Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

14 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fungal Material

2.2. Fermentation, Extraction, and Isolation of Compounds

2.3. Structural Identification

3. Results

3.1. Structural Identification of the Compounds

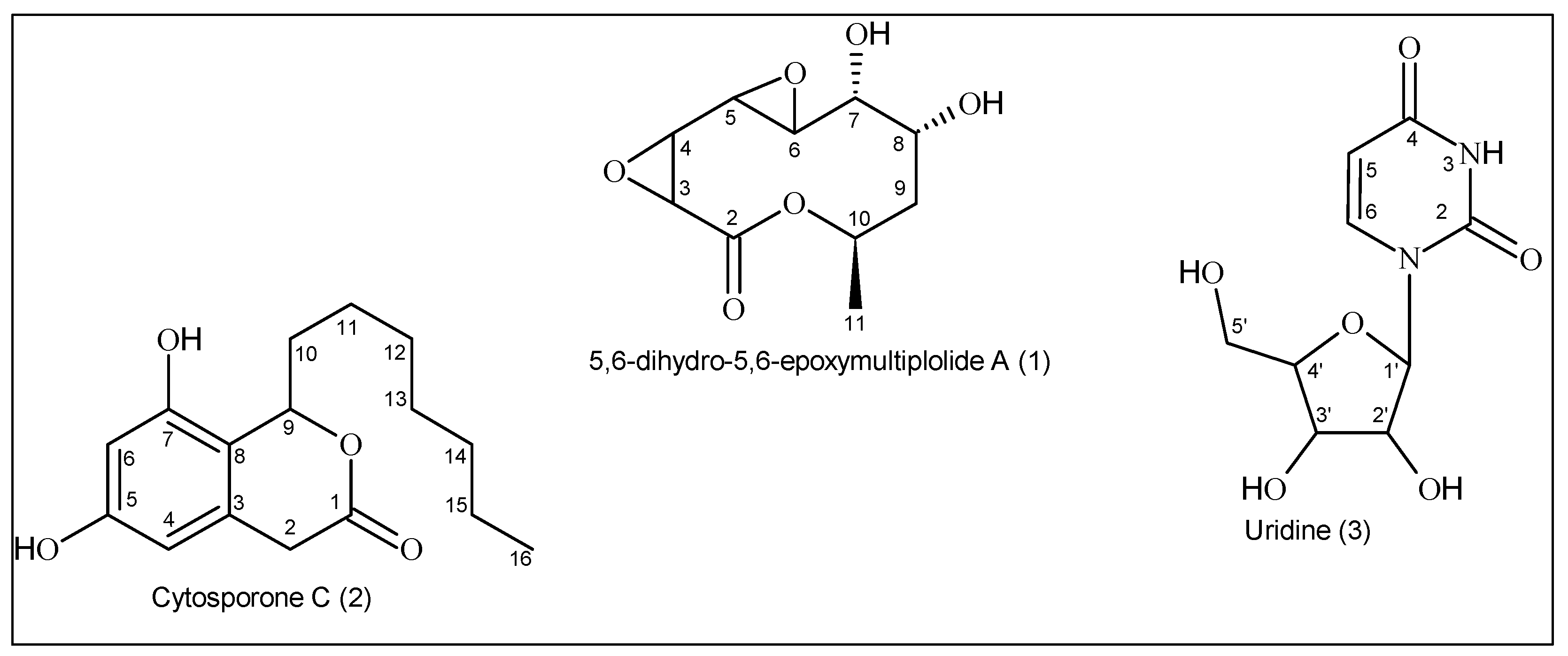

3.1.1. 5,6-Dihydro-5,6-epoxymultiplolide A (1)

3.1.2. Cytosporone C (2)

3.1.3. Uridine (3)

3.1.4. NMR Measurements

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wei, W.; Khan, B.; Dai, Q.; Lin, J.; Kang, L.; Rajput, N.A.; Yan, W.; Liu, G. Potential of Secondary Metabolites of Diaporthe Species Associated with Terrestrial and Marine Origins. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noriler, S.A.; Savi, D.C.; Aluizio, R.; Palácio-Cortes, A.M.; Possiede, Y.M.; Glienke, C. Bioprospecting and Structure of Fungal Endophyte Communities Found in the Brazilian Biomes, Pantanal, and Cerrado. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemkuignou, B.M.; Lambert, C.; Stadler, M.; Fogue, S.K.; Marin-Felix, Y. Unprecedented Antimicrobial and Cytotoxic Polyketides from Cultures of Diaporthe africana sp. nov. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manichart, N.; Laosinwattana, C.; Somala, N.; Teerarak, M.; Chotsaeng, N. Physiological mechanism of action and partial separation of herbicide–active compounds from the Diaporthe sp. extract on Amaranthus tricolor L. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, K.S.; Alves, J.L.; Pereira, O.L.; de Queiroz, M.V. Five new species of endophytic Penicillium from rubber trees in the Brazilian Amazon. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 3051–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camargo, J. L.; Ferraz, I. D. Minquartia guianensis Aubl. Manual de Sementes da Amazônia. INPA, p. 1–7, 2004.

- Costa-Lima, J.L.; Chagas, E.C.O. Coulaceae in Flora e Funga do Brasil. Jardim Botânico do Rio de Janeiro, 2020. Available online: https://floradobrasil.jbrj.gov.br/consulta/ficha.html?idDadosListaBrasil=618588. Accessed on January 3, 2025.

- Majid, M.; Ganai, B.A.; Wani, A.H. Antifungal, Antioxidant Activity, and GC–MS Profiling of Diaporthe amygdali GWS39: A First Report Endophyte from Geranium wallichianum. Curr. Microbiol. 2024, 82, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanapichatsakul, C.; Monggoot, S.; Gentekaki, E.; Pripdeevech, P. Antibacterial and Antioxidant Metabolites of Diaporthe spp. Isolated from Flowers of Melodorum fruticosum. Curr. Microbiol. 2017, 75, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Xing, S.; Wei, X.; Lu, J.; Zhao, G.; Ma, X.; Dai, Z.; Liang, X.; Huang, W.; Liu, Y.; et al. 12-O-deacetyl-phomoxanthone A inhibits ovarian tumor growth and metastasis by downregulating PDK4. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 175, 116736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, L.L. Bioprospecção de Fungos Endofíticos de Minquartia guianensis Aubl. Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade do Estado do Amazonas, 2016, 86p.

- Farinella, V.F.; Kawafune, E.S.; Tangerina, M.M.P.; Domingos, H.V.; Costa-Lotufo, L.V.; Ferreira, M.J.P. OSMAC Strategy Integrated with Molecular Networking for Accessing Griseofulvin Derivatives from Endophytic Fungi of Moquiniastrum polymorphum (Asteraceae). Molecules 2021, 26, 7316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, E.M.P. Produtos Naturais de Bignonia magnifica W. Bull. (Bignoniaceae) e a Prospecção Metabólica dos Seus Fungos Endofíticos. Tese de Doutorado, Universidade de São Paulo, 2023, 170p.

- Tan, Q.; Yan, X.; Lin, X.; Huang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Song, S.; Lu, C.; Shen, Y. Chemical Constituents of the Endophytic Fungal Strain Phomopsis sp. NXZ-05 of Camptotheca acuminata. Helvetica Chim. Acta 2007, 90, 1811–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, S.F.; Wagenaar, M.M.; Singh, M.P.; Janso, J.E.; Clardy, J. The Cytosporones, New Octaketide Antibiotics Isolated from an Endophytic Fungus. Org. Lett. 2000, 2, 4043–4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walczak, D.; Sikorski, A.; Grzywacz, D.; Nowacki, A.; Liberek, B. Characteristic 1H NMR spectra of β-d-ribofuranosides and ribonucleosides: factors driving furanose ring conformations. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 29223–29239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Tomm, H.; Ucciferri, L.; Ross, A.C. Advances in microbial culturing conditions to activate silent biosynthetic gene clusters for novel metabolite production. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 46, 1381–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muchlisyiyah, J.; Shamsudin, R.; Basha, R.K.; Shukri, R.; How, S.; Niranjan, K.; Onwude, D. Parboiled Rice Processing Method, Rice Quality, Health Benefits, Environment, and Future Perspectives: A Review. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geris, R.; de Jesus, V.E.T.; da Silva, A.F.; Malta, M. Exploring Culture Media Diversity to Produce Fungal Secondary Metabolites and Cyborg Cells. Chem. Biodivers. 2024, 21, e202302066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonphong, S.; Kittakoop, P.; Isaka, M.; Pittayakhajonwut, D.; Tanticharoen, M.; Thebtaranonth, Y. Multiplolides A and B, New Antifungal 10-Membered Lactones from Xylaria multiplex. J. Nat. Prod. 2001, 64, 965–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Yang, X.-Q.; Wan, C.-P.; Wang, B.-Y.; Yin, H.-Y.; Shi, L.-J.; Wu, Y.-M.; Yang, Y.-B.; Zhou, H.; Ding, Z.-T. Potential antihyperlipidemic polyketones from endophytic Diaporthe sp. JC-J7 in Dendrobium nobile. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 41810–41817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, B.; Singh, P. Epoxides: Developability as active pharmaceutical ingredients and biochemical probes. Bioorganic Chem. 2022, 125, 105862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, J.F.; Fouces, R.; Mendes, M.V.; Olivera, N.; Martı́n, J.F. A complex multienzyme system encoded by five polyketide synthase genes is involved in the biosynthesis of the 26-membered polyene macrolide pimaricin in Streptomyces natalensis. Chem. Biol. 2000, 7, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, H.; Òmura, S. Biosynthesis, Regulation, and Genetics of Macrolide Production. Macrolide Antibiot. : Chem. Biochem. Pract. 2003, 2, 285–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.-Q.; Du, S.-T.; Xiao, J.; Wang, D.-C.; Han, W.-B.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, J.-M. Isolation and Characterization of Antifungal Metabolites from the Melia azedarach-Associated Fungus Diaporthe eucalyptorum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 2418–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Guo, S.; Xie, C.; Fang, J. Uridine Metabolism and Its Role in Glucose, Lipid, and Amino Acid Homeostasis. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khezri, M.K.; Turkkan, A.; Koc, C.; Salman, B.; Levent, P.; Cakir, A.; Kafa, I.M.; Cansev, M.; Bekar, A. Uridine treatment improves nerve regeneration and functional recovery in a rat model of sciatic nerve injury. Turk. Neurosurg. 2021, 32, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumel, B.S.; Doraiswamy, P.M.; Sabbagh, M.; Wurtman, R. Potential Neuroregenerative and Neuroprotective Effects of Uridine/Choline-Enriched Multinutrient Dietary Intervention for Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Narrative Review. Neurol. Ther. 2020, 10, 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbour, C.A.; Imperiali, B. Uridine natural products: Challenging targets and inspiration for novel small molecule inhibitors. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2020, 28, 115661–115661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, N.P.; Turner, G.; Bennett, J.W. Fungal secondary metabolism — from biochemistry to genomics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brakhage, A.A. Regulation of fungal secondary metabolism. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 11, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaijmakers, J.M.; Mazzola, M. Diversity and Natural Functions of Antibiotics Produced by Beneficial and Plant Pathogenic Bacteria. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2012, 50, 403–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netzker, T.; Fischer, J.; Weber, J.; Mattern, D.J.; König, C.C.; Valiante, V.; Schroeckh, V.; Brakhage, A.A. Microbial communication leading to the activation of silent fungal secondary metabolite gene clusters. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 299–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traut, T.W. Physiological concentrations of purines and pyrimidines. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1994, 140, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolfes, R. Regulation of purine nucleotide biosynthesis: in yeast and beyond. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006, 34, 786–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mousa, W.K.; Raizada, M.N. Biodiversity of genes encoding anti-microbial traits within plant associated microbes. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 231–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusari, S.; Singh, S.; Jayabaskaran, C. Biotechnological potential of plant-associated endophytic fungi: hope versus hype. Trends Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, D. J.; Cragg, G. M. Natural Products as Sources of New Drugs over the Nearly Four Decades from 01/1981 to 09/2019. Journal of Natural Products 2020, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bills, G.F.; Gloer, J.B. Biologically Active Secondary Metabolites from the Fungi. Microbiol. Spectr. 2016, 4, 1087–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).