.20a | 0.17 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | |

| 6 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | ||||||

| Pentyl acetate (43b) | 2 | 0.45ac | 0.13 | 0.28a | 0.05 | 0.61bc | 0.19 | 0.79b | 0.10 | 0.72a | 0.04 | 0.41a | 0.20 | 0.46a | 0.12 | 0.46a | 0.06 | |

| 6 | 0.07a | 0.04 | 0.17a | 0.13 | 0.52b | 0.13 | 0.22a | 0.10 | 0.37a | 0.20 | 0.15a | 0.09 | ||||||

| Butyl butanoate (100la) | 2 | 1.57b | 0.55 | 0.09a | 0.04 | 0.37a | 0.07 | 0.28a | 0.10 | 1.51b | 0.16 | 0.65a | 0.46 | 0.66a | 0.26 | 0.56a | 0.10 | |

| 6 | 0.04a | 0.04 | 0.18a | 0.20 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.40a | 0.16 | 0.70a | 0.31 | 0.27a | 0.17 | ||||||

| Ethyl hexanoate (22 µg/lb) | 2 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.07b | 0.04 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | |

| 6 | 0.02a | 0.03 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.02a | 0.01 | 0.01a | 0.01 | ||||||

| Hexyl acetate (2a) | 2 | 10.77a | 2.66 | 3.93a | 1.30 | 6.78a | 2.38 | 53.07b | 6.50 | 10.95b | 2.32 | 4.07a | 1.61 | 4.90a | 1.58 | 6.51a | 0.89 | |

| 6 | 1.16a | 0.53 | 2.37a | 1.80 | 14.03b | 3.29 | 2.88a | 1.19 | 4.05a | 1.50 | 3.09a | 1.13 | ||||||

| Propyl hexanoate (nf) | 2 | 0.02b | 0.01 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.01a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.10a | 0.02 | 0.08a | 0.04 | 0.07a | 0.03 | 0.06a | 0.01 | |

| 6 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.06a | 0.03 | 0.11a | 0.03 | 0.04a | 0.05 | ||||||

| Hexyl propanoate (8b) | 2 | 0.35b | 0.05 | 0.02a | 0.01 | 0.04a | 0.02 | 0.09a | 0.03 | 0.35b | 0.11 | 0.15a | 0.07 | 0.16a | 0.05 | 0.14a | 0.01 | |

| 6 | 0.01a | 0.01 | 0.03a | 0.04 | 0.06a | 0.04 | 0.11a | 0.04 | 0.13a | 0.04 | 0.13a | 0.06 | ||||||

| Butyl hexanoate (700a) | 2 | 2.20b | 1.01 | 0.21a | 0.07 | 0.58a | 0.14 | 0.13a | 0.06 | 2.44a | 0.50 | 1.88a | 0.57 | 1.62a | 0.35 | 1.88a | 0.13 | |

| 6 | 0.32a | 0.19 | 0.86a | 0.72 | 0.09a | 0.04 | 3.51a | 0.55 | 6.38b | 1.13 | 2.45a | 0.92 | ||||||

| Hexyl butanoate (250b) | 2 | 1.33b | 0.53 | 0.23a | 0.04 | 0.37a | 0.08 | 0.66a | 0.15 | 1.13a | 0.53 | 0.66a | 0.18 | 0.57a | 0.12 | 0.64a | 0.08 | |

| 6 | 0.24a | 0.08 | 0.36a | 0.21 | 0.53a | 0.18 | 1.37a | 0.43 | 1.94a | 0.44 | 1.31a | 0.27 | ||||||

| Hexyl hexanoate (6400b) | 2 | 1.07b | 0.62 | 0.28a | 0.08 | 0.33a | 0.13 | 0.21a | 0.12 | 1.01a | 0.63 | 1.27a | 0.46 | 0.88a | 0.07 | 1.40a | 0.20 | |

| 6 | 2.05a | 0.74 | 3.64ab | 1.04 | 6.09b | 1.58 | 14.41a | 3.48 | 21.56a | 4.94 | 17.38a | 3.42 | ||||||

| Butyl octanoate (nf) | 2 | 0.27b | 0.13 | 0.04a | 0.01 | 0.09a | 0.04 | 0.01a | 0.01 | 0.37a | 0.17 | 0.25a | 0.10 | 0.23a | 0.09 | 0.26a | 0.02 | |

| 6 | 0.02a | 0.02 | 0.09a | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.22a | 0.04 | 0.42b | 0.13 | 0.16a | 0.07 | ||||||

| Branched esters | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2-Methylpropyl acetate (66a) | 2 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.11b | 0.04 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00b | 0.00 | 0.26a | 0.13 | 0.26a | 0.04 | 0.33a | 0.04 | |

| 6 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | ||||||

| Ethyl 2-methylbutanoate (0.06a) | 2 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.02b | 0.01 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.01b | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | |

| 6 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | ||||||

| 2-Methylbutyl acetate (11a) | 2 | 2.03a | 0.26 | 2.91a | 0.42 | 5.41b | 0.91 | 4.52b | 0.78 | 5.08a | 0.88 | 6.10ab | 1.54 | 7.10b | 1.19 | 9.07ab | 1.74 | |

| 6 | 6.38a | 3.04 | 8.18a | 2.79 | 10.15a | 2.48 | 6.87a | 3.19 | 8.27a | 2.92 | 6.21a | 1.15 | ||||||

| Butyl 2-methylbutanoate (17e) | 2 | 0.70a | 0.19 | 0.04a | 0.02 | 0.13b | 0.03 | 0.04b | 0.01 | 2.88b | 0.59 | 0.59a | 0.49 | 0.63a | 0.29 | 0.63a | 0.16 | |

| 6 | 0.01a | 0.02 | 0.08a | 0.12 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.28a | 0.12 | 0.52a | 0.32 | 0.17a | 0.10 | ||||||

| 2-Methylbutyl butanoate (17e) | 2 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | |

| 6 | 0.04a | 0.01 | 0.03a | 0.02 | 0.00b | 0.00 | 0.12a | 0.01 | 0.16b | 0.02 | 0.13a | 0.01 | ||||||

| Amyl 2-methylbutanoate (nf) | 2 | 0.02b | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.09b | 0.03 | 0.04a | 0.02 | 0.03a | 0.01 | 0.03a | 0.00 | |

| 6 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.03a | 0.01 | 0.04a | 0.02 | 0.01a | 0.01 | ||||||

| 5-Hexenyl acetate (7a) | 2 | 0.06ab | 0.02 | 0.03b | 0.00 | 0.06b | 0.02 | 0.06b | 0.01 | 0.07b | 0.01 | 0.06a | 0.01 | 0.07a | 0.01 | 0.09a | 0.01 | |

| 6 | 0.02a | 0.00 | 0.03a | 0.02 | 0.08b | 0.01 | 0.05a | 0.02 | 0.09a | 0.03 | 0.05a | 0.02 | ||||||

| Hexyl 2-methylbutanoate (22d) | 2 | 1.31b | 0.29 | 0.32a | 0.08 | 0.35a | 0.07 | 0.35a | 0.05 | 2.72b | 0.87 | 1.02a | 0.35 | 0.89a | 0.24 | 1.19a | 0.16 | |

| 6 | 0.36a | 0.06 | 0.42a | 0.18 | 1.06a | 0.30 | 1.66a | 0.71 | 2.04a | 0.78 | 1.41a | 0.33 | ||||||

| Alcohols | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ethanol (100000a) | 2 | 0.21a | 0.08 | 0.30a | 0.08 | 3.04b | 1.32 | 0.42a | 0.19 | 0.35a | 0.32 | 0.14a | 0.05 | 0.29a | 0.15 | 0.22a | 0.05 | |

| 6 | 0.43a | 0.15 | 0.45a | 0.06 | 0.55a | 0.05 | 0.54a | 0.06 | 0.85b | 0.18 | 0.52a | 0.02 | ||||||

| 2-Pentanol (nf) | 2 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.80b | 0.70 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 1.07a | 1.24 | 0.03a | 0.00 | |

| 6 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.61a | 1.12 | 1.21a | 0.26 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.77b | 0.11 | ||||||

| 1-Butanol (500a) | 2 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.55a | 0.15 | 3.51b | 1.34 | 2.86a | 0.27 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 2.35b | 1.54 | 1.64b | 0.68 | |

| 6 | 0.46 | 0.24 | 1.05a | 1.02 | 0.32a | 0.10 | 0.65a | 0.36 | 1.10a | 0.81 | 0.52a | 0.20 | ||||||

| 2-Methyl-1-butanol (250a) | 2 | 0.07a | 0.00 | 0.16ab | 0.03 | 0.32c | 0.11 | 0.29bc | 0.01 | 0.23a | 0.02 | 0.25a | 0.10 | 0.33a | 0.07 | 0.28a | 0.04 | |

| 6 | 0.57a | 0.19 | 0.55a | 0.15 | 1.10b | 0.31 | 0.35a | 0.14 | 0.49a | 0.26 | 0.43a | 0.08 | ||||||

| 1-Hexanol (500a) | 2 | 0.92a | 0.11 | 0.57a | 0.16 | 1.04a | 0.44 | 4.53b | 1.00 | 0.67a | 0.17 | 0.36a | 0.11 | 0.47a | 0.14 | 0.59a | 0.16 | |

| 6 | 0.50a | 0.16 | 0.51a | 0.17 | 4.49b | 0.79 | 0.47a | 0.12 | 0.57a | 0.15 | 1.22a | 0.08 | ||||||

| Other VOCs | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2-Pentanone (2300c) | 2 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00b | 0.00 | 0.09b | 0.03 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.03b | 0.01 | |

| 6 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 1.06b | 0.46 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.21b | 0.10 | ||||||

| Hexanal (5a) | 2 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.05b | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | |

| 6 | 0.17a | 0.10 | 0.08a | 0.03 | 0.27b | 0.08 | 0.06a | 0.03 | 0.06a | 0.01 | 0.06a | 0.01 | ||||||

| 6-Methyl-5-heptene-2-one (50a) | 2 | 0.01a | 0.00 | 0.01a | 0.00 | 0.01a | 0.00 | 0.01a | 0.01 | 0.01a | 0.00 | 0.03ab | 0.01 | 0.03ab | 0.00 | 0.04b | 0.01 | |

| 6 | 0.16a | 0.03 | 0.20a | 0.05 | 0.16a | 0.03 | 0.08a | 0.03 | 0.14b | 0.01 | 0.19c | 0.01 | ||||||

| Benzaldehyde (150c) | 2 | 0.02a | 0.01 | 0.02a | 0.00 | 0.02a | 0.01 | 0.02a | 0.01 | 0.02a | 0.01 | 0.02a | 0.00 | 0.03a | 0.02 | 0.03a | 0.03 | |

| 6 | 0.06a | 0.00 | 0.06a | 0.00 | 0.07b | 0.00 | 0.04a | 0.00 | 0.13a | 0.16 | 0.05a | 0.01 | ||||||

| Estragole (16b) | 2 | 0.22a | 0.11 | 0.38a | 0.08 | 0.45b | 0.14 | 0.19a | 0.04 | 0.59a | 0.32 | 0.78a | 0.28 | 0.76a | 0.18 | 0.61a | 0.06 | |

| 6 | 0.98a | 0.32 | 0.79a | 0.11 | 0.91a | 0.33 | 0.61a | 0.36 | 0.64a | 0.38 | 0.33a | 0.13 | ||||||

| α-Farnesene (nf) | 2 | 0.73ab | 0.44 | 1.14a | 0.16 | 0.98a | 0.20 | 0.25b | 0.23 | 1.84a | 0.49 | 2.32a | 0.49 | 1.79a | 0.11 | 2.07a | 0.39 | |

| 6 | 2.92a | 0.44 | 3.78a | 0.29 | 3.52b | 0.84 | 3.54a | 1.20 | 3.51a | 0.40 | 4.15a | 0.09 | ||||||

References

- FAOSTAT. (2022). Crop production data. Available at: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (August 2024). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- El Hadi, M.A.M.; Zhang, F.J.; Wu, F.F.; Zhou, C.H.; Tao, J. Advances in Fruit Aroma Volatile Research. Molecules 2013, 18, 8200–8229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Hao, N.; Meng, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Z. Identification, Comparison and Classification of Volatile Compounds in Peels of 40 Apple Cultivars by Hs–Spme with Gc–Ms. Foods 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino-Díaz, M.; Sepúlveda, D.R.; González-Aguilar, G.; Olivas, G.I. Biochemistry of Apple Aroma: A Review. Food Technol Biotechnol 2016, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Li, D.; Li, S.; Yang, H.; Zhao, Z. GC-MS Metabolite and Transcriptome Analyses Reveal the Differences of Volatile Synthesis and Gene Expression Profiling between Two Apple Varieties. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souleyre, E.J.F.; Chagné, D.; Chen, X.; Tomes, S.; Turner, R.M.; Wang, M.Y.; Maddumage, R.; Hunt, M.B.; Winz, R.A.; Wiedow, C.; et al. The AAT1 Locus Is Critical for the Biosynthesis of Esters Contributing to “ripe Apple” Flavour in “Royal Gala” and “Granny Smith” Apples. Plant Journal 2014, 78, 903–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souleyre, E.J.F.; Greenwood, D.R.; Friel, E.N.; Karunairetnam, S.; Newcomb, R.D. An Alcohol Acyl Transferase from Apple (Cv. Royal Gala), MpAAT1, Produces Esters Involved in Apple Fruit Flavor. FEBS Journal 2005, 272, 3132–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Both, V.; Thewes, F.R.; Brackmann, A.; Ferreira, D. de F.; Pavanello, E.P.; Wagner, R. Effect of Low Oxygen Conditioning and Ultralow Oxygen Storage on the Volatile Profile, Ethylene Production and Respiration Rate of ‘Royal Gala’ Apples. Sci Hortic 2016, 209, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriskantharajah, K.; El Kayal, W.; Ayyanath, M.M.; Saxena, P.K.; Sullivan, A.J.; Paliyath, G.; Subramanian, J. Preharvest Spray Hexanal Formulation Enhances Postharvest Quality in ‘Honeycrisp’ Apples by Regulating Phospholipase d and Calcium Sensor Proteins Genes. Plants 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thewes, F.R.; Balkees, B.M.; Büchele, F.; Wünsche, J.N.; Neuwald, D.A.; Brackmann, A. Ethanol Vapor Treatment Inhibits Apple Ripening at Room Temperature Even with the Presence of Ethylene. Postharvest Biol Technol 2021, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, R.G.; Drawert, F. Changes in the Composition of Volatiles by Post-harvest Application of Alcohols to Red Delicious Apples. J Sci Food Agric 1984, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thewes, F.R.; Brackmann, A.; Both, V.; Ludwig, V.; Wendt, L.M.; Thewes, F.R.; Soldateli, F.J. Dynamics of Ethanol and Its Metabolites in Fruit: The Impact of the Temperature and Fruit Species. Postharvest Biol Technol 2023, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yumbya, P.; Ambuko, J.; Hutchinson, M.; Owino, W.; Juma, J.; Machuka, E.; Mutuku, J.M. Transcriptome Analysis to Elucidate Hexanal’s Mode of Action in Preserving the Post-Harvest Shelf Life and Quality of Banana Fruits (Musa Acuminata). J Agric Food Res 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, V.; Kizhaeral S, S.; Subramanian, M.; Rajendran, S.; Ranjan, J. Encapsulation of a Volatile Biomolecule (Hexanal) in Cyclodextrin Metal-Organic Frameworks for Slow Release and Its Effect on Preservation of Mangoes. ACS Food Science and Technology 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, S.; Chandrasekaran, R.; Paliyath, G.; Lim, L.T.; Subramanian, J. Effect of Hexanal Loaded Electrospun Fiber in Fruit Packaging to Enhance the Post Harvest Quality of Peach. Food Packag Shelf Life 2020, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowan, D.D.; Allen, J.M.; Fielder, S.; Hunt, M.B. Biosynthesis of Straight-Chain Ester Volatiles in Red Delicious and Granny Smith Apples Using Deuterium-Labeled Precursors. J Agric Food Chem 1999, 47, 2553–2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, L.; Song, J.; Beaudry, R.M.; Hildebrand, P.D. Effect of Hexanal Vapor on Spore Viability of Penicillin Expansum, Lesion Development on Whole Apples and Fruit Volatile Biosynthesis. J Food Sci 2006, 71, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2621.2006.tb15632.x.44. Ferenczi, A.; Sugimoto, N.; Beaudry, R.M. Emission Patterns of Esters and Their Precursors throughout Ripening and Senescence in ‘Redchief Delicious’ Apple Fruit and Implications Regarding Biosynthesis and Aroma Perception. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 2021, 146, 297–328, doi:10.21273/JASHS05064-21.

- Harb, J.; Streif, J.; Bangerth, F. Response of Controlled Atmosphere (CA) Stored “Golden Delicious” Apples to the Treatments with Alcohols and Aldehydes as Aroma Precursors. Gartenbauwissenschaft 2000, 65, 154–161. [Google Scholar]

- Sander, R. : Compilation of Henry's law constants (version 4.0) for water as solvent, Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 4399–4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Both, V.; Brackmann, A.; Thewes, F.R.; Ferreira, D.D.F.; Wagner, R. Effect of Storage under Extremely Low Oxygen on the Volatile Composition of “Royal Gala” Apples. Food Chem 2014, 156, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saquet, A.A.; Streif, J. Respiration Rate and Ethylene Metabolism of ‘Jonagold’ Apple and ‘Conference’ Pear under Regular Air and Controlled Atmosphere. Bragantia 2017, 76, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.; Neuwald, D.A.; Kittemann, D.; Thewes, F.R.; Both, V.; Brackmann, A. Influence of Respiratory Quotient Dynamic Controlled Atmosphere (DCA – RQ) and Ethanol Application on Softening of Braeburn Apples. Food Chem 2020, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, S.F.P.; Schultz, E.E.; Ludwig, V.; Berghetti, M.R.P.; Thewes, F.R.; Anese, R. de O.; Both, V.; Brackmann, A. Volatile Compounds and Overall Quality of ‘Braeburn’ Apples after Long-Term Storage: Interaction of Innovative Storage Technologies and 1-MCP Treatment. Sci Hortic 2020, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.; Brackmann, A.; Both, V.; Pavanello, E.P.; Anese, R.O.; Schorr, M.R.W. Ethanol Reduces Ripening of ‘Royal Gala’ Apples Stored in Controlled Atmosphere. An Acad Bras Cienc 2016, 88, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thewes, F.R.; Balkees, B.M.; Büchele, F.; Both, V.; Brackmann, A.; Neuwald, D.A. The Isolated and Combined Impacts of Ethanol and Ethylene Application on Sugars and Organic Acids Dynamics in ‘Elstar’ and ‘Nicoter’ Apples. Postharvest Biol Technol 2022, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, K.; Paliyath, G. Microarray Analysis of Ripening-Regulated Gene Expression and Its Modulation by 1-MCP and Hexanal. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2011, 49, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.Y.; Hu, X.L.; Li, X.; Li, Y.H.; Paliyath, G. Effect of Hexanal Treatment on Postharvest Quality of “Darselect” Strawberry (Fragaria ×ananassa Duch.) Fruit. Acta Hortic 2009, 839, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Dhami, P.; Pandey, P. Flavors of Apple Fruit—A Review. J Nutr Ecol Food Res 2016, 2, 288–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silué, Y.; Nindjin, C.; Cissé, M.; Kouamé, K.A.; Amani, N. guessan G.; Mbéguié-A-Mbéguié, D.; Lopez-Lauri, F.; Tano, K. Hexanal Application Reduces Postharvest Losses of Mango (Mangifera Indica L. Variety “Kent”) over Cold Storage Whilst Maintaining Fruit Quality. Postharvest Biol Technol 2022, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, A.; Padmanabhan, P.; Subramanian, J.; Blom, T.; Paliyath, G. Improving Quality of Greenhouse Tomato (Solanum Lycopersicum L.) by Pre- and Postharvest Applications of Hexanal-Containing Formulations. Postharvest Biol Technol 2014, 95, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Both, V.; Thewes, F.R.; Brackmann, A.; de Oliveira Anese, R.; de Freitas Ferreira, D.; Wagner, R. Effects of Dynamic Controlled Atmosphere by Respiratory Quotient on Some Quality Parameters and Volatile Profile of ‘Royal Gala’ Apple after Long-Term Storage. Food Chem 2017, 215, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anese, R. de O.; Brackmann, A.; Thewes, F.R.; Schultz, E.E.; Ludwig, V.; Wendt, L.M.; Wagner, R.; Klein, B. Impact of Dynamic Controlled Atmosphere Storage and 1-Methylcyclopropene Treatment on Quality and Volatile Organic Compounds Profile of ‘Galaxy’ Apple. Food Packag Shelf Life 2020, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, D.; Mi, H.; Pristijono, P.; Ge, Y.; Lv, J.; Li, Y.; Liu, B. Tissue-Specific Recovery Capability of Aroma Biosynthesis in ‘Golden Delicious’ Apple Fruit after Low Oxygen Storage. Agronomy 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, E.E.; Thewes, F.R.; Wendt, L.M.; Brackmann, A.; Both, V.; Ludwig, V.; Thewes, F.R.; Soldateli, F.J.; Wagner, R. Extremely Low Oxygen with Different Hysteresis and Dynamic Controlled Atmosphere Storage: Impact on Overall Quality and Volatile Profile of ‘Maxi Gala’ Apple. Postharvest Biol Technol 2023, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, A.H.; Delong, J.M.; Arul, J.; Prange, R.K. The Trend toward Lower Oxygen Levels during Apple (Malus × Domestica Borkh) Storage - A Review. Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2015, 90, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Bi, J.; Fauconnier, M.L. Characteristic Volatiles and Cultivar Classification in 35 Apple Varieties: A Case Study of Two Harvest Years. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sceentree. Amyl acetate. 2024, https://www.scentree.co/en/Amyl_acetate.html (accessed accessed 17th October 2024).

- Echeverría, G.; Graell, J.; Lara, I.; López, M.L. Physicochemical Measurements in “Mondial Gala®” Apples Stored at Different Atmospheres: Influence on Consumer Acceptability. Postharvest Biol Technol 2008, 50, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matich, A.; Rowan, D. Pathway Analysis of Branched-Chain Ester Biosynthesis in Apple Using Deuterium Labeling and Enantioselective Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry. J Agric Food Chem 2007, 55, 2727–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, D.; Larkov, O.; Bar-Ya’akov, I.; Bar, E.; Zax, A.; Brandeis, E.; Ravid, U.; Lewinsohn, E. Developmental and Varietal Differences in Volatile Ester Formation and Acetyl-CoA: Alcohol Acetyl Transferase Activities in Apple (Malus Domestica Borkh.) Fruit. J Agric Food Chem 2005, 53, 7198–7203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, W.; Wang, N.; Fang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X. ABIOTIC STRESS GENE 1 Mediates Aroma Volatiles Accumulation by Activating MdLOX1a in Apple. Hortic. Res. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Maria, A.M.L.; Vergara, M.; Bravo, C.; Pereira, M.; Moggia, C. Development of Aroma Compounds and Sensory Quality of “Royal Gala” Apples during Storage. Journal of Horticultural Science and Biotechnology 2007, 82, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferenczi, A.; Sugimoto, N.; Beaudry, R.M. Emission Patterns of Esters and Their Precursors throughout Ripening and Senescence in ‘Redchief Delicious’ Apple Fruit and Implications Regarding Biosynthesis and Aroma Perception. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 2021, 146, 297–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotto, A.; Mcdaniel, M.R.; Mattheis, J.P. Characterization of Changes in “Gala” Apple Aroma during Storage Using Osme Analysis, a Gas Chromatography-Olfactometry Technique; 2000; Vol. 125;

- Young, H.; Gilbert, J.M.; Murray, S.H.; Ball, R.D. Causal Effects of Aroma Compounds on Royal Gala Apple Flavours. J Sci Food Agric 1996, 71, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattinga, C.; de Kok, P.M.T.; Bult, J.H.F. Sugar reduction in flavoured beverages: The robustness of aroma-induced sweetness enhancement. Proc. Flavour Sci. 2018, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara, I.; Echeverría, G.; Graell, J.; López, M.L. Volatile Emission after Controlled Atmosphere Storage of Mondial Gala Apples (Malus Domestica): Relationship to Some Involved Enzyme Activities. J Agric Food Chem 2007, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreissl J, Mall V, Steinhaus P, Steinhaus M. Leibniz-LSB@TUM Odorant Database, Version 1.2. Leibniz Institute for Food Systems Biology at the Technical University of Munich: Freising, Germany, 2022 (https://www.leibniz-lsb.de/en/databases/leibniz-lsbtum-odorant-database) (accessed 30 January 2025).

- Liu, E. tai; Wang, G. shuai; Li, Y. yuan; Shen, X.; Chen, X. sen; Song, F. hai; Wu, S. jing; Chen, Q.; Mao, Z. quan Replanting Affects the Tree Growth and Fruit Quality of Gala Apple. J Integr Agric 2014, 13, 1699–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 day of shelf life | |||||||||

| Months of storage | NA | CA | CA-et | CA-he | |||||

| avg | sd | avg | sd | avg | sd | avg | sd | ||

| Etylhene (µL kg−1 h−1) | 2 | 218.03b | 73.77 | 15.12a | 26.76 | 49.55a | 24.71 | 1.51a | 0.38a |

| 6 | 6.74a | 1.27 | 11.32a | 6.12 | 5.09a | 1.90a | |||

| CO2 (μg kg−1s−1) | 2 | 8.25a | 0.25 | 6.35b | 0.36 | 8.77a | 1.11 | 8.34a | 0.60a |

| 6 | 3.95a | 0.77 | 3.96a | 0.58 | 3.45a | 0.50a | |||

| 7 days of shelf life | |||||||||

| NA | CA | CA-et | CA-he | ||||||

| avg | sd | avg | sd | avg | sd | avg | Sd | ||

| Etilen (µL kg−1 h−1) | 2 | 199.97a | 59.45 | 133.80a | 48.52 | 173.94a | 71.52 | 108.96a | 66.79a |

| 6 | 85.77a | 14.44 | 95.29a | 28.28 | 119.45a | 45.40a | |||

| CO2 (μg kg−1s−1) | 2 | 10.90a | 1.31 | 11.93a | 1.99 | 10.01a | 1.16 | 11.39a | 2.23a |

| 6 | 7.79a | 0.44 | 10.31b | 1.50 | 8.01a | 1.02a | |||

| CA | CA-et | CA-he | ||||

| avg | sd | avg | sd | avg | sd | |

| ΔL*^2 | 17.84 | 24.98 | 54.90 | 87.58 | 48.37 | 73.66 |

| Δa*^2 | 27.75 | 33.53 | 39.18 | 47.27 | 25.17 | 39.11 |

| Δb*^2 | 12.78 | 6.96 | 10.95 | 9.94 | 8.15 | 7.17 |

| ΔE | 5.58 | 4.26 | 8.60 | 4.91 | 6.38 | 6.12 |

| 1 day of shelf life | 7 days of shelf life | ||||||||||||||||

| NA | CA | CA-et | CA-he | NA | CA | CA-et | CA-he | ||||||||||

| VOC | Month of storage | avg | sd | avg | sd | avg | sd | avg | sd | avg | sd | avg | sd | avg | sd | avg | sd |

| Linear esters | |||||||||||||||||

| Ethyl Acetate | 2.00 | 0.33a | 0.16 | 0.18a | 0.04 | 79.40b | 35.82 | 1.35a | 0.62 | 2.09a | 0.84 | 1.19a | 1.31 | 3.01a | 0.52 | 0.82a | 0.31 |

| 6.00 | 1.26a | 0.58 | 16.07b | 13.01 | 2.37a | 1.07 | 0.56a | 0.25 | 0.98b | 0.57 | 0.43a | 0.17 | |||||

| Butyl acetate | 2.00 | 65.55a | 24.52 | 6.28b | 1.98 | 43.82a | 18.88 | 44.20a | 12.19 | 112.12b | 25.98 | 18.96a | 16.45 | 32.41a | 30.39 | 26.52a | 12.58 |

| 6.00 | 1.25a | 1.19 | 7.42a | 8.41 | 1.64a | 1.04 | 4.71a | 2.72 | 9.42a | 7.26 | 3.09a | 2.11 | |||||

| Butyl propionate | 2.00 | 6.23b | 1.73 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 9.31b | 1.20 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 |

| 6.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | |||||

| Pentyl acetate | 2.00 | 5.60ab | 2.15 | 3.33a | 0.40 | 7.07ab | 2.43 | 9.16b | 1.69 | 8.99a | 0.81 | 4.72b | 1.81 | 5.34b | 1.56 | 5.28b | 0.48 |

| 6.00 | 0.85a | 0.46 | 2.06a | 1.47 | 5.88b | 1.36 | 2.68a | 1.17 | 4.39a | 2.22 | 1.78a | 1.09 | |||||

| Butyl butanoate | 2.00 | 19.27b | 7.22 | 1.12a | 0.50 | 4.24a | 0.94 | 3.19a | 1.14 | 18.80b | 0.93 | 7.42a | 4.31 | 7.62a | 3.28 | 6.47a | 0.99 |

| 6.00 | 0.46a | 0.45 | 2.11a | 2.28 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 4.87ab | 2.03 | 8.40a | 3.47 | 3.18b | 1.97 | |||||

| Ethyl hexanoate | 2.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.78b | 0.53 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 |

| 6.00 | 0.20a | 0.35 | 0.00b | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.18a | 0.13 | 0.06a | 0.12 | |||||

| Hexyl acetate | 2.00 | 133.69a | 46.37 | 46.61c | 12.91 | 78.37ac | 30.68 | 608.72b | 61.38 | 135.24b | 16.89 | 47.57a | 14.22 | 56.44a | 20.04 | 74.56a | 7.16 |

| 6.00 | 14.22a | 6.73 | 28.02a | 20.17 | 159.55b | 32.92 | 34.95a | 13.55 | 48.30a | 16.49 | 36.12a | 14.47 | |||||

| Propyl hexanoate | 2.00 | 0.24b | 0.10 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.16a | 0.06 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 1.27a | 0.33 | 0.94a | 0.40 | 0.81a | 0.30 | 0.74a | 0.12 |

| 6.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.77a | 0.37 | 1.30a | 0.42 | 0.49a | 0.56 | |||||

| Hexyl propanoate | 2.00 | 4.26b | 0.73 | 0.24a | 0.13 | 0.46a | 0.20 | 0.99a | 0.33 | 4.26b | 1.07 | 1.70a | 0.70 | 1.83a | 0.66 | 1.64a | 0.02 |

| 6.00 | 0.17a | 0.07 | 0.36a | 0.40 | 0.64a | 0.42 | 1.35a | 0.51 | 1.55a | 0.46 | 1.52a | 0.73 | |||||

| Butyl hexanoate | 2.00 | 26.95b | 12.67 | 2.63a | 0.97 | 6.58a | 1.39 | 1.48 | 0.78 | 30.39a | 6.04 | 22.17ab | 5.32 | 18.49b | 3.80 | 21.71ab | 2.86 |

| 6.00 | 3.83a | 2.42 | 10.21a | 8.36 | 1.04 | 0.45 | 42.92a | 6.68 | 76.26b | 9.52 | 28.53a | 11.56 | |||||

| Hexyl butanoate | 2.00 | 16.17a | 5.96 | 2.80a | 0.63 | 4.25a | 1.05 | 7.65a | 2.12 | 13.81a | 6.06 | 7.81ab | 1.70 | 6.58b | 1.58 | 7.35ab | 1.46 |

| 6.00 | 2.95a | 0.76 | 4.31a | 2.30 | 5.99a | 2.02 | 16.55ab | 4.44 | 23.15a | 3.44 | 15.26b | 4.00 | |||||

| Hexyl hexanoate | 2.00 | 12.92b | 7.04 | 3.42a | 1.32 | 3.73a | 1.38 | 2.47a | 1.54 | 12.57a | 7.73 | 15.22a | 5.46 | 10.07a | 0.36 | 16.18a | 2.95 |

| 6.00 | 25.19a | 10.09 | 43.85ab | 11.70 | 69.11b | 15.23 | 176.36a | 45.79 | 256.59a | 41.36 | 201.76a | 52.06 | |||||

| Butyl octanoate | 2.00 | 3.29b | 1.67 | 0.45a | 0.16 | 0.99a | 0.39 | 0.17a | 0.12 | 4.63a | 2.02 | 2.92a | 0.88 | 2.68a | 0.96 | 2.98a | 0.21 |

| 6.00 | 0.27a | 0.27 | 1.01a | 0.76 | 0.15a | 0.07 | 2.69a | 0.55 | 5.00b | 1.32 | 1.93a | 0.86 | |||||

| Branched esters | |||||||||||||||||

| 2-Methylpropyl acetate | 2.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 1.27b | 0.47 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00b | 0.00 | 3.04a | 1.14 | 2.99a | 0.55 | 3.76a | 0.40 |

| 6.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | |||||

| Ethyl 2-methylbutanoate | 2.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.22b | 0.17 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.14b | 0.02 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 |

| 6.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | |||||

| 2-Methylbutyl acetate | 2.00 | 24.99a | 5.57 | 34.80ac | 4.43 | 62.19b | 12.89 | 52.10bc | 10.44 | 63.91a | 14.58 | 71.94a | 10.28 | 81.33ab | 14.56 | 103.47b | 13.68 |

| 6.00 | 79.35a | 40.76 | 99.01a | 34.09 | 117.53a | 34.65 | 85.57a | 42.23 | 101.42a | 42.39 | 71.33a | 14.97 | |||||

| Butyl 2-methylbutanoate | 2.00 | 8.63a | 3.11 | 0.47a | 0.20 | 1.53b | 0.34 | 0.49b | 0.17 | 35.61a | 4.92 | 6.58a | 4.75 | 7.30a | 3.58 | 7.21a | 1.38 |

| 6.00 | 0.16a | 0.28 | 0.97a | 1.33 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 3.45a | 1.52 | 6.13a | 3.52 | 1.96a | 1.18 | |||||

| 2-Methylbutyl butanoate | 2.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 |

| 6.00 | 0.47a | 0.09 | 0.38a | 0.26 | 0.00b | 0.00 | 1.48a | 0.10 | 1.98b | 0.21 | 1.50a | 0.16 | |||||

| Amyl 2-methylbutanoate | 2.00 | 0.26b | 0.05 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 1.12b | 0.33 | 0.41a | 0.18 | 0.40a | 0.13 | 0.37a | 0.04 |

| 6.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.34a | 0.12 | 0.47a | 0.19 | 0.16a | 0.11 | |||||

| 5-Hexenyl acetate | 2.00 | 0.69a | 0.26 | 0.38a | 0.05 | 0.69a | 0.20 | 0.74a | 0.09 | 0.85a | 0.10 | 0.76a | 0.13 | 0.79a | 0.17 | 1.05a | 0.13 |

| 6.00 | 0.22a | 0.01 | 0.37a | 0.18 | 0.87b | 0.11 | 0.67a | 0.26 | 1.05a | 0.29 | 0.62a | 0.29 | |||||

| Hexyl 2-methylbutanoate | 2.00 | 16.10b | 4.08 | 3.84a | 0.89 | 3.99a | 0.87 | 3.96a | 0.46 | 33.52b | 9.31 | 12.04a | 3.36 | 10.23a | 2.96 | 13.74a | 2.07 |

| 6.00 | 4.48a | 1.02 | 4.95a | 1.89 | 12.18a | 3.60 | 20.25a | 8.73 | 24.03a | 7.35 | 16.35a | 4.82 | |||||

| Alcohols | |||||||||||||||||

| Ethanol | 2.00 | 2.67a | 1.21 | 3.52a | 0.83 | 35.14b | 16.47 | 4.93a | 2.57 | 4.14a | 3.50 | 1.68a | 0.42 | 3.35a | 1.84 | 2.52a | 0.65 |

| 6.00 | 5.21a | 1.48 | 5.42a | 1.13 | 6.38a | 0.77 | 6.61a | 1.03 | 10.13b | 1.33 | 5.99a | 0.26 | |||||

| 2-Pentanol | 2.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 8.90b | 7.88 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 12.10a | 14.07 | 0.32a | 0.04 |

| 6.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 6.82a | 12.42 | 13.80a | 2.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 8.81b | 1.33 | |||||

| 1-Butanol | 2.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 6.53a | 1.44 | 40.71b | 17.06 | 33.05a | 5.24 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 27.2b | 18.78 | 18.70b | 7.31 |

| 6.00 | 5.49a | 2.72 | 12.39a | 11.44 | 3.68a | 1.14 | 7.95a | 4.36 | 13.05a | 9.02 | 6.03a | 2.52 | |||||

| 2-Methyl-1-butanol | 2.00 | 0.91a | 0.12 | 1.87ab | 0.28 | 3.69c | 1.42 | 3.32bc | 0.39 | 2.89a | 0.28 | 2.88a | 0.88 | 3.81a | 0.81 | 3.20a | 0.34 |

| 6.00 | 6.84a | 1.90 | 6.61a | 1.78 | 12.57v | 3.51 | 4.27a | 1.71 | 5.86a | 3.11 | 5.00a | 1.24 | |||||

| 1-Hexanol | 2.00 | 11.25a | 2.08 | 6.75a | 1.61 | 12.01a | 5.51 | 52.01b | 10.98 | 8.21a | 1.30 | 4.28b | 0.97 | 5.39ab | 1.81 | 6.78ab | 1.67 |

| 6.00 | 6.04a | 1.75 | 6.11a | 1.87 | 51.08b | 4.80 | 5.69a | 1.14 | 6.89a | 1.65 | 14.02a | 1.76 | |||||

| Other VOCs | |||||||||||||||||

| 2-Pentanone | 2.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.14b | 0.04 | 1.11b | 0.40 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.38b | 0.05 |

| 6.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 12.11b | 5.09 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 2.44b | 1.14 | |||||

| Hexanal | 2.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.57b | 0.09 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 | 0.00a | 0.00 |

| 6.00 | 1.99a | 0.99 | 0.98a | 0.39 | 3.13b | 1.06 | 0.78a | 0.29 | 0.78a | 0.21 | 0.66a | 0.14 | |||||

| 6-Methyl-5-heptene-2-one | 2.00 | 0.15a | 0.06 | 0.12a | 0.02 | 0.16a | 0.05 | 0.09a | 0.08 | 0.17a | 0.06 | 0.40a | 0.19 | 0.35a | 0.05 | 0.44a | 0.10 |

| 6.00 | 1.90a | 0.47 | 2.46a | 0.69 | 1.81a | 0.35 | 1.04a | 0.45 | 1.74b | 0.16 | 2.22b | 0.31 | |||||

| Benzaldehyde | 2.00 | 0.27a | 0.10 | 0.26a | 0.03 | 0.26a | 0.08 | 0.21a | 0.15 | 0.20a | 0.06 | 0.21a | 0.06 | 0.33a | 0.28 | 0.32a | 0.31 |

| 6.00 | 0.68a | 0.07 | 0.70a | 0.11 | 0.80a | 0.09 | 0.46a | 0.04 | 1.58a | 2.06 | 0.53a | 0.10 | |||||

| Estragole | 2.00 | 2.61a | 1.22 | 4.62a | 1.52 | 5.23a | 1.76 | 2.17a | 0.42 | 7.38a | 3.90 | 9.20a | 2.90 | 8.72a | 2.38 | 7.00a | 0.92 |

| 6.00 | 11.77a | 3.30 | 9.53a | 1.89 | 10.50a | 3.78 | 7.28a | 3.97 | 7.52a | 4.17 | 3.75a | 1.40 | |||||

| α-Farnesene | 2.00 | 9.29ab | 6.16 | 13.93a | 3.37 | 11.18ab | 2.39 | 2.95b | 2.85 | 23.28a | 7.46 | 28.26a | 7.87 | 20.53a | 1.52 | 23.90a | 5.07 |

| 6.00 | 35.89a | 7.59 | 45.56a | 5.45 | 40.12a | 8.78 | 43.94a | 16.46 | 42.61a | 8.02 | 47.65a | 3.57 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).