1. Introduction

Ultrasonic TOFD imaging, as an important imaging method for the pipeline girth welds nondestructive testing, uses diffraction time difference as the basic parameter for quantitatively detecting internal defects . It complements with the phased array zonal ultrasonic imaging method and can provide more precise defect distribution of girth welds. TOFD has become one of the most important methods for quantitative evaluation of weld quality at present, especially for the quantitative characterization of the size and burial depth of vertical crack defects inside the weld seam, it exhibits obvious technical advantages. However, this imaging method has always been affected by signal oscillations caused by the limited frequency band of the transducer and the inherent diffraction effect of defective echo scattering, resulting in unsatisfactory longitudinal and transverse resolutions, the existence of detection blind area, and insufficient detection accuracy. In addition, the real-time limitations of its time-domain imaging method seriously affect the detection performance and online application ability of this method. For this reason, classic deconvolution techniques such as parameterized inverse filtering [

1,

2], high-order spectral analysis (cepstral theory) [

3], and L2 regularized norm reconstruction [

4,

5] have been applied, effectively improving the longitudinal resolution of ultrasound TOFD imaging.Nevertheless, there are still technical pain points such as low signal-to-noise ratio and low contrast ratio, and further requirements of resolution enhancement.

For improving lateral resolution, time-domain SAFT technology is mainly used [

6,

7] , which calculates the wave arrival delay between the transducer and the defect, and reconstructs the defect imaging target data through the delay and sum rule. The calculation process of this method is simple, but it requires point-to-point calculation of the imaging area, with limited accuracy and efficiency. TOFD has become one of the most important methods for quantitative evaluation of weld quality at present, especially for the quantitative characterization of the size and burial depth of vertical crack defects inside the weld seam, it exhibits obvious technical advantages [

8,

9]. However, this numerical reconstruction method requires repeated iterative computation, which brings heavy computational burden. Recently, frequency-domain SAFT methods, also known as wavenumber-domain SAFT, have been widely studied due to their high-quality imaging result and high computational efficiency. The performance of frequency-domain SAFT have been verified in different modes, such as monostatic ultrasonic imaging [

10,

11], total focusing method ultrasonic imaging [

12,

13], compound plane wave ultrasonic imaging [

14,

15], etc. However, this method is established on the foundation of specific ultrasonic imaging model, which is still not be studied in TOFD ultrasonic imaging.

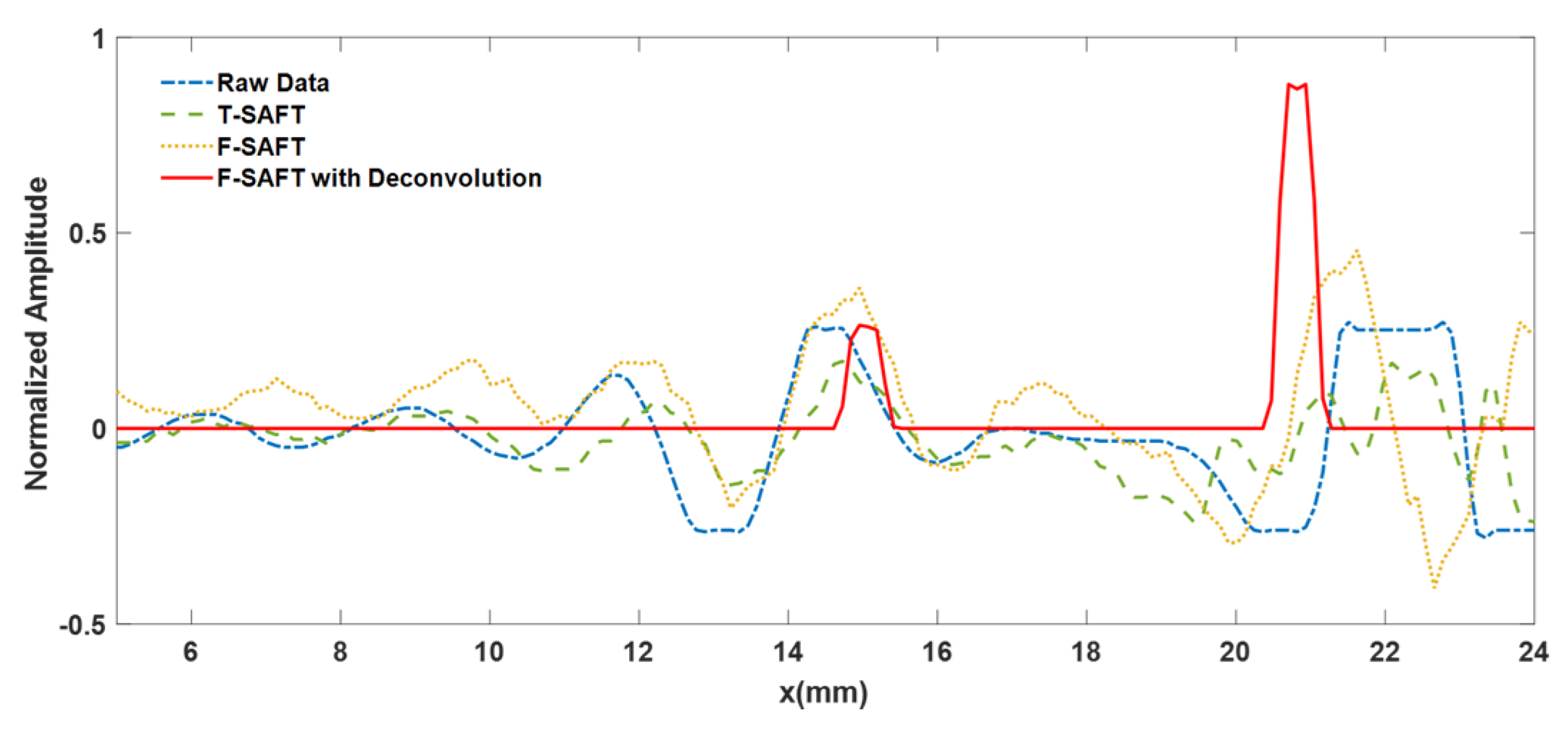

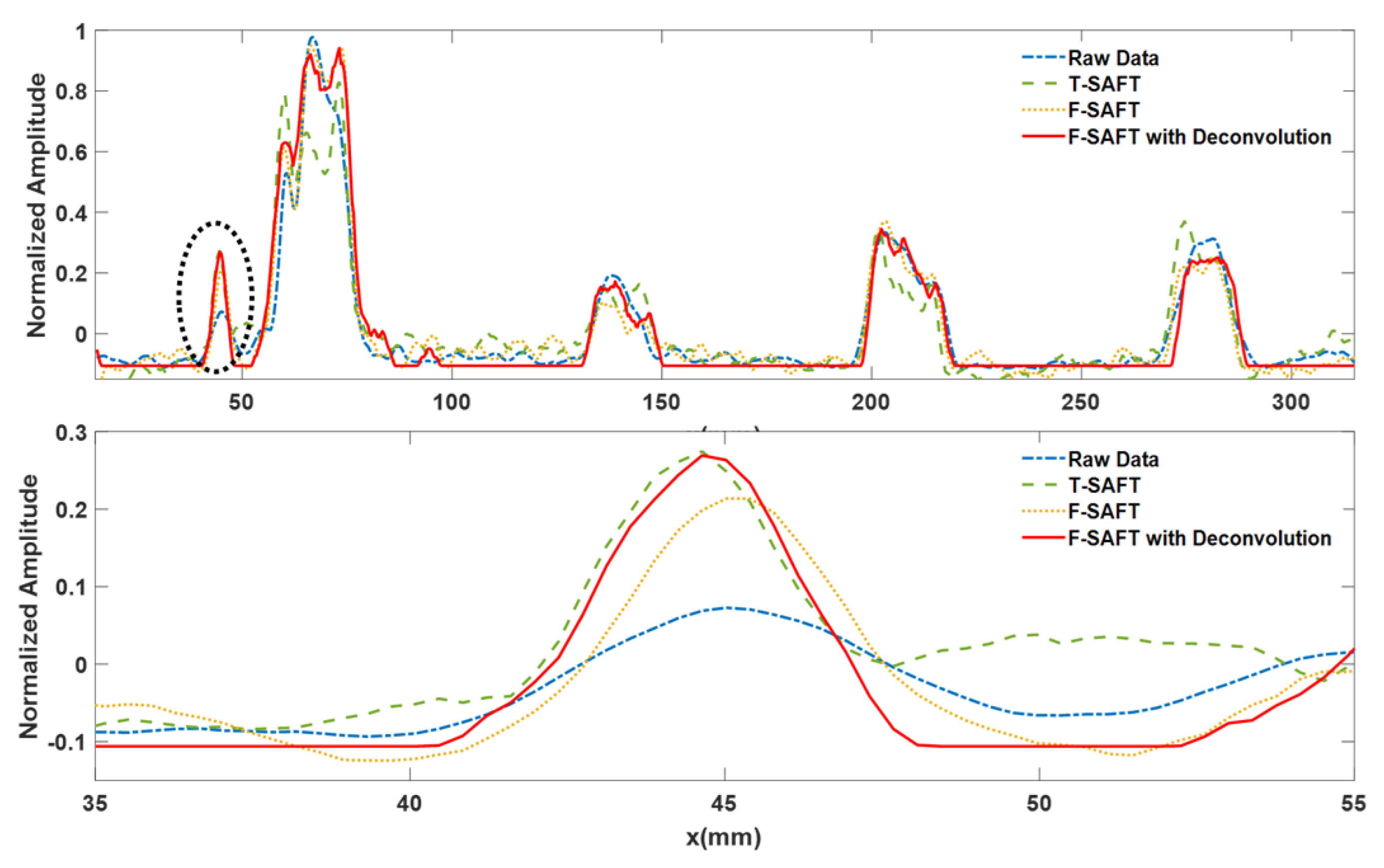

Based on the above background, it is proposed to conduct research on online high-resolution ultrasound TOFD imaging technology for the pipeline girth welds. The proposed method improves the TOFD image resolution in both longitudinal and transverse directions with an extreme low time costs, providing a potential to realize real-time quantitative TOFD detection. According to the simulation and experimental results, the proposed method can outline the trend of defects with very fine stripes, and the transverse resolution of image is reduced about 35%. Also, the time cost of the proposed method is 0.96 second and much less than the TOFD data acquisition time, showing the potential for real-time inspection.

2. Theoretical Expression of the General Model for Ultrasound TOFD Imaging Detection Signals

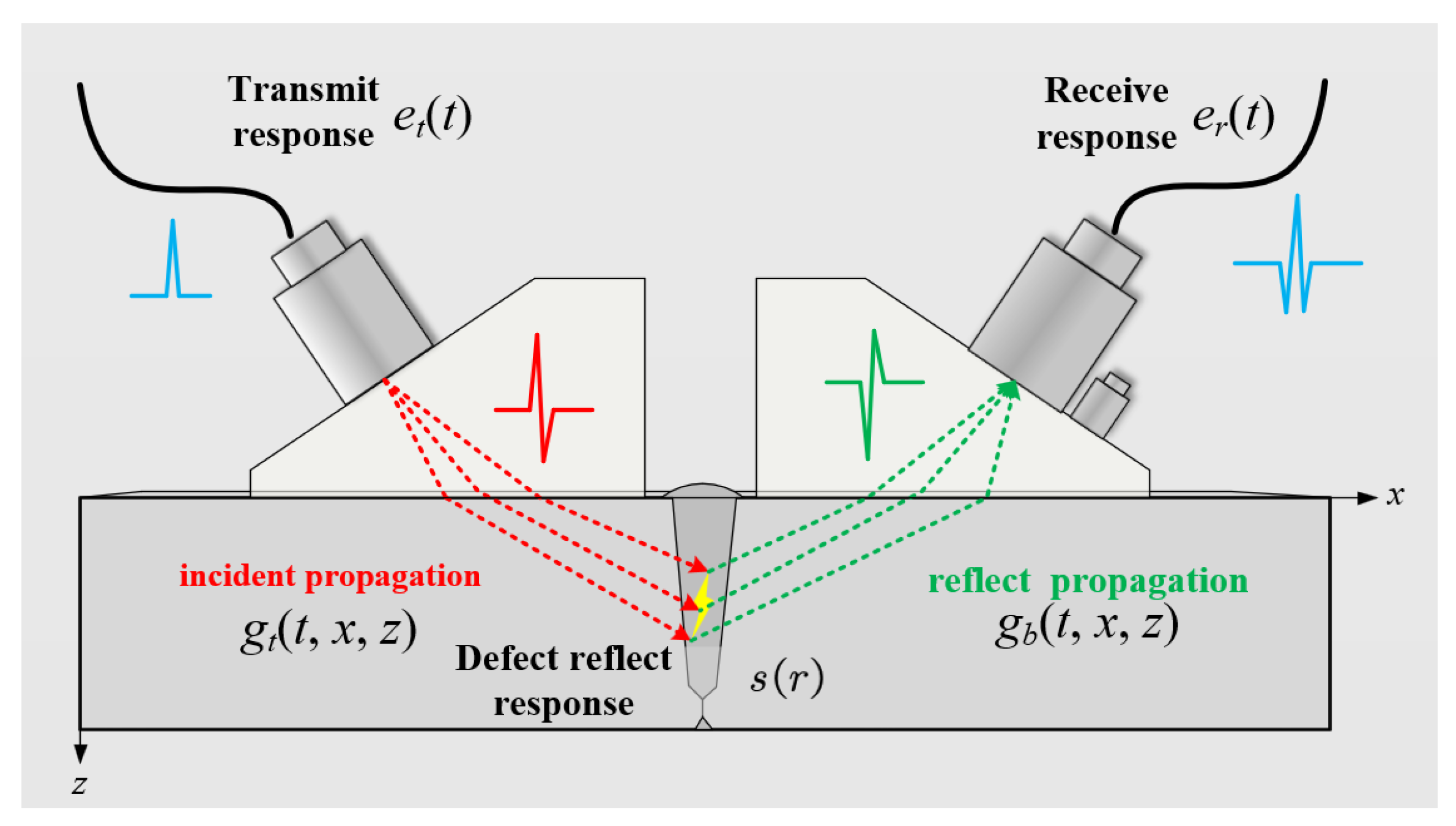

Ultrasound TOFD imaging detection mainly includes five processes from emission to reception, which are ultrasonic transducer excitation, incident propagation, defect response, reflection propagation, and ultrasonic transducer reception respectively, as shown in

Figure 1. According to the classical linear system theory, the general theoretical expression for the ultrasound TOFD detection signal is obtained as:

Among them, represents the recieved TOFD signal, and represent the exciting response function and recieving response function of the ultrasonic transducers respectively, and represent the time-spatial response functions of the incident propagation path and the received propagation path, represents the spatial distribution function which used to characterize the reflection response of the defect. Where, represents the detection position of the TOFD signals and denote the spatial position of the specific point in ROI. is also the reconstruction goal of high-resolution ultrasound TOFD imaging, and ⨂ represents the convolution operator.

Although all five processes mentioned above are correlated using convolution, their convolution dimension and method are different.

and

modulate signals in the time domain, and its convolution occurs in the time domain, mainly manifested in its effect on signal bandwidth. However,

and

are convolutions in the time spatial domain, which mainly represent the diffraction effect of ultrasound waves in physical space. Furthermore, Equation (

1) can be separated into two separate parts and express it in the spatial frequency domain as:

As shown in Equation (

2), the reflection coefficient function

is separated out as an intermediate. The above two equations are the two problems addressed in this paper, where

is calculated from the measured data

, which mainly eliminates the problem of signal bandwidth degradation caused by the transducer response and improves the longitudinal resolution of TOFD imaging. In contrast, the use of

to solve for

eliminates diffraction effects and improves the lateral resolution of TOFD imaging. Of course the exact form of the solution will be adapted to the actual situation, but it is fundamentally a temporal and spatial enhancement of the image resolution in terms of the signal bandwidth and diffraction problem.

4. High Transverse Resolution Ultrasound TOFD Imaging Based on Frequency Domain SAFT

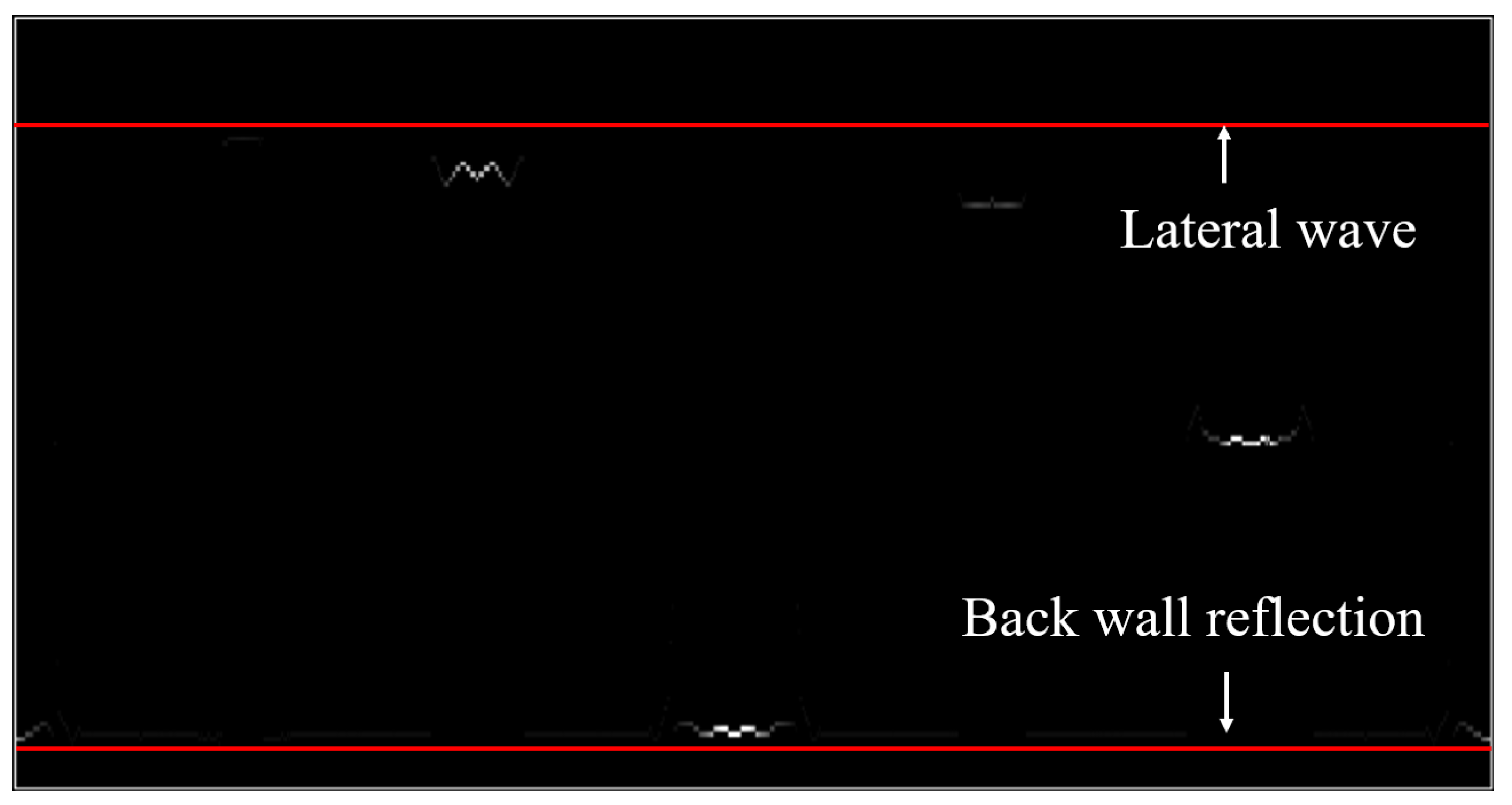

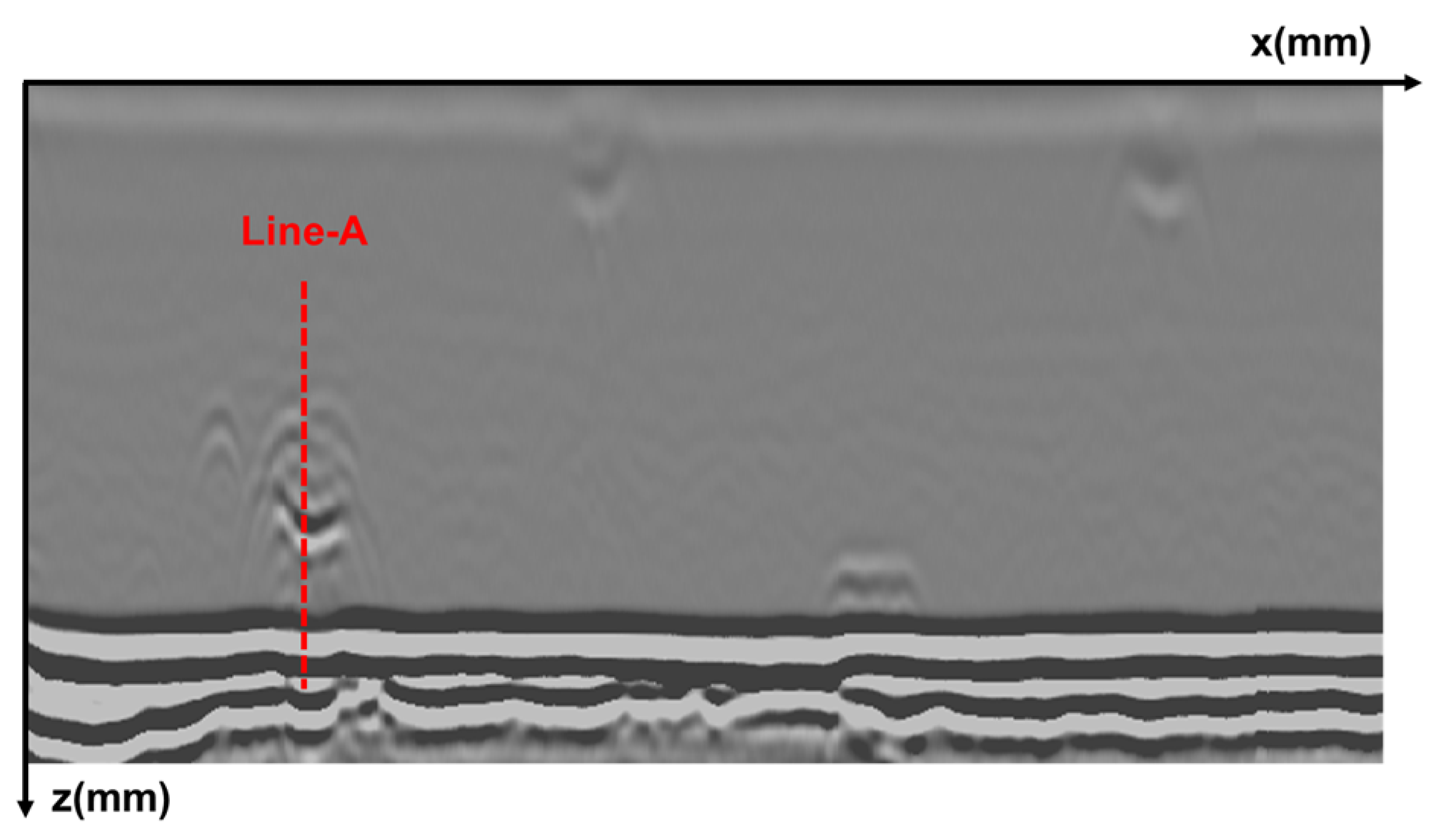

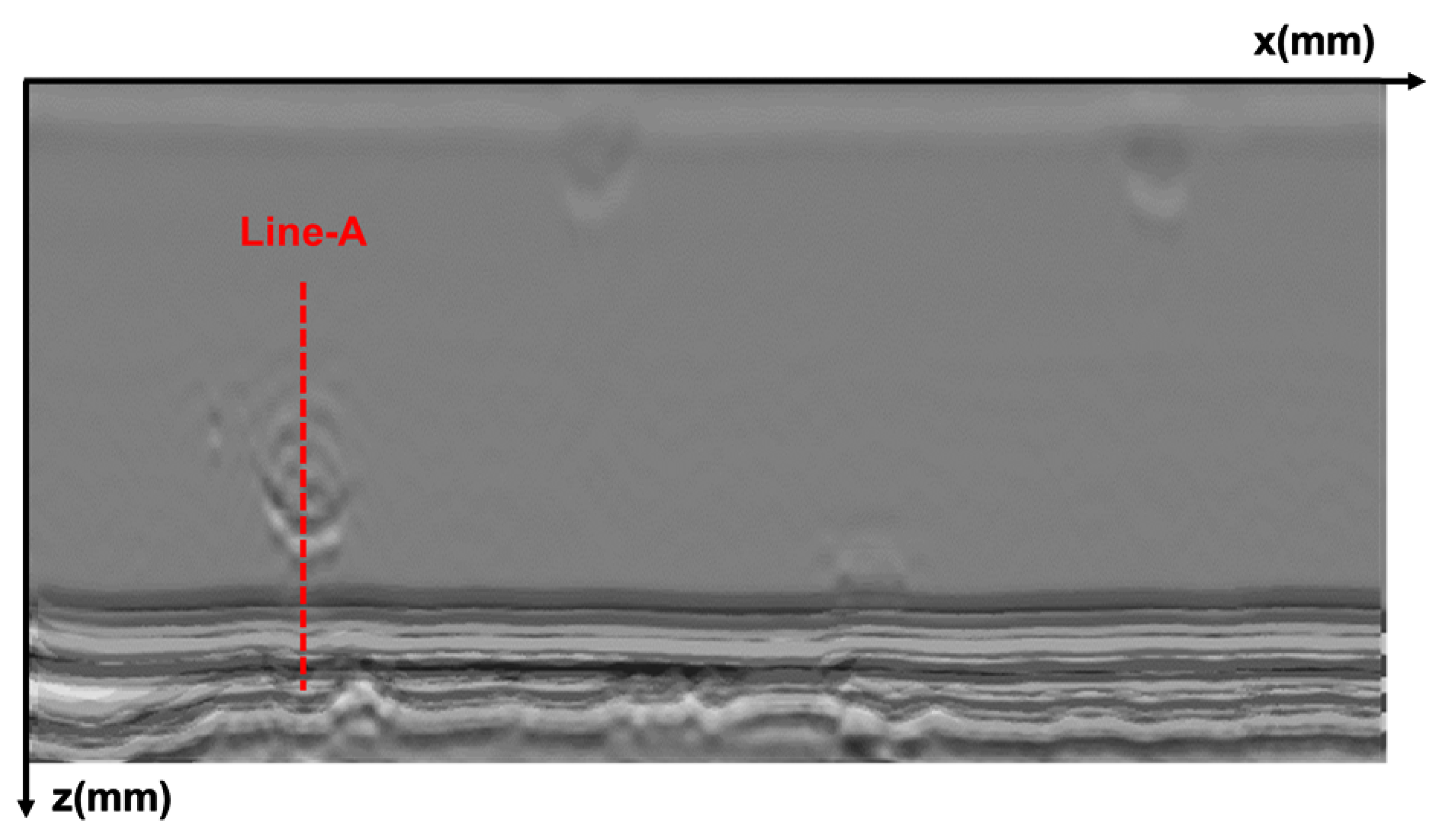

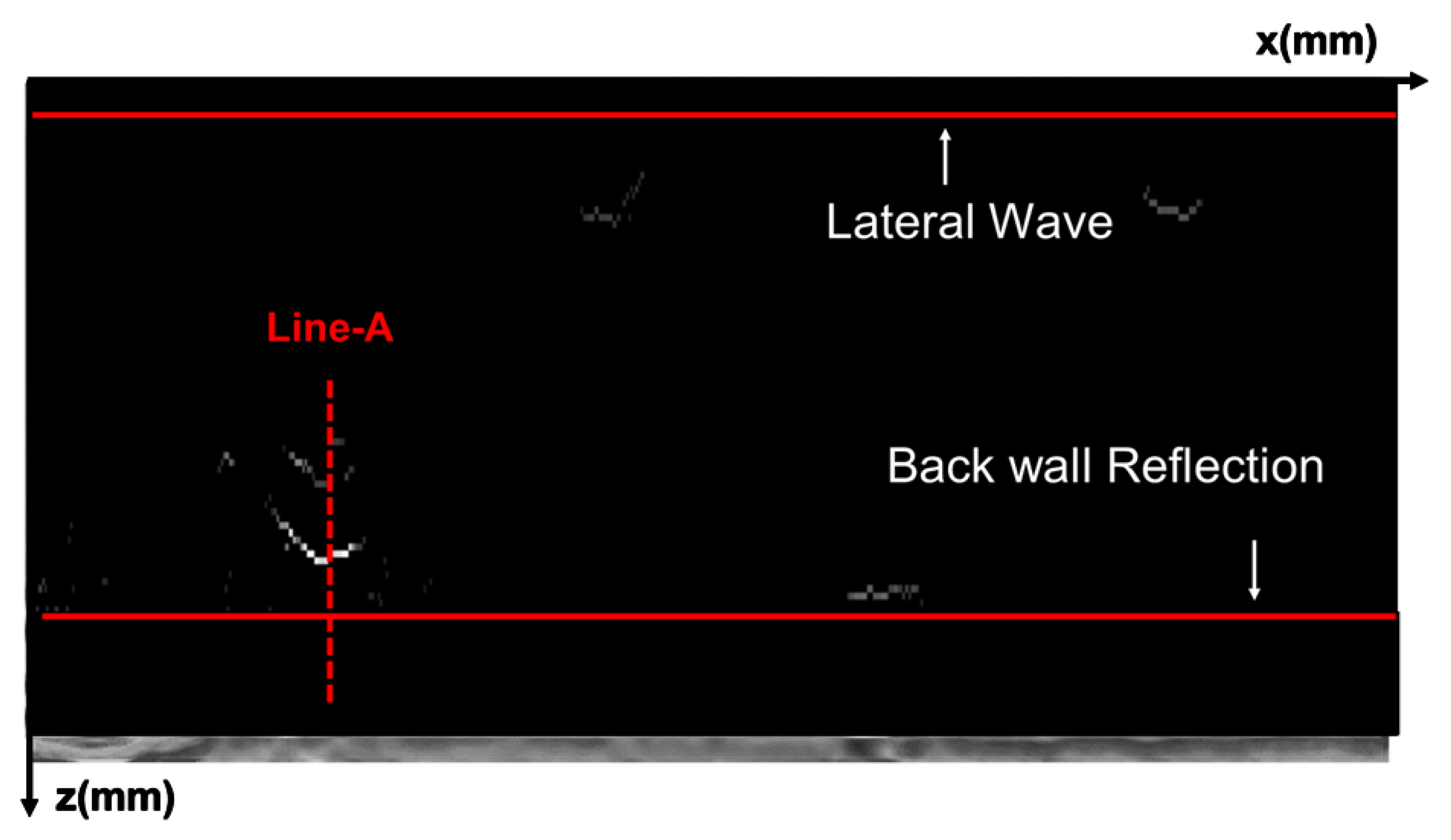

The scanning imaging process of ultrasonic TOFD for pipeline girth welds is actually a D-scan which moves along the girth direction. The transducers are symmetrically arranged on both sides of the weld seam, and driven by a mechanical device. In an ideal situation, when the acoustic axis of the transmitting transducer passes through a defect, an extremely strong reflected echo will be generated and captured by the receiving transducer for detecting the target defect.However, in practical applications of TOFD, the directionality of sound waves is not like that of lasers, but rather generates diffraction at the defect tips, forming arc-shaped reflected waves. Therefore, even point defects can be detected by probes at multiple locations, forming a "tail" shaped curved defect image. For continuous long strip cracks, there are obvious trailing arcs at both ends of the crack, which can easily lead to inaccurate judgment of defect size and burial depth.

To solve the problem of reduced transverse resolution mentioned above, it is often necessary to use Synthetic Aperture Focusing (SAFT) [

16,

22] technology to reconstruct images. However, the D-scan image of TOFD is different from conventional two-dimensional B-scan images, its essence is to project three-dimensional spatial information into two-dimensional images, which will inevitably lead to certain information lossness. The most direct explanation example is that D-scan only collects one A-scan line on each axial section and estimates the defect position based on the time delay of reference echo. However, for the same echo time delay, there are multiple possible defect positions on its axial section, and its specific position information cannot be determined. Usually, the SAFT technique for TOFD imaging approximates the central imaging assumption of defects, assuming that the defects are located at the centerline position of the transducer pair. When the defect is assumed to fall on the centerline of the transducer pair, the emission and reception processes of sound waves naturally satisfy the condition of symmetrical sound path, that is, the emission path and reception path are symmetrical about the centerline.

According to Equation (

1), the spatial diffraction propagation process of ultrasound TOFD can also be constructed by a convolutional model, which is usually defined in the analytical model as a finite amplitude Delta signal with amplitude information

. As shown in Equation (

3), the convolution model can be simplified by multiplying the transmitting frequency-spatial function

, the amplitude information

and the receiving frequency-spatial fucntion

in frequency domain. In order to associate the angular frequency

with the propagating direction of the ultrasonic waves,

is replaced with the wavenumber

. Thus Equation (

3) is rewritten as

The imaging reconstruction is the inverse computation process of

from

. Neglecting the multiple reflections of sound waves in propagating process, the transceiver path is symmetry. Thus, the frequency-spatial functions for transmitting and receiving are equalvalent without differences

Since

can be regarded as the 2-D free-space Green’s function

, Equation (

13) is then obtained as

In TOFD, the transmitting and receiving probes are symmetrically distributed on both sides of the weld. Therefore, the processes of wave incident onto central weld defects, and wave scattering from the defects and received by receiver are also symmetrical. To simplify the calculation of symmetrical bidirectional wave field propagation, the Explosion Reflection Model (ERM) is introduced. Under ERM, we assume that the sound speed of the propagating medium is half of its real value (cerm=c/2), and the propagation process can be equivalently modeled as ultrasonic waves being autonomously emitted from each pixel point, which are then received by the ultrasonic transducer. The phase information of the sound waves is consistent with the self-emission and reception scenario, and the waveform is equivalent along the time axis. In this model, all scatter points are set to emit sound waves at the same time—referred to as the “explosion” moment—and their intensity is directly proportional to the reflection coefficient of each point. The sound fields produced by these points are emitted simultaneously and received together by the ultrasonic transducer. This simplifies the bidirectional wave propagation and only considers the sound field received from the upward returning probe.

According to Weyl’s integral, the Green’s function in the 2-D free space can be expanded and expressed as:

Substituting Equation (

16) into Equation (

15) yields

It can be seen that the relationship between

and

established by Equation (

17) has a complex Fourier decomposition relationship, and here we perform an inverse Fourier transform over

. Equation (

17) can be rewritten as:

For convenience, we assume that

when the size of ROI remains unchanged in the depth direction. Similarly, the amplitude information

can be replaced by the spectrum

through a Fourier transform over

x

According to the analysis based on plane wave model, the acoustic phase

has a much larger modulation effect on the signal than

, and thus

can be neglected here. Since the final image can be normalized, the constant coefficient

is also discarded. Equation (

19) is simplified as

Equation (

20) can be replaced with recursive formula

where

is the wavenumber along the z-axis. The whole process of wavefield derivation is to calculate

and thus estimate the defect signal

with the given wavefield

. However, unlike the conventional B-scan, the deduced depth information

z of D-scan is not directly equal to the defect depth, and because of the lateral distance PCS between the transducer’s scanning plane and the imaging plane, the deduced depth should be corrected as follows:

Its corresponding derivation formula should be written as

The amplitude information

is calculated by performing an inverse Fourier transform over

. Since the actual signals is band limited, then the final image is obtained by superimosing all the

values over the wavenumber

as

In summary, the high lateral resolution is obtained with the following calculation steps

The longitudinal resolution optimized data

is written as

, where

is equal to

.

is calculated with the sparse deconvolution for each position as

The Fourier transform matrix

over

is defined as

The following recursive wavefield derivation at depth

z is to left multiply the dispersion relation matrix

The inverse Fourier transform matrix

over

is defined similarly as

The superimposition over

is to right multiply the constant matrix

as

The calculation of the final image

at depth

z is calculated with the aforementioned matrixed as

where ⊙ is the symbol of Hadamard matrix multiplication. The wavefield calculation for

is then performed for each depth.

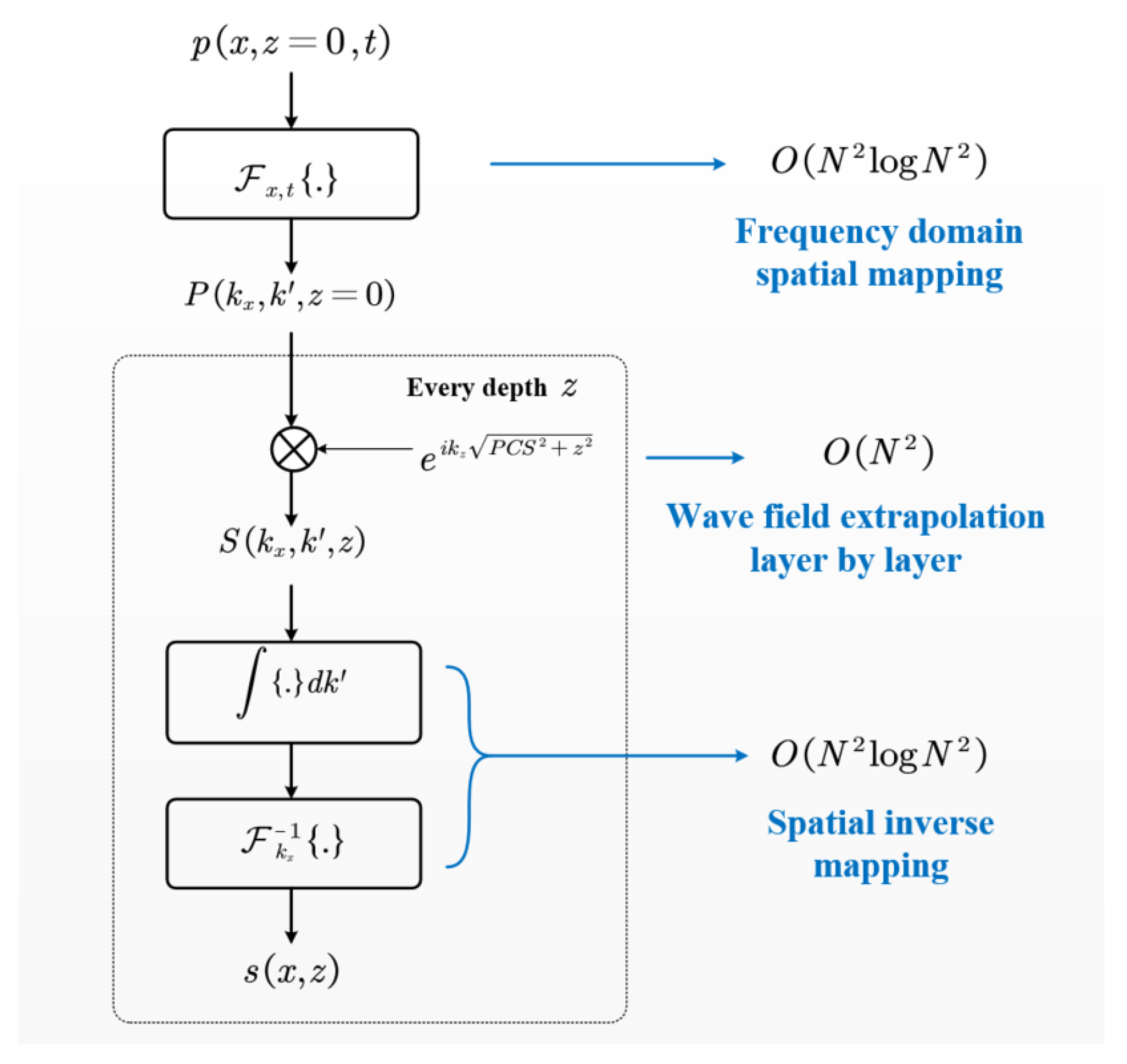

The entire computational workflow, depicted in

Figure 2, primarily consists of three steps: frequency domain spatial mapping, phase migration, and imaging spatial inverse mapping. In the frequency domain spatial mapping step, a two-dimensional Fourier transform is employed to map the received signal

into

, with a computational complexity of approximately

. The phase migration step involves extrapolating the mapped wavefield layer by layer to gather acoustic field information at different depths. The core computational step of this process is accomplished using the Hadamard product, resulting in a complexity of

. The overall computation complexity is

for the case of

N imaging depth layers. The final step, imaging spatial inverse mapping, is conducted through the imaging condition formula, with a complexity of

. When combining these three steps, the computation for the entire imaging reconstruction is

, which is evidently more efficient than the

required by traditional SAFT.