1. Introduction

Blockchain technology has been gaining traction in the business world because of its potential to revolutionize company operations [

1]. It is a distributed ledger technology that allows for more secure, transparent, and immutable transactions [

2]. In 2008, Satoshi published his study on 'Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System,” in which an electronic cash system was proposed [

3]. This framework made it conceivable for installments to be started by one party and sent specifically to another without the intervention of an exterior monetary institution [

4]. Researchers have steadily come to grasp the worthiness of blockchain, which may be a key fundamental innovation of Bitcoin, as intrigued by computerized cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, which has developed over a long time [

5,

6]. Blockchain innovation can be a distributed database in which transactions and exchanges are naturally completed through scripted smart contracts, and the use of cryptography makes the distributed ledger record immutable [

7,

8]. The application of smart contracts is centered on the financial sector, but it also leads to radical changes in non-financial fields such as e-commerce, e-government, credit evaluation, and supply chains [

7,

9,

10]. This technology can enable companies to develop dynamic capabilities, including the ability to quickly adapt to changing market conditions. This article discusses the potential of blockchain technology to enable dynamic capabilities, as well as the challenges associated with its implementation in the financial sector, focusing on banking services.

Although many studies have been published on cryptocurrencies and blockchain technology’s effects on firms in different industries, to our knowledge, no paper has been identified that connects blockchain and cryptocurrencies with the development of dynamic capabilities.

This study aims to identify the value of blockchain in generating dynamic capabilities for banks operating in Spain. For example, blockchain technology can create a secure, immutable and transparent environment in which companies can store and share data [

11,

12]. These data can be used to quickly identify changes in the market and adapt accordingly. This data cannot be changed or manipulated, which allows companies to trust the data they use and make decisions based on accurate information.

In this sense, this paper tries to answer the following research questions:

RQ1. What is the relationship between blockchain technology’s effects and bank performance?

RQ2. What is the relationship between blockchain technology effects and dynamic capabilities?

RQ3. What is the relationship between dynamic capabilities and performance in banks?

This paper will highlight the merits and demerits of blockchain technology and its policy implications for bank executives and regulators. It will provide some insights into how blockchain technology can provide businesses with dynamic capabilities by adding value for companies to operate in. This environment will enable companies to quickly identify changes in the market and adapt accordingly.

After the introduction, the second section of this paper will analyze the potential of blockchain technology to enable dynamic capabilities in banks. It will explain how blockchain technology can create a secure, transparent, and immutable environment for companies to operate in. It will also show if there is an advantage of this technology in facilitating rapid adaptation to changing market conditions.

The third section will present the method applied for the empirical analysis, a survey for the collection of the information and Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), and the steps followed in the research.

The fourth section of this paper will focus on the results obtained from the SEM analysis, paying attention to each component of the Dynamic Capabilities such as Adoption Capability, Absorption Capability, Innovation Capability, and Detection Capability. We will demonstrate whether value is created and added to banks that use blockchain technology.

Finally, this paper concludes by summarizing the potential of blockchain technology to enable dynamic capabilities as well as the challenges associated with its implementation. Research limitations and areas of further study will be enumerated for future work and other researchers to explore blockchain technology, and its applications are still greenfield. The potential benefits of blockchain technology are enormous, and attendant risks need to be carefully examined and mitigated.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Blockchain Technology (BC/BTE)

Blockchain technology was first introduced in the world by Satoshi, a pseudonym for the first person to successfully implement blockchain technology [

13]. The history of blockchain technology can be traced back to 2008, when Satoshi Nakamoto invented blockchain technology and the digital currency, Bitcoin. Nakamoto invented this technology to create a secure and reliable distributed ledger system [

14]. Blockchain technology is currently being used in various industries and fields, of which the financial sector is the dominant one in the use of this technology.

One of the top five digital technologies predicted to significantly alter how we live, and work is blockchain [

15,

16]. Ten percent of the world's GDP will remain on blockchain by 2027 [

17]. Blockchain was a standout technology at the Davos World Economic Forum, with huge implications for people, corporations, and society [

18]. Blockchain has been claimed to allow businesses to reduce the costs of doing business and leverage external resources as easily as internal ones [

15]. [

19] Carson focused on the value that blockchain will eventually provide, transitioning from cost savings to new business opportunities and revenue sources. Blockchain is an open and incorruptible platform where users can upload self-executing programs and verify the system's history and present conditions. Blockchain technology is popular due to its traceability, transparency (visibility), security (resilience), and anonymity, which do not require the trust of the participant or a third party to regulate it [

20]. Information history is stored in a safe database that interested parties can view whenever they want [

21]. Commercial ventures can benefit from the four essential features of blockchain [

18]:

Immutability: After a transaction is validated, it cannot be changed by nefarious parties.

Traceability: The transaction history is fully and transparently audited.

Consensus: To avoid conflicts, all participants agreed to a single dataset.

Automation: Under specific circumstances, commands and transactions can be performed automatically.

This digital technology is relatively new and is viewed with some suspicion. Others claim that blockchain is nothing more than a data structure controlled and owned by various users [

22], Blockchain is a ground-breaking technology that seeks to find use cases, says others [

23]. The initial use of blockchain from 2008 to 2014 mainly revolved around cryptocurrencies [

24]. Notwithstanding these criticisms, blockchain is gaining traction, and its applications are being extended to other areas. [

25] find that the convergence of blockchain and fintech technologies is transforming digital banking services. [

26] state that blockchain brings risks and opportunities to banks. However, because of the lack of legislative and technical restrictions, blockchain can be seen as an opportunity rather than a problem. This improves customer service and banking processes. [

27] stated that the findings demonstrate the strong one-dimensionality, validity, and reliability of blockchain technology in banking services. Furthermore, it clearly shows that it provides an advantage to any bank that implements blockchain technology over those that do not. For [

28], Blockchain technology has the potential to revolutionize several banking industries, including trade finance, financial reporting, and cross-border payments, by streamlining processes, improving transparency, and reducing costs. Although regulations and technical barriers currently pose challenges, blockchain technology is poised to transform the banking and financial sectors by facilitating smart contracts and faster trade execution.

Blockchain technology developed hard as a competence may provide various opportunities to a firm, especially a bank. Some of these competitive advantages include (1) better efficiency due to fast responses for each transaction, (2) speedier transactions based on computerized record keeping on the blockchain, (3) reduced transaction time and operational cost, (4) faster payment and settlements without external interaction, (5) improve third party trust with the use of cryptography, and (6) real-time data leads to openness at both ends [

29,

30]. It is essential for institutions, especially financial institutions, to cultivate skills that foster confidence among individuals and enhance operational efficiency. [

31,

32,

33]. With its involvement in handling extensive confidential ledgers and overseeing the balances of multiple centralized authorities, the banking sector stands as the foundation of many economies. [

34,

35]. Blockchains offer a substantial breakthrough in financial markets, enhancing efficiency and operational performance in the realm of electronic payments and settlement. [

36,

37,

39,

41]. Blockchain streamlines overseas transactions for banks, making them cost-effective and efficient. [

42,

43]. The research conducted by [

44] underscores the dual nature of blockchain's impact on the banking sector, suggesting that it can lead to both positive opportunities and negative threats. Despite this, certain researchers emphasize blockchain's value as a non-physical asset for a company [

45,

46]. During the initial phases, [

27] proposed a measurement tool called the Blockchain Technology Effects Instrument (BTEI) to assess the capabilities of blockchain. There are 26 properties in this instrument, which are divided into five categories: "reduced cost," "efficiency and security," "secure transfers," " high-quality customer services," and "regulatory conformity." Since its inception, blockchain technology has continuously evolved from 1.0 to 4.0 [

21], providing the banking industry with strong motivations to adopt BTE to establish and maintain a competitive edge [

47].

2.2. Dynamic Capabilities (DC)

Dynamic Capabilities (DC) refer to the achievement of a firm to surpass its competitors through the utilization of specific resources, capabilities, features, and game plans [

32,

48]. These resources consist of different components like assets, processes, information, skills, methods, knowledge, and functions that aid in the growth of a company [

46]. Attributes such as flexibility, innovation, and technological advancements enhance the organizational competency to quickly respond to peers and turn threats into opportunities [

49]. Resources and attributes come together to create the basis of organizational capabilities. These features, like blockchain technology, allow for the gathering of internal and external resources in a way that maintains competitiveness [

50,

51], allowing organizations to counter threats through their abilities [

52]. Dynamic capabilities are the capacity to learn, unlearn, and relearn and are essential to adaptive capacity [

53]. Dynamic capabilities are more difficult to achieve than static capabilities and are based on the analysis of an organization's learning processes, which can be used to adapt to changing circumstances [

54,

55]. Most banks are traditional in their operations and, therefore, need to upgrade their operations and systems to be able to compete with new technology.

According to [

56], the potential of blockchain technology can effectively address different risks and act as a valuable asset for gaining a competitive edge in performance [

57].

It is commonly recognized in the literature that three main generic strategies - cost leadership, differentiation, and focus costs/differentiation can be used to achieve a competitive advantage [

58]. The goal of the cost leadership strategy is to be the most affordable producer of banking products or services, while the differentiation strategy focuses on developing distinct qualities in banking products or services to set them apart from peers. Finally, the focus strategy involves focusing on a specific market segment with the bank's products [

58]. [

59] point out that organizations may opt to implement two strategies simultaneously rather than depending on just one strategy. For instance, they might mix competitive prices with unique products or services to lure customers. These strategic decisions could help the banking industry improve its competitive advantage (CA). Additionally, [

60] stated that effective utilization of smart contract technology can greatly enhance competitive advantage [

49] indicated that for an organization's CA to be effective, it must possess qualities like value, rarity, and non-substitutability. Additionally, [

61] suggested that organizations should regularly enhance their CA by demonstrating adaptability in a dynamic business climate. According to various research studies, blockchain technology has distinct features and advantages that could make it a valuable strategic asset for gaining a competitive edge in the present circumstances [

32,

57]. Therefore, it is essential to explore how blockchain can be used as a competitive edge in the banking sector. [

62,

63,

64] have identified five categories of competitive advantage in the existing literature: "Price/Cost," "Quality," "Delivery Dependability," "Product Innovation," and "Time to Market."

Dynamic capabilities facilitate companies in creating, deploying, and protecting invisible assets that boost long-term business excellence. The mini foundations of dynamic capabilities are clear capabilities, processes, procedures, organizational structures, decision rules, and disciplines that support enterprise-level opportunity discovery, exploitation, and reconfiguration, which are difficult to develop and implement [

50]. The Dynamic Capability Framework (DCF) rationalizes how business performance depends on the ability to administer strategic transformation, especially in chaotic market environments [

50,

65,

66,

67]. Although DCF has become one of the most renowned conjectural lenses in management research, critics argue that it is underpinned and requires a pragmatic basis [

68]. For example, [

50] refers to dynamic capabilities (DC) as 'skills, processes, procedures, organizational structures, decision, rules, and discipline’, without indicating the practical nature of such capabilities [

69]. (“Interactive profit planning systems and market...”). Most academic discussions of DC focus on abstract concepts with hazy operations [

70], resulting in a lack of understanding of the core elements of DC and their correlations to business [

69,

71].

These three dynamic capabilities are critical for organizational success: absorptive, adaptive, and innovative. First, absorptive capability enables firms to acquire, assimilate, transform, and exploit external knowledge for value creation [

72]. This dynamic capability facilitates knowledge acquisition through scanning, assimilation through internal processes, transformation through knowledge combinations, and exploitation through new products or processes [

73]. Second, adaptive capability refers to the flexibility of resources and capabilities to align with environmental demands [

74]. This includes continuous resource morphing and supply in resource applications [

74]. Adaptive capability allows firms to modify their resource base in response to a changing environment. Finally, innovative capability refers to the ability to develop new products and markets through strategic orientation and innovative behaviors and processes [

74]. This encompasses various dimensions such as product, process, market, behavioral, and strategic innovativeness [

74]. Product and process innovativeness involves the introduction of novel goods, services, and production methods. Market innovation focuses on new marketing approaches and identifies new markets [

74]. Behavioral innovation reflects an open culture that fosters new ideas at all levels, while strategic innovation captures the creative use of resources to achieve organizational goals [

74].

Interrelatedness between these capabilities is crucial, absorptive capability can enhance innovative capability by facilitating knowledge acquisition and integration to develop new ideas [

75]. Adaptive capability allows for resource flexibility, which is necessary for implementing innovative solutions. Together, these dynamic capabilities collectively contribute to a sustainable competitive advantage by enabling firms to respond to environmental changes, create new value, and stay ahead of competitors. The dynamic capabilities hypotheses are meant to show how capabilities are created as a result of the employment of BTEs at the banks. According to [

76], BTE is a technological tool that organizations can utilize to generate abilities and establish dynamic capabilities. According to [

67], dynamic capabilities present the ability of an organization to reach new and innovative ways to generate competitive advantage'. As a result, hypotheses aimed at proving these presumptions are described.

According to [

76], measuring dynamic capabilities is difficult and depends on monitoring challenging things that depend on internal firm-specific procedures and routines as well as prevailing organizational know-how.

2.3. Development of the Conceptual Model and Hypotheses

The transformative power of blockchain technology has the potential to reshape traditional business models in numerous ways. Banks in Spain are actively participating in the establishment of collaborative blockchain ecosystems to create new and disruptive business models. To construct a robust conceptual model for this study, a comprehensive approach was adopted. This involved synthesis of information from various sources, including published research articles, real-world success stories of blockchain clients, and in-depth discussions with industry experts who have practical knowledge about the implementation of blockchain technologies. Recent research has focused on the application of blockchain technology in the banking sector and its potential benefits for business performance. Yet, there is a shortage of thorough research on the potential of blockchain technology and its impact on business productivity, leading to uncertain conclusions in existing studies. Nonetheless, it is important to highlight that blockchain technology can decrease transaction costs and tackle agency costs related to internal agents in a company. Important research conducted by [

77,

78,

79] have demonstrated a clear link between business abilities and financial metrics, such as profits and return on investment (ROI). By implementing blockchain technology, banks can achieve significant cost reductions by removing the necessity of various third-party intermediaries. Additionally, blockchain technology enhances transaction efficiency, leading to smoother trade financing channels and ultimately boosting overall income

[

46] initially proposed the concept of the Resource-Based View (RBV) to explain the essential resources companies need to have to succeed in the market. These strategic resources are required to exhibit characteristics such as being valuable, rare, difficult to replicate, and strategically indispensable [

49,

80]. Banks see blockchain technology as a powerful asset with great growth potential. It is crucial to strategically utilize intangible resources over tangible ones, as argued by [

44], to achieve and sustain a competitive advantage. [

81] highlighted the decreasing cost of data over the past few decades, emphasizing that blockchains now provide a technology platform that facilitates easy sharing and use of shared information. The attention now moves towards leveraging data effectively rather than just owning it, indicating a change in competitive edge [

82]. Banks are currently working on creating blockchain products for their use, which helps boost their innovation capabilities. By integrating blockchain technology with banking software solutions, many financial institutions have enhanced their operations and strengthened their position in the banking sector. According to [

83], it is crucial to reconsider the significance of technology in the banking industry. Banks need to effectively utilize new platforms and understand the impact of changing regulations to maintain competitiveness and meet compliance in a competitive market.

Hypothesis 1 There is a relation between blockchain technology effects (BTE) and performance in Banks

Financial institutions develop dynamic capabilities by offering excellent services, which results in customer value, leading to differentiation advantages, cost leadership, and, ultimately, growth in market share and profits [

46,

84]. DC helps banks create competitive edges that allow them to provide services that are better than their peer in terms of pricing, quality, reliability, and speed of delivery. These dynamic abilities then help improve the overall performance of a bank [

85]. Furthermore, a bank can charge higher prices by providing top-notch products, leading to higher profit margins, return on capital employed (ROCE), and return on investment (ROI). By improving time-to-market and promoting fast innovation, a bank can secure a leading portion of the market and sales volume [

64]. Furthermore, the adoption of blockchain (BTE) technology equips banks with the ability to reduce costs, accelerate transaction speed, and maintain self-service operations without third-party involvement, thus mitigating security risks. Consequently, a positive correlation between blockchain technology effects and dynamic capabilities is postulated. The potential of blockchain technology lies in its ability to enhance economic performance, customer loyalty, satisfaction, and interpersonal effectiveness. Banks that have a strong customer loyalty base experience less competition and enjoy higher customer retention rates, which in turn leads to better sales and profitability [

86].

Hypothesis 2 There is a positive relation between blockchain technology effects (BTE) and Dynamic capabilities (DC).

The relationship between dynamic capabilities and bank performance is generally positive. Dynamic capabilities encompass a firm's capacity to integrate, construct, and reconfigure internal and external competencies in response to rapidly changing environments. In the banking context, these capabilities enable banks to react quickly to market changes, regulatory changes, technological advances, and evolving customer preferences. Subsequently, these adaptations can contribute to improved performance in various dimensions, including responsiveness, innovation, customer satisfaction, and operational efficiency. Banks equipped with robust dynamic capabilities are more adept at competing and thriving within the fast-paced and increasingly intricate banking landscape [

87]. The impact of dynamic capabilities on bank performance is manifested through several fundamental functions: 1. Adaptation to Change: Dynamic capabilities enable banks to discern and influence opportunities and risks, facilitating adaptation to changes in regulatory requirements, market conditions, and technological progress [

88]. 2. Resource Reconfiguration: These capabilities enable the reconfiguration of a bank's assets and organizational framework in response to internal and external changes, ensuring optimal allocation and utilization of resources. 3. Innovation: By nurturing an innovative culture and processes, dynamic capabilities facilitate the development of new financial products and services, thereby attracting and retaining customers and meeting evolving market demands [

89].

4. Customer Satisfaction: Enhanced responsiveness to client needs and preferences, personalized services, and improved customer experience contribute to improved customer satisfaction through dynamic capabilities [

90]. 5. Operational efficiency: Dynamic capabilities contribute to operational optimization, embrace digital transformation, and automate repetitive tasks, resulting in increased efficiency and reduced costs [

91]. 6. Strategic Decision Making: Banks equipped with dynamic capabilities can make more informed strategic decisions by gaining a better understanding of market trends and leveraging insights from data analytics. 7. Competitive advantage: Strong dynamic capabilities enable banks to swiftly respond to competition and differentiate their services, thereby maintaining a competitive edge in the marketplace [

92]. Fundamentally, the concept of dynamic capabilities in banking revolves around proactive management that enables continuous realignment and adjustment to maintain and enhance performance in the volatile financial industry.

Hypothesis 3 There is a positive relationship between Dynamic capabilities and Banks’ performance.

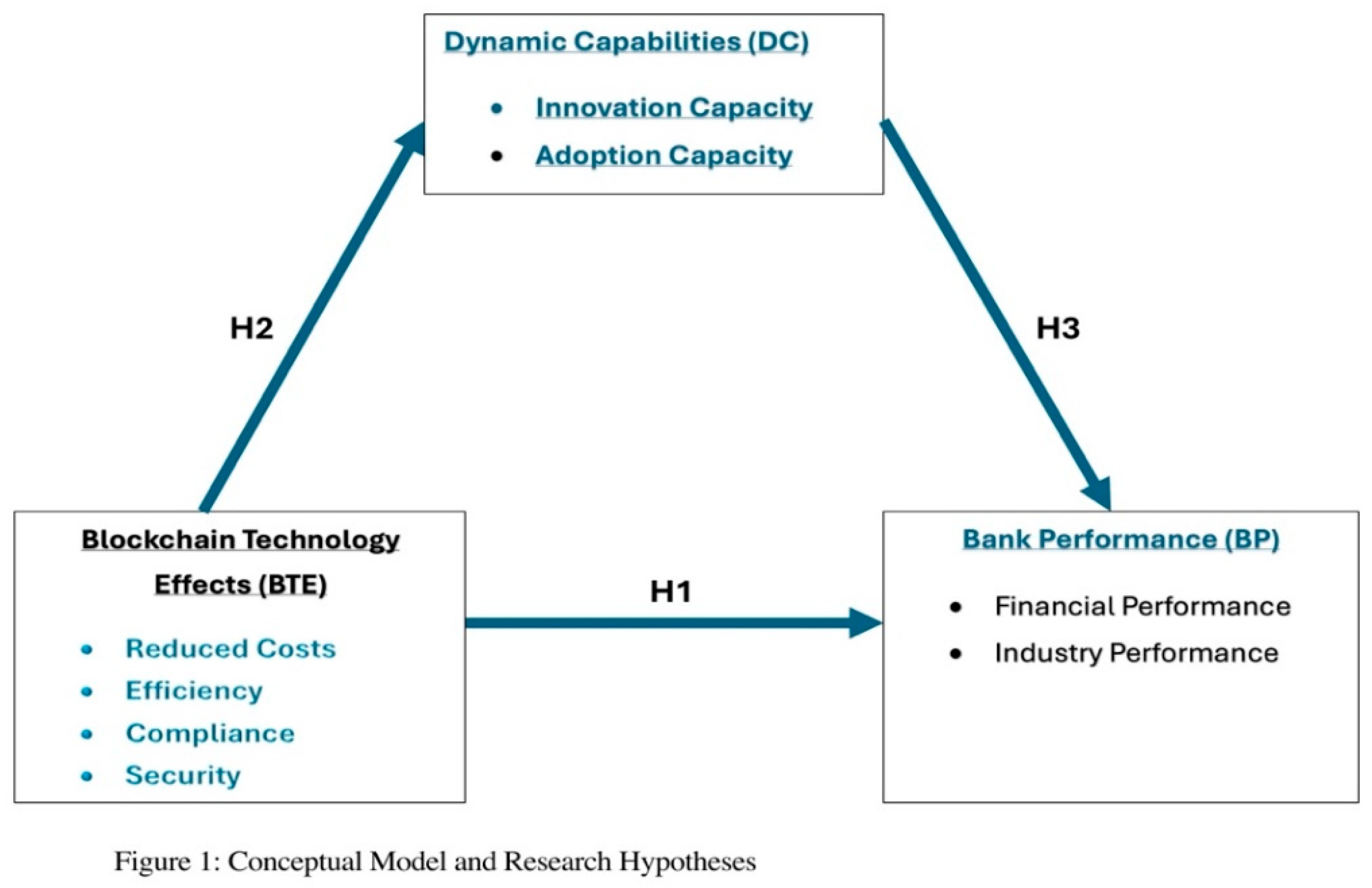

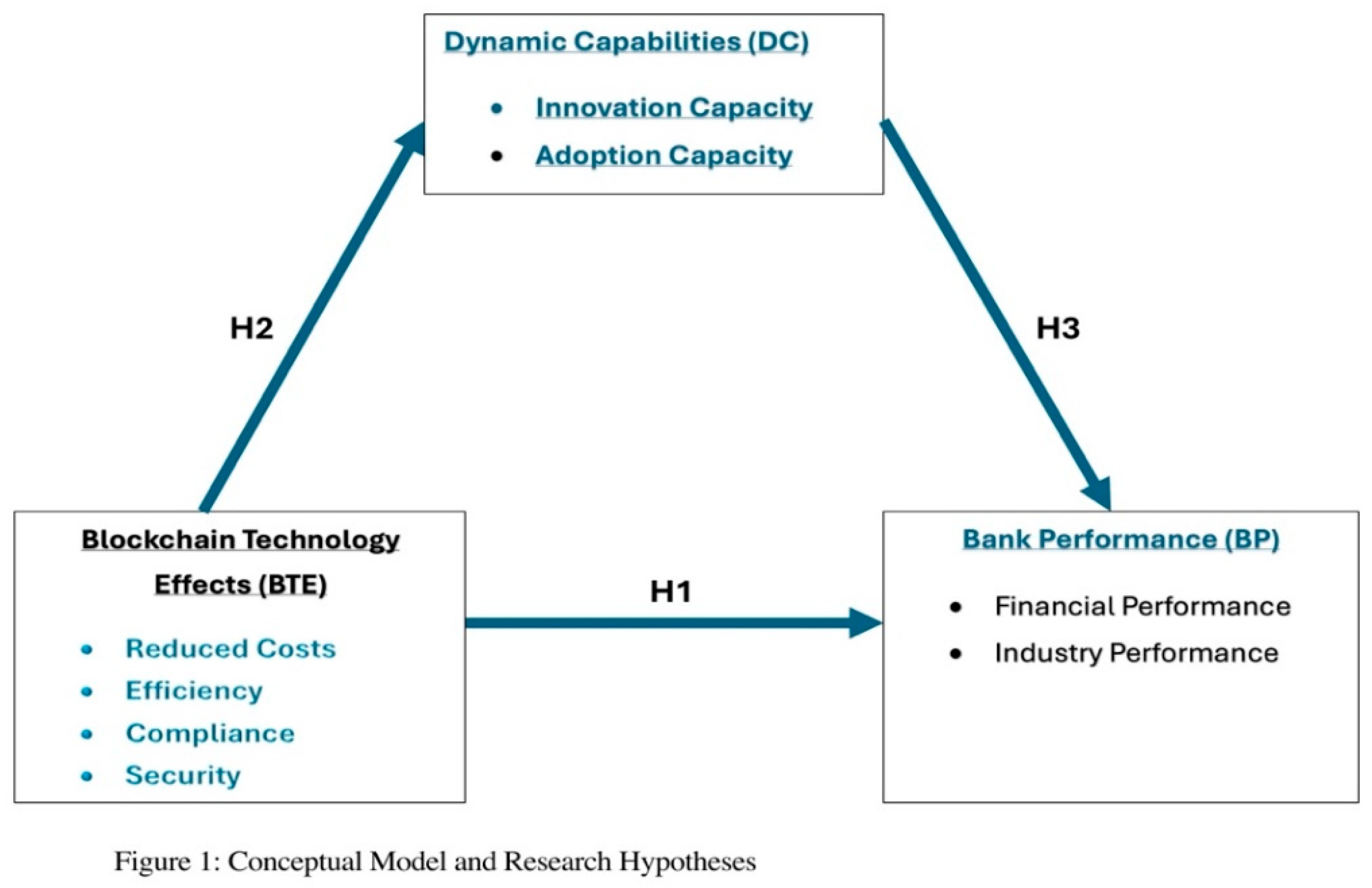

Figure 1 shows the conceptual model; it provides insight into the blockchain collaborative ecosystem. (BTE) as a significant source of dynamic capabilities (DC) that can effectively improve the operational performance of banks (BP). Figure 1 depicts the direct correlation between BTE and BP, with DC playing a mediating role in explaining their connection. An initial investigation was carried out to comprehensively grasp the size, connections, and elements of BTE, DC, and BP. Experts from the banking and IT sectors, as well as academia, were found to be engaged in creating smart chain solutions within the banking industry. A focus group was established, consisting of business specialists from banks, blockchain experts, IT professionals, and professors. By conducting a literature review and engaging in focus group conversations, the BTE, DC, and BP dimensions were specified (refer to Figure 1). BTE is made up of five aspects: reducing cost, improving efficiency, ensuring compliance, enhancing security, and providing excellent customer service [

27]. The assessment of banks' DC is based on two dimensions: product innovation and technology adoption. Meanwhile, the assessment of the banks' BP focuses on financial and industrial performance [

62,

64]. Referencing previous research, the potential connections between BTE, DC, and BP were explored, resulting in the development of hypotheses. During the following pilot study phase, confirmatory factor analysis was used to confirm and validate the dimensions and components of BTE, DC, and BP. According to [

93], it is important to recognize theoretical connections between recently suggested constructs and other conceptually related yet separate concepts. The upcoming part of the text will delve deeper into the anticipated connections between BTE, DC, and BP as backed by the literature.

3. Methods

The research aimed to explore the correlation between blockchain technology effects (BTE), dynamic capabilities (DC), and bank performance (BP). As such, the conceptual research model encompasses three key domains: BTE, DC, and BP. The assessment of BTE, DC, and BP involved the use of measurement tools derived from prior research, with some modifications. The Delphi method research is a method that has gained considerable usage, especially within the social and health sciences [

98]. It is even more effective in the case of validating questionnaires, as different studies have illustrated [

99]. The essence of the Delphi purpose is to seek adjustments from various professionals regarding the designed questionnaire’s coverage areas and specific questions concerning a particular topic [

100,

101,

102]. This technique entails a cyclical, organized, and anonymous feedback procedure where experts respond to several rounds of feedback interspersed by statistical summaries sent out between the feedback rounds [

101]. Conducting a Delphi study consists of numerous events designated as phases, even if the number and the name of such phases depict variety. Nevertheless, although there are such differences, the main sequence of actions is the same in most cases. So, for this investigation, we adopted the three levels used by other researchers earlier based on the preliminary, exploratory, and final phases of the Delphi process [11101].

Initial stage: the subsequent actions were carried out during this stage.

- Composition of the coordinating group: the coordinating group consists of the four authors involved in this research.

- Literature review: a comprehensive search for documents pertaining to the BTE was performed and interviews took place.

- Creation and assessment of the questionnaire for validation: The coordinating team developed the questionnaire, and following its review, 6 items were incorporated and assessed.

- Drafting the questionnaire for the initial round of the Delphi: in this questionnaire, the experts were solicited for their views on the clarity and suitability of the items concerning each RQ and the associated measurement scales.

- Choosing the expert panel: The choice of experts was a crucial factor for the credibility of the Delphi results. In this context, the standards for choosing the experts and the total number of experts selected relied on the topic to be discussed and the goals to be accomplished in applying the Delphi method [

97,

102,

103].

| Question |

Brief explanation for including the question |

Reference |

| Do you find it easy to use blockchain in your bank? |

This question was to figure out banks that are using blockchain technology or not |

[70] |

| If you were able to use blockchain, would this help you plan your activities better? |

This question was to figure out banks that are using blockchain technology or not |

[111] |

| How do you currently use blockchain technology? Select as many as you see possible |

This question was to determine how blockchain is being use in banks |

[27] |

| Do you find it hard to use blockchain that are appropriate for your products? |

This question was to determine how blockchain is being use in banks |

[27] |

| What information would you like to receive regarding blockchain efficiency? |

This question was to determine how blockchain efficiency |

[112] |

| How would you rate the following functions of blockchain? |

This question was to determine blockchain functionality |

[31] |

| How should the system work? Perhaps other features you would like to see? |

This question was to determine blockchain features |

[36] |

| What blockchain technology do you use most at your bank? |

This question was to determine blockchain usage |

[113] |

| Which of these blockchain technology do you use less often? |

This question was to determine blockchain usage |

[113] |

| What information should be included in a blockchain? |

This question was to determine blockchain features |

[36] |

| What are the potentials of blockchain technology? |

This question was to determine blockchain features |

[36] |

| What are the dangers of blockchain technology? |

This question was to determine blockchain security and safety |

[114] |

| How do you mitigate against these dangers of using blockchain technology? |

This question was to determine blockchain security and safety |

[114] |

| How should blockchain work? Perhaps other features you would like to see? |

This question was to determine blockchain functionality |

[31] |

| What stops your bank from using blockchain? |

This question was to determine blockchain adoptability |

[115] |

| Does BTE improves banks performance? |

This question was to determine blockchain efficiency |

[112] |

| Does BTE speed up your transactions? |

This question was to determine blockchain efficiency |

[112] |

| Does BTE provide more security for your transactions? |

This question was to determine blockchain security and safety |

[115] |

| Does BTE improves customers satisfaction? |

This question was to determine blockchain efficiency |

[112] |

| Does BTE Reduced operational costs? |

This question was to determine blockchain efficiency |

[112] |

| Does the usage of BTE comply with regulatory directives? |

This question was to determine blockchain compliance with regulations |

[116] |

| Does BTE improves your banks efficiency? |

This question was to determine blockchain efficiency |

[112] |

| Does BTE improve your bank financial performance? |

This question was to determine blockchain efficiency |

[112] |

| Does BTE increase your banks' market share? |

This question was to determine blockchain performance |

[117] |

| Does BTE increase your banks' ranking in the industry? |

This question was to determine blockchain performance |

[117] |

| Do you believe blockchain enhances your bank Absorption capacity? |

This question was to determine banks blockchain capabilities |

[118] |

| Do you believe blockchain improves your bank Adoption capacity? |

This question was to determine banks blockchain capabilities |

[118] |

| Do you believe blockchain boosts your bank detection capacity? |

This question was to determine banks blockchain capabilities |

[118] |

| Do you believe blockchain augments your bank Innovation capacity? |

This question was to determine banks blockchain capabilities |

[118] |

| Please state any other competitive advantages your bank enjoys from the use of blockchain technology? |

This question was to determine banks competitive advantage using blockchain |

[119] |

Figure 2. Research question, brief explanation, and impacted author(s)/report(s).

In the banking sector, specialists were chosen based on these standards:

- (1)

they reflect the target population for the final survey, and they are IT specialists in the banking industry with significant expertise in the deployment and implementation of blockchain technology.

- (2)

In the academic sector, specialists whose research efforts are connected in some form to dynamic capabilities, banking performance, and/or economics were chosen.

The demographic profiles of the participants are outlined in

Table 1. A survey was conducted with 170 participants, approximately 67 of whom were female and 103 were male. Regarding age distribution, 46.65% of participants fell within the 25-35 age range, 43.83% were aged between 35 and 50, and the remaining 9.52% were above 51 years old.

Both bankers and bank customers who utilized or interacted with blockchain solutions in the banking industry were included in the study's participants. At the onset, five leading banks, specifically Caixa, Santander, BBVA, Sabadell, and Interbank, respectively, were contacted via telephone and email to determine their involvement in utilizing, implementing, or planning the deployment of blockchain technology within the banking sector, ensuring the selection of appropriate individuals to maintain sample homogeneity. Subsequently, blockchain experts within the banks were approached to participate in the survey. The surveys were given to specific individuals, and their feedback was collected via mailed surveys and online questionnaires using SurveyMonkey. 300 surveys were distributed to participants in total. In the beginning, 135 people participated, resulting in a response rate of around 45%. Further communication was done to improve the number of responses, restating the study's objective, giving more information about the surveys, and assuring participants that only their data would be used while keeping their identity confidential. After these additional follow-up attempts, another 80 individuals answered, leading to a higher response rate of 71.7%. Among the 215 responses received, 28 questionnaires were discovered to have missing or incomplete answers and no engagement response. Moreover, analysis of the data showed that 12 participants had not answered certain questions. These people were later reached by phone to explain the objective of the study, resulting in 5 more replies. During the assessment of nonresponse bias, a group of nonrespondents (N = 15; roughly 17.65% of non-respondents) were contacted through follow-up calls to gather insight into why they chose not to take part in the survey. A main factor in not finishing the survey was identified as being short on time. As a result, 10 questionnaires were ineligible for analysis, resulting in 170 valid samples for the final analysis. Data gathering was carried out from June to December 2023.

A 15-item scale adapted from [

27] was used to assess the attributes of BTE, including "Reduced cost," "Efficiency," "Security," "Compliance,” and "Customer service." In the meantime, DC's dimensions ("Product Innovation" and "Technology Adoption") were evaluated with a 5-item tool, each based on [

62,

64]. The measurements of BP's financial and Industrial performance were evaluated using a 5-item scale taken from [

62,

64]. These dimensions and items were selected from previous research and have been shown to have empirical reliability and validity. Hence, additional testing on the instrument was not conducted during the pilot study. Nevertheless, it is wise to obtain confirmation from experts in the field to confirm the importance of the inquiries regarding BTE, DC, and BP in the banking industry. As a result, a CFA was performed on the 15 BTE items, 10 DC items, and 5 BP items to evaluate the suitability of the measurement model.

By studying the relationship between BTE, DC, and BP in the banking sector, scholars developed a structured questionnaire based on an analysis of pertinent studies [

27], [

62,

64]. Five professionals, consisting of three academics, a blockchain expert, and a banker, were assigned to assess the clarity of the questionnaire and the suitability of its contents. Following input from experts, minor changes were made to the question wording based on their comments and feedback, resulting in improvements to the questionnaire. Afterward, a preliminary study was carried out following revisions made to the questionnaire. The survey consisted of 30 questions divided into four sections: the initial section concentrated on the demographic information of the participants, the next focus on BTE, the third on DC, and the final section primarily on BP. Responses to statements regarding BTE, DC, and BP were assessed using a five-point Likert scale, from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

4. Results

We analyze our data using PLS-SEM as a multivariate statistical technique to analyze multiple variables and equations simultaneously. Structural equation modeling (SEM) is based on two basic models: the "measurement model" and the "structural equation model" [

94]. The measurement model evaluates the connections between latent variables and their observed indicators, while the structural model describes the relationships between latent constructs in the research objective. PLS effectively handles a complicated model and limited sample size without making any assumptions about the data beneath. All the constructs in this study consisted of multiple indicators. Hence, the advantage of using PLS is that the loading of the indicators on the construct is considered in the context of the theoretical model rather than using them separately from the sources [

90,

91]. Data analysis results can be presented in two steps. First, to ensure the reliability and validity of our theoretical framework, indicator reliability, internal consistency reliability, convergent and discriminant validity were assessed for the model constructs.

Regarding internal consistency reliability, all Cronbach's α values were > 0.6 (see

Table 3). We also achieved good indicator reliability, with all indicator loadings > 0.6 and most > 0.7. For convergent validity, all AVE (Average Variance Extracted) scores were > 0.3 with p-values of 0 (see

Table 3). All constructs have good discriminant validity, as external loadings of indicators on their constructs were all higher than their cross-loadings with other constructs. The square root of the average variance extracted for each construct exceeded its maximum correlation with any other construct in the model, supporting discriminant validity as per Fornell-Larcker (

Table 3).

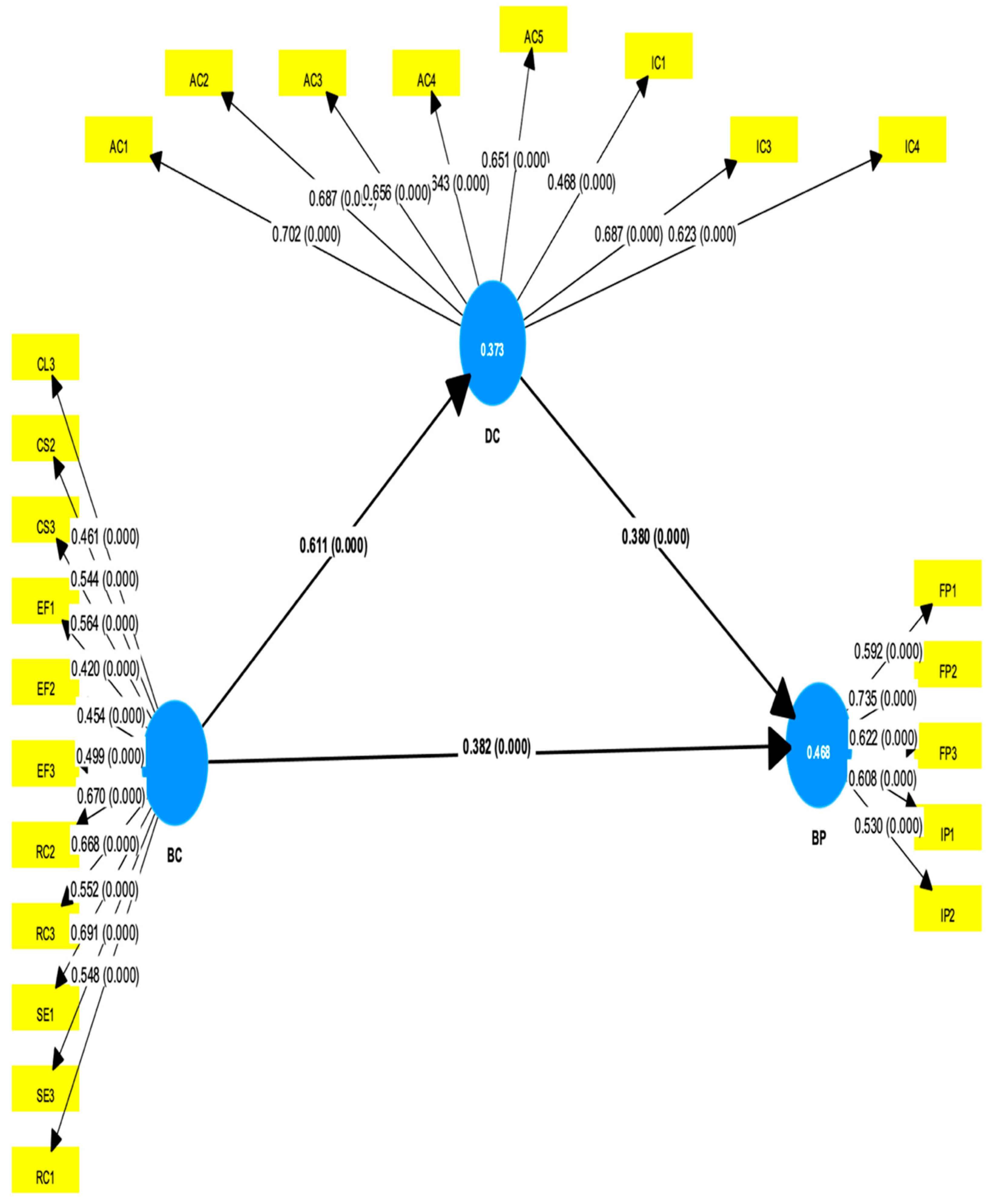

Next, to evaluate the structural model of our theoretical framework, we analyzed the construct collinearity, the coefficient of determination (R2), and the significance of the path coefficients [

91,

92]. Every R2 score was higher than 0.1, with the final dependent variable (Banks Performance) having an R2 score of 0.423. Furthermore, the model was also tested for collinearity between constructs, with all VIF values well below 5, indicating that there is no presence of multicollinearity in our model [

97]. The significance of the path coefficients was determined by employing a bootstrapping method with 5000 sub-samples for a two-tailed test. Figure 2 shows both the values and the significance of the path coefficient.

Figure 3.

Theoretical Framework and Results.

Figure 3.

Theoretical Framework and Results.

The theoretical framework was developed to show the relationship between the latent and dependent variables.

Table 2.

Quality Criteria.

Table 2.

Quality Criteria.

| R-square |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Original sample (o) |

Sample mean (M) |

Standard deviation (STDEV) |

T-statistics ([O/STDEV]) |

P values |

| BP |

0,468 |

0,484 |

0,056 |

8,299 |

0,000 |

| DC |

0,373 |

0,387 |

0,057 |

6,494 |

0,000 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| R-square adjusted |

|

|

|

|

| |

Original sample (o) |

Sample mean (M) |

Standard deviation (STDEV) |

T-statistics ([O/STDEV]) |

P values |

| BP |

0,461 |

0,477 |

0,057 |

8,089 |

0,000 |

| DC |

0,369 |

0,384 |

0,058 |

6,391 |

0,000 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| f-square |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Original sample (o) |

Sample mean (M) |

Standard deviation (STDEV) |

T-statistics ([O/STDEV]) |

P values |

| BTE-> BP |

0,172 |

0,188 |

0,077 |

2,232 |

0,026 |

| BTE-> DC |

0,595 |

0,647 |

0,157 |

3,783 |

0,000 |

| DC-> BP |

0,17 |

0,182 |

0,08 |

2,14 |

0,032 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| average variance extracted (AVE) |

|

|

|

| |

Original sample (o) |

Sample mean (M) |

Standard deviation (STDEV) |

T-statistics ([O/STDEV]) |

P values |

| BTE |

0,312 |

0,314 |

0,026 |

11,855 |

0,000 |

| BP |

0,385 |

0,387 |

0,029 |

13,464 |

0,000 |

| DC |

0,414 |

0,416 |

0,027 |

15,432 |

0,000 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| composite reliability (rho_c) |

|

|

|

| |

Original sample (o) |

Sample mean (M) |

Standard deviation (STDEV) |

T-statistics ([O/STDEV]) |

P values |

| BTE |

0,83 |

0,828 |

0,018 |

45,121 |

0,000 |

| BP |

0,756 |

0,754 |

0,024 |

31,791 |

0,000 |

| DC |

0,848 |

0,848 |

0,015 |

58,062 |

0,000 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| composite reliability (rho_a) |

|

|

|

| |

Original sample (o) |

Sample mean (M) |

Standard deviation (STDEV) |

T-statistics ([O/STDEV]) |

P values |

| BTE |

0,787 |

0,787 |

0,028 |

28,566 |

0,000 |

| BP |

0,617 |

0,618 |

0,05 |

12,314 |

0,000 |

| DC |

0,803 |

0,805 |

0,022 |

36,464 |

0,000 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Cronbach's alpha |

|

|

|

|

| |

Original sample (o) |

Sample mean (M) |

Standard deviation (STDEV) |

T-statistics ([O/STDEV]) |

P values |

| BTE |

0,775 |

0,773 |

0,028 |

27,725 |

0,000 |

| BP |

0,607 |

0,604 |

0,047 |

13,011 |

0,000 |

| DC |

0,795 |

0,974 |

0,023 |

34,447 |

0,000 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) |

|

|

|

| Confidence intervals |

|

|

|

|

| |

Original sample (o) |

Sample mean (M) |

25% |

97.5% |

|

| BP <-> BTE |

0,868 |

0,87 |

0,725 |

1,012 |

|

| DC <-> BTE |

0,761 |

0,763 |

0,654 |

0,863 |

|

| DC <-> BP |

0,819 |

0,825 |

0,686 |

0,96 |

|

Table 3.

Fornell Larker Criterion.

Table 3.

Fornell Larker Criterion.

| Fornell-Lacker Criterion |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

BTE |

BP |

DC |

| BC |

0,559 |

|

|

| BP |

0,614 |

0,621 |

|

| DC |

0,611 |

0,613 |

0,643 |

| |

|

|

|

Indirect Effects

The indirect effects are measured and shown in Table 5

Table 4.

Indirect Effects.

Table 4.

Indirect Effects.

| Total Indirect effects |

|

|

|

|

| |

Original sample (o) |

Sample mean (M) |

Standard deviation (STDEV) |

T-statistics ([O/STDEV]) |

P values |

| BTE ->BP |

0,232 |

0,235 |

0,05 |

4,614 |

0,000 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Specific Indirect effects |

|

|

|

|

| |

Original sample (o) |

Sample mean (M) |

Standard deviation (STDEV) |

T-statistics ([O/STDEV]) |

P values |

| BTE->DC->BP |

0,232 |

0,235 |

0,05 |

4,614 |

0,000 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Total effects |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Original sample (o) |

Sample mean (M) |

Standard deviation (STDEV) |

T-statistics ([O/STDEV]) |

P values |

| BTE-> BP |

0,614 |

0,624 |

0,049 |

12,512 |

0,000 |

| BTE-> DC |

0,611 |

0,621 |

0,047 |

13,055 |

0,000 |

| DC-> BP |

0,380 |

0,379 |

0,077 |

4,926 |

0,000 |

Validating Higher Order Construct

The higher-order constructs are also validated as part of the measurement model assessment. Each of these constructs was assessed for reliability and convergent validity. The results for reliability and validity show that both reliability and validity were established.

5. Discussions and Implications

Blockchain technology pose both opportunities and challenges for the banking industry, where early adoption can lead to competitive advantages, and slow integration may result in missed opportunities. This research has explored the relationship between Blockchain technology effects (BTE), dynamic capabilities (DC), and business performance (BP) in the banking sector. The main conclusion of this study is that dynamic capabilities play a central role in strengthening the link between blockchain adoption and enhanced business performance. While the study supports some hypotheses, it also reveals areas where the evidence is less conclusive. Below, we provide insights into both validated and unvalidated hypotheses, drawing on relevant literature and acknowledging potential limitations of the study.

Our study explored the intricate relationship between blockchain technology effects (BTE), dynamic capabilities (DC), and business performance (BP) in the banking sector. The findings suggest that dynamic capabilities act as a vital mediator, enhancing the impact of blockchain adoption on business performance. This highlights the pivotal role of dynamic capabilities in fully leveraging blockchain's potential. While some hypotheses were strongly supported, others yielded inconclusive results, indicating areas for further exploration.

Our results align with previous studies that have highlighted the potential of blockchain to revolutionize banking operations [

42]. These findings are consistent with prior research, highlighting that blockchain technology creates operational efficiencies and promotes transparency in financial operations [

99]. Specifically, our findings support the notion that blockchain adoption fosters dynamic capabilities, such as adaptability, innovation, and market responsiveness, which is in line with research by [

110], who emphasized the importance of these capabilities in the digital transformation of financial services. However, our study extends this understanding by demonstrating how these capabilities mediate the relationship between blockchain adoption and banks’ performance, offering a nuanced view compared to the direct impact often suggested by earlier research [

42].

Theoretically, our study contributes to the dynamic capabilities view by showing that in blockchain technology, these capabilities are not just outcomes but mediators that enhance the relationship between technology adoption and banks’ outcomes. This finding challenges the linear technology adoption model, leading directly to performance improvements, suggesting a more complex interplay where capabilities like adaptability and innovation play a critical role.

Practically, banks can leverage these insights to strategize their blockchain adoption. The development of dynamic capabilities should be prioritized alongside technology integration to ensure that the full benefits of blockchain are realized. For instance, as evidenced by our findings, banks can achieve operational efficiencies, cost reductions, and competitive advantage by enhancing their ability to adapt to regulatory changes or innovate in service delivery.

Despite the insights gained, our study has limitations. The sample size was relatively small, which might limit the generalizability of our findings. Additionally, the study did not account for the maturity level of blockchain implementations across different banks, which could significantly influence the observed relationships. The variability in regulatory environments and market conditions across different countries or regions was also not fully explored, which might affect how dynamic capabilities and blockchain impact banks’ performance.

Future research should aim to overcome these limitations by: Expanding Sample Size: A larger, more diverse sample could provide a broader perspective on how blockchain technology influences business performance across different banking contexts. Assessing Maturity of Blockchain Implementations: Investigating how the stage of blockchain maturity affects the development of dynamic capabilities and business performance could offer deeper insights. Providing a contextual analysis: Delving into how different regulatory and market environments influence the relationship between blockchain, dynamic capabilities, and performance would be valuable. Promotion of longitudinal studies: Conducting longitudinal research could help in understanding the long-term implications of blockchain adoption and the evolution of dynamic capabilities over time. These directions would not only validate our findings but also provide a more comprehensive understanding of blockchain's role in the banking sector, potentially guiding policy and practice

6. Conclusion

The results show that the adoption of blockchain technology positively affects banks' dynamic capabilities by increasing flexibility, innovation capacity, and responsiveness to market changes. In the context of dynamic capabilities, blockchain enables better handling of rapid technological and regulatory changes. Moreover, we found evidence that enhanced dynamic capabilities lead to improved business performance, confirming the central hypothesis of this study. Banks that integrate blockchain technologies in areas such as Know Your Customer (KYC), Trade Financing, and cross-border payments stand to improve operational efficiency, reduce costs, and gain competitive advantages, aligning with studies by [

100] on blockchain's role in supply chain finance.

However, not all hypotheses were confirmed. In particular, the direct link between blockchain adoption and immediate business performance was not as strong as anticipated. Several factors may account for this:

Sample limitations: The study sample focused on banks, many of which may still be in the early stages of blockchain adoption. Banks with limited blockchain experience may not yet be fully capitalizing on its potential, leading to less dramatic performance improvements.

The novelty of the technology: Blockchain is still an emerging technology, and its widespread application across all banking operations remains limited.

Many banks may still be in the pilot phase of blockchain projects, which limits observable performance improvements. The full benefits of blockchain adoption may only become apparent after further maturity and integration.

Data processing tools: The tools used for data collection and analysis might not fully capture the complexity of the connections between Blockchain technology effects and performance. Future studies could benefit from more advanced data analytics tools to assess blockchain's impact more comprehensively.

The results of this research illuminate the favorable connections among BTE, DC, and BP. The findings are crucial for banks facing challenges in adopting blockchain technology, lacking a complete understanding of the advantages of accelerating and simplifying international payments, trade financing, and improving online identity verification, loyalty programs, and rewards. The findings of this study are advantageous for banks that have already utilized or trialed blockchain technology and are seeking methods to enhance their business models by embracing smart technologies for long-lasting benefits, improved efficiencies, reduced costs, and sustained capabilities. Managers should take note of two implications of our study. First, it suggests implementing blockchain projects for banks to create an improved business strategy with increased security, transparency, cost savings, and a sustained competitive edge. Additionally, to manage blockchain-related projects effectively, managers need to understand the importance of blockchain, its business ramifications, its key areas of importance, and the transformative advantages it offers. Furthermore, managers need to clarify their needs, embrace ongoing education, and enhance their expertise.

There have been only a few studies attempting to demonstrate the relationship among BTE, DC, and BP in the banking sector. This research provides concrete proof of the direct link between BTE and BP with mediation from DC. This research has certain restrictions and potential for future investigation. This research presents real-world data from a group of participants representing banks, bank clients, fintech, and IT firms in Spain. This could influence the outcomes and may not serve as a foundation for extrapolation, potentially restricting extrapolation across different sectors and nations.

Blockchain technology is still in the early phases of growth and acceptance in Spain. As a result, new avenues and topics for research can be explored to investigate the potential of blockchain in the banking industry. However, these restrictions have opened the door to further studies in this field. This study's findings can be applied to other countries to broaden its scope.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.O.; methodology, J.L.M.B.; software, J.L.M.B.; validation, A.O, J.L.M.B., L.F-S and C.D.-P.-H.; data curation, A.O.; writing—original draft preparation, A.O.; writing—review and editing, C.D.-P.-H.; supervision, C.D.-P.-H., L.F-S. and J.L.M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (Ref: PREDOC22-001).

Data Availability Statement

Links and information about the data source can be found in the materials and methods section of the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| BTE |

Blockchain Technology Effects |

| BP |

Banks’ Performance |

| BP |

Dynamic Capabilities |

References

- J. Y. Lee, “A decentralized token economy: How blockchain and cryptocurrency can revolutionize business,” Business Horizons, vol. 62, no. 6, pp. 773–784, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Leal, F. Pisani, and M. Endler, “A Multilayer Distributed Ledger Technology Architecture for Immutable Registry of Mobility and Location Information,” 2022 IEEE 1st Global Emerging Technology Blockchain Forum: Blockchain & Beyond (iGETblockchain), vol. abs 1707 82, pp. 1–6, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Berentsen, “Aleksander Berentsen Recommends ‘Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System’ by Satoshi Nakamoto,” 21st Century Economics, pp. 7–8, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Ghossein and A. N. Rana, “Business Environment Reforms in Fragile and Conflict-Affected Situations,” Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Ghosh, S. Gupta, A. Dua, and N. Kumar, “Security of Cryptocurrencies in blockchain technology: State-of-art, challenges and future prospects,” Journal of Network and Computer Applications, vol. 163, p. 102635, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. O. Nawari and S. Ravindran, “Blockchain Technologies in BIM Workflow Environment,” Computing in Civil Engineering 2019, vol. 2016, pp. 343–352, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Juma, “Cross-Border Trade Through Blockchain,” Proceedings of the II International Triple Helix Summit, pp. 165–179, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Kshetri, “Blockchain Technology for Improving Transparency and Citizen’s Trust,” Advances in Information and Communication, pp. 716–735, 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. W. E. Allen, C. Berg, S. Davidson, M. Novak, and J. Potts, “International policy coordination for blockchain supply chains,” Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 367–380, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Hald and A. Kinra, “How the blockchain enables and constrains supply chain performance,” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, vol. 49, no. 4, pp. 376–397, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Centobelli, R. Cerchione, P. D. Vecchio, E. Oropallo, and G. Secundo, “Blockchain technology for bridging trust, traceability, and transparency in the circular supply chain,” Information & Management, vol. 59, no. 7, p. 103508, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. K. -, S. H. -, U. K. -, and S. S. -, “Blockchain in Supply Chain Management: Enhancing Transparency, Efficiency, and Trust,” Advanced International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research, vol. 2, no. 5, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Taskinsoy, “The Great Silent Crash of the 21st Century,” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2022. [CrossRef]

- B. Sakız and E. A. H. Gencer, “Cryptocurrencies, Blockchain Technology, and Sustainability,” International Conference on Eurasian Economies 2020, pp. 200–206, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. M. Brennan, N. Subramaniam, and C. J. van Staden, “Corporate governance implications of disruptive technology: An overview,” The British Accounting Review, vol. 51, no. 6, p. 100860, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Tapscott and A. Tapscott, “How Blockchain Will Change Organizations,” What the Digital Future Holds, pp. 43–56, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- N. Kshetri, “Will blockchain emerge as a tool to break the poverty chain in the Global South?” Third World Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 8, pp. 1710–1732, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Carter, C., & Koh, L., "Blockchain disruption in transport: are you decentralized yet? " 2018.

- B. Carson, G. Romanelli, P. Walsh, and A. Zhumaev, "Blockchain beyond the hype: What is the strategic business value," McKinsey & Company, vol. 1, pp. 1-13, 2018.

- S. Saberi, M. Kouhizadeh, J. Sarkis, and L. Shen, “Blockchain technology and its relationships to sustainable supply chain management,” International Journal of Production Research, vol. 57, no. 7, pp. 2117–2135, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Swan, “Anticipating the Economic Benefits of Blockchain,” Technology Innovation Management Review, vol. 7, no. 10, pp. 6–13, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- E. Karafiloski and A. Mishev, “Blockchain solutions for big data challenges: A literature review,” IEEE EUROCON 2017 -17th International Conference on Smart Technologies, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Glaser and L. Bezzenberger, "Beyond Cryptocurrencies-a Taxonomy of Decentralized Consensus Systems," in 23rd European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS), Münster, Germany, March 2015.

- S. Miau and J.-M. Yang, “Bibliometrics-based evaluation of the Blockchain research trend: 2008 – March 2017,” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, vol. 30, no. 9, pp. 1029–1045, Jan. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Kumari and N. C. Devi, “The Impact of FinTech and Blockchain Technologies on Banking and Financial Services,” Technology Innovation Management Review, vol. 12, no. 1/2, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Chowdhury, A. Stasi, and A. Pellegrino, "Blockchain technology in financial accounting: emerging regulatory issues," Review of Financial Economics, vol. 21, pp. 862-868, 2023.

- P. Garg, B. Gupta, A. K. Chauhan, U. Sivarajah, S. Gupta, and S. Modgil, “Measuring the perceived benefits of implementing blockchain technology in the banking sector,” Technological Forecasting and Social Change, vol. 163, p. 120407, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Javaid, A. Haleem, R. P. Singh, R. Suman, and S. Khan, “A review of Blockchain Technology applications for financial services,” Bench Council Transactions on Benchmarks, Standards and Evaluations, vol. 2, no. 3, p. 100073, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Gupta and S. Gupta, “Blockchain Technology Application in Indian Banking Sector,” Delhi Business Review, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 75–84, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Underwood, “Blockchain beyond Bitcoin,” Communications of the ACM, vol. 59, no. 11, pp. 15–17, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- F. Casino, T. K. Dasaklis, and C. Patsakis, “A systematic literature review of blockchain-based applications: Current status, classification and open issues,” Telematics and Informatics, vol. 36, pp. 55–81, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Kant, “Blockchain: a strategic resource to attain and sustain competitive advantage,” International Journal of Innovation Science, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 520–538, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Pilkington, “Blockchain technology: principles and applications,” Research Handbook on Digital Transformations, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. Libert, M. Beck, and J. Wind, "How blockchain technology will disrupt financial services firms," Knowledge@Wharton, 2016. Available online: http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/blockchain-technology-will-disrupt-fnancial-services/firms.

- W. Mu, Y. Bian, and J. L. Zhao, “The role of online leadership in open collaborative innovation: Evidence from blockchain open-source projects,” Industrial Management & Data Systems, 2019.

- T. Beck, T. Chen, C. Lin, and F. M. Song, "Financial innovation: The bright and the dark sides," Journal of Banking & Finance, vol. 72, pp. 28-51, 2016.

- S. M. English and E. Nezhadian, “Conditions of Full Disclosure: The Blockchain Remuneration Model,” 2017 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (Eurocamp), pp. 64–67, Apr. 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Gao, L. Zhu, M. Shen, K. Sharif, Z. Wan, and K. Ren, "A blockchain-based privacy-preserving payment mechanism for vehicle-to-grid networks," IEEE Network, vol. 32, no. 6, pp. 184-192, 2018.

- T. Lundqvist, A. De Blanche, and H. R. H. Andersson, “Thing-to-thing electricity micropayments using blockchain technology,” in 2017 Global Internet of Things Summit (GIoTS), pp. 1-6, 2017.

- G. Papadopoulos, "Blockchain and digital payments: an institutionalist analysis of Cryptocurrencies," in Handbook of Digital Currency, Academic Press, pp. 153-172, 2015.

- Y. Yamada, T. Nakajima, and M. Sakamoto, "Blockchain-LI: a study on implementing activity-based micro-pricing using cryptocurrency technologies," in Proc. 14th Int. Conf. Advances in Mobile Computing and Multi-Media, pp. 203–207, 2016.

- Y. Guo and C. Liang, "Blockchain application and outlook in the banking industry," Financial Innovation, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 1-12, 2016.

- M. Isaksen, Blockchain: The Future of Cross Border Payments, master’s thesis, University of Stavanger, Norway, 2018.

- H. Hassani, X. Huang, and E. Silva, "Banking with blockchain-ed big data," Journal of Management Analytics, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 256-275, 2018.

- M. A. Hitt, L. Bierman, K. Shimizu, and R. Kochhar, “Direct and Moderating Effects of Human Capital on Strategy and Performance in Professional Service Firms: A Resource-Based Perspective,” Academy of Management Journal, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 13–28, Feb. 2001. [CrossRef]

- J. Barney, "Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage," Journal of Management Science, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 99-120, 1991.

- A. Grech and A. F. Camilleri, “Blockchain in Education,” Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2017.

- C. L. Wang, C. Senaratne, and M. Rafiq, “Success Traps, Dynamic Capabilities and Firm Performance,” British Journal of Management, vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 26–44, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. B. Barney and A. M. Arikan, "The resource-based view: origins and implications," The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management, 2001. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Teece, "Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and micro-foundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance," Strategic Management Journal, vol. 28, no. 13, pp. 1319–1350, 2007.

- J. Weerawardena and F. T. Mavondo, “Capabilities, innovation and competitive advantage,” Industrial Marketing Management, vol. 40, no. 8, pp. 1220–1223, Nov. 2011. [CrossRef]

- D. Teece and G. Pisano, “The Dynamic Capabilities of Firms: an Introduction,” Industrial and Corporate Change, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 537–556, 1994. [CrossRef]

- T. Gundu, "Learn, Unlearn and Relearn: Adaptive Cybersecurity Culture Model," International Conference on Cyber Warfare and Security, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 95-102, 2024.

- C. Baden-Fuller and D. Teece, "Market sensing, dynamic capability, and competitive dynamics," Industrial Marketing Management, vol. 89, pp. 105-106, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Petit and D. J. Teece, “Innovating Big Tech firms and competition policy: favoring dynamic over static competition,” Industrial and Corporate Change, vol. 30, no. 5, pp. 1168–1198, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Pasquale, “The Black Box Society,” Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- N. Kant and N. Agrawal, “Developing a measure of climate strategy proactivity displayed to attain competitive advantage,” Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal, vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 832–862, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Porter, “Industry Structure and Competitive Strategy: Keys to Profitability,” Financial Analysts Journal, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 30–41, Jul. 1980. [CrossRef]

- T. Cater and D. Pucko, "How competitive advantage influences firm performance: the case of Slovenian firms," Economic and Business Review, vol. 7, (2), pp. 119-135, 2005.

- Z. Arifin and Frmanzah, “The Effect of Dynamic Capability to Technology Adoption and its Determinant Factors for Improving Firm’s Performance; Toward a Conceptual Model,” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, vol. 207, pp. 786–796, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Ionescu and N. R. Dumitru, "The role of innovation in creating the company’s competitive advantage," Ecoforum Journal, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 99-104, 2015.

- X. A. Koufteros, *Time-Based Competition: Developing a Nomological Network of Constructs and Instrument Development*, Unpublished Dissertation, 1995.

- J. Zhang, “The nature of external representations in problem-solving,” Cognitive Science, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 179–217, Jun. 1997. [CrossRef]

- S. Li, B. Ragu-Nathan, T. S. Ragu-Nathan, and S. Subba Rao, “The impact of supply chain management practices on competitive advantage and organizational performance,” Omega, vol. 34, no. 2, pp. 107–124, Apr. 2006. [CrossRef]

- K. M. Eisenhardt and J. A. Martin, “Dynamic capabilities: what are they?” Strategic Management Journal, vol. 21, no. 10–11, pp. 1105–1121, 2000.

- C. E. Helfat and S. G. Winter, “Untangling Dynamic and Operational Capabilities: Strategy for the (N)ever-Changing World,” Strategic Management Journal, vol. 32, no. 11, pp. 1243–1250, Aug. 2011. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Teece, G. Pisano, and A. Shuen, “Dynamic Capabilities and Strategic Management,” Resources, Firms, And Strategies, pp. 268–285, Dec. 1997. [CrossRef]

- B. Blagoev, T. Hernes, S. Kunisch, and M. Schultz, “Time as a Research Lens: A Conceptual Review and Research Agenda,” Journal of Management, vol. 50, no. 6, pp. 2152–2196, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Wollersheim and K. H. Heimeriks, “Dynamic Capabilities and Their Characteristic Qualities: Insights from a Lab Experiment,” Organization Science, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 233–248, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. Dashkevich, S. Counsell, and G. Destefanis, “Blockchain Application for Central Banks: A Systematic Mapping Study,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 139918–139952, 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Helfat and M. A. Peteraf, "Understanding dynamic capabilities: progress along a developmental path," Strategic Organization, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 91-102, 2009. [CrossRef]

- S. A. Zahra and G. George, “Absorptive Capacity: A Review, Reconceptualization, and Extension,” Academy of Management Review, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 185–203, Apr. 2002. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Cohen and T. Caner, “Converting inventions into breakthrough innovations: The role of exploitation and alliance network knowledge heterogeneity,” Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, vol. 40, pp. 29–44, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- C. L. Wang and P. K. Ahmed, “Dynamic capabilities: A review and research agenda,” International Journal of Management Reviews, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 31–51, Feb. 2007. [CrossRef]

- U. Lichtenthaler and E. Lichtenthaler, “A Capability-Based Framework for Open Innovation: Complementing Absorptive Capacity,” Journal of Management Studies, vol. 46, no. 8, pp. 1315–1338, Oct. 2009. [CrossRef]

- C. Gallego-Gomez and C. De-Pablos-Heredero, “Artificial Intelligence as an Enabling Tool for the Development of Dynamic Capabilities in the Banking Industry,” International Journal of Enterprise Information Systems, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 20–33, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Fahy, “The resource-based view of the firm: some stumbling-blocks on the road to understanding sustainable competitive advantage,” Journal of European Industrial Training, vol. 24, no. 2/3/4, pp. 94–104, Mar. 2000. [CrossRef]

- M. T. Tsai and C. M. Shih, The impact of marketing knowledge among managers on marketing capabilities and business performance, International Journal of Management, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 524-530, 2004.

- N. A. Morgan, D. W. Vorhies, and C. H. Mason, “Market orientation, marketing capabilities, and firm performance,” Strategic Management Journal, vol. 30, no. 8, pp. 909–920, Mar. 2009. [CrossRef]

- J. Guimaraes, E. Severo, and C. Vasconcelos, “Sustainable Competitive Advantage: A Survey of Companies in Southern Brazil,” Brazilian Business Review, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 352–367, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Harrington, “Distributed autonomous learning framework,” Disruptive Technologies in Information Sciences II, p. 21, Jul. 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. McCauley unblocked: How Blockchains Will Change Your Business (and What to Do About It). Sebastopol, CA: O'Reilly Media, Inc., 2019.

- A. Basul, "The future of competitive advantage in banking and payments," bobsguide.com, 2021. Available online: https://www.bobsguide.com/articles/the-future-of-competitive-advantage-in banking-and-payments/.

- C. K. Prahalad and G. Hamel, “The Core Competence of the Corporation,” Strategische Unternehmungsplanung — Strategische Unternehmungsführung, pp. 275–292. [CrossRef]

- T. L. Esper, C. Clifford Defee, and J. T. Mentzer, “A framework of supply chain orientation,” The International Journal of Logistics Management, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 161–179, Aug. 2010. [CrossRef]

- W. T. Moran, "Research on discrete consumption markets can guide resource shifts, help increase profitability," Marketing News, vol. 14, no. 23, p. 4, 1981.

- F. Seyedjafarrangraz, C. De Fuentes, and M. Zhang, “Mapping the global regulatory terrain in digital banking: a longitudinal study across countries,” Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. Palmieri and E. F. Geretto, Adapting to Change. Palgrave Macmillan Studies in Banking and Financial Institutions, 2023.

- J. Ferreira, A. Coelho, and L. Moutinho, “Dynamic capabilities, creativity, and innovation capability and their impact on competitive advantage and firm performance: The moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation,” Technovation, vol. 92–93, p. 102061, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. H. Trani and D. A. Tran, “CUSTOMER EXPERIENCE AND SATISFACTION WITH DIGITAL BANKING SERVICES,” Proceeding of International Conference on Business, Economics, Social Sciences, and Humanities, vol. 7, pp. 548–555, Jun. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Heubeck, “Managerial capabilities as facilitators of digital transformation? Dynamic managerial capabilities as antecedents to digital business model transformation and firm performance,” Digital Business, vol. 3, no. 1, p. 100053, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Probojakti, H. N. Utami, A. Prasetya, and M. F. Riza, “Building Sustainable Competitive Advantage in Banking through Organizational Agility,” Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 19, p. 8327, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. A. Churchill, “A Paradigm for Developing Better Measures of Marketing Constructs,” Journal of Marketing Research, vol. 16, no. 1, pp. 64–73, Feb. 1979. [CrossRef]

- P. Garg, B. Gupta, K. N. Kapil, U. Sivarajah, and S. Gupta, “Examining the relationship between Blockchain technology effects and organizational performance in the Indian banking sector,” Annals of Operations Research, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. W. Marsh, K.-T. Hau, J. R. Balla, and D. Grayson, “Is More Ever Too Much? The Number of Indicators per Factor in Confirmatory Factor Analysis,” Multivariate Behavioral Research, vol. 33, no. 2, pp. 181–220, Apr. 1998. [CrossRef]

- J. Hulland, “Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: a review of four recent studies,” Strategic Management Journal, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 195–204, Feb. 1999.

- J. F. Hair, G. T. M. Hult, C. M. Ringle, M. Sarstedt, N. P. Danks, and S. Ray, “An Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling,” Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R, pp. 1–29, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. F. Hair Jr, M. Sarstedt, L. Hopkins, and V. G. Kuppelwieser, “Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM),” European Business Review, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 106–121, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- J. Yli-Huumo, D. Ko, S. Choi, S. Park, and K. Smolander, “Where Is Current Research on Blockchain Technology? —A Systematic Review,” PLOS ONE, vol. 11, no. 10, p. e0163477, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Saberi, M. Kouhizadeh, J. Sarkis, and L. Shen, “Blockchain technology and its relationships to sustainable supply chain management,” International Journal of Production Research, vol. 57, no. 7, pp. 2117–2135, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. Torrado Fonseca, M. Reguant Álvarez, and C. Quirós Domínguez, “DELPHI METHOD ON TRANSITIONS AND ACCESS PATHS TO MASTER'S DEGREES IN SOCIAL SCIENCES IN SPAIN,” Education: Theories, Methods, and Perspectives Vol I, pp. 248–258, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Nasa, R. Jain, and D. Juneja, “Delphi methodology in healthcare research: How to decide its appropriateness,” World Journal of Methodology, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 116–129, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Krebs et al., “Transforming Health Care Delivery towards Value-Based Health Care in Germany: A Delphi Survey among Stakeholders,” Healthcare, vol. 11, no. 8, p. 1187, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Y. Phoi, M. P. Bonham, M. Rogers, J. Dorrian, and A. M. Coates, “Content Validation of a Chrono nutrition Questionnaire for the General and Shift Work Populations: A Delphi Study,” Nutrients, vol. 13, no. 11, p. 4087, Nov. 2021. [CrossRef]