Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

14 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Encoding Approaches

2.2. Decoding Approaches

2.3. Prompt Engineering Approaches

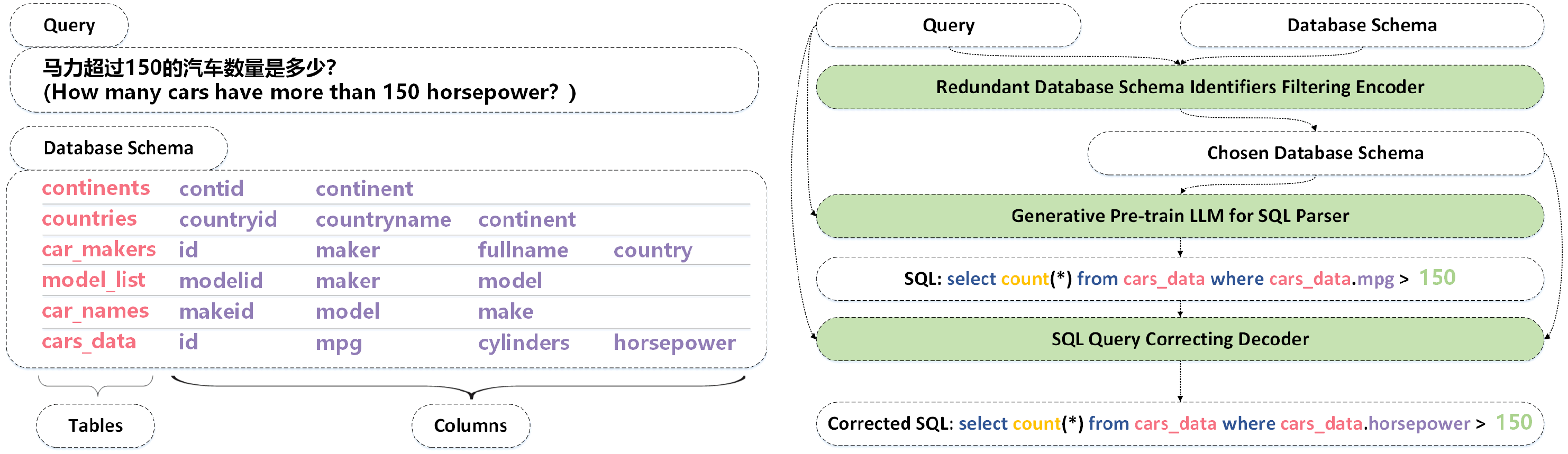

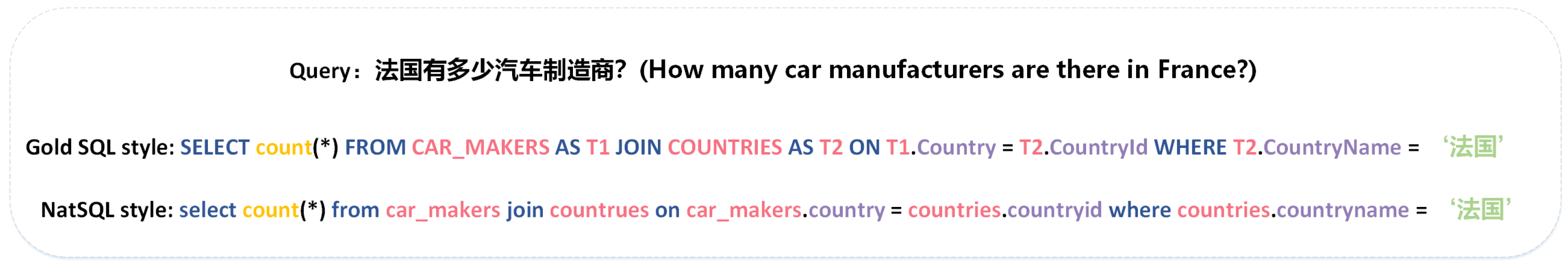

3. FGCSQL

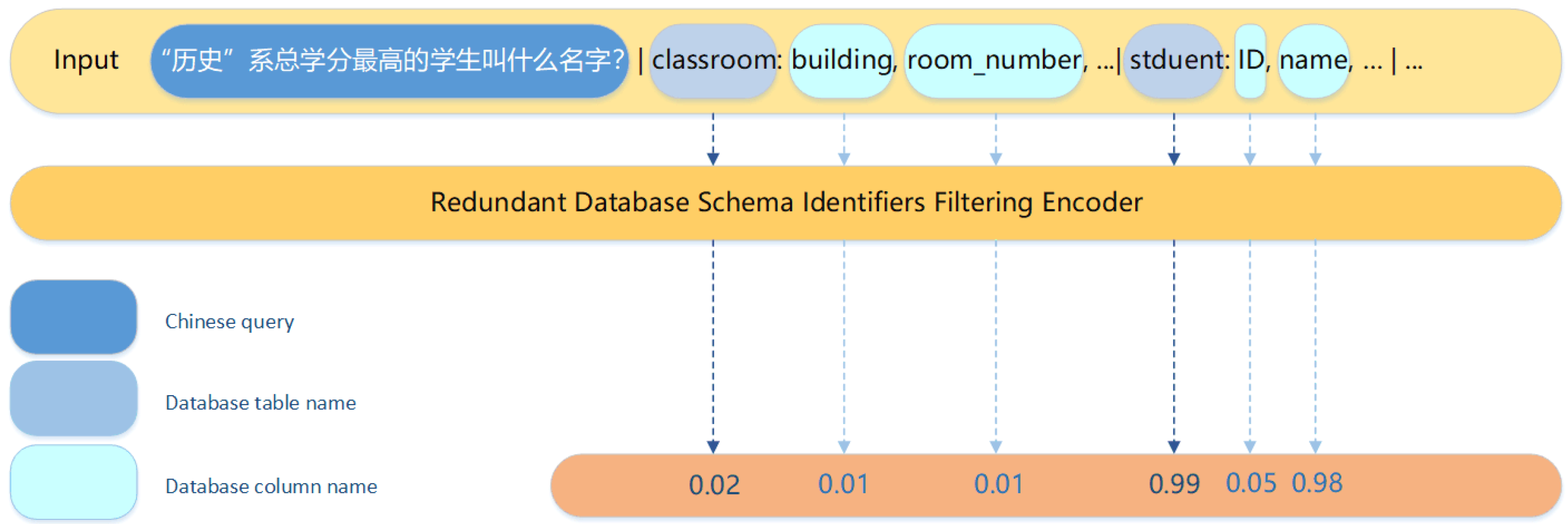

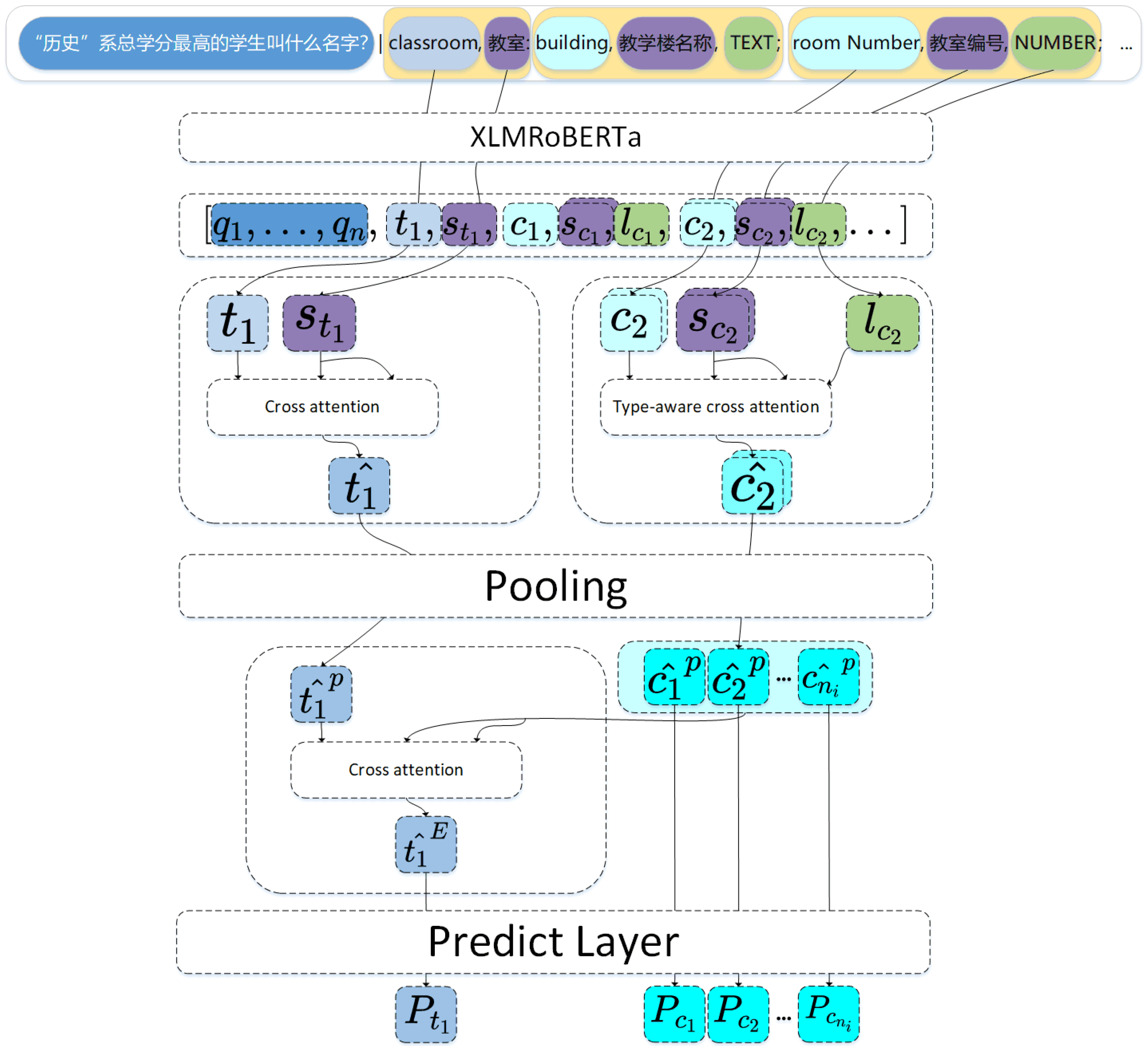

3.1. Redundant Database Schema Items Filtering Encoder

3.1.1. Organization Method of Input Data

3.1.2. Chinese Information Injected Layer for Schema Items

3.1.3. Type-Aware Cross Attention for Columns

3.1.4. Column Injected Layer for Tables

3.1.5. Tables and Columns Classifier

3.2. Generative Pre-Train LLM for SQL Parser

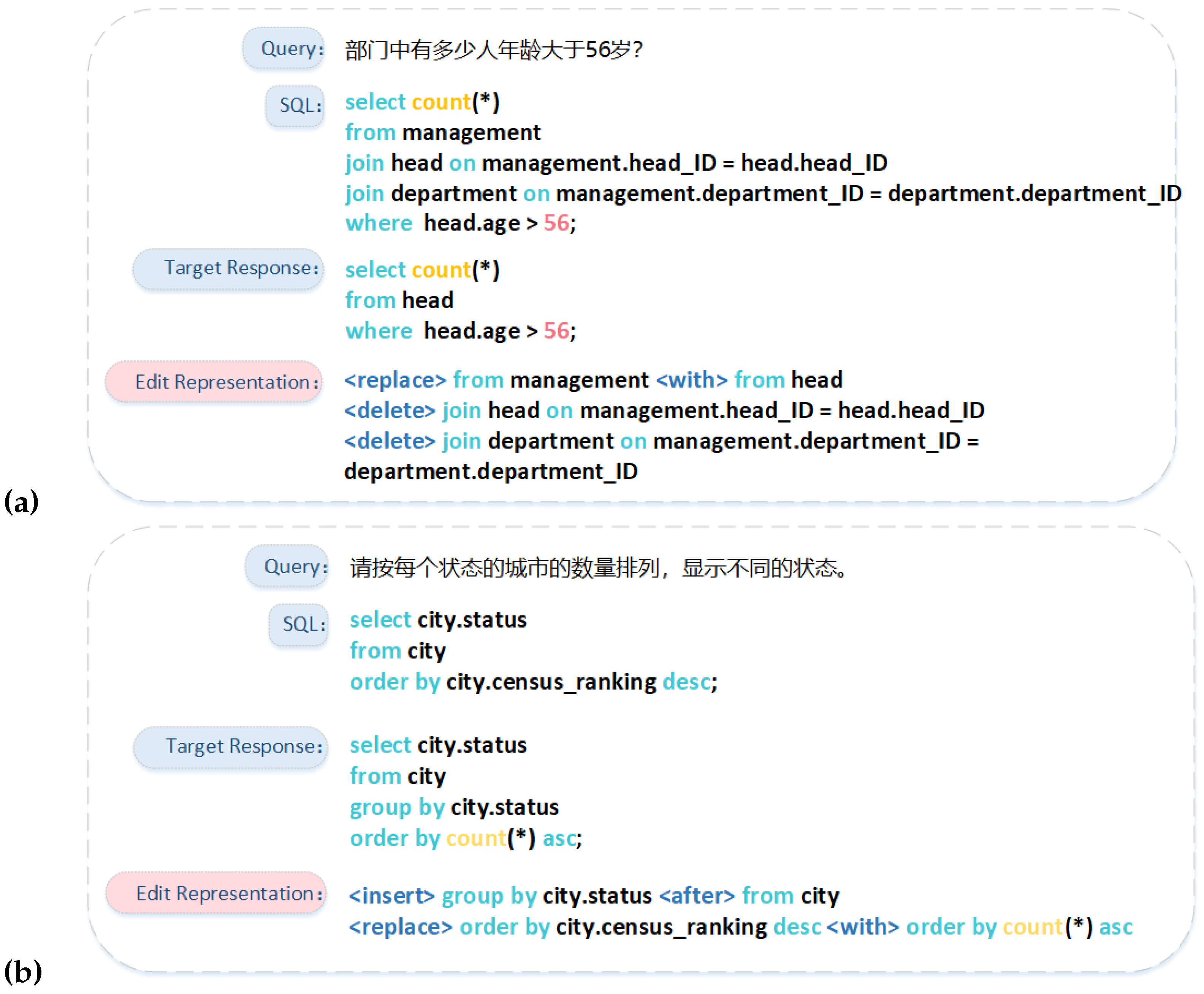

3.3. SQL Query Correcting Decoder

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Data and Environment

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.3. Details

5. Result

5.1. Results on CSpider

5.2. Ablation Studies

5.2.1. Effect of Chinese Information Injection Layer

5.2.2. Effect of Redundant Database Schema Items Filtering Encoder

5.2.3. Effect of IECQN Question Representation

5.2.4. Effect of Parameter-Efficiently Fine-Tuned LLM

5.2.5. Effect of SQL Query Correcting Decoder

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Dong, B.; Wang, X.; Li, C. HIE-SQL: History Information Enhanced Network for Context-Dependent Text-to-SQL Semantic Parsing. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2022; Muresan, S., Nakov, P., Villavicencio, A., Eds.; Dublin, Ireland, 2022; pp. 2997–3007. [Google Scholar]

- Hui, B.; Geng, R.; Wang, L.; Qin, B.; Li, Y.; Li, B.; Sun, J.; Li, Y. S2SQL: Injecting Syntax to Question-Schema Interaction Graph Encoder for Text-to-SQL Parsers. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL 2022; Muresan, S., Nakov, P., Villavicencio, A., Eds.; Dublin, Ireland, 2022; pp. 1254–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Chen, H. Resdsql: Decoupling schema linking and skeleton parsing for text-to-sql. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2023; Volume 37, pp. 13067–13075.

- Wang, B.; Shin, R.; Liu, X.; Polozov, O.; Richardson, M. RAT-SQL: Relation-Aware Schema Encoding and Linking for Text-to-SQL Parsers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Jurafsky, D., Chai, J., Schluter, N., Tetreault, J., Eds.; 2020; Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, P.J. Evaluation of Spoken Language Systems: the ATIS Domain. In Proceedings of the Speech and Natural Language: Proceedings of a Workshop Held at Hidden Valley, Pennsylvania, 24-27 June 1990; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hazoom, M.; Malik, V.; Bogin, B. Text-to-SQL in the Wild: A Naturally-Occurring Dataset Based on Stack Exchange Data. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on Natural Language Processing for Programming (NLP4Prog 2021); Lachmy, R., Yao, Z., Durrett, G., Gligoric, M., Li, J.J., Mooney, R., Neubig, G., Su, Y., Sun, H., Tsarfaty, R., Eds.; Online; 2021; pp. 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, V.; Xiong, C.; Socher, R. Seq2SQL: Generating Structured Queries from Natural Language using Reinforcement Learning. 2017. [arXiv:cs.CL/1709.00103]. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T.; Zhang, R.; Yang, K.; Yasunaga, M.; Wang, D.; Li, Z.; Ma, J.; Li, I.; Yao, Q.; Roman, S.; et al. Spider: A Large-Scale Human-Labeled Dataset for Complex and Cross-Domain Semantic Parsing and Text-to-SQL Task. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Riloff, E., Chiang, D., Hockenmaier, J., Tsujii, J., Eds.; Brussels, Belgium, 2018; pp. 3911–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Hu, X.; Wen, L.; Yu, P.S. A comprehensive evaluation of ChatGPT’s zero-shot Text-to-SQL capability. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.13547. [Google Scholar]

- Rajkumar, N.; Li, R.; Bahdanau, D. Evaluating the Text-to-SQL Capabilities of Large Language Models. 2022. [arXiv:cs.CL/2204.00498]. [Google Scholar]

- Trummer, I. CodexDB: Generating Code for Processing SQL Queries using GPT-3 Codex. 2022. [arXiv:cs.DB/2204.08941]. [Google Scholar]

- Pourreza, M.; Rafiei, D. DIN-SQL: Decomposed In-Context Learning of Text-to-SQL with Self-Correction. 2023. [arXiv:cs.CL/2304.11015]. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, D.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Sun, X.; Qian, Y.; Ding, B.; Zhou, J. Text-to-SQL Empowered by Large Language Models: A Benchmark Evaluation. 2023. [arXiv:cs.DB/2308.15363]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Radev, D. TypeSQL: Knowledge-Based Type-Aware Neural Text-to-SQL Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 2 (Short Papers); Walker, M., Ji, H., Stent, A., Eds.; New Orleans, Louisiana, 2018; pp. 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Yang, D.; Zhang, J.; Guo, J.; Zhou, B.; Lou, J.G. Awakening Latent Grounding from Pretrained Language Models for Semantic Parsing. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021; Online. Zong, C., Xia, F., Li, W., Navigli, R., Eds.; 2021; pp. 1174–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Zhang, C.; Li, Q.; Song, D. An end-to-end multi-task learning to link framework for emotion-cause pair extraction. 2021 International Conference on Image, Video Processing, and Artificial Intelligence 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, H.; Liu, B.; Shi, X.; Jin, H. Semantic and Syntactic Enhanced Aspect Sentiment Triplet Extraction. 2021. [arXiv:cs.CL/2106.03315]. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, H.; Zhou, L.; He, Z.; Wu, H.; Wang, H.; Zong, C. Synchronous Speech Recognition and Speech-to-Text Translation with Interactive Decoding. CoRR 2019, abs/1912.07240, 1912.07240]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Awadallah, A.H.; Meek, C.; Polozov, O.; Sun, H.; Richardson, M. Structure-Grounded Pretraining for Text-to-SQL. CoRR 2020, abs/2010.12773, [2010.12773]. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Zhang, W.; Huang, M.; Feng, S.; Wu, Y. Integrating Relational Structure to Heterogeneous Graph for Chinese NL2SQL Parsers. Electronics 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogin, B.; Berant, J.; Gardner, M. Representing Schema Structure with Graph Neural Networks for Text-to-SQL Parsing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Korhonen, A., Traum, D., Màrquez, L., Eds.; Florence, Italy, 2019; pp. 4560–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Yasunaga, M.; Yang, K.; Zhang, R.; Wang, D.; Li, Z.; Radev, D. SyntaxSQLNet: Syntax Tree Networks for Complex and Cross-Domain Text-to-SQL Task. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Riloff, E., Chiang, D., Hockenmaier, J., Tsujii, J., Eds.; Brussels, Belgium, 2018; pp. 1653–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, D.; Shin, M.C.; Kim, E.; Shin, D.R. RYANSQL: Recursively Applying Sketch-based Slot Fillings for Complex Text-to-SQL in Cross-Domain Databases. Computational Linguistics 2021, 47, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhan, Z.; Gao, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Lou, J.G.; Liu, T.; Zhang, D. Towards Complex Text-to-SQL in Cross-Domain Database with Intermediate Representation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics; Korhonen, A., Traum, D., Màrquez, L., Eds.; Florence, Italy, 2019; pp. 4524–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Chen, X.; Xie, J.; Purver, M.; Woodward, J.R.; Drake, J.; Zhang, Q. Natural SQL: Making SQL Easier to Infer from Natural Language Specifications. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021; Moens, M.F., Huang, X., Specia, L., Yih, S.W.t., Eds.; Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 2021; pp. 2030–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholak, T.; Schucher, N.; Bahdanau, D. PICARD: Parsing Incrementally for Constrained Auto-Regressive Decoding from Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Moens, M.F., Huang, X., Specia, L., Yih, S.W.t., Eds.; Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 2021; pp. 9895–9901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Gao, Y.; Pan, M.; Wang, D.; Che, W.; Zhan, D.; Lou, J.G. UniSAr: A Unified Structure-Aware Autoregressive Language Model for Text-to-SQL. 2022. [arXiv:cs.CL/2203.07781]. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Tatwawadi, K.; Brockschmidt, M.; Huang, P.S.; Mao, Y.; Polozov, O.; Singh, R. Robust Text-to-SQL Generation with Execution-Guided Decoding. 2018. [arXiv:cs.CL/1807.03100]. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, W.; Yim, J.; Park, S.; Seo, M. A Comprehensive Exploration on WikiSQL with Table-Aware Word Contextualization. 2019. [arXiv:cs.CL/1902.01069]. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Cai, J.; Zhang, J.; Tao, D.; Zhuang, B. Sensitivity-Aware Visual Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning. 2023. [arXiv:cs.CV/2303.08566]. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, B.; Meng, Y.; Monz, C. Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning without Introducing New Latency. 2023. [arXiv:cs.CL/2305.16742]. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Yu, L.; Li, X.; Yang, L.; Zuo, C. LLaMA-Reviewer: Advancing Code Review Automation with Large Language Models through Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning. 2023. [arXiv:cs.SE/2308.11148]. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, S.; White, M.; Mooney, R.; Payani, A.; Srinivasa, J.; Su, Y.; Sun, H. Text-to-SQL Error Correction with Language Models of Code. 2023. [arXiv:cs.CL/2305.13073]. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open Foundation and Fine-Tuned Chat Models. 2023. [arXiv:cs.CL/2307.09288]. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Z.; Qian, Y.; Liu, X.; Ding, M.; Qiu, J.; Yang, Z.; Tang, J. GLM: General Language Model Pretraining with Autoregressive Blank Infilling. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 2022; pp. 320–335.

- Baichuan. Baichuan 2: Open Large-scale Language Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.10305.

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, W. LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. CoRR 2021, abs/2106.09685, [2106.09685]. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, W.; Joty, S.; Hoi, S.C. CodeT5: Identifier-aware Unified Pre-trained Encoder-Decoder Models for Code Understanding and Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing; Moens, M.F., Huang, X., Specia, L., Yih, S.W.t., Eds.; Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 2021; pp. 8696–8708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, R.; Chen, L.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, S.; Yu, K. LGESQL: Line Graph Enhanced Text-to-SQL Model with Mixed Local and Non-Local Relations. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers); Zong, C., Xia, F., Li, W., Navigli, R., Eds.; 2021; pp. 2541–2555. Online. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vougiouklis, P.; Papasarantopoulos, N.; Zheng, D.; Tuckey, D.; Diao, C.; Shen, Z.; Pan, J.Z. FastRAT: Fast and Efficient Cross-lingual Text-to-SQL Semantic Parsing. Proc. of IJCNLP-AACL 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Zhang, W.; Huang, M.; Feng, S.; Wu, Y. Integrating Relational Structure to Heterogeneous Graph for Chinese NL2SQL Parsers. Electronics 2023, 12, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Approach | EM | EX |

|---|---|---|

| RAT-SQL | 41.4 | - |

| LGESQL | 58.6 | - |

| FastRAT | 61.3 | 67.7 |

| ChatGPT + BS | 32.6 | 65.1 |

| Heterogeneous Graph + Relative Position Attention | 66.2 | - |

| RESDSQL + NatSQL | 65.6 | 79.1 |

| Auto-SQL-Correction + NatSQL | 64.6 | 75.9 |

| Ours | 65.8 | 81.1 |

| Model Variant | Table AUC | Column AUC | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDsiF-Encoder-without CII layer | 0.9725 | 0.9703 | 1.9428 |

| RDsiF-Encoder-without Type-aware attention | 0.9811 | 0.9713 | 1.9524 |

| RDsiF-Encoder | 0.9814 | 0.9795 | 1.9609 |

| Model Variant | EM | EX |

|---|---|---|

| LlaMa2-7b-chat + LoRA + IECQN | 65.1 | 80.9 |

| LlaMa2-7b-chat + LoRA + IECQN -with all schema items | 61.1 | 73.0 |

| ChatGLM2-6b + LoRA + IECQN | 64.2 | 79.7 |

| ChatGLM2-6b + LoRA + IECQN -with all schema items | 59.3 | 71.4 |

| Model Variant | EM | EX |

|---|---|---|

| LlaMa2-7b-chat + LoRA + IECQN | 65.1 | 80.9 |

| LlaMa2-7b-chat + LoRA + BS | 53.1 | 68.0 |

| ChatGLM2-6b + LoRA + IECQN | 64.2 | 79.7 |

| ChatGLM2-6b + LoRA + BS | 36.6 | 51.1 |

| Model Variant | EM | EX |

|---|---|---|

| ChatGPT | 32.6 | 65.1 |

| LlaMa2-7b-chat | 14.3 | 23.4 |

| LlaMa2-7b-chat + LoRA + BS | 53.1 | 68.0 |

| ChatGLM2-6b | 13.1 | 21.9 |

| ChatGLM2-6b + LoRA + BS | 36.6 | 51.1 |

| Model Variant | EM | EX |

|---|---|---|

| FGCSQL | 65.8 | 81.1 |

| FGCSQL -without SQL Query Correcting Decoder | 65.1 | 80.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).