Submitted:

14 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Vegetation restorations are crucial strategies for combating land degradation, yet their mechanisms on improving soil quality, especially from perspective of soil fertility, remain far from clear. Sparse trees in semi-arid savanna grasslands (i.e., climate communities) offer a provoking reference for vegetation restoration. Here, taking advantage of Ulmus macrocarpa Hance fertile islands of the savanna ecosystem in the Daqinggou National Nature Reserve, this study aimed to investigate the vertical and horizontal distribution patterns of soil physicochemical properties and DOC fluorescence spectral characteristics. Results showed that soil organic carbon (SOC) and DOC were significantly decreased with both the increasing distance from tree and increasing soil depth. Horizontal and vertical treatments significantly enhanced fluorescence intensities of DOC. Additionally, the soil under canopy exhibited slightly richer concentrations of NH4+–N, NO3––N, TN, and TP at topsoil compared with deep soils. The SOC, TN, TP, NH4+–N, and NO3––N showed significantly positive relationships with the DOC. The study provides evidence that trees can form fertile island effects and enhance soil nutrients and DOC. These results are vital for guiding vegetation restoration degraded ecosystem in semi-arid area.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

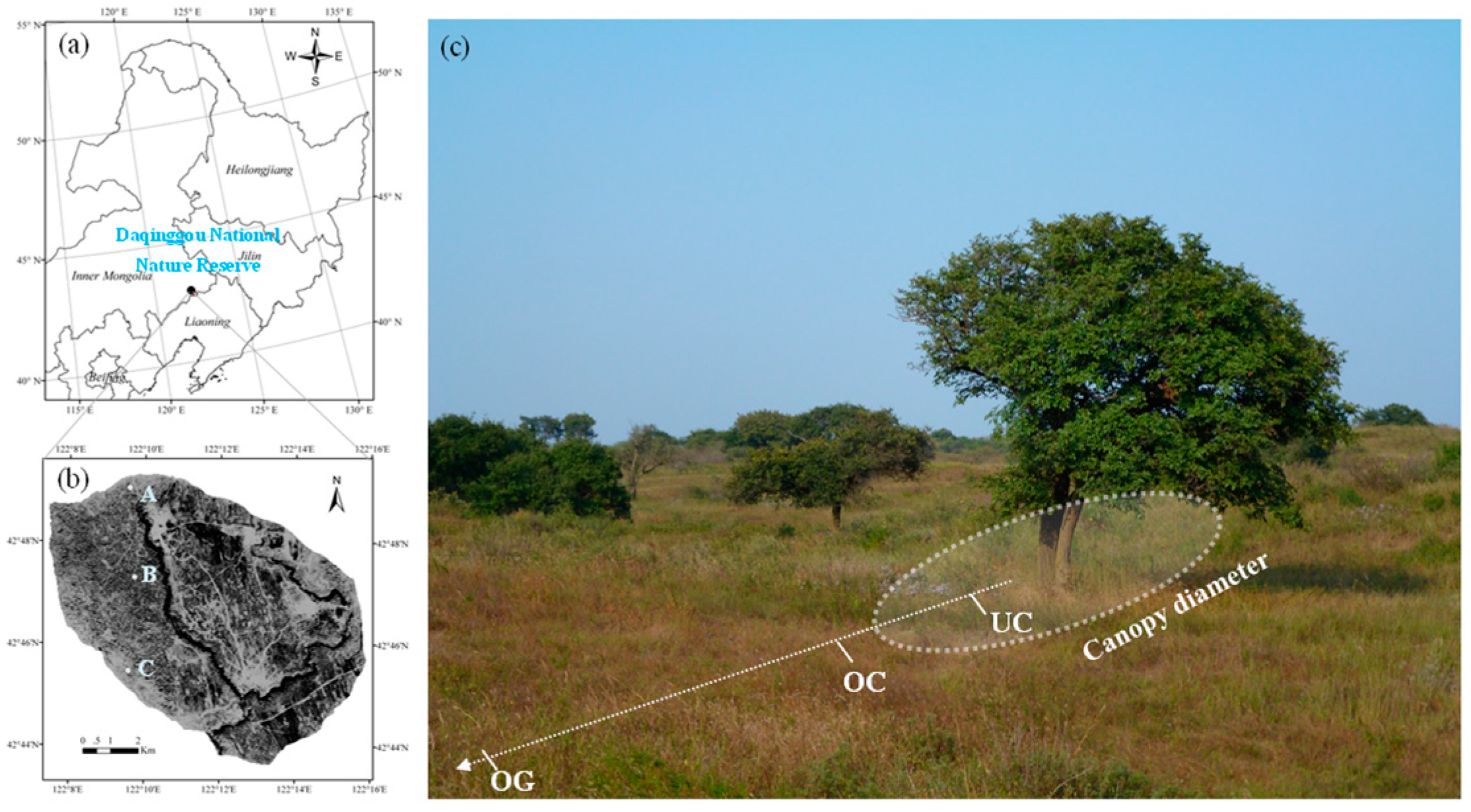

2.1. Study Area Description

2.2. Soil Collection

2.3. Laboratory Analyses

2.4. Calculation of SOC Density and DOC Fluorescence Indicators

2.5. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

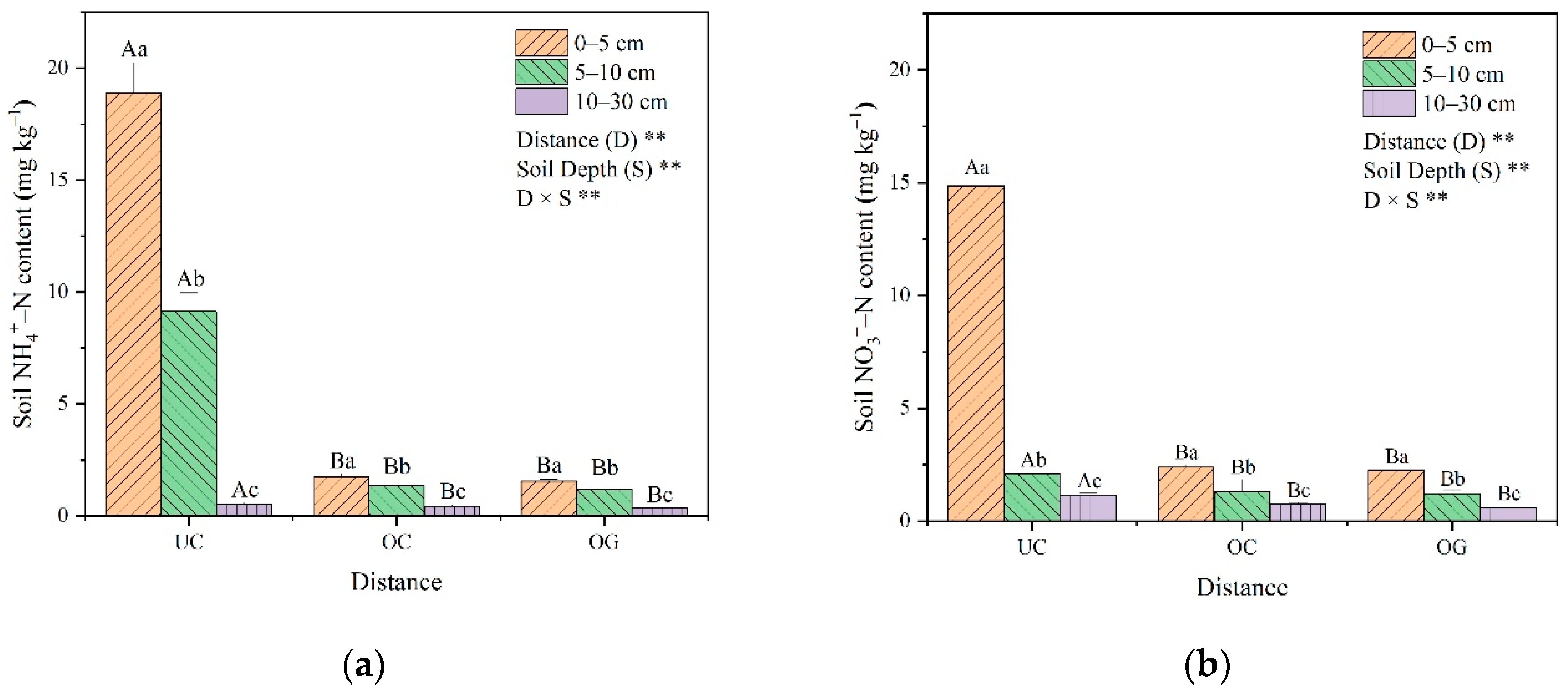

3.1. Soil Characteristics

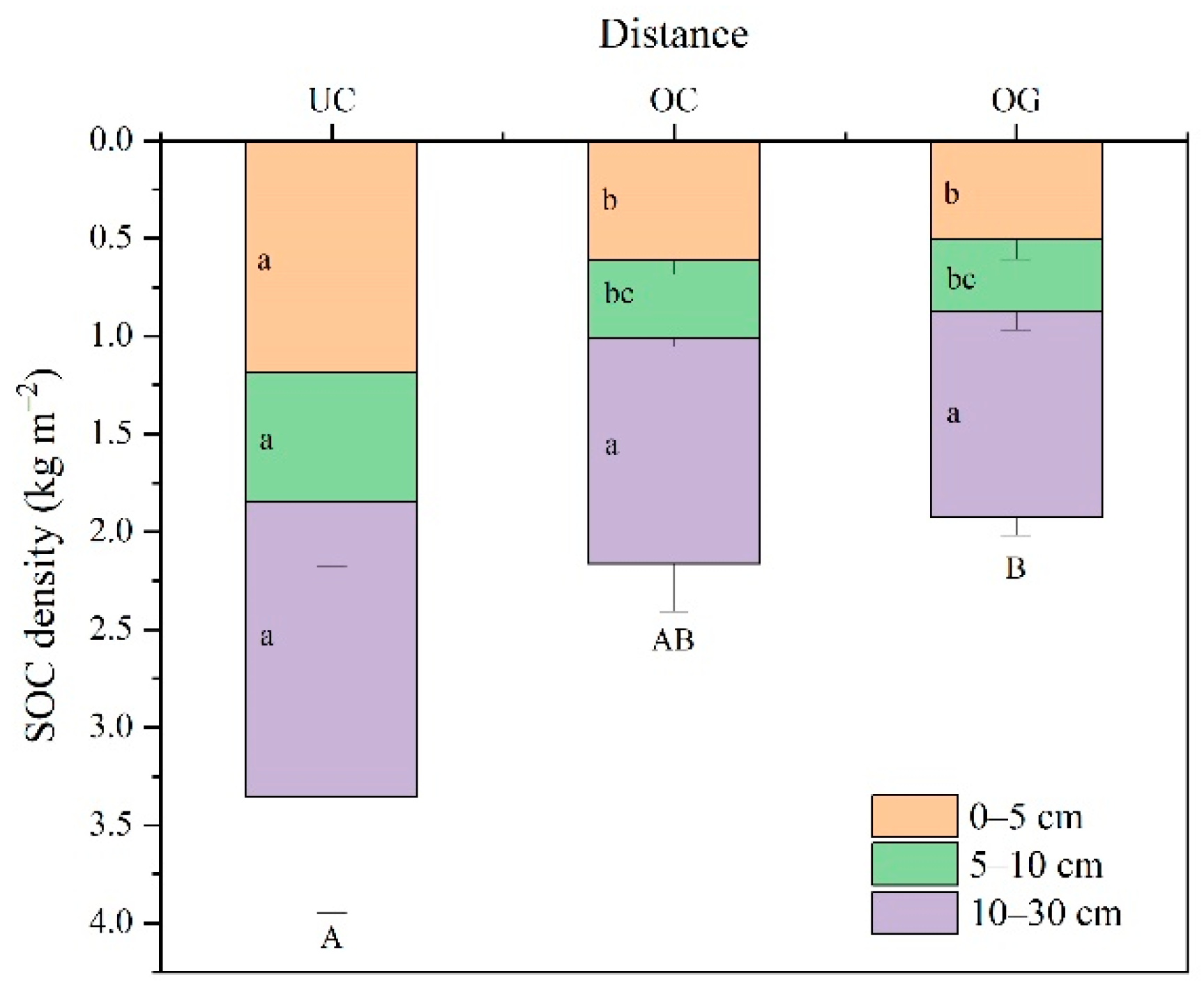

3.2. SOC Density

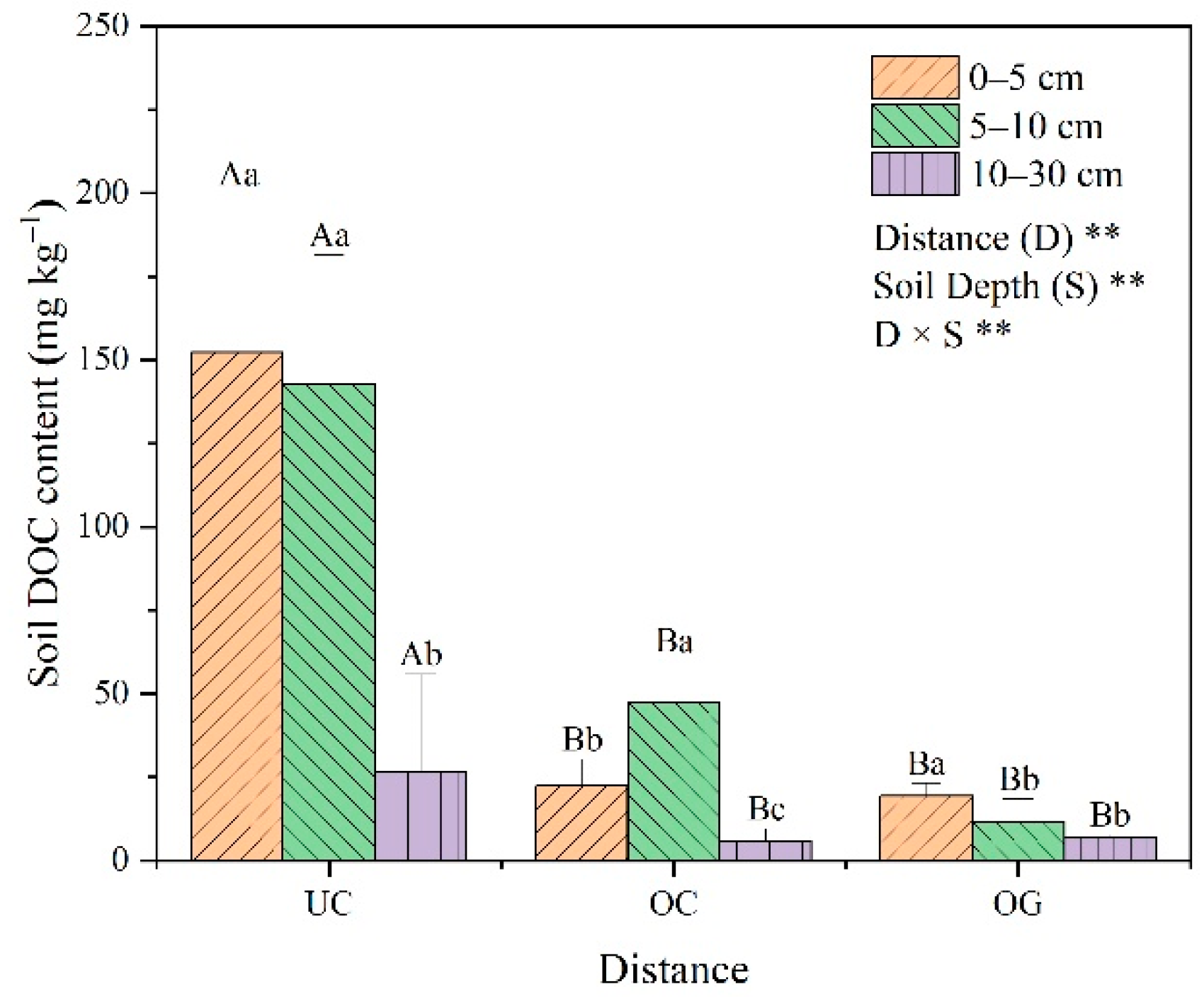

3.3. DOC Content and Fluorescence Excitation–Emission Matrix Spectra

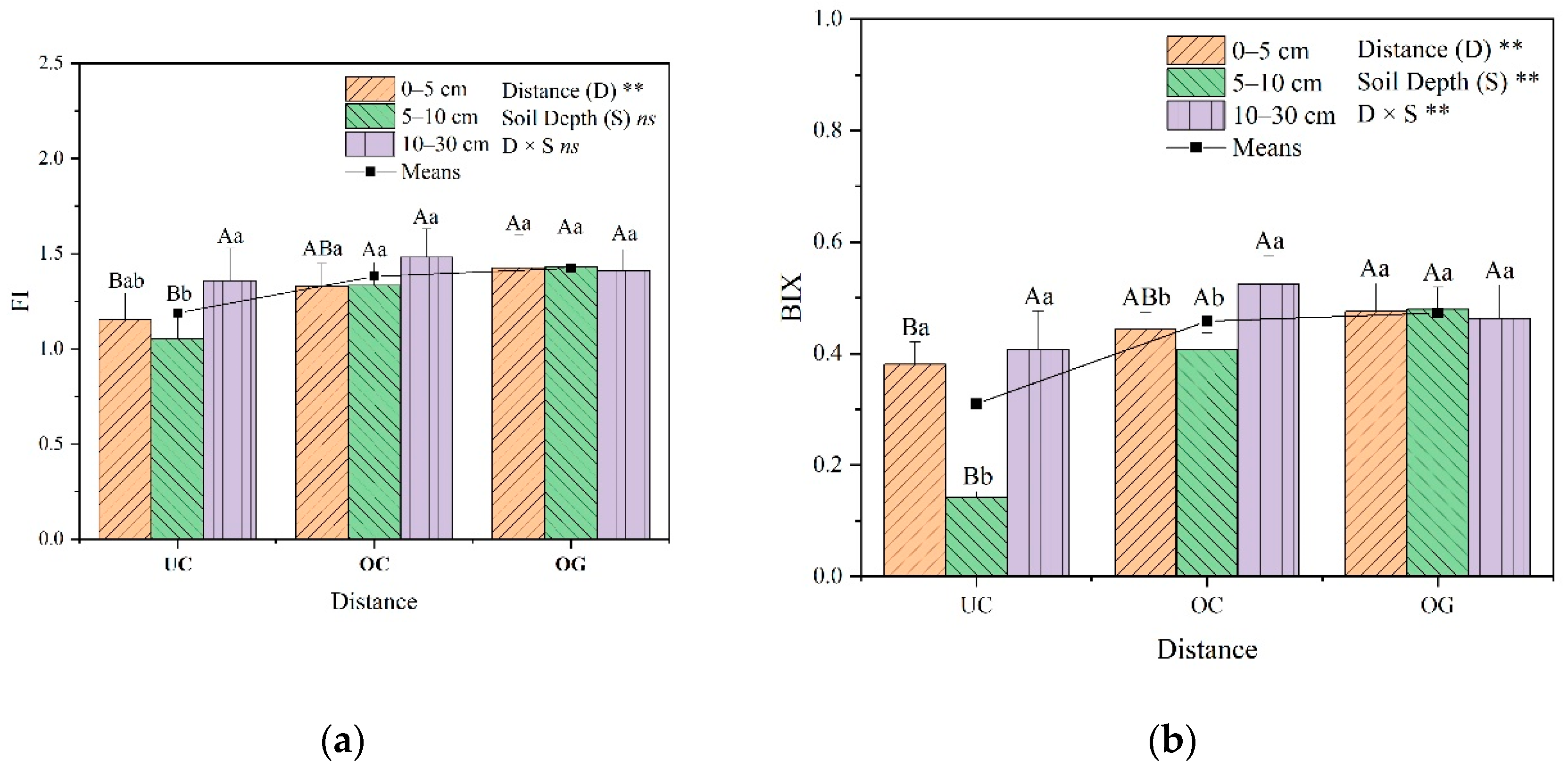

3.4. Fluorescence Indices Analysis

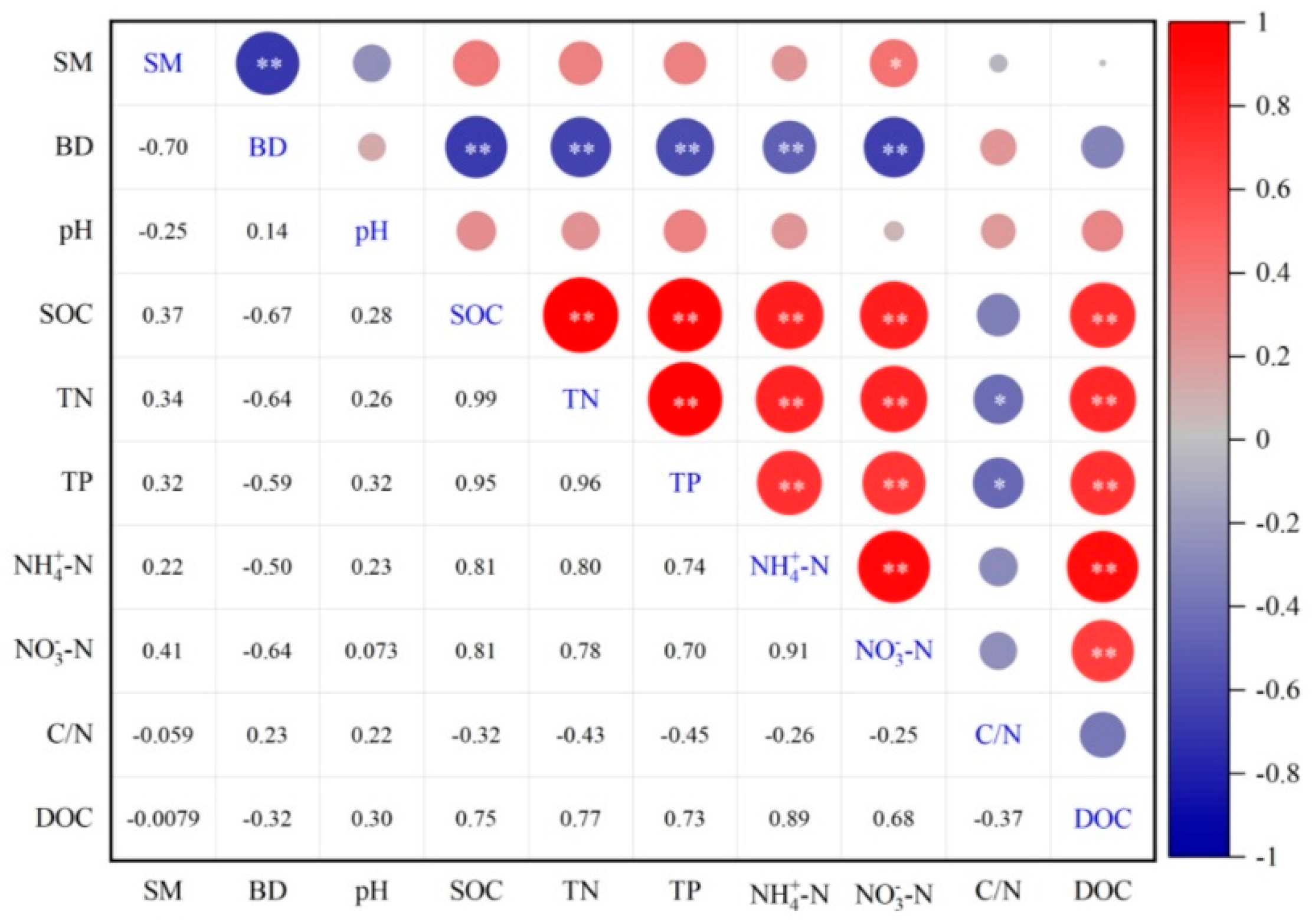

3.5. Correlations Between Soil Properties and DOC Content

4. Discussion

4.1. Impacts of Ulmus Macrocarpa Hance on Soil Nutrient Properties

4.2. Horizontal and Vertical Distributions of SOC Content and SOC Density in Ulmus Macrocarpa Hance Dominated Wood Grassland System

4.3. Effects of Ulmus Macrocarpa Hance on Soil DOC and Fluorescence Indicators

4.4. Implications for Relationships Between DOC and Soil Properties

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Niu, Y.Y.; Li, Y.Q.; Wang, M.M.; Wang, X.Y.; Chen, Y.; Duan, Y.L. Variations in seasonal and inter-annual carbon fluxes in a semi-arid sandy maize cropland ecosystem in China’s Horqin Sandy Land. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 5295–5312. [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.Y.; Li, Y.Q.; Liu, W.; Wang, X.Y.; Chen, Y. Effects of environment factors on the carbon fluxes of semi-fixed sandy land recovering from degradation. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1178660. DOI10.3389/fevo.2023.1178660.

- De Paola, F.; Ducci, D.; Giugni, M. Desertification and erosion sensitivity. A case study in southern Italy the Tusciano River catchment. Environ. Earth. Sci. 2013, 70, 2179–2190. [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.S.; Fazey, I.; Stringer, L.C.; Raymond, C.M.; Akhtar-Schuster, M.; Begni, G.; Bigas, H.; Brehm, S.; Briggs, J.; Bryce, R.; Buckmaster, S.; Chanda, R.; Davies, J.; Diez, E.; Essahli, W.; Evely, A.; Geeson, N.; Hartmann, I.; Holden, J.; Hubacek, K.; Ioris, A.A.R.; Kruger, B.; Laureano, P.; Phillipson, J.; Prell, C.; Quinn, C.H.; Reeves, A.D.; Seely, M.; Thomas, R.; Ten Bosch, M.J.V.; Vergunst, P.; Wagner, L. Knowledge management for land degradation monitoring and assessment: An analysis of contemporary thinking. Land Degrad. Dev. 2013, 24, 307–322. [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.L; Jia, C.; Huang, Z.; López-Vicente, M.; Liu, Y. Plant litter crust appear as a promising measure to combat desertification in sandy land ecosystem. Catena, 2021, 206, 105573. [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.Y.; Wang, Y.Q.; Wang, Z.Y. Linking priority areas and land restoration options to support desertification control in northern China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 137, 108747. DOI10.1016/j.ecolind.2022.108747.

- Xu, D.Y.; Wang, Z.Y. Identifying land restoration regions and their driving mechanisms in Inner Mongolia, China from 1981 to 2010. J. Arid Environ. 2019, 167, 79–86. [CrossRef]

- Takoutsing, B.; Winowiecki, L.A.; Bargués-Tobella, A.; Vågen, T.G. Determination of land restoration potentials in the semi-arid areas of Chad using systematic monitoring and mapping techniques. Agroforest. Syst. 2023, 97, 1289–1305. [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Tewari, S.K. Does the road to land degradation neutrality in India is paved with restoration science? Restor. Ecol. 2022, 30, e13585. [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.Q.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Y.F. Evaluating land restoration based on the land cover in the Horqin Sandy Land, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 2023, 30, 88417–88430. [CrossRef]

- Verhoeven, D.; Berkhout, E.; Sewell, A.; van der Esch, S. The global cost of international commitments on land restoration. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 4864–4874. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, D.J. Comparing the long-term effects of artificial and natural vegetation restoration strategies: A case-study of Wuqi and its adjacent counties in northern China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 3930–3945. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xiong, K.N. Soil Quality Assessment under different vegetation restoration strategies in the karst rocky deserted area of southwestern China. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nut. 2024, 24, 3249–3264. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.J.; Sun, Y.R; Zheng, X.; Yang, K.; Wang, G.G.; Xia, C.Z.; Sun, T.; Zhang, J.X. A large carbon sink induced by the implementation of the largest afforestation program on Earth. Ecol. Process. 2023, 12, 44. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.F.; Xiao, F.Y.; Feng, X.M.; Fu, B.J.; Zhou, Z.X.; Chan, C. Soil conservation on the loess plateau and the regional effect: Impact of the 'Grain for Green' project. Earth Environ. Sci. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 2019, 109, 461–471. [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.L.; Liu, Y.; Fang, N.F.; Deng, L.; Shi, Z.H. Soil physical properties response to grassland conversion from cropland on the semi-arid area. Ecohydrology 2016, 9, 1471–1479.

- Dou, Y.X.; Yang, Y.; An, S.S.; Zhu, Z.L. Effects of different vegetation restoration measures on soil aggregate stability and erodibility on the Loess Plateau, China. Catena 2020, 185, 104294. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Dang, P.; Zhao, Q.X.; Liu, J.L.; Liu, J.B. Effects of vegetation rehabilitation on soil organic and inorganic carbon stocks in the Mu Us Desert, northwest China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2018, 29, 1031–1040. [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Li, Q.L.; Yan, X.; Wu, X.Z.; Liu, R.T.; Fang, Y. Desertification control on soil inorganic and organic carbon accumulation in the topsoil of desert grassland in Ningxia, northwest China. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 127, 348–355.

- Siswo; Kim, H.; Lee, J.; Yun, C.W. Influence of tree vegetation and the associated environmental factors on soil organic carbon; Evidence from “Kulon Progo Community Forestry,” Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Forests, 2023, 14, 365. [CrossRef]

- Lange, M.; Eisenhauer, N.; Chen, H.M.; Gleixner, G. Increased soil carbon storage through plant diversity strengthens with time and extends into the subsoil. Global Change Biol. 2023, 29, 2627–2639. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.Z.; Li, L.; Yao, Y.F.; Qin, F.C.; Guo, Y.F.; Gao, Y.H.; Zhang, M.L. Spatial distribution of soil organic carbon and its influencing factors at different soil depths in a semiarid region of China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 654. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.Y.; Li, S.Y.; Zhou, W.Z.; He, L.B.; Zou, R.S.; Yu, J.T.; Chen, Z.; Bai, X.T.; Zhang, J.S.; Sun, X.Y. Comparative analysis of soil organic carbon and soil oxide minerals across different climates and forest types. Austrian J For. Sci. 2024, 141, 53–78. [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.C.; Fan, J.B.; He, Y.Q.; Luo, S.M.; Peng, X.H. Possible effect of soil organic carbon on its own turnover: A negative feedback. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2014, 69, 313–319. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.D.; Wang, G.; Ma, Q.X.; Liao, J.H.; Wang, D.; Guan, Q.W.; Jones, D.L. Organic mulching promotes soil organic carbon accumulation to deep soil layer in an urban plantation forest. For. Ecosyst. 2021, 8, 2. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.M.; Yao, F.Y.; Mi, G.H.; Wang, L.C.; Wu, H.Y.; Wang, Y.J. Crop rotation increases root biomass and promotes the correlation of soil dissolved carbon with the microbial community in the rhizosphere. Front. Bioeng. Biotech. 2022, 10, 1081647. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.Q.; Drury, C.F.; Kay, B.D. Soil dissolved organic carbon: Influences of water-filled pore space and red clover addition and relationships with microbial biomass carbon. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2004, 84, 151–158. [CrossRef]

- Mao, R.; Zeng, D.H.; Li, L.J.; Hu, Y.L. Changes in labile soil organic matter fractions following land use change from monocropping to poplar-based agroforestry systems in a semiarid region of Northeast China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2012, 184, 6845–6853. [CrossRef]

- Gielen, B.; Neirynck, J.; Luyssaert, S.; Janssens, I.A. The importance of dissolved organic carbon fluxes for the carbon balance of a temperate Scots pine forest. Agr. Forest Meteorol. 2011, 151, 270–278. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, R.; Kundu, S.; Srivastva, A.K.; Gupta, H.S.; Prakash, V.; Bhatt, J.C. Long term fertilization effects on soil organic carbon pools in a sandy loam soil of the Indian sub-Himalayas. Plant Soil, 2011, 341: 109–124. [CrossRef]

- Staddon, W.J.; Duchesne, L.C.; Trevors, J.T. The role of microbial indicators of soil quality in ecological forest management. Forest. Chron. 1999, 75, 81–86. [CrossRef]

- Katsuyama, M.; Ohte, N. Determining the sources of stormflow from the fluorescence properties of dissolved organic carbon in a forested headwater catchment. J. Hydrol. 2002, 268, 192–202. [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Sun, X.K.; Xu, C.B.; Ma, X.P.; Huang, Y.; Fan, Z.P.; Cao, X.Y. Effects of sewage sludge application on plant growth and soil characteristics at a Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica plantation in Horqin Sandy Land. Forests, 2022, 13, 984. [CrossRef]

- Oelbermann, M.; Voroney, R.P. Carbon and nitrogen in a temperate agroforestry system: Using stable isotopes as a tool to understand soil dynamics. Eco. Eng. 2007, 29, 342–349.

- Li, Y.F.; Li, Z.W.; Wang, Z.Y.; Wang, W.L.; Jia, Y.H.; Tian, S.M. Impacts of artificially planted vegetation on the ecological restoration of movable sand dunes in the Mugetan Desert, northeastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Int. J Sediment Res. 2017, 32, 277–287. [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.G.; Li, X.; Wang, B.; Miao, H.Z.; Sial, T.A.; Dong, Q.; Fu, G.J.; Li, L.M. Long-term vegetation restoration increases carbon sequestration of different soil particles in a semi-arid desert. Ecosphere 2021, 12, e03848. [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.K.; Atapattu, A.J.; Lin, L.X.; Xia, S.W.; Yang, X.D. Soil nutrient concentrations, associations and their relationships with canopy tree category and size in the southwestern China tropical rainforests. J. Sustain. Forest. 2023, 42, 1020–1035. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.L.; Li, X.G.; Zhao, L.; Kuzyakov, Y. Regulation of soil phosphorus cycling in grasslands by shrubs. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 133, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Maestre, F.T.; Eldridge, D.J.; Ke, W.B.; Hu, T.L.; Ye, J.S. Fertile island effects across soil depths in drylands of the Tibetan Plateau. Plant Soil 2024, 503, 385–396. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.K.; Shao, Y.Y.; Cui, Q.G.; Ye, X.H.; Huang, Z.Y. ‘Fertile island’ effects on the soil microbial community beneath the canopy of Tetraena mongolica, an endangered and dominant shrub in the West Ordos Desert, North China. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 178. [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.Q.; Guo, M.M.; Wang, W.L.; Shi, Q.H.; Guo, W.Z.; Lou, Y.B.; Zhu, Y.A.; Yang, H.; Xu, Y.Y. Evaluation of the effects of long-term natural and artificial restoration on vegetation characteristics, soil properties and their coupling coordinations. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 884, 163828. [CrossRef]

- Garbowski, M.; Avera, B.; Bertram, J.H.; Courkamp, J.S.; Gray, J.; Hein, K.M.; Lawrence, R.; McIntosh, M.; McClelland, S.; Post, A.K.; Slette, I.J.; Winkler, D.E.; Brown, C.S. Getting to the root of restoration: Considering root traits for improved restoration outcomes under drought and competition. Restor. Ecol. 2020, 28, 1384–1395. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.K.; Lou, L.; Bai, W.H.; Zhang, S.Q.; Zhang, N.N. Phosphorus deficiency is the main limiting factor for re-vegetation and soil microorganisms in Mu Us Sandy Land, Northwest China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 900, 165770. [CrossRef]

- Garbowski, M.; Johnston, D.B.; Baker, D.V.; Brown, C.S. Invasive annual grass interacts with drought to influence plant communities and soil moisture in dryland restoration. Ecosphere 2021, 12, e03417. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, X.; Yang, X.H.; Shi, Z.J.; Liu, Y.S. Grazing altered the pattern of woody plants and shrub encroachment in a temperate savanna ecosystem. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 330. [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, K.V.R.; de Bie, S.; Heitkönig, I.M.A.; Woodborne, S.; Gort, G.; Kirkman, K.P.; Prins, H.H.T. Competition with trees does not influence root characteristics of perennial grasses in semi-arid and arid savannas in South Africa. J. Arid Environ. 2016, 124, 270–277. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, L.N.; Yang, X.H.; Shi, Z.J.; Yu, P.T. Does shrub encroachment indicate ecosystem degradation? A perspective based on the spatial patterns of woody plants in a temperate savanna-like ecosystem of Inner Mongolia, China. Forests, 2020, 11, 1248. [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.Y.; Eldridge, D.J. The fertile island effect varies with aridity and plant patch type across an extensive continental gradient. Plant Soil 2021, 459, 173–183. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, C.; Zhu, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, F. Effect of plant species on shrub fertile island at an oasis–desert ecotone in the South Junggar Basin, China. J. Arid Environ. 2007, 71, 350–361. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.P; Huang, Y.; Sun, X.K.; Bai, J.; Lin, L.T.; Ai, G.Y. Effects of fertile islands on soil organic carbon density and labile organic carbon distribution in elm (Ulmus macrocarpa Hance)-dominated sparse wood grasslands in southeastern Inner Mongolia, China. Arid Land Res. Manag. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, C.B.; Singh, A.K.; Sharma, D.K. Soil properties under Acacia nilotica trees in a traditional agroforestry system in central India. Agroforest. Syst. 2000, 49, 53–61. [CrossRef]

- Gindaba, J.; Rozanov, A.; Negash, L. Trees on farms and their contribution to soil fertility parameters in Badessa, eastern Ethiopia. Biol. Fert. Soils 2005, 42, 66–71. [CrossRef]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I.A. An examination of the Degtjareff method for determining soil organic matter, and a proposed modification of the chromic acid titration method. Soil Sci. 1934, 37, 29–38. [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.T.; Sun, X.K.; Yu, Z.Y.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, D.H. Responses of soil respiration to N fertilization and grazing in a Keerqin sandy grassland in northeast China. Arid Land Res. Manag. 2021, 35, 230–245. [CrossRef]

- Zsolnay, A.; Baigar, E.; Jimenez, M.; Steinweg, B.; Saccomandi, F. Differentiating with fluorescence spectroscopy the sources of dissolved organic matter in soils subjected to drying. Chemosphere 1999, 38, 45–50. [CrossRef]

- Halbedel, S.; Herzsprung, P. Short communication on “Differentiating with fluorescence spectroscopy the sources of dissolved organic matter in soils subjected to drying” [Zsolnay et al. Chemosphere 38, 45–50, 1999]. Chemosphere 2020, 239, 124818. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.Y.; Qian, W.; Wu, L.; Yu, S.H.; Wei, R.; Chen, W.F.; Ni, J.Z. Spectral characteristics of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) derived from biomass pyrolysis: Biochar-derived DOC versus smoke-derived DOC, and their differences from natural DOC. Chemosphere 2022, 302, 134869. [CrossRef]

- de Freitas, A.F.; Carneiro, J.J.; Venturin, N.; Moreira, F.M.D.; Ferreira, A.I.G.; Lara, G.P.D.; Miranda, R.D.; de Siqueira, L.F.; Cardoso, I.M. Inga edulis Mart. intercropped with pasture improves soil quality without compromising forage yields. Agroforest. Syst. 2020, 94, 2355–2366. [CrossRef]

- Mao, N.; Huang, L.; Shao, M. Vertical distribution of soil organic and inorganic carbon under different vegetation covers in two toposequences of the Liudaogou watershed on the Loess Plateau, China. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2018, 73, 479–491. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shangguan, Z.; Deng, L. Vegetation type and soil moisture drive variations in leaf litter decomposition following secondary forest succession. Forests 2021, 12, 1195. [CrossRef]

- Asaye, Z.; Zewdie, S. Fine root dynamics and soil carbon accretion under thinned and un-thinned Cupressus lusitanica stands in, Southern Ethiopia. Plant Soil, 2013, 366, 261–271. [CrossRef]

- D'Hervilly, C.; Marsden, C.; Capowiez, Y.; Béral, C.; Delapré-Cosset, L.; Bertrand, I. Trees and herbaceous vegetation strips both contribute to changes in soil fertility and soil organism communities in an agroforestry system. Plant Soil, 2021, 463, 537–553. [CrossRef]

- Belsky, A.J.; Amundson, R.G.; Duxbury, J.M.; Riha, S.J.; Ali, A.R.; Mwonga, S.M. The effects of trees on their physical, chemical, and biological environments in a semi-arid savanna in Kenya. J. Appl. Ecol. 1989, 26, 1005–1024. [CrossRef]

- Gispert, M.; Emran, M.; Pardini, G.; Doni, S.; Ceccanti, B. The impact of land management and abandonment on soil enzymatic activity, glomalin content and aggregate stability. Geoderma, 2013, 202, 51–61. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.F.; Zhao, Z.N.; Wei, X.R.; Shao, M.A. Effects of shrub species on soil nitrogen mineralization in the desert loess transition zone. Catena, 2019, 173, 330–338. [CrossRef]

- Gallardo, A.; Rodríguez-Saucedo, J.J.; Covelo, F.; Fernández-Alés, R. Soil nitrogen heterogeneity in a Dehesa ecosystem. Plant Soil, 2000, 222, 71–82. [CrossRef]

- Fall, D.; Diouf, D.; Zoubeirou, A.M.; Bakhoum, N.; Faye, A.; Sall, S.N. Effect of distance and depth on microbial biomass and mineral nitrogen content under Acacia senegal (L.) Willd. trees. J. Environ. Manage. 2012, 95, S260–S264. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.J.; Tariq, A.; Zeng, F.J.; Sardans, J.; Zhang, Z.H.; Islam, W.; Xu, M.Q.; Penuelas, J. “Fertile islands” beneath three desert vegetation on soil phosphorus fractions, enzymatic activities, and microbial biomass in the desert-oasis transition zone. Catena, 2022, 212, 106090. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.L.; Lin, G.G.; Zeng, D.H. Long-term nitrogen addition modifies fine root growth and vertical distribution by affecting soil nutrient availability in a Mongolian pine plantation. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 921, 171168. [CrossRef]

- Gebrewahid, Y.; Teka, K.; Gebre-Egziabhier, T.B.; Tewolde-Berhan, S.; Birhane, E.; Eyasu, G.; Meresa, E. Dispersed trees on smallholder farms enhance soil fertility in semi-arid Ethiopia. Ecol. Process. 2019, 8, 38. [CrossRef]

- Ljalem, S.; Birhane, E.; Teka, K.; Berhe, D.H. Parkland trees on smallholder farms ameliorate soil physical-chemical properties in the semi-arid area of Tigray, Ethiopia. J. Arid Land 2024, 16, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Arunrat, N.; Sansupa, C.; Sereenonchai, S. Hatano, R. Stability of soil bacteria in undisturbed soil and continuous maize cultivation in Northern Thailand. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1285445. [CrossRef]

- Toled, S.; Peri, P.L.; Correa, O.S.; Montecchia, M.S.; Gargaglione, V.B.; Ladd, B. Structure and function of soil microbial communities in fertile islands in austral drylands. Austral Ecol. 2022, 47, 663–673. [CrossRef]

- Bobul'ská, L.; Espíndola, S.P.; Coelho, M.A.; Ferreira, A.S. Impact of land use on soil function and bacterial community in the Brazilian savanna. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2021, 93, e20201906. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Jia, X.X.; Li, M.; Wu, H.M. Insight into the vertical characteristics of dissolved organic matter in 5-m soil profiles under different land-use types on the Loess Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 692: 613–621. DOI: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.339.

- Wickland, K.P.; Neff, J.C.; Aiken, G.R. Dissolved organic carbon in Alaskan boreal forest: Sources, chemical characteristics, and biodegradability. Ecosystems 2007, 10, 1323–1340. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.Q.; Huang, Q.Q.; Yan, T.Y.; Yang, J.F.; Zheng, Y.; Li, H.K.; Li, M. Effects of intercropping mulch on the content and composition of soil dissolved organic matter in apple orchard on the loess plateau. J. Environ. Manage. 2019, 250, 109531. [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.M.; Boyer, E.W.; Westerhoff, P.K.; Doran, P.T.; Kulbe, T.; Andersen, D.T. Spectrofluorometric characterization of dissolved organic matter for indication of precursor organic material and aromaticity. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2001, 46, 38–48. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Q.; Li, Y.; Ye, J.; Chen, Z.H.; Ren, D.J.; Zhang, S.Q. The spectral characteristics and cadmium complexation of soil dissolved organic matter in a wide range of forest lands. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 299, 118834. [CrossRef]

- Gui, X.Y.; Liu, C.; Li, F.Y.; Wang, J.F. Effect of pyrolysis temperature on the composition of DOM in manure-derived biochar. Ecotox. Environ. Safe. 2020, 197, 110597. [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.L.; Zhang, S.L.; Xie, L.C.; Li, X.; Sial, T.A.; Shar, A.G.; Fan, J.L.; Zhang, J.G.; Dong, Q.; Fu, G.J. Effects of Artemisia ordosica on fine-scale spatial distribution of soil C, N and P and physical–chemical properties in the Mu Us Desert, China. J. Soil. Sediment. 2022, 22, 172–184. [CrossRef]

- Cotrufo, M.F.; Soong, J.L.; Horton, A.J.; Campbell, E.E.; Haddix, M.L.; Wall, D.H.; Parton, A.J. Formation of soil organic matter via biochemical and physical pathways of litter mass loss. Nat. Geosci. 2015, 8, 776–779. [CrossRef]

- Froberg, M.; Kleja, D.B.; Hagedorn, F. The contribution of fresh litter to dissolved organic carbon leached from a coniferous forest floor. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2007, 58, 108–114. [CrossRef]

- Bongiorno, G.; Bünemann, E.K.; Oguejiofor, C.U.; Meier, J.; Gort, G.; Comans, R.; Mäder, P.; Brussaard, L.; de Goede, R. Sensitivity of labile carbon fractions to tillage and organic matter management and their potential as comprehensive soil quality indicators across pedoclimatic conditions in Europe. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 99, 38–50. [CrossRef]

- Lange, M.; Eisenhauer, N.; Sierra, C.A.; Bessler, H.; Engels, C.; Griffiths, R.I.; Mellado-Vázquez, P.G.; Malik, A.A.; Roy, J.; Scheu, S.; Steinbeiss, S.; Thomson, B.C.; Trumbore, S.E.; Gleixner, G. Plant diversity increases soil microbial activity and soil carbon storage. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6707. [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Zhang, Y.L.; Jin, S.; Wang, J.A.; Wei, Y.Y.; Cui, N.; Wei, W. Effect of different irrigation methods on dissolved organic carbon and microbial biomass carbon in the greenhouse soil. Agr. Sci. China 2010, 9, 1175–1182. [CrossRef]

| Horizon | Soil Layer (cm) |

Soil Moisture (%) |

Bulk Density (g cm–3) |

pH | SOC (g kg–1) |

TN (g kg–1) |

TP (g kg–1) |

C/N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UC | 0–5 | 12.12(0.82)Aa | 1.27(0.09)Ab | 6.71(0.27)Aa | 18.65(8.98)Aa | 1.51(0.82)Aa | 0.21(0.08)Aa | 12.65(1.31)Aa | |

| 5–10 | 5.33(2.09)Ab | 1.51(0.03)Aa | 6.79(0.22)Aa | 8.75(4.40)Ab | 0.69(0.46)Ab | 0.15(0.07)Aa | 13.48(2.53)Aa | ||

| 10–30 | 5.46(2.59)Ab | 1.54(0.06)Aa | 6.86(0.18)Aa | 4.90(1.93)Ab | 0.35(0.15)Ab | 0.11(0.04)Ab | 14.08(1.35)Aa | ||

| OC | 0–5 | 11.79(1.02)Aa | 1.33(0.07)Ab | 6.62(0.01)ABa | 9.18(1.10)Ba | 0.63(0.14)Ba | 0.13(0.03)Ba | 14.69(1.46)Aa | |

| 5–10 | 7.55(1.71)Ab | 1.47(0.02)Aa | 6.69(0.06)ABa | 5.47(0.59)Bb | 0.40(0.05)Bb | 0.11(0.02)Ba | 13.61(0.40)Aa | ||

| 10–30 | 7.44(0.84)Ab | 1.55(0.07)Aa | 6.73(0.07)ABa | 3.71(0.79)Bb | 0.26(0.05)Bb | 0.09(0.02)Bb | 14.29(0.74)Aa | ||

| OG | 0–5 | 10.71(4.61)Aa | 1.35(0.09)Ab | 6.51(0.04)Ba | 7.45(1.57)Ba | 0.57(0.18)Ba | 0.13(0.03)Ba | 13.32(1.78)Aa | |

| 5–10 | 9.69(4.78)Ab | 1.49(0.04)Aa | 6.55(0.07)Ba | 5.00(1.25)Bb | 0.38(0.09)Bb | 0.10(0.02)Ba | 13.29(0.48)Aa | ||

| 10–30 | 7.67(3.21)Ab | 1.51(0.06)Aa | 6.56(0.04)Ba | 3.47(0.32)Bb | 0.27(0.02)Bb | 0.09(0.01)Bb | 12.87(0.30)Aa | ||

| Two-way ANOVA analysis | |||||||||

| Distance (D) | ns | ns | ** | ** | * | * | ns | ||

| Soil Depth (S) | ** | ** | ns | ** | ** | * | ns | ||

| D × S | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).